Abstract

Ventricular free wall rupture is a rare post myocardial complication with a high associated mortality. In this article we discuss the case of an elderly patient who presented to our emergency department in shock after an episode of syncope. Using Point Of Care Ultrasound (POCUS), identification of cardiac tamponade and pericardial thrombus was possible, signs indicating a diagnosis of free wall rupture. Early initiation of transfer proceedings to a tertiary cardio‐thoracic unit was therefore possible, resulting in a positive patient outcome.

Introduction

Following myocardial infarction (MI), free wall rupture is a rare but serious complication associated with a particularly high mortality rate. The resulting cardiac tamponade often leads to profound shock which is minimally responsive to fluid resuscitation. A clinical suspicion should be raised when there is a history of chest pain, syncope and signs of cardiac tamponade.

Here we discuss the case of a 72‐year‐old male who presented with shock in the absence of chest pain. This highlights the importance of point‐of‐care ultrasound (POCUS) in the emergency department (ED), which demonstrated tamponade with the presence of a pericardial thrombus raising the suspicion of free wall rupture. This was confirmed in theatre, where surgery was successful and the patient was discharged 10 days later.

Case Presentation

A 72‐year‐old male with a history of hypertension presented to the ED after an episode of syncope. He denied chest pain or prodromal symptoms. Upon arrival, he was haemodynamically unstable but alert, with a blood pressure of 72/63 and a heart rate 118. Electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm, right bundle branch block (RBBB) and ST depression in V1‐4. Initial troponin was 5.15 ng/ml (normal values < 0.03 ng/ml). Chest X‐ray appeared normal.

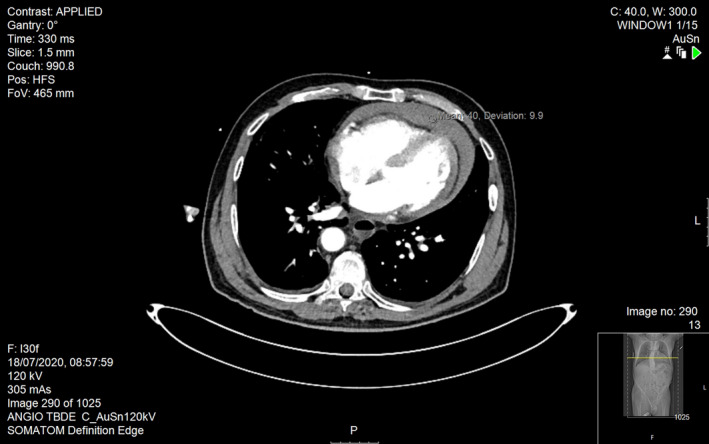

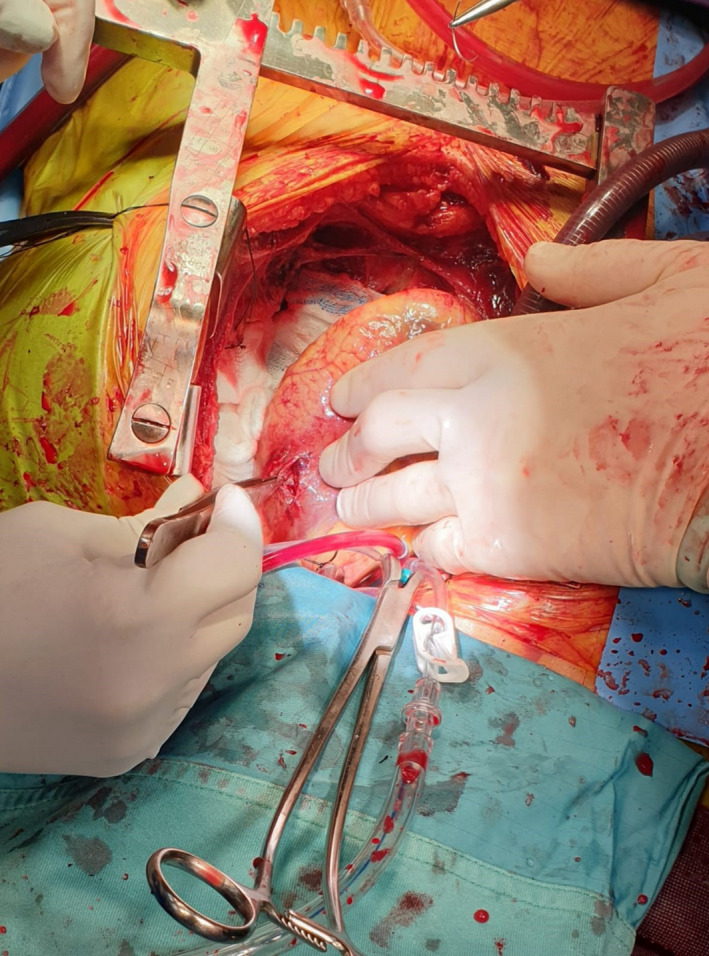

POCUS demonstrated a large, heterogenic pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade and segmental akinesia (Figure 1; Video S1). Computer tomography angiography (CTA) excluding aortic dissection and supported a diagnosis of left ventricular free wall rupture (Figure 2). He was immediately prepared for surgery where the rupture was visualised; the size of the defect was 3‐4 cm (Figure 3). The patient underwent successful surgical repair using a linear closure technique and a pericardial patch. He was discharged 10 days later with no evidence of neurological deficit.

Figure 1.

POCUS (RUSH protocol) demonstrating a large pericardial effusion, with a flaccid, hyperechogenic shadow within the pericardial cavity, left ventricular wall segmental akinesia and restricted expansion of the right ventricle. Additionally, paradoxical movement of the right atrium and dilation of the inferior vena cava were noted

Figure 2.

CTA revealed a medium pericardial effusion with thrombus formation, infarct within the left wall of the LV with mild pulmonary oedema and no evidence of aortic dissection

Figure 3.

A photograph taken during the surgical procedure. After the clot was excavated from the pericardium, the tear was visualised and subsequently repaired. The size of the defect, as demonstrated at the operating theatre, was 3–4 cm

Discussion

Rupture of the left ventricular free wall is a rare but serious complication associated with acute MI, with an incidence of 2‐4% following percutaneous intervention (PCI) or thrombolysis.1 Other potentially fatal mechanical complications include rupture of the interventricular septum and acute mitral regurgitation secondary to papillary muscle necrosis.2 Free wall rupture is most common in the left ventricle2 and is associated with a mortality rate of between 20 to 75% depending on the size and underlying morphology of the rupture as well as patient co‐factors.3

Echocardiography is the most sensitive and efficient diagnostic tool.3, 4 Typically, a pericardial effusion is observed with evidence of tamponade and regional wall motion abnormalities. The tear itself may also be visualised depending on size.4 As the rupture is characteristically serpiginous throughout the various ventricular layers, a thrombus may form a partial seal permitting time for surgical intervention.3, 4

Funding

We acknowledge that there are no sources of funding for this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no commercial associations or sources of support that might pose a conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Daniel Trotzky: Conceptualization (equal); Methodology (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Aya Cohen: Formal analysis (equal); Project administration (equal). Ali Amer: Data curation (equal). Salha Fraij: Data curation (equal). Daniel Edward Fordham: Writing‐original draft (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Gregory Granovsky: Data curation (equal). Uri Aizik: Data curation (equal). Natali Carady: Data curation (equal). Shmuel Fuchs: Data curation (equal). Bethlehem Menngesha: Data curation (equal). Oleg Burgsdorf: Data curation (equal). Inna Yofik: Data curation (equal). Ari Naimark: Data curation (equal). Inbal Baruch: Data curation (equal). Yaron D. Barac: Data curation (equal). Gal Pachys: Data curation (equal).

Supporting information

Video S1

References

- 1.Moreno R, López‐Sendón J, García E, de Isla Leopoldo P, de Sá Esteban L, Ortega A, et al. Primary angioplasty reduces the risk of left ventricular free wall rupture compared with thrombolysis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am College Cardiol 2002; 39(4): 598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutty RS, Jones N, Moorjani N. Mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology Clin 2013; 31(4): 519–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ESC Scientific Document Group. Eur Heart J 2018; 39(2): 119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMullan MH, Maples MD, Kilgore TL, Hindman SH. Surgical experience with left ventricular free wall rupture. Ann Thoracic Surg 2001; 71(6): 1894–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1