Abstract

There is an emerging interest in studying social action and civic engagement as a part of the developmental process. Studies among youth of color indicate that empowerment has been associated with well-being, a critical perspective, and in combating social oppression. These studies also show that civic involvement and awareness of social justice issues are associated with positive developmental outcomes including empowerment. The range of predictors and outcomes related to empowerment have been insufficiently explored. This study used structural equation modeling path analysis techniques to examine the association community civic participation and psychological sense of community have with intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment, through both ethnic identity and social justice orientation among urban youth of color (N =383; 53.1% Female; 75% Hispanic; 50.6% were 13 and 15 years of age). Findings illustrate that greater community civic participation and psychological sense of community are associated with both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment, through both ethnic identity and a social justice orientation; however, with some noted variations. Ethnic identity and social justice orientation mediated community civic participation and psychological sense of community and both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment. Implications put forward for community youth-workers and community programming.

Keywords: Cognitive psychological empowerment, Intrapersonal psychological empowerment, Sense of community, Civic engagement, Social justice, Ethnic identity, Youth of color

Introduction

The collective outrage of citizens is catching the attention of news cameras, politicians, and scholars, alike. Whether we are observing political-social activism through the #BlackLivesMatter movement, gun reform through the March For Our Lives Movement, or activism for a clean Dream Act and Immigrant rights through the DREAM Teams throughout the U.S., a similar theme runs constant: youth are no longer willing to sit on the peripheries, while adults continue to make decisions that are impacting their lives and futures. These acts of social change are, however, what are highlighted in the news; whereas, racial-ethnic minority youth in urban communities tend to have their voices stymied in relation to social change (Ginwright 2015; Lardier et al. 2018b). Furthermore, we know little about the mechanisms through which youth empowerment and critical awareness occurs among youth of color (Christens et al. 2018).

The emerging interest in studying social action and civic engagement as a part of the developmental process is noted in the literature on youth civic development, empowerment, and positive youth development (Christens et al. 2018; Diemer and Rapa 2016; Zeldin et al. 2018). Whether described as civic engagement or sociopolitical development (Itzhaky and York 2000; Zimmerman and Zahniser 1991), youth action is a critical component in human development and associated with several outcomes (Lardier et al. 2019a, b) including awareness of social justice issues, mental well-being, avoidance of risk behaviors (Christens 2019; Christens et al. 2018; Finlay and Flanagan 2013), and educational attainment (Chan et al. 2014). Racial-ethnic minority adolescents, however, may feel less empowered and be less likely to engage in broader social and institutional changes. This may be due to the proliferation of significant power imbalances and inequalities within their social system (Hope 2016). Nonetheless, recent studies show that racial-ethnic minority adolescents with a sense of belongingness, racial-ethnic group identity connection, and a greater social justice awareness tend to identify as more empowered (Dinzey-Flores et al. 2019; Hipolito-Delgado and Zion 2015; Hope and Bañales 2019; Lardier et al. 2020). Despite such work, the range of predictors and outcomes related to civic engagement, development, and empowerment have been insufficiently explored (Christens 2019; Peterson 2014).

There is a need to document the relationship between community-based perceptions (e.g., psychological sense of community) and behaviors (e.g., community civic participation) and awareness of social justice concerns with dimensions of psychological empowerment including critical awareness of social issues and the ability to enact social change (Lardier et al. 2019a). Uncovering the ways that racial-ethnic minority youth in disenfranchised and oppressed social conditions develop empowerment, as well as develop the criticality to engage and understand their world is a needed area of understanding. Youth that can engage in their community and develop a sense of belongingness not only allows for connection but also empowers youth to examine social conditions that permit social change (Christens 2019). Through such social engagement, youth can begin to challenge authority and engage in critical counter-narratives.

Literature Review

Empowerment Theory and Psychological Empowerment

Empowerment is a multilevel construct at the individual (i.e., psychological), organizational, and community levels (Peterson 2014; Zimmerman 1995, 2000). Empowerment emphasizes action-oriented solutions that relieve the difficulties people face within their lives, as well as the ways in which communities can alter unjust systems that maintain and perpetuate social oppression (Peterson 2014; Zimmerman 1995, 2000). Psychological empowerment is described as a construct developed through ongoing relational processes that allows for the gaining of control and mastery over circumstances influencing the lives of people and communities (Peterson 2014). The multidimensional nomological framework of psychological empowerment encompasses three components: (1) intrapersonal component; (2) interactional or cognitive component; and (3) behavioral component (Zimmerman 1995). A relational component has also been defined, more recently (see Christens 2012). Much of the empowerment literature has focused on intrapersonal psychological empowerment, with less research examining the cognitive component.

Intrapersonal psychological empowerment is defined as perceptions of control and a critical awareness of social issues, specific to the sociopolitical system, leading to sociopolitical change (Zimmerman 1995, 2000). Intrapersonal psychological empowerment has been studied through sociopolitical control (SPC) and measured through the Sociopolitical Control Scale (SPCS). SPC is conceptualized through self-efficacy motivation, competence, and perceived control (Peterson et al. 2011; Zimmerman and Zahniser 1991). Peterson et al. (2011) provided the earliest validation of the SPCS for Youth (SPCS-Y). Recent studies have further validated an abbreviated version of the SPCS-Y among youth of color (e.g., Lardier et al. 2018c; Opara et al. 2019). SPC has been associated with participation in community programming (Speer et al. 2012; Wilke and Speer 2011), a sense of community, ethnic identity, community civic participation (Christens et al. 2018; Lardier et al. 2018a; Lardier 2018, 2019; Peterson and Reid 2003), and a social justice orientation (Lardier et al. 2019a). The conceptual overlap between the intrapersonal psychological empowerment and components of the broader nomological psychological empowerment network including cognitive psychological empowerment have also been examined.

Cognitive psychological empowerment is defined as a critical awareness of the socio-political environment (Speer 2000; Zimmerman 2000). Further, cognitive psychological empowerment also centers on the power and ability to engage in socio-political change (Speer 2000; Zimmerman 2000). Cognitive psychological empowerment comprises four dimensions—critical awareness, decision making, resource mobilization, and relational processes that include shaping the ways in which power and beliefs manifest to enact change through relationships (Speer 2000). The Cognitive Empowerment Scale (CES) is adopted to measure cognitive psychological empowerment (Christens et al. 2013; Lardier et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2018) through the source, nature, and instruments of social power (Speer and Peterson 2000). Cognitive psychological empowerment, through the CES, has been examined as both a process of empowerment (e.g., Rodrigues et al. 2018) and in relation to critical consciousness (e.g., Christens et al. 2013, 2018). Recently, a version of the CES for youth (CES-Y) was tested and support was found for the three-dimensional factor structure. Lardier et al. (2020) tested the original iteration of the CES (used in this study) and found support for the factor structure of this scale among youth of color. Despite such research, additional work is needed that examines cognitive psychological empowerment among adolescents of color (Lardier et al. 2020; Lardier 2019; Rodrigues et al. 2018). The present study addresses this gap and underscores the importance of cognitive psychological empowerment in human development.

Psychological Sense of Community and Community Civic Participation

Psychological sense of community and community civic participation are predictive of self-worth, leadership, connection to one’s community and culture, and empowerment (Christens et al. 2013; Crocetti et al. 2012; Lardier et al. 2019b; Martinez et al. 2012; McMillan and Chavis 1986; Peterson et al. 2017). Therefore, psychological sense of community and community civic participation are important in the empowerment process. These mechanisms are not only critical in the empowerment process, but also for and among racial-ethnic minority youth whose lives intersect with marginalization, thus justifying the need for understanding the ways these variables interact in youth development. We predicted that psychological sense of community and community civic participation would have a positive association with ethnic identity, social justice orientation, and empowerment dimensions including intrapersonal and cognin-turn leads to critical awareness and perceived ability to enact actionableitive psychological empowerment.

Psychological sense of community is defined as perceived belongingness and a belief that community members will meet one another’s needs (McMillan 1996; McMillan and Chavis 1986). As a multidimensional framework, psychological sense of community is defined by four-dimensions: (1) Membership: perceived belongingness to an organized collective; (2) Needs Fulfillment: the expectations of having one’s needs fulfilled by the community; (3) Influence: making a difference within your organization, community, or group; and (4) Emotional Connection: shared emotional connection through shared histories, sociocultural backgrounds, or common places (McMillan and Chavis 1986). Further psychological sense of community focuses on the individual’s psychological investment in the social system in terms of active contributions (McMillan 1996; McMillan and Chavis 1986). This conceptualization of psychological sense of community has inspired numerous studies (e.g., Elfassi et al. 2016; Forenza and Lardier 2017; Gattino et al. 2013; Lardier 2018; Lardier et al. 2019a; Rivas-Drake 2012; Távara and Cueto 2015) aimed at understanding the relationship psychological sense of community has with various indicators related to well-being and empowerment.

Psychological sense of community has been associated with both the well-being and empowerment of individuals, groups, and communities (Elfassi et al. 2016; Lardier et al. 2018d). Youth who feel a sense of community are satisfied and place value on their community, increasing their drive toward improving and contributing to their community (Christens et al. 2013; Gutierrez 1989). Racial-ethnic minority youth in urban communities that have a stronger perceived psychological sense of community have greater ethnic group attachment (Gutierrez 1989; Lardier 2018; Rivas-Drake 2012). Studies elsewhere among adolescents of color have also connected psychological sense of community with being buffered from community issues such as violence (Lardier et al. 2017) and contributing positively to their community (Lardier 2018). The existing literature supports the hypothesis that psychological sense of community will have a positive association with both ethnic identity and social justice orientation. Yet, unlike psychological sense of community, the direct relationship between community civic participation and dimensions of psychological empowerment tends to be a result of co-occurring mechanisms (e.g., ethnic group identity).

Youth civic participation has occupied a central role in applied developmental science (Blevins et al. 2018). Zurcher (1970) discussed that community civic participation encompassed perceived self-efficacy, active citizenry, and decreased disconnection, isolation, and alienation. Recent conceptualizations have further theorized civic participation as the active participation in the community that encompasses a range of values and behaviors related to involvement in one’s local community and broader society (Christens et al. 2011). These values and behaviors may include, but are not limited to, writing a letter or participating in community garden projects that work toward improving the physical conditions of a community or neighborhood (Chan et al. 2014; Rosen 2019).

Civically engaged youth are critical to improving and maintaining local, national, and global communities (Martinez et al. 2012; Rosen 2019). Research among youth of color has noted that these young people may experience lower levels of “conventional” civic knowledge, political attitudes, and forms of political participation (e.g., voting, contacting policy makers or elected representatives), when compared to White adolescents (Ginwright 2015). However, they may be more inclined to participate community service events, religious organizations, and in politically motivated cultural and artistic expression (Ginwright et al. 2006). Community civic participation has also been associated with psychological sense of community and ethnic group attachment, as well as both intrapersonal (Lardier 2018) and cognitive psychological empowerment among youth of color (Lardier et al. 2019a). The existing literature seems to, therefore, support the hypothesis that community civic participation is not only positively associated with psychological sense of community but also an important developmental process that is associated with ethnic identity development, well-being, and the empowerment of youth of color.

Ethnic Identity and Social Justice Orientation: The Relationship with Psychological Sense of Community, Community Civic Participation, and Intrapersonal and Cognitive Psychological Empowerment

This section examines the relationship ethnic identity and social justice orientation have with psychological sense of community, community civic participation, and both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment. Few studies have examined the intersection of these variables (exceptions include Christens et al. 2016). This is noteworthy because the existing research indicates that both community civic participation and psychological sense of community are associated with ethnic-racial identity (Lardier et al. 2018a, b, c, d; Lardier 2018, 2019), a greater awareness of social injustices, and both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment (Lardier et al. 2019a).

Ethnic identity is defined as an individual’s perceptions, cognitions, and emotions relating to how they understand and relate to their ethnic awareness (Phinney 1989, 1996). Ethnic identity develops over time as an individual perceives themselves within their cultural groups and begins to understand the values and customs associated with that group (Phinney and Ong 2007). Among youth of color, ethnic identity formation is important during the adolescent developmental period (Rivas-Drake et al. 2014). Current scholarship uses an integrated conceptualization of ethnic identity development that considers both the process through which youth come to understand their membership in an ethnic-racial group, as well as the content or their ethnic-racial identity beliefs (Umana-Taylor et al. 2014). Identity development, however, can be complicated, as those who belong to ethnic groups that have been historically marginalized may have difficulty developing a positive sense of self (Candelario 2007).

Research on ethnic identity has noted that ethnic-group membership and shared experiences, as well as culture, history, and ethnic origin is associated with greater community belongingness or sense of community, civic participation, and awareness of social justice issues (Christens et al. 2013; Watts et al. 2011). Youth involved in their community, particularly activities with their ethnic-racial group, have access to more sources of social support, greater self-esteem (Fisher et al. 2014) and feel greater self-efficacy in the sociopolitical domain (Christens et al. 2018; Gutierrez 1995; Lardier et al. 2019a). Furthermore, youth of color who have a greater sense of their ethnic racial identity feel empowered (Gutierrez 1995; Hipolito-Delgado and Zion 2015; Lardier et al. 2019a).

Similarly, having a social justice orientation that stresses collective action to reduce injustices (Westheimer and Kahne 2004) has been identified as a key component in youth development and the empowerment process (Christens et al. 2018, 2019a; Shaw Lardier 2014). A social justice orientation incorporates a heightened knowledge of social issues, while coupling this knowledge with skills that promote deeper inquiry, problem-solving, and action (Shaw et al. 2014). Ginwright and Cammarota (2002) specifically discussed that justice-informed frameworks enable youth to develop an understanding of sociopolitical conditions and injustices, driving community action, ethnic group attachment, and empowerment. For instance, having a social justice orientation is not only a consequence of previous injustices (Schmitt et al. 2005) but also a predictor of empowerment, challenging power, and addressing the root causes of social oppression (Cattaneo and Chapman 2010; Christens et al. 2018; Ginwright and James 2002; Zeldin et al. 2018). Some have also identified that a social justice orientation may mediate experiences related to injustice on behavioral outcomes (Giovannelli et al. 2018), as well as the association between social responsibility and civic engagement (Hope and Bañales 2019). Therefore, it may be that there is a link between social justice orientation and empowerment-based variables.

Taken together, the present research supports the association psychological sense of community, community civic participation, ethnic identity, and social justice orientation have with both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment. Further research is needed to examine the effects among these conceptually related variables. It may be equally important to understand the mediating role of both ethnic identity and social justice orientation given that the existing research supports the notion that ethnic identity has performed as a mediator between community-based predictors and intrapersonal psychological empowerment (Garcia-Reid et al. 2013; Lardier 2018, 2019). It is also reasonable to conclude that social justice orientation will perform as an important mediator given that collective group identity and civic engagement is often positively associated with a critical awareness of social justice concerns, and the interest in eradicating such injustices (Diemer and Rapa 2016; Dinzey-Flores et al. 2019; Lardier et al. 2019a; Rivas-Drake et al. 2014; Umana-Taylor et al. 2014).

The Purpose

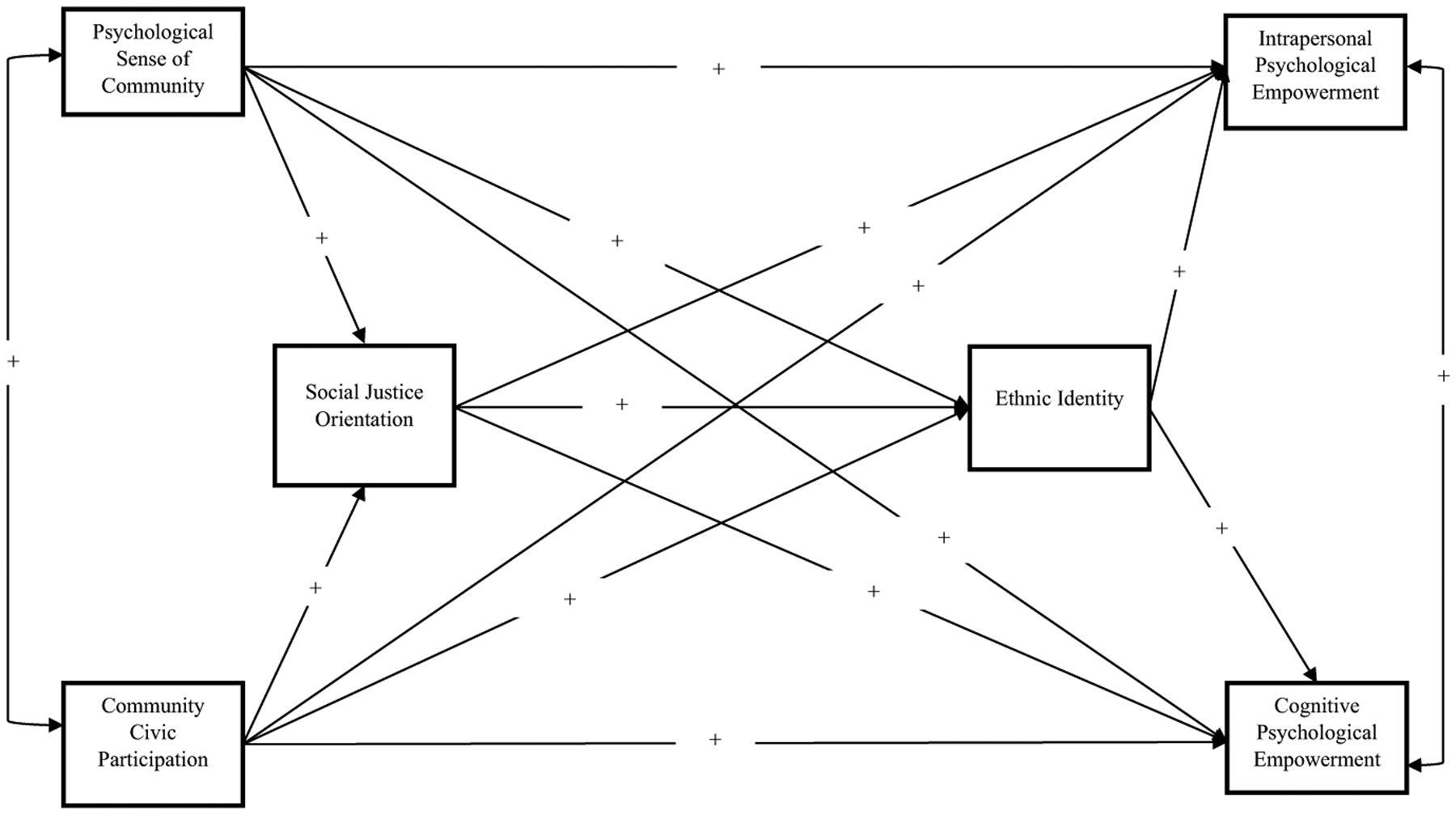

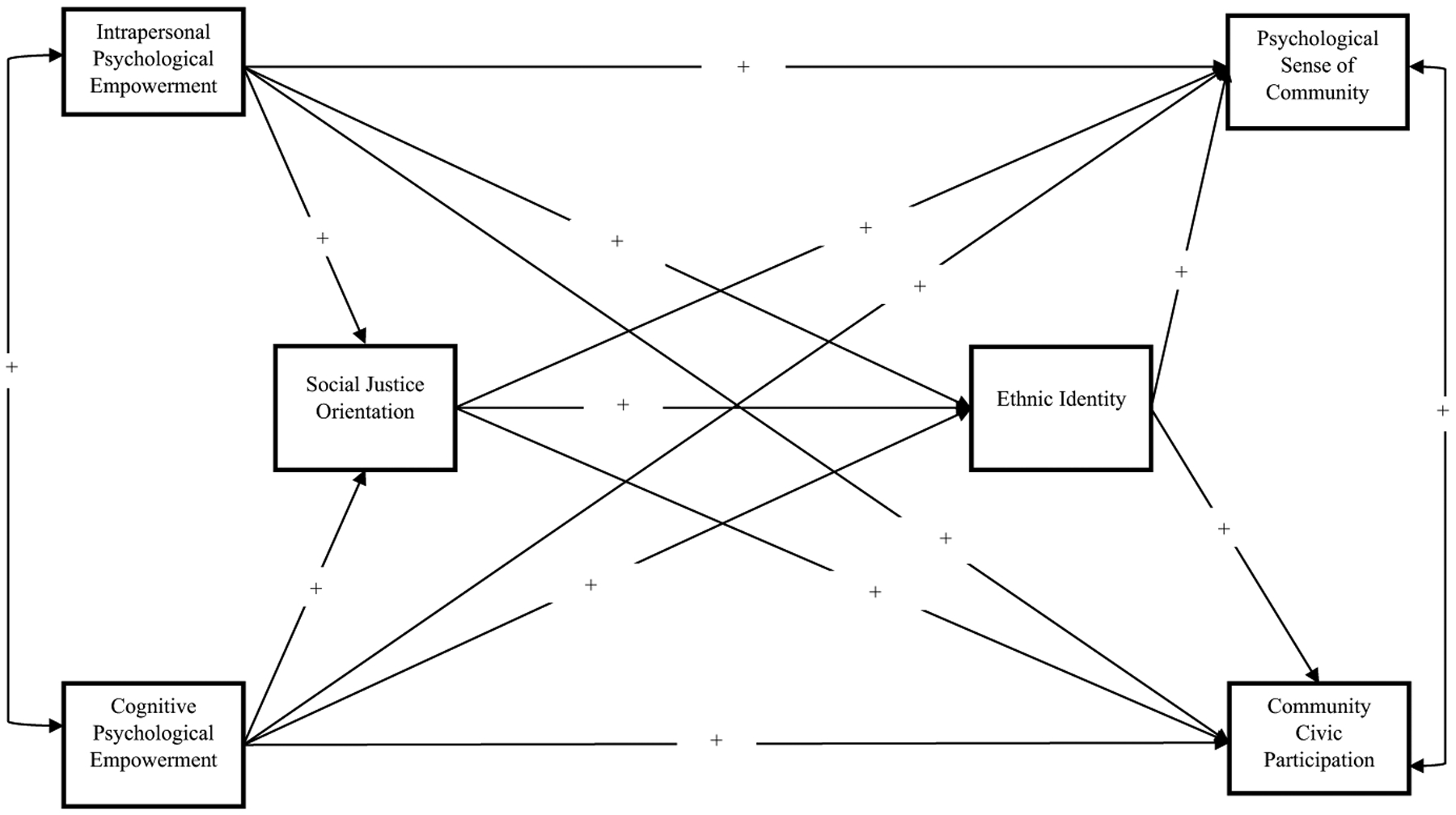

Drawing on a sample of racial-ethnic minority urban youth, we hypothesized (see Fig. 1) that both psychological sense of community and community civic participation would be directly associated with both ethnic identity and social justice orientation, and indirectly related to both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment. We also generated an alternative path model (see Fig. 2) to assess the hypothesized ordering of relationships between variables given the lack of longitudinal data (Thompson 2000). Results provide important thoughts for empowerment research and youth work programming in under-served communities.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model of psychological sense of community and community civic engagement predicting intrapersonal psychological empowerment and cognitive psychological empowerment through ethnic identity and social justice orientation among youth of color

Fig. 2.

Alternative model of intrapersonal psychological empowerment and cognitive psychological empowerment predicting psychological sense of community and community civic engagement through social justice orientation and ethnic identity among youth of color

Methods

Sample and Design

This study was part of a larger Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Minority AIDS Initiative grant. Data collected helped to inform environmental strategies and prevention-intervention protocols specific to the grant initiative and target community. Students were recruited through their high school’s physical education and health classes. This allowed all students who attended school an equal opportunity to participate in the study. Students who returned both parental consent and student assent forms were eligible to complete the survey.

Participants included 383 students from an urban school district in northeastern quadrant of the United States. Students were predominantly Hispanic/Latinx (75%), female (53.1%) and between 13 and 15 years of age (51%; range 13–18 years of age). Approximately, 29.2% were in 9th grade, 45.7% in 10th grade, 6% in 11th grade, and 19.1% in 12th grade. Majority of students were on free or reduced lunch (70%), a proxy for low socioeconomic status.

Measurement

Data were collected using a 120-item pencil-based survey. Various outcome behaviors were assessed based on measures from the Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance Survey (YRBSS; e.g., 30-day substance use, sexually risky behavior; Kann et al. 2014). In addition, the survey also captured data relevant to intrapersonal psychological empowerment, psychological sense of community, community civic engagement, ethnic identity, and social justice orientation. Five measures were included in the current analysis. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, associated alpha levels (Cronbach’s α), and a correlation matrix for all measured variables.

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptive statistics for study variables (N = 383)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological Sense of Community | – | .10* | .12* | .12** | .41** | .20** |

| 2. Ethnic Identity | – | .11** | .14** | .12** | .12** | |

| 3. Community Civic Participation | – | .10** | .12* | .12** | ||

| 4. Social Justice Orientation | – | .15** | .39** | |||

| 5. Intrapersonal Psychological Empowerment | – | .30** | ||||

| 6. Cognitive Psychological Empowerment | – | |||||

| Mean | 3.18 | 3.62 | 3.18 | 3.76 | 3.30 | 3.75 |

| SD | .80 | .85 | 1.20 | .68 | .62 | .68 |

| Range | 1–5 | 1–4 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

| α | .88 | .80 | .80 | .83 | .89 | .89 |

p < .05;

p < .01

Psychological Sense of Community

Youth participants completed the 8-item Brief Sense of Community Scale (BSCS), measuring psychological sense of community (McMillan and Chavis 1986; Peterson et al. 2008). The BSCS was designed to assess four-dimensions of psychological sense of community: needs fulfillment, group membership, influence, and emotional connection. Sample items included: “I feel connected to this neighborhood. I have a say about what goes on in my neighborhood.” Youth participants responded on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Prior studies have demonstrated the reliability of this scale among U.S. Hispanic/Latinx and African America/Black urban youth (overall scale: Cronbach’s α = .85, Mean [M] = 3.08, Standard Deviation [SD] = .89; Lardier et al. 2018d). For the current study, scores were averaged and combined.

Community Civic Participation

Youth participants also reported on their community civic participation using a 5-item measure from the Student Survey of Risk and Protective Factors/Community Participation scale (Arthur et al. 2002). Sample item included: “How often do you go to meetings/engage in activities in your community?” Participants responded to items using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from never (1) to almost every day (4). Speer and Peterson (2000) demonstrated support for the reliability of this scale, and through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) identified a single underlying participation scale. Scores were average and combined.

Ethnic Identity

Youth participants responded on their ethnic identity using a 6-item ethnic identity measure. This measure was developed by the federal funding agency. Sample item included: “I participate in cultural practices of my own ethnic group.” Participants responded to each item on a four-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Prior studies have indicated support for this 6-item measure (e.g., Lardier et al. 2019a). Scores were averaged and combined.

Social Justice Orientation

Youth participants completed a 4-item scale that assessed identification as a justice-oriented citizen or an orientation to civic life and social issues that stress collective action to reduce injustices (Westheimer and Kahne 2004). Sample items included: “After high school, I will work with others to change unfair laws,” and “I think it is important to challenge things that are not equal in society” (Flanagan et al. 2009). Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Scores were averaged and combined.

Cognitive Psychological Empowerment

Youth completed 14-items from the Cognitive Empowerment Scale (CES). Participants responded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Several studies have engaged in rigorous evaluations of the CES among various youth populations (e.g., urban youth, Portuguese Youth) and confirmed the factor structure of the CES encompassing three separate subscales: power through relationships, nature of problem/political functioning and shaping ideologies (e.g., Lardier et al. 2020; Rodrigues et al. 2018; Speer et al. 2019). In these studies, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .77 to .89. Sample items included: “Only by working together can we (citizens) make changes in [city name],” and “When community members and students work for change, it doesn’t take long for them to experience negative consequences.” For the current study, the four-item measure of power through relationships (Cronbach’s α = .81), the four-item measure of nature of power/political functioning (Cronbach’s α = .73), and the six-item measure of shaping ideologies (Cronbach’s α = .81) were averaged and combined.

Intrapersonal Psychological Empowerment

Youth participants completed the 17-item version of the SPCS-Y that measures intrapersonal psychological empowerment (Lardier et al. 2018c; Peterson et al. 2011). Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Prior studies have engaged in rigorous evaluations of the SPCS-Y among youth samples and supported that the SPCS-Y encompasses two specific subscales: leadership competence and policy control (Lardier et al. 2018c; Opara et al. 2019; Peterson et al. 2011). In these studies, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .88 to .89. Sample items included: “I am a leader in groups,” and “My friends and I can really understand what’s going on with my community or school.” For the current study, items from the 17-item measure were averaged and combined.

Data Analysis Plan

Preliminary Analysis

Using Little’s MCAR Test, data were examined for type and level of missingness. Analyses revealed that data were likely missing completely at random (MCAR) (χ2 = [df = 70] 117.88, p = .12). Missing data were handled using maximum likelihood (ML) estimations through AMOS SEM software. Handling missing data through AMOS SEM allows for a theoretically informed direct approach to missing data through modeling, opposed to other imputation methods, which can be designated as indirect (Byrne 2013).

Next, normality, descriptive statistics, alpha level reliabilities (Cronbach’s α), and a bivariate correlation matrix were examined. Data appeared to have relatively normal distribution (see Table 1). No issues of multicollinearity were noted. No conspicuous outliers were noted. Analyses through AMOS SEM software examines the covariance matrix through ML estimations and sidesteps issues associated with influential outliers that would impact model fit, normality, and limits the impact on parameter estimates (Hancock and Liu 2012). Gender, age, Hispanic/Latinx ethnic-identity, and African American/Black racial-identity were examined for inclusion in path analysis model. No differences were present between covariates and main analytic variables.

Main Analytic Procedures

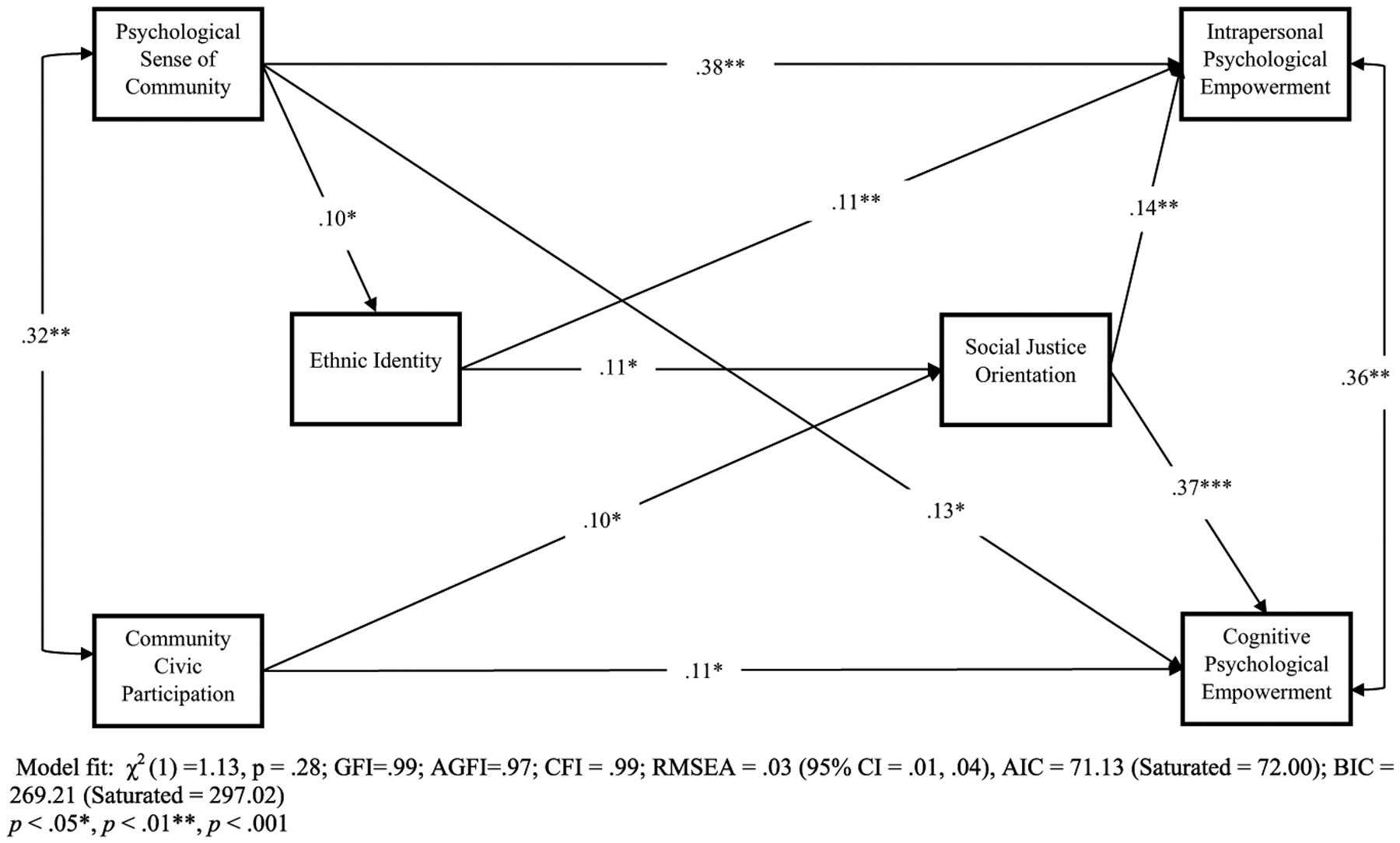

Path analyses were conducted using ML procedures to analyze the variance–covariance matrix through AMOS SEM (Arbuckle 2013). Path analyses were used to examine the association community civic participation and psychological sense of community had on cognitive and intrapersonal psychological empowerment through both ethnic identity and social justice orientation (see Fig. 3). Model fit is considered good if the χ2 value is Non-significant, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) are ≥ .95 (adequate if ≥ .90), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is ≤ .06 (adequate if ≤ .08) (West et al. 2012). The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were used to compare model fit between models (West et al. 2012). Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals were also used to test the significance of the mediational associations through ethnic identity and social justice orientation. Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals provide more accurate intervals for small samples (Efron and Tibshirani 1994), skewed distributions of the indirect effect estimates (Mallinckrodt et al. 2006), and improve the power of the test of the indirect effect (Shrout and Bolger 2002).

Fig. 3.

Standardized beta weights of psychological sense of community and community civic engagement predicting intrapersonal psychological empowerment and cognitive psychological empowerment through ethnic identity and social justice orientation among youth of color (N = 383)

Limitations are present with regard to examining mediation cross-sectionally (Kline 2015). Sensitivity analyses with alternative modeling specifications were employed to address potential methodological biases associated with testing mediation cross-sectionally (Thompson 2000). See Fig. 2, for hypothesized alternative model.

Results

All main analytic variables were correlated (see Table 1). See Fig. 3 for over-identified path model, which displays only statistically significant paths and presents standardized beta weights. The unconstrained model showed good overall model fit for the sample data: χ2 (1) = 1.13, p = .28; GFI = .99; AGFI = .97; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03 (95% CI .01, .04), AIC = 71.13 (Saturated = 72.00); BIC = 269.21 (Saturated = 297.02).

Direct paths were present between psychological sense of community and ethnic identity (p < .05), as well as both intrapersonal (p < .001) and cognitive psychological empowerment (p < .01). Community civic participation was directly associated with social justice orientation (p < .05) and cognitive psychological empowerment (p < .05); no direct paths were present to ethnic identity and intrapersonal psychological empowerment. Ethnic identity had a direct relationship with social justice orientation (p < .001), intrapersonal psychological empowerment (p < .01), and cognitive psychological empowerment (p < .001). Social justice orientation was directly linked to both intrapersonal (p < .001) and cognitive psychological empowerment (p < .001).

Using bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals, the following indirect associations were present through ethnic identity: Community civic participation and both cognitive (indirect effect = .03, 95% CIs .01–.04, p = .02) and intrapersonal psychological empowerment (indirect effect = .03, 95% CIs .01–.04, p = .03); psychological sense of community and both cognitive (indirect effect = .04, 95% CIs .01–.05, p = .02) and intrapersonal psychological empowerment (indirect effect = .03, 95% CIs .01–.04, p = .03). The following indirect relationships were also present through social justice orientation: community civic participation and both cognitive (indirect effect = .05, 95% CIs .01–.07, p = .05) and intrapersonal psychological empowerment (indirect effect = .02, 95% CIs .01–.04, p = .04); psychological sense of community and both cognitive (indirect effect = .04, 95% CIs .01–.04, p = .04) and intrapersonal psychological empowerment (indirect effect = .02, 95% CIs .01–.04, p = .04).

The decompensation of effects indicated that ethnic identity mediated approximately 33% of the effect between community civic participation and both cognitive and intrapersonal psychological empowerment, as well as 13% and 10% of the effect psychological sense of community had on both cognitive and intrapersonal psychological empowerment, respectively. Social justice orientation mediated approximately 83% of the effect community civic participation had on both cognitive and intrapersonal psychological empowerment. Social justice orientation mediated approximately 27% of the effect psychological sense of community had on cognitive psychological empowerment and 31.7% of the effect on intrapersonal psychological empowerment.

Analyses of the alternative model (Fig. 2) indicated that the overall model fit to the data was less than adequate, when compared to that of the original model. Fit indices were as follows: χ2 (1) = 2.15, p = .01. Both were outside the range of acceptable model-to-data fit. The other fit indices also indicated less than adequate model fit. The RMSEA, .10 (90% CI .08, .15), GFI = .93, AGFI = .94, TLI = .86, AIC = 55.23 (Saturated = 72.00); BIC = 269.21 (Saturated = 297.02). Comparing the AIC and BIC, the hypothesized model provided the best fit to the sample data, with the AIC (71.13) for the hypothesized model closest to the saturated model of 72.00, which indicates that the hypothesized model provided a better fit to the sample data (West et al. 2012). The BIC was 269.21 for the hypothesized model and 289.90 for the alternative model, with a difference greater than 10.00 present, indicating that the hypothesized model with the lower BIC had a better model-fit (West et al. 2012). Based on these findings, the most probable order of association is that psychological sense of community and community civic participation have an association with both cognitive and intrapersonal psychological empowerment through both ethnic identity and social justice orientation.

Discussion

First, our findings revealed that both ethnic identity and social justice orientation mediated the association between community civic participation and psychological sense of community and both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment. Specifically, ethnic identity mediated the association psychological sense of community had on intrapersonal psychological empowerment and social justice orientation, which provides preliminary evidence indicating that psychological sense of community is positively associated with ethnic identity development and has a connection to youth’s perceived intrapersonal psychological empowerment (Lardier 2018, 2019). Results also show that participation in one’s ethnic group may make one more interested in civic life, addressing social issues that stress collective action to reduce injustices, and be more critically aware of the sociopolitical environment. It is reasonable to conclude that psychological sense of community or community belongingness may be predictive of collective social group identity, which in-turn leads to critical awareness and perceived ability to enact actionable change (Christens et al. 2018; Gutierrez 1989; Lardier 2019; Lardier et al. 2019a, b).

Regarding community civic participation, social justice orientation mediated 57% and 50% of the relationship with both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment, respectively. These findings point toward the role community civic participation has in drawing attention to social injustices and promoting youth’s critical awareness of issues within the sociopolitical domain, as well as youth’s perceived ability to enact change (Christens et al. 2018; Diemer and Rapa 2016; Lardier et al. 2019a, b). If we consider both empowerment and models of critical consciousness, community civic participation influences individuals’ awareness of social injustices and their awareness of their social world, how power is generated and maintained, and their perceived ability to be leaders and enact change in the sociopolitical domain (Diemer and Rapa 2016; Lardier 2019). As Luque-Ribelles and Portillo (2009) stress, through community civic participation, people change along with their relationships in their context, are critically aware of power, learn how to enact sociopolitical change, and rupture hierarchical structures of inequality. Hence, community civic participation “broadens the spectrum of traditional youth development”, promoting youth critical awareness and activism (Kwon 2013, p. 19).

Second, results display the theoretical path between both ethnic identity and both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment, as well as to a social justice orientation. Of interest was the relationship ethnic identity had with social justice orientation and indirectly with both intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment. These findings provide preliminary evidence on the empirical role of ethnic identity among dimensions of empowerment and related mechanisms, including social justice orientation. In particular, results showed that individuals with stronger internalized perceptions of their ethnic identity may experience empowered ways of thinking and feeling, and that these perceptions may be mediated through an awareness of social injustices (Christens et al. 2018; Gutierrez 1989; Lardier 2018, 2019; Umana-Taylor et al. 2014). For that reason, urban youth of color who are provided access to community participation activities and have a strong psychological sense of community may develop a stronger ethnic identity, which limits perceived feelings of isolation and augments psychological empowerment (Lardier 2019). In addition, urban youth of color with strong ethnic group identities may be aware of social injustices, due to the intersection of their marginalized identities and living in under-served, segregated communities that require that these youth be critically aware of their social circumstances (Christens et al. 2018; Lardier et al. 2019a, b; Speer and Peterson 2000).

The relationships identified, heretofore, specify the importance of supportive community environments and community civic participation in promoting ethnic group identity, a social justice orientation, and in-turn aspects of empowerment that relate to perceived ability to enact social change and a critical awareness of power and social inequality. We can discern that participation in civic engagement and the formation of a positive sense of community may shift adolescent developmental pathways and form a cascading effect, wherein youth pursue “thoughtful strategies for social change [and] may simultaneously empower youth to view themselves and personal trajectories differently” (Strobel et al., p. 198). Said in a different way, youth who are granted opportunities for civic engagement and who develop a sense of belongingness may be aware of injustices and social issues, and in-turn develop conceptions for justice, equity, and change.

Implications for Youth Programming

Youth-based organizations are often stymied in their ability to engage youth in critical and empowering ways of being (Kwon 2013). This is due to funding mechanisms stressing an individualized focus of youth development, opposed to stressing collective action and youth organizing as important components to how youth make meaning in their lives and engage their social world (Kwon 2013). An important question for youth-based community programs is how to foster not only youth belongingness, but also community civic participation, ethnic identity, and a critical awareness of social injustices in order to understand and challenge power and feel capable of enacting change in the sociopolitical realm.

Findings provide insight into the importance of providing youth opportunities for direct civic engagement and fostering a sense of belongingness to facilitate ethnic-group identity, critical awareness, and sociopolitical agency. Constructing youth as social and political participants is not about “citizens in the making” but instead realizing that when given the opportunity youth are capable of political agency and activism. This broadens our understanding of youth development and realizes the critical juncture empowerment can have in promoting social belongingness and aspects of critical consciousness (Christens et al. 2018). It is important to incorporate youth in various types of community projects and opportunities for social engagement to develop outcomes examined in this study (Lardier et al. 2019a, b). Youth-based community programs that find perceptive ways of engaging youth outside of the requirements of their funding stream can be useful locations to develop politically active and engaged actors of young people (Lardier et al. 2019a, b).

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. First the study was cross-sectional; therefore, the direction of effects and mediational effects cannot be firmly established. While important results were identified, future research needs to replicate findings using mediation analyses longitudinally. Such analyses would help to uncover developmental processes and further unpack the temporal order of variables overtime (Kline 2015). While one study has examined two waves of data focused on community participation and psychological empowerment, as part of a larger evaluation study (Christens et al. 2011), research is needed that examines empowerment constructs longitudinally. Second, given the heterogeneity present within Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black populations, future research should examine within-group differences. This would allow for a nuanced inspection of the mechanisms tested in this study and expand our understanding of the empowerment literature. And third, although two dimensions of psychological empowerment were examined in this study (i.e., intrapersonal and cognitive psychological empowerment), which is unique, the Cognitive Empowerment Scale (CES) specifically used to examine cognitive psychological empowerment has not been thoroughly validated among diverse groups of youth (exceptions include Lardier et al. 2020). Future research is urged to validate the CES among various groups of youth, as well as the entire psychological empowerment nomological structure (exceptions include Rodrigues et al. 2018).

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the current literature that considers how to develop youth empowerment, particularly youth psychological empowerment. Findings display that community civic participation, psychological sense of community, ethnic identity and social justice orientation may influence not only youth development, but also in how youth develop psychological empowerment. The results provide an argument for youth to be actively involved in the sociopolitical realm and as change agents within their community. Notably, this study moves away from an ‘at-risk’ perspective and instead examines the ways in which we can empower youth to be change agents. As researchers and practitioners of positive youth development, “we must consider the empowering cultural wealth within and among urban youth and their communities,” create community and youth partnerships (Lardier 2019, p. 100).

Funding

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP), Grant No. SP-15104.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Ijeoma Opara (or second co-author) received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32 DA007233) training grant as a predoctoral fellow. Points of view, opinions, and conclusions in this paper do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government.

References

- Arbuckle JL (2013). Amos 22 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, & Baglioni AJ Jr. (2002). Measuring risk and protective factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors: The communities that care youth survey. Evaluation Review, 26(6), 575–601. 10.1177/019384102237850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins B, LeCompte KN, & Bauml M (2018). Developing students’ understandings of citizenship and advocacy through action civics. Social Studies Research and Practice, 13(2), 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2013). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Candelario GE (2007). Black behind the ears: Dominican racial identity from museums to beauty shops. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo LB, & Chapman AR (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659. 10.1037/a0018854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WY, Ou SR, & Reynolds AJ (2014). Adolescent civic engagement and adult outcomes: An examination among urban racial minorities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1829–1843. 10.1007/s10964-014-0136-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD (2012). Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 114–128. 10.1007/s10464-011-9483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD (2019). Community power and empowerment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD, Byrd K, Peterson NA, & Lardier DT (2018). Critical hopefulness among urban high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1649–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD, Collura JJ, & Tahir F (2013). Critical hopefulness: A person-centered analysis of the intersection of cognitive and emotional empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(1–2), 170–184. 10.1007/s10464-013-9586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD, Krauss SE, & Zeldin S (2016). Malaysian validation of a sociopolitical control scale for youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(4), 531–537. 10.1002/jcop.21777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christens BD, Peterson NA, & Speer PW (2011). Community participation and psychological empowerment: Testing reciprocal causality using a cross-lagged panel design and latent constructs. Health Education & Behavior, 38(4), 339–347. 10.1177/1090198110372880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Jahromi P, & Meeus W (2012). Identity and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 521–532. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, & Rapa LJ (2016). Unraveling the complexity of critical consciousness, political efficacy, and political action among marginalized adolescents. Child Development, 87(1), 221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinzey-Flores ZZ, Lloréns H, López N, & Quiñones M (2019). Black Latina womanhood: From Latinx fragility to empowerment and social justice praxis. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 47(3), 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, & Tibshirani RJ (1994). An introduction to the bootstrap. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elfassi Y, Braun-Lewensohn O, Krumer-Nevo M, & Sagy S (2016). Community sense of coherence among adolescents as related to their involvement in risk behaviors. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(1), 22–37. 10.1002/jcop.21739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, & Flanagan C (2013). Adolescents’ civic engagement and alcohol use: Longitudinal evidence for patterns of engagement and use in the adult lives of a British cohort. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 435–446. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S, Reynolds JL, Hsu W-W, Barnes J, & Tyler K (2014). Examining multiracial youth in context: Ethnic identity development and mental health outcomes. Journal of youth and adolescence, 43(10), 1688–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA, Syvertsen AK, Gill S, Gallay LS, & Cumsille P J. J. o. y. a. a.(2009). Ethnic awareness, prejudice, and civic commitments in four ethnic groups of American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(4), 500–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forenza B, & Lardier DT Jr. (2017). Sense of community through supportive housing among foster care alumni. Child & Youth Care Forum, 95(2), 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reid P, Hamme Peterson C, Reid RJ, & Peterson NA (2013). The protective effects of sense of community, multigroup ethnic identity, and self-esteem against internalizing problems among Dominican youth: Implications for social workers. Social Work in Mental Health, 11(3), 199–222. 10.1080/15332985.2013.774923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gattino S, De Piccoli N, Fassio O, & Rollero C (2013). Quality of life and sense of community. A study on health and place of residence. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(7), 811–826. 10.1002/jcop.21575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S (2015). Hope and healing in urban education: How urban activists and teachers are reclaiming matters of the heart. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, Cammarota J, & Noguera P (2006). Beyond resistance!: Youth activism and community change: New democratic possibilities for practice and policy for America’s youth. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S, & James T (2002). From assets to agents of change: Social justice, organizing, and youth development. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2002(96), 27–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannelli I, Pacilli MG, Pagliaro S, Tomasetto C, & Barreto M (2018). Recalling an unfair experience reduces adolescents’ dishonest behavioral intentions: The mediating role of justice sensitivity. Social Justice Research, 31(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L (1989). Critical consciousness and Chicano identity: An exploratory analysis. In Romero G (Ed.), Estudios Chicanos and the politics of community (pp. 35–53). Berkeley, CA: NACS (National Association for Chicano Studies) Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez LM (1995). Understanding the empowerment process: Does consciousness make a difference? Social Work Research, 19(4), 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, & Liu M (2012). Bootstrapping standard errors and data-model fit statistics in structural equation modeling. In Hoyle RH (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 296–324). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hipolito-Delgado CP, & Zion S (2015). Igniting the fire within marginalized youth: The role of critical civic inquiry in fostering ethnic identity and civic self-efficacy. Urban Education. 10.1177/0042085915574524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hope EC (2016). Preparing to participate: The role of youth social responsibility and political efficacy on civic engagement for Black early adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 9(3), 609–630. [Google Scholar]

- Hope EC, & Bañales J (2019). Black early adolescent critical reflection of inequitable sociopolitical conditions: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34(2), 167–200. [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaky H, & York AS (2000). Sociopolitical control and empowerment: An extended replication. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 407–415. 10.1002/1520-6629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. (2014). Youth risk behavior survey (YRBS) 2015 standard questionnaire item rationale. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2015). The mediation myth. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37(4), 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SA (2013). Uncivil youth: Race, activism, and affirmative governmentality. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr. (2018). An examination of ethnic identity as a mediator of the effects of community participation and neighborhood sense of community on psychological empowerment among urban youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology. 10.1002/jcop.21958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr. (2019). Substance use among urban youth of color: Exploring the role of community-based predictors, ethnic identity, and intrapersonal psychological empowerment. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2018a). The interacting effects of psychological empowerment and ethnic identity on indicators of well-being among youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 489–501. [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2019a). The examination of cognitive empowerment dimensions on intrapersonal psychological empowerment, psychological sense of community, and ethnic identity among urban Youth of color. The Urban Review, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr., Herr KG, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2018b). Adult youth workers’ conceptions of their work in an under-resourced community in the United States. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr., MacDonnell M, Barrios VR, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2017). The moderating impact of neighborhood sense of community on predictors of substance use among Hispanic urban youth. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 15(4), 1–26. 10.1080/15332640.2016.1273810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT, Opara I, Bergeson C, Herrera A, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2019b). A study of psychological sense of community as a mediator between supportive social systems, school belongingness, and outcome behaviors among urban high school students of color. Journal of Community Psychology. 10.1002/jcop.22182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT, Opara I, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2020). The cognitive empowerment scale: Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis among youth of color. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 10.1007/s10560-019-00647-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr., Reid RJ, & Garcia-Reid P (2018c). Validation of an abbreviated Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth among a sample of under resourced urban youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 996–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardier DT Jr., Reid RJ, & Garcia-Reid P (2018d). Validation of the Brief Sense of Community Scale among youth of color from an underserved urban community. Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 1062–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque-Ribelles V, & Portillo N (2009). Gendering peace and liberation: A participatory-action approach to critical consciousness acquisition among women in a marginalized neighborhood. In Sonn C & Montero M (Eds.), Psychology of Liberation (pp. 277–294). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt B, Abraham WT, Wei M, & Russell DW (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 372–378. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ML, Penaloza P, & Valenzuela C (2012). Civic commitment in young activists: Emergent processes in the development of personal and collective identity. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 474–484. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW (1996). Sense of community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24, 315–325. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW, & Chavis DM (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23. 10.1002/1520-6629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Opara I, Rivera Rodas EI, Lardier DT, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2019). Validation of the abbreviated socio-political control scale for youth (SPCS-Y) among urban girls of color. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 10.1007/s10560-019-00624-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NA (2014). Empowerment theory: Clarifying the nature of higher-order multidimensional constructs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(1–2), 96–108. 10.1007/s10464-013-9624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NA, Peterson CH, Agre L, Christens BD, & Morton CM (2011). Measuring youth empowerment: Validation of a sociopolitical control scale for youth in an urban community context. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(5), 592–605. 10.1002/jcop.20456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NA, & Reid RJ (2003). Paths to psychological empowerment in an urban community: Sense of community and citizen participation in substance abuse prevention activities. Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1), 25–38. 10.1002/jcop.10034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NA, Speer PW, Peterson CH, Powell KG, Treitler P, & Wang Y (2017). Importance of auxiliary theories in research on university-community partnerships: The example of psychological sense of community. Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice, 1(1), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1989). Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9(1–2), 34–39. 10.1177/0272431689091004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1996). When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist, 51(9), 918–927. 10.1037/0003-066x.51.9.918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D (2012). Ethnic identity and adjustment: The mediating role of sense of community. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(2), 210–215. 10.1037/a0027011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40–57. 10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M, Menezes I, & Ferreira PD (2018). Validating the formative nature of psychological empowerment construct: Testing cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and relational empowerment components. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1), 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen SM (2019). “So much of my very soul”: How youth organizers’ identity projects pave agentive pathways for civic engagement. American Educational Research Journal, 56(3), 1033–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological methods, 7(4), 422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M, Gollwitzer M, Maes J, & Arbach D (2005). Justice sensitivity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Brady B, McGrath B, Brennan MA, & Dolan P (2014). Understanding youth civic engagement: Debates, discourses, and lessons from practice. Community Development, 45(4), 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW (2000). Intrapersonal and interactional empowerment: Implications for theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 51–61. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW, & Peterson NA (2000). Psychometric properties of an empowerment scale: Testing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains. Social Work Research, 24(2), 109–118. 10.1093/swr/24.2.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW, Peterson NA, Armstead TL, & Allen CT (2012). The influence of participation, gender, and organizational sense of community on psychological empowerment: The moderating effects of income. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 103–113. 10.1007/s10464-012-9547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW, Peterson NA, Christens BD, & Reid RJ (2019). Youth cognitive empowerment: Development and evaluation of an instrument. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64, 528–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Távara MG, & Cueto RM (2015). Sense of community in a context of community violence. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 43(4), 304–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B (2000). Ten commandments of structural equation modeling. In Grimm LG & Yarnold PR (Eds.), Reading and understanding more multivariate statistics. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE Jr., Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, Diemer MA, & Voight A (2011). Critical consciousness: Current status and future directions. In Flanagan CA & Christens BD (Eds.), Youth civic development: Work at the cutting edge. New directions for child and adolescent development (Vol. 134, pp. 43–57). 10.1002/cd.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Taylor AB, & Wei W (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In Hoyle RH (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 209–231). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer J, & Kahne J (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke LA, & Speer PW (2011). The mediating influence of organizational characteristics in the relationship between organizational type and relational power: An extension of psychological empowerment research. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(8), 972–986. [Google Scholar]

- Zeldin S, Gauley JS, Barringer A, & Chapa B (2018). How high schools become empowering communities: A mixed-method explanatory inquiry into youth–adult partnership and school engagement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61, 358–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581–591. 10.1007/bf02506983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In Rappaport J & Seidman E (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 44–59). New York, NY: Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, & Zahniser JH (1991). Refinements of sphere-specific measures of perceived control: Development of a sociopolitical control scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 19, 189–204. 10.1002/1520-662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zurcher LA Jr (1970). The Poverty Board: Some Consequences of “Maximum Feasible Participation” 1. Journal of Social Issues, 26(3), 85–107. [Google Scholar]