Abstract

Research Findings:

Banking Time is a set of techniques designed to promote positive, supportive relationships through 1-on-1 interactions between teachers and children. Web-based training resources were made available to 252 preschool teachers who received different levels of support as a component of a professional development intervention, and the purpose of this study was to examine teachers’ implementation of Banking Time. Teachers with greater levels of professional development support were more likely to implement Banking Time with children in their classes. Teachers were more likely to choose to implement Banking Time with children who had lower social-emotional skills (e.g., more problem behaviors). Teachers developed greater relational closeness with children who participated in Banking Time than with children who did not participate.

Practice or Policy:

The implications of these preliminary findings for fostering supportive teacher–child relationships are discussed.

Relationships between teachers and children that are characterized by warmth, closeness, and a lack of conflict promote children’s opportunities to learn within classrooms and their subsequent adaptation to and success in the school environment. Positive teacher–child relationships are particularly important during children’s initial entry into school, because it is during this time that children establish internal working models of the school social environment that create expectations and norms for adaptive behaviors within this setting (e.g., Entwisle & Hayduk, 1988; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1997). Research indicates that positive relationships developed with teachers during the early school years impact children’s academic and social development (e.g., Birch & Ladd, 1997; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Pianta Howes, Burchinal, Bryant, Clifford, Early, et al., 2005) and a variety of interventions have been developed to address social-emotional development in the classroom in order to prevent future social and academic problems that children may experience in school. Although several classroom-based interventions targeting social-emotional outcomes have been developed in recent years, no intervention specifically addresses the teacher–child relationship as the target outcome. Banking Time (Pianta & Hamre, 2001) is a classroom-based intervention in which teachers and children spend one-on-one time together engaging in the child’s interests to build stronger relationships.

Although school-based prevention programs are often available to teachers, few studies describe the processes of implementing interventions (Durlak, 1997), such as the quality of delivery, dosage, characteristics of teachers and classrooms that promote intervention implementation, and characteristics of children with whom teachers select to participate in interventions (Greenberg, Domitrovich, Graczyk, & Zins, 2000; Hall & Hord, 1987; Hopkins, 1990; Horsley & Horsley-Loucks, 1998; McKibbin & Joyce, 1980). In this study, online training resources for implementing Banking Time were made available to preschool teachers for their voluntary use as a part of a large-scale professional development program. The primary purpose of this study was to examine teachers’ implementation of Banking Time, including characteristics of teachers and classrooms associated with Banking Time implementation, whether different levels of professional development support provided to teachers were associated with teachers’ implementation of Banking Time, and characteristics of children with whom teachers elected to implement Banking Time. In addition, associations were examined between children’s participation in Banking Time and changes in teachers’ perceptions of children’s social-emotional competencies and the quality of their relationships. The following section describes the important role that teacher–child relationships play in children’s development of social and academic competencies.

IMPORTANCE OF TEACHER–CHILD RELATIONSHIPS

The quality of relationships that children form with their teachers during the early school years has lasting consequences for children’s socioemotional and behavioral adaptation in school. Birch and Ladd (1997) found that observed teacher–child conflict was associated with children’s school avoidance, negative attitudes toward school, low self-directedness, and low cooperation in the classroom. Over time, relationships characterized by high levels of conflict were associated with a decline in children’s prosocial behavior as well as increases in peer-perceived aggressive behavior (Birch & Ladd, 1998). In addition, teacher reports of conflict with children are associated with increases in children’s problem behaviors and decreases in social competence over time (Pianta et al., 2005). Teacher–child closeness is another important dimension of the quality of the relationship that children form with their teachers, and studies have found that closer relationships are associated with greater levels of overall school adjustment (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Pianta et al., 2005).

In addition to the benefits of close, low-conflict teacher–child relationships on children’s social-emotional outcomes, research has found benefits of positive teacher–child relationships on academic outcomes. For example, Birch and Ladd (1997) found that children who had greater closeness with and less dependence on their kindergarten teachers gained more verbal and language skills during kindergarten. Similarly, Pianta and colleagues (2005) found that kindergarten students for whom academic failure or special education referral were expected, but who were not actually retained or referred, demonstrated more positive relationships with their kindergarten teachers than did students at similar levels of risk who were retained or referred. Palermo, Hanish, Martin, Fabes, and Reiser (2007) described the connection between teacher–child relationship quality and academic readiness and highlighted the need for teacher training, education, and support to facilitate close teacher–child relationships. In addition, positive relationships that children form with their teachers during the early school years have been found to be associated with long-term academic outcomes at the end of first grade and into the later school years (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Pianta & Nimetz, 1991). In another MyTeachingPartner (MTP) study, Mashburn, Downer, Hamre, Justice, and Pianta (2010) found that children whose teachers were randomly assigned to receive access to a teaching website and participate in teaching consultation made greater gains in receptive language skills during pre-kindergarten than children whose teachers were randomly assigned to receive access to the website only. Furthermore, among MTP teachers working with consultants, more hours of participating in the consultation process was positively associated with children’s receptive language development, and more hours implementing the language/literacy activities was positively associated with children’s language and literacy development.

There is some evidence to suggest that children feel that their relationships with teachers become less positive as they get older (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1997). In spite of the decline in these relationships as children advance in school, data from a large national survey indicate that even in adolescence, relationships with teachers are one of the single most important resources for children. They may operate as a protective factor against risk for a range of problem outcomes (Resnick et al., 1998) and are especially important for children from unsupportive home environments (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993). In sum, children’s development of close, low-conflict relationships with their teachers has lasting impacts on their social and academic success.

INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING POSITIVE SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT

A variety of school-based interventions have been developed with the aim of promoting children’s positive social adjustment in school (Joseph & Strain, 2003); however, few interventions focus specifically on building strong relationships between teachers and children. For example, Project Fast Track (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999a, 1999b) which starts with children as they enter school, has a specific focus on enhancing children’s social and emotional competencies and reducing negative, aggressive social behavior. A core component of the intervention is the classroom teacher’s use of the PATHS curriculum (Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies; Greenberg, Kusche, Cook, & Quamma, 1995). PATHS is designed to help children identify and label feelings and social interactions, reflect on those feelings and interactions, generate solutions and alternatives for interpretation and behavior, and test such alternatives. Evaluation of this intervention has indicated that PATHS can be effective in altering the quality of the classroom climate and relationships within the classroom (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999b). Specifically, findings indicated significant effects on peer ratings of aggression and hyperactive-disruptive behavior and observer ratings of classroom atmosphere. In a high-risk sample, there were moderate positive effects on children’s social, emotional, and academic skills; peer interactions; conduct problems; and special education referrals (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999a). Kam, Greenberg, and Walls (2003) concluded that the PATHS curriculum reduced aggression and improved young children’s emotional competence.

Dinosaur School (Webster-Stratton, 1990) is an Incredible Years Child Training Program that focuses on emotional literacy, perspective taking, friendship skills, anger management, interpersonal problem solving, school rules, and school success. The small-group intervention is designed for use with young children who exhibit conduct problems. Two randomized control group evaluations of Dinosaur School found significant increases in appropriate cognitive problem-solving strategies, prosocial conflict management strategies with peers, social competence, and appropriate play skills, in addition to decreased conduct problems at home and school (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997; Webster-Stratton & Reid, 1999). Findings have been replicated by independent investigators in randomized studies with diverse ethnic populations and age groups (August, Realmuto, Hektner, & Bloomquist, 2001; Barrera et al., 2002; Taylor, Schmidt, Pepler, & Hodgins, 1998).

TEACHER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Numerous studies have concluded that teachers’ interactions with children are the critical mechanisms in effective early childhood education programs (Downer, Kraft-Sayre, & Pianta, 2009; Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Howes et al., 2008; Mashburn et al., 2008; National Council on Teacher Quality, 2005; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2000). The success of early childhood education programs is influenced by the professional development of teachers in important instructional interaction skills (Zaslow & Martinez-Beck, 2005).

Traditional models of professional development, such as workshops, have been criticized for vague or irrelevant content, incongruence from the classroom context, and limited follow-up (Ball & Cohen, 1999; Borko, 2004; Sandholtz, 2002). In a survey of 1,000 nationally representative teachers, 79% reported involvement in traditional professional development workshops in comparison with 5% to 16% who reported active learning opportunities (Birman, Desimone, Porter, & Garet, 2000). Research on early childhood professional development often focuses on basic questions that address caregiver characteristics, such as credentials and experience, and their associations with aspects of knowledge, skill, and practice. Sheridan, Edwards, Marvin, and Knoche (2009) recently highlighted the need for changes in the way in which professional development research is conducted to include consideration of professional development processes, participant characteristics, relationships, and sustainability.

As research-based professional development programs are integrated into classroom settings, it is critical that evaluation studies identify contextual factors supporting implementation (Downer, Locasale-Crouch, Hamre, & Pianta, 2009; Mihalic, 2004; Penuel, Fishman, Yamaguchi, & Gallagher, 2007). The implementation of school-based interventions is affected by classroom contextual factors such as characteristics of teachers and their interactions with children (Dusenberry, Brannigan, Falco, & Hansen, 2003; Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger, 1999). Teachers who implement higher quality interventions have been found to be more enthusiastic (Gingiss, Gottlieb, & Brink, 1994; Parcel et al., 1995), to be more efficacious (Rohrbach, Graham, & Hansen, 1993; Sobol et al., 1989), to be less authoritarian (Rohrbach, Grana, Sussman, & Valente, 2006), to have solid teaching skills (Rohrbach et al., 2006), and to have fewer years of experience (Rohrbach et al., 1993).

In a recent study, Downer, Kraft-Sayre, and colleagues (2009) investigated implementation of the MTP Consultancy, a comprehensive classroom intervention composed of online video resources and Web-mediated consultation, to gain information about the facets of professional development that contributed to the success of the intervention. Significant effects were found for teacher age, teaching experience, beliefs about children, and self-efficacy. Teachers who reported higher levels of self-efficacy displayed increased use of the Consultancy and Web resources. The relationship between implementation and self-efficacy was further explored in the present study.

BANKING TIME

As described previously, a variety of school-based interventions target young children’s social-emotional competencies, and Banking Time (Pianta & Hamre, 2001) is another such intervention that makes a unique contribution by specifically targeting the quality of teacher–child relationships. Banking Time was adapted for use in schools from a direct intervention that was used with parents and children (i.e., Barkley, 1987). The approach is called Banking Time to emphasize that relationships serve as resources for children, and Banking Time enables teachers to invest in these resources during one-on-one sessions with students and to draw upon the capital invested by the teacher–child dyad to help solve behavioral problems or conflicts in the classroom. The principles of Banking Time are similar to those of teacher–child interaction therapy (McIntosh, Rizza, & Bliss, 2000), in which teachers engage in nondirective sessions with children designed to enhance the quality of teacher–child relationships. A case study found that teacher–child interaction therapy increased the number of positive interactions between the child and teacher and was effective in reducing the child’s disruptive behaviors (McIntosh et al., 2000).

Research on parent–child relationships demonstrates that parents of children with behavior problems are observed as controlling and dominating during play sessions (Greenberg, Kusche, & Speltz, 1991; Greenberg, Speltz, & Deklyen, 1993). One component of Barkley’s (1987) parent consultation program directs parents to spend up to 20 min daily interacting in nondirective, child-centered play sessions during which an activity is chosen by the child and occurs regardless of the child’s misbehavior. Parents are instructed not to teach, elicit information, ask questions, or direct the play; rather, they are to narrate, observe, and label the child’s play. The child-centered play time is viewed as a foundation upon which to build the parent–child relationship, which can facilitate the effectiveness of behavior management techniques by promoting increased value of the adult’s attention to the child, improved parent–child communication, and increased positive emotional experiences and motivation to change.

Banking Time sessions are a set of one-on-one meetings between a teacher and a child. The sessions are designed to enhance the quality of the teacher–child relationship by giving the dyad regular opportunities to interact positively with each other. The meetings are scheduled for a certain period of time, occur regularly, and take place at an agreed-upon location. Teachers are encouraged to implement Banking Time during available periods, such as recess, lunchtime, or naptime. During each Banking Time session a teacher and child participate together in an activity chosen by the child. The meeting is led by the child as the teacher watches, listens, and conveys acceptance and understanding. There are four components to the teacher role during a Banking Time session: (a) observing the child’s actions, (b) narrating the child’s actions, (c) labeling the child’s feelings and emotions, and (d) developing relational themes. While observing, teachers carefully watch and take note of students’ behavior, words, and feelings as well as their own thoughts and feelings. As narrators, teachers describe aloud what students are doing in an interested tone of voice; narration does not generally include teaching, directing, questioning, or reinforcement. While labeling children’s feelings and emotions, teachers communicate that they are able to read and understand children’s emotional states. Relational themes help convey supportive messages to children regarding their relationships with teachers. The themes provide words to go along with a child’s emotional experience during the Banking Time session. Examples of relational themes include “I am consistent” and “I will stick by you on difficult days.” In summary, Banking Time is a set of techniques designed to build positive, supportive relationships between teachers and children; the goal of the intervention is to build stronger relationships with students who may be having a difficult time in the classroom.

In a smaller study, Driscoll and Pianta (in press) evaluated the early efficacy of Banking Time in a sample of Head Start children. The study utilized random assignment and monitored intervention implementation and fidelity. Teachers participating in Banking Time consistently reported increased perceptions of closeness with children as well as increased frustration tolerance, task orientation, and competence and decreased conduct problems.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Resources for implementing Banking Time were made available to teachers who were participating in a large early childhood professional development project called MyTeachingPartner (MTP). MTP is a Web-based professional development program that provided various levels of support to teachers to implement classroom activities in a way that facilitated development of children’s language and literacy skills and positive social relationships (see Hadden & Pianta, 2006, for a description). The MTP website included a description of Banking Time and information about how to prepare for and implement Banking Time sessions in the classroom. As a part of this project, all teachers participating in the study had access to Web-based Banking Time training, and teachers’ implementation of Banking Time was completely voluntary.

The purpose of the present study was to examine teachers’ implementation of Banking Time, including characteristics of students, teachers, and classrooms associated with Banking Time implementation; whether different levels of professional development support provided to teachers were associated with their implementation of Banking Time (Research Question 1); and characteristics of children with whom teachers elected to implement Banking Time (Research Question 2). In addition, we examined the extent to which teachers’ implementation of Banking Time was associated with changes in teachers’ perceptions of children’s social behavior and the teacher–child relationship (Research Question 3).

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 252 preschool teachers who participated in MTP, a Web-based professional development intervention for early childhood teachers in preschool classrooms. MTP was implemented within a statewide sample of classrooms participating in the Virginia Preschool Initiative, the state-funded preschool program that serves 4-year-old children who experience social and/or economic risks. Specifically, children were eligible for enrollment in this program based on the following criteria: (a) poverty; (b) homelessness; (c) parents or guardians were school dropouts, had limited education, or were chronically ill; (d) family stress as evidenced by poverty, episodes of violence, crime, underemployment, unemployment, homelessness, incarceration, or family instability; (e) child or developmental problems; or (f) limited English proficiency.

Within each participating classroom, approximately four children were randomly selected to participate in an evaluation of the effects of different components of the intervention on children’s development of language, literacy, and social-emotional competencies. A total of 1,064 children who had valid data on measures (described in “Measures”) were included in this study. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 1,064 children in this study, and Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the 252 teachers and the characteristics of their classrooms.

TABLE 1.

Child Characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study condition (N = 1,064) | ||||

| Consultancy | 372 | 35.0 | ||

| Web access | 278 | 26.1 | ||

| Control | 414 | 38.9 | ||

| Gender (N = 1,037) | ||||

| Male | 510 | 49.2 | ||

| Female | 527 | 50.8 | ||

| Race (N = 1,039) | ||||

| African American | 479 | 46.1 | ||

| Latino | 120 | 11.6 | ||

| Other race | 133 | 12.7 | ||

| White | 307 | 29.6 | ||

| Maternal education (years) | 1,031 | 12.73 | 2.01 | |

| Language and literacy skills (PK fall) | 879 | 2.07 | 0.76 | |

| Language and literacy skills (PK spring) | 840 | 3.27 | 0.94 | |

| Problem behaviors (PK fall) | 874 | 1.53 | 0.57 | |

| Problem behaviors (PK spring) | 840 | 1.51 | 0.55 | |

| Social competence (PK fall) | 878 | 3.20 | 0.77 | |

| Social competence (PK spring) | 840 | 3.52 | 0.79 | |

| Conflict (PK fall) | 879 | 1.69 | 0.81 | |

| Conflict (PK spring) | 840 | 1.76 | 0.84 | |

| Closeness (PK fall) | 879 | 4.27 | 0.69 | |

| Closeness (PK spring) | 840 | 4.48 | 0.58 | |

| Participated in Banking Time (N = 839) | ||||

| Yes | 200 | 23.8 | ||

| No | 639 | 76.2 |

Note. PK = pre-kindergarten.

TABLE 2.

Classroom and Teacher Characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom characteristics | ||||

| Limited English proficient (%) | 239 | 12.89 | 25.71 | |

| Individualized education plan (%) | 238 | 7.83 | 13.68 | |

| No. of children enrolled | 238 | 14.74 | 2.13 | |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | 245 | 1.37 | 0.57 | |

| Teacher characteristics | ||||

| Study condition (N = 252) | ||||

| Consultancy | 90 | 35.7 | ||

| Web access | 96 | 38.1 | ||

| Control | 66 | 26.2 | ||

| Mean visits to BT website (time) | 252 | 2.15 | 8.28 | |

| Child-centered beliefs | 238 | 2.33 | 0.60 | |

| Self-efficacy | 235 | 4.39 | 0.48 | |

| Advanced degree (N = 238) | 83 | 34.9 | ||

| Field (N = 237) | ||||

| Early childhood education | 91 | 38.4 | ||

| Elementary education | 62 | 26.2 | ||

| Other field | 84 | 36.4 | ||

| Years of experience | 236 | 14.52 | 9.25 | |

| No. of study children per class | 245 | 4.34 | 0.75 | |

| Study children participating in BT per class (%) | 203 | 8.2 | 21.5 |

Note. BT = Banking Time.

Measures

Study Participation

Study condition.

Teachers participated in one of three study conditions as a part of the MTP professional development intervention study. In the Consultancy condition, teachers received materials (books, activities) to implement activities that promoted students’ language/literacy and social-emotional development; access to the MTP website, which described and demonstrated dimensions of high-quality teaching and provided resources (including a description of Banking Time) to teachers to promote high-quality teaching in their classrooms; and access to a teaching consultant with whom teachers discussed their teaching practices every 2 weeks. Teachers in the Web Access condition received the materials to implement language/literacy and social-emotional activities and access to the MTP website. Teachers in the Control condition received the materials to implement language/literacy and social-emotional activities and access to a limited portion of the MTP website that included resources for implementing Banking Time.

Visits to the banking time website.

Teachers’ use of the Web-based resources was documented using the MTP Web server, which automatically recorded the duration of each teacher’s visits to each Web page on the MTP website. The effect of the amount of time spent on Banking Time pages (minutes on MTP BT website) on whether Banking Time was implemented was examined.

Implementation of banking time.

At the end of the school year, teachers indicated (yes/no) whether they had conducted at least one Banking Time session with each of the four selected children in their class. These responses were also aggregated to provide a measure of the percentage of children in each class with whom teachers implemented Banking Time.

Teacher Characteristics

At the beginning of the school year, teachers completed a questionnaire that measured the following demographic characteristics: whether the teacher had attained an advanced degree, the teacher’s field of study, and the number of years of teaching experience. Teachers also completed measures of self-efficacy and ideas about children described here.

Self-efficacy.

An abbreviated 7-item version of the Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale (Bandura, 1997) was included to assess teachers’ sense of efficacy regarding management and motivation of children in their classrooms. The response scale ranged from nothing to a great deal, and items included questions such as “How much can you do to get through to the most difficult students?” and “How much can you do to keep students on task on difficult assignments?” The internal consistency (alpha) for these seven items from this study was .86.

Ideas about children.

Teachers’ adult-centered beliefs about children were measured using the Modernity Scale (Schaefer & Edgerton, 1985). a 16-item Likert-type questionnaire that assesses teachers’ ideas about educating children along a continuum ranging from “traditional” or relatively adult-centered perspectives on interactions with children to more “modern or progressive” child-centered perspectives. Teachers with a more adult-centered view agreed with statements such as “Children must be carefully trained early in life or their natural impulses make them unmanageable,” and teachers with more child-centered beliefs agreed with statements such as “Children should be allowed to disagree with their parents if they feel their own ideas are better.” Scores are derived by computing the mean of all items, with child-centered beliefs reverse-scored. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was reported as .84 by the scale’s authors and was .80 in the present sample.

Classroom Characteristics

The questionnaire completed by teachers at the beginning of the school year also measured the following classroom characteristics: the percentage of children who had limited English proficiency, the percentage of children who had Individualized Education Plans, and the number of children enrolled. The average economic background of children within each class was computed using information collected from family demographic surveys completed by a parent or guardian of the majority of children in each class. The income-to-needs ratio is a measure of family poverty that uses the federal criteria for poverty, which is based on the total household income and the number of adults and children within the household. The mean income-to-needs ratio of children in each class served as the classroom-level measure of family poverty.

Child Characteristics

A family member of each participating child completed a family demographic questionnaire that provided information about the demographic characteristics of the child and his or her family. This survey included the following items that were included in this study: the child’s gender, race/ethnicity, and the number of years of maternal education.

Child language/literacy skills.

At the beginning of the school year, teachers reported on the child’s language and literacy skills using the Academic Rating Scale (National Center for Education Statistics, 1999). This scale measures kindergarten teachers’ perceptions of children’s language and literacy skills, including speaking, listening, and early reading and writing. Ratings are made along a scale that ranges from 1 to 5 and that is anchored by the following descriptors: 1 = not yet, 2 = beginning, 3 = in progress, 4 = intermediate, and 5 = proficient. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the Language and Literacy scale in this sample was .93.

Child social-emotional competence.

At the beginning and end of the school year, teachers assessed children’s social-emotional competencies using two measures, the Teacher–Child Rating Scale (Hightower et al., 1986) and the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta, 2001). The Teacher–Child Rating Scale (Hightower et al., 1986) is a behavioral rating scale that assesses two dimensions of children’s social and emotional competencies—problem behaviors and social competence. On the problem behaviors subscale, teachers are asked to describe how well different problematic behaviors describe a particular child, and ratings are made along a 1-to-5 response scale that is anchored by 1 = not a problem, 2 = mild problem, 3 = moderate problem, 4 = serious problem, and 5 = very serious problem. On the social competence subscale, teachers are asked to describe how well different prosocial behaviors describe a particular child, and ratings are made along a 1-to-5 response scale that is anchored by 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately well, 4 = well, and 5 = very well. The problem behaviors scale comprises three dimensions—conduct problems, internalizing problems, and learning problems—and items include “disruptive in class,” “anxious,” and “difficulty following directions.” The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for this subscale was .94 and .95 at the beginning and end of the year, respectively. The social competence scale comprises four dimensions—frustration tolerance, assertiveness, task orientation, and peer social skills—and items include “participates in class discussions,” “completes work,” and “well-liked by classmates.” The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for this subscale was .92 and .90 at the beginning and end of the year, respectively.

The Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta, 2001) provides measures of conflict and closeness between a child and a teacher, and scores range from 1 to 5 (1 = definitely does not apply; 2 = not really; 3 = neutral, not sure; 4 = applies somewhat; and 5 = definitely applies). Examples of closeness items include “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child” and “The child values his/her relationship with me.” Examples of conflict items include “The child and I always seem to be struggling with each other” and “The child easily becomes angry at me.” The closeness scale is the mean of seven items and achieved Cronbach’s alphas of .86 and .84 for fall and spring, respectively. The conflict scale is the mean of eight items and achieved Cronbach’s alphas of .89 and .87 for fall and spring, respectively.

The four subscales derived from the Teacher–Child Rating Scale and Student–Teacher Relationship Scale were used separately as child outcomes in the analysis that examined the associations between children’s participation in Banking Time and changes in their social-emotional competencies during preschool (Research Question 3). In addition, in the analysis that examined the characteristics of children with whom teachers chose to implement Banking Time (Research Question 2), each measure of children’s social-emotional competencies at entry into preschool was included as a predictor to examine its unique association with Banking Time participation.

Analysis

Logistic regression, multilevel logistic regression, and multilevel regression analysis were used to examine each of the three research questions, respectively. To address the first research question examining characteristics associated with teachers’ implementation of Banking Time, we predicted whether or not a teacher implemented Banking Time with a student or multiple students in a class (yes = 1, no = 0) by three blocks of predictors via a logistic regression model: study participation (study condition and minutes on MTP BT website), classroom characteristics (percentage of children in each class classified as limited English proficient, percentage of children in each class classified with an individualized education plan, the number of children enrolled in each class, and the mean family income-to-needs ratio in each class), and teacher characteristics (child-centered beliefs, self-efficacy, advanced degree, field of study, and years of experience). The second research question predicted each child’s participation in Banking Time. Because several children were nested within the same teacher, a multilevel logistic model was used to examine the associations between Banking Time participation (yes = 1, no = 0) and the following predictors: study condition, gender, race, maternal education, language and literacy skills, and social competence. The final analysis used multilevel regression models to examine associations between children’s participation in Banking Time (yes = 1, no = 0) and their development of social competencies during preschool. Each of the four measures of spring social-emotional competence was predicted by the following predictors: the corresponding fall measure of social-emotional competence, child characteristics, classroom characteristics, teacher characteristics, study condition, minutes on MTP BT website, and whether the child participated in Banking Time. The logistic regression model, multilevel logistic model, and multilevel regression models were implemented in SAS using the following commands: PROC LOGISTIC, PROC NLMIXED, and PROC MIXED.

Attrition analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of missing data. t tests or chi-square tests were carried out to compare the frequencies or means of two groups (complete data group vs. missing data group) on all output variables. None of the tests indicated statistically significant differences between the two groups in frequencies or means (closeness: t = 1.76, p = .08; competence: t = 0.28, p = .78; conflict: t = −0.59, p = .55; problem behavior: t = −0.42, p = .67; Banking Time: χ2 = 0.93, p = .33). A missing-at-random mechanism was assumed for all data analyses.

RESULTS

Characteristics Associated With Teachers’ Use of Banking Time

Table 3 presents results of the logistic regression analysis that examined study, classroom, and teacher characteristics associated with whether or not a teacher implemented Banking Time in a class (yes/no). The regression coefficient, partial odds ratio, and confidence interval for the partial odds ratio (eB) are given for each predictor. The partial odds ratio is the exponentiation of the regression coefficient and is computed as the natural base log raised to the power of the regression coefficient, which may be interpreted as an odds ratio that controls for other variables in the equation. The first block of predictors included measures of teachers’ level of participation in the MTP professional development study. Teachers who participated in the Consultancy condition were more likely to implement Banking Time with their students compared to teachers who participated in the Control condition. Specifically, the odds of implementing Banking Time for teachers who participated in the Consultancy condition were 4.66 times as high as the odds for teachers who participated in the Control condition.

TABLE 3.

Teacher and Classroom Characteristics Associated With Whether Banking Time Was Implemented

| 95% Confidence Interval |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | B | SE | exp(B) | Lower | Upper |

| Study characteristic (203 teachers) | |||||

| Consultancy/Control | 1.54** | 0.53 | 4.66 | 1.64 | 13.27 |

| Web Access/Control | 0.43 | 0.56 | 1.54 | 0.51 | 4.66 |

| Minutes on MTP BT website | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.06 |

| Classroom characteristic (201 teachers) | |||||

| Limited English proficient (%) | −0.35 | 1.32 | 1.20 | 0.36 | 4.06 |

| Individualized education plan (%) | 0.18 | 0.62 | 1.70 | 0.12 | 24.10 |

| No. of children enrolled | 0.53 | 1.35 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.10 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | −0.07 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.58 | 2.08 |

| Teacher characteristic (196 teachers) | |||||

| Child-centered beliefs | −0.03 | 0.36 | 0.974 | 0.48 | 1.974 |

| Self-efficacy | −0.03 | 0.29 | 0.971 | 0.547 | 1.723 |

| Advanced degree | 0.18 | 0.37 | 1.194 | 0.579 | 2.463 |

| Elem Ed (1)/ECE | 0.61 | 0.47 | 1.845 | 0.738 | 4.612 |

| Other field (1)/ECE | 0.96** | 0.42 | 2.599 | 1.141 | 5.918 |

| Years of experience | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.993 | 0.956 | 1.03 |

Note. The 95% confidence intervals are based on partial odds ratios. exp(B) = partial odds ratio; MTP = MyTeachingPartner; BT = Banking Time; Elem Ed = elementary education; ECE = early childhood education.

p ≤ .01.

A second block of predictors included classroom characteristics, and none of the characteristics were associated with teachers’ use of Banking Time. A third block of predictors included characteristics of teachers. Teachers who had education in another field besides early childhood education or elementary education were more likely to implement Banking Time with students than teachers who had education in early child education. Other teacher characteristics were not associated with teachers’ use of Banking Time.

Predictors of Children’s Participation in Banking Time

Table 4 presents results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis that predicted whether each child participated in Banking Time (yes/no). The regression coefficient, partial odds ratio, and confidence interval for the partial odds ratio (eB) are given for each predictor. Results indicate that study condition was significantly associated with whether children participated in Banking Time. Specifically, the odds of participating in Banking Time for children whose teachers participated in the Consultancy condition were 16.2 times as high as the odds for children whose teachers who participated in the Control condition, and the odds of participating in Banking Time for children whose teachers participated in the Web Access condition were 13.3 times as high as the odds for children whose teachers participated in the Control condition. In addition, children who began preschool with more problem behaviors were more likely to participate in Banking Time than children who entered preschool with fewer problem behaviors. Children with lower maternal education were more likely to participate in Banking Time than children with higher maternal education. Gender and race were not associated with children’s participation in Banking Time.

TABLE 4.

Child Characteristics Associated With Children’s Participation in Banking Time (N = 679)

| 95% Confidence Interval |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | B | SE | exp(B) | Lower | Upper |

| Study condition | |||||

| Consultancy (1)/Control (0) | 2.79** | 0.48 | 16.23 | 6.28 | 41.96 |

| Web Access (1)/Control (0) | 2.59** | 0.49 | 13.29 | 5.10 | 34.63 |

| Boy | −0.07 | 0.20 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 1.39 |

| Race | |||||

| African American (1)/White (0) | 0.10 | 0.24 | 1.11 | 0.69 | 1.78 |

| Latino (1)/White (0) | −0.61 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.26 | 1.15 |

| Other race (1)/White (0) | 0.37 | 0.31 | 1.45 | 0.78 | 2.69 |

| Maternal education (years) | −0.11** | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.99 |

| Language and literacy skills | 0.15 | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.86 | 1.59 |

| Social competence | −0.05 | 0.21 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 1.43 |

| Problem behavior | 0.57** | 0.26 | 1.76 | 1.07 | 2.92 |

| Closeness | −0.08 | 0.15 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 1.24 |

| Conflict | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 0.86 | 1.58 |

Note. The 95% confidence intervals are based on partial odds ratios. exp(B) = partial odds ratio.

p ≤ .01.

Banking Time and Children’s Development of Social-Emotional Competencies

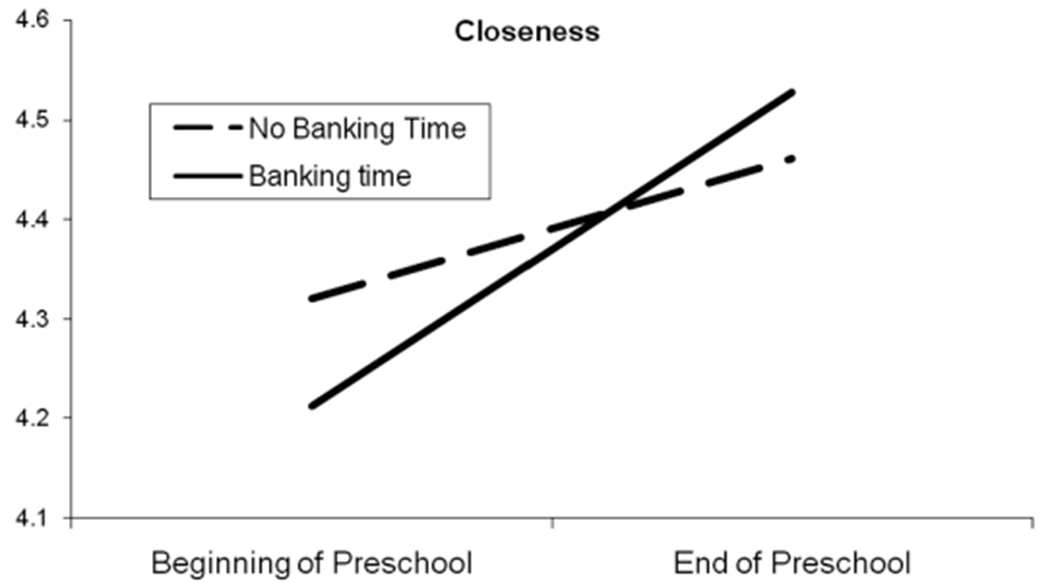

Table 5 presents results of multilevel modeling analyses predicting four measures of children’s social-emotional competence in spring (teacher–child closeness and conflict, social competence, problem behaviors) with corresponding fall measures of social-emotional competence, child and family characteristics, classroom characteristics, teacher characteristics, study condition, minutes on MTP BT website, and children’s participation in Banking Time. Table 6 displays results of final models with only significant covariates included. The intraclass correlation values were .25, .10, .20, and .17 for teacher–child closeness, conflict, social competence, and problem behaviors, respectively. Pretest scores were positively associated with each of the four posttest measures of social-emotional competence. In addition, boys had higher levels of problem behaviors and lower levels of social competence than girls. African American children had higher levels of problem behaviors than White children. Children in classes with a higher percentage of students with limited English proficiency had greater teacher–child conflict problems than children enrolled in classes with fewer students identified as having limited English proficiency. Children whose teachers used more MTP Banking Time online resources had higher levels of closeness and social competence and lower levels of problem behaviors than children whose teachers used fewer resources. Whether the child participated in Banking Time was strongly associated with teacher–child closeness at the end of preschool, after teacher–child closeness at the beginning of preschool and child, teacher, and classroom characteristics were accounted for. Children’s Banking Time participation was also associated with increased social competence but was not statistically significant after we controlled the included covariates. Interindividual differences in the effects of children’s Banking Time participation on social competence were significant. Effect sizes of change scores (spring–fall) comparing children who participated Banking Time and those who did not are also reported in Table 6. Figure 1 depicts the association between participation in Banking Time and the development of teacher–child closeness from fall to spring of preschool.

TABLE 5.

Child, Classroom, and Teacher Characteristics Associated With Children’s Gains in Social-Emotional Competencies During Preschool

| Closeness |

Conflict |

Social Competence |

Problem Behaviors |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Child characteristic | ||||||||||||

| Score—PK fall | 0.47** | 0.03 | .00 | 0.68** | 0.04 | .00 | 0.66** | 0.03 | .00 | 0.68** | 0.05 | .00 |

| Boy | −0.05 | 0.04 | .14 | 0.07 | 0.05 | .16 | −0.09* | 0.04 | .03 | 0.08** | 0.03 | .01 |

| AA (1)/White (0) | −0.08 | 0.04 | .06 | 0.10 | 0.07 | .13 | −0.06 | 0.06 | .28 | 0.08* | 0.04 | .03 |

| Latino (1)/White (0) | 0.00 | 0.08 | .96 | −0.11 | 0.11 | .31 | 0.14 | 0.10 | .17 | −0.09 | 0.06 | .16 |

| Other race (1)/White (0) | −0.03 | 0.06 | .58 | −0.14 | 0.08 | .08 | 0.10 | 0.07 | .18 | −0.05 | 0.05 | .28 |

| Maternal education (years) | 0.02 | 0.01 | .09 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .83 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .35 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .29 |

| Classroom characteristic | ||||||||||||

| LEP (%) | 0.04 | 0.09 | .64 | 0.36** | 0.14 | .01 | −0.08 | 0.13 | .57 | 0.12 | 0.08 | .15 |

| IEP (%) | 0.23 | 0.14 | .12 | −0.34 | 0.24 | .15 | 0.21 | 0.23 | .35 | 0.00 | 0.11 | .97 |

| No. of children enrolled | 0.01 | 0.01 | .11 | −0.02 | 0.01 | .31 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .23 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .56 |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | 0.00 | 0.02 | .91 | −0.02 | 0.03 | .58 | 0.03 | 0.03 | .31 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .27 |

| Teacher characteristic | ||||||||||||

| Child-centered beliefs | 0.05 | 0.04 | .17 | −0.08 | 0.06 | .18 | 0.10 | 0.06 | .08 | −0.01 | 0.03 | .82 |

| Self-efficacy | −0.04 | 0.03 | .24 | −0.04 | 0.05 | .51 | −0.06 | 0.05 | .23 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .76 |

| Advanced degree | 0.06 | 0.04 | .12 | −0.03 | 0.06 | .59 | 0.08 | 0.06 | .18 | −0.04 | 0.04 | .22 |

| Elem Ed (1)/ECE (0) | −0.01 | 0.04 | .80 | −0.04 | 0.07 | .61 | −0.08 | 0.07 | .25 | 0.03 | 0.04 | .43 |

| Other field (1)/ECE (0) | −0.05 | 0.04 | .18 | −0.04 | 0.07 | .57 | −0.04 | 0.06 | .53 | 0.00 | 0.04 | .97 |

| Consultancy (1)/Control (0) | 0.04 | 0.05 | .39 | −0.15 | 0.08 | .08 | 0.13 | 0.08 | .09 | −0.07 | 0.05 | .14 |

| Web Access (1)/Control (0) | 0.09 | 0.05 | .09 | −0.08 | 0.08 | .33 | 0.17* | 0.08 | .03 | −0.03 | 0.05 | .53 |

| Minutes on MTP BT website | .004** | .001 | .01 | −.002 | .002 | .44 | 0.01** | .002 | .00 | −.002 | .001 | .13 |

| BT | 0.09* | 0.04 | .04 | 0.11 | 0.07 | .11 | 0.01 | 0.07 | .93 | 0.04 | 0.05 | .40 |

Note. All covariates are included in the models. PK = pre-kindergarten; AA = African American; LEP = limited English proficiency; IEP = individualized education plan; Elem Ed = elementary education; ECE = early childhood education; MTP = MyTeachingPartner; BT = Banking Time.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

TABLE 6.

Child, Classroom, and Teacher Characteristics Associated With Children’s Gains in Social-Emotional Competencies During Preschool

| Closeness |

Conflict |

Social Competence |

Problem Behaviors |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 2.41** | 0.15 | .00 | 0.58** | 0.06 | .00 | 1.33** | 0.10 | .00 | 0.41** | 0.05 | .00 |

| Score—PK fall | 0.48** | 0.03 | .00 | 0.66** | 0.03 | .00 | 0.69** | 0.03 | .00 | 0.67** | 0.04 | .00 |

| Boy | −0.09* | 0.04 | .02 | 0.07** | 0.03 | .01 | ||||||

| AA (1)/White (0) | 0.10* | 0.03 | .00 | |||||||||

| LEP (%) | 0.26** | 0.10 | .01 | |||||||||

| Minutes on MTP BT website | 0.004* | 0.002 | .03 | 0.009** | 0.003 | .00 | −0.003* | 0.001 | .05 | |||

| BT (yes/no) | 0.08* | 0.04 | .04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | .51 | 0.05 | 0.06 | .42 | −0.01 | 0.04 | .82 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| VAR (intercept) | 1.05** | 0.32 | .00 | 0.05** | 0.01 | .00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | .14 | |||

| VAR (score—PK fall) | −0.20** | 0.07 | .00 | 0.01** | 0.00 | .00 | 0.09** | ** 0.03 | .00 | |||

| COV (intercept, score—PK fall) | 0.04** | 0.01 | .01 | |||||||||

| VAR (BT) | 0.11* | 0.07 | .05 | |||||||||

| COV (intercept, BT) | −0.02 | 0.03 | .39 | −0.07* | 0.03 | .03 | ||||||

| Level 1 residual variance | 0.17** | 0.01 | .00 | 0.33* | 0.02 | .00 | 0.23** | 0.02 | .00 | 0.11** | 0.01 | .00 |

| Effect sizes of change scores (Spring–Fall) | ||||||||||||

| BT: Yes | M=0.35, SD=0.71 | M=−0.04, SD=0.79 | M=0.47, SD=0.63 | M=−0.09, SD=0.50 | ||||||||

| BT: No | M=0.15, SD=0.56 | M=0.07, SD=0.64 | M=0.28, SD=0.57 | M=0.01, SD=0.42 | ||||||||

| Effect size | .33 | −0.17 | .32 | −0.23 | ||||||||

Note. Only significant covariates are included in the final models. PK = pre-kindergarten; AA = African American; LEP = limited English proficiency; MTP = MyTeachingPartner; BT = Banking Time; VAR = variant; COV = covariant.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

FIGURE 1.

Closeness at the beginning and end of preschool for children who did and did not participate in Banking Time.

DISCUSSION

Children’s development of close, low-conflict relationships with their teachers has important consequences for building social and academic skills, particularly during the early school years (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Pianta et al., 2005). Banking Time is a set of techniques designed to promote positive, supportive relationships between teachers and children through regular, one-on-one interactions that focus on attending and responding to the child’s interests and behaviors during activities the student chooses. As a part of MTP, a Web-based professional development intervention for preschool teachers, instructions for implementing Banking Time were made available to teachers for voluntary implementation. This study identified factors associated with teachers’ implementation of Banking Time, characteristics of children with whom teachers chose to implement Banking Time, and associations between Banking Time participation and children’s social-emotional competencies and teacher–child relationships, which have implications for fostering supportive teacher–child relationships.

Additional Supports for Implementing Banking Time

The results of this study indicate that implementation of Banking Time was influenced by the additional supports teachers received as a part of the intervention study. Specifically, teachers who were provided access to the Banking Time resources on the MTP website but who were not provided additional resources to promote its implementation were less likely to implement Banking Time with children in their classes. This is compared to teachers who received access to the full range of Web-based resources on the MTP website (including descriptions of high-quality teaching and video demonstrations of activities that promote student development), who were more than 13 times more likely to implement Banking Time with students. Teachers who worked with a consultant were also more likely to implement Banking Time with children. This may be the result of the consultants’ direct efforts to encourage teachers to utilize this technique with children who were experiencing social-emotional problems or conflict with teachers.

Banking Time and Child Outcomes

The results indicate that children who participated in Banking Time developed closer relationships with their teachers over the course of the school year than children who did not participate in Banking Time. It is important to note that the impact of Banking Time manifested only in teacher–child closeness; changes in conflict between teachers and children were not influenced by participation in Banking Time. Results of several studies conclude that teacher reports of relational conflict are difficult to discriminate from their reports of child conduct problems (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Hughes, Cavell, & Jackson, 1999; Hughes, Cavell, & Wilson, 2001; Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2005). Silver and colleagues (2005) suggested that teacher reports of conflict in the teacher–child relationship may reflect child-driven effects on teachers’ perceptions of relationships, whereas teachers’ reports of closeness may more accurately represent teachers’ abilities to foster trust and warmth with children. In a 5-year longitudinal study, Howes (2000) reported stable levels of conflict over time. In addition, the effects of Banking Time on changes in teacher–child relationships were small in magnitude—children who participated gained more than 0.3 points in closeness during preschool on the 1-to-5 rating scale compared to 0.15 points gained by children who did not participate. However, the sample of children teachers selected to participate in Banking Time began preschool with lower closeness than their peers and may be more at risk for problems in their subsequent adaptation to the social and academic demands of school. Thus, this improved relationship with teachers early in school may influence children’s trajectory for positive development and have lasting effects on children’s social and academic development (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Pianta et al., 2005).

In sum, the findings suggest that Banking Time has the potential to be an effective tool for building close relationships between teachers and children during preschool. The proposed mechanism for the Banking Time intervention involves decreasing classroom difficulties by improving the teacher–child relationship via regular one-on-one child-directed play sessions. Teachers who implemented Banking Time chose to target use toward children who had the greatest need; however, many teachers chose not to implement Banking Time at all. Decisions to use Banking Time were most strongly associated with whether teachers received additional supports as a part of the MTP professional development program; thus, efforts to promote implementation of Banking Time should be accompanied by additional resources for teachers, such as a teaching consultant, which may encourage proper and effective use Banking Time to promote close relationships with children.

The present findings are consistent with another analysis of the Banking Time intervention. Driscoll and Pianta (in press) evaluated the early efficacy of Banking Time in a sample of 120 Head Start children in 30 classrooms. The study utilized random assignment and monitored intervention implementation and fidelity. Teachers participating in Banking Time consistently reported increased perceptions of closeness with children as well as increased frustration tolerance, task orientation, and competence and decreased conduct problems.

The prevention science literature provides a context for interpreting results related to the three research questions in the present study. A report on prevention research (Greenberg et al., 2000) urged researchers to develop knowledge of the program dissemination process. In 1997, less than 5% of more than 1,200 previously published prevention studies reported data on program implementation (Durlak, 1997). Only 14.9% of school-based interventions systematically measured and reported levels of treatment integrity (Gresham, Gansle, Noell, & Cohen, 1993). A study of 34 effective intervention programs concluded that only 21% examined the relationship between quality of implementation and outcomes (Domitrovich & Greenberg, 2000). Greenberg and colleagues (2000) highlighted the importance of studying various components of the implementation process, including dosage, quality of delivery, and quality of institutional leadership and support. The majority of implementation studies examine single facets of implementation and do not explore the interrelationship among multiple aspects of intervention implementation. Several studies cite proximal, unmeasured factors that may contribute to teacher implementation quality, including teacher personality, self-efficacy, attitudes toward change (Hopkins, 1990; McKibbin & Joyce, 1980), and experience with and adaptation to curriculum innovation (Hall & Hord, 1987; Horsley & Horsley-Loucks, 1998).

Limitations

This study is not intended as a comprehensive explanation of outcomes associated with Banking Time implementation. Rather, it is meant to serve as an investigation of teacher, child, and classroom characteristics associated with the use of Banking Time, as well as the extent to which teachers’ use of Banking Time is associated with changes in teachers’ perceptions of children’s social behavior and the teacher–child relationship. Please note that this study did not analyze language and literacy outcomes associated with Banking Time. Please refer to a separate study by Mashburn and colleagues (2010) for further discussion of language and literacy outcomes related to the MTP intervention.

An important limitation is the absence of additional reporters. The same teacher was asked to report on the teacher–child relationship and child behavior at the beginning and end of the school year. The use of additional reporters, such as teaching assistants or trained observers, would allow for greater confidence in the accuracy of child ratings.

Another limitation is that implementation fidelity was not measured. It is unclear whether teachers who implemented Banking Time with greater frequency or with higher quality demonstrated increased positive child outcomes. Furthermore, this study relied on teacher report to determine whether teachers used Banking Time. Future studies should consider and address these limitations.

Conclusion

The present study seeks to contribute to the knowledge base on teachers’ implementation of classroom interventions. The results of the present study provide preliminary support for increased teacher perceptions of closeness associated with the use of Banking Time. The study also provides valuable information about teachers’ use of classroom interventions. Findings should be used to inform future study of this classroom intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted by the MyTeachingPartner Research Group supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Interagency Consortium on School Readiness. We extend our deep appreciation to the cadre of teachers who worked with us throughout this period and who allowed us to experiment with new ways of supporting them.

Contributor Information

Katherine C. Driscoll, Division of Developmental Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School

Lijuan Wang, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame.

Andrew J. Mashburn, Center for the Advanced Study of Teaching and Learning, University of Virginia

Robert C. Pianta, Center for the Advanced Study of Teaching and Learning, University of Virginia

REFERENCES

- August GJ, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM, & Bloomquist ML (2001). An integrated components preventive intervention for aggressive elementary school children: The early risers program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 614–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball DL, & Cohen DK (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In Darling-Hammond L, & Sykes G (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice, (pp. 3–32). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Macmilan. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R (1987). Defiant children: A clinician’s manual for parent training. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Biglan A, Taylor TK, Gunn B, Smolkowski K, Black C, & Fowler RC (2002). Early elementary school intervention to reduce conduct problems: A randomized trial with Hispanic and non-Hispanic children. Prevention Science, 3, 83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, & Ladd GW (1997). The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, & Ladd GW (1998). Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher-child relationship. Developmental Psychology, 34, 934–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman BF, Desimone L, Porter AC, & Garet MS (2000). Designing professional development that works. Educational Leadership, 57(8), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Borko H (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Lynch M (1993). Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 56, 96–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1999a). Initial impact of the fast track prevention trial for conduct problems: I. The high-risk sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 631–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1999b). Initial impact of the fast track prevention trial for conduct problems: II. Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 648–657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, & Greenberg MT (2000). The study of implementation: Current findings from effective programs that prevent mental disorders in school-aged children. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 11, 193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Kraft-Sayre ME, & Pianta RC (2009). Ongoing, web-mediated professional development focused on teacher-child interactions: Early childhood educators’ usage rates and self-reported satisfaction. Early Education & Development, 20, 321–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Locasale-Crouch J, Hamre B, & Pianta R (2009). Teacher characteristics associated with responsiveness and exposure to consultation and online professional development resources. Early Education & Development, 20, 431–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll K, & Pianta RC (2010). Banking Time in Head Start: Early efficacy of an intervention designed to promote supportive teacher-child relationships. Early Education & Development, 21, 38–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA (1997). Successful prevention programs for children and adolescents. New York, NY: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Dusenberry L, Brannigan R, Falco M, & Hansen WB (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse in school settings. Health Education Research, 18, 237–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, & Hayduk LA (1988). Lasting effects of elementary school. Sociology of Education, 61, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gingiss PL, Gottlieb NH, & Brink SG (1994). Increasing teacher receptivity toward use of tobacco prevention education programs. Journal of Drug Education, 24, 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Domitrovich C, & Bumbarger B (1999). Preventing mental disorder in school-age children: A review of the effectiveness of prevention programs. Retrieved from www.psu.edu/dept/prevention

- Greenberg MT, Domitrovich C, Graczyk PA, & Zins JE (2000). The study of implementation in school-based prevention research: Theory, research, and practice. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services (SAMHSA). [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M, Kusche C, Cook E, & Quamma J (1995). Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: The effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Kusche CA, & Speltz M (1991). Emotional regulation, self-control, and psychopathology: The role of relationships in early childhood. In Cicchetti D, & Toth S (Eds.), Rochester symposium on developmental psychology, (pp. 21–55). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, & Deklyen M (1993). The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Gansle KA, Noell GH, & Cohen S (1993). Treatment integrity of school-based behavioral intervention studies: 1980–1990. School Psychology Review, 22, 254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hadden S, & Pianta R (2006). MyTeachingPartner: An innovative model of professional development. Young Children, 61(2), 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GE, & Hord SM (1987). Change in schools: Facilitating the process. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, & Pianta RC (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72, 625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, & Pianta RC (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76, 949–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower AD, Work WC, Cowen EL, Lotyczewski BS, Spinell AP, Guare JC, & Rohrbeck CA (1986). The Teacher-Child Rating Scale: A brief objective measure of elementary children’s school problem behaviors and competencies. School Psychology Review, 15, 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D (1990). Integrating staff development and school improvement: A study of teacher personality and school climate. In Joyce B (Ed.), Changing school culture through staff development (pp. 41–67). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [Google Scholar]

- Horsley DL, & Horsley-Loucks S (1998). CBAM brings order to the tornado of change. Journal of Staff Development, 19, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C (2000). Social-emotional classroom climate in child care, child-teacher relationships and children’s second grade peer relations. Social Development, 38, 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Burchinal M, Pianta R, Bryant D, Early D, Clifford R, & Barbarin O (2008). Ready to learn? Children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, & Jackson T (1999). Influence of student-teacher relationship on childhood aggression: A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28, 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, & Wilson V (2001). Further evidence for the developmental significance of teacher-student relationships: Peers’ perceptions of support and conflict in teacher-child relationships. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph GE, & Strain PE (2003). Comprehensive evidence-based social-emotional curricula for young children: An analysis of efficacious adoption potential. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kam C, Greenberg M, & Walls C (2003). Examining the role of implementation quality in school-based prevention using the PATHS curriculum. Prevention Science, 4, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, & Cicchetti D (1997). Children’s relationships with adults and peers: An examination of elementary and junior high school students. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Downer JT, Hamre BK, Justice LM, & Pianta RC (2010). Teaching consultation and children’s language and literacy development during pre-kindergarten. Applied Developmental Science, 14(4), 179–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Pianta RC, Hamre BK, Downer JT, Barbarin O, Bryant D, … Howes C (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79, 732–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DE, Rizza MG, & Bliss L (2000). Implementing empirically supported interventions: Teacher-child interaction therapy. Psychology in the Schools, 37, 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin M, & Joyce B (1980). Psychological states and staff development. Theory Into Practice, 19, 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic S (2004). The importance of implementation fidelity. Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 4, 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison FJ, Cameron CE, Connor CM, Strasser K, & Griffin E (unpublished manuscript). Pathways to Literacy classroom observations coding manual. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (1999). Academic Rating Scale. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Teacher Quality. (2005). Increasing the odds: How good policies can yield better teachers. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health, & Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. (2000). The relation of child care to cognitive and language development. Child Development, 71, 960–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo F, Hanish L, Martin C, Fabes R, & Reiser R (2007). Preschoolers’ academic readiness: What role does the teacher-child relationship play? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22, 407–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcel GS, O’Hara-Tompkins NM, Harrist RB, Basen-Engquist KM, McCormick LK, Gottlieb NH, & Eriksen MP (1995). Diffusion of an effective tobacco prevention program: Part II. Evaluation of the adoption phase. Health Education Research, 10, 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penuel WR, Fishman BJ, Yamaguchi R, & Gallagher LP (2007). What makes professional development effective? Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 44, 921–958. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC (2001). The Student Teacher Relationship Scale. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R, & Hamre B (2001). Students, Teachers, and Relationship Support (STARS). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R, Howes C, Burchinal M, Bryant D, Clifford R, Early C, et al. (2005). Features of pre-kindergarten programs, classrooms, and teachers: Do they predict observed classroom quality and child-teacher interactions? Applied Developmental Science, 9(3), 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, & Nimetz SL (1991). Relationships between children and teachers: Associations with classroom and home behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 12, 379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, … Udry JR (1998). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. In Muuss RE, & Porton HD (Eds.), Adolescent behavior and society: A book of readings, (5th ed.), (pp. 376–395). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Graham JW, & Hansen WB (1993). Diffusion of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: Predictors of program implementation. Preventive Medicine, 22, 237–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach LA, Grana R, Sussman S, & Valente TW (2006). Type II translation: Transporting prevention interventions from research to real-world settings. Evaluation and Health Professions, 29, 302–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandholtz JH (2002). Inservice training or professional development: Contrasting opportunities in a school/university partnership. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 815–830. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES, & Edgerton M (1985). Parent and child correlates of parental modernity. In Sigel IE (Ed.), Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children (pp. 287–318). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan SM, Edwards CP, Marvin CA, & Knoche LL (2009). Professional development in early childhood programs: Process issues and research needs. Early Education & Development, 20, 377–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RB, Measelle JR, Armstrong JM, & Essex MJ (2005). Trajectories of classroom externalizing behavior: Contributions of child characteristics, family characteristics, and teacher-child relationship during the school transition. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sobol DF, Dent CW, Gleason L, Brannon BR, Johnson CA, & Flay BR (1989). The integrity of smoking prevention curriculum delivery. Health Education Research, 4, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TK, Schmidt F, Pepler D, & Hodgins H (1998). A comparison of eclectic treatment with Webster-Stratton’s parents and children series in a children’s mental health center: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 29, 221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C (1990). The teachers and children’s videotape series: Dina Dinosaur’s social skills and problem-solving curriculum. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, & Hammond M (1997). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65 93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, & Reid J (1999, November). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: The importance of teacher training. Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslow M, & Martinez-Beck I (Eds.). (2005). Critical issues in early childhood professional development. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. [Google Scholar]