Abstract

Poly(aniline-co-o-anthranilic acid)-chitosan/silver@silver chloride (PAAN-CS/Ag@AgCl) nanohybrids were synthesized using different ratios of Ag@AgCl through a facile one-step process. The presence of CS led to the formation of the nanohybrid structure and prevented the aggregation of the copolymer efficiently. The synthesized nanohybrids were fully characterized by transmission electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and thermogravimetric analysis. (E)-N′-(Pyridin-2-ylmethylene) hydrazinecarbothiohydrazide I was prepared using thiosemicarbazide and confirmed by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and FTIR analyses. Loading of the azine derivative I using various concentrations at different pH values onto the nanohybrid was followed by UV–vis spectroscopy. Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherm models were used to describe the equilibrium isotherm, and the adsorption followed the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. A pseudo-second-order model was used to describe the kinetic data. A PAAN-CS/Ag@AgCl nanohybrid loaded with azine I interestingly showed efficient antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus more than the azine derivative I. The release of azine I at different pH values (2–7.4) was investigated and the kinetics of release were studied using zero-order, first-order, second-order, Higuchi, Hixson–Crowell, and Korsmeyer–Peppas equations.

Introduction

Due to the severity of the action of drug-resistant bacteria, it is essential to prepare new antimicrobial agents to overcome the drawbacks of using conventional antibiotics.1 Among many kinds of antimicrobial agents, there are numerous silver delivery systems, including those that supply silver from ionic compounds such as silver chloride and those that deliver silver from metallic nanocrystalline silver.2−4 Metal-coated dressings release a low silver concentration over a long period; however, Ag ions produce a high concentration, but frequent application up to 12 times a day is required. Sulfa drugs were combined with silver in silver sulfadiazine and reported as the most effective antibiotic for topical treatment of burns and wounds.5,6 Many researchers were interested in silver nanoparticles (NTs); however, a few reports were published on biogenic AgCl NTs.7

For prevention of the agglomeration of Ag/AgCl NTs, several polymers have been used as effective dispersing and stabilizing agents including polysaccharides, gelatin, chitosan, and conducting polymers.8−12 The extensive network of hydrogen bonds of the template protects the Ag NTs from aggregation. Chitosan (CS), a linear polysaccharide composed primarily of β-(1 → 4)-linked glucosamine (2-amino-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranose), can be used for hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs because of its amphiphilic feature. It is characterized by its biocompatibility, biodegradation, and nontoxicity and considered as a mucoadhesive and adsorption enhancer. Moreover, CS can improve the dispersibility of polymers, leading to the production of NTs.13 The antibacterial effects of CS were attributed to the electrostatic interactions between the protonated amino groups of CS and bacterial phosphoryl groups and lipopolysaccharide cell membranes, which damage the membrane bacteria and the content of the cell.14−16 Improvement in the antimicrobial capabilities with a controlled release profile was reported for levofloxacin-,17 rifampicin-,18 moxifloxacin-,19 gentamicin-,20 and clindamycin-loaded CS.21

Polyaniline (PANI) has wide potential application in biomedical applications; however, the data on its biocompatibility are rare.6,22−24 The stability of PANI with poor biodegradability may cause bioaccumulation. In addition, caution should be taken during application due to the carcinogenic effect of the aniline dimer. Moreover, PANI is only soluble in a few solvents (N-methyl pyrrolidone), thus limiting the performance of the polymer in biological applications. Stabilization of PANI with biocompatible polymers favors the use of polymeric NTs in biological applications.24 Incorporation of PANI into CS developed a biodegradable polymer with high biocompatibility and nontoxicity.25 Sultana et al. examined the biodegradability of CS/PANI by growing microbial communities up to 2125 days in CS/PANI. The excessive growth of microbial communities confirms the nontoxicity of CS/PANI, and the clearance of the synthesized copolymer verifies the biodegradability.25 These results confirm that CS/PANI can be used safely in biomedical applications.2 On the other hand, the development of an aniline/anthranilic acid copolymer (PAAN) sterically increases the interchain distance, favoring the formation of six-membered chelates through intramolecular interaction between carboxylate groups and cation radical nitrogen atoms,27 and can be used for immobilization of bioactive species.

Interestingly, Ag NPs incorporated into PANI-grafted CS supported the excessive growth of microbial communities, leading to the biodegradability of the polymeric sample.26 The slow and lasting nontoxicity degradation for a long time would have many applications such as drug delivery and tissue engineering.25 The efficacy of different bioactive substances was improved using targeted drug delivery strategies by improving the bioavailability with localization of a high concentration of drugs in the infected sites.

Azine core structures are an important class of heterocyclic compounds that include a N–N bond with pharmacological and biological activities. Azine derivatives are used as an ion-selective optical sensor,28−30 materials of thermal conduction,25 dye lasers, antimalarial, antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antitumor, anticonvulsant, and antimicrobial agents.31 Hydrazone-based azines were extensively studied in the literature in the area of drug discovery. Interestingly to empoly these kind of compounds as a linker in drug release research are the challange. This linker plays a crucial role in determining the pharmacokinetic properties, therapeutic index, selectivity, and overall success of the drug. Hydrazones are acid-cleavable linkers that have been designed to be stable in the neutral blood pH but hydrolyzed in the cellular acidic environment.32 Development of a new kind of linker that can be utilized as a linker and carrier is a challenge. Azines with an appropriate acceptor or donor substituent and a macroscopic dipole moment can be established, which make them a suitable material to use for nonlinear optical materials.33 Via lone pairs of the N atom, azines can donate 2:8 electrons; in binding to metal centers, azines show versatile coordinating properties,34,35 and also in different types of organic ligands, N–N bond activation is important, particularly in organic synthesis and catalysis.36−38

Evolution of resistant strains to the metal drugs encourages us to design a new carrier for azines and study the efficacy of these nanocarriers against various types of bacteria such as Escherichia coli. AgCl@PANI is researched well, but a relative poly(aniline-co-o-anthranilic acid (PAAN) copolymer is less researched in the literature. The presence of carboxylic groups in anthranilic acid improves the solubility due to the weakening of the interchain by hydrogen bonds. To the best of our knowledge, there is no reported work on using PAAN@Ag/AgCl as carriers for azine I. In the present work, we introduced PAAN-Ag@AgCl nanohybrids with different ratios of Ag@AgCl (II and III) using chitosan as a dispersing medium and FeCl3 as an oxidant. The presence of copolymer/CS and Ag@AgCl may result in synergistic improvement of the antimicrobial activity of the hybrid. In addition, the presence of CS as a natural compound with its biocompatibility may impart the hybrid with a valuable pharmaceutical property of binding or crossing certain biomembranes. The hybrids (II and III) and azine I loaded hybrids (IV and V) were characterized using various spectroscopic and microscopic techniques including Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) . Also, the release behavior and antimicrobial activity were examined.

Results and Discussion

Polyanilines have been extensively studied in the literature,39,40 but only a few researchers give attention to their carboxylate derivatives.20 Amphiphilic copolymers have attracted great attention in the pharmaceutical arena due to the presence of hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments that favor the loading of a wide range of hydrophobic drugs.

The nanohybrids were prepared via chemical oxidative copolymerization of aniline/o-anthranilic acid in the presence of CS and AgNO3. It is worth noting that the amine group in CS is protonated at a low pH and this protonated structure inhibits the aggregation of copolymers during the synthesis process and stabilizes the AgCl/Ag NTs.41 Chitosan was used as a steric stabilizer during polymerization of aniline/anthranilic acid to prevent the precipitation of copolymers during preparation. FeCl3 has a dual function during the formation of a nanohybrid: ferric ions act as an oxidizing agent for aniline/AA to start the polymerization, while chloride ions donate the building block of silver chloride NTs. FeCl3 has a low oxidant potential (E° = +0.75 V) in comparison with APS (E° = +2.05 V) to avoid the fast nucleation that may lead to macroscopic particles of the aniline/o-anthranilic copolymer.

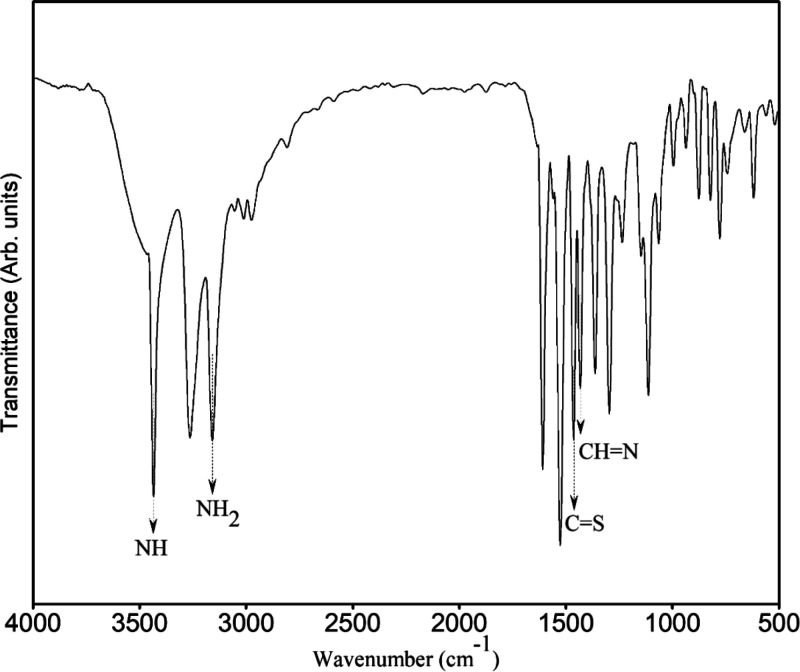

The requisite azine derivative for this study was synthesized as depicted in Scheme 1 and characterized by the 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and FTIR spectra of (E)-N′-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene) hydrazinecarbothiohydrazide I as shown in Figures 12−3.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of AzineI.

Figure 1.

1H-NMR spectrum of azine I.

Figure 2.

13C-NMR spectrum of azine I.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrum of azine I.

1H-NMR (Figure 1) exhibited the characteristic features of the compound: broad singlet at δ = 11.63 and 8.17 ppm assigned for NH and NH2, respectively. The aromatic proton appeared between 8.56 and 7.37 ppm, and in between this region, the methine proton (CH=N) appeared at δ = 8.07 ppm. 13C-NMR (Figure 2) exhibited the number of carbons, which agreed with the assigned structure, for example, at δ = 178.4 (C=S), 153.3 (C=N), 149.3 (C=N), 142.5, 136.6, 124.1, and 120.3 (C-aromatic). The functional groups were assigned based on the FTIR spectrum (KBr, cm–1) (Figure 3) as follows: 3435 (NH), 3264 , and 3159 (NH2); 1527 Ar(C=C), 1464 (C=S), and 1433 (CH=N).

The X-ray diffraction pattern of II (Figure 4) clearly shows the coexistence of two well-crystallized phases of AgCl and Ag metal NTs. The peaks at 38.38° and 44.59° represent the diffraction of hkl planes (111) and (200) of the face-centered cubic metallic Ag NTs. On the other hand, the peaks at 28.10°, 32.95°, 46.49° represent the diffraction of hkl planes (111), (200), (220) of AgCl with a face-centered cubic structure phase. The ratio of Ag to AgCl is calculated to be 48.9%/59.1%, and crystallite sizes of Ag and AgCl are calculated to be 5.34 and 4.4 nm, respectively. For III (Figure 4a), the diffraction peaks at 28.80°, 33.32°, and 47.89° are assigned to (111), (200), and (220) planes of the AgCl face-centered cubic structure, with peaks at 37.90°, and 40.15° corresponding to (111), and (220) of Ag with the AgCl/Ag ratio of 70.7%/29.3%. The crystallite sizes of Ag and AgCl are calculated to be 2.2 and 2.8 nm, respectively, using Scherrer’s equation. It was worth noting that the concentration of AgNO3 in the preparation feed affected the percentage of Ag NTs in the nanohybrids. The Ag NTs have been recognized in the diffractogram due to the reduction of Ag+ cations by aniline during the polymerization process. For IV, after loading of azine I (Figure 4b), the diffraction peaks of AgCl that appeared at 28.01°, 32.44°, and 46.97° were not affected; however, the peaks characteristic to Ag were shifted to 36.89° and 40.75°. For V (Figure 2b), the diffraction peaks of AgCl were slightly shifted to 28.21°, 31.70°, 45.78° and for Ag, the peaks were shifted to 37.35°, and 40.09°, confirming the loading of azine I. The peaks at 26°, 32°, and 39° related to Ag oxides (AgO and Ag2O) are absent.31 A broad peak is observed at 22°, confirming the amorphous structure of the copolymer. In nanohybrids loaded with azine I, peaks characteristic to the crystal structure of azine I in V at 24.88°, 28°, and 32.5° are detected. However, in IV, these peaks are not seen due to the low amount of the loaded azine I.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of (a) PAAN and the nanohybrids II and III and (b) azine I and loaded nanohybrids IV and V.

TEM has been employed to study the morphology and size of the hybrid. The TEM micrographs (Figure 5) show typical features of the nanohybrid II and azine-loaded nanohybrids IV and V. Images for the nanohybrid II (Figure 5a,b) show the presence of interconnected dark spheres with an average size of 83.5 nm and surrounded by light (CS) areas without aggregation. This confirms that the CS matrix is a perfect host matrix to provide NTs and prevent Ag/AgCl@PAAN aggregation. TEM images of the azine-loaded nanohybrids IV and V show a spherical morphology with average sizes of 51.6 and 53.5 nm, respectively. Careful inspection in Figure 5d,e confirms that the particles are consisted of an assembly of smaller spheres. High-resolution TEM images shown in Figure 5e proved the presence of AgCl in the spheres. The lattice fringe spacing was found to be 1.8 nm, which corresponds to the lattice plane (111) of AgCl. The strong affinity of AgCl NPs for nitrogen and oxygen atoms results in good dispersion of the particles within the matrix.

Figure 5.

TEM images of (a, b) II, (c, d) IV, and (e, f) V at different magnifications.

The FTIR spectra of CS, PAAN, PAAN-CS/Ag@AgCl (II and III), and PAAN-CS/Ag@AgCl loaded with azine (IV and V) are shown in Figure 6. The CS spectrum shows bands at 3440 cm–1 (stretching vibrations of O–H and N–H), 2921 cm–1 (C–H stretching), 1649 cm–1 (bending NH2), 1425 cm–1 (NH stretching (amide II)), 1383 cm–1 (symmetrical angular deformation of CH3), 1030 cm–1 (C–O–C stretching vibration), 1153 cm–1 ((1 → 4) glycoside bridge), and 896 cm–1 (antisymmetric bending of the C–O–C bridge).42 Two main absorption bands of the PAAN copolymer appear in the spectrum at 1564 and 1477 cm–1. These bands can be attributed to the C=C vibrations of quinoid and benzenoid units, respectively. The number of benzenoid units was almost lesser than the number of quinoid units in PAAN as there was an apparent difference in the relative intensity of the quinoid-to-benzenoid band. This reveals the degree of oxidation in the polymer chains.43 The peak at 3220 cm–1 indicates N–H stretching. The spectra of II and III have four major absorption bands at 800, 1085, 1629, and 3443 cm–1. These bands can be attributed to the out-of-plane CH bending, C—O vibration, C=O vibration, and NH2 stretching, respectively. Also, the peak obtained in the range of 500–600 cm–1 is attributed to the Ag nanohybrid.25 In IV and V, the peak characteristic to C=O at 1629 cm–1 was shifted to 1647 cm–1, confirming the physical interaction of azine I with the nanohybrid.44

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of CS, PAAN, and nanohybrids before (II and III) and after loading (IV and V) of azine I.

Thermal analyses of PAAN, II, and III were carried out by TGA. The results were compared with those loaded with azines (IV and V) as shown in Figure 7 (Table 1). For PAAN, the weight loss initial fraction between 120 and 150 °C was due to the water molecule loss and moisture present in the polymer matrix, and the second stage fraction of the weight loss between 150 and 350 °C was due to the removal of CO2 molecules from PAAN. Meanwhile, the third stage between 350 and 640 °C was due to copolymer chain degradation. The residue percentage was found to be 1.7%.45 TGA of the nanohybrids PAAN-CS/Ag@AgCl (II and III) shows also three stages of decomposition. The first step is due to moisture loss, the second stage is due to the CS degradation between 300 and 450 °C, and the third stage represents polymer degradation between 450 and 570 °C. Meanwhile, for those loaded with azine (IV and V), TGA discloses three weight loss stages. The weight loss initial fraction between 120 and 150 °C was attributed to the water molecule loss and moisture present in the polymer matrix, the second stage fraction of the weight loss between 400 and 580 °C was attributed to CS degradation and acid dopant departure,46 and the third weight loss step between 580 and 740 °C was attributed to PAAN chain degradation.47

Figure 7.

TGA thermograms of PAAN and nanohybrids before (II and III) and after loading (IV and V) of azine I.

Table 1. TGA Data Range of Step and Residue % of PAAN and Nanohybrids before (II and III) and after Loading (IV and V) of Azine I.

| code | range of step (°C) | residue % |

|---|---|---|

| PAAN | 120–150 | 96.5 |

| 150–350 | 88.7 | |

| 350–700 | 1.7 | |

| II and III | 120–150 | 93 |

| 300–450 | 76.4 | |

| 450–570 | 24.2 | |

| 800 | 11.7 | |

| IV | 120–150 | 96.2 |

| 400–580 | 71.5 | |

| 580–740 | 57.4 | |

| 800 | 19.9 | |

| V | 120–150 | 96 |

| 400–580 | 59.7 | |

| 580–740 | 29 | |

| 800 | 25.4 |

The amount of I uptake onto the nanohybrid is demonstrated in Figure 8. The UV–vis spectra for loading azine I onto nanohybrids II and III are shown in Figure 8a,b, respectively. At pH = 2, the most efficient azine I loading was found on II (55%) followed by III (38%) at pH = 2, while by studying the loading at different pH values, the loadings found on both II and III at pH = 5 were 54, and 31.78%, respectively, and at pH = 9, the loading was 11%. Various kinetic equations were used to study the azine I adsorption kinetic mechanism, including pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order, and the isotherm process was studied by Langmuir, Temkin, and Freundlich models, which are formulated in eqs 6–8. For each model, the coefficient of slope regression (R2) and the constant rate (K) are graphically determined and used to demonstrate the mechanisms (Table 2). The azine I adsorption process at pH 2 was found to follow second-order kinetics rather than the other models (0.976 for II and 0.9996 for III). As shown, with low correlation coefficients with empirical data, the Freundlich and Temkin isotherms show poor agreement. However, the Langmuir isotherm model is the highly fitted model that shows good agreement with the empirical data with the highest regression coefficients (0.9999 for II and 0.9996 for III). Figures 9 and 10 show pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order for II and III at pH 2, 5, and 9. The data obtained show that by applying pseudo-second order (eq 6), a linear relationship was obtained, which suggests that adsorption of azine I onto the nanohybrid is fitted with pseudo-second order for both II and III at different pH values.

Figure 8.

UV–vis spectra for loading azine I into nanohybrids (a) II and (b) III at pH = 2 using 20 ppm.

Table 2. Kinetic Parameters for Adsorption of Azine I onto AgCl/PAAN-CS (IV and V) and Adsorption Isotherm Parameters at pH = 2.

|

IV |

V |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | model coefficient | R2 | model coefficient | R2 |

| pseudo-first order | Qe = 22.0023 mg g–1 | 0.9115 | Qe = 17.2845 mg g–1 | 0.9779 |

| K1 = 0.0868 min–1 | K1 = 0.0085 min–1 | |||

| pseudo-second order | Qe = 22.0023 mg g–1 | 0.9760 | Qe = 17.2845 mg g–1 | 0.9981 |

| K2 = 40.6765 g mg–1 min–1 | K2 = 62.6728 g mg–1 min–1 | |||

| Langmuir model | b = 0.0633 L mg–1 | 0.9999 | b = 0.0682 L mg–1 | 0.9996 |

|

|

|||

| Freundlich model | 1/n = 0.2397 | 0.9739 | 1/n = 0.2901 | 0.9987 |

| n = 4.1718 | n = 3.4470 | |||

| Kf = 36.1234 mg–1 | Kf = 38.4241 mg–1 | |||

| Temkin isotherm | B = 29.957 J mol–1 | 0.9282 | B = 29.454 J mol–1 | 0.9760 |

| Kt = 0.5038 | Kt = 0.4890 | |||

Figure 9.

(a) Pseudo-first order and (b) pseudo-second order for adsorption of azine I onto II at pH 2, 5, and 9.

Figure 10.

(a) Pseudo-first order and (b) pseudo-second order for adsorption of azine I onto III at pH 2, 5, and 9.

The release behavior of azine I from IV and V loaded at pH = 2 (Figure 11) show that the release of azine I at pH 2 is faster than that at pH 7.4. On the other hand, azine I release from the nanohybrid III is faster than that from II at pH 2. To evaluate the mechanism that controls the release process, first-order (1), Higuchi (2), Hixson–Crowell (3), and Korsmeyer–Peppas (4) kinetic models48 were applied using eqs 1–4 (Table 3).

Figure 11.

Release profile of azine I from nanohybrids (a) II and (b) III at pH = 2 and 7.4.

Table 3. Analysis of the Kinetic Models of the Release Profiles of Azine I Samples for IV and V at pH 2 and 7.4.

| zero

order |

first

order |

Higuchi |

Hixson–Crowell |

Korsmeyer–Peppas |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | K1 | R2 | K2 | R2 | K3 | R2 | K4 | R2 | K5 | R2 | n |

| 2 IV | 0.3114 | 0.8067 | 0.0019 | 0.8253 | 0.6227 | 0.8067 | 0.1038 | 0.8067 | 0.4963 | 0.7565 | 0.2246 |

| 7.4 | 0.1048 | 0.7183 | 0.0005 | 0.7264 | 0.2097 | 0.7183 | 0.0349 | 0.7183 | 0.2427 | 0.8297 | 0.1177 |

| 2 VV | 9.5785 | 0.9151 | 0.0035 | 0.9376 | 0.9432 | 0.9095 | 0.1462 | 0.9164 | 2.365 | 0.9422 | 0.3401 |

| 7.4 | 0.0421 | 0.9029 | 0.0002 | 0.9058 | 0.0841 | 0.9029 | 0.014 | 0.9029 | 0.2288 | 0.87 | 0.4311 |

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

To find out the mechanism of azine I release, 60% azine I release data were fitted in the Korsmeyer–Peppas model. In the Korsmeyer–Peppas model, the n value is used to characterize different release mechanisms. If n ≤ 0.45 corresponds to a Fickian diffusion mechanism, then n > 0.45 corresponds to non-Fickian transport.

In these results, the n value of the Korsmeyer–Peppas model is <0.45, which indicates that the release mechanism corresponds to a Fickian nondiffusion mechanism (Table 3). It was found that the release of azine I from IV and V nanohybrids follows a first order at different pH values under investigation. Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-encapsulated clotrimazole and econazole NTs demonstrated a controlled drug release over 5–6 days in contrast to 3–4 h of drugs.29

The nanohybrids II and III exhibited antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and E. coli with zones of inhibition of 18.3 and 26.3 mm and 30 and 14 mm, respectively (Figure 12 and Table 4). It was reported that silver/silver oxide NTs exhibited antimicrobial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with zones of inhibition of 7, 9, and 11 mm,49 respectively. It was worth noting that the efficacy of azine I against S. aureus and E. coli was improved after loading azine I on the nanohybrids IV and V, respectively, as shown in Figure 12. PANI/Ag NPs were tested against E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa, and the results showed that the efficacy of antimicrobial activity of PANI/Ag NPs was improved compared with pure PANI or Ag NPs in the same test condition.50

Figure 12.

(A) Antibacterial activity of azine I and the nanohybrids before (II and III) and after loading (IV and V) of azine I against S. aureus and E. coli. (B, C) Zones of inhibition produced by azine I and the nanohybrids before (II and III) and after loading (IV and V) of azine I against S. aureus (B) and E. coli (C).

Table 4. Inhibition Zones (mm) of Loaded and Free Carriers against Various Microorganisms.

| code | S. aureus | E. coli |

|---|---|---|

| azine I | 11 ± 0.2 mm | 9 ± 0.3 mm |

| II | 18.3 ± 0.3 mm | 30 ± 0.4 mm |

| III | 26.3 ± 0.1 mm | 14 ± 0.2 mm |

| IV | 25.6 ± 0.6 mm | 28 ± 0.1 mm |

| V | 18 ± 0.1 mm | 19 ± 0.1 mm |

Conclusions

In summary, novel polyaniline/anthranilic acid copolymer-chitosan/silver@silver chloride (PAAN-CS/Ag@AgCl) nanohybrids have been prepared by in situ copolymerization of anthranilic acid and aniline in the presence of silver nitrate and CS as a dispersing medium through a facile one-step process. The presence of CS leads to the formation of the nanohybrid structure and prevents the aggregation of the copolymer efficiently. FeCl3 acts as an oxidizing agent for aniline/anthranilic acid to start the polymerization, while chloride ions donate the building block of silver chloride NPs. The nanohybrid spheres with different ratios of Ag/AgCl (II and III) have been loaded with azine I. The release at pH 7.4 is slower than in an acidic medium at pH 2, and the mechanism corresponds to a Fickian diffusion mechanism. Results support the claim that nanohybrids loaded with azine I have synergistic capacity against S. aureus and E. coli. The effect of a high loading concentration of nanohybrids and their application effects on different antimicrobial strains will be considered in the near future.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

Aniline (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was refined with zinc dust through double distillation. Nitric acid, methanol, glacial acetic acid, hexane, ethanol, FeCl3, CS (molecular weight: 100,000–300,000; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), NaOH pellets (Acros, USA), pyridine carboxyaldehyde, thiosemicarbazide (Acros, USA), and anthranilic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used as provided.

Instruments

The composition of the nanohybrids was characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Shimadzu FTIR-8101 A) in the range of 4000–400 cm–1. The crystallinity and phases of nanohybrids were examined by an X-ray diffractometer (Philips PW 1710) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54060 Å), a voltage of 40 kV, and a current of 30 mA in the range of 2–80° with 2°/min scanning rate. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs were taken to investigate the morphology of the nanohybrid (JEM 2100 JEOL) with an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. An aqueous suspension of samples was drop-casted onto carbon-coated cobber grids, followed by drying of the samples on filter paper in ambient conditions. TGA was performed to test the nanohybrid thermal stability (25–600 °C) in which the weight residue was reported separately using 7 mg of sample at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min and a nitrogen gas flow of 10 mL/min for each sample in the TG instrument (TGA-50). The UV–visible absorption spectra were obtained from a Shimadzu UV-2101 PC spectrophotometer.

Preparation of Aniline/Anthranilic Acid Copolymers

The aniline/anthranilic acid copolymer (PAAN) was prepared by in situ chemical oxidation polymerization using aniline and anthranilic acid (5:1 molar ratio). Typically, 2.74 g (20 mmol) of o-anthranilic acid and 9.12 mL (100 mmol) of aniline were dissolved in 2 M HCl and stirred for 30 min; after that, a solution of ferric chloride (2.2 g dissolved in 5 mL of water) was added, stirred until a dark green precipitate was formed, and collected by filtration. The dark green precipitates of PAAN were washed several times to eliminate the excess oxidant (monomer and oligomer) with distilled water and ethanol and dried at 60 °C for 24 h (yield, 12 g).

Preparation of Azine I

The hydrazone-based azine I was prepared according to a previous report.51 Briefly, a solution of pyridine carboxyaldehyde (5.0 mmol, 535 mg), 2 mL of acetic acid, and thiosemicarbazide (5.0 mmol, 531 mg) in EtOH (20 mL) was mixed and refluxed for 3 h, and the reaction was followed by TLC using 20% EtOAc/n-hexane as an eluent. The product was immediately precipitated and the reaction mixture was cooled down, filtered off, and washed with EtOH to afford the final product C7H9N5S (I) with a yield of 87%. C7H9N5S (I). 1H-NMR [400 MHz, DMSO-d6] δ: 11.63 (s, 1H, NH), 8.56 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 8.34 (brs, s, 1H, NH2), 8.27(d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 8.17 (brs, s, 1H, NH2), 8.07 (s, 1H, CH=N), 7.81 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar-H), 7.37 (t, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz, Ar-H); 13C-NMR [100 MHz, DMSO-d6] = 178.4 (C=S), 153.3 (C=N), 149.3 (C=N), 142.5, 136.6, 124.1, 120.3 (C-aromatic); anal. calcd. (%): C, 43.06; H, 4.65; N, 35.87; S, 16.42; found: C, 43.07; H, 4.65; N, 35.89; S, 16.43; FTIR (KBr, cm–1): 3435 cm–1 (NH), 3264 cm–1, and 3159 cm–1 (NH2); 1527 cm–1 Ar(C=C),1464 cm–1 (C=S), and 1433 cm–1 (CH=N).

Preparation of the PAAN/CS-Ag@AgCl Nanohybrid II

The synthesis of the PAAN/CS-Ag@AgCl hybrid was performed according to the procedure reported by Salahuddin et al.52 with slight modification. Briefly, 0.5 mL (5.4 mmol) of aniline monomer, 0.15 g (1 mmol) of anthranilic acid (AA), and 0.01 g (0.0774 mmol) of AgNO3 were added to 40 mL of CS solution (1 wt % in 0.05 M HNO3) and stirred for 24 h until complete dispersion. In an ice bath, 2.2 g of FeCl3 dissolved in 25 mL of H2O was introduced to the dispersion and left under sonication for 2 h. The polymerization under a nitrogen atmosphere was conducted for 12 h and the resulting product was purified using a membrane bag (Spectrum Medical Industries, Inc.; Mw cut-off: 3500 Da) in 0.05 M HNO3. The resulting product (PAAN/CS-Ag@AgCl (II)) was collected by centrifugation (15,000 rpm for 20 min) and dried in an oven at 80 °C. The same procedure was done using 0.05 g (0.0003 mmol) of AgNO3 to afford the PAAN/CS-Ag@AgCl nanohybrid III.

Loading of Azine I on PAAN/CS-Ag@AgCl Nanohybrids IV and V

Azine I was loaded into nanohybrids II and III to afford IV and V, respectively, by diffusion. Various concentrations of azine I (10, 20, and 30 ppm) were stirred with 20 mg of PAAN/CS-Ag@AgCl nanohybrid (II or III) and the study was focused on the concentration of 20 ppm of azine I which shown the optimum results. The mixture was then centrifuged, and absorption of supernatant solution was measured by UV at λmax = 314 nm. The concentration of the free azine I was then determined from the azine I calibration curve, and the azine I loading efficiency (LE) (%) was calculated from eq 5.53

| 5 |

Adsorption Isotherm Models

Langmuir isotherm, Freundlich isotherm, and Temkin isotherm were applied on the loading of azine I onto II and III hybrids (eqs 6–8).

| 6 |

where Ce is the azine I equilibrium constant, qe is the azine I-loaded amount at equilibrium, the maximum adsorption capacity is qmax (mg/g), and the Langmuir constant related to the energy of adsorption capacity is b.

| 7 |

where qe is the azine I concentration in solid at equilibrium, Ce is the azine I concentration in solution at equilibrium, Kf is the Freundlich isotherm constant related to adsorption capacity, and n is the Freundlich isotherm constant related to adsorption intensity.

| 8 |

where b is the Temkin constant, which is related to the heat of sorption (J mol–1), and Kt is the Temkin isotherm constant (L g–1).

Adsorption Kinetic Models

Pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order were used to explain the azine I loading process onto the II and III nanohybrids.54

| 9 |

| 10 |

where qe and qt are the amounts of azine I adsorbed at equilibrium and at time t, respectively, K1 is the pseudo-first-order rate constant, and K2 is the pseudo-second-order rate constant.

Release Measurement

The in vitro release profile of azine I from loaded nanohybrids was measured by placing 20 mg of sample suspended in the dialysis membrane in 0.3 mL of buffer solution (the buffer was prepared according to Abdelwahab et al.55) and immersed in 25 mL of buffer medium at pH 2 and 7.4 under stirring (400 rpm) at 25 °C. Then, 2 mL of buffer solution was collected at each time to determine the concentration of azine I by a spectrophotometer at λmax = 314.

Antimicrobial Activity

The antibacterial activity of carriers against E. coli and S. aureus bacterial strains was tested. The zone of inhibition was measured by the agar diffusion method.56 The nutrient agar media were prepared, sterilized, and poured into sterile Petri dishes. Media were allowed to solidify, and then the bacteria were inoculated from the cultivated bacterial suspension with the aid of the swapping method followed by boring in the plate with the aid of a cork-borer to achieve a certain size of the cavity. Nanohybrid suspensions before (II and III) and after loading (IV and V) azine I were poured in the hole and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The zone of inhibition was measured in mm, and bacterial activity was compared with free azine I.57

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for providing funding to this research group (no. RGP-257). The authors thank the Deanship of Scientific Research and RSSU at King Saud University for their technical support.

Author Present Address

∇ Institute of Basic and Applied Sciences, Egypt-Japan University of Science and Technology, Alexandria 21934, Egypt

Author Present Address

# Department of Chemistry, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Laws M.; Shaaban A.; Rahman K. M. Antibiotic resistance breakers: current approaches and future directions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 43, 490–516. 10.1093/femsre/fuz014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra L. E.; Tarres L.; Bongiovanni S.; Barbero C. A.; Kogan M. J.; Rivarola V. A.; Bertuzzi M. L.; Yslas E. I. Assessment of polyaniline nanoparticles toxicity and teratogenicity in aquatic environment using Rhinella arenarum model. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 84–92. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayad M.; El-Hefnawy G.; Zaghlol S. Facile synthesis of polyaniline nanoparticles; its adsorption behavior. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 217, 460–465. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S. A.; Das S. S.; Khatoon A.; Ansari M. T.; Afzal M.; Hasnain M. S.; Nayak A. K. Bactericidal activity of silver nanoparticles: A mechanistic review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 756. 10.1016/j.mset.2020.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atiyeh B. S.; Costagliola M.; Hayek S. N.; Dibo S. A. Effect of silver on burn wound infection control and healing: review of the literature. Burns 2007, 33, 139–148. 10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korupalli C.; Kalluru P.; Nuthalapati K.; Kuthala N.; Thangudu S.; Vankayala R. Recent Advances of Polyaniline-Based Biomaterials for Phototherapeutic Treatments of Tumors and Bacterial Infections. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 94. 10.3390/bioengineering7030094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G. B.; Guo J.; Hu J.; Shan D.; Yang J.. Novel applications of urethane/urea chemistry in the field of biomaterials. In Advances in Polyurethane Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 115–147, 10.1016/B978-0-08-100614-6.00004-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh N. D.; Nguyen T. T. B.; Nguyen T. H. Preparation and characterization of silver chloride nanoparticles as an antibacterial agent. Adv. Nat. Sci.: Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 045011 10.1088/2043-6262/6/4/045011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S. K.; Mishra A. K.; Arotiba O. A.; Mamba B. B. Chitosan-based nanomaterials: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 59, 46–58. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima S.; Miya M.; Iwamoto R.; Yoshikawa S. Highly deacetylated chitosan and its properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1983, 28, 1909–1917. 10.1002/app.1983.070280607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed M. A.; Syeda J. T. M.; Wasan K. M.; Wasan E. K. An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 53. 10.3390/pharmaceutics9040053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q.; Sun Y.; Cong H.; Hu H.; Xu F.-J. An overview of chitosan and its application in infectious diseases. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2021, 1340–1312. 10.1007/s13346-021-00913-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N.; Ferro V. Recent advances in chitosan-based nanoparticulate pulmonary drug delivery. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 14341–14358. 10.1039/C6NR03256G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. W.; Thomas R. L.; Lee C.; Park H. J. Antimicrobial activity of native chitosan, degraded chitosan, and O-carboxymethylated chitosan. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 1495–1498. 10.4315/0362-028X-66.8.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide S. S. Chitin-chitosan: properties, benefits and risks. Nutr. Res. 1998, 18, 1091–1101. 10.1016/S0271-5317(98)00091-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri J.; Raichura Z.; Khan T.; Momin M.; Omri A. Chitosan Nanoparticles-Insight into Properties, Functionalization and Applications in Drug Delivery and Theranostics. Molecules 2021, 26, 272. 10.3390/molecules26020272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar M. C.; Sousa J. J. S.; Pais A. A. C. C.; Cardoso O.; Murtinho D.; Serra M. E. S.; Tewes F.; Olivier J.-C. Optimization of levofloxacin-loaded crosslinked chitosan microspheres for inhaled aerosol therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 96, 65–75. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg T.; Rath G.; Goyal A. K. Inhalable chitosan nanoparticles as antitubercular drug carriers for an effective treatment of tuberculosis. Artif. Cells, Nanomed., Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 997–1001. 10.3109/21691401.2015.1008508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura C. A.; Tommasini S.; Crupi E.; Giannone I.; Cardile V.; Musumeci T.; Puglisi G. Chitosan microspheres for intrapulmonary administration of moxifloxacin: interaction with biomembrane models and in vitro permeation studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 68, 235–244. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-C.; Li R.-Y.; Chen J.-Y.; Chen J.-K. Biphasic release of gentamicin from chitosan/fucoidan nanoparticles for pulmonary delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 138, 114–122. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamble M. S.; Mane O. R.; Borwandkar V. G.; Mane S. S.; Chaudhari P. D. Formulation and Evaluation of Clindamycin HCL-Chitosan Microspheres for Dry Powder Inhaler Formulation. Drug Invent. Today 2012, 4, 527. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Lu Z.; Zhu X.; Wang X.; Liao Y.; Ma Z.; Li F. NIR photothermal therapy using polyaniline nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 9584–9592. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Y.; Yang Y.; Poojari Y.; Liu Y.; Wu J.-C.; Hansford D. J.; Epstein A. J. Sulfonated polyaniline-based organic electrodes for controlled electrical stimulation of human osteosarcoma cells. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1727–1731. 10.1021/bm301221t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar P. K.; Raj S.; Anuradha P. R.; Sawant S. N.; Doble M. Biocompatibility studies on polyaniline and polyaniline–silver nanoparticle coated polyurethane composite. Colloids Surf., B 2011, 86, 146–153. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana S.; Ahmad N.; Faisal S. M.; Owais M.; Sabir S. Synthesis, characterisation and potential applications of polyaniline/chitosan-Ag-nano-biocomposite. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 835–842. 10.1049/iet-nbt.2016.0215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawadi S.; Katuwal S.; Gupta A.; Lamichhane U.; Thapa R.; Jaisi S.; Lamichhane G.; Bhattarai D. P.; Parajuli N. Current Research on Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6687290. 10.1155/2021/6687290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. S. O.; Ng S. C.; Sim W. S. Thermal analysis of conducting polymers: Part II. Thermal characterization of electroactive copolymers from aniline and anthranilic acid. Thermochim. Acta 1992, 197, 349–355. 10.1016/0040-6031(92)85034-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Wiederhold N. P.; Williams R. O. III Drug delivery strategies for improved azole antifungal action. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2008, 5, 1199–1216. 10.1517/17425240802457188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R.; Ahmad Z.; Sharma S.; Khuller G. K. Nano-encapsulation of azole antifungals: potential applications to improve oral drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 301, 268–276. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani M. S.; Kazi M.; Alsenaidy M. A.; Ahmad M. Z. Advances in oral drug delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 62. 10.3389/fphar.2021.618411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar O.; Deshpande N.; Dagade S.; Waghmode S.; Nigam Joshi P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from purple acid phosphatase apoenzyme isolated from a new source Limonia acidissima. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2016, 11, 28–37. 10.1080/17458080.2015.1025300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Jiang F.; Lu A.; Zhang G. Linkers Having a Crucial Role in Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 561–561. 10.3390/ijms17040561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalwa H. S.; Mukai J. Effect of the .pi.-bonding sequence on third-order optical nonlinearity evaluated by ab initio calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 10766–10774. 10.1021/j100027a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller F.; Van Koten G.; Vrieze K.; Heijdenrijk D.; Krijnen B. B.; Stam C. H. Reactions of dinuclear metal carbonyl .alpha.-diimine complexes with alkynes. Part 3. Reversible C-N bond formation and fission between an .alpha.-diimine ligand and a methyl propynoate molecule on a dinuclear iron carbonyl moiety. X-ray crystal structures of Fe2(CO)6{(i-Pr)NC(H)C(H)N(i-Pr)C(H)CC(O)OMe} and Fe2(CO)4{(i-Pr)NC(H)C(H)N(i-Pr)C(H)CC(O)OMe}. Organometallics 1989, 8, 41–48. 10.1021/om00103a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller F.; van Koten G.; Polm L. H.; Vrieze K.; Zoutberg M. C.; Heijdenrijk D.; Kragten E.; Stam C. H. Flyover bridge formation via a reversible C-C coupling in reactions of diruthenium pyridine-2-carbaldimine complexes with alkynes. Organometallics 1989, 8, 1340–1349. 10.1021/om00107a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burk M. J.; Crabtree R. H.; Parnell C. P.; Uriarte R. J. Selective stoichiometric and catalytic carbon-hydrogen bond cleavage reactions in hydrocarbons by iridium complexes. Organometallics 1984, 3, 816–817. 10.1021/om00083a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton F. A.; Duraj S. A.; Roth W. J. A new double bond metathesis reaction: conversion of an niobium:niobium and an nitrogen:nitrogen bond into two niobium:nitrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4749–4751. 10.1021/ja00329a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimniak A.; Zachara J. Structural studies of bis(μ2-acetophenoniminato)-bis(tricarbonyliron) by NMR and X-ray diffraction: deviations from symmetry in anti and syn isomers. J. Organomet. Chem. 1997, 533, 45–50. 10.1016/S0022-328X(96)06842-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zare E. N.; Makvandi P.; Ashtari B.; Rossi F.; Motahari A.; Perale G. Progress in Conductive Polyaniline-Based Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications: A Review. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 1. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari M.; Chauhan N. P. S.. Fundamentals and emerging applications of polyaniline; Elsevier, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sami El-banna F.; Mahfouz M. E.; Leporatti S.; El-Kemary M.; AN Hanafy N. Chitosan as a natural copolymer with unique properties for the development of hydrogels. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2193. 10.3390/app9112193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayad M. M.; Amer W. A.; Kotp M. G.; Minisy I. M.; Rehab A. F.; Kopecký D.; Fitl P. Synthesis of silver-anchored polyaniline–chitosan magnetic nanocomposite: a smart system for catalysis. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 18553–18560. 10.1039/C7RA02575K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melad O.; Esleem M. Copolymers of Aniline with O-Anthranilic Acid: synthesis and characterization. Open J. Org. Polym. Mater. 2015, 05, 31. 10.4236/ojopm.2015.52003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I.; Williams D.. Spectroscopic methods in organic chemistry; Springer Nature, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Prokeš J.; Trchová M.; Hlavatá D.; Stejskal J. Conductivity ageing in temperature-cycled polyaniline. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 78, 393–401. 10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00193-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Jiang P.; Liu D. F.; Yuan H. J.; Yan X. Q.; Zhou Z. P.; Wang J. X.; Song L.; Liu L. F.; Zhou W. Y.; Wang G.; Wang C. Y.; Xie S. S.; Zhang J. M.; Shen D. Y. Evidence for the monolayer assembly of poly(vinylpyrrolidone) on the surfaces of silver nanowires. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 12877–12881. 10.1021/jp037116c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Liu Y.; Lu C.; Hou W.; Zhu J.-J. One-step synthesis of AgCl/polyaniline core–shell composites with enhanced electroactivity. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 3578. 10.1088/0957-4484/17/14/037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash S.; Murthy P. N.; Nath L.; Chowdhury P. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2010, 67, 217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vithiya K.; Kumar R.; Sen S. Antimicrobial activity of biosynthesized silver oxide nanoparticles. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 3263–3268. [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q.; Shan S.; Jiang L.; Wang Y.; Li D. Synergistic antimicrobial effects of polyaniline combined with silver nanoparticles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 3560–3566. 10.1002/app.36257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenkopf T. A.; Harrington J. A.; Koble C. S.; Bankston D. D.; Morrison R. W. Jr.; Bigham E. C.; Styles V. L.; Spector T. 2-Acetylpyridine thiocarbonohydrazones. Potent inactivators of herpes simplex virus ribonucleotide reductase. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 2306–2314. 10.1021/jm00090a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin N.; Elbarbary A. A.; Alkabes H. A. Antibacterial and anticancer activity of loaded quinazolinone polypyrrole/chitosan silver chloride nanocomposite. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2017, 66, 307–316. 10.1080/00914037.2016.1201831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Zhi W.-x.; Yan B.; Xu X.-x. α-Fe2O3/PPy/Ag functional hybrid nanomaterials with core/shell structure: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity. Powder Technol. 2012, 221, 177–182. 10.1016/j.powtec.2011.12.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou M.-S.; Li H.-Y. Equilibrium and kinetic modeling of adsorption of reactive dye on cross-linked chitosan beads. J. Hazard. Mater. 2002, 93, 233–248. 10.1016/S0304-3894(02)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelwahab M.; Salahuddin N.; Gaber M.; Mousa M. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)/polyethylene glycol-NiO nanocomposite for NOR delivery: Antibacterial activity and cytotoxic effect against cancer cell lines. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 717–727. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appani R.; Bhukya B.; Gangarapu K. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of 3-(Substituted)-2-(4-oxo-2-phenylquinazolin-3(4H)-ylamino)quinazolin-4(3H)-one. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 1249201. 10.1155/2016/1249201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubie S.; Rajeshkumar R.; Yellareddy B.; Siddhartha G.; Sandeep M.; Surendrareddy K.; Dushyanth H. S.; Elango K. Microwave assisted synthesis of some novel benzimidazole substituted Fluoroquinolones and their antimicrobial evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2010, 2, 69. [Google Scholar]