Abstract

Background & aims

Mexico has one of the highest mortality rates by COVID-19 worldwide. This may be partially explained by the high prevalence of overweight/obesity found in general population; however, there is limited information in this regard. Furthermore, acute kidney injury (AKI) and need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) associated to obesity in patients with COVID-19 are still topics of discussion. Aim: To explore the association of obesity, particularly morbid obesity, with mortality and kidney outcomes in a Mexican population of hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of 773 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a tertiary-care teaching hospital in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Baseline body mass index was classified as: normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), obesity (30–39.9 kg/m2), and morbid obesity (≥40 kg/m2). AKI was diagnosed according to KDIGO clinical practice guidelines.

Results

At baseline, 35% of patients had overweight, 39% obesity and 8% morbid obesity. Patients with obesity were younger, more frequently women and with hypertension than normal weight and overweight patients. Frequency of complications in the univariate analysis were not significantly associated to obesity, however in the multivariate analysis (after adjusting for baseline clinical and biochemical differences), morbid obesity was significantly associated to an increased risk of AKI [OR = 2.70 (1.01–7.26), p = 0.05], RRT [OR = 14.4 (1.46–42), p = 0.02], and mortality [OR = 3.54 (1.46–8.55), p = 0.005].

Conclusions

Almost half of the sample had obesity and morbid obesity. Morbid obesity was significantly associated to an increased risk of AKI, RRT and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Mortality, COVID-19, Morbid obesity

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China. The whole genome sequence was isolated on January 9, 2020 and was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The rapid spread of the virus, produced the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare, by March 11, 2020 a worldwide pandemic [2]; up to April 28, 2021 SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in over 149 million subjects and caused over three million deaths worldwide, a mortality rate of two percent which varies between countries. Mexico is the 15th country with most cases (more than two-million) and third in deaths with >215 thousands, which means a mortality rate of nine percent [3]. The latter makes Mexico one of the most hit countries by this pandemic, which may be partially explained by the elevated prevalence of risk factors, particularly overweight and obesity found in this country (75% among adult population) [4]. Obesity has been implicated as a risk factor for increased positivity testing and severe outcomes in patients with COVID-19 [[5], [6], [7]]; however, its association with COVID-19 mortality has not been completely elucidated [8]. On the other hand, acute kidney injury (AKI) and the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) associated to obesity in patients with COVID-19 remain scarcely explored, and the few reported data are contradictory [9,10]. Moreover, there is no information about whether obesity, and particularly morbid obesity, is associated with AKI in this infectious disease.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the association of obesity, particularly morbid obesity, with mortality and kidney outcomes in a Mexican sample of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. In addition, clinical and biochemical variables, as well as other clinical outcomes, were compared according to the presence of obesity.

2. Methods

All adult patients (>18 years), who fulfilled the selection criteria and were hospitalized during the first wave of COVID-19 in the Mexican state of Jalisco, were included in this retrospective cohort study. Patients were admitted to a tertiary-care teaching hospital [Hospital de Especialidades, Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS)], with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with the Berlin protocol from March 25, 2020 (first case admitted), to September 7, 2020 (date in which the hospital stopped to be exclusively a COVID-19 center). End of the study was November 07, 2020. Our institution was one of the three hospitals converted to treat patients with COVID-19 in the IMSS in our state. All patients were screened, managed, and hospitalized according to the WHO Interim Guidance for COVID-19 [11]. Sociodemographic, clinical, anthropometric, treatment, and outcome variables were collected from electronic medical records throughout the study. Body weight and height at admission were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) and classify patients according to the presence of overweight and obesity. Patients with BMI <18.5 kg/m2, previous chronic renal failure or incomplete anthropometric data were excluded. Laboratory data were collected from the Central Laboratory electronic record of our hospital, and included: complete blood cell count by impedance (XN-2000, Sysmex), and blood chemistry, electrolytes, and kidney function tests by dry chemistry in a VITROS™ 5600 Chemistry System, Ortho Clinical Diagnostics. Myocardial enzymes and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured by enzymatic colorimetric method in a VITROS™ 4600 Chemistry System, Ortho Clinical Diagnostics. Ferritin was measured by chemiluminescence in an automated analyzer LIAISON™, DiaSorin Molecular; whereas D-dimer, was measured in an immunoanalyzer VIDAS™ bioMérieux by Enzyme Linked Fluorescent Assay. Biochemical variables were analyzed comparing values at admission and the last measurement before hospital discharge. This protocol was approved by the local ethics and research committees (Comité Local de Ética en Investigación 13018 and Comité Local de Investigación en Salud 1301, Hospital de Especialidades, Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente, IMSS) with the registration number R-2020-1301-151.

Definitions. Secondary infection was diagnosed when patients showed clinical symptoms or signs of pneumonia or bacteremia, and a positive culture of a new pathogen was obtained from lower respiratory tract specimens or blood samples after admission [12,13]. AKI was diagnosed according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines [14], and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was diagnosed according to the Berlin Definition [15]. The illness severity was defined according to the quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score [16]. Classification of body weight was made according to the OMS recommendation [17] as: normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), obesity (30–39.9 kg/m2), and morbid obesity (≥40 kg/m2).

Statistical analysis. Data analysis was performed in SPSS v. 25. Quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) and nominal ones as n (%). One-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis or χ2 tests were used to compare differences between body weight groups, as appropriate. A Pearson correlation analysis was performed between BMI and clinical and biochemical variables. A logistic regression analysis was performed to analyze mortality and renal outcomes according to the presence of obesity, in which significant baseline differences were used to adjust the analysis. A two-sided p < 0.05 value was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

One-thousand and ten patients were hospitalized during the study period; from these, 237 patients were excluded: 138 did not have anthropometric data, 88 had previous chronic kidney disease and 11 had a BMI <18.5 kg/m2. Thus, 773 were finally analyzed.

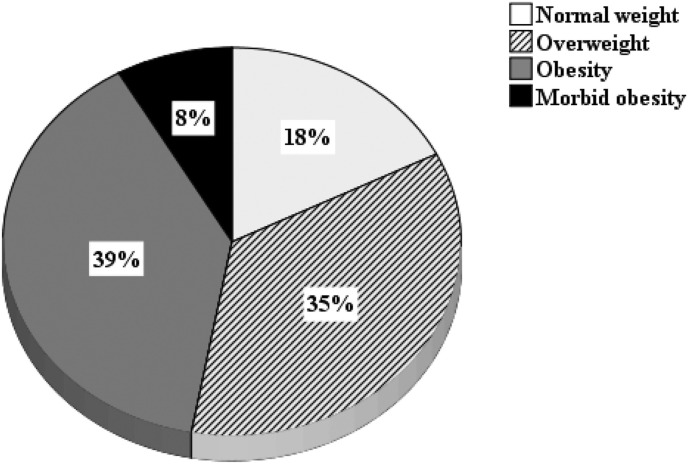

Mean BMI of the whole sample was 30.9 ± 6.4 kg/m2. At baseline, almost half the studied sample had obesity; from this, morbid obesity was present in 8% (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of body mass index in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

Baseline clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients according to the presence of overweight and obesity are shown in Table 1 . Patients with obesity and morbid obesity were significantly younger, were more frequently women, and had higher frequency of hypertension, whereas only those with morbid obesity had higher respiratory rate than the other groups. No differences were found in other demographic and clinical variables.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics according to the presence of obesity in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

| Variable | Normal weight | Overweight | Obesity | Morbid obesity | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 121 | 279 | 307 | 66 | |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 15 | 59 ± 14 | 56 ± 13∗ | 50 ± 12∗+£ | <0.0001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 80 (66) | 193 (69) | 183 (60) | 29 (44) | 0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 13 (30) | 19 (26) | 25 (32) | 10 (56) | 0.13 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Pulmonary disease | 10 (8) | 20 (7) | 26 (8) | 7 (11) | 0.82 |

| Diabetes | 48 (40) | 93 (33) | 129 (42) | 23 (35) | 0.16 |

| Hypertension | 51 (42) | 111 (40) | 164 (53) | 43 (65) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 (7) | 20 (7) | 21 (7) | 5 (8) | 0.99 |

| qSOFA, n (%) | 0.18 | ||||

| 0 | 39 (32) | 92 (33) | 90 (29) | 16 (24) | |

| 1 | 58 (48) | 156 (56) | 181 (59) | 41 (62) | |

| 2 | 24 (20) | 28 (10) | 30 (10) | 7 (11) | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Temperature (°C) | 37 ± 0.81 | 37 ± 0.70 | 37 ± 0.79 | 37 ± 0.73 | 0.57 |

| Pulse oximetry (%) | 86 ± 10 | 84 ± 12 | 84 ± 12 | 84 ± 14 | 0.63 |

| Cardiac rate (× min) | 96 ± 20 | 95 ± 17 | 97 ± 18 | 96 ± 15 | 0.46 |

| Respiratory rate (× min) | 23 ± 5 | 23 ± 5 | 23 ± 4 | 25 ± 6∗+£ | 0.02 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 126 ± 18 | 125 ± 20 | 128 ± 21 | 126 ± 24 | 0.18 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76 ± 11 | 76 ± 12 | 78 ± 12 | 76 ± 13 | 0.14 |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure. ∗p < 0.05 vs normal weight; +p < 0.05 vs overweight; £p < 0.05 vs obesity.

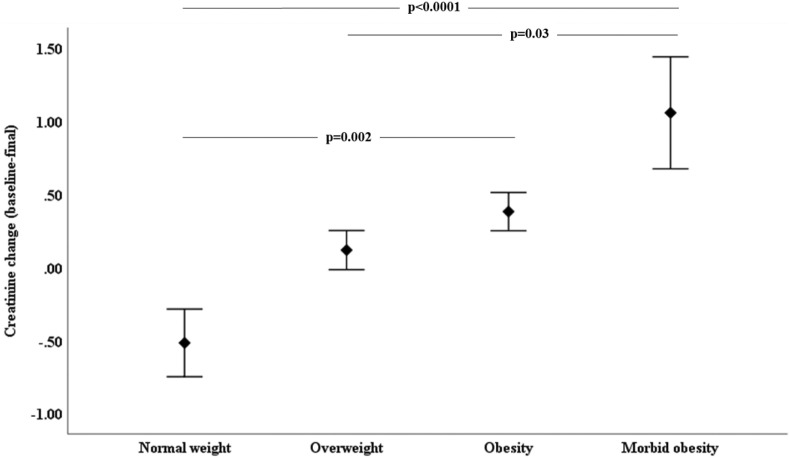

Biochemical characteristics at baseline and delta (final – baseline) evaluations, according to the presence of obesity, are shown in Table 2 . At baseline, patients with normal weight had lower hemoglobin concentrations than the other groups; patients with obesity and morbid obesity had higher lymphocytes compared to normal and overweight groups, whereas ferritin concentrations were lower in patients with morbid obesity compared to the other groups. Patients with obesity and morbid obesity displayed a non-significant trend to have lower D-dimer concentrations than the normal weight and overweight groups. At final evaluation, only serum concentrations of creatinine significantly increased in the groups with obesity and morbid obesity compared to the normal weight group (Fig. 2 ). No other differences were observed at baseline and final biochemical results.

Table 2.

Biochemical results at baseline and delta (final-baseline) evaluations, according to the presence of obesity, in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

| Variable | Normal weight | Overweight | Obesity | Morbid obesity | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | B | 13.7 (12.1–15.2) | 14.3 (12.9–15.5)∗ | 14.4 (13.2–15.5)∗ | 14.2 (13.4–15.1)∗ | 0.03 |

| Δ | −0.01 ± 1.82 | −1.14 ± 2.54 | −1.19 ± 2.17 | −1.65 ± 2.17 | 0.35 | |

| Leucocytes (x 109/L) | B | 8.6 (6.2–12.8) | 9.3 (6.8–13.5) | 9.5 (7.3–13.4) | 8.0 (6.3–14.6) | 0.16 |

| Δ | 1.27 ± 6.90 | 1.26 ± 8.83 | 0.70 ± 7.76 | 2.02 ± 7.77 | 0.66 | |

| Lymphocytes (x 109/L) | B | 0.72 (0.52–1.01) | 0.84 (0.59–1.22) | 1.08 (0.76–1.50)∗+ | 0.97 (0.66–1.46)∗+ | <0.0001 |

| Δ | 0.22 ± 0.72 | 0.18 ± 0.85 | 0.13 ± 1.13 | 0.17 ± 1.68 | 0.89 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | B | 130 (102–220) | 140 (110–197) | 137 (109–223) | 141 (115–217) | 0.58 |

| Δ | −45 ± 139 | −48 ± 101 | −43 ± 111 | −47 ± 91 | 0.97 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | B | 0.73 (0.59–1.09) | 0.76 (0.61–0.98) | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.71 (0.56–0.99) | 0.51 |

| Δ | −0.52 ± 2.52 | 0.12 ± 2.01 | 0.38 ± 2.12∗ | 1.06 ± 2.79∗ | <0.0001 | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | B | 171 (74–256) | 173 (84–270) | 143 (64–247) | 155 (51–240) | 0.17 |

| Δ | −62 ± 182 | −83 ± 176 | −78 ± 131 | 36 ± 167 | 0.45 | |

| Ferritin (μg/L) | B | 825 (469–1457) | 993 (538–1580) | 818 (455–1443) | 539 (198–1227)∗+ £ | 0.003 |

| Δ | −143 ± 622 | −62 ± 798 | 185 ± 1990 | 65 ± 625 | 0.56 | |

| D-dimer (ng/L) | B | 832 (409–1921) | 825 (371–1631) | 688 (340–1530) | 552 (304–1205) | 0.07 |

| Δ | −781 ± 3865 | −530 ± 5583 | −609 ± 6640 | 113 ± 2302 | 0.89 | |

| Cardiac Troponin I (ng/dL) | B | 15.3 (4.1–36.8) | 11.7 (3.4–25.0) | 10.1 (2.7–25.2) | 7.8 (2.3–29.6) | 0.41 |

| Δ | 296 ± 1795 | −40 ± 353 | −337 ± 2238 | 129 ± 490 | 0.58 | |

∗p < 0.05 vs normal weight; +p < 0.05 vs overweight; £p < 0.05 vs obesity.

Fig. 2.

Creatinine change from baseline to final evaluation according to the presence of obesity in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

BMI has a positive correlation with respiratory rate, serum lymphocytes, hemoglobin, at admission, as well as with cardiac rate, lymphocytes and creatinine at discharge, wheras it was negatively correlated with D-dimer at admission (Supplementary Table 1).

Hospital stay length, presence of complications and mortality during hospitalization were not different between groups, except for the need of RRT, which was more common in patients with obesity and morbid obesity compared to the normal weight and overweight groups (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Results of hospital stay and presence of complications during hospitalization according to the presence of obesity in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

| Variable | Normal weight | Overweight | Obesity | Morbid obesity | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital stay length (days) | 11 (6–26) | 11 (6–16) | 10 (7–16) | 9 (6–16) | 0.93 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 24 (20) | 63 (23) | 79 (26) | 16 (24) | 0.59 |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 81 (67) | 180 (64) | 206 (67) | 50 (76) | 0.38 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 32 (26) | 80 (29) | 99 (32) | 25 (38) | 0.32 |

| Septicemia, n (%) | 20 (16) | 33 (12) | 52 (17) | 13 (20) | 0.22 |

| Secondary infection, n (%) | 14 (12) | 28 (10) | 28 (9) | 8 (12) | 0.82 |

| Coagulopathy, n (%) | 8 (7) | 7 (2) | 12 (4) | 3 (4) | 0.27 |

| CV complication, n (%) | 3 (2) | 19 (7) | 14 (5) | 3 (4) | 0.30 |

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 20 (16) | 55 (20) | 69 (22) | 16 (24) | 0.49 |

| RRT, n (%) | 1 (1) | 7 (2) | 19 (6) | 6 (9) | 0.007 |

| Type of RRT, n (%) | 0.68 | ||||

| Hemodialysis | 1 (100) | 5 (72) | 13 (68) | 6 (100) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0 | 1 (14) | 1 (5) | 0 | |

| CRRT | 0 | 1 (14) | 5 (26) | 0 | |

| Death, n (%) | 46 (38) | 95 (34) | 108 (35) | 28 (42) | 0.55 |

ICU: intensive care unit; CV: cardiovascular; RRT: renal replacement therapy; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy.

In the multivariate analysis (Table 4 ), after adjusting for baseline clinical and biochemical differences, morbid obesity was a significant predictor for AKI, need for RRT, and mortality; morbid obesity was also a significant predictor for respiratory failure.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for clinical outcomes according to the presence of obesity in COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

| Variable | Un-adjusted Model |

Adjusted Model∗ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Mortality | ||||

| Normal weight | – | – | – | – |

| Overweight | 0.84 (0.54–1.30) | 0.43 | 1.18 (0.66–2.10) | 0.58 |

| Obesity | 0.87 (0.56–1.34) | 0.52 | 1.53 (0.83–2.79) | 0.17 |

| Morbid obesity | 1.20 (0.65–2.21) | 0.56 | 3.54 (1.46–8.55) | 0.005 |

| Acute kidney injury | ||||

| Normal weight | – | – | – | – |

| Overweight | 1.26 (0.72–2.21) | 0.42 | 1.27 (0.65–2.47) | 0.49 |

| Obesity | 1.44 (0.83–2.49) | 0.19 | 1.85 (0.93–3.67) | 0.08 |

| Morbid obesity | 1.61 (0.77–3.39) | 0.20 | 2.70 (1.01–7.26) | 0.05 |

| Renal replacement therapy | ||||

| Normal weight | – | – | – | – |

| Overweight | 3.08 (0.37–25) | 0.30 | 2.18 (0.25–19.2) | 0.48 |

| Obesity | 7.81 (1.03–59) | 0.05 | 6.31 (0.78–51.1) | 0.08 |

| Morbid obesity | 12 (1.41–102) | 0.02 | 14.4 (1.46–142) | 0.02 |

| Respiratory failure | ||||

| Normal weight | – | – | – | – |

| Overweight | 0.89 (0.57–1.39) | 0.61 | 0.87 (0.49–1.55) | 0.65 |

| Obesity | 0.97 (0.62–1.51) | 0.89 | 1.33 (0.73–2.41) | 0.35 |

| Morbid obesity | 1.54 (0.78–3.04) | 0.21 | 2.91 (1.14–7.48) | 0.03 |

∗ Adjusted by: age, sex, presence of hypertension, qSOFA, hospital stay length, serum hemoglobin, lymphocytes, and ferritin.

4. Discussion

The current study found a high proportion of patients with overweight (35%) and obesity (47%) among those hospitalized by COVID-19. Reported prevalence of obesity in different meta-analysis was 31%–34% [[18], [19], [20]], far below the observed in the current study. Our data support evidence of previous observations from Mexico reporting an obesity prevalence between 39.7% and 55.4% in patients with COVID-19 [[21], [22], [23]]. This is consistent with the fact that Mexico is second in the world in terms of obesity prevalence [24]: 75% of adult population suffering overweight/obesity [4].

Many studies have shown an increased risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19 and obesity [[25], [26], [27], [28]]; however, few have specifically analyzed if this issue displays a dose–response effect [18]. Our study shows, that after adjusting for some important variables, the most severe grade of obesity significantly predicts higher mortality. In settings like ours, with higher prevalence of obesity in general population [24] and in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 than other countries [[18], [19], [20]], the highest BMI was more clearly associated with increased mortality. Multiple mechanisms have been suggested to explain the association of obesity with mortality in COVID-19 patients, as association with low-grade chronic inflammatory status, higher expression of angiotensin converting enzyme binding system of SARS-CoV-2, and coexistence with other comorbidities [29].

On the other hand, AKI is one of the main complications in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 and is associated with increased mortality [30,31]. Implications of obesity for development of AKI in patients with COVID-19 have been controversial [[8], [9], [10],23,26]; however, our results support the notion of a direct association, as patients with obesity and morbid obesity significantly increased serum creatinine concentrations at the end of the follow-up, compared to patients with overweight and normal weight. Moreover, those with the most severe obesity had increased risk for AKI and use of RRT in the multivariate analysis. Possible reasons of controversial results in previous studies could have been a lack of analysis by grades of obesity and exclusion of patients with previous diagnosis of chronic kidney disease, variables that were controlled in the present study. Obesity may increase the risk of AKI by several mechanisms not completely understood; however, dysregulation of fatty acids and carbohydrate metabolism, presence of comorbidities, oxidative stress and inflammation are likely the most important factors possibly associated to kidney injury [32]. In critically ill non-COVID-19 patients with AKI, obesity has shown a dual effect, and an “obesity survival paradox” has been proposed; nonetheless, it seems that negative outcomes associated with obesity are more relevant than the positive ones [32].

In the current study, morbid obesity also predicted the development of respiratory failure, which is in agreement with the recognized presence of an obesity associated restrictive pulmonary function, characterized by increased respiratory rate and mild hypoxia secondary to ventilation-perfusion desynchronization [33,34].

Finally, biochemical markers associated with inflammation were, unexpectedly, lower in patients with obesity and morbid obesity. Ferritin concentrations were significantly lower, and C-reactive protein and D-dimer had a non-significant trend to have lower levels in patients with obesity. These latter findings deserve further investigation, but they could be associated to the so-called “obesity paradox” [32,35,36], in which the obesity-associated chronic inflammation may elicit an immune system strong response, which in turn, could help to recover faster from an infection.

Strengths and limitations. Our findings may help to understand the impact of obesity on mortality and kidney outcomes in hospitalized patients by COVID-19 as the current sample has a vast number of subjects exposed to this risk factor. Notwithstanding, the retrospective nature of the study and the characteristics of this single center population may limit validity.

In terms of kidney outcomes, patients with known chronic kidney disease were excluded from the study, in order to evaluate the association of obesity with AKI instead of the association with chronic damage. Additionally, it is important to note the possible bias in these results as a drug treatment analysis was not possible to perform.

5. Conclusions

Prevalence of obesity and morbid obesity was very high in these hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19. Morbid obesity was significantly associated with an increased risk of AKI, use of RRT and mortality.

Funding statement

Authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author's Contribution

FMC, AMCM, conceived the research idea, ERC, LCS, MCEB, SOHG, AHNZ, CFO, LMABP, AGO, and MMR made data curation and defined methodology of the protocol, FMC, NRC and ALVV perform data analysis, FMC, NRC and AMCM wrote the manuscript with support of ERC and ALVV. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.08.027.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Situation report.https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/who-advice-for-international-travel-and-trade-in-relation-to-the-outbreak-of-pneumonia-caused-by-a-new-coronavirus-in-china/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . 2020. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19.https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Internet] [cited 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johns Hopkins University . 2021. COVID-19 dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Internet] [cited 2021 Apr 29]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamah-Levy T., Rivera-Dommarco J., Bertozzi S., Encuesta Nacional de Salud y. Nutrición 2018-19: análisis de sus principales resultados. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;62(6):614–617. doi: 10.21149/12280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen R.A.G., Sturrock S.L., Arneja J., Brooks J.D. Measures of adiposity and risk of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the UK biobank study. J Obes. 2021;2021:8837319. doi: 10.1155/2021/8837319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Sacco V., Rauch B., Gar C., Haschka S., Potzel A.L., Kern-Matschilles S. Overweight/obesity as the potentially most important lifestyle factor associated with signs of pneumonia in COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almyroudi M.P., Dimopoulos G., Halvatsiotis P. The role of diabetes mellitus and obesity in COVID 19 patients. Pneumon. 2020;33(3):114–117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakeshbandi M., Maini R., Daniel P., Rosengarten S., Parmar P., Wilson C. The impact of obesity on COVID-19 complications: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Obes. 2020;44(9):1832–1837. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0648-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch J.S., Ng J.H., Ross D.W., Sharma P., Shah H.H., Barnett R.L. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;6(98):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng J.H., Hirsch J.S., Hazzan A., Wanchoo R., Shah H.H., Malieckal D.A. Outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(2):204–215. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Interim Guidance (WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.5); 2020. Clinical management of COVID-19.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalil A.C., Metersky M.L., Klompas M., Muscedere J., Sweeney D.A., Palmer L.B. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61–e111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dugar S., Choudhary C., Duggal A. Sepsis and septic shock: guideline-based management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87:53–64. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.18143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., Thompson B.T., Ferguson N.D., Caldwell E., Fan E. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seymour C.W., Liu V.X., Iwashyna T.J., Brunkhorst F.M., Rea T.D., Scherag A. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315:762–774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pranata R., Lim M.A., Yonas E., Vania R., Lukito A.A., Siswanto B.B. Body mass index and outcome in patients with COVID-19: a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2021;47(2):101178. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik P., Patel U., Patel K., Martin M., Shah C., Mehta D. Obesity a predictor of outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalized patients-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1188–1193. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu J., Wang Y. The clinical characteristics and risk factors of severe COVID-19. Gerontology. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000513400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortiz-Brizuela E., Villanueva-Reza M., González-Lara M.F., Tamez-Torres K.M., Román-Montes C.M., Díaz-Mejía B.A. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in a tertiary care center in Mexico City: a cohort prospective study. Rev Invest Clin. 2020;72(4):252–258. doi: 10.24875/RIC.20000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruíz-Quiñonez J.A., Guzmán-Priego C.G., Nolasco-Rosales G.A., Tovilla-Zarate C.A., Flores-Barrientos O.I., Narváez-Osorio V. Features of patients that died for COVID-19 in a hospital in the south of Mexico: a observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casas-Aparicio G.A., León-Rodríguez I., Alvarado-de la Barrera C., González-Navarro M., Peralta-Prado A.B., Luna-Villalobos Y. Acute kidney injury in patients with severe COVID-19 in Mexico. PloS One. 2021;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):288–298. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popkin B.M., Du S., Green W.D., Beck M.A., Algaith T., Herbst C.H. Individuals with obesity and COVID-19: a global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obes Rev. 2020;21(11) doi: 10.1111/obr.13128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowe B., Cai M., Xie Y., Gibson A.K., Maddukuri G., Al-Aly Z. Acute kidney injury in a national cohort of hospitalized US Veterans with COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;16(1):14–25. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09610620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chand S., Kapoor S., Orsi D., Fazzari M.J., Tanner T.G., Umeh G.C. COVID-19-Associated critical illness-report of the first 300 patients admitted to intensive care units at a New York City medical center. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35(10):963–970. doi: 10.1177/0885066620946692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kammar-García A., Vidal-Mayo J.J., Vera-Zertuche J.M., Lazcano-Hernández M., Vera-López O., Segura-Badilla O. Impact of comorbidities in Mexican SARS-CoV-2-positive patients: a retrospective analysis in a national cohort. Rev Invest Clin. 2020;72(3):151–158. doi: 10.24875/RIC.20000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammad S., Aziz R., Al Mahri S., Malik S.S., Haji E., Khan A.H. Obesity and COVID-19: what makes obese host so vulnerable? Immun Ageing. 2021;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12979-020-00212-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu E.L., Janse R.J., de Jong Y., van der Endt V.H.W., Milders J., van der Willik E.M. Acute kidney injury and kidney replacement therapy in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(4):550–563. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X., Jin Y., Li R., Zhang Z., Sun R., Chen D. Prevalence and impact of acute renal impairment on COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):356. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiffl H., Lang S.M. Obesity, acute kidney injury and outcome of critical illness. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(3):461–466. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biring M.S., Lewis M.I., Liu J.T., Mohsenifar Z. Pulmonary physiologic changes of morbid obesity. Am J Med Sci. 1999;318:293–297. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trayhurn P. Hypoxia and adipose tissue function and dysfunction in obesity. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):1–21. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drechsler C., Wanner C. The obesity paradox and the role of inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(5):1270–1272. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015101116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speakman J.R., Westerterp K.R. Reverse epidemiology, obesity and mortality in chronic kidney disease: modelling mortality expectations using energetics. Blood Purif. 2010;29(2):150–157. doi: 10.1159/000245642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.