Abstract

Background

Decades of research indicate that when social connectedness is threatened, mental health is at risk. However, extant interventions to tackle loneliness have had only modest success, and none have been trialled under conditions of such threat.

Method

174 young people with depression and loneliness were randomised to one of two evidence-based treatments: cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) or Groups 4 Health (G4H), an intervention designed to increase social group belonging. Depression, loneliness, and well-being outcomes were evaluated at one-year follow-up; COVID-19 lockdown restrictions were imposed partway through follow-up assessments. This provided a quasi-experimental test of the utility of each intervention in the presence (lockdown group) and absence (control group) of a threat to social connectedness.

Results

At one-year follow-up, participants in lockdown reported significantly poorer wellbeing than controls who completed follow-up before lockdown, t(152)=2.41, p=.017. Although both CBT and G4H led to symptom improvement, the benefits of G4H were more robust following an unanticipated threat to social connectedness for depression (χ2(16)=31.35, p=.001), loneliness (χ2(8)=21.622, p=.006), and wellbeing (χ2(8)=22.938, p=.003).

Limitations

Because the COVID-19 lockdown was unanticipated, this analysis represents an opportunistic use of available data. As a result, we could not measure the specific impact of restrictions on participants, such as reduced income, degree of isolation, or health-related anxieties.

Conclusions

G4H delivered one year prior to COVID-19 lockdown offered greater protection than CBT against relapse of loneliness and depression symptoms. Implications are discussed with a focus on how these benefits might be extended to other life stressors and transitions.

Keywords: Social isolation, Depression, Well-being, Social identity, Cognitive behaviour therapy, Group memberships

Loneliness has been shown to be causally linked to poor mental health and is a source of significant distress in its own right (Erzen and Çikrikci, 2018; Yu et al., 2015). Recognition of the public health burden that this causes has been growing in recent years, prompting national policy and community initiatives. For example, in the United Kingdom, social prescribing programs have sought to connect people who experience loneliness to social groups in their local communities, typically through primary care providers (Halder et al., 2018; Wakefield et al., 2020). However, evidence for the efficacy of this and other loneliness interventions — whether focused on prevention or treatment — is not strong. Indeed, in their meta-analysis of loneliness interventions, Masi and colleagues (2011) concluded that: “the most we can say is that these interventions achieve, at best, only modest improvement but not recovery”. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis found that interventions rarely target people with chronic loneliness specifically, or examine long-term outcomes (Eccles and Qualter, 2020). This is problematic in light of loneliness being prone to relapse (Cacioppo et al., 2015).

This disconnect between the prevalence of loneliness and our capacity to manage it has been brought into stark relief by the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to reduce the risk of contracting and spreading the disease, many people around the world have experienced extended periods of isolation, either self-imposed or enforced by governments, which, unsurprisingly, have been associated with increased loneliness (Groarke et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2020). Nevertheless, recent evidence suggests that a new intervention, Groups 4 Health (G4H), can be effective in reducing loneliness in vulnerable samples. Across three published trials, this program was found to reduce loneliness compared to a matched no-treatment control group (Haslam et al., 2016), treatment as usual (Haslam et al., 2019), and group cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT; Cruwys et al., 2021) with large effects sizes in each trial.

G4H targets group-based belonging as the key mechanism through which loneliness can be overcome (Haslam et al., 2016, 2019). According to social identity theorising, loneliness is seen to arise from either the loss, or the lack, of important and meaningful group memberships and the social identities that arise from them (Cruwys et al., 2014; Haslam et al., 2018). On this basis it is argued that increasing the number of a person's high-quality group memberships and associated identifications can be an antidote to loneliness and its associated health consequences (Cruwys et al., 2018; Sani et al., 2012).

The social identity framework has paid particular attention to the role that external events, particularly those associated with life transitions, play in shaping loneliness and its sequelae. Speaking to this, the social identity model of identity change (SIMIC; Haslam, et al., 2021) explores the effects that life transitions can have on a person's group memberships and social identities. These transitions can be planned (e.g., pregnancy, retirement; Seymour-Smith et al., 2017; Steffens et al., 2016) or unplanned (e.g., trauma, job loss; Muldoon et al., 2019). Though very different, these events all have a distinct and often profound effect on a person's social environment — resulting in loss or change in the group memberships and identities that they value or are able to draw upon. According to SIMIC, it is these social changes that are fundamental to understanding a person's response to life transitions and their impact on well-being.

However, neither G4H nor other extant loneliness interventions have been evaluated in terms of their capacity to protect people against an unanticipated threat to social connectedness. Given that both life change and social isolation are recognised triggers for loneliness and, indeed, the onset or relapse of mental ill-health, this represents an important gap. To address this, the current study sought to evaluate the capacity of G4H to protect against loneliness and mental health decline in the context of an unanticipated and significant threat to social connectedness — the COVID-19 pandemic and associated government-imposed lockdowns. Here we explored our research question using existing data from a randomised control trial which compared G4H and CBT in a large sample of young Australians (aged 15-25) with a history of loneliness and depression. Approximately half the participants completed their 12-month follow-up assessment prior to mid-February 2020, while the remainder completed it during Australia's first COVID-19 lockdown period (April-June 2020). Restrictions during this period involved a stay-at-home order for all but essential workers and strict limits on movement outside of home (only for essential shopping and health needs). The former functioned as a control group and the latter as a quasi-experimental “lockdown” group.

This sample was particularly suitable for assessing our research question because in Australia, as in many countries, the lockdown measures had a more severe economic and social impact on young people than on other demographic groups (Dawel et al., 2020). There were two reasons for this. First, young people tended to be overrepresented in employment sectors most severely impacted by lockdown restrictions (e.g., retail, hospitality). Second, they were more likely to be employed casually, and emergency government subsidies implemented to support employees excluded most casual workers (ATO, 2020). In addition, our sample were particularly vulnerable to the threat that lockdown posed to social connectedness and mental health because of their history of depression and loneliness, both of which follow a chronic course.

In this context, our research sought to test two hypotheses:

-

H1

The lockdown group would report worse mental health than the control group, as indexed by differences in wellbeing, depression, and loneliness.

-

H2

Participants who completed G4H (vs. CBT) would have greater protection against the threats to social connectedness and mental health posed by lockdown, and report lower loneliness and depression and greater wellbeing at 12-month follow-up.

1. Method

1.1. Participants and design

Participants were 174 people in a Phase 3 randomised controlled trial (described elsewhere, Cruwys et al., 2021) that sought to compare the long-term efficacy of G4H and CBT. In order to meet eligibility criteria for the trial, at baseline, all participants reported elevated levels of loneliness on the UCLA-20 (the minimum required score was 40 which is approximately 1 standard deviation above the population mean for adolescents), clinical symptoms of depression on the PHQ-9 (the minimum required score was 5 which represents mild clinical symptoms), and/or a diagnosed mental illness (28.7% of the sample). Young people were ineligible if they were receiving adjunct evidence-based treatment for depression (e.g., antidepressant medication; evidence-based psychotherapy), or had another severe mental illness that could not be managed appropriately in the group program (e.g., personality disorder, moderate-severe suicide risk). Participants were recruited from public and private mental health services, as well as via advertising in the wider community. Ethical approval was provided by Brisbane Metro South HREC/18/QPAH/54.

Participants were aged 15-25 years (M=19.00; SD=2.01), and were 74% female (see Table 1 for full demographic details). After providing informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to either G4H (n=84) or CBT (n=90). All 174 participants were invited to complete follow-up assessments and included in the analysis, including those who discontinued the group program (n=17) or who became ineligible (e.g., because they commenced other evidence-based treatment; n=3). Only 5 participants did not complete any of the follow-up timepoints. The focal follow-up timepoint for this analysis (12 months) was completed by 159 participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample.

| Demographics | Lockdown group (N=99) | Control group (N=75) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 76 (76.8%) female 23 (23.2%) male |

55 (73.3%) female 20 (26.7%) male |

| Education | 2 (2.0%) Year 10 or less 81 (81.8%) Year 12 9 (9.1%) certificate or diploma 6 (6.1%) Bachelor degree 1 (1.0%) Graduate degree |

7 (9.3%) Year 10 or less 51 (68.0%) Year 12 8 (10.7%) certificate or diploma 9 (12.0%) Bachelor degree |

| Ethnicity | 47 (47.5%) White 49 (49.5%) Asian 1 (1.0%) Indigenous 1 (1.0%) Black 1 (1.0%) Middle Eastern |

32 (43.2%) White 34 (45.9%) Asian 5 (6.7%) Indigenous 2 (2.7%) Black 1 (1.3%) Middle Eastern 1 (1.3%) Not disclosed |

| Formal mental illness diagnosis | 58 (58.6%) No 29 (29.3%) Yes 12 (12.1%) Not disclosed |

48 (64.0%) No 21 (28.0%) Yes 6 (8.0%) Not disclosed |

| Age M (SD) | 18.94 (1.99) | 18.95 (1.93) |

|---|---|---|

| Session Attendance (0-5) | 4.40 (1.22) | 4.45 (1.18) |

| Outcome variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness (UCLA-20) | 52.20 (10.19) | 53.60 (9.57) |

| Depression score (DASS-21) | 19.82 (9.16) | 20.93 (8.93) |

| Wellbeing (SWEMWBS) | 17.94 (2.76) | 17.68 (2.63) |

Note. t-tests (for continuous variables) and chi-square tests (for categorical variables) indicated that no baseline differences between groups were statistically significant (ps > .088).

Participants in both the G4H and CBT conditions completed a five-session group program across eight weeks in small groups of 5-8 participants. Each session was approximately 75 minutes and was fully manualised (G4H: Haslam et al., 2016 ; CBT: Stice et al., 2007). Each group was facilitated by two provisional psychologists, who received a half-day training in the intervention along with weekly supervision by a clinical psychologist.

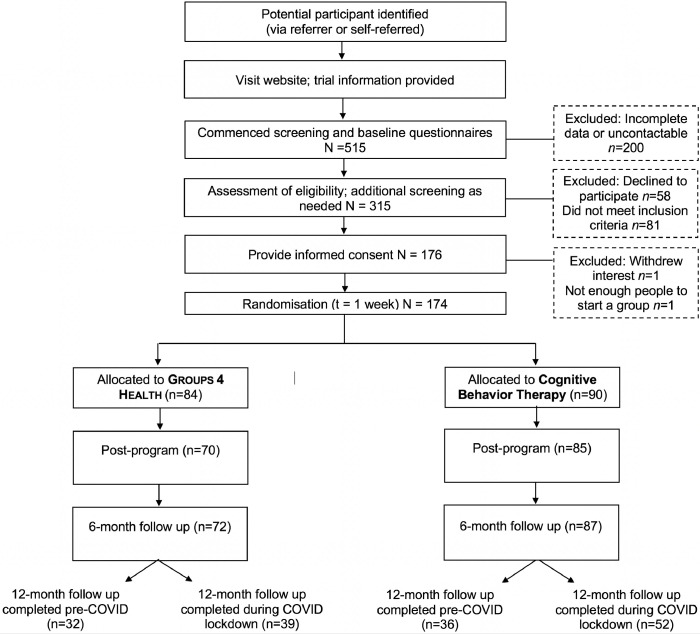

The design of the study is presented in Fig. 1 ; 75 people were due to complete their 12-month follow-up prior to mid-February 2020 (of which 68 responses were obtained), while 99 people were due to complete their 12-month follow-up in April-June 2020 during the period of national government-imposed lockdown (of which 91 responses were obtained). Although the trial was designed for another purpose (a non-inferiority trial), two features made it particularly suitable to answering our research question. First, participants were randomly assigned to either CBT or G4H and the trial had the same (pre-registered) recruitment strategy over time, meaning that participants who were recruited earlier versus later in the trial (and were thus completing their follow-ups in vs. before lockdown) should not differ at baseline except by chance. Second, unlike many threats to social connection, COVID lockdown was not anticipated by participants and therefore we can be confident that their responses to measures collected at the timepoints prior to lockdown should not differ between groups other than by chance. This quasi-experimental design (Reichardt, 2009) allows us to capitalise on these features of the dataset to provide a strong test of the ability of G4H versus CBT to protect vulnerable young people against an unanticipated threat to their social connectedness.

Fig. 1.

The quasi-experimental design of the study.

1.2. Measures

The focal measures for this study were administered at baseline, post-program completion, 6-month follow-up and 12-month follow-up. Additional measures and timepoints are described in full in the trial protocol (Cruwys et al., 2019).

1.2.1. Loneliness

The Revised UCLA-20 item scale (Russell, 1996) was used to assess severity of loneliness in participants. Participants responded to items such as “I feel left out” on a four-point scale from “Never” (1) to “Often” (4). This scale has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measure of loneliness among adolescents (Mahon et al., 1995) and college students (Russell, 1996).

1.2.2. Wellbeing

The Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) was used to measure wellbeing. This seven-item, positively worded scale asked participants to rate the frequency with which they had experienced each state over the past two weeks, with items such as “I've been dealing with problems well” measured on a five-point scale from “None of the time” (1) to “All of the time” (5). Previous studies have provided evidence of this measure's reliability and validity in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Ng Fat et al., 2017). The summed raw scores were transformed into standardised metric scores (Stewart-Brown et al., 2009).

1.2.3. Depression

The seven-item depression subscale of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales short form was used to assess depression symptom severity. Participants rated the degree to which over the past week they had experienced symptoms such as “I felt I wasn't worth much as a person” on a four-point scale from “Did not apply to me at all” (0) to “Applied to me very much, or most of the time” (3). Previous studies have provided evidence of this measure's reliability and validity in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Henry and Crawford, 2005; Page et al., 2007). The summed scores were multiplied by 2 in accordance with recommendations (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995).

1.3. Analysis plan

First, the lockdown and control groups were compared at baseline (chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables) on all outcome and demographic variables to ensure that ‘assignment’ to these groups, which was determined by date of enrolment and, thus, date of scheduled follow-up, was quasi-random in nature. Differences between CBT and G4H at baseline were not evaluated statistically, in line with recommendations that this is inappropriate for RCT designs where any differences must arise due to chance (Assman et al., 2000).

H1, that lockdown participants would have poorer mental health than control participants, was assessed using t-tests comparing these two groups on loneliness, wellbeing, and depression at the 12-month timepoint.

H2, that G4H would be more protective than CBT against the unanticipated threat to social connectedness posed by lockdown, was assessed using three mixed-effects models (one for each of the focal variables of loneliness, wellbeing and depression) in R (using the lme4 package; Bates et al., 2014). Each mixed-effects model included all available data across timepoints. Full information maximisation likelihood (FIML) was used to estimate missing data in accordance with best practice recommendations for RCTs (Jakobsen et al., 2017). Random intercepts were included for participant and therapy group. In Step 1 of the model, fixed effects were included for time (as a categorical variable), condition (G4H vs. CBT), and their interaction. The crucial test was in Step 2, which added fixed effects for the lockdown variable (control vs. lockdown) and its interactions with time and condition variables. ANOVAs comparing Step 1 and Step 2 were used to determine whether the addition of these predictors significantly improved model fit. Where this analysis was significant, planned t-test comparisons were conducted to compare subgroups (using the emmeans R package to preserve the FIML approach and maximise power; Lenth et al., 2020).

2. Results

2.1. Differences at baseline

Lockdown and control groups did not differ significantly on any measured demographic variable: ethnicity, education, gender, age, or session attendance. Furthermore, lockdown and control groups did not differ at baseline on loneliness, depression, or wellbeing.

2.2. Evaluation of H1

Wellbeing was lower on average at follow-up in the lockdown group (M=20.11; SD=3.33) than the control group (M=21.59; SD=4.32), t(152)=2.41, p=.017. Depression symptoms were also marginally higher in the lockdown group (M=13.25; SD=9.34) than the control group (M=10.80; SD=8.30), t(152)=-1.71, p=.089. Loneliness did not differ between the lockdown and control groups at follow-up, t(152)=-.57, p=.571. H1 was therefore partially supported, with evidence that lockdown compromised participants’ wellbeing and marginally increased their symptoms of depression.

2.3. Evaluation of H2

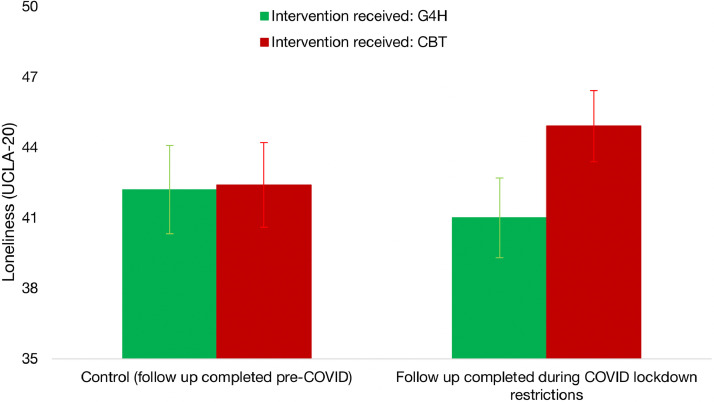

2.3.1. Loneliness

The baseline model (Step 1) against which the effect of COVID lockdown was compared was a mixed-effects model with three levels, including random intercepts for time, participant, and therapy group, as well as fixed effects for time, condition, and their interaction. Step 2 added the lockdown variable as a moderator of all other variables (coded control=0; lockdown=1). The addition of Step 2 significantly improved model fit, χ2(8)=21.622, p=.006, and this was driven by a significant three-way time*condition*lockdown interaction. At baseline, there were no significant differences in loneliness between treatment conditions or lockdown groups. However, at 12-month follow-up, a significant difference emerged such that, under lockdown restrictions only, participants who had received CBT one year earlier were more vulnerable to relapse in loneliness. This three-way interaction was best represented by a quadratic equation, t(469)=-2.668, p=.008. This indicates that the difference between groups was not linear over time. Rather, COVID lockdown was associated with a disruption to participants’ previous improvement trajectories for loneliness in response to treatment. Pairwise comparisons indicated a marginally significant difference between G4H and CBT at the follow-up timepoint (seen in the right-hand side of Fig. 2 ), t(41.5)=-1.73, p=.091.

Fig. 2.

Loneliness as a function of intervention received (G4H vs. CBT) and point of testing (pre-COVID versus during-COVID).

Note. Participants who completed Groups 4 Health were less likely to experience a relapse in loneliness during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions than those who received Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. The estimated marginal means from the mixed-effects model are reported. Error bars represent standard error.

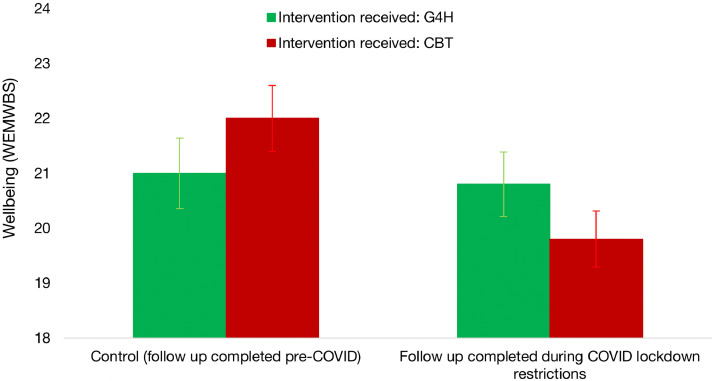

2.3.2. Wellbeing

As with the loneliness analysis, Step 2 added the ‘lockdown’ variable as a moderator. The model comparison was significant, χ2(8)=22.938, p=.003. This was driven by a significant three-way time*condition*lockdown interaction, such that while there were no significant differences in wellbeing between treatment conditions or lockdown group at baseline, at 12-month follow-up, a significant difference emerged whereby the group who had received CBT one year earlier tended to have better wellbeing in the control group than in the lockdown group (see Fig. 3 ). Follow-up analyses indicated a significant difference at follow-up in the CBT condition between the lockdown and the control groups, t(88.8)=2.77, p=.007. By contrast, no difference was found between the lockdown and control groups at follow-up in the G4H condition, t(124.9)=.27, p=.787.

Fig. 3.

Wellbeing as a function of intervention received (G4H vs. CBT) and point of testing (pre-COVID versus during-COVID).

Note. Participants who completed Cognitive Behaviour Therapy and were followed up prior to COVID-19 restrictions reported better wellbeing 12 months later than those followed up during restrictions. There was no effect of lockdown on the wellbeing of Groups 4 Health recipients. The estimated marginal means from the mixed-effects model are reported. Error bars represent standard error.

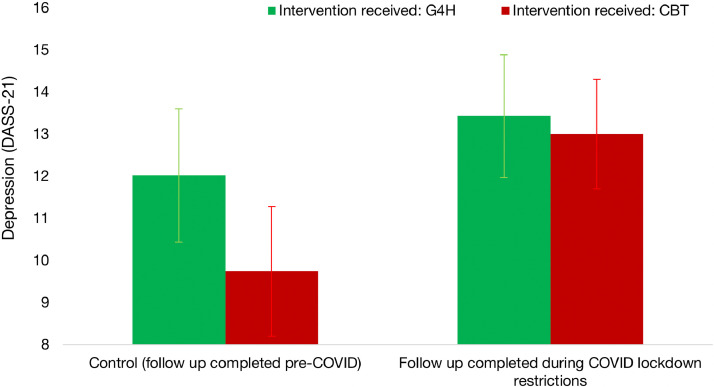

2.3.3. Depression

The addition of Step 2 to the depression model significantly improved fit, χ2(16)=31.35, p=.001. This was driven by a significant three-way time*condition*lockdown interaction, such that while there was no significant difference in depression between treatment conditions or lockdown groups at baseline, at 12-month follow-up, a significant difference emerged whereby under lockdown restrictions only, the group who had received CBT one year earlier was more vulnerable to a relapse in depression. This three-way interaction was best represented by a quadratic equation, t(1078)=-2.822, p=.005. This indicates that the difference between groups did not emerge linearly over time. Instead, the COVID lockdown was associated with a disruption to their previous improvement trajectories for depression in response to treatment. None of the simple comparisons were significant, but the largest difference was between CBT recipients in the control group (M=9.74; SD=1.54) and CBT recipients in the lockdown group (M=13.00; SD=1.30), t(59.3)=-1.612, p=.112, (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Depression as a function of intervention received (G4H vs. CBT) and point of testing (pre-COVID versus during-COVID).

Note. A quadratic interaction indicated that the overall pattern of depression scores at follow-up differed based on intervention received (G4H vs. CBT) and whether follow-up was completed prior to, or during, lockdown. The estimated marginal means from the mixed-effects model are reported. Error bars represent standard error.

3. Discussion

A pandemic and its associated global economic, social, and community effects represent a significant stressor and threat to the wellbeing of the population at large. However, this is especially true for young people with a history of depression and loneliness for whom physical separation and lockdowns can be especially challenging (Dawel et al., 2020). It is thus remarkable that among these young people who had completed G4H one year prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, no significant differences were found between the lockdown and control groups on loneliness, wellbeing, or depression. In the context of G4H recipients showing substantial and sustained improvement in social connectedness and mental health from baseline, this suggests that G4H acted as an ‘inoculation’ for these vulnerable young people against an unanticipated threat to their social connectedness. In contrast, young people who completed the CBT program showed the predicted elevation in loneliness, depression symptoms, and reduced wellbeing during lockdown, relative to control participants who completed their follow-up assessments before lockdown.

Importantly, these findings do not suggest that CBT is ineffective or did not benefit participants. On the contrary, both G4H and CBT proved highly effective at reducing loneliness and depression relative to baseline, which was the key finding of the pre-registered Phase III trial that is reported elsewhere (Cruwys et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the benefits that participants obtained from CBT were less robust to an unanticipated life change of the form brought about by COVID-19 and associated restrictions. It was in this context that G4H was particularly advantageous.

3.1. Implications

These findings speak to the potential utility of G4H as an intervention to ‘inoculate’ people against changes brought about by major life events. For instance, prior work has suggested that wellbeing is often compromised by events such as trauma, brain injury, or migration (Haslam et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2011). Even putatively positive events — such as starting university, becoming a mother, and transitioning to retirement — often threaten wellbeing, with a substantial minority of people struggling to adjust (Cruwys et al., 2020; Lam et al., 2018). Prior research suggests that these difficulties are due, in large part, to the loss and change in the social groups and identities that life transitions entail. For this reason, an intervention that seeks to enhance the skills required to negotiate and manage group life (such as G4H) has particular appeal on both theoretical and practical grounds. Indeed, the current study provides the strongest empirical evidence to date that G4H is uniquely placed to protect people from becoming isolated and unwell in the face of unexpected life challenges.

These findings also highlight the need to conceptualise and evaluate mental health interventions through a lens that considers social and contextual threats to wellbeing. While it is certainly important to promote good mental health in times of ‘smooth sailing’, interventions might also seek to buffer people when ‘life gives you lemons’ — a scenario which, realistically, we will all experience. Rarely have intervention evaluations considered such events — not least because these are largely unplanned and hence difficult to study. However, large national datasets may provide opportunities to examine the effect of major societal events (e.g., Sibley and Bulbulia, 2012), and methods like those employed here could also be used more widely to shed light on the robustness of clinical interventions.

3.2. Strengths and limitations

This study had many strengths: its pre-COVID baseline for all participants, randomisation to intervention group, and the inclusion of a “control” group who completed 12-month follow-up prior to the pandemic restrictions and who were statistically indistinguishable to the lockdown group at baseline. However, there are also a number of limitations. The sample comprised young people, mostly female, and thus the findings are not necessarily generalisable beyond this demographic group. Furthermore, the present analysis represents an opportunistic use of available data. As a result, we do not have measures that quantify the specific impact of restrictions on participants, such as reduced income, degree of isolation, or health-related anxieties. Our lockdown group were all sampled in the earliest phase of the pandemic, when community solidarity tended to be strong (Cárdenas et al., 2021; Reicher and Drury, 2021). Subsequent transmission waves and repeated lockdowns may well have further undermined wellbeing and led to more divergent trajectories. As previous work highlights, it seems likely that COVID-related experiences interact with individual vulnerabilities to influence outcomes (Balestri et al., 2019; Jetten et al., 2020; Moccia et al., 2021), but these were not assessed in the present study.

3.3. Conclusion

We must stop regarding unexpected things as interruptions of real life. The truth is that these are real life. C. S. Lewis

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the crucial role of community in supporting both personal wellbeing and public health. However, the extant evidence base gives limited insight into how best to manage the problem of loneliness that have been exacerbated by the pandemic. G4H is a new approach to intervention that, unlike CBT, focuses on developing skills to strengthen and maintain group-based belonging over the long term. In so doing, the current evidence suggests that it is able not only to improve loneliness and mental health in the short term, but also to provide those who are vulnerable with protection down the track against the unexpected things that provide the harshest “real life” test of their resilience.

Contributors

TC led the grant, oversaw the trial, did the statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the report. CH provided conceptual input at all stages of the grant and project, and led the development of the intervention and the training of facilitators. JR and EW were the trial managers. AH provided conceptual input and led grants that supported program development. All authors provided critical feedback on the report.

Funding

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report or decision to publish.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors TC, CH and AH are the developers of the GROUPS 4 HEALTH program, and The University of Queensland holds its associated Intellectual Property. These authors have an academic, rather than commercial, interest in the program, with training offered at cost and additional funds directed to ongoing program development and evaluation.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by Australian Rotary Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council (#1173270).

References

- Australian Taxation Office Jobkeeper Payment. 2020 [Google Scholar]; https://www.ato.gov.au/general/jobkeeper-payment/. 1 March 2021.

- Assmann S.F., Pocock S.J., Enos L.E., Kasten L.E. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1064–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestri M., Porcelli S., Souery D., Kasper S., Dikeos D., Ferentinos P., Papadimitriou G.N., Rujescu D., Martinotti G., Di Nicola M., Janiri L., Caletti E., Mandolini G.M., Pigoni A., Paoli R.A., Lazzaretti M., Brambilla P., Sala M., Abbiati V.…Serretti A. Temperament and character influence on depression treatment outcome. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;252(August 2018):464–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. 2014;67(1) doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S., Grippo A.J., London S., Goossens L., Cacioppo J.T. Loneliness: clinical Import and Interventions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015;10(2):238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. http://pps.sagepub.com/content/10/2/238.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas D., Orazani N., Stevens M., Cruwys T., Platow M.J., Zekulin M., Reynolds K.J. United we stand, divided we fall: Socio-political predictors of physical distancing and hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic. Political Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1111/pops.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys T, Haslam C., Rathbone J.A., Williams E., Haslam S.A., Walter Z.C. GROUPS 4 HEALTH versus cognitive behaviour therapy in young people with depression and loneliness: a randomized, phase 3, non-inferiority trial with 12 month follow-up. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1192/bjp.2021.128. Preprinthttp://dx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys T., Haslam C., Walter Z.C., Rathbone J., Williams E. The connecting adolescents to reduce relapse (CARR) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of Groups 4 Health and cognitive behaviour therapy in young people. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7011-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys T., Haslam S.A., Dingle G.A, Haslam C., Jetten J. Depression and social identity: an integrative review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2014;18(3):215–238. doi: 10.1177/1088868314523839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys T., Ng N.W.K., Haslam S.A., Haslam C. Identity Continuity protects academic performance, retention, and life satisfaction among international students. Appl. Psychol. 2020;0(0):1–24. doi: 10.1111/apps.12254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys T., Wakefield J.R.H., Sani F., Dingle G.A., Jetten J. Social isolation predicts frequent attendance in primary care. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018:817–829. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawel A., Shou Y., Smithson M., Cherbuin N., Banfield M., Calear A.L., Farrer L.M., et al. The effect of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of Australian adults. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles A.M., Qualter P. Review: Alleviating loneliness in young people—a meta-analysis of interventions. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2020;1:17–33. doi: 10.1111/camh.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erzen E., Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2018;64(5):427–435. doi: 10.1177/0020764018776349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groarke J.M., Berry E., Graham-Wisener L., McKenna-Plumley P.E., McGlinchey E., Armour C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PLoS One. 2020;15(9 September):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder M.M., Wakefield J.R.H., Bowe M., Kellezi B., Mair E., Mcnamara N., Wilson I., Stevenson C. Evaluation and exploration of a social prescribing initiative: study protocol. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1359105318814160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C., Jetten J., Cruwys T., Dingle G.A., Haslam S.A. 2018. The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C., Cruwys T., Chang M.X.-L., Bentley S.V., Haslam S.A., Dingle G.A., Jetten J. GROUPS 4 HEALTH reduces loneliness and social anxiety in adults with psychological distress: findings from a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2019;87(9):787–801. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C., Cruwys T., Haslam S.A., Dingle G., Chang M.X.-L. Groups 4 Health: evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;194:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C., Haslam S.A., Jetten J., Cruwys T., Steffens N.K. Life change, social identity, and health. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021;72:635–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-060120-111721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J.D., Crawford J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen J.C., Gluud C., Wetterslev J., Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials—a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med. Res. Method. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J., Reicher S.D., Haslam S.A., Cruwys T. SAGE Publications; 2020. Together apart: The psychology of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.M., Haslam S.A., Jetten J., Williams W.H., Morris R., Saroyan S. That which doesn’t kill us can make us stronger (and more satisfied with life): the contribution of personal and social changes to well-being after acquired brain injury. Psychol. Health. 2011;26(3):353–369. doi: 10.1080/08870440903440699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D.S., Cloonan S.A., Taylor E.C., Miller M.A., Dailey N.S. Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam B.C.P., Haslam C., Haslam S.A., Steffens N.K., Cruwys T., Jetten J., Yang J. Multiple social groups support adjustment to retirement across cultures. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;208:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R., Singmann H., Love J., Buerkner P., Herve M. Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R Package Version 1.15. 2020;34(1):216–221. doi: 10.1080/00031305.1980.10483031>.License. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond P.F., Lovibond S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moccia L., Janiri D., Giuseppin G., Agrifoglio B., Monti L., Mazza M., Caroppo E., Fiorillo A., Sani G., Di Nicola M., Janiri L. Reduced hedonic tone and emotion dysregulation predict depressive symptoms severity during the covid-19 outbreak: an observational study on the Italian general population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon N.E., Yarcheski T.J., Yarcheski A. Validation of the revised UCLA loneliness scale for adolescents. Res. Nurs. Health. 1995;18(3):263–270. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi C.M., Chen H.Y., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2011;15(3):219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon O.T., Haslam S.A., Haslam C., Cruwys T., Kearns M., Jetten J. The social psychology of responses to trauma: social identity pathways associated with divergent traumatic responses. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019;30(1):311–348. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1711628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Fat L., Scholes S., Boniface S., Mindell J., Stewart-Brown S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017;26(5):1129–1144. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A.C., Hooke G.R., Morrison D.L. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in depressed clinical samples. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007;46:283–297. doi: 10.1348/014466506X158996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt C.S. In: The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology. Millsap R.E., Maydeu-Olivares A., editors. Sage Publications; 2009. Quasi-experimental design; pp. 46–71. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher S., Drury J. Pandemic fatigue? How adherence to covid-19 regulations has been misrepresented and why it matters. BMJ. 2021;372(April):6–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. Ucla loneliness scale version 3: reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani F., Herrera M., Wakefield J.R.H., Boroch O., Gulyas C. Comparing social contact and group identification as predictors of mental health. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. /Br. Psychol. Soc. 2012;51(4):781–790. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour-Smith M., Cruwys T., Haslam S.A., Brodribb W. Loss of group memberships predicts depression in postpartum mothers. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017;52:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley C.G., Bulbulia J. Faith after an earthquake:a longitudinal study of religion and perceived health before and after the 2011 Christchurch New Zealand earthquake. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens N.K., Cruwys T., Haslam C., Jetten J., Haslam S.A. Social group memberships in retirement are associated with reduced risk of premature death: Evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Brown S., Tennant A., Tennant R., Platt S., Parkinson J., Weich S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2009;7:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E., Burton E., Bearman S.K., Rohde P. Randomized trial of a brief depression prevention program. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007;45(5):863–876. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield J.R.H., Kellezi B., Stevenson C., McNamara N., Bowe M., Wilson I., Halder M.M., Mair E. Social prescribing as ‘social cure’: a longitudinal study of the health benefits of social connectedness within a social prescribing pathway. J. Health Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1359105320944991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G., Sessions J.G., Fu Y., Wall M. A multilevel cross-lagged structural equation analysis for reciprocal relationship between social capital and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015;142:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]