Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the crucial role of people's compliance for the success of measures designed to protect public health. Within the frame of Semiotic Cultural Psycho-social Theory, we discuss how the analysis of people's ways of making sense of the crisis scenario can help to identify the resources or constraints underlying the ways the citizens evaluate and comply with the anti-covid measures. This study aimed to examine how Italian adults interpreted what was happening in the first wave of the pandemic and how the interpretation varied in the period up to the beginning of the second wave.

Diaries were collected for six months, from 11 April to 3 November 2020. Participants were periodically asked to talk about their life ‘in the last few weeks’. A total number of 606 diaries were collected. The Automated Method for Content Analysis (ACASM) procedure was applied to the texts to detect the factorial dimensions – interpreted as the markers of latent dimensions of meanings– underpinning (dis)similarities in the respondents' discourses. ANOVA were applied to examine the dissimilarities in the association between factorial dimensions and production time.

Findings show that significant transitions occurred over time in the main dimensions of meaning identified. Whereas the first phase was characterized by a focus on one's own daily life and the attempt to make sense of the changes occurring in the personal sphere, in the following phases the socio-economic impact of the crisis was brought to the fore, along with the hope to returning to the “normality” of the pre-rupture scenario. We argued that, despite the differences, a low sense of the interweaving between the personal and public sphere emerged in the accounts of the pandemic crisis throughout the sixth months considered; a split that, we speculate, can explain the “free for all” movement that occurred at the end of the first wave and the beginning of the second wave.

Keywords: COVID-19, Semiotic cultural psycho-social theory, Sensemaking, Longitudinal qualitative study, Diaries

COVID-19, Semiotic cultural psycho-social theory, Sensemaking, Longitudinal qualitative study, Diaries.

1. Introduction

In the last two years, a great deal of literature has focused on studying the multiple factors facilitating the diffusion of COVID-19, which could be addressed by non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) (Askitas et al., 2021), such as the biological characteristics of the virus, geo-environmental determinants – e.g. air pollution (Coccia, 2020a, 2021a; Fattorini and Regoli, 2020), meteorological conditions (Coccia, 2021b; Wu et al., 2020), transport and mobility specificities (Du et al., 2020), the demographic aspect of density of population (Wong and Li, 2020), the anti-contagion measures adopted (Brauner et al., 2021; Manica et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020), expenditure on the health sector (Hansen et al., 2021), levels of exposure to disinformation (Caldarelli et al., 2021) and – in the area of human sciences – the multiple factors influencing people's decisions to comply with the containment measures (Bish and Michie, 2010; Viswanath et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2021).

In this paper, adopting the lens of psychology, we focus on the last-mentioned aspect, recognizing that although structural and technical measures are needed to reduce the impact of COVID-19, yet they are often not sufficient, because they still have to be implemented by human beings. It is recognised that people often are not willing to comply with the recommended protective measures or are unable to break their habits, even if they are aware of the dangers (Dias Neto et al., 2021; Schimmenti et al., 2020), or are unable to maintain their compliance over time (Scandurra et al., 2021). A study by Tomczyk et al. (2020) on intentions to comply with behavioural recommendations to contain the COVID-19 pandemic in the German population revealed that only a quarter of the people surveyed expressed their intention to comply fully with the guidance, while the majority (about 51 %) intended to follow only some of the public actions and were less willing to engage in personal hygiene behaviours (e.g. reduced body-to-body contact, ventilation). Another study, with a larger sample in England (Wright et al., 2021), found that many people declared their intention to use a mask but were less inclined to adopt physical distancing. The study of Palamenghi et al. (2020) in Italy showed that only 59% of the respondents reported to be likely to vaccinate for COVID-19 and that citizens' trust in vaccination decreased between the first phase of the Italian pandemic, characterized by national lockdown measures, and the second one, characterized by the “reopening”. In the countries too where high levels of compliance toward government and scientists' recommendations were reported on the first wave, citizens’ willingness to maintain protective measures decreased during the second wave. Significantly, immediately after the beginning of the second wave, a document of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) stated that EU Member States were reporting signs of “pandemic fatigue” in their populations – namely a difficulty, emerging gradually over time, to follow recommended protective behaviours. This seems to be the case in Italy, the context of the current study and the second country hit by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) infection (February 21, 2020), after China.

In response to the first wave, several interventions have been deployed by the Italian government, including School closure at the national level (mandated on March 5) and a national lockdown (stay-home mandate and closure of all nonessential productive activities) issued on March 11, then eased after May 4, 2020 (Guzzetta et al., 2021). In this phase, population compliance was high (Carlucci et al., 2020; Travaglino and Moon, 2021). Based on a large sample of Italian adults, the study of Carlucci et al. (2020) showed very high rates of adherence to quarantine restrictions and recommendations, after 15 days of the national lockdown. In May 2020, with the gradually reopening of shops, bars, restaurants and churches, Italian living styles got back to resemble the pre-pandemic situations (e.g. social gatherings on beaches and parks). A kind of “free for all” spread among population supported by the belief that the virus was not that dangerous anymore (Sarli and Artioli, 2020). The second wave of COVID-19 began in Italy over the month of September 2020 and then sharply increased, pushing the government to establish at the begin of November a system of physical distancing measures organized in progressively restrictive tiers imposed on a regional basis according to epidemiological risk assessments. A progressive reduction of the time spent outside of home has been registered; however, this reduction was far from that observed during the nation-wide lockdown imposed to counter the first wave, even in the strictest tier where a stay-home mandate was in place (Manica et al., 2021). At the time of writing (summer, 2021), Italian citizens are expressing increasing mistrust in government, biomedical research and vaccination (Chirico et al., 2021; Palamenghi et al., 2020) and a broad segment of the population manifest behaviour that appears inconsistent, even in overt contrast, with the requirements of crisis management (Di Filippo, 2021).

Recognizing that a complex set of interrelating factors could play a role in explaining the variability in people's decisions to obey preventative measures, ranging from intrapersonal to socio-cultural dimensions (Bish and Michie, 2010; Viswanath et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2021), in this paper, within the frame of Semiotic-Cultural Psycho-social Theory (SCPT) (Salvatore et al., 2018, 2019b; Venuleo et al., 2020a), we emphasize that crucial role of people sensemaking processes in shaping people's cognition and action. Accordingly, also the ways the citizens evaluate and comply with the anti-covid measures established by governments depend on how they represent the pandemic crisis, the challenges it imposed, their role in it. Particularly, we argue that compliance with anti-covid measures implies, at last in the medium term, the capacity to represent the systemic dimension of the crisis, recognizing the health care as a shared enterprise, and, thus, to go beyond the absolutization of one's world of life (Salvatore et al., 2019a, 2021) and to acknowledge the intertwining between the individual sphere of experience and the sphere of collective life (Venuleo et al., 2020b). Disaster research shows that the awareness of being part of a “community of fate” and the emergence of shared identities are crucial for collective and proactive responses (Drury et al., 2019). de Rosa and Mannarini (2021) argue that in a pandemic situation, only if social embeddedness and a sense of connectedness is maintained can communities adopt social norms and behaviours which are functional in the containment of the outbreak and face the collective emergency. This argument is supported also by recent studies (Bargain & Aminjonov, 2020; Borgonovi and Andrieu, 2020) highlighting how communities with high levels of social capital socially distanced and reduced mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic more than communities with low levels of social capital. Other studies on prior pandemics show that social capital was associated with other forms of health protective behaviours, such as the intention to receive vaccination against and the intention to wear face masks (Chuang et al., 2015; Rönnerstrand, 2014).

Below, the main tenets of SPCT which oriented our focus on the sensemaking process will be introduced. Then, a qualitative longitudinal study is presented, which was aimed to examine how Italian adults made sense of what was happening in the first wave of the pandemic and how the interpretation of the crisis varied in the period up to the beginning of the second wave. The findings will allow to highlight how tracking changes on people's meaning trajectories could help to identify the resources or constraints in people's responses to the crisis scenario, which need to be addressed in order to promote the adoption of anti-infection measures.

2. Theoretical framework

Merging two main lines of thought – cultural psychology (inter alia: Bruner, 1991; Cole, 1998; Shweder and Sullivan, 1990) and semiotic psychodynamic theory –, SPCT (Salvatore, 2018; Valsiner, 2007; Van Herzele and Aarts, 2013) has developed Vygotsky's seminal recognition of the mediational function played by meaning between mind and world and recognized the affective side of sensemaking processes (Matte Blanco, 1975; Salvatore and Freda, 2011).

According to SPCT, basic, bi-polar dimensions of affect-laden meanings (e.g., foe/friend; pleasant/unpleasant; passivity/engagement) foster and constrain the way the sense-maker interprets any specific event, object and condition of their life (Salvatore et al., 2018). People’ s interpretative categories, thus, are not simply ways of representing the circumstances and challenges related to the pandemic but a way to being channelled to act and react in a certain way to, enabling attitudes and behaviour to be oriented (Marinaci et al., 2021). For instance, previous studies offer support to the idea that the low compliance with measures of physical distancing and mandatory mask use can be interpreted as a way of enacting, affirming and reproducing the idea that “life is a matter of resisting the power of institutions that violate civil liberties”, with an identity valence (Dolan, 2020; Taylor and Asmundson, 2021).

Further studies show that people vary in their tendency to make use of generalized meanings (Barrett et al., 2001; Barrett, 2006; Feldman, 1995) and that their capacity to enact adaptive responses is a function of this variable degree (Rochira et al., 2019; Venuleo et al., 2015, 2016, 2020c; Venezia et al., 2019). For instance, worldviews organized by strongly negative and extreme connotations of the social environment were found to be associated to vaccination hesitancy (Rochira et al., 2019). In the global scenario of the pandemic, among other manifestations, highly affect-laden interpretations can be recognized in conspiracy theories which recent studies found to be associated with a lower rate of compliance with public health guidance (Allington and Dhavan, 2020; Maftei and Holman, 2020).

According to SPCT and consistently with other semiotic and cultural perspectives, people's sensemaking does not develop in a social vacuum: their systems of meaning (and related feeling, attitudes and values…) represent one of the by-products of cultural dynamics (Salvatore and Zittoun, 2011): they emerge as the consolidation within the socio-cultural milieu of a pattern of sensemaking magnifying a polarity of one or more bi-polar dimensions of affect-laden meanings composing the culture. Once activated, the semiotic patterns work as autopoietic systems (Maturana and Varela, 1980), that is, they interpret the changes occurring in the environment from and for the sake of the reproduction of its own inner organization (Russo et al., 2020); the changes are interpreted as local modifications of the same entity over time.

This view has an important methodological implication, since it implies a certain level of predictability on the further development of the trajectory of sensemaking (Mannarini and Salvatore, 2019): the understanding of what is happening allows us to represent and comprehend what is in store; namely, by knowing how people make sense of what is happening in a certain time one can predict what will follow. Consistently with this tenet, one can assume that, given two different moments of the pandemic outbreak, the ways people interpreted the crisis at time two was selected from a certain domain of generalized meanings which was already active at time one. This does not mean that the contents of people’ s feeling, thinking or behaving were the same over the period. One can expect a local adjustment (Mossi and Salvatore, 2011), that is an evolutionary scenario where one of the polarities composing one or more of the bi-polar dimensions of affect-laden meanings (e.g. foe/friend; pleasant/unpleasant; passivity/engagement) is strengthened or weakened in favour of the other, yet the basic dimensions used to interpret the experience do not change radically. For instance, while at the beginning of the pandemic, the citizens may preferentially envisage the crisis in terms of a very threatening symbolization and the “stay at home” measure as a “salvific and convenient” situation, the evolving of the circumstances could make the semiotic connotation of “threatening” lose ground compared to its opposite “not threatening” connotation and the discursive use of certain words would also change (e.g., patterns of words related to the “threatening” set of meanings could weakened in their use; “staying at home” could be associated to the words “not salvific” and “not convenient”). However, insofar as it is a generalized structure of meaning, the bipolar structure of meaning “threatening/not threatening” will continue to shape the meaning of the experience. The study by Washer (2010) on the lay representations of the origin of HIV/AIDS provides another good example. He shows how the disease was originally associated with gay men as opposed to the rest of population, which enable the latter to feel safe. When knowledge that AIDS also affects heterosexuals became widespread, people with supposedly low moral standards were contrasted to those with high moral standards. The target of othering, thus, shifts from one out-group (i.e., gays) to another (i.e., people with loose morals) to symbolically cope with the threat. However, the contrast between in-group and out-group was preserved (Mayor et al., 2013).

In the light of the theoretical considerations made above, we expect that a) a local adjustment occurred in the ways Italian adults made sense of what was happening from the first wave of the pandemic to the beginning of the second wave, related to the contingent changes occurring in the scenario (e.g. decrease or increase in infection rates, media alarm, social impact of the crisis); b) despite the differences, a low sense of the interweaving between the personal and public sphere emerged in the accounts of the pandemic crisis throughout the period considered, a split that can explain the “free for all” movement that occurred at the end of the first wave and the beginning of the second wave.

3. Material and methods

It is recognised how diary-based research allow to shed light on ‘ordinary’ lives (Elliott, 1997; Hampsten, 1989), offer the opportunity to study change over time (Mort et al., 2005) and to capture people making sense of their social experience and of their own role in it (Andrews, 2007; Bertaux, 1981). In the current study, a six-month diary collection was adopted in order to track people's view of the pandemic over time: respondents at least 18 years of age were asked to write about their experience of pandemic scenario periodically (once every two weeks for the first three months and once a month for the following three months), starting by the open stimulus: “My life in the last weeks …”. The choice of this stimulus lies in its unconstraining nature, namely it allowed people leeway to write about what was important to them and to structure entries as they felt appropriate (Elliott, 1997; Marinaci et al., 2021). Participants were encouraged to write everything that came to mind about the situation and to use the space they needed.

3.1. Research settings, sample and data

Diaries were collected between 11th April and 3rd November 2020, as part of a mixed-method research project – approved by the Ethics Commission for Research in Psychology of the Department of History, Society and Human Studies of the University of Salento (protocol n. 16811 of 28 January 2021) – aimed to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 health emergency on everyday life.

An anonymous survey was available online from 1st April to 19th May 2020 coinciding with the government's “Close down Italy” decree (“Chiudi Italia”) and circulated through social networks (e.g., Facebook). In a section of the survey, respondents were asked to enrol in a second stage of the project focused on the diary collection: they were informed about the frequency of diaries and how to participate. They were also assured that all information would be treated confidentially and anonymously. The people willing were asked to leave an email address or a contact number so as to receive a periodic reminder to fill in the diary. To guarantee the anonymity of the diaries, each respondent was asked to construct an alphanumeric code, consisting of the first two letters of their name and surname and the date of birth (not including the day). The diaries were sent through an online platform, built ad hoc, and access limited to participants only, with access password. All participants provided informed consent before updating their diary on the online (Microsoft) survey. The sending of the diary on the platform was then tied to the insertion of the sending date and the personal alphanumeric code. A reminder to fill in the diary was periodically sent through an e-mail, which included the explicit explanation that the success of the work depended crucially on subjects' continued participation, while also making it clear that such participation was voluntary. Contact details of the team project were reported in each mail with the invitation to ask about any doubt or clarification. Since people gained access to the link of the survey over a variable period (from 1st April to 19th May 2020), each ten days a check was made of the people participating and the reminder email to fill out the first diary was sent. The individuals taking part therefore sent their first diary and the following ones on different dates.

571 people (Mean age = 35.57; DS = 14.75; women: 67.3%; North Italy: 35.4%; Centre Italy: 26.6%; South Italy: 38%) agreed to be recruited for the diary collection: 150 of them (26,27%) responded effectively to the request and sent the first diary; only 21 sent the last diary, yielding an attrition rate of 86%. A total number of 606 diaries were collected and all included in the final analysis.

They were categorized according to a criteria of time production, taking into account the temporal evolution of the pandemic in Italy and health measures established by the Government. Accordingly, three phases were considered: phase 1 coincides with the Italian lockdown and comprises the diaries collected from 11th April to 8th May 2020; phase 2 comprises the months characterized by a decreasing infection slope and the end of stay-at-home measures (from 9th May to 3rd September 2020); phase 3 comprise the periods marking the beginning of the second wave (from 4th September to 3rd November 2020). In Table 1 the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample under analysis for each phase are reported. No significant differences exist with respect to gender, educational and job status, region of residence, except for age, in which a prevalence of the older ages (>54) emerges.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the Italian respondents, disaggregated for the three temporal phases.

| Phase 1 (From 11th April to 8th May 2020) | Phase 2 (From 9th May to 3rd September 2020) | Phase 3 (From 4th September to 3rd November 2020) | Total (606) | Chi-square | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 39 (6.4%) | 92 (15.2%) | 8 (1.3%) | 139 (22.9%) | 1.076 | .584 |

| Female | 111 (18.3%) | 326 (53.8%) | 30 (5.0%) | 467 (77.1%) | |||

| Age range | 18–26 | 68 (11.2%) | 171 (28.2%) | 11 (1.8%) | 250 (41.3%) | 22.242 | .014 |

| 27–35 | 15 (2.5%) | 37 (6.1%) | 2 (0.3%) | 54 (8.9%) | |||

| 36–44 | 11 (1.8%) | 34 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 45 (7.4%) | |||

| 45–53 | 19 (3.1%) | 41 (6.8%) | 3 (0.5%) | 63 (10.4%) | |||

| 54–63 | 30 (5.0%) | 82 (13.5%) | 13 (2.1%) | 125 (20.6%) | |||

| >63 | 7 (1.2%) | 53 (8.7%) | 9 (1.5%) | 69 (11.4%) | |||

| Educational Status | Middle | 4 (0.7%) | 12 (2.0%) | 2 (0.3%) | 18 (3.0%) | 2.710 | .608 |

| High | 63 (10.4%) | 166 (27.4%) | 19 (3.1%) | 248 (40.9%) | |||

| Degree | 83 (13.7%) | 240 (39.6%) | 17 (2.8%) | 340 (56.1%) | |||

| Occupational Status | Student | 57 (9.4%) | 147 (24.3%) | 9 (1.5%) | 213 (35.1%) | 11.447 | .324 |

| Employee | 61 (10.1%) | 167 (27.6%) | 17 (2.8%) | 245 (40.4%) | |||

| Freelance | 18 (3.0%) | 37 (6.1%) | 3 (0.5%) | 58 (9.6%) | |||

| Unemployed | 5 (0.8%) | 16 (2.6%) | 2 (0.3%) | 23 (3.8%) | |||

| Temporary employee | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.7%) | |||

| Retired | 8 (1.3%) | 49 (8.1%) | 6 (1.0%) | 63 (10.4%) | |||

| Living place | North | 50 (8.3%) | 142 (23.4%) | 12 (2.0%) | 204 (33.7%) | 1.222 | .874 |

| Centre | 40 (6.6%) | 127 (21.0%) | 11 (1.8%) | 178 (29.4%) | |||

| South | 60 (9.9%) | 149 (24.6%) | 15 (2.5%) | 224 (37.0%) |

3.2. Data analysis procedure

According to Grossoehme and Lipstein (2016), there are two primary approaches to analysing qualitative longitudinal data: recurrent cross-sectional and trajectory. Whereas recurrent cross-sectional analysis explores themes and changes over time at the level of the entire study sample, trajectory explores changes over time for an individual or small group of individuals. Cross-sectional analysis is likely preferred when, as in the current study, the primary interest of the research is comparing different time points and question of how group-level themes/beliefs/attitudes change over time, and when maintaining a cohort is not feasible, for instance because of a long-time span. The recurrent cross-sectional approach can be thought of as a series of smaller studies given that at each time point the data from all participants are analysed as a unit.

In order to identify (dis)similarities in the generalized meanings underpinning the collected diaries, the Automated Method for Content Analysis (ACASM) procedure (Salvatore et al., 2012, 2017) was applied to the whole corpus of the collected texts. The method is grounded on the general assumption that the meanings are shaped in terms of lexical variability. Accordingly, the method aims at detecting the ways the words combine with each other (that is, co-occur) within utterances, independently of the referentiality of the sentence (Lebart et al., 1998). ACASM procedure – performed by T-LAB software (version T-Lab Plus 2020; Lancia, 2020) – was applied as follows.

Firstly, the textual corpus of narratives was split into units of analysis, called Elementary Context Units (ECUs); the lexical forms present in the ECUs were identified and categorised according to the “lemma” they belong to. A lemma is the citation form (namely, the headword) used in a language dictionary: for example, word forms such as ‘‘boy’’ and ‘‘boys’’ have ‘‘boy’’ as their lemma. A digital matrix of the corpus was defined, having as rows the ECU, as columns the lemmas and in cell xij the score of ‘1’ if the jth lemma was contained in the ith ECU, otherwise the xij cell received the score of ‘0’. Table 2 describes the characteristics of the dataset.

Table 2.

Dataset.

| N | |

|---|---|

| Texts in the corpus | 606 |

| Elementary contexts (EC) | 3358 |

| Types | 15641 |

| Lemma | 8255 |

| Occurrences (Tokens) | 155461 |

| Threshold of lemma selection | 24 |

| Lemmas in analysis | 495 |

Second, a Lexical Correspondence Analysis (LCA) – a factor analysis procedure for nominal data (Benzécri, 1973) – was carried out on the obtained matrix to retrieve the factors describing lemmas having higher degrees of association, i.e., occurring together many times. Each factorial dimension describes the juxtaposition of two patterns of strongly associated (co-occurring) lemmas and, according to the model grounding the analysis, can be interpreted as a marker of a latent dimension of meanings underpinning dis(similarities) in the respondents' discourses. The first two factors extracted from LCA were selected, as the ones explaining the broader part of the data matrix's inertia, and labelled by three experienced researchers, in double-blind procedure, on the basis of the global meaning envisaged by the set of co-occurring lemmas associated with each polarity. Disagreement among researchers was overcome using a consensus procedure.

As second step, we compared the positioning of the diaries on the retrieved factorial space according to the criteria of categorization of production time, based on the temporal evolution of the pandemic (three phases). To this end, the factorial coordinates associated to the time period were identified and a set of ANOVA analysis applied to explore the association between factorial dimensions and production time.

4. Results

4.1. Generalized meanings organizing the view of the pandemic

Tables 3 and 4 illustrate respectively the first and the second factorial dimension obtained by the ACASM procedure. For each polarity of the two dimensions, the lemmas with the highest level of association (V-Test) are reported, as well as their interpretation in terms of labeling of their meaning. Henceforth, we adopt capitals letters for labelling the Dimensions of meaning extracted by the LCA and italics for the interpretation of polarities and the lemmas which characterize them. Furthermore, a few sentences from the diaries are reported, which are exemplificative of the generalized meaning characterizing each polarity.

Table 3.

Lexical Correspondence Analysis output. First factorial dimension characterizing the diaries collected in Italy from11th April to 3rd November.

| Unit of observation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily life scenario (-) |

Crisis scenario (+) |

||

| Lemmas | Test values∗ | Lemmas | Test values∗ |

| Morning | -16.2978 | Fear | 11.9821 |

| Evening | -13.0459 | Economic | 11.6494 |

| Afternoon | -12.9149 | Politics | 11.6206 |

| Reading | -12.6041 | Contagious | 10.5948 |

| Lunch | -12.4895 | Coronavirus | 9.6886 |

| To cook | -12.0641 | Health | 9.6639 |

| Dinner | -11.5871 | Situation | 9.3458 |

| Breakfast | -11.429 | Belief | 7.9934 |

| Day | -11.205 | Person | 7.8057 |

| Home | -10.4728 | COVID_19 | 7.8024 |

| Book | -10.3294 | Rule | 7.7454 |

| Sea | -10.1408 | To respect | 7.6358 |

| Saturday | -10.0127 | Uncertainty | 7.138 |

| Water | -9.6529 | Level | 6.9937 |

| To get up | -9.4714 | Government | 6.9452 |

| Sun | -9.0674 | Norms | 6.92 |

| Read | -8.9343 | Cases | 6.9126 |

| Monday | -8.9161 | Behaviour | 6.8238 |

| Walk | -8.7171 | Respect | 6.7249 |

| Sunday | -8.6831 | Emergency | 6.7085 |

| Garden | -8.6321 | Social | 6.7077 |

| PC | -8.6009 | Future | 6.3721 |

| FILM | -8.5109 | Measure | 6.3681 |

| Television | -8.3092 | To manage | 6.2863 |

| Coffee | -8.2829 | Crisis | 6.2586 |

| Warm | -8.1742 | Security | 6.0893 |

| To throw | -7.9183 | Condition | 5.7122 |

| Dog | -7.7855 | To happen | 5.609 |

| To eat | -7.7257 | To think | 5.4982 |

Highest levels of association standard scores (V-Test).

Table 4.

Lexical Correspondence Analysis output. Second factorial dimension characterizing the diaries collected in Italy from11th April to 3rd November.

| Challenges posed by the crisis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Returning to normality (-) |

Making sense (-) |

||

| Lemmas | Text values∗ | Lemmas | Text values∗ |

| Mask | -27.7282 | Time | 9.4569 |

| Distance | -19.7899 | To write | 8.9453 |

| To exit | -14.6763 | Moment | 8.6293 |

| Exit | -14.6763 | To understand | 7.9978 |

| Glove | -14.3061 | Thought | 7.363 |

| Security | -13.9666 | Lived | 7.2688 |

| To wear | -12.8629 | To live | 7.1134 |

| Supermarket | -12.4201 | Reading | 7.105 |

| Hand | -11.8479 | Future | 6.8869 |

| Shop | -11.6572 | Difficulty | 6.7725 |

| Distancing | -11.4887 | Diary | 6.7541 |

| People | -11.4799 | Condition | 6.4832 |

| Row | -11.2389 | To reflect | 6.478 |

| To respect | -10.7622 | To dedicate | 6.2708 |

| Norm | -10.477 | To read | 6.2329 |

| Subway | -10.3437 | To face | 6.1959 |

| Bar | -10.1361 | Study | 6.0421 |

| To breath | -9.7082 | Useless | 6.0414 |

| Person | -9.6268 | My_self | 5.9246 |

| Around | -9.283 | Strenght | 5.8604 |

| Street | -9.1376 | Account | 5.8525 |

| Open | -8.4041 | Last | 5.8381 |

| Air | -8.3802 | Book | 5.7563 |

| To maintain | -8.315 | Years | 5.6901 |

| Beach | -8.0705 | Working | 5.6315 |

∗ Highest levels of association standard scores (V-Test).

FIRST DIMENSION. unit of observation. This dimension opposes two patterns of words which foregrounds two different units of observations: Daily life scenario (-) versus Crisis scenario (+).

On the Daily life scenario polarity (-), temporal trackers which refer to a short-term horizon – days of the week (Day, Monday, Saturday, Sunday) and different times of the day (morning, afternoon, evening) – co-occur with lemmas which refer to routines that take place in the domestic environment (home, to get up, sleeping; to cook, to eat, lunch, dinner, breakfast) and leisure time (pc, television, film, reading, book, garden, to walk). The gaze is confined to the restricted sphere of domestic life, the experience is rooted in the here and now and it does not envisage development. The diary seems to take the form of a chronicle report, in a time frame of monotonous days which all seem the same in a monochrome life.

In the morning I wake up around 9, I open social media, I read some news and I start studying for university exams. Around 12.30 I stop and start cooking, when it's my turn. Lunch with my boyfriend and until 3 o'clock we take a rest watching the news. The afternoon is the most difficult phase of the day, because in the morning I have more energy to study. So, if I'm energetic enough I study, otherwise I rest, read a book, sometimes I bake a cake or play some games on my computer or on my phone. (Female, 24 years old, student)

Some days I studied even after dinner. Usually after dinner I tended to relax; instead now I have also given up watching the TV series that I see on the PC or with my roommates in the living room. I'm always at the PC and I realize that as functional as it is, as it allows me to get on with studying, it's starting to weigh on me. At the end of the evening my eyes are tired and so continuing to look at a screen is really difficult. The days are going by and I'm losing track of time. I can see how many days have passed just by looking at the calendar; in fact, every morning, the first thing I do is put an x on the current date. (Female, 24 years old, student)

The feeling of being suspended in a limbo is evoked; the rupture of the previous state/sphere of experience does not herald the entering/emerging of a new phase but is seen as an empty time and one can only wait for it pass:

My life is in total limbo. I know that time is passing, I calculate the days because I do online class and I set deadlines in the study, but for me in reality this time does not exist. (Female, 21 years old, student)

It's very difficult to keep a diary right now, because all the days seem the same. As far as I am concerned, the morning is quite busy with housework, in the afternoon I read, solve puzzles, and watch television inattentively. (Female, 73 years old, retired)

The secret is to have a routine to follow: wake up, if not at dawn, early enough for the sun not to be high: put the house in order and start cooking, breakfast and shower, check personal mail and work mail, walk the dog, look at my teenage son's programme of online lessons and then, keep going alternating work and social contacts. (Female, 48 years old, employed)

On the Crisis scenario polarity (+), lemmas refers to different levels of the pandemic crisis (COVID-19, coronavirus, contagious, infection, emergency), its impact on the public sphere (crisis, economic, politics, social, health, situation), and related feelings of fear and uncertainty about the future – which suggests a crisis of meaning, the feeling of not being able to interpret what will happen – co-occur with lemmas referring to institutional responses (government, to manage, measures, rules, norms) and citizens’ attitudes and behaviours towards measures and norms (person, to respect, respect, behaviour). A “third” is evoked, who creates an impasse, who is pessimistic about the possibility of overcoming the emergency and learning something from the crisis: a political class felt to be inadequate, who take badly timed and/or unclear decisions, who act by trial and error, who promise (e.g. financial support to citizens) but do not keep promises; other citizens, breaking the health measures, unaware of the danger of infecting and seen as not respecting the work of the doctors and the duty toward the community. Examples of discourses are:

I feel very strongly about the economic and social crisis that is emerging with an inadequate political class. I am very pessimistic not because of my socio-economic conditions but for the society around me. In essence, I do not see any clear guidelines because it seems to me that attempts are being made without planning, but instead in the aftermath of the events, but above all nothing has been done. (Male, 71 years old, retired)

This restaurant where we were, before the pandemic had 70 seats, while now it has only 34; but the charges for utilities and rents remained the same as before. The aid promised to many entrepreneurs, especially for loans, has not been maintained, as the banks have not granted it, despite the guarantees provided by the State and procedures that clearly defined who was entitled and the amounts involved. I mean, as always, they did what they wanted. (Male, 65 years old, retired)

What has changed: coronavirus or the information? The anarchy of behaviour especially in the centres and seaside towns is bewildering. There is quite a clear basic feeling that, just like before and even more so, the politicians still rely on promises, catchy expressions, shameful behaviour and complete ignorance of a minimum of management and economic planning. In short: we have learned nothing and probably missed another precious opportunity that will cost us dear and of course will be borne by the weakest. (Male, 71 years old, retired)

I hope that the situation will continue to improve and that the reopening, albeit gradually, will not lead to a new surge of cases. Unfortunately, in this sense, I do not feel too optimistic: how can we move towards an improvement when, in times of extremely restrictive measures, we continue to see many people breaking the rules? When opening the window in the morning to let some fresh air into the rooms or when shopping you frequently see people walking in pairs without masks or people who even with a mask wear it under their nose or lowered to be able to breathe or talk better. (Female, 26 years old, student)

With my mask and gloves, I had the feeling of being a Martian because in the centre very few people were wearing a mask, and many also lowered it. That pisses me off, not so much for me, but for all those poor doctors who died! I simply do not understand, in these cases, the typically small-town stupidity, found also in the city, of so many people that lack respect in front of a danger that is still among us. Sometimes I think I'm wrong, too rigid! But then I also think of how many people are still infected. just for the thoughtlessness of the many who are not aware of their duties. The average Italian only has rights and very few duties! (Female, 70 years old, retired)

SECOND DIMENSION. challenges imposed by the crisis: This dimension opposes two patterns of words which foreground two different ways of representing the challenges posed by the crisis: returning to normality (-) versus making sense (+).

On the Returning to normality polarity (-), lemmas referring to contagion containment measures, i.e. personal protection devices (to wear, mask, glove, hand...) and measures of physical distance (to respect, to maintain, distancing, distance, meter, norms, security, shop, supermarket), co-occur with lemmas that evoke the return to the open air (open, to exit, exit, to breath, air, street, around) and to the places of meeting and leisure time (bar, beach). The co-occurrence of the discourses suggest that the feeling is that the personal limitations imposed by the crisis could be sustained on the condition/by reason of a return to a pre-pandemic normality, which may restore freedom of movement, social relationships, old habits and routines, as if nothing had happened (“It seems that the chapter is closing ... the worst is over”). Discourses are imbued with the hope that “the worst is over”, that the chapter is closing with a happy ending.

I spend my days using the time in many different ways, but the most recurrent thought is to the future, when it will again be possible to breathe in the freedom that we miss so much, that freedom that has always been so obvious that we don't even realise how precious it was. (Female, 28 years old, unemployed)

My hope to get closer to normal has increased with the beautiful days and the coming and going of more people after the opening of the florists near home. I took advantage of that by walking two mornings very early. I love the fresh air you breathe and the feeling you get walking through the countryside in the fresh air early in the morning. Obviously, it cannot replace proper training, but it helped me to take my mind off things and make it a little freer. In fact, it was as if the mind had the opportunity to refresh itself and then I wanted to take advantage of it before they impose limits on going out again. (Female, 24 years old, student)

I went out for a walk at the lake. Another night I went out for a drink with some friends at the bar. I was able to meet with some friends I hadn't seen in months, with relatives. All very nice. I wonder if we are breathing an air of freedom that will last or if there will be a new peak as some predict. I am very hopeful. (Female, 24 years old, student)

It's beautiful and very strange. It seems that the chapter is closing but the story is among the most beautiful ever. Knowing that we've done it, that the worst is over, and that I haven't experienced it so badly. And a few days ago, I was leaving the house forgetting to take my mask, like going back in time, when the only thing you had to remember were house keys, phone and wallet. I was afraid that the opposite would happen, that wearing a mask would become normal, that people would continue to see it on people's faces even in their dreams, that it might make me feel weird to see the movies where they obviously don't wear one. But that was not the case. (Female, 24 years old, student)

The incredible and unpredictable experience of coronavirus is spoken of in the past. Masks and gloves are gradually worn less and less; interpersonal and social distances are gradually becoming shorter. Even the media are less focused on COVID-19 The pandemic seems, in short, behind. You breathe a mild air in a pre-existing climate. (Female, 56 years old, employed)

On the Making sense polarity (+), lemmas evoke a space-time suspension of actions and routines (time, moment, to write, to read), which opens the door to an “inner journey”, the reflection on what is happening in one's life (to understand, to reflect, thought, lived, to live, condition), on one's resources and limits to cope (to face, difficulty, strengths, myself), on what matters and what does not (useless). Like a “bitter pill”, the breakdown is felt as a chance to learn a new perspective towards oneself and others; a making sense of things which allows one to re-affirm the possibility of thinking of the future. Most discourses focus on the changes that have occurred in the private sphere, the greater awareness acquired towards one's emotions and the values of family relationships and friendship.

I think the disruption of the busy and chaotic routine of my previous life is a bitter pill, that is serving to heal the wounds of relationships that were cold and taken for granted and allow you to appreciate hidden gifts of character and magical moments in real company with husband and daughters. (Female, 55 years old, employed)

I realized in this time that I am on an inner journey, and I am looking at my life. I am concluding that I have to revise some priorities. Work had become my idol at the expense of affective relationships with both family and friends. I saw myself as a hamster who got up and ran pointlessly on his wheel without realizing the reality that surrounded me (Female, 50 years old, freelance)

These 65 days have taught me so much about my potential and my limits: in these months I have slowed down the journey towards perfecting an idyllic love relationship, accepting that the relationship I had was no longer valid and did not stimulate my personal growth, I discovered passions that I did not think I had, I discovered in myself a great sense of responsibility and discipline, in dedicating every day at least an hour of my time to sport, to reading, to myself. In these months I have discovered that I have so much courage inside me, and this is the thing that makes me most proud, having overcome one of my greatest limits ever: the fear of loneliness. (Female, 25 years old, employed)

Other passages refer to the concern about forgetting what the crisis has taught and the hope to start the transformations that society needs.

I fill out this questionnaire and I think we should all fill it out, I think we should all write down how we are now, and never forget it. On Monday there will be the first move towards normality, and inside I feel a kind of discomfort. I do not know why but we are almost all poorer now and yet it does not scare us, I feel instead that by getting back into the race towards productivity we will once again be scared of everything. (Female, 25 years old, student)

It seems to me that, in many places, rather than responding to an emergency, there is a need to face up to all those dynamics that, for various reasons, we have allowed to move us like cogs in a wheel. There's no going back to the previous life, they say. I agree and not because of the coronavirus, at least not directly, but because of those wheels which now are not able to start again like before. It makes me think, once the veil is lifted, your sight cannot be blurred. Will we have the courage to start transformations? (Female, 32 years old, employed)

4.2. The relationships between dimensions of meaning and production time

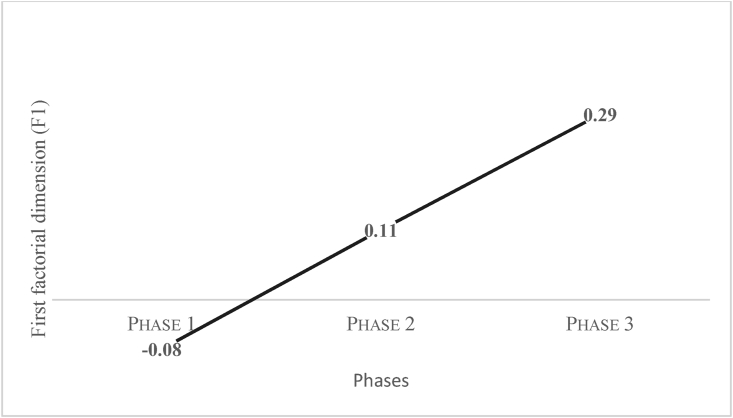

Significant differences were found on the mean scores of the three temporal phases both on the first factorial dimension (F = 2.789, p < .00), and on the second dimension (F = 20.447, p < .00). Post-hoc analyses with the Bonferroni test (Table 5) showed that significant differences on the first dimension (unit of observation) concerned all the comparisons: the first phase shows lower scores than the second phase (Mean Difference I – J = -,18415; p < .00), which has lower scores compared to the third phase (Mean Difference I – J = -.36255; p < .00). This means that over the period the diaries collected tend to move from a focus on personal daily life (negative polarity) to a focus on the crisis scenario (positive polarity) (Figure 1).

Table 5.

Bonferroni test output. Multiple comparisons on the association between factorial dimensions characterizing the diaries collected in Italy and production time.

| Dependent Variable | (I) Phase | (J) Phase | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| F1 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | -.18415∗ | .03736 | .000 | -.2738 | -.0944 |

| Phase 3 | -.36255∗ | .07127 | .000 | -.5336 | -.1914 | ||

| Phase 2 | Phase 1 | .18415∗ | .03736 | .000 | .0944 | .2738 | |

| Phase 3 | -.17840∗ | .06650 | .023 | -.3380 | -.0188 | ||

| Phase 3 | Phase 1 | .36255∗ | .07127 | .000 | .1914 | .5336 | |

| Phase 2 | .17840∗ | .06650 | .023 | .0188 | .3380 | ||

| F2 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | .22202∗ | .03708 | .000 | .1330 | .3110 |

| Phase 3 | .30989∗ | .07073 | .000 | .1401 | .4797 | ||

| Phase 2 | Phase 1 | -.22202∗ | .03708 | .000 | -.3110 | -.1330 | |

| Phase 3 | .08787 | .06600 | .551 | -.0706 | .2463 | ||

| Phase 3 | Phase 1 | -.30989∗ | .07073 | .000 | -.4797 | -.1401 | |

| Phase 2 | -.08787 | .06600 | .551 | -.2463 | .0706 | ||

Notes

F1 = First factorial dimension: Unity of observation (Daily life scenario versus crisis scenario).

F2 = Second factorial dimension: Challenged posed by the crisis (back to normality versus making sense).

Phase 1 = From 11th April to 8th May 2020 – Phase 2: From 9th May to 3rd September 2020 – Phase 3: From 4th September to 3rd November 2020.

The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

Figure 1.

Mean Plots. Position on the first factorial dimension of the diaries collected in Italy in the three phases. F1 - Unity of observation (daily life scenario versus crisis scenario). Phase 1 = From 11th April to 8th May 2020; Phase 2: From 9th May to 3rd September 2020; Phase 3: From 4th September to 3rd November 2020.

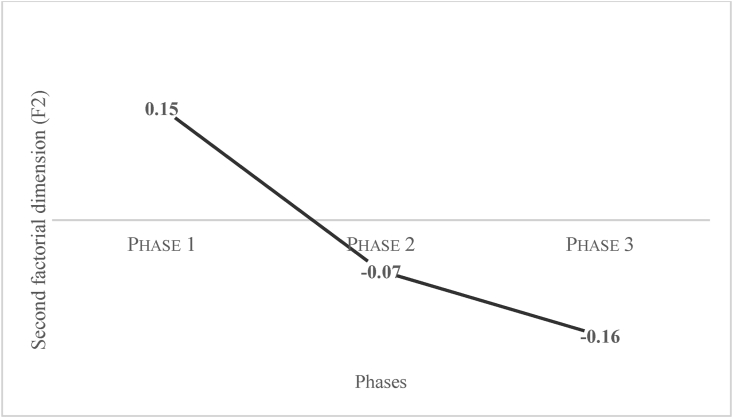

Significant differences on the second factorial dimensions (challenges imposed by the crisis) exist in the comparison between the first and the second phase (Mean Difference I – J = .22202; p < .00) and between the first and the third phase (Mean Difference I – J = .30989; p < .00), but not between the second and the third phase. This means that over the period the diaries collected tend to move from a way of representing the challenges of the pandemic crisis in terms of “making sense” of what is happening (positive polarity) to a representation centred on the idea of returning to normality (negative polarity) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean Plots. Position on the second factorial dimension of the diaries collected in Italy in the three phases. F2 - Challenged imposed by the crisis (back to normality versus making sense). Phase 1 = From 11th April to 8th May 2020; Phase 2: From 9th May to 3rd September 2020; Phase 3: From 4th September to 3rd November 2020.

5. Discussion

The two dimensions of meanings extracted by the textual analysis allow to highlight what semiotic lens were made pertinent by the respondents to account of their life in the pandemic scenario. The first dimension of meaning, representing the dialectic of two different units of observation, seems to reflect a dichotomy between the personal and social sphere. On the one hand, the focus is put on the changes occurring on one's daily life, and the attempt to manage one's time within the confines of home. The everyday life emerges as shared core of the narratives collected also in a recent Italian study of Emiliani et al. (2020), where the initial dismay for the new restricted normativity emerges along with the attempt to recognize the negative aspects of the past normality and the shifts in priority. On the other hand, the focus is on the wider crisis scenario: the feeling of anger and uncertainty related to the government's response and the other citizens' low compliance with the health measures, the social, economic and health impact of the pandemic. Similar concerns emerge also from other recent studies (Cerami et al., 2020; Codagnone et al., 2020) on the perceived impact of the Covid-19 outbreak. For instance, analysing data from Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, Codagnone et al. (2020) show a prevalence of concern for the unidimensional policy orientation during the pandemic on protecting the current healthcare systems, by putting aside the economic crisis and the mental health impact. One can note that a shared feeling of impotence seems to underpin both the polarizations that emerged. On the one hand (daily life scenario), impotence with respect to one's life because the experience is rooted in the here and now and does not envisage development; people describe a suspended time of which they do not know the end or the outcomes, as is well highlighted by this fragment: “I am dismayed that we cannot put an end to this isolation of ours. I do not know when it will end. If and when we can resume a normal social life”; on the other hand (crisis scenario), impotence towards a third (institutions, other persons) whose decisions and attitudes are outside one's control but have the power to impact on one's life.

The second dimension represents the dialectic between two different ways of representing the challenges posed by the crisis: on the one hand (returning to normality), the desire to restore what there was before, that is, habits and routines of the pre-rupture scenario (e.g. the freedom to breath without a mask, to be outdoors, to meet friends); on the other hand (making sense), the attempt to face the challenges imposed by the crisis searching for new ways to interpret ones’ life and to address the future (e.g. giving value to the affects which count). A similar dialectic emerges in the qualitative study of Tomaino et al. (2021) conducted between May and June 2020, when Italy was moving into “Phase 2” of the lockdown. Based on three open-ended questions (What are the main difficulties you are facing, and how are you dealing with them? What has the pandemic taught you about what is important and meaningful to you? What are you most looking forward to after the pandemic is over, and why?), the study shows how some coped with the pandemic mainly by waiting for the return to the past normality and remaining firm in their beliefs and certainties, whereas others coped by trying to find alternative ways of giving sense to this experience and reconstructing existential beliefs and values in the search of a change in their life.

The different positions of the diaries produced in the first temporal phase considered and in the second and third ones allow to highlight how, consistently with our expectation a) a local adjustment occurred in the ways Italian adults made sense of what was happening from the first wave of the pandemic to the beginning of the second wave; b) despite the differences, a low sense of the interweaving between the personal and public sphere emerged in the accounts of the pandemic crisis throughout the period considered.

The diaries collected in the first temporal phase (Italian lockdown: April/May) were characterized by a focus on one's own daily life and the attempt to make sense of the changes occurring: the rupture of daily habits is here valued as a time of suspension of action which allows to reflect on previous choices and to search for a new way of managing one's time and a clearer consideration of what matters; this stance is consistent with the findings of the above cited Italian qualitative study by Emiliani et al. (2020) and colleagues, highlighting how the feelings of emptiness and bewilderment narrated by people at the moment of the lockdown, were then accompanied by an incessant need to reconstruct what was happening and to give new meaning to everyday life. However, it has to be note how the reflection seems to concern one's own life-world (the individual needs and/or challenges) and does not extend to the wider social system (it is a look “inside”, more than outside); in this sense, it is a self-referential perspective in some sense, which frames the pandemic crisis and related health measures in terms of impacts and perturbations on their day-to-day life (more than as something that stands for the challenges posed by the pandemic to the wider social system and global scenario). A speculative hypothesis is that the introspective position related to one's staying at home was favoured by the feeling/emotional stance of being able to count on a thoughtful caring “father” (the government) committed outside the home to addressing the enemy and the challenges that it poses (cf. Falcone et al., 2020): citizens wouldn't have to take care of anything but suspending their hectic life and taking care of themselves. This suggestion is consistent with the research on the lockdowns implemented in Western Europe in March and April, which concurrently found an association between lockdowns and greater trust in government (Bol et al., 2021), and the suggestion of Wong and Jensen (2020) that public trust may lead also to underestimate the need of individual action.

The diaries collected in the second and third temporal phase, namely the months characterized respectively by the decrease of the infection curve and the end of stay-at-home measures and the beginning of the second wave, issues concerning the socio-economic impact of the crisis have been brought to the fore along with the expectation of returning to normality as soon as possible. Here, the government makes decisions on its own, appears unfriendly and therefore not qualified. This shift in the connotations of government is not surprising but reveals the affective stance of the previous position. Indeed, as Falcone et al. (2020) observed, the high levels of trust in public authorities expressed by Italian population during the early stages of the emergency (March 2020) were a “true anomaly”, in sharp contrast with both long-term trends and recent surveys on institutional trust in Italy, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors argue that this novel institutional trust should be considered on the one hand a cognitive instance – of having first the need to trust those authorities and then preserve the consistency of their own beliefs by assuming that these authorities would manifest the qualities required to warrant that trust – and on the other hand an emotional stance to face uncertainty and gaining a subjective sense of safety. As such, the belief that public authorities would prove themselves worthy of their trust is a very fragile belief, because it is hard for institutions to prove themselves equal to the task at hand. Based on our analysis, in the second and third temporal phase, the construction of a negative they (the government, other untrustworthy citizens) is contrasted with the construction of an opposing we, being the poor powerless people; opposing demands and reproaches coexist and are put forward against the political class: not protecting responsible citizens from others (citizens) who do not respect the rules and imposing unsustainable limits to people's freedom. The social fatigue emerging here is not surprising. As the same WHO (2020) observe, after the very first stage of the crisis, the perceived loss related to pandemic restrictions such as losing job or income, can be higher than the perceived loss related to the virus itself and if the need of support is not well acknowledged and addressed, people may very well lose motivation to comply with COVID-19 initiatives, policies or communication. Based on our analysis, here the desire to return to normality is brought to the fore. We use the term “desire” in a semiotic sense: to desire consists of keeping psychologically alive a certain version of the self/world, regardless of the changes occurring in the real world (Salvatore and Venuleo, 2017). So conceived, the desire to return to normality, thus to the pre-rupture semiotic scenario, does not allow people to fully cope with the complexity of the crisis scenario, being encapsulated with respect to the information about the variation that has taken place in the reality. In the specific case of Italy, we know that the collective desire to believe that “the war against the virus” had been won and it was possible to return to “normality” which circulated at the end of May until September 2020 was associated to a weakness of reliance on public authorities and a global reduction of compliance (Nese et al., 2020); although other multiple factors can be evoked, it is plausible that the people’ desire to go back to normality played a significant role in the new increasing of the contagious and the further need for restrictive measures.

According to our hypothesis, the local adjustment of the citizens' semiotic patterns characterizing the diaries collected in the first phase and the following two can be understood as the by-product of the few changes occurred in the social-cultural scenario: e.g. the social fatigue related to the measures of physical distancing and restriction of mobility established by the Government (WHO, 2020), the lower coordination and the higher political conflicts between government and regions paving the way for considerable uncertainty for citizens (Malandrino and Demichelis 2020), the socio-economic impact of the breakdown (Sanfelici, 2020), the conflicting communication on vaccine distribution and efficacy to the general public (Lin et al., 2021) and so on. Yet, as noted above, at a deeper, structural level, the perspective emerging from the diaries collected in the second and third phases is only apparently in discontinuity with the self-referential perspective of the first phase. One can notice that a low sense of the interweaving between personal and public spheres emerges in both cases: the public sphere is represented as something that, for better or worse, is in the hands of a (reliable or rigid) entity (the government) and the private sphere as a result of this entity's decisions and measures (which either limit citizens' movements or not, either control the respect of the health measures or not, and so on). Consider the meaning of staying at home. As the media and daily life discourses highlighted, the commitment of Italian people to the self-isolation measure was organized by the prevailing fear of being mortally infected and the emotional connotation of the lockdown as individual/family protection, much more than on a commitment of “common good”. The Italian study of Carlucci et al. (2020), conducted during the third week of the national lockdown, offer empirical evidence to the last statement. The authors found that ethical reasons for complying with quarantine measures were most uncommon among the participants: only the 0.1% say that they complied with quarantine to be “good citizens” or to do their “civic duty”, and only 2.3% take protective behaviours for social norms toward COVID-19 prevention (e.g., agreement on the statement “other people at home or at work already follow measures to prevent against COVID-19”). From this perspective, the “free-for-all” discourses and related behaviours spreading in mid-spring can be conceived not as the citizens' “surprising” sudden blindness toward the collective interest, but as another way of enacting the same auto-referential position in evaluating what had to be done for one's well-being. In the same vein, the desire to have one's freedom back and the enactment of living styles claiming performatively that life has to return to normality do not contradict, but highlights, in a different form, the foregrounding of one's daily feelings and routines and the lack of discourses concerning what was happening outside the front door which characterize the diaries collected in the first phase.

The fact that the common good seems not to be a salient regulator of people narratives throughout the period considered is not surprising. According to the interpretative standpoint of SPCT, people make sense of the pandemic scenario through the mediation of the semiotic resources available within their cultural milieu. Within this premise, two orders of considerations can be advanced.

The first concerns the wider contemporary socio-cultural landscape which seems to characterize the western societies before the COVID-19 pandemic. Different analyses have highlighted how the current social scenario is characterized by a deep rupture of civil engagement, collective action and institutional regulation (Russo et al., 2020; Salvatore et al., 2021) and when the perception of a shared common destiny is low, is expected that self-referential way of thinking and behaving re-emerge in the brief period (Ntontis et al., 2020; Venuleo et al., 2020b) (e.g. behaviours foregrounding individual needs with respect of institutional norms).

The second consideration concerns the role of the way the crisis was managed at an institutional level and signified by communicative practices and discourses, which must be critically recognised in relation to the sensemaking trajectories that our analysis allows us to depict. Indeed, media and institutional discourses play a main role in suggesting what a singular event like the pandemic consists of, why it became a disaster, who was responsible, and what should be done or learnt, by whom (Fischer, 2000; Vasterman and Ruigrok 2013). Here, we confine ourselves to considering three elements which characterize the practices and discourses in the public sphere.

First, the focus on the health emergency. Italian Governments and health authorities informed citizens of the seriousness of the epidemic and recommended responsibility in avoiding all unnecessary risks for infection; the media alarm, uncertainty about the ways the virus spread, the inadequacy of the health system's resources and the overload of hospitals contributed to the global feeling of fear, a vital factor in coping with the emergency (Barrett et al., 2001; Coombs et al., 2007), as already found among other populations during previous pandemics such as the SARS (Hsu et al., 2006) and H1N1 pandemics (McVernon et al., 2011). Yet on the other hand, the emergency mode focusing on the health risks outweighed other urgent issues, as those to pollution and climate change (Coccia, 2020b; Rovetta, 2021), and reduced the complexity of the crisis landscape; a complexity that emerged later, with the social and economic impact of the crisis, which dramatically weakened the idea that “everything will be fine”, initially embraced, later re-signified as a statement overlooking the difficulties.

Second, the lack of a temporal perspective longer than a few weeks: it is recognised that Nations and their institutions have to prepare long-run strategies and that specific plans of crisis management established before the emergence should be adopted to guide timely processes of decision-making and to support the application of effective actions and interventions for solving consequential problems in society (Coccia, 2021c; Groh, 2014). Anderson et al. (2020) stressed the point that if people think that they are or soon will be returning to normal, their actions may favour the onset of a new wave of the outbreak. In contrast, in Italy “returning to normality” has become everyone's aspiration, the leitmotif of every government communication, and a message quickly picked up and echoed by commercial advertising” (Emiliani et al., 2020, 9.3). It is likely that the same short time of the health measures established by the government's decrees in the first phase favoured the idea that the end of the “war” against the virus was near; and it is likely that the violation of this expectation, the emergence of the social and economic impact of the crisis and the beginning of the second wave were interpreted as a sign of the government's incompetence, more than of the complexity of the challenges posed by the pandemic. In actual fact, the government itself seemed to fall into a short term strategy, blind to the predictable impact of neighbouring countries where the pandemic started later, the need of institutional efforts of trans-national coordination of socio-sanitary policies (e.g., in fields like scientific and pharmaceutical research, health organization, regulation of frontiers, transportation), the very critical issues behind the restrictive measures adopted to tackle the pandemic (e.g., risk of generalized economic recession, large increment of public debt, destruction of jobs; possible weakening of the EU) (Remuzzi and Remuzzi, 2020).

Third, a paternalistic attitude toward the citizens, constructed as unarmed and passive: they were seen, at the best, as persons to support in terms of the subjective impact produced on them by the crisis (e.g., distress, fear and depressive states, or economic difficulties to resolve though subsidiary measures) rather than a strategic target to empower because of their being the drivers of the crisis management (Venuleo et al., 2020b); and this would have meant (or would mean in the brief period) not only working to sustain the awareness of the interweaving between individual and public interest and effort in the fight against the virus, but also to overcome a view of the citizens as “needy with needs established from above”, in favour of a view of them as thinking actors, with whom to construct a dialogue and build solutions. The study of Coccia (2021d) reveals that resilient systems to pandemic/environmental shocks have to be based on good governance structures associated with adequate and effective leadership that engages with communities and adapts to population needs. The public are more likely to take appropriate action and accept the recommended treatment plan if they feel they can make a difference as individuals and are involved in the decision-making process (e.g., Habersaat et al., 2020; Holmes, 2008; Toppenberg-Pejcic et al., 2019). Consider the problem of vaccine hesitancy: as observed by Palamenghi et al. (2020), adopting a top-down “teaching” recommendation and explaining the reason for getting vaccinated is not enough to involve the public in a scientific request. It is necessary to open a debate that allows concerns from the public to be expressed and thus properly addressed. It is necessary, earlier, to make a serious effort to enhance the feeling of mutual trust and cooperation between institutions and citizens; a complex goal that cannot be pursued in the short term and with an emergency strategy.

6. Conclusion

Some limitations of the present study needed be acknowledged. First, attrition rates were high. Previous questionnaire-based longitudinal studies attested an attrition rate of 40–48% (Aitken et al., 2017; Deary et al., 2003), and a recent daily diary study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic to explore adolescents' mood, empathy, and pro-social behaviour (Van de Groep et al., 2020) reports an attrition of 23–28%. There are several factors that could explain the high attrition in this study. First, the complexity of the task required: to our knowledge, this is the first study to adopt written diaries based on an open stimulus and to provide a six-month follow up period in the COVID-19 pandemic. Responding to an open stimulus requires more commitment and time than filling in a check list; furthermore, it is likely that motivation and interest to write the diary weakened over the time; the many changes in the lives of respondents that occurred between the first phase of diary collection, coinciding with the lockdown measures, and the followings stages where competing life demands may have been intervened, probably play a role in the participants' drop-out. Since, by definition, qualitative longitudinal studies depend on respondents’ continued participation, incentives to complete the work successfully can be substantial (Hermanowicz, 2013); however, this research project was not funded. Finally, some e-mail reminders did not reach their destination, due to spam and junk mail problems.

A second limitation is related to the online collection: although in a COVID-19 era, remote data collection is needed to achieve high participation and inform the response to the pandemic and other public health issues, online surveys can overrepresent higher-income, urban populations with higher literacy and access to smartphones and/or the Internet (Hensen et al., 2021).

Third, the choice of recurrent cross-sectional design did not allow us to capture dissimilarities in the individual trajectories of the sensemaking; this kind of analysis is our next goal.

Fourth, we have not presented data on the relationship between people's sensemaking processes and their attitude to compliance with health measures. On the one hand, it is speculatively based on the SPCT frame guiding the study and findings from previous research studies highlighting the impact of people's sensemaking on their attitudes and capacity to enact adaptive responses, as well as the crucial role of dimensions such as social capital and sense of community for collective and proactive responses to collective emergencies; on the other hand, findings from recent studies report decreasing levels of compliance toward health measures and, though only indirectly, support the idea that the interpretative categories adopted by people to make sense of the crisis scenario were not able to represent the systemic dimension of the crisis; an aspect which – we have argued - plays a crucial role in supporting compliance in the medium term. In any case, other factors need to be considered for a more comprehensive analysis of people's difficulty to maintain compliance with institutional responses in the medium term: e.g. perceived personal vulnerability to infection and perceived severity of the disease (Bish and Michie, 2010; Yıldırım et al., 2021), perceived self-efficacy and efficacy (Scholz and Freund, 2021), trust in government, science, and medical professional (Schneider et al., 2021), trust in formal (government/media) information (Figueiras et al., 2021).

Despite the limitations, our study deserves attention on a theoretical plan and practical level. On a theoretical level, the study highlights how the analysis of people sensemaking – in the case, the analysis of their personal accounts of the pandemic crisis – may offer insight on the reasons guiding their ways to cope and react to the circumstances and challenges. Our longitudinal cross-sectional analysis allows to observe that, despite the differences that occurred over time in the ways of viewing the pandemic crisis, a low sense of the interweaving between personal and public sphere, individual and institutional responses to the crisis emerged throughout the six months considered; a split that, we speculated, can explain the decrease of compliance that took place at the end of the first wave and through to the beginning of the second wave in Italy.

On the plane of health and social policy, recognizing that people’ s interpretative categories are a powerful semiotic organiser of the mind orienting the way they feel, think and relate to preventive measures, entails also to recognize that – in absence of attention to the citizens' position and semiotic activity – such a powerful organiser ends up working as an external and out-of-control element, decreasing the authorities' capability to promote the adoption of the measures assumed. Governments and health authorities in Italy and worldwide recommended that citizens take responsibility in avoiding all unnecessary risks of infection. However, knowledge of the risk and the health recommendations cannot be enough to regulate citizens’ behaviour in the medium-long term. Citizens have to think beyond their own interests and their primary bond, and to integrate the reference to an abstract common good into their mindsets, as a salient regulator of their way of feeling, thinking and acting. The promotion of the psychosocial resources to sustain this complex socio-cognitive task should be considered a strategic aim of institutional action, on a par with that of economic, infrastructural, and institutional resources.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Tiziana Marinaci: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Claudia Venuleo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Alessandro Gennaro: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Gordon Sammut: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in the study, and Roberta Licci, Laura Piccirillo and Cosimo Gabriele Semeraro, for their precious collaboration on data collection.

References

- Aitken L.M., Rattray J., Kenardy J., Hull A.M., Ullman A.J., Le Brocque R., Mitchell M., Davis C., I Castillo M., Macfarlane B. Perspectives of patients and family members regarding psychological support using intensive care diaries: an exploratory mixed methods study. J. Crit. Care. 2017;38:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allington D., Dhavan N. Centre for Countering Digital Hate; 2020. The relationship between conspiracy beliefs and compliance with public health guidance with regard to COVID-19.https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/127048253/Allington_and_Dhavan_2020.pdf Retrieved August 19, 2021, from. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews M. Cambridge University Press; 2007. Shaping History: Narratives of Political Change. [Google Scholar]

- Askitas N., Tatsiramos K., Verheyden B. Estimating worldwide effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 incidence and population mobility patterns using a multiple-event study. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81442-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargain O., Aminjonov U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J. Publ. Econ. 2020;192:104316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L.F. Solving the emotion paradox: categorization and the experience of emotion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006;10(1):20–46. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L.F., Gross J., Christensen T.C., Benvenuto M. Knowing what you're feeling and knowing what to do about it: mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognit. Emot. 2001;15(6):713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Benzécri J.P. Vol. 2. Dunod; 1973. (L'analyse des données [Data Analysis]). [Google Scholar]

- Bertaux D. Sage; 1981. Biography and Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bish A., Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: a review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):797–824. doi: 10.1348/135910710X485826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bol D., Giani M., Blais A., Loewen P.J. The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: some good news for democracy? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2021;60(2):497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovi F., Andrieu E. Bowling together by bowling alone: social capital and Covid-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;265:113501. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner J.M., Mindermann S., Sharma M., Johnston D., Salvatier J., Gavenčiak T., Stephenson A.B., Leech G., Altman G., Mikulik V., Norman A.J., Monrad J.T., Besiroglu T., Ge H., Hartwick M.A., The Y.W., Chindelevitch L., Gal Y., Kulveit J. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science. 2021;371(6531) doi: 10.1126/science.abd9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. The narrative construction of reality. Crit. Inq. 1991;18(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarelli G., De Nicola R., Petrocchi M., Pratelli M., Saracco F. Flow of online misinformation during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. EPJ Data Sci. 2021;10(1):34. doi: 10.1140/epjds/s13688-021-00289-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]