Abstract

Objective:

A retrospective cohort study investigated the association between having surgery and risk of mortality for up to five years and if this association was modified by incident End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) during the follow-up period.

Summary Background Data:

Mortality risk in individuals with pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease (CKD) is high and few effective treatment options are available. Whether bariatric surgery can improve survival in people with CKD is unclear.

Methods:

Patients with class II and III obesity and pre-dialysis CKD stages 3 – 5 who underwent bariatric surgery between 1/1/2006 and 9/30/2015 (n = 802) were matched to patients who did not have surgery (n = 4,933). Mortality was obtained from state death records and ESRD was identified through state-based or healthcare system-based registries. Cox regression models were used to investigate the association between bariatric surgery and risk of mortality and if this was moderated by incident ESRD during the follow-up period.

Results:

Patients were primarily women (79%), non-Hispanic White (72%), under 65 years old (64%), who had a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (59%), diabetes (67%) and hypertension (89%). After adjusting for incident ESRD, bariatric surgery was associated with a 79% lower 5-year risk of mortality compared to matched controls (HR = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.14-0.32; p < .001). Incident ESRD did not moderate the observed association between surgery and mortality (HR = 1.59; 95% CI 0.31-8.23; p = .58).

Conclusions:

Bariatric surgery is associated with a reduction in mortality in pre-dialysis patients regardless of developing ESRD. These findings are significant because patients with CKD are at relatively high risk for death with few efficacious interventions available to improve survival.

Mini-Abstract

Bariatric surgery was associated with a 79% lower 5-year risk of mortality compared to matched controls. Incident ESRD did not moderate the observed association between surgery and mortality. These results challenge the obesity paradox and support the use of bariatric surgery to improve the survival of patients with pre-dialysis CKD.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 15% of adults worldwide1,2 and is associated with reduced life expectancy. Compared to the general population, the independent risk of death is 490% higher in individuals with advanced CKD.3 Unfortunately, few therapies have been shown to reduce mortality in these individuals. Obesity may be a major contributor to lower survival in people with CKD especially in countries like the US;4,5 primarily because it may accelerate the progression of pre-existing CKD and/or give rise to systemic cardiovascular conditions.6-10 However, the link between obesity and mortality in people with CKD is controversial. In multiple observational studies with patients having advanced CKD, the presence of obesity has been associated with increased survival; a phenomenon known as the obesity paradox.11 Controversy over whether obesity increases or lowers risk of death is a major impediment to optimizing management of this disease state12 and consequently improving poor outcomes.

One way to resolve this uncertainty is to study outcomes after bariatric surgery. In patients without kidney disease, bariatric surgery is associated with a 41% reduction in long-term mortality.13 Bariatric surgery is also linked to reduced risk of development and progression of CKD.14-22 Recently Sheetz and colleagues reported that all-cause mortality rates for patients with class II and III obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) on dialysis were 31% lower for those who underwent bariatric surgery compared to matched controls receiving usual care.23

In order to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of bariatric surgery as well as optimize cost savings for health systems, patients should ideally have bariatric surgery before they develop severe end-organ damage needing dialysis and/or long-term insulin use.17,22 To our knowledge, there are no published studies on the effect of bariatric surgery for mortality in the high-risk population of patients with class II and III obesity and CKD who do not yet require dialysis.

The current study was designed to address this major gap in the literature and extend the findings of Sheetz and colleagues23 into the much larger pre-dialysis CKD population. We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis that included a large contemporary population of patients with class II and III obesity and pre-dialysis CKD stages 3 – 5 who had bariatric surgery. These patients were matched to similar patients who did not have surgery. We hypothesized that patients undergoing surgery would have lower mortality compared to patients who did not have surgery and that the relationship between surgery and mortality would be modified by incident end stage renal disease (ESRD) defined as dialysis or transplant.

METHODS

Study Design

The design was a retrospective observational matched cohort study. Patients who had bariatric surgery between 1/1/2006 and 9/30/2015 served as cases and non-surgical controls were matched up to 10:1 using the surgical date as the index date. All data for the study were obtained from patient electronic medical records and electronic billing claims for outside services for the whole period before and after a patient’s surgery or index date until the study end period of 9/30/2015. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all healthcare systems and did not require signed consent because it was a retrospective observational study.

Participants and Settings

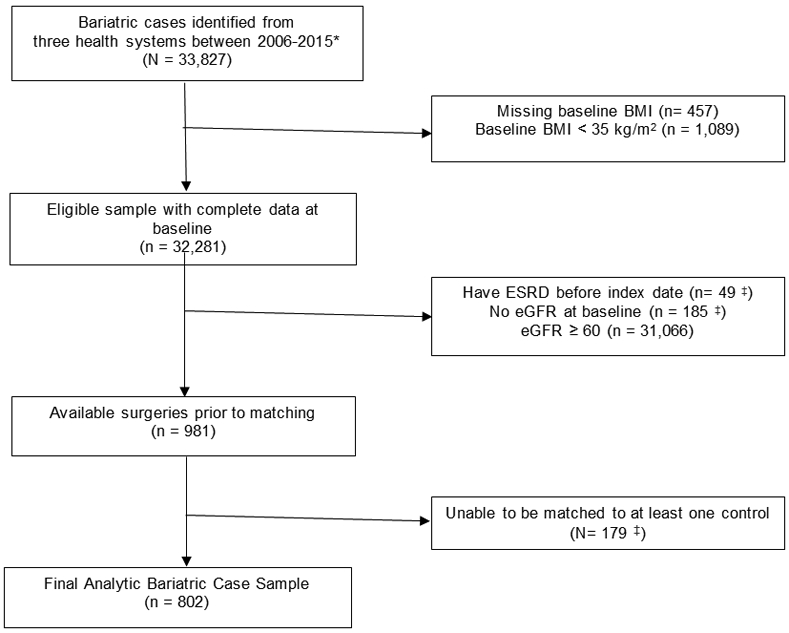

Participants came from three large integrated healthcare systems in the states of California and Washington. Figure 1 presents the bariatric surgery case selection process for the study. In general, eligibility for weight loss surgery in these healthcare systems was based on national requirements.24 After obtaining this surgical cohort (n = 33,827), patients were excluded who either did not have a BMI before surgery (n = 457) or whose baseline BMI was < 35 kg/m2 (n = 1,089). Further exclusions were applied to this sample (n = 32,281) to obtain the pre-dialysis CKD stage 3 – 5 cohort: 1) having no estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measure in the year before surgery (n = 185); 2) having CKD stage 1 or 2 defined as two eGFR measurements ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at least 90 days apart (with no intervening values < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) within a year of surgery (n = 31,066); and having ESRD, defined as dialysis and/or kidney transplant, within 5 years prior to surgery (n = 49). This left 981 bariatric surgical cases with pre-dialysis CKD stages 3 – 5 for matching.

Figure 1. Bariatric case selection process.

*Adults age 21-79 years old who had a primary bariatric surgical procedure (Sleeve gastrectomy, adjustable gastric band, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) between 1/1/2006 - 9/30/2015. Bariatric procedures were identified using a combination of bariatric registries, chart reviews, ICD-9 codes (43.89, 44.31, 44.38, 44.39, 44.68, 44.69, 44.95), and CPT procedure codes (43633, 43644, 43645, 43659, 43775, 43842, 43844, 43845, 43846, 43847, 43770, S2082). We excluded patients with the following: (a) less than one full year of continuous enrollment, (b) all patients who had a diagnosis of cancer (excluding non-melanomatous skin cancer) in the year leading up surgery, (c) a bariatric operation on the same day as an emergency department visit, and/or (d) pregnancy in year prior to surgery.

‡Some surgical patients (n = 179; 18% of surgery patients) were unable to be matched to any non-surgical patients on site, age, BMI, diabetes status, insulin use, use of ACE or ARB medications, hypertension diagnosis, race/ethnicity, chronic kidney disease category, and gender.

BMI = body mass index; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker

We matched controls to these patients using methods we have published in several previous studies.20,25,26 We selected non-surgical controls using the surgery date for cases as the index matching date and the following explicit categorical criteria at the time of the index date: healthcare system; age groups (< 55, ≥ 55 years old); gender (male, female); BMI categories (35 - 39.9, 40 - 49.9, ≥ 50 kg/m2); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other); stage of CKD using eGFR (<15, 15 - 29.9, 30 - 59 mL/min/1.73 m2); and use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and/or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). History of T2DM, hypertension, and insulin use (yes/no) in the year prior to the index date were also used as matching criteria.

We then proceeded to choose up to 10 non-surgical matches for each surgical patient by selecting those with the shortest Mahalanobis distance27 using the following continuous variables: age, BMI, Elixhauser score (overall comorbidity burden),28 and days of healthcare use 7-24 months prior to the index date (seven months was chosen because most bariatric patients had increases in healthcare utilization in these systems six months before surgery for education and pre-operative medical optimization).

Matches could not be found for 179 (18%) of the surgical patients primarily because they could not be matched for race/ethnicity, insulin use, and T2DM status. Once matching was completed, there were 802 surgical and 4,933 (average 6:1 match) nonsurgical control patients (total analytic sample n = 5,735) with class II and III obesity, CKD stages 3–5, and no evidence of ESRD in the five years before surgery or matched control index date.

Outcomes

Date of death was obtained from state death records. ESRD was defined as the first date of hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplantation identified through state-based or healthcare system-based registries.

Covariates

Serum creatinine was used to calculate eGFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD- EPI) creatinine equation.29 Serum creatinine levels were adjusted for analyses depending upon the whether or not the original measurement assay was IDMS-traceable. Proteinuria at time of surgery or index date was staged using the urine albumin-to-creatine ratio (mg/g) as recommended by standards in the field: Stage A1 was <30, Stage A2 was 30-300, and Stage A3 was >300,30 dyslipidemia and T2DM were determined using a combination of diagnosis codes, lab values, and medications;17,20 retinopathy, neuropathy, diagnosed hypertension, and coronary artery disease were determined using ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes; and uncontrolled hypertension was defined as two blood pressures of ≥ 140/90 mmHg at least one day apart within 1 year before surgery or index date. The Elixhauser comorbidity index was calculated using a standard equation.28

Analysis

Preliminary analytic methods. Originally the primary aim of the study was to assess the association between bariatric surgery and incident ESRD, with mortality viewed as a secondary outcome. The Statistical Appendix outlines the preliminary analyses that were done with incident ESRD as the primary outcome. However, it became clear that the mortality rate was so much lower than anticipated for bariatric surgery patients in comparison to matched control patients that we were unable to fit a model of ESRD incidence (which was also very low) after accounting for the competing risk of mortality (see Statistical Appendix). Thus, we shifted the primary outcome to mortality rate and used incident ESRD as a moderating variable in the analyses.

Final analytic methods. Patients were followed up to five years from date of surgery (surgical cases) or index date (matched controls). Follow-up was censored at the end of continuous membership, end of 5-year follow-up, or end of the study period (09/30/15). Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics were reported using percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables (see Table 1). Descriptive statistics were also used for the causes of death for cases and controls (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for bariatric surgical cases and up to 10:1 matched controls. Differences between cases and controls are presented using standardized mean difference (SMD). Cases and controls are well matched if SMD < 0.10 and poorly matched if SMD ≥ 25. All variables were assessed at the date of surgery for cases or matched index date for controls.

| Matched (n = 4,993) |

Surgery (n = 802) |

SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity % (n)* | 0.14 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 73.1% (3,650) | 66.7% (535) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13.2% (661) | 15.3% (123) | |

| Hispanic | 13.7% (682) | 18.0% (144) | |

| Men % (n)* | 21.0% (1,051) | 21.7% (174) | 0.02 |

| Year of Surgery/Matched Control % (n)* | 0.15 | ||

| 2006/2007 | 6.1% (303) | 8.5% (68) | |

| 2007/2009 | 16.3% (815) | 17.6% (141) | |

| 2009/2011 | 26.3% (1,312) | 29.1% (233) | |

| 2011/2013 | 28.2% (1,410) | 26.3% (211) | |

| 2013/2015 | 23.1% (1,153) | 18.6% (149) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (mean ± sd) | 41.84 ± 6.05 | 43.67 ± 6.30 | 0.30 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) % (n)* | 0.25 | ||

| 35.0 - 39.9 kg/m2 | 42.4% (2,119) | 31.9% (256) | |

| 40.0 - 49.9 kg/m2 | 47.9% (2,390) | 52.6% (422) | |

| ≥ 50 kg/m2 | 9.7% (484) | 15.5% (124) | |

| Age (years) (mean ± sd) | 63.5 ± 7.3 | 60.1 ± 6.9 | 0.47 |

| Age 65 - 79 Years Old % (n)* | 37.3% (1,863) | 28.1% (225) | 0.20 |

| eGFR 30 – 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 % (n)* | 96.3% (4,808) | 93.5% (750) | 0.13 |

| eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 % (n) | 3.7% (185) | 6.5% (52) | 0.25 |

| Proteinuria Stage A2/A3 % (n)* | 33.4% (1,670) | 36.7% (294) | 0.07 |

| T2DM % (n)* | 66.1% (3,302) | 70.8% (568) | 0.10 |

| Taking Insulin % (n)* | 35.0% (1,750) | 40.5% (325) | 0.11 |

| Retinopathy % (n) | 20.9% (1,043) | 24.9% (200) | 0.10 |

| Neuropathy % (n) | 27.5% (1,374) | 29.3% (235) | 0.04 |

| Use of ACE Inhibitor % (n)* | 46.9% (2,341) | 50.1% (402) | 0.07 |

| Use of ARB % (n)* | 14.7% (736) | 21.2% (170) | 0.17 |

| Other Hypertension Drug Use % (n) | 83.1% (4,148) | 84.2% (675) | 0.03 |

| Uncontrolled Hypertension % (n)* | 7.2% (361) | 8.9% (71) | 0.06 |

| Diagnosed Hypertension % (n)* | 88.9% (4,439) | 91.0% (730) | 0.07 |

| Dyslipidemia % (n) | 73.7% (3,680) | 81.2% (651) | 0.18 |

| Statin Use % (n)* | 62.1% (3,102) | 64.6% (518) | 0.05 |

| Other Dyslipidemia Drugs Use % (n) | 7.4% (371) | 8.2% (66) | 0.03 |

| Coronary Artery Disease % (n)* | 11.3% (562) | 9.2% (74) | 0.07 |

| Self-Reported Non-Smoker % (n)* | 56.8% (2,835) | 54.0% (433) | 0.06 |

| Elixhauser Score ≥ 1 % (n)* | 74.9% (3,739) | 83.3% (668) | 0.21 |

| Days of Healthcare Use** (mean ± sd)* | 6.68 ± 6.29 | 11.00 ± 8.22 | 0.59 |

| Days of Inpatient Hospitalization (mean ± sd)* | 1.63 ± 6.17 | 0.55 ± 2.41 | 0.23 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mean ± sd) | 128.43 ± 15.07 | 128.02 ±15.05) | 0.03 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mean ± sd) | 70.09 ± 10.63 | 70.17 ± 10.05 | 0.01 |

Used as variables in the time-varying covariate Cox model of mortality

7-24 months before surgery/index date.

Table 2.

Mortality rate and causes of death presented for 30-days, 90-days, and years 1 – 5 after date of surgery for bariatric patients (n = 802) or index date for matched controls (n = 4,993). Cause-of-death data are presented for all deaths (n = 29 surgery; n = 490 controls).

| Matched | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Mortality Rate | % (n) | % (n) |

| 30 day | .40% (20) | .62% (5) |

| 90 day | .61% (47) | 1.13% (9) |

| 1 year | 4.15% (209) | 1.50% (12) |

| 1 – 2 years | 7.00% (311) | 2.54% (19) |

| 2 – 3 years | 9.87% (394) | 2.88% (21) |

| 3 – 4 years | 12.82% (461) | 3.71% (25) |

| 4 – 5 years | 14.65% (490) | 4.86% (29) |

| 30-day Causes of Death | n = 20 | n = 5 |

| cancer | 5.0% (1) | 0 |

| cardiovascular | 60.0% (12) | 80.0% (4) |

| diabetes | 0 | 0 |

| kidney | 0 | 0 |

| other | 10.0% (2) | 20.0% (1) |

| unknown | 25.0% (5) | 0 |

| 30- to 90-day Causes of Death | n = 27 | n = 4 |

| cancer | 0 | 0 |

| cardiovascular | 59.3% (16) | 100% (4) |

| diabetes | 3.7% (1) | 0 |

| kidney | 0 | 0 |

| other | 37.0% (10) | 0 |

| unknown | 0 | 0 |

| 90-day to 1-Year Causes of Death | n = 162 | n = 3 |

| cancer | 7.4% (12) | 33.3% (1) |

| cardiovascular | 44.4% (72) | 0 |

| diabetes | 1.2% (2) | 0 |

| kidney | 2.5% (4) | 0 |

| other | 35.8% (58) | 66.7% (2) |

| unknown | 8.6% (14) | 0 |

| 1- to 2-Year Causes of Death | n = 102 | n = 7 |

| cancer | 13.7% (14) | 14.3% (1) |

| cardiovascular | 47.1% (48) | 28.6% (2) |

| diabetes | 2.0% (2) | 0 |

| kidney | 1.0% (1) | 0 |

| other | 25.5% (26) | 42.9% (3) |

| missing | 10.8% (11) | 14.3% (1) |

| 2- to 5-Year Causes of Death | n = 179 | n = 10 |

| cancer | 13.9% (25) | 0 |

| cardiovascular | 28.5% (51) | 70.0% (7) |

| diabetes | 0 | 10.0% (1) |

| kidney | .01% (2) | 0 |

| other | 26.8% (48) | 20.0% (2) |

| unknown | 29.6% (53) | 0 |

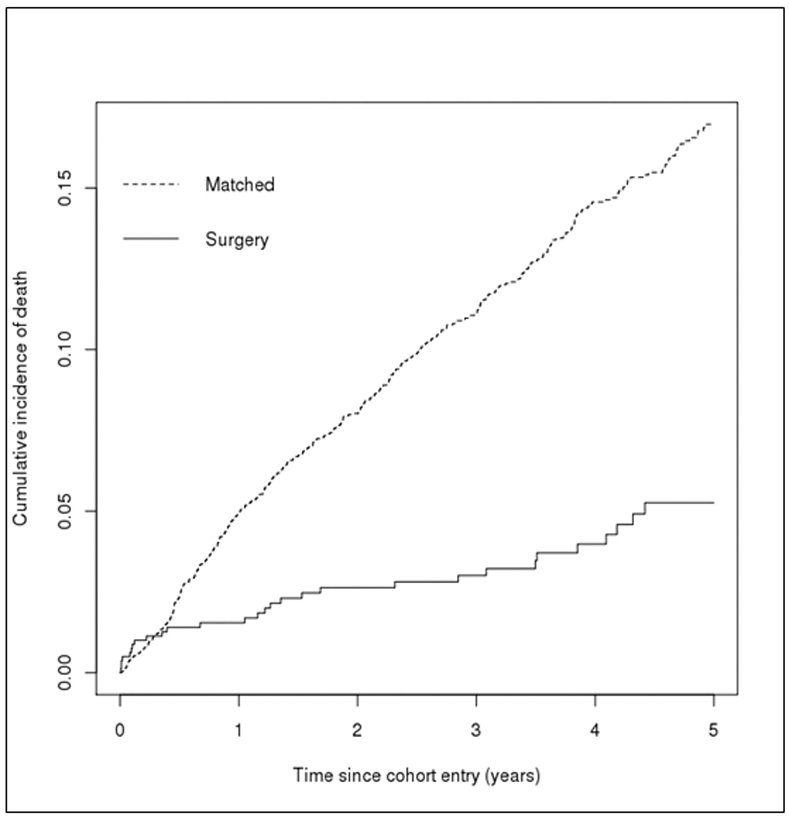

Multivariate imputation by chain equations (MICE)31 was used to impute missing values for race/ethnicity, smoking history, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and proteinuria before any analyses. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to assess the magnitude of the differences between cases and controls for all covariates (see Table 1) after the matching process. A SMD < 0.10 was considered well-matched, ≥ 0.10 to < 0.25 adequately matched, and ≥ 0.25 poorly matched. A Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to compare the unadjusted cumulative incidence of mortality between surgery cases and matched controls (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for the comparison of the unadjusted cumulative incidence of mortality between bariatric surgery cases and matched controls.

For the main analysis, a Cox regression model was used to investigate the association between bariatric surgery and risk of mortality and whether this association was moderated by incident ESRD during the follow-up period. The potential moderating effect of ESRD was investigated by including an interaction term between the surgery indicator and a time-varying indicator of incident ESRD in the model.32 The analysis was adjusted for a range of a priori-specified potential confounders, including those that were used for matching (see Table 1).33 Proportional hazards was assessed using standard methods with weighted residuals.34 Analyses were performed using R 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). As a sensitivity analysis to measure the potential impact of unmeasured confounding, we calculated an E-value for our primary outcome of mortality.35 This value can be interpreted as indicating how large the effect of unmeasured confounding would have to be to negate the observed association between bariatric surgery and mortality.

RESULTS

Participants

Descriptive statistics for surgical cases (n = 802) and matched controls (n = 4,933) for each variable in the Cox model are shown in Table 1. The distribution of surgical operations in the sample was 61% (n = 489) gastric bypass, 36% (n = 288) sleeve gastrectomy, and 3% (n = 25) adjustable gastric band. Almost all surgical case (94%) and matched controls (96%) had an eGFR of 30 – 59 mL/min/1.73 m2. The standardized mean difference (SMD) between surgical cases and matched controls is also shown in Table 1. Almost all variables were well or adequately matched between surgical cases and controls except BMI category (SMD = 0.25), continuous BMI (SMD = 0.30), continuous age (SMD = 0.47), eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (SMD = 0.25), and average days of healthcare use in the 7-24 months before surgery or index date (SMD = 0.59). The average time of follow-up for surgical cases was 3.14 ± 1.7 years (median 3.47; range 0.01 – 5 years) and for matched controls was 2.48 ± 1.75 years (median 2.41; range 0 to 5 years).

Mortality and ESRD

Aside from mortality which was our main outcome, surgery cases were censored for the following reasons: 60% (n = 464) reached the end of the study period, 26% (n = 204) reached the end of the 5-year follow-up, 14% (n = 105) disenrolled from their health plan. In matched controls, 60% (n = 2,718) reached the end of the study period, 17% (n = 772) reached the end of the 5-year follow-up, and 23% (n = 1,018) disenrolled from their health plan. Patients who underwent bariatric surgery had a lower cumulative hazard of dying compared to matched controls (log rank test p <.001; see Figure 2). Mortality cumulative incidence rates for surgical cases and matched controls and the causes of death are shown in Table 2. The overall rate of death was 3.6% (n = 29) for surgical cases and 9.8% (n = 490) for matched controls. In general, causes of death for all patients were primarily cardiovascular or other. Other causes of death included suicide, sepsis, systemic infections, respiratory illnesses, and liver failure.

Table 3 shows results for the Cox regression analyses. Regardless of incident ESRD, surgical patients had an estimated 79% lower risk of mortality compared to matched non-surgical patients (HR = 0.21; 95% CI, 0.14-0.32; p < .001). The E-value for the effect of surgery on mortality was 8.92 (Lower CI: 5.69). Regardless of surgery, patients with incident ESRD had a 78% higher risk of mortality compared to patients without incident ESRD (HR = 1.78; 95% CI, 1.04-3.08; p = .04). There was insufficient evidence of a moderating effect of incident ESRD on the relationship between bariatric surgery and mortality rate (HR = 1.56; 95% CI, 0.30-8.09; p = .60). Incident ESRD in cases (2.9%; n = 23) was primarily due to dialysis, however, 18% (n = 4) had a transplant. All incident ESRD in matched controls (1.5%; n = 74) was due to initiation of dialysis (0% transplants). When incident ESRD was defined as only dialysis (removing the 4 transplant cases; see Table S12 in the Statistical Appendix), there was still no evidence for the moderating effect of incident ESRD on the surgery and mortality relationship (HR = 2.12; 95% CI, 0.39-11.47; p = .39).

Table 3.

Results from the time-varying covariate Cox model to assess the effect of bariatric surgery on mortality in patients with CKD stages 3 – 5. Incidence of ESRD was used as a time varying covariate in the model to test if the effect of surgery on mortality was modified by incident ESRD.

| covariates | HR | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.32 | <.001 |

| ESRD | 1.78 | 1.04 | 3.08 | .04 |

| Surgery*ESRD | 1.56 | 0.30 | 8.09 | .60 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.80 | 0.57 | 1.11 | .19 |

| Hispanic | 0.80 | 0.59 | 1.08 | .15 |

| Men | 1.09 | 0.88 | 1.35 | .44 |

| Year of Surgery 2007/2009 | 1.20 | 0.86 | 1.67 | .29 |

| Year of Surgery 2009/2011 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 1.28 | .57 |

| Year of Surgery 2011/2013 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 0.93 | .02 |

| Year of Surgery 2013/2015 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.56 | <.001 |

| BMI 40 – 49.9 kg/m2 | 1.17 | 0.96 | 1.43 | .12 |

| BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2 | 2.18 | 1.65 | 2.88 | <.001 |

| Age 65 – 79 years | 1.02 | 0.84 | 1.24 | .83 |

| eGFR 30 – 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.91 | .02 |

| T2DM | 1.36 | 1.03 | 1.80 | .03 |

| Taking Insulin | 1.69 | 1.36 | 2.10 | <.001 |

| Use of ACE Inhibitor | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.90 | .002 |

| Use of ARB (% yes) | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.99 | .04 |

| Uncontrolled Hypertension | 1.33 | 0.99 | 1.78 | .06 |

| Diagnosed Hypertension | 1.70 | 1.13 | 2.53 | .01 |

| Statin Use | 1.02 | 0.84 | 1.25 | .83 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 1.67 | 1.35 | 2.07 | <.001 |

| Self-Reported Never Smoked | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.98 | .03 |

| Elixhauser Score ≥ 1 | 2.20 | 1.62 | 2.97 | <.001 |

| Days of Healthcare Use 7-24 Months Before Baseline | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 | .10 |

| Days of Inpatient Healthcare Use 7-24 Months Before Baseline | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.03 | <.001 |

| Proteinuria Stage A2/A3 | 1.66 | 1.37 | 2.01 | <.001 |

The global test of proportional hazard assumption was p = 0.09; HR = hazard ration; CI = confidence interval; BMI = body mass index; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker

DISCUSSION

Patients with class II and III obesity and CKD stages 3 - 5 who underwent bariatric surgery had a 79% lower risk of death over five years compared to matched controls. This was a larger effect than mortality outcomes reported in previous studies of bariatric surgery in patients without CKD13 and a recently published study of patients on dialysis who had bariatric surgery.23 These findings are significant because patients with CKD are at relatively high risk for death with few efficacious interventions available to improve survival.2,3 Our results in patients with pre-dialysis CKD and class II and III obesity in conjunction with the recent findings in patients on dialysis23 demonstrate a long-term survival benefit of bariatric surgery across the broad spectrum of moderate-to-advanced CKD, a condition characterized by exceptional complexity, high morbidity, and poor outcomes.2,36 One reason why the reduction in mortality we found (79%) was much greater than that reported by Sheetz and colleagues23 (31%) may have been that our pre-dialysis study population still had significant residual kidney function and an associated higher life expectancy. This provides further evidence that in order to achieve the most benefit from bariatric surgery patients should undergo this intervention before they experience organ failure.17,37,38

The hypothesis that incident ESRD would modify the relationship between bariatric surgery and mortality in pre-dialysis patients with class II and III obesity and CKD stages 3 – 5 was not supported. Our study was likely underpowered to detect this interaction due to far more individuals dying than reaching ESRD, a phenomenon that is consistent with the natural history of this population.39-41 Larger population-based studies with longer follow-up are needed to confirm these findings.

For all patients in the study who had incident ESRD, bariatric surgery patients were more likely than matched controls to receive a transplant. This was also reported by Sheetz and colleagues.23 Because patients with class II and III obesity and poor kidney function are less likely to receive a transplant than their normal weight counterparts,42,43 bariatric surgery may not only confer lifesaving health benefits and improvements in quality of life but also lead to a higher rate of kidney transplantation, the best available treatment for kidney failure. This may become particularly important under planned physician reimbursement models in the US that are designed to emphasize and reward the use of clinical interventions that improve outcomes in patients with CKD and ESRD.44 In addition we found that early mortality rates at 30- and 90-days were very low; similar to those reported for patients without CKD.45 This suggests that bariatric surgery can be performed safely in these patients.

There were several limitations in the study design that should be considered when interpreting the results. One was that the study had originally focused on incident ESRD as the primary outcome and mortality as the secondary outcome (please see Statistical Appendix), but too few incident ESRD events limited our ability to study this outcome. We did attempt to address this limitation by matching controls and surgical cases up to 10:1 (average 6:1). However, by adding more matched controls we also lowered the likelihood of exact matching. The sample was well-matched on most factors that could have been related to both having surgery and having ESRD and/or mortality (Table 1). However, control patients had lower BMI (SMD = 0.25), were older (SMD = 0.47), were less likely to have an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (SMD = 0.25), and fewer days of healthcare use in the 7-24 months before surgery or index date than surgical patients (SMD = 0.59). To mitigate these possible sources of confounding, we also added these variables as covariates in the analyses of mortality (please see Table 1 for indication of the variables used as covariates). We have used this strategy for most of our bariatric outcome studies to adequately address confounding.20,25,26

We included most major mortality risk factors in our model (e.g., age, smoking, cardiovascular risk factors, Elixhauser comorbidity score, and measures of health care use); however, as with any observational study, unmeasured confounding could still exist. Therefore, we calculated an E value to determine the potential effect of unmeasured confounding on our mortality outcome.35 To negate our main finding for mortality, the effect of the unmeasured covariates would have to be over four times greater (E value = 8.92) than the strongest measured predictors of mortality in our models: BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2 (HR = 2.18; 95% C, 1.65-2.88) and comorbidity burden (HR = 2.20; CI, 1.62-2.97). Thus, we believe it is highly unlikely that our mortality findings could be explained by unmeasured factors that we did not include in our analyses. Another limitation was that the patients in this study were from integrated healthcare settings, some of which had extensive preparation programs for surgery.38,46 Our findings may not apply to single provider surgical practices.

Despite these limitations, our study had several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first study of the impact of bariatric surgery on mortality in pre-dialysis patients with CKD stages 3 – 5. In addition, we included sleeve gastrectomy cases, which is currently the most common bariatric surgery procedure in the US,47 and the ethnic and racial makeup of our patient population represented those who suffer disproportionately from obesity and kidney disease in the US. Furthermore, we used some of the most comprehensive methods to control for confounding in comparative observational studies. Although randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for causal inference, they do not often reflect the routine clinical decision-making, care experience, and outcomes outside of academic medical centers, and they are well-known for under-representing racial/ethnic minorities.48 Together with RCTs, large observational studies can provide important evidence to help providers and patients with CKD make decisions about benefits and risks of bariatric surgery.

Although there is modest perioperative risk in patients with CKD undergoing bariatric surgery than in people who do not have surgery,49 we found a large long-term protective effect of surgery on mortality which could far outweigh this short-term risk. Our results challenge the obesity paradox paradigm11 and support the use of bariatric surgery to improve the survival of patients with CKD and class II and III obesity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the patients who contributed their information to this study without whom the research would not have been possible. This research was funded by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders (NIDDK) award #R01DK105960 granted to Drs. Arterburn and Coleman.

Contributor Information

Karen J. Coleman, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA.

Yu-Hsiang Shu, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA.

Heidi Fischer, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA.

Eric Johnson, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA..

Tae K. Yoon, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA..

Brianna Taylor, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA..

Talha Imam, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Nephrology Department, San Bernardino Medical Center, Fontana, CA..

Stephen DeRose, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Department of Research and Evaluation, Pasadena, CA..

Sebastien Haneuse, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA..

Lisa J. Herrinton, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Division of Research, Oakland, CA..

David Fisher, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Division of Research, Oakland, CA..

Robert A Li, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Department of Surgery, Oakland, CA..

Mary Kay Theis, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA..

Liyan Liu, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Division of Research Oakland, CA..

Anita P Courcoulas, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA..

David H. Smith, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Center for Health Research, Portland, OR.

David E. Arterburn, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA..

Allon N. Friedman, Division of Nephrology Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN.

References

- 1.Levin A, Tonelli M, Bonventre J, Coresh J, Donner J, Fogo AB, et al. Global kidney health 2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care, research, and policy. Lancet. 2017; 390:1888–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Renal Data System (USRDS). U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2018 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351:1296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collaborators GBDO, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377: 13–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang AR, Grams ME, Navaneethan SD. Bariatric surgery and kidney-related outcomes. Kidney Int Rep. 2017; 2:261–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:.254–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuck ML, Sowers J, Dornfeld L, Kledzik G, Maxwell M. The effect of weight reduction on blood pressure, plasma renin activity, and plasma aldosterone levels in obese patients. N Engl J Med. 1981; 304:930–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Agati VD, Chagnac A, de Vries AP, et al. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: clinical and pathologic characteristics and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2016; 12: 453–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AR, Grams ME, Ballew SH, et al. Adiposity and risk of decline in glomerular filtration rate: meta-analysis of individual participant data in a global consortium. BMJ. 2019; 364:k5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vivante A, Golan E, Tzur D, et al. Body mass index in 1.2 million adolescents and risk for End-Stage Renal Disease. Arch Int Med. 2012; 172:1644–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadi SF, Zahmatkesh G, Ahmadi E, et al. Association of body mass index with clinical outcomes in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiorenal Med. 2016; 6:37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Rhee CM, Chou J, et al. The obesity paradox in kidney disease: How to reconcile it with obesity management. Kidney Int Rep. 2017; 2:271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardoso L, Rodrigues D, Gomes L, Carrilho F. Short- and long-term mortality after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017; 19:1223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang AR, Chen Y, Still C, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with improvement in kidney outcomes. Kidney Int. 2016; 90:164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman AN, Wahed AS, Wang J, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on CKD risk. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018; 29:1289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman AN, Wang J, Wahed AS, et al. The association between kidney disease and diabetes remission in bariatric surgery patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019; 74:761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imam TH, Fischer H, Jing B, et al. Estimated GFR before and after bariatric surgery in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017; 69:380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shulman A, Peltonen M, Sjostrom CD, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease following bariatric surgery in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018; 42:964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aminian A, Zajichek A, Arterburn DE, et al. Association of metabolic surgery with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with Type 2 Diabetes and obesity. JAMA 2019; 322:1271–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Brien R, Johnson E, Haneuse S, et al. Microvascular outcomes in patients with diabetes after bariatric surgery versus usual care: A matched cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:300–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liakopoulos V, Franzen S, Svensson AM, et al. Renal and cardiovascular outcomes after weight loss from gastric bypass surgery in Type 2 Diabetes: Cardiorenal risk reductions exceed atherosclerotic benefits. Diabetes Care. 2020; 43:1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen RV, Pereira TV, Aboud CM, et al. Effect of gastric bypass vs best medical treatment on early-stage chronic kidney disease in patients with Type 2 Diabetes and obesity: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020; 155:e200420. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheetz KH, Gerhardinger L, Dimick JB, Waits SA. Bariatric surgery and long-term survival in patients with obesity and End-stage Kidney Disease. JAMA Surg. 2020; 155:581–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NIDDK. Potential Candidates for Bariatric Surgery. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/bariatric-surgery/potential-candidates. Accessed March 7, 2020.

- 25.Fisher DP, Johnson E, Haneuse S, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and macrovascular disease outcomes in patients with Type 2 Diabetes and class II and III obesity. JAMA. 2018; 320:1570–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arterburn DE, Johnson E, Coleman KJ, et al. Weight outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass compared to nonsurgical treatment. Ann Surg. 2020; DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000003826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016; 151:1046–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the elixhauser and charlson/deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care. 2004; 42:355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Eckardt K, et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013; 3(Suppl):1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sv Buuren, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. MICE: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Software. 2011; 45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collett David. Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research. Chapter 8. CRC press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjolander A, Greenland S. Ignoring the matching variables in cohort studies - when is it valid and why? Stat Med. 2013; 32:4696–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994; 81:515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, Arterburn D. Using the E-Value to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding in observational studies. JAMA. 2019; 321:602–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Manns BJ, et al. Comparison of the complexity of patients seen by different medical subspecialists in a universal health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2018; 1:e184852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman KJ, Huang YC, Koebnick C, et al. Metabolic syndrome is less likely to resolve in Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks after bariatric surgery. Ann Surg, 2014; 259:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman KJ, Huang YC, Hendee F, Watson HL, Casillas RA, Brookey J. Three-year weight outcomes from a bariatric surgery registry in a large integrated healthcare system. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014; 10:396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksen BO, Ingebretsen OC. The progression of chronic kidney disease: A 10-year population-based study of the effects of gender and age. Kidney Int. 2006; 69:375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minutolo R, Lapi F, Chiodini P, et al. Risk of ESRD and death in patients with CKD not referred to a nephrologist: A 7-year prospective study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014; 9:1586–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ravani P, Fiocco M, Liu P, et al. Influence of mortality on estimating the risk of kidney failure in people with stage 4 CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019; 30:2219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kienzl-Wagner K, Weissenbacher A, Gehwolf P, Wykypiel H, Ofner D, Schneeberger S. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: Gateway to kidney transplantation. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017; 13:909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segev DL, Simpkins CE, Thompson RE, Locke JE, Warren DS, Montgomery RA. Obesity impacts access to kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008; 19:349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model. 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/kidney-care-choices-kcc-model/. Accessed January 31, 2020.

- 45.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Sledge I. Trends in mortality in bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery, 2007; 142:621–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shafipour P, Der-Sarkissian JK, Hendee FN, Coleman KJ. What do I do with my morbidly obese patient? A detailed case study of bariatric surgery in kaiser permanente southern california. Perm J. 2009; 13:56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. IFSO worldwide survey 2016: Primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg. 2018; 28:3783–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anglemyer A, Horvath HT, Bero L. Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 4:MR000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen JB, Tewksbury CM, Torres Landa S, Williams NN, Dumon KR. National postoperative bariatric surgery outcomes in patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Kidney Disease. Obes Surg. 2019; 29:975–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.