Abstract

Background.

Scar models posit that heightened anxiety and depression can increase the risk for subsequent reduced executive function (EF) through increased inflammation across months. However, the majority of past research on this subject used cross-sectional designs. We therefore examined if elevated generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and panic disorder (PD) symptoms forecasted lower EF after 20 months through heightened inflammation.

Methods.

Community-dwelling adults partook in this study (n = 614; MAGE = 51.80 years, 50% females). Time 1 (T1) symptom severity (Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Short Form), T2 (2 months after T1) inflammation serum levels (C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, interleukin-6), and T3 (20 months after T1) EF (Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone) were assessed. Structural equation mediation modeling was performed.

Results.

Greater T1 MDD and GAD (but not PD) severity predicted increased T2 inflammation (Cohen’s d = 0.21–1.92). Moreover, heightened T2 inflammation forecasted lower T3 EF (d = −1.98 to −1.87). T2 inflammation explained 25–32% of the negative relations between T1 MDD or GAD and T3 EF. T1 GAD severity predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation path was stronger among younger (vs. older) adults. Direct effects of T1 MDD, GAD, and PD forecasting decreased T3 EF were found (d = −2.02 to −1.92). Results remained when controlling for socio-demographic, physical health, and lifestyle factors.

Conclusions.

Inflammation can function as a mechanism of the T1 MDD or GAD–T3 EF associations. Interventions that successfully treat depression, anxiety, and inflammation-linked disorders may avert EF decrements.

Keywords: executive function, generalized anxiety disorder, inflammation, longitudinal, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, scar theory, structural equation model

Executive function (EF) refers to a set of intricate, higher-order, and multi-domain cognitive control systems integral for directing myriad behavioral and cognitive processes (Goldstein & Naglieri, 2014). We depend on our EF domains such as working memory (WM; ability to retain and alter data in real-time) and inhibition (capacity to refrain from autopilot tendencies). EF capacities also help us to effectively plan, attain goals, regulate emotions, make decisions, and resolve conflicts. Relatedly, EF deficits have been associated with problems in school and work performance, social relationships, and mental health in daily life (Alvarez & Emory, 2006; Follmer, 2018; Snyder, Miyake, & Hankin, 2015; Zainal & Newman, 2018). Thus, understanding the factors related to future EF impairment is important.

Allostatic load presents as a key risk factor for subsequent EF decrements. Such allostatic load is defined as the long-term accumulation of chronic, stress-induced, wear-and-tear of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and associated physiological systems (McEwen & Gianaros, 2011). It has also been defined as increased blood serum pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Hostinar, Lachman, Mroczek, Seeman, & Miller, 2015). IL-6 is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by T-cells, non-immune cells, and unique white blood cells (Hartman & Frishman, 2014). It catalyzes the creation of CRP and fibrinogen (acute-phase inflammatory assays concentrated in the liver and associated organs). CRP denotes complex proteins generated by advanced cancer, bodily infection, injury, or trauma (McEwen, 2007). Fibrinogen is a glycoprotein that produces the fibrin enzyme in the liver and is involved in platelet aggregation, such that undue levels of fibrinogen indicate vascular endothelium abnormalities (Petersen, Ryu, & Akassoglou, 2018).

Scar theories propose that greater depression and anxiety symptoms may forecast subsequent worse EF across prolonged timescales via increased allostatic load (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009). Specifically, heightened inflammation is considered a ‘physiological scar’ of prior increased mental disorder symptoms due to prolonged HPA dysregulation (e.g. excessive cortisol) (Pariante, 2017). Moreover, scar theories postulate that elevated depression and anxiety can raise subsequent inflammation levels and impair future EF across years by adversely altering WM, learning, and emotion regulation-related brain areas (e.g. prefrontal cortices, hippocampus, amygdala) (Allott, Fisher, Amminger, Goodall, & Hetrick, 2016; Lucassen et al., 2014). Collectively, scar models theorize that increased depression and anxiety can forecast future elevated inflammation and lower EF across months and years.

Congruent with scar models, diverse studies indicated that greater common psychiatric disorder severity and perseverative cognitions forecasted decline in EF and associated cognitive functioning across years. For example, rise in dispositional negative affect as well as inordinate worry, anxiety, and depression symptoms predicted subsequent decrements in WM, inhibition, processing speed, and episodic memory 3–17 years later in several population-based studies, with small-to-large effect sizes (Bennett & Thomas, 2014; Gimson, Schlosser, Huntley, & Marchant, 2018; Zainal & Newman, in press; Zainal & Newman, 2021). Overall, it is plausible that higher major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and panic disorder (PD) symptoms would precede and relate to lower EF months and years later.

Further supporting scar theories, nine studies evidenced that elevated anxiety and depression were associated with heightened inflammation over several years. Middle-aged adults with greater baseline GAD, PD, and post-traumatic stress disorder severity displayed more growth in high-sensitivity CRP serum levels following 5–16 years (Copeland, Shanahan, Worthman, Angold, & Costello, 2012b; Glaus et al., 2018; Sumner et al., 2017). Likewise, higher depression symptoms coincided with greater upsurge in CRP, fibrinogen, or IL-6 across 2–12 years in ethnic- and age-diverse adult samples (Copeland, Shanahan, Worthman, Angold, & Costello, 2012a; Deverts et al., 2010; Matthews et al., 2007; Niles, Smirnova, Lin, & O’Donovan, 2018; Stewart, Rand, Muldoon, & Kamarck, 2009; Von Känel, Bellingrath, & Kudielka, 2009).

Moreover, at least 18 studies have shown that higher inflammation levels dovetailed with future reduced EF and related cognitive domains. Increased IL-6, CRP, or fibrinogen were independently associated with lower EF, global cognition, language, memory, or spatial reasoning across 3 months and up to 17 years in community-dwelling and patient populations (Gallacher et al., 2010; Krogh et al., 2014; Mooijaart et al., 2013; Weaver et al., 2002; Zheng & Xie, 2018). In a recent meta-analysis, elevated CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 were predictive of future major neurocognitive disorder syndromes (e.g. over periods as long as 25 years; Darweesh et al., 2018) across North America, Europe, and Asia.

Therefore, we aimed to determine if increased MDD, GAD, and PD would predict lower subsequent global EF through elevated inflammation. This focus is valuable for a number of reasons. Our longitudinal study can improve understanding of possible causal relations as it extends prior mostly cross-sectional relations among psychopathology, EF, and inflammation (e.g. Renna, O’Toole, Spaeth, Lekander, & Mennin, 2018). Relatedly, we utilized structural equation modeling (SEM) (vs. manifest regression) methods which reduce measurement unreliability-related error and enhance power (Maslowsky, Jager, & Hemken, 2015). Moreover, the role of CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 has been understudied in the connections among inflammation, psychopathology, and EF (Daniels, Olsen, & Tyrka, 2020). Many countries worldwide are currently experiencing public health and economic challenges related to widespread inflammation-linked neuropsychiatric disorders (Prince et al., 2016; Steel et al., 2014). Our efforts may thus inform the creation and fine-tuning of evidence-based interventions. On the basis of scar theories and data, we predicted that greater MDD, GAD, and PD severity would distinctively forecast increased inflammation after 2 months. Further, we hypothesized that such heightened inflammation would subsequently predict lower latent global EF after 18 months. Also, based on interactive scar models (Majd, Saunders, & Engeland, 2020), we investigated if and how age, gender, education, income, physical health, lifestyle, and medication usage factors moderated these mediation models or potentially functioned as notable covariates.

Method

Participants

This secondary analysis used the publicly available Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) Refresher datasets with three time-points: 2012 [Time 1 (T1)]; 2012 (T2; 2 months after T1); and 2014 (T3; 20 months after T1 and 18 months after T2) (Ryff & Lachman, 2018; Ryff et al., 2017; Weinstein, Ryff, & Seeman, 2019). At T1, participants (n = 614) averaged 51.80 years old (s.d. = 13.40, range = 25–76 years). Females comprised 50.33% of the sample, 49.67% had college education, and all of the participants identified as Whites.

Measures

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix of the primary variables. The present study selected participants who consented to partake in the face-to-face psychiatric interview, biomarker assay procedures, and behavioral EF tests (Love, Seeman, Weinstein, & Ryff, 2010). At T1, participants’ past-year MDD, GAD, and PD symptoms were evaluated. At T2, participants’ inflammation levels were assessed. At T3, a behavioral EF measure was administered. Neither inflammation nor EF was measured at T1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of main study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | ||||||||||||

| 2. Female | −.11** | – | |||||||||||

| 3. T1 MDD SX | −.12** | .11** | – | ||||||||||

| 4. T1 GAD SX | −.07 | .08 | .29*** | – | |||||||||

| 5. T1 PD SX | −.09* | .15*** | .32*** | .23*** | – | ||||||||

| 6. T2 VF | −.20*** | −.011 | −.04 | −.06 | −.07 | – | |||||||

| 7. T2 NS | −.13** | −.16*** | −.12** | −.10* | −.12** | .35*** | – | ||||||

| 8. T2 BC | −.27*** | −.14*** | −.08* | −.08* | −.11* | .34*** | .44*** | – | |||||

| 9. T2 SGST | .05 | −.03 | −.08 | −.09* | −.05 | .13** | .24*** | .22*** | – | ||||

| 10. T2 BDS | −.09* | −.10 | −.11** | −.09* | −.12** | .22*** | .41*** | .36*** | .23*** | – | |||

| 11. T3 IL-6 | .40*** | −.02 | .05 | .09* | .01 | −.24*** | −.22*** | −.23*** | −.04 | −.09* | – | ||

| 12. T3 CRP | .04 | .15*** | .14*** | .09* | .01 | −.14*** | −.17*** | −.13** | −.08 | −.08* | .54*** | – | |

| 13. T3 FGN | .25*** | .12** | .08* | .031 | .05 | −.08* | −.13** | −.17*** | −.08 | −.05 | .45*** | .51*** | – |

| M or n | 51.78 | 309 | 0.78 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 21.41 | 2.80 | 41.60 | 0.98 | 5.21 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 5.81 |

| s.d. or % | 13.44 | 50.33 | 1.88 | 0.97 | 1.24 | 6.21 | 1.47 | 10.84 | 0.03 | 1.52 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.13 |

| Min | 25.00 | – | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.71 | 5.65 |

| Max | 76.00 | – | 7.00 | 10.00 | 6.00 | 44.00 | 5.00 | 90.00 | 1.00 | 8.00 | 1.38 | 1.36 | 5.99 |

| Skewness | −0.16 | −0.01 | 2.18 | 6.84 | 2.81 | 0.20 | −0.15 | 0.28 | −0.76 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Kurtosis | −1.02 | −2.01 | 3.13 | 50.86 | 7.21 | 0.02 | −1.00 | 0.35 | −1.04 | −0.39 | −1.51 | −1.50 | −1.43 |

M, mean; n, number of participants; s.d., standard deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum; BC, backward counting; CRP, C-reactive protein; DBS, digit backward span; FGN, fibrinogen; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; IL-6, interleukin-6; MDD, major depressive disorder; NS, number series; PD, panic disorder; SGST, stop-and-go-switch task mixed task; SX, symptom severity; T1, time 1; T2, time 2; T3, time 3; VF, verbal fluency.

Inflammation serum levels have been log transformed to achieve univariate normal distributions of the data. IL-6 was originally measured in pg/ml, fibrinogen in mg/dl, and CRP in μg/ml.

p ⩽ 0.001;

p ⩽ 0.01;

p ⩽ 0.05.

T1 psychiatric disorder symptom severity

Past-12-month MDD, GAD, and PD severity were measured using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Short Form (CIDI-SF) (aligned with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – Fourth Edition; DSM-IV) (Abel, 1994; American Psychiatric Association, 1987; Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998; Wittchen, 1994). To assess MDD severity, respondents disclosed if they encountered depression symptoms in the past year (seven-item; appetite changes, concentration problems, fatigue, loss of interest, low self-worth, sleep issues, suicidality). To evaluate past-year GAD severity, participants reported the extent they faced symptoms intertwined with excessive worries most days (10-item; concentration problems, easily fatigued, difficulty staying asleep, irritability, low energy, keyed up, mind going blank, muscle tension, restlessness, trouble falling asleep). To measure PD severity, participants stated the degree they experienced panic symptoms in the past 12 months (six-item; accelerated heart rate, chest or stomach discomfort, chills or hot flashes, sense of unreality, sweating, trembling or shaking). The CIDI-SF has demonstrated good specificity (93.9–99.8%), sound sensitivity (89.6–96.6%), and high internal consistency (αs = 0.948–0.989 in this study) (Kessler et al., 1998).

T2 pro-inflammatory cytokine assays

Participants fasted overnight before visiting the laboratory for their biomarker assays to be collected following established operating procedures (Love et al., 2010). The biomarker assays were frozen at −60 to −80°C using dry ice while being shipped to the laboratory where they were deposited for batch assessments every month to ensure standardization across multiple data collection locations (Weinstein et al., 2019). Plasma CRP was assessed with a BNII nephelometer harnessing a particle-enhanced immunonepholometric assay (Dade Behring Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA). Blood serum IL-6 was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine® High-sensitivity ELISA kit #HS600B; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) (Friedman & Herd, 2010). Plasma fibrinogen antigen was quantified with the BNII nephelometer (N Antiserum to Human Fibrinogen; Siemens, Malvern, PA, USA) by an immunochemical reaction alongside using a tailored and partially automated Clauss method (Clauss, 1957). All inflammation concentration values were computed in duplicate. To ensure all assays fell within normality, any inflammation markers >10 pg/ml were rerun in diluted sera (Morozink, Friedman, Coe, & Ryff, 2010). For all inflammation markers, coefficients of variance within- and across-laboratories were within appropriate bounds (1.08–15.66%) (Weinstein et al., 2019).

T3 global executive functioning

The Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone was administered to assess global EF (Lachman, Agrigoroaei, Tun, & Weaver, 2014). It comprised the following five subtests: (1) Backward Counting (correctly counting as many numbers backwards from 100 within 30 s); (2) Backward Digit Span (reiterating backwards number strings of growing size in the accurate order); (3) Category Verbal Fluency (stating as many distinct food or animals within 60 s); (4) Number Series (detecting a pattern and finishing a digit string with the last number accurately); and (5) Stop-and-Go Switch Task (set-shifting and inhibition assessments that consist of rotating blocks of normal and reverse sets). It has demonstrated strong 4-week retest reliability (r = 0.82–0.83) (Lachman et al., 2014), alongside excellent discriminant validity (e.g. rs = 0.16–0.17 with recall tests) and good construct validity (e.g. rs = 0.41–0.52 with unique EF assessments) (Lachman et al., 2014).

Potential moderators or covariates

The following variables were tested as potential moderators or covariates of our mediation models based on previous research (Beydoun et al., 2019; Eyre & Baune, 2012; Friedman & Herd, 2010; Spyridaki, Avgoustinaki, & Margioris, 2016): age, gender (female vs. male), income (i.e. self-reported household total income from pension, social security, wage, and other sources), education status (presence of tertiary education), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), number of past-year chronic health conditions (related to AIDS/HIV, alcohol/drug problem, anxiety/depression, diabetes, dry/sore skin, face rash, gum/mouth, hair loss, hand rash, hemorrhoids, hernia, hypertension, itch, lupus/autoimmune, migraine, neurological disorder, pimples, scaly skin, sleep, stroke, swallowing, sweating, teeth trouble, ulcer, warts), exercise habit (presence of exercise at least 20 min 3 times/week), and medication consumption (i.e. use of antidepressants, anti-hypertensives, anti-platelets, coagulant modifiers, cholesterol medications, coagulant modifiers, gastrointestinal agents, and hormone modifiers) (cf. Table 2 for the descriptive statistics).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of potential moderators or covariates

| M or n | s.d. or % | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household income ($) | 88 028.09 | 67 051.84 | 0.00 | 300 000.00 | 1.14 | 1.41 |

| Body mass index | 28.83 | 6.96 | 16.82 | 66.26 | 1.43 | 3.35 |

| Number of chronic illnesses | 1.77 | 1.75 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 0.73 | −0.57 |

| Number of prescription medications | 2.76 | 3.55 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 1.68 | 3.54 |

| Tertiary education (%) | 405 | 65.96 | – | – | −0.36 | −0.67 |

| Smoker (%) | 260 | 42.35 | – | – | 0.31 | −1.91 |

| Physical exercise (at least 3×/week) (%) | 466 | 75.90 | – | – | −1.21 | −0.53 |

M, mean; n, number of participants; s.d., standard deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum.

Data analyses

Following best practices, the inflammatory markers blood concentration levels were log-transformed (Hostinar et al., 2015). Further, outliers were Winsorized (i.e. anomalous values were replaced with the 99th percentile value of that specific variable) (Liao, Li, & Brooks, 2016). To this end, the descriptive statistics of all EF and inflammation item indicators were within normal limits (skewness = −0.15 to −0.28; kurtosis = −1.51 to −0.35).

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and mediation SEM analyses using the lavaan R package (Rosseel, 2012) with RStudio (Version 1.3.959). To reduce measurement error and increase power (Tomarken & Waller, 2005), we formed a latent T2 inflammation composite by treating each CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 marker as manifest indicators in a CFA, similar to Hostinar et al. (2015). Further, based on a psychometric validation study (Lachman et al., 2014), a latent EF construct was formed. To assess model fit, we used the χ2 goodness-of-fit statistic alongside the confirmatory fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990). Maximum likelihood with robust standard error estimators was used to accommodate any non-normality in the data (Li, 2016). In addition, we used a product-of-coefficients (a × b) of the indirect effect method. Specifically, we performed mediation analyses for the regression coefficients of T1 MDD, GAD, or PD symptom severity predicting T2 inflammation (a path), and T2 inflammation forecasting T3 EF (b path), over and above the direct effect (c′ path; T1 disorder severity–T3 EF relation). Further, we used bootstrapping with 10 000 resampling draws (Deng, Yang, & Marcoulides, 2018) and reported the unstandardized regression coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The ratio of the indirect affect (a × b) to the total effect, c = a × b + c′, constitutes the mediation effect size (percentage of variance that the T2 inflammation mediator explained the T1 disorder severity–T3 EF association) (Wen & Fan, 2015).

Following recommendations (Jacobson & Newman, 2014; Maslowsky et al., 2015), we tested whether and how the a, b, and c′ paths were moderated by distinct levels across categorical factors (male vs. female, absence vs. presence of exercise, smoking status, or specific medication consumption) and by above vs. below median values of continuous factors (age, BMI, education, income, number of chronic physical conditions). Therefore, we dichotomized continuous factors to allow for tests of group differences in model comparability. Group differences were determined by constraining the a, b, and c′ path regression weights to be equal across groups, and by testing any change in the χ2 goodness-of-fit index. Significant moderation would be denoted by statistically significant change juxtaposing Model 1 (restricted factor loadings and regression weights to equality across groups) to Model 2 (restricted all factor loadings and freed all regression weights across groups). Moreover, we investigated if the pattern of results remained similar after adjusting for these factors as covariates in the model.

Overall, there were 0.45% missing data points, which were managed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML). FIML (vs. listwise deletion) was a suitable method as our data were missing at random (Graham, 2009) [Little’s MCAR test: χ2(60) = 69.16, p = 0.19]. To determine the magnitude of effects, we computed Cohen’s d with the formula (Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, & Burke, 1996; Dunst, Hamby, & Trivette, 2004; Lakens, 2013). Specifically, d values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 denote small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Power analyses

We conducted an a priori Monte Carlo power analysis (Zhang, 2014) using Mplus Version 7.0 by specifying a conservative estimate of Cohen’s d = 0.15 for the regression weights of the a, b, and c′ paths. We observed 94.6–96.1% power to detect the a, b, and c′ paths. Further, there was 82.9% power to identify the indirect mediation path. Thus, our sample size was adequately powered to conduct the mediation analyses.

Results

Measurement model

CFA showed that the separate measurement models had excellent fit for either T1 MDD, GAD, or PD as predictors of T2 inflammation and T3 EF latent composites [χ2(25) = 42.61–48.92, p = .003–.015, CFI = .97–.98, RMSEA = .036–.041]. Statistically significant standardized factor loadings (all ps < .001) were observed for the indicators of latent T2 inflammation (three-item; βs = 0.63–0.77) and T3 EF (five-item; βs = 0.33–0.73).

Mediation models

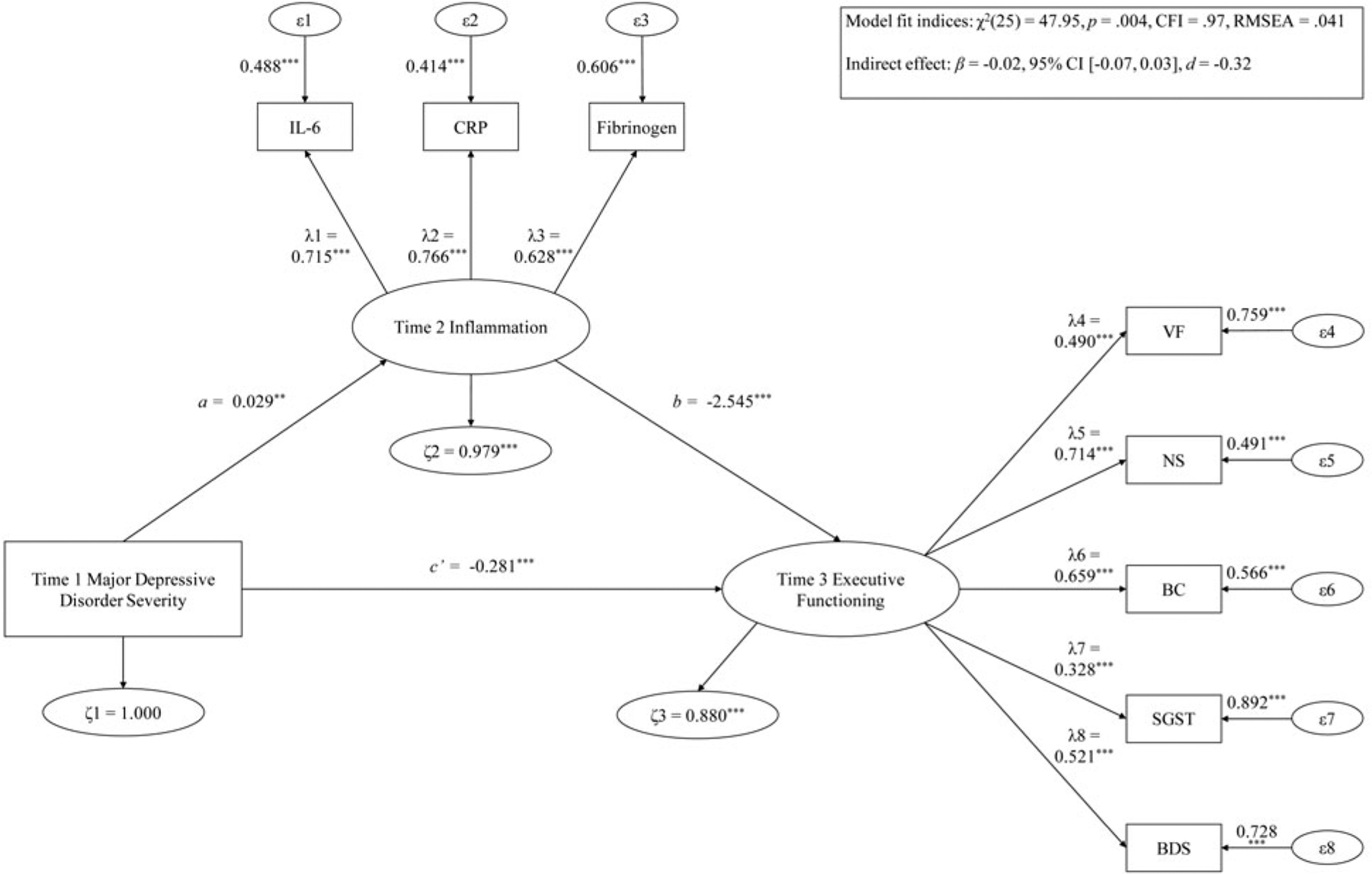

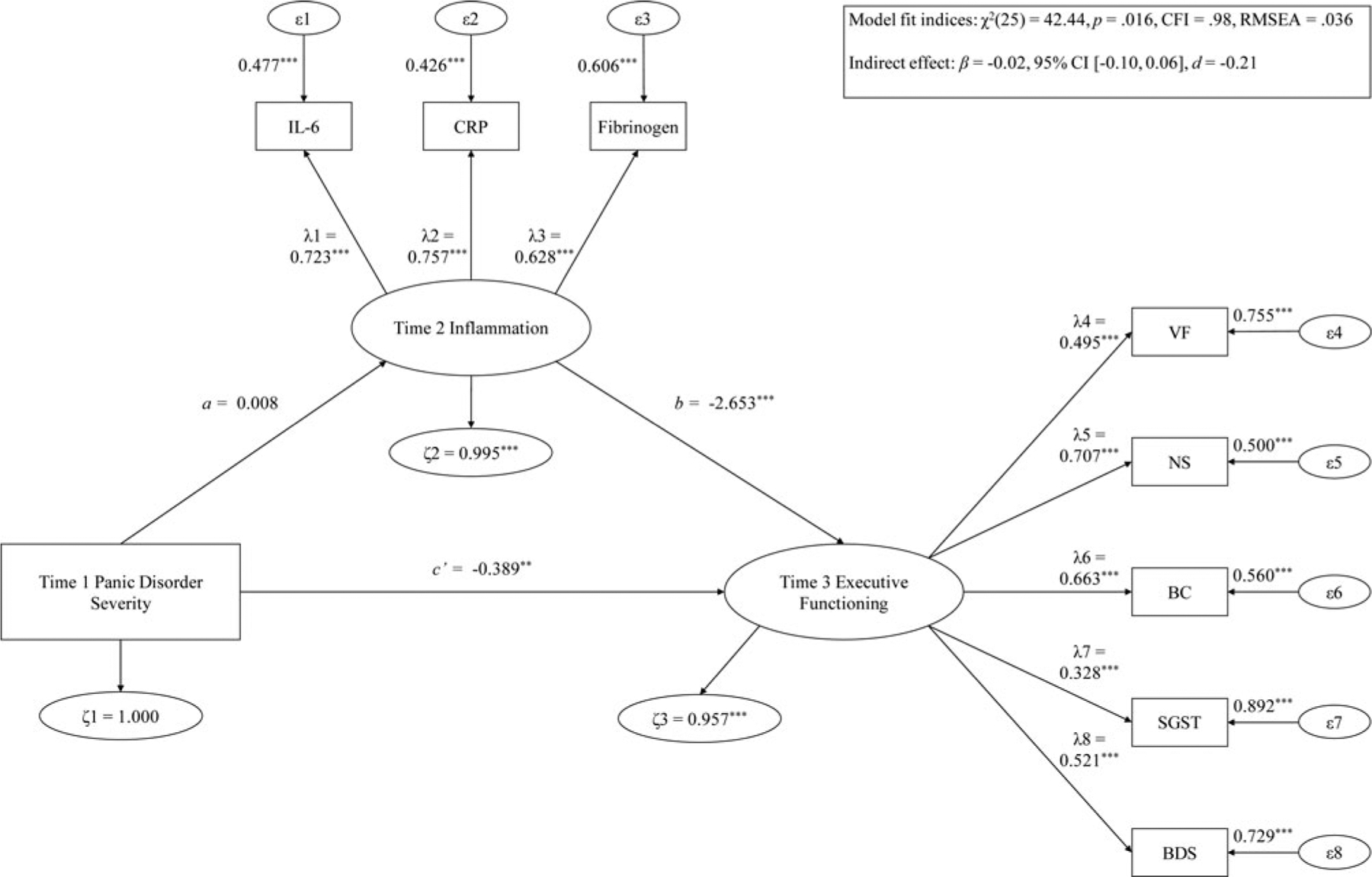

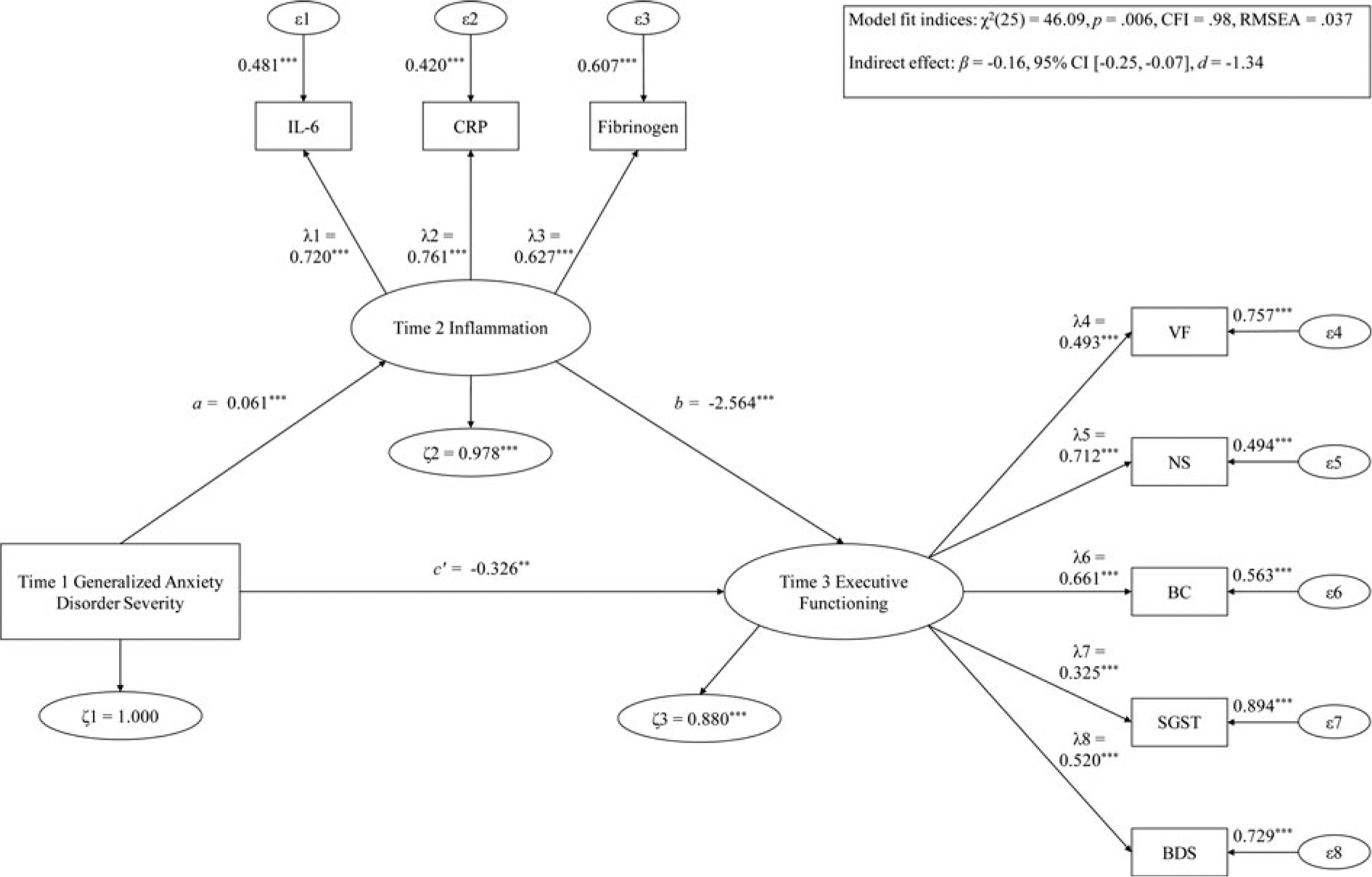

Tables 3–5 alongside Figs 1–3 present the mediation models for T1 MDD, GAD, and PD severity functioning as predictors, respectively.

Table 3.

Mediation model of T1 MDD severity predicting T3 executive function via T2 inflammation

| β (s.e.) | |

|---|---|

| Regression slopes: all samples | |

| T1 MDD severity → T3 executive function | −0.17* (0.09) |

| T1 MDD severity → T2 inflammation | 0.03** (0.01) |

| T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −2.55*** (0.53) |

| T1 MDD severity → T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −0.08** (0.03) |

CFI, confirmatory fit index; β, unstandardized regression weight estimate; MDD, major depressive disorder; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; s.e., standard error.

Model fit indices: χ2(25) = 47.95, p = .004, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04.

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05.

Table 5.

Mediation model of T1 PD severity predicting T3 executive function via T2 inflammation

| β (s.e.) | |

|---|---|

| Regression slopes: all samples | |

| T1 PD severity → T3 executive function | −0.39** (0.15) |

| T1 PD severity → T2 inflammation | 0.01 (0.02) |

| T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −2.65*** (0.53) |

| T1 PD severity → T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −0.02 (0.04) |

CFI, confirmatory fit index; β, unstandardized regression weight estimate; PD, panic disorder; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; s.e., standard error

Model fit indices: χ2(25) = 42.44, p = .016, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .036.

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesis 1 examining T1 MDD severity predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation.

Note: ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05. λ, factor loading; ϵ, item error variance; ζ, residual error variance; BC, backward counting; BDS, digit backward span; CFI, confirmatory fit index; CRP, C-reactive protein; d = Cohen’s d effect size; IL-6, interleukin-6; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SGST, stop-and-go-switch task mixed task; SX, symptom severity; T1, time 1; T2, time 2; T3, time 3; VF, verbal fluency.

Fig. 3.

Hypothesis 1 examining T1 PD severity predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation.

Note: ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05. λ, factor loading; ϵ, item error variance; ζ, residual error variance; BC, backward counting; BDS, digit backward span; CFI, confirmatory fit index; CRP, C-reactive protein; FGN, fibrinogen; IL-6, interleukin-6; NS, number series; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SGST, stop-and-go-switch task mixed task; T1, time 1; T2, time 2; T3, time 3; VF, verbal fluency.

T1 MDD predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation

The mediation model showed good fit [χ2(25) = 47.95, p = .004, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .041]. Regarding the direct effect, higher T1 MDD severity was significantly related to lower T3 EF after 20 months [β = −0.17, 95% CI (−0.34 to −0.002), d = −0.79], with a large effect size. In addition, higher T1 MDD severity substantially predicted greater T2 inflammation 2 months later [β = 0.03, 95% CI (0.01–0.05), d = 1.23], and more T2 inflammation was considerably related to lower T3 EF following 18 months [β = −2.55, 95% CI (−3.58 to −1.51), d = −1.92], with large effect sizes. The T1 MDD severity forecasting T3 EF via T2 inflammation indirect mediation path was also significantly large [β = −0.08, 95% CI (−0.13 to −0.002), d = −1.04]. T2 inflammation explained 30.36% of the T1 MDD severity–T3 EF association variance.

These variables were not significant moderators: age [Δχ2(3) = 2.89, p = .41], gender [Δχ2(3) = 4.67, p = .20], BMI [Δχ2(3) = 4.59, p = .20], number of physical health problems [Δχ2(3) = 7.35, p = .07], income [Δχ2(3) = 1.90, p = .59], education [Δχ2(3) = 1.29, p = .73], smoking status [Δχ2(3) = 4.37, p = .22], number of medications used [Δχ2(3) = 2.62, p = .45], and physical exercise status [Δχ2(3) = 5.06, p = .17]. Further, the mediation effect of T1 MDD severity forecasting reduced T3 EF through T2 inflammation remained statistically significant after adjusting age, gender, BMI, income, education, number of medications consumed, and physical exercise status (d = −0.92 to −0.77).1

T1 GAD predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation

The mediation model of T1 GAD severity predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation had good fit [χ2(25) = 46.09, p = .006, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .037]. Greater T1 GAD severity substantially forecasted lower T3 EF [β = −0.33, 95% CI (−0.54 to −0.11), d = −1.19]. Increased T1 GAD severity significantly predicted higher T2 inflammation [β = 0.06, 95% CI (0.04–0.09), d = 1.92], and T2 inflammation substantially forecasted lower T3 EF [β = −2.56, 95% CI (−3.61 to −1.52), d = −1.92]. For the entire sample, T2 inflammation significantly mediated the T1 GAD–T3 EF path [β = −0.16, 95% CI (−0.25 to −0.07), d = −1.34], and accounted for 32.22% of the variance of the T1 GAD–T3 EF relation.

Age moderated this mediation model, which showed acceptable fit [χ2(56) = 97.38, p < .001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .049]. T1 GAD predicted reduced T3 EF via T2 inflammation significantly more strongly in younger compared to older adults [Δχ2(3) = 11.19, p = .011]. Simple slopes analyses showed that for younger adults, higher T1 GAD predicted lower T3 EF [β = −0.59, 95% CI (−0.92 to −0.25), d = −0.92]. Further, among younger adults, greater T1 GAD severity substantially predicted higher T2 inflammation level [β = 0.09, 95% CI (0.05–0.12), d = 1.25], and heightened T2 inflammation considerably forecasted decreased T3 EF [β = −2.19, 95% CI (−3.47 to −0.90), d = −0.73]. Further, the mediation path was significant for younger adults [β = −0.19, 95% CI (−0.33 to −0.05), d = −0.73], such that T2 inflammation accounted for 24.48% of the T1 GAD–T3 EF relation. On the other hand, in older adults, no direct effect was observed [β = −0.09, 95% CI (−0.33 to 0.16), d = −0.18]. Further, among older adults, T1 GAD severity did not predict T2 inflammation [β = 0.02, 95% CI (−0.02 to 0.06), d = 0.30], but greater T2 inflammation level significantly forecasted lower T3 EF [β = −1.88, 95% CI (−3.41 to −0.35), d = −0.64]. For older adults, the path of T1 GAD predicting T3 EF through T2 inflammation was not significant [β = −0.04, 95% CI (−0.11 to 0.04), d = −0.27].

No other moderator effects were observed as follows: gender [Δχ2(3) = 4.30, p = .23], BMI [Δχ2(3) = 0.28, p = .96], number of physical health problems [Δχ2(3) = 1.09, p = .78], income [Δχ2(3) = 0.19, p = .98], education [Δχ2(3) = 3.27, p = .35], smoking status [Δχ2(3) = 1.45, p = .70], number of medications used [Δχ2(3) = 3.84, p = .28], and physical exercise status [Δχ2(3) = 7.80, p = .06]. In addition, the mediation path of T1 GAD severity predicting lower T3 EF through T2 inflammation stayed statistically significant after controlling for age, gender, BMI, number of physical health problems, income, education level, smoking status, number of medications consumed, and physical exercise status (d = −1.19 to −0.91).

T1 PD predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation

The mediation model displayed good fit [χ2(25) = 42.44, p = .016, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = .036]. Higher T1 PD severity significantly predicted lower T3 EF [direct effect: β = −0.39, 95% CI (−0.64 to −0.09), d = −1.07]. T1 PD severity was not significantly related to T2 inflammation [β = 0.01, 95% CI (−0.02 to 0.04), d = 0.21], but T2 inflammation level significantly forecasted reduced T3 EF [β = −2.65, 95% CI (−3.68 to −1.62), d = −2.02]. T2 inflammation did not substantially mediate the path of T1 PD predicting T3 EF [β = −0.02, 95% CI (−0.10 to 0.06), d = −0.21].

None of the following moderators emerged as significant: age [Δχ2(3) = 1.69, p = .64], gender [Δχ2(3) = 3.07, p = .38], BMI [Δχ2(3) = 0.81, p = .85], number of physical health problems [Δχ2(3) = 4.80, p = .19], income [Δχ2(3) = 1.25, p = .74], education [Δχ2(3) = 0.29, p = .96], smoking status [Δχ2(3) = 2.25, p = .52], number of medications used [Δχ2(3) = 2.02, p = .57], and physical exercise status [Δχ2(3) = 2.89, p = .41]. Moreover, the mediation path of T1 PD symptoms forecasting T3 EF via T2 inflammation remained statistically non-significant after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, number of physical health problems, income, education, smoking status, number of medications consumed, and physical exercise status (d = −0.22 to −0.19).

Discussion

Offering partial support for scar theories, these novel results indicated that heightened inflammation may be a mechanism by which greater MDD and GAD (but not PD) symptom severity results in decreased EF after 20 months. Therefore, increased MDD and GAD severity may render mid-life adults susceptible to higher CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 levels 2 months later, and elevated systemic inflammation thereby forecasted reduced EF following 18 months (explaining 25–32% of the T1 MDD–T3 EF and T1 GAD–T3 EF 20-month dimensional relations). Further, the effect of T1 GAD severity negatively predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation was stronger among younger adults relative to their older counterparts. Despite the fact that it has been often postulated that higher MDD and GAD symptoms would predict subsequent lower EF through inflammation over months and years (e.g. 3–18 years) (e.g., Zainal & Newman, 2021), to our awareness, this is the first study to empirically evaluate that notion. We provide a number of possible theoretical explanations for these findings.

The observation that pathological worry was related to lower T3 EF via increased inflammation more strongly among younger than older adults is counter-intuitive. This is in light of the reality that older adults are more at risk of persistent health issues and accumulate greater inflammation serum levels (Brüünsgaard & Pedersen, 2003). However, this counter-instinctual result may be partly explained by the fact that people tend to select mood-uplifting social situations as well as savor and recall positive memories as they age (Carstensen et al., 2011).

Further, greater initial MDD and GAD (but not PD) severity forecasted higher future CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 levels for the entire sample. Findings concur with the fact that elevated depression, GAD, and post-traumatic stress disorder were related to subsequent increased inflammation 3–31 years later among young, mid-life, and older community adults in the United States (Copeland et al., 2012a, 2012b; Niles et al., 2018), Finland (Liukkonen et al., 2006, 2011), and Switzerland (Glaus et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2015). Persons with GAD and MDD could be vulnerable to increased inflammation buildup across years due to habitual repetitive negative thinking that could prolong stress reactivity alongside ‘wear-and-tear’ of the HPA and sympathetic nervous systems (cf. perseverative cognition theory; Ottaviani et al., 2016). This notion has been supported by prior studies (e.g. Moriarity et al., 2020). Relatedly, poor lifestyle choices related to MDD and GAD (e.g. unhealthy sleep, dietary, and nutrition patterns) may dysregulate the HPA by prompting an intrinsic inflammatory reaction, reflected by a rise in CRP, fibrinogen, IL-6, and other assays (e.g. IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor) across months (Furtado & Katzman, 2015). Future cross-panel longitudinal studies can test these conjectures.

Notably, heightened inflammation consistently predicted future reduced EF. This result extends numerous single-session experiments which showed that inducing inflammation could adversely affect future performance-based EF (Bollen, Trick, Llewellyn, & Dickens, 2017). Conceivably, greater CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 levels may lead to harmful neurological changes in EF and learning-related brain regions across long durations (cf. neurological scar theories). For instance, increased CRP and IL-6 have been linked to decreased cerebral blood flow in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and medial temporal lobe 5 years later (Warren et al., 2018). Moreover, accrual of systemic inflammation could negatively change activity in the locus coeruleus norepinephrine system entwined with EF by increasing cellular oxidative stress (Balter et al., 2019). Relatedly, elevated inflammation may have over time altered the kynurenine brain pathway that creates quinolinic acid (a noxious metabolite), alongside adversely affecting dopamine, glutamate, and serotonin pathways implicated in anxiety, motivation, attentional control, and EF (Mac Giollabhui et al., 2020; Miller & Raison, 2016). Thus, incorporating MRI, inflammation, and behavioral EF measures to evaluate these hypotheses appears to be a worthwhile avenue for future prospective research.

Additionally, direct effects were found, wherein elevated MDD, GAD, and PD predicted reduced EF following 20 months. Also, increased T1 GAD forecasted lower T3 EF more strongly among younger than older adults. Findings contribute to an important knowledge gap on psychopathology–EF associations considering the dearth of prospective studies on this subject (Snyder et al., 2015, p. 328). Further, the results suggest that pathological worry and depressed mood may trigger processes that lead to long-term brain dysfunction (Bosaipo, Foss, Young, & Juruena, 2017; Zainal & Newman, in press). It would be fruitful for subsequent investigations to continue to evaluate cognitive scar hypotheses.

Some shortcomings of this study deserve mention. First, we cannot draw causal inferences from this naturalistic study. Second, we were unable to test the vulnerability theory (i.e. increased inflammation and EF deficits may prognosticate future greater MDD, GAD, and PD symptoms) as inflammation and EF were not measured at baseline. The relations among common psychiatric symptoms, inflammation, and EF have been found to be bi-directional and intricate (Majd et al., 2020; Zainal & Newman, 2018), and thus merit further attention. Relatedly, we cannot draw any definitive conclusions on whether inflammation increased from baseline and led to any of our findings because inflammation was not assessed initially or before symptom data were collected. Further, our findings may be explained by unmeasured third variables (e.g. genetics; Averill et al., 2019) that warrant consideration. Also, as the psychiatric symptom assessments in this study were aligned with the DSM-III-R, future studies should evaluate our propositions with DSM-5-derived measures. Additionally, considering the all-White sample herein and evidence that inflammation levels can differ among ethnicities (Zahodne, Kraal, Zaheed, Farris, & Sol, 2019), it would be valuable for succeeding investigations to test these hypotheses in culturally-diverse samples.

If future studies were to replicate the pattern of results herein, some clinical implications justify attention. It is tenable that effectually treating MDD, GAD, and PD in younger, mid-life, and older adults may decrease the odds of subsequent elevated inflammation and EF decrements. Empirical data that cognitive-behavioral skills and lifestyle-enhancing interventions can remarkably reduce widespread psychiatric disorder symptoms and inflammation as well as improve EF and related cognitive capacities (Zainal & Newman, 2020). Further, attempts to better understand the effectiveness of pharmacological therapies, their interaction with inflammation (Strawbridge et al., 2015), alongside the anxiolytic and anti-depressant effects of vitamin supplementation (Su et al., 2018) have been ensuing. These efforts, especially with the use of gold-standard randomized controlled trials, merit sustained consideration due to their prospect to personalize therapies for anxiety and depressive disorders.

Data

This secondary analysis used the publicly available MIDUS Refresher datasets with three time-points: 2012 [Time 1 (T1)]; 2012 [Time 2 (T2) − 2 months after T1]; and 2014 [Time 3 (T3) − 20 months after T1 and 18 months after T2] (Ryff & Lachman, 2018; Ryff et al., 2017; Weinstein et al., 2019). Since this study used a publicly available dataset, it was exempt from additional IRB approval. The authors are willing to provide R syntax and output files of the analyses conducted in this study upon request.

Fig. 2.

Hypothesis 1 examining T1 GAD severity predicting T3 EF via T2 inflammation.

Note: ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05. λ, factor loading; ϵ, item error variance; ζ, residual error variance; BC, backward counting; BDS, digit backward span; CFI, confirmatory fit index; CRP, C-reactive protein; FGN, fibrinogen; IL-6, interleukin-6; NS, number series; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SGST, stop-and-go-switch task mixed task; T1, time 1; T2, time 2; T3, time 3; VF, verbal fluency.

Table 4.

Mediation model of T1 GAD severity predicting T3 executive function via T2 inflammation

| β (s.e.) | |

|---|---|

| Regression slopes: younger adults | |

| T1 GAD severity → T3 executive function | −0.54*** (0.17) |

| T1 GAD severity → T2 inflammation | 0.09*** (0.02) |

| T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −2.19*** (0.65) |

| T1 GAD severity → T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −0.19** (0.07) |

| Regression slopes: older adults | |

| T1 GAD severity → T3 executive function | −0.09 (0.14) |

| T1 GAD severity → T2 inflammation | 0.02 (0.02) |

| T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −1.96* (0.77) |

| T1 GAD severity → T2 inflammation → T3 executive function | −0.04 (0.04) |

CFI, confirmatory fit index; β, unstandardized regression weight estimate; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; s.e., standard error.

Model fit indices: χ2(56) = 97.38, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.049.

p < 0.001;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

Financial support.

The data used in this publication were made available by the Data Archive on University of Wisconsin - Madison Institute on Aging, 1300 University Avenue, 2245 MSC, Madison, Wisconsin 53706-1532. Since 1995, the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study has been funded by the following: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network; National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166); National Institute on Aging (U19-AG051426). The original investigators and funding agency are not responsible for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. None.

Ethical standards. This study was conducted in compliance with the American Psychological Association (APA) ethical standards in the treatment of human participants and approved by the institutional review board (IRB). Informed consent was obtained from participants as per IRB requirements at Harvard University, Georgetown University, University of California at Los Angeles, and University of Wisconsin. Since this study used a publicly available dataset, it was exempt from IRB approval.

When testing covariates for models examining MDD, GAD, and PD as unique predictors, we used separate models for each covariate because adding all potential covariates or only those significantly related with T3 EF outcome to one model severely degraded model fit.

References

- Abel JL (1994, November). Alexithymia in an analogue sample of generalized anxiety disorder and non-anxious matched controls. Paper presented at the 28th annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Allott K, Fisher CA, Amminger GP, Goodall J, & Hetrick S (2016). Characterizing neurocognitive impairment in young people with major depression: State, trait, or scar? Brain and Behavior, 6, e00527. doi: 10.1002/brb3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JA, & Emory E (2006). Executive function and the frontal lobes: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology Review, 16, 17–42. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd, rev. ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Averill LA, Abdallah CG, Levey DF, Han S, Harpaz-Rotem I, Kranzler HR, … Pietrzak RH (2019). Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cognitive function in older U.S. veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Depression and Anxiety, 36, 834–845. doi: 10.1002/da.22912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balter LJT, Bosch JA, Aldred S, Drayson MT, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJCS, Higgs S, … Mazaheri A (2019). Selective effects of acute low-grade inflammation on human visual attention. Neuroimage, 202, 116098. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, & Thomas AJ (2014). Depression and dementia: Cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas, 79, 184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun MA, Weiss J, Obhi HK, Beydoun HA, Dore GA, Liang H, … Zonderman AB (2019). Cytokines are associated with longitudinal changes in cognitive performance among urban adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 80, 474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen J, Trick L, Llewellyn D, & Dickens C (2017). The effects of acute inflammation on cognitive functioning and emotional processing in humans: A systematic review of experimental studies. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 94, 47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosaipo NB, Foss MP, Young AH, & Juruena MF (2017). Neuropsychological changes in melancholic and atypical depression: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 73, 309–325. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüünsgaard H, & Pedersen BK (2003). Age-related inflammatory cytokines and disease. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America, 23, 15–39. doi: 0.1016/S0889–8561(02)00056–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, … Nesselroade JR (2011). Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging, 26, 21–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss A (1957). Gerinnungsphysiologische Schnellmethode zur Bestimmung des Fibrinogens. Acta Haematologica, 17, 237–246. doi: 10.1159/000205234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power for the social sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum and Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Angold A, & Costello EJ (2012a). Cumulative depression episodes predict later C-reactive protein levels: A prospective analysis. Biological Psychiatry, 71, 15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Angold A, & Costello EJ (2012b). Generalized anxiety and C-reactive protein levels: A prospective, longitudinal analysis. Psychological Medicine, 42, 2641–2650. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels TE, Olsen EM, & Tyrka AR (2020). Stress and psychiatric disorders: The role of mitochondria. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16, 165–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-082719-104030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darweesh SKL, Wolters FJ, Ikram MA, de Wolf F, Bos D, & Hofman A (2018). Inflammatory markers and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14, 1450–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Yang M, & Marcoulides KM (2018). Structural equation modeling with many variables: A systematic review of issues and developments. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 580. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverts DJ, Cohen S, DiLillo VG, Lewis CE, Kiefe C, Whooley M, & Matthews KA(2010). Depressive symptoms, race, and circulating C-reactive protein: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 734–741. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ec4b98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap WP, Cortina JM, Vaslow JB, & Burke MJ (1996). Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychological Methods, 1, 170–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.1.2.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Hamby DW, & Trivette CM (2004). Guidelines for calculating effect sizes for practice-based research syntheses. Centerscope, 3, 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Eyre H, & Baune BT (2012). Neuroimmunological effects of physical exercise in depression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26, 251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follmer DJ (2018). Executive function and reading comprehension: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychologist, 53, 42–60. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2017.1309295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, & Herd P (2010). Income, education, and inflammation: Differential associations in a national probability sample (The MIDUS Study). Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 290–300. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e3181cfe4c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtado M, & Katzman MA (2015). Neuroinflammatory pathways in anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and obsessive compulsive disorders. Psychiatry Research, 229, 37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher J, Bayer A, Lowe G, Fish M, Pickering J, Pedro S, … Ben-Shlomo Y (2010). Is sticky blood bad for the brain? Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 30, 599–604. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.197368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimson A, Schlosser M, Huntley JD, & Marchant NL (2018). Support for midlife anxiety diagnosis as an independent risk factor for dementia: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 8, e019399. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaus J, von Känel R, Lasserre AM, Strippoli M-PF, Vandeleur CL, Castelao E, … Merikangas KR (2018). The bidirectional relationship between anxiety disorders and circulating levels of inflammatory markers: Results from a large longitudinal population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 360–371. doi: 10.1002/da.22710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, & Naglieri JA (2014). Handbook of executive functioning. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman J, & Frishman WH (2014). Inflammation and atherosclerosis: A review of the role of interleukin-6 in the development of atherosclerosis and the potential for targeted drug therapy. Cardiology in Review, 22, 147–151. doi: 10.1097/crd.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostinar CE, Lachman M, Mroczek D, Seeman T, & Miller G (2015). Additive contributions of childhood adversity and recent stressors to inflammation at midlife: Findings from the MIDUS study. Developmental Psychology, 51(11), 1630–1644. doi: 10.1037/dev0000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NC, & Newman MG (2014). Avoidance mediates the relationship between anxiety and depression over a decade later. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, & Wittchen H-U (1998). The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview short-form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 171–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh J, Benros ME, Jørgensen MB, Vesterager L, Elfving B, & Nordentoft M (2014). The association between depressive symptoms, cognitive function, and inflammation in major depression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 35, 70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Agrigoroaei S, Tun PA, & Weaver SL (2014). Monitoring cognitive functioning: Psychometric properties of the brief test of adult cognition by telephone. Assessment, 21, 404–417. doi: 10.1177/1073191113508807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-H (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48, 936–949. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H, Li Y, & Brooks G (2016). Outlier impact and accommodation methods: Multiple comparisons of type I error rates. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 15, 452–471. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1462076520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liukkonen T, Räsänen P, Jokelainen J, Leinonen M, Järvelin MR, Meyer-Rochow VB, & Timonen M (2011). The association between anxiety and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels: Results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. European Psychiatry, 26, 363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liukkonen T, Silvennoinen-Kassinen S, Jokelainen J, Räsänen P, Leinonen M, Meyer-Rochow VB, & Timonen M (2006). The association between C-reactive protein levels and depression: Results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Biological Psychiatry, 60, 825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love GD, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, & Ryff CD (2010). Bioindicators in the MIDUS national study: Protocol, measures, sample, and comparative context. Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 1059–1080. doi: 10.1177/0898264310374355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen PJ, Pruessner J, Sousa N, Almeida OFX, Van Dam AM, Rajkowska G, … Czéh B (2014). Neuropathology of stress. Acta Neuropathologica, 127, 109–135. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1223-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, & Heim C (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10, 434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Giollabhui N, Swistun D, Murray S, Moriarity DP, Kautz MM, Ellman LM, … Alloy LB (2020). Executive dysfunction in depression in adolescence: The role of inflammation and higher body mass. Psychological Medicine, 50, 683–691. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majd M, Saunders EFH, & Engeland CG (2020). Inflammation and the dimensions of depression: A review. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 56, 100800. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Jager J, & Hemken D (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39, 87–96. doi: 10.1177/0165025414552301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Schott LL, Bromberger J, Cyranowski J, Everson-Rose SA, & Sowers MF (2007). Associations between depressive symptoms and inflammatory/hemostatic markers in women during the menopausal transition. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 124–130. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000256574.30389.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87, 873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, & Gianaros PJ (2011). Stress- and allostasis-induced brain plasticity. Annual Review of Medicine, 62, 431–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-052209-100430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, & Raison CL (2016). The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16, 22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooijaart SP, Sattar N, Trompet S, Lucke J, Stott DJ, Ford I, … de Craen AJM (2013). Circulating interleukin-6 concentration and cognitive decline in old age: The PROSPER study. Journal of Internal Medicine, 274, 77–85. doi: 10.1111/joim.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarity DP, Ng T, Titone MK, Chat IKY, Nusslock R, Miller GE, & Alloy LB (2020). Reward responsiveness and ruminative styles interact to predict inflammation and mood symptomatology. Behavior Therapy, 51, 829–842. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozink JA, Friedman EM, Coe CL, & Ryff CD (2010). Socioeconomic and psychosocial predictors of interleukin-6 in the MIDUS national sample. Health Psychology, 29, 626–635. doi: 10.1037/a0021360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles AN, Smirnova M, Lin J, & O’Donovan A (2018). Gender differences in longitudinal relationships between depression and anxiety symptoms and inflammation in the health and retirement study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 95, 149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani C, Watson DR, Meeten F, Makovac E, Garfinkel SN, & Critchley HD (2016). Neurobiological substrates of cognitive rigidity and autonomic inflexibility in generalized anxiety disorder. Biological Psychology, 119, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariante CM (2017). Why are depressed patients inflamed? A reflection on 20 years of research on depression, glucocorticoid resistance and inflammation. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 27, 554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen MA, Ryu JK, & Akassoglou K (2018). Fibrinogen in neurological diseases: Mechanisms, imaging and therapeutics. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19, 283–301. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Ali G-C, Guerchet M, Prina AM, Albanese E, & Wu Y-T (2016). Recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 8, 23. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renna ME, O’Toole MS, Spaeth PE, Lekander M, & Mennin DS (2018). The association between anxiety, traumatic stress, and obsessive–compulsive disorders and chronic inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 1081–1094. doi: 10.1002/da.22790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C, Almeida D, Ayanian J, Binkley N, Carr DS, Coe C, … Williams D (2017). Midlife in the United States (MIDUS Refresher), 2011–2014: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor].

- Ryff CD, & Lachman ME (2018). Midlife in the United States (MIDUS Refresher): Cognitive Project, 2011–2014: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor].

- Snyder HR, Miyake A, & Hankin BL (2015). Advancing understanding of executive function impairments and psychopathology: Bridging the gap between clinical and cognitive approaches. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 328. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyridaki EC, Avgoustinaki PD, & Margioris AN (2016). Obesity, inflammation and cognition. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 9, 169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, & Silove D (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 476–493. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JC, Rand KL, Muldoon MF, & Kamarck TW (2009). A prospective evaluation of the directionality of the depression–inflammation relationship. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23, 936–944. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge R, Arnone D, Danese A, Papadopoulos A, Herane Vives A, & Cleare AJ (2015). Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: A meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 25, 1532–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su K-P, Tseng P-T, Lin P-Y, Okubo R, Chen T-Y, Chen Y-W, & Matsuoka YJ (2018). Association of use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with changes in severity of anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 1, e182327. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner JA, Chen Q, Roberts AL, Winning A, Rimm EB, Gilsanz P, … Kubzansky LD (2017). Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder with inflammatory and endothelial function markers in women. Biological Psychiatry, 82, 875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, & Waller NG (2005). Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 31–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Känel R, Bellingrath S, & Kudielka BM (2009). Association between longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms and plasma fibrinogen levels in school teachers. Psychophysiology, 46, 473–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E-YN, Wagner JT, Glaus J, Vandeleur CL, Castelao E, Strippoli M-PF, … von Känel R (2015). Evidence for chronic low-grade systemic inflammation in individuals with agoraphobia from a population-based prospective study. PLoS ONE, 10, e0123757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KN, Beason-Held LL, Carlson O, Egan JM, An Y, Doshi J, … Resnick SM (2018). Elevated markers of inflammation are associated with longitudinal changes in brain function in older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 73, 770–778. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver JD, Huang MH, Albert M, Harris T, Rowe JW, & Seeman TE (2002). Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline. Neurology, 59, 371. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M, Ryff CD, & Seeman TE (2019). Midlife in the United States (MIDUS Refresher): Biomarker Project, 2012–2016: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor].

- Wen Z, & Fan X (2015). Monotonicity of effect sizes: Questioning kappa-squared as mediation effect size measure. Psychological Methods, 20, 193–203. doi: 10.1037/met0000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U (1994). Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28, 57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Kraal AZ, Zaheed A, Farris P, & Sol K (2019). Longitudinal effects of race, ethnicity, and psychosocial disadvantage on systemic inflammation. SSM – Population Health, 7, 100391. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zainal NH, & Newman MG (2018). Executive function and other cognitive deficits are distal risk factors of generalized anxiety disorder 9 years later. Psychological Medicine, 48, 2045–2053. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zainal NH, & Newman MG (2020). Mindfulness enhances cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis of 95 randomized controlled trials. Manuscript submitted for publication. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/vzxw7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zainal NH, & Newman MG (2021). Larger increase in trait negative affect is associated with greater future cognitive decline and vice versa across 23 years. Depression and Anxiety, 38, 146–160. doi: 10.1002/da.23093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zainal NH, & Newman MG (in press). Within-person increase in pathological worry predicts future depletion of unique executive functioning domains. Psychological Medicine, 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z (2014). Monte Carlo based statistical power analysis for mediation models: Methods and software. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 1184–1198. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, & Xie W (2018). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cognitive decline: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychological Medicine, 48, 1381–1389. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]