Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to examine the participants’ satisfaction and evaluation of the program’s appropriateness, outcomes and benefits from participants’ perspectives and gather suggestions from students to improve peer mentor programs.

Methods

From 2016 to 2018, 67 mentees and mentors participated in the peer mentoring program. All program participants were asked to participate in the survey, and the respondents were invited to focus group interview (FGI). Quantitative data was collected from the survey questionnaire. Qualitative data was gathered from the open-end questions in the survey and supplemented from additional semi-structured FGIs. The interview data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

Nineteen responded to the survey, and six participated in the further FGI. Qualitative data contained outcomes and mutual benefits, factors for mentoring success, negative experiences, and suggestions for improvement. Especially factors for mentoring success consisted of various methods of studying assistance, motivation, autonomy, responsibility, emotional support, and relational bonding as important topics concerning mentor-mentee experiences. The satisfaction scores about the program appropriateness, others’ attitudes, program implementation, ranged from 3.5 to 3.9 (5-point Likert scores) without significant difference between mentors and mentees. The only negative experience reported by a mentee was feeling the pressure. Specific guidelines on program implementation, pre-education for mentees, appropriate matching, and mentees’ clear purpose and spontaneity were suggested to improve the program.

Conclusion

Participants were generally satisfied with the peer mentoring program, gaining academic and non-academic achievements, including emotional support and improved relationships. Furthermore, we expect that this program can be improved with participants’ suggestions in the future.

Keywords: Peer mentoring program, Undergraduate medical students

Introduction

Students enrolled in a medical school have experienced high levels of stress as they are exposed to the heavy academic workload and highly competitive academic environment [1]. According to Jeong [2], depression among medical students positively related to levels of stress. Especially, they needed more psychological support and help during adjusting to the heavier academic workload of major courses in medical years than in premedical years, increasing challenges along with the pressure of a perfect grade. This increased academic burden makes medical students need additional support and guidelines for adjustment of school life. Thus, many medical schools utilized various mentoring programs as an advisory system [3]. Mentoring bears an important and positive influence on medical students’ academic, professional, and personal growth by improving their ability to build lasting relationships and succeed in their careers [4-7]. Mentoring establishes a positive and beneficial relationship between a mentor and a mentee [8]. Mentor was defined as the person who serves guidance and support as a helping person and advisor for fellow students [3]. So far, different types of mentoring programs have been offered to undergraduate medical students, accompanied by various researchers that have been conducted to assess the impact of each of these mentoring programs [9-11].

Among structured mentoring programs, there are programs with professors taking on the role of a mentor [5,11,12] and programs with students taking on the role of a mentor [4,8,13]. According to Heeneman and de Grave [14], mentoring in academic medicine is well known to benefit students’ self-directed learning, school adjustment, professional development, and career exploration/career choice. On the other hand, many previous studies have addressed the mentee’s perspective on the positive outcomes of a mentoring program [15] and the perspectives from mentor teachers (faculty mentors) who assisted the professional development of mentees [16]. In these studies, the success of mentoring programs was determined by participants’ commitment and interpersonal skills. For any given mentoring program’s success, the participating members must demonstrate dedication and endeavor. Although many medical schools conduct mentoring programs, ongoing, evidence-based restructuring and the flexibility to reflect feedback constantly are extremely important concerning achieving operational results [11].

According to Akinla et al. [13], near-peer or peer mentoring, wherein a mentor is one or two grade levels higher than a mentee, provides guidance and support in academic work and school life is highly effective. In particular, it has been found that there is a greater preference for peer mentoring among undergraduate medical students over any other type of mentoring program [8]. Relevant studies show that such programs generate comfortable interactions, friendship, and other substantial relationships that facilitate smooth adaptation to academic work [8]. Furthermore, during transition periods, such as those afforded moving up to a highergrade level, peer mentoring has been known to help adjust to changing environments wherein new things are learned [4].

Our medical school has been implementing a peermentoring program since 2016, in which mentors and mentees voluntarily participate. Although the benefits of peer mentoring have been reported, it is not yet widely used in medical schools in Korea. In this study, we aimed to examine the participants’ satisfaction and evaluation of the program’s appropriateness, outcomes and benefits from participants’ perspective. Also, we intended to gather suggestions from students for improving peer mentor programs through an in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences, ideas, and assessments. In order to obtain in-depth data on peer mentoring program participants’ lived experiences and perceptions about the program, it was decided to utilized qualitative interviews in addition to survey.

Methods

1. Description of the peer mentoring program

In this medical school, the peer mentoring program has been implementing since the second semester of 2016. Students shift to the main campus from a remote local campus in the second year of the premedical coursework, which means that they face adjusting to a different school environment and a new academic system. The peer-mentoring program is a 1:1 program that matches students who need help during this transition period with upper-level students or classmates as mentors. Students who need academic support during the premedical second year (PY2), the first (Y1), or the second (Y2) medical year voluntarily apply to be a mentee. Also, students two academic years above or in the same class volunteer to be a mentor. Participants had a choice to make a pair themselves unless matching was unsuccessful, in which case the school’s interference became necessary. After pairing, mentors and mentees had 2 hours of education on mentoring, rules to follow, and appropriate communication and feedback skills. Then, mentors and mentees agreed upon what areas they would provide and receive help on and how they would conduct the mentoring session. During the semester, mentors and mentees agreed to conduct the mentoring sessions at their discretion. Mentors were given the incentive of having the hours spent mentoring as hours of volunteer work.

2. Participants, data collection, and data analysis

1) Participants

Among a student body of 240, 67 voluntarily participated in a peer-mentoring program from 2016 to 2018. All mentees participated in the peer mentoring program in their second, third, fourth year of a 6-year undergraduate-entry medical school. Mentors were in the same or a higher grade than their mentees. A survey questionnaire, an explanation of the research project, and a consent form were distributed to all the program participants via email. Students willing to participate in the research signed the consent form, completed the questionnaire, and submitted them. The survey respondents were then invited to engage in focus group interview (FGI). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Asan Medical Center (approval no. 2019-0447) and conducted according to all ethical research standards. We agreed to the privacy protection provided by the participants.

2) Data collection procedure and data analysis

To assess the participants’ satisfaction and evaluation of the program’s appropriateness, outcomes and benefits from participants’ perspectives, and suggestions for improving mentoring programs, we collected quantitative and qualitative data via a survey questionnaire. Quantitative data were gathered from the general information about the program implementation: how often students participated; how mentors and mentees would meet; how many times, where, and at what times mentors and mentees would meet. Moreover, the general information pertained to this program’s appropriateness perceived by students, participants’ satisfaction with the program, the purpose for participation in the program, and mentors’ roles from mentors’ and mentees’ standpoint. Of these questions, program satisfaction and appropriateness were answered using the Likert scale of 1–5 (with 1 being “not at all” and 5 being “very high”). Descriptive statistics (frequencies, mean, standard deviation [SD] scores) were presented as frequencies and percent for categorical variables and as mean and SD for continuous variables. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare differences in continuous variables between groups because of the small sample size. For the collection of qualitative data, open-ended survey questions and FGIs were used. Open-end questions included benefits and outcomes gained by both mentors and mentees, respectively. The remarks of open-ended questions in the survey questionnaire were read thoroughly and were categorized according to similarity and frequency after content analysis.

For FGIs, participants were divided into mentor and mentee groups, and the interviews were conducted separately for 1 to 2 hours by a counseling psychologist who was an expert in qualitative research. The reason for dividing the group is that mentees might not talk honestly in front of their senior mentor. In FGIs, in-depth probing questions were as follows: (1) why and how students participated in the mentoring program, as well as how they felt or what they thought about the program; (2) the personal experiences of students; and (3) the significance of their participation. FGIs also discussed what more was needed to improve the program. The FGIs were conducted using semistructured interviewing methods referencing previous studies which used mixed methods research designs [17]. The main topics of the interview were decided upon initially. They were used as the focal point of the interview process, with more detailed questions asked as the interview proceeded to expand upon the topics. The audio-recorded FGIs were transcribed by the researchers.

It was determined that the qualitative data is saturated and sufficient when the interviewees reported that they have nothing more to say, stories were repeated, and no more new material could be obtained through the interview [18]. We decided that no further FGI would be conducted because the data obtained from FGI were sufficient with positive and negative experiences from mentees and mentors.

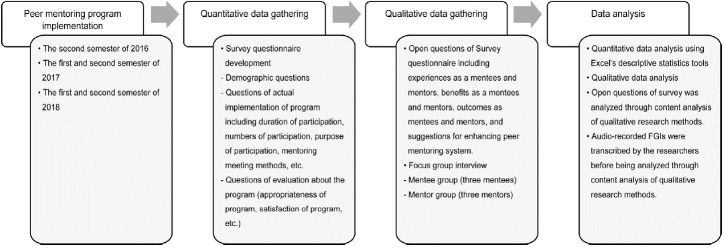

Data analysis was conducted via qualitative content analysis. The analysis process consisted of several stages: the first stage was reading and re-reading. This process is for immersing the researcher in the original data. Repeated reading of the transcripts thoroughly was performed to bracket off the researcher’s bias and prejudice. In the second stage, we gathered and summarized participants’ responses to categorize similar comments. Then finally, the concepts and main themes emerged. The resulting categories’ reliability was verified by comprehensively reading the original data and analyzing it, focusing on the designated categories. Fig. 1 shows the research process.

Fig. 1. Diagram of the Research Process.

3) Credibility of the qualitative data analysis

To maximize the accuracy and completeness of qualitative data, we recorded and transcribed the interviews thoroughly. Before transcription, the first author listened to the recorded interview right after the interview not to forget the participants’ intentions and nuances and exclude the researcher’s bias. During the interview, the interviewer asked follow-up questions to confirm the interviewer’s understanding of the participants’ intentions. At the end of every interview, participants were asked to give feedback about the interview, protocol, and research.

Furthermore, to ensure the validity of the study, auditing was conducted. For auditing, the research team asked one counseling psychologist, a qualitative research expert, and a medical education expert to review the results of qualitative data.

Results

1. Participants’ evaluation of the program implementation

Of the 67 participants in the peer-mentoring program, 19 students (28.4%; 10 mentees and nine mentors) responded to the questionnaire. Six mentees and five mentors were female. Among the 19 responders, eight students participated in the program twice or more. Among ten mentees, six students were enrolled in PY2, two students were in Y1, and one student was in Y2. Among nine mentees, four were in Y1, two were in Y2, two were in Y3, and two were in Y4.

1) The details of program implementation

Table 1 shows the details of program implementation. Approximately 80% of the responders had a mentoring meeting 4 or more times per semester. At 84% and 74%, most of the responders had face-to-face meetings and used text messages, respectively. Moreover, 64% had each meeting for 1 or 2 hours, but short meetings were held for less than 1 hour in 21% of the responders’ cases. As all the participants resided in a dormitory, the most frequent meeting place was a study room in the dormitory (42%), followed by a lecture room in the school (37%) and a cafe (32%).

Table 1.

Details of Implementing the Peer-Mentoring Program (N=19)

| Survey items | Category | No. of response (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of mentor-mentee meetings per semester | Fewer than 3 times | 4 (21) |

| 4–5 times | 7 (37) | |

| 6–8 times | 2 (11) | |

| More than 8 times | 6 (32) | |

| Meeting methods for mentoring | Offline face to face meeting | 16 (84) |

| A text message by mobile or PC | 14 (74) | |

| Average meeting hours for mentoring | Less than 1 hour | 4 (21) |

| Around 1 hour | 6 (32) | |

| Around 2 hours | 6 (32) | |

| Around 3 hours | 3 (6) | |

| Locations for mentoring | Study room of the dormitory | 8 (42) |

| Lecture room in School | 7 (37) | |

| Cafe | 6 (32) | |

| Student lounge | 4 (21) | |

| Library | 1 (5) |

2) Participants’ satisfaction and evaluation of the program’s appropriateness

Table 2 depicts satisfaction with the program. The appropriateness of the program was 3.5±0.7 for mentors and 3.7±0.9 for mentees. As for mentors’ satisfaction regarding the behavior of mentees and vice versa, mentors and mentees showed scores of 3.4±1.2 and 3.9±1.2, respectively. Satisfaction levels pertaining to the peer mentoring program were 3.6±0.5 for mentors and 3.8±1.0 for mentees. Mentees’ satisfaction scores were higher than mentors’ scores in three items, but the differences were not significant between the two groups (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Satisfaction with the Peer-Mentoring Program (N=19)

| Survey items | Mentors (N=10) | Mentees (N=9) | p-valuea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Was the peer mentoring program appropriate? | 3.5±0.7 | 3.7±0.9 | 0.68 |

| Was the mentor’s or mentee’s attitude satisfactory? | 3.4±1.2 | 3.9±1.2 | 0.33 |

| Were the content and implementation of peer mentoring satisfactory? | 3.6±0.5 | 3.8±1.0 | 0.60 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

By Mann-Whitney U-test statistics.

3) The purpose of students’ voluntary participation and the role of mentors

Table 3 demonstrates the purpose of participation in the program. Mentors reported that they wanted to help their underclassmen based on what they had learned that far. Moreover, they wanted to grow as individuals and develop a strong sense of responsibility. As for mentees, the majority reported that they participated in the program to enhance their learning skills and improve their grades. However, a small proportion of mentees joined the program because they needed help in various aspects of school life.

Table 3.

Purpose for Participation in the Peer-Mentoring Program (N=19)

| Purpose for participation | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mentors | Patronize my juniors based on what I’ve learned | 4 (40) |

| Give a helping hand to someone’s study | 4 (40) | |

| Develop my sense of responsibility | 2 (20) | |

| Involve helping someone who nearby | 1 (10) | |

| Mentees | Strengthen academic achievement | 2 (29) |

| Ask advice from an academic assistant | 2 (29) | |

| Improve study methods and strategies | 1 (14) | |

| Receive support for academic and school life | 1 (14) |

Two participants did not respond for open question/multiple responses allowed.

Table 4 shows the responses to the question about the role of mentors from mentors’ and mentees’ standpoints. As the mentors’ role, a teaching assistant and a facilitator for learning were the most common answers in both groups in approximately 70% and 60%, respectively. Moreover, mentors perceived the mentors’ role as assistants for school life management and emotional support in 30% and 20%, respectively. On the other hand, mentees chose a private tutor and emotional support for the role of mentors in 22% for each.

Table 4.

Role of Mentors from Mentors’ and Mentees’ Standpoint

| Category | No. of response (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mentors (N=10) | Teaching assistant for test-taking strategies and guidelines | 7 | (70) |

| Facilitator for learning | 6 | (60) | |

| Assistant for school life management | 3 | (30) | |

| Emotional support | 2 | (20) | |

| Private tutor | 1 | (10) | |

| Provider for study resources | 1 | (10) | |

| Mentees (N=9) | Teaching assistant for test-taking strategies and guidelines | 6 | (67) |

| Facilitator for learning | 5 | (56) | |

| Emotional support | 2 | (22) | |

| Private tutor | 2 | (22) | |

| Assistant for school life management | 1 | (11) | |

| Provider for study resources | 0 | ||

Three multiple responses allowed.

2. Programs’ outcomes and benefits from participants’ perspective

Qualitative data were presented in Table 5. Data on outcomes and benefits, negative experiences, and suggestions for improving the mentoring program were collected from the responses to open-ended questions in the survey questionnaire. More detailed data were obtained through the FGI, such as factors of mentoring success, what they did during the mentoring, and meanings of the program for themselves. After analyzing the qualitative data gathered from FGIs, both mentors’ and mentees’ experiences with the peer mentoring program were categorized as major themes that could be considered universal and fundamental. The major themes from the analysis of FGIs were: (1) outcomes and mutual benefits, (2) factors of success, which consisted of various methods of studying assistance, motivation/autonomy/responsibility, and emotional support/relational bonding, and (3) negative experiences. The analysis of qualitative data was presented by mentors’ and mentees’ perspectives separately.

Table 5.

The Results of Qualitative Analysis

| Mentees | Mentors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Mentees’ outcome which mentors saw | ||

| - Improve academic success, motivation, & study strategies, and so forth | |||

| · Better performance on an examination | |||

| · Develop learning motivation | |||

| · Studying more effective | |||

| · Take up one’s study before the exam period | |||

| · Practice diverse learning strategies | |||

| - Improve lifestyle | |||

| · Life habit improvement | |||

| · Improve academic conscientiousness | |||

| - Reflective ability & emotional support | |||

| · Facilitate reflective thinking | |||

| · Reduce anxiety and getting emotional support | |||

| Mentees’ outcome which mentees felt | |||

| - Improve academic success, self-regulated learning habits | |||

| · Better performance on an examination | |||

| · Develop self-regulated learning habits | |||

| · Studying more effective, find out effective learning methods | |||

| - Improve reflective ability | |||

| · Facilitate reflective thinking | |||

| · More confidence | |||

| - Improve lifestyle | |||

| · Life habit improvement (attendance, academic conscientiousness) | |||

| Mutual benefits | - Improve academic success, & study strategies | - Improvement of interpersonal relationship | |

| · Better performance on an examination | · Benefits for social relationship | ||

| · Improve effective learning methods | · Building rapport with juniors | ||

| · Learn study strategies of seniors | · Maintaining an emotional relationship with a mentee | ||

| · Learn preparation methods of exam | · Getting close with mentees | ||

| · Practice diverse learning strategies | · Getting more understand mentee’s mentality | ||

| · Obtain study resources and advise | · Be concerned with mentee’s school life | ||

| · Taking care of mentee | |||

| · Communicating thinking and feeling with a mentee | |||

| - Improvement of interpersonal relationship | - Improvement of responsibility | ||

| · Getting close with seniors | · Make sure what I’ve learned | ||

| · Obtaining emotional support | · Improve my responsibility | ||

| · Communicating with seniors | · Pushing myself up to do self-development | ||

| · Improvement interpersonal relationship with seniors | · Reflect on my study habit | ||

| · Build up myself to advise mentee’s study habit | |||

| - Support school life and emotion | - Feeling joy by giving a helping hand to others | ||

| · Obtaining help for school life | · Feeling joy by giving a helping hand to a mentee | ||

| · Building personal life habits | · Great receiving credit as community service | ||

| · Getting emotional support | |||

| · Less anxiety | |||

| Factors of success | - Various methods of studying assistance | - Various methods of studying assistance | |

| · A review session 2 weeks before each exam to emphasize important points | · Sharing study habits, and advising how to manage the study material in a structured way | ||

| · Teaching effective test-taking strategies | · Advising on how to stay focused during class, and how to manage time | ||

| · Advising set up an efficient study plan | |||

| - Motivation, autonomy, & responsibility | - Motivation, autonomy, & responsibility | ||

| · High level of motivation | · High levels of responsibility | ||

| · Clear purpose of study (autonomy) | · Getting mentees’ motivated | ||

| · High level of responsibility | · Getting mentees’ study purpose clearly | ||

| - Emotional support and relational bonding | - Emotional support and relational bonding | ||

| · Obtaining emotional support | · Taking care and getting close with mentees | ||

| · Building relational bonding | · Building good relationship with mentees | ||

| Negative experiences | - Feeling pressure | - Not doing homework or study tasks due to lack of mentee’s spontaneity | |

| · Mentor made me feel pressure | · Not improving mentees’ learning habits or attitudes nevertheless continuous asking improvement | ||

| · Not doing homework | |||

| · Not contacting or requesting in advance | |||

| Suggestions for improvement | · Specific guidelines on how to do | · Specific guidelines on how to do | |

| · Training and education for mentees | · Training and education for mentees | ||

| · Appropriate matching between mentor and mentee | · Appropriate matching between mentor and mentee | ||

| · Mentees and mentors both need to know the characteristics and tendencies with each other | |||

| · Mentee's clear purpose | |||

| · Mentee’s spontaneity | |||

1) Outcomes and mutual benefits

We found that mentees' outcomes from the mentors’ and mentees’ perspectives. First, mentors reported their mentees’ outcomes, including improved grades, an increased willingness and motivation to study, improved lifestyle patterns, emotional support. Also, mentees reported their outcomes, including better performance on an examination, self-regulated learning habits, improved reflective ability, and improved school attendance, academic conscientiousness. Second, from mentees’ perspectives, most respondents reported that academic success and improvement study strategies are the first and best benefit they have obtained from the mentoring program. Moreover, improving interpersonal relationships and obtaining support in school life and emotions are followed. As for what mentors felt they gained benefits through the mentoring program, responses included that they had a better understanding of the previous learning content, felt a stronger sense of responsibility, and built an emotional and personal relationship with mentees whereby they could be of help to each other.

Meanwhile, as with the themes derived from openended questions of the survey questionnaire, the theme of mutual benefits of both mentees and mentors is the most important subject from data of the FGI. When most people think of peer mentoring programs, they envision a one-way relationship where mentees receive most of the benefits while mentors work hard to help out as much as possible. However, many mentors reported that participation in the mentoring program helped them as well.

a. Mentors perspectives

“One positive outcome while mentoring was the fact that my grades also improved. My mentee did not know that I did not fully understand either, so this prompted me to study the material once more. When my mentee asked me questions, I found that I better understood the material as I tried to explain it. Honestly, mentoring did not feel like a one-way teaching session or volunteer work where I felt like I was wasting my time but, rather, like a session for studying together. In many instances, when I set up a study plan and scold my mentee, I was scolding myself in reality. After all, there are times when I, too, lose focus and feel like slacking off. Having a mentee whom I constantly reminded not to be late made me ensure that I was not late for appointments. It would not make sense for me to tell my mentee to study while I did not practice what I preached. Participating in the mentoring program helped me spend my second year of medical coursework with a very stable, regular lifestyle pattern. Overall, I became better at managing my everyday routine, even though the steps I was taking were initially done with the goal of helping my mentee in mind.”

“I felt like there was not much that I had done as an actual mentor. Even though I am a mentor, it is not as if my grades are exceptionally high. It is just that I am an upperclassman, so I have already experienced everything that my mentee has been going through. This meant that I could tell my mentee what classes are held during each block and so on. I am not the type of mentor who studies hard and can answer any question thrown at me on the spot. However, participating in this program has also been helpful to me. I am also the type of person who tends to do what I enjoy and am interested in and avoid things I do not enjoy, and there are also times when I do a lot of nothing. On the other hand, my mentee is the type to study diligently all the time, which I believe has had a positive impact on my lifestyle.”

b. Mentees perspectives

“We tend to support and motivate each other in everyday life. For example, if my mentor says she wants to work out, I find myself trying my best to work out as well. If I see my mentor working hard on something, I am also motivated to work hard in all aspects of my life. I feel like there exists a mutual, positive stimulation effect between us. I used to be the one who did not take time off, even on the weekends, but after coming to college and not having my mother around to make me do this or that, I found myself not knowing what to do with my extra time. However, by observing my mentor, I realized that I do not always have to be doing something; rather, I have reached a balance where I work hard when necessary, take a break when I need to, and catch up on work that I might have missed during the week.”

2) Factors of success

a. Various methods of studying assistance

Both mentees and mentors reported that another important factor to success in the mentoring program is the various methods of studying assistance. Mentors provided various methods of studying assistance to help mentees get accustomed to studying methods and the amount to study for medical students. Even students who are diligent and accomplished enough to be accepted to a medical school are often faced with difficulties in handling the immense workloads and are unsure how to approach and study the vast number of materials. As a result, there are many students who are unable to develop proficient self-study habits. Both mentors and mentees believe that close guidance for mentees regarding studying and lifestyle habits and test-taking strategies is essential.

i) Mentors’ perspectives

“My mentee wanted to study hard but was not sure of how to go about it. So, at first, I shared study habits with the mentee and advised him on how to manage the study material in a structured way. Also, I advised him on how to stay focused during class, how to manage time, what to study and how many weeks in advance to prepare for an exam. Two weeks before an exam, we met, and I helped him set up an efficient study plan, asking my mentee to read over the class notes and organize them as best as possible. Then, the next time we met, I looked over his notes.”

“Despite it being a week before an exam, my mentee did not feel a sense of urgency when it came to studying, so I constantly reminded him to start studying right then. I went over previous exam papers with my mentee and outlined which questions each professor would include in the exam, telling him to study for the upcoming exams with the notes. I also shared notes that my mentee had missed taking because he used to doze off in class. When my mentee started studying, there was a lot of material that he did not understand, so we would communicate through a social network, and I helped him out whenever I could. I used all the means I could think of to make sure my mentee did not fail. To be honest, I am more of the type to spoon-feed my mentee with whatever he needs, so I never really helped him actively develop a set of studying habits and waited for him to figure things out on his own. Till the very last moment before a test, I would advise my mentee to memorize this or quickly go over that because they may appear in the exam.”

“My biggest contribution was helping with lifestyle management. I would check to make sure my mentee woke up on time every morning and would go to his room to wake him up if necessary. I would also call up my mentee if he was late to ask where he was and scold him for missing or snoozing during a lecture. I did my best to help my mentee improve his lifestyle patterns.”

“I helped organize my mentee’s study plans. In particular, my mentee enjoyed meeting up with friends, going out to drink, and just using his free time for fun. Even right before exams, he had already set up plans to meet up with friends. So, I would remind him not to make plans night out and tell him when to start studying instead while also drawing up a study plan for him. During the second year of medical coursework, I gave my mentee feedback after each exam based on his grade. I would always check my mentee’s class rank after each exam, look up the ranks of the people he hung around with, and then use this information to motivate him by telling him something along the lines of how his friends beat him and that he needed to try harder to beat them next time. I also held review sessions at the end of each block and calculated my mentee’s final grade often to help motivate him, emphasizing any possibility of failing to make him feel pressured and realize how much harder he needs to work on the next block.”

ii) Mentees perspectives

“My mentor offered to hold a review session 2 weeks before each exam, so we held our sessions then. My mentor would then look at my class print-outs and notes and ask me to explain the material as I understood it. He would then emphasize important points or explain certain concepts again.”

“Meeting with my mentor was helpful because she taught me test-taking strategies. Before I participated in the program, I was very poor at preparing for the exam. However, the experienced mentor helped me with an effective strategy for each subject, and I felt less stressed and better l prepared through the mentoring process.”

b. Motivation, autonomy, and responsibility

Mentors and mentees stated that a shared sense of autonomy, levels of motivation, and responsibility that mentors and mentees felt for one another greatly impacted the positive results of the peer-mentoring program. However, some mentees also mentioned that their mentors felt burdened by the excessive responsibility they had to improve their mentees’ grades. On the other hand, some mentees stated that when mentees worked hard with motivation, they experienced a synergistic effect correlating with their mentor’s responsibility toward them.

i) Mentors perspectives

“My first two mentees were not voluntary participants in the peer mentoring program. In other words, they were not self-motivated to seek out mentors but, rather, were assigned to a mentor as part of the peer mentoring program. These mentees had no will or desire to study and did not want to take part in the peer mentoring program. As a result, whenever I tried to help them with something, they simply evaded help by saying they would do it on their own. Before the exam, I asked them to read over their notes and summarize the study material to go over them together the following week, but they did not heed my advice. Till right before the exam, they had not read over their class notes even once. When I asked them why they had not studied, they told me that they had no friends and were always alone in their rooms all day, so that they did not have an understanding of how much other students were studying and, thus, how much of preparations were expected of them. Eventually, the mentee ended up failing that semester. I felt like it was my fault and felt really guilty, frustrated, and upset, to the point that I considered quitting mentoring. From this experience, I learned that no matter how hard a mentor tries, if a mentee is not motivated and not willing to work hard on his or her own, all efforts are futile and unrewarding in the end.”

“Sometimes, I felt that I simply used to do everything for my mentee. I pretty much spoon-fed him because I was not patient enough to wait for him to study hard on his own. Rather, I would just tell him what was likely to appear on the exam, so he could memorize all of it through my direction. Whenever my mentee would go out drinking and miss classes, I felt guilty and responsible. After all, since I was his mentor, I felt it was my job to motivate my mentee to study, but then I would doubt myself and wonder whether a mentor had to go that far. Sometimes I would think to myself, who am I to scold this student for not studying?”

ii) Mentees perspectives

“It is essential for mentees and mentors to build a sense of responsibility toward each other. Mentees should follow suggestions made by their mentors, and mentors should do their best to provide practical help so that mentees feel motivated to keep trying hard.”

“Mentoring is most effective when mentees are motivated to study, and mentors provide them with appropriate study strategies. Mentees who are not motivated need to meet mentors who can push them hard enough so that they can become motivated.”

c. Emotional support and relational bonding

Both mentors and mentees reported that one of the most helpful aspects of the peer mentoring program was that they felt their mentor-mentee relationship grow stronger and developed a sense of bonding while also providing each other emotional support. One of the most significant results of this program was that mentors and mentees built a profound personal relationship and offered support for each other, rather than simply providing academic guidance or sharing lifestyle tips.

i) Mentors perspectives

“I became very close to my mentee and grew quite fond of him. My mentee was always the type who would contact me regarding things that were not always related to academics, so we discussed many diverse topics. Often, my mentee had a lot of personal concerns and was going through rough patches, sometimes even missing classes and struggling to find mental clarity and get back on track. During this time, I did my best to listen to him vent and support him in whichever way possible, something that helped us build a much stronger and deeper bond.”

ii) Mentees perspectives

“One of the reasons I have trouble studying is because I cannot always control my emotions. This mentoring program helped me concentrate on my studies because, thanks to my mentor, I had someone whom I could talk to and who was willing to listen to me. It helped me to have an outlet to express my emotions and let it all out. In particular, I am almost neurotically anxious on the day before an exam. My heart would beat fast, or my stomach would hurt just before an exam. During these times, my mentor would reassure me that I do the best I could. Regardless of how much the other students studied and prepared, I felt a sense of comfort in my mentor’s soothing words that I had done my bit, something that helped me calm my nerves and fall asleep at night.”

“Whenever I would go with my mentor to study at a cafe, we would not only study but also talk about various other things. The fact that our personalities are slightly different was something that turned out to be helpful. When I could not understand others or empathize with other students’ actions, my mentor gave me a different perspective to see the other side. Sharing conversations with my mentor was very helpful. Our study methods are different, so it was a new experience witnessing how someone studies differently and an opportunity to learn, changing the way I think about things and broadening my horizons.”

3) Negative experiences

About the open-ended question, which is the worst experience during the program, only one mentee of the 19 survey respondents answered. “Feeling pressure” is a negative experience from the mentee’s perspective. Meanwhile, as for mentors’ negative experiences, responses included “not improving mentees’ learning habits or attitudes nevertheless continuous asking improvement”, “not doing homework”, and “not contacting or requesting in advance”.

“My first two mentees were not voluntary participants in the peer mentoring program. In other words, they were not self-motivated to seek out mentors but, rather, were assigned to a mentor as part of the peer mentoring program. These mentees had no will or desire to study and did not want to participate in the peer mentoring program. I felt like it was my fault and felt guilty, frustrated, and upset, to the point that I considered quitting mentoring.”

3. Suggestions for improving peer mentoring programs

The themes derived from the open-ended question of the survey questionnaire on the suggestions for improving peer mentoring programs are as follows. Both mentees and mentors suggested that “specific guidelines on how to do”, “training and education for mentees”, “appropriate matching between mentor and mentee”, and “appropriate matching between mentor and mentee” are important. As for mentors, first, mentees and mentors need to know the characteristics and tendencies of each other. Second, the mentee has to have a clear purpose when they participate in the peer mentoring program. Third, the mentee’s voluntary participation is essential.

Discussion

This study sought to examine the actual implementation of the peer mentoring program, the satisfaction, perceived outcomes, benefits, mentors’ and mentees’ experience, and suggestions for future mentoring programs derived by medical students who participated in a voluntary peer mentoring program. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first full-fledged study that utilized both qualitative and quantitative data from mentors’ and mentees’ perspectives to evaluate peer mentoring programs of medical schools in South Korea, although a few small case reports have been drawn up [19,20].

When reviewing the administered survey results, participants evaluated that they were generally satisfied with the peer mentoring program. There was no significant difference in the ratings accorded by the mentor and mentee groups. This study was in agreement with the previous study conducted by Altonji et al. [21], which demonstrated an overall satisfaction level of 7.47 out of the 10-point Likert scale, as they were in terms of academic, emotional, and social benefits derived by participants. Furthermore, the results of this study showed similarities with the study conducted by Lian et al. [8], wherein all mentors and mentees who participated in a peer-mentoring program were satisfied.

Next, based on the survey results regarding the detailed implementational content of the peer mentoring program, 37% of mentors and mentees responded that they met 4 to 5 times during a given semester, and 32% responded that they met 10 or more times. These results were similar to those of the study conducted by Lian et al. [8], where 38.5% and 34.6% of mentoring meetings were held at least once a month and once a quarter, respectively. The results of our study showed that 31.6% of mentoring meetings were held for 1 hour, while 31.6% of meetings were held for 2 hours, these being two of the most common responses. These results are, again, similar to those from Lian et al. [8], which showed that 57% of mentoring meetings were held for less than 2 hours.

In this study, when it came to the reasons and objectives behind mentors and mentees choosing to participate in the peer mentoring program, mentors said they participated because they either wanted to help motivate underclassmen and fellow classmates or promote personal growth by strengthening their senses of responsibility. Meanwhile, most mentees said they participated in the program to improve their study methods and grades while also receiving help adjusting to school life. These results are similar to those from Lian et al. [8], This showed that 77.5% of mentormentee meetings were conducted to give and receive academic help.

Both mentees and mentors emphasized the positive outcomes and mutual benefits of the peer mentoring program. Mentees’ positive outcomes included academic help, improved grades, a sense of willingness and motivation to study, their lifestyle patterns improved, a stronger sense of dedication, emotional stress relief, acquiring various study methods, introspection skills, and more diverse conversations with others. Mentors reported a stronger sense of responsibility and an emotional, personal relationship with mentees. These results were similar to those of Abdolalizadeh et al. [4], wherein each mentee was assigned to two separate upper-class mentors, of whom one was in premedical coursework, and one was in medical coursework, as part of a “dual peer mentoring program”. In other words, mentors and mentees reported that a peer mentoring program helped provide academic help and offer psychosocial support, and built positive relationships. Furthermore, in Lian et al. [8], 77% of mentees reported benefits from an academic perspective through peer mentoring programs, bearing similarities with the results of this study.

In this study, the results of the in-depth focus interviews helped identify “factors for peer mentoring program success” were “various methods of studying assistance”, “motivation, autonomy, and responsibility”, and “emotional support and relational bonding” as important themes concerning mentor-mentee perspectives. These results align with those of Akinla et al. [13], wherein the results of qualitative research on existing peer mentoring programs were gathered and systematically reviewed. According to Akinla et al. [13], peer mentoring programs were shown to help underclassmen adjust to medical school and grow personally and professionally while also helping new students in the transitioning phase as they acclimate to school life. Furthermore, mentoring programs were shown to reduce stress among underclassmen in transitioning phases and provide a support system that can help them face difficulties and adjust to new circumstances.

Participation in the peer mentoring program at a medical school was not a requirement for all students but, rather, a supportive program for mentees who felt like they needed it and mentors who voluntarily choose to participate in it. It was a meaningful program that proved helpful in situations where schools did not force more frequent, intimate interactions and personal relations among students. These results are similar to the findings of Lutz et al. [22]. This demonstrates that when participation in upper-underclassmen or professorstudent mentoring programs is required of students by schools, there is increased resistance, and often difficulties are faced in developing serious relationships. Instead, empathetic and flexible approaches are more beneficial when promoting the development of students’ professional identities. In particular, a dependable and stable relationship and environment, respectively, between mentor and mentee are of paramount importance in the success of peer mentoring programs. Furthermore, results demonstrated that, as opposed to advising professors, interactions with upperclassmen or peers were more effective in boosting motivation in students. In a previous study by Tan et al. [11], an efficient mentor-mentee relationship and a consistently supportive experience in a given mentoring program were shown to influence the success or failure of a mentoring program. This result is consistent with our study.

There are some limitations of this study. This study was conducted with a sample group of students from one medical school in South Korea, which means that it may be difficult to apply the results generally when considering other universities’ unique characteristics and environments. However, the results of this study can be used as prototypical data set for the development and operations of peer mentoring programs at other medical universities in alignment with the needs of students and professors and the respective environment and circumstances of the university in question. Second, it is important to note that the participation rate of students in the peer mentoring program’s survey, especially in the satisfaction and implementational methods survey, was low. During the study period, many program participants were already training after graduation, so the response rate was insufficient. There is a need to gather more feedback on the participants’ experiences with the program and overall program implementations by conducting regular assessments when the program ends each semester.

Third, we conducted each FGI separately for mentors and mentees at one time in this study. In the first process, we gathered qualitative data from open-ended questions of the survey questionnaire. And then, the detailed answers were supplemented through FGIs. As described above, the reason for the separation of groups was because of the Korean culture that could not be honest in front of the seniors. We decided not to conduct further FGIs because we have defined that data obtained from FGI are saturated when there are no more new stories. We considered the data acquired by open-end questions in the questionnaire and an FGI sufficient. However, it will be more helpful to conduct more than two or three FGI in gathering more diverse opinions and in-depth experiences for further research.

In conclusion, in this study, mentors and mentees were generally satisfied with the peer mentoring program. Although the satisfaction scores of mentees were higher than those of mentors, there was no significant difference. The participants gained through the program academic achievement and also non-academic achievements, including emotional support and improved relationships. In order to improve the peer mentoring program, it would be helpful to (1) encourage the voluntary participation of mentees and mentors, (2) strengthen pre-education of program participants, and (3) provide supplementary materials such as the program’s implementing guidelines.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

MC contributed to basic research ideas and design, data collection and analysis, thesis composition; YSL contributed to basic research ideas and design, data collection, final edits.

References

- 1.Ahn D, Kim O. Perfectionism, achievement goals, and academic efficacy in medical students. Korean J Med Educ. 2006;18(2):141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeong YR. Research trend on depression of Korean medical students: focused on dissertations and publications between 2000 and 2017 [master’s thesis] Busan, Korea: Kyungsung University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lapp H, Makowka P, Recker F. Peer-mentoring program during the preclinical years of medical school at Bonn University: a project description. GMS J Med Educ. 2018;35(1):Doc7. doi: 10.3205/zma001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdolalizadeh P, Pourhassan S, Gandomkar R, Heidari F, Sohrabpour AA. Dual peer mentoring program for undergraduate medical students: exploring the perceptions of mentors and mentees. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2017;31:2. doi: 10.18869/mjiri.31.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho Y, Kwon OY, Park SY, Yoon TY. A study of satisfaction of medical students on their mentoring programs at one medical school in Korea. Korean J Med Educ. 2017;29(4):253–262. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2017.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalén S, Ponzer S, Seeberger A, Kiessling A, Silén C. Continuous mentoring of medical students provides space for reflection and awareness of their own development. Int J Med Educ. 2012;3:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lian CW, Hazmi H, Bing JH, Ying CJ, Nazif NN, Kamil SN. Peer mentoring among undergraduate medical students: experience from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. Educ Med J. 2015;7(1):e45–e54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frei E, Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Mentoring programs for medical students: a review of the PubMed literature 2000-2008. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von der Borch P, Dimitriadis K, Störmann S, et al. A novel large-scale mentoring program for medical students based on a quantitative and qualitative needs analysis. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2011;28(2):Doc26. doi: 10.3205/zma000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan YS, Teo SW, Pei Y, et al. A framework for mentoring of medical students: thematic analysis of mentoring programmes between 2000 and 2015. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(4):671–697. doi: 10.1007/s10459-018-9821-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hur Y, Cho AR, Kim S. Exploring the possibility of one-on-one mentoring as an alternative to the current student support system in medical education. Korean J Med Educ. 2018;30(2):119–130. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2018.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akinla O, Hagan P, Atiomo W. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring programs for first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1195-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heeneman S, de Grave W. Tensions in mentoring medical students toward self-directed and reflective learning in a longitudinal portfolio-based mentoring system: an activity theory analysis. Med Teach. 2017;39(4):368–376. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1286308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauer KE, Teherani A, Dechet A, Aagaard EM. Medical students’ perceptions of mentoring: a focus-group analysis. Med Teach. 2005;27(8):732–734. doi: 10.1080/01421590500271316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:72–78. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J. College students’ awareness of extra-curricular and extra-curricular graduate certificate qualitative and quantitative approach. J Learn Cent Curric Instr. 2018;18(13):245–266. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WK, Park KH. A narrative inquiry of medical students’ experiences of expulsion and military service. Korean Med Educ Rev. 2019;21(2):92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Lee SH, Kim EJ, Kim H, Hwang J. A case study on small group teaching programs in medical school: SNU mentoring, peer tutoring, coaching, and research mentoring programs. Korean Med Educ Rev. 2012;14(2):78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MS, Kim JH, Kim DY, Kim JH, Park HJ. Awareness of students for implementation of a peer mentoring program in a medical school. Keimyung Med J. 2016;35(2):113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altonji SJ, Baños JH, Harada CN. Perceived benefits of a peer mentoring program for first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(4):445–452. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1574579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutz G, Pankoke N, Goldblatt H, Hofmann M, Zupanic M. Enhancing medical students’ reflectivity in mentoring groups for professional development: a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0951-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]