Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether sleep disparities vary by birthplace among non-Hispanic White (NHW) and Hispanic/Latino adults in the USA and to investigate language preference as an effect modifier.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

USA.

Participants

254 699 men and women.

Methods

We used pooled 2004–2017 National Health Interview Survey data. Adjusting for sociodemographic and behavioural/clinical characteristics, survey-weighted Poisson regressions with robust variance estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs of self-reported sleep characteristics (eg, sleep duration, trouble staying asleep) among (1) foreign-born NHW adults and Hispanic/Latino heritage groups versus US-born NHW adults and (2) Hispanic/Latino heritage groups versus foreign-born NHW adults. We further stratified by language preference in comparisons of Hispanic/Latino heritage groups with the US-born NHW group.

Results

Among 254 699 participants with a mean age±SE 47±0.9 years, 81% self-identified their race/ethnicity as NHW, 12% Mexican, 2% Puerto Rican, 1% Cuban, 1% Dominican and 3% Central/South American. Compared with US-born NHW adults, foreign-born NHW adults were more likely to report poor sleep quality (eg, PRtrouble staying asleep=1.27 (95% CI: 1.17 to 1.37)), and US-born Mexican adults were no more likely to report non-recommended sleep duration while foreign-born Mexican adults were less likely (eg, PR≤5-hours=0.52 (0.47 to 0.57)). Overall, Mexican adults had lower prevalence of poor sleep quality versus US-born NHW adults, and PRs were lowest for foreign-born Mexican adults. US-born Mexican adults were more likely than foreign-born NHW adults to report shorter sleep duration. Regardless of birthplace, Puerto Rican adults were more likely to report shorter sleep duration versus NHW adults. Generally, sleep duration and quality were better among Cuban and Dominican adults versus US-born NHW adults but were similar versus foreign-born NHW adults. Despite imprecision in certain estimates, Spanish language preference was generally associated with increasingly better sleep among Hispanic/Latino heritage groups compared with US-born NHW adults.

Conclusion

Sleep disparities varied by birthplace, Hispanic/Latino heritage and language preference, and each characteristic should be considered in sleep disparities research.

Keywords: sleep medicine, epidemiology, public health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Although limited by the cross-sectional study design, the use of recent nationally representative data consisting of a large sample size allowed for robust stratification by race/ethnicity, birthplace and language preference in this timely investigation of sleep disparities.

Data limitations included use of self-reports, use of a unidimensional proxy measure of language acculturation and potential for residual confounding.

However, study strengths included the assessment of several important sleep health dimensions and adjustment for multiple relevant confounders.

Introduction

Over one-third of United States (US) adults report insufficient sleep duration (<7 hours/night), and 50–70 million adults have a sleep disorder.1 2 Related to the high prevalence of poor sleep as well as its association with an increased risk of a variety of poor mental and physical health outcomes, poor sleep is recognised as a public health problem by the Institute of Medicine.1 In addition to being a burden in the overall US population, poor sleep health has been shown to vary by social determinants of health with disadvantaged populations being more likely to have worse objective and subjective sleep compared with populations with greater social advantages.3 4

Poor sleep disproportionately affects certain racial/ethnic minority groups compared with non-Hispanic white (NHW) people3 and may partially explain racial/ethnic disparities in poor health indicators like obesity.5–7 However, studies of racial/ethnic disparities in sleep to date may be limited by imprecise measurement of characteristics related to the social construct of race/ethnicity. For instance, evidence suggests that certain Hispanic/Latino heritage groups (eg, Puerto Rican adults) but not others (eg, Mexican adults) are more likely to report worse sleep compared with NHW adults.4 However, heterogeneous heritage groups within the Hispanic/Latino community are often combined into one category.4 8–10 Further, the reference group of NHW adults is also heterogeneous and usually comprises both US-born and foreign-born NHW adults despite evidence of sleep differences between the two groups.9 11 These studies suggested a lower unadjusted prevalence of habitual sleep duration of <7 hours among foreign-born compared with US-born NHW9 adults and that in the overall population of US adults, foreign-born individuals had higher odds of self-reported 7–8 hours of habitual sleep duration than US-born individuals after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviours and clinical characteristics.11 However, studies comparing other dimensions of sleep health by nativity among NHW adults are sparse.

As illustrated by the socioecological framework, both an individual’s characteristics and social context should be considered to better understand health behaviours and outcomes.12 Therefore, in addition to individual characteristics like birthplace, ethnicity and cultural background, consideration of the social environment related to culture (eg, language spoken with friends) in studies of racial/ethnic disparities is important. For instance, language acculturation is a strong indicator of overall acculturation that is hypothesised to influence disparities in health behaviours,13 14 and has been widely used as a proxy for overall acculturation.15 However, results regarding acculturation are mixed and generally suggest negative associations for certain health outcomes (eg, diet) but protective associations with other outcomes (eg, sleep).13 14 Relatedly, the lack of sleep disparities observed among Mexican Latino adults compared with NHW adults is hypothesised as due to lack of acculturation (eg, being born in Mexico and speaking Spanish at home) among Mexican adults.14 These findings relate to the ‘Hispanic Paradox’ that was originally observed in the cardiovascular disease (CVD) literature in which adults of Mexican origin in the United States of America (USA) were more likely to have risk factors for CVD yet were less likely to have CVD compared with their NHW counterparts. It has been hypothesised that acculturative factors like use of the Spanish language, of which the linguistic intricacies promote emotional identification and connection, may limit cumulative stress thus tempering the impact of risk factors on CVD outcomes.16 This exemplifies the ‘Hispanic Paradox’ which suggests that cultural characteristics shape perceptions and response to stressors, which may also be true in relation to sleep, and investigation is necessary.

Recent studies using nationally representative data have not yet simultaneously considered immigration status/birthplace, heterogeneity in heritage and language preference as modifying factors of racial/ethnic disparities in multiple sleep health characteristics among Hispanic/Latino adults compared with NHW adults.4 9 11 17–19 Although a recent study used National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data and reported variation in Hispanic/Latino–NHW differences in sleep duration by Hispanic/Latino heritage,20 the study did not have information regarding other important sleep quality characteristics and did not compare the sleep of foreign-born and US-born NHW adults.19 Further, studies that compared sleep among foreign-born and US-born NHW adults either combined NHW individuals with other racial/ethnic groups11 or provided unadjusted prevalence of sleep duration.9 Additional research inclusive of other sleep health dimensions and with adjustment for relevant confounders is warranted. To address important research gaps, we used the most recent data from a large, nationally representative sample of the US adult population of Hispanic/Latino and NHW adults to disentangle immigration status (birthplace) and heritage as contributors to sleep disparities. We sought to determine whether multiple sleep characteristics differed between (1) foreign-born and US-born NHW adults and (2) both foreign-born and US-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups compared with NHW individuals. We hypothesised better sleep among foreign-born versus US-born NHW adults and that Hispanic/Latino–NHW sleep disparities would vary by both nativity (ie, US-born versus foreign-born) and birthplace (eg, Mexico, Puerto Rico). In a secondary aim, we investigated language preference, a marker of acculturation, as a modifier. We hypothesised that Hispanic/Latino–NHW sleep disparities would be greater if Hispanic/Latino adults completed surveys in English versus Spanish.

Methods

National Health Interview Survey

The NHIS is the largest annually administered cross-sectional, in-person household survey in the USA. NHIS protocols are described in detail elsewhere.21 Briefly, NHIS uses a multistage probability sampling design to obtain a nationally representative sample of the non-institutionalised civilian population of children and adults in the USA. After recruitment, trained interviewers used computer-assisted personal interviewing to obtain health-related data from participants.

Study population

We pooled self-reported NHIS data collected from survey years 2004–2017, which were merged by the Integrated Health Interview Series.22 The overall response rate was 80% for adults (range: 74.2% in 2008–83.8% in 2004). Eligible participants were aged ≥18 years and self-identified as either NHW alone or Hispanic/Latino of any race. In this analysis, we focused on NHW and Hispanic/Latino of any race participants because they represent the majority and largest ethnic minority populations in the USA. Of 329 279 participants, ineligible participants were excluded, sequentially, if data were missing or implausible for sleep duration (≤2 or ≥23 hours; 2.2%) or birthplace (0.1%) or were currently pregnant (0.9%) (online supplemental figure 1). Hispanic/Latino participants who reported ‘other’ or multiple ethnicities (1.4%) were excluded because study objectives were to distinguish between Hispanic/Latino heritage groups. After excluding participants with missing data on potential confounders (18.1%), the final analytical sample comprised 254 699 participants.

bmjopen-2020-047834supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development and design of this study.

Measures

Race/ethnicity

Participants were asked, ‘What race do you consider yourself to be?’ with response options that met the Office of Management Budget Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and Administrative Reporting.23 Participants provided a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response to ‘Do you consider yourself to be Hispanic or Latino?’. Participants who self-identified as White race alone and non-Hispanic were categorised as NHW. Only region of birth (eg, Europe) was available among NHW participants (online supplemental table 1), which prevented measurement of national heritage among NHW participants. Participants of any race who self-identified as Hispanic/Latino were asked to provide Hispanic origin, ancestry or heritage with response options of Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Mexican and Central/South American.

Multiple sleep characteristics

We defined sleep characteristics categorically based on evidence so that results could serve as potential intervention targets. Participants responded to the following question: ‘On average, how many hours of sleep do you get in a 24-hour period?’. Reported values ≥30 min were rounded up to the nearest hour and values of <30 min were rounded down to the nearest hour; NHIS provided average sleep duration in whole numbers.21 Using evidence-based recommendations,24 we defined two non-mutually exclusive levels of short sleep duration: very short (≤5 hours) and short (<7 hours). Long sleep duration may be associated with worse health or be an artefact of poor health; therefore, we defined long sleep as >9 hours and recommended sleep as 7–9 hours.25

During survey years 2013–2017, participants reported the number of times they had trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, non-restorative sleep (awoke not feeling rested) and sleep medication during the week prior to the interview. We defined frequent trouble falling asleep, frequent trouble staying asleep, non-restorative sleep and sleep medication use as reports of ≥3 nights (or days) per week versus <3 nights (or days) per week.

Birthplace

Participants were asked ‘Where were you born?’. Birthplace included dichotomous categories of US-born (born in a US state or the District of Colombia (DC)) or foreign-born/island-born (not born in a US state or DC, born in a US territory (including Puerto Rico), or born outside of the USA and US territories).

Language of interview

Language is an important dimension of acculturation associated with health behaviours (eg, smoking) among Hispanics/Latinos.13 Participants selected the language in which they wanted to complete the NHIS interview. Language of interview was the assumed language preference, and we derived a proxy three-level language acculturation variable: English (high acculturation), English and Spanish (medium acculturation), or Spanish (low acculturation).

Potential confounders

Parameterisations of each potential confounder are listed in table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics included age category, sex/gender, annual household income, educational attainment, unemployed/not in the labour force, 2000 Standard Occupational Classification categories for longest held occupation, marital/cohabitating status, time in the USA and Census region of residence. Health behaviours included smoking status, physical activity based on the Guidelines for Americans26 and alcohol consumption. Clinical characteristics included body mass index (BMI) category calculated from self-reported height and weight,27 serious psychological distress,28 and self-report of physician-diagnosed dyslipidaemia (available for survey years 2011–2017), hypertension, pre-diabetes or diabetes, and cancer. Additionally, we categorised ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health (yes vs no), a dichotomised version of the American Heart Association’s metric that includes meeting all of the following criteria: never smoker/quit smoking in the prior 12 months, normal BMI, and no report of physician diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, or pre-diabetes/diabetes.29

Table 1.

Age-standardised sociodemographic characteristics among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latino adults, National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017 (N=254 669)*

| Race/ethnicity and heritage | Overall | White (n=207 154) |

Mexican (n=30 100) |

Puerto Rican (n=5077) |

Cuban (n=2518) |

Dominican (n=1658) |

Central/South American (n=8162) | ||||||||||||

| Nativity | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) |

|

| n (%) | 254 699 | 207 154 (81) | 198 297 (96) |

8857 (4) |

30 100 (12) |

14 282 (47) |

15 818 (53) |

5077 (2) |

2544 (50) |

2533 (50) |

2518 (1) |

559 (22) |

1959 (78) |

1658 (1) |

264 (16) |

1394 (84) |

8162 (3) |

1113 (14) |

7049 (86) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||||||||||||

| Age, mean±SE (years) | 46.8±0.9 | 48.0±0.1 | 47.9±0.1 | 48.7±0.2 | 39.4±0.2 | 38.1±0.2 | 40.5±0.2 | 43.0±0.3 | 37.6±0.3 | 49.2±0.5 | 47.8±0.4 | 35.8±0.8 | 51.9±0.5 | 41.8±0.5 | 30.8±0.9 | 44.6±0.5 | 40.4±0.2 | 30.1±0.4 | 42.2±0.2 |

| Female (%) | 49 | 50 | 50 | 49 | 45 | 49 | 40 | 48 | 47 | 48 | 44 | 42 | 44 | 56 | 53 | 57 | 49 | 55 | 48 |

| Annual household income (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| <$35 000 | 30 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 44 | 37 | 51 | 46 | 35 | 52 | 42 | 25 | 45 | 54 | 36 | 56 | 43 | 24 | 44 |

| $35 000–$74 999 | 33 | 32 | 32 | 29 | 34 | 35 | 34 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 29 | 34 | 30 | 38 | 30 | 34 | 39 | 34 |

| ≥$75 000 | 37 | 40 | 40 | 44 | 21 | 29 | 15 | 24 | 33 | 17 | 26 | 46 | 21 | 16 | 26 | 14 | 23 | 37 | 21 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||||||||||||

| <High school | 11 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 40 | 19 | 60 | 25 | 13 | 30 | 14 | 4 | 15 | 36 | 10 | 38 | 27 | 7 | 29 |

| High school graduate | 29 | 28 | 29 | 22 | 28 | 34 | 22 | 30 | 31 | 29 | 32 | 18 | 36 | 25 | 16 | 27 | 27 | 18 | 27 |

| Some college | 30 | 31 | 31 | 26 | 22 | 33 | 12 | 27 | 35 | 23 | 26 | 39 | 22 | 23 | 55 | 20 | 23 | 36 | 22 |

| ≥College | 30 | 33 | 32 | 45 | 10 | 14 | 6 | 18 | 22 | 18 | 29 | 39 | 26 | 16 | 20 | 14 | 23 | 39 | 22 |

| Unemployed/not in the labour force (%) | 38 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 40 | 36 | 46 | 43 | 49 | 37 | 33 | 37 | 40 | 47 | 39 | 33 | 27 | 33 |

| Occupational class (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Professional/ management | 21 | 22 | 22 | 27 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 12 | 17 | 9 | 18 | 32 | 15 | 9 | 20 | 7 | 11 | 24 | 10 |

| Support services | 35 | 46 | 46 | 45 | 31 | 44 | 19 | 41 | 45 | 39 | 40 | 49 | 37 | 39 | 52 | 37 | 34 | 54 | 32 |

| Labourers | 45 | 31 | 32 | 28 | 60 | 43 | 76 | 47 | 38 | 52 | 42 | 19 | 48 | 53 | 28 | 55 | 55 | 22 | 58 |

| Marital/cohabiting status (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Married/living with partner or cohabitating | 65 | 65 | 65 | 68 | 64 | 58 | 70 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 65 | 69 | 67 | 51 | 43 | 52 | 60 | 51 | 62 |

| Divorced/widowed/no live-in partner | 21 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 20 | 26 | 23 | 28 | 22 | 12 | 23 | 32 | 37 | 33 | 24 | 25 | 24 |

| Single/no live-in partner | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 11 | 19 | 21 | 16 | 14 | 19 | 10 | 17 | 20 | 14 | 16 | 24 | 14 |

| Language of interview (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| English | 95 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 64 | 91 | 39 | 81 | 91 | 73 | 45 | 85 | 36 | 45 | 88 | 40 | 54 | 88 | 51 |

| English and Spanish | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 6 | 23 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 16 | 7 | 16 |

| Spanish | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 2 | 38 | 11 | 3 | 16 | 45 | 7 | 54 | 42 | 3 | 46 | 30 | 5 | 33 |

| Time in the USA (states) (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| ≥15 years | 24 | 22 | 100 | 78 | 77 | 100 | 77 | 80 | 100 | 80 | 66 | 100 | 66 | 75 | 100 | 75 | 70 | 100 | 70 |

| <15 years | 76 | 78 | 0 | 22 | 23 | 0 | 23 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 34 | 0 | 34 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| Region of residence (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 18 | 19 | 19 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 50 | 46 | 49 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 75 | 54 | 77 | 23 | 13 | 23 |

| Midwest | 25 | 28 | 29 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| South | 34 | 34 | 34 | 26 | 35 | 40 | 31 | 32 | 31 | 36 | 82 | 68 | 85 | 21 | 38 | 20 | 43 | 37 | 44 |

| West | 22 | 20 | 19 | 29 | 53 | 49 | 56 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 30 | 45 | 28 |

Data are presented as percentages or means±SEs. All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. All estimates except for age are age-standardised to the US 2010 population.

*Data are presented as unweighted n’s and weighted percentages. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to missing values or rounding.

SE, standard error.

Statistical analysis

All analyses accounted for the NHIS complex survey design by using survey weights to account for non-response and oversampling of certain groups (eg, racial/ethnic minorities, older adults). We applied direct age standardisation using the 2010 Census as the reference population to estimate descriptive statistics (tables 1–3). Poisson regressions with robust variance estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs for each sleep characteristic among foreign-born NHW individuals and both US-born and foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups, separately, compared with US-born NHW individuals (table 4). With the same approach, we estimated PRs and 95% CIs for each sleep characteristic among each US-born and foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage group, separately, compared with foreign-born NHW individuals (table 5).

Table 2.

Age-standardised health behaviour characteristics among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latino adults, National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017 (N=254 669)*

| Race/ethnicity and heritage | Overall | White (n=207 154) |

Mexican (n=30 100) |

Puerto Rican (n=5077) |

Cuban (n=2518) |

Dominican (n=1658) |

Central/South American (n=8162) | ||||||||||||

| Nativity | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) |

|

| n (%) | 254 699 | 207 154 (81) | 198 297 (96) |

8857 (4) |

30 100 (12) |

14 282 (47) |

15 818 (53) |

5077 (2) |

2544 (50) |

2533 (50) |

2518 (1) |

559 (22) |

1959 (78) |

1658 (1) |

264 (16) |

1394 (84) |

8162 (3) |

1113 (14) |

7049 (86) |

| Health behaviours | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sleep duration (%)† | |||||||||||||||||||

| ≤5 hours | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| <7 hours | 29 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 31 | 25 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 29 | 30 | 28 | 34 | 31 | 34 | 31 | 30 | 31 |

| 7–9 hours | 67 | 67 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 64 | 70 | 56 | 57 | 57 | 68 | 69 | 69 | 63 | 67 | 64 | 67 | 68 | 67 |

| >9 hours | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sleep characteristics (%)§ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Trouble falling asleep (≥3 nights) |

20 | 21 | 21 | 17 | 19 | 22 | 17 | 27 | 26 | 27 | 18 | 30 | 16 | 19 | 15 | 19 | 18 | 31 | 16 |

| Trouble staying asleep (≥3 nights) | 29 | 30 | 30 | 23 | 22 | 26 | 18 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 20 | 33 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 20 | 28 | 19 |

| Sleep medication use (≥3 nights) |

11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 5 |

| Non-restorative sleep: did not wake feeling rested (≥3 days) |

64 | 63 | 63 | 66 | 65 | 63 | 67 | 61 | 63 | 61 | 66 | 55 | 67 | 63 | 52 | 64 | 67 | 71 | 67 |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Never/quit >12 months prior‡ | 80 | 79 | 79 | 83 | 86 | 84 | 88 | 81 | 79 | 81 | 84 | 88 | 84 | 93 | 92 | 93 | 91 | 86 | 91 |

| Quit ≤12 months ago | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Current | 18 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 11 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 8 |

| Leisure-time physical activity (PA) (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Never/unable | 33 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 44 | 39 | 48 | 47 | 39 | 52 | 52 | 35 | 56 | 59 | 57 | 60 | 43 | 30 | 45 |

| Does not meet PA guidelines | 19 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 20 | 17 |

| Meets PA guidelinesঠ| 47 | 49 | 49 | 51 | 38 | 43 | 34 | 37 | 43 | 32 | 36 | 56 | 31 | 27 | 30 | 26 | 39 | 50 | 38 |

| Alcohol consumption (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lifetime abstainer | 16 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 25 | 19 | 30 | 26 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 18 | 32 | 35 | 21 | 36 | 29 | 15 | 30 |

| Former | 16 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 19 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 17 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 17 |

| Current | 68 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 57 | 64 | 51 | 56 | 65 | 51 | 60 | 74 | 57 | 52 | 62 | 50 | 55 | 75 | 53 |

Data are presented as percentages. All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. All estimates are age-standardised to the US 2010 population.

*Data are presented as unweighted n’s and weighted percentages. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to missing values or rounding.

†Short sleep duration categories of ≤5 hours and <7 hours are non-mutually exclusive.

‡Indicator of ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health.

§ Trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, sleep medication use and non-restorative sleep were measured during the survey years 2013–2017.

¶Meets PA guidelines defined as ≥150 min/week of moderate intensity, ≥75 min/week of vigorous intensity or ≥150 min/week of moderate+vigorous intensity PA.

Table 3.

Age-standardised clinical characteristics among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latino adults, National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017 (N=254 669)*

| Race/ethnicity and heritage | Overall | White (n=207 154) |

Mexican (n=30 100) |

Puerto Rican (n=5077) |

Cuban (n=2518) |

Dominican (n=1658) |

Central/South American (n=8162) | ||||||||||||

| Nativity | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) | All | US-born (yes) | US-born (no) |

|

| n (%) | 254 699 | 207 154 (81) | 198 297 (96) |

8857 (4) |

30 100 (12) |

14 282 (47) |

15 818 (53) |

5077 (2) |

2544 (50) |

2533 (50) |

2518 (1) |

559 (22) |

1959 (78) |

1658 (1) |

264 (16) |

1394 (84) |

8162 (3) |

1113 (14) |

7049 (86) |

| Clinical characteristics (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Body mass index (BMI) (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Normal (BMI 18.5–<24.9 kg/m2)† |

34 | 35 | 35 | 40 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 22 | 27 | 33 | 40 | 31 | 30 | 17 | 32 | 31 | 33 | 31 |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) |

37 | 36 | 36 | 39 | 41 | 37 | 44 | 39 | 40 | 39 | 41 | 29 | 44 | 44 | 49 | 43 | 45 | 38 | 45 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2) |

29 | 29 | 29 | 21 | 35 | 38 | 32 | 36 | 38 | 34 | 26 | 31 | 25 | 26 | 34 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 24 |

| Serious psychological distress‡ (% yes) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Dyslipidaemia (% yes)§† | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 | 51 | 49 | 53 | 56 | 60 | 52 | 52 | 58 | 53 | 54 | 45 | 54 | 51 | 49 | 52 |

| Hypertension (% yes)† | 34 | 34 | 35 | 30 | 34 | 37 | 32 | 37 | 35 | 39 | 33 | 23 | 35 | 37 | 41 | 37 | 28 | 27 | 29 |

| Pre-diabetes/diabetes (% yes)† | 15 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 24 | 25 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 24 | 14 | 19 | 15 | 20 | 29 | 20 | 15 | 12 | 16 |

| ‘Ideal’ cardiovascular health¶ (% yes) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 9 |

| Cancer (% yes) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 5 |

Data are presented as percentages. All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. All estimates are age-standardised to the US 2010 population.

*Data are presented as unweighted n’s and weighted percentages. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to missing values or rounding.

†Indicator of ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health.

‡Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale score ≥13.

§Dyslipidaemia defined as high cholesterol in the 12 months prior to interview. Available for survey years 2011–2017.

¶‘Ideal’ cardiovascular health includes never smoking/quit >12 months prior to interview, BMI 18.5–<25 kg/m2, meeting physical activity guidelines, and no prior diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, hypertension or diabetes/pre-diabetes.

Table 4.

Fully adjusted prevalence ratios of sleep characteristics for foreign-born non-Hispanic White adults and Hispanic/Latino heritage groups of adults compared with US-born non-Hispanic White adults, National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017 (N=254 669)

| Group (n) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sleep duration (reference: recommended (7–9 hours)) |

Sleep quality in the past week | ||||||

| Very short (≤5 hours) (n=21 227) |

Short (<7 hours) (n=75 139) |

Long (>9 hours) (n=9190) |

Trouble falling asleep (≥3 nights) (n=22 038) |

Trouble staying asleep (≥3 nights) (n=30 013) |

Non-restorative sleep (≥3 days) (n=46 103) |

Sleep medication use (≥3 nights) (n=11 097) |

|

| US-born non-Hispanic White adults (n=198 297) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

|

Foreign-born non-Hispanic White adults (n=8857) |

1.03 (0.93 to 1.13) |

1.03 (0.99 to 1.08) |

1.07 (0.92 to 1.24) |

1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) |

1.27

(1.17 to 1.37) |

1.06

(1.00 to 1.12) |

1.34

(1.16 to 1.55) |

| Mexican adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=30 100) |

0.76

(0.71 to 0.81) |

0.87

(0.85 to 0.90) |

0.87

(0.79 to 0.96) |

0.77

(0.72 to 0.82) |

0.65

(0.62 to 0.69) |

0.90

(0.87 to 0.94) |

0.52

(0.46 to 0.58) |

| US-born (yes) (n=14 282) |

1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) |

1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) |

0.98 (0.87 to 1.11) |

0.92

(0.85 to 0.99) |

0.80

(0.74 to 0.85) |

0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) |

0.66

(0.58 to 0.76) |

| US-born (no) (n=15 818) |

0.52

(0.47 to 0.57) |

0.70

(0.67 to 0.73) |

0.75

(0.66 to 0.85) |

0.59

(0.54 to 0.65) |

0.50

(0.46 to 0.55) |

0.81

(0.77 to 0.85) |

0.36

(0.29 to 0.43) |

| Puerto Rican adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=5077) |

1.39

(1.26 to 1.53) |

1.20

(1.14 to 1.25) |

1.00 (0.84 to 1.20) |

1.05 (0.95 to 1.17) |

0.91 (0.83 to 1.00) |

0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) |

0.99 (0.85 to 1.15) |

| US-born (yes) (n=2544) |

1.44

(1.27 to 1.64) |

1.23

(1.16 to 1.31) |

1.08 (0.84 to 1.37) |

1.05 (0.91 to 1.21) |

0.97 (0.85 to 1.12) |

1.00 (0.92 to 1.09) |

0.96 (0.77 to 1.21) |

| US-born (no) (n=2533) |

1.32

(1.16 to 1.51) |

1.15

(1.08 to 1.24) |

0.94 (0.74 to 1.19) |

1.06 (0.92 to 1.22) |

0.84

(0.73 to 0.97) |

0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) |

1.02 (0.83 to 1.25) |

| Cuban adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=2518) |

0.83

(0.70 to 0.99) |

0.89

(0.81 to 0.98) |

0.69

(0.55 to 0.87) |

0.78

(0.62 to 0.97) |

0.70

(0.58 to 0.83) |

0.90 (0.82 to 1.00) |

0.68

(0.53 to 0.89) |

| US-born (yes) (n=559) |

0.93 (0.66 to 1.29) |

1.04 (0.89 to 1.21) |

0.71 (0.34 to 1.47) |

0.97 (0.72 to 1.31) |

0.94 (0.70 to 1.26) |

0.98 (0.82 to 1.17) |

0.98 (0.57 to 1.69) |

| US-born (no) (n=1959) |

0.81

(0.66 to 0.99) |

0.85

(0.76 to 0.95) |

0.69

(0.54 to 0.88) |

0.71

(0.53 to 0.95) |

0.63

(0.49 to 0.79) |

0.87

(0.78 to 0.98) |

0.61

(0.43 to 0.85) |

| Dominican adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=1658) |

0.90 (0.76 to 1.08) |

0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) |

0.72 (0.49 to 1.05) |

0.76

(0.62 to 0.92) |

0.67

(0.55 to 0.83) |

0.93 (0.82 to 1.05) |

0.81 (0.54 to 1.20) |

| US-born (yes) (n=264) |

1.09 (0.68 to 1.74) |

1.09 (0.85 to 1.40) |

1.15 (0.49 to 2.73) |

0.73 (0.47 to 1.13) |

0.97 (0.65 to 1.43) |

0.98 (0.77 to 1.26) |

0.64 (0.31 to 1.31) |

| US-born (no) (n=1394) |

0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) |

0.88

(0.79 to 0.98) |

0.60

(0.38 to 0.93) |

0.76

(0.62 to 0.95) |

0.61

(0.48 to 0.78) |

0.92 (0.79 to 1.07) |

0.84 (0.54 to 1.30) |

| Central/South American adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=8162) |

0.78

(0.71 to 0.87) |

0.93

(0.89 to 0.98) |

0.68

(0.56 to 0.83) |

0.76

(0.67 to 0.87) |

0.65

(0.58 to 0.73) |

0.89

(0.83 to 0.94) |

0.42

(0.34 to 0.53) |

| US-born (yes) (n=1113) |

1.30

(1.03 to 1.65) |

1.18

(1.04 to 1.33) |

0.82 (0.51 to 1.30) |

1.21 (0.96 to 1.51) |

0.98 (0.73 to 1.30) |

1.05 (0.93 to 1.19) |

0.64 (0.38 to 1.10) |

| US-born (no) (n=7049) |

0.72

(0.64 to 0.80) |

0.89

(0.85 to 0.94) |

0.66

(0.54 to 0.82) |

0.68

(0.59 to 0.77) |

0.59

(0.53 to 0.67) |

0.85

(0.80 to 0.90) |

0.39

(0.30 to 0.50) |

Adjusted for age (18–30, 31–49, 50–64, 65+ years), sex/gender (male, female), annual household income (<$35 000, $35 000–$74 999, $75 000+), educational attainment (<high school, high school graduate, some college, ≥college), unemployed/not in the labour force (yes, no), occupational class (professional/management, support services, labourers), marital/cohabitating status (married/cohabitating, divorced/widowed, single), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), serious psychological distress (Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale score ≥13), ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health (never smoking/quit >12 months prior to interview, BMI <25 kg/m2, meeting physical activity guidelines, and no prior diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, or diabetes/pre-diabetes), and cancer.

All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. Very short and short sleep are non-mutually exclusive sleep duration categories. Trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, sleep medication use and non-restorative sleep were measured during the survey years 2013–2017.

Bold values indicate statistical significance at a two-sided p-value of 0.05.

BMI, body mass index; Ref, reference.

Table 5.

Fully adjusted prevalence ratios of sleep characteristics for Hispanic/Latino heritage groups of adults compared with foreign-born non-Hispanic White adults, National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017 (N=56 372)

| Group (n) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sleep duration (reference: recommended (7–9 hours)) |

Sleep quality in the past week | ||||||

| Very short (≤5 hours) (n=4115) |

Short (<7 hours) (n=14 048) |

Long (>9 hours) (n=1586) |

Trouble falling asleep (≥3 nights) (n=3431) |

Trouble staying asleep (≥3 nights) (n=3520) |

Non-restorative sleep (≥3 days) (n=7734) |

Sleep medication use (≥3 nights) (n=1073) |

|

|

Foreign-born non-Hispanic White adults (n=8857) |

Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Mexican adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=30 100) |

1.10 (0.96 to 1.26) |

1.12

(1.05 to 1.18) |

1.06 (0.86 to 1.31) |

0.92 (0.81 to 1.05) |

0.87

(0.78 to 0.97) |

1.06 (0.99 to 1.14) |

0.92 (0.73 to 1.14) |

| US-born (yes) (n=14 282) |

1.17

(1.02 to 1.34) |

1.19

(1.12 to 1.26) |

1.04 (0.84 to 1.29) |

1.00 (0.87 to 1.14) |

0.97 (0.86 to 1.10) |

1.07 (0.99 to 1.15) |

0.98 (0.78 to 1.23) |

| US-born (no) (n=15 818) |

0.89 (0.73 to 1.08) |

0.98 (0.90 to 1.06) |

1.05 (0.81 to 1.36) |

0.78

(0.66 to 0.94) |

0.72

(0.62 to 0.84) |

1.02 (0.93 to 1.12) |

0.68

(0.48 to 0.96) |

| Puerto Rican adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=5077) |

1.75

(1.51 to 2.02) |

1.34

(1.25 to 1.44) |

1.13 (0.88 to 1.44) |

1.19

(1.03 to 1.39) |

1.14 (0.99 to 1.31) |

1.06 (0.96 to 1.16) |

1.33

(1.07 to 1.64) |

| US-born (yes) (n=2544) |

1.85

(1.54 to 2.22) |

1.39

(1.27 to 1.51) |

1.33 (0.95 to 1.85) |

1.20 (0.99 to 1.46) |

1.22

(1.02 to 1.46) |

1.06 (0.95 to 1.18) |

1.32

(1.01 to 1.73) |

| US-born (no) (n=2533) |

1.58

(1.32 to 1.90) |

1.27

(1.16 to 1.39) |

1.02 (0.77 to 1.35) |

1.22

(1.01 to 1.46) |

1.09 (0.91 to 1.30) |

1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) |

1.41

(1.09 to 1.83) |

| Cuban adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=2518) |

0.97 (0.76 to 1.22) |

0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) |

0.69

(0.49 to 0.97) |

0.92 (0.70 to 1.20) |

0.93 (0.76 to 1.15) |

1.03 (0.90 to 1.18) |

1.09 (0.77 to 1.55) |

| US-born (yes) (n=559) |

1.03 (0.69 to 1.53) |

1.15 (0.96 to 1.37) |

0.83 (0.39 to 1.75) |

1.14 (0.79 to 1.65) |

1.17 (0.84 to 1.65) |

1.05 (0.85 to 1.29) |

1.63 (0.91 to 2.93) |

| US-born (no) (n=1959) |

0.94 (0.72 to 1.22) |

0.92 (0.81 to 1.05) |

0.66

(0.46 to 0.94) |

0.82 (0.59 to 1.14) |

0.85 (0.65 to 1.10) |

1.04 (0.89 to 1.21) |

0.96 (0.63 to 1.45) |

| Dominican adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=1658) |

1.12 (0.89 to 1.43) |

1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) |

0.91 (0.57 to 1.45) |

0.88 (0.68 to 1.13) |

0.94 (0.72 to 1.23) |

1.00 (0.87 to 1.15) |

1.03 (0.67 to 1.59) |

| US-born (yes) (n=264) |

1.40 (0.82 to 2.41) |

1.24 (0.97 to 1.60) |

1.80 (0.68 to 4.79) |

0.82 (0.51 to 1.31) |

1.25 (0.81 to 1.93) |

1.01 (0.78 to 1.32) |

0.97 (0.42 to 2.20) |

| US-born (no) (n=1394) |

1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) |

0.96 (0.84 to 1.10) |

0.73 (0.45 to 1.20) |

0.88 (0.68 to 1.16) |

0.87 (0.65 to 1.18) |

0.99 (0.84 to 1.18) |

1.02 (0.64 to 1.63) |

| Central/South American adults | |||||||

| Overall (n=8162) |

1.00 (0.86 to 1.17) |

1.10

(1.02 to 1.17) |

0.76 (0.57 to 1.02) |

0.94 (0.78 to 1.13) |

0.89 (0.76 to 1.04) |

1.02 (0.95 to 1.11) |

0.69

(0.51 to 0.91) |

| US-born (yes) (n=1113) |

1.42

(1.06 to 1.92) |

1.30

(1.13 to 1.49) |

1.02 (0.59 to 1.75) |

1.27 (0.96 to 1.67) |

1.14 (0.86 to 1.52) |

1.08 (0.94 to 1.25) |

0.95 (0.56 to 1.62) |

| US-born (no) (n=7049) |

0.92 (0.78 to 1.08) |

1.05 (0.98 to 1.13) |

0.77 (0.56 to 1.05) |

0.84 (0.69 to 1.02) |

0.84

(0.72 to 0.99) |

1.00 (0.92 to 1.09) |

0.64

(0.47 to 0.88) |

Adjusted for age (18–30, 31–49, 50–64, 65+ years), sex/gender (male, female), annual household income (<$35 000, $35 000–$74 999, $75 000+), educational attainment (<high school, high school graduate, some college, ≥college), unemployed/not in the labour force (yes, no), occupational class (professional/management, support services, labourers), marital/cohabitating status (married/cohabitating, divorced/widowed, single), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), serious psychological distress (Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale score ≥13), ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health (never smoking/quit >12 months prior to interview, BMI <25 kg/m2, meeting physical activity guidelines, and no prior diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, or diabetes/pre-diabetes), and cancer.

All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. Very short and short sleep are non-mutually exclusive sleep duration categories. Trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, sleep medication use and non-restorative sleep were measured during the survey years 2013–2017.

Bold values indicate statistical significance at a two-sided p-value of 0.05.

BMI, body mass index; Ref, reference.

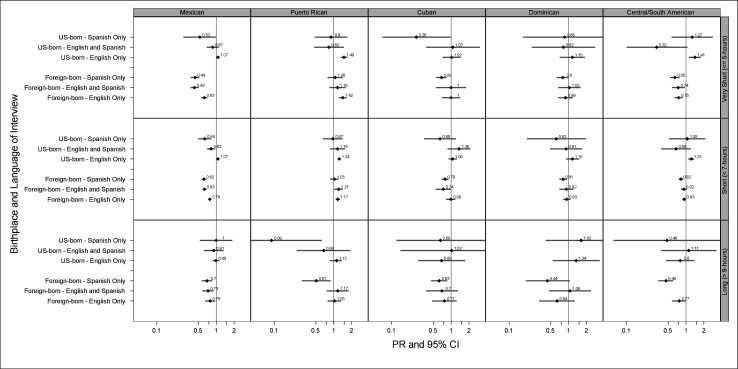

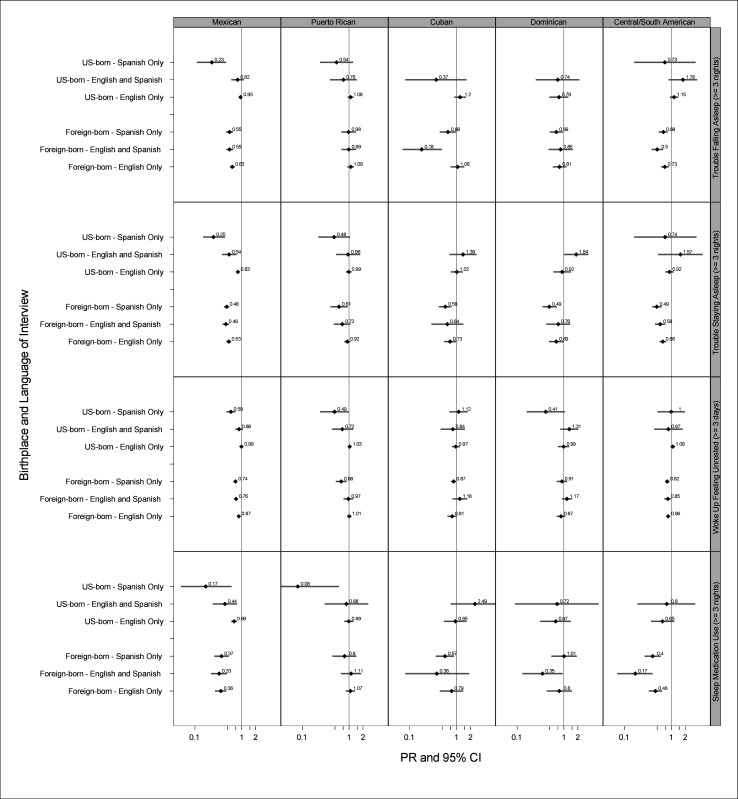

Models were adjusted for a priori potential confounders based on prior literature: age category, sex/gender, annual household income, educational attainment, employment status, occupational class, marital status, region of residence, alcohol consumption, serious psychological distress, ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health and cancer.2 4 9 11 19 30–34 Lastly, in a secondary analysis, we further stratified by language of interview (English, English and Spanish, and Spanish) as a proxy measure of language acculturation and compared sleep characteristics for each Hispanic/Latino heritage group of adults with US-born NHW adults (figures 1 and 2). Five separate sensitivity analyses, including adjustment for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate in all models, are described in table 6. We performed all analyses using Stata/SE V.15. A two-sided p value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Fully adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) of sleep duration and characteristics for Hispanic/Latino heritage groups of adults compared with non-Hispanic White adults by language acculturation status,** National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017. **Language acculturation categories include high (English only interview), medium (English and Spanish interview) and low (Spanish only interview). Adjusted for age (18–30, 31–49, 50–64, 65+ years), sex/gender (male, female), annual household income (<$35 000, $35 000–$74 999, $75 000+), educational attainment (<high school, high school graduate, some college, ≥college), unemployed/not in the labour force (yes, no), occupational class (professional/management, support services, labourers), marital/cohabitating status (married/cohabitating, divorced/widowed, single), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), serious psychological distress (Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale score ≥13), ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health (never smoking/quit >12 months prior to interview, body mass index <25 kg/m2, meeting physical activity guidelines, and no prior diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, or diabetes/pre-diabetes), and cancer. Very short and short sleep are non-mutually exclusive sleep duration categories. All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. Certain associations were not estimable due to small sample sizes and are, therefore, not provided (eg, long sleep duration among adults of Central/South American heritage with medium acculturation compared with non-Hispanic White adults).

Figure 2.

Fully adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) of sleep quality* characteristics for Hispanic/Latino heritage groups of adults compared with non-Hispanic White adults by language acculturation status,** National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017. *Trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, sleep medication use and non-restorative sleep were measured during the survey years 2013–2017. **Language acculturation categories include high (English only interview), medium (English and Spanish interview) and low (Spanish only interview). Adjusted for age (18–30, 31–49, 50–64, 65+ years), sex/gender (male, female), annual household income (<$35 000, $35 000–$74 999, $75 000+), educational attainment (<high school, high school graduate, some college, ≥college), unemployed/not in the labour force (yes, no), occupational class (professional/management, support services, labourers), marital/cohabitating status (married/cohabitating, divorced/widowed, single), region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), alcohol consumption (never, former, current), serious psychological distress (Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale score ≥13), ‘ideal’ cardiovascular health (never smoking/quit >12 months prior to interview, body mass index <25 kg/m2, meeting physical activity guidelines, and no prior diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, or diabetes/pre-diabetes) and cancer. All estimates are weighted for the survey’s complex sampling design. Certain associations were not estimable due to small sample sizes and are, therefore, not provided (eg, long sleep duration among adults of Central/South American heritage with medium acculturation compared with non-Hispanic White adults).

Table 6.

Summary of sensitivity analyses

| Sensitivity analysis number |

Purpose of sensitivity analysis | Method employed | Summary of results of sensitivity analysis |

| 1 | To adjust for multiple comparisons | When re-estimating the models in tables 4 and 5 and well as figures 1 and 2, we employed false discovery rate procedures. | In total, there were 427 p values in which 159 were significant in the original analysis. After the false discovery, p value correction, 127 of the 159 significant p values (80%) remained statistically significant (online supplemental tables 2 and 3 and online supplemental figure 2). Results were robust for comparisons between foreign-born and US-born NHW adults and for most results for comparisons with adults of Mexican and Puerto Rican heritage compared with NHW adults. |

| 2 | To investigate how results would be affected if we did not consider nativity/birthplace as a modifier of racial/ethnic differences in sleep | We combined both US-born and foreign-born participants; we then compared sleep characteristics among adults of Hispanic/Latino heritage versus NHW adults. | Combining foreign-born and US-born participants across both Hispanic/Latino heritage and NHW race/ethnicity would have missed important differences by nativity status (online supplemental table 3). For instance, the lower prevalence of non-recommended sleep duration observed among foreign-born Mexican versus US-born NHW adults (table 2) would either have been underestimated or not have been observed if participants were not stratified by birthplace. |

| 3 | To investigate how results would be affected if we considered sex/gender and age as potential modifiers39 | We stratified the original models by sex/gender (men, women) and by age category (18–30 years, 31–49 years, ≥50 years), separately. In models that were also stratified by language acculturation, we combined low and medium acculturation to increase sample sizes and improve statistical stability. | After stratification by sex/gender (online supplemental table 3), point estimates were slightly stronger among men versus women for sleep quality across comparisons with foreign-born NHW adults and for very short as well as short sleep across comparisons with non-US born Mexican adults. Sex/gender did not modify the remaining associations among Mexican or Puerto Rican adults. The differences among both foreign-born NHW and Mexican adults compared with US-born NHW adults that were observed in the main analysis were greater among younger and middle versus older aged adults (online supplemental table 4). Across comparisons with non-US-born NHW adults, there was little variation by sex/gender for Mexican and Puerto Rican adults, but the differences were greater among younger versus older aged adults (online supplemental tables 5 and 6). In analyses stratified by language acculturation, lower prevalence of shorter sleep duration among foreign-born Mexican compared with NHW adults was stronger for men versus women and for younger versus older adults (online supplemental tables 7 and 8). |

| 4 | To investigate how results would be affected if we adjusted for time in the USA in the comparisons between foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups and their NHW counterparts9 19 37 | Across comparisons of foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups with their foreign-born NHW counterparts, we additionally adjusted for time in the USA. | Results (online supplemental table 9) were consistent with the main analysis (table 3), which suggested that time spent in the USA was not a strong confounder across comparisons between foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups and their NHW counterparts. |

| 5 | To investigate how results would be affected if we used a different measure of acculturation in models9 19 | We separated foreign-born NHW adults and Hispanic/Latino heritage groups by a different metric of acculturation, time lived in the USA (<15 years in the USA, ≥15 years in the USA),9 19 37 when compared with US-born NHW adults. | Results (online supplemental table 10) were consistent with those of the language acculturation-stratified analyses (figure 1). |

NHW, non-Hispanic white.

Results

Study population characteristics

Among 254 669 participants, mean age±SE was 47±0.9 years (table 1). Most participants self-identified as NHW (81%) and the remainder as Hispanic/Latino of the following heritage: Mexican (12%), Puerto Rican (2%), Cuban (1%), Dominican (1%), Central/South American (3%). Most (96%) NHW and approximately half of Mexican (47%) and Puerto Rican (50%) participants were US-born. Most Cuban (78%), Dominican (84%) and Central/South American (86%) adults were foreign-born. We present but do not interpret results for the Central/South American heritage group because of within-group heritage heterogeneity.

The prevalence of health behaviour and clinical characteristics are presented in tables 2 and 3. The prevalence of short sleep was highest among adults of Puerto Rican descent (39%). Although similar to the prevalence of short sleep among NHW adults (29%) who showed little variation by nativity (28% US-born versus 27% foreign-born), short sleep prevalence was lowest among adults of Mexican descent (28%). Each Hispanic/Latino heritage group except adults of Puerto Rican descent was less likely than NHW adults to report poor sleep quality indicators (eg, trouble falling asleep) except non-restorative sleep. The prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, although low overall, was higher among NHW adults compared with other racial/ethnic/heritage groups, and prevalence varied by nativity status.

Foreign-born NHW adults compared with US-born NHW adults

Compared with US-born NHW adults, foreign-born NHW adults were not more likely to report non-recommended sleep duration (table 4), but were more likely to report trouble staying asleep (PR=1.27 (1.17 to 1.37)), non-restorative sleep (PR=1.06 (1.00 to 1.12)) and sleep medication use (PR=1.34 (1.16 to 1.55)). Results were robust after applying the false discovery rate multiple comparison procedure (table 6 and online supplemental material).

US-born and foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups compared with the US-born NHW group

Compared with US-born NHW adults, US-born Mexican adults were as likely to report non-recommended sleep duration; however, foreign-born Mexican adults were less likely to report non-recommended sleep duration (PRvery short=0.52 (0.47 to 0.57), PRshort=0.70 (0.67 to 0.73), PRlong=0.75 (0.66 to 0.85)). Overall, adults of Mexican descent were less likely to report trouble falling, trouble staying asleep, non-restorative sleep and sleep medication use compared with US-born NHW adults; however, racial/ethnic differences were larger across comparisons between foreign-born Mexican and US-born NHW adults. Results remained statistically significant after applying the false discovery rate multiple comparison procedure (table 6 and online supplemental material).

Overall, both US-born and foreign-born/island-born Puerto Rican adults were more likely than US-born NHW adults to report very short sleep (PR 1.39 (1.26 to 1.53)) and short sleep (PR=1.20 (1.14 to 1.25)) with little variation by nativity/birthplace. Similarly, there was negligible variation by birthplace for sleep quality characteristics among US-born and foreign-born/island-born Puerto Rican adults who were marginally less likely to report trouble staying asleep (PR=0.91 (0.83 to 1.00)) and no more likely to report other poor sleep quality characteristics compared with US-born NHW adults. Statistical significance remained after applying the false discovery rate multiple comparison procedure (table 6 and online supplemental material).

Small sample sizes resulted in wide CIs for US-born and foreign-born adults of Cuban and Dominican heritage. Adults of Cuban heritage, overall, were less likely to report non-recommended sleep duration and poor sleep quality characteristics compared with US-born NHW adults. However, only foreign-born adults of Cuban heritage had lower prevalence of short sleep and poor sleep quality characteristics. Generally, Dominican adults were less likely to report trouble falling asleep and no more likely to report non-restorative sleep or sleep medication use compared with US-born NHW adults. However, only foreign-born Dominican adults were less likely to report short sleep and trouble staying asleep.

US-born and foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups compared with the foreign-born NHW group

Compared with foreign-born NHW adults, US-born Mexican adults were more likely to report short sleep duration (PR=1.19 (1.12 to 1.26)) but foreign-born Mexican adults were no more likely. US-born Mexican adults were no more likely to report trouble staying asleep compared with foreign-born NHW adults (PR=0.97 (0.86 to 1.10)); however, foreign-born Mexican adults were less likely to report trouble staying asleep (PR=0.72 (0.62 to 0.84); table 5). Overall, Puerto Rican adults were more likely to report very short and short sleep duration, trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep and sleep medication use compared with foreign-born NHW adults with little evidence of variation by birthplace. Statistical significance for sleep duration results remained after false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons. Small sample sizes of US-born Cubans and Dominicans resulted in wide, often overlapping CIs limiting the ability to examine differences by birthplace.

Hispanic/Latino heritage groups compared with the US-born NHW group: modification by language of interview

Prevalence of non-recommended sleep duration among foreign-born Mexican adults compared with US-born NHW adults was lowest among subpopulations of foreign-born Mexican adults with English/Spanish and Spanish versus English interviews (figure 1). Additionally, among Mexican adults, overall, those with Spanish interviews had the lowest prevalence of poor sleep quality compared with US-born NHW adults (figure 2). Among adults of Puerto Rican descent, overall, those with Spanish interviews had similar prevalence of shorter sleep duration and suggestively better sleep quality characteristics compared with US-born NHW adults. Among adults of Cuban and Dominican heritage, although imprecise, patterns of variation by language of interview were similar to those among Mexican adults. Results of the remaining sensitivity analyses are provided in table 6.

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample of NHW and Hispanic/Latino adults, we found sleep disparities between foreign-born and US-born NHW adults, and differences in sleep characteristics varied by Hispanic/Latino heritage, birthplace/nativity and language of interview among Hispanic/Latino adults compared with NHW adults. Although results among NHW adults were counter to our hypothesis, results for Latinos were congruent with our hypothesis. Compared with their US-born NHW counterparts, foreign-born NHW adults had a higher prevalence of poor sleep quality indicators. Although habitual sleep duration was similar between US-born Mexican adults and their NHW counterparts, foreign-born Mexican adults reported better sleep duration than US-born NHW adults. Better sleep quality among foreign-born Mexican adults compared with US-born NHW adults was of greater magnitude than the better sleep quality reported by US-born Mexican adults compared with their US-born NHW counterparts. Puerto Rican adults generally reported worse sleep duration compared with NHW adults. Acknowledging small sample sizes, foreign-born adults of Cuban and Dominican heritage generally had even better sleep duration and quality compared with US-born NHW adults than US-born adults of Cuban and Dominican heritage. Overall, Spanish language preference may be associated with increasingly better sleep among Hispanic/Latino heritage groups.

Our results are consistent with prior studies that suggest differences in sleep by birthplace and language preference. Most studies report better subjective sleep among foreign-born compared with US-born adults,10 11 17 18 and our results were generally in agreement across each Hispanic/Latino heritage group except Puerto Rican adults. Further, our results suggesting that birthplace is a modifier of sleep duration are congruent with findings of both an earlier study of NHIS data and the multisite Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) where short sleep duration and sleep complaints were more often reported by US-born adults versus their foreign-born counterparts.10 17 Results of SWAN also suggested that language acculturation may mediate differences in sleep complaints, and similarly, completion of interviews in English versus Spanish was positively associated with probable clinically significant insomnia in a separate study of pregnant Latina women in San Diego.10 35 Like our study, a different nationally representative study found no differences in short sleep duration among US-born Mexican adults compared with their US-born NHW counterparts but lower odds of short sleep duration among foreign-born Mexican compared with NHW adults.4 Prior studies either comprised solely individuals of Mexican heritage or used a heterogeneous Hispanic/Latino category.4 10 17 18 35 Importantly, our study extended this literature by illustrating heterogeneity across Hispanic/Latino heritage groups.36

Differences in study populations, the grouping of Hispanic/Latino adults, and sleep assessments likely contribute differences between results of our and some prior studies. Among Mexican women aged 21–40 years in Northern California, birthplace and language preference were not associated with sleep disturbances.37 In a prior study using 2012 NHIS data, short sleep was more prevalent among US-born Hispanic/Latino adults compared with US-born NHW adults, and there were no differences in sleep duration between foreign-born Hispanic/Latino and NHW adults.9 However, all individuals of Hispanic/Latino heritage were combined. In a recent study using 2004–2017 NHIS data, investigators reported higher odds of short sleep among all Hispanic/Latino heritage groups except US-born Cuban adults compared with NHW adults.19 Our conflicting results are likely due to differences in categorisation of sleep duration (eg, ≤6 hours and ≥9 hours versus 7–8 hours), adjustment sets and modelling approaches.19 25 38 Unlike our study, a multidimensional language acculturation measure was not associated with self-reported sleep problems among middle-aged Puerto Rican, Cuban and Dominican women in New Jersey.36

Several environmental and cultural factors that influence sleep behaviours and sleep health likely explain our findings. The negative acculturation effect, which has been observed as associated with sleep, posits that adoption of Western lifestyles leads to unhealthy behaviour practices and declines in health.39 Negative acculturation coupled with stress related to immigration status likely drive the unexpected disparity in sleep quality among foreign-born NHW adults compared with US-born NHW adults. Replication and further investigation of this possibility is warranted. The ‘Hispanic Paradox’ likely explains our observations among all Latino heritage groups except for Puerto Rican adults in which all remaining heritage groups tended to have better sleep than NHW counterparts, and Spanish language preference, a proxy measure for low language acculturation, appeared as a protective factor related to sleep health.14 16 The likely mechanism may be the greater ability to express emotions and reduce stress, which carries positive health impacts, when using the Spanish versus the English language.16 Further, variation in sleep by birthplace and Hispanic/Latino heritage is likely due to differentially experienced environments and unique cultural backgrounds that influence health and coping behaviours. Risk factors for poor sleep including, for instance, low socioeconomic housing environments, colour-related stigma and discrimination, social (including acculturation) stressors, structural barriers and health behaviours like smoking vary by Hispanic/Latino heritage groups with individuals of Puerto Rican descent usually more negatively affected compared with other heritage groups, which may manifest as differences in sleep health.13 40–46

There are several study limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design precluded our ability to make causal assumptions about birthplace as a predictor of sleep health. Second, all data were self-reported; however, misclassification of individuals into categories of race/ethnicity, sleep duration and quality, birthplace/nativity, language preference/acculturation and covariates is likely non-differential.47 Third, sleep disorders such as insomnia and sleep apnoea were not measured by the NHIS; however, these disorders may explain our results. Further study inclusive of sleep disorders is warranted. Fourth, our unidimensional, proxy measure of language acculturation did not capture the full breadth of acculturation,39 and data were not available for NHW participants; however, psychometric analyses have shown language explains most of the variance in acculturation scales.13 Nonetheless, future studies would benefit from using multidimensional measures of acculturation. Fifth, the observational nature of the study fosters potential for residual confounding. Sixth, small sample sizes upon stratification (eg, Dominican participants) and within-group heterogeneity (eg, birthplace for NHW and Central/South American adults) limited interpretability of results for certain heritage groups. Lastly, we tested for many associations and did not adjust for multiple comparisons due to the novelty of our study and our interest in identifying potential associations that may warrant further investigation.

Study strengths included the use of the most recently available data collected from a nationally representative and large sample that allowed for robust stratification by birthplace, race/ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino heritage and language preference/acculturation as well as adjustment for multiple confounders. Further, we used evidence-based categories of sleep duration, assessed multiple important sleep dimensions and directly estimated PRs.20 25 38 Our study extended prior literature as one of the few using national data to compare sleep health between US-born and foreign-born NHW adults as well as between foreign-born Hispanic/Latino heritage groups and their NHW counterparts.9 11

In conclusion, consideration of variation in birthplace/nativity, heritage, language and other cultural factors in future studies of racial/ethnic disparities in sleep health is important. Sleep disparities studies in the USA often consider NHW individuals as the reference group despite heterogeneity in birthplace, which may lead to inaccurate conclusions about racial/ethnic disparities in sleep health. Studies also often combine Hispanic/Latino heritage groups despite cultural heterogeneity. Future studies should consider within-group heterogeneity and disentangle cultural contributors in the social environment that influence sleep health and sleep health behaviours. Findings from such studies have the potential to inform culturally tailored public health interventions designed to improve sleep health among racial/ethnic subpopulations. Further, coupling culturally tailored interventions with structural changes related to environmental justice such as equitable social, economic and housing policies may further improve sleep health while reducing sleep health disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Center for Health Statistics for designing, conducting, and disseminating the survey and data files. They would like to thank all respondents who participated in the survey.

Footnotes

Presented at: This research was presented, in part, at the SLEEP 2020 Virtual Meeting, 27–30 August 2020.

Contributors: Study concept and design—CLJ and SAG. Acquisition of data—CLJ. Statistical analysis—JM, and WBJ II. Interpretation of data—SAG, EEM-M, JM, WBJ II, AN, EP-S and CLJ. Drafting of the manuscript—SAG, EEM-M. Critical revision of the manuscript—SAG, EEM-M, JM, WBJ II, AN, EP-S and CLJ. Administrative, technical and material support—CLJ. Obtaining funding and study supervision—CLJ. Final approval—SAG, EEM-M, JM, WBJ II, AN, EP-S and CLJ.

Funding: This work was funded by the Intramural Program at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, Z1AES103325) and the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are publicly available at https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Research approval is not required for the analysis of de-identified, publicly available data. This was an analysis of secondary data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey recruitment and data collection protocols were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Review Board. All participants gave informed consent.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Committee on Sleep Medicine Research . The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Colten HR, Altevogt BM, eds. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, et al. Prevalence of Healthy Sleep Duration among Adults--United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:137–41. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson DA, Jackson CL, Williams NJ, et al. Are sleep patterns influenced by race/ethnicity - a marker of relative advantage or disadvantage? Evidence to date. Nat Sci Sleep 2019;11:79–95. 10.2147/NSS.S169312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whinnery J, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep 2014;37:601–11. 10.5665/sleep.3508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson CL, Redline S, Emmons KM. Sleep as a potential fundamental contributor to disparities in cardiovascular health. Annu Rev Public Health 2015;36:417–40. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson CL. Determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in disordered sleep and obesity. Sleep Health 2017;3:401–15. 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson CL, Walker JR, Brown MK, et al. A workshop report on the causes and consequences of sleep health disparities. Sleep 2020;43. 10.1093/sleep/zsaa037. [Epub ahead of print: 12 08 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berge JM, Fertig A, Tate A, et al. Who is meeting the healthy people 2020 objectives?: comparisons between racially/ethnically diverse and immigrant children and adults. Fam Syst Health 2018;36:451–70. 10.1037/fsh0000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham TJ, Wheaton AG, Ford ES, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in self-reported short sleep duration among US-born and foreign-born adults. Ethn Health 2016;21:628–38. 10.1080/13557858.2016.1179724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hale L, Troxel WM, Kravitz HM, et al. Acculturation and sleep among a multiethnic sample of women: the study of women's health across the nation (Swan). Sleep 2014;37:309–17. 10.5665/sleep.3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newsome V, Seixas A, Iwelunmor J, et al. Place of birth and sleep duration: analysis of the National health interview survey (NHIS). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14. 10.3390/ijerph14070738. [Epub ahead of print: 07 07 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Principles of Community Engagement . Clinical and translational science awards (CTSA) community engagement key function Committee Task force on the principles of community engagement. centers for disease control and prevention and the agency for toxic substances and disease registry. Atlanta, GA: National Institutes of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, et al. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health 2005;26:367–97. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandner MA, Khader WS, Warlick CD, et al. Acculturation and sleep: implications for sleep and health disparities. Sleep 2019;42. 10.1093/sleep/zsz059. [Epub ahead of print: 01 03 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: a systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:983–91. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llabre MM. Insight into the Hispanic paradox: the language hypothesis. Perspect Psychol Sci 2021:1745691620968765. 10.1177/1745691620968765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hale L, Rivero-Fuentes E. Negative acculturation in sleep duration among Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13:402–7. 10.1007/s10903-009-9284-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Strohl K, et al. An exploration of differences in sleep characteristics between Mexico-born us immigrants and other Americans to address the Hispanic paradox. Sleep 2011;34:1021–31. 10.5665/SLEEP.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García C, Sheehan CM, Flores-Gonzalez N, et al. Sleep patterns among US Latinos by Nativity and country of origin: results from the National health interview survey. Ethn Dis 2020;30:119–28. 10.18865/ed.30.1.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? does it matter? Sleep 2014;37:9–17. 10.5665/sleep.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCfH S. Survey description, National health interview survey, 2015. Maryland: Hyattsville, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blewett LA, Rivera-Drew JA, Griffin R. IPUMS health surveys: National health interview survey, version 6.2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.OMB . Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. A Notice by the Management and Budget Office on 09/30/2016. In: OoMa B, ed. The daily Journal of the United States government, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Consensus Conference Panel, Watson NF, Badr MS, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American Academy of sleep medicine and sleep research Society. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:591–2. 10.5665/sleep.4716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National sleep Foundation's updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health 2015;1:233–43. 10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:1973–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the who world mental health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2010;19 Suppl 1:4–22. 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American heart association's strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121:586–613. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson CL, Hu FB, Redline S, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in short sleep duration by occupation: the contribution of immigrant status. Soc Sci Med 2014;118:71–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson CL, Redline S, Emmons KM. Sleep as a Potential Fundamental Contributor to Disparities in Cardiovascular Health. In: Fielding JE, ed. Annual Review of Public Health. 36. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews, 2015: 417–40. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein SJ, Gaston SA, McGrath JA, et al. Sleep Health and Serious Psychological Distress: A Nationally Representative Study of the United States among White, Black, and Hispanic/Latinx Adults]]>. Nat Sci Sleep 2020;12:1091–104. 10.2147/NSS.S268087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, et al. Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep complaints. Sleep Med 2010;11:470–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mogavero MP, DelRosso LM, Fanfulla F, et al. Sleep disorders and cancer: state of the art and future perspectives. Sleep Med Rev 2021;56:101409. 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manber R, Steidtmann D, Chambers AS, et al. Factors associated with clinically significant insomnia among pregnant low-income Latinas. J Womens Health 2013;22:694–701. 10.1089/jwh.2012.4039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green R, Santoro NF, McGinn AP, et al. The relationship between psychosocial status, acculturation and country of origin in mid-life Hispanic women: data from the study of women's health across the nation (Swan). Climacteric 2010;13:534–43. 10.3109/13697131003592713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heilemann MV, Choudhury SM, Kury FS, et al. Factors associated with sleep disturbance in women of Mexican descent. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:2256–66. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05918.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barros AJD, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21. 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Miller EE, Prather AA, Robinson WR, et al. US acculturation and poor sleep among an intergenerational cohort of adult Latinos in Sacramento, California. Sleep 2019;42:zsy246. 10.1093/sleep/zsy246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuevas AG, Dawson BA, Williams DR. Race and skin color in Latino health: an analytic review. Am J Public Health 2016;106:2131–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia JA, Sanchez GR, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. Race as lived experience: the impact of multi-dimensional measures of Race/Ethnicity on the self-reported health status of Latinos. Du Bois Rev 2015;12:349–73. 10.1017/S1742058X15000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alcántara C, Gallo LC, Wen J, et al. Employment status and the association of sociocultural stress with sleep in the Hispanic community health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Sleep 2019;42. 10.1093/sleep/zsz002. [Epub ahead of print: 01 04 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dominguez K, Penman-Aguilar A, Chang M-H, et al. Vital signs: leading causes of death, prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and use of health services among Hispanics in the United States - 2009-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:469–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loredo JS, Soler X, Bardwell W, et al. Sleep health in U.S. Hispanic population. Sleep 2010;33:962–7. 10.1093/sleep/33.7.962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alcántara C, Patel SR, Carnethon M, et al. Stress and sleep: results from the Hispanic community health Study/Study of Latinos sociocultural ancillary study. SSM Popul Health 2017;3:713–21. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaston SA, Nguyen-Rodriguez S, Aiello AE, et al. Hispanic/Latino heritage group disparities in sleep and the sleep-cardiovascular health relationship by housing tenure status in the United States. Sleep Health 2020;6:451–62. 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson CL, Patel SR, Jackson WB, et al. Agreement between self-reported and objectively measured sleep duration among white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese adults in the United States: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Sleep 2018;41. 10.1093/sleep/zsy057. [Epub ahead of print: 01 06 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047834supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are publicly available at https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/.