Abstract

Background

Oncogenic mutations in PIK3CA are prevalent in diverse cancers and can be targeted with inhibitors of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) pathway. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) provides a minimally invasive approach to detect clinically actionable PIK3CA mutations.

Patients and methods

We analyzed PIK3CA hotspot mutation frequency by droplet digital PCR (QX 200; BioRad) using 16 ng of unamplified plasma-derived cell-free DNA from 68 patients with advanced solid tumors (breast cancer, n = 41; colorectal cancer, n = 13; other tumor types, n = 14). Results quantified as variant allele frequencies (VAFs) were compared with previous testing of archival tumor tissue and with patient outcomes.

Results

Of 68 patients, 58 (85%) had PIK3CA mutations in tumor tissue and 43 (74%) PIK3CA mutations in ctDNA with an overall concordance of 72% (49/68, κ = 0.38). In a subset analysis, which excluded samples from 26 patients known not to have disease progression at the time of sample collection, we found an overall concordance of 91% (38/42; κ = 0.74). PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA VAF of ≤8.5% (5% trimmed mean) showed a longer median survival compared with patients with a higher VAF (15.9 versus 9.4 months; 95% confidence interval 6.7-17.1 months; P = 0.014). Longitudinal analysis of ctDNA in 18 patients with serial plasma collections (range 2-22 time points, median 5) showed that those with a decrease in PIK3CA VAF had a longer time to treatment failure (TTF) compared with patients with an increase or no change (10.7 versus 2.6 months; P = 0.048).

Conclusions

Detection of PIK3CA mutations in ctDNA is concordant with testing of archival tumor tissue. Low quantity of PIK3CA-mutant ctDNA is associated with longer survival and a decrease in PIK3CA-mutant ctDNA on therapy is associated with longer TTF.

Key words: PIK3CA, circulating tumor DNA, droplet digital PCR, cancer

Highlights

-

•

Testing for PIK3CA mutations in ctDNA is concordant with testing of tumor tissue.

-

•

High PIK3CA-mutant abundance in ctDNA was associated with shorter survival.

-

•

Increasing PIK3CA-mutant abundance in serial blood samples was associated with shorter TTF.

-

•

Longitudinal monitoring of PIK3CA-mutant ctDNA tracked with cancer clinical course.

Introduction

Aberrant activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) pathway can lead to decreased apoptosis and increased cellular proliferation, contributing to cancer progression and therapeutic resistance.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway can occur through a variety of mechanisms, including mutations in the p110α (PIK3CA) catalytic subunit of PI3K.6,7 Somatic oncogenic mutations in PIK3CA commonly occur across varying cancers including gynecologic (uterine, cervical, ovarian, vaginal), breast, colorectal, and non-small-cell lung cancers.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Common ‘hot spots’ of PIK3CA somatic mutations that lead to gain of function and activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway occur in exon 9 (helical domain, p.E542K and p.E545K) and in exon 20 (kinase domain, p.H1047R or p.H1047L).8,12 PIK3CA mutations have been identified as primary oncogenic drivers as well as emerging alterations associated with therapeutic resistance.13, 14, 15

PIK3CA mutations in cancer can be associated with a favorable response to treatment with PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibitors.10,11,13,16, 17, 18 Direct targeting of PIK3CA with alpelisib in patients with PIK3CA-mutated advanced cancers can have anticancer efficacy, and alpelisib in combination with the selective estrogen receptor degrader, fulvestrant, has been approved for the treatment of patients with hormone receptor-positive, PIK3CA-mutated [in tumor and/or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)] metastatic breast cancer who were previously treated with hormone therapy.19 Testing of ctDNA provides a minimally invasive alternative to molecular testing of tumor tissue; however, concordance and sensitivity can differ among technologies and tumor types.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 In addition, quantity and dynamic changes in ctDNA can be associated with patient outcomes.24, 25, 26, 27 We hypothesized that PIK3CA mutations can be detected in a small volume of plasma ctDNA from patients with progressing advanced cancers by droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) and that quantity and dynamic changes in ctDNA assessed by variant allele frequency (VAF) of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA can correspond with patients' outcomes.

Methods

Patients

Patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors and available PIK3CA mutation status from tumor tissue receiving their care at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who were considered for experimental therapies between November 2010 and December 2017, were enrolled in this study in accordance with MD Anderson’s Institutional Review Board guidelines. Patients were offered to have an optional blood collection prior to and sequentially during their experimental cancer treatment. Patients signed a written informed consent, and this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Tumor samples were collected during standard-of-care therapeutic and/or diagnostic procedures and genomic testing was performed on archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory for identification of actionable alterations for personalized cancer therapy. The tumor genomic testing was done by PCR or next-generation sequencing (NGS) on approved targeted gene panels. Clinical characteristics were collected from electronic medical records and prospectively maintained institutional databases.

Plasma-derived circulating tumor DNA analysis

Blood samples were collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes prior to experimental cancer therapy and during therapy whenever possible. Plasma was obtained within 2 h of blood collection by double centrifugation of blood samples. Cell-free DNA was isolated and extracted using the QIAamp circulating nucleic acid kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Using a multiplex ddPCR device (QX 200; BioRad, Hercules, CA), 16 ng of unamplified ctDNA was tested for PIK3CA mutations (p.H1047R, p.H1047L, p.E542K, and p.E545K) versus wild-type alleles, according to the manufacturer's instructions. For patients with mutations present in the tumor analysis, but not in the plasma ctDNA, re-testing with increased amount of ctDNA (21-247 ng) was performed. The lower limit of detection is <0.1% VAF per single well for the mutation-specific assays. Patients with simultaneous KRAS mutations in tumor tissue were also tested whenever feasible for the presence of corresponding KRAS mutation in ctDNA as described previously.23

Treatment and evaluation

Whenever possible, patients with confirmed PIK3CA mutations by FFPE tumor tissue analysis were enrolled on genome-matched clinical trials involving inhibitors of the PI3K/ATK/mTOR pathway. For these patients, treatment was administered in accordance with IRB-approved protocols, and patients received therapy until clinical or radiological disease progression per RECIST version 1.128 or until the development of excessive intolerable treatment-related toxicity. We evaluated the type of targeted therapy that they received and the best overall response on treatment.

Statistical analysis

Concordance between mutation analysis of tumor tissue and ctDNA was calculated using the kappa coefficient.29,30 Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the first blood collection for ctDNA analysis to the date of death or last follow-up. Time to treatment failure (TTF) was defined as the time from the date of systemic experimental therapy initiation to the date the patient was taken off the treatment or last follow-up. Last follow-up or date of death was determined based on the electronic medical records. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate OS and TTF, and a log-rank test was used to compare OS and TTF among patient subgroups. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess the prognostic impact of PIK3CA VAF, in addition to other clinical variables including cancer type, blood serum albumin levels, and the presence of simultaneous mutations in the KRAS oncogene.

All tests were two-sided, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 23 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) or Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) software program.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 68 patients with advanced cancers were analyzed in this study, the majority of which were female (81%), with a median age of 57 years (range 32-82 years). The most common cancer diagnosis among these patients was breast cancer (n = 41, 60%), followed by colorectal cancer (n = 13, 19%), non-small-cell lung cancer (n = 3, 4%), ovarian cancer (n = 3, 4%), salivary gland cancer (n = 2, 3%), and other cancers (n = 6, 9%). There was a median of 27 months (0-189 months) between the archival tumor tissue collection and plasma collections. Molecular testing of archival tumor tissue was carried out using either PCR (n = 12, 18%) or NGS (n = 56, 82%) as a part of routine clinical care. Based on tumor tissue molecular testing, 10 patients (15%) had PIK3CA wild-type tumors, while the remaining patients had the following PIK3CA mutations: E542K (n = 10, 15%), E545K (n = 17, 23%), H1047L (n = 5, 7%), and H1047R (n = 29, 40%). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients (N = 68) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis - range, years | 32-82 |

| Median | 57 |

| Mean ± standard deviation | 57 ± 12 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 55 (81) |

| Male | 13 (19) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 11 (16) |

| 1 | 57 (84) |

| ≥2 | 0 (0) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | |

| Breast cancer | 41 (60) |

| Colorectal cancer | 13 (19) |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | 3 (4) |

| Ovarian cancer | 3 (4) |

| Salivary gland cancer | 2 (3) |

| Appendiceal cancer | 1 (1) |

| Cervical cancer | 1 (1) |

| Endometrial cancer | 1 (1) |

| Head and neck squamous cell cancer | 1 (1) |

| Neuroendocrine cancer | 1 (1) |

| Thyroid cancer | 1 (1) |

| Type of tumor tissue testing, n (%) | |

| Polymerase chain reaction | 12 (18) |

| Next-generation sequencing | 56 (82) |

| PIK3CA mutation status in tumor, n (%) | |

| E542K | 10 (15) |

| E545K | 17 (23) |

| H1047L | 5 (7) |

| H1047R | 29 (40) |

| Wild-type | 10 (15) |

| Time between tumor tissue and plasma collection, months (range) | 27 (0-189) |

PIK3CA mutation concordance between circulating tumor DNA and tumor tissue

Among the 68 patients included in this study, 10 (15%) had wild-type PIK3CA and 58 (85%) had PIK3CA mutations in the tumor tissue. Analysis of plasma ctDNA samples collected before starting therapy detected PIK3CA mutations in 39 samples with known mutations in the tumor tissue, resulting in observed agreement rate of 72% [49/68; κ = 0.38, standard error (SE) = 0.09; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.19-0.56], sensitivity of 67% (39/68; 95% CI 0.54-0.79), and specificity of 100% (10/10; 95% CI 0.69-1; Table 2). We hypothesized that using a higher input of DNA can improve the sensitivity of ddPCR. Of 19 false-negative plasma samples, we re-tested nine samples with available residual material using a higher input of DNA (range 22-227 ng) and detected PIK3CA mutations in four additional samples, improving overall agreement to 78% (53/68; κ = 0.46, SE = 0.10; 95% CI 0.25-0.66) and sensitivity to 74% (43/68; 95% CI 0.61-0.85). Finally, we evaluated concordance by excluding samples from 26 patients known not to have disease progression at the time of sample collection to account for samples that might have undetectable levels of plasma ctDNA due as result of therapy, and found an overall agreement of 91% (38/42; κ = 0.74, SE = 0.12; 95% CI 0.51-0.97) and sensitivity of 88% (30/42; 95% CI 0.73-0.97; Table 2).

Table 2.

Concordance between PIK3CA mutation testing in the tumor and ctDNA

| PIK3CA mutation in both FFPE and ctDNA | PIK3CA wild-type in both FFPE and ctDNA | PIK3CA mutation in FFPE only | PIK3CA mutation in ctDNA only | Observed agreements | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 ng DNA input | 39 | 10 | 19 | 0 | 49 (72%); κ = 0.38, SE = 0.09; 95% CI 0.19-0.56 |

67% (0.54-0.79) | 100% (0.69-1) |

| Up to 227 ng DNA input (9 samples retested) | 43 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 53 (78%); κ = 0.46, SE = 0.10; 95% CI 0.25-0.66 |

74% (0.61-0.85) | 100% (0.69-1) |

| Up to 227 ng DNA (excluding patients without disease progression at time of sample collection) | 30 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 38 (91%); κ = 0.74, SE = 0.12; 95% CI 0.51-0.97 | 88% (0.73-0.97) | 100% (0.63-1) |

CI, confidence interval; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; SE, standard error.

PIK3CA mutations in circulating tumor DNA and survival

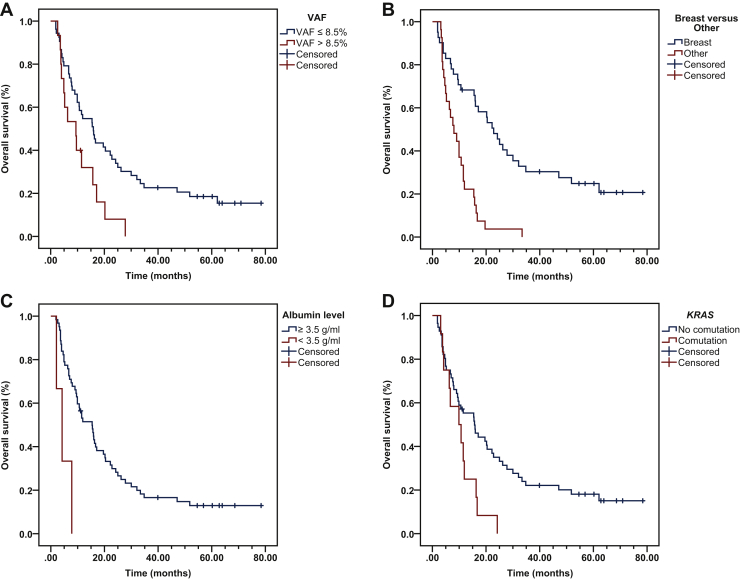

We next analyzed the association between the quantity (determined by VAF) of PIK3CA-mutant ctDNA and patients’ OS. To eliminate potential bias from samples with no detectable PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA, we divided patients into two groups using a 5% trimmed mean instead of the median, which was 8.5% VAF. Patients with VAF PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA ≤8.5% showed longer median OS (15.9 months; 95% CI 10.6-21.2 months) compared with patients with VAF >8.5% (9.4 months; 95% CI 3.8-15.0 months; P = 0.014; Figure 1A). In addition, we analyzed the association between OS and additional clinical factors such as cancer type, serum albumin levels, and the presence of simultaneous ctDNA KRAS mutations and found that patients with breast cancer had longer OS (22.8 months; 95% CI 16.9-28.7 months) compared with patients with other cancers (8.0 months; 95% CI 4.1-11.9 months; P = 4 × 10−6; Figure 1B); patients with blood serum albumin levels ≥3.5 g/ml had longer OS (15.4 months; 95% CI 9.8-21.0 months) compared with patients with albumin levels <3.5 g/ml (4.2 months; 95% CI 0.8-7.6 months; P = 0.003; Figure 1C); and finally patients with simultaneous ctDNA KRAS mutations had shorter OS (9.9 months; 95% CI 3.1-16.7 months) compared with patients with ctDNA wild-type KRAS (15.7 months; 95% CI 9.0-22.4 months; P = 0.022; Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival of PIK3CA variant allele frequency (VAF) and other clinical variables.

Kaplan–Meier survival calculations were performed to assess the impact of clinical variables on patient overall survival (OS). (A) Patients with a PIK3CA VAF ≤8.5% showed significantly longer median OS compared with patients with a VAF >8.5% (15.9 months compared with 9.4; P = 0.014). (B) Patients diagnosed with breast cancer had longer OS compared with patients with other cancers (22.8 months compared with 8.0; P = 4 × 10−6). (C) Patients with serum albumin levels ≥3.5 g/ml had longer OS compared with patients with other cancers (15.4 months compared with 4.2; P = 0.003). (D) Patients with comutations in the KRAS oncogene had shorter OS compared with patients lacking comutations in KRAS (9.9 months compared with 15.7; P = 0.022).

A covariate Cox proportional hazards regression model, which included quantity of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA (VAF ≤8.5% versus >8.5%), tumor type (breast versus other cancers), albumin levels (≥3.5 g/ml versus <3.5 g/ml), and simultaneous KRAS mutations in ctDNA (absent versus present), showed that PIK3CA-mutated VAF ≤8.5% [hazard ratio (HR) 0.394; 95% CI 0.203-0.766; P = 0.006], breast cancer (HR 0.276; 95% CI 0.144-0.529; P = 1 × 10−4), and blood serum albumin levels ≥3.5 g/ml (HR 0.129; 95% CI 0.035-0.467; P = 0.002) were independent prognostic indicators for longer OS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multicovariate Cox regression

| Clinical variable | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA variant allele frequency (≤8.5% versus >8.5%) | 0.394 | 0.203-0.766 | 0.006 |

| Cancer diagnosis (breast versus other) | 0.276 | 0.144-0.529 | 0.0001 |

| Serum albumin (≥3.5 g/ml versus <3.5 g/ml) | 0.129 | 0.035-0.467 | 0.002 |

| KRAS comutations (no comutation versus comutation) | 0.851 | 0.393-1.843 | 0.682 |

Longitudinal assessment of PIK3CA mutations in circulating tumor DNA

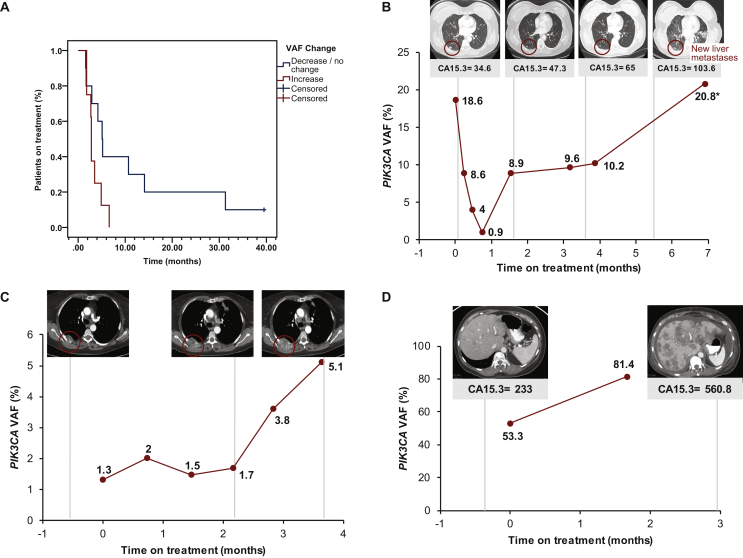

Serial plasma ctDNA samples of two or more collections (median 5; range 2-22) before and during administration of systemic therapy were available for 18 patients (2 collections, n = 6; 3 collections, n = 3; 4 collections, n = 1; 6 collections, n = 2; 7 collections, n = 1; 8 collections, n = 3; 9 collections, n = 1; and 22 collections, n = 1). Among these 18 patients, 10 (56%) showed either a decrease or no change in quantity of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA VAF at the time of the first follow-up, while the remaining eight (44%) showed an increase. Patients with a decrease or no change in PIK3CA VAF had longer median TTF compared with patients showing an increase (155 days versus 84 days; HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.14-1.21; P = 0.048; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal changes in PIK3CA variant allele frequency (VAF) tracking in patients with solid tumors.

(A) Patients with serial plasma collections showing a decrease or no change in PIK3CA VAF had a significantly longer median time to treatment failure compared with patients having an increase in VAF (155 days versus 84 days; hazard ratio 0.42; 95% confidence interval 0.14-1.21; P = 0.048). (B) A 62-year-old female with metaplastic breast cancer with PIK3CA E545K mutation had a total of eight plasma samples collected starting at baseline (cycle 1 day 1) and ending 1 month after treatment with liposomal doxorubicin with bevacizumab and everolimus, accompanied by four computed tomography imaging scans (vertical dotted lines indicate scan dates). Red circle outlines the metastatic lesion in the right lung (new liver metastases are not imaged) and tumor marker CA15-3 was also evaluated [units per milliliter (U/ml); normal range 0-25 U/ml]. (C) A 66-year-old female with endometrial cancer with PIK3CA H1047L mutation and additional mutations in PTEN T319∗, KRAS G12V, and MSI-H had a total of six plasma samples collected starting at baseline and ending at cycle 5 day 1 of PD-1 antibody treatment, accompanied by three computed tomography imaging scans (vertical dotted lines indicate scan dates). Red circle outlines the metastatic lesion in the right chest wall. (D) A 62-year-old female with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer with PIK3CAE542K mutation had a total of two plasma samples collected at baseline and cycle 2 day 1, accompanied by two computed tomography imaging scans (vertical dotted lines indicate scan dates).

In many patients with serial plasma collections, the dynamic changes in VAF of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA dynamically tracked with cancer clinical course. For example, in a 62-year-old female with metastatic metaplastic breast cancer with a PIK3CAE545K mutation treated with a combination of liposomal doxorubicin, bevacizumab, and everolimus, we initially observed a decrease in VAF of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA followed by a steady rise from cycle 3 day 1 until radiological progression on computed tomography (CT) because of new liver metastases, which resulted in treatment discontinuation after six cycles (Figure 2B). Another example is a 66-year-old female patient with endometrial cancer with PIK3CAH1047L, PTENT319∗, and KRASG12V mutations and with microsatellite-instability high phenotype with prior treatments with AKT and mTOR inhibitors. On therapy with experimental PD1 antibody initially, VAF of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA increased by cycle 2 day 1, then mildly decreased by cycle 3 day 1 when CT showed overall stable disease; however, there was a considerable increase by cycle 4 day 1 and even more so after cycle 4, which ultimately corresponded with disease progression on CT imaging (Figure 2C). Finally, a 62-year-old female patient with metastatic breast cancer with PIK3CAE542K mutation with prior treatments including standard hormone therapy and chemotherapy. On therapy with experimental PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, VAF of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA increased by cycle 2 day 1 and by cycle 3 day 1 CT showed significant disease progression and increase in CA 15-3 tumor marker levels (Figure 2D).

Discussion

Blood-based detection of PIK3CA mutations is of increasing importance as PIK3CA mutation status can change over time due to clonal evolution and emergence of therapeutic resistance.31 In addition, patients with hormone receptor-dependent metastatic breast cancer and PIK3CA mutation in ctDNA had longer progression-free survival when the PI3K inhibitor buparlisib was added to hormone therapy with fulvestrant.32 Our study demonstrated that detection of PIK3CA mutations in blood-derived ctDNA by ddPCR in patients with advanced cancers referred for experimental therapies is feasible and concordant with standard of care testing of tumor tissue, especially in blood collected from patients experiencing disease progression (increase in concordance from 72% to 91% and sensitivity from 67% to 88%). In addition, our method demonstrated high specificity with no false-positive results. We also demonstrated that sensitivity increases with an increase in DNA input, which in our study resulted in conversion of 44% of initially falsely negative ctDNA samples. Our results are similar to previously presented studies.23,33 For instance, Higgins et al.33 reported concordance of 72.5% for plasma PIK3CA mutation detection with BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification, magnetics) PCR compared with discordantly tested archival FFPE tissue.

Our study also demonstrated that patients with high VAF of mutant ctDNA in baseline samples had shorter OS compared with patients with low VAF, and this observation has been confirmed on the multicovariate analysis (P = 0.006). This agrees with previously published data. For instance, our group and others demonstrated shorter OS in patients with high VAF of mutant ctDNA for multiple oncogenic mutations detected by digital PCR or NGS technologies.25,26,34,35 However, it remains unclear if high VAF simply represents increased tumor burden or rather different and more aggressive biology.24

We also noticed that patients with an increase in ctDNA quantity defined by delta in VAF during therapy had shorter TTF than patients with a decrease or no change (P = 0.048). This is not unexpected. Although the ctDNA quantity can fluctuate during therapy, there is a mounting evidence that negative delta in ctDNA quantity during therapy is associated with better treatment outcomes. For instance, our group and others reported similar observations for patients with BRAF-mutated cancers, KRAS-mutated cancers, and other cancers treated with diverse systemic cancer therapies.24,25,27,36,37 More recently, Pascual et al.38 reported that changes in quantity of PIK3CA-mutated ctDNA in patients with PIK3CA-mutated tumors treated with the PI3K inhibitor taselisib-based therapy are associated with treatment outcomes, and specifically patients with high on-treatment ctDNA had shorter progression-free survival (P = 0.04). We also observed that the dynamic changes in VAF of PIK3CA-muated cfDNA correlated with clinical course and were perhaps sometimes even more suggestive of clinical outcomes than standard imaging. Systematic studies to develop ctDNA-guided approaches to assess response to systemic therapies are currently underway by our group and others.

Our study also has several limitations. First, the study was retrospective and included a relatively small number of patients with diverse cancer types. Therefore, our observations suggesting clinical utility for assessment of OS and TTF need to be validated in prospective clinical studies with a more homogenous patient population and treatment selection. Second, we tested only for four most frequent PIK3CA mutations in exons 9 and 20. Third, we used archival tumor tissue, which was not collected at the same time as plasma samples and also 26 patients did not have disease progression at the time of plasma sample collection, which could have negatively affected our concordance rates and sensitivity.

In summary, despite the aforementioned limitations, our data suggest that commonly occurring mutations in PIK3CA can be detected by ddPCR in plasma ctDNA with high sensitivity and specificity in patients with progressing cancer. Low amount of PIK3CA-mutant cfDNA is associated with longer OS. Changes in PIK3CA VAF could be an early surrogate biomarker for TTF on systemic treatments.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Precision Oncology Decision Support Core RP150535, Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Institute for Personalized Cancer Therapy, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant UL1 TR000371, National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016672) and Clinical and Translational Science Award (1UL1 TR003167, Andre Sabin Family Fellowship Award, and the NCI K12 Paul Calabresi Award CA088084.

Disclosure

FJ has research support from Novartis, Genentech, BioMed Valley Discoveries, Astellas, Agios, Plexxikon, Deciphera, PIQUR, Symphogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Asana, and Upsher-Smith Laboratories; is or has been on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Guardant Health, IFM Therapeutics, Synlogic, and Deciphera; is a paid consultant for Cardiff Oncology and ImmunoMet; and has ownership interests in Cardiff Oncology. MF reports grants and personal consulting fees through 06/04/18 from Seattle Genetics and salary and stocks from 10/01/18 following the start of her employment with Seattle Genetics; grants and personal fees from Takeda, Celgene, BMS, and Merck through 06/04/18; grants from ADC Therapeutics, Molecular Templates, MedImmune, Gilead, and Genentech through 06/04/18; and personal fees from Bayer and Spectrum through 06/04/18. VS has research funding/grant support for clinical trials (to institution) from Novartis, Bayer, Berghealth, Incyte, Fujifilm, PharmaMar, D3, Pfizer, MultiVir, Amgen, AbbVie, Alfa-sigma, Agensys, Boston Biomedical, Idera Pharma, Inhibrx, Exelixis, Blueprint Medicines, Loxo Oncology, MedImmune, Altum, Dragonfly Therapeutics, Takeda and, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, NCI-CTEP, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Turning point therapeutics, and Boston Pharmaceuticals; travel funding from Novartis, PharmaMar, ASCO, ESMO, Helsinn, Incyte; and serves on the advisory board of Helsinn, LOXO Oncology/ Eli Lilly, R-Pharma US, INCYTE, QED pharma, Astra-Zeneca/Medimmune, Novartis, Signant Health. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Janku F., Yap T.A., Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:273–291. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fruman D.A., Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrd4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalhoub N., Baker S.J. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vivanco I., Sawyers C.L. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu P., Cheng H., Roberts T.M., Zhao J.J. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuels Y., Waldman T. Oncogenic mutations of PIK3CA in human cancers. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;347:21–41. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan T.L., Cantley L.C. PI3K pathway alterations in cancer: variations on a theme. Oncogene. 2008;27:5497–5510. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuels Y., Wang Z., Bardelli A. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karakas B., Bachman K.E., Park B.H. Mutation of the PIK3CA oncogene in human cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:455–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janku F., Tsimberidou A.M., Garrido-Laguna I. PIK3CA mutations in patients with advanced cancers treated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:558–565. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janku F., Hong D.S., Fu S. Assessing PIK3CA and PTEN in early-phase trials with PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors. Cell Rep. 2014;6:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zehir A., Benayed R., Shah R.H. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janku F., Wheler J.J., Westin S.N. PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in patients with breast and gynecologic malignancies harboring PIK3CA mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:777–782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataoka Y., Mukohara T., Shimada H., Saijo N., Hirai M., Minami H. Association between gain-of-function mutations in PIK3CA and resistance to HER2-targeted agents in HER2-amplified breast cancer cell lines. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:255–262. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelman J.A., Chen L., Tan X. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janku F., Wheler J.J., Naing A. PIK3CA mutation H1047R is associated with response to PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway inhibitors in early-phase clinical trials. Cancer Res. 2013;73:276–284. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juric D., Rodon J., Tabernero J. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase alpha-selective inhibition with alpelisib (BYL719) in PIK3CA-altered solid tumors: results from the first-in-human study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1291–1299. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juric D., Janku F., Rodon J. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-altered and PIK3CA-wild-type estrogen receptor-positive advanced breast cancer: a phase 1b clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:e184475. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andre F., Ciruelos E., Rubovszky G. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1929–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polivka J., Jr., Pesta M., Janku F. Testing for oncogenic molecular aberrations in cell-free DNA-based liquid biopsies in the clinic: are we there yet? Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:1631–1644. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1110021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bettegowda C., Sausen M., Leary R.J. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra224. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grasselli J., Elez E., Caratù G. Concordance of blood- and tumor-based detection of RAS mutations to guide anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1294–1301. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janku F., Huang H.J., Fujii T. Multiplex KRASG12/G13 mutation testing of unamplified cell-free DNA from the plasma of patients with advanced cancers using droplet digital polymerase chain reaction. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:642–650. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janku F., Zhang S., Waters J. Development and validation of an ultradeep next-generation sequencing assay for testing of plasma cell-free DNA from patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5648–5656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janku F., Huang H.J., Claes B. BRAF mutation testing in cell-free DNA from the plasma of patients with advanced cancers using a rapid, automated molecular diagnostics system. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1397–1404. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janku F., Angenendt P., Tsimberidou A.M. Actionable mutations in plasma cell-free DNA in patients with advanced cancers referred for experimental targeted therapies. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12809–12821. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii T., Barzi A., Sartore-Bianchi A. Mutation-enrichment next-generation sequencing for quantitative detection of KRAS mutations in urine cell-free DNA from patients with advanced cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3657–3666. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHugh M.L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22:276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viera A.J., Garrett J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37:360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sequist L.V., Waltman B.A., Dias-Santagata D. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. 75ra26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baselga J., Im S.A., Iwata H. Buparlisib plus fulvestrant versus placebo plus fulvestrant in postmenopausal, hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (BELLE-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:904–916. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30376-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins M.J., Jelovac D., Barnathan E. Detection of tumor PIK3CA status in metastatic breast cancer using peripheral blood. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3462–3469. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pairawan S., Hess K.R., Janku F. Cell-free circulating tumor DNA variant allele frequency associates with survival in metastatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1924–1931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwaederle M., Husain H., Fanta P.T. Use of liquid biopsies in clinical oncology: pilot experience in 168 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5497–5505. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Q., Luo J., Wu S. Prognostic and predictive impact of circulating tumor DNA in patients with advanced cancers treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1842–1853. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razavi P., Dickler M.N., Shah P.D. Alterations in PTEN and ESR1 promote clinical resistance to alpelisib plus aromatase inhibitors. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:382–393. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pascual J., Lim J.S.J., Macpherson I.R. Triplet therapy with palbociclib, taselisib, and fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutant breast cancer and doublet palbociclib and taselisib in pathway-mutant solid cancers. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:92–107. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]