Abstract

目的

探讨脂肪干细胞(adipose-derived stem cells,ADSCs)来源外泌体对周围神经损伤后再生的影响,为周围神经损伤寻找新的治疗方法。

方法

将 36 只成年 SD 大鼠(雌雄不限,体质量 220~240 g)随机分成 3 组,每组 12 只。A 组为正常对照组,B 组为坐骨神经挤压损伤组,C 组为 ADSCs 来源外泌体治疗坐骨神经挤压损伤组。A 组仅暴露坐骨神经后直接缝合切口,B、C 组制备坐骨神经挤压损伤模型;术后次日开始,A、B 组于大鼠尾静脉注射 PBS 液 200 μL,C 组注射含 100 μg ADSCs 来源外泌体的 PBS 液 200 μL,每周注射 1 次,连续 12 周。注射结束 1 周后处死大鼠,取损伤处坐骨神经,分别行大体观察、HE 染色观察神经束情况、TUNEL 检测坐骨神经雪旺细胞(Schwann cells,SCs)凋亡情况,透射电镜观察坐骨神经超微结构和 SCs 自噬情况。

结果

大体观察示 A 组患肢无明显异常,B、C 组患肢瘫痪、肌肉萎缩,但 C 组瘫痪及肌肉萎缩程度轻于 B 组。HE 染色示,A 组神经束膜形态规则;B 组神经束形态破坏、束膜不规则,有较多无细胞结构和组织碎片;C 组神经束膜较完整,明显优于 B 组。TUNEL 检测示,B、C 组 SCs 凋亡细胞数显著多于 A 组,B 组显著多于 C 组,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.01)。透射电镜观察示,B、C 组 SCs 自噬体较 A 组明显增加,但 C 组少于 B 组。

结论

ADSCs 来源外泌体对周围神经损伤后再生有一定促进作用,其机制可能与减少 SCs 凋亡、抑制其自噬、减轻神经瓦勒变性有关。

Keywords: 外泌体, 脂肪干细胞, 周围神经损伤, 神经再生, 大鼠

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effects of exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) on peripheral nerve regeneration, and to find a new treatment for peripheral nerve injury.

Methods

Thirty-six adult Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (male or female, weighing 220-240 g) were randomly divided into 3 groups (n=12). Group A was the control group; group B was sciatic nerve injury group; group C was sciatic nerve injury combined with exosomes from ADSCs treatment group. The sciatic nerve was only exposed without injury in group A, and the sciatic nerve crush injury model was prepared in groups B and C. The SD rats in groups A and B were injected with PBS solution of 200 μL via tail veins; the SD rats in group C were injected with pure PBS solution of 200 μL containing 100 μg exosomes from ADSCs, once a week and injected for 12 weeks. At 1 week after the end of the injection, the rats were killed and the sciatic nerves were taken at the part of injury. The sciatic nerve fiber bundles were observed by HE staining; the SCs apoptosis of the sciatic nerve tissue were detected by TUNEL staining; the ultrastructure and SCs autophagy of the sciatic nerve were observed by transmission electron microscope.

Results

Gross observation showed that there was no obvious abnormality in the injured limbs of group A, but there were the injured limbs paralysis and muscle atrophy in groups B and C, and the degree of paralysis and muscle atrophy in group C were lighter than those in group B. HE staining showed that the perineurium of group A was regular; the perineurium of group B was irregular, and there were a lot of cell-free structures and tissue fragments in group B; the perineurium of group C was more complete, and significantly well than that of group B. TUNEL staining showed that the SCs apoptosis was significantly increased in groups B and C than in group A, in group B than in group C (P<0.01). Transmission electron microscope observation showed that the SCs autophagosomes in groups B and C were significantly increased than those in group A, but the autophagosomes in group C were significantly lower than those in group B.

Conclusion

The exosomes from ADSCs can promote the peripheral nerve regeneration. The mechanism may be related to reducing SCs apoptosis, inhibiting SCs autophagy, and reducing nerve Wallerian degeneration.

Keywords: Exosome, adipose-derived stem cells, peripheral nerve injury, nerve regeneration, rat

周围神经损伤在临床上极为常见,每年因创伤导致的周围神经损伤患者超过 50 万例,约占所有创伤患者总数的 2.8%[1]。周围神经损伤后常导致肢体运动和感觉功能障碍,给患者的生活和工作带来严重影响。周围神经损伤的修复主要采用显微缝合方法,但临床效果欠佳。近年来,国内外学者对如何促进周围神经损伤修复进行了大量研究,如利用电刺激、NGF、BMSCs 等治疗[2-3],虽然具有一定作用,但效果仍不满意。因此,进一步探索周围神经再生机制,寻找新的治疗靶点,探索新的治疗方法,是提高周围神经损伤治疗效果的重要方向。外泌体是细胞内多泡体与细胞膜融合后释放到细胞外基质中的一种膜性囊泡[4]。近年研究发现,脂肪干细胞(adipose-derived stem cells,ADSCs)与雪旺细胞(Schwann cells,SCs)共培养后,能上调髓鞘相关指标,进而对神经损伤修复再生起到一定作用[5]。另有多名学者发现多种干细胞来源的外泌体均可促进损伤的神经组织修复[6-8]。因此,本研究拟观察 ADSCs 来源外泌体对坐骨神经损伤后再生的作用,为临床应用外泌体治疗周围神经损伤奠定实验基础。

1. 材料与方法

1.1. 实验动物及主要试剂、仪器

健康成年 SD 大鼠 40 只,雌雄不限,体质量 220~240 g,由海军军医大学(第二军医大学)动物实验中心提供。

戊巴比妥钠(上海科丰化学试剂有限公司);TUNEL 试剂盒(Roche 公司,瑞士);外泌体提取试剂盒(和光公司,日本)。酶标仪(Thermo 公司,美国);LE2202S 型电子天平(Sartorius 公司,德国);Image-Pro Plus 6.0 图像分析软件(Media Cybernetics 公司,美国);LeicaDC500 病理图像分析系统(Leica 公司,德国);H-7650 透射电镜(Hitachi 公司,日本)。

1.2. ADSCs 来源外泌体的提取及分析

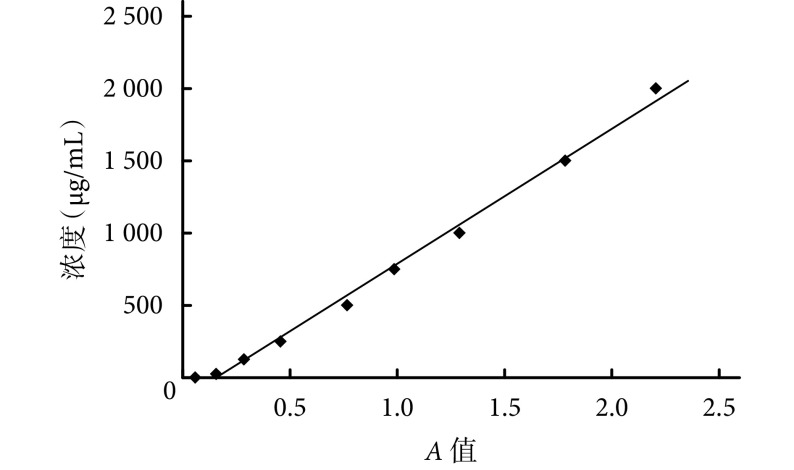

取 4 只 SD 大鼠断颈处死,固定于解剖平板上。① 参照 Nielsen 等[9]和张静等[10]的方法分离 ADSCs。无菌环境下取大鼠腹股沟脂肪组织,剪碎至糊状,PBS 洗涤 1 次,以 300×g 离心 3 min;弃上清,加入 0.1%Ⅰ型胶原酶,37℃ 水浴消化 60 min,待组织块沉淀后吸取上清液至另一 5 mL 离心管,用含 10%FBS 的 L-DMEM 终止消化,以 400×g 离心 5 min;弃上清液,用含 10%FBS 的 L-DMEM 重悬沉淀后接种至一 6 cm 培养皿中,37℃、5%CO2 培养箱中培养,24 h 首次换培养液,以后每 3 天换液 1 次。② 参照 Hervera 等[7]的方法提取外泌体。取上述第 3 代对数生长期 ADSCs,用无血清 L-DMEM 继续培养,待细胞汇合度达 70%~80% 时,FBS 洗涤,经 0.22 μm 滤膜过滤,将滤液经 100 000×g 离心 18 h,去除上清液,用外泌体提取试剂盒提取外泌体。采用 BCA 法对提取的外泌体进行蛋白浓度定量分析,于 750 nm 波长下用酶标仪测吸光度(A)值,根据 BCA 标准曲线测得外泌体蛋白浓度标准曲线。采用纳米粒子追踪分析技术(nanosight tracking analysis,NTA)检测外泌体直径分布。

1.3. 大鼠坐骨神经损伤模型建立及分组

将 36 只 SD 大鼠随机分成 3 组,每组 12 只。A 组为正常对照组,B 组为坐骨神经挤压损伤组,C 组为 ADSCs 来源外泌体治疗坐骨神经挤压损伤组。将所有大鼠以 2.5% 戊巴比妥钠(40 mg/kg)腹腔注射麻醉,取俯卧位,于左侧股后正中行纵切口,长约 1 cm,分离皮下肌肉,暴露坐骨神经。A 组距坐骨结节 6~8 mm 处标记后缝合切口;B、C 组距坐骨结节 6~8 mm 处用大止血钳上两扣夹闭坐骨神经干,造成坐骨神经挤压损伤模型,缝合切口[11]。术后次日开始,A、B 组大鼠尾静脉注射 PBS 液 200 μL,C 组大鼠尾静脉注射含 100 μg(蛋白量)ADSCs 来源外泌体的 PBS 液 200 μL;每周注射 1 次,持续 12 周。注射结束 1 周后(造模 13 周时)处死大鼠,取标记或损伤处上、下 2 mm 坐骨神经进行观测。

1.4. 观测指标

1.4.1. 大体观察

术后观察实验大鼠存活、切口愈合、肌肉萎缩及后肢运动情况。

1.4.2. 组织学观察

取各组坐骨神经置于甲醛固定,石蜡包埋、切片,片厚 4 μm,取部分切片行常规 HE 染色,镜下观察神经束情况。

1.4.3. TUNEL 检测 SCs 凋亡

将上述各组坐骨神经组织切片脱蜡,按 TUNEL 试剂盒方法染色后,镜下观察 SCs 细胞凋亡情况,凋亡细胞核呈棕褐色颗粒。采用 Image-Pro Plus 6.0 图像分析软件,于 400 倍下取 5 个视野计数凋亡细胞,取均值。

1.4.4. 透射电镜观察 SCs 自噬情况

取各组坐骨神经组织置于 2.5% 戊二醛固定,制备电镜样品,透射电镜下观察 SCs 自噬情况。

1.5. 统计学方法

采用 SPSS19.0 统计软件进行分析。数据以均数±标准差表示,组间比较采用单因素方差分析,两两比较采用 SNK 检验;检验水准 α=0.05。

2. 结果

2.1. ADSCs 来源外泌体相关分析

BCA 定量分析测得 ADSCs 来源外泌体蛋白浓度为 1.44 μg/mL。见图 1。

图 1.

BCA standard curve of the exosomes from ADSCs

ADSCs 来源外泌体的 BCA 标准曲线

根据 NTA 检测外泌体直径分布和数量,外泌体平均直径约为 86.07 nm,浓度为 1.83×107个/mL;检测外泌体分布可知 30.56% 外泌体直径介于 60~80 nm,68.31% 外泌体直径介于 80~100 nm。见表 1。

表 1.

Distribution of the exosomes from ADSCs

ADSCs 来源外泌体分布

| 百分比(%)

Percentile (%) |

粒子数(×107个/mL)

Number of particles (×107/mL) |

粒径(nm)

Particle size (nm) |

| 1.13 | 0.24 | 40~ 60 |

| 30.56 | 6.49 | 60~ 80 |

| 68.31 | 14.51 | 80~100 |

2.2. 大体观察

动物造模术后第 1 天开始进食;13 周时切口愈合良好,无感染发生。A 组左下肢无明显异常,行走功能正常。B、C 组足趾瘫痪,张开受限,肌肉萎缩,小腿前侧萎缩较后侧明显;其中,C 组瘫痪、足趾挛缩及肌肉萎缩程度均轻于 B 组,且行走功能好于 B 组。见图 2。

图 2.

Gross observation of animals at 13 weeks after modeling

造模后 13 周各组动物大体观察

a. A 组;b. B 组;c. C 组

a. Group A; b. Group B; c. Group C

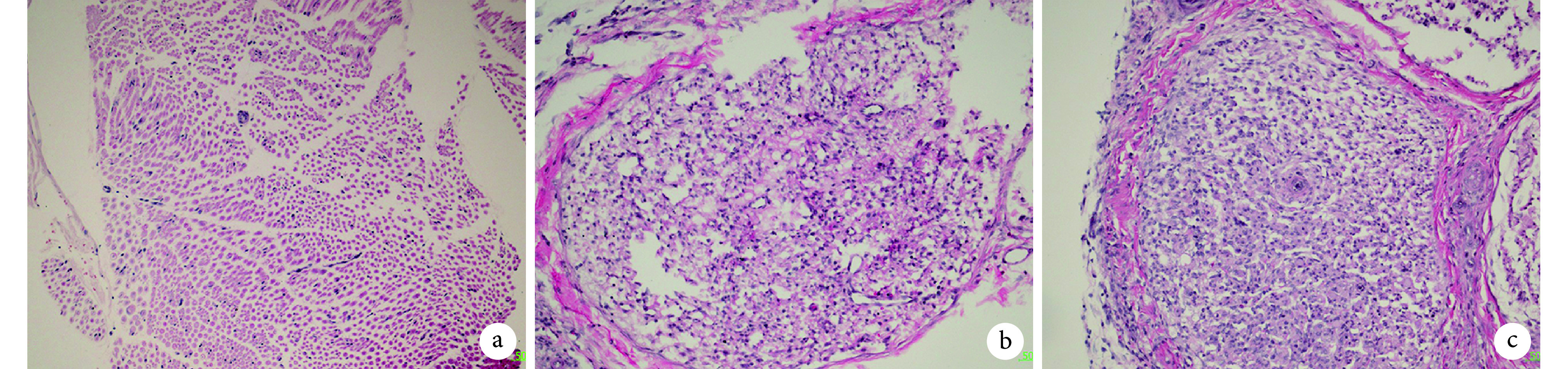

2.3. 组织学观察

HE 染色示,A 组神经束排列紧密完整,束膜形态规则;与 A 组相比,B 组神经束形态破坏、束膜不规则,有较多无细胞结构和组织碎片;与 B 组相比,C 组神经束内损伤减轻,神经束膜较完整、有序,但其完整性不及 A 组。见图 3。

图 3.

HE staining of sciatic nerve at 13 weeks after modeling (×200)

造模后 13 周各组坐骨神经 HE 染色观察(×200)

a. A 组;b. B 组;c. C 组

a. Group A; b. Group B; c. Group C

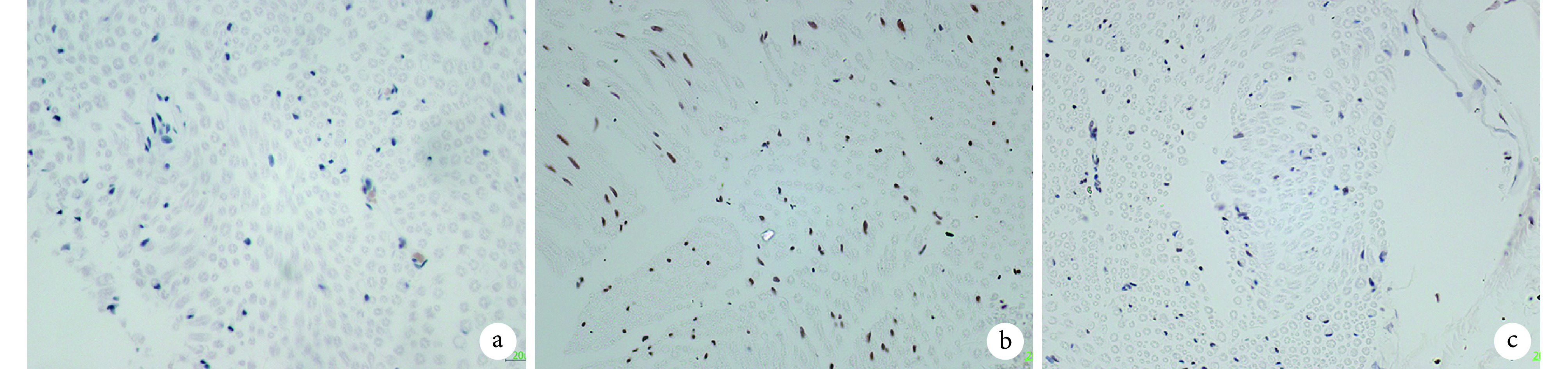

2.4. TUNEL 检测细胞凋亡

A、B、C 组 SCs 凋亡细胞数分别为(8.40±1.72)、(49.60±5.38)、(23.80±4.93)个/视野;B、C 组显著多于 A 组,B 组显著多于 C 组,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.01)。见图 4。

图 4.

TUNEL staining of SCs apoptosis in sciatic nerve at 13 weeks after modeling (×400)

造模后 13 周 TUNEL 法检测各组坐骨神经 SCs 凋亡情况(×400)

a. A 组;b. B 组;c. C 组

a. Group A; b. Group B; c. Group C

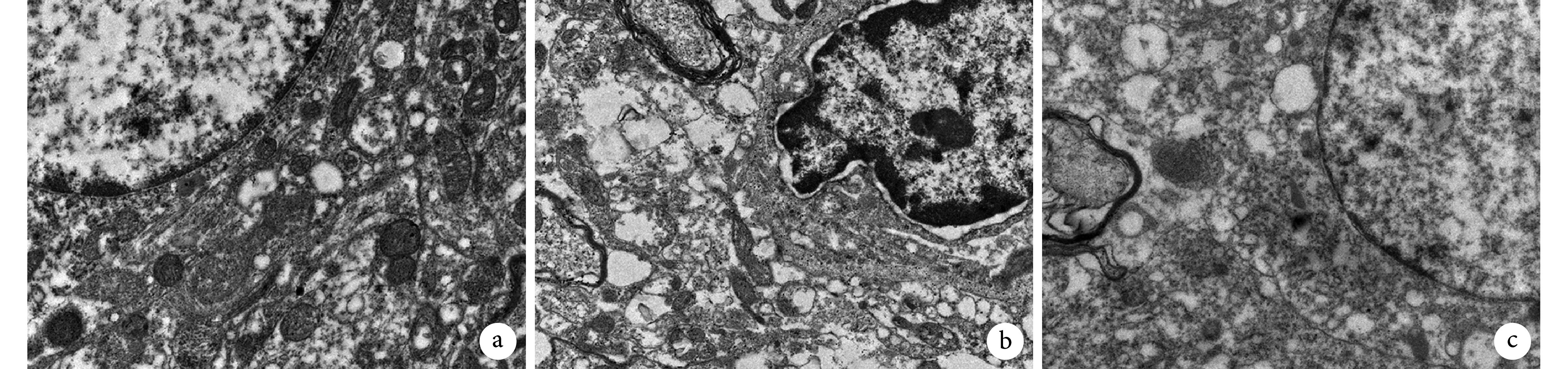

2.5. 透射电镜观察 SCs 自噬情况

透射电镜观察示,A 组大鼠坐骨神经中 SCs 细胞核完整,无明显自噬体;与 A 组相比,B 组 SCs 自噬体数量明显增多,细胞核变形;与 B 组相比,C 组 SCs 自噬体数量明显减少,细胞核呈圆形。见图 5。

图 5.

Transmission electron microscope observation of SCs autophagy in sciatic nerve at 13 weeks after modeling (×10 k)

造模后 13 周透射电镜观察各组坐骨神经 SCs 自噬情况(×10 k)

a. A组;b. B组;c. C组

a. Group A; b. Group B; c. Group C

3. 讨论

周围神经损伤后常导致肢体运动和感觉功能障碍,严重影响患者的生活和工作。由于神经损伤后再生速度缓慢,轴突需要相当长的时间才能再生到达靶器官,在靶器官重新获得神经支配之前,肌肉可能已发生不可逆萎缩[12-13]。此外,周围神经损伤后,脊髓运动神经元和脊神经节的感觉神经元因失去与周围靶器官的联系而死亡[14-15],这些因素均严重影响了周围神经损伤后的再生效果。因此,进一步探索治疗周围神经损伤新方法,如何加速周围神经损伤后轴突再生,是急需解决的重要问题。

外泌体包含的生物活性物质在组织损伤中具有修复作用,为临床治疗组织损伤提供了新思路[16-17]。近年研究发现,ADSCs 与 SCs 共培养后能上调髓鞘相关指标,进而对损伤神经的再生起到一定作用[5]。另有研究发现多种干细胞来源的外泌体均可促进神经再生修复[18],但是 ADSCs 分泌的外泌体是否可以促进周围神经的再生目前未见相关报道。鉴于此,我们将 ADSCs 来源外泌体注入坐骨神经损伤的 SD 大鼠体内,通过大体观察、神经纤维束髓鞘再生情况及 SCs 凋亡和自噬等指标,来评价其对大鼠坐骨神经损伤后再生的作用。结果发现与 B 组相比,C 组大鼠损伤患肢的肌肉萎缩较轻,坐骨神经束膜较完整,纤维束再生良好,SCs 凋亡显著降低,自噬减轻。表明 ADSCs 来源外泌体可以促进大鼠坐骨神经损伤后的纤维再生。

此外,我们在本实验中还发现,大鼠坐骨神经损伤后给予 ADSCs 来源外泌体治疗后,SCs 内自噬体明显减少。而在周围神经损伤修复过程中,SCs 发挥了关键作用[19]。周围神经损伤后经历一系列复杂变化,局部发生瓦勒变性,其核心变化是髓鞘和轴突的崩解,SCs 自噬作为瓦勒变性的开始,在周围神经损伤后的一系列病理生理变化过程中起到了重要作用[20]。早期,SCs 通过自噬作用清除瓦勒变性所产生的坏死组织;后期,SCs 逐渐增生,在各类蛋白及黏附分子作用下,使排列紊乱、无序的 SCs 重新排列,形成有序管道结构—Büngner 带,引导神经元再生的轴突在其中生长并到达效应器[21]。本研究结果提示,ADSCs 来源外泌体在周围神经损伤修复过程中起重要作用,通过减少 SCs 凋亡、减轻其自噬作用并促进 Büngner 带形成,有利于神经元轴突再生,从而加速周围神经损伤的修复。

Funding Statement

上海市卫生系统优秀学科带头人培养计划(2017BR034);中国博士后科学基金(2017M623362、2018T111131)

Training Plan for Outstanding Subjects in Shanghai Health System (2017BR034); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M623362, 2018T1111131)

References

- 1.Castillo-Galván ML, Martínez-Ruiz FM, de la Garza-Castro O, et al Study of peripheral nerve injury in trauma patients. Gac Med Mex. 2014;150(6):527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadeghian H, Wolfe GI Therapy update in nerve, neuromuscular junction and myopathic disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(5):496–501. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833d7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooney DS, Wimmers EG, Ibrahim Z, et al Mesenchymal stem cells enhance nerve regeneration in a rat sciatic nerve repair and hindlimb transplant model. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31306. doi: 10.1038/srep31306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaput N, Taïeb J, Schartz NE, et al Exosome-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53(3):234–239. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0472-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue Y, Yang X, Zhang L, et al Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound upregulates pro-myelination indicators of Schwann cells enhanced by co-culture with adipose-derived stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2016;49(6):720–728. doi: 10.1111/cpr.2016.49.issue-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.李超然, 黄桂林, 王帅 间充质干细胞来源外泌体促进损伤组织修复与再生的应用与进展. 中国组织工程研究. 2018;22(1):133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hervera A, Virgiliis De F, Palmisano I, et al Reactive oxygen species regulate axonal regeneration through the release of exosomal NADPH oxidase 2 complexes into injured axons. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(3):307–319. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu B, Zhang Y, Du XF, et al Neurons secrete miR-132-containing exosomes to regulate brain vascular integrity. Cell Res. 2017;27(7):882–897. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen EØ, Chen L, Hansen JO, et al Optimizing osteogenic differentiation of ovine adipose-derived stem cells by osteogenic induction medium and FGFb, BMP2, or NELL1 in vitro . Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:9781393. doi: 10.1155/2018/9781393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.张静, 易阳艳, 阳水发, 等 脂肪干细胞来源外泌体对人脐静脉血管内皮细胞增殖、迁移及管样分化的影响. 中国修复重建外科杂志. 2018;32(10):1351–1357. doi: 10.7507/1002-1892.201804016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.林耀发, 宗海洋, 胡显腾, 等 大鼠坐骨神经损伤后 Spastin 表达变化的实验研究. 中国修复重建外科杂志. 2017;31(1):80–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mor D, Kendig MD, Kang JWM, et al Peripheral nerve injury impairs the ability to maintain behavioural flexibility following acute stress in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2017;328:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobianchi S, Jaramillo J, Luvisetto S, et al Botulinum neurotoxin A promotes functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury by increasing regeneration of myelinated fibers. Neuroscience. 2017;359:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JT, Medress ZA, Barres BA Axon degeneration: molecular mechanisms of a self-destruction pathway. J Cell Biol. 2012;196(1):7–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi S, Ninomiya T, Kohno T, et al Cobalt inhibits motility of axonal mitochondria and induces axonal degeneration in cultured dorsal root ganglion cells of rat. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2018;34(2):93–107. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu XS, et al Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells promote axonal growth of cortical neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(4):2659–2673. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9851-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.周敏, 洪莉, 胡鸣, 等 外泌体在周围神经损伤中的研究进展. 医学综述. 2017;23(13):2497–2500. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2084.2017.13.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tassew NG, Charish J, Shabanzadeh AP, et al Exosomes mediate mobilization of autocrine Wnt10b to promote axonal regeneration in the injured CNS. Cell Rep. 2017;20(1):99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Sanchez JA, Pilch KS, van der Lans M, et al After nerve injury, lineage tracing shows that myelin and remak Schwann cells elongate extensively and branch to form repair Schwann cells, which shorten radically on remyelination. J Neurosci. 2017;37(37):9086–9099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1453-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clements MP, Byrne E, Camarillo Guerrero LF, et al The wound microenvironment reprograms Schwann cells to invasive mesenchymal-like cells to drive peripheral nerve regeneration. Neuron. 2017;96(1):98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takamatsu H, Takegahara N, Nakagawa Y, et al Semaphorins guide the entry of dendritic cells into the lymphatics by activating myosin II. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(7):594–600. doi: 10.1038/ni.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]