1. Introduction—variants of SARS-CoV-2

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020 (AJMC Staff, 2020). By August 2021, it affected more than 210 million people globally (Worldometer, 2021). COVID-19 is caused by the “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), genetic variants of which were documented in the UK by the “COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium” (COG-UK) (COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium, 2021). COG-UK announced on 21 December 2020 (AJMC Staff, 2020) that a variant, B.1.1.7 (Zimmer, 2021), containing 17 mutations, caused a new wave of the positive cases in Southern England. On 22 January 2021, the UK prime minister announced that the B.1.1.7 variant was 30% deadlier than the original strain (Rahhal, 2021), though this announcement was argued to be taken cautiously (Williams, 2021). Following the emergence of the variants, many European countries closed their borders to the UK goods or visitors. By July 2021, the WHO website Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants, published an updated list of the viral variants—variants of concern and variants of interest (The World Health Organization, 2021)—while renaming the variants was suggested in January 2021 (Callaway, 2021). The variants of concern include the Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351, B.1.351.2, B.1.351.3), Gamma (P.1, P.1.1, P.1.2), and Delta (B.1.617.2, AY.1, AY.2). These variants can 1) boost transmissibility or drastically change the COVID-19 epidemiology; 2) increase the virulence or change the clinical disease presentation; or 3) decrease the effectiveness of public-health countermeasures or available diagnostics, vaccines, or therapeutics (The World Health Organization, 2021). Though the pandemic could be aggravated by the variants, proving altered transmissibility is difficult without excluding additional factors, including stringency or leniency of the public-health countermeasures or lockdowns and public compliance with them.

The UK variant (Alpha, B.1.1.7) has been reported in the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Poland, Hungry, Iceland, Greece, Colorado, Australia, and other countries (https://virological.org/t/tracking-the-international-spread-of-sars-cov-2-lineages-b-1-1-7-and-b-1-351-501y-v2/592/1 and https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/situation-updates/variants-dashboard). The South African government reported on 18 December 2020 that the N501Y mutation in the viral spike protein (Zimmer, 2021) had emerged independently of the UK variant (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), and this variant then spread in the UK, Europe, Australia, and Asia (Zimmer, 2021). The surge of COVID-19 cases in early 2021 could be attributed to the Alpha B.1.1.7 and Beta B.1.351/501Y.V2 variants from the UK and South Africa, respectively (Tang et al., 2021). This is supported by data presented by https://nextstrain.org, showing the temporal emergence of the cases infected with new viral variants from 19 December 2020 to 12 February 2021. The data suggest that the variants have started to dominate epidemiologically.

2. Spread of the new variants in Iran

Iran is one of the frontiers against the COVID-19 pandemic in the Middle East. Since 24 January 2021, the COVID-19 incidence in Iran has risen slowly with an increasing fatality rate, mostly in the North (Entekhab.ir, 2021a). In late June 2021, new incidence peaks emerged in the Southern states and disseminated to other states (Entekhab.ir, 2021b). By mid-August, officials recorded a high fatality rate of 600 daily. These figures deeply concerned the authorities while they strived to understand the origin and spread of the variants to avoid potentially higher transmission or fatalities (Williams, 2021). The rapid rises of the case numbers may explain the surging new variants among the population. We posit that undetected and speedy circulation of any new variant (irrespective of which dominates) may have increased the hospitalization rates in Iran (Mehdi, 2021; Entekhab.ir, 2021c). Prescribing the antiviral remdesivir and treating the severe cases with convalescent plasma may selectively pressure the virus to subsequently evolve and evade the human immune system. The variants likely undergo a higher selective pressure than the original strain.

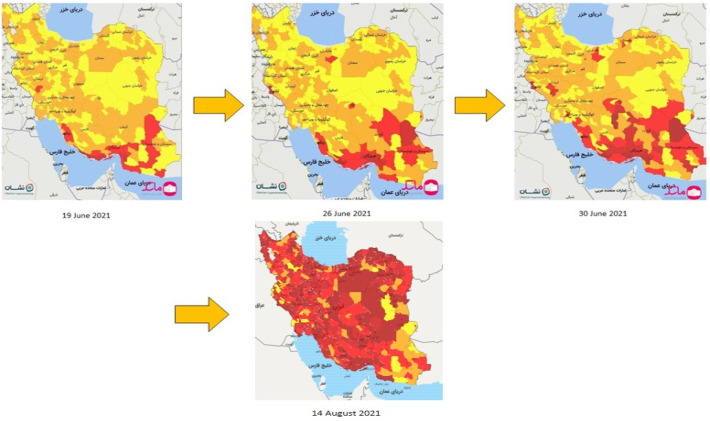

The variants may have potentially arrived into Iran from Pakistan and India through south-eastern Iran. This newest variant was reported in India on 23 June 2021 (BBC World, 2021). Thus, emergence of newer variants, including the Delta Plus SARS-CoV-2 mainly spreading from South to North of Iran (Fig. 1 ), is possible, necessitating urgent action by the decision-makers. Indeed, genetic sequencing showed that many new cases were infected with the variant late in June 2021. Unfortunately, Delta-positive cases were detected in other countries, ranging from the United States to Japan. The delta variant has undergone another mutation, crowning the variant as Delta Plus. The K417N mutation of the spike protein seemingly increases the viral capability to escape human immunity.

Fig. 1.

Increasing number of red-colored cities indicate high admissions of new COVID-19 cases (https://app.mask.ir/map). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Because the K417N mutation was previously observed in South Africa (B.1.351 lineage), we posit that Delta Plus is not a new variant. Although we know little about pathogenicity and virulence of this variant, we suppose that clinical manifestations and transmissibility by the variant may have worsened; thus, we may observe more-severe disease presentations. On 25 June 2021, WHO's Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, the Technical Lead on COVID-19, said that the “Delta variant is a dangerous virus” (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-virtual-press-conference-transcript---25-june-2021). She called this variant more transmissible which may explain the rapid viral spread in Iran.

3. Potential emergence sites of the variants of concern in Iran

The cartography of the high case numbers spreading from the south to the north and finally throughout Iran as documented by the Iranian Health Ministry (https://app.mask.ir/map) shows the directional viral spread with time (Fig. 1).

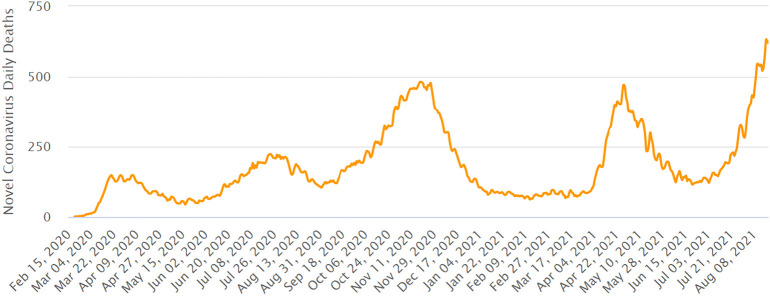

Meanwhile, fatalities rose rapidly to >600 daily, showing the deadliest viral incidence since the virus hit Iran in early 2020 (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Daily fatalities in Iran showing five peaks after the virus hit Iran.

4. A conclusive roadmap to defeat the variants

Experts are generally optimistic that the present vaccines could effectively target the variants (Zimmer, 2021), but the optimism could change with accumulating epidemiological and serological evidence (King, 2021). AstraZeneca indicated that 6–9 months are required to produce an effective vaccine against the new variants (Jolly and Davis, 2021); however, comparing the humoral immune responses with T-cell responses is also important for understanding how vaccinated subjects fight the variants. Recently, the Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla indicated that a booster vaccine dose a year after initial full vaccination may be needed (Lovelace Jr., 2021). Worryingly, the durability of antibody responses in fully vaccinated or semi-vaccinated subjects is still not fully understood.

Because SARS-CoV-2 has undergone genetic evolution 17 months after its global dissemination, flexible public-health policies and specific testing regimes are mandatory to effectively tackle the evolving variants. When writing this letter, no validated diagnostic PCR test was available to distinguish between the variants. However, a RT-PCR method can detect some variants (Bal et al., 2021). Therefore, the corresponding proportions of the new cases should be determined and documented cautiously before widespread Pfizer or BioNTech vaccinations. Although the B.1.1.7 variant is reportedly susceptible to the two vaccines, emerging spike-protein mutations could alter its conformation or epitopes, probably causing vaccine failures (Shi et al., 2021). Thus, strict traveling bans, strict quarantine of international travelers, contact-tracing, testing campaigns, restricting private or public gatherings, mass vaccinations, physical distancing, respiratory and hand hygiene, and face-masking are still pertinent mainstay countermeasures during the pandemic evolution. Iran exemplifies (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) how Delta plus or other variants could spread fast to many regions. Meanwhile, an overwhelmed healthcare taskforce, combating the pandemic and caring for the patients affected by the variants, is further challenged by:

-

1)

a high chance of secondary, multidrug-resistant bacterial infections

-

2)

emotional, mental, and physical fatigue

-

3)

high fatalities because of seasonal flu, secondary infections, or comorbidities.

In conclusion, Delta plus may not be the last SARS-CoV-2 variant. Effective policies expectedly better control the pandemic worldwide. Urgent national and international vaccinations may guarantee the future defeat of SARS-CoV-2, and sophisticated information on the evolving viral genome will facilitate defining and implementing better countermeasures. A genomic surveillance, like the COG-UK, is required internationally to coordinate documentation of the variants because genomic sequencing is not readily available in many low-income and middle-income countries.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

None.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Financial support

No funding was received for writing or publishing this manuscript.

References

- AJMC Staff A timeline of COVID-19 developments in 2020. 2020. https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid19-developments-in-2020

- Bal A., Destras G., Gaymard A., Stefic K., Marlet J., Eymieux S., et al. Two-step strategy for the identification of SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/01 and other variants with spike deletion H69-V70, France, August to December 2020. Euro. Surveill. 2021;26 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBCworld Delta plus India: scientists say too early to tell risk of Covid-19 variant. 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-57564560

- Callaway E. ‘A bloody mess’: Confusion reigns over naming of new COVID variants. 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00097-w [DOI] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Implications of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant VOC 202012/01 | CDC. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/scientific-brief-emerging-variant.html [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium COG-UK report on SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations of interest in the UK 15th January 2021. 2021. https://www.cogconsortium.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Report-2_COG-UK_SARS-CoV-2-Mutations.pdf

- Entekhab.ir وزیر بهداشت: اگر موج جدید شیوع کرونا ما را گرفتار کند، عذاب و سختیهای خطرناکتری را باید تحمل کنیم / وقتی ویروس به چرخش درآید، خیلی خطرناک می شود؛ انگلیسی ها دروغ می گفتند که ۷۰ درصد قدرت انتقال دارد، هم بیماری زایی بسیار بالایی دارد و هم مرگ زایی. 2021. http://www.entekhab.ir/fa/news/597897

- Entekhab.ir آخرین آمار کرونا در ایران، ۸ تیر ۱۴۰۰: فوت ۱۴۲ نفر در شبانه روز گذشته. 2021. http://www.entekhab.ir/fa/news/625278

- Entekhab.ir ورود مازندران به موج پنجم کرونا با ویروس هندی و آفریقایی. 2021. http://www.entekhab.ir/fa/news/625276

- Jolly J., Davis N. AstraZeneca says vaccine against new Covid variants may take six months. 2021. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/11/astrazeneca-says-vaccine-against-new-covid-variant-may-take-six-months

- King A. Vaccines versus the mutants. 2021. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/vaccines-versus-the-mutants-68430

- Lovelace B., Jr. Pfizer CEO says third Covid vaccine dose likely needed within 12 months. 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/15/pfizer-ceo-says-third-covid-vaccine-dose-likely-needed-within-12-months.html

- Mehdi S.Z. Alarm over virus surge in Iran as UK variant spreads. 2021. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/latest-on-coronavirus-outbreak/alarm-over-virus-surge-in-iran-as-uk-variant-spreads/2143897

- Rahhal N. UK PM claims Britain's 'super-covid' variant is 30% more deadly. 2021. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9177419/UK-Prime-Minster-claims-Britains-super-covid-variant-30-deadly.html

- Shi P.Y., Xie X., Zou J., Fontes-Garfias C., Xia H., Swanson K., et al. Neutralization of N501Y mutant SARS-CoV-2 by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited sera. Res. Sq. 2021 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-143532/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.W., Toovey O.T.R., Harvey K.N., Hui D.D.S. Introduction of the South African SARS-CoV-2 variant 501Y.V2 into the UK. J. Infect. 2021;82:e8–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. 2021. https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

- Williams S. Data hint B.1.1.7 could be more deadly than thought. 2021. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/data-hint-b-1-1-7-could-be-more-deadly-than-thought-68383

- Worldometer COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- Zimmer K. A guide to emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. 2021. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/a-guide-to-emerging-sars-cov-2-variants-68387