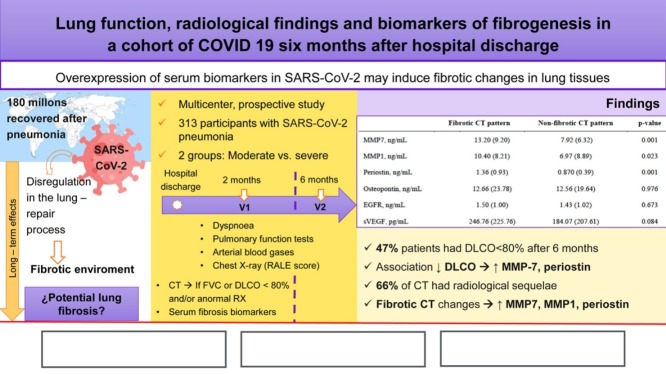

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: 6-MWT, 6 minute-walk test; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; GGO, ground-glass opacity; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula oxygen; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IMV, mechanical ventilation; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; mMRC, modified British Medical Research Council; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; RALE, radiographic assessment of lung edema; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; sEGFR, soluble epidermal growth factor receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

Keywords: COVID-19 sequelae, Fibrotic changes, Lung diffusion, Serum biomarkers, Interstitial lung disease, Chest CT

Abstract

Introduction

Impairment in pulmonary function tests and radiological abnormalities are a major concern in COVID-19 survivors. Our aim is to evaluate functional respiratory parameters, changes in chest CT, and correlation with peripheral blood biomarkers involved in lung fibrosis at two and six months after SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia.

Methods

COVID-FIBROTIC (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04409275) is a multicenter prospective observational cohort study aimed to evaluate discharged patients. Pulmonary function tests, circulating serum biomarkers, chest radiography and chest CT were performed at outpatient visits.

Results

In total, 313, aged 61.12 ± 12.26 years, out of 481 included patients were available. The proportion of patients with DLCO < 80% was 54.6% and 47% at 60 and 180 days. Associated factors with diffusion impairment at 6 months were female sex (OR: 2.97, 95%CI 1.74–5.06, p = 0.001), age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05, p = 0.005), and peak RALE score (OR: 1.22, 95% CI 1.06–1.40, p = 0.005). Patients with altered lung diffusion showed higher levels of MMP-7 (11.54 ± 8.96 vs 6.71 ± 4.25, p = 0.001), and periostin (1.11 ± 0.07 vs 0.84 ± 0.40, p = 0.001). 226 patients underwent CT scan, of whom 149 (66%) had radiological sequelae of COVID-19. In severe patients, 68.35% had ground glass opacities and 38.46% had parenchymal bands. Early fibrotic changes were associated with higher levels of MMP7 (13.20 ± 9.20 vs 7.92 ± 6.32, p = 0.001), MMP1 (10.40 ± 8.21 vs 6.97 ± 8.89, p = 0.023), and periostin (1.36 ± 0.93 vs 0.87 ± 0.39, p = 0.001).

Conclusion

Almost half of patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 pneumonia had impaired pulmonary diffusion six months after discharge. Severe patients showed fibrotic lesions in CT scan and elevated serum biomarkers involved in pulmonary fibrosis.

Abstract

Introducción

El deterioro de la función pulmonar en las pruebas correspondientes y las alteraciones radiológicas son las preocupaciones principales en los supervivientes de la COVID-19. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar los parámetros de la función respiratoria, los cambios en la TC de tórax y la correlación con los biomarcadores en sangre periférica involucrados en la fibrosis pulmonar a los 2 y a los 6 meses tras la neumonía por SARS-CoV-2.

Métodos

El ensayo COVID-FIBROTIC (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04409275) es un estudio de cohortes multicéntrico, prospectivo y observacional cuyo objetivo fue evaluar los pacientes dados de alta. Se realizaron pruebas de función pulmonar, detección de biomarcadores en plasma circulante y radiografía y TC de tórax durante las visitas ambulatorias.

Resultados

En total 313 pacientes, de 61,12 ± 12,26 años, de los 481 incluidos estuvieron disponibles.

La proporción de pacientes con DLCO < 80% fue del 54,6 y del 47% a los 60 y 180 días.

Los factores que se asociaron a la alteración de la difusión a los 6 meses fueron el sexo femenino (OR: 2,97; IC del 95%: 1,74-5,06; p = 0,001), la edad (OR: 1,03; IC del 95%: 1,01-1,05; p = 0,005) y la puntuación RALE más alta (OR: 1,22; IC del 95%: 1,06-1,40; p = 0,005). Los pacientes con alteración de la difusión pulmonar mostraron niveles más altos de MMP-7 (11,54 ± 8,96 frente a 6,71 ± 4,25; p = 0,001) y periostina (1,11 ± 0.07 frente a 0,84 ± 0,40; p = 0,001). Se le realizó una TC a 226 pacientes de los cuales 149 (66%) presentaban secuelas radiológicas de la COVID-19. En los pacientes graves, el 68,35% mostraban opacidades en vidrio esmerilado y el 38,46%, bandas parenquimatosas. Los cambios fibróticos tempranos se asociaron a niveles más altos de MMP7 (13,20 ± 9,20 frente a 7,92 ± 6,32; p = 0,001), MMP1 (10,40 ± 8,21 frente a 6,97 ± 8,89; p = 0,023), y periostina (1,36 ± 0,93 frente a 0,87 ± 0,39; p = 0,001).

Conclusión

Casi la mitad de los pacientes con neumonía moderada o grave por COVID-19 presentaba alteración de la difusión pulmonar 6 meses después del alta. Los pacientes graves mostraban lesiones fibróticas en laTC y un aumento de los biomarcadores séricos relacionados con la fibrosis pulmonar.

Palabras clave: Secuelas por COVID-19, Cambios fibróticos, Difusión pulmonar, Biomarcadores séricos, Enfermedad pulmonar intersticial, TC torácica

Introduction

The global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has affected more than 200 million people, according to the Coronavirus Resource Center at Johns Hopkins University.1 There have been more than four million deaths and 180 million people have recovered. However, there are concerns about long-term effects2 of COVID-19 survivors, irrespective of their initial severity, and these may have a significant impact on quality of life and disability.

Lessons learned from the previous epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 indicate that a subset of patients who survived the disease eventually developed residual pulmonary fibrosis. So, studies that analyzed patients who had recovered from SARS-CoV infection at 3, 6 and 12 months, showed that about 30% had features of fibrosis such as reticular changes in the lung parenchyma.3, 4 These findings occurred mostly in elderly and severe patients.

One report concluded that up to one third of admitted hospital patients with COVID-19 might develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).5 Further, many patients who survived ARDS had a restrictive pattern on lung function that persisted one year after discharge from the intensive care unit.6

Now in SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe COVID-19 has already been associated with impairment in pulmonary function and radiological abnormalities.7 Several studies had data three months after hospital admission, showing a reduced lung diffusing capacity between 21%8 and 57%9 of patients and one-fourth of discharged COVID-19 patients had chest computed tomography (CT) scan abnormalitites.10

A dysregulation in the wound healing process of acute lung injury caused by SARS has been described and some pathways controlled by receptor tyrosine kinases have been implicated.11 The role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the lung repair process has been studied in ARDS12 and as potential biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.13 However, to date the links between SARS-CoV-2 and lung fibrosis remains unclear. We hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 may cause overexpression of biomarkers, which can induce a fibrotic environment in lung tissues. Within an observational, prospective study design, we aimed to evaluate functional respiratory impairment of patients at two and six-months after SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, residual changes in their chest CT, and any correlation with potential peripheral blood biomarkers of lung fibrosis.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

COVID-FIBROTIC (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04409275) is a multicenter prospective observational cohort study aimed to evaluate changes in lung function in patients admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia from 12 centres in Spain. Detailed information about participating hospitals, protocol and definitions are reported in the appendix (appendix, S-1). All adult patients being discharged from hospital after pneumonia due to COVID-19 were suitable for the study. Case definition was confirmed COVID-19 cases were those with a positive nasal and pharyngeal swab sample obtained at admission using real time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and clinical and imaging diagnosis compatible with pneumonia. Patients were followed-up in the post-COVID-19 outpatient clinic and they were asked to participate if they had no exclusion criteria (aged < 18 years, life expectancy less than a year, prior diagnosis of interstitial lung disease [ILD] or COPD).

Ethics

All patients provided written informed consent before inclusion. The study (version 3.0; May 12, 2020) was approved by the Ethics Research Committee from Hospital Clinico, INCLIVA (Valencia, Spain) (2020/149) and by local committees wherever needed. Baseline information (demographic, symptoms at presentation, clinical course, etc.) was retrieved from electronic medical records in all participating centres and de-identified data were entered into an electronic database (Veridata™ EDC).

Procedures

After discharge, patients were re-appointed at two months for V1 and at six months for V2. All data was obtained at the time of outpatient assessment. Data included comorbidities, emergency room assessment variables and clinical assessments during hospitalization (radiology, laboratory findings, clinical signs and symptoms, severity as use of ventilatory support and/or admission to intensive care unit [ICU]). During visits the following procedures were performed: clinical examination, the modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea score,14 pulmonary function tests including spirometry, body plethysmography, measurement of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) (Masterscreen, Jaeger, Germany) and 6 minute-walk test (6-MWT). All procedures were executed according to the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines.15, 16 Arterial blood gases were obtained when haemoglobin oxygen saturation was below 90% or at physician discretion. All patients underwent a chest X-ray and pulmonary damage was quantified by adapting Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema (RALE) score to COVID-19.17 When there were persistent alterations in the radiography and/or impairment in pulmonary function test (FVC < 80% without FEV1/FVC < 70 and/or DLCO < 80%), a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was performed. HRCT scans (SOMATOM, Siemens, Germany; AQUILION, Toshiba, Japan; OPTIMA, General Electric, USA) were obtained in the supine position during breath holding at end-inspiration. Axial reconstructions were performed with a slice thickness of 1 mm, with 1 mm increment, 512 mm × 512 mm. The same protocol adjusted to the different CT machines in each centre was used.

Two experienced radiologists in interstitial lung diseases prospectively evaluated HRCTs blindly in each centre. If a patient had clinical suspicion for pulmonary embolism (PE), additional contrast CTs were performed. The images were classified according to guidance by the Fleischner Society18 based on the presence of ground-glass opacity (GGO), parenchymal bands, bronchiectasis and reticulations. In the case GGO, it was subclassified as a function of affectation > 10% in at least one lung zone. All images were reconstructed with lung and soft tissue kernels and stored in a local picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

For further analysis patients were divided according to WHO Clinical Progression Scale19 in two groups:

-

1.

Moderate disease: hospitalized patients who require supplemental oxygen by mask or nasal prongs.

-

2.

Severe disease: hospitalized patients who require respiratory support by non-invasive ventilation (NIV), high flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC) or intubation and mechanical ventilation (IMV). Care of these patients took place in ICU in most cases.

Serum biomarkers

In five participating hospitals circulating serum biomarkers were determined at hospital discharge. Serum was obtained from peripheral blood samples by centrifugation at 4000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. The serum was collected and stored at −80 °C in a biobank. Four human multi-analyte kits from Milliplex® (Merck Millipore, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) were used to assess the levels of six serum biomarkers. First kit (cat: HMMP2MAG-55K) for analysing matrix metalloproteinases MMP-1 (ng/mL) and MMP-7 (ng/mL) simultaneously; Second kit (cat: HANG2MAG-12K) for analysing soluble Epidermal growth factor receptor (sEGFR) (ng/mL) and Osteopontin (ng/mL); Third kit (cat: HCMBMAG-22K) for analysing Periostin (ng/mL) and Fourth kit (cat: HCYTA-60K) for analysing Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (pg/mL). Samples were diluted 20-fold, 5-fold, 10-fold respectively for the first three kits using the dilution buffer included in the kit. All standards, controls and samples were assayed in duplicate according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Analyte specific antibodies are pre-coated onto magnetic microparticles embedded with fluorophores at set ratios for each unique microparticle region. A magnet in the analyser captures and holds the magnetic beads in a monolayer while two spectrally distinct light emitting diodes (LEDs) illuminate the microparticles using a CCD camera. One LED excites the dyes inside each microparticle, to identify the analyte that is being detected and the second LED excites the Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin (PE) to measure the amount of analyte bound to the microparticles. A minimum of 50 beads per analyte/region was counted. The median fluorescence intensities (MFIs) were determined on a MAGPIX™ analyzer (Luminex Corporation, Austin, Texas, USA). Biomarkers concentrations were calculated using a 5-parameter logistic curve-fitting method from standard's MFIs through xPONENT software, included in the analyser.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was to describe changes in lung function over time in patients who were admitted for COVID-19 pneumonia. Secondary outcomes were to analyze the presence of interstitial findings on CT scan of the lung, prognostic factors for DLCO < 80% at six months, the persistence of dyspnoea after discharge from hospital and the role of biomarkers in initiating post-infection pulmonary fibrosis. Primary and secondary outcomes were studied according COVID-19 clinical course, moderate disease vs. severe disease.

Statistical analysis

We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)20 guidelines for reporting observational studies. Continuous data is presented as mean (standard deviation) and categorical data as absolute frequency and percentage. Normality was checked with the Shapiro–Wilks test. For quantitative variables, mean comparison was carried out using t-test. For qualitative variables, comparison of frequencies between moderate and severe disease was carried out with Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables or chi-square test for contingency tables with more than two categories. Pulmonary function of COVID-19 patients at follow-up was compared using paired t-test for continuous data and McNemar's test otherwise.

Functional parameters variations between two (V1) and six months (V2) according to critical condition were evaluated using linear mixed model with time, critical status and the interaction between them as independent variables. Within-subject correlation was modelled using compound symmetry. Post hoc analysis of interaction was carried out with Bonferroni correction to preserve family-wise error rate.

Stepwise backward-forward logistic regression model was carried out to study prognostic factors for DLCO < 80% versus ≥80% at 6 months. Full model included higher values of D-dimer, ferritin, LDH, and C-reactive protein; age; sex; admission and peak RALE score; dyspnoea at follow-up; and respiratory support with high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation as independent variables. Same model was carried out to study serum biomarkers (MMP-7, MMP-1, and periostin) with the presence of a fibrotic pattern in the CT scan. Included variables were age, sex, and tobacco. Best model was selected according to Akaike's Information Criterion.21

All analyses were carried out using R version 4.02. The statistical cut-off for significance was set at α ≤ 0.05.

Results

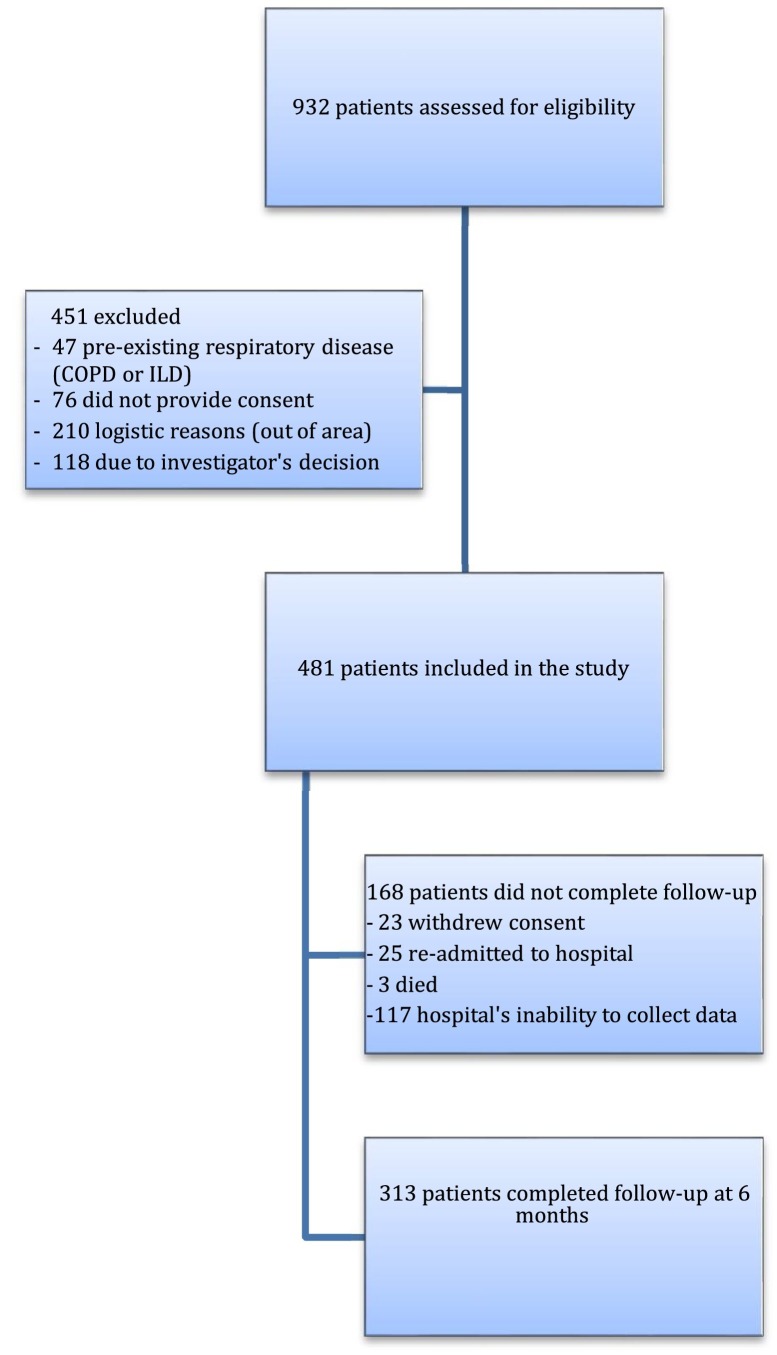

Between May 1, and July 31, 2020, this prospective, multicenter, cohort study evaluated 932 eligible patients who were admitted with pneumonia for SARS-CoV-2 from Respiratory Departments in participating hospitals, of whom 481 were initially considered for follow-up. Reasons for exclusion were logistic reasons as living out of area, previous diagnosis of COPD or ILD, investigator's decision or lack of inform consent. Mainly due to the overload of the health system, as we were in the first peak of the pandemic, some centres were unable to collect all data, therefore the final number of patients available for the second follow-up was 313 (65.1%) (Both groups of patients were similar, appendix S-2) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients discharged from participating hospitals included in the cohort COVID-FIBROTIC.

The mean time for outpatient visits after discharge was 63 ± 12 days for V1 and 181 ± 10 days for V2. The group consisted of 184 males (59%), aged 61.12 ± 12.26 years with a body mass index (BMI) of 28.23 ± 4.78. Other demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are given by COVID-19 severity (moderate vs. severe) in Table 1 . With the exception of sex distribution, there were no differences between both severity groups in terms of age, ethnicity, comorbidities, smoking history and BMI. Severe patients had higher RALE scores and a longer hospital stay (p < 0.001). Severe patients also showed more prominent laboratory abnormalities as lymphocytopenia, elevated D-dimer and higher levels of lactate dehydrogenase, C-reactive protein, ferritin and fibrinogen, than moderate patients (all p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled patients. Moderate disease: hospitalized patients who require supplemental oxygen by mask or nasal prongs. Severe disease: hospitalized patients who require respiratory support by high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation (non-invasive or invasive).

| Total n = 313 |

Moderate COVID-19 n = 226 |

Severe COVID-19 n = 87 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.12 (12.26) | 60.46 (13.06) | 62.83 (9.73) | 0.083 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 184 (58.78%) | 120 (53.10%) | 64 (73.56%) | 0.001 |

| Female | 129 (41.21%) | 106 (46.90%) | 23 (26.44%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 295 (94.25%) | 211 (93.36%) | 84 (96.55%) | 0.776 |

| Latin | 16 (5.11%) | 13 (5.75%) | 3 (3.45%) | |

| Oriental | 1 (0.32%) | 1 (0.44%) | NA | |

| African | 1 (0.32%) | 1 (0.44%) | NA | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.23 (4.78) | 28.37 (4.91) | 27.87 (4.44) | 0.413 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Never-smoker | 174 (55.59%) | 130 (57.52%) | 44 (50.57%) | 0.280 |

| Current smoker | 8 (2.56%) | 7 (3.09%) | 1 (1.14%) | |

| Former smoker | 130 (41.53%) | 88 (38.93%) | 42 (48.27%) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Pulmonary diseasea | 55 (17.57%) | 43 (19.03%) | 12 (13.79%) | 0.276 |

| Hypertension | 126 (40.26%) | 90 (39.82%) | 36 (41.38%) | 0.801 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (16.29%) | 35 (15.49%) | 16 (18.39%) | 0.533 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 32 (10.22%) | 26 (11.5%) | 6 (6.90%) | 0.228 |

| Admission RALE Score | 3.52 (1.67) | 3.23 (1.58) | 4.27 (1.66) | 0.001 |

| Peak RALE Score | 4.88 (1.97) | 4.26 (1.80) | 6.49 (1.42) | 0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization, days | 17.15 (18.36) | 9.49 (5.50) | 36.80 (24.31) | 0.001 |

| Laboratory findingsb | ||||

| Lymphocytes, x10^9/L | 0.89 (0.56) | 1.01 (0.57) | 0.60 (0.42) | 0.001 |

| Lactated dehydrogenase, U/L | 585.33 (292.47) | 516.85 (228.93) | 764.29 (359.32) | 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 116.81 (112.94) | 82.35 (81.53) | 205.53 (133.04) | 0.001 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 1149.58 (1060.68) | 858.5 (752.83) | 1823.24 (1335.94) | 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 19.51 (90.00) | 6.39 (1.58) | 50.66 (162.01) | 0.040 |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 3481.77 (6212.02) | 1662.14 (3084.08) | 8303.8 (9182.01) | 0.001 |

RALE = Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema.

Pulmonary disease: asthma, obstructive sleep apnoea, other.

All laboratory findings are peak values except for lymphocytes which is the lowest value. Data are n (%) or mean (SD).

At 60 days, the proportion of patients with lung diffusion impairment (DLCO < 80%, of predicted) was 54.6%. At 180 days, after hospital discharge, there was a slight improvement but there were still 147 patients (47%) with impaired pulmonary diffusion (p = 0.011). Half of patients complained of dyspnoea at V1 with improvement at V2 when 111 patients (35.46%) had one or more points at mMRC scale (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Pulmonary function of patients at follow-up.

| 2 months post discharge | 6 months post discharge | OR or difference (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVC, L | 3.48 (1.02) | 3.55 (1.00) | 0.06 (0.01–0.12) | 0.007 |

| FVC, % of predicted | 99.02 (18.03) | 100.59 (16.38) | 1.57 (0.26–2.88) | 0.018 |

| FVC < 80%, % of predicted | 45 (14.38%) | 29 (9.27%) | 0.42 (0.19–0.87) | 0.016 |

| FEV1, L | 2.77 (0.81) | 2.811 (0.81) | 0.03 (−0.01–0.07) | 0.090 |

| FEV1, % of predicted | 98.66 (17.12) | 100.04 (16.15) | 1.37 (0.03–2.72) | 0.044 |

| FEV1/FVC | 79.55 (6.98) | 78.96 (6.29) | 0.59 (0.03–1.16) | 0.038 |

| DLCO, % of predicted | 77.75 (19.21) | 81.50 (16.45) | 3.74 (2.20–5.29) | 0.001 |

| DLCO < 80%, % of predicted | 171 (54.63%) | 147 (46.96%) | 0.55 (0.34–0.88) | 0.011 |

| KCO, % of predicted | 91.92 (17.40) | 95.02 (17.24) | 3.09 (1.62–4.56) | 0.001 |

| KCO < 80%, % of predicted | 74 (23.64%) | 57 (18.21%) | 0.5 (0.26–0.92) | 0.024 |

| TLC, % of predicted | 96.37 (14.52%) | 97.6 (14.45) | 1.23 (−0.41–2.88) | 0.140 |

| RV, % of predicted | 99.70 (23.62%) | 100.24 (23.85) | 0.53 (−3.00–4.08) | 0.763 |

| 6 min walking distance, m | 529.18 (96.60) | 542.78 (97.18) | 13.6 (4.33–22.86) | 0.004 |

| mMRC | ||||

| 0 | 153 (48.88%) | 202 (64.54%) | 0.289 (0.16–0.48) | 0.001 |

| ≥1 | 160 (51.12%) | 111 (35.46%) | NA | |

FVC = forced vital capacity. FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second. DLCO = diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide. KCO = diffusion constant. TLC = total lung capacity. RV = residual volume. mMRC = modified British Medical Research Council. Data are n (%) or mean (SD). OR = odds ratio.

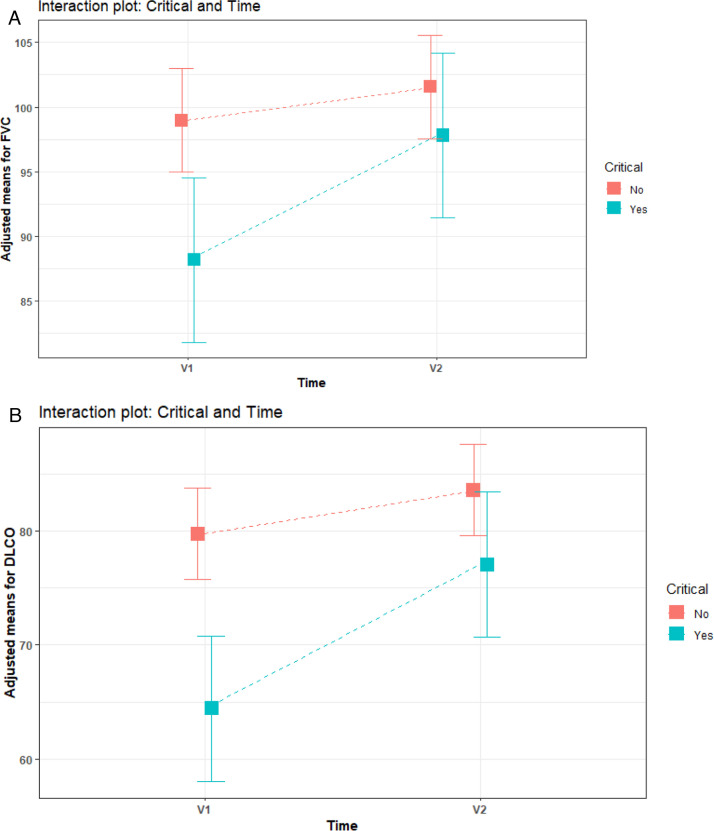

Severe patients (group 2) showed statistically worse levels of FVC and DLCO at V1. However, these levels improved at V2 and no significant differences were found between severe and non-critical or moderate patients (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Interaction plot of functional parameters variation between V1 (two months) and V2 (six months) according to severity (group 1: non critical; group 2: critical). A: FVC%, of predicted. B: DLCO%, of predicted.

Factors associated with diffusion impairment are presented in Table 3 . According to Akaike's information criterion, factors included in the final model were sex (reference category: female) (OR: 2.97, 95%CI 1.74–5.06, p = 0.001), age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05, p = 0.005), peak RALE score (OR: 1.22, 95% CI 1.06–1.40, p = 0.005), and D-dimer (OR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.99–1.00, p = 0.056) all significantly associated with DLCO < 80% (of predicted) at 6 months. Interestingly, a critical clinical course (patients with respiratory support by high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation) was not a predictor of altered diffusion at follow-up.

Table 3.

Stepwise logistic regression analyses (backward-forward stepwise selection: AIC) in patients with diffusion impairment at 6 months.

| Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 | (1.01–1.05) | 0.005 |

| D-dimer peak value | 1.00 | (0.99–1.00) | 0.056 |

| Sex | 2.97 | (1.74–5.06) | 0.001 |

| Peak RALE Score | 1.22 | (1.06–1.40) | 0.005 |

RALE = Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema.

According to study protocol, 226 patients underwent CT scan, of whom 149 (66%) had radiological sequelae of COVID-19. Two thirds of those who required respiratory support by high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation (invasive or non-invasive) had GGO on CT scan; and reticulations, bronchiectasis and parenchymal bands that may indicate early progression to fibrosis were seen in more than one third of patients (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Chest CT at follow-up according to severity of disease. Moderate disease: hospitalized patients who require supplemental oxygen by mask or nasal prongs. Severe disease: hospitalized patients who require respiratory support by high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation (non-invasive or invasive).

| Total n = 226 |

Moderate COVID-19 n = 147 |

Severe COVID-19 n = 79 |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal CT pattern | 77 (34.07%) | 70 (47.62%) | 7 (8.86%) | 0.001 |

| GGO | 108 (47.78%) | 54 (36.73%) | 54 (68.35%) | 0.001 |

| Reticular pattern | 43 (19.02%) | 16 (10.88%) | 27 (34.17%) | 0.001 |

| Bronchiectasis | 47 (20.79%) | 12 (8.16%) | 35 (44.30%) | 0.001 |

| Parenchymal bands | 50 (22.12%) | 20 (13.60%) | 30 (38.46%) | 0.001 |

Data are n (%). GGO = ground glass opacity.

Circulating serum biomarkers were determined in a subset of sites and characteristics of this sub-sample were similar to main cohort, except that they were younger (59.51 ± 13.40 vs 62.29 ± 11.84 years, p = 0.047) (appendix, S-3). Several biomarkers as MMP-7 (14.11 ± 10.09 vs 7.36 ± 5.17, p = 0.001), MMP-1 (10.04 ± 7.33 vs 6.93 ± 9.19, p = 0.001), and periostin (1.28 ± 0.89 vs 0.87 ± 0.4, p = 0.001) were elevated in patients with severe disease compared to those with a moderate clinical course (Table 5 ). Moreover, patients with altered lung diffusion showed higher levels of MMP-7 (11.54 ± 8.96 vs 6.71 ± 4·25, p = 0.001), periostin (1.11 ± 0.07 vs 0.84 ± 0.40, p = 0.001), and VEGF (230.07 ± 223.33 vs 166.74 ± 198.15, p = 0.035) than patients with normal DLCO% (Table 6a ). Finally, early fibrotic changes in CT scan were associated with even higher levels of MMP7 (13.20 ± 9.20 vs 7.92 ± 6.32, p = 0.001), MMP1 (10.40 ± 8.21 vs 6.97 ± 8.89, p = 0.023), and periostin (1.36 ± 0.93 vs 0.87 ± 0.39, p = 0.001) (Table 6b ).

Table 5.

Circulating serum biomarkers in moderate and severe disease.

| Moderate COVID-19 | Severe COVID-19 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP7, ng/mL | 7.36 (5.17) | 14.11 (10.09) | 0.001 |

| MMP1, ng/mL | 6.93 (9.19) | 10.04 (7.33) | 0.001 |

| Periostin, ng/mL | 0.87 (0.40) | 1.28 (0.89) | 0.004 |

| Osteopontin, ng/mL | 13.99 (23.18) | 8.54 (8.67) | 0.345 |

| EGFR, ng/mL | 1.48 (0.98) | 1.35 (1.12) | 0.303 |

| sVEGF, pg/mL | 268.20 (252.12) | 331.30 (298.94) | 0.308 |

Data are mean (SD). MMP = matrix metalloproteinases. EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor. VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

Table 6a.

Distribution of circulating serum fibrosis biomarkers according to abnormal vs normal lung diffusion capacity.

| DLCO < 80% | DLCO ≥ 80% | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP7, ng/mL | 11.54 (8.96) | 6.71 (4.25) | 0.001 |

| MMP1, ng/mL | 8.94 (8.52) | 6.55 (9.03) | 0.056 |

| Periostin, ng/mL | 1.11 (0.07) | 0.84 (0.40) | 0.001 |

| Osteopontin, ng/mL | 12.75 (24.96) | 12.42 (15.33) | 0.909 |

| EGFR, ng/mL | 1.33 (0.91) | 1.55 (1.10) | 0.127 |

| sVEGF, pg/mL | 230.07 (223.33) | 166.74 (198.15) | 0.035 |

Data are mean (SD). MMP = matrix metalloproteinases. EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor. VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor. DLCO = diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide.

Table 6b.

Chest CT and biomarkers. Fibrotic pattern refers to the presence of reticulations, traction bronchiectasis or parenchymal bands.

| Fibrotic CT pattern | Non-fibrotic CT pattern | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP7, ng/mL | 13.20 (9.20) | 7.92 (6.32) | 0.001 |

| MMP1, ng/mL | 10.40 (8.21) | 6.97 (8.89) | 0.023 |

| Periostin, ng/mL | 1.36 (0.93) | 0.870 (0.39) | 0.001 |

| Osteopontin, ng/mL | 12.66 (23.78) | 12.56 (19.64) | 0.976 |

| EGFR, ng/mL | 1.50 (1.00) | 1.43 (1.02) | 0.673 |

| sVEGF, pg/mL | 246.76 (225.76) | 184.07 (207.61) | 0.084 |

Data are mean (SD). MMP = matrix metalloproteinases. EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor. VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor. CT = computed tomography.

A logistic regression analysis showed that MMP7 (OR: 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12, p = 0.002), and periostin (OR: 3.49, 95% CI: 1.83–6.68, p = 0.001) remained as independent factors related with the presence of early fibrotic changes in the CT scan (appendix, S-4, S-5, S-6).

Discussion

This multicenter, prospective study of hospitalized patients with moderate and severe COVID-19 pneumonia showed chest CT abnormalities, elevated blood biomarkers related to fibrogenesis, and alterations in lung function up to 6 months after hospital discharge.

The results of lung function assessment showed that 47% of patients had decreased pulmonary diffusion after 6 months and one third of the cohort suffered dyspnoea. CT findings as a reticular pattern, traction bronchiectasis or parenchymal bands, that may indicate early progression to fibrosis were seen in 20% of patients.

Several studies have presented data on lung function and CT findings in survivors of COVID-19. First reports from discharged patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia showed that 47% of them had impairment of diffusion capacity at one month.22 A cohort of 133 patients evaluated at 60 and 100 days showed a recovery in diffusion capacity, from being impaired in 31% of patients to 21% patients.8 Data from 103 patients at three months showed that 24% of them had reduced DLCO, and opacities on CT scan were seen in 25% of patients. They found no differences between patients admitted to ICU compared to those who were not admitted.10 In contrast, in a study with a longer follow-up assessment of lung diffusion, 6 months after symptom onset, alteration of DLCO was found in 56% of patients who required HFNC or IMV, compared to 29% of those who required only supplemental oxygen.23

We have seen, in our patients, a clear improvement in pulmonary function tests between two and six months after hospital discharge, and no differences are found among severe and moderate patients regarding FVC and DLCO at six months.

Our results showed that only 9% of patients with severe disease had normal CT findings, and GGO was present in almost 70%. A cohort of patients followed 153 days after hospital discharge showed that GGO was seen in 44%,22 however they included in their study mild patients (not requiring supplemental oxygen). One-fifth of our patients had bronchiectasis at 6 months, this finding requires further comments as they may be related to pulmonary fibrotic changes (traction bronchiectasis) but the potential of viral infections to produce bronchiectasis should not be underestimated.24

Our multivariate analysis revealed that peak RALE score, and age, as expected, were associated to diffusion impairment; yet surprisingly, female sex is a prognostic factor for DLCO < 80% in our cohort. We do not have an explanation for that, but such finding was also reported in another study where women had two-fold risk for diffusion impairment compared to men.23 Also, a prospective study in COVID-19 patients at 12 months following hospitalization showed an odds ratio of 8.61 of impaired DLCO associated with female sex.25

Clinically, the most striking effect in COVID-19 survivors is diffusion abnormality. Previous reports from SARS outbreak survivors showed that after one year 20% of them had altered diffusion.4 Further, in a small cohort of health workers, followed for 15 years, 38% had a mild impairment in lung diffusion.26 All coronaviruses share the same pathogenic mechanism that binds to a cell surface receptor to enter the host (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 [ACE-2]). Pneumocytes overexpress ACE-2 that results in viral expansion and diffuse alveolar damage. It has been hypothesized that endothelial cell dysfunction may play a role in complicated COVID-19, as initiating post-infection pulmonary fibrosis and vascular remodelling.27 As described in ARDS, after lung injury, a subset of patients seem to be unable to clear the provisional extracellular matrix (ECM) and exuberant fibroproliferation can lead to residual fibrosis with pulmonary dysfunction.28

Serum biomarkers involved in pulmonary fibrosis were evaluated in selected sites in our cohort and MMP-7, MMP-1 and periostin were elevated in patients with severe disease. Furthermore, increased levels of MMP-7, and periostin were obtained in patients with lower DLCO, and remarkably the highest values of MMP-7, MMP-1 and periostin were seen in patients with early fibrotic changes in CT scan. MMP-7 and MMP-1 are described as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.13 MMP-7 serum levels have been related to early fibrotic changes on CT scan in asymptomatic patients with familial interstitial pneumonia.29 Serum levels of periostin were higher in patients with IPF and inversely correlated with pulmonary function in these patients.30 Our results have not shown different levels according to severity of disease in some biomarkers related to SARS-induced pulmonary fibrosis as soluble epidermal growth factor receptor (sEGFR)11 or osteopontin which is related to activation of several precursors responsible of worse outcomes in COVID-19 patients.31

Our study has several limitations. First, we do not have baseline data of pulmonary function. Second, chronic interstitial lung abnormalities may be underestimated, as we do not have previous CT scan. Although patients with COPD or ILD were excluded, asymptomatic underlying lung disease, whatever unlikely, cannot be excluded. Third, not all patients underwent CT scan, as per protocol, only those with alterations in chest X-ray and/or diffusion impairment at first follow-up had a CT scan. This approach, in line with the guidance of the British Thoracic Society,32 was adopted to mitigate the overload of the health system. Fourth, we could not study serum biomarkers in the whole group, mainly due to logistic reasons. Patients included in the study were similar to the rest of the group with the exception that they were younger, which may underestimate the results as senescence cells increase the expression of MMPs.33

Patients in our study were those admitted and then discharged from pulmonary departments, and this may carry some bias. During the first pandemic wave, patients with more severe COVID-19 were controlled mainly by pulmonologists in the majority of hospitals. This scenario gives us an insight into the cases that will have the highest risk of developing complications.

To conclude, patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 pneumonia showed an improvement in lung function tests at 6 months. However 47% of them still had impaired pulmonary diffusion. Alterations in CT scan as parenchymal bands that may indicate early fibrotic lesions were seen in 38% of severe COVID-19 patients. Moreover, higher values of serum biomarkers related to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis were identified at hospital discharge in severe COVID-19 patients. Following recommendations for clinical observational studies on post COVID-19 condition,34 we think that severe COVID-19 patients should be offered protocolized longer follow-up, and specialist ILD services should be considered to manage these patients.

Authors’ contributions

JS-C, BS, and JT contributed to the literature search, study design, data interpretation and critical revision of the work. ER-B, AL-M, and IM-T did all laboratory analysis. BS, JT, EF-F, JNS-C, VM, CL-R, LC, ALA, SH, CL, JAR, JLR-H, and AM did all study assessments, study visits, and completed data entry. JAC-A was the independent statistician and analyzed all data. JBS critically revised the manuscript and provided additional statistical support. All authors had full access to all the data and contributed to article writing and editing and approved its submission. JS-C was responsible for the decision to submit the article.

Data sharing

De-identified clinical data might be made available to other investigators after approval by the institutional review board, when all follow-up studies are finished as we have investigations for COVID-19 in progress.

Conflict of interest

The results presented have not been published previously in whole or part. The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institute of Health Carlos III (COV20/01209), Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain. We thank all the staff of the COVID-FIBROTIC team (see Appendix). We also thank Natividad Blasco PhD for her technical support and Lorena Peiro PhD, INCLIVA biobank director, member of the Spanish Biobank Network, for her work in the handling of blood samples. Finally, we are very grateful to patients who had suffered from the pandemic and yet were always willing to help in our work.

References

- 1.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [accessed 11.8.21].

- 2.Shah W., Hillman T., Playford E.D., Hishmeh L. Managing the long term effects of covid-19: summary of NICE, SIGN, and RCGP rapid guideline. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui D.S., Joynt G.M., Wong K.T., Aarli B., Ikdahl E., Lund K.M.A., et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Thorax. 2005;60:401–409. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.030205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui D.S., Wong K.T., Ko F.W., Tam L.S., Chan D.P., Woo J., et al. The 1-year impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in a cohort of survivors. Chest. 2005;128:2247–2261. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herridge M.S., Cheung A.M., Tansey C.M., Matte-Martyn A., Diaz-Granados N., Al-Saidi F., et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guler S.A., Ebner L., Beigelman C., Bridevaux P.O., Brutsche M., Clarenbach C., et al. Pulmonary function and radiological features four months after COVID-19: first results from the national prospective observational Swiss COVID-19 lung study. Eur Respir J. 2021:2003690. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03690-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnweber T., Sahanic S., Pizzini A., Luger A., Schwabl C., Sonnweber B., et al. Cardiopulmonary recovery after COVID-19 - an observational prospective multi-center trial. Eur Respir J. 2020:2003481. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03481-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibila O., Albacar N., Perea L., Faner R., Torralba Y., Hernandez-Gonzalez F., et al. Lung function sequelae in COVID-19 patients 3 months after hospital discharge. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57(Suppl. 2):59–61. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerum T.V., Aaløkken T.M., Brønstad E., Aarli B., Ikdahl E., Lund K.M.A., et al. Dyspnoea, lung function and CT findings three months after hospital admission for COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020:2003448. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03448-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkataraman T., Coleman C.M., Frieman M.B. Overactive epidermal growth factor receptor signaling leads to increased fibrosis after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Virol. 2017;91:e00182–e00217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00182-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aschner Y., Zemans R.L., Yamashita C.M., Downey G.P. Matrix metalloproteinases and protein tyrosine kinases: potential novel targets in acute lung injury and ARDS. Chest. 2014;146:1081–1091. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosas I.O., Richards T.J., Konishi K., Zhang Y., Gibson K., Lokshin A.E., et al. MMP1 and MMP7 as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bestall J.C., Paul E.A., Garrod R., Garnham R., Jones P.W.W.J. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:581–586. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham B.L., Steenbruggen I., Miller M.R., Barjaktarevic I.Z., Cooper B.G., Hall G.L., et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update an official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e70–e88. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1590ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham B.L., Brusasco V., Burgos F., Cooper B.G., Jensen R., Kendrick A., et al. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:16. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00016-2016. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(5):1650016. doi:10.1183/13993003.50016-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong H.Y.F., Lam H., Fong A.H.T., Leung B.S.T., Chin T., Lo C., et al. Frequency and distribution of chest radiographic findings in COVID-19 positive patients. Radiology. 2020:201160. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansell D.M., Bankier A.A., MacMahon H., McLoud T.C., Müller N.L., Remy J. Fleischner society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall J.C., Murthy S., Diaz J., Adhikari N.K., Angus D.C., Arabi Y.M., et al. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e192–e197. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akaike H. In: Information theory and an extension of the maximun likehood principle. Petrov B.N., Csáki F., editors. Akadémiai Kiadó; Budapest: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mo X., Jian W., Su Z., Chen M., Peng H., Peng P., et al. Abnormal pulmonary function in COVID-19 patients at time of hospital discharge. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2001217. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Gu X., et al. 6-Month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Garcia M.A., Aksamit T.R., Aliberti S. Bronchiectasis as a long-term consequence of SARS-COVID-19 pneumonia: future studies are needed. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X., Liu X., Zhou Y., Yu H., Li R., Zhan Q., et al. 3-Month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month respiratory outcomes in patients following COVID-19-related hospitalisation: a prospective study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:747–754. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang P., Li J., Liu H., Han N., Ju J., Kou Y., et al. Long-term bone and lung consequences associated with hospital-acquired severe acute respiratory syndrome: a 15-year follow-up from a prospective cohort study. Bone Res. 2020;8:8. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huertas A., Montani D., Savale L., Pichon J., Tu L., Parent F., et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction: a major player in SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19)? Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001634. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01634-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burnham E.L., Janssen W.J., Riches D.W.H., Moss M., Downey G.P. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:276–285. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00196412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kropski J.A., Pritchett J.M., Zoz D.F., Crossno P.F., Markin C., Garnett E.T., et al. Extensive phenotyping of individuals at risk for familial interstitial pneumonia reveals clues to the pathogenesis of interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:417–426. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okamoto M., Hoshino T., Kitasato Y., Sakazaki Y., Kawayama T., Fujimoto K., et al. Periostin, a matrix protein, is a novel biomarker for idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1119–1127. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00059810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adu-Agyeiwaah Y., Grant M.B., Obukhov A.G. The potential role of osteopontin and furin in worsening disease outcomes in COVID-19 patients with pre-existing diabetes. Cells. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/cells9112528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George P.M., Barratt S.L., Condliffe R., Desai S.R., Devaraj A., Forrest I., et al. Respiratory follow-up of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Thorax. 2020;75:1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su L., Dong Y., Wang Y., Wang Y., Guan B., Lu Y., et al. Potential role of senescent macrophages in radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:527. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soriano J.B., Waterer G., Peñalvo J.L., Rello J. Nefer Sinuhe and clinical research assessing post-COVID-19 syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2021:2004423. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04423-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]