Abstract

Purpose of Review

Cancer and heart disease are the leading causes of mortality in the USA. Advances in cancer therapies, namely, the development and use of chemotherapeutic agents alone or in combination, are becoming increasingly prevalent.

Recent Findings

Many chemotherapeutic agents have been associated with adverse cardiovascular manifestations. The mechanisms of these sequelae remain incompletely understood. In particular, microtubule inhibitor (MTI) agents have been related to the development of heart failure, myocardial ischemia, and conduction abnormalities. At present, there are no guidelines for patients undergoing MTI therapy as it pertains to both preventative and mitigatory strategies for cardiovascular complications. We conducted a literature review focusing on content related to the use of MTIs and their effect on the cardiovascular system.

Summary

MTIs have been associated with various forms of cardiotoxicity, and fatal cardiotoxicities are rare. The most well-described cardiotoxicities are brady- and tachyarrhythmias. The co-administration of anthracycline-based agents with MTIs can increase the risk of cardiotoxicity.

Keywords: Mitotic inhibitors, Cardiotoxicity, Cardio-oncology, Arrhythmia, Heart failure, Endothelial dysfunction

Introduction

Cancer remains one of the largest causes of mortality in the USA and is second only to heart disease [1]. Many advances in early diagnosis and a wealth of therapeutic agents have contributed to a drastic decline in overall mortality. Still, they have led to an increased prevalence of individuals living with a history of cancer having undergone chemotherapy. Despite advances and favorable outcomes, morbidity, as it pertains to these agents’ therapeutic toxicity, continues to rise, with adverse cardiovascular manifestations being amongst the most prevalent. Currently, agents with the most focus and understanding of cardiotoxicity have been anthracycline-based therapies and anti-HER2 treatments. In 2013, ACCF/AHA HF guidelines addressed the potential contribution of anthracyclines and anti-HER2 agents to cardiotoxicity development [2]. Furthermore, investigations comparing survivors of cancers treated with these agents to those of the general population have also noted a significant increase in cardiovascular disease development in the former [3]. Given the considerable and overwhelming data associating chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity, we aim to identify the relationship between MTI agents and cardiovascular disease development.

Methods

Our literature review consisted of isolating studies and analyses from PubMed, Google Scholar, and EBSCO. The following medical text included but was not limited to “microtubule inhibitors,” “ischemia,” “heart failure,” “arrhythmia,” “cardiotoxicity,” and “chemotherapy.” We screened articles relevant to the topic of microtubule inhibitors and cardiac manifestations. A literature review was organized into general functionality and background of microtubule inhibitors followed by specific cardiovascular manifestations pertaining to the cardiac structure, vascularity, and the conduction system. As it is included within the manuscript, data were extracted from the studies identified and general definitions of terms including toxicity criteria were cross-referenced to promote generalizability of cardiac manifestations.

Microtubule Inhibitors

Dysregulation of the cell cycle is the hallmark of malignant disease, and thus, clinical targeting of mitotic pathways has been an essential strategy of cancer therapy. Anti-microtubular agents are amongst the oldest and most reliable antineoplastic drugs. They mediate cell death mechanistically by disrupting microtubule dynamics, resulting in chromosomal dysregulation, abnormal spindle formation, and eventual cell cycle arrest. These agents have demonstrated clinical efficacy in a wide range of human malignancies. Microtubule inhibitors consist of a broad class of drugs, which can be further categorized into agents that either stabilize or destabilize microtubules through dysregulation of ß-tubulin binding domains [4].

Taxanes and epothilones are microtubule-stabilizing agents and promote the polymerization of microtubules to enact their antineoplastic effect. Taxanes, which include the anticancer medications paclitaxel and docetaxel, were first discovered in the early 1960s and were derived from the Pacific yew tree. These medications have a demonstrated efficacy in lung, ovarian, and breast cancers. Vinca alkaloids are destabilizing agents and are responsible for microtubule depolymerization and suppression. Vinca alkaloids included the archetypical anticancer medications vinblastine and vincristine and were first discovered in the 1950s. These agents were isolated from the Madagascar periwinkle plant and have been critical in treating lymphoma, leukemia, and breast and lung cancers [5].

By their very nature, anti-microtubular agents have demonstrable selectivity for rapidly dividing cells due to dynamic spindle activity during mitosis. Even in the presence of this specificity, there remains an ever-present risk of off-target effects to cells in other stages of the cell cycle. Medication-induced microtubular dysfunction in non-malignant cells and subsequent harmful side effects have been observed. Cardiotoxicity has been a well-documented phenomenon with many antiproliferative agents. The true incidence of consequences from antimitotic therapy across the spectrum of cardiovascular disease from cardiovascular structure, coronary vascularity, and the potentiation of cardiac dysrhythmias has not been well-studied [6].

Heart Failure

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) common toxicity criteria stratify chemotherapy-related heart failure (HF) from grades 0 to IV by echocardiographic changes in ejection fraction and responsiveness to HF therapy (Table 1) [8]. The literature supporting antimicrotubule agent–mediated HF has been varied and partially confounded by multi-agent antiproliferative regimens’ ubiquity (Table 2). Taxane-based antimitotic agents have been implicated in HF in approximately 2–8% of patients receiving therapy [6]. Monotherapy studies comparing anthracycline- and taxane-based treatments in breast cancer patients demonstrated that taxane monotherapy had a significantly lower cardiotoxicity rate than anthracycline-based single regimens. Sledge et al. showed that patients in a doxorubicin monotherapy group consisting of 245 total patients had an 8.7% incidence of grade III or higher cardiac complications than 3.7% in the paclitaxel-only treatment group with 242 total patients [17]. In a small study of 50 patients, 10 patients developed at least grade I or II cardiotoxicity. The median reduction in the left ventricular ejection fraction was 48% from 60% [7••]. The typical breast cancer combination regimen of doxorubicin, an anthracycline, and paclitaxel has been shown to increase the incidence of heart failure in patients significantly. Gehl et al. noted that 50% of patients, 15 of 30, on combination therapy had reported LVEF reductions, while 20% or 6 out of those 30 patients developed clinical HF [18••]. This deleterious impact has been hypothesized to be due to the increase in doxorubicin’s cardiac uptake due to pharmacokinetic decreases in doxurubicin clearance with dual therapy [19••]. Interestingly, studies have demonstrated that this effect is not observed in patients on docetaxel and doxorubicin regimens [20]. However, both paclitaxel and docetaxel promote doxorubicinol metabolite formation from doxorubicin, which may contribute to cardiotoxicity [21]. Concomitant paclitaxel may promote systolic dysfunction at cumulative doses lower than would be expected with doxorubicin alone [22]. Likewise, concomitant paclitaxel therapy appears to synergistically contribute to trastuzumab-induced myocardial dysfunction, mediated by inhibition of the ErbB2/neuregulin pathway [23].

Table 1.

Common terminology criteria for adverse events, adapted from the National Cancer Institute [7••]

| Complication | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | - | Asymptomatic no EKG changes, and minimal lab abnormalities | Severe symptoms, cardiac enzymes abnormal, and EKG changes | Life-threatening consequences, hemodynamic instability | Death |

| Hean failure | Asymptomatic with lab or cardiac imaging abnormalities | Symptoms with moderate activity or exertion | Symptoms at rest or with minimal activity or exertion leading to hospitalization | Life-threatening consequences, urgent intervention required | Death |

| Bradycardia | Asymptomatic, no intervention indicated | Symptomatic, intervention not indicated, medication changed | Symptomatic, intervention needed | Life-threatening consequences, urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Pericardial effusion | - | Asymptomatic effusion size small-to--moderate | Effusion with physiologic consequences | Life-threatening consequences, urgent intervention indicated | Death |

Table 2.

Common microtubule inhibitors, clinical indications, and associated cardiotoxicity [9]

| MTI class | Mechanism of action | MTI agent | Clinical application | Cardiotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinca alkaloid | Microtubule destabilization | Vincristine Vindesine Vinblastine Vinflunine |

Acute lymphocytic Leukemia Lymphoma Lung cancer NSCLC Breast cancer |

Pulmonary hypertension [10, 11] Myocardial ischemia* [12–14] |

| Taxanes | Microtubule stabilization | Paclitaxel Docetaxel | Ovarian cancer Breast cancer Non-small cell lung cancer HENT cancer Prostate cancer Stomach cancer |

Heart failure [6] Autonomic dysfunction [15] Sinus bradycardia [16] |

| Epothilones | Microtubule stabilization | Ixabepilone | Breast cancer |

Case reports

Vinca alkaloids’ role in potentiating HF is even less clearly defined, as they are very commonly used in concert with multiple anticancer therapies. Some studies that have evaluated vincristine monotherapy have not demonstrated a meaningful incidence of HF or cardiotoxicity [24]. In patients with pre-existing cardiomyopathy, paclitaxel is safe as a single agent (without concomitant anthracycline use) in a small study of nine patients [25]. The true incidence of antimitotic agent-mediated HF is challenging to discern. Further elucidation of the etiology is complicated by the reliance on multi-agent regimens with varying impacts on cardiotoxicity.

Myocardial Ischemia

NCI common toxicity criteria stratify cardiac ischemia or myocardial infarction (MI) from grades 0 to IV by biochemical elevations in cardiac enzymes, ischemic changes on electrocardiography, and degree of hemodynamic instability. Studies have demonstrated that up to 3–5% of patients receiving taxane-based therapies have evidence of myocardial ischemia [26, 27]. A survey by Rowinsky et al. showed anginal equivalents in 7 out of 140 patients treated with taxol-based therapies [28]. On the contrary, low incidences (0.27%) of cardiac events (grade III or IV) have been reported within 2 weeks of paclitaxel administration [29]. Furthermore, there have been reported cases of Vinca alkaloid–mediated development of coronary ischemia and myocardial infarction [12, 13]. House et al. described the case of a patient who developed acute MI in close temporal association with Vinca alkaloid administration [14]. Mechanistically, it has been hypothesized that the rapid cell cycle arrest mediated by microtubule inhibitors can preferentially impact cardiac endothelium, thereby potentiating ischemia and infarction (Fig. 1) [30]. Given the lack of supporting literature and direct studies, the exact mechanism through which myocardial ischemia occurs is challenging to elucidate. Many patients on Vinca alkaloid therapy are treated for tumors of lymphoid origin. As such, many of these patients receive mediastinal radiation, which is an independent risk factor for myocardial ischemia and infarction [31]. The intermittent incidence and reports of Prinzmetal’s angina have also given rise to the theory that a vasospastic process could be a potential mediator [13]. Risk factors for chemotherapy-related ischemia have been established to be age, pre-existing coronary artery disease (CAD), and radiation therapy history [26]. The body of literature at this time suggests that antimitotic therapy has a small but demonstrated risk of myocardial ischemia or infarction, particularly in the setting of known risk factors.

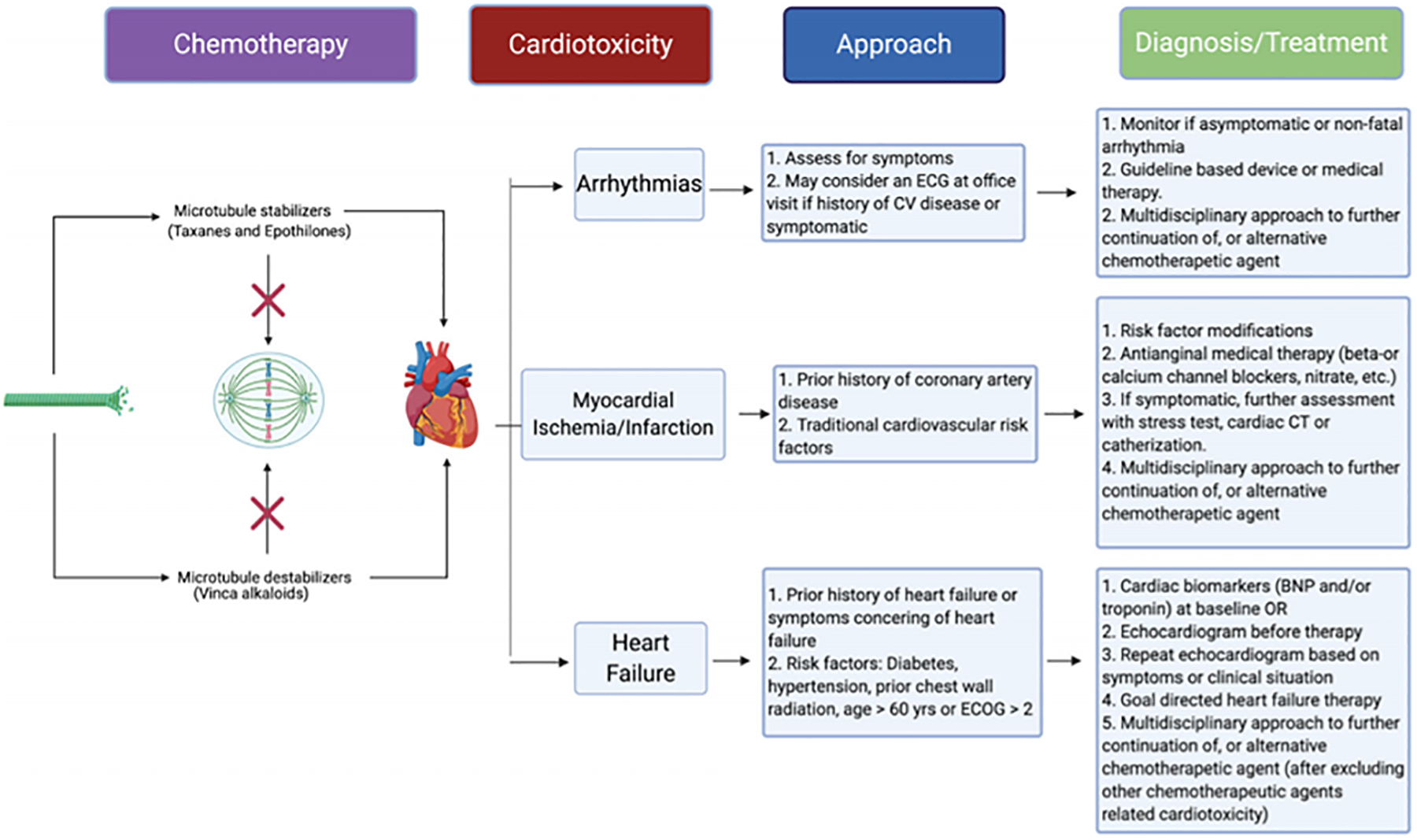

Fig. 1.

Schemata of microtubule inhibitors, common cardiotoxicities, and proposed recommendations

Arrhythmia

The relationship between microtubule inhibitors and arrhythmia has not been well-established. The phrase chemotherapy treatment-induced arrhythmia (CTIA) was first introduced in 2009, with findings predominantly focused on anthracycline-induced atrial fibrillation [32]. CTIA is thought to be multi-factorial with theories suggestive of specific molecular pathway disruption from a primary perspective and tissue damage resulting in secondary arrhythmogenic manifestations. Blurred lines exist between the causality of chemotherapeutic agents instead of cancer itself, which predisposes patients to arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. In fact, Ostenfeld et al. demonstrated a significant relative risk of cancer development in patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation (6656/269,742-absolute risk, 2.5%; 95% confidence intervals [CI], 2.4–2.5%) [33]. Despite relationships between several agents such as anthracyclines and antimetabolites, microtubule inhibitors pertain to arrhythmia have primarily been represented by case reports or small-sample size studies.

To date, literature has failed to correlate therapeutic doses of common microtubule inhibitors to the development of fatal arrhythmias. However, higher than therapeutic levels have been shown to induce bradycardia and tachycardia with atrial fibrillation affecting 1% of 90 patients studied who received paclitaxel [34]. Additionally, Rowinsky et al. found that ventricular arrhythmias, including ectopic beats, have also been observed in 5% of patients receiving taxol-based therapy for refractory ovarian carcinoma [28, 35]. In one retrospective study, the use of taxol contributed to unimpressive rates of atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia at 0.18 and 0.26%, respectively, of the pooled 3400 patients being studied [29]. In a study conducted by McGuire et al., asymptomatic bradycardia was observed in 29% of participants in addition to two manifestations of Mobitz type I AV bock []. Rare occurrences of life-threatening arrhythmia, including ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation development, have been mentioned as possible side effects, and according to Arbuck et al., 0.26% (9 of 3400) developed VT or VF. However, additional studies have failed to replicate this occurrence [29].

In general, the manifestations of conduction abnormality have been benign. According to one study, 50% of patients developed ECG changes with 26% of sinus tachycardia, 13% non-specific ST-T changes, 4% QT prolongation, and 3% and 4% right and left bundle branch block, respectively [36]. Theories have been presented, such as taxol-mediated autonomic cardiac modulation; however, specific studies have not been conducted to expand this etiology [37]. The majority of findings have been conducted on frog and rabbit hearts, which demonstrated bradycardia, AV block, and asystole [38]. At present, an overwhelming consensus of the current literature suggests a lack of significant contribution to life-threatening disease [39]. Furthermore, as agents popularly are used in conjunction with one another, perhaps an increase in the incidence of conduction abnormalities will be observed. For the time being, unlike those mentioned above (i.e., HF and ischemia), patients without documented arrhythmia or conduction system disease before chemotherapy do not require monitoring [32].

Pericardial Effusion

The manifestation of pericardial effusion due to microtubule inhibitors is not well-reported. Pericardial effusion has the potential to lead to cardiac tamponade and death. The co-administration of chemotherapeutic agents known to cause cardiac tamponade such as cytarabine, cyclophosphamide, and tretinoin with microtubule inhibitors could confound the exact etiology and further complicate whether microtubule inhibitors were at least partially responsible agents. Interestingly, microtubule inhibitors have been utilized to treat malignant pericardial effusions, as demonstrated in several reports showing paclitaxel’s efficacy in breast cancer patients [40, 41].

Other Cardiotoxicities

Rare cardiotoxicity such as pulmonary hypertension has been described with the utilization of MTI agents. Vincristine has been reported to cause pulmonary veno-occlusive disease when administered with other chemotherapeutic agents [10, 11]. A study examining veno-thromboembolism in ovarian cancer patients did not reveal increased incidence from neoadjuvant use of several chemotherapeutic agents, including paclitaxel and docetaxel [42]. Pleural effusion and peripheral edema via capillary leak from docetaxel have been reported in a small study of 24 patients [43]. Administration of dexamethasone before its administration has been shown to mitigate the degree of edema [44]. Two cases of myocarditis after paclitaxel initiation have been reported. Interestingly, both patients had thymoma, and a possibility of paraneoplastic syndrome related myocarditis could not be excluded [45, 46]. Additionally, Dermitzakis et al. demonstrated that paclitaxel mediates orthostatic hypotension through autonomic dysregulation of parasympathetic and sympathetic pathways, attenuated by discontinuation of taxol-based therapy [15].

Prevention and Mitigation

A consensus of recommendations currently lacks as it pertains to the prevention and mitigation of disease manifestations. Given the lack of data regarding the mitigation and prevention of cardiotoxicity secondary to MTI therapy, some strategies suggested have been extrapolated from other treatment regimens.

Regarding patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, the level of safety when administering MTIs is unclear. In a study conducted by Markman et al., patients on combination therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin or cisplatin were observed [47]. Of the 15 patients included with an underlying cardiac pathology including coronary artery disease (CAD), tachyarrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, or prior myocardial infarction developed a worsening of their pre-existing condition. Though controversial, there is a suggestion of these agents’ safety alone or in combination with one another. On the inverse, it was recommended to withhold MTI therapy in patients with pre-existing ischemic heart disease, prior conduction abnormalities, and CHF. Vital signs should be monitored frequently during therapeutic infusion, and continuous cardiac monitoring can be employed for patients with known conduction abnormalities with prior infusion therapy [48]. When administering docetaxel, a preventative strategy includes a regimen of premedication with glucocorticoids to mitigate fluid retention’s side effect due to increased permeability [49, 50].

For patients without the pre-existing disease, one of the main focuses of therapy includes a strategy to target and intervene upon new-onset cardiac dysfunction, namely as it pertains to heart failure. Patients are generally treated with standard heart failure medications (e.g., beta-blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers), and theorized screening methods with echocardiographic and laboratory data, such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) have been proposed. Though no guideline exists at present, a study focusing on the potential manifestations of docetaxel demonstrated both a rise in BNP in addition to a reduction of E to A ratios, indicating the development of abnormal myocardial relaxation [51]. Left ventricular dysfunction is a complication of anthracycline and paclitaxel co-administration, which has been hypothesized to be due to an increase in doxorubicin’s cardiac uptake due to changes in pharmacokinetics with dual therapy [18••]. Dexrazoxane has been demonstrated to mechanistically attenuate cardiotoxicity through the chelation of iron and subsequent reduction in superoxide ion formation [52]. From a conduction system standpoint, certain MTIs such as eribulin, a marine sponge derivative with macrolide effects, have been shown to prolong the QT interval, and serial monitoring is suggested [39].

Overall, based on a lack of guidelines, further studies from both a preventative and mitigation standpoint are needed to develop definitive strategies, especially as they pertain to MTI therapies. Thus far, the recommendations are mostly anecdotal but have been well-received given the increasing incidence of observed sequelae associated with MTI agents.

Management

The incidences of severe forms of cardiotoxicity are low. Asymptomatic bradycardia is the most common cardiotoxicity. However, fatal cardiotoxicities have been reported as described above. There is no guideline or expert consensus regarding the surveillance, diagnosis, monitoring, and management of MTI-induced cardiotoxicity. Asymptomatic patients with pre-existing arrhythmia or conduction disease (e.g., sinus node dysfunction, atrioventricular, or bundle branch block) should have a baseline EKG at the initial visit proceeding with the chemotherapy and ambulatory 12-lead EKG when signs and symptoms for bradyarrhythmia are present. Symptomatic patients or those with advanced atrioventricular blocks should be promptly treated as per the guideline [53•].

Osman and Elkady have identified high-risk features (diabetes, hypertension, age greater than 60 years, prior chest radiation, and performance status 2) associated with reducing LV function in paclitaxel-administered patients []. These patients are at higher risk when concomitant anthracycline or other cardiotoxic agents are administered. We recommend performing a baseline echocardiogram with speckle tracking in patients with cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) and known cardiovascular conditions (e.g., known as chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease) receiving MTIs. Follow-up echocardiograms should be obtained if symptoms or clinical picture warrant. An alternative approach is to get baseline cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and BNP. Early detection of cardiotoxicity with these markers was demonstrated in breast cancer patients who were administered MTIs with trastuzumab and anthracycline [54]. The late manifestation of cardiomyopathy is not well-established with MTIs. When anti-HER2 or anthracycline agents are given along with paclitaxel, we recommend following the European Society of Medical Oncology guideline for surveillance and management [55].

Traditional cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, hypertension, age, dyslipidemia, etc.) can cause endothelial dysfunction [56]. Patients with risk factors are at even higher risk when they receive MTIs. We strongly advise optimization of lifestyle modification or intensification of medical therapy to mitigate the risk factors during pre-chemotherapy screening visits. When patients present with anginal or angina-equivalent symptoms, ischemic workup should be considered. The armamentarium of testing can include non-invasive assessment with a stress test or cardiac computer tomography angiography, or invasive coronary angiography, depending on the presentation’s severity. Beta- or calcium-channel blockers and long-acting nitrates can be considered first-line anti-anginal therapy. In whom MTI-induced coronary spasm is suspected, a calcium-channel blocker should be given as first-line therapy as recommended in a recent coronary spasm guideline [57]. The graphic summary of our recommendations is presented in Fig. 1.

Conclusion

Herein, we synthesized recommendations based on existing data on cardiotoxicity mechanisms and available therapeutic options targeting proposed mechanisms. However, there is a lack of robust data on both the cardiotoxicity of MTI therapy and subsequent prevention and mitigation of cardiovascular disease. The paucity of data is likely a consequence of these agents’ relative age and confounding multidrug regimens that prevent simple identification of causal agents. Large-scale studies and utilization of large registries can estimate the prevalence of MTI-induced cardiotoxicity and identify effective preventative or treatment strategies. Sensitive tests such as cardiac biomarkers and speckle tracking echocardiography can provide more insights into subclinical cardiotoxicity. High-risk or symptomatic patients should be referred to cardio-oncologists for routine monitoring and formulation of treatment plans that would allow patients to receive chemotherapy with minimal cardiac sequelae. When significant cardiotoxicity ensues, cardio-oncologists can play an essential role in decision-making for further continuation of MTIs.

Acknowledgements

The figures were created using biorender.com

Abbreviations

- MTI

Microtubule inhibitors

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- CHF

Congestive heart failure

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CTIA

Chemotherapy treatment-induced arrhythmia

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

Footnotes

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardio-oncology

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Heron M, Deaths: leading causes for 2017. 2019: National Vital Statistics Reports. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Writing Committee M, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armenian SH, Xu L, Ky B, Sun C, Farol LT, Pal SK, et al. Cardiovascular disease among survivors of adult-onset cancer: a community-based retrospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan KS, Koh CG, Li HY. Mitosis-targeted anti-cancer therapies: where they stand. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez EA. Microtubule inhibitors: differentiating tubulin-inhibiting agents based on mechanisms of action, clinical activity, and resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(8):2086–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curigliano G, Mayer EL, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Goldhirsch A. Cardiac toxicity from systemic cancer therapy: a comprehensive review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53(2):94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.••.Osman M and Elkady M, A prospective study to evaluate the effect of paclitaxel on cardiac ejection fraction. Breast Care (Basel), 2017. 12(4): p. 255–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study followed recipients of paclitaxel and noted a median ejection fraction (EF) decrease by approximately 12%. During 30-month follow-up post-treatment, 20% of patients developed grade 1 or 2 cardiotoxicity.

- 8.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events e.S.D.o.H.a.H. Services, Editor. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loong HH, Yeo W. Microtubule-targeting agents in oncology and therapeutic potential in hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight BK, Rose AG. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease after chemotherapy. Thorax. 1985;40(11):874–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swift GL, Gibbs A, Campbell IA, Wagenvoort CA, Tuthill D. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur Respir J. 1993;6(4):596–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lejonc JL, et al. Myocardial infarction following vinblastine treatment. Lancet. 1980;2(8196):692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancey RS, Talpaz M. Vindesine-associated angina and ECG changes. Cancer Treat Rep. 1982;66(3):587–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.House KW, Simon SR, Pugh RP. Chemotherapy-induced myocardial infarction in a young man with Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15(2):122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dermitzakis EV, Kimiskidis VK, Lazaridis G, Alexopoulou Z, Timotheadou E, Papanikolaou A, et al. The impact of paclitaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy on the autonomous nervous system of patients with ovarian cancer. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(1):190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuire WP, et al. Taxol: a unique antineoplastic agent with significant activity in advanced ovarian epithelial neoplasms. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(4):273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sledge GW, Neuberg D, Bernardo P, Ingle JN, Martino S, Rowinsky EK, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and the combination of doxorubicin and paclitaxel as front-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: an intergroup trial (E1193). J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):588–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehl J, Boesgaard M, Paaske T, Vittrup Jensen B, Dombernowsky P. Combined doxorubicin and paclitaxel in advanced breast cancer: effective and cardiotoxic. Ann Oncol. 1996;7(7):687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minotti G, et al. Paclitaxel and docetaxel enhance the metabolism of doxorubicin to toxic species in human myocardium. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(6):1511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misset JL, Dieras V, Gruia G, Bourgeois H, Cvitkovic E, Kalla S, et al. Dose-finding study of docetaxel and doxorubicin in first-line treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(5):553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvatorelli E, Menna P, Cascegna S, Liberi G, Calafiore AM, Gianni L, et al. Paclitaxel and docetaxel stimulation of doxorubicinol formation in the human heart: implications for cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin-taxane chemotherapies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318(1):424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giordano SH, Booser DJ, Murray JL, Ibrahim NK, Rahman ZU, Valero V, et al. A detailed evaluation of cardiac toxicity: a phase II study of doxorubicin and one- or three-hour-infusion paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(11): 3360–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pentassuglia L, Timolati F, Seifriz F, Abudukadier K, Suter TM, Zuppinger C. Inhibition of ErbB2/neuregulin signaling augments paclitaxel-induced cardiotoxicity in adult ventricular myocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(8):1588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brugarolas A, Lacave AJ, Ribas A, Miralles MTG. Vincristine (NSC 67574) in non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma. Results of a phase II clinical study. Eur J Cancer. 1978;14(5):501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gollerkeri A, Harrold L, Rose M, Jain D, Burtness BA. Use of paclitaxel in patients with pre-existing cardiomyopathy: a review of our experience. Int J Cancer. 2001;93(1):139–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.••.Rosa GM, et al. , Update on cardiotoxicity of anti-cancer treatments. Eur J Clin Invest, 2016. 46(3): p. 264–84. A synopsis of chemotherapuetic agents and cardiotoxic manifestations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Recommendations pertaining to potential diagnostic tools and their relevance to early recognition of cardiac pathologies as they relate to cardiac toxicity.

- 19.••.Chang H-M, et al. , Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: best practices in diagnosis, prevention, and management: part 1. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2017. 70(20): p. 2536–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article highlights cardiac manifestations of chemotherapuetic agents and the importance of prevention and treatment of cardiac disease in patients undergoing oncologic therapies. A significant focus of this paper pertains to additonal cardiotoxicities in survivors of prior chemotherapy and the need fo rmultidisciplinary care between cardiologists and oncologists.

- 28.Rowinsky EK, McGuire WP, Guarnieri T, Fisherman JS, Christian MC, Donehower RC. Cardiac disturbances during the administration of taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(9):1704–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arbuck SG, et al. A reassessment of cardiac toxicity associated with Taxol. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1993;15:117–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikaelian I, Buness A, de Vera-Mudry MC, Kanwal C, Coluccio D, Rasmussen E, et al. Primary endothelial damage is the mechanism of cardiotoxicity of tubulin-binding drugs. Toxicol Sci. 2010;117(1):144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marmagkiolis K, Finch W, Tsitlakidou D, Josephs T, Iliescu C, Best JF, et al. Radiation toxicity to the cardiovascular system. Curr Oncol Rep. 2016;18(3):15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guglin M, Aljayeh M, Saiyad S, Ali R, Curtis AB. Introducing a new entity: chemotherapy-induced arrhythmia. Europace. 2009;11(12):1579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostenfeld EB, Erichsen R, Pedersen L, Farkas DK, Weiss NS, Sørensen HT. Atrial fibrillation as a marker of occult cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e102861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brouty-Boye D, Kolonias D, Lampidis TJ. Antiproliferative activity of taxol on human tumor and normal breast cells vs. effects on cardiac cells. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(4):571–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowinsky EK. The development and clinical utility of the taxane class of antimicrotubule chemotherapy agents. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:353–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamineni P, Prakasa K, Hasan SP, Ravi A, Dawkins F. Cardiotoxicities of paclitaxel in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(7):995. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ekholm EM, et al. Impairment of heart rate variability during paclitaxel therapy. Cancer. 2000;88(9):2149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tekol Y Negative chronotropic and atrioventricular blocking effects of taxine on isolated frog heart and its acute toxicity in mice. Planta Med. 1985;51(5):357–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cardiotoxicity of Chemotherapeutic Agents. 2017: Nova Biomedical. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Einama T, Sato K, Tsuda H, Mochizuki H. Successful treatment of malignant pericardial effusion, using weekly paclitaxel, in a patient with breast cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11(5):412–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishiba T, et al. A case of cardiac tamponade due to breast cancer treated with weekly paclitaxel. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2012;39(12):2060–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chavan DM, Huang Z, Song K, Parimi LRH, Yang XS, Zhang X, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism following the neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen for epithelial type of ovarian cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(42):e7935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semb KA, Aamdal S, Oian P. Capillary protein leak syndrome appears to explain fluid retention in cancer patients who receive docetaxel treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang RY, Yoo KS, Han HJ, Lee JY, Lee SH, Kim DW, et al. Evaluation of the effects and adverse drug reactions of low-dose dexamethasone premedication with weekly docetaxel. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(2):429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto T, Rino Y, Adachi H, Fujii K, Saito S, Masuda M. Polymyositis and myocarditis after chemotherapy for advanced thymoma. Cancer Treatment Communications. 2013;1(1):9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasaki H, et al. Thymoma associated with fatal myocarditis and polymyositis in a 58-year-old man following treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2012;3(2): 300–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markman M, Kennedy A, Webster K, Kulp B, Peterson G, Belinson J. Paclitaxel administration to gynecologic cancer patients with major cardiac risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(11):3483–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taxol Administration Guide B.M.S. Company, Editor. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piccart MJ, Klijn J, Paridaens R, Nooij M, Mauriac L, Coleman R, et al. Corticosteroids significantly delay the onset of docetaxel-induced fluid retention: final results of a randomized study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Investigational Drug Branch for Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(9):3149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chouhan JD, Herrington JD. Single premedication dose of dexamethasone 20 mg IV before docetaxel administration. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2011;17(3):155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimoyama M, Murata Y, Sumi KI, Hamazoe R, Komuro I. Docetaxel induced cardiotoxicity. Heart. 2001;86(2):219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sparano JA. Use of dexrazoxane and other strategies to prevent cardiomyopathy associated with doxorubicin-taxane combinations. Semin Oncol 1998;25(4 Suppl 10):66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, Edgerton JR, Ellenbogen KA, Gold MR, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients with Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2019;140(8):e382–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.•.Ky B, et al. , Early increases in multiple biomarkers predict subsequent cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with doxorubicin, taxanes, and trastuzumab. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2014. 63(8): p. 809–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Biomarkers, in particular ultrasensitive troponin I and myeloperoxidase, show promise in detecting potential risk for, or the development of, cardiothoxicity in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

- 55.Curigliano G, Lenihan D, Fradley M, Ganatra S, Barac A, Blaes A, et al. Management of cardiac disease in cancer patients throughout oncological treatment: ESMO consensus recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(2):171–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hadi HAR, Carr CS, Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):183–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunadian V, et al. , An EAPCI expert consensus document on ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries in collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. European Heart Journal, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]