Abstract

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels are voltage-independent and are activated by Ca2+ binding to the calmodulin constitutively associated with the channels. Both the pore-forming subunits and the associated calmodulin are subject to phosphorylation. Here, we investigated the modulation of different SK channel subtypes by phosphorylation, using the cultured endothelial cells as a tool. We report that casein kinase 2 (CK2) negatively modulates the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK1 and IK channel subtypes by more than 5-fold, whereas the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes is only reduced by ~2-fold, when heterologously expressed on the plasma membrane of cultured endothelial cells. The SK2 channel subtype exhibits limited cell surface expression in these cells, partly as a result of the phosphorylation of its C-terminus by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). SK2 channels expressed on the ER and mitochondria membranes may protect against cell death. This work reveals the subtype-specific modulation of the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity and subcellular localization of SK channels by phosphorylation in cultured endothelial cells.

Introduction

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels are a unique group of K+ ion channels1, activated exclusively by intracellular Ca2+ 1–4. Calmodulin (CaM) is constitutively associated with SK channels and serves as the Ca2+ sensor of the SK-CaM complex1. There are four subtypes in the SK channel family encoded by the KCNN mammalian genes, including KCNN1 for SK1 (KCa2.1), KCNN2 for SK2 (KCa2.2), KCNN3 for SK3 (KCa2.3) and KCNN4 for IK (KCa3.1 or SK4) channels. SK channels play an important role in the vasculature5–9 and the central nervous system2. In neurons, SK channels expressed on the neuronal cell surface contribute to the medium after hyperpolarization (mAHP) and regulate the firing frequency of neurons2,10. SK channels were also reported to express on the intracellular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and play a protective role against cell death in human dopaminergic neurons11 and immortalized mouse hippocampal-derived HT-22 cells12. SK channels were also identified in mitochondria of neurons13 and cardiomyocytes14 where they exert protective roles.

In blood vessels, SK channels are expressed in endothelial cells15. It is well documented that the activation of SK channels expressed on the endothelial cell surface can reduce vascular tone. The cell surface expression of these channels is especially important in vasodilation mediated by endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization (EDH)16–18. Using transgenic SK3 mice, it was found that expression of SK3 channels modulates arterial tone and blood pressure5. Genetic deficit of both SK3 and IK channels in mice abolishes the EDH response and causes hypertension19. Compromised SK channel activity may be a contributing factor to hypertension7. In contrast to the enormous body of research on the role of cell surface SK channels in vasodilation, it is not clear whether any SK channel subtypes are expressed on the ER and mitochondria membranes in endothelial cells and whether they can protect endothelial cells from apoptosis.

In neurons, casein kinase 2 (CK2) phosphorylates the CaM complexed with the SK2 channel and leads to decreased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity20–23, whereas cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) mediates phosphorylation at the C-terminus of SK2 channels and reduces their cell surface expression24–26. A CK2 inhibitor 4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-2-azabenzotriazole (TBB) increased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK2 channels22, while a PKA inhibitor (H89) improved surface expression of SK2 channels24. But it is not clear if these kinases regulate the other SK channel subtypes differently. In vascular endothelial cells, even less is known. We therefore investigated the modulation of different SK channel subtypes utilizing the cultured endothelial cells as a tool. In previous studies, SK3 and IK channel subtype expression has been readily detected through reverse transcriptase PCR and then confirmed through electrophysiology and pharmacological experiments in vascular endothelial cells from humans, pigs and cattle27–33. In contrast, expression of SK1 channels in isolated and cultured endothelial cells was rarely detected33. Most interestingly, the mRNA of SK2 channels was readily detectable31–33, but functional SK2 channel current on the plasma membrane was rarely identifiable in isolated and cultured endothelial cells33.

Here, we took advantage of an immortalized mouse aorta endothelial cell line that we established and characterized previously34–36, to study the modulation of different SK channel subtypes by phosphorylation34–36. The objective is to compare the modulation of different subtypes by phosphorylation, utilizing the cultured endothelial cells as a tool. We found that the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK1 and IK channel subtypes is more strongly negatively modulated than that of the SK3 and SK2, presumably through phosphorylation of CaM by CK2. On the other hand, the cell surface expression of SK2 channel subtype is very limited, partly as a result of phosphorylation at its C-terminus by PKA. SK2 channels express on the ER and mitochondria membranes, which may be associated with its protective role against palmitate-mediated cell death.

Results

Modulation of SK channels’ apparent Ca2+ sensitivity by CK2 phosphorylation.

We first compared apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channels in HEK293 and cultured endothelial cells. SK channels were heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells for inside-out patch-clamp experiments to determine apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of these channels as we previously reported20,37–40. To investigate the differential modulation of SK channel subtypes, we utilized an immortalized mouse aorta endothelial cell line that we previously established and characterized34–36. Exposing the inside-out patches of the non-transfected cultured endothelial cells to 10 μM Ca2+ could not induce any changes in current compared to nominal 0 Ca2+, suggesting that the endogenous Ca2+-activated channel current in this cultured endothelial cell line is too small to be detected in inside-out patches (Fig. S1). We then transfected cultured endothelial cells with SK channel subtype cDNAs and stable clones were obtained through selection by puromycin and enrichment using repeated GFP fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The same electrophysiology method used for HEK293 cells was utilized to measure apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the SK channel subtypes in cultured endothelial cells (Fig. S2). The leak recorded at nominal 0 Ca2+ was subtracted from SK channel currents recorded at various Ca2+ concentrations, before Ca2+ concentration-response curves were constructed.

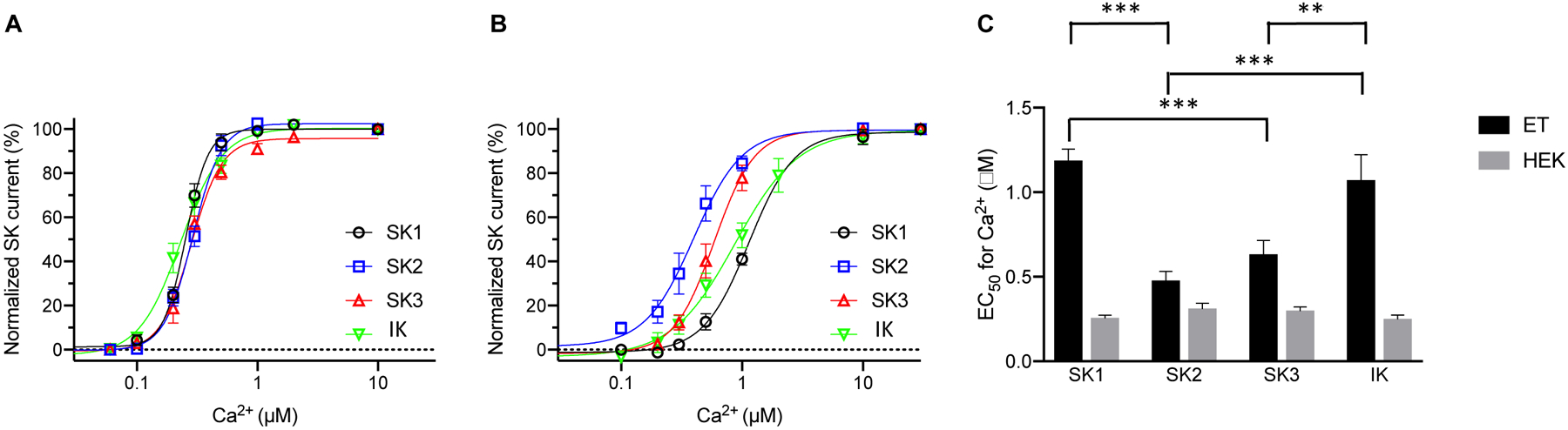

Surprisingly, all SK channel subtypes exhibited significantly lower apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in cultured endothelial cells than in HEK293 cells. The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channel subtypes expressed in HEK293 cells seems comparable to each other (Fig. 1A), whereas SK channel subtypes expressed in cultured endothelial cells exhibit larger differences in their apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 1B). Among the four SK channel subtypes heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells, there is no statistically significant difference between their EC50 values to Ca2+. However, the SK1 channel exhibits significantly greater EC50 value for Ca2+ than SK2 (P < 0.0001) and SK3 (P = 0.0006) channel subtypes, when expressed in cultured endothelial cells. The IK channel also exhibits a lower apparent Ca2+ sensitivity than SK2 (P < 0.0001) and SK3 (P = 0.0058) channel subtypes in cultured endothelial cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK1 and IK channel subtypes is more decreased than that of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes in immortalized endothelial cells.

Concentration-dependent activation by Ca2+ of the SK channel subtypes heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells (A) and immortalized endothelial cells (B). (C) EC50 values for the activation by Ca2+, recorded from SK channel subtypes expressed in HEK293 cells (HEK) and immortalized endothelial cells (ET). All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M (n = 6–11, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests).

The SK1 channel subtype expressed in cultured endothelial cells showed a 4.6-fold lower apparent Ca2+ sensitivity than the same subtype expressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. S3A). The EC50 value for Ca2+ to activate SK1 channels in cultured endothelial cells (1.19 ± 0.068 μM, n = 8) was ~4.6-fold greater than in HEK293 cells (0.26 ± 0.017 μM, n = 6, P = 0.00000007). For the SK2 channel subtype, only a 1.5-fold difference in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity was found between channels expressed in cultured endothelial cells (EC50 = 0.48 ± 0.044 μM; n = 9) and those in HEK293 cells (EC50 = 0.31 ± 0.020 μM; n = 6, P = 0.039) (Fig. S3B). For the SK3 channel, a 2.1-fold difference was found between SK3 channels expressed in cultured endothelial cells (EC50 = 0.63 ± 0.08 μM; n = 8), and those in HEK293 cells (EC50 = 0.30 ± 0.024 μM; n = 6, P = 0.001) (Fig. S3C). For IK channels, an ~5-fold difference was found between IK channels expressed in cultured endothelial cells (EC50 = 1.07 ± 0.25 μM; n = 11) and those in HEK293 cells (EC50 = 0.25 ± 0.023 μM; n = 10, P = 0.00001) (Fig. S3D). Thus, every SK channel subtype exhibits a reduced apparent Ca2+ sensitivity when expressed in cultured endothelial cells compared to HEK293 cells. In addition, the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK1 and IK channel subtypes is more negatively modulated than that of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes in cultured endothelial cells.

We postulate that the reduced apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channels in cultured endothelial cells is caused by post-translational modification. In neurons, CK2 phosphorylates CaM, which is constitutively associated with the SK2 channel and therefore decreases its apparent Ca2+ sensitivity20–22. To test whether CK2 is also responsible for decreased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channels in cultured endothelial cells, we utilized the CK2 inhibitor TBB (Millipore-Sigma), a cell-permeable CK2 inhibitor previously used in the studies of CK2 regulation of SK2 channels22. In our excised inside-out patches, the intracellular kinases can no longer access the SK channels on the membrane, whereas CK2 is co-assembled with the channels21. The IC50 of TBB on rodent CK2 is about 0.9 μM41. For complete inhibition of CK2 co-assembled with the channels, cells were incubated with TBB (10 μM) in the bath solution before and during the electrophysiological recordings (Fig. S4). The treatment with TBB drastically enhanced apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the SK1 channel in cultured endothelial cells by ~5.4 fold from 1.19 ± 0.068 μM (n = 8) to 0.22 ± 0.023 μM (n = 6; P = 0.00000005; Fig. S5A). The effect of TBB on the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the SK2 channel is only slightly more than 2-fold, from 0.48 ± 0.044 μM (n = 9) to 0.22 ± 0.020 μM (n = 6, P = 0.004; Fig. S5B). TBB increased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the SK3 channel by ~2.6-fold from 0.63 ± 0.08 μM (n = 8) to 0.24 ± 0.0099 μM (n = 8, P = 0.0003; Fig. S5C). The effect of TBB on the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the IK channel is ~8-fold, changing from 1.07 ± 0.25 μM (n = 11) to 0.13 ± 0.029 μM (n = 8, P = 0.00006; Fig. S5D). Hence, every channel subtype exhibits an increased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in the presence of TBB. CK2 is the kinase that causes post-translational modification of the SK channel complexed with CaM and negatively modulates their apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in cultured endothelial cells.

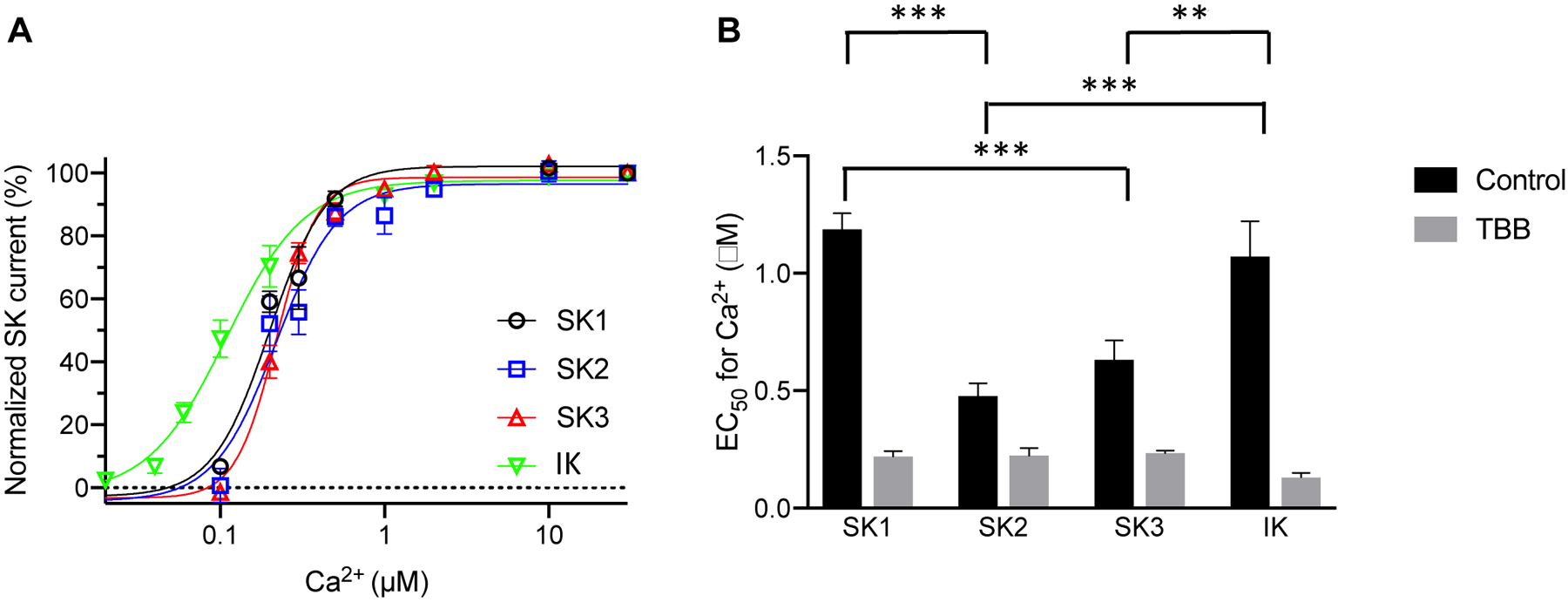

Even though the SK channel subtypes expressed in cultured endothelial cells exhibit diverse apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 1B), their Ca2+-dependent activation curves are very similar to each other in the presence of TBB (Fig. 2A). When compared among the channel subtypes, the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the four channel subtypes are comparable to each other in the presence of TBB (Fig. 2B). TBB abolished the statistically significant difference between apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channel subtypes in cultured endothelial cells. With a structurally unrelated and more potent CK2 inhibitor, CX4945 (silmitasertib, 5-[(3-chlorophenyl)amino]-benzo[c]-2,6-naphthyridine-8-carboxylic acid)42, we were able to obtain similar results on the SK channel subtypes (Fig. S6). In the presence of CX4945 (Cayman Chemicals), the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the four channel subtypes are similar to each other (Fig. S6). These results indicate that CK2 negatively modulates apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK1 and IK channel subtypes more than the SK3 and SK2 subtypes.

Fig. 2. The CK2 inhibitor TBB abolishes the differences between apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channel subtypes in cultured endothelial cells.

(A) Concentration-dependent activation by Ca2+ of the SK channel subtypes heterologously expressed in immortalized endothelial cells in the presence of TBB (10 μM). (B) EC50 values for the activation by Ca2+, recorded from SK channel subtypes expressed in the immortalized endothelial cells, in the absence (Control) and presence (TBB) of TBB. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M (n = 6–9, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests).

Expression of SK2 channels on intracellular membranes.

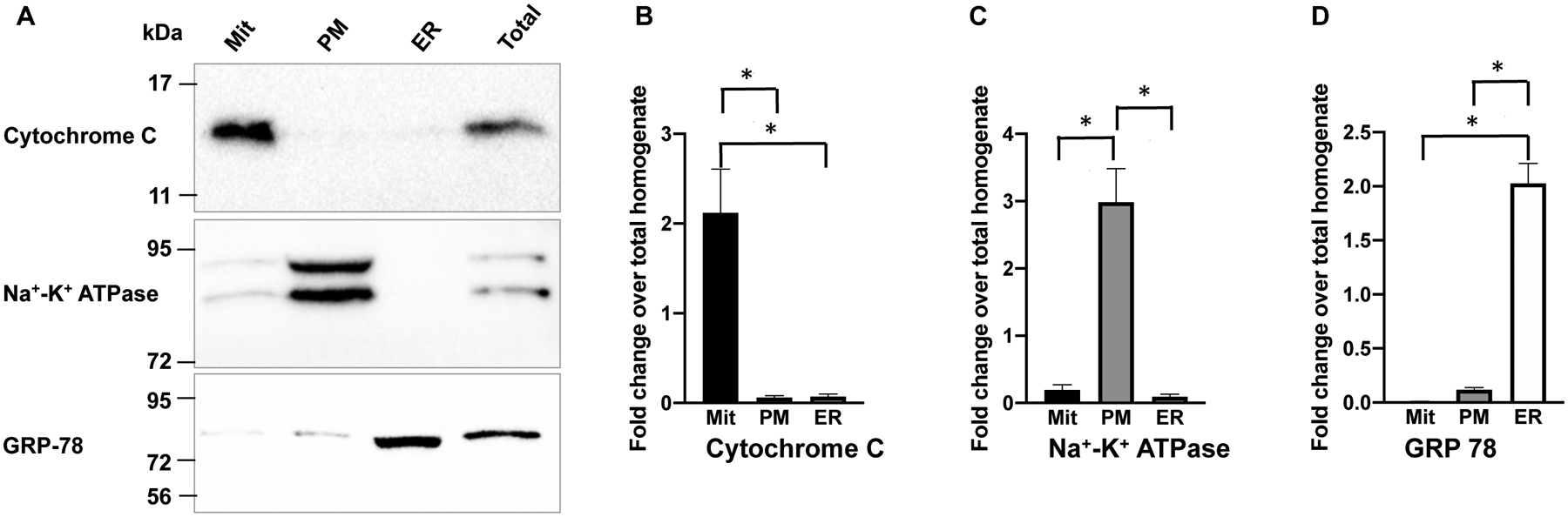

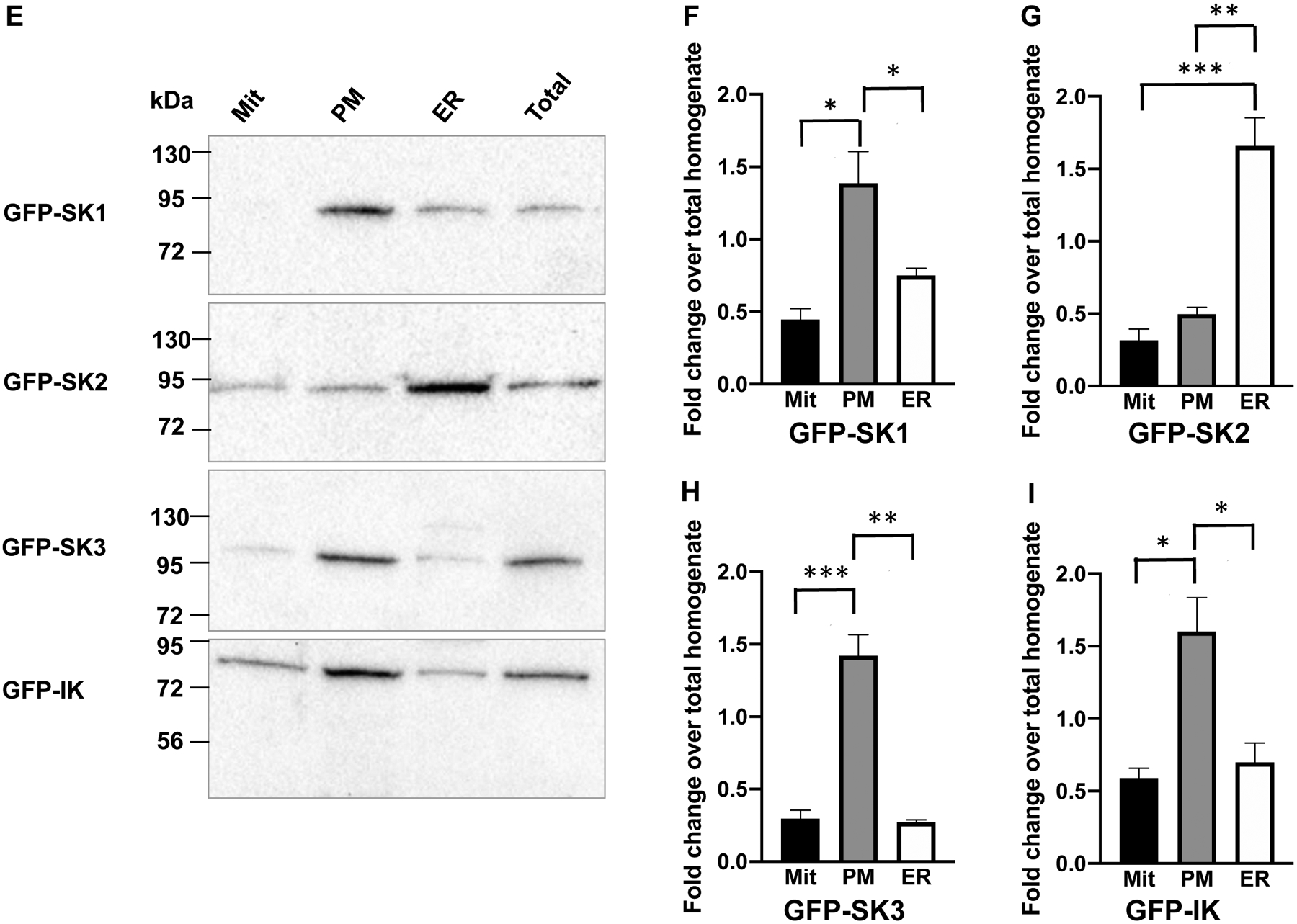

In immortalized mouse hippocampal-derived HT-22 cells, SK channels were found to express on the intracellular ER12 and mitochondria13 membranes. In cultured endothelial cells, SK channels on the intracellular membranes remain unexplored. Our stably-transfected cell lines express SK channel subtypes as fusion proteins with green fluorescent protein (GFP). We further transfected the cells with cDNAs of the ER membrane targeted red fluorescence protein (DsRed2-ER)43. We examined the colocalization of the GFP-tagged SK1 (Fig. S7A), SK2 (Fig. S7B), SK3 (Fig. S7C) and IK (Fig. S7D) with DsRed2-ER. In order to compare the levels of co-localization between DsRed-ER and different SK channel subtypes, histograms were made using the grey values measured for the area indicated by the white arrows (Fig. S7A–D). We further calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients from multiple histograms of each channel subtype (Fig. S7E). The SK2 channel subtype has a significantly greater correlation coefficient (0.79 ± 0.055, n = 7) compared with other channel subtypes (Fig. 3E), suggesting a higher level of co-localization with DsRed2-ER. Certainly, a Pearson correlation coefficient of ~0.79 does not mean exclusive expression of SK2 channels on the ER membrane. We then performed cell fractionation of the stable cell lines of SK channel subtypes and prepared mitochondria (Mit), plasma membrane (PM) and ER fractions using the same technique that we previously described44,45. Immunoblots for markers of the mitochondria (Cytochrome C), plasma membrane (Na+-K+ ATPase) and the ER (GRP-78) were performed (Fig. 3A). Densitometry with ImageJ program of the immunoblots indicates distribution of Cytochrome C in the mitochondria (Fig. 3B), Na+-K+ ATPase on the plasma membrane (Fig. 3C) and GRP-78 in the microsome (Fig. 3D). Anti-GFP antibodies were used to detect the SK channel subtypes in the fractions (Fig. 3E). All four channel subtypes were found on the plasma membrane and the intracellular membranes (Fig. 3F–I). Noticeably, the SK2 channel subtype is expressed abundantly on the ER membrane, even though SK2 channels were also detected on plasma membrane and mitochondria (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3. Subcellular localization of the SK channel subtypes in immortalized endothelial cells.

(A) Cell fractions were verified by immunoblots with antibodies for mitochondria marker (Cytochrome C), ER marker (GRP-78) and plasma membrane marker (Na+-K+ ATPase). In (B), (C) and (D), densitometry results for the subcellular markers are summarized from 3–4 experiments. (E) In cell fractions, the SK2 channel subtype is abundantly expressed on the ER membrane, in contrast to other channel subtypes. In (F), (G), (H) and (I), densitometry results for the SK channel subtypes are summarized from 4–6 experiments. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests.

To detect the endogenous SK channel subtypes in the cultured endothelial cells, non-transfected cells were fractionated and then subjected to immunoblots with specific antibody for each SK channel subtypes. Endogenous SK3 channels were the only channel subtype detected in this particular endothelial cell line, with more prominent expression of SK3 channels on the plasma membrane than the mitochondria and ER (Fig. S8A,B), which is similar to the results of heterologously expressed SK3 channels (Fig. 3). Other channel subtypes were not detected in this cell line (Fig. S8C).

Role of SK2 channels on the intracellular membranes.

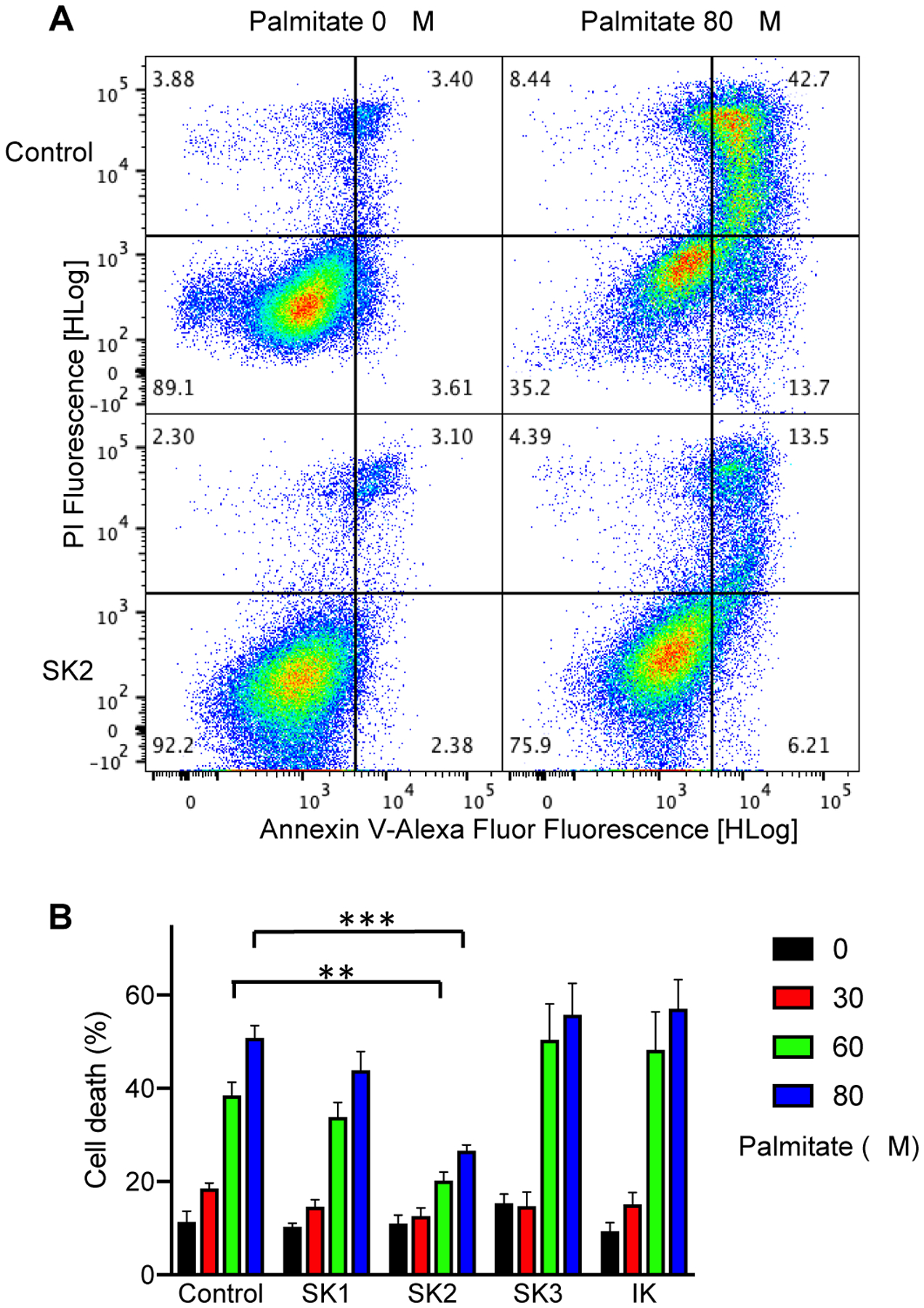

Our results show that the SK2 channel subtype is abundantly expressed in the ER fraction and to a lesser extent in the mitochondrial fraction of cultured endothelial cells (Fig. 3). Because the SK channel expression on the ER and mitochondria membranes may be linked with protection against apoptosis mediated by ER stress12 and reactive oxygen species13,14, we challenged cultured endothelial cell lines stably expressing the different SK channel subtypes with palmitate-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4). Palmitate induces cell death through a pathway related to ER stress and oxidative stress46. Compared to the control parent cell line, no protective effect against palmitate-induced cell death was seen for the SK1, SK3 and IK channels. However, a significant protective effect was found for the SK2 channel (Fig. 4A). The heterologous expression of SK2 channels significantly reduced 60 μM palmitate-mediated endothelial cell death from 38.5 ± 2.8 % (n = 5) to 20.2 ± 1.8 % (n = 5, P = 0.008). Cell death mediated by 80 μM palmitate decreased even more drastically from 50.8 ± 2.6 % (n = 5) to 26.6 ± 1.3 % (n = 5, P = 0.0002) as a result of SK2 channel heterologous expression (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. The SK2 channel subtype protects the immortalized endothelial cells against apoptosis induced by palmitate.

(A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of non-treated cells and cells treated with 80 μM palmitate using double staining with Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 647/PI. Cells in the lower right quarter indicate AnnexinV-positive, early apoptotic cells. Cells in the upper right quarter indicate AnnexinV-positive/PI-positive, late apoptotic cells. (B) Quantification of cell death (the total of early and late apoptotic cells) after 24 h treatment with palmitate (mean ± S.E.M, n = 5; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with control parent cells, Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests).

Phosphorylation of SK2 channels.

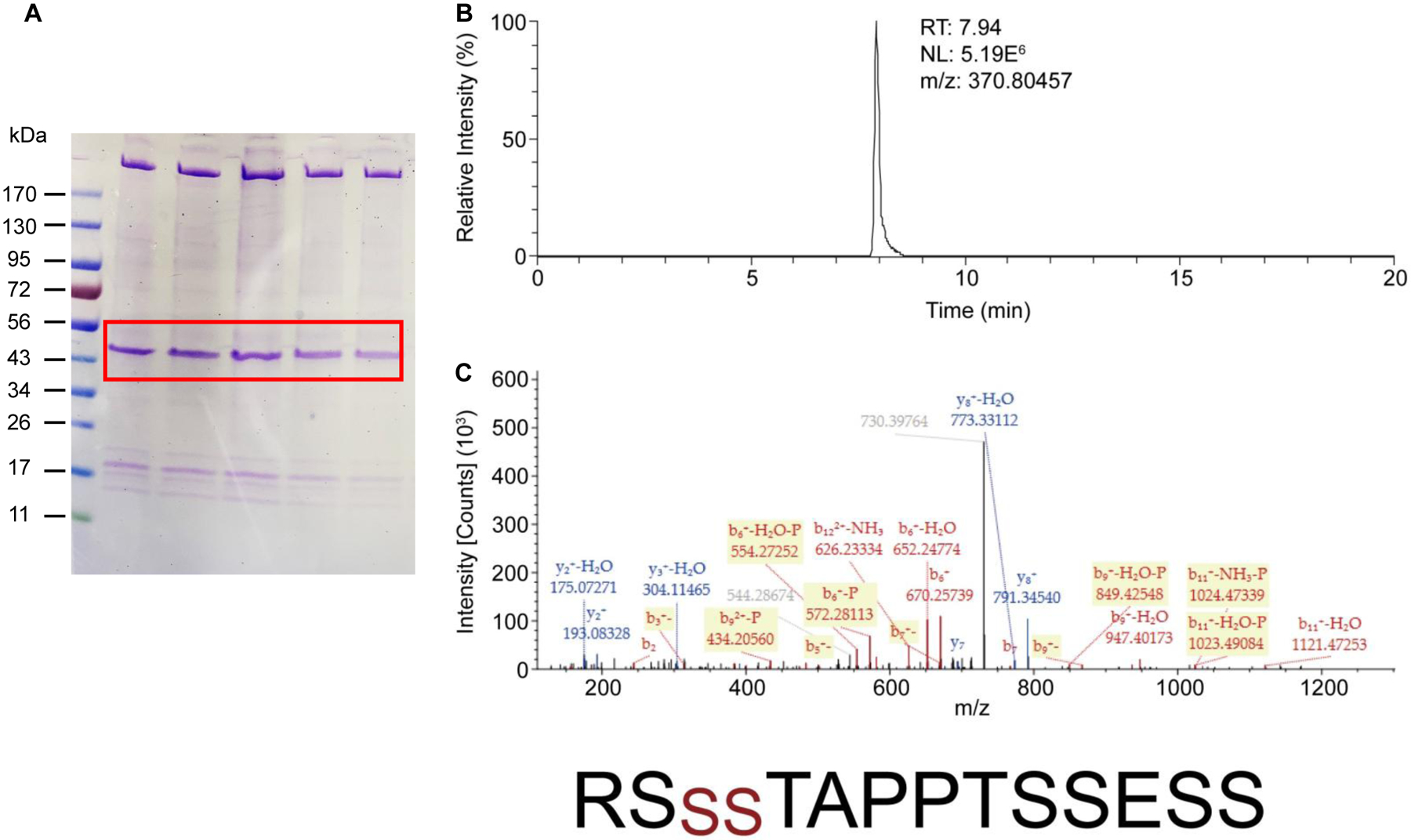

In cultured endothelial cells, the SK2 channel subtype seems to show less plasma membrane expression (Fig. 3). PKA phosphorylates the C-terminus of the SK2 channel24 and reduces its cell surface expression in neurons25,26. We isolated the SK2 channel protein from the plasma membrane of the cultured endothelial cells stably expressing SK2 channels through immunoprecipitation using GFP‐Trap_A beads (Chromotek). SK2 channel proteins were cleaved off the GFP tag from the immunoprecipitants and then separated on SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 5A). Protein bands at >170 kDa and ~50 kDa were both identified as SK2 channels by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) detection. The protein bands at >170 kDa might be the high molecular weight complex of SK2 channels47. A protein band at ~17 kDa was identified as CaM (Fig. S9 and Table S1). No prominent phosphorylation of CaM at T79 was found in the peptide corresponding to CaM residues 76MKDTDSEEEIR86 detected by LC-MS/MS. Instead, LC-MS/MS revealed that phosphate groups were associated with a peptide corresponding to SK2 channel residues 567RSSSTAPPTSSESS580 (Fig. 5B,C). Phosphorylation of residues S569 and S570 was identified. In contrast to the significantly higher expression of WT SK2 channels on the ER membrane than on the plasma membrane (Fig. 3G), the alanine mutations of the three adjacent serine residues S568, S569 and S570 (SK2-AAA) increased the expression of the mutant SK2 channels on the plasma membrane to a level comparable to their expression on the ER membrane (Fig. S10).

Fig. 5. Nano-LC/MS/MS analyses of SK2 protein isolated from the plasma membrane of the immortalized endothelial cells.

(A). The endothelial cells expressing SK2 channels were subjected to cell fractionation. SK2 channel proteins were purified from the plasma membrane fraction and then separated on SDS-PAGE gel. Protein bands at ~50 kDa and ~17 kDa correspond to SK2 channels (labeled in red box) and calmodulin, respectively. (B). The extracted ion-chromatograms of the peptide “567RSSSTAPPTSSESS580” of SK2 channels (doubly charged ion at m/z 370.80457). (C). The tandem mass spectrum of the peptide was acquired from the doubly charged precursor ion at m/z 370.80457. Fragment ion peaks as b- or y-type ions are also labeled in the spectrum. The peptide sequence including the phosphorylated sites at serines (red color) is indicated at the bottom.

Discussion

SK channels are a unique group of potassium channels that are activated exclusively by CaM when it is bound with Ca2+ 48. These channels play an important role in the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system. The pore-forming subunits and the associated CaM are subject to phosphorylation by PKA24–26 and CK220–23, respectively (Fig. 6). Here, we utilize an immortalized mouse aorta endothelial cell line to study the differential phosphorylation of SK channel subtypes. We report that SK channel subtypes are differentially modulated by phosphorylation when heterologously expressed in cultured endothelial cells. The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK1 and IK channel subtypes is more strongly decreased than that of the SK3 and SK2 subtypes by CK2 phosphorylation, when expressed on the plasma membrane of cultured endothelial cells (Fig. 2). In addition, the SK2 channel subtype expresses on the intracellular membranes (Fig. 3) and protects cultured endothelial cells against cell death (Fig. 4).

Fig. 6. SK channels are phosphorylated by kinases.

CK2 phosphorylates the CaM in complex with SK channels and leads to reduced apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. PKA phosphorylates the C-terminus of SK2 channels and reduces its cell surface expression. Counter-regulatory phosphatases are not shown for the purpose of clarity.

In endothelial cells, the basal intracellular free Ca2+ concentration is estimated to be lower than 0.1 μM49. Ca2+ release from the ER50 and Ca2+ influx through calcium-permeable channels9 triggers local Ca2+ signals to activate SK channels in cultured endothelial cells. The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the SK channels will require fine-tuning for precise intracellular signaling towards EDH-mediated vasodilation. Phosphorylation at threonine79 (T79) of CaM complexed with SK channels inhibits the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channels21. When expressed in HEK293, all four channel subtypes exhibited EC50 values for Ca2+ in a narrow range from 0.25 to 0.31 μM (Fig. 1C), presumably because of low phosphorylation levels by CK2 in HEK293 cells. Thus, HEK293 cells may not be an ideal cell line to study the phosphorylation of SK-CaM complex. When expressed in cultured endothelial cells, the channel subtypes exhibited very diverse EC50 values for Ca2+ from 0.48 to 1.19 μM (Fig. 1C). This diversity in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channel subtypes is caused by different levels of CK2 phosphorylation, as the CK2 inhibitors TBB and CX4945 completely abolished the diversity in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity among the subtypes (Fig. 2 and Fig. S6). In neurons, cell signaling pathways of neurotransmitters can influence the phosphorylation of the SK-CaM complex by CK251,52. The cell signaling pathways regulating the phosphorylation by CK2 and dephosphorylation by PP2A in endothelial cells are still unclear. Nonetheless, our results definitively indicate that differences exist in the modulation of apparent Ca2+ sensitivity among the SK channel subtypes in cultured endothelial cells.

Among the SK channel subtypes, the SK2 channel is the most sensitive to apamin, a bee venom toxin, with an IC50 of ~70 pM53–55. The SK3 channel is less sensitive to apamin with an IC50 of ~10 nM56,57. The SK channel current on the cell surface of endothelial cells is typically comprised of a charybdotoxin-sensitive IK component and an apamin-sensitive component27–33. Usually it requires apamin at nM levels to inhibit this apamin-sensitive component, suggesting its molecular identity as predominantly the SK3 channel subtype. It is puzzling that the mRNA of SK2 channels was readily detectable in isolated and cultured endothelial cells31–33, whereas functional SK2 channel current on the plasma membrane was rarely identified. What is limiting the expression of SK2 channels on the endothelial cell surface? PKA phosphorylates the C-terminus of the SK2 channel24. In lateral amygdala pyramidal neurons, β-adrenoceptor activation regulates synaptic SK2 channel expression on the dendrites, through activation of PKA25. In mouse hippocampus, long-term potentiation (LTP) induction activates PKA and causes SK2 channel internalization26. Tonic PKA activity is also involved in the enrichment of SK channels on the dendrites compared to the soma of cultured hippocampal neurons58,59. PKA phosphorylation of a serine residue (S465) in the CaM binding domain may also underlie the functional recruitment of dormant SK2 channels in ventricular myocytes60. Our mass spectrometry studies show that the SK2 channel protein isolated from the plasma membrane of cultured endothelial cells undergoes prominent phosphorylation in its C-terminus, more specifically at amino acid residues S569 and S570 (Fig. 5). In a previous study, mass spectrometry detected phosphorylation of the same serine residues from purified channel C-terminus fragment treated with PKA catalytic subunit24. Mutations of these serine residues prevented the decrease in cell surface expression of SK2 channels caused by PKA stimulation in COS7 cells24. The phosphorylation might also be one of the causes of the limited plasma membrane expression of SK2 channels in cultured endothelial cells, as mutations of these residues to alanine increased the expression of SK2 channels on the plasma membrane to a level comparable to their ER expression (Fig. S10). Different from the previous mass spectrometry studies24, our mass spectrometry experiments were performed from isolated full-length SK2 channel protein without any artificial kinase treatment, suggesting naturally occurring phosphorylation.

The SK2 channel expression on the cell surface is very limited (Fig. 3). Where are SK2 channels expressed in cultured endothelial cells? Our results suggest the expression of SK2 channels on the ER and mitochondria membranes (Fig. 3). The SK2 channels expressed on these intracellular membranes are associated with a protective role against cell death in immortalized mouse hippocampal-derived HT-22 cells12,13 and cardiomyocytes14. Our results revealed a protective role of SK2 channels against the palmitate-mediated endothelial cell death (Fig. 4), echoing their expression on the intracellular membranes (Fig. 3).

The objective of this report is to compare the modulation of different SK channel subtypes by phosphorylation. Our studies were performed with immortalized mouse aorta endothelial cells, which limits the application of the findings reported here only to the cells examined. Our findings here revealed that the modulation of the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity and subcellular localization by phosphorylation is channel subtype specific. In addition to studies on the SK channels, research focusing on the subtype-specific modulations of these channels by kinases and phosphatases will be needed in future studies of endothelial cells. Given the roles of SK3 and IK channels in the EDH-mediated vasodilatory response16,61,62 and the protection by SK2 channels against endothelial cell death which we just reported (Fig. 4), there is no doubt about the importance of the SK channels in the vasculature. Pharmacological interventions targeted at SK channels might lead to promising strategies not only to relax vessels and reduce blood pressure63 but also to protect the vascular endothelium.

Methods

Cultured endothelial cells

We utilized an immortalized mouse aorta endothelial cell line that we previously established and characterized, as a tool to study the differential modulation of SK channel subtypes. The generation and characterization of this immortalized cell line are descibed as follows.

Cell line generation:

When we first planned to generate a mouse endothelial cell line, our strategy was to allow these cells to behave like primary cells isolated from an intact artery as much as possible35. The approach was to use transgenic C57BL/6J-Tg(SV)7Bri/J mouse with a regulatable Simian Virus-40 gene to propagate the cell line. Cell line propagation occurred when we turned on the gene with temperature at 33°C and chemical IFN-γ. When cells were grown at 37°C in the absence of IFN-γ, they would behave like primary cells. Our cell line can differentiate to retain markers seen in the intact arteries. These endothelial markers include Pecam-1 (CD31), VE-cadherin (CD144), N-cadherin (CD325), eNOS, Klf2, and Klf434–36. In addition to shear-induced nitric oxide production and release, functional characteristics of our endothelial cells were equivalent to an intact artery include cell migration (wound healing), functional tight junction and shear-induced activation of Tgfβ/Alk5 signaling34,36,64.

Stable expression of SK channel subtypes

We first established stable cell lines of the SK channel subtypes. The SK channel subtype cDNAs were constructed by custom cloning services of Genscript Inc. as fusion proteins with the GFP at the N-termini in the pIRES-puro3 vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). The cultured endothelial cells were transfected with SK channel subtypes plasmids using a LipofectamineⓇ 3000 Transfection Kit (Invitrogen). Stable clones were obtained through selection by puromycin and enrichment using repeated GFP fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The cells were cultured at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin and puromycin. Microscopy images of cells were acquired using a Nikon Confocal Laser Microscope and analyzed with NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon instruments Inc).

Electrophysiology

The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of SK channels was investigated as previously described20,37,38. For experiments with HEK293 cells, channel activities were recorded 1–2 days after transfection with channel cDNAs, using an inside-out patch configuration. For the non-transfected cultured endothelial cells, the inside-out patches did not exhibit any induced current to 10 μM Ca2+, compared to nominal 0 Ca2+. For experiments with cultured endothelial cells stably expressing SK channel subtypes, channel activities were measured 1–2 days after seeding, using an inside-out patch configuration with an Axon200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) at room temperature.

pClamp 10.5 (Molecular Devices) was used for data acquisition and analysis. The resistance of the patch electrodes ranged from 3–4.5 MΩ. The extracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 10 Hepes (pH 7.4), 1 MgSO4. The bath solution containing (in mM): 140 KCl, 10 Hepes (pH 7.2), 1 EGTA, 0.1 Dibromo-BAPTA, and 1 HEDTA was mixed with Ca2+ to obtain the desired free Ca2+ concentrations, calculated using the software by Chris Patton of Stanford University ((https://somapp.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pharmacology/bers/maxchelator/webmaxc/webmaxcS.htm). The Ca2+ concentrations were verified using a Ca2+ calibration buffer kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, a standard curve was generated using the Ca2+ buffers from the kit and a fluorescence Ca2+ indicator. Then the Ca2+ concentrations of our bath solutions were determined through interpolation on the standard curve.

Currents were recorded using an inside-out patch configuration. Currents were recorded when the intracellular side of the patch was exposed to different free Ca2+ concentrations (0 – 30 μM). Currents were recorded by repetitive 1-s-voltage ramps from − 100 mV to + 100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. One minute after switching of bath solutions, ten sweeps with a 1-s interval were recorded. The integrity of the patch was examined by switching the bath solution back to the zero-Ca2+ buffer. As such, the recorded currents came from Ca2+ sensitive channels, rather than leak of the patch. Data from patches, which did not show significant changes in the seal resistance after solution changes, were used for further analysis. To construct the dose-dependent activation of channel activities, the current amplitudes at − 90 mV in response to various concentrations of Ca2+ were normalized to that obtained at maximal concentration of Ca2+. The normalized currents were plotted as a function of the concentrations of Ca2+. EC50 values and Hill coefficients were determined by fitting the data points to a standard concentration–response curve (Y = 100/(1 + (X/EC50)^ − Hill)). All data are presented in mean ± s.e.m. The data analysis was performed using pClamp 10.5 (Molecular Devices) in a blinded fashion.

Cell fractionation

We performed cell fractionation of the non-transfected cultured endothelial cells and cells stably expressing the SK channel subtypes to investigate the subcellular localization, using the technique previously described12,45. Briefly, confluent cultured endothelial cells from 30 dishes (100 mm) were harvested. The cell pellet was resuspended and homogenized in a buffer containing 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose and 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) supplemented with mass spectrometry-compatible phosphatase inhibitor and protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The homogenate was centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 minutes to remove unbroken cells and nuclei. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 10000 × g for 10 minutes to pellet the mitochondria. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 25000 × g for 20 minutes to pellet the plasma membrane. For separation of microsomes (vesicles reformed from the ER membrane) and cytosolic proteins the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 95000 × g for 2.5 hours. The concentrations of plasma membrane and ER fractions were determined by BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (15 ug) were separated by SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad). The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with primary GFP antibody (1:2000; Invitrogen, Lot: 2015993), SK1 antibody (1:1000; RayBiotech, Lot: 907002018), SK2 antibody (1:200; Alomone Labs, Lot: APC028AN2325), SK3 antibody (1:200; Alomone Labs, Lot: APC025AN1125), IK antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz, Lot: I2319), mitochondria marker Cytochrome C antibody (1:1000; Novus Biologicals, Lot: AB0115109A-2), ER marker GRP78/HSPA5 (1:4000; Novus Biologicals, Lot: H-1) antibody or plasma membrane marker sodium potassium ATPase alpha 1 (1:4000; Novus Biologicals, Lot: B-5) antibody. The PVDF membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with anti-rabbit (1:3000; Cell signaling technology) or anti-mouse (1:2000; Cell signaling technology) as secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature and then washed with TBST. The chemiluminescent signals were detected on a ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) after incubation with Luminol/Enhancer Solution (Thermo Scientific).

Isolation of SK2 channel proteins and LC-MS/MS analysis

The SK2 channel in complex with CaM was isolated from the plasma membrane prepared from cell fractionation described above. Briefly, the pellets were solubilized in extraction buffer (20 mM n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM), 4 mM cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS), 300 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM Tris pH 8, supplemented with mass spectrometry-compatible phosphatase inhibitor and protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific)) for 1.5 hours. The binding between CaM and the SK channels is strong enough to be purified as a protein complex with these detergents4. Solubilized membranes were clarified by centrifugation and immunoprecipitated using GFP‐Trap_A beads (Chromotek). The beads were washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer (0.5 mM DDM, 0.1 mM CHS, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM Tris pH 8), before the channel proteins were cleaved off the immunoprecipitates, separated on SDS-PAGE gels and stained with Coomassie blue. In-gel digestion of the protein bands was performed using sequence-grade trypsin and then subjected to LC-MS/MS. The digested peptide mixtures were analyzed by nanospray LC-MS/MS on an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an EASY-nano-LC System (Thermo Scientific) with a preferred OT-HCD-OT workflow. All data processing was performed in Proteome Discoverer 2.2 (PD) (Thermo Scientific) using the SEQUEST search engine with a FDR <0.01 at peptide and protein levels.

Cell death assay

One day after seeding, cultured endothelial cells were treated with a series of palmitate concentrations for 24 hours. Palmitate causes protein misfolding in the ER and activates the unfolded protein response and eventually ER stress. The cells were harvested and the apoptotic cell death was measured with the Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) double staining and flow cytometry, using a modified protocol that we previously reported45. Briefly, cells were incubated in binding buffer containing Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 647 and PI (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 20 minutes. Flow cytometric analysis was performed with excitation at 635 nm and emission at 660 nm for Annexin V, together with excitation at 535 nm and emission at 617 nm for PI using the FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were quantified as the sum of Annexin V and Annexin V/PI-positive cells. Data were collected from 10,000 cells per condition.

Statistical Analysis

Two-way ANOVA and post hoc tests were used for data comparison between channel subtypes and drug treatments. One-way ANOVA and post hoc tests were used for data comparison between data of more than three groups. The Student’s t-test was used for data comparison if there were only two groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to Adam Viegas, Misa Nguyen, Lisa Tran, Kimberly Diep, Michelle Le, Maria Akhnoukh and Judy Lee for technical assistance. M.Z. was support by an internal Faculty Opportunity Fund of Chapman University Office of Research and a Scientist Development Grant 13SDG16150007 from American Heart Association.

Abbreviations

- Ca2+

Calcium

- SK

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels

- mAHP

medium after hyperpolarization

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- EDH

endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization

- PKA

cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase

- CK2

casein kinase 2

- CaM

Calmodulin

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- DsRed2-ER

ER membrane targeted red fluorescence protein

- PM

plasma membrane

- LC-MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- HEK

HEK293 cells

- ET

immortalized endothelial cell culture

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Adelman JP, Maylie J & Sah P Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels: Form and function. Annu Rev Physiol 74, 245–269 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stocker M Ca2+-activated K+ channels: molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat Rev Neurosci 5, 758–770 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovalevskaya NV et al. Structural analysis of calmodulin binding to ion channels demonstrates the role of its plasticity in regulation. Pflugers Arch (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CH & MacKinnon R Activation mechanism of a human SK-calmodulin channel complex elucidated by cryo-EM structures. Science 360, 508–513 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor MS et al. Altered expression of small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK3) channels modulates arterial tone and blood pressure. Circ Res 93, 124–31 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng J et al. Calcium-activated potassium channels contribute to human coronary microvascular dysfunction after cardioplegic arrest. Circulation 118, S46–51 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garland CJ Compromised vascular endothelial cell SK(Ca) activity: a fundamental aspect of hypertension? Br J Pharmacol 160, 833–5 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagy N et al. Role of Ca(2)+-sensitive K+ currents in controlling ventricular repolarization: possible implications for future antiarrhytmic drug therapy. Curr Med Chem 18, 3622–39 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonkusare SK et al. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science 336, 597–601 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedarzani P et al. Specific Enhancement of SK Channel Activity Selectively Potentiates the Afterhyperpolarizing Current IAHP and Modulates the Firing Properties of Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons. J. Biol. Chem 280, 41404–41411 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolga AM et al. Subcellular expression and neuroprotective effects of SK channels in human dopaminergic neurons. Cell Death Dis 5, e999 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter M et al. Activation of SK2 channels preserves ER Ca(2)(+) homeostasis and protects against ER stress-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ 23, 814–27 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolga AM et al. Mitochondrial small conductance SK2 channels prevent glutamate-induced oxytosis and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Biol Chem 288, 10792–804 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TY et al. SK channel enhancers attenuate Ca2+-dependent arrhythmia in hypertrophic hearts by regulating mito-ROS-dependent oxidation and activity of RyR. Cardiovasc Res 113, 343–353 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wulff H & Kohler R Endothelial small-conductance and intermediate-conductance KCa channels: an update on their pharmacology and usefulness as cardiovascular targets. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 61, 102–12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marrelli SP, Eckmann MS & Hunte MS Role of endothelial intermediate conductance KCa channels in cerebral EDHF-mediated dilations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285, H1590–9 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dora KA, Gallagher NT, McNeish A & Garland CJ Modulation of endothelial cell KCa3.1 channels during endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor signaling in mesenteric resistance arteries. Circ Res 102, 1247–55 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards G, Feletou M & Weston AH Endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factors and associated pathways: a synopsis. Pflugers Arch 459, 863–79 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brahler S et al. Genetic deficit of SK3 and IK1 channels disrupts the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor vasodilator pathway and causes hypertension. Circulation 119, 2323–32 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang M et al. Selective phosphorylation modulates the PIP2 sensitivity of the CaM-SK channel complex. Nat Chem Biol 10, 753–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bildl W et al. Protein kinase CK2 Is coassembled with small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels and regulates channel gating. Neuron 43, 847–858 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen D, Fakler B, Maylie J & Adelman JP Organization and regulation of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel multiprotein complexes. J. Neurosci 27, 2369–2376 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fakler B & Adelman JP Control of KCa channels by calcium nano/microdomains. Neuron 59, 873–881 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren Y et al. Regulation of surface localization of the small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel, Sk2, through direct phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 281, 11769–79 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faber ESL et al. Modulation of SK Channel Trafficking by Beta Adrenoceptors Enhances Excitatory Synaptic Transmission and Plasticity in the Amygdala. J. Neurosci 28, 10803–10813 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin MT, Lujan R, Watanabe M, Adelman JP & Maylie J SK2 channel plasticity contributes to LTP at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. Nat. Neurosci 11, 170–7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohler R et al. Expression and function of endothelial Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels in human mesenteric artery: A single-cell reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and electrophysiological study in situ. Circ Res 87, 496–503 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y et al. Inactivation of Endothelial Small/Intermediate Conductance of Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels Contributes to Coronary Arteriolar Dysfunction in Diabetic Patients. J Am Heart Assoc 4, e002062 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohler R et al. Impaired hyperpolarization in regenerated endothelium after balloon catheter injury. Circ Res 89, 174–9 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bychkov R et al. Characterization of a charybdotoxin-sensitive intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in porcine coronary endothelium: relevance to EDHF. Br J Pharmacol 137, 1346–54 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burnham MP et al. Characterization of an apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channel in porcine coronary artery endothelium: relevance to EDHF. Br J Pharmacol 135, 1133–43 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sultan S, Gosling M, Abu-Hayyeh S, Carey N & Powell JT Flow-dependent increase of ICAM-1 on saphenous vein endothelium is sensitive to apamin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287, H22–8 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamazaki D et al. Novel functions of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in enhanced cell proliferation by ATP in brain endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 281, 38430–9 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AbouAlaiwi WA, Ratnam S, Booth RL, Shah JV & Nauli SM Endothelial cells from humans and mice with polycystic kidney disease are characterized by polyploidy and chromosome segregation defects through survivin down-regulation. Hum Mol Genet 20, 354–67 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nauli SM et al. Endothelial cilia are fluid shear sensors that regulate calcium signaling and nitric oxide production through polycystin-1. Circulation 117, 1161–71 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.AbouAlaiwi WA et al. Ciliary polycystin-2 is a mechanosensitive calcium channel involved in nitric oxide signaling cascades. Circ Res 104, 860–9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang M, Pascal JM, Schumann M, Armen RS & Zhang JF Identification of the functional binding pocket for compounds targeting small-conductance Ca(2)(+)-activated potassium channels. Nat Commun 3, 1021 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang M, Pascal JM & Zhang JF Unstructured to structured transition of an intrinsically disordered protein peptide in coupling Ca2+-sensing and SK channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 4828–33 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam YW et al. A V-to-F substitution in SK2 channels causes Ca(2+) hypersensitivity and improves locomotion in a C. elegans ALS model. Sci Rep 8, 10749 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nam YW et al. Structural insights into the potency of SK channel positive modulators. Sci Rep 7, 17178 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarno S et al. Selectivity of 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole, an ATP site-directed inhibitor of protein kinase CK2 (‘casein kinase-2’). FEBS Lett 496, 44–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siddiqui-Jain A et al. CX-4945, an orally bioavailable selective inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, inhibits prosurvival and angiogenic signaling and exhibits antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res 70, 10288–98 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Day RN & Davidson MW The fluorescent protein palette: tools for cellular imaging. Chem Soc Rev 38, 2887–921 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yazawa M et al. TRIC channels are essential for Ca2+ handling in intracellular stores. Nature 448, 78–82 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang M et al. Calumin, a novel Ca2+-binding transmembrane protein on the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Calcium 42, 83–90 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu S et al. Palmitate induces ER calcium depletion and apoptosis in mouse podocytes subsequent to mitochondrial oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis 6, e1976 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen MX et al. Small and intermediate conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels confer distinctive patterns of distribution in human tissues and differential cellular localisation in the colon and corpus cavernosum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 369, 602–15 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia XM et al. Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 395, 503–507 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feletou M in The Endothelium: Part 1: Multiple Functions of the Endothelial Cells-Focus on Endothelium-Derived Vasoactive Mediators (San Rafael (CA), 2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ledoux J et al. Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 9627–32 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giessel AJ & Sabatini BL M1 muscarinic receptors boost synaptic potentials and calcium influx in dendritic spines by inhibiting postsynaptic SK channels. Neuron 68, 936–47 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maingret F et al. Neurotransmitter Modulation of Small-Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels by Regulation of Ca2+ Gating. Neuron 59, 439–449 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kohler M et al. Small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels from mammalian brain. Science 273, 1709–1714 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benton DCH et al. Small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels formed by the expression of rat SK1 and SK2 genes in HEK 293 cells. J Physiol 553, 13–19 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weatherall KL, Seutin V, Liegeois JF & Marrion NV Crucial role of a shared extracellular loop in apamin sensitivity and maintenance of pore shape of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SK) channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18494–9 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamy C et al. Allosteric block of KCa2 channels by apamin. J Biol Chem 285, 27067–77 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grunnet M et al. Pharmacological modulation of SK3 channels. Neuropharmacology 40, 879–87 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abiraman K, Sah M, Walikonis RS, Lykotrafitis G & Tzingounis AV Tonic PKA Activity Regulates SK Channel Nanoclustering and Somatodendritic Distribution. J Mol Biol 428, 2521–2537 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maciaszek JL, Soh H, Walikonis RS, Tzingounis AV & Lykotrafitis G Topography of native SK channels revealed by force nanoscopy in living neurons. J Neurosci 32, 11435–40 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamilton S et al. PKA phosphorylation underlies functional recruitment of sarcolemmal SK2 channels in ventricular myocytes from hypertrophic hearts. J Physiol (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McNeish AJ, Dora KA & Garland CJ Possible role for K+ in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-linked dilatation in rat middle cerebral artery. Stroke 36, 1526–32 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McNeish AJ et al. Evidence for involvement of both IKCa and SKCa channels in hyperpolarizing responses of the rat middle cerebral artery. Stroke 37, 1277–82 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sankaranarayanan A et al. Naphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine (SKA-31), a new activator of KCa2 and KCa3.1 potassium channels, potentiates the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor response and lowers blood pressure. Mol Pharmacol 75, 281–95 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones TJ et al. Primary cilia regulates the directional migration and barrier integrity of endothelial cells through the modulation of hsp27 dependent actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Physiol 227, 70–6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.