Abstract

Increased utilization of suboptimal organs in response to organ shortage has resulted in increased incidence of delayed graft function (DGF) after transplantation. Although presumed increased costs associated with DGF are a deterrent to the utilization of these organs, the financial burden of DGF has not been established. We used the Premier Healthcare Database to conduct a retrospective analysis of healthcare resource utilization and costs in kidney transplant patients (n = 12 097) between 1/1/2014 and 12/31/2018. We compared cost and hospital resource utilization for transplants in high-volume (n = 8715) vs low-volume hospitals (n = 3382), DGF (n = 3087) vs non-DGF (n = 9010), and recipients receiving 1 dialysis (n = 1485) vs multiple dialysis (n = 1602). High-volume hospitals costs were lower than low-volume hospitals ($103 946 vs $123 571, P < .0001). DGF was associated with approximately $18 000 (10%) increase in mean costs ($130 492 vs $112 598, P < .0001), 6 additional days of hospitalization (14.7 vs 8.7, P < .0001), and 2 additional ICU days (4.3 vs 2.1, P < .0001). Multiple dialysis sessions were associated with an additional $10 000 compared to those with only 1. In conclusion, DGF is associated with increased costs and length of stay for index kidney transplant hospitalizations and payment schemes taking this into account may reduce clinicians’ reluctance to utilize less-than-ideal kidneys.

Keywords: delayed graft function, dialysis, kidney disease, kidney transplant

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), offering survival and quality of life advantages compared to dialysis.1 Severe ischemic reperfusion injury following allograft implantation can result in significant renal tubular cell dysfunction and continued need for supportive renal replacement therapy in the early postoperative period.2–4 Delayed graft function (DGF)–where a transplant recipient continues to require dialysis following transplantation–is a common complication of ischemia reperfusion injuries.5,6 DGF is broadly defined as the need for dialysis within the first 7 days of transplantation, regardless of indication, and is associated with several donor and transplant factors including advanced donor age, higher kidney donor profile index (KDPI), stroke/anoxia as cause of death, elevated terminal serum creatinine, and prolonged cold ischemia.7–10

Recent changes in deceased donor allocation in the United States (US) under the new Kidney Allocation System (KAS) implemented in 2014 were associated with an increase in DGF–presumably due to increased cold ischemia time that resulted from increased organ sharing and increased dialysis vintage among recipients.11,12 With the increased focus on the use of less-than-ideal organs to lower the currently high discard rate, there is concern of a further increase in the incidence of DGF in the United States–and the attendant costs associated with this complication.12,13 Increased costs that are incurred when using less-than-ideal organs that progress to DGF potentially deter transplant centers from accepting these organs despite evidence that this approach would still be cost-effective for the healthcare system vs staying on dialysis, while also providing significant quality of life and mortality benefits.13 We attempt, using direct hospital-reported charge data from the Premier Healthcare Database, to estimate the increased financial costs incurred with DGF following kidney transplantation.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design and data sources

A retrospective analysis of hospital healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and cost in kidney transplant patients among high- and low-volume transplant centers was conducted using the Premier Healthcare Database (Premier). Premier is a hospital-based, service-level, all-payer database that contains information on inpatient discharges from over 970 US hospitals. Premier data are geographically diverse, capturing over 108 million inpatient encounters and representing 25% of all inpatient US admissions.14 Premier contains administrative, HRU, financial data (hospital-reported costs and charges) augmented with inpatient records, prescription claims, and selected laboratory test results. Hospital admission records, including diagnosis and procedures, are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9 and ICD-10) classification system. Inpatient admissions and hospital-based outpatient care within the same hospital can be tracked over time, allowing assessment of readmissions and total hospital length of stay for a subset of patients.

2.2 |. Study population

We included inpatient admissions for kidney transplant among adults aged ≥18 years presenting between 01/01/2014 and 12/31/2018. Kidney transplant admissions were identified by the presence of at least one kidney transplant-related charge code or all of the following: (a) a kidney transplant ICD-9 or ICD-10 procedure code, (b) a charge code for at least one immunosuppressant drug, and (c) a charge code for ≥1 kidney procurement within the same admission. Subjects with multiple organ transplants in the same admission were excluded.

2.3 |. Study definitions

Hospital kidney transplant volume was characterized as “high” or “low” based on the number of annual transplant procedures. The average annual number of kidney transplant procedures in this dataset was 50. Hospitals performing ≥50 kidney transplants per year were classified as high volume and <50 as low volume. DGF was defined by a patient having at least one dialysis procedure within seven days of a qualifying transplant procedure. Given questions about the clinical value of a single dialysis treatment for determining patients who were truly experiencing DGF, patients who received dialysis in this early postoperative period were further categorized into those who received only one dialysis session and those who received multiple sessions.

Given the limitations of coding in the dataset, definitive segregation of all deceased and living donor kidney transplants was not feasible. However, for the subset of cases (n = 357; 3.0%) that were clearly identified as living donor transplants, a sensitivity analysis was performed (Tables S1 and S2).

2.4 |. Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics at the hospital- and patient-level were examined for the overall study population and by hospital volume, DGF, and dialysis utilization. Patient characteristics included age at admission, race, and sex. Characteristics of reporting hospitals included urban/rural status, teaching status, and number of beds.

The primary analyses examined the hospital volume, impact of DGF, and dialysis utilization on HRU and cost within the initial index hospitalization for the transplant admission. HRU endpoints captured in the analysis included total length of stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and ICU-related LOS. Secondary analyses included all subsequent HRU and costs for readmissions within 90 days that occurred at the original transplant hospital.

Descriptive statistics were provided for the overall population and reported by hospital volume, DGF status, and dialysis utilization. HRU and costs within cohorts of DGF status and by dialysis utilization were compared between high- and low-volume hospitals. Statistical tests of significance for observed differences between groups were conducted using chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. For outcomes that were not normally distributed, such as duration of stay or costs, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare the medians. ANOVA was performed when comparing three groups (ie, non-DGF (or 0 dialysis), 1 dialysis, and 2+ dialyses). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided alpha 0.05.

Due to the skewness of cost data, admissions with costs below the first or above the 99th percentile for the sample were excluded from further analysis. All costs were inflation-adjusted to 2018 US dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index produced by the US Bureau of Labor. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Demographics and hospital characteristics

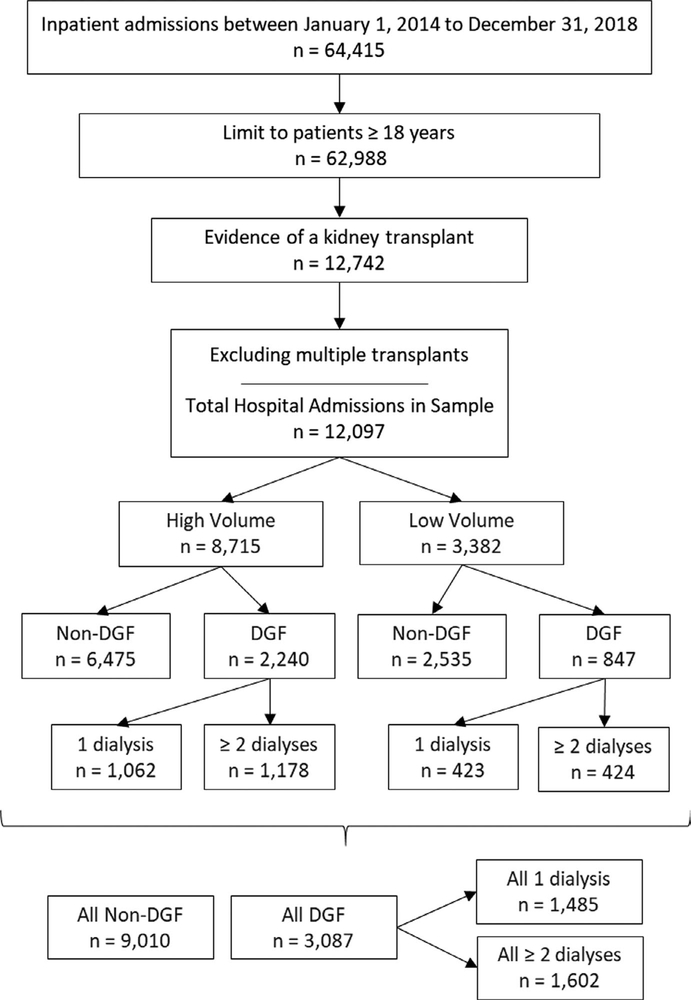

A total of 12 097 kidney transplant admissions across 56 unique hospitals were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Patient and hospital characteristics for the total sample and hospital volume, DGF status, and dialysis utilization are presented in Table 1. The mean age across all initial admissions was 51.7 ± 13.4 years, and subjects were predominantly white (53%) and male (61%). Most admissions were to large hospitals (72%), teaching hospitals (81.2%), and/or urban hospitals (95.5%). Patient characteristics were similar across hospital volume practice settings. Roughly 80% of both high- and low-volume hospitals were teaching hospitals. Low-volume hospitals were more often located in rural areas (10% vs 2% of high-volume settings).

FIGURE 1.

Sample attrition and stratification

TABLE 1.

Sample demographic and hospital characteristics

| Hospital volume |

DGF status |

Dialysis utilization |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All admissions n = 12 097 | High volume n = 8715 | Low volume n = 3382 | DGF n = 3087 | Non-DGF n = 9010 | 1 dialysis n = 1485 | ≥2 dialyses n = 1602 | |

| Patient age at admission (y) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.7 (13.4) | 51.2 (13.3) | 53.0 (13.6) | 53.31 (12.5) | 51.16 (13.6) | 52.63 (12.9) | 53.95 (12.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 4704 (38.9%) | 3413 (39.2%) | 1291 (38.2%) | 1105 (35.8%) | 3599 (39.9%) | 572 (38.5%) | 533 (33.3%) |

| Male | 7393 (61.1%) | 5302 (60.8%) | 2091 (61.8%) | 1982 (64.2%) | 5411 (60.1%) | 913 (61.5%) | 1069 (66.7%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| Black | 2716 (22.5%) | 2048 (23.5%) | 668 (19.8%) | 991 (32.1%) | 1725 (19.2%) | 446 (30.0%) | 545 (34.0%) |

| White | 6468 (53.5%) | 4411 (50.6%) | 2057 (60.8%) | 1360 (44.1%) | 5108 (56.7%) | 680 (45.8%) | 680 (42.5%) |

| Other | 2548 (21.1%) | 1986 (22.8%) | 562 (16.6%) | 659 (21.4%) | 1889 (21.0%) | 321 (21.6%) | 338 (21.1%) |

| Unknown | 365 (3.0%) | 270 (3.1%) | 95 (2.8%) | 77 (2.5%) | 288 (3.2%) | 38 (2.6%) | 39 (2.4%) |

| DGF status, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 3087 (25.5%) | 2240 (25.7%) | 847 (25.0%) | 3087 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1485 (100%) | 1602 (100%) |

| No | 9010 (74.5%) | 6475 (74.3%) | 2535 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9010 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Dialysis utilization, n (%) | |||||||

| 1 dialysis | 1485 (48.1%) | 1062 (47.4%) | 423 (49.9%) | 1485 (48.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1485 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| ≥2 dialyses | 1602 (51.9%) | 1178 (52.6%) | 424 (50.1%) | 1602 (51.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1602 (100%) |

| Hospital admission by setting, n (%) | |||||||

| High volume | 8715 (72.0%) | 8715 (72.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2240 (25.7%) | 6475 (74.3%) | 1062 (71.5%) | 1178 (73.5%) |

| Low volume | 3382 (28.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3382 (28.0%) | 847 (25.0%) | 2535 (75.0%) | 423 (28.5%) | 424 (26.5%) |

| Hospital vicinity to a city center, n (%) | |||||||

| Rural | 539 (4.5%) | 198 (2.3%) | 341 (10.1%) | 117 (3.8%) | 422 (4.7%) | 67 (4.5%) | 50 (3.1%) |

| Urban | 11 558 (95.5%) | 8517 (97.7%) | 3041 (89.9%) | 2970 (96.2%) | 8588 (95.3%) | 1418 (95.5%) | 1552 (96.9%) |

| Teaching hospital status, n (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 9824 (81.2%) | 6970 (80.0%) | 2854 (84.4%) | 2670 (86.5%) | 7154 (79.4%) | 1251 (84.2%) | 1419 (88.6%) |

| No | 2273 (18.8%) | 1745 (20.0%) | 528 (15.6%) | 417 (13.5%) | 1856 (20.6%) | 234 (15.8%) | 183 (11.4%) |

| Total number of beds, grouped, n (%) | |||||||

| Up to 199 | 3 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.0%) |

| 200–299 | 13 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (0.4%) | 2 (0.0%) | 11 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| 300–399 | 2182 (18.0%) | 1745 (20.0%) | 437 (12.9%) | 423 (13.7%) | 1759 (19.5%) | 222 (15.0%) | 201 (12.6%) |

| 400–499 | 321 (2.7%) | 110 (1.3%) | 211 (6.2%) | 116 (3.8%) | 205 (2.3%) | 48 (3.2%) | 68 (4.2%) |

| 500+ | 9578 (79.2%) | 6860 (78.7%) | 2718 (80.4%) | 2545 (82.4%) | 7033 (78.1%) | 1215 (81.8%) | 1330 (83.0%) |

| US census region, n (%) | |||||||

| Midwest | 1760 (14.6%) | 731 (8.4%) | 1029 (30.4%) | 508 (16.5%) | 1252 (13.9%) | 253 (17.0%) | 255 (15.9%) |

| Northeast | 2113 (17.5%) | 1171 (13.4%) | 942 (27.9%) | 606 (19.6%) | 1507 (16.7%) | 260 (17.5%) | 346 (21.6%) |

| South | 6100 (50.4%) | 5114 (58.7%) | 986 (29.2%) | 1517 (49.1%) | 4583 (50.9%) | 790 (53.2%) | 727 (45.4%) |

| West | 2124 (17.6%) | 1699 (19.5%) | 425 (12.6%) | 456 (14.8%) | 1668 (18.5%) | 182 (12.3%) | 274 (17.1%) |

Approximately half of the admissions were from the South US census region (50.4%), with approximately 17% of admissions located in the West and Northeast regions, respectively, and 14% in the Midwest. Medicare was the primary insurer for most admissions (67%).

Approximately one-quarter of all kidney transplant admissions in the sample experienced DGF–of whom 52% received multiple dialysis treatments.

3.2 |. HRU and cost outcomes by hospital volume

Table 2 summarizes HRU and cost for initial transplant admissions and initial transplant plus 90-day readmissions to the same hospital by hospital volume. After exclusion of the 1% outlier at both ends, mean hospital cost for kidney transplant admissions was $109 425 ± $52 823, with a maximum observed cost of $319 492 (Table 2). Average total LOS was 8.6 ± 7.6 days and more than half the patients (57%) were admitted to the ICU for at least part of the initial admission, for an average ICU LOS of 2.5 ± 6.3 days. Approximately one-third of patients (34.1%, n = 4129) were readmitted to the same hospital within 90 days.

TABLE 2.

HRU and costs for initial admission and 90-d readmission by hospital volume

| Admissions (n, %) | All admissions |

High-volume hospital admissions |

Low-volume hospital admissions |

P-value (high vs low volume) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 097 | 100% | 8715 | 72.0% | 3382 | 28.0% | ||

| Initial transplant | |||||||

| Costa | |||||||

| n (%) | 11 855 | 98.0% | 8545 | 98.0% | 3310 | 97.9% | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $109 425 | $52 823 | $103 946 | $49 427 | $123 571 | $58 394 | |

| Min, Max | $13 998 | $319 492 | $13 998 | $319 492 | $14 079 | $310 079 | |

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.6 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 8.8 | 9.1 | .0854 |

| Min, Max | 1 | 397 | 1 | 397 | 2 | 176 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 6866 | 56.8% | 5133 | 58.9% | 1733 | 51.2% | <.0001 |

| ICU LOS (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 | 6.3 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 8.0 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 376 | 0 | 376 | 0 | 174 | |

| 90-d readmissionb (n, %) | 4129 | 34.1% | 3025 | 34.7% | 1104 | 32.6% | .0314 |

| Initial transplant plus 90-d readmissions to same hospital | |||||||

| Costa | |||||||

| n, % | 11 855 | 98.0% | 8539 | 98.0% | 3316 | 98.0% | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $117 173 | $57 953 | $111 735 | $55 022 | $131 177 | $62 772 | |

| Min, Max | $14 062 | $352 702 | $14 062 | $352 702 | $14 690 | $348 270 | |

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.2 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 9.9 | .3218 |

| Min, Max | 1 | 209 | 1 | 209 | 2 | 148 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 6959 | 57.5% | 5190 | 59.6% | 1769 | 52.3% | <.0001 |

| ICU LOS (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 8.3 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 376 | 0 | 376 | 0 | 174 | |

After exclusion of outliers.

Includes only readmissions to the same hospital.

High-volume hospitals had lower costs ($103 946 vs $123 571, P < .0001) despite higher rates of ICU admission (58.9% vs 51.2%, P < .0001)–perhaps as a result of shorter mean ICU LOS (2.3 vs 3.0 days, P < .0001). Total LOS did not vary significantly by transplant volume. 90-day, same-hospital readmissions were marginally higher for higher transplant volume hospitals (35% vs 33%, P = .031).

3.3 |. Impact of DGF status and hospital volume on HRU and costs

Approximately one-quarter of all kidney transplant recipients at both high and low transplant volume hospitals experienced DGF (Tables 3 and 4). Patients who experienced DGF displayed longer initial LOS (12.1 ± 12.9 vs 7.4 ± 0.8 days, P < .0001), more frequent ICU admissions (59% vs 56%, P = .025), longer ICU stays, and a significantly higher 90-day readmission rate (46% vs 30%, P < .0001). Patients with DGF incurred significantly higher costs over the course of the initial hospitalization and with readmissions over the subsequent 90 days ($130 492 ± 56 701 vs $112 598 ± 57 675, P < .0001). High-volume transplant centers had lower costs for transplant recipients overall than those at low-volume centers ($115 700 ± $43 759 vs $126 270 ± $57 310, P < .0001) and costs for recipients without DGF were significantly lower ($99 826 ± $50 628 vs $122 692 ± $58 728 P < .0001).

TABLE 3.

HRU and costs for initial admission and 90-d readmission by DGF status for all subjects

| Admissions (n, %) | All admissions n = 12 097 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGF |

Non-DGF |

P-value (DGF vs non-DGF) | |||

| 3087 | 25.5% | 9010 | 74.5% | ||

| Initial transplant | |||||

| Costa | |||||

| N, % | 3031 | 98.2% | 8824 | 97.9% | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $118 535 | $47 992 | $106 296 | $54 033 | |

| Min, Max | $16 377 | $316 728 | $13 998 | $319 492 | |

| Length of stay (d) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.1 | 12.9 | 7.4 | 3.8 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 3 | 397 | 1 | 88 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 1824 | 59.1% | 5042 | 56.0% | .0025 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 | 11.2 | 2.0 | 3.2 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 376 | 0 | 68 | |

| 90-d readmissionb (n, %) | 1408 | 45.6% | 2721 | 30.2% | <.0001 |

| Initial transplant plus 90-d readmissions to same hospital | |||||

| Costa | |||||

| n, % | 3031 | 98.2% | 8824 | 97.9% | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $130 492 | $56 701 | $112 598 | $57 675 | |

| Min, Max | $16 377 | $352 702 | $14 062 | $347 400 | |

| Length of stay (d) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.7 | 13.5 | 8.7 | 6.9 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 2 | 209 | 1 | 112 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 1864 | 60.4% | 5095 | 56.6% | .0002 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 | 11.5 | 2.1 | 3.4 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 376 | 0 | 68 | |

After exclusion of outliers

Includes only readmissions to the same hospital

TABLE 4.

HRU and costs for initial admission and 90-d readmission by DGF status for high and low volume

| Admissions (n, %) | High-volume hospital admissions n = 8715 |

Low-volume hospital admissions n = 3382 |

HV vs LV | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGF |

Non-DGF |

P-value (HV DGF/non-DGF) | DGF |

Non-DGF |

P-value (LV DGF/non-DGF) | ||||||

| 2240 | 25.7% | 6475 | 74.3% | 847 | 25.0% | 2535 | 75.0% | ||||

| Costa | |||||||||||

| n (%) | 2218 | 98.00% | 6327 | 97.70% | <.0001 | 813 | 96.00% | 2497 | 98.50% | .1292 | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $115 700 | $43 759 | $99 826 | $50 628 | $126 270 | $57 310 | $122 692 | $58 728 | |||

| Min, Max | $16 377 | $316 728 | $13 998 | $319 492 | $17 380 | $310 079 | $14 079 | $305 498 | |||

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 11.7 | 11.5 | 7.4 | 3.6 | <.0001 | 13.2 | 15.9 | 7.4 | 4.2 | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Min, Max | 3 | 397 | 1 | 88 | 4 | 176 | 2 | 59 | |||

| ICU admission (n, %) | 1363 | 60.9% | 3770 | 58.2% | .0295 | 461 | 54.4% | 1272 | 50.2% | .0322 | <0.0001 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 | 9.6 | 1.9 | 3 | <.0001 | 5.4 | 14.5 | 2.2 | 3.6 | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 376 | 0 | 0 | 68 | 174 | 0 | 48 | |||

| 90-d readmissionb (n, %) | 1051 | 46.90% | 1974 | 30.50% | <.0001 | 357 | 42.20% | 747 | 29.50% | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Initial transplant plus 90-d readmissions to same hospital | |||||||||||

| Costa | |||||||||||

| n, % | 2215 | 98.9% | 6324 | 97.7% | <.0001 | 816 | 96.3% | 2500 | 98.6% | .0002 | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $127 523 | $52 111 | $106 205 | $54 947 | $138 552 | $66 985 | $128 770 | $61 155 | |||

| Min, Max | $16 377 | $352 702 | $14 062 | $343 383 | $17 380 | $348 270 | $14 690 | $347 400 | |||

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.6 | 12.9 | 8.8 | 6.9 | <.0001 | 15.0 | 14.8 | 8.4 | 6.8 | <.0001 | 0.3218 |

| Min, Max | 2 | 209 | 1 | 112 | 3 | 148 | 2 | 80 | |||

| ICU admission (n, %) | 1390 | 62.1% | 3800 | 58.7% | .0051 | 474 | 56.0% | 1295 | 51.1% | .0139 | <0.0001 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 3.2 | <.0001 | 5.7 | 14.8 | 2.3 | 3.9 | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 376 | 0 | 68 | 0 | 174 | 0 | 48 | |||

After exclusion of outliers.

Includes only readmissions to the same hospital.

There was substantial variation in total LOS and ICU LOS for DGF admissions for both high- and low-volume hospitals (11.7 vs 7.4 days for high volume and 13.2 vs 7.4 for low volume, P < .0001). High-volume hospitals had higher 90-day readmission rates to the same hospital for recipients who experienced DGF compared to those at low transplant volume hospitals (46.90% vs 30.50% for high volume and 42.20% vs 29.50% for low volume, P < .0001).

3.4 |. Impact of dialysis utilization and hospital volume on HRU and costs

Approximately half the transplant recipients in our cohort required multiple dialysis sessions (52%, Figure 1). The initial LOS for individuals needing multiple sessions was significantly longer and while the proportion needing ICU admissions were slightly higher, the duration of ICU LOS was nearly double that of patients with one dialysis session (5.3 ± 14.4 vs 2.6 ± 5.7, P < .0001, Tables 5 and 6). Many more patients (58.8%) needing multiple sessions were readmitted within 90 days, increasing the difference in the cost of managing these patients to nearly $15 000 per patient.

TABLE 5.

HRU and costs for initial admission and 90-d readmission by dialysis utilization

| Admissions (n, %) | All admissions n = 12 097 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DGF (0 dialyses) |

1 dialyses |

≥ 2 dialyses |

P-value (0 vs 1 vs ≥2 dialyses) | ||||

| 9010 | 74.5% | 1485 | 12.3% | 1602 | 13.2% | ||

| Costa | |||||||

| n, % | 8824 | 97.9% | 1468 | 98.9% | 1563 | 97.6% | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $106 296 | $54 033 | $113 640 | $47 353 | $123 132 | $48 148 | |

| Min, Max | $13 998 | $319 492 | $17 380 | $316 728 | $16 377 | $310 079 | |

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 | 3.8 | 9.2 | 6.7 | 14.8 | 16.2 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 1 | 88 | 3 | 176 | 4 | 397 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 5042 | 56.0% | 858 | 57.8% | 966 | 60.3% | .0038 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 14.4 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 68 | 0 | 174 | 0 | 376 | |

| 90-d readmissionb (n, %) | 2721 | 30.2% | 564 | 38.0% | 844 | 52.7% | <.0001 |

| Initial transplant plus 90-d readmissions to same hospital | |||||||

| Costa | |||||||

| n, % | 8824 | 97.9% | 1473 | 99.2% | 1558 | 97.3% | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $112 598 | $57 675 | $122 870 | $54 587 | $137 699 | $57 729 | |

| Min, Max | $14 062 | $347 400 | $17 380 | $334 409 | $16 377 | $352 702 | |

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.7 | 6.9 | 11.3 | 9.4 | 17.9 | 15.7 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 1 | 112 | 2 | 89 | 3 | 209 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 5095 | 56.6% | 873 | 58.8% | 991 | 61.9% | .0002 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 14.8 | <.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 68 | 0 | 174 | 0 | 376 | |

After exclusion of outliers

Includes only readmissions to the same hospital

TABLE 6.

HRU and costs for initial admission and 90-d readmission by dialysis utilization for high and low volume

| Admissions (n, %) | High-volume hospital admissions n = 8715 |

Low-volume hospital admissions n = 3382 |

HV vs LV | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DGF (0 dialyses) |

1 dialysis |

≥2 dialyses |

P-value* | Non-DGF (0 dialyses) |

1 dialysis |

≥2 dialyses |

P-value* | ||||||||

| 6475 | 74.3% | 1062 | 12.2% | 1178 | 13.5% | 2535 | 75.0% | 423 | 12.5% | 424 | 12.5% | ||||

| Costa | |||||||||||||||

| n (%) | 6327 | 97.7% | 1057 | 99.5% | 1161 | 98.6% | <.0001 | 2497 | 98.5% | 411 | 97.2% | 402 | 94.8% | .0140 | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $99 826 | $50 628 | $110 695 | $42 506 | $120 256 | $44 399 | $122 692 | $58 728 | $121 213 | $57 354 | $131 439 | $56 873 | |||

| Min, Max | $13 998 | $319 492 | $19 674 | $316 728 | $16 377 | $294 707 | $14 079 | $305 498 | $17 380 | $308 008 | $20 717 | $310 079 | |||

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 | 3.6 | 9.2 | 4.7 | 14 | 14.8 | <.0001 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 16.8 | 19.5 | <.0001 | 0.0854 |

| Min, Max | 1 | 88 | 3 | 50 | 4 | 397 | 2 | 59 | 4 | 176 | 4 | 166 | |||

| ICU admission (n, %) | 3770 | 58.2% | 653 | 61.5% | 710 | 60.3% | .0790 | 1272 | 50.2% | 205 | 48.5% | 256 | 60.4% | .0002 | <0.0001 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.9 | 3 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 12.9 | <.0001 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 17.9 | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 376 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 174 | 0 | 164 | |||

| 90-d readmissionb (n, %) | 1974 | 30.50% | 424 | 39.9% | 627 | 53.2% | <.0001 | 747 | 29.50% | 140 | 33.1% | 217 | 51.2% | <.0001 | 0.0314 |

| Initial transplant plus 90-d readmissions to same hospital | |||||||||||||||

| Costa | |||||||||||||||

| n, % | 6324 | 97.7% | 1058 | 99.6% | 1157 | 98.2% | <.0001 | 2500 | 98.6% | 415 | 98.1% | 401 | 94.6% | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | $106 205 | $54 947 | $120 067 | $49 767 | $134 342 | $53 280 | $128 770 | $61 155 | $130 018 | $64 806 | $147 384 | $68 130 | |||

| Min, Max | $14 062 | $343 383 | $19 674 | $322 842 | $16 377 | $352 702 | $14 690 | $347 400 | $17 380 | $334 409 | $20 717 | $348 270 | |||

| Length of stay (d) | |||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.8 | 6.9 | 11.5 | 9.0 | 17.4 | 15.1 | <.0001 | 8.4 | 6.8 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 19.2 | 17.4 | <.0001 | 0.3218 |

| Min, Max | 1 | 112 | 2 | 80 | 3 | 209 | 2 | 80 | 3 | 89 | 4 | 148 | |||

| ICU admission (n, %) | 3800 | 58.7% | 662 | 62.3% | 728 | 61.8% | .0193 | 1295 | 51.1% | 211 | 49.9% | 263 | 62.0% | .0001 | <0.0001 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | |||||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 13.3 | <.0001 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 18.1 | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Min, Max | 0 | 68 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 376 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 174 | 0 | 164 | |||

Note:

P-value compared 1 vs ≥2 dialyses.

After exclusion of outliers.

Includes only readmissions to the same hospital.

3.5 |. Sensitivity analysis

Only 357 transplant recipients were clearly identifiable as recipients of living donor kidneys in our cohort. After excluding the outliers as previously described, 27 recipients (7.6%) were identified as having experienced DGF. While patients with living donor transplants incurred fewer costs, the differences between those who developed DGF and those did not were larger in absolute terms ($16 293 vs $12 239) in comparison with the overall cohort.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Currently, DGF impacts more than 1 out of every 5 kidney transplants in the United States, including 10%-40% of deceased donor transplants.5,15,16 With fixed reimbursements for kidney transplantation, the increased costs associated with the occurrence of DGF creates a financial disincentive for the acceptance and transplantation of organs that are at higher risk of developing DGF.17,18 These financial disincentives are perhaps greatest for organs with high KDPI and those that accumulate long cold ischemia time during the allocation process despite evidence that would suggest a weak link between organ quality and costs incurred.19 With the recent changes in KAS and broader organ sharing, there was a notable increase in the incidence of DGF following deceased donor transplantation.11,15,17 Further policy changes in how geography is incorporated into kidney allocation are expected.20,21 Variation in the organ supply and demand is likely to result in broader sharing of organs which in turn is likely to contribute to further increases in cold ischemia time and thus possible a higher incidence of DGF.22,23

Currently in the United States, fewer than 1 in 5 kidneys is accepted when first offered for transplantation and nearly 1 in 5 kidneys is being discarded annually.22,24 The overall reluctance to use any deceased donor kidneys, despite evidence of improved patient survival and quality of life with even less-than-ideal organs and the mounting organ shortage, does not make clinical nor economic sense.25–28 While concerns about the transplant center metrics have been frequently cited as an explanation for the lower acceptance of organs particular at the higher KDPI, financial considerations are another potential source of concern.29–31 As the incidence of DGF after kidney transplantation increases, a thorough understanding of the financial implications of DGF is needed in order to ensure appropriate resource allocation and remove financial disincentives toward the use of kidneys at higher risk for experiencing DGF.17,32,33 Our results clearly demonstrate the increased costs during the incident hospitalization following transplantation as well as the additional burden of 90-day readmissions for those individuals who experience DGF and for the first time provide point estimates of the true hospital financial burden of this complication. Notably, our analysis also demonstrates the increased HRU with more frequent and longer ICU admissions for these individuals. Our analysis also demonstrates the increased financial burden associated with the need for multiple dialysis sessions in the early postoperative period, by demonstrating the HRU and costs differences between those individuals who have one treatment session vs those with multiple sessions. These differences further underscore the need to revisit the current definition of DGF. While the current definition of DGF is convenient and seemingly objective, the initiation of dialysis for patients in the postoperative period is highly subjective without a clear standard, resulting in considerable variation. This is especially true in circumstances where patients receive just a single treatment.

Our results demonstrate that DGF was associated with an approximately $18 000 increase in mean cost, 6 additional days of hospitalization, and 2 additional days of ICU stay. Notably, the increased cost of transplantation associated with DGF was observed across all settings, including both high- and low-volume hospitals as well as urban and rural settings. This corresponds with the findings where DGF was used as an independent predictor of HRU in kidney transplantation and DGF was expected to result in higher costs and longer LOS than non-DGF.34–36 On average, hospitals saw an increase of >10% of total costs when a patient experienced DGF after kidney transplantation. Additionally, ICU LOS and 90-day readmission were almost double for patients with DGF than for those without. However, the differences between high-volume vs low-volume hospital LOS and readmission bear examination. While high-volume hospitals have shorter LOS, this appears to be offset by higher rates of 90-day readmission. Further exploration of this observation is warranted.

The intensity of the dialysis requirements for recipients who experienced DGF was also associated with cost, and recipients who required multiple dialysis treatments displayed increases of over $10 000 across settings compared to recipients who experienced DGF with 1 dialysis treatment. Other studies have also identified hospital LOS and the need for dialysis as major factors driving hospital resource consumption.37–39 These findings suggest that that as a patient requires more dialysis treatments after transplantation, which is likely an indicator of true DGF and not simply fluid overload or hyperkalemia, the greater the LOS and as a result, more HRU. As expected, patients with DGF exhibited greater LOS, dialysis treatments, and ultimately resulted in higher HRU and costs than for patients without DGF.

These findings have significant implications for transplant hospitalization reimbursement. With the transplant hospitalization reimbursement remaining constant, the rising costs of DGF treatments are essentially a financial disincentive for hospitals to transplant deceased donor organs that are perceived to be associated with a higher risk of DGF, thus contributing to more turn downs and a greater likelihood of discard.

Despite the significant cost increase of DGF following kidney transplantation, transplant remains the most cost-effective treatment option for patients with ESKD when compared to staying on dialysis. In addition, there are improvements in the quality of life and mortality benefits that follow transplantation. There is a net overall cost savings when comparing the cost of transplantation, regardless of the development of DGF as compared to staying on dialysis. Therefore, the increased costs from complications with DGF should not discourage transplantation. While ascertaining the true disincentive that results from the increased financial costs of DGF for transplant centers as opposed to other concerns, such as center flagging or poor allograft outcomes for individual patients is not currently feasible, it needs to be acknowledged as a potential concern. Further, given the potential system wide savings associated with transplantation, coupled with the desire to dramatically increase organ utilization rates, policy changes that would remove the financial disincentives to transplantation of organs perceived to be at high risk for developing DGF ought to be considered.

Although this is a large cohort analysis, the study had several limitations. First, Premier is unable to fully distinguish between recipients of living donor vs deceased donor kidneys. The small sub-cohort of individuals who clearly received a living donor transplant experienced a much lower rate of DGF but experienced a similar increase in costs when they experienced DGF. However, it remains possible that the subset of patients without DGF in our cohort may have an overrepresentation of living donor recipients. This would result in lower average costs for this set of patients which in turn may exaggerate the observed differences in the increased costs being attributed to DGF. However, given that our overall DGF rates in our cohort are keeping with nationally reported incidence for both deceased donor and living donor transplant recipients, we believe that the impact of this is likely to be small and do not detract from the specific findings of increased LOS, increased ICU admission and ICU LOS as well as higher readmission rates among recipients who experienced DGF.

Additionally, since this is a retrospective analysis of HRU and costs, there may be factors that can affect costs including laboratory, radiology, or other testing which are not included in this evaluation. Although Premier is a very extensive database that includes a wide range of hospitals, it is a performance improvement database, which means that the data definitions might not perfectly align among different centers. Furthermore, the study cohort was not geographically diverse, as more than half of the study cohort was located in the southeastern area of the United States which would be consistent with the current geographic variation in the incidence of ESRD which is highest in the southeastern United States. Additional studies are required to confirm that these relationships are consistent throughout the country.

5 |. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found that the development of DGF after kidney transplantation was associated with significantly increased cost and HRU in both high-volume and low-volume hospitals. While strategies to lower the incidence of DGF would have a positive financial outcome for transplant centers, policy makers should need to consider the financial disincentives in the current system where reimbursement rates do not account for the complexities associated with accepting a less-than-ideal organ for patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Young Investigator Grant from the National Kidney Foundation (to SAH). SAH is also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2 TR001874). SM is supported by NIDDK grants R01-DK114893, R01-MD014161, and U01-DK116066. Frank A. Corvino, Allison Dillon, and Weiying Wang are employees of Genesis Research, who provides consulting services to Angion Biomedica.

Funding information

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Number: R01-DK114893, R01-MD014161 and U01-DK116066; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant/Award Number: KL2-TR001874; National Kidney Foundation, Grant/Award Number: Young Investigator Grant

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Sumit Mohan is an scientific advisory board member for Angion Biomedica Corp.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abecassis M, Bartlett ST, Collins AJ, et al. Kidney transplantation as primary therapy for end-stage renal disease: a National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQITM) conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(2):471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvadori M, Rosso G, Bertoni E. Update on ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Pathogenesis and treatment. World J Transplant. 2015;5(2):52–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Alam A, Soo AP, George AJT, Ma D. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Reduces Long Term Renal Graft Survival: Mechanism and Beyond. EBioMedicine. 2018;28:31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker RJ, Marks SD. Management of chronic renal allograft dysfunction and when to re-transplant. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(4):599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siedlecki A, Irish W, Brennan DC. Delayed graft function in the kidney transplant. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(11):2279–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philipponnet C, Aniort J, Garrouste C, Kemeny J-L, Heng A-E. Ischemia reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(52):e13650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall IE, Reese PP, Doshi MD, et al. Delayed graft function phenotypes and 12-month kidney transplant. Outcomes. 2017;101(8):1913–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojo AO, Wolfe RA, Held PJ, Port FK, Schmouder RL. Delayed graft function: risk factors and implications for renal allograft survival. Transplantation. 1997;63(7):968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irish WD, Ilsley JN, Schnitzler MA, Feng S, Brennan DC. A risk prediction model for delayed graft function in the current era of deceased donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(10):2279–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redfield RR, Scalea JR, Zens TJ, et al. Predictors and outcomes of delayed graft function after living-donor kidney transplantation. Transplant Int. 2016;29(1):81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart DE, Kucheryavaya AY, Klassen DK, Turgeon NA, Formica RN, Aeder MI. Changes in deceased donor kidney transplantation one year after KAS implementation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1834–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taber DJ, DuBay D, McGillicuddy JW, et al. Impact of the new kidney allocation system on perioperative outcomes and costs in kidney transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(4):585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez D, Dubay D, Prabhakar B, Taber DJ. Evolving trends in racial disparities for peri-operative outcomes with the new kidney allocation system (KAS) implementation. J Racial Eth Health Disparities. 2018;5(6):1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Premier Healthcare Database White Paper: Data that informs and performs. Premier Inc. https://products.premierinc.com/downloads/PremierHealthcareDatabaseWhitepaper.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massie AB, Luo X, Lonze BE, et al. Early changes in kidney distribution under the new allocation system. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(8):2495–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melih KV, Boynuegri B, Mustafa C, Nilgun A. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of delayed graft function in deceased donor kidney transplantation. Transpl Proc. 2019;51(4):1096–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. The changing financial landscape of renal transplant practice: a national cohort analysis. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(2):377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englesbe MJ, Dimick JB, Fan Z, Baser O, Birkmeyer JD. Case mix, quality and high-cost kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1108–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stahl CC, Wima K, Hanseman DJ, et al. Organ quality metrics are a poor predictor of costs and resource utilization in deceased donor kidney transplantation. Surgery. 2015;158(6):1635–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder JJ, Salkowski N, Wey A, Pyke J, Israni AK, Kasiske BL. Organ distribution without geographic boundaries: a possible framework for organ allocation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(11):2635–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellison MD, Edwards LB, Edwards EB, Barker CF. Geographic differences in access to transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2003;76(9):1389–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King KL, Husain SA, Mohan S. Geographic variation in the availability of deceased donor kidneys per wait-listed candidate in the United States. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4(11):1630–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Husain SA, King KL, Dube GK, et al. Regional disparities in transplantation with deceased donor kidneys with kidney donor profile index less than 20% among candidates with top 20% estimated post transplant survival. Prog Transplant. 2019;29(4):354–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohan S, Chiles MC, Patzer RE, et al. Factors leading to the discard of deceased donor kidneys in the United States. Kidney Int. 2018;94:187–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper M, Formica R, Friedewald J, et al. Report of national kidney foundation consensus conference to decrease kidney discards. Cli Transplants. 2019;33:e13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohan S, Foley K, Chiles MC, et al. The weekend effect alters the procurement and discard rates of deceased donor kidneys in the United States. Kidney Int. 2016;90:157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, et al. Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA. 2005;294(21):2726–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husain SA, King KL, Pastan S, et al. Association between declined offers of deceased donor kidney allograft and outcomes in kidney transplant candidates. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1910312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schold JD, Patzer RE, Pruett TL, Mohan S. Quality Metrics in Kidney Transplantation: Current Landscape. Trials and Tribulations: Lessons Learned, and a Call for Reform. Am J Kidney Dis; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandraker A, Andreoni KA, Gaston RS, et al. Time for reform in transplant program-specific reporting: AST/ASTS transplant metrics taskforce. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(7):1888–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aubert O, Reese PP, Audry B, et al. Disparities in acceptance of deceased donor kidneys between the United States and France and estimated effects of increased US acceptance. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(10):1365–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchanan PM, Schnitzler MA, Axelrod D, Salvalaggio PR, Lentine KL. The clinical and financial burden of early dialysis after deceased donor kidney transplantation. J Nephrol Ther. 2012;8:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Englesbe MJ, Ads Y, Cohn JA, et al. The effects of donor and recipient practices on transplant center finances. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(3):586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Incerti D, Summers N, Ton TGN, Boscoe A, Chandraker A, Stevens W. The lifetime health burden of delayed graft function in kidney transplant recipients in the United States. MDM Policy Pract. 2018;3(1):2381468318781811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder RA, Moore DR, Moore DE. More donors or more delayed graft function? A cost-effectiveness analysis of DCD kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(2):289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarlagadda SG, Klein CL, Jani A. Long-term renal outcomes after delayed graft function. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15(3):248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez V, Galeano C, Diez V, Bueno C, Diaz F, Burgos FJ. Economic impact of the introduction of machine perfusion preservation in a kidney transplantation program in the expanded donor era: cost-effectiveness assessment. Transpl Proc. 2012;44(9):2521–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnitzler MA, Johnston K, Axelrod D, Gheorghian A, Lentine KL. Associations of renal function at 1-year after kidney transplantation with subsequent return to dialysis, mortality, and healthcare costs. Transplantation. 2011;91(12):1347–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chamberlain G, Baboolal K, Bennett H, et al. The economic burden of posttransplant events in renal transplant recipients in Europe. Transplantation. 2014;97(8):854–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.