Abstract

Background

Research indicates that the implicit biases and racist attitudes of healthcare workers are fundamental contributing factors to race-based health inequities. However, few studies and reviews appear to have examined the provision and effects of anti-racist education and training on post-licensure healthcare workers. The purpose of this systematic literature review was to explore what research methods are being used to ascertain the training healthcare workers are receiving post-licensure and to identify the goals and outcomes of this training.

Methods

Using PubMed, CINAHL, and Google Scholar databases, peer-reviewed articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified and reviewed by the authors from March through October of 2020 in alignment with the renewed national focus on anti-racism and racial justice. Studies or initiatives involving students were excluded as were commentaries on studies and studies not specific to racism or anti-racism.

Results

Eleven articles were identified as meeting stipulated inclusion criteria. Few were outcome studies (n = 3), and many articles did not clearly delineate training methods, content, or outcomes assessed. Identified methods included group discussion, case studies, and online modules. Reported outcomes included increased self-awareness of implicit biases and racism. Only two studies focused specifically on nurses, with the majority of studies centering on physicians (n = 5).

Conclusions

A considerable knowledge gap exists regarding effective methods, tools, and outcomes to use for undoing racism and mitigating bias in healthcare professionals. Nothing less than a seismic paradigm shift is called for, one in which an anti-racist perspective informs all healthcare education, research, and practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40615-021-01137-x.

Keywords: Implicit bias training, Anti-racism, Medical and nursing education

The deliberate misconstruction of race as a biological category is rooted in the US founding fathers’ use of race as justification for genocide and slavery [1, 2]. Simply put, race as a biological construct is a false determination. Despite this false construct and universal acknowledgement that race has no biological implications [3, 4], many disparities, including health disparities, can be directly linked to race and racism. Subsequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included racism in its list of social determinants of health/health inequities [4].

Unquestionably, structural and systemic racism embedded within the American healthcare system is a primary cause of race-based health inequities. One of the foremost and most recent examples of this is found in the severe maternal morbidity and mortality rates of Black women. A Black woman is 212% more likely to die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes than a White woman [5]. In a national study of five medical complications that are common causes of maternal death and injury, Black women were two to three times more likely to die than White women who had the same condition [6]. These statistics highlight an egregious imbalance that has persisted for decades. As discussed by Owens [7], the fathers of gynecology helped to perpetuate the myths that Black women do not experience pain and are immodest and hypersexual, thus supporting the fabrication of Blackness as erasure. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed race-based health disparities [8, 9] Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reveals that people of colour are hospitalized for COVID-19 at 4.7–5.3 times the rate of non-Hispanic White people [8]. In addition, Black people are almost twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as compared to White, non-Hispanic people. This is based on the CDC National Center for Health Statistics, 2021, which reports numbers as ratios of age-adjusted rates standardized to the 2019 US intercensal population estimate [10]. As Baptiste et al. [11], so cogently put it, “The American healthcare system inarguably fails Black people” (p.4416) and it could be argued, all people of colour.

Providing equitable, unbiased care is the responsibility of all clinicians. However, research and healthcare statistics indicate that the unconscious biases and racist attitudes of healthcare workers, specifically those of physicians and nurses, are a substantial contributing factor to health disparities, most significantly race-based health disparities [12]. Acknowledging social determinants of health and aspects of patient culture in medical and nursing school curricula does not adequately challenge the racist paradigms and biases of an overwhelmingly White healthcare workforce. In caring for increasingly diverse communities, the provision of safe, equitable care that does not perpetuate trauma and disparity is an ongoing issue for healthcare providers and organizations. How can healthcare providers mitigate such an intangible, historical, and pervasive aspect of clinical practice? We can start—as so many changes in clinical practice start—with education and training to both inform and heighten awareness of the insidiousness and effects of implicit biases and racism on provided care.

A substantial number of literature reviews and studies have addressed the issues associated with implicit bias and anti-racism education and training for nursing and medical students [13, 14]. In addition, there have been several articles that have explored the impact of cultural competency training for clinicians post-licensure [15]. However, it is important to note that cultural competency education and training may not specifically or significantly address anti-racism or implicit bias. In consideration of the aforementioned severe morbidity and mortality statistics disproportionately impacting Black women, we initially endeavoured to explore the impact of implicit bias and anti-racism education and training on the attitudes and behaviours of practicing perinatal nurses and physicians. However, we were unable to find sufficient literature with a clear focus on perinatal clinicians. Thus, the purpose of our systematic review was to answer the following questions:

What research methods and designs are used to explore the effects of bias and/or racism training and education for healthcare providers post-licensure?

How are healthcare providers being trained regarding undoing racism and bias, and fostering cultural competency, and what are the outcomes and/or goals of the training?

The purpose of this article is twofold. We will discuss the systematic review process, and also provide insight regarding some of the significant findings we encountered that we believe are inherent to the complexity of the chosen topic. This will include examining participants, interventions, comparison outcomes, and study design.

Methods

Literature Search

Our literature search was informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [16]. To that end, we searched databases that included peer-reviewed healthcare journals in English published within the previous five years that addressed interventions to educate perinatal healthcare providers about racism and implicit bias. Specifically, we searched PubMed, Google Scholar, and CINAHL. A list of databases and all terms used can be found in Table 1. Reference lists were also perused for possible studies and literature to be included in the systematic review. Reference lists yielded no additional studies. Due to the paucity of findings specific to perinatal clinicians, we expanded our inclusion criteria to include other healthcare professionals and their efforts to address undoing racism and implicit bias. The search was conducted from March 2020 through October of 2020. The interest in this time period was driven in part by the renewed national and global focus on the implications of racism and bias in healthcare that have been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, pervasive race-based health disparities, and racial injustices occurring across the USA.

Table 1.

Search terms by database

| Database | Search terms (indicates “AND” “OR”) |

|---|---|

|

PubMed |

(anti-racism) OR (racism) OR (implicit bias) AND toolkit OR programs OR training AND post-graduation OR post-licensure AND perinatal OR healthcare AND nursing OR physician OR physician residents |

|

Google Scholar |

(anti-racism) OR (racism) OR (implicit bias) AND toolkit OR programs OR training AND post-graduation OR post-licensure AND perinatal OR healthcare AND nursing OR physician OR physician residents |

|

CINAHL |

(anti-racism) OR (racism) OR (implicit bias) AND toolkit OR programs OR training AND post-graduation OR post-licensure AND perinatal OR healthcare AND nursing OR physician OR physician residents |

Study Selection

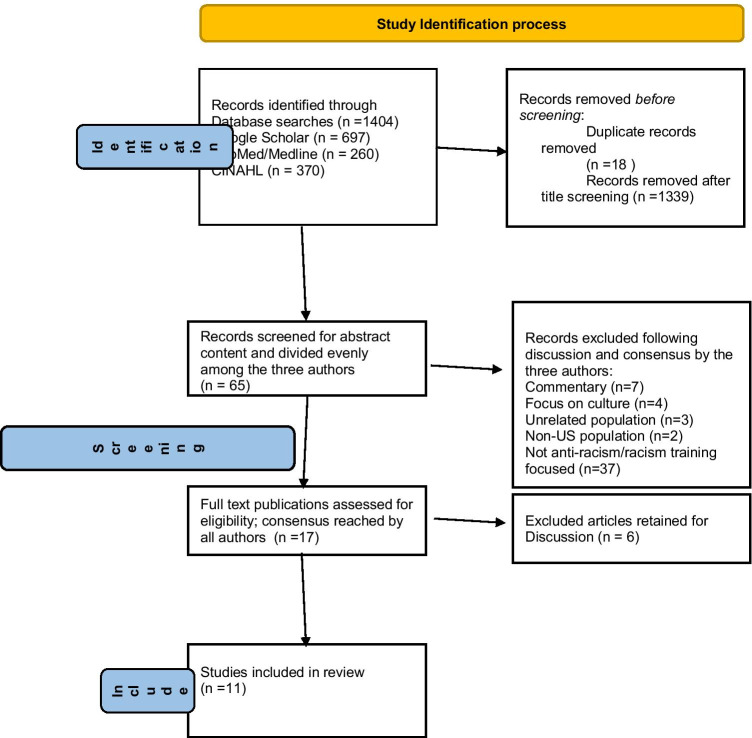

Our literature search yielded 1404 articles whose titles and abstracts were screened for relevance to our research topic of interest. Articles were divided evenly between the three authors. After eliminating duplicates and those that did not meet inclusion criteria, a total of 65 articles were initially identified as potentially useful in answering our research questions. The 65 articles were then divided evenly between the three authors. Any uncertainty about relevance or discrepancy was resolved by discussion and consensus of the three authors. This process is delineated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study Identification process

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria agreed upon were studies conducted in the USA within the previous 5 years (2015–2020), any healthcare discipline, programs directed at healthcare staff or associates, and peer reviewed (see Table 2 for additional details). Studies or initiatives involving students were excluded.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Publication type/study design | |

| Clinical research, randomized control trial, quasi-experimental, non-randomized control trials, qualitative research, opinions, systematic reviews, meta-analyses | Non-clinical research, narrative reviews, editorials, case reports, case studies, abstracts-only |

| Population | |

| Medical residents, fellows, attendings, nurses, nursing, other healthcare professionals, faculty, physicians | Students, research training, non-American setting |

| Intervention | |

| Focus on racism/anti-racism (historical, structural, personal, racial privilege), teaching, training, workshops, education, practical tips, curriculum outlined, development of modules, use of internet, use of lectures, discussion, role play, mindfulness training, case scenarios, reflection, cultural competence | Focus on stigma, non-racial implicit bias, theoretical presentation, cultural identity, exposure to interracial contact, advocacy, informal curriculum, course evaluation, development of empathy skills, teaching about health disparities, use of narratives |

| Outcomes | |

| Documented outcome(s) pertaining to increased awareness and knowledge of racial bias and intersection of multiple forms of discrimination, personal responsibility, self-reported skills | No limitations |

Quality Assessment

Of the 65 articles, each author was assigned an equal number of studies for a more in-depth review which were then entered into an Excel database. Categories used were citation; met inclusion criteria; reason for inclusion/exclusion in analysis; sample, setting, and specialty; education/training type/modality; outcome(s) assessed; outcome instruments; and major findings/conclusions. The authors then met to discuss their assigned articles. To verify entry into these categories, a second review was undertaken by a second author assigned to review a colleague’s prior application of inclusion/exclusion criteria. The results of the second look were again discussed amongst the three authors with agreement reached about final decisions for inclusion/exclusion in the analysis.

Analysis of the 65 articles first identified revealed that 11 publications met inclusion criteria and were useful in answering the research questions. Forty-eight articles were eliminated based on the exclusion/inclusion criteria (see Table 2). Six of the remaining articles were determined to be potentially informative for discussion purposes. The full-text articles were appraised for study design, intervention effects, generalizability, and clinical applicability. Tables 2, 3, and 4 provide an overview of study and program details and characteristics.

Table 3.

Article elements

| Author/year | Sample/targeted population | Purpose | Intervention | Design/control | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexis et al. (2019) [19] | N = 49 Faculty and Staff/Psych department faculty and staff | Raise awareness of race privilege | On-line training (reading essay, survey, open- ended questions) | Qualitative descriptive analysis/none | New insights (attitudes and behaviors that sustain racism) |

| Garneau et al. (2017) [3] | NA/nurses, nursing education/practice | Combat healthcare racism and discrimination | Critical anti-discriminatory pedagogy (CADP) | Theoretical discussion/none | None |

| Booker (2015) [22] | NA/Nurses and “other providers” | Improve pain management in Black Americans | “ASKED MYSELF” mnemonic | Commentary/none | None |

| Burgess et al. (2017) [33] | NA/Healthcare providers | Strategies to reduce provider ethnic and racial bias | Mindfulness and loving kindness meditation | Literature review/none | None |

| Burgess et al. (2019) [17] | N = 280/VHA providers | Motivating providers to address racial disparities | Surveys (provider identification with success or bias narratives) | Quantitative survey/yes | Identification with success narrative led to greater participation in disparities training |

| Crawford (2020) [34] | NA/Family physicians, APNs, RNs, other healthcare professionals | Explore biases which can affect practice decisions and actions | Integration of implicit bias training into health professional education | Training guide/none | Self awareness, understand how bias affects healthcare |

| FitzGerald et al. (2019) [35] | 30 articles/adult professionals (including healthcare personnel) | Effect of interventions to reduce bias measured by IAT | Effective implicit bias interventions | Systematic review/none | 8 categories; systematic evaluation of interventions; most useful was exposure to counterstereotypical exemplars |

| Hansen et al. (2018) [21] | NA/psychiatry residents | Understanding structural barriers to and impact on mental health | Structural competency training | Opinion/none | Understand structural nature of social determinants and effect on biology |

| Nelson et al. (2015) [18] | N = 19/Health Care Providers | Improving provider attitudes and confidence in caring for families of colour | Race/racism training module effectiveness | Quantitative/none | Provider awareness of race and racism |

| Perdomo et al. (2019) [2] | N = 66 (average), 463 total/Faculty, physician residents, fellows, attendings, and students | Curriculum identifying individual racial bias based on structural, historical racism; impact on health outcomes and how to mitigate the effects | Health equity rounds (HER); longitudinal case-based curriculum | Mixed methods/none | Awareness and self-reported skills |

| Sherman et al. (2019) [20] | N = 31/family physician residents and faculty | Provide insight regarding the impact of bias and racism on care; provider empowerment | Training workshops that address race and racism; focus groups | Mixed methods/none | Awareness and knowledge |

Table 4.

Study characteristics

| Domain | Category | N |

|---|---|---|

| Publication type | Peer reviewed | 11 |

| Publication date |

2015 2016–2017 2018–2019 2020 |

2 2 6 1 |

| Methodology |

Quantitative Qualitative Mixed |

2 1 2 |

| Study design |

RCT Randomized survey experiment Paired/matched Post only |

0 1 1 1 |

| Number of training hours |

< 5 6–10 |

2 2 |

| Number of participants (N) |

< 10 10–20 30–39 40–50 100 + |

0 1 1 1 2 |

| Targeted learners |

Multiple disciplines Nurses (all specialties) Physicians |

4 2 5 |

RCT randomized control trial

Results

Research Methods

Research Methods and Designs

Our first research question was “What research methods and designs are used to explore the effects of bias and/or racism training and education for healthcare providers post-licensure?” The majority of identified studies were omitted based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 11 articles were included in this analysis, although not all included clearly delineated outcomes. It is interesting to note that a majority of the journal articles did not delineate or identify a clear research question, design, or methodology. In addition, outcome studies were the exception and not the norm. Two of the outcome studies utilized quantitative methodology [17, 18], one study was qualitative [19], and two studies used mixed methods methodology [2, 20].

With a goal of answering the questions for this review, we recognized that our questions were not going to be easily or sufficiently answered by research studies. Thus, we made the decision to include articles and programs without clear or clearly delineated research design descriptions or methodologies. We surmised that including these types of articles would provide us with a better understanding of the training, education, and research gaps that exist, as well as give us foundational knowledge needed to foster future opportunities for the scientific investigation of these topics. For example, one article made no mention of specific study design, instruments or tools, but did indicate that their specific pedagogy could be foundational to future research and clinical interventions [3]. Another discusses the potential impact of mindfulness on implicit biases among physicians [17], while Hansen et al. [21] provides insight into the theoretical foundations and intersections of the curriculum they have designed to train psychiatry residents in appreciating the impact of social determinants of health on mental health and wellbeing.

Participants/Sample Characteristics

Two articles specifically targeted nurses [3, 22]. In her discussion of the disparity in pain management for Black Americans, Booker [22] makes it clear that the use of her framework could help improve the effectiveness of pain management for all healthcare providers and clinicians. Burgess [17] and her colleagues included nurse practitioners in their study’s sample. Physicians (including residents) were the most commonly used study participants or target audience (see Tables 3 and 4 for additional details). There were several articles that targeted multiple disciplines and healthcare personnel, but it was unclear what those specific roles were. According to Alexis et al. [19], “employees engaging in the (healthcare) system” is used to describe their sample (p. 30). The authors go on to indicate that all personnel, except for janitorial service workers, employed by the healthcare system where their study was conducted, were considered eligible participants. Among outcome studies, sample sizes ranged from 19 to 280 participants.

Curricular Content/Training Methods/Interventions

The second research question was, “How are healthcare providers being trained regarding undoing racism and bias, and fostering cultural competency, and what are the outcomes and/or goals of the training?” To answer this question, we reviewed each outcome article for insight into what curricular content and methods are being used to train study participants. Table 5 provides an overview of the curricular content and methods identified in the articles selected for this review. We did experience some challenges in ascertaining curricular content and methods from several of the selected articles. Further, there were several included articles and/or studies that did not include clearly delineated descriptions of training content or methods.

Table 5.

Curricular content and curricular methods with associated training outcomes for included studies

| Outcome assessed | n | Knowledge n = 1 |

Awareness n = 4 |

Self-reported skills n = 2 |

Objective skills n = 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curricular contenta | |||||

| Racism or discrimination | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Personal/racial attitudes, beliefs, or values | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Worldviews | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cultural Identity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bias/biases | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| White privilege/whiteness/privilege | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinician/client interactions | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Curricular methodsb | |||||

| Lecture | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Discussion | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Case scenarios | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Self-reflection | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Online training module | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| In-person training module | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Only studies that included specific outcomes are included here. Several studies included more than one outcome; several studies did not include outcomes

aThe n are the numbers of studies with specified curricular content

bThe n are the numbers of studies with specified curricular methods

Per the information provided from several of the articles regarding curricular content, we discovered a wide range of topics to include racism, discrimination, personal attitudes, beliefs and values, White privilege, implicit/unconscious bias, and client–clinician interactions. The details of the curricular content and methods were sometimes vague or omitted. Many articles presented general guidelines or only identified the conceptual framework they used to create their curriculum or training methods. In some instances, it was difficult to ascertain how much time was spent on each training component. As well, the modality in which the content or a specific topic was delivered was not always clearly delineated or discussed. The most commonly used curricular methods were group discussion, case studies, and online training modules.

Training Outcome Measures for Quantitative Studies

The second part of our second research question focused on the outcomes of goals of identified training. Of the 11 articles reviewed, five identified clearly delineated outcomes. Training outcomes varied and included increased self-awareness, racial attitudes, knowledge attainment, and self-reported skills like decision-making (see Table 5 for additional details). Burgess and her colleagues[17] conducted a survey experiment with random assignment in which the primary outcome was self-reported participation and engagement level with an online training course; secondary outcome measures (assessed using a follow up survey) included the assessment of intent to participate in designated activities post-intervention using 5-point Likert scale, the level of narrative identification using a 5-point Likert scale, and intentions to engage in disparity-reduction activities to designated responses. Providers were determined to identify most closely with the narrative that best reflected their belief about the source of bias in the interactions between Black patients and providers. Nelson, Prasad, and Hackman, [18] used anonymous survey results before and after a training intervention to assess the awareness of racism and its impact on care. The authors reported that the awareness and dismantling of previously held racist beliefs significantly increased in all participants and White participants demonstrated decreased self-efficacy when caring for patients of colour versus White patients.

Training Outcome Measures for Qualitative and Mixed-Method Studies

The one qualitative study [1] utilized a survey that consisted of one closed and two open-ended questions aimed at assessing attitudes and behaviours related to race and bias. According to the authors, some participants developed new insights into the personal attitudes and behaviours that perpetuate racial inequalities. Perdomo et al. [2] assessed self-reported skills using survey responses, while Sherman and associates [20] explored awareness and knowledge among family medicine physician residents 6 months post-training. Recognizing the challenge in objectively measuring changes in implicit bias, they decided that a qualitative exploration of implicit bias was most appropriate. The focus group questions “related to participants’ experiences within the training, impacts of the training on individual roles and on the broader residency program, and areas for growth related to implicit bias”(p. 678).

Discussion

From the systematic review, we discerned that there is a sizable gap in knowledge and consensus around effective methods, tools, and outcomes to be used to impact and measure the undoing of racism and the mitigation of bias among healthcare professionals. Anecdotes reported in the media affirm the need for clinicians and providers to listen to and seriously consider the concerns and symptoms reported by pregnant Black women or those who have recently given birth. Factors like educational attainment have not been found to protect Black women from pregnancy-related mortality [6], and it is important to note that this disparity in maternal death and harm is unique to Black women [23]. In consideration of the salient, severe morbidity and mortality statistics disproportionately impacting Black women, along with the fact that nurses are the largest group of healthcare providers and have the most frequent direct contact with patients/clients of any other healthcare providers [24], our original research questions and goal for this review focused on perinatal nurses and nursing.

Several studies included various healthcare providers, predominantly physicians. Our respective roles as perinatal nurse educator, nursing faculty, and nursing research scientist further supported the initial endeavour to explore the impact of implicit bias and anti-racism education and training on the attitudes and behaviours of practicing healthcare workers, specifically perinatal nurses. However, our literature search yielded no published articles specifically or clearly addressing racism or bias in the perinatal nursing setting nor in any nursing-specific setting. We found that Garneau et al. [3] was one of only two articles to specifically address nursing, though specific strategies or tools for undoing racism were not provided. Subsequently, we recognized the need to provide guidance for all healthcare professionals and revised the purpose of our systematic review accordingly.

Alexis et al. [19] examined online training aimed at raising individual awareness about attitudes and behaviours contributing to sustained racial health inequities. However, this did not occur for all individuals and the authors concluded a focus on systemic contributions to health disparities might be more productive. Burgess et al. [17] also implemented an online training program with self reporting of participant engagement in disparity reduction activities. However, there was no follow-up to determine the effects of the training. Likewise, improving providers’ understanding about healthcare equity in instances of racism was addressed by Nelson, Prasaad and Heckman [18]. Use of an extensive module served to significantly increase awareness about racism in healthcare but no long-term effects were noted. Finally, Pedromo [2], using case studies and self reported skills acquisition, reported increased participant awareness of implicit bias and structural racism. Participants indicated that the tools provided along with self-reflection would impact future clinical practice.

A vital step in conducting systematic reviews is establishing the criteria for evidence inclusion and exclusion. Researchers are tasked with (1) conducting a scientifically sound study and (2) publishing clear and concise information regarding the study’s design, methods, findings, and limitations. In recognition of the value and superiority of randomized control trials and robust study designs, the goal of our systematic search was to retrieve as many of these “gold standards” studies as possible [25]. However, we found few randomized control trials and actual research studies, and experienced difficulty locating published research studies with enough information. It is clear that there is a need to study the mechanisms, underpinnings, and pathways that contribute to or mitigate the impact of racism and implicit bias in healthcare. Robust, well-executed RCTs have the ability to test the efficacy of various interventions and create empirical evidence contributing to a standard of equitable care. These results, when used in conjunction with other sources of evidence, have the potential to build a body of research aimed at improving healthcare policy and evidence-based practice.

In an era when concern about racism’s effect on healthcare outcomes has resurfaced as a national public health priority, it is surprising that so little research has focused on best practices for long-term impact in undoing racism and mitigating implicit biases in the clinical setting. The publications we reviewed were aimed at enlightening participants at a specific moment in time through a workshop or through a series of encounters addressing anti-racism. Indeed, those few that measured outcomes were able to show participant reflection and changes in self awareness about racism and implicit bias. This perhaps is the overriding positive message. A workshop or a series of workshops may enlighten participants about their own biases, the root causes of racism, and provide tools for use in patient encounters. However, what is needed is a cultural and structural shift that embeds anti-racism in everyday clinical practice and policy. The authors would posit that an expanded body of research, to include RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, is critical to driving this level of transformative change. The process of cultural change is supported by the exploration of outcomes at both the patient- and system-level.

Cultural shifts are important in sustaining best clinical practice. For example, safety in the in-patient setting has become an overriding priority for nurses and the organizations that employ them. Nurses must monitor and record safety measures assessed and implemented. When an incident around safety occurs such as a fall, it must be reported and reviewed to determine if practice or policy needs to change. Nurses are required, usually on an annual basis, to review modules addressing safety and safety issues. These measures ensure patient safety and protect nurses from liability. Thus, a culture is maintained where safety issues can be openly addressed without fear of retribution.

A cultural shift regarding anti-racism and implicit bias would go a long way in protecting patients and demonstrating a commitment to undo racism in the clinical setting. Because cultural shifts are dynamic processes requiring direct and dynamic action and sustained self-reflection, the fostering of cultural humility within healthcare workers is imperative for the realization of a cultural shift away from implicit bias and toward an anti-racist approach to health care. A lifelong process [26], the cultivation of cultural humility involves self-reflection and self-critique [27] during patient encounters coupled with a resolve to be open to—and learn from—all patients regardless of cultural differences [27, 28]).

Additionally, research has shown that disproportionately high rates of trauma and adversity are experienced by marginalized groups [29]. Subsequently, the concept of historical trauma refers to unresolved, persistent trauma across generations of marginalized populations [30]. The impact of daily and historical trauma on the health of marginalized populations can be seen in the disproportionately higher rates of chronic stress conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and inflammatory disorders [31]. Hence, it seems prudent that healthcare organizations would not want to perpetuate or exacerbate these traumas. More importantly, healthcare workers must become formidable allies [30] of those patients who belong to marginalized groups in order to help mitigate the effects of trauma on their functionality and well-being.

Admittedly, this is an emotionally laden topic and not an easy one to address. This systematic review however demonstrated that a number of different methods can be used to increase knowledge and raise awareness of each individual’s implicit racial bias. The hope is that individuals will use this new found information to change and inform their practice. While this first step is needed, there is no evidence that in fact practice does change. Some have suggested that instead of a lengthy workshop on anti-racism, smaller, more frequent, smaller doses of anti-racism material are needed [32]. We would argue that in fact a sustained commitment to undoing racism in the clinical arena requires commitment by all, as well as a cultural shift.

Limitations

Despite our best efforts to conduct a comprehensive literature review for all articles relevant to our research topic and published during the designated time period, it is possible that pertinent articles may have been missed. Furthermore, we were unable to faithfully follow the PRISMA checklist (Addendum 2) as there were insufficient RCTs from which to extract data. Synthesis measures and statistics for groups are absent. Also, due to the inclusion of study designs with specific and inherent risks of bias, we did not examine risk of bias nor explicitly assess certainty. This review only included studies published in English about US populations; hence, additional evidence may have been published in other languages and countries. Lastly, having no knowledge of the practice, we did not register our review in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

Conclusions

The numerous stories that have circulated in the media and been made public about Black women and their birthing experiences is of deep concern [23]. These stories about healthcare provider dismissal or lack of concern regarding symptoms indicative of potentially life and death situations require critical examination. Together with statistics showing marked disparities between Black/White maternal morbidity and mortality and birth outcomes are red flags that something is seriously amiss. While acknowledgement has been made that structural racism and implicit bias are significant contributors to this grave situation, a road map for the solution is yet to be elucidated. In our systematic review, we found similarities and differences of approaches in training healthcare providers to recognize and implement strategies to mitigate the impact of implicit bias and build effective antiracist education initiatives. All studies highlighted participant awareness of implicit racial bias following training. Some studies referred to training that included historical factors or the role of structural racism or the power differential between whiteness and blackness. Knowing that one is the product of one’s society and inherently biased is a helpful first step in the long road to undoing personal racism. However, there is no guarantee that a one-time workshop will have lasting effects on a healthcare provider’s prescribed care or interpersonal interactions with patients. We agree that healthcare providers and especially the patient’s first contact, such as the perinatal nurse, need awareness raised about racial bias. Still to be determined are specifics about training: when, how often, session content, session length, follow-up, and evidence-based methods that foster long-term provider change. We suspect that training methods can only be one part of a comprehensive organizational commitment to a system where the expectation is equity of care. Such a system seeks to routinely identify racial bias and correct it within a community of individuals committed to ending racial injustice in the healthcare system.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of ATCORHE, as well as the academic and community leaders who provided inspiration and invaluable support for this work.

Author Contribution

The authors confirm equal contribution to all aspects of this manuscript, to include idea conception, design, analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Avant ND, Gillespie GL. Pushing for health equity through structural competency and implicit bias education: a qualitative evaluation of a racial/ethnic health disparities elective course for pharmacy learners. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11(4):382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perdomo J, Tolliver D, Hsu H, He Y, Nash KA, Donatelli S, et al. Health equity rounds: an interdisciplinary case conference to address implicit bias and structural racism for faculty and trainees. MedEdPORTAL Publ AAMC J Teach Learn Res. 2019;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garneau AB, Browne AJ, Varcoe C. Drawing on antiracist approaches toward a critical anti discriminatory pedagogy for nursing. Nurs Inq. 2018;25(1):e12211. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/10.1111/nin.12211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2020.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Freproductivehealth%2Fmaternalinfanthealth%2Fpregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed 07 April 2021.

- 6.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths — United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:762–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens DC. Medical Bondage: Race, gender, and the origins of American gynecology. 2017. The University of Georgia Press.

- 8.Marshall, W.F. III. Coronavirus infection by race: what’s behind the health disparities. 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/expert-answers/coronavirus-infection-by-race/faq-20488802. Accessed 07 Apr 2021.

- 9.Cooper LA. Racial data transparency: Q& A. 2021. John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/racial-data-transparency. Accessed 08 Apr 2021.

- 10.CDC National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) provisional death counts https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Deaths-involvingcoronavirus-disease-2019-COVID-19/ks3g-spdg. Accessed 06 Mar 2021.

- 11.Baptiste DL, Josiah NA, Alexander KA, Commodore-Mensah Y, Wilson PR, Jacques K, et al. Racial discrimination in health care: an “us” problem. J Clin Nur. 2020;29(23/24):4415–7. https://doi.org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/10.1111/jocn.15449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e60–76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad NJ, Shi M. The need for anti-racism training in medical school curricula. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1073. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnett A, Moorley C, Grant J, Kahin M, Sagoo R, Rivers E, Deravin L, Darbyshire P. Dismantling racism in education: In 2020, the year of the nurse & midwife, “it’s time.” Nurse Educ Today. 2020;2020(93): 104532. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:232. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Burgess DJ, Bokhour BG, Cunningham BA, Do T, Eliacin J, Gordon H, et al. Communicating with providers about racial healthcare disparities: the role of providers’ prior beliefs on their receptivity to different narrative frames. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson SC, Prasad S, Hackman HW. Training providers on issues of race and racism improve health care equity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:915–917. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexis C, White AM, Thomas C, Poweski J. Unpacking reactions to white privilege among employees of an academic medical center. J Cult Divers. 2019;26(1):28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherman MD, Ricco JA, Nelson SC, Nezhad SJ, Prasad S. Implicit bias training in a residency program: aiming for enduring effects. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):677–681. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.947255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen H, Braslow J, Rohrbaugh RM. From cultural to structural competency—training psychiatry residents to act on social determinants of health and institutional racism. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75(2):117–118. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Booker SQ. Are nurses prepared to care for Black American patients in pain? Nursing. 2015;45(1):66–9. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000458944.81243.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roeder A. America is failing its black mothers. Harvard Public Health. 2019. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/magazine/magazine_article/america-is-failing-its-black-mothers/. Accessed 07 June 2020.

- 24.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing Fact Sheet. 2019. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Fact-Sheets/Nursing-Fact-Sheet. Accessed 24 Mar, 2021.

- 25.Jones DS, Podolsky SH. The history and fate of the gold standard. Lancet. 2015;385:1502–1503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes V, Delva S, Mkimbeng M, Spaulding E, Turkson-Okran R-A, et al. Not missing the opportunity: strategies to promote cultural humility among future nursing faculty. J Prof Nurs. 2020;36(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferdinand KC. Overcoming barriers to COVID-19 vaccination in African Americans: the need for cultural humility. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(4):86–588. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foronda C, Baptiste D-L, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility. J Transcult Nurse. 2016;27(3):210–217. doi: 10.1177/1043659615592677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weitzel J, Luebke J, Wesp L, Graf MDC, Ruiz A, et al. The role of nurses as allies against racism and discrimination: an analysis of key resistance movements of our time. Adv Nurs Sci. 2020;43(2):102–113. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeffers NK. Association of Womens Health Obstetric and Neonatal Nursing 2020 Convention. Dismantling racism, saving moms and babies. A call to action: antiracism in nursing practice, education, and research. Accessed 31 Oct, 2020. https://awhonn2020.mpeventapps.com/session-virtual/?v26dd132ae80017cdaf764437c30ebe6f10c1b1eeaab01165e44366654b368dfaeab6baf7e386a642ecb238989334530e=4E4440AA75C20D3F5296C6FF20F5DAD36C6E9EEE1CDACB04DE0A428CC057E958F24F24C8FF642CF6E2063E401D012C72.

- 33.Burgess DJ, Beach MD, Saha S. Mindfulness practice: a promising approach to reducing the effects of clinician implicit bias on patients. Patient Edu Couns. 2017;100(2):372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford C. The everyone project unveils implicit bias training guide. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(2):182–183. doi: 10.1370/afm.2525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzgerald C, Martin A, Berner D, Hurst S. Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real world contexts: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.