Abstract

CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells (TRM cells) are essential for immune defence against pathogens and malignancies, and the molecular processes that lead to TRM cell formation are therefore of substantial biomedical interest. Prior work has demonstrated that signals present in the inflamed tissue micro-environment can promote the differentiation of memory precursor cells into mature TRM cells, and it was therefore long assumed that TRM cell formation adheres to a ‘local divergence’ model, in which TRM cell lineage decisions are exclusively made within the tissue. However, a growing body of work provides evidence for a ‘systemic divergence’ model, in which circulating T cells already become preconditioned to preferentially give rise to the TRM cell lineage, resulting in the generation of a pool of TRM cell-poised T cells within the lymphoid compartment. Here, we review the emerging evidence that supports the existence of such a population of circulating TRM cell progenitors, discuss current insights into their formation and highlight open questions in the field.

Subject terms: Immunological memory, CD8-positive T cells

CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells (TRM cells) are essential for defence against pathogens and malignancies. Prior work had indicated that these cells form within inflamed tissue, but there is emerging evidence that a pool of TRM cell precursors exists within the circulation. This Review examines the processes and signals within the lymphoid compartment that determine lineage decisions towards the formation of TRM cells.

Introduction

A fundamental aspect of CD8+ T cells is their ability to adapt to the type of pathogens encountered. First, through the process of clonal expansion upon antigen recognition, the T cell pool becomes biased to recognize pathogens that it has previously been exposed to1. Second, remodelling of the epigenetic landscape allows memory cells that are formed in this process to more rapidly exert effector functions2. Third, the distribution of the CD8+ T cell memory compartment over different body sites maximizes the chance of early pathogen recognition upon renewed infection3. In line with the concept that the CD8+ memory T cell pool can provide rapid effector functions and has the capacity for renewed clonal expansion, this cell pool is highly diverse at the epigenetic, transcriptional and protein expression levels. Specifically, within the circulation (that is, blood, lymph and secondary lymphoid organs) two main subgroups of CD8+ memory T cells can be distinguished, often referred to as CD8+ central memory T cells (TCM cells) and CD8+ effector memory T cells (TEM cells), which collectively form the pool of CD8+ circulating memory T cells (here jointly referred to as TCIRCM cells). TCM cells can be distinguished by high-level expression of the lymphoid homing markers CD62L and CCR7. They are considered to be multipotent and at least a subset of this cell pool display a heightened expansion potential upon antigen re-encounter4. By contrast, TEM cells possess limited expansion potential and lack the ability to enter lymph nodes from the blood, but are marked by expression of cytotoxicity-associated genes and can exert rapid effector functions upon renewed TCR signalling5. TEM cells were long believed to be superior in penetrating and surveying peripheral tissues; however, this idea has come under scrutiny as recent work has suggested that TEM cells and TEM cell-like cells are mostly excluded from human and mouse non-lymphoid tissues (NLTs)6–9.

In addition to the systemic CD8+ memory T cell pool, a pool of CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells (TRM cells) that permanently reside within NLTs can be distinguished. Through a process of continuous migration and surveillance that is confined to distinct anatomic compartments, such as the stroma or the parenchyma of organs, TRM cells patrol tissues to scan for foreign invaders10,11. Following antigen encounter, TRM cells rapidly induce a local state of alarm, resulting in the recruitment of other immune cells and the local production of antimicrobial and antiviral proteins by epithelial cells12,13. In line with this ‘pathogen alert’ function, TRM cells not only produce cytotoxicity-associated molecules, such as granzyme B and perforin, but also cytokines such as IFNγ and TNF that can influence the behaviour of neighbouring cells14–19. Furthermore, the existence of TRM cells that express minimal levels of cytolytic molecules, and may therefore mostly rely on this ‘pathogen alert’ function, has been reported in various human tissues20–23. Whereas TRM cells share transcriptional features with both TCM cells and TEM cells, they are unique in their expression of a tissue residency-promoting transcriptional signature, which marks TRM cells in a wide range of tissues. Besides this core tissue residency signature, TRM cells also display transcriptional features that are specific to individual tissues and allow their survival and long-term retention at those different sites24,25.

The residency signature that marks TRM cells in multiple tissues is characterized both by a reduced expression of proteins that promote tissue egress and a heightened expression of proteins that promote tissue retention. For instance, TRM cells show reduced expression of the cell-surface molecules S1PR1 and CCR7 that promote T cells to leave NLTs, an observation that is explained by a lowered expression of the transcription factor KLF2, which drives S1PR1 and CCR7 transcription26. On the other hand, TRM cells express CD69 and, in the case of TRM cells localized within epithelial tissues, the E-cadherin binding αE integrin (CD103, encoded by Itgae), which both promote tissue retention (for a comprehensive review of the molecular pathways that control tissue retention, please see ref.27). The expression of CD69 and CD103 should be considered imperfect markers to infer tissue residency, as absence of their expression does not rule out long-term tissue retention and presence of expression does not exclude the potential to leave NLTs28–32. Nevertheless, much of our current understanding of TRM cells is based on analyses of CD69+CD103+ TRM cells in epithelial tissues.

In line with their role as local sentinels, TRM cells have been shown to both prevent and exacerbate pathologies. For instance, TRM cells are not only superior to TCIRCM cells in conferring protection to recurring local pathogens33,34 but these cells can also provide protection against the development of skin malignancies35–37. Moreover, tumour infiltrating lymphocytes that strongly resemble conventional TRM cells have been associated with improved disease prognosis38,39. At the same time, TRM cells may drive immunotherapy-induced colitis40, the skin autoimmune disorders vitiligo41 and psoriasis42,43 and also other autoimmune and allergic diseases44, and may play a central role in allograft rejection45. The involvement of TRM cells in a range of human diseases makes the design of therapeutic strategies that can modulate either their production or their activity an attractive goal, and to realize this goal, it is critical to understand how the formation of this cell pool is regulated46. In this Review, we discuss the processes that drive the formation of the CD103+ epithelial TRM cell lineage, with a strong focus on signalling events that occur within the lymphoid compartment.

TRM cell precursors within NLTs

At an early stage of an antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response, infected tissues are seeded by CD8+ effector-stage T cells (TEFF cells); that is, activated T cells that can be observed around the peak of the expansion phase, regardless of their phenotype and function47. TEFF cells forming the first wave of T cells that can be detected at inflamed sites already show transcriptional differences relative to circulating T cells that are specific for the same antigen14,48. Differentially expressed genes are associated with a wide range of cellular functions, including cell adhesion, cytokine and chemokine signalling, co-stimulation and co-inhibition, and transcriptional regulation14,48. Interestingly, early TEFF cells present at the tissue site display increased expression of core TRM cell genes, and at the peak of the T cell response the T cell population present at the tissue site already expresses more than 90% of the gene signature that differentiates TRM cells from TCIRCM cells49. This illustrates that the initiation of a TRM cell differentiation process already occurs during early stages of the immune response.

Although the TEFF cells at tissue sites show a rapid transcriptional and phenotypic divergence from their circulating counterparts, these TEFF cells nevertheless do display the same diversity in cell states that has previously been described for circulatory TEFF cells. Specifically, within the circulating TEFF cell compartment, two cell states are commonly distinguished: the relatively short-lived terminal effector cells that express high levels of KLRG1, T-BET and BLIMP1 and show high cytotoxic potential; and the memory precursor cells that give rise to stable circulating memory T cell populations and are generally defined by an elevated expression of IL-7Rα, ID3 and TCF1 (ref.50). A similar dichotomy in phenotype and fate has been documented for the pool of TEFF cells within NLTs51–53. Furthermore, T cells in NLTs that resemble circulating terminal effector T cells fail to express the TRM-associated markers CD103 and CD69, and gradually perish over time51,52. On the contrary, T cells within NLTs that resemble memory precursor cells express CD103 and CD69, indicative of their potential to persist long term within the NLTs51,52. Interestingly, at very early stages of the immune response, before the appearance of cells with the terminally differentiated (KLRG1+IL-7Rα−) phenotype, two transcriptionally disparate subgroups of TEFF cells that differ in their differentiation potential can already be distinguished in the epithelium of the small intestine. Specifically, early effector T cells that are marked by high expression of IL-2Rα and EZH2, an epigenetic regulator known to modulate early effector T cell fate decisions54,55, are prone to give rise to KLRG1+ terminal effector T cell-like cells, in contrast to their EZH2lowIL-2RαLOlow counterparts that are superior in the generation of CD103+CD69+ TRM cells48.

Numerous signals that promote the differentiation of TRM cells within the tissue micro-environment have been described, and these signals presumably contribute significantly to the emergence of cells with TRM cell-like properties at the tissue site early during the immune response. For example, the presence of antigen56–60, IL-7 (ref.61), IL-15 (refs41,52,61–63) and TGFβ64,65 within the non-lymphoid micro-environment promote TRM cell differentiation in tissues such as the skin and lung. In particular, TGFβ is considered a central mediator of epithelial TRM cell differentiation as it can modulate the expression of many molecules that specifically mark TRM cells26,62,66,67. In line with this, T cells that are insensitive to TGFβ signalling lack the capacity to develop into CD103+CD69+ TRM cell precursors and TRM cells in many epithelial tissues51,57,66,68. Other T cell extrinsic factors that can influence TRM cell formation are TNF and IL-33 (refs26,66,69), which can induce CD69 and CD103 expression and suppress KLF2 expression, and IL-21, which has recently been identified to boost the formation of CD103+ brain TRM cells70. However, a critical issue that has not been fully settled is whether these various signals primarily modulate TRM cell fate at the inflamed tissue site or may also play a role in lineage instruction in the lymphoid compartment prior to tissue entry.

It is important to note that the signals driving the formation of TRM cells differ between epithelial tissue types. For instance, abrogation of T cell intrinsic TGFβ signalling results in impaired production of TRM cells in the lung, whereas the formation of TRM cells in the nasal cavity is unaffected71. Similarly, IL-15 signalling is required for TRM cell formation in some, but not all, tissues72. The idea that different routes to tissue residency exist is also supported by the observation that the transcription factor HOBIT promotes TRM cell development in the skin and small intestine, but is not required for lung TRM cell formation73,74. Collectively, these results strengthen the idea that the processes that yield TRM cells show a level of redundancy, and that environmental conditions can change the requirements for T cells to develop into TRM cells.

Models of TRM cell lineage divergence

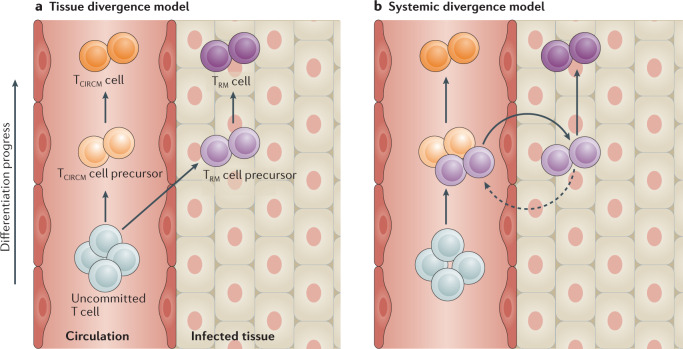

Based on the studies discussed above, it is apparent that the potential for TRM cell differentiation is already present in part of the TEFF cell population that is located within NLTs early during infection. However, these findings do not address whether this potential is induced only after tissue entry or is already present before that stage. An analysis of TRM cell-forming potential within the pool of activated circulating T cells has shown that cells with a memory precursor phenotype possess a superior potential to yield TRM cells, but this cell pool is also well equipped to yield TCIRCM cells49,52,75. The hypothesis that the circulating memory precursor cell pool can sprout both TRM cells and TCIRCM cells is compatible with two models for TRM cell generation. In the ‘local divergence’ model, the circulating memory precursor pool is proposed to consist of cells that are equal in their potential to contribute to both the TRM cell pool and the TCIRCM cell pool. Only upon stochastic tissue entry and subsequent encounter of local micro-environmental factors, such as TGFβ and IL-15, by a selection of memory precursor cells would these cells commit to the TRM cell lineage and adopt tissue residency (Fig. 1a). In other words, in this model, signals within the NLTs dictate TRM cell lineage commitment. In the alternative ‘systemic divergence’ model, events that occur prior to tissue entry, within the lymphoid tissue or in blood, already steer some memory precursor cells to their subsequent fate as TRM cells. In this model, a dichotomy in memory-forming potential would already be present within the circulating memory precursor cell pool, providing part of that pool with an enhanced capacity to migrate into inflamed tissue and/or respond to inflamed tissue-derived environmental factors that support TRM cell formation (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Models of TRM cell lineage divergence.

Branching of the CD8+ tissue resident memory T cell (TRM cell) lineage from the circulating T cell lineages can be explained by two models. a | The tissue divergence model postulates that memory precursors within the circulation are equal in their potential to give rise to CD8+ circulating memory T cells (TCIRCM cells) and TRM cells. Only upon reaching the tissue do cells undergo changes that skew them towards the TRM cell lineage, whereas those memory precursor T cells that remain in circulation start to differentiate into TCIRCM cell lineages. b | The systemic divergence model postulates the existence of memory precursors within the circulating T cell pool that are poised to produce the TRM cell lineage and these cells are superior in giving rise to TRM cells relative to other circulating memory precursors. Note that these models do not address whether a fraction of cells with reduced TRM cell-forming potential enter the tissue and later rejoin the circulation.

As described above, earlier work has identified numerous tissue-derived factors that can support TRM cell formation, and based on these observations it was generally assumed that the tissue micro-environment autonomously instructs TRM cell lineage decisions in uncommitted infiltrating memory precursor cells. However, numerous studies have subsequently identified factors within lymphoid tissues that are essential for the formation of the TRM cell lineage, but not the TCIRCM cell lineage. Furthermore, a combination of single-cell transcriptome analysis and lineage tracing allowed identification of the existence of a circulating effector T cell population that preferentially gives rise to TRM cells and transcriptionally resembles mature TRM cells76. These observations argue for a ‘systemic divergence’ model of TRM cell formation, in which the capacity to develop into TRM cells is at least partially driven by lymphoid-derived signals.

Skewed TRM cell production by naive T cells

A ‘systemic divergence’ model of TRM cell differentiation proposes that the propensity to give rise to this lineage of memory cells is at least partially imprinted prior to tissue entry. As TRM cell precursors can already be detected in tissues at an early stage of the T cell response, any systemic imprinting of TRM cell lineage decisions should therefore also occur prior to, or within the first few days following, T cell activation. Importantly, direct evidence that T cells undergo TRM cell fate conditioning/poising prior to substantial antigen-driven expansion has been obtained. Specifically, two studies have shown that naive T cells, either expressing variable77 or identical76 TCRs, show diversity in their ability to yield TRM cells and TCIRCM cells. This observed skewing of the progeny of individual T cells to either the TRM cell or TCIRCM cell lineage can conceptually be explained by differential exposure to signals that allow TRM cell formation by early progeny, or by a gentle ‘nudge’ towards the production of TRM cells that is already received at the naive T cell stage, prior to TCR triggering. Notably, evidence in favour of imprinting both during T cell priming and at the naive T cell stage has been obtained. With respect to the imprinting of TRM cell differentiation capacity during T cell priming, it is becoming increasingly evident that the specific dendritic cell subtypes that interact with T cells within lymphoid tissues can help steer early TRM cell differentiation. For instance, priming of human T cells by CD1c+CD163+ dendritic cells may preferentially induce TRM cell fate, as suggested by the observation that in vitro activation of naive T cells by CD1c+CD163+ dendritic cells, but not other dendritic cell subsets, induces the expression of a wide range of TRM cell-associated genes in human T cells, and endows cells with enhanced capacity to accumulate in human epithelial grafts in mice78,79. Furthermore, data obtained in mouse models have demonstrated that only priming by BATF3+ dendritic cells, a subgroup of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are efficient in antigen cross-presentation, allowed the formation of TRM cells in skin and lung tissue80. Interestingly, another study comparing terminal effector T cell versus TCIRCM cell differentiation in mice demonstrated that priming mediated by BATF3+ dendritic cells favours the production of terminal effector T cells and TEM cells over TCM cells, whereas CD11bhi dendritic cells, a subset that is poor at promoting TRM cell differentiation80, favoured TCM cell differentiation81. Although the above data indicate that BATF3+ dendritic cells can skew naive T cells towards both the TRM cell lineage and the TEM cell lineage, lineage-tracing data indicate that TRM cells and TEM cells are largely derived from distinct naive T cells76. This apparent contradiction may potentially be explained by an unappreciated diversity in TRM/TEM cell priming abilities within the BATF3+ dendritic cell lineage, or by naive T cell intrinsic variation in TRM cell-forming potential. The above data provide solid evidence that the nature of the APCs that induce T cell priming can influence their capacity to differentiate into TRM cells. In addition, evidence for such a ‘sculpting effect’ of dendritic cell encounters in the absence of antigen recognition has also been obtained. Specifically, migratory dendritic cells within lymph nodes have been reported to epigenetically reprogram naive T cells in the absence of inflammation, leading to a TRM cell-poised state that licenses naive T cells to preferentially give rise to skin TRM cells in response to local inflammation82.

The relative output of naive T cells towards either the TRM cell or TCIRCM cell pool after skin inflammation has been shown to be linked to the production of circulating TEFF cells with a TRM cell-like transcriptional signature by the progeny of individual cells76. It is plausible that encounter of the above-mentioned TRM cell-biasing dendritic cell subtypes prior to, and during, priming drives the creation of this specialized group of TEFF cells. However, a contribution of signals within NLTs in this process cannot be formally excluded. Specifically, late memory precursor cells that exist in skin 14 days after viral skin infection have been reported to locally receive TGFβ-induced signalling, after which these cells are able to rejoin the circulation64. It is presently unknown at what rate T cells egress from inflamed tissues at early stages of the immune response, and it will be of interest to determine whether, and to what extent, signals within NLTs can contribute to the production of the circulating TRM cell-poised T cell pool.

Molecular signals that induce a TRM cell-poised state

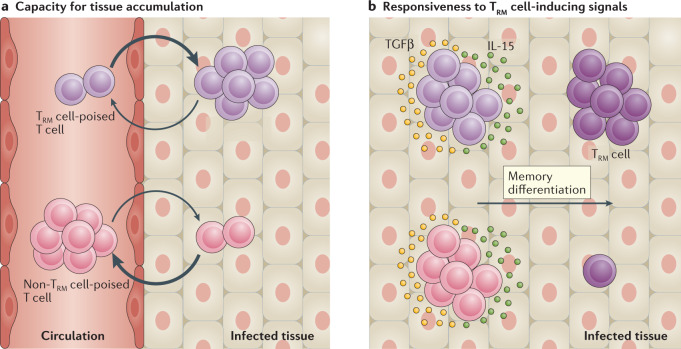

Signals provided by the dendritic cell subtypes described above may imprint an enhanced TRM cell-forming propensity in T cells by promoting two different biological properties. First, dendritic cell-derived signals may prime T cells for TRM cell fate by enhancing the ability of T cells to accumulate in tissues through either increased tissue entry or tissue retention (Fig. 2a); for instance, by driving heightened expression of relevant chemokine receptors83,84, integrins and other adhesion molecules27. Related to this, the observation that enhancement of tissue entry or inhibition of tissue egress increases the TRM cell pool size52,85 implies that migration and retention do represent bottlenecks in TRM cell generation. In addition, heightened expression of the chemokine receptors CCR8, CCR10 and CXCR6 by circulating TEFF cell clones responding to skin inflammation is associated with heightened TRM cell formation in the skin76. Second, signals provided by dendritic cells may also promote TRM cell lineage decisions by shaping an epigenetic and transcriptional landscape that makes cells commit more readily to the TRM cell lineage upon encounter of signals within the tissue micro-environment (Fig. 2b). Such variable responsiveness to TRM cell-inducing signals within the pool of TEFF cells is exemplified by the observation that exposure to TGFβ can either induce the expression of CD103 or induce apoptosis in some TEFF cells66,86.

Fig. 2. Properties of TRM cell-poised T cells.

Two properties endow CD8+ tissue resident memory T cell (TRM cell)-poised T cells with an enhanced capacity to form TRM cells. a | TRM cell-poised memory precursor cells are more prone to enter non-lymphoid tissues (NLTs) and are well equipped to persist within this tissue, compared with other T cells. b | TRM cell-poised memory precursor cells are more sensitive to signals, such as IL-15 and TGFβ, that drive TRM cell differentiation within inflamed tissues, and thus more readily give rise to mature TRM cells than other T cells that reach the tissue micro-environment.

Numerous signals within lymphoid tissues have been identified that help skew T cells towards the TRM cell lineage through either of the above-mentioned mechanisms. TGFβ, an immune modulator that promotes TRM cell formation by acting locally at the tissue site64,65, can also steer TRM cell differentiation within lymphoid tissues, both in the absence and the presence of infection. In the absence of foreign antigen, TGFβ activation by migratory dendritic cells in lymph nodes has been shown to induce epigenetic reprogramming of naive T cells, resulting in enhanced accessibility of signature TRM cell genes, such as Itgae and Ccr8, and to modulate the accessibility of target genes of transcription factors that are involved in TRM cell differentiation82. Such TGFβ-mediated conditioning of naive T cells was found to be essential for the differentiation of their progeny into TRM cells upon skin infection, but was dispensable for TCIRCM cell formation82. Notably, this TGFβ-dependent poising of naive T cells towards the TRM cell fate is reversible, implying that naive T cells require periodic TGFβ signalling to maintain their ability to differentiate into TRM cells. This suggests that naive T cells may vary in their TRM cell-poised state, depending on the level or frequency of prior TGFβ encounter, potentially explaining the clonal variation in TRM cell-forming capacity that has been observed76,77. Emerging tools that allow for the parallel determination of the epigenetic state of cells at a particular point in time and assessment of their ultimate fate at a later stage could be of major value to link epigenetic heterogeneity in the naive T cell pool to TRM cell differentiation potential87.

In the presence of foreign antigen, TGFβ has also been shown to promote the induction of a TRM cell-poised state. Upon TCR-mediated activation, T cells rapidly downregulate TGFβ receptor expression — perhaps to reduce the immunosuppressive effects of TGFβ — but regain expression around 24 h later88,89. Borges da Silva et al. have shown that such TGFβ receptor re-expression by TEFF cells in lymphoid tissues of mice is induced by P2RX7, an extracellular receptor that senses ATP. Interestingly, as a result of their insensitivity to TGFβ, P2rx7–/– early effector T cells in the spleen display diminished Itgae and elevated Eomes expression89, two characteristics that are negatively correlated with a TRM cell-poised state14,76, in line with the diminished TRM cell-forming capacities of these cells. It should be noted that lack of P2rx7 does not affect TGFβ receptor expression on naive T cells, suggesting that the TGFβ-mediated TRM cell fate conditioning that occurs prior to antigen encounter remains unaffected. Although the authors demonstrated that the lack of P2rx7 also negatively influenced the TRM cell pool size within the small intestine89,90, Stark et al. did not observe an effect of P2rx7 deficiency on TRM cell-forming capacity of T cells within the same tissue.91. As TGFβ signalling is vital for TRM cell differentiation in the gut51,68, mechanisms independent of the ATP–P2RX7 axis may exist that ensure TGFβ receptor re-expression.

A role for TGFβ in stimulating TRM cell differentiation during priming has also been described for human T cells. Specifically, the preferential induction of a TRM cell-like transcriptome by human CD11c+ dendritic cells marked by CD1c and CD163 expression has been explained by their ability to provide active TGFβ during T cell priming78,79. It is noted, however, that an inability of mouse CD11c+ dendritic cells to activate TGFβ during T cell priming does not impair mouse skin TRM cell development82, suggesting that the TGFβ signal that prepares cells for TRM cell fate during priming in mice is provided by another cell source.

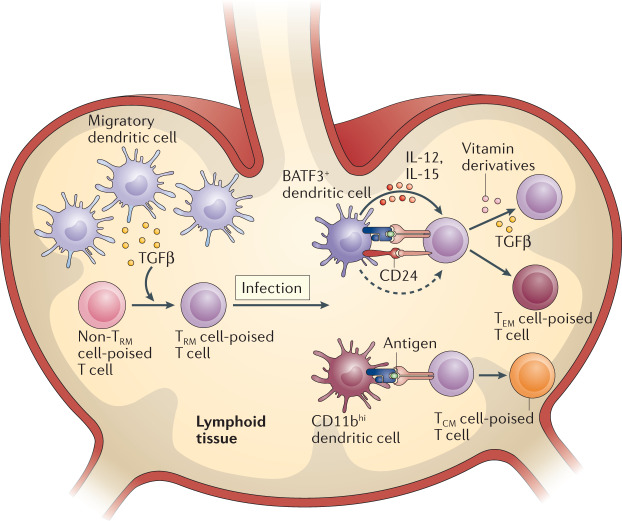

The cytokines IL-15 and IL-12, and the co-stimulatory molecule CD24 — three signals provided by BATF3+ dendritic cells during T cell priming — have been shown to be essential for the differentiation of mouse skin and lung TRM cells, whereas these signals are dispensable for TCIRCM cell formation80. However, how these signals promote TRM cell programming is less well understood. Similar to TGFβ, IL-12 drives the expression of CD49a (Itga1), a TRM cell-associated integrin that shows heterogeneous expression in circulating TEFF cells92, and of which elevated transcript levels mark TEFF cell clones with heightened capacity to form TRM cells76. Although CD49a is not required for the initial establishment of a TRM cell pool in the skin, the expression of this integrin is vital for long-term TRM cell persistence and locomotion92,93. Whether early-stage CD49a expression induced by lymphoid-derived TGFβ and IL-12 signalling affects the ability of mature TRM cells to persist in tissues is unclear. Both IL-12 and IL-15 have been shown to drive the activation of the mTORC1 protein complex94,95. This observation may explain the effect of these cytokines on TRM cell formation, as inhibition of mTORC1 activity during T cell priming reduces TRM cell formation due to a reduced ability of TEFF cells to migrate to the gut epithelium and to express CD103, while enhancing their ability to form TCIRCM cells95–97. Directly following T cell priming, T cells show variable levels of mTORC1 activity98, and it may be proposed that the level of mTORC1 activity may be used to identify T cells biased towards either the TRM cell or TCIRCM cell lineage. Although the exact mechanisms through which mTORC1 steers TRM cell fate decisions are unknown, it is plausible that mTORC1 and other downstream signalling molecules induced by IL-15, IL-12 and CD24 signals mediate TRM cell formation through the induction of molecular networks that also drive terminal effector and TEM cell lineage commitment. Specifically, studies focusing on the formation of circulating T cell subsets have shown that IL-12 (ref.99) and CD24 (ref.81), provided by priming dendritic cells, and elevated T cell intrinsic mTORC1 activity98 strongly favour terminal effector and TEM cell differentiation over TCM cell differentiation, suggesting substantial parallels between creation of the TRM cells and the terminally differentiated T cell lineages. Nevertheless, TRM cells display a significant level of multipotency32, highlighting that these cells cannot be considered terminally differentiated. TCM cell precursors are protected from terminal differentiation by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, which reduces their sensitivity and exposure to inflammatory stimuli100. By analogy, it may be speculated that periodic TGFβ signalling in lymphoid tissues could ‘rescue’ TRM cell-poised TEFF cells from terminal differentiation. In such a model, TRM cell-forming potential is coupled to the prevention of terminal differentiation of cells that would otherwise contribute to the TEM cell and terminal effector cell pools (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Signals within lymphoid tissues that poise T cells towards TRM cell development.

Overview of signals within lymphoid tissues that affect the ability of T cells to form CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells (TRM cells) in mouse models. Prior to antigen encounter, naive T cells require periodic TGFβ signalling to adopt and retain a TRM cell-poised state. Upon infection, priming by BATF3+ dendritic cells, which provide IL-15, IL-12 and CD24 signalling, biases T cells to form TRM cells. Presence of tissue-derived factors, such as derivatives of vitamin A and vitamin D, during priming can stimulate the expression of tissue-specific homing molecules, thereby guiding TRM cell-poised T cells to the relevant affected tissues. The presence of TGFβ during priming further maintains the TRM cell-poised state, and it may be proposed that in the absence of TGFβ, T cells primed by BATF3+ dendritic cells are prone to give rise to the CD8+ effector memory T cell (TEM cell) and terminal effector T cell lineages. TCM cell, CD8+ central memory T cell.

In addition to cytokines and co-stimulatory signals, metabolites that are synthesized in processes mediated by dendritic cells also play a major role in promoting TRM cell formation, by driving the expression of tissue homing molecules. Specifically, work over the past years has demonstrated that the expression of certain homing markers on T cells is influenced by the route of pathogen entry into the body64,101–103 and that this effect is, at least partly, due to a variation in availability of molecular compounds that can be processed by dendritic cells at different lymphoid tissue sites. For example, dendritic cells can metabolize vitamin D3 — a compound that is abundantly present in the skin — into its active form, and this metabolite suppresses the gut-homing programme in T cells, at the same time as inducing the expression of the chemokine receptor CCR10 that allows skin homing104. Vice versa, dendritic cells located in gut-associated lymphoid tissue can convert vitamin A into retinoic acid, thereby driving T cell expression of the gut-homing molecules CCR9 and α4β7 (refs105,106). Collectively, these data illustrate that the differential encounter of cytokines, co-stimulatory molecules and metabolites within lymphoid tissues can induce a bias with regards to the TRM cell-forming potential within the TEFF cell pool (Fig. 3). In addition, the idea that the molecular signals present at various priming sites can differentially affect the nature of TRM cell-poised T cells implies that recently activated T cells are not primed as a ‘universal’ TRM cell precursor but are primed to form TRM cells at specific anatomical sites.

Transcriptional regulation

Although it is clear that T cells can undergo conditioning that increases their potency to develop into TRM cells at very early stages of the immune response, while still located in lymphoid tissues80,82,96, the transcriptional programmes that underpin this heightened potential have not been identified. Notably, multiple transcription factors have been described that coordinate the development of TRM cells, and to better understand how TRM cell lineage conditioning is regulated within lymphoid tissues, it is useful to examine whether the transcription factors that are known to affect TRM cell development could be regulating TRM cell differentiation already prior to tissue infiltration.

T-bet (encoded by Tbx21), EOMES (Eomesodermin, encoded by Eomes) and TCF1 (encoded by Tcf7) are transcription factors that are abundantly expressed by subsets of circulating T cells but are not or are only minimally expressed by TRM cells in NLTs17,52,62,107. Early poising towards TRM cell fate is associated with the expression of T-bet80, and mature TRM cells also require low-level T-bet expression to allow IL-15 receptor cell surface expression62,108. However, higher levels of T-bet negatively affect TGFβ receptor expression and, hence, the ability of T cells to form CD103+ TRM cells62,109,110. Similarly, EOMES is essential for TCIRCM cell formation108,111 but also counteracts the generation of TRM cells by reducing the expression of the TGFβ receptor62. TCF1 is a transcriptional regulator that coordinates early fate decisions in response to both acute112 and chronic113,114 infections. It can block TGFβ-induced CD103 expression through direct interaction with the Itgae locus, and ablation of this transcription factor enhances the formation of lung TRM cells in mouse models115. The observation that circulating TEFF cell clones poised for TRM cell fate display diminished expression of these three transcription factors76 suggests that the levels of T-bet, EOMES and TCF1 may control early-stage TRM cell lineage decisions within the lymphoid compartment. As a side note, TGFβ signalling suppresses the expression of these three transcription factors62,115, and IL-12 signalling can induce transcriptional repression of both Eomes and Tcf-7 (refs94,116,117). In humans, evidence for the existence of a circulating pool of TRM cell-poised TEFF cells, marked by diminished expression of the aforementioned transcription factors as observed in mice76, is currently lacking. However, data sets describing single-cell gene or protein expression of large numbers of CD8+ T cells in the blood of human subjects who have been recently infected or vaccinated could serve as valuable resources to study their presence118–120. Mathew et al. described a pool of cycling EOMESlowTBETlowTCF1low T cells that were enriched in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, compared with healthy individuals or individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 (ref.119). To test whether this CD8+ T cell population harbours heightened TRM cell-forming capacity in humans, it would be interesting to match the TCR repertoire of this cell pool to that of other blood-derived TEFF cell subsets and to the TCR repertoire of mature TRM cells derived from tissue biopsies.

In addition to the transcription factors that repress TRM cell differentiation, numerous transcriptional regulators including RUNX3, BLIMP1 and its homologue HOBIT, BHLHE40, and NR4A1 have been shown to positively influence TRM cell formation. Although RUNX3 has also been shown to promote TCIRCM cell generation, ablation of RUNX3 affects the TRM cell pool more severely than the TCIRCM cell pool49,121. Additional evidence for a dominant role of RUNX3 in the generation of the TRM cell subset over the TCIRCM cell pool comes from the observations that TEFF cells in tissues display increased expression of RUNX3 compared with circulating TEFF cells48, and that forced expression of RUNX3 in activated T cells results in increased expression of core TRM cell signature genes and decreased expression of TCIRCM cell-related genes49. As RUNX3 has been shown to influence gene expression in recently primed T cells121, it is plausible that RUNX3 already aids TRM cell formation at a very early stage of the immune response, prior to tissue entry.

BLIMP1 promotes TRM cell formation in various tissues, in part by directly suppressing the expression of Tcf7 as well as by suppressing Klf2, Ccr7 and S1pr174, genes that encode proteins that promote tissue egress, thereby inhibiting the formation of the TCM cell lineage73. Although genetic deletion of Blimp1 diminishes TRM cell formation in the lung, it does not affect the number of TRM cells in the gut and skin, potentially due to activity of the BLIMP1 homologue HOBIT, which shares the ability to suppress the expression of tissue egress-promoting genes74. However, gut TRM cells that do form in the absence of BLIMP1 are defective in granzyme B production122, highlighting that BLIMP1 is important to support the acquisition of some aspects of TRM cell function. With respect to a potential role of BLIMP1 in determining TRM cell fate in the circulating T cell pool, we note that circulating TEFF cell clones with enhanced TRM cell-forming capacity are marked by elevated transcript levels of Gzmb, which encodes granzyme B, relative to other memory precursor cells76. As BLIMP1 is an essential driver of Gzmb expression within the circulating TEFF cell pool122,123, this relationship may conceivably reflect a moulding of the circulating TEFF cell population into a TRM cell-poised state by BLIMP1. In support of this hypothesis, dendritic cell-derived IL-15 and IL-12 within lymphoid tissues are required to induce a TRM cell-poised state80 and these signals are also known drivers of BLIMP1 expression in early effector T cells95,123. Within the mouse CD8+ T cell lineage, Hobit is highly expressed by TRM cells, but not or only minimally by TCM cells and TEM cells74,124. Whether circulating mouse effector T cells at any stage express HOBIT has not been reported. On the other hand, abundant expression of HOBIT has been described in circulating human effector-like T cells17,125–127, but unlike in mouse TRM cells, HOBIT does not prominently mark human TRM cells17,128. Thus, whether HOBIT plays a role in both mouse and human TRM cell formation prior to tissue entry remains undefined.

Marked expression of the transcriptional regulators BHLHE40 and NR4A1 has been observed in TEFF cells in tissues and in mature TRM cells in both mice and humans, and genetic deletion of these factors selectively hinders the formation of TRM cells in mice49,129,130. In addition, NR4A1 expression has been reported within the circulating pool of CD8+ TEFF cells, where it functions as a suppressor of cell division and effector differentiation131–133. BHLHE40 expression has been observed within the pool of effector CD4+ T cells134,135, but BHLHE40 expression by circulating CD8+ TEFF cells is less well described. More research is required to investigate whether BHLHE40 and NR4A1 are involved in TRM cell lineage decisions within lymphoid tissues or selectively act once T cells have seeded affected tissues.

Although differential expression of transcription factors, such as T-bet and RUNX3, is likely to form a major driver of TRM cell lineage divergence, target gene accessibility is thought to represent a second layer of control. TRM cells are characterized by a distinct epigenetic state as compared with TEM cells and TCM cells25,31,32,38, and differences in the epigenetic landscape are already apparent at the TRM precursor cell stage. For instance, a distinct set of RUNX3 target genes are accessible in TEFF cells localized in the gut epithelium and in the spleen of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-infected mice49. Notably, an enhanced RUNX3 target gene accessibility has been described in TRM cell-poised naive T cells, coinciding with a reduced accessibility of T-box target genes82. Furthermore, RUNX3 has been reported to induce global chromatin changes shortly after T cell activation, enhancing accessibility of BLIMP1 target sites and also inducing BLIMP1 expression121. Together, these data suggest a mechanism for early TRM cell lineage poising that relies on both the expression of certain transcriptional regulators and the increased accessibility of their target genes.

TRM cell precursors during reinfection

The data described above document the existence of circulating T cells that are poised to give rise to TRM cells after a primary infection. Remarkably, recent studies have uncovered that a similar population can also be detected upon recurring infection; however, these cells have a different origin. Upon local reinfection, TRM cells can proliferate — and whereas part of the offspring remain at the tissue site136,137, some of these cells may leave the tissue site. In addition to the observation that such ‘ex-NLT’ TRM cell offspring can take up permanent residence in tissue draining lymph nodes30,138, a recent study revealed that skin TRM cell-derived TEFF cells that are marked by the TRM cell-associated proteins CD103 and CD49a can be detected within the circulation32. Furthermore, it was shown that the offspring of intravenously transferred TRM cells possesses a high propensity to home to the tissue of origin and to again differentiate into resident memory cells upon infection. Combined, these observations suggest that TRM cell-derived offspring that naturally egress from tissues may also be primed to again form TRM cells32. Evidence that TRM cells can produce circulating offspring that possess a heightened potential to again form TRM cells has also been obtained in two other studies. Work by Behr et al. demonstrated that gut-derived TRM cells that were engrafted into liver tissue produced circulating TEFF cells upon LCMV infection, which preferentially formed TRM cells in gut tissue124. Furthermore, Klicznik et al. demonstrated that CD4+ tissue resident memory T cells derived from human skin xenografts can egress from the tissue, form CD103+ circulating T cells and, subsequently, form tissue resident memory T cells at distant skin tissue sites139. It has not been resolved which factors drive the re-entry of a selection of TRM cell-derived offspring into the circulation. Conceivably, the type or activation state of the APCs encountered locally could play a critical role in this process, as distinct types of APCs can differentially affect the gene expression profile of activated TRM cells, including genes involved in tissue egress140.

Concluding remarks

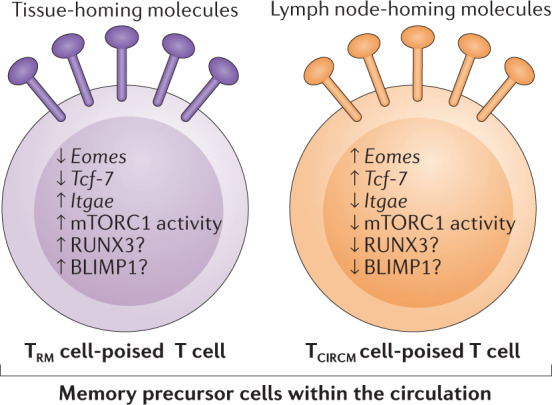

It has become increasingly clear that cues within lymphoid tissues can condition T cells, at the level of both naive and early effector T cells, to preferentially develop into TRM cells, and the presence of TRM cell-poised T cells within the circulating memory precursor cell pool reflects the result of these processes (Fig. 4). It is of interest to note that evidence supporting the existence of a circulating precursor population in lymphoid organs that has an increased propensity to take up residence in NLTs is not restricted to the CD8+ T cell compartment. Specifically, recent work has revealed the existence of CD4+ regulatory T cells within lymphoid tissues that epigenetically and transcriptionally resemble regulatory T cells within NLTs, and such cells are fated to traffic to NLTs and, subsequently, take up residency in peripheral tissue141–143. As the molecular mechanisms used to instruct a ‘tissue fate’ in different subsets of circulating leukocytes are likely to share common themes, the parallel study of residency promoting and inhibiting programmes in different cell subsets may be attractive.

Fig. 4. Distinguishing characteristics of TRM cell-poised memory precursor cells within the circulation.

Circulating CD8+ tissue resident memory T cell (TRM cell)-poised and CD8+ circulating memory T cell (TCIRCM cell)-poised memory precursor T cells share the classical memory precursor phenotype IL-7RαhiKLRG1low. However, numerous other properties could be used to distinguish the two groups of memory precursor cells76,82,89,96. Arrows depict relative level of activity or expression. Data on BLIMP1 and RUNX3 are indirect.

The processes that are involved in the creation of the circulating TRM cell-poised T cell pool will, at least partly, differ depending on the route of infection. Specifically, a number of the molecular and cellular cues that induce a TRM cell-poised state within lymphoid tissues find their origin in the associated NLTs (for example, CD103+ migratory dendritic cells, vitamin D, vitamin A)80,82,144. The importance of such crosstalk may also be reflected by the fact that no T cells that transcriptionally mimic TRM cells were detectable within the circulating TEFF cell pool after systemic LCMV infection48. It should be noted, however, that TRM cells do form in various NLTs following systemic LCMV infection, indicating that although tissue-derived signals present at the priming site may promote TRM cell formation, such signals are not always essential. In future work, it will be valuable to compare the formation of, and properties of, circulating TRM cell precursors in response to local infections at different tissue sites, to better understand the role of different tissue cues in the creation of this cell pool.

As a final area of future research, our current understanding of TRM cell fate conditioning within lymphoid tissues is predominantly based on work that tests the contribution of individual signals at a particular point in time, through the use of mouse models that are deficient in such signals. It will be attractive to complement this type of perturbation studies with studies that record the signals that cells receive, to test which signals are most predictive of future cell fate. Although a comprehensive monitoring of signalling events and subsequent changes in epigenetic and transcriptional states is unlikely to become feasible in the coming years, numerous previously established or recently developed tools will be valuable for this purpose. Specifically, methods that record — preferably quantitatively — the historic exposure to external signals, such as CRISPR-based approaches that induce genomic modifications upon the reception of a signal of interest145, are likely to serve as a useful approach to monitor the relationship between early signals and subsequent TRM cell formation. Similarly, the use of reporter systems in which the expression of genes of interest leads to stable genetic or protein marks75,124 could provide insights into the gene expression profile that marks TRM cell precursors before they reach the tissue site. Finally, a recently developed transposon-based tool that ‘immortalizes’ the pattern of historic interactions of transcription factors with available DNA target sites87 may be of significant value to the epigenetic state of early effector T cells to the memory T cell state they assume later on.

Glossary

- CD8+ central memory T cells

(CD8+ TCM cells). CD8+ memory T cells with a high degree of proliferative potential upon reactivation, commonly identified by the expression of lymphoid homing marker CD62L, and that can be abundantly found in the spleen, blood and lymph nodes.

- CD8+ effector memory T cells

(CD8+ TEM cells). CD8+ memory T cells with a high degree of cytotoxicity upon reactivation, which are commonly identified by the lack of CD62L expression, and that can be abundantly found in the spleen and blood.

- CD8+ circulating memory T cells

(CD8+ TCIRCM cells). A collective term for all of the CD8+ memory T cells that can circulate through the body and that are predominantly found in the blood, spleen and lymph nodes; the TCIRCM cell population encompasses both the CD8+ central memory T cell (TCM cell) and the CD8+ effector memory T cell (TEM cell) lineages.

- CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells

(CD8+ TRM cells). CD8+ memory T cells that, under steady-state conditions, are consistently excluded from the circulation and reside in tissues; TRM cells in mucosal tissue, such as the lung, gut and skin, are typically identified as CD103+CD69+.

- CD8+ effector-stage T cells

(CD8+ TEFF cells). All activated CD8+ T cells present around the peak of the expansion phase elicited by infection or vaccination, regardless of phenotype or function.

- Lymphoid tissues

A collective term for the thymus, bone marrow, lymph nodes and spleen; in this Review, this term predominantly refers to spleen and lymph nodes.

- Fate conditioning/poising

Enhancing the intrinsic capacity of a cell to give rise to a particular cell lineage through the induction of epigenetic and/or transcriptional changes.

- TRM cell-poised state

A state that skews the differentiation potential of T cells towards the tissue resident memory T cell (TRM cell) lineage.

Author contributions

L.K. researched data for the article. L.K. and T.N.M. discussed content and wrote the initial concept. L.K., D.M. and T.N.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks Benjamin A. Youngblood and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Obar JJ, Khanna KM, Lefrançois L. Endogenous naive CD8+ T cell precursor frequency regulates primary and memory responses to infection. Immunity. 2008;28:859–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdelsamed HA, Zebley CC, Youngblood B. Epigenetic maintenance of acquired gene expression programs during memory CD8 T cell homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:6. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jameson SC, Masopust D. Understanding subset diversity in T cell memory. Immunity. 2018;48:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gattinoni L, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson JA, McDonald-Hyman C, Jameson SC, Hamilton SE. Effector-like CD8+ T cells in the memory population mediate potent protective. Immun. Immunity. 2013;38:1250–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlach C, et al. The chemokine receptor CX3CR1 defines three antigen-experienced CD8 T cell subsets with distinct roles in immune surveillance and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;45:1270–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborn JF, et al. Enzymatic synthesis of core 2 O-glycans governs the tissue-trafficking potential of memory CD8+ T cells. Sci. Immunol. 2017;2:eaan6049. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aan6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buggert M, et al. The identity of human tissue-emigrant CD8+ T cells. Cell. 2020;183:1946–1961.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thome JJC, et al. Spatial map of human T cell compartmentalization and maintenance over decades of life. Cell. 2014;159:814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dijkgraaf FE, et al. Tissue patrol by resident memory CD8+ T cells in human skin. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:756–764. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariotti S, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells continuously patrol skin epithelia to quickly recognize local antigen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:19739–19744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208927109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ariotti S, et al. Skin-resident memory CD8+ T cells trigger a state of tissue-wide pathogen alert. Science. 2014;346:101–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1254803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schenkel JM, et al. Resident memory CD8 T cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science. 2014;346:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1254536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Y, et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature. 2017;543:252–256. doi: 10.1038/nature21379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masopust D, Vezys V, Wherry EJ, Barber DL, Ahmed R. Cutting edge: gut microenvironment promotes differentiation of a unique memory CD8 T cell population. J. Immunol. 2006;176:2079–2083. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoekstra ME, Vijver SV, Schumacher TN. Modulation of the tumor micro-environment by CD8+ T cell-derived cytokines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021;69:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2021.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hombrink P, et al. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8+ lung-resident memory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:1467–1478. doi: 10.1038/ni.3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Q, et al. Cutting edge: characterization of human tissue-resident memory T cells at different infection sites in patients with tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinbach K, et al. Brain-resident memory T cells represent an autonomous cytotoxic barrier to viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:1571–1587. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiniry BE, et al. Predominance of weakly cytotoxic, T-betLowEomesNeg CD8+ T-cells in human gastrointestinal mucosa: implications for HIV infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1008–1020. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiniry BE, et al. Differential expression of CD8+ T cell cytotoxic effector molecules in blood and gastrointestinal mucosa in HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 2018 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidel JA, et al. Skin resident memory CD8+ T cells are phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating populations and lack immediate cytotoxic function: phenotype and function of cutaneous T cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018;194:79–92. doi: 10.1111/cei.13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smolders J, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells populate the human brain. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4593. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frizzell H, et al. Organ-specific isoform selection of fatty acid-binding proteins in tissue-resident lymphocytes. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:eaay9283. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay9283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayward SL, et al. Environmental cues regulate epigenetic reprogramming of airway-resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:309–320. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0584-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skon CN, et al. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:1285–1293. doi: 10.1038/ni.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller SN, Mackay LK. Tissue-resident memory T cells: local specialists in immune defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:79–89. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh DA, et al. The functional requirement for CD69 in establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells varies with tissue location. J. Immunol. 2019;203:946–955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinert EM, et al. Quantifying memory CD8 T cells reveals regionalization of immunosurveillance. Cell. 2015;161:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beura LK, et al. T cells in nonlymphoid tissues give rise to lymph-node-resident memory T cells. Immunity. 2018;48:327–338.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buggert M, et al. Identification and characterization of HIV-specific resident memory CD8+ T cells in human lymphoid tissue. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3:eaar4526. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseca R, et al. Developmental plasticity allows outside-in immune responses by resident memory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:412–421. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0607-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang X, et al. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ TRM cells providing global skin immunity. Nature. 2012;483:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebhardt T, et al. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enamorado M, et al. Enhanced anti-tumour immunity requires the interplay between resident and circulating memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:16073. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park SL, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells promote melanoma-immune equilibrium in skin. Nature. 2019;565:366–371. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0812-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strickley JD, et al. Immunity to commensal papillomaviruses protects against skin cancer. Nature. 2019;575:519–522. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1719-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of tissue-resident memory T cells in human lung cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:2128–2149. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer (kConFab) et al. Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat. Med. 2018;24:986–993. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luoma AM, et al. Molecular pathways of colon inflammation induced by cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2020;182:655–671.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richmond JM, et al. Antibody blockade of IL-15 signaling has the potential to durably reverse vitiligo. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10:eaam7710. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurihara K, Fujiyama T, Phadungsaksawasdi P, Ito T, Tokura Y. Significance of IL-17A-producing CD8+CD103+ skin resident memory T cells in psoriasis lesion and their possible relationship to clinical course. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2019;95:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallais Sérézal I, et al. A skewed pool of resident T cells triggers psoriasis-associated tissue responses in never-lesional skin from patients with psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019;143:1444–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark RA. Resident memory T cells in human health and disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:269rv1–269rv1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Leur K, et al. Characterization of donor and recipient CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells in transplant nephrectomies. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5984. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dijkgraaf FE, Kok L, Schumacher TNM. Formation of tissue-resident CD8+ T-cell memory. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a038117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masopust D, et al. Dynamic T cell migration program provides resident memory within intestinal epithelium. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:553–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurd NS, et al. Early precursors and molecular determinants of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T lymphocytes revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:eaaz6894. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milner JJ, et al. Runx3 programs CD8+ T cell residency in non-lymphoid tissues and tumours. Nature. 2017;552:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature24993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaech SM, Cui W. Transcriptional control of effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:749–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheridan BS, et al. Oral infection drives a distinct population of intestinal resident memory CD8+ T cells with enhanced protective function. Immunity. 2014;40:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackay LK, et al. The developmental pathway for CD103+CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/ni.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Milner JJ, et al. Heterogenous populations of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells are generated in response to infection and malignancy. Immunity. 2020;52:808–824.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray SM, Amezquita RA, Guan T, Kleinstein SH, Kaech SM. Polycomb repressive complex 2-mediated chromatin repression guides effector CD8+ T cell terminal differentiation and loss of multipotency. Immunity. 2017;46:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kakaradov B, et al. Early transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of CD8+ T cell differentiation revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:422–432. doi: 10.1038/ni.3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muschaweckh A, et al. Antigen-dependent competition shapes the local repertoire of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:3075–3086. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakim LM, Smith J, Caminschi I, Lahoud MH, Villadangos JA. Antibody-targeted vaccination to lung dendritic cells generates tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells that are highly protective against influenza virus infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:1060–1071. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan TN, Mooster JL, Kilgore AM, Osborn JF, Nolz JC. Local antigen in nonlymphoid tissue promotes resident memory CD8+ T cell formation during viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:951–966. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lauron EJ, et al. Viral MHCI inhibition evades tissue-resident memory T cell formation and responses. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:117–132. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McMaster SR, et al. Pulmonary antigen encounter regulates the establishment of tissue-resident CD8 memory T cells in the lung airways and parenchyma. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adachi T, et al. Hair follicle-derived IL-7 and IL-15 mediate skin-resident memory T cell homeostasis and lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1272–1279. doi: 10.1038/nm.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mackay LK, et al. T-box transcription factors combine with the cytokines TGF-β and IL-15 to control tissue-resident memory T cell fate. Immunity. 2015;43:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGill J, Van Rooijen N, Legge KL. IL-15 trans-presentation by pulmonary dendritic cells promotes effector CD8 T cell survival during influenza virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:521–534. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirai T, et al. Keratinocyte-mediated activation of the cytokine TGF-β maintains skin recirculating memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2019;50:1249–1261.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mohammed J, et al. Stromal cells control the epithelial residence of DCs and memory T cells by regulated activation of TGF-β. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:414–421. doi: 10.1038/ni.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Casey KA, et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J. Immunol. 2012;188:4866–4875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nath AP, et al. Comparative analysis reveals a role for TGF-β in shaping the residency-related transcriptional signature in tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0210495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang N, Bevan MJ. Transforming growth factor-β signaling controls the formation and maintenance of gut-resident memory T cells by regulating migration and retention. Immunity. 2013;39:687–696. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McLaren JE, et al. IL-33 augments virus-specific memory T cell inflation and potentiates the efficacy of an attenuated cytomegalovirus-based vaccine. J. Immunol. 2019;202:943–955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ren HM, et al. IL-21 from high-affinity CD4 T cells drives differentiation of brain-resident CD8 T cells during persistent viral infection. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:eabb5590. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abb5590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pizzolla A, et al. Resident memory CD8 + T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci. Immunol. 2017;2:eaam6970. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schenkel JM, et al. IL-15-independent maintenance of tissue-resident and boosted effector memory CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2016;196:3920–3926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Behr FM, et al. Blimp-1 rather than hobit drives the formation of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells in the lungs. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:400. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mackay LK, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 2016;352:459–463. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herndler-Brandstetter D, et al. KLRG1+ effector CD8+ T cells lose KLRG1, differentiate into all memory T cell lineages, and convey enhanced protective immunity. Immunity. 2018;48:716–729.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kok L, et al. A committed tissue-resident memory T cell precursor within the circulating CD8+ effector T cell pool. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217:e20191711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaide O, et al. Common clonal origin of central and resident memory T cells following skin immunization. Nat. Med. 2015;21:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nm.3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu CI, et al. Human CD1c+ dendritic cells drive the differentiation of CD103+CD8+ mucosal effector T cells via the cytokine TGF-β. Immunity. 2013;38:818–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bourdely P, et al. Transcriptional and functional analysis of CD1c+ human dendritic cells identifies a CD163+ subset priming CD8+CD103+ T cells. Immunity. 2020;53:335–352.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iborra S, et al. Optimal generation of tissue-resident but not circulating memory T cells during viral infection requires crosspriming by DNGR-1+ dendritic cells. Immunity. 2016;45:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim TS, Gorski SA, Hahn S, Murphy KM, Braciale TJ. Distinct dendritic cell subsets dictate the fate decision between effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation by a CD24-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 2014;40:400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mani V, et al. Migratory DCs activate TGF-β to precondition naïve CD8+ T cells for tissue-resident memory fate. Science. 2019;366:eaav5728. doi: 10.1126/science.aav5728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zaid A, et al. Chemokine receptor-dependent control of skin tissue-resident memory T cell formation. J. Immunol. 2017;199:2451–2459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wein AN, et al. CXCR6 regulates localization of tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells to the airways. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:2748–2762. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ma C, Mishra S, Demel EL, Liu Y, Zhang N. TGF-β controls the formation of kidney-resident T cells via promoting effector T cell extravasation. J. Immunol. 2017;198:749–756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing effects of TGF-β and IL-15 cytokines control the number of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cammack AJ, et al. A viral toolkit for recording transcription factor–DNA interactions in live mouse tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:10003–10014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918241117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tu E, et al. T cell receptor-regulated TGF-β type I receptor expression determines T cell quiescence and activation. Immunity. 2018;48:745–759.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Borges da Silva H, et al. Sensing of ATP via the purinergic receptor P2RX7 promotes CD8+ TRM cell generation by enhancing their sensitivity to the cytokine TGF-β. Immunity. 2020;53:158–171.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Borges da Silva H, et al. The purinergic receptor P2RX7 directs metabolic fitness of long-lived memory CD8+ T cells. Nature. 2018;559:264–268. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stark R, et al. TRM maintenance is regulated by tissue damage via P2RX7. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3:eaau1022. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bromley SK, et al. CD49a regulates cutaneous resident memory CD8+ T cell persistence and response. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108085. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reilly EC, et al. T RM integrins CD103 and CD49a differentially support adherence and motility after resolution of influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:12306–12314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915681117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rao RR, Li Q, Odunsi K, Shrikant PA. The mTOR kinase determines effector versus memory CD8+ T cell fate by regulating the expression of transcription factors T-bet and eomesodermin. Immunity. 2010;32:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sowell RT, et al. IL-15 complexes induce migration of resting memory CD8 T cells into mucosal tissues. J. Immunol. 2017;199:2536–2546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sowell RT, Rogozinska M, Nelson CE, Vezys V, Marzo AL. Cutting Edge: generation of effector cells that localize to mucosal tissues and form resident memory CD8 T cells is controlled by mTOR. J. Immunol. 2014;193:2067–2071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhou AC, Batista NV, Watts TH. 4-1BB regulates effector CD8 T cell accumulation in the lung tissue through a TRAF1-, mTOR-, and antigen-dependent mechanism to enhance tissue-resident memory T cell formation during respiratory influenza infection. J. Immunol. 2019;202:2482–2492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pollizzi KN, et al. Asymmetric inheritance of mTORC1 kinase activity during division dictates CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:704–711. doi: 10.1038/ni.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Joshi NS, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8+ T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Laidlaw BJ, et al. Production of IL-10 by CD4+ regulatory T cells during the resolution of infection promotes the maturation of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:871–879. doi: 10.1038/ni.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gebhardt T, et al. Different patterns of peripheral migration by memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Nature. 2011;477:216–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mora JR, et al. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature. 2003;424:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Campbell DJ, Butcher EC. Rapid acquisition of tissue-specific homing phenotypes by CD4+ T cells activated in cutaneous or mucosal lymphoid tissues. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:135–141. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sigmundsdottir H, et al. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to ‘program’ T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:285–293. doi: 10.1038/ni1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cassani B, et al. Gut-tropic T cells that express integrin α4β7 and CCR9 are required for induction of oral immune tolerance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2109–2118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Iwata M, et al. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wakim LM, et al. The molecular signature of tissue resident memory CD8 T cells isolated from the Brain. J. Immunol. 2012;189:3462–3471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Intlekofer AM, et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Laidlaw BJ, et al. CD4+ T cell help guides formation of CD103+ lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells during influenza viral infection. Immunity. 2014;41:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zens KD, et al. Reduced generation of lung tissue-resident memory T cells during infancy. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:2915–2932. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Banerjee A, et al. Cutting Edge: the transcription factor eomesodermin enables CD8+ T cells to compete for the memory cell niche. J. Immunol. 2010;185:4988–4992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lin W-HW, et al. CD8+ T lymphocyte self-renewal during effector cell determination. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Utzschneider DT, et al. Early precursor T cells establish and propagate T cell exhaustion in chronic infection. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:1256–1266. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0760-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yao C, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals TOX as a key regulator of CD8+ T cell persistence in chronic infection. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:890–901. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0403-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wu J, et al. T cell factor 1 suppresses CD103+ lung tissue-resident memory T cell development. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107484. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Danilo M, Chennupati V, Silva JG, Siegert S, Held W. Suppression of Tcf1 by inflammatory cytokines facilitates effector CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell Rep. 2018;22:2107–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Takemoto N, Intlekofer AM, Northrup JT, Wherry EJ, Reiner SL. Cutting Edge: IL-12 inversely regulates T-bet and eomesodermin expression during pathogen-induced CD8+ T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7515–7519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ren X, et al. COVID-19 immune features revealed by a large-scale single-cell transcriptome atlas. Cell. 2021;184:1895–1913.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]