Abstract

A better understanding of the social-structural factors that influence HIV vulnerability is crucial to achieve the goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030. Given the role of neighborhoods in HIV outcomes, synthesis of findings from such research is key to inform efforts toward HIV eradication. We conducted a systematic review to examine the relationship between neighborhood-level factors (e.g., poverty) and HIV vulnerability (via sexual behaviors and substance use). We searched six electronic databases for studies published from January 1, 2007 through November 30, 2017 (PROSPERO CRD42018084384). We also mapped the studies’ geographic distribution to determine whether they aligned with high HIV prevalence areas and/or the “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States”. Fifty-five articles met inclusion criteria. Neighborhood disadvantage, whether measured objectively or subjectively, is one of the most robust correlates of HIV vulnerability. Tests of associations more consistently documented a relationship between neighborhood-level factors and drug use than sexual risk behaviors. There was limited geographic distribution of the studies, with a paucity of research in several counties and states where HIV incidence/prevalence is a concern. Neighborhood influences on HIV vulnerability are the consequence of centuries-old laws, policies and practices that maintain racialized inequities (e.g., racial residential segregation, inequitable urban housing policies). We will not eradicate HIV without multi-level, neighborhood-based approaches to undo these injustices. Our findings inform future research, interventions and policies.

Keywords: HIV, Neighborhoods, Prevention, Risk, Vulnerability

Introduction

HIV incidence rates in the United States (U.S.) have decreased and subsequently stabilized in the overall population [1]. However, while rates continue to decline in some groups (e.g., people who inject drugs, White men who have sex with men [MSM]), they increase or remain stable among others (e.g., Black MSM, Latinx MSM) [1]. Socially and economically disadvantaged populations experience heightened HIV vulnerability/risk of acquiring HIV; disease burden and prevention innovations are not equally distributed across populations. With sexual activity and injection drug use as the leading causes of HIV transmission, it is easy to place the onus of HIV inequities on people engaged in these behaviors. However, this negates the fact that researchers consistently demonstrate that highly affected groups are not “more risky” than other populations [2]. There are broader social-structural influences at play that shape not only individual behaviors, but also the concentration of HIV in an individual’s networks, which ultimately affects HIV vulnerability.

Brawner coined the term “geobehavioral vulnerability to HIV” to highlight that when examining HIV disease burden, one must acknowledge that it is not just what people do, but also where they do it, and with whom [3]. Where a person lives and who is in their networks is critical to understanding HIV inequities; this, however, is not always a choice. In the U.S., there are segregated geographies and constrained social and sexual networks that result from the historical legacies of slavery and institutional racial discrimination [4]. A host of social (e.g., White flight) and structural (e.g., mortgage redlining) factors govern where individuals live, as well as who is in their networks. This relegates some individuals (e.g., those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds) to neighborhoods and other geosocial spaces with limited resources. This directly affects risk for HIV through factors such as concentrated disadvantage, which is associated with limited health-related services, and increases resultant disease burden. A better understanding of the social-structural factors that increase or protect against HIV risk is crucial to the goal of ending the HIV epidemic. Neighborhoods are a concrete place to start.

The role of neighborhood-level factors in health is well documented in the literature [5]. There is increasing attention given to the mechanisms by which neighborhoods shape sexual risk and substance use [6–8]. Factors such as poverty/concentrated disadvantage, social capital and limited health-related resources are associated with HIV-related health disparities [9, 10]. Yet there is a paucity of literature to integrate findings across studies, which limits our ability to identify modifiable targets for neighborhood-level HIV prevention initiatives.

While neighborhoods themselves cannot cause HIV transmission, they do have social and psychological implications for the individuals who live and engage in those spaces [9]. Neighborhoods operate to enable or constrain individual behaviors and thus contribute to HIV vulnerabilities. Researchers have examined the impact of neighborhood on HIV risk, but as a whole, the mechanisms by which neighborhoods influence HIV vulnerability have yet to be well articulated. We conducted a systematic review to examine the relationship between neighborhood-level factors (e.g., poverty) and HIV vulnerability (via sexual behaviors and substance use) to inform future research, interventions and policies to reduce HIV disease burden in highly affected areas.

Methods

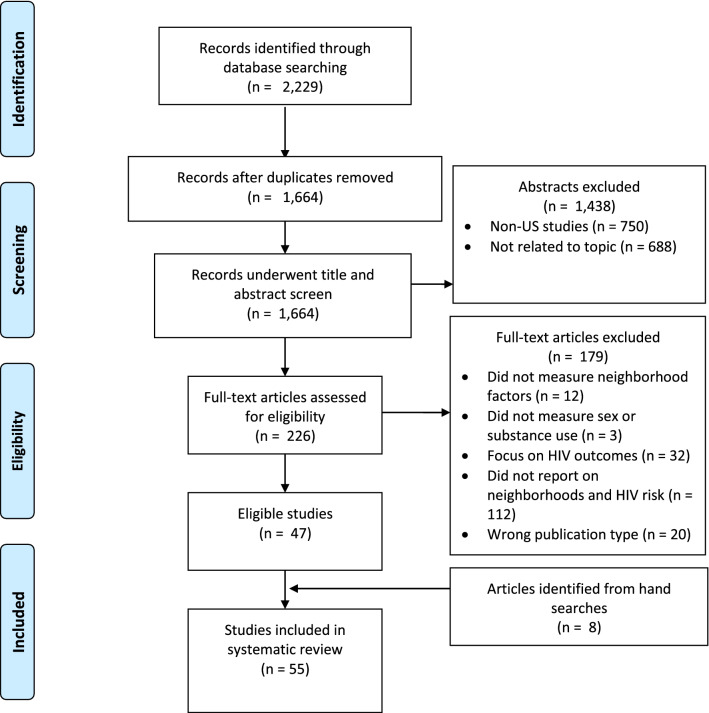

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42018084384), a database of prospectively registered systematic reviews. We followed current Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [11]. We searched six electronic reference databases (PubMed, Medline, PsychINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index [SSCI], the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], and Sociological Abstracts). Our Boolean search strategy was developed by RJ, a biomedical sciences librarian. We used broad search terms relevant to neighborhoods (e.g., “neighborhood*”, “residence characteristics”, “communities”, “social environment”) and the outcomes (e.g., “risk factors”, "substance use”, “condom use”; see Table 1). The search was limited to data from U.S. studies published in English with abstracts and full-text available. The electronic reference database searches were conducted in January 2017 and updated in November 2017. We searched databases from January 1, 2007 through November 30, 2017 since the early 2000s experienced an uptick in work on neighborhood effects, as well as to enhance implications for current HIV prevention initiatives with more recent literature (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Systematic review search terms

| Database | Search terms | Articles yielded |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((HIV[Mesh]) AND (("Residence Characteristics"[Mesh] OR neighborhood*[tiab] OR community[tiab] OR communities[tiab] OR zipcode[tiab] OR "zip code" OR "census tract" OR "Cities"[Mesh] OR "city"[tiab] OR "Social Environment"[Mesh]))) AND ("Unsafe Sex"[Mesh] OR "Risk Factors"[Mesh] OR "Risk"[Mesh] OR "Substance-Related Disorders"[Mesh] OR "substance use" OR "drug use" OR "Behavior"[Mesh] OR “Condoms”[Mesh] OR “condom use"[tiab] OR “housing instability” OR “unstable housing” OR eviction OR evicted OR "housing insecurity" OR "insecure housing" OR (“sexual partners” AND (concurren* OR overlap*))) | 411 |

| PsycINFO | mjsub(HIV) AND (mjsub("residence characteristics") OR ti(neighborhood) OR ab(neighborhood) OR mjsub("neighborhoods") OR mjsub("communities") OR ti(zipcode*) OR ab(zipcode*) OR ti("zip code") OR ab("zip code") OR ab("census tract") OR mjsub("social environment")) AND (mjsub("unsafe sex") OR mjsub("risk factors") OR mjsub("substance-related disorders") OR (ti("substance use") OR ti("drug use")) OR mjsub(behavior) OR mjsub(condoms) OR (ti("condom use") OR ab("condom use")) OR (ti("housing instability") OR ti("unstable housing") OR ti("housing insecurity") OR ti("insecure housing")) OR (mjsub("sexual partners") AND (concurren* OR overlap*))) | 379 |

| Soc Abstracts | su(HIV) AND (su("residence characteristics") OR ti(neighborhood) OR ab(neighborhood) OR su("neighborhoods") OR su("communities") OR ti(zipcode*) OR ab(zipcode*) OR ti("zip code") OR ab("zip code") OR ab("census tract") OR su("social environment")) AND (su("unsafe sex") OR su("risk factors") OR su("substance-related disorders") OR (ti("substance use") OR ti("drug use")) OR su(behavior) OR su(condoms) OR (ti("condom use") OR ab("condom use")) OR (ti("housing instability") OR ti("unstable housing") OR ti("housing insecurity") OR ti("insecure housing")) OR (su("sexual partners") AND (concurren* OR overlap*))) | 42 |

| Social Sciences Citation Index (SCCI) | (TS = HIV) AND (TS = “residence characteristics” OR ti = neighborhood OR TS = "neighborhoods" OR TS = “communities” OR TI = zipcode* OR TI = "zip code" OR TI = “census tract” OR TS = “social environment”) AND (TS = “unsafe sex” OR TS = “risk factors” OR TS = “substance-related disorders” OR TI = “substance use” OR TI = “drug use” OR TS = behavior OR TS = condoms OR TS = “condom use” OR TI = “condom use” OR TI = “housing instability” OR TI = “unstable housing” OR TI = “housing insecurity” OR TI = “insecure housing” OR TI = “concurrent sexual partners”) | 791 |

| CINAHL | (MH “Human Immunodeficiency Virus+”) AND (MH “Social Environment+” OR City OR Cities OR MH “Urban Areas” OR “census tract” OR zipcode OR “zip code” OR community OR communities OR neighborhood* OR MH “Residence Characteristics+”) AND ((“sexual partners” AND (concurren* OR overlap*)) OR “housing insecurity” OR “insecure housing” OR eviction OR evicted OR “housing instability” OR “Unstable housing” OR “condom use” OR MH “Condoms+” OR MH “Behavior+” OR “substance use” OR “drug use” OR MH “Substance Use Disorders+” OR “risk” OR MH “Risk Factors+” OR MH “Unsafe Sex”) | 91 |

| Medline | (exp HIV/ AND (exp Social Environment/ OR exp Cities/ OR neighborhood.mp. OR neighborhoods.mp. OR community.mp. OR communities.mp. OR zipcode.mp. OR zip code.mp. OR census tract.mp. OR city.mp.) AND (exp Unsafe Sex/ OR exp Risk Factors/ OR exp Risk/ OR exp Substance-Related Disorders/ OR "substance use".mp. OR drug use".mp. OR exp Behavior/ OR exp Condoms/ OR "condom use".mp. OR housing instability.mp. OR unstable housing.mp. OR housing insecurity.mp. OR insecure housing.mp. OR eviction.mp. OR evicted.mp. OR ((sexual partners.mp. or exp Sexual Partners/) AND (concurren* or overlap*).mp)) | 515 |

| Total | 2229 |

Several of the electronic databases had specific search methods (e.g., PubMed uses Medical Subject Heading [MeSH] terms) while some other databases do not, thus the search strategy was modified according to the parameters for each database

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) diagram for the reviewed articles

Study Selection and Data Extraction

The initial search yielded a total of 2229 articles. RJ created an EndNote X8 library for data management and independently screened titles and abstracts to identify full-text articles for final eligibility review. We considered empirical articles (including qualitative and quantitative studies) with a specific focus on the relationship between neighborhoods and HIV risk behaviors. Articles were included if they: (a) measured neighborhood-level factors (e.g., poverty), (b) measured sexual risk behavior(s) (e.g., multiple sexual partners) and/or substance use/abuse outcomes (e.g., injection drug use), and (c) examined and reported on the relationship between neighborhood-level factors and HIV risk behaviors in the analyses. Articles with a primary focus on HIV outcomes (e.g., testing, medication adherence), dissertations, non-peer reviewed publications, commentaries, literature reviews and other conceptual/theoretical work, and articles that did not expressly address neighborhood-level influences on HIV risk behaviors were excluded.

After RJ excluded duplicates (n = 565) and 1438 titles and abstracts that did not meet the inclusion criteria, BMB and JK independently reviewed the remaining 226 full-text articles for final inclusion. They each created independent lists of articles to include/exclude, with a cumulative total of 60 articles between them for consideration. They reached initial agreement on 47 of the 60 articles, and held subsequent meetings with co-authors to reach consensus on 13 articles where there were disagreements. The co-authors made a determination to exclude these 13 articles from the review as they did not strictly adhere to the inclusion criteria (e.g., the studies did not provide adequate measurement or definition of neighborhoods in the analyses). Eight articles that were not identified in the search strategy but were relevant to the topic were discovered by hand-searching the references lists in the included articles. With the 47 articles identified from the search strategy, and eight discovered in the hand-search, complete agreement was reached by all authors on the final 55 articles included in this review.

JAB and BFC conducted data extraction based on a protocol for key study characteristics including: study year(s) and location, design, individual and neighborhood sample size and description, how neighborhoods were definition/operationalized, individual-level variables, neighborhood-level variables, outcome variables, key findings/conclusion, and directions for future research. We wanted to determine whether the study locations mapped onto areas with high HIV prevalence and/or were in the “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America” (EHE)—a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) initiative to reduce new HIV infections in the U.S. by 90% by 2030 [12]. The EHE prioritizes efforts in 57 jurisdictions, including 48 counties, Washington, DC, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and seven states with a significant number of HIV diagnoses in rural areas (Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky, and South Carolina). SB created maps in ArcGIS 10.6 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) to visualize the geographic distribution of the studies.

Results

Of the 55 articles included in this review, 44 were quantitative, 8 were qualitative and three were mixed or multi-method studies (see Table 2). While the majority of the studies focused on adult populations, 9 included youth samples. The majority included participants regardless of race or ethnicity and had samples experiencing socioeconomic challenges (e.g., homelessness). Black/African American populations were the predominant focus among the studies targeted to specific racial or ethnic groups (n = 14); only one study explicitly focused on a Latinx population. The majority did not specify sexual identity; 16 studies focused on MSM, bisexual men and/or transwomen.

Table 2.

Study design and neighborhood description

| Article citation | Study years | Location of study | Study design | Neighborhood description | Neighborhood definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akers, A. Y., Muhammad, M. R., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2011) | 2006 | Northeastern North Carolina | Qualitative, Grounded theory approach; focus groups of adolescents, young adults, and adults | Rural county | Kone et al., 2000 definition of a neighborhood as a group of people with existing social relationships and interaction patterns that share common interests, have similar cultural backgrounds, and live in the same geographic area |

| Bauermeister J.A., Eaton L., Andrzejewski J., Loveluck J., VanHemert W., & Pingel, E.S. (2015) | 2015 | Detroit | Cross-sectional survey | No description | Census tract |

| Bauermeister, J. A., Zimmerman, M. A., & Caldwell, C. H. (2011) | 1994–1997 | Midwest (Flint, MI) | Longitudinal study | No description | Census block group |

| Biello, K. B., Niccolai, L., Kershaw, T. S., Lin, H., & Ickovics, J. (2013) | 1997–2007 | Metropolitan areas of the United States | Longitudinal study | Population factors related to segregation concentration, clustering, exposure | Census tract |

| Bluthenthal, R. N., Do, D. P., Finch, B., Martinez, A., Edlin, B. R., & Kral, A. H. (2007) | 1998–2002 | San Francisco Bay Area | Cross-sectional study | East Bay area of San Francisco | Census tract |

| Bobashev, G. V., Zule, W. A., Osilla, K. C., Kline, T. L., & Wechsberg, W. M. (2009) | 2005–2008 | Counties of North Carolina | Cross-sectional study | Durham, Wake, Johnston, and Chatham counties | County |

| Bowleg, L., Neilands, T. B., Tabb, L. P., Burkholder, G. J., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2014) | Not reported | Philadelphia | Cross-sectional, mixed methods study | US Census blocks with a Black population of at least 50% | Census blocks |

| Boyer, C. B., Greenberg, L., Chutuape, K., Walker, B., Monte, D., Kirk, J.,... & Adolescent Med Trials, N. (2017) | 2012–2013 | Tampa, LA, DC, Philadelphia, Chicago, Bronx, NY, New Orleans, Miami, Memphis, Houston, Detroit, Baltimore, Boston, Denver | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhood examined as "community context" | N/A |

| Braine, N., Acker, C., Goldblatt, C., Yi, H., Friedman, S., & DesJarlais, D. C. (2008) | 2000–2001 | Pittsburgh | Qualitative, historical analysis | Hill District, Uptown, and other neighborhoods of Pittsburgh | Historical and socially defined neighborhoods as provided by participants; Census tracts used with historical data |

| Brawner B.M., Reason J.L., Hanlon K., Guthrie B., Schensul J.J. (2017) | 2012 | Philadelphia | Qualitative descriptive study | Community included in study included was selected to ensure the greatest diversity possible | Census tract |

| Brawner, B. M., Guthrie, B., Stevens, R., Taylor, L., Eberhart, M., & Schensul, J. J. (2017) | 2011–2013 | Philadelphia | Multi-method, comparative study | Philadelphia Census tracts selected to achieve maximal difference across the areas according to racial/ethnic composition and HIV disease burden | Census tract |

| Buot, M. L. G., Docena, J. P., Ratemo, B. K., Bittner, M. J., Burlew, J. T., Nuritdinov, A. R., & Robbins, J. R. (2014) | 1990 and 2000 | United States | Cross-sectional secondary data analysis | No description | Cities with populations greater than 100,000 in 1990 and 2000 and reported as discrete places (cities) by the CDC and the US Census Bureau |

| Buttram, M. E., & Kurtz, S. P. (2013) | 2008–2010 | Miami /Ft.-Lauderdale | Cross-sectional study | Gay neighborhoods can be defined as visible places within a city that commonly have businesses, residences, and social life dominated by gay men | Zip codes, defined as a gay neighborhood versus non-gay neighborhood |

| Cené, C. W., Akers, A. Y., Lloyd, S. W., Albritton, T., Powell Hammond, W., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2011) | 2006–2007 | Two Northeast counties in North Carolina | Community-based participatory study, semi-structured qualitative interviews | Neighborhood defined as a component of the Social Network Model | N/A |

| Cooper, H. L., Friedman, S. R., Tempalski, B., & Friedman, R. (2007) | 1990 and 1998 | United States | Lagged, cross-sectional study; secondary data analysis | Counties that include at least 1 central city home to at least 500,000 residents in 1993 | US metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) defined by the US Census Bureau; Census tract |

| Cooper, H. L., Linton, S., Haley, D. F., Kelley, M. E., Dauria, E. F., Karnes, C. C., … & Adimora, A. (2015) | 2008–2010 | Atlanta, GA | Cross-sectional, multilevel, longitudinal study | Neighborhoods segregation between White and African-American households are a form of structural discrimination | Census tract |

| Cooper, H. L., Linton, S., Kelley, M. E., Ross, Z., Wolfe, M. E., Chen, Y. T., … & Semaan, S. (2016) | 2009 | United States | Cross-sectional, quantitative study; secondary data analysis | Neighborhoods conceptualized using the Risk Environment Model | MSAs; zip codes and counties (provided by participants) |

| Crawford, N. D., Borrell, L. N., Galea, S., Ford, C., Latkin, C., & Fuller, C. M. (2013) | 2000 | New York City (Harlem, Lower East Side, South Bronx, Jamaica-Queens and Bedford-Stuyvesant-Brooklyn) | Cross-sectional, secondary data analysis | Neighborhoods are contexts in which individuals may experience social discrimination | Census tracts |

| DePadilla, L., Elifson, K. W., & Sterk, C. E. (2012) | 2009–2011 | Atlanta, GA | Cross-sectional, quantitative study | Conceptualized neighborhoods as places where individual behaviors occur in the larger context of poverty, unequal access to health care, and uneven criminal justice involvement | Census block groups used for sampling |

| Duncan, D. T., Kapadia, F., & Halkitis, P. N. (2014) | 2009–2011 | New York City | Cross-sectional, quantitative study | Defined neighborhoods as varying spatial contexts, where individuals can move beyond where they reside (e.g. the residential neighborhood) for school, church, shopping, and socialization | Borough, neighborhood contexts (residential, social, sexual) |

| Study 1: not stated | South Florida | Cross-sectional, two-armed, randomized controlled trial | Neighborhoods conceptualized regarding MSM migration to urban neighborhoods to avoid discrimination and alienation and to find support and acceptance from other MSM, yet may increase their vulnerability to sexual risks and drug use | South Florida region | |

| Egan, J. E., Frye, V., Kurtz, S. P., Latkin, C., Chen, M., Tobin, K., … & Koblin, B. A. (2011) | Study 2: not stated | New York City | Qualitative observational study | Discussed urban "gay" neighborhoods as areas that may offer acceptance and socialization for urban MSM, yet also expose MSM to high-risk micro-environments that significantly increase risk of mental and physical health problems related to gentrification and stress associated with neighborhood tension | Distinct neighborhoods (Chelsea/Hell's Kitchen, Fort Greene, Harlem, and Washington Heights) that are part of the NYC MSA; participant-defined to map their residential neighborhood, social neighborhood, and sexual neighborhood |

| Study 3: not stated | Baltimore | Cross-sectional, randomized clinical trail | Discussed social networks that contribute to the amount, type, and source of emotional and instrumental social support | N/A (no neighborhood level variables) | |

| Frew, P. M., Parker, K., Vo, L., Haley, D., O'Leary, A., Diallo, D. D., … & Hodder, S. (2016) | 2009–2010 | New York City, Atlanta, Baltimore, Newark, Raleigh-Durham, NC; Washington, DC | Qualitative study | Neighborhood conceptualized using Bronfrenbrenner's ecological model | Zip code or census tract |

| Frye, V., Koblin, B., Chin, J., Beard, J., Blaney, S., Halkitis, P., … & Galea, S. (2010) | 1990–2000 | New York City | Multilevel analysis | Discussed neighborhoods as urban areas with a concentration of MSM that serves as an environment that may influence health behaviors | Zip code |

| Frye, V., Nandi, V., Egan, J. E., Cerda, M., Rundle, A., Quinn, J. W., … & Koblin, B. (2017) | 2010–2013 | New York City | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhoods described as gay enclaves, those with a growing gay population, as well as neighborhoods with a much less visible or documented gay presence | Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs) |

| Genberg, B. L., Gange, S. J., Go, V. F., Celentano, D. D., Kirk, G. D., Latkin, C. A., & Mehta, S. H. (2011) | 1988–2008 | Baltimore | Prospective cohort study | Urban area | Census tracts |

| Gindi, R. M., Sifakis, F., Sherman, S. G., Towe, V. L., Flynn, C., & Zenilman, J. M. (2011) | 2007 | Baltimore | Prospective cohort study | Neighborhood-level predictors are settings in which individuals choose their sex partners. Participants define what "in the neighborhood" meant | Census tracts |

| Haley, D. F., Haardorfer, R., Kramer, M. R., Adimora, A. A., Wingood, G. M., Goswami, N. D., … & Cooper, H. L. F. (2017) | 2013–2015 | Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, and North Carolina | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhoods conceptualized as opportunity structures in which residents with greater economic disadvantage or social disorder have decreased access to resources necessary for healthy behaviors and greater risk or hazardous exposures that are detrimental to health | Census tract |

| Heimer, R., Barbour, R., Palacios, W. R., Nichols, L. G., & Grau, L. E. (2014) | 2008–2011 | Towns in Fairfield or New Haven Counties in Connecticut | Longitudinal study | Suburban communities in southwest Connecticut (with the exclusion of Bridgeport, Danbury, New Haven, Norwalk, Stamford, or Waterbury) | Census tract |

| Kelly, B. C., Carpiano, R. M., Easterbrook, A., & Parsons, J. T. (2012) | 2005 | New York City | Cross-sectional, intercept survey | NYC or New Jersey areas served by the PATH train routes; suburbs | Zip codes |

| Kerr, J. C., Valois, R. F., Siddiqi, A., Vanable, P., & Carey, M. P. (2015) | 2006–2007 | Macon, GA, Providence, RI, Syracuse, NY, and Columbia, SC | Cross-sectional study | Northeastern and Southeastern U.S. | U.S. region (Northeast, Southeast) |

| Knittel, A. K., Snow, R. C., Riolo, R. L., Griffith, D. M., & Morenoff, J. (2015) | Not reported (examined data over 5 years) | United States | Agent-based modeling | Neighborhoods simulated agents (incarcerated individuals) from urban areas in model developed in this study | N/A |

| Koblin, B. A., Egan, J. E., Rundle, A., Quinn, J., Tieu, H. V., Cerdá, M., … & Frye, V. (2013) | 2010–2012 | New York City | Cross-sectional study | NYC boroughs that are traditionally considered gay enclaves, those with a growing gay population, as well as neighborhoods with a much less visible or documented gay presence | NYC boroughs, census tracts |

| Koblin, B. A., Egan, J. E., Nandi, V., Sang, J. M., Cerda, M., Tieu, H.-V.,... Frye, V. (2017) | 2010–2013 | New York City | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhoods within NYC community districts which range in population size from 50,000 residents to more than 200,000 | Community districts and neighborhoods |

| Latkin, C. A., Curry, A. D., Hua, W., & Davey, M. A. (2007) | 2002–2004 | Baltimore | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhood conceptualized as residential location is associated with physical health and mortality | N/A |

| Lutfi, K., Trepka, M. J., Fennie, K. P., Ibanez, G., & Gladwin, H. (2015) | 2006–2010 | US metropolitan and micropolitan areas | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhood conceptualized as community factors can contribute to disparities in sexually transmitted infections related to racial segregation | Core-based statistical areas (CBSA), census tract |

| Martinez, A. N., Lorvick, J., & Kral, A. H. (2014) | 2004–2005 | San Francisco Bay Area | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhoods described as activity spaces- the local areas of neighborhoods in which individuals move throughout their course of daily activities | Census tract |

| Mustanski, B., Birkett, M., Kuhns, L. M., Latkin, C. A., & Muth, S. Q. (2015) | 2011–2012 | Chicago | Network study | Neighborhoods describes as locations in which disparities exist in socioeconomic status and HIV prevalence, and racial segregation | Community area |

| Nandi, A., Glass, T. A., Cole, S. R., Chu, H., Galea, S., Celentano, D. D.,... Mehta, S. H. (2010) | 1990–2006 | Baltimore City, MD | Prospective cohort study | Location of study had a per capita prevalence of IDU of 162 per 10,000 population, second among the largest metropolitan statistical areas in the U.S. and 14% prevalence of HIV among IDUs in 1998. Ranked 11th among the largest metropolitan statistical areas in the U.S. | Census tracts |

| Neaigus, A., Jenness, S. M., Reilly, K. H., Youm, Y., Hagan, H., Wendel, T., & Gelpi-Acosta, C. (2016) | 2010 | New York City | Cross-sectional study | Location of study described as NYC adjoining communities with high poverty zip codes areas that were designed to approximate NYC Community Planning Districts | United Hospital Fund neighborhoods |

| Pachankis, J. E., Eldahan, A. I., & Golub, S. A. (2016) | 2014 | New York City | Cross-sectional study | Neighborhood of focus in this study were described as urban neighborhoods that are destinations for gay or bisexual men | Zip codes |

| Parrado, E. A., & Flippen, C. (2010) | 2002–2003 and 2006–2007 | Durham, NC | Cohort study | Utilized a theoretical framework of social disorganization and commercial sex | Apartment complex |

| Quinn, K., Voisin, D. R., Bouris, A., & Schneider, J. (2016) | 2012–2014 | Chicago | Randomized control trial | Neighborhood conceptualized as component of “HIV risk environment”, involving a dynamic interplay between structural and network factors | N/A |

| Raymond, H. F., Al-Tayyib, A., Neaigus, A., Reilly, K. H., Braunstein, S., Brady, K. A., … & German, D. (2017) | 2011 | Baltimore, Detroit, Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and District of Columbia | National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) data used for the study (phylogenetic study) | Neighborhoods characterized as environments of high poverty and/or low socioeconomic status, and environments of sexual networks; these contribute to disparities in HIV incidence in the U.S. | City (NHBS data collection jurisdiction for each individual-funded entity; can include a metropolitan statistical area) |

| Raymond, H. F., Chen, Y. H., Same, S. L., Catalano, R., Hutson, M. A., & McFarland, W. (2014) | 2008 | San Francisco | Geographic analysis | Utilized a social epidemiologic framework of HIV infection which suggests that low SES neighborhoods and social and sexual networks in communities influence disparities in HIV infection | Zip code |

| Rothenberg, R. B., Dai, D., Adams, M. A., & Heath, J. W. (2017) | 2006–2011 | Atlanta | Cross-sectional study | Not reported | Zip code |

| Rudolph, A. E., Crawford, N. D., Latkin, C., Fowler, J. H., & Fuller, C. M. (2013) | 2006–2009 | New York City | Longitudinal study | Discussed neighborhoods as having structural and network factors that can contribute to increased risk for HIV | Census tract |

| Rudolph, A. E., Linton, S., Dyer, T. P., & Latkin, C. (2013) | 2005–2007 | Baltimore | Cross-sectional study | Characterized the “HIV risk environment” as a dynamic interplay between structural and network factors | City block |

| Senn, T. E., Walsh, J. L., & Carey, M. P. (2016) | Not reported | United States | Cross-sectional study | Conceptualized neighborhood as containing contextual factors that affect sexual health and STIs | Census tract |

| Sterk, C. E., Elifson, K. W., & Theall, K. P. (2007) | 2002–2004 | Atlanta | Ethnographic study | Discussed neighborhoods as having conditions, such as neighborhood disadvantage, that often result in impaired health | Inner city community |

| Stevens, R., Gilliard‐Matthews, S., Nilsen, M., Malven, E., & Dunaev, J. (2014) | Not reported | Northeastern city | Qualitative study | City of study is typified by concentrated poverty, high childhood high rate of single-parent headed households, and low graduation rate. This city also ranked second to last in the nation for safety in 2010 | City |

| Stevens, R., Icard, L., Jemmott, J. B., O'Leary, A., Rutledge, S., Hsu, J., & Stephens-Shields, A. (2017) | 2008 – 2011; 2006–2010 | Philadelphia | Cross-sectional study | Discussed neighborhoods as having characteristics, such as perceived neighborhood disorder, perceived neighborhood violence, and homelessness, that are associated with transactional sexual behaviors | Census block group |

| Tobin, K. E., Latkin, C. A., & Curriero, F. C. (2014) | 2012 | Baltimore | Cross-sectional study | Study setting is one of the most burdened cities in the country, ranking the second highest for gonorrhea, seventh for syphilis cases, and fourth highest for Chlamydia | City |

| Tobin, K. E., Hester, L., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Latkin, C. A. (2012) | 2008 | Baltimore | Cross-sectional, secondary data analysis | Neighborhood or residential location has been hypothesized to influence health is through facilitating social interaction sand formation and perpetuation of social norms | Census block group |

| Voisin, D. R., Hotton, A. L., & Neilands, T. B. (2014) | 2006 | Midwestern city | Cross-sectional study | Exposure to community violence is another significant public health concern that disproportionately impacts African American youth. Community violence may influence HIV risk behaviors among youth | N/A |

| Williams, C. T., & Latkin, C. A. (2007) | 1996–2002 | Baltimore City | Cross-sectional, multilevel design | Neighborhood environments represent a more distal social context that capture physical and economic features of one’s environment, and structures network composition and relations | Census block group |

Four key findings were noted: (a) there is substantial variability in how authors define and operationalize neighborhood-level factors; (b) most sexual risk behavior studies focus on condom use instead of other outcomes, and most substance use studies focus on injection drugs instead of alcohol or other drugs; (c) tests of associations more consistently document a relationship between neighborhood-level factors and drug use than sexual risk behaviors; and (d) there is limited geographic distribution of studies, with a paucity of research in several populous metropolitan areas where HIV incidence/prevalence is a concern.

Definition and Operationalization of Neighborhood-Level Factors

The majority of the studies reviewed defined neighborhoods in terms of administrative boundaries such as region of the U.S., metropolitan statistical areas, census tracts or block groups, or a combination of the above (n = 48). One study did examine apartment complexes, providing a more granular analysis of the relationship between neighborhood social milieu and sexual risk [13]. Some also chose nontraditional definitions such as groups of individuals with existing social relationships and interaction patterns [14] or locales dominated by gay men (i.e., gay neighborhood residence versus non-residence) [15]. Others allowed the study participants to define their neighborhoods relative to historical or social markers [16, 17]. Neighborhood-level variables of interest included but were not limited to sociodemographics (e.g., percentage of adults in the zip code with a college education), HIV incidence and prevalence rates, social capital (e.g., trust and connections among community members), indicators of structural disadvantage in the built environment (e.g., vacant housing), community violence and racial residential segregation. Fewer studies examined factors such as social and geographic distance [18], or spatial clustering of locations for drug and alcohol use [19].

HIV Vulnerability Outcomes of Interest

Sexual risk behaviors were the main outcome in most of the quantitative studies (n = 28; see Table 3); condom use was the most commonly reported outcome. Articles related to sexual risk also included primary outcomes of HIV/STI incidence, number of sexual partners, sexual debut, exchange/transactional sex and behavioral norms. One study measured participants’ perceptions of their partner’s risk and concurrency [20]. For those that focused on substance use (n = 10), injection drug use was the most prominent, followed by alcohol. One study also examined participants’ membership in high prevalence drug networks [21]. Eight articles included sexual and substance use behaviors as primary outcomes, examining both behaviors such as receptive/distributive syringe sharing and number of sexual partners.

Table 3.

Study sample and variables

| Article citation | Neighborhood sample size | Individual sample size | Inclusion criteria | Individual-level variables | Neighborhood-level variables | Outcome variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akers, A. Y., Muhammad, M. R., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2011) | n = 2 | n = 93 | Purposive sampling; young people aged 16–24 years (4 focus groups, n = 38), adults aged 25 years and above (5 focus groups, n = 42) and formerly incarcerated individuals (2 focus groups, n = 13) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bauermeister J.A., Eaton L., Andrzejewski J., Loveluck J., VanHemert W., Pingel, E.S. (2015) | N/A | n = 328 | Age 18–29, cismale or transgender, residing in Detroit metro, and reporting having sex with men | Race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, educational attainment, relationship status, residential stability, alcohol use, marijuana use | Perceived community LGBT acceptance, perceived community LGBT stigma, Residential address, distance from LGBT bars & clubs, HIV testing sites, AIDS Service organizations, AIDSvu test locators, LGBT organizations, neighborhood disadvantage score (%households in poverty, % households in public aid, % single-headed households with children, %residents over age 25 w/o high school diploma) | HIV testing, sex with serodiscordant UAI partner |

| Bauermeister, J. A., Zimmerman, M. A., & Caldwell, C. H. (2011) | n = 123 | n = 681 | Eligible participants had a GPA of 3.0 or lower at the end of 8th grade, not diagnosed with emotional or developmental impairments, and identified as African American, White, or Bi-racial | Self-reported: condom use, frequency of sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, pregnancy concerns, psychological distress, substance use, age, sex, parental occupation (provided by participant) | Standardized neighborhood concentrated economic disadvantage score | Condom use |

| Biello, K. B., Niccolai, L., Kershaw, T. S., Lin, H., & Ickovics, J. (2013) | n = 17 | n = 4583 | Individual-level data obtained from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 ages 12–16 years old on December 31, 1996; data limited to non-Hispanic blacks and whites residing in Census-defined metropolitan areas | Self-reported: race, ethnicity, sex; parent-reported: gross household income, maternal and paternal education, family structure | Hyper segregation: exposure, concentration, centralization, clustering, and unevenness; population size, population density, racial composition, socioeconomic measures (percent unemployed, percent in poverty, percent with less than high school education) | Sexual risk behavior |

| Bluthenthal, R. N., Do, D. P., Finch, B., Martinez, A., Edlin, B. R., & Kral, A. H. (2007) | n = 294 tracts (Syring sharing sample); n = 282 (sexual behavior sample) | n = 4956 | Data obtained from the Urban Health Study (UHS); participants were 18 years or older and had physical evidence of drug injection (track marks or stigmata) | Self-reported: gender (male, female), age (continuous), education (less than high school, high school, some college, college, or college graduate), race (white, African American, Hispanic, or other), sexual orientation (heterosexual or gay/lesbian/bisexual), homelessness (yes or no), main income source (paid work, government assistance, or other), consistent sex partner (yes or no), syringe exchange program in the past 6 months (yes or no), and participation in same gender sex in the past 6 months (yes or no), street and cross-street of residence; researcher determined: HIV positive status (yes or no) | Percent African American, percent male unemployment, percent of households that receive public assistance, median household income; economic deprivation (average of four indicators: proportion of 16–19 year-old high school drop outs, male unemployment rate, households receiving public assistance, and female head of households) | Receptive syringe sharing, distributive syringe sharing, unprotected sex, and multiple sex partners |

| Bobashev, G. V., Zule, W. A., Osilla, K. C., Kline, T. L., & Wechsberg, W. M. (2009) | n = 4 | n = 1730 | Males, at least 18 years old; female sex partners also included in study; report history of substance abuse (heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, or injection drug) in the past 6 months; report anal sex with a male in the past 6 months, participants who were recruited with their partner must have reported to have sex with that partner in the past 6 months | Sex (male or female), bisexual behavior, psychological distress (depression, anxiety, somatization subscales of the BSI-18), drug use, binge drinking of alcohol, sexual risk behaviors, partner change within the past 6 months, HIV, any STIs, unprotected sex | Provided by participants: perceived neighborhood violence and neighborhood disorder | Transactional sex (purchasing or selling sex) |

| Bowleg, L., Neilands, T. B., Tabb, L. P., Burkholder, G. J., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2014) | n = 60 | n = 526 | Black/African American men, identifying as heterosexual, 18–44 years old, and reported vaginal sex during the last 2 months | Substance use, depression, demographics (age, education, employment status, relationship status) | Participant-reported City Stress Inventory (CSI) 18-item measure | Sexual risk behavior |

| Boyer, C. B., Greenberg, L., Chutuape, K., Walker, B., Monte, D., Kirk, J.... & Adolescent Med Trials, N. (2017) | N/A | N = 1818 |

Study eligibility included being aged 12–24 years and having a self-reported history of engaging in consensual sex (oral, anal, or vaginal) in the 12-month period prior to survey administration |

Age, birth and identified sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, educational attainment, history of homelessness, current living situation, and relationship status | Participant-reported economic insecurity, job training, housing instability, crime victimization, and perceived community norms | Transactional sex (selling sex) |

| Braine, N., Acker, C., Goldblatt, C., Yi, H., Friedman, S., & DesJarlais, D. C. (2008) | n = 30 | n = 151 | Respondents must report regularly receiving syringes during the last year, either directly from volunteers or indirectly through secondary exchange/distribution | Demographics, neighborhood of residence, drug use, sexual behavior, HIV risk behavior, health status, and syringe distribution networks | Historical policy of migration, neighborhood formation, entertainment venues, and drug policy | N/A |

| Brawner B.M., Reason J.L., Hanlon K., Guthrie B., Schensul J.J. (2017) | n = 1 | n = 10 | Age 18 and older, lived, worked and/or had a vested interest in the Philadelphia Census tract with the highest HIV and AIDS rates in the city. Included administrators, direct HIV/AIDS service provider, or community member | Demographic variables (age, income) | N/A | N/A |

| Brawner, B. M., Guthrie, B., Stevens, R., Taylor, L., Eberhart, M., & Schensul, J. J. (2017) | n = 4 | n = 339 | HIV surveillance case data included if cases: resided in one of the four targeted Census tracts, were diagnosed on or before December 31, 2010, were living as of January 1, 2006, and were at least 18 years of age | Current age, Census tract of current residence (most recently recorded address), gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and most recently recorded CD4 count | Census tracts categorized as (a) predominantly white high HIV prevalence, (b) predominantly black high HIV prevalence, (c) predominantly white low HIV prevalence, and (d) predominantly black low HIV prevalence | Mode of HIV transmission (Male-to-male sexual contact, heterosexual, or IDU) |

| Buot, M. L. G., Docena, J. P., Ratemo, B. K., Bittner, M. J., Burlew, J. T., Nuritdinov, A. R., & Robbins, J. R. (2014) | n = 80 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1990–2000 US Census data: housing, segregation, living wage estimates, health insurance estimates, crime, anti-MSM stigma (SSM legislation); CDC Wonder database: race/ethnicity, HIV risk behavior categorization | Average HIV incidence |

| Buttram, M. E., & Kurtz, S. P. (2013) | n = 2 | n = 482 | Substance-using MSM who reported recent UAI | Demographic, physical health, mental health, legal involvement, vocational attainment | N/A | Substance use, sexual risk behaviors, prosocial participation |

| Cené, C. W., Akers, A. Y., Lloyd, S. W., Albritton, T., Powell Hammond, W., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2011) | N/A | n = 93 | Focus groups: Age 16 and older; Interviews: Individuals identified by community partners as having valuable opinions on HIV risk, disparities, and potential solutions | Descriptive statistics | Population size, percent African American, State ranking in three-year average rage of new HIV cases, percent of HIV/AIDS cases per county among African Americans, median household income, percent with less than a high school education, percent with a high school diploma, percent with a bachelor's degree or higher | N/A |

| Cooper, H. L., Friedman, S. R., Tempalski, B., & Friedman, R. (2007) | n = 93 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Segregation (concentration and isolation), prevalence of injection drug users per MSA, MSA population size, racial/ethnic composition, geographic region | Injection drug use prevalence among Black adults |

| Cooper, H. L., Linton, S., Haley, D. F., Kelley, M. E., Dauria, E. F., Karnes, C. C., … & Adimora, A. (2015) | n = 77 | n = 172 | Participants must have resided in one of the seven complexes targeted for demolition; being at least 18 years old; self-identifying as Non-Hispanic Black/African American; reported sexual activity in the past year; and not have lived with a previously enrolled participant | Gender, age, marriage status, high school education, annual household income, same-sex behavior, self-reported HIV positive, binge drinking, drug use, alcohol or drug dependence, moved to a new Census tract, perceived community violence | Median household income, poverty rate, percent adults (greater or equal to 25 years old) whose highest degree is a high school diploma or GED, violent crime rate, density of alcohol outlets per square mile, economic disadvantage component, social disorder component, male: female sex ratio | Perceived partner risk, perceived indirect concurrency, perceived neighborhood conditions |

| Cooper, H. L., Linton, S., Kelley, M. E., Ross, Z., Wolfe, M. E., Chen, Y. T. … & Semaan, S. (2016) | n = 19 | n = 9170 | Eligible participants reported injecting drugs in the past 12 months and provided proof of injection (e.g., track marks); lived in the target MSA; and were 18 years old | Race/ethnicity (Latino, white, black), participant-reported zip codes and counties, sociodemographic characteristics, drug-related behaviors | Availability of sex partners, race/ethnic composition, exposure to violence, racial/ethnic segregation, exposure to economic disadvantage, income inequality, spatial access to drug- and HIV related programs, access to general medical care, HIV epidemic among PWID, exposure to law enforcement, policies governing syringe access, health and law enforcement expenditures, access to alcohol, exposure to abandoned buildings | N/A |

| Crawford, N. D., Borrell, L. N., Galea, S., Ford, C., Latkin, C., & Fuller, C. M. (2013) | n = 143 | n = 638 | Participants were ages of 18 and 40. Injection drug users had to report injecting heroin, crack or cocaine for 4 years or less and at least once in the past 6 months. Non-injection drug users had to report non-injection use of heroin, crack or cocaine for 1 year or more at least 2–3 times a week in the past 3 months | Age, female sex partners, male sex partners, age at sexual debut, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, primary drug used, injection status, female condom use (past 2 months), male condom use (past 2 months), HIV testing frequency (lifetime), lifetime depression, HIV status. discrimination, | Neighborhood minority composition (percent black, percent Latino), poverty (percent living below 100% of the poverty threshold), education (percent less than a high school education) | Drug using ties, heroin injecting ties |

| DePadilla, L., Elifson, K. W., & Sterk, C. E. (2012) | n = 77 | n = 1050 | African American, at least 18 years old, and have resided in the sample neighborhood in the past year | demographics (male/female, age), alcohol use in the past 30 days, crack/cocaine use in the past 30 days, marijuana use in the past 30 days, relationship status/sexual partnership, SES (income, employment, health insurance coverage), perception of social cohesion, perceived neighborhood disorder, knowledge of crime, observed violence | N/A | Lack of condom use during vaginal sex with steady partners |

| Duncan, D. T., Kapadia, F., & Halkitis, P. N. (2014) | n = 122 | n = 598 | Participants eligible for study if 18–19 years old at the time of the baseline assessment, biologically male, lived in the New York City metropolitan area, reported having had sex (any physical contact that could lead to orgasm) with another male in the 6 months preceding the baseline assessment, and self-reported a HIV-negative or unknown serostatus | Race/ethnicity, current school enrollment, perceived familial socioeconomic status, foreign-born status, household composition, sexual identity, in a relationship with another man, housing status, ethnic identity, experiences with gay-related stigma, disclosure of sexual orientation, internalized homophobia, gay community affinity, social support network, self-reported residential, social, and sexual neighborhoods | N/A | Condomless anal, condomless oral intercourse |

| n = 1 | n = 325 | Men, age 18–25, report recent UAI with non-monogamous partner(s), report using drugs (excluding marijuana) on at least three days in the past 90 days or getting drunk three or more times in the past month | Demographics (age, education, income, race/ethnicity, sexual identity), regency of migration to South Florida, health/social risk, victimization history, substance use | N/A | Sexual behaviors (past 90 days) | |

| Egan, J. E., Frye, V., Kurtz, S. P., Latkin, C., Chen, M., Tobin, K., … & Koblin, B. A. (2011) | n = 4 | n = 20 | Male sex at birth, reported insertive or receptive sex with a male partner in the past 6 months, at least 18 years old, reported living in Chelsea/Hell's Kitchen, Harlem, Washington Heights, or Ft. Green for a least 12 months, speak English, and able to provide informed consent | Demographics (age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation), HIV status | N/A (described by participants) | N/A (described by participants) |

| N/A | n = 188 | 18 or older, identify as male, self-report black, or African-American race/ethnicity, report having at least two sex partners in the past three months (one of which must be male), report UAI with a male partner in the past three months, willingness to take an HIV test if negative or unknown status or provide documentation of HIV positive status, and willingness to identify social network members and recruit them into the study | Social network characteristics (number of network members, number of network members to talk to/offer help/loan money or valuables/entrust with money/provide health advice/give support to), sexual partner characteristics (number of male/female sex partners, number of partners met through friends/on internet/bar/social support group/at a party/chat online, number of male/female partners who loan money, to hang out with, see at least weekly; number of HIV positive partners, dependence on partners), social network density, demographic characteristics (age, education, employment status), HIV status, lifetime incarceration | Provided by participants: residential distance from sexual partners (all partners outside the same neighborhood, partners in the same neighborhood but not the same household, partners in the same household) | N/A | |

| Frew, P. M., Parker, K., Vo, L., Haley, D., O'Leary, A., Diallo, D. D. … & Hodder, S. (2016) | n = 10 | n = 288 | Women, ages 18–44 years, residing in Census tracts or zip codes (New York City) in the top 30th percentile of HIV prevalence and > 25% of inhabitants living in poverty, reporting at least one episode of unprotected sex with a man in the six months before enrollment, and also reporting at least one additional HIV risk behavior (either personal or partner). Using venue-based sampling, eligible women were enrolled between May 2009 and July 2010 from 10 communities in six geographic areas of the US (Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; New York City, NY; Newark, NJ; Raleigh-Durham, NC; Washington, DC) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Frye, V., Koblin, B., Chin, J., Beard, J., Blaney, S., Halkitis, P. … & Galea, S. (2010) | n = 113 | n = 385 | Ages 23–29 years, reside in one of the five boroughs of New York City or specified contiguous counties in Long Island, and New Jersey; data from the Young Men’s Study 2 (YMS2), or the aged 23–29 cohort of the YMS-NYC data for both the outcome and individual-level covariate data | Demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income, living situation, zip code, psychosocial factors), "outness" (whether the respondent was known to be gay), venue attendance (ever attended circuit parties and frequency of bar/club attendance), lifetime sexual behavior, sexual behavior over the previous 6 months, history of sexually transmitted diseases, history and most recent results of HIV-1 antibody testing, drug and alcohol use in the past 6 months | Age distribution, racial composition, ethnic heterogeneity, foreign-born presence, concentrated poverty, median household income, percent of high school graduates, percent unemployed, residential instability, vacant housing, and neighborhood gay presence (% of households headed by same-sex partners) | HIV-1 antibodies, hepatitis B, syphilis, and frequency of risk behaviors among MSM |

| Frye, V., Nandi, V., Egan, J. E., Cerda, M., Rundle, A., Quinn, J. W. … & Koblin, B. (2017) | n = 87 | n = 766 | Biological male at birth; at least 18 years of age; reside in NYC; report anal sex with a man in the past 3 months; communicate in English or Spanish; and willing and able to give informed consent for the study | Age, education, employment, income, partnership/marital status, income security, lifetime incarceration, self-reported HIV status, ethnic identity, sexual orientation, outness, partnership status, exposure to neighborhood, kin/friend networks in neighborhood, neighborhood involvement, neighborhood attachment, neighborhood engagement, experience of intimate partner violence | Gay presence, homophobia, vacant housing, broken/boarded-up windows, dirty streets/sidewalks, homicide rate, residential stability, ethnic heterogeneity, homicide rate, poverty | Serodiscordant condomless anal intercourse, five or more sex partners |

| Genberg, B. L., Gange, S. J., Go, V. F., Celentano, D. D., Kirk, G. D., Latkin, C. A., & Mehta, S. H. (2011) | Not reported | n = 1697 | Older than 18 years of age, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-free and had a history of injecting at baseline | Sociodemographics, injection history, lifetime medical history, HIV risk behaviors (sexual and drug-related) and drug treatment history, healthcare utilization, life events (incarceration, homelessness) | Neighborhood deprivation (Percentage of individuals employed in professional/managerial occupations, percentage of households with crowding, percentage of households living in poverty, percentage of female-headed households with dependent children (< 18 years), percentage of households on public assistance, percentage of households earning low income, percentage of individuals with less than high school education and percentage of unemployed males and females (> 16 years)) | 3 Consecutive years without self-reported injection drug use |

| Gindi, R. M., Sifakis, F., Sherman, S. G., Towe, V. L., Flynn, C., & Zenilman, J. M. (2011) | n = 48 | n = 307 | Eligible participants were between 18 and 50 years of age; residents anywhere of Baltimore MSA; male or female (not transgender); reported vaginal or anal sex with a person of the opposite sex in the past 12 months; and had the ability to complete the interview in English | Five most recent sexual partners in the past 12 months; sexual partnerships (residential, demographic, and behavioral); partner concurrency behavior; condom use; race; partner race; age range of partner | Census quartiles of poverty; heterosexually transmitted HIV/AIDS case rates for Baltimore City in 2006 | Census tract of participants and their five most recent partners; asked participants to report whether they met partners "in the neighborhood where they live" |

| Haley, D. F., Haardorfer, R., Kramer, M. R., Adimora, A. A., Wingood, G. M., Goswami, N. D., … & Cooper, H. L. F. (2017) | Not reported | N = 737 | WIHS eligibility criteria included ages 25–60 years old. HIV-infected women were ART naïve or HAART after December 31, 2004; never used didanosine, zalcitabine, or stavudine (unless during pregnancy or for pre- or post-exposure HIV prophylaxis); never been on non-HAART ART, and had documented pre-HAART CD4 counts and HIV viral load | Demographics: age, married or cohabitating, race, annual household income ≤ $18,000, self-rated quality of life (QOL), alcohol or illicit substance use exchange of sex for drugs, money or housing, homeless | Social disorder (i.e., vacant housing units, violent crime rate, STI prevalence, poverty, unemployment) and 2) social disadvantage (i.e., renter-occupied housing and alcohol outlet density) | Condomless vaginal intercourse (CVI), anal intercourse (AI), and condomless anal intercourse (CAI) in the past 6 months |

| Heimer, R., Barbour, R., Palacios, W. R., Nichols, L. G., & Grau, L. E. (2014) | Not reported | n = 454 | Self-reported injection drug use within the past 30 days or evidence of injection stigmata, ≥ 18 years of age, proof of residence for at least 6 months in a Fairfield or New Haven County town, willingness to participate, and competence to provide informed consent | Sociodemographics, drug use history, current injection behaviors, medical history, interactions between with substance abuse treatment/ harm reduction services, social support, spirituality, interactions with criminal justice system; depression (CES-D), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory), alcohol use (AUDIT-C), pain (Brief Pain Inventory); HBV antibodies | Community disadvantage index (CDI), income of Census tract | Unsafe injection risk score |

| Kelly, B. C., Carpiano, R. M., Easterbrook, A., & Parsons, J. T. (2012) | n = 125–132 (across five analytic samples) | n = 710 | Gay identity, geographic locale, and HIV status. Men who reported HIV negative or unknown HIV status | Social network variables (socializes with gay men and gay-centric network); attachment to the gay community; age; education; income; race/ethnicity; relationship status; data collection site | Zip code level: gay neighborhoods (local knowledge and Census data); gay enclave; index of concentration at the extremes (ICE); residential stability | Receptive and insertive unprotected anal intercourse (UAI); barebacking identity; recent internet use for finding sexual partners; Party and Play (PnP) |

| Kerr, J. C., Valois, R. F., Siddiqi, A., Vanable, P., & Carey, M. P. (2015) | N/A | n = 1602 | Eligible participants identified as African American between the ages of 14–17 years old and were participants in a HIV risk reduction intervention | Age, sex, racial background, and eligibility for free or reduced price school lunch, STI acquisition, sexual risk behavior; participant reported neighborhood quality (Neighborhood Stress Index) | Region-based neighborhood quality measures (reported by participants and aggregated by location), region-neighborhood quality dyads | STIs and sexual risk behavior |

| Knittel, A. K., Snow, R. C., Riolo, R. L., Griffith, D. M., & Morenoff, J. (2015) | N/A | n = 250 | Stimulated with incarcerated population | N/A; experimental variables in model: sex ratio, male agent quantity distribution | Rates of incarceration | Male agents—probability of incarceration at each time step; mean and standard deviation of a distribution of sentence lengths (in weeks); probability of relationship break-up at the time of incarceration, probability of starting a new relationship while incarcerated, quality measure decreases as a penalty for incarceration |

| Koblin, B. A., Egan, J. E., Rundle, A., Quinn, J., Tieu, H. V., Cerdá, M., … & Frye, V. (2013) | n = 347 | n = 706 | Participants were eligible if they identified as biological male at birth, were 18 years of age or older, resided in NYC, reported engaging in anal sex with a man in the past 3 months, spoke English or Spanish, and were willing and able to give informed consent for the study | Demographics, general and HIV-related health questions (e.g. HIV testing history, occurrence of STIs), history of incarceration and sexual identity, sexual behaviors in the 3 months prior to the study (number of partners, number of insertive and receptive anal sex acts and use of condoms and partner HIV status), self-reported neighborhood characteristics and definition (boundaries) | Borough of residence, neighborhood (pre-defined, historic name), and boundaries; socioeconomic status, housing quality, ethnicity, residential stability, crime rates, and cleanliness of streets and sidewalks, neighborhood safety (geocoded assaults), access to public transportation, land use mix, location and quality of parks, green space, location of recreation facilities, unexpected deaths (geocoded from NYC Medical Examiner) | Sexual risk behaviors, substance use, and depression among MSM in NYC |

| Koblin, B. A., Egan, J. E., Nandi, V., Sang, J. M., Cerda, M., Tieu, H.-V.,... Frye, V. (2017) | n = 347 | n = 1493 | Eligible participants identified as biological male at birth, at least 18 years of age, resided in NYC, reported engaging in anal sex with a man in the past 3 months, communicated in English or Spanish | Age; race/ethnicity; sexual identity; socioeconomic status (education, employment, annual personal income, and financial security); outness (how many of the people you know or see day-to-day know you have sex with men?); gay community attachment; place of birth; place where participant spent most of their life; whether the participant would live in their current home neighborhood if they could live anywhere in NYC; Neighborhood Locator Questionnaire, neighborhood congruence; social ties, neighborhood connectedness, neighborhood lifetime and recent experiences | N/A | Serodiscordant/unknown status condomless anal intercourse (serodiscordant CAI); CAI with partners found using the Internet or mobile application |

| Latkin, C. A., Curry, A. D., Hua, W., & Davey, M. A. (2007) | N/A | n = 838 | 18 years of age or older, daily or weekly contact with drug users, willingness to conduct AIDS outreach education, willingness to bring network members to be interviewed, not currently enrolled in other HIV prevention studies | Demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity), HIV status, employment, incarceration, housing, education, use of public assistance; Perkins and Taylor's Block Environmental Inventory, psychological distress (CES-D), sexual risk behaviors (number of partners, sex with someone who used injection drugs, sex with someone who used crack cocaine), injection drug or crack cocaine use | N/A | Psychological distress and sexual risk behavior |

| Lutfi, K., Trepka, M. J., Fennie, K. P., Ibanez, G., & Gladwin, H. (2015) | n = 110 | n = 3643 | Completed the National Survey of Family Growth 2006–2010 survey, identified as non-Hispanic black race | Age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, and income; risky sexual behavior (number of partners in the past 12 months, condom used at last sex, and composite measure of these two) | Census-level: racial residential segregation ( index of dissimilarity, isolation index, relative concentration index, absolute centralization index, spatial proximity index), hypersegregation; CBSA-level: racial residential segregation and poverty | Sexual behaviors |

| Martinez, A. N., Lorvick, J., & Kral, A. H. (2014) | Not reported | n = 1084 | Being aged 18 years or older and drug injection within the past 30 days (self-reported) | HIV serostatus; syringe sharing; non-fatal overdose in the past 12 months; gender (male and female); age (under 30 vs. older age); race/ethnicity; sources of income (government assistance or illegal means) in the past 30 days, years of injection drug use, and homeless status. Arrest history; injection and non-injection drug use (heroin, methamphetamine, and crack smoking); trading sex for cash or drugs, and frequency of syringe exchange program use | Activity spaces: routes, activity space distances, syringe program locations; Census tract: poverty level, dichotomized poverty (high vs low), concentrated poverty | HIV serostatus, syringe sharing, non-fatal overdose |

| Mustanski, B., Birkett, M., Kuhns, L. M., Latkin, C. A., & Muth, S. Q. (2015) | n = 77 | n = 167 (egocentric network) n = 837 (alters) | 16–20 years old, born male, spoke English, had a sexual encounter with a male or identify as gay/bisexual, and available for follow-up for 2 years | Name generator, demographic characteristics (age, race [mutually exclusive], gender, perceived sexual identity, cross streets or neighborhood residence), characteristics of the relationship, and behaviors with that person, sexual behavior from prior 6 months, HIV and STI (gonorrhea and Chlamydia) test results, relationship type, concurrency | HIV prevalence, network density, multiplexity, assortativity by race | Individual and sexual network characteristics |

| Nandi, A., Glass, T. A., Cole, S. R., Chu, H., Galea, S., Celentano, D. D.,... Mehta, S. H. (2010) | n = 174 | n = 1875 | Participants initially recruited into the AIDS Link to Intravenous Experiene (ALIVE) cohort study: individuals were eligible if they reported injection drug use within the past 11 years, were at least 8 years of age, and, were AIDS free upon study enrollment (for HIV-positive participants); added requirement for identifiable address for enrollment in this study | Sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, employment in the formal economy, formal income), drug use characteristics (age at first injection, needle sharing, crack use, shooting gallery attendance), sexual behaviors, medical history (HIV status, presence of any sexually transmitted diseases), health care utilization (methadone treatment usage), and life events (homelessness, jail/incarceration) | Neighborhood poverty levels (% of residents living in poverty) | Drug use cessation |

| Neaigus, A., Jenness, S. M., Reilly, K. H., Youm, Y., Hagan, H., Wendel, T., & Gelpi-Acosta, C. (2016) | n = 42 | n = 494 | Participants must identify as heterosexuals at high risk of HIV (having had vaginal or anal sex with opposite gender partners in the past 12 months), self-identified as male or female, aged 18–60 years, residing in NYC, being able to complete the interview in English or Spanish, and not previously participating in the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system in the hererosexual cycle (HET2) | Sociodemographic characteristics, drug and alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors and partnerships, and other HIV-related information; blood specimens for HIV antibodies | Zip code of closest street internstion of the place where they last had sex with up to 6 of their most recent partners in the past 12 months; HIV prevalence by NYC communities | N/A |

| Pachankis, J. E., Eldahan, A. I., & Golub, S. A. (2016) | N/A | n = 273 | 18–29 years, having moved to NYC in the past 12 months, and identifying as gay or bisexual man | Sexual identity, education, employment status, class background, relationship status, and HIV status, hometown characteristics—hometown size, outside USA, hometown structural stigma, and hometown interpersonal discrimination | Same-sex couple households (US Census) | HIV transmission risk (condomless vaginal or anal sex with serodiscordant and unknown-status partners), heavy substance use (used marijuana more than once per week on average or any other drug more than once per month), alcohol use (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test (AUDIT)), depression and anxiety (Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)) |

| Parrado, E. A., & Flippen, C. (2010) | n = 32 | n = 1446 | Hispanic male immigrants living in one of 32 apartment complexes, who answered the door and were eligible, | Age, years of education, wages, marital status—single men, accompanied married men (who reside with a spouse), and unaccompanied married main (whose wives continue to reside in their communities of origin), | Median wages, the share of migrants who were recently arrives (with less than 3 years in the Durham area), race and ethnicity (to determine the share of the apartment complex population that is not Hispanic) | Self-reported commercial sex worker (CSW) |

| Quinn, K., Voisin, D. R., Bouris, A., & Schneider, J. (2016) | N/A | n = 92 | Being born biologically male, self-identifying as Black or African American, between the ages of 18 and 29, inclusive, having an HIV diagnosis for greater than three months, and having disclosed their status to at least one person in their close social network | Demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity), education, employment; participant reported exposure to community violence (Exposure to Violence Probe) | N/A | Substance use (frequency of substance use in the past 3 months), medication adherence (currently taking ARVs, medications prescribed for HIV, number of days with missed medication in the past 30 days, percent of days medication was taken in the past 30 days), psychological distress (Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)—18), sexual risk behaviors (use of substances for sex, condomless anal intercourse) |

| Raymond, H. F., Al-Tayyib, A., Neaigus, A., Reilly, K. H., Braunstein, S., Brady, K. A., … & German, D. (2017) | n = 13 | n = 6137 | Participants identified as 18 years or older, lived in one of the study cities, and reported ever having had sex with a man | Transmission risk group variables: sexual partners (only having male partners; male and female partners; female partners only but identified as gay/bisexual), sexual orentation; IDU as only risk; male and female partners and IDU; IDU and male partners; female partners and IDU; none of the above behaviors in the past 12 months | HIV case reporting data; city poverty level; race/ethnicty | Transmission risk behaviors; HIV case reporting data |

| Raymond, H. F., Chen, Y. H., Same, S. L., Catalano, R., Hutson, M. A., & McFarland, W. (2014) | N/A | n = 523 | 18 or older, identify as Black, has valid study referral coupon, identify as gay or bisexual or has had at least 1 male partner in the pas 12 month, male, resident of San Francisco | Race, age, income, education, neighborhood of residence, often risk taking, per contact risk of acquiring HIV, sexual behavior, stimulant, SES | Neighborhood HIV prevalence | HIV acquisition risk from sex and drug use |

| Rothenberg, R. B., Dai, D., Adams, M. A., & Heath, J. W. (2017) | Not reported | n = 927 |

18 years or older, being involved in HIV risk- taking, either through use of drugs or sexual activity, and who communicated a willingness to name and discuss their partners |

Age, race, marital status, education, religious affiliation, employment, homelessness, sources of income, criminal justice system involvement, threatened with weapon, general health status, sexual orientation, STD history, drug use, sexual behavior | Compound risk indicator (e.g. number of sex partners, injection drug use, anal sex, sex with IDU, sex work); geographic areas delineated by higher and lower risk | Social and geographic distance (network) |

| Rudolph, A. E., Crawford, N. D., Latkin, C., Fowler, J. H., & Fuller, C. M. (2013) | Not reported | n = 378 | 18–40 years old and were active injection or non-injection drug users | Demographics, network characteristics and relationships, drug use and sex behaviors, and health service use | Minority composition, educational attainment, unemployment, income/poverty, inequality, and crowding | Membership in high HIV prevalence drug networks |

| Rudolph, A. E., Linton, S., Dyer, T. P., & Latkin, C. (2013) | Not reported | n = 417 | Females (18–55 years of age) who had not injected drugs in the past 6 months, self-reported heterosexual sex in the past 6 months, and had > = 1 of the following sexual risk factors: (A) > 2 partners in the past 6 months, (b) STD diagnosis in the past 6 months, or (c) a high-risk sex partner in the past 90 days/ | Age, race (African American vs. other), incarceration in the past 6 months, weekly alcohol use, employment status in the past 6 months, HIV status, marital status, current main sex partner, cocaine metabolites, opiate metabolites, education, heroin use in the past 6 months, crack/cocaine use in the past 6 months, and homelessness in the past 6 months, social network, sexual network; perception of neighborhood | N/A | Exchange sex |

| Senn, T. E., Walsh, J. L., & Carey, M. P. (2016) | Not reported | n = 1010 | Age 16 or older, engaged in sexual risk behavior in the past 3 months | Sex, age, race, income, education, employment, health behaviors, exposure to violence | Per capita income in the Census tract, percentage of individuals with a college education in the Census tract, | Community violence with sexual risk behavior |

| Sterk, C. E., Elifson, K. W., & Theall, K. P. (2007) | N/A | n = 65 | Eligible participants were 18 years or older; identified as heterosexually active African American women who reported drug use; resided in one of the study communities; reported that they were out of drug treatment or any other institutional setting, spoke English, and reported HIV-negative status. Participants also were eligible if they had vaginal sex with a man at least once during the month prior to the interview and reported active drug use | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Stevens, R., Gilliard‐Matthews, S., Nilsen, M., Malven, E., & Dunaev, J. (2014) | N/A | n = 30 | 13 to 24 year old females, English speaking, living in the study city, and self-identified as African American and/or Latina | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Stevens, R., Icard, L., Jemmott, J. B., O'Leary, A., Rutledge, S., Hsu, J., & Stephens-Shields, A. (2017) | n = 321 | n = 564 | Men were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years of age, self-identified as black or African American, were born a male, and reported having anal intercourse with a man in the previous 90 days | High school non-completion, income, and problem drug use | High school non-completion, neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics | Transactional sex |

| Tobin, K. E., Latkin, C. A., & Curriero, F. C. (2014) | n = 1 | n = 51 | Participants were eligible if they were ages 18 years old or older; self-reported African American race/ethnicity; self-reported male sex; self-reported sex with a male in the prior 90 days; reported living address within Baltimore City | Age, highest educational attainment, current employment status, sexual identity; HIV status, sexual orientation, employment status, whether the network knows that the Index has sex with men; where they spend their time; relationship/attribute items for place-based socio-spatial inventory (see neighborhood measures) | Street intersections and latitude/longitude of: places of residence, socializing, meeting with sex partners and work; drug and alcohol use places within Baltimore City (spatial clustering) | Social network characteristics of drug and alcohol use |

| Tobin, K. E., Hester, L., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Latkin, C. A. (2012) | Not reported | n = 720 | Eligible participants were 18 years and older, self-reported injection drug use in the prior 6 months, reported current drug use, or sex partner of study referent | Age, sexual identity, employment, homeless, incarceration, injection drug use, crack use, sex exchange, peer norms regarding sex exchange | Median household income, percent minority, percent rental, percent in labor force, violent crime | Sex exchange (having sex in exchange for drugs, money, food or shelter in the prior 90 days) |

| Voisin, D. R., Hotton, A. L., & Neilands, T. B. (2014) | N/A | n = 563 | Students were eligible for participation in the study if they self-identified as African American, were between the ages of 13–19 years, and were attending regular high school classes (i.e., non-special education classes) | Gender, exposure community violence, student–teacher connectedness (Student Assessment of Teachers Scale), school engagement (GPA), Risky peer norms, History of gang involvement, internalizing or externalizing behaviors and withdrawal (Youth Self-Report (YSR) Survey), PTSD (University of California at Lost Angeles' PTSD Reaction Index (UCLARI)), negative perceptions of peer attitudes about safer sex, gang membership, sexual behaviors | N/A | Sexual behaviors |

| Williams, C. T., & Latkin, C. A. (2007) | n = 249 | n = 1305 | Participants were eligible for this study if they were at least 18 years old; having regular contact with drug users; willingness to conduct peer outreach; and willingness to bring in 1 to 2 network members | Age, gender, education, employment, and income (control variables); participant's partner score on a depression screening instrument, and self-reported HIV status; depressive symptoms (CES-D); drug use; and network inventory (characteristics of total network) (not reported but sample was primarily African American) | Percent in poverty, percent receiving public assistance, percent unemployment, percent with low educational level, percent female-headed households, median household income, neighborhood disadvantage (as a composite measure), percent of persons not in the labor force, percent vacant housing, percent of blue collar and professional occupations, percent renters, and percent disabled | Any use (versus no use) of heroin, cocaine, or crack within the past year |

Relationships Between Neighborhood-Level Factors and HIV Vulnerability

Multiple neighborhood-level factors were associated with heightened HIV vulnerability, but this relationship varied by key factors including how neighborhood condition was defined (objective vs subjective) and whether HIV vulnerabilities stemmed from drug use or sexual risk behavior (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Study results and future directions

| Article citation | Sample description | Key findings/conclusions | Future directions |

|---|---|---|---|