Abstract

We report the first case of Chrysosporium zonatum infection in a 15-year-old male with chronic granulomatous disease who developed a lobar pneumonia and tibia osteomyelitis while on prophylaxis with gamma interferon. The fungus was isolated from sputum and affected bone, and hyphae were observed in the bone by histopathology. Therapy with amphotericin B eradicated the osteomyelitis and pneumonia, but pneumonia recurred in association with pericarditis and pleuritis during therapy with itraconazole. These manifestations subsided, and no recurrences occurred with liposomal amphotericin B therapy. Infections caused by Chrysosporium species are very rare, and C. zonatum has not previously been reported to cause mycosis in humans. This species, the anamorph of the heterothallic ascomycete Uncinocarpus orissi (family Onygenaceae), is distinguished by its thermotolerance, by colonies which darken from yellowish white to buff, and by club-shaped terminal aleurioconidia borne at the ends of short, typically curved stalks. The case isolate produced fertile ascomata in mating tests with representative isolates. The median (range) MICs for our isolate as well as those for two other human isolates and a nonhuman isolate determined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method adapted for moulds were ≤0.06 μg/ml (≤0.06 to 0.25 μg/ml) for amphotericin B, 0.687 μg/ml (0.25 to 2 μg/ml) for itraconazole, >128 μg/ml (>128 μg/ml) for flucytosine, and 48 μg/ml (32 to >128 μg/ml) for fluconazole.

Fungal infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients including those with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a congenital disease that causes immunodeficiency. GCD is due to a phagocytic defect in NADPH-mediated oxidative burst that induces susceptibility of the host to many catalase-positive organisms including certain fungi. Aspergillus fumigatus is the single most common cause of fungal infections in these patients (5). Other rare and emerging fungi can, however, cause significant diseases (2, 6, 12, 13, 23, 33, 34, 38).

Members of the genus Chrysosporium are common soil saprobes, many of which are keratinophilic fungi involved in the breakdown of shed keratinous substrates. Such fungi are occasionally encountered in the diagnostic laboratory predominantly as contaminants of cutaneous or respiratory specimens, in which they may mimic true dermatophytes or the dimorphic pathogens (27). In humans, there are only rare reports of deep infection caused by species of Chrysosporium, and most of these are difficult to evaluate because the etiologic agent has not been well described (9, 15, 31, 35–37). Moreover, some confusion has occurred among reports in the literature concerning adiaspiromycosis because the etiologic agents of this infection were formerly considered to be members of the genus Chrysosporium. Adiaspiromycosis, characterized by the development of large, thick-walled spores (adiaspores), occurs primarily as a pulmonary infection in rodents and other small mammals and rarely in humans. The infection is caused by species of the genus Emmonsia, E. crescens and E. parva (25). Emmonsia species have been shown to be biological relatives of the dimorphic fungi Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum, as judged by the formation of meiotic (sexual) stages in the genus Ajellomyces and by comparison of nucleic acids (3, 10, 22, 25, 26).

The fungus isolated from our patient’s disseminated infection is Chrysosporium zonatum. This organism recently has been proven to have a meiotic stage in the ascomycete genus Uncinocarpus (family Onygenaceae), the type species of which has Coccidioides immitis as a close relative (3, 21, 30). To our knowledge, this is the first case of infection due to C. zonatum reported in humans and the first case of infection caused by a Chrysosporium species in a CGD patient. We use this patient’s case to review other reports of non-Aspergillus fungal infections in CGD patients.

CASE REPORT

A 15-year-old male with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease was admitted to the hospital for a lobar pneumonia. His past history was significant for a staphylococcal pneumonia at the age of 8 years and a granulomatous soft-tissue infection due to Serratia marcescens with a fever of several months’ duration at the age of 12 years. The last infection was also the one that led to the diagnosis of CGD in him and his younger brother. Prophylactic therapy with 50 μg of gamma interferon per m2 three times weekly had been initiated 2 months earlier.

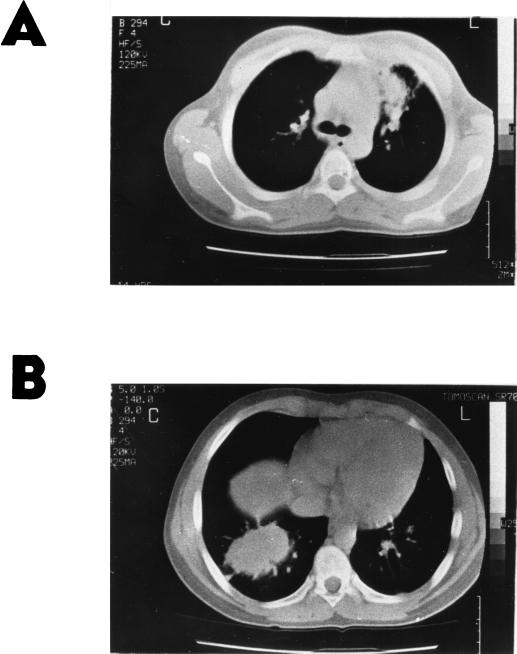

The patient presented with pain in his right shoulder and an infrequent cough of approximately 1 month in duration and with a fever for the last 24 h. On physical examination at admission, a temperature of 39°C was found and crepitant rales were audible above his right lung. A chest X ray revealed a lobar opacity in the lower right lung field and widening of the left hilum. The initial laboratory findings included a mild leukocytosis (9,300 leukocytes/mm3 with 80% neutrophils) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 119 mm in the first hour. Intravenous antibacterial therapy consisting of cefuroxime and clindamycin was promptly initiated, and the patient exhibited improvement of his symptoms. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a well-demarcated large mass in the right lower lobe, enlarged left hilar lymph nodes, and lingular pneumonitis (Fig. 1). A culture of a sputum sample taken at admission grew a Chrysosporium species.

FIG. 1.

Chest CT. (A) Enlarged left hilar lymph nodes and lingular pneumonitis. (B) Right lower lobe mass.

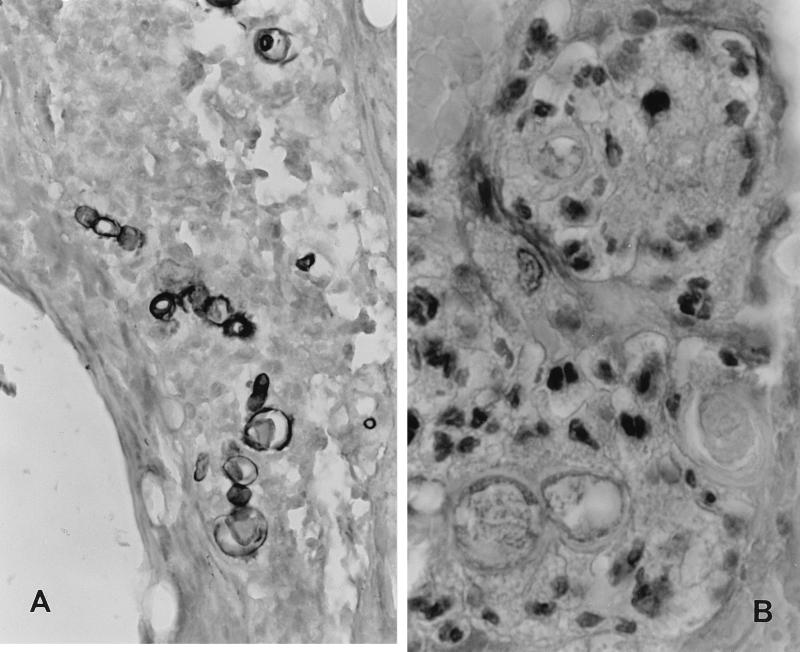

During the second week of antibacterial therapy, the patient complained of pain of the distal part of his right tibia, where swelling and warmth were also evident. A tibia X ray was diagnostic for osteomyelitis. A biopsy of the tibia lesion revealed granulomatous tissue. In addition, a few short and thick hyphae were observed in the bone site by histopathology (Fig. 2). Cultures of the bone biopsy specimen yielded the same fungus that had grown from the patient’s sputum and were negative for bacteria. Both isolates were subsequently identified as C. zonatum. Antifungal therapy with 1 mg of amphotericin B per kg of body weight daily was initiated, and the antibacterial drugs were discontinued.

FIG. 2.

Histopathological findings from tibia osteomyelitis. (A) Silver methenamine stain. Magnification, ×680. Polymorphic fungal elements can be seen in the midst of inflammatory infiltrate of tibia lesion. (B) Hematoxylin-eosin stain. Magnification, ×1,600. In the midst of inflammatory cells, fungal elements (three of them in the lower part of the picture) with a thin capsule and a fine basophilic internal structure can be recognized.

After 4 weeks of therapy with amphotericin B, the patient’s pulmonary infection was improved. His tibia osteomyelitis was resolved and did not recur during follow-up of more than a year. A new chest CT scan showed almost complete disappearance of the right lower lobe mass and decrease of the lymph nodes. Amphotericin B was discontinued, and oral therapy with 8 mg of itraconazole/kg/day was initiated. However, infection recurred, as evidenced by a new fever and increased opacities on the left thorax, and therapy was changed to amphotericin B. Three and a half months after the initial presentation, a chest CT scan showed that the lobar pneumonia was totally resolved except for very small linear opacities considered to be fibrotic tissue. Due to entire healing of the osteomyelitis and pulmonary infection as well as renal impairment, therapy with amphotericin B was discontinued and itraconazole was again initiated with instructions for maximal absorption.

The MICs for the bone isolates (median of five determinations), as measured by a modification of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) method adapted for moulds (8), were 0.25 μg/ml for amphotericin B, 2 μg/ml for itraconazole, >128 μg/ml for flucytosine, and 32 μg/ml for fluconazole. Serum itraconazole concentrations were not measured. After 5 weeks of therapy with itraconazole, thoracic infection recurred and was manifested as pneumonia, pericarditis, and pleuritis. Itraconazole was discontinued and therapy with amphotericin B and methylprednisolone was promptly initiated. Studies for infection due to coxsackievirus and other viruses were negative. Due to a rapid increase in the patient’s serum creatinine level to >176 μmol/liter (>2.0 mg/dl), conventional amphotericin B was replaced by liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 5 mg/kg every day. No recurrences occurred after that. Methylprednisolone was gradually discontinued after 15 days. The patient’s condition improved, and approximately 4 weeks after the initiation of liposomal amphotericin B, therapy with this compound started to be gradually decreased to 5 mg/kg every other day for 4 additional weeks, three times a week for 6 weeks, two times a week for 4 weeks, and once a week to the completion of a total of 1 y of antifungal therapy. Eight months after the discontinuation of therapy, the patient is doing well and continues to receive prophylactic gamma interferon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification.

The isolate from bone was sent to the University of Alberta Microfungus Collection and Herbarium (UAMH), where it was deposited as strain UAMH 8936. Strain UAMH 8936 was included in a taxonomic and mating study assessing the relationship among and between 20 wild-type isolates preliminarily identified as Pseudoarachniotus orissi, Gymnoascus arxii, C. zonatum, Chrysosporium gourii, or Chrysosporium sp. strain IX and 4 single-ascospore isolates derived from a cross of UAMH 4427 and UAMH 6500 (30). Colonial morphology and growth rate were assessed on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 25 and 37°C, and tolerance to cycloheximide at 400 μg/ml was tested by measuring the growth rate at 25°C on Mycosel agar (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.). Terms for colony colors are from Kornerup and Wanscher (14). Microscopic morphology was examined in slide culture preparations with pablum cereal agar (27). The patient’s isolate was also evaluated for its growth on BCP-milk solids-glucose agar and in Christensen’s urea broth (11) and for its capacity to degrade human hair by previously described methods (27). Because the case isolate was received near the completion of the larger taxonomic study, it was evaluated in mating tests involving only plus (UAMH 6635) and minus (UAMH 6636) mating strains and two wild-type isolates from human sources (strains UAMH 9067 and UAMH 9068) by previously described methods (30).

In vitro susceptibility testing.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed in the Infectious Diseases Laboratory at the University of Thessaloniki with the case isolate, two isolates (strains UAMH 9067 and UAMH 9068) that colonized the lung cavities of patients (32), and an isolate from a nonhuman source (strain UAMH 6635). The MICs of amphotericin B, flucytosine, itraconazole, and fluconazole were determined by a modification of the NCCLS method adapted for moulds (8, 19). Briefly, isolates and controls were grown on PDA at 35°C for 2 to 3 days and were then conidiated at room temperature for a total of 7 days. Stock drug solutions to be used were placed in the wells of 96-well plates. Twofold dilutions of the drug solutions were made in RPMI 1640 containing 2% glucose buffered with morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) to pH 7.0. A suspension of 5 × 104 conidia of each isolate per ml was prepared after counting of the conidia with a hemocytometer. The suspension was added to the wells, and the mixtures were incubated at 35°C. Each row of the plates contained 10 twofold serial dilutions of each antifungal agent and drug-free medium in wells 11 and 12 as a sterility check and as a growth control, respectively. Plates were examined for growth at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Results are the recordings at 72 h, which were considered optimal. MICs were defined as the lowest concentration of the antifungal agent that completely inhibited visible fungal growth. As standard quality control strains, A. fumigatus ATCC 9197 and Paecilomyces variotii ATCC 22319 (kindly provided by Juan-Luis Rodriguez-Tudela) were included in the assay. Optically clear wells were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates and incubated at 35°C for 72 h. Minimum lethal concentrations were defined as the lowest concentration of the antifungal that completely inhibited the growth of fungal colonies.

RESULTS

The case isolate (UAMH 8936) was identified as C. zonatum by its colonial and microscopic features. Colonies (Fig. 3) on PDA at 37°C were flat and coarsely powdery and initially appeared yellowish white (4A2) but darkened by 14 to 21 days to buff (greyish [5B] or brownish [6C4] orange) with a light brown reverse (numbers in parentheses and brackets refer to color numbers from reference 1). Colony topography and color on PDA were similar at 37 and 25°C, but darkening of the colony obverse and growth rate were slightly faster at 37°C (diameter, 73 mm in 14 days) than at 25°C (diameter, 66 mm). The isolate was resistant to cycloheximide, as judged by its growth on Mycosel medium (diameter, 58 mm in 14 days at 25°C), and it produced urease and vigorously digested hairs, with the formation of perforating bodies. On BCP-milk solids-glucose agar after 11 days, it grew profusely and showed no pH change.

FIG. 3.

Colony of C. zonatum UAMH 8936 (case isolate) on PDA after 14 days at 37°C. Magnification, ×0.8.

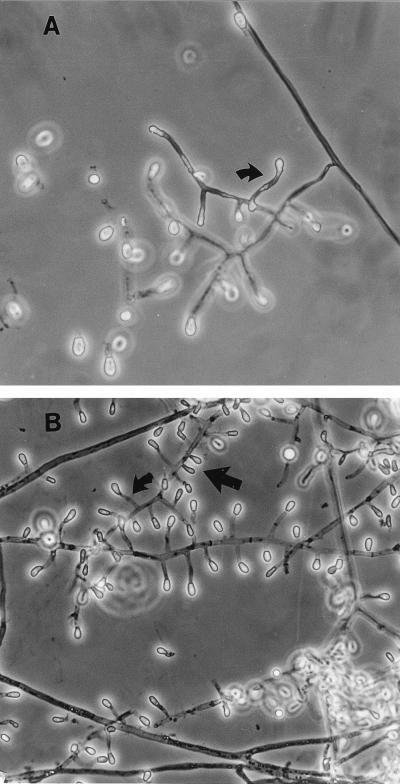

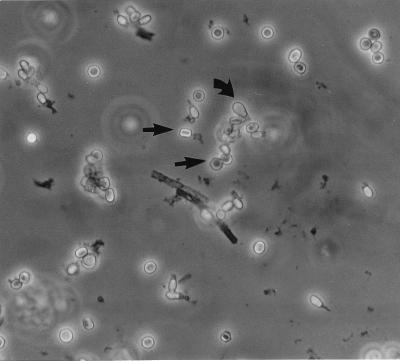

Microscopically, the isolate forms solitary aleurioconidia that are borne at the ends of short, typically curved stalks or that are sessile (borne on the sides of the hyphae) (Fig. 4). Conidia are single celled, rarely two celled, smooth to slightly roughened, and clavate (club shaped) to broadly obovoid (egg shaped) and have a rounded tip and a broad, flat basal scar. They measure (3.5) 4 to 8 (13) μm long and (2.5) 3 to 5 μm wide. Intercalary arthroconidia may be formed but are uncommon. Racquet hyphae (hyphae showing swellings near the septa) are common. In mating tests, the case isolate was determined to be of the minus mating type as a result of its formation of ascomata and ascospores (Fig. 5 and 6) in a pairing with a plus mating strain (UAMH 6635) of Uncinocarpus orissi and with a wild-type isolate from another human source (UAMH 9068).

FIG. 4.

Microscopic appearance of C. zonatum in slide culture preparations showing aleurioconidia borne at the tips of short, typically curved stalks (curved arrow) or sessile (straight arrow). (A) Case isolate (UAMH 8936). Magnification, ×580. (B) Isolate with a single ascospore (UAMH 6635). Magnification, ×460.

FIG. 5.

Oblate (appearing flattened in the side view and spherical in the face view) ascospores (straight arrow) of the sexual stage of U. orissi and detached conidia of the C. zonatum stage (curved arrow). Ascospores were formed in a mating between the case isolate (UAMH 8936) and an isolate with a single ascospore (UAMH 6635). Magnification, ×580.

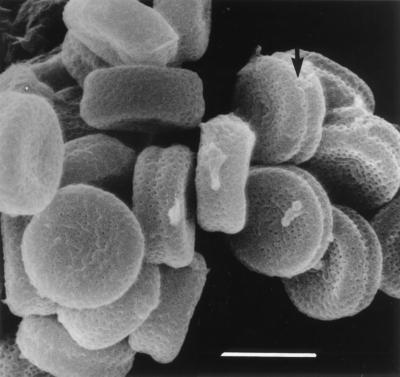

FIG. 6.

Scanning electron microscopic appearance of oblate ascospores of a cross of strains UAMH 6499 and UAMH 6500 reveals minute surface pits (puncta) and a shallow equatorial furrow (arrow). Bar, 4 μm.

The MICs for the human and nonhuman isolates are presented in Table 1. By current methods, the four tested isolates are susceptible in vitro to amphotericin B (MIC range, ≤0.06 to 0.25 μg/ml) and resistant to flucytosine and fluconazole (MIC range, >128 μg/ml and 32 to >128 μg/ml, respectively). The itraconazole, MIC range was 0.25 to 2 μg/ml, and the MIC for the isolate from our patient was the highest one.

TABLE 1.

Drug susceptibility data for human and nonhuman isolates of C. zonatuma

| Isolate source | Isolate | MIC (μg/ml)

|

MLC (μg/ml)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmB | 5FC | Flu | Itra | AmB | 5FC | Flu | Itra | ||

| Human | UAMH 8936b | 0.25 | >128 | 32 | 2 | 0.25 | >128 | ND | ND |

| UAMH 9067 | <0.06 | >128 | >128 | 1 | <0.06 | >128 | ND | ND | |

| UAMH 9068 | <0.06 | >128 | >68 | 0.56 | <0.06 | >128 | ND | ND | |

| Nonhuman | UAMH 6635 | <0.06 | >128 | >68 | 0.25 | <0.06 | >128 | ND | ND |

AmB, amphotericin B; 5FC, flucytosine; Flu, fluconazole; Itra, itraconazole; ND, not determined.

Case isolate.

DISCUSSION

C. zonatum has not previously been reported to cause infections in humans and the case of C. zonatum infection described here constitutes the first report of an infection caused by a Chrysosporium species in a CGD patient. C. zonatum caused in our patient a disseminated infection that included pneumonia, pleuritis, pericarditis, and osteomyelitis. The pneumonia appeared to be solitary, although during recurrence, the infectious process was also manifested as inflammation of the surrounding tissues, i.e., pericarditis and pleuritis.

The infection may have been acquired by exposure to airborne conidia, since the patient had many outdoor activities in the yard of his family’s countryside house, where he was exposed to soil organisms. Pulmonary colonization by C. zonatum has been observed in two Japanese patients with suspected prior tuberculosis (32). In these patients, chest X ray or CT scan revealed opacities consistent with possible fungal infection, and C. zonatum was isolated from respiratory specimens. Similarly to our patient, both Japanese patients received itraconazole therapy without improvement, but one patient’s symptoms resolved following cavitary infusion of amphotericin B. The other patient died during the course of therapy, and no autopsy was done.

Our susceptibility data suggest that the organism is susceptible to amphotericin B but moderately resistant to itraconazole, as judged by NCCLS interpretative guidelines for yeasts (19); however, standardized values are not yet available for filamentous fungi, and evaluation of the relationship between in vitro drug susceptibility results and in vivo outcome is under intense research (8, 20). For the four isolates tested, itraconazole MICs were 0.25 to 2 μg/ml, and the MIC for our patient’s isolate was the highest one. This finding appears to correlate with the course of his infection, since therapy with itraconazole was twice followed by exacerbation of his disease. However, it is uncertain that exacerbation was due to a lack of in vivo activity of itraconazole because (i) drug concentrations were not measured (although the patient received the drug according to instructions for maximal absorption) and (ii) the exacerbation of symptoms might have been due to excessive inflammation rather than to a recurrence of infection. It is known that CGD causes excessive inflammation even in response to dead hyphae (17). Because our data suggest that the current azoles may not be clinically active against the organism, we recommend that they should not be used empirically or even on the basis of in vitro antifungal susceptibility results until susceptibility testing methods for moulds are well standardized and their results are correlated with the clinical outcome. Investigational antifungal agents that have no significant toxicity and that can be used as an oral formulation, including the new azole voriconazole, also need to be studied for activity against this rare filamentous fungus to determine if they can be used as alternatives to amphotericin B.

Excluding reports concerning adiaspiromycosis (25), there are few reports of deep infection that have involved Chrysosporium species (31). Endocarditis in a prosthetic aortic valve (36); disseminated infection that involved the brain, lungs, sinuses, liver, and kidneys in a bone marrow recipient (37) and that has subsequently been mentioned incidentally (9, 18); osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent host (35); and sinusitis (15) have been reported. However, none of these reports identified the etiologic agent to the species level or mentioned whether the case isolates were deposited so that further evaluations could be done. Toshniwal et al. (36) described the hyphal swellings present in a histologic section of the valve vegetation as adiaspores, but their Fig. 1 shows abundant hyphae and the general appearance of the structures is not compatible with typical adiaspores. Although the fungus illustrated and described by Warwick et al. (37) clearly represents a species of Chrysosporium, its restricted growth at 37°C compared with growth at 25°C suggests that their isolate was not C. zonatum, nor was it similar to E. parva, as they stated. The fungus causing the osteomyelitis reported by Stillwell et al. (35) has been attributed to E. parva in several subsequent papers (e.g., see reference 37), but the original authors neither mentioned this species nor reported the presence of adiaspores. Rather, they reported the presence of “budding cells and septate mycelia.” The report by Echavarria et al. (7) is the only one identifying E. parva as a causative agent of osteomyelitis in a patient with AIDS. Chrysosporium species (15) and Myriodontium keratinophilum (16, 27) have been implicated as agents of sinusitis, but Sigler and Kennedy (31) have suggested that the fungi involved may have been misidentified Schizophyllum commune, a basidiomycete that has invasive potential and that is being recognized as an emerging agent of sinusitis (24, 31).

Patients with CGD suffer from frequent and serious bacterial and fungal infections. A. fumigatus is the leading cause of fungal infection (5). Reports of other fungal infections are very few. In Table 2 we review eight cases of non-Aspergillus fungal infections previously reported in CGD patients together with the case described here. Of these, four were caused by species of Paecilomyces, making this mould the second most frequent cause of fungal infection in CGD patients; however, the reason for this frequency is unclear. The remaining five infections were caused by a variety of filamentous or yeast-like fungi. While four of the infections were disseminated to multiple body sites, in general they affected lungs (six cases), soft tissues and skin (four cases), bones (three cases), and brain (one case). All nine patients suffered from CGD; three patients had CGD of the X-linked form, three had CGD of the autosomal recessive form, and three had CGD of unreported form. Only two of them had been treated with gamma interferon prophylactically for 2 and 6 months, respectively, before the infection. Of note, none of the patients who suffered from a non-Aspergillus fungal infection had been treated with gamma interferon for longer than 6 months. In the patient described here, it is possible that the mould had infected the patient at about the time of or before the initiation of prophylactic therapy since he was complaining of infrequent cough and pain in his right shoulder for at least a month before his admission to the hospital.

TABLE 2.

Non-Aspergillus fungal infections in CGD patientsa

| Patient no. | Refer-ence | Age (yr) at time of infection | Sex | Genetic type of CGD | IFN-γb | Infection | Fungus | Mode of diagnosis | Antifungal therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 18 | M | No | Multifocal osteomyelitis and multiple skin lesions | Paecilomyces variotii | Culture (SDA and BHI) and histo-pathology of bone biopsy specimen | AmB (1.5 g/kg total dose) plus IFN-γ (50 μg/m2 three times/wk); subsequently, Itra (200 mg/day) plus IFN-γ for 1 yr | Alive | |

| 2 | 38 | 8 | M | Autosomal recessive | Yes (started 6 mo prior) | Soft tissue swelling in the right heel | Paecilomyces variotii | Culture (SDA) and histopathology of soft tissue biopsy specimen | AmB (40 mg/kg total dose in 7 wk); subsequently, Itra (200 mg/day for 12 mo) | Alive |

| 3 | 34 | 4 | M | X linked | No | Abdominal wall abscesses | Paecilomyces lilacinus | Positive culture of two biopsy speci-mens with granulomatous tissue but not fungal elements on histo-pathology | AmB (25.5 mg/kg total dose in 2 mo) | Recovered but died 4 mo later from A. fumigatus infection |

| 4 | 33 | 12 | M | Autosomal recessive (p67-phox deficient) | No | Pulmonary infection | Paecilomyces species | Positive culture of lung biopsy speci-men with several granulomata on histopathology | AmB for 4 wk; IFN-γ started | Alive |

| 5 | 23 | 10 | M | No | Disseminated infection (lung, scalp abscess, vertebral osteomye-litis) | Pseudallescheria boydii | Culture of open lung biopsy specimen and histopathology showing necrotiz-ing granulomata and rare branching fungal forms | Miconazole (30 mg/kg/day for 4 wk); subsequently, ketoconazole (7 mg/ kg/day for 3 mo); at recurrence, mico-nazole and debridement; IFN-γ (50 μg/m2 three times/wk); AmB (1.5 g in 3 mo); subsequently, Itra (7 mg/kg/day) plus IFN-γ | Alive | |

| 6 | 2 | 15 | M | No | Pulmonary infection | Acremonium strictum | Culture (SDA) of open lung biopsy specimen and histopathology with invasive fungal forms | AmB (3 g in 3.5 mo) followed by ketoconazole | Alive | |

| 7 | 13 | 18 | M | X linked (gp91-phox deficient) | No | Pneumonia | Sarcinosporon inkin | Culture and histopathology of lung | AmB (2 g in 8 wk), lobectomy, and leukocyte cell transfusions for 8 wk; subsequently, Itra | Alive |

| 8 | 12 | 21 | F | Autosomal recessive (p47-phox deficient) | No | Pulmonary and CNS infection | Exophiala dermatitidis | Culture and histopathology of thoracotomy | Resection of thoracic mass, AmB (2 g total) and 5FC (2 g/day) or ketoconazole (200 mg/day) plus leukocyte transfusions for 4 mo, followed by Flu (300 mg/day for 2 yr) | Alive |

| 9 | Present case | 15 | M | X linked | Yes (started 2 mo prior) | Pneumonia, pleuritis, pericarditis, osteo-myelitis | Chrysosporium zonatum | Culture and histopathology of bone biopsy and sputum culture | AmB (30 mg/kg total dose in 4 wk); Itra (8 mg/kg/day); at recurrence, AmB for 5 wk, LipAmB (20.3 g total dose) to completion of 1 y of therapy | Alive |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; AmB, amphotericin B; 5FC, flucytosine; Flu, fluconazole; Itra, itraconazole; LipAmB, liposomal amphotericin B; M, male; F, female; IFN-γ, gamma interferon; BHI, brain heart infusion.

Prophylaxis with gamma interferon was administered prior to fungal infection.

The diagnosis of fungal infection was suspected and is made without major difficulty in CGD patients. Diagnosis was based on histopathologic examination and culture of the biopsy specimen in all patients (Table 2). All patients were treated with conventional amphotericin B, with the total dose administered ranging between 25.5 mg/kg and 1.5 g/kg. In addition to amphotericin B, four patients received itraconazole, three were treated with miconazole and/or ketoconazole, and one received flucytosine and fluconazole. Additionally, three underwent various surgical procedures, three were started on gamma interferon in combination with antifungal agents, and 2 received leukocyte transfusions. Amphotericin B was administered for a duration ranging from 4 weeks to 1 year. Only one patient (the patient described here) was treated with liposomal amphotericin B due to the nephrotoxicity of conventional amphotericin B therapy.

C. zonatum is a poorly known, thermotolerant and keratinophilic species with a broad distribution. Initially discovered by horse hair bait from horse dung collected in Kuwait (1), the fungus has subsequently been recovered from India, southern Europe (Greece, Italy), the southern United States (Florida), and Japan (30). Mating tests have proven that C. zonatum is the anamorph (asexual or mitotic stage) of a heterothallic ascomycete, U. orissi (synonyms, Pseudoarachniotus orissi and Gymnoascus arxii) (family Onygenaceae) (30), and confirmed the identity of the case isolate (UAMH 8936) by production of ascoma-containing ascospores (Fig. 5) in pairings with compatible mating partners. Ascocarps of U. orissi are solitary, globose, and reddish brown and are composed of pale reddish brown ascospores surrounded by thin-walled hyaline racket hyphae and conidia. Ascospores are oblate (appearing like flattened disks) with truncate ends and appear smooth under a light microscope to slightly pitted (punctate) under a scanning electron microscope (Fig. 6). The anamorph C. zonatum (synonym, C. gourii) differs from other members of the genus Chrysosporium by its faster growth at 37°C than at 25°C (Fig. 3), by colonies which darken to buff, and by clavate, broadly truncate aleurioconidia typically borne on short, curved stalks (Fig. 4). Chrysosporium queenslandicum, another thermotolerant and keratinophilic species, is similar, but colonies do not darken, and intercalary arthroconidia are common. Because of similarities between their anamorphs and teleomorphs (sexual or meiotic stages), the teleomorph of C. queenslandicum has also been placed in the genus Uncinocarpus as Uncinocarpus queenslandicus (synonyms, Apinisia queenslandica and Brunneospora reticulata) (30).

The genus Uncinocarpus was described in 1976 for the heterothallic species Uncinocarpus reesii, which formed ascomata composed of a loose network of uncinate appendages. Its distinctive arthroconidial anamorph (Malbranchea stage) as well as its habitat in desert soils have suggested some affinity with the dimorphic pathogen Coccidioides immitis (28, 29). Support for this relationship has come from recent molecular phylogenetic analyses which found that U. reesii is a close relative of C. immitis (3, 21), from molecular evidence of recombination in C. immitis (4), and from the finding of helically coiled hyphae in some isolates of C. immitis (30). Although the meiotic stage of C. immitis remains elusive, the development of uncinate, helically coiled, or spiral appendages (setae) often occurs independently of the sexual stage, and such structures are recognized as markers of potential sexual reproduction in onygenalean and other fungi. Further support for a relationship between members of the genus Uncinocarpus and C. immitis comes from the fact that one of the species, U. orissi (C. zonatum), as reported here, has the potential to be a weak opportunistic pathogen.

C. zonatum, a catalase-positive filamentous fungus, is now added to the list of human pathogens as a new pathogen, having caused disseminated infection including pneumonia and osteomyelitis in a CGD patient. Despite the phagocytic defect of this patient, the outcome of his infection due to C. zonatum was favorable. Of note, the outcome of the infection was favorable in all CGD patients with non-Aspergillus fungal infections reviewed here except for one who recovered from Paecilomyces lilacinus infection but who finally succumbed to an A. fumigatus infection 4 months later. The infections due to non-Aspergillus fungi in CGD patients are curable if one diagnoses them promptly and treats them appropriately.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Fotis Kyrvassilis and Paraskevi Karayianni for excellent assistance in the care of the patient described here.

Part of this work was supported by European Commision Training and Mobility of Researchers grant FMRX-CT970145 Eurofung to E.R. L.S. thanks the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada for financial assistance and A. Flis and L. Abbott for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Musallam A, Tan C S. Chrysosporium zonatum, a new keratinophilic fungus. Persoonia. 1989;14:69–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boltansky H, Kwon-Chung K J, Macher A M, Gallin J I. Acremonium strictum-related pulmonary infection in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:653. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman B H, White T J, Taylor J W. Human pathogenic fungi and their close nonpathogenic relatives. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;6:89–96. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burt A, Carter D A, Koenig G L, White T J, Taylor J W. Molecular markers reveal cryptic sex in the human pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:770–773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen M S, Isturiz R E, Malech H L, Root R K, Wilfert C M, Gutman L, Buckley R H. Fungal infection in chronic granulomatous disease. The importance of the phagocyte in defense against fungi. Am J Med. 1981;71:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen-Abbo A, Edwards K M. Multifocal osteomyelitis caused by Paecilomyces variotii in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. Infection. 1995;23:55–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01710060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Echavarria E, Cano E L, Restrepo A. Disseminated adiaspiromycosis in a patient with AIDS. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:91–97. doi: 10.1080/02681219380000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinel-Ingroff A, Bartlett M, Bowden R, Chin N X, Cooper C, Fothergill A, McGinnis M R, Menezes P, Messer S A, Nelson P W, Odds F C, Pasarell L, Peter J, Pfaller M A, Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Shankland G S, Walsh T J, Weitzman I. Multicenter evaluation of proposed standardized procedure for antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:139–143. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.139-143.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamis A S, Gudnason T, Giebink G S, Ramsay N K C. Disseminated infection with Fusarium in recipients of bone marrow transplant. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1077–1088. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gueho E, Leclerc M C, de Hoog G S, Dupont B. Molecular taxonomy and epidemiology of Blastomyces and Histoplasma species. Mycoses. 1997;40:69–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kane J, Summerbell R C, Sigler L, Krajden S, Land G. Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. A clinical guide and laboratory manual of dermatophytes and other filamentous fungi from skin, hair and nails. Belmont, Calif: Star Publishing Co.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenney R T, Kwon-Chung K J, Waytes A T, Melnick D A, Pass H I, Merino M J, Gallin J I. Successful treatment of systemic Exophiala dermatitidis infection in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:235–242. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenney R T, Kwon-Chung K J, Witebsky F G, Melnick D A, Malech H L, Gallin J I. Invasive infection with Sarcinosporon inkin in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:344–350. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/94.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kornerup A, Wanscher J H. Methuen handbook of color. 3rd ed. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy F E, Larson J T, George E, Maisel R H. Invasive Chrysosporium infection of the nose and paranasal sinuses in an immunocompromised host. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:384–388. doi: 10.1177/019459989110400317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maran A G D, Kwong K, Milne L J R, Lamb D. Frontal sinusitis caused by Myriodontium keratinophilum. Br Med J. 1985;290:207. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6463.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgenstern D E, Dinauer M C, Doerschuk C M, Li L L, Gifford M A. Absence of respiratory burst in X-linked chronic granulomatous disease mice leads to abnormalities in both host defense and inflammatory response to Aspergillus fumigatus. J Exp Med. 1997;185:207–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison V A, Haake R J, Weisdorf D J. The spectrum of non-Candida fungal infections following bone marrow transplantation. Medicine (Baltimore) 1993;72:78–89. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odds F C, Van Gerven F, Espinel-Ingroff A, Bartlett M S, Ghannoum M A, Lancaster M V, Pfaller M A, Rex J H, Rinaldi M G, Walsh T J. Evaluation of possible correlations between antifungal susceptibilities of filamentous fungi in vitro and antifungal treatment outcomes in animal infection models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:282–288. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan S, Sigler L, Cole G T. Evidence for a phylogenetic connection between Coccidioides immitis and Uncinocarpus reesii (Onygenaceae) Microbiology. 1994;140:1481–1494. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-6-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson S W, Sigler L. Molecular genetic variation in Emmonsia crescens and E. parva, etiologic agents of adiaspiromycosis, and their phylogenetic relationship to Blastomyces dermatitidis (Ajellomyces dermatitidis) and other systemic fungal pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2918–2925. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2918-2925.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips P, Forbes J C, Speert D P. Disseminated infection with Pseudallescheria boydii in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease: response to gamma-interferon plus antifungal chemotherapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:536–539. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rihs J D, Padhye A A, Good C B. Brain abscess caused by Schizophyllum commune: an emerging basidiomycete pathogen. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1628–1632. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1628-1632.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigler L. Agents of adiaspiromycosis. In: Ajello L, Hay R, editors. Topley & Wilson’s microbiology and microbial infections. 9th ed. London, United Kingdom: Edward Arnold; 1998. pp. 571–583. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sigler L. Ajellomyces crescens sp. nov., taxonomy of Emmonsia spp., and relatedness with Blastomyces dermatitidis (teleomorph Ajellomyces dermatitidis) J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigler L. Chrysosporium and molds resembling dermatophytes. In: Kane J, et al., editors. Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. A clinical guide and laboratory manual of dermatophytes and other filamentous fungi from skin, hair and nails. Belmont, Calif: Star Publishing Co.; 1997. pp. 261–311. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigler L. Perspectives on Onygenales and their anamorphs by a traditional taxonomist. In: Reynolds D R, Taylor J W, editors. The fungal holomorph: a consideration of mitotic, meiotic and pleomorphic speciation. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1993. pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigler L, Carmichael J W. Taxonomy of Malbranchea and some other Hyphomycetes with arthroconidia. Mycotaxon. 1976;4:349–488. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sigler, L., A. L. Flis, and J. W. Carmichael. The genus Uncinocarpus (Onygenaceae) and its synonym Brunneospora: new concepts, combinations and connections to anamorphs in Chrysosporium, and further evidence of its relationship with Coccidioides immitis. Can. J. Bot., in press.

- 31.Sigler, L., and M. J. Kennedy. Aspergillus, Fusarium, and other opportunistic moniliaceous fungi. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. F. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed., in press. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 32.Sigler L, Roilides E, Bibashi E, Naitoh K, Hayashi S, Nishimura K, Kamei K, Kojima A, Matsubara S I, Nakahara Y, Flaris N, Katsifa H. Abstracts of the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1998. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Chrysosporium zonatum causing disseminated infection and pulmonary colonization, abstr. F-91; p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sillevis Smitt J H, Leusen J H, Stas H G, Teeuw A H, Weening R S. Chronic bullous disease of childhood and a Paecilomyces lung infection in chronic granulomatous disease. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:150–152. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silliman C C, Lawellin D W, Lohr J A, Rodgers B M, Donowitz L G. Paecilomyces lilacinus infection in a child with chronic granulomatous disease. J Infect. 1992;24:191–195. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(92)92980-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stillwell W T, Rubin B D, Axelrod J L. Chrysosporium, a new causative agent in osteomyelitis. A case report. Clin Orthop. 1984;184:190–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toshniwal R, Goodman S, Ally S A, Ray V, Bodino C, Kallick C A. Endocarditis due to Chrysosporium species: a disease of medical progress? J Infect Dis. 1986;153:638–640. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warwick A, Ferrieri P, Burke B, Blazar B R. Presumptive invasive Chrysosporium infection in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;8:319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williamson P R, Kwon-Chung K J, Gallin J I. Successful treatment of Paecilomyces variotii infection in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease and a review of Paecilomyces species infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:1023–1026. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.5.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]