Abstract

A single treatment approach will never be sufficient to address the diversity of individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). SUDs have historically defied definition through simple characterizations or models, and no single characterization has led to the development of broadly effective interventions. The range of dimensions of heterogeneity among individuals with SUDs, including severity, type of substance, and issues that frequently co-occur underscore that highly tailored approaches are needed. To approach personalized medicine for individuals with SUDs; two major developments are needed. First, given the diversity of individuals with SUDs, multivariate phenotyping approaches are needed to identify the particular features driving addictive processes in any individual. Second, a wider range of interventions that directly target core mechanisms of addiction and the problems that co-occur with them are needed. As clinicians cannot be expected to master the full range of interventions that may target these core processes, developing these so that they can be delivered easily, flexibly, and systematically via technology will facilitate our ability to truly tailor interventions to this highly complex and challenging population. One such technology-delivered intervention, computer-based training for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT4CBT), is used as an example to illustrate a vision for the future of highly-tailored interventions for individuals with SUDs.

Keywords: Substance use disorders, heterogeneity, phenotyping, treatment tailoring

What is addiction?

Use of alcohol, cocaine, opioid, and cannabis have been part of human existence for thousands of years and have cycled through periods of proscription and prescription. Our conceptualizations of the nature of the problems associated with excessive use of those substances has also evolved across time. Considering them as ‘moral failings’ led to spectacularly ineffective, often punitive, interventions (Babor, 1994). The ‘disease model’ that led to 12-Step approaches and mutual help groups was developed outside of traditional medical or scientific settings and discouraged systematic evaluation of outcomes. The existing specialty treatment system in the US for substance use disorders (SUDs) still consists largely of interventions borne of those movements (e.g., 30 day ‘rehabs’) which infrequently offer evidence-based therapies (McLellan, Carise, & Kleber, 2003).

The nature of SUDs defies any simple or unitary characterization; for example, denoting them as a ‘chronically relapsing disorder’ is contradicted by the many individuals who successfully stop use. Even neuroscience-informed conceptualizations such as the “brain disease” model fall short of fully accounting for the variety of issues associated with SUDs: “Brain disease” models emerged from neuroscience research confirming that extended use of drugs and alcohol can disrupt cognitive function, mood and reward sensitivity. This model has been useful in many respects, particularly in explaining why substance-related cognitive and physical accommodations make it so difficult for individuals with SUDs to stop using substances and that SUDs are not mere ‘failures of will”.

While useful in understanding how the brain is affected by chronic substance use, the brain disease model has not yet yielded effective new treatments for SUDs (e.g., Ekhtiari et al., 2019). Moreover, the established efficacy of interventions like contingency management (CM) for SUDs belies even the scientifically sophisticated brain disease model. Contingency management, grounded in operant conditioning theory, where behaviors that are reinforced are likely to be repeated, offer tangible rewards contingent on demonstrating targeted behaviors (submission of drug-free urine specimens) (Petry, 2000). Contingency management interventions have consistently been shown to very rapidly produce abstinence in a wide range of SUDS and are effective even for individuals with severe SUDs (Benishek et al., 2014). Thus, it follows if that SUDs were only or fundamentally a brain disease, akin to bipolar or schizophrenic disorders, we should not be able to so rapidly and dramatically reduce substance use in exchange for offering small incentives through CM. That said, contingency management interventions also have their limitations in addressing the complexity of SUDs: their efficacy drops off to some extent when the contingencies are terminated, and not all individuals with SUDs respond to them.

The profound heterogeneity of substance use disorders

A single explanatory model or treatment approach is unlikely to be found for SUDs because of their extraordinary heterogeneity along a range of dimensions: This includes the array of substances used, from the plant-based ‘classics’ of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiates to the exponentially-increasing range of pharmacologically-derived products including methamphetamine, ketamine, and fentanyl. Moreover, it is rare for individuals with SUDs to use only one substance; people use them in a dizzying array of combinations and routes of administration. Polysubstance use has long complicated research on development of effective medications, as most available pharmacotherapies for SUDs target only a single class of substances. Disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone (the latter also effective for opioid use disorder) are effective treatments for alcohol use disorder but have little effect on the substances typically used in conjunction with alcohol, such as cannabis, stimulants, and tobacco. The opioid agonists methadone and buprenorphine are highly effective in stabilizing people with opioid use disorder and reducing opioid-related morbidities and mortality but have no effect on the frequent use of stimulant, benzodiazepine, alcohol and cannabis use in these populations.

SUDs are also highly heterogeneous as to severity. Early conceptualizations emphasized the higher ends of severity and hence diagnostic systems reflected categorical classifications; an individual was an ‘addict’ or not, an ‘alcoholic’ or not. The diagnostic criteria for SUDs underwent a major recent change with DSM-5, which moved from a categorical to a continuous conceptualization. While retaining the bulk of criteria used in previous editions, the DSM-5 criteria for SUDs (Hasin et al., 2013) eliminated the dichotomies of ‘dependence’ versus the less severe ‘abuse’. Of DSM-5’s 11 criteria, an individual who meets 2–3 of them is classified as having a mild SUD, meeting 4–5 is classified as a ‘moderate’ and 6 or more as a ‘severe’ SUD.

Greater recognition of heterogeneity with respect to severity of SUDs has been a revolution in the field, as it propelled clinicians from primary focus on the most severe cases (the ‘bottomed out’ individual treated in long-term residential care followed by daily self-help meetings) to a broadening of the base of treatment (Institute of Medicine, 1990). Broadening the base meant (1) intervening earlier in the course of development of SUDs, preventing mild disorders from becoming severe ones, and (2) identifying and intervening with the larger and more diverse of individuals at low to moderate severity levels. This in turn led to large-scale efforts to screen individuals in a range of novel settings (e.g., primary care, emergency departments) to identify those with risky/harmful substance use and offer them brief interventions (typically single-session motivational interventions which provide personalized feedback and a range of options for change). This approach, called Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) has demonstrated clear efficacy for individuals with unhealthy alcohol use (Babor et al., 2007). Nevertheless, SBIRT proved ineffective for individuals with unhealthy drug use (Saitz, 2014); providing yet another example of how the heterogeneity of SUDs undermines any ‘one size fits all’ solution.

Another important facet of the heterogeneity of SUDs is the range of comorbid problems that co-occur with them. A favorite mentor summed this up as “for any given psychological construct, people with substance use disorders always have more of it”. An exemplar is psychiatric comorbidity: Epidemiological surveys consistently indicate high rates of all psychiatric disorders in individuals with SUDs, particularly depression and anxiety (Kessler et al., 1997). These observations generated popular theories such as the self-medication hypothesis, which proposed that individuals were using substances to address their psychiatric symptoms; therefore, appropriate treatment of their psychiatric disorder should lead to reductions in substance use. Again, SUDs defied the easy explanation; support for the self-medication hypothesis faded after demonstrations that (1) in many individuals, the onset of substance use precedes that of the psychiatric disorder, and (2) effective treatment of the psychiatric disorder (e.g., antidepressant medication for those with comorbid depression and SUD) often improves the psychiatric symptoms but effects on substance use are modest (Nunes & Levin, 2004).

Other examples of individuals with SUDs having elevated levels of virtually any given psychological construct abound: These include impaired cognitive function (especially memory, attention, and decision making), impulsivity and risk taking, reward sensitivity, delayed discounting of future rewards, stress, craving and attentional bias to drug cues, dysregulated affect, low distress tolerance, anhedonia, pain, insomnia and many others. Many of these have been shown to be present in individuals who are at higher risk of developing a SUD, but they also tend to increase in intensity after the onset of SUD, muddling attempts at understanding causal relationships. Regardless of their etiology, the presence of these problems typically worsens treatment outcomes. Thus, when present in treatment-seeking individuals with SUD, it follows that it would be helpful to address such problems in treatment. However, any given individual SUDs may have none of these co-occurring problems, one or two of them, or several of them. What would be a reasonable framework for identifying the most meaningful of these and providing appropriately tailored interventions?

Towards phenotypic assessment of SUDs

Recognizing the limitations of simple models of SUDs, the field is moving toward multidimensional, phenotypic assessment. Phenotyping is intended to better understand the heterogeneous nature of addiction, identify effective targets for novel interventions, improve treatment outcomes, and advance personalized medicine by identifying biomarkers of severity and treatment response (Litten et al., 2015). This approach has yielded significant insight into other psychiatric disorders (Tamminga et al., 2017) but has only recently been introduced to the study of addictions (Kwako, Momenan, Litten, Koob, & Goldman, 2016; Kwako et al., 2019).

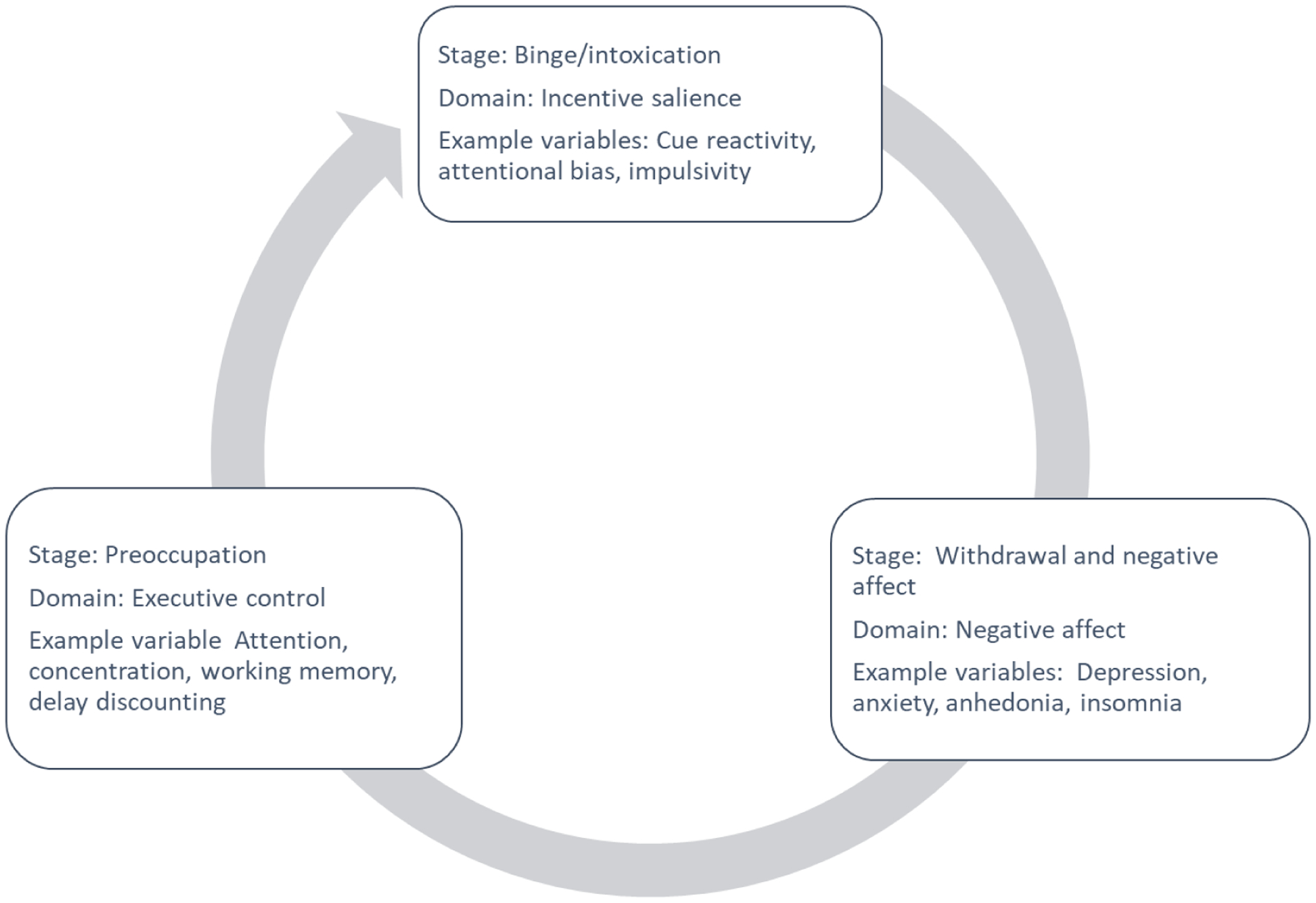

Kwako and colleagues (Kwako et al., 2016) proposed the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA), focused on three main domains (negative affect, executive function, and incentive salience) that roughly map onto Koob and Volkow’s conceptualization of the neurocircuitry of addictions, illustrated in Figure 1 (Koob & Volkow, 2016). These are thought to represent core features of addiction processes, wherein individuals move through cycles of binge/intoxication (characterized by incentive salience, including cue reactivity and attentional bias), followed by withdrawal and negative affect (encompassing depression and anxiety, anhedonia, insomnia), and finally to a stage dominated by preoccupation and craving (characterized by executive function deficits, with low response inhibition, working memory, and valuation of future events). The ANA is still in early stages of development, but initial validation work has been promising (Kwako et al., 2019; Votaw, Pearson, Stein, & Witkiewitz, 2020) and newer machine-learning approaches are likely to accelerate development of useful phenotyping strategies (Yip, Scheinost, Potenza, & Carroll, 2019).

Figure 1:

Koob and Volkow’s (2016) functional model of addiction, according to which individuals move through cycles of binging, withdrawal and negative affect, and preoccupation. For each stage, key domains for assessment are indicated.

Moving to highly tailored approaches via technology

Once a strategy for meaningful phenotypic characterization is identified, how would such a system be used to tailor treatments? One early attempt to match treatments to dimensions of heterogeneity among individuals with alcohol use disorder was Project MATCH, which evaluated the extent to which individuals with particular characteristics (e.g., gender, alcohol use severity, psychiatric severity, cognitive impairment, spirituality, motivation level) responded differently to three broad treatment types (Motivational Enhancement Therapy, Twelve-step Facilitation, or CBT). Despite careful formulation of seven distinct matching hypotheses, the data provided minimal support for any of them (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998). Investigators have since acknowledged that the matching hypotheses used in Project MATCH were too simplistic, given the heterogeneity of SUDs. Furthermore, most tailoring/matching projects, including Project MATCH, have not accounted for significant covariance among matching variables/predictors (Adamson, Sellman, & Frampton, 2009). A consensus is emerging that multivariate approaches are needed

What are the prospects for developing feasible, engaging treatments that can be tailored to the needs of highly heterogeneous groups of individuals with SUDs? This seems especially daunting in light of the difficulty of introducing empirically validated treatments in traditional treatment systems, much less tailoring treatments to diverse individual needs (McLellan et al., 2003). Given the lack of formal training and closely monitored supervision in evidence-based treatments provided by substance use treatment centers (Olmstead et al., 2012), it is unreasonable to expect clinicians to master the broad range of treatment approaches necessary to effectively tailor interventions. Despite development of multiple effective behavioral and pharmacologic treatments for SUDs, the modal treatment delivered in most community settings, regardless of individual treatment needs, continues to be unstructured group counseling (Hoffman & McCarty, 2013). Thus, after years of failed attempts to successfully move evidence-based treatments like CBT into this system, we began using technology as a strategy for making CBT more accessible and systematic so it could be ‘plugged in’ anywhere in the system (Carroll & Rounsaville, 2007, 2010)

Briefly, we developed computer-based training for CBT (CBT4CBT) as a set of 7 web-based modules, each teaching a targeted cognitive or behavioral skill (e.g., coping with craving, decision making skills, cognitive reappraisal) using narration, interactive exercises, quizzes, and engaging video examples of characters demonstrating effective implementation of the skill in challenging situations. Using the NIH Stage Model as our blueprint for development and evaluation (Onken, Carroll, Shoham, Cuthbert, & Riddle, 2013), we have completed 8 independent randomized trials demonstrating CBT4CBT’s efficacy, durability, and effects on skills acquisition in a range of settings and populations (Carroll & Kiluk, 2017).

While CBT4CBT and other technology-driven approaches have to some extent succeeded in making evidence-based treatments more systematic and accessible; they have far to go in tailoring them to addressing the heterogeneity of SUDs, which includes identifying the types of individuals that may benefit most from these interventions. That is, while we have developed versions of CBT4CBT for different broad samples (drug versus alcohol users, English- versus Spanish speakers), we offer the same ‘package’ of basic cognitive and behavioral skills to all individuals using the system. It is not unreasonable to provide many people seeking treatment for SUDs with some familiarity with understanding their patterns of use, coping with craving, recognizing and challenging their thoughts, but we are still far away from responding to the true level of heterogeneity in our samples, or demonstrating that this intervention actually addresses core features of addiction (DeVito, Kiluk, Nich, Mouratidis, & Carroll, 2018).

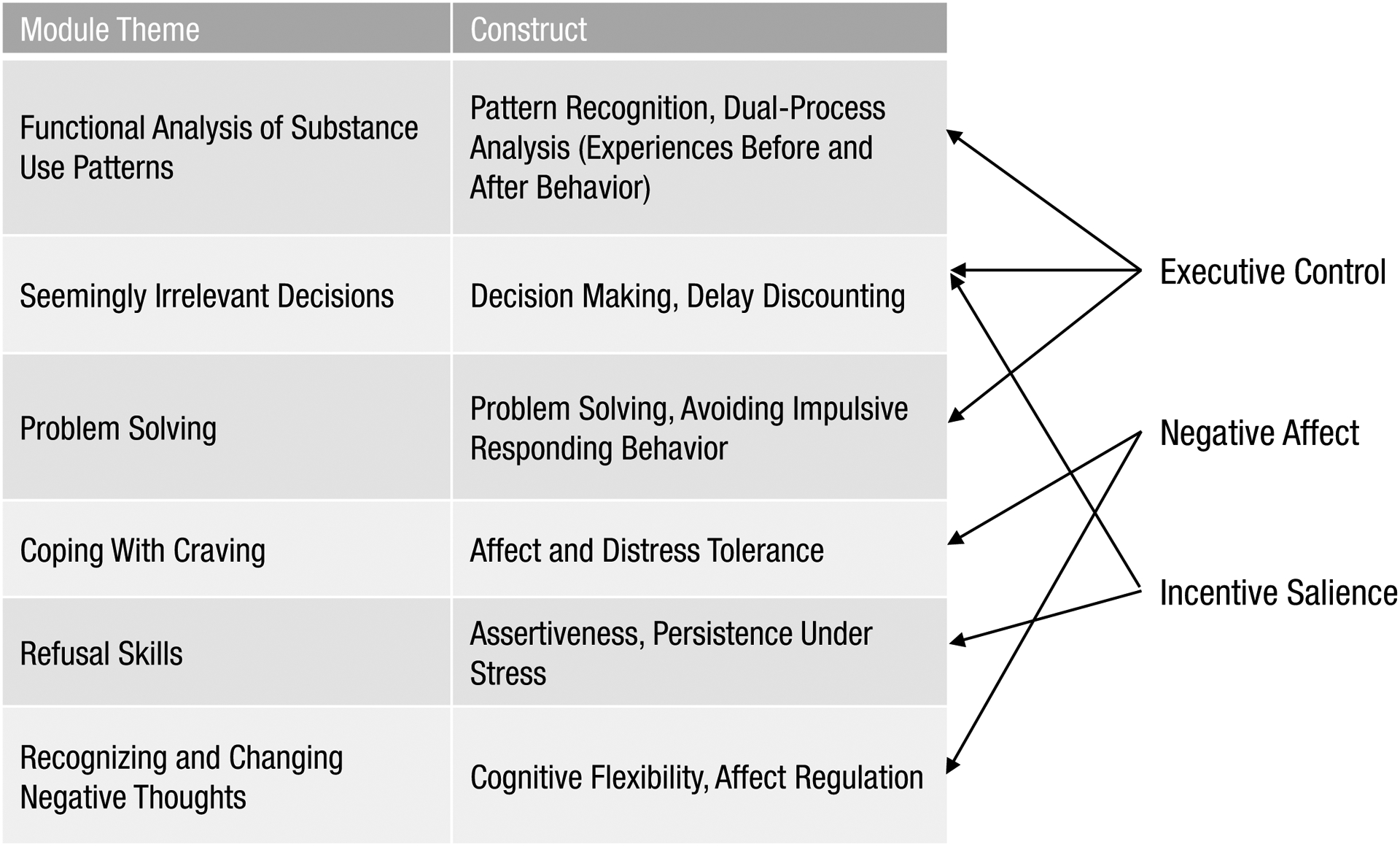

But it is a start; in the years ahead, we envision the development of modularized, technology-delivered approaches that could be highly tailored to the needs of individuals. Currently, we are attempting to map specific components of CBT4CBT onto the core functional components of SUDs as outlined by Koob and Volkow (Koob & Volkow, 2016) (Figure 2). We envision that phenotyping along the lines of the ANA could eventually be used to develop algorithms that define the issues primarily driving substance use in an individual to provide a tailored set of modules addressing them. For example, a woman with opioid use disorder who has high levels of negative affect, sleep disturbance, and chronic pain can be given a version of CBT4CBT-Buprenorphine that includes modules addressing mood and pleasant activities, sleep hygiene, and managing pain through exercise. A man with alcohol use disorder who has high impulsivity and poor decision-making skills can be provided with CBT4CBT-Alcohol with modules providing cognitive training addressing temporizing behavior and decision-making skills.

Figure 2:

Summary of the CBT4CBT modules and their proposed relationship to the three domains of addiction. Adapted from Carroll and Kiluk (2017), p. 853

Achieving this vision will require collaboration with other groups developing targeted, cognitive-science informed interventions for many of the problems that co-occur with SUDs. Examples include attentional bias modification to reduce response to specific drug cues (Heitmann, Bennik, van Hemel-Ruiter, & de Jong, 2018), cognitive remediation training to address aspects of executive functioning (Nixon & Lewis, 2019), and mindfulness strategies to address emotional dysregulation (Sancho et al., 2018). Broadly speaking, systematic reviews of these interventions indicate they tend to show efficacy in modifying the construct targeted but more modest, and inconsistent effects on substance use itself. Not surprisingly, these reviews also consistently note that the mixed nature of the findings may reflect the high level of heterogeneity across studies in sample characteristics. These highly targeted interventions are also usually not sufficient treatments delivered alone but could have promise when incorporated into broader technology-delivered approaches like CBT4CBT to deliver highly tailored ‘packages’ of modularized interventions.

Summary

There is tremendous heterogeneity among individuals with SUDs across a range of dimensions, including type of substance(s), severity, comorbid problems, and features of addiction processes. No single explanatory model or treatment approach is sufficient to address this heterogeneity. Multidimensional, phenotypic assessment has recently been introduced to better characterize the nature of addiction and understand heterogeneity along its core features. Although the identification of meaningful phenotypes is in early stages, it could eventually be used to inform a highly-tailored treatment approach that includes modularized technology-delivered interventions to target the areas primarily driving substance use for a given individual.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of NIH grants U10 DA15831, P50 DA09241, R01 DA 15969, R01 AA025605, R01 AA024122, R21 AA 021405 and R61 AT010619 in developing this work, my team of collaborators at Yale and particularly the participants in our clinical trials.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Carroll is a member of CBT4CBT LLC, which makes validated forms of CBT4CBT available to qualified clinical providers. An approved management plan with Yale University is in place.

References

- Adamson SJ, Sellman JD, & Frampton CM (2009). Patient predictors of alcohol treatment outcome: a systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(1), 75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF (1994). Avoiding the horrid and beastly sin of drunkenness: Does dissuasion make a difference? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 1127–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, McKee BG, Kassenbaum PA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, & Bray J (2007). Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Substance Abuse, 28, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kirby KC, Matejkowski J, Clements NT, Seymour BL, & Festinger DS (2014). Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: a meta-analysis. Addiction, 109(9), 1426–1436. doi: 10.1111/add.12589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2017). Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 847–861. doi: 10.1037/adb0000311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2007). A vision of the next generation of behavioral therapies research in the addictions. Addiction, 102(6), 850–862; 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01798.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2010). Computer-assisted therapy in psychiatry: be brave-it’s a new world. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(5), 426–432. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0146-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito EE, Kiluk BD, Nich C, Mouratidis M, & Carroll KM (2018). Drug Stroop: Mechanisms of response to computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence in a randomized clinical trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 183, 162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekhtiari H, Tavakoli H, Addolorato G, Baeken C, Bonci A, Campanella S, … Hanlon CA (2019). Transcranial electrical and magnetic stimulation (tES and TMS) for addiction medicine: A consensus paper on the present state of the science and the road ahead. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 118–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, … Grant BF (2013). DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(8), 834–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitmann J, Bennik EC, van Hemel-Ruiter ME, & de Jong PJ (2018). The effectiveness of attentional bias modification for substance use disorder symptoms in adults: a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 160. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0822-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KA, & McCarty D (2013). Improving the quality of addiction treatment. In Miller PM (Ed.), Interventions for Addiction: Comprehensive Addictive Behaviors and Disorders, (Vol. 3, pp. 579–588). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1990). Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, & Anthony JC (1997). Lifetime co-occurence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, & Volkow ND (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 760–773. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Momenan R, Litten RZ, Koob GF, & Goldman D (2016). Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment: A Neuroscience-Based Framework for Addictive Disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 80(3), 179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA, Diazgranados N, Koob GF, Volkow ND, … Goldman D (2019). Neurofunctional Domains Derived From Deep Behavioral Phenotyping in Alcohol Use Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18030357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Reilly M, Fertig JB, & Koob GF (2015). Heterogeneity of Alcohol Use Disorder: Understanding Mechanisms to Advance Personalized Treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(4), 579–584. doi: 10.1111/acer.12669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Carise D, & Kleber HD (2003). Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public’s demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25, 117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon SJ, & Lewis B (2019). Cognitive training as a component of treatment of alcohol use disorder: A review. Neuropsychology, 33(6), 822–841. doi: 10.1037/neu0000575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, & Levin FR (2004). Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 291(15), 1887–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead TA, Abraham AJ, Martino S, & Roman PM (2012). Counselor training in several evidence-based psychosocial addiction treatments in private US substance abuse treatment centers, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 120(1–3), 149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, & Riddle ME (2013). Re-envisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM (2000). A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58(1–2), 9–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. (1998). Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 22, 1300–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R (2014). Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use: little or no efficacy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5, 121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho M, De Gracia M, Rodriguez RC, Mallorqui-Bague N, Sanchez-Gonzalez J, Trujols J, … Menchon JM (2018). Mindfulness-Based Interventions for the Treatment of Substance and Behavioral Addictions: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 95. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Pearlson GD, Stan AD, Gibbons RD, Padmanabhan J, Keshavan M, & Clementz BA (2017). Strategies for Advancing Disease Definition Using Biomarkers and Genetics: The Bipolar and Schizophrenia Network for Intermediate Phenotypes. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 2(1), 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votaw VR, Pearson MR, Stein E, & Witkiewitz K (2020). The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment Negative Emotionality Domain Among Treatment-Seekers with Alcohol Use Disorder: Construct Validity and Measurement Invariance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(3), 679–688. doi: 10.1111/acer.14283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip SW, Scheinost D, Potenza MN, & Carroll KM (2019). Connectome-Based Prediction of Cocaine Abstinence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 176(2), 156–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Recommended reading

- Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2017). Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychololgy of Addictive Behavaviors, 31(8), 847–861. doi: 10.1037/adb0000311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • DESCRIPTION: This article reviews the evolution of cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders through the lens of the Stage Model of Behavioral Therapies Development, with an emphasis on incorporating cognitive science and neuroscience to to understand and advance effectiveness.

- Miller WR & Carroll KM (2006). Rethinking substance abuse: What the science shows and what we should do about it. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]; • DESCRIPTION: This book brings together leading experts to summarize the nature and causes of alcohol and drug use disorders, review the most effective treatments available, and provide principles for developing more effective treatments and services.

- Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, & Riddle ME (2013). Re-envisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • DESCRIPTION: This article presents a vision of clinical science using an updated stage model that incorporates basic science questions of mechanisms into each stage of intervention development.