Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) was recovered over a 2-month period from the dialysis fluid of a peritoneal dialysis (PD) patient who experienced recurrent episodes of peritonitis during therapeutic and prophylactic use of vancomycin. Characterization of five consecutive MRSE isolates by molecular and microbiological methods showed that they were representatives of a single strain, had reduced susceptibility to vancomycin, did not react with DNA probes specific for the enterococcal vanA or vanB gene, and showed characteristics reminiscent of the properties of a recently described vancomycin-resistant laboratory mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. Cultures of these MRSE isolates were heterogeneous: they contained—with a frequency of 10−4 to 10−5—bacteria for which vancomycin MICs were high (25 to 50 μg/ml) which could easily be selected to “take over” the cultures by using vancomycin selection in the laboratory. In contrast, the five consecutive MRSE isolates recovered from the PD patient during virtually continuous vancomycin therapy showed no indication for a similar enrichment of more resistant subpopulations, suggesting the existence of an “occult” infection site in the patient (presumably at the catheter exit site) which was not accessible to the antibiotic.

With the global spread of methicillin-resistant strains, glycopeptide antibiotics have become the mainstay of chemotherapy in both coagulase-negative staphylococci as well as Staphylococcus aureus infections worldwide. Loss of the antistaphylococcal efficacy of this family of drugs would pose a serious challenge to the treatment of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections. Such a situation may emerge by the transfer of enterococcal glycopeptide resistance genes to staphylococci, which often cocolonize wound infection sites with enterococci. In fact, transfer of the vancomycin resistance from Enterococcus faecalis to an S. aureus strain has already been demonstrated under simulated laboratory conditions (11). An additional concern relates to the increasingly frequent detection of coagulase-negative staphylococcal isolates with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptide antibiotics in clinical specimens associated with a variety of clinical diseases, particularly in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) (8, 13–15). Clinical failure of vancomycin therapy in an MRSA-infected patient has already been described in Japan (9). Soon after that, MRSA infections for which the vancomycin MICs showed a similar range (∼8 μg/ml) were also reported in the United States (2, 3).

In this communication, we describe the characterization of five consecutive isolates of a single methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) strain with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and teicoplanin, recovered from the dialysate of a peritoneal dialysis (PD) patient who experienced recurrent episodes of peritonitis during an extended period of therapeutic and/or prophylactic use of vancomycin. Ominously, the PD catheter site (as well as several other body sites) of the patient was also colonized by a vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis strain carrying the vanA gene. Nevertheless, the MRSE isolates did not react with the vanA DNA probe but appeared to carry a distinct glycopeptide resistance mechanism. The vancomycin MICs for the five MRSE isolates, as determined by broth dilution, were in the range of 2 to 16 μg/ml. However, population analysis showed that cultures also contained bacteria for which the vancomycin MICs were as high as 25 and 50 μg/ml at significant frequencies (10−4 to 10−5). Enrichment for these subpopulations occurred without difficulty under laboratory conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C with aeration. Organisms were identified to the species level by the API test system (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.). A preliminary determination of MICs of vancomycin was performed by a broth microdilution method, with TSB (Difco) and incubation of samples at 37°C for 24 and 48 h. The vancomycin (and methicillin)-susceptible S. aureus strain NCTC 8325 was always used as a susceptible control. Population analysis profiles (PAPs) were done for a more accurate and quantitative evaluation of antibiotic susceptibility (19). Overnight cultures of bacteria (≥109 CFU/ml) were plated at a series of dilutions on tryptic soy agar plates containing antibiotic-free medium or twofold dilutions of the test antibiotic within the drug concentration range of 0.75 μg up to 100 μg/ml in the cases of vancomycin and teicoplanin and up to 800 μg/ml in the case of methicillin. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h, and the number of bacterial colonies was counted. Plotting colony counts against drug concentrations provides a graphic display (PAP) of the composition of the bacterial culture in terms of the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the antibiotic susceptibility phenotype. Methicillin and glycopeptide MICs for the majority and for subpopulations of cells were determined by inspection of PAPs.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and separation of SmaI-restricted fragments in a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) apparatus (CHEF-DRII; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) were carried out as described previously (7). Autolysis was induced by suspending bacteria in buffer containing Triton X-100 (6). The titer of vancomycin in the growth medium was determined with a bioassay (16). Aggregation of cells and the ultrastructure of bacteria were determined by phase-contrast microscopy and electron microscopy with a procedure previously described (18).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Clinical history.

A 34-year-old female first developed renal failure of unknown etiology in 1985, and by 1988, she required hemodialysis. Two years later, because of inability to maintain a vascular access, she was placed on long-term PD. A year later, in 1991, she developed peritonitis, and over the next 6 years, she had recurrent episodes of peritonitis associated with fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. By 1994, the episodes became more frequent and severe, and S. epidermidis was first isolated from cloudy dialysate. She was placed on vancomycin (30 mg per liter) in each dialysis exchange for 10 to 60 days (5 exchanges per day) when symptoms or cloudy dialysate appeared. S. epidermidis was frequently recovered from her dialysate prior to each therapeutic trial. Because of the increasing frequency of her episodes and the need to continue peritoneal dialysis, she was placed on prophylactic vancomycin (30 mg per liter) in each dialysate exchange for 3 weeks of each month (5 exchanges per day) from January to June of 1997. Because of the identification of S. epidermidis with intermediate resistance to vancomycin (Table 1), the peritoneal dialysis catheter was removed on 16 June 1997, and she was placed on hemodialysis thrice weekly. Except for one intravenous dose associated with vascular access surgery, she did not receive vancomycin from 16 June until 10 September 1997. During this time period, she felt well and showed no clinical signs or symptoms of peritonitis, although she continued to have minimal drainage from the PD catheter site.

TABLE 1.

Properties of bacterial isolates recovered from a PD patient

| Specimen | Species | Isolation date (mo/day/yr) | Isolation site | Vancomycin

susceptibility MIC (μg/ml)a

|

PFGE pattern | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMD | PAP | |||||

| RR1 | E. faecium (vanB) | 8/8/93 | Breast | 32 | ND | Z |

| RR2b | E. faecalis (vanA) | 3/8/95 | PD exit site | 512 | ND | A0 |

| RR3b | E. faecalis (vanA) | 8/22/96 | PD exit site | >512 | ND | A1 |

| RR4b | S. epidermidis | 3/27/97 | PD fluid | 8 (16) | 6 | E |

| RR5b | S. epidermidis | 4/4/97 | PD fluid | 4 (8) | 3 | E |

| RR6b | S. epidermidis | 4/25/97 | PD fluid | 8 (16) | 6 | E |

| RR7b | S. epidermidis | 5/15/97 | PD fluid | 4 (8) | 3 | E |

| RR8b | S. epidermidis | 5/28/97 | PD fluid | 4 (8) | 3 | E |

| RR9c | E. faecalis (vanA) | 9/9/97 | PD exit site | >512 | ND | A1 |

| RR10c | E. faecalis (vanA) | 9/9/97 | Groin | >512 | ND | A1 |

| RR11c | E. faecalis (vanA) | 9/9/97 | Rectum | >512 | ND | A1 |

| RR12c | S. epidermidis | 9/9/97 | PD exit site | 2 (2) | 1.5 | F |

| RR13c | S. epidermidis | 9/9/97 | Nares | 4 (4) | 3 | F |

| RR14c | S. epidermidis | 9/9/97 | Groin | 4 (8) | 6 | G |

BMD, broth microdilution method, with readings after 24 and 48 h (48-h readings are in parentheses); ND, not determined.

Isolates collected during treatment with vancomycin.

Surveillance culture.

Properties of the bacterial isolates.

Table 1 summarizes the relevant properties of bacteria recovered from a variety of body sites and the PD fluid. Cultures of peritoneal dialysate collected between 27 March and 28 May yielded pure cultures of MRSE (isolates RR4 through RR8) with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and teicoplanin. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci, consisting of an E. faecium strain (isolate RR1) carrying the vanB gene and E. faecalis strains (RR2, RR3, and RR9 through RR11) carrying the vanA gene, were also detected at several body sites of the patient.

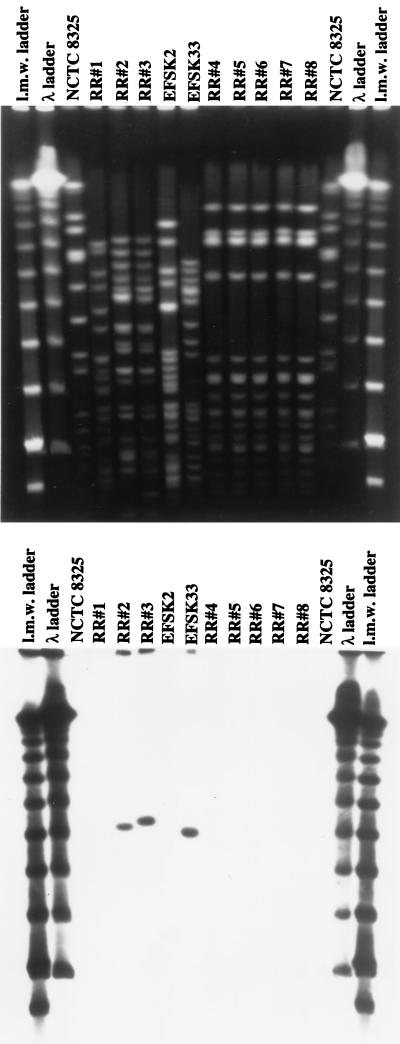

PFGE indicated that the five consecutive S. epidermidis isolates (RR4 through RR8) were identical, and tests with DNA probes specific for the enterococcal vanA (and vanB) probe showed no hybridization signal (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PFGE patterns of isolates recovered from the PD patient. Chromosomal DNA was prepared, SmaI restricted, and separated by PFGE (see Materials and Methods). The bottom panel shows results of hybridization with a probe for vanA. E. faecium strains EFSK2 (vanB) and EFSK33 (vanA) were used as controls. l.m.w., low molecular weight.

Heterogeneity of vancomycin resistance.

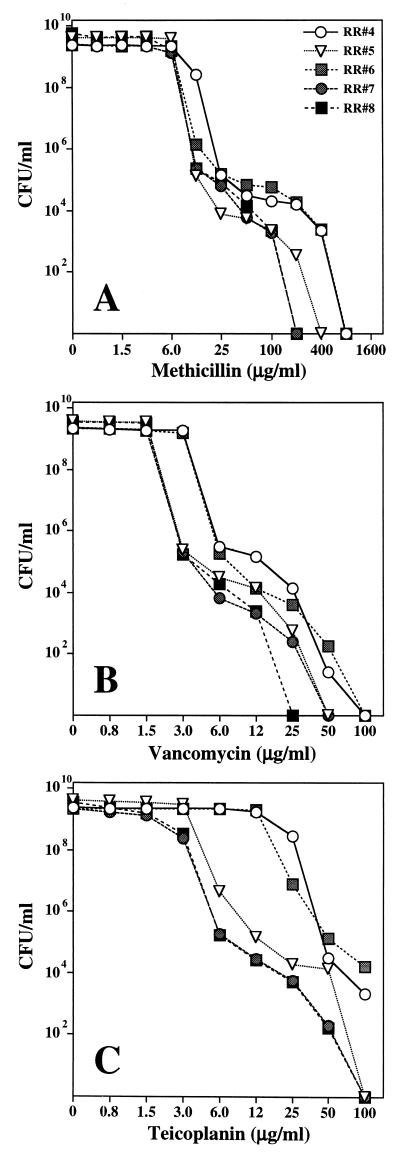

Evaluation of the broth dilution vancomycin MICs for the S. epidermidis strains after 24 and 48 h of incubation allowed detection of modest increases in MICs with extended incubation time. A more detailed characterization of overnight cultures of the five S. epidermidis isolates by population analysis showed that they were heterogeneous with respect to susceptibility to vancomycin, teicoplanin, and methicillin (Fig. 2). While the MIC of vancomycin for the majority of cells in these cultures was between 3 and 6 μg/ml, the cultures also contained bacteria for which the MICs were more substantially increased at low but significant frequencies. For instance, cultures of isolate RR4 contained subpopulations of cells capable of growing on plates that contained 12 μg of vancomycin per ml (MIC, 25 μg/ml) at a frequency of 10−4. Cells that formed colonies on 25 μg of vancomycin per ml (MIC, 50 μg/ml) were also present (frequency, 10−5).

FIG. 2.

Phenotypic expression of methicillin (A), vancomycin (B), and teicoplanin (C) resistance of consecutive isolates of S. epidermidis strains recovered from the PD patient.

Selection and stability of the highly vancomycin-resistant subpopulations.

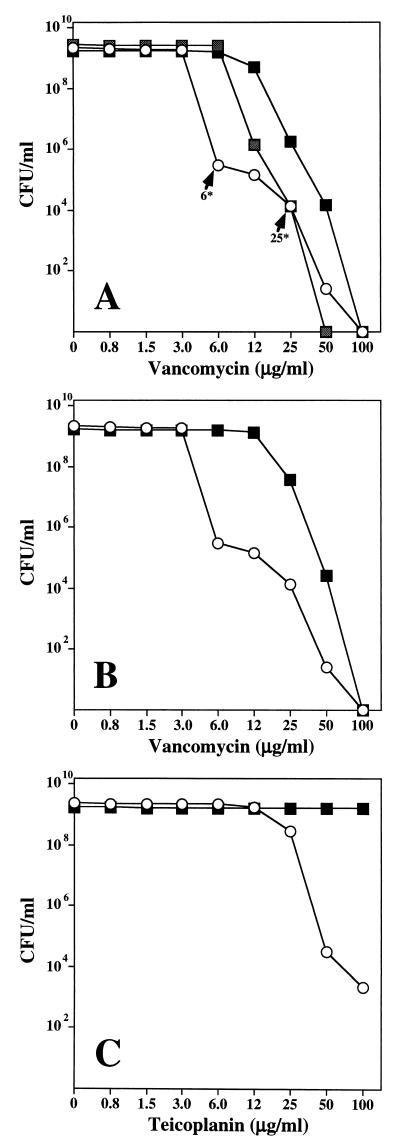

It was relatively easy to increase the proportion of these subpopulations under laboratory conditions. Colonies of isolate RR4 that were capable of growing on 6 μg of vancomycin per ml were dispersed in drug-free growth medium and used at very low cell concentrations (approximately 100 cells per ml) as inocula. Upon replating for population analysis, the majority of the culture showed an increase in the vancomycin MIC from 6 μg/ml for the original isolate, RR4, to 12 μg/ml. A separate colony of RR4 picked from the 25-μg/ml vancomycin plate yielded a culture in which the MIC of vancomycin shifted up to 25 μg/ml. Both of these cultures also became more homogeneous with respect to vancomycin susceptibility (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Enrichment of S. epidermidis cultures for subpopulations of bacteria for which the vancomycin MICs were elevated. Isolate RR4 was plated for population analysis on agar containing increasing concentrations of vancomycin (○). Bacterial cells capable of forming colonies on the agar containing 6 and 25 μg of vancomycin/ml (A, 6∗ and 25∗, respectively) were picked, diluted in drug-free TSB, grown overnight, and subsequently plated for population analysis. Symbols indicate cultures grown from a colony picked from the 6-μg/ml plate (░⃞) or from the 25-μg/ml plate (■). A culture of RR4 was diluted into TSB con- taining increasing concentrations of vancomycin (eventually 25 μg/ml), grown overnight, and then plated for population analysis on agar plates containing vancomycin (B) or teicoplanin (C). Open circles (○) represent population profiles of the original culture.

In an additional experiment, a small aliquot of strain RR4 culture was diluted into TSB containing 6 μg of vancomycin per ml. After overnight growth, this culture was reinoculated into TSB with 12 μg of vancomycin per ml and, subsequently, into medium containing 25 μg of vancomycin per ml. Figure 3B shows that this procedure also resulted in the selection of the originally minor, highly vancomycin-resistant subpopulation, which became the major component of the enriched culture, for which the vancomycin MIC was in the range of 25 to 50 μg/ml. The teicoplanin MIC for the same culture increased from the original 25 to 50 μg/ml to greater than 100 μg/ml (Fig. 3C). The elevated MIC for such highly vancomycin-resistant bacteria was retained during extensive passage (over 70 generations) in drug-free medium.

Enrichment of S. epidermidis cultures for bacteria for which the vancomycin MIC was increased during exposure to a bactericidal concentration of the antibiotic.

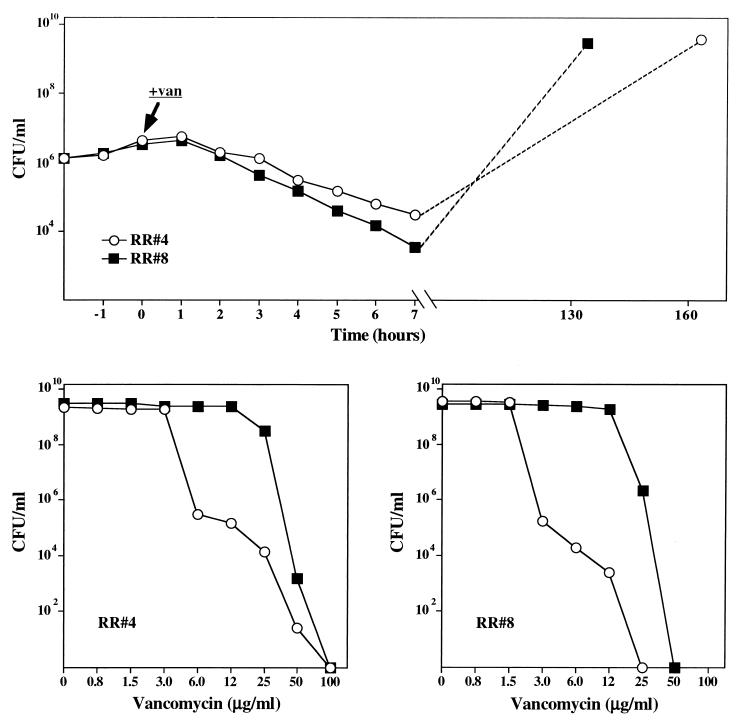

S. epidermidis isolates RR4 and RR8 were grown in TSB. At a cell concentration of about 5 × 106 CFU/ml, both cultures received 30 μg of vancomycin per ml, and viable titers were determined at hourly intervals (Fig. 4 [top]). After 7 h of incubation with the antibiotic, the viable titers of the cultures were reduced to about 5 × 104 and 5 × 103 CFU/ml in strains RR4 and RR8, respectively. The drop in viability was not accompanied by any change in optical density of the cultures. Upon further incubation (6 to 7 days), both cultures increased in viable titer (and optical density), to reach a stationary-phase concentration of about 5 × 109 CFU/ml. Population analysis done at the beginning and at the end of this experiment showed increases in the vancomycin MICs from 6 μg/ml to 50 μg/ml in RR4 and from 3 μg/ml to 25 μg/ml in RR8 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Selection for bacteria with increased vancomycin resistance during the bactericidal action of vancomycin. (Top panel) Effect of vancomycin (30 μg/ml added at the time indicated by arrow) on the viable titers of strains RR4 (○) and RR8 (■). (Bottom panels) Population analysis of the two strains before (○) and after (■) the massive population shift caused by vancomycin treatment.

S. epidermidis isolates (RR4 through RR8) grown in the presence of one-half of the respective MICs of vancomycin from small inocula in TSB containing the antibiotic showed several properties reminiscent of a highly vancomycin-resistant S. aureus laboratory mutant, VM (16), and several coagulase-negative staphylococcal isolates (12, 17) described recently. Thus, isolates RR4 through RR8 grown from small inocula in the presence of one-half the respective MICs of vancomycin for them showed the following. (i) There was aggregation easily visible to the eyes. (ii) Electron microscopy of RR4 through RR8 grown in the presence of vancomycin indicated formation of multicellular aggregates and the production of excess surface material similar in staining properties to that of cell wall (not shown). (iii) The results of biochemical tests (not shown) indicated that vancomycin completely inhibited autolysis of the cultures. (iv) Titration of the supernatants with a bioassay for free antibiotic showed that each of the cultures was capable of quantitatively removing vancomycin from the growth medium (data not shown).

These in vitro studies demonstrate unequivocally that the heterogeneous cultures of isolates RR4 through RR8 represent potential reservoirs of staphylococci for which the vancomycin MICs are above therapeutically achievable levels. The ease with which selection of these subpopulations occurred in the laboratory suggests that such subpopulations may also emerge in vivo, depending on the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin, the dosage regimen used, and the size of the pathogen population at the infection site(s). For these reasons, it was surprising to find that there was no significant upwards shift in the vancomycin MICs or PAPs among the consecutive surveillance cultures (RR4 through RR8) recovered from the patient during 2 months of extensive vancomycin prophylaxis.

The medical records allow one to estimate that between January and June of 1997, the patient received a total of close to 29 g of intraperitoneal vancomycin delivered in doses of 3 weeks of continuous administration per month. Despite this extensive exposure, the same S. epidermidis strain with a virtually identical hetero-resistance profile to vancomycin was recovered from each of the five dialysate samples, collected through a 2-month period of extensive vancomycin prophylaxis.

These observations allow two conclusions. (i) They clearly document failure of vancomycin prophylaxis to provide bacteriological cure of the PD infection. (ii) In contrast to the results of the in vitro studies, the in vivo use of vancomycin did not cause elevation of vancomycin resistance levels in the isolates, suggesting that the “core” S. epidermidis culture responsible for the repeated infections of the patient was not fully accessible to the antibiotic, most likely because of its localization at the catheter exit site. Relatively poor access of antibacterial agents to staphylococci adhering to artificial surfaces affecting reduced susceptibility to antibiotic killing has been demonstrated repeatedly (1, 4, 5, 10, 20). In fact, the episodes of recurrent S. epidermidis peritonitis of the patient described here only ceased upon subsequent removal of the dialysis catheter.

In view of the concern over the transfer of vancomycin resistance genes from enterococci to staphylococci under clinical conditions, it was an ominous sign that the PD catheter site (and several other body sites) of this patient was, at times, also colonized by vancomycin-resistant strains of E. faecalis (vanA) and E. faecium (vanB). It is conceivable that the overproduction of cell walls associated with the staphylococcal resistance mechanism may serve as a barrier to such interspecific gene transfers (16).

This report underscores the urgent need to delineate the mechanism(s) of the unique staphylococcal vancomycin resistance, to continue surveillance for the possible interspecific transfer of resistance genes to staphylococci, and to define the role of therapeutic and prophylactic dosing regimens in the selection of highly vancomycin-resistant staphylococcal strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Partial support was provided by the Bodman/Achelis Fund, the Lounsbery Foundation, and the Cary L. Guy Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown M R, Allison D G, Gilbert P. Resistance of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics: a growth-rate related effect? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22:777–780. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Staphylococcus aureuswith reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—United States, 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:765–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Staphylococcus aureuswith reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—United States, 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuard C, Vaudaux P E, Proctor R A, Lew D P. Decreased susceptibility to antibiotic killing of a stable small colony variant of Staphylococcus aureusin fluid phase and on fibronectin-coated surfaces. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:603–608. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuard C, Vaudaux P, Waldvogel F A, Lew D P. Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureusgrowing on fibronectin-coated surfaces to bactericidal antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:625–632. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.4.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Jonge B L M, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Suppression of autolysis and cell wall turnover in heterogeneous Tn551 mutants of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureusstrain. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1105–1110. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1105-1110.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Reassessment of the number of auxiliary genes essential for expression of high-level methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2590–2598. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.11.2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant A C, Lacey R W, Brownjohn A M, Turney J H. Teicoplanin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Lancet. 1986;ii:1166–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover F C. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureusclinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:135–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khardori N, Yassien M, Wilson K. Tolerance of Staphylococcus epidermidisgrown from indwelling vascular catheters to antimicrobial agents. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;15:148–151. doi: 10.1007/BF01569818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noble W C, Virani Z, Cree R G A. Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;93:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90528-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanyal D, Greenwood D. An electronmicroscope study of glycopeptide antibiotic-resistant strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:204–210. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-3-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanyal D, Johnson A P, George R C, Cookson B D, Williams A J. Peritonitis due to vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Lancet. 1991;337:54. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93375-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanyal D, Johnson A P, George R C, Edwards R, Greenwood D. In-vitro characteristics of glycopeptide resistant strains of Staphylococcus epidermidisisolated from patients on CAPD. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:267–278. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwalbe R S, Stapleton J T, Gilligan P H. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:927–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704093161507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sieradzki K, Tomasz A. Inhibition of cell wall turnover and autolysis by vancomycin in a highly vancomycin-resistant mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2557–2566. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2557-2566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieradzki K, Villari P, Tomasz A. Decreased susceptibilities to teicoplanin and vancomycin among coagulase-negative methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:100–107. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomasz A, Jamieson J D, Ottolenghi E. The fine structure of Diplococcus pneumoniae. J Cell Biol. 1964;22:453–467. doi: 10.1083/jcb.22.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomasz A, Nachman S, Leaf H. Stable classes of phenotypic expression in methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:124–129. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Graevenitz A, Amsterdam D. Microbiological aspects of peritonitis associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:36–48. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]