Abstract

The AML1 and ETS families of transcription factors play critical roles in hematopoiesis; AML1, and its non-DNA-binding heterodimer partner CBFβ, are essential for the development of definitive hematopoiesis in mice, whereas the absence of certain ETS proteins creates specific defects in lymphopoiesis or myelopoiesis. The promoter activities of numerous genes expressed in hematopoietic cells are regulated by AML1 proteins or ETS proteins. MEF (for myeloid ELF-1-like factor) is a recently cloned ETS family member that, like AML1B, can strongly transactivate several of these promoters, which led us to examine whether MEF functionally or physically interacts with AML1 proteins. In this study, we demonstrate direct interactions between MEF and AML1 proteins, including the AML1/ETO fusion protein, in t(8;21)-positive acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells. Using mutational analysis, we identified a novel ETS-interacting subdomain (EID) in the C-terminal portion of the Runt homology domain (RHD) in AML1 proteins and determined that the N-terminal region of MEF was responsible for its interaction with AML1. MEF and AML1B synergistically transactivated an interleukin 3 promoter reporter gene construct, yet the activating activity of MEF was abolished when MEF was coexpressed with AML1/ETO. The repression by AML1/ETO was independent of DNA binding but depended on its ability to interact with MEF, suggesting that AML1/ETO can repress genes not normally regulated by AML1 via protein-protein interactions. Interference with MEF function by AML1/ETO may lead to dysregulation of genes important for myeloid differentiation, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of t(8;21) AML.

Chromosomal translocations found in the acute leukemias frequently target the AML1 (CBFα)/CBFβ heterodimeric complex. Normal AML1 function is critical to the development of hematopoiesis, as the absence of functional AML1/CBFβ heterodimers (a condition generated by knocking out AML1 or CBFβ by homologous recombination in mice) completely prevents the development of definitive hematopoiesis in murine fetal liver (32, 36, 41, 48, 49). The AML1/ETO and CBFβ/MYH11 fusion proteins are generated by t(8;21) and inv(16) respectively, which are the most common chromosomal translocations in human acute myelogenous leukemia (22, 35). When AML1/ETO or CBFβ/MYH11 is overexpressed in developing murine hematopoietic cells (in “knockin” mice), the observed phenotype is nearly identical to knockout mice, suggesting that these fusion proteins dominantly inhibit AML1 function (6, 52).

The fusion partners of AML1, which also include TEL/AML1, AML1/MDS/EVI-1, and AML1/EVI-1 (14, 25, 27, 30, 40, 43), retain the sequence-specific DNA-binding motif of AML1, i.e., the Runt homology domain (RHD). The RHD is highly conserved across many species, including Drosophila melanogaster, sea urchin, and zebra fish (9, 33, 38, 43). The Drosophila runt gene, which is important for sex determination, segmentation, and neurogenesis (1, 43), has been shown to function as either an activator or a repressor of transcription (1). A Drosophila corepressor protein, called Groucho, has been shown to interact with the VWRPY pentapeptide motif at the C-terminal end of Runt, which is conserved among all of the wild-type members of the AML/Runt family of transcription factors; this motif is absent from the AML1/ETO, AML1/EVI-1, and AML1/MDS/EVI-1 fusion proteins (1).

The human AML1 proteins can regulate transcription of several genes expressed in hematopoietic cells, including T-cell receptors (TCRs) (13, 26), interleukin 3 (IL-3) (46), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (12), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) receptor (39), MPO (4), NE (34), and BCL-2 (20). However, the transcriptional activity of the AML1 proteins is highly context dependent. For example, AML1B, a 479-amino-acid isoform, also called AML1c, which can bind p300/CBP coactivator molecules (19), functions as an activator on many natural promoters (12, 26, 46). However, AML1B does not activate a reporter plasmid containing multiple copies of its consensus binding site. The 250-amino-acid isoform of AML1, which lacks the putative transcriptional activation domain, can activate an IL-3 promoter construct (46) but does not activate transcription of the GM-CSF promoter or the TCRα enhancer (12, 26). Although AML1/ETO has repressor function that dominantly represses the activating effects of AML1B in numerous instances (12, 26), AML1/ETO has also been shown to have transcriptional activating effects on the BCL-2 and M-CSF receptor promoters in U937 cells (20, 39). Thus, the activation or repression function of AML1-related proteins appears to have both promoter-specific and cell-type-specific components.

Protein-protein interactions likely dictate the effects of AML1 proteins on transcription. AML1 has been shown to interact with several proteins via its RHD, which is also required for heterodimerization with CBFβ (13, 24, 53), an interaction that enhances the DNA-binding activity of AML1. Recent studies suggest that AML1 can cooperate with ETS-1 and MYB; although AML1 has been shown to physically interact with ETS-1 (4, 13, 17), no evidence of direct protein-protein interaction between AML1 and MYB has been reported.

The ETS family of transcription factors plays a key role in the growth, survival, differentiation, and activation of hematopoietic cells (7, 50). This family of proteins is characterized by the presence of an 85-amino-acid, winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain. ETS proteins have been grouped into subfamilies based on sequence similarities and the position of the ETS domain (7). Targeted disruption of the PU.1 or ETS-1 gene has profound effects on myelopoiesis and lymphopoiesis, respectively (45). And like AML1, ETS proteins are frequently targeted by chromosomal translocations in human cancer (generating fusion proteins such as TEL-AML1, TEL-ABL, TEL-PDGFβR, EWS-FLI-1, FLI-EWS, EWS-ERG, ERG-EWS, EWS-ETV1, and ETV1-EWS [10, 14, 15, 18, 37, 42]).

The E74/ELF subfamily of ETS proteins includes the Drosophila E74 protein and the mammalian ELF-1, NERF, and MEF proteins. MEF (for myeloid ELF-1-like factor) was isolated from a human megakaryocytic leukemia cell line (29). MEF is expressed in many lymphoid and myeloid cell lines (29) and has potent transcriptional activating effects on genes expressed in both lymphoid and myeloid cells (12, 29, 46). ETS proteins commonly function as part of an integrated regulatory complex. For example, although ETS-1 can activate the TCRα enhancer, the appropriate assembly of a functional TCRα enhancer complex involves not only ETS-1 but also AML1, LEF-1, and CREB/ATF2 (5). Interactions between AML1 and ETS-1 are likely important in lymphoid cells, since ETS-1 is expressed predominantly in lymphoid cells in adults and is essential for maintaining the normal pool of resting T- and B-lineage cells (3, 31). We recently demonstrated the presence of MEF protein in Kasumi-1 cells, a myeloid leukemia cell line which contains a t(8;21) translocation and both AML1B and AML1/ETO. Since several genes are regulated by the ETS and AML1 families of proteins, we examined whether MEF could physically and functionally interact with AML1 proteins.

We readily detected an in vivo physical interaction between MEF and AML1 proteins in Kasumi-1 cells by coimmunoprecipitation and then used in vitro assays to identify a novel subdomain within the RHD of AML1 responsible for its interaction with ETS proteins. We also identified an N-terminal protein-protein interaction domain in MEF that is responsible for its binding to the Runt homology domain of AML1 proteins. Coexpression of MEF and AML1B synergistically activates promoter function, whereas expression of AML1/ETO dominantly represses the transactivating activity of MEF, even though the MEF and AML1 binding sites are not adjacent to each other. We determined that the DNA-binding function of AML1/ETO enhances but is not required for its repressor activity, defining the important role of protein-protein interactions in repression of transcription by AML1/ETO. Abnormal regulation of genes targeted by AML1/ETO likely contributes to the block in myeloid differentiation and/or the abnormal proliferation that characterizes acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids.

The full-length MEF cDNA coding region was cloned into the EcoRI site of the pGEX vector, in frame with the glutathione S-transferase (GST) coding cDNA (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, N.J.). To identify the region of MEF responsible for binding AML1, cDNA fragments of MEF encoding amino acid residues 1 to 206, 87 to 206, 87 to 300, 292 to 663, 336 to 663, and 204 to 292 (the ETS domain) were constructed by PCR and cloned in frame into the pGEX vector. The cDNA fragments encoding regions of the AML1B protein were generated by restriction enzyme digestion with XbaI-SmaI (encoding residues 28 to 86), SmaI-SmaI (encoding the Runt domain, residues 87 to 216), and SmaI-XbaI (encoding residues 217 to 479) or by PCR amplification (to generate portions of the Runt domain containing residues 88 to 119, 164 to 204, and 174 to 204) and subcloned into the pGEX vectors. The ETS-interacting domain (EID) deletion mutant, AML1/ETOΔEID, which lacks amino acid residues 137 to 171, was generated by replacing the wild-type AvrII-ApaI fragment with a mutant AvrII-ApaI fragment generated by PCR-based mutagenesis. The fidelity of all PCRs was verified by DNA sequencing. The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene constructs (−315 IL-3 pCAT, −315 mutAML1 IL-3 pCAT, and −315 mutETS IL-3 pCAT) have been described elsewhere (46). The pCMV5, pCMV5/AML1B, pCMV5/MEF, pCMV5/ETO, pCMV5/AML1/ETO, and pCMV5/AML1/ETOΔRHD plasmids have been described elsewhere (20, 29, 46).

Expression of GST fusion proteins in bacteria and GST pulldown assays.

GST fusion protein plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). After overnight culture, protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 to 4 h. Then, the bacterial pellets were lysed in 1 ml of PBS-T buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.3], 1% Triton X-100) with the aid of sonication. Supernatants were prepared by centrifugation at 4°C and stored at −80°C until use.

To study the interactions between MEF and AML1 proteins, equivalent amounts of GST fusion proteins (as judged by Coomassie blue staining of polyacrylamide gels) were incubated with 20 μl of 50% glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia) in a total volume of 1 ml of PBS-T for 45 minutes at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of PBS-T and then incubated with 2 μl of in vitro-transcribed and -translated 35S-labeled protein in 1 ml of NET-N buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1% Nonidet P-40 NP-40) for 2 to 4 h at 4°C. The beads were then washed with 1 ml of NET-N six times. The bound proteins were released from the beads by boiling at 95°C in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel loading buffer for 4 min. Proteins were analyzed by SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and autoradiography.

To generate in vitro-translated proteins for GST pulldown and immunoprecipitation assays, 35S-labeled AML1, AML1B, AML1ΔRHD (20), AML1/ETO, AML1/ETOΔEID, and MEF were synthesized in vitro by using the TNT coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega, Madison, Wis.), according to the procedures specified by the manufacturer.

Immunoprecipitations.

293T cells were transiently transfected with pCMV5-based expression plasmids encoding MEF, AML1/ETO, or ETO by a calcium phosphate precipitation method. After 24 h, the cells were harvested and lysed with NET-N buffer containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin [10 μg/ml], aprotinin [1 μg/ml], pepstatin A [1 μg/ml], and 1 mM dithiothreitol), followed by brief sonication. The cell lysates were precleared with 20 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) for 1 h at 4°C, followed by immunoprecipitation with rabbit polyclonal anti-MEF antiserum or anti-ETO antiserum (kindly provided by Paul Erikson) for another 2 h. The precipitated proteins were separated by SDS–12% PAGE and transferred to a Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Life Science) for 1 h at 4°C under 100 V. The membrane was then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MEF antiserum (1:1,000) or anti-ETO antiserum (1:500), according to a previously described procedure (23). Kasumi-1 cells (2 × 107) were treated with hydroxyurea (2 mM) overnight and used for in vivo immunoprecipitation and Western blotting experiments by the same procedures. Polyclonal anti-AML1 antiserum was produced by immunizing rabbits with a peptide corresponding to the N-terminal 17 amino acids of AML1; the antibody was affinity purified on a peptide-bound affinity column.

Transient transfection assays.

COS7 cells were electroporated with the empty pCMV5 expression plasmid or an expression plasmid that encodes AML1, AML1B, AML1/ETO, AML1ΔRHD, AML1/ETOΔEID, or MEF and a reporter gene plasmid containing 315 bp of IL-3 promoter sequences upstream of the start site by a previously described technique (46). The wild-type −315 IL-3 pCAT plasmid and similar reporter gene plasmids that contain mutations in either the AML1 or the ETS binding site have also been previously described (46).

RESULTS

AML1/ETO interacts with MEF in vivo.

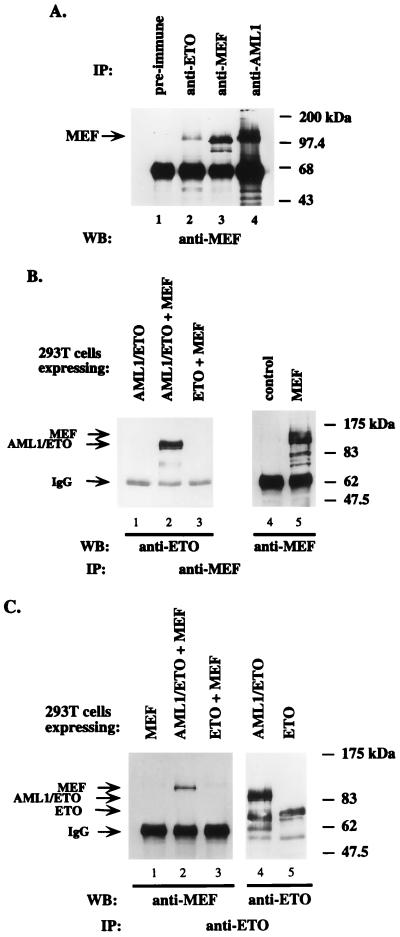

To determine whether MEF, which is expressed in most myeloid cell lines, interacts with AML1 and AML1/ETO, we used Kasumi-1 cells, a human AML cell line containing t(8;21), to perform immunoprecipitation experiments with rabbit polyclonal anti-AML1 or anti-ETO antiserum. The immunoprecipitates were subject to immunoblotting with a rabbit polyclonal anti-MEF antiserum. As shown in Fig. 1A, the 98-kDa MEF protein was coprecipitated by both the anti-AML1 and the anti-ETO antisera (lanes 4 and 2) but not by the preimmune serum (lane 1). The position and amount of MEF precipitated by the anti-MEF antibody is demonstrated in lane 3. Since both AML1/ETO and AML1B are expressed in Kasumi-1 cells (11), coprecipitation of MEF by the anti-AML1 antiserum (lane 4) presumably reflects its association with both AML1B and AML1/ETO in the cell, whereas the amount of MEF coprecipitated by the anti-ETO antiserum reflects only that bound to AML1/ETO (lane 2). Potential differences in the affinities between the two antisera may also account for some of this difference.

FIG. 1.

MEF interacts with AML1/ETO in vivo. (A) Kasumi-1 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal sera: lane 1, preimmune; lane 2, anti-ETO; lane 3, anti-MEF; lane 4, anti-AML1. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE and further subjected to immunoblotting (WB) with anti-MEF antiserum. (B) 293T cells were transfected with the indicated pCMV5 expression plasmids. After 24 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal antisera against MEF. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting with either anti-ETO antiserum (lanes 1, 2, and 3) or anti-MEF antiserum (lanes 4 and 5). (C) 293T cells were transfected with the indicated pCMV5 expression plasmids. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-ETO, followed by immunoblotting with either anti-MEF antiserum (lanes 1, 2, and 3) or anti-ETO antiserum (lanes 4 and 5).

To further characterize the in vivo interaction between the MEF and AML1 proteins, we transiently transfected human 293T cells with MEF, AML1/ETO, or ETO expression plasmids. After 24 h, the transfected cells were lysed and the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MEF antiserum, followed by immunoblotting with either an anti-MEF antiserum or an anti-ETO antiserum. As shown in Fig. 1B, AML1/ETO, but not ETO, was precipitated by anti-MEF antiserum from cells overexpressing both proteins (lanes 2 and 3) but not from cells expressing only AML1/ETO (lane 1). The position and amount of overexpressed MEF precipitated by the anti-MEF antiserum is shown in lane 5; no endogenous MEF was detected in 293T cells (lane 4).

In reciprocal experiments using the anti-ETO antiserum (Fig. 1C), MEF coprecipitated with AML1/ETO (lane 2) but not with ETO (lane 3). The anti-ETO antiserum itself did not precipitate MEF in the absence of AML1/ETO (lane 1). Lanes 4 and 5 show the amounts of overexpressed ETO and AML1/ETO precipitated by the anti-ETO antiserum. These results further define the in vivo interactions of MEF with AML1/ETO and demonstrate that MEF interacts with the AML1 portion of AML1/ETO rather than with the ETO portion.

MEF interacts directly with AML1 family members.

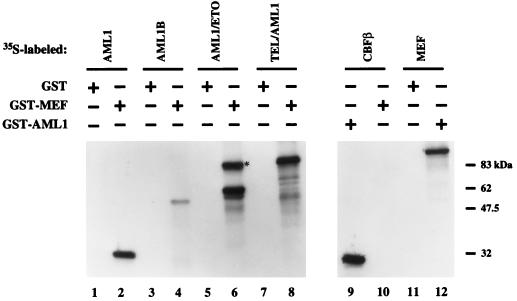

To determine whether MEF interacts directly with AML1 proteins, we performed in vitro association assays using 35S-labeled in vitro-translated AML1-related proteins and purified recombinant GST-MEF fusion protein (Fig. 2). 35S-labeled AML1, AML1B, AML1/ETO, and TEL/AML1 [the oncogenic product generated by the t(12;21) translocation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia] bound to GST-MEF (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) but not to GST alone (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). No direct association between GST-MEF and 35S-CBFβ was detected (lane 10). Reciprocal experiments performed with GST-AML1 demonstrated that GST-AML1 (but not GST alone) directly binds MEF, as well as 35S-labeled CBFβ (lanes 11, 12, and 9). To further rule out the possibility of nonspecific electrostatic interactions, 100 μg of ethidium bromide per ml was added to each reaction, but it did not disrupt their interactions (data not shown). Thus, MEF can directly bind to AML1, AML1B, AML1/ETO, and TEL/AML1 in vitro.

FIG. 2.

MEF interacts directly with AML1-related proteins in vitro. In vitro association assays were performed by incubating GST-MEF fusion protein immobilized by glutathione-Sepharose beads with 35S-labeled AML1 (lane 2), AML1B (lane 4), AML1/ETO (indicated by an asterisk in lane 6), TEL/AML1 (lane 8), or CBFβ (lane 10). In reciprocal experiments, GST-AML1 was incubated with 35S-labeled CBFβ or MEF (lanes 9 and 12). GST alone was incubated with 35S-labeled AML1 (lane 1), AML1B (lane 3), AML1/ETO (lane 5), TEL/AML1 (lane 7), and MEF (lane 11) as controls.

The C-terminal portion of the RHD, including the ATP binding site, is essential for the interaction of AML1 with MEF.

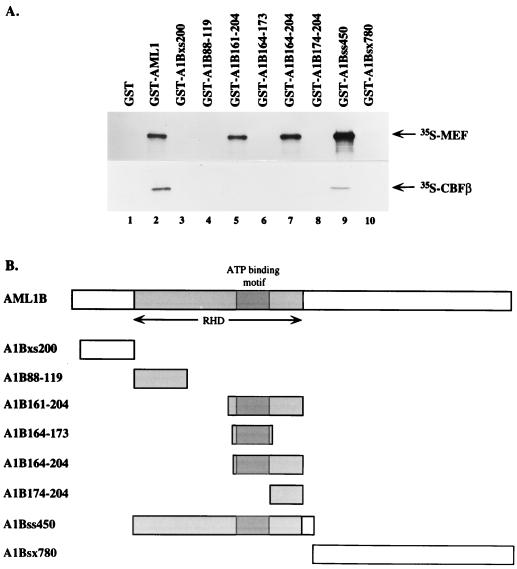

To characterize the region of AML1 that binds MEF, we prepared three distinct GST-AML1B proteins that contain either the RHD, the C-terminal region of AML1B, or an N-terminal region common to AML1, AML1B, and AML1/ETO. As shown in Fig. 3, the RHD-GST fusion protein (GST-A1Bss450) binds 35S-labeled MEF (lane 9), whereas neither GST, the N-terminal region (GST-A1Bxs200), nor the C-terminal region (GST-A1Bsx780) of AML1B interacted with 35S-MEF (lanes 1, 3, and 10). Given the ability of the RHD to bind MEF, we incubated GST-MEF with a 35S-labeled AML1B mutant protein that lacks the middle one-third of the RHD and can neither bind DNA nor CBFβ (46). Unexpectedly, this mutant protein bound GST-MEF similar to wild-type AML1B (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2), demonstrating that the middle one-third of the RHD is not required for binding to MEF. This suggests the presence of functional subdomains within the RHD.

FIG. 3.

The C-terminal portion of the RHD is the MEF-interacting domain. (A) Upper panel: in vitro 35S-labeled MEF was incubated with GST alone (lane 1), GST-AML1 (lane 2), or GST fusions with various deletion mutants of AML1B representing residues 29 to 86 (lane 3), 88 to 119 (lane 4), 161 to 204 (lane 5), 164 to 173 (lane 6), 164 to 204 (lane 7), 174 to 204 (lane 8), 87 to 216 (lane 9), and 217 to 479 (lane 10). Lower panel: 35S-labeled CBFβ was similarly incubated with the above GST or GST fusion proteins. (B) Schematic representation of AML1B deletion mutants. The shaded regions represent the RHD and the ATP-binding motif within it.

FIG. 4.

An intact RHD domain is not necessary for interaction of AML1B with MEF. (A) In vitro 35S-labeled AML1B (lane 1), AML1BΔRHD (lane 2), or CBFβ (lane 3) proteins were incubated with GST-MEF, and the mixtures were resolved by SDS-PAGE. (B) Schematic depiction of wild-type AML1B and the ΔRHD mutant proteins.

To further define the region within the RHD of AML1B responsible for its interaction with MEF, additional bacterially expressed GST-RHD deletion mutant proteins were incubated with 35S-labeled CBFβ or 35S-MEF. As shown in Fig. 3A, AML1B amino acid residues 88 to 119 did not bind MEF (lane 4), whereas residues 161 to 204 and 164 to 204 bound MEF similar to the wild-type RHD or AML1 proteins (compare lanes 5 and 7 with lanes 9 and 2). Deletion of 10 additional amino acids in an AML1B mutant (A1B174-204) abolished its binding to MEF (lane 8), demonstrating that the region containing the ATP-binding site is essential for the interaction of AML1B with MEF. However, a GST fusion peptide, A1B164-173, which contains the ATP-binding site, did not bind to MEF (lane 6), demonstrating that the region containing the ATP-binding site is necessary but not sufficient for binding to MEF. Consistent with previous studies (21), binding of AML1B to CBFβ is disrupted by any deletions within the RHD (lanes 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8). The integrity of the bacterially expressed GST fusion proteins was examined by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining. Approximately equal amounts of the fusion proteins were used for each reaction (data not shown). Thus, although the binding of CBFβ with AML1 requires an intact RHD, the binding of AML1 to MEF is independent of its binding to CBFβ and requires only the C-terminal one-third of the RHD.

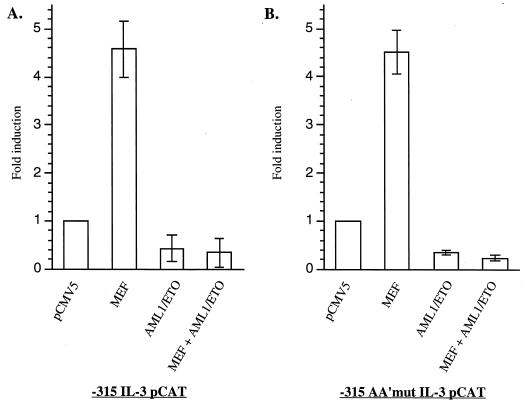

AML1 interacts with a region amino-terminal to the ETS domain in MEF.

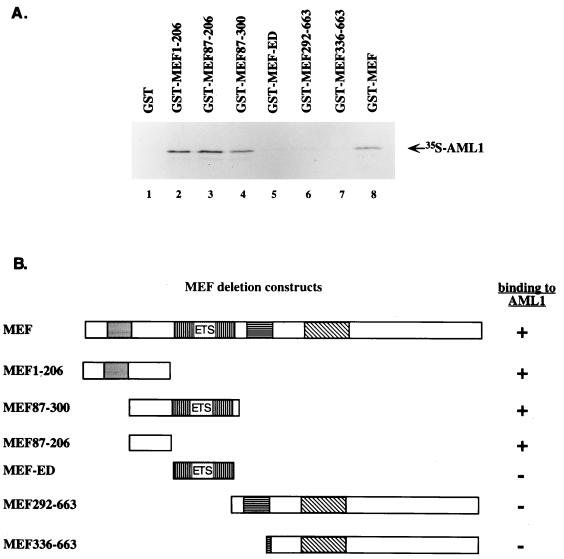

To map the region of MEF responsible for interaction with AML1, 35S-labeled AML1 was incubated with a series of GST-MEF deletion mutant proteins (Fig. 5). GST-MEF proteins that contain residues 1 to 206, 87 to 206, or 87 to 300 (lanes 2, 3, and 4) bind AML1 as well as full-length GST-MEF (lane 8), whereas GST alone (lane 1) or GST proteins containing only the amino acids in the ETS domain (lane 5) or the region C-terminal to the ETS domain (i.e., residues 292 to 663 or 336 to 663 [lane 6 and 7]) do not bind AML1. Therefore, the 120 amino acids N-terminal to the ETS domain in MEF, residues 87 to 206, are responsible for the binding of MEF to AML1 proteins.

FIG. 5.

A region of MEF, N-terminal to the ETS domain, is responsible for its interaction with AML-1 proteins. (A) GST-MEF mutant fusion protein were created and incubated with 35S-labeled AML1. The GST-MEF mutants contain amino acid residues 1 to 206 (lane 2), 87 to 206 (lane 3), and 87 to 300 (lane 4), the ETS domain (residues 206 to 292) (lane 5), and residues 292 to 663 (lane 6) and 336 to 663 (lane 7); lane 8 contains GST-MEF wild-type protein that was incubated with 35S-AML1. (B) Schematic representation of wild-type MEF and the deletion mutants. The shaded boxes represent four conserved regions of MEF, namely, the acidic region, the ETS domain, a serine-rich region, and a proline-rich region, moving from N to C terminus. The ability of these GST fusion proteins to bind AML1 is shown at the right.

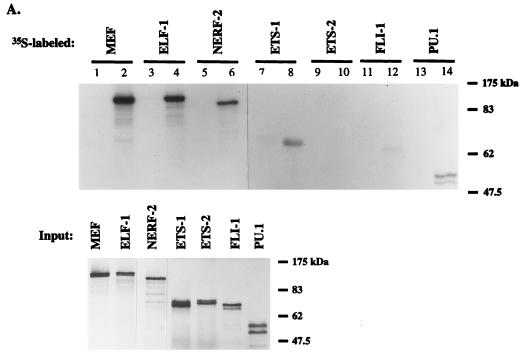

AML1 selectively interacts with other members of the ETS family.

The ETS domains of MEF and ELF-1 are quite similar, as is the region containing amino acid residues 87 to 206 of MEF, i.e., the AML1-interacting domain (Fig. 6B). To test if AML1 interacts with other ETS family proteins, GST-AML1 (and GST alone) was incubated with 35S-labeled MEF, ELF-1, NERF-2, ETS-1, ETS-2, FLI-1, and PU.1 (Fig. 6A). The integrity of the in vitro-translated ETS proteins was first checked by SDS-PAGE; intact proteins of the predicted size were seen in all cases (Fig. 6A, lower gel). GST-AML1 binds ELF-1, NERF-2, PU.1, and MEF (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 14), whereas the binding of AML1 to ETS-1 or FLI-1 was comparatively weak (lanes 8 and 12). Minimal, if any, binding of ETS-2 to AML1 was seen (lane 10), and no binding of ETS proteins to GST alone was seen (odd-numbered lanes). Thus, AML1 proteins apparently preferentially interact with the E74/ELF and perhaps the PU.1 subfamilies of ETS proteins.

FIG. 6.

AML1 differentially interacts with various ETS proteins. (A) 35S-labeled MEF (lane 2), ELF-1 (lane 4), NERF-2 (lane 6), ETS-1 (lane 8), ETS-2 (lane 10), FLI-1 (lane 12), or PU.1 (lane 14) was incubated with GST-AML1 or GST alone (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13). The integrity and amount of 35S-labeled proteins used for each reaction are shown in the lower panel. (B) Amino acid sequence homologies among the AML-1-interacting regions of MEF, ELF-1, and ETS-1 are depicted.

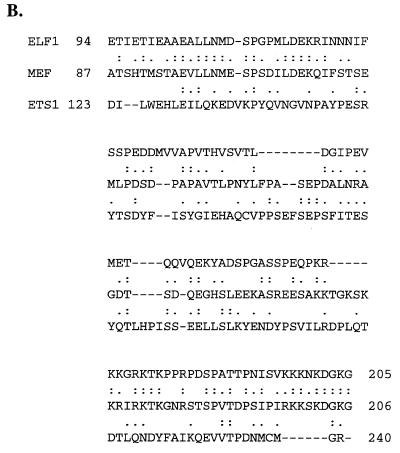

MEF and AML1B synergistically activate the IL-3 promoter.

The IL-3 promoter can be transactivated independently by AML1B (46) and by MEF (29). Transactivation by AML1B requires the AML1 binding site (located between −138 and −133), and transactivation by MEF depends largely on an MEF binding site located at −288 (29). To study the functional relevance of the physical interaction between MEF and AML1B, we cotransfected pCMV5/MEF and pCMV5/AML1B, either singularly or in combination, with an IL-3 promoter CAT construct into COS7 cells. As expected, both MEF and AML1B alone activate the IL-3 promoter, about 6.6-fold and 2.8-fold, respectively, in these experiments (Fig. 7). Coexpression of AML1B and MEF lead to a synergistic increase in CAT activity (∼18.3-fold), indicating that MEF can cooperate with AML1B to synergistically activate the IL-3 promoter.

FIG. 7.

MEF and AML1B synergistically activate the IL-3 promoter. COS7 cell lines were cotransfected with the indicated pCMV5 expression vectors and the −315 IL-3 pCAT reporter gene construct. Fold induction represents promoter activity in cells transfected with AML1B, MEF, or both plasmids relative to the activity in cells transfected with the pCMV5 plasmid alone. The data shown are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments using different preparations of plasmids and cells.

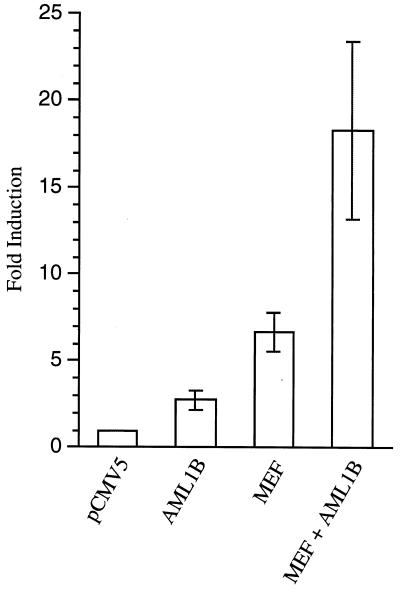

AML1/ETO dominantly represses the transactivating activity of MEF.

AML1/ETO can suppress AML1B function in vivo (6, 52) and in reporter gene assays (12, 26). The physical interaction between AML1/ETO and MEF led us to question whether AML1/ETO could similarly affect the function of MEF. Transient transfections were performed in COS7 cells with combinations of pCMV5, pCMV5/AML1/ETO, and pCMV5/MEF, with the IL-3 promoter CAT gene reporter plasmid. As shown in Fig. 8A, AML1/ETO suppresses basal IL-3 promoter function, and when MEF and AML1/ETO are coexpressed in COS7 cells, the transactivating activity of MEF is completely suppressed. This suggests that AML1/ETO can suppress the transcriptional activity of nearby transcription factors with which it interacts.

FIG. 8.

AML1/ETO dominantly represses the transcriptional activity of MEF on the IL-3 promoter. COS7 cells were cotransfected with the indicated pCMV5 expression vectors and the −315 IL-3 pCAT reporter gene construct (A) or the −315 AA′mut IL-3 pCAT reporter gene construct (B). Fold induction represents CAT activity in cells transfected with MEF, AML1/ETO, or both plasmids relative to the activity in cells transfected with pCMV5 alone. The results are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments using different preparations of plasmids and cells.

To determine whether the repression effect of AML1/ETO depends on its binding to the IL-3 promoter, we introduced a mutation in the AML1 binding site (−138 to −133) that abrogates binding by AML1 proteins (46). Nonetheless, AML1/ETO can still repress the trans-activating activity of MEF (Fig. 8B). To rule out the possibility that AML1/ETO might bind to a cryptic binding site in the IL-3 promoter, we tested the activity of AML1/ETOΔRHD, which lacks DNA-binding activity (20) but retains the ability to interact with MEF. When MEF and AML1/ETOΔRHD are coexpressed in COS cells, the transcriptional activity of MEF is still suppressed, although not as efficiently as by wild-type AML1/ETO (Fig. 9). These results suggest that AML1/ETO retains some of its repression activity in the absence of DNA binding, presumably through protein-protein interactions with the transcription factors (such as MEF) that bind to and regulate the same promoter.

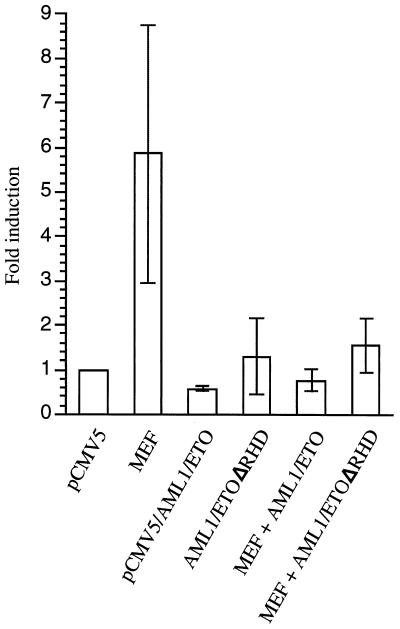

FIG. 9.

Repressive effects of AML1/ETO can occur in the absence of DNA binding. COS7 cells were cotransfected with the indicated pCMV5 expression vectors and the −315 IL-3p CAT reporter gene construct. Fold induction represents promoter activity in cells transfected with the pCMV5, MEF, AML1ETO, AML1/ETOΔRHD, MEF plus AML1/ETO, or MEF plus AML1/ETOΔRHD plasmids relative to the activity in cells transfected with pCMV5 alone. The results are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments using different preparations of plasmids and cells.

The ETS-interacting domain of AML1/ETO is required for repression of MEF activity.

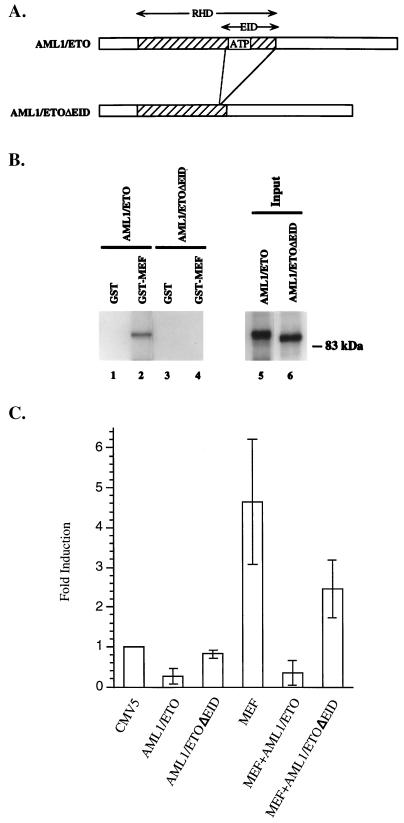

To examine whether the interaction between MEF and AML1/ETO is necessary for the repressive effect of AML1/ETO on MEF, we constructed an AML1/ETO mutant, AML1/ETOΔEID, which lacks the ETS-interacting domain (Fig. 10A). The 35S-labeled AML1/ETOΔEID mutant no longer binds to GST-MEF (Fig. 10B, lane 4), confirming the results, shown in Fig. 3, that the carboxy-terminal region of the RHD is the ETS-interacting domain. The AML1/ETOΔEID mutant also lost its ability to recognize the AML1 binding site in gel shift assays (data not shown). To examine whether this mutant can still repress the transcriptional activity of MEF, AML1/ETO or AML1/ETOΔEID was expressed in COS cells with or without coexpression of MEF. As shown in Fig. 10C, compared to AML1/ETO, AML1/ETOΔEID had little repressive effect on basal promoter activity and was defective in repression of MEF transcriptional activating activity. Thus, the ETS-interacting domain within the RHD of AML1/ETO is necessary for its dominant inhibitory effects on MEF function.

FIG. 10.

The EID is necessary for repression by AML1/ETO. (A) Schematic depiction of wild-type AML1/ETO and mutant ΔEID proteins. (B) In vitro 35S-labeled AML1/ETO (lanes 1 and 2) or AML1/ETOΔEID (lanes 3 and 4) protein was incubated with GST-MEF (lanes 2 and 4) or GST alone (lanes 1 and 3). The mixtures were washed and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The integrity and amount of in vitro-translated proteins is shown in lanes 5 and 6. (C) COS7 cells were cotransfected with the indicated pCMV5 expression vectors and the −315 IL-3 pCAT reporter gene construct. Fold induction represents promoter activity in cells transfected with the AML1ETO, AML1/ETOΔEID, MEF, MEF plus AML1/ETO, or MEF plus AML1/ETOΔEID plasmids relative to the promoter activity in cells transfected with pCMV5 alone. The results are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments using different preparations of plasmids and cells.

DISCUSSION

Although AML1/ETO has potent dominant repressor activity on AML1B, the biologic effects of AML1/ETO may also relate to its ability to bind and inhibit or activate the function of other cellular regulatory proteins. We have demonstrated a direct physical interaction between MEF and both AML1/ETO and AML1B in Kasumi-1 cells, an AML cell line that contains the t(8;21) translocation. This interaction was demonstrated without overexpressing AML1, AML1/ETO, or MEF, and the direct nature of the interaction was shown in in vitro assays.

The binding of AML1 to CBFβ requires an intact RHD (21, 24) whereas binding of MEF to AML1 requires only the C-terminal portion of the RHD. The region of the RHD that interacts with MEF contains a highly conserved ATP-binding site (GRSGRGKS) (8, 43). The role of this putative kinase-1a motif in the function of AML1 proteins is not clear. Mutation of a critical lysine residue in the ATP-binding motif of AML1 (to methionine) greatly reduced its DNA-binding capacity (21) but had no significant effect on its binding to MEF (data not shown). However, the 10-amino-acid region of AML1B that contains this ATP-binding site is necessary, but not sufficient, for its interaction with MEF. The RHD can thus be subdivided into one or more functional subdomains, with the C terminus of the RHD functioning as an EID. The physiologic importance of such subdomains is suggested by the recent identification of a truncated form of AML1, AML1ΔN, which contains an N-terminal truncation that eliminates nearly 50% of the RHD. This isoform of AML1 has lost its ability to bind DNA or CBFβ, but the region of the RHD that binds to MEF remains intact (the truncated protein can interact with ETS-1 [54]). Although binding of CBFβ to AML1 enhances its DNA-binding affinity, binding of MEF to AML1 does not noticeably enhance the ability of AML1 to bind DNA (data not shown). The interaction of MEF with AML1 can occur in the absence of DNA binding, because a mutant AML1B protein that cannot bind DNA (46) still interacts with MEF. Also, MEF physically interacts with AML1 despite the presence of a high concentration of ethidium bromide.

ETS proteins interact with several protein partners. ETS-1 interacts with the basic region of c-JUN through its ETS domain (2), and ELK-1, SAP-1, and NET interact with SRF through an identified protein interaction domain, the B domain (44). The 120-amino-acid region of MEF that interacts with AML1 does not overlap the ETS domain, nor is it homologous to previously defined protein-protein interacting domains. This region is reasonably conserved among ELF/E74 family members, having 69.6% homology and 37.4% identity with amino acid residues 94 to 205 in ELF-1 (Fig. 6B); this region may be the region in ELF-1 that interacts with AML1. The 118-amino-acid region of ETS-1 responsible for interacting with AML1 is similarly located outside the ETS domain (13); comparison of the AML1-interacting domains in MEF and ETS-1 revealed 45.8% homology and 13.4% identity in amino acid sequences (Fig. 6B). The amino acid differences between MEF and ELF-1, or ETS-1, may account for the differences in their binding affinities for AML1 (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, computer-facilitated protein structure analysis (with Lasergene software; DNASTAR Inc.) predicts that this region is exposed on the surface of the protein. Therefore, the AML1-interacting region of MEF and ETS-1 may represent a novel protein-protein interaction domain. The interactions between the AML1 and ETS families of transcription factors appear to be selective, and AML1 appears to preferentially interact with the E74/ELF subfamily of ETS proteins and with PU.1. There is an overlapping expression pattern of ETS proteins in hematopoietic cells, and although more than one ETS protein can be expressed simultaneously, the function of each protein is probably determined by its protein-protein interactions.

The functional consequence of the physical association of AML1B and MEF is synergistic transcriptional activation. Although the mechanism underlying this synergy is unknown, the AML1 binding site (−138 to −133) in the IL-3 promoter is necessary for synergism (data not shown). This is consistent with the view that AML1 proteins may function as anchor proteins, or as enhancer-organizers (21), which facilitate the transcriptional activities of other transcription factors by direct association. There are three ETS-binding sites in the IL-3 promoter (located at −288, −240, and −107), and we have previously shown that MEF can bind to the −288 site (29). Mutation of this site substantially decreased the activation of the IL-3 promoter by MEF; it did not abolish the synergism (data not shown), perhaps implying that MEF can bind to the other two ETS-binding sites. Synergism between AML1B and ETS-1, or MYB, has been shown by using the TCRα or -β enhancer (13, 44) and the MPO enhancer (4), which contain ETS or MYB binding sites within 10 bp of the AML1 binding site. None of the three ETS sites in the IL-3 promoter are adjacent to the AML1 site, implying that bending of the DNA between these sites may be required for synergism. Interactions between the two proteins may help bend the DNA, or involvement of other transcription regulators, such as the HMG proteins (5), could trigger DNA bending, in order to assemble a more efficient transcriptional complex.

In contrast to the synergistic effects of AML1B and MEF, the interaction between MEF and AML1/ETO leads to complete inhibition of MEF transactivating activity. Although the mechanism for this is unknown, a likely explanation is that AML1/ETO brings a corepressor molecule to the promoter which causes repression of MEF activity. Recent studies suggest that ETO can associate with the corepressor, N-CoR, and with mSIN3 and histone deacetylase activity (16, 47). The localized histone deacetylase activity could target the IL-3 promoter for repression. A dominant repressing effect of AML1/ETO on AML1B (12, 26) and C/EBPα (51) function has been observed. Our data support a novel mechanism for the leukemogenic function of AML1/ETO, as AML1/ETO can repress the activity of not only the transcription factors that bind to adjacent sites (51) but also those that bind to more distant sites (such as for MEF).

Direct protein-protein interactions between AML1/ETO and other transcription factors are important, as demonstrated by the ability of AML1/ETO to repress MEF in the absence of DNA binding. Deletion of the EID of AML1/ETO greatly impaired the transcriptional repression of AML1/ETO on MEF activity, indicating the critical role of the EID in mediating this function of AML1/ETO. This suggests that AML1 proteins such as AML1/ETO (or AML1ΔN) can target genes not normally regulated by AML1 proteins and lead to their dysregulation.

We have detected several distinct protein-protein interactions between AML1 proteins and ETS proteins, suggesting an important cooperative role for these proteins in regulating gene expression. Both families of proteins are essential to hematopoietic development. ETS-1 cooperates with AML1 proteins to transcriptionally activate the TCR enhancers, which are keys to T-cell development; ELF-1 might also play an important role in lymphopoiesis because of its ability to interact with AML1. The phenotype of PU.1 knockout mice suggests that the PU.1 protein is critical to myeloid development (45); thus, the interaction of PU.1 with AML1/ETO, and subsequent suppression of PU.1 target genes, may contribute to the phenotypic changes seen in t(8;21)-positive leukemias. MEF might also play a critical role in myeloid differentiation, as it also interacts directly with AML1 proteins. The function of MEF appears to be regulated during the G1-S phase of the cell cycle, potentially linking its function to the process of differentiation (28). Although the full biologic spectrum of activities of MEF remains to be determined (knockout studies in mice are in progress), its direct interaction with AML1 proteins suggests its importance to myeloid differentiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants DK43025 (S.D.N.), DK52208 (S.D.N.), and CA70388 (R.C.F.) and by the DeWitt Wallace Research Foundation (S.D.N. and R.C.F.), the Byrne Fund (S.D.N.), the Irma T. Hirshl Trust (S.D.N.), and the Norma and Rosita Winston Foundation (Y.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson B D, Fisher A L, Blechman K, Caudy M, Gergen J P. Groucho-dependent and -independent repression activities of Runt domain proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5581–5587. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassuk A G, Leiden J M. A direct physical association between ETS and AP-1 transcription factors in normal human T cells. Immunity. 1995;3:223–237. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bories J, Willerford D M, Grévin D, Davidson L, Camus A, Martin P, Stéhelin D, Alt F W. Increased T-cell apoptosis and terminal B-cell differentiation induced by inactivation of the Ets-1 proto-oncogene. Nature. 1995;377:635–638. doi: 10.1038/377635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britos-Bray M, Friedman A D. Core binding factor cannot synergistically activate the myeloperoxidase proximal enhancer in immature myeloid cells without c-Myb. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5127–5135. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruhn L, Munnerlyn A, Grosschedl R. ALY, a context-dependent coactivator of LEF-1 and AML-1, is required for TCRalpha enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1997;11:640–653. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castilla L H, Wijmenga C, Wang Q, Stacy T, Speck N A, Eckhaus M, Marin-Padilla M, Collins F S, Wynshaw-Boris A, Liu P P. Failure of embryonic hematopoiesis and lethal hemorrhages in mouse embryos heterozygous for a knocked-in leukemia gene, CBFβ-MYH11. Cell. 1996;87:687–696. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crepieux P, Coll J, Stehelin D. The Ets family of proteins: weak modulators of gene expression in quest for transcriptional partners. Crit Rev Oncog. 1994;5:615–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crute B E, Lewis A F, Wu Z, Bushweller J H, Speck N A. Biochemical and biophysical properties of the core-binding factor alpha2 (AML1) DNA-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26251–26260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daga A, Tighe J E, Calabi F. Leukaemia/Drosophila homology. Nature. 1992;356:484. doi: 10.1038/356484b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delattre O, Zucman J, Plougastel B, Desmaze C, Melot T, Peter M, Kovar H, Joubert I, de Jong P, Rouleau G, Aurias A, Thomas G. Gene fusion with an ETS DNA-binding domain caused by chromosome translocation in human tumours. Nature. 1992;359:162–165. doi: 10.1038/359162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank R C, Sun X, Berguido F J, Jakubowiak A, Nimer S D. The t(8;21) fusion protein, AML1/ETO, transforms NIH3T3 cells and activates AP-1. Oncogene. 1999;18:1701–1710. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank R, Zhang J, Uchida H, Meyers S, Hiebert S W, Nimer S D. The AML1/ETO fusion protein blocks transactivation of the GM-CSF promoter by AML1B. Oncogene. 1995;11:2667–2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giese K, Kingsley C, Kirshner J R, Grosschedl R. Assembly and function of a TCR alpha enhancer complex is dependent on LEF-1-induced DNA bending and multiple protein-protein interactions. Genes Dev. 1995;9:995–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub T, Barker G F, Bohlander S, Hiebert S W, Ward D C, Bray-Ward P, Morgan E, Raimondi S C, Rowley J D, Gilliland D G. Fusion of the TEL gene on 12p13 to the AML1 gene on 21q22 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4917–4921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golub T R, Barker G F, Lovett M, Gilliland D G. Fusion of PDGF receptor beta to a novel ets-like gene, tel, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with t(5;12) chromosomal translocation. Cell. 1994;77:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Munain C, Krangel M S. c-Myb and core-binding factor/PEBP2 display functional synergy but bind independently to adjacent sites in the T-cell receptor δ enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3090–3099. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon IS, Davis J N, Braun B S, Sublett J E, Roussel M F, Denny C T, Shapiro D N. A variant Ewing’s sarcoma translocation (7;22) fuses the EWS gene to the ETS gene ETV1. Oncogene. 1995;10:1229–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitabayashi I, Yokoyama A, Shimizu K, Ohki M. Interaction and functional cooperation of the leukemia-associated factors AML1 and p300 in myeloid cell differentiation. EMBO. 1998;17:2994–3004. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klampfer L, Zhang J, Zelenetz A O, Uchida H, Nimer S D. The AML1/ETO fusion protein activates transcription of BCL-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14059–14064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenny N, Meyers S, Hiebert S W. Functional domains of the t(8;21) fusion protein, AML-1/ETO. Oncogene. 1995;11:1761–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu P, Tarle S A, Hajra A, Claxton D F, Marlton P, Freedman M, Siciliano M J, Collins F S. Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia. Science. 1993;261:1041–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8351518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao S, Neale G A, Gorrha R M. T-cell proto-oncogene rhombotin-2 is a complex transcription regulator containing multiple activation and repression domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5594–5599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyers S, Downing J R, Hiebert S W. Identification of AML-1 and the (8;21) translocation protein (AML-1/ETO) as sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins: the runt homology domain is required for DNA binding and protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6336–6345. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers S, Hiebert S W. Indirect and direct disruption of transcriptional regulation in cancer: E2F and AML-1. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1995;5:365–383. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v5.i3-4.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers S, Lenny N, Hiebert S W. The t(8;21) fusion protein interferes with AML-1B-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1974–1982. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitani K, Ogawa S, Tanaka T, Miyoshi H, Kurokawa M, Mano H, Yazaki Y, Ohki M, Hirai H. Generation of the AML1-EVI-1 fusion gene in the t(3;21)(q26;q22) causes blastic crisis in chronic myelocytic leukemia. EMBO J. 1994;13:504–510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki, Y., S. Mao, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, H. Kiyokawa, and S. Nimer. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Miyazaki Y, Sun X, Uchida H, Zhang J, Nimer S. MEF, a novel transcription factor with an Elf-1 like DNA binding domain but distinct transcriptional activating properties. Oncogene. 1996;13:1721–1729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyoshi H, Kozu T, Shimizu K, Enomoto K, Maseki N, Kaneko Y, Kamada N, Ohki M. The t(8;21) translocation in acute myeloid leukemia results in production of an AML1-MTG8 fusion transcript. EMBO J. 1993;12:2715–2721. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthusamy N, Barton K, Leiden J M. Defective activation and survival of T cells lacking the Ets-1 transcription factor. Nature. 1995;377:639–642. doi: 10.1038/377639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niki M, Okada H, Takano H, Kuno J, Tani K, Hibino H, Asano S, Ito Y, Satake M, Noda T. Hematopoiesis in the fetal liver is impaired by targeted mutagenesis of a gene encoding a non-DNA binding subunit of the transcription factor polyomavirus enhancer binding protein 2/core binding factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5697–5702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nimer, S. D., T. Deblasio, and L. Zon. Unpublished data.

- 34.Nuchprayoon I, Meyers S, Scott L M, Suzow J, Hiebert S, Friedman A D. PEBP2/CBF, the murine homolog of the human myeloid AML1 and PEBP2β/CBFβ proto-oncoproteins, regulates the murine myeloperoxidase and neutrophil elastase genes in immature myeloid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5558–5568. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nucifora G, Rowley J D. AML1 and the 8;21 and 3;21 translocations in acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1995;86:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okuda T, van Deursen J, Hiebert S W, Grosveld G, Downing J R. AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell. 1996;84:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papadopoulos P, Ridge S A, Boucher C A, Stocking C, Wiedemann L M. The novel activation of ABL by fusion to an ets-related gene, TEL. Cancer Res. 1995;55:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pepling M E, Gergen J P. Conservation and function of the transcriptional regulatory protein Runt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9087–9091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhoades K L, Hetherington C J, Rowley J D, Hiebert S W, Nucifora G, Tenen D G, Zhang D E. Synergistic up-regulation of the myeloid-specific promoter for the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor by AML1 and the t(8;21) fusion protein may contribute to leukemogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11895–11900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romana S P, Mauchauffe M, Le Coniat M, Chumakow I, Le Paslier D, Berger R, Bernard O A. The t(12;21) of acute lymphoblastic leukemia results in a tel-AML1 gene fusion. Blood. 1995;85:3662–3670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sasaki K, Yagi R, Bronson T, Tominaga K, Matsunashi T, Deguchi K, Tani Y, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Absence of fetal liver hematopoiesis in mice deficient in transcriptional coactivator core binding factor b. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12359–12363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorensen P H, Lessnick S L, Lopez-Terrada D, Liu X F, Triche T J, Denny C T. A second Ewing’s sarcoma translocation, t(21;22), fuses the EWS gene to another ETS-family transcription factor, ERG. Nat Genet. 1994;6:146–151. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Speck N A, Stacy T. A new transcription factor family associated with human leukemias. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1995;5:337–364. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v5.i3-4.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun W, Graves B J, Speck N A. Transactivation of the moloney murine leukemia virus and T-cell receptor β-chain enhancers by cbf and ets requires intact binding sites for both proteins. J Virol. 1995;69:4941–4949. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4941-4949.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenen D G, Hromas R, Licht J D, Zhang D E. Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood. 1997;90:489–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uchida H, Zhang J, Nimer S D. AML1A and AML1B can transactivate the human IL-3 promoter. J Immunol. 1997;158:2251–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Hoshino T, Redner R L, Kajigaya S, Liu J M. ETO, fusion partner in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia, represses transcription by interaction with the human N-CoR/mSin3/HDAC1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10860–10865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Q, Stacy T, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe A H, Speck N A. Disruption of the cbfa2 gene causes necrosis and hemorrhaging in the central nervous system and blocks definitive hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3444–3449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Q, Stacy T, Miller J D, Lewis A F, Gu T L, Huang X, Bushweller J H, Bories J C, Alt F W, Ryan G, Liu P P, Wynshaw-Boris A, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Sharpe A H, Speck N A. The CBFbeta subunit is essential for CBFalpha2 (AML1) function in vivo. Cell. 1996;87:697–708. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wasylyk B, Hahn S L, Giovane A. The Ets family of transcription factors. Eur J Biochem. 1993;211:7–18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78757-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westendorf J J, Yamamoto C M, Lenny N, Downing J R, Selsted M E, Hiebert S W. The t(8;21) fusion product, AML-1–ETO, associates with C/EBP-alpha, inhibits C/EBP-α-dependent transcription, and blocks granulocytic differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:322–333. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yergeau D A, Hetherington C J, Wang Q, Zhang P, Sharpe A H, Binder M, Marin-Padilla M, Tenen D G, Speck N A, Zhang D E. Embryonic lethality and impairment of haematopoiesis in mice heterozygous for an AML1-ETO fusion gene. Nat Genet. 1997;15:303–306. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang D E, Hetherington C J, Meyers S, Rhoades K L, Larson C J, Chen H-M, Hiebert S W, Tenen D G. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and AML1 (CBFα2) synergistically activate the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1231–1240. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xhang Y-W, Bae S-C, Huang G, Fu Y-X, Lu J, Ahn M-Y, Kanno Y, Kanno T, Ito Y. A novel transcript encoding an N-terminally truncated AML1/PEBP2αB protein interferes with transactivation and blocks granulocytic differentiation of 32Dcl3 myeloid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4133–4145. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]