Abstract

Objective:

Emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP) in dried blood spots (DBS), a measure of short-term ART adherence, is associated with viral suppression in persons with HIV (PWH). However, its ability to predict future viremia remains unknown.

Design:

Prospective, observational cohort (up to 3 visits in 48 weeks).

Methods:

PWH receiving TDF/FTC-based ART had DBS and HIV viral load (VL) obtained at routine clinical visits. FTC-TP in DBS was dichotomized into quantifiable vs. below the limit of quantification (BLQ). The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of future viremia (≥20 copies/mL at next study visit) was estimated according to FTC-TP at the current visit. To assess for possible interactions, additional models adjusted for tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) in DBS and 3-day self-reported adherence.

Results:

Data from 433 PWH (677 paired DBS/HIV VL samples) were analyzed. The aOR (95% CI) for future viremia for BLQ vs. quantifiable FTC-TP was 3.4 (1.8, 6.5; p=0.0002). This diminished after adjusting for TFV-DP (aOR 1.9 [0.9, 4.1]; p=0.090). Among PWH reporting 100% 3-day adherence, the odds of future viremia were 6.0 times higher ([1.8, 20.3]; p=0.001) when FTC-TP was BLQ vs. quantifiable. Among participants (n=75) reporting <100% adherence, BLQ FTC-TP in DBS was not predictive of future viremia (aOR 1.3 [0.4, 4.6]; p=0.96).

Conclusions:

Non-quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS predicts future viremia and is particularly informative in PWH reporting perfect adherence. As point-of-care adherence measures become available, mismatches between objective and subjective measures, such as FTC-TP in DBS and self-report, could help clinicians identify individuals at an increased risk of future viremia.

Keywords: adherence, dried blood spots, emtricitabine triphosphate, antiretroviral therapy, pharmacokinetics, predictive value

Summary:

This study established that emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP) in dried blood spots, a measure of short-term adherence, is predictive of future viremia, in particular in persons living with HIV who report 100% adherence in the preceding 3 days.

Introduction

With the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to prevent disease progression in persons with HIV (PWH) and transmission to persons without HIV, there remains a concomitant need to maintain high and durable adherence to maximize treatment efficacy. This requires a clear interpretation of the most informative methods to quantify adherence. Unfortunately, this remains challenging, as traditional adherence measures (e.g., self-report, pill counts, electronic monitors and pharmacologic measures) have considerable shortcomings that limit their routine use in clinical practice[1]. In addition, relying on an undetectable HIV viral load (VL) is not truly informative of high adherence given the high potency of modern ART regimens[2-4]. Recently, new pharmacologic measures of cumulative (i.e., long-term) adherence, including drug concentrations in hair and dried blood spots (DBS), have been found to be strongly associated with viral suppression and to be predictive of future viremia[5-7]. However, less emphasis has been placed on the evaluation of short-term measures.

Emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP), the phosphorylated anabolite of FTC, can be quantified both in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and red blood cells, which are abundant in DBS[8]. In DBS, FTC-TP has a 35-hour half-life, which allows for its use as a measure of recent dosing to FTC both in PWH on ART and persons at high-risk for HIV on pre-exposure prophylaxis[8]. In comparison to tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) in DBS, which is usually categorized based on the concentrations that correspond to an average number of doses per week over the preceding ~6-8 weeks, FTC-TP in DBS is categorized as quantifiable vs. below the limit of quantification (BLQ) to reflect dosing within the preceding 48 hrs[8], similar to plasma and urine drug concentrations[9]. In PWH, quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS was recently found to be associated with concomitant viral suppression and was strongly predicted by 3-day self-reported adherence[10]. However, whether this (or other) short-term adherence measures can predict the development of future viremia has not been assessed, although this was firmly established for the cumulative adherence biomarker TFV-DP in DBS[7]. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to evaluate whether FTC-TP in DBS could predict future viral breakthrough in PWH receiving FTC-based ART.

Methods

Participants and Study Design

At the time of their routine clinical visits, PWH were prospectively recruited from the University of Colorado Hospital Infectious Diseases Group Practice, as previously described[5, 7]. Participants were required to be 18 years or older, to be taking a tenofovir-disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-including regimen (any type of regimen for any duration of time), and to be scheduled for a blood draw that included HIV VL as recommended by their primary HIV provider. If interested in the study, participants met with study personnel and, after written consent was obtained, 4-6 mL of whole blood for DBS were collected in an EDTA tube via the same venipuncture used during the participant’s routine laboratory draw. Additional DBS samples were obtained at the participant’s next routine clinic visit if blood for an HIV VL was drawn by the clinical provider, for a total of up to three visits in a 48-week period (with a minimum time of at least 14 days between visits to allow for one half-life of TFV-DP in DBS[11]). At each study visit, participants were asked about their 3-day, 30-day, and 3-month self-reported (SR) adherence to their current ART using a validated visual analog scale, as previously described[5, 12, 13]. Study enrollment began in June 2014, and follow-up for the last enrolled participant was concluded in July 2017. Throughout this period, no major changes in ART prescription were observed, and TDF remained the most prescribed nucleoside analog in the study population as most PWH had not been transitioned to tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)-based ART. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #13-2104) and was also registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02012621).

Quantification of Emtricitabine Triphosphate and Tenofovir Diphosphate in Dried Blood Spots

DBS for FTC-TP and TFV-DP were prepared by pipetting 25 mcl of whole blood for a total of five times onto a Whatman 903 Protein Saver card, as previously described by our group[5, 11, 14]. After spotting, the DBS cards were allowed to dry for at least 2 hours (up to overnight) and were stored frozen at −80°C until analysis[11]. For drug concentration assay, FTC-TP and TFV-DP were simultaneously quantified from a 3-mm punch using a validated liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry assay developed in our laboratory with a lower limit of quantification for TFV-DP of 25 fmol/sample [14, 15]. For FTC-TP in DBS, the lower limit of quantification was 0.1 pmol/sample[14, 15].

HIV Viral load analysis

HIV viral load analysis was performed as part of routine clinical care by the UCH clinical laboratory, which utilizes the Roche cobas® 6800 HIV test, with a linear range of 20 to 107 copies/mL[5]. The UCH clinical laboratory is certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment of 1988 (CLIA).

Statistical Analysis

While information was collected at up to three study visits, the maximum number of paired assessments per participant was two, with FTC-TP in DBS in visit 1 related to HIV VL in visit 2, and FTC-TP in DBS in visit 2 related to HIV VL in visit 3, as previously modeled for TFV-DP in DBS[7]. The outcome of interest, viremia, was defined as an HIV VL ≥20 copies/mL, while the predictor, FTC-TP in DBS, was dichotomized as quantifiable or BLQ[8]. Other predictors of interest included 3-day self-reported adherence, which was dichotomized into <100% vs. 100%, and TFV-DP in DBS. Based on previous studies in both HIV-negative persons and PWH, TFV-DP levels in DBS were assigned into one of three categories: a) low (BLQ to <800 fmol/punch), b) medium (800 to <1650 fmol/punch), and c) high (≥1650 fmol/punch)[7, 15]. Visits from participants who had not been on ART for at least 3 months were excluded in order to allow sufficient time for HIV VL to reach viral suppression and TFV-DP to reach steady-state[5, 7].

To account for repeated measures during the follow-up period, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were utilized to estimate the odds ratio (OR) for future viremia (≥20 copies/mL) comparing BLQ FTC-TP to quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS. In addition, an adjusted OR (aOR) was obtained after we included demographic and clinical covariates (selected a priori) that were anticipated to influence the pharmacology of TFV and TFV-DP[5, 16]. These included age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, estimated using MDRD equation), CD4+ T-cell count, hematocrit, and ART class[5, 7, 16]. Further analyses included separately adding TFV-DP in DBS or 3-day self-reported adherence into the FTC-TP models, as well as exploring any interaction effect between FTC-TP in DBS and the other measures of adherence. For primary predictors, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For pair-wise comparisons relating to any interaction term, the Tukey-Kramer adjustment was applied. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Incl, Cary, NC), R software version 3.6.3, and GraphPad Prism version 7.

Results

Study Population

As previously reported in this cohort, 451 participants with current DBS and subsequent HIV VL data were available for analysis[7]. Of these, 18 participants were not on an FTC-containing regimen and were excluded, leaving 433 participants to be included in the present analysis. The median age of the study cohort was 46 [IQR 37-52] years, and 16% were women. The majority self-identified as white (n=246, 57%), with approximately equal numbers of Black (n=83, 19%) and Hispanic (n=85, 20%) participants. Additional demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants at first evaluable visit according to emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP) in dried blood spots (DBS). All values are expressed as median (IQR) or n (%).

| FTC-TP in DBS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All Participants (n=433) |

BLQ* (n=41) |

Quantifiable (n=392) |

| Age | 46 (37, 52) | 43 (34, 50) | 46 (38, 53) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 364 (84%) | 33 (80%) | 331 (84%) |

| Female | 69 (16%) | 8 (20%) | 61 (16%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 83 (19%) | 9 (22%) | 74 (19%) |

| White | 246 (57%) | 19 (46%) | 227 (58%) |

| Hispanic | 85 (20%) | 12 (29%) | 73 (19%) |

| Other | 19 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 18 (5%) |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) | |||

| <18.5 | 18 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 17 (4%) |

| 18.5-25 | 183 (42%) | 19 (46%) | 164 (42%) |

| 25-30 | 146 (34%) | 14 (34%) | 132 (34%) |

| >30 | 86 (20%) | 7 (14%) | 79 (20%) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 87 (73, 101) | 98 (81, 112) | 86 (73, 100) |

| CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) | |||

| <200 | 47 (11%) | 9 (22%) | 38 (10%) |

| 200-350 | 62 (14%) | 6 (15%) | 56 (14%) |

| 350-500 | 64 (15%) | 8 (20%) | 56 (14%) |

| >500 | 260 (60%) | 18 (44%) | 242 (62%) |

| HIV viral load (copies/mL)** | 117 (36, 710) | 6620 (352, 35,600) | 67 (32, 189) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 45 (42, 47) | 44 (40, 46) | 45 (42, 47) |

| Type of ART | |||

| NNRTI-based | 118 (27%) | 3 (7%) | 115 (29%) |

| INSTI-based | 155 (36%) | 15 (37%) | 140 (36%) |

| b/PI-based | 106 (24%) | 14 (34%) | 92 (23%) |

| Multiclass | 54 (12%) | 9 (22%) | 45 (11%) |

| TFV-DP in DBS category (fmol/punch) | |||

| <800 | 55 (13%) | 26 (63%) | 29 (7%) |

| 800-1650 | 156 (36%) | 12 (29%) | 144 (37%) |

| ≥1650 | 222 (51%) | 3 (7%) | 219 (56%) |

| Self-reported adherence (%) | |||

| 3-day | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (10, 100) | 100 (100, 100) |

| 30-day | 100 (94,100) | 90 (50, 95) | 100 (95, 100) |

| 3-month | 98 (90,100) | 80 (50, 90) | 99 (90,100) |

FTC-TP: emtricitabine triphosphate; TFV-DP: tenofovir diphosphate; DBS: dried blood spots; ART: antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; INSTI: integrase strand-transfer inhibitor; b/PI: boosted protease inhibitor.

FTC-TP in DBS was considered BLQ if it was <0.1 pmol/sample.

HIV viral load for viremic participants (≥20 copies/mL).

From the 433 participants included in the analysis, 199 (46%) contributed 1 paired assessment and 234 (54%) contributed 2 paired assessments, for a total of n=667 paired assessments analyzed. The median (range) days between visits was 119 (14, 336) days. FTC-TP in DBS was BLQ in 56 (8.4%) of the assessments, and 49 (11%) participants had at least 1 FTC-TP BLQ assessment. Overall, 3-day self-reported adherence was high, with a median [IQR] of 100% [100%, 100%]. At the participant level, 75 (17%) participants reported <100% 3-day adherence, consisting of 82 (12%) of the visits. TFV-DP in DBS, an indicator of cumulative adherence[11], was also high overall, with the majority (53%) of TFV-DP concentrations included in the high category (≥1650 fmol/punch) compared to 12% in the low category (BLQ to <800 fmol/punch). The outcome of interest, HIV VL ≥20 copies/mL, occurred in 156 (23%) of the paired assessments. For participants who were viremic at their first visit, the median (range) HIV VL is shown in Table 1.

Predictive Value of Emtricitabine Triphosphate for Future Viremia

In a univariable model, participants with BLQ FTC-TP concentrations in DBS had higher odds for future viremia, with an OR (95% confidence interval [CI]) of 4.1 (95% CI: 2.3, 7.2; p<0.0001, Table 2). This relationship remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders, with an aOR of 3.4 (95% CI: 1.8, 6.5; p=0.0002, Table 2). When TFV-DP in DBS was added to the model, the effect of FTC-TP was attenuated, with an aOR of 1.9 (95% CI: 0.9, 4.1; p=0.090, Table 2). TFV-DP in DBS was a significant predictor of future viremia in all models (data not shown).

Table 2.

Odds ratio for risk of future HIV viral load ≥20 copies/mL by concentration of emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP) in dried blood spots (DBS) at current visit (n=667 paired assessments).

| FTC-TP | Paired assessments n (%) |

OR future viremia (95% CI) |

p-value |

*aOR future viremia (95%; CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLQ** | 56 (8%) | 4.1 (2.3, 7.2) | <0.0001 | 3.4 (1.8, 6.5) | 0.0002 |

| Quantifiable | 611 (92%) | 1 | REF | 1 | REF |

| Including TFV-DP in DBS | |||||

| BLQ | 56 (8%) | 2.6 (1.3, 5.2) | 0.006 | 1.9 (0.9, 4.1) | 0.090 |

| Quantifiable | 611 (92%) | 1 | REF | 1 | REF |

FTC-TP: emtricitabine triphosphate; BLQ: below limit of quantification; OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; TFV-DP: tenofovir diphosphate.

Adjusted for age, gender, race, body mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hematocrit, CD4+ T-cell count, and ART class.

FTC-TP in DBS was considered BLQ if it was <0.1 pmol/sample.

Predictive Value of Self-Reported Adherence for Future Viremia

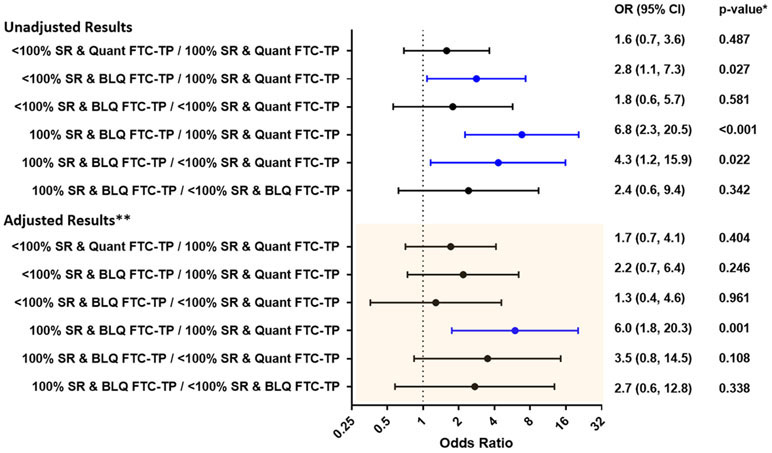

Three-day SR adherence was used in models with FTC-TP in DBS as it reflects recent dosing[8, 10]. Participants reporting <100% 3-day adherence trended towards higher odds of future viremia, but this association was not significant with an aOR of 1.7 (95% CI: 0.96, 2.9; p=0.069). We also considered whether the effect of quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS differed between participants reporting 100% 3-day adherence vs <100% by including an interaction term between these two predictors in the regression model. The mismatch between these two predictor variables was highly informative in both unadjusted and adjusted models. For the group of PWH reporting 100% 3-day adherence, those with BLQ FTC-TP in DBS had a 62% (95% CI: 42%, 78%) probability of future viremia (median [IQR] HIV VL 3,590 [290, 17,600] copies/mL) compared to 19% (95% CI: 16%, 23%) for those with quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS (Table 3 and Figure 1). After adjusting for potential confounders and for multiple comparisons, the odds for future viremia for this same group of participants reporting 100% 3-day adherence remained significant, with an aOR of 6.0 (95% CI: 1.8, 20.3; p=0.001) when comparing participants with BLQ FTC-TP to those with quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS. Among participants reporting <100% adherence this aOR was 1.3 (0.4, 4.6, p=0.961). Figure 1 shows all pair-wise comparisons performed in this interaction analysis.

Table 3.

Unadjusted probability (95% confidence interval) of future viremia based on 3-day self-reported adherence and emtricitabine triphosphate concentrations (FTC-TP) in dried blood spots (n=667 paired assessments in 433 total participants).

| 3-day SR adherence <100% n=82 paired assessments n=75 participants |

3-day SR adherence =100% n=585 paired assessments n=397 participants |

|

|---|---|---|

|

FTC-TP BLQ

*

n=56 paired assessments n=49 participants |

40% (25%, 58%) n=28 paired assessments n=27 participants |

62% (42%, 78%) n=28 paired assessments n=23 participants |

|

FTC-TP Quantifiable

n=611 paired assessments n=407 participants |

27% (17%, 41%) n=54 paired assessments n=50 participants |

19% (16%, 23%) n=557 paired assessments n=381 participants |

BLQ: below limit of quantification; SR:3-day Self-Reported adherence.

FTC-TP was considered BLQ if it was <0.1 pmol/sample. The number of participants in rows/columns may not add to 433 as participants may have moved between categories if they had more than one paired assessment.

Figure 1. Odds ratio for risk of future viremia based on 3-day self-reported adherence and emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP) concentrations in dried blood spots.

SR:3-day Self-Reported adherence; FTC-TP: emtricitabine triphosphate; Quant: Quantifiable; BLQ: Below the Limit of Quantification. *p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Tukey-Kramer adjustment.

**Adjusted for age, age, gender, race, body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, estimated using MDRD equation), CD4+ T-cell count, hematocrit, and ART class. FTC-TP in DBS was considered BLQ if it was <0.1 pmol/sample.

Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate the ability of FTC-TP to predict future viremia even among currently virally suppressed PWH, we evaluated a subset of participants who were virologically suppressed at their first visit and had paired HIV VL/DBS at a subsequent time point later in the study. Available for this analysis were 339 participants (78% of total, see Supplemental Table 1 for demographic data on n=303 suppressed participants at entry) with 478 paired assessments (71% of total). In both unadjusted and adjusted models, PWH with BLQ FTC-TP in DBS had higher odds of future viremia compared to those with quantifiable FTC-TP in DBS, with an OR 2.6 (95% CI 0.7, 10.0; p=0.167) and aOR 2.4 (95% CI: 0.6, 10.1; p=0.205). However, with only 11 paired assessments in which FTC-TP in DBS was BLQ in a currently suppressed participant (6 at baseline, median [IQR] 3-day adherence 100 [100, 100] %, Supplemental Table 1), the interpretation of these results was limited.

Discussion

In this analysis, we demonstrated that unquantifiable FTC-TP in DBS, a measure of recently missed ART doses (within 3 days when assayed using a 3-mm punch)[8, 10], can predict the development of future viremia in PWH receiving FTC-containing regimens, particularly in those who concurrently report 100% adherence. This manifested as a mismatch between a subjective (i.e., self-report) and an objective (i.e., FTC-TP in DBS) adherence measure. Among those reporting 100% adherence in the preceding 3 days, a concentration of FTC-TP in DBS that was BLQ was associated with 6 times the odds for experiencing future viremia when compared to quantifiable FTC-TP. However, FTC-TP in DBS that was BLQ was not significantly associated with future viremia in PWH who reported <100% adherence, which could be a result of an overestimation in self-report[17]. Collectively, these findings extend our previous research demonstrating that FTC-TP in DBS was associated with viral suppression at the time of a study visit and was highly predictive of 3-day adherence[10], and now establish –for the first time– that a short-term adherence measure can predict future viral rebound, particularly in those who report perfect adherence.

Although the predictive value of FTC-TP in DBS lost statistical significance after including TFV-DP in the model (which was expected), the clinical implications of our results can be highlighted in the context of several case scenarios. First, establishing the utility of FTC-TP to predict future viremia would support its use in routine clinical practice as an objective method to quantify recent dosing. Given that TFV-DP in DBS (a measure of cumulative adherence) was a more powerful predictor of future viremia in our previous analyses in this cohort[7], our findings would be particularly relevant in scenarios where only measures of short-term adherence are available. Second, the ability of an FTC-TP concentration in DBS that is BLQ to predict future viremia in PWH reporting full adherence provides compelling clinical information, as it could help identify a subset of patients where self-reported adherence (apparently incorrect) could have harmful consequences. This highlights the potential clinical impact of point-of-care short-term adherence measures (e.g., drug concentrations in urine) for which our findings provide actionable information for clinicians. Taken together, these potential applications of FTC-TP in DBS emphasize the advantage of utilizing objective pharmacologic measures when assessing adherence and interpreting HIV VL data in clinical practice.

The utility of a short-term adherence measure to predict future viremia is a considerable advancement in the field of ART adherence and treatment monitoring in PWH. As previous studies have demonstrated a direct correlation between TFV concentrations in urine and FTC-TP in DBS[18], it is conceivable that the predictive value that we established for FTC-TP in DBS could also extend to TFV in urine. This correlation could be of additional importance in resource-limited settings, where short-term adherence measures (like TFV in urine, in particular when it is used at the point-of-care) could be less expensive and more readily available than HIV VL and other pharmacologic adherence measures such as drug concentrations in DBS (i.e., TFV-DP and FTC-TP, which are also being evaluated for point-of-care testing[19]) or hair. Regarding other short-term adherence measures, antiretroviral concentrations in plasma have been previously associated with viral suppression and drug resistance[20-22], but their association with future viremia has not been evaluated, to our knowledge. Studies assessing whether the predictive value of FTC-TP in DBS extends to other pharmacologic measures of short-term adherence, such as drug concentrations in urine or plasma, are required, and an ongoing study is already evaluating TFV in urine for this purpose (NCT04341779).

The ability of a BLQ concentration of FTC-TP in DBS to predict future viremia in PWH who had a mismatch with self-reported adherence is a powerful characteristic, because it could help identify a group of patients who may intentionally (or unintentionally) overestimate their recent adherence at the time of a clinic visit[1, 23]. Similarly, it could be used to detect the onset of a period of suboptimal adherence that would not have been identified by self-report alone. This discerning power has only been previously reported for a measure of cumulative exposure (i.e., TFV-DP in DBS)[7], but not for a short-term adherence measure. Furthermore, establishing the probability for future viremia according to the presence or absence of a drug concentration:adherence mismatch (Table 3) could be a clinically-useful resource, because it can be conveyed to patients and clinicians in simple terms. It could also serve as an initial point of conversation to identify barriers to adherence in PWH who report high adherence in whom a discussion about adherence would not otherwise be initiated. Likewise, this could trigger timely adherence counseling in this patient population and prevent an adverse outcome such as viremia and/or HIV transmission.

Several strengths are offered by our study. First, our analysis was derived from a large sample size within a diverse “real-world” clinical cohort with a wide range of ART adherence. This allowed for our conclusions to be applicable and generalizable to a relevant population of PWH. Second, FTC-TP was able to identify a vulnerable group of patients whose clinical providers would consider fully adherent based on perfect self report, and in whom adherence would not have otherwise been thoroughly discussed during a clinical visit. This could facilitate a supportive conversation with these patients based on an objective measure that goes beyond self-report and that can be easily understandable to patients[23]. Third, inexpensive measures of short-term adherence are already available at the point-of-care (i.e., TFV in urine)[24, 25], making our results immediately implementable into current clinical practice. It should be noted that TFV-DP was a more powerful predictor of future viremia. As noted, this was not unexpected, as viral rebound usually requires sustained prolonged periods of low adherence[26], which could be best captured by a measure of cumulative exposure like TFV-DP. However, point -of -care assays for TFV-DP (and FTC-TP) are not yet available. Since both TFV-DP and FTC-TP in DBS are simultaneously assayed in the same DBS (usually without additional cost[14] and includes TAF-based regimens[27]), future studies will need to assess the clinical utility of combining both TFV-DP and FTC-TP in DBS to maximize their adherence information. In addition, the number of paired assessments where participants reported <100% adherence in the last 3 days was overall small, which could have limited our ability identify a significant predictive value from this adherence measure. Last, our findings will need to be replicated using other measures of short-term adherence –in particular using point-of-care urine testing– before they can be implemented in clinical practice.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that FTC-TP in DBS, as measure of short-term adherence, can predict future viremia in PWH and can be used to identify patients in whom self-report may have over-estimated recent adherence, which could lead to clinically relevant consequences. As measures of short-term adherence (e.g., rapid tests for tenofovir in urine and point-of-care concentrations in DBS) continue to be developed for clinical implementation, future studies are needed to evaluate whether these adherence measures can improve clinical outcomes and are cost-effective in PWH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants and all the personnel at the Colorado Antiviral Pharmacology Laboratory at the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences for their invaluable assistance and support of this study. We would also like to thank Dr. Steven C. Johnson, director of the University of Colorado Hospital HIV program and the medical assistants (Nancy Olague, Brittany Limon, Ariel Cates, Maureen Sullivan and Missy Sorrell) at the University of Colorado Hospital-Infectious Disease Group Practice for their invaluable contributions and support of this study.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [K23 AI104315 to J.C.M.; R01 AI122298 to P.L.A.]. P.L.A. and J.J.K. have received research funding from Gilead Sciences, paid to their institution. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. J.J.K has received research support from Gilead Sciences paid to her institution. PLA received personal fees and received research support from Gilead Sciences paid to his institution. Other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Haberer JE Adherence Measurements in HIV: New Advancements in Pharmacologic Methods and Real-Time Monitoring. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan S, Detels R, Mehta SH, Macatangay BJ, Kirk GD, Jacobson LP Level of adherence and HIV RNA suppression in the current era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). AIDS Behav 2015; 19(4):601–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viswanathan S, Justice AC, Alexander GC, Brown TT, Gandhi NR, McNicholl IR, et al. Adherence and HIV RNA Suppression in the Current Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69(4):493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd KK, Hou JG, Hazen R, Kirkham H, Suzuki S, Clay PG, et al. Antiretroviral Adherence Level Necessary for HIV Viral Suppression Using Real-World Data. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2019; 82(3):245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Morrow M, Coyle RP, Coleman SS, Gardner EM, Zheng J-H, et al. Tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots is strongly associated with viral suppression in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018; 68(8):1335–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandhi M, Ameli N, Bacchetti P, Anastos K, Gange SJ, Minkoff H, et al. Atazanavir concentration in hair is the strongest predictor of outcomes on antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52(10):1267–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow M, MaWhinney S, Coyle RP, Coleman SS, Gardner EM, Zheng J-H, et al. Predictive Value of Tenofovir Diphosphate in Dried Blood Spots for Future Viremia in Persons Living With HIV. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019; 220(4):635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castillo-Mancilla J, Seifert S, Campbell K, Coleman S, McAllister K, Zheng JH, et al. Emtricitabine-Triphosphate in Dried Blood Spots as a Marker of Recent Dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60(11):6692–6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spinelli MA, Haberer JE, Chai PR, Castillo-Mancilla J, Anderson PL, Gandhi M Approaches to Objectively Measure Antiretroviral Medication Adherence and Drive Adherence Interventions. Current HIV/AIDS reports 2020; 17(4):301–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frasca K, Morrow M, Coyle RP, Coleman SS, Ellison L, Bushman LR, et al. Emtricitabine triphosphate in dried blood spots is a predictor of viral suppression in HIV infection and reflects short-term adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2019; 74(5):1395–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, Rower JE, Meditz A, Gardner EM, Predhomme J, et al. Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29(2):384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano TP, Guzman D, Clark R, Charlebois ED, Bangsberg DR Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV clinical trials 2004; 5(2):74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amico KR, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Shuper PA, Redding CG, Konkle-Parker DJ, et al. Visual analog scale of ART adherence: association with 3-day self-report and adherence barriers. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2006; 42(4):455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng JH, Rower C, McAllister K, Castillo-Mancilla J, Klein B, Meditz A, et al. Application of an intracellular assay for determination of tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate from erythrocytes using dried blood spots. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2016; 122:16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson PL, Liu AY, Castillo-Mancilla JR, Gardner EM, Seifert SM, McHugh C, et al. Intracellular Tenofovir-Diphosphate and Emtricitabine-Triphosphate in Dried Blood Spots following Directly Observed Therapy. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2018; 62(1):e01710–01717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyle RP, Morrow M, Coleman SS, Gardner EM, Zheng JH, Ellison L, et al. Factors associated with tenofovir diphosphate concentrations in dried blood spots in persons living with HIV. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75(6):1591–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav 2006; 10(3):227–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spinelli MA, Glidden DV, Rodrigues WC, Wang G, Vincent M, Okochi H, et al. Low tenofovir level in urine by a novel immunoassay is associated with seroconversion in a PrEP demonstration project. AIDS (London, England) 2019; 33(5):867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pu F, Pandey S, Bushman LR, Anderson PL, Ouyang Z, Cooks RG Direct quantitation of tenofovir diphosphate in human blood with mass spectrometry for adherence monitoring. Anal Bioanal Chem 2020; 412(6):1243–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Serna A, Swenson L, Watson B, Zhang W, Nohpal A, Auyeung K, et al. A single untimed plasma drug concentration measurement during low-level HIV viremia predicts virologic failure. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2016; 22(12):1004. e1009–1004. e1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calcagno A, Pagani N, Ariaudo A, Arduino G, Carcieri C, D’Avolio A, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of boosted PIs in HIV-positive patients: undetectable plasma concentrations and risk of virological failure. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2017; 72(6):1741–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darwich L, Esteve A, Ruiz L, Bellido R, Clotet B, Martinez-Picado J Short communication Variability in the plasma concentration of efavirenz and nevirapine is associated with genotypic resistance after treatment interruption. Antiviral therapy 2008; 13:945–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hebel S, Kahn-Woods E, Malone-Thomas S, McNeese M, Thornton L, Sukhija-Cohen A, et al. Brief Report: Discrepancies Between Self-Reported Adherence and a Biomarker of Adherence in Real-World Settings. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2020; 85(4):454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandhi M, Bacchetti P, SpinelliI MA, Okochi H, Baeten JM, Siriprakaisil O, et al. Validation of a urine tenofovir immunoassay for adherence monitoring to PrEP and ART and establishing the cut-off for a point-of-care test. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2019; 81(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daughtridge G, Hebel S, Larabee L, Patani H, Cohen A, Fischl M, et al. Development and clinical use case of a urine tenofovir adherence test. In: HIV Diagnostics Conference Atlanta; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothenberger MK, Keele BF, Wietgrefe SW, Fletcher CV, Beilman GJ, Chipman JG, et al. Large number of rebounding/founder HIV variants emerge from multifocal infection in lymphatic tissues after treatment interruption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015; 112(10):E1126–E1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yager J, Castillo-Mancilla J, Ibrahim ME, Brooks KM, McHugh C, Morrow M, et al. Intracellular Tenofovir-Diphosphate and Emtricitabine-Triphosphate in Dried Blood Spots Following Tenofovir Alafenamide: The TAF-DBS Study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2020; 84(3):323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.