Abstract

Context

X-Linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) is a lifelong metabolic disease with musculoskeletal comorbidities that dominate the adult clinical presentation.

Objective

The adult XLH disorder has yet to be quantified on the basis of the physical and functional limitations that can affect activities of daily living. Our goal was to report the impact of the musculoskeletal manifestations on physical function.

Design and setting

Musculoskeletal function was evaluated by validated questionnaires and in an interdisciplinary clinical space where participants underwent full-body radiologic imaging, goniometric range of motion (ROM) measurements, general performance tests, and kinematic gait analysis.

Patients

Nine adults younger than 60 years with a diagnosis of XLH and self-reported musculoskeletal disability, but able to independently ambulate, were selected to participate. Passive ROM and gait analysis were also performed on age-approximated controls to account for differences between individual laboratory instrumentation.

Results

Enthesophytes, degenerative arthritis, and osteophytes were found to be consistently bilateral and diffusely present at the spine and synovial joints across participants, with predominance at weight-bearing joints. Passive ROM in adults with XLH was decreased at the cervical spine, hip, knee, and ankle compared to controls. Gait analysis relative to controls revealed increased step width, markedly increased lateral trunk sway, and physical restriction at the hip, knees, and ankle joints that translated into limitations through the gait cycle.

Conclusions

The functional impact of XLH musculoskeletal comorbidities supports the necessity for creating an interprofessional health-care team with the goal of establishing a longitudinal plan of care that considers the manifestations of XLH across the lifespan.

Keywords: X-linked hypophosphatemia, range of motion, gait analysis, enthesopathy, degenerative arthritis, osteophyte

X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) is the most common of the hereditary phosphate wasting disorders (1-4). XLH arises by X-linked dominant inheritance or by spontaneous inactivation of the PHEX gene (phosphate-regulating gene with homology to endopeptidases on the X chromosome) and is characterized by childhood rickets and defective bone mineralization (5, 6). PHEX encodes a zinc-dependent endopeptidase that regulates levels of the circulating phosphate-regulating hormone FGF23 by a currently unknown mechanism (7, 8). Dysregulation of FGF23 results in renal phosphate wasting due to inhibition of tubular sodium-coupled phosphate transport. FGF23 also suppresses 1α-hydroxylase activity and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production, which may potentiate reduced plasma phosphate concentration because of impaired intestinal absorption of dietary phosphate (9).

XLH is a lifelong metabolic disease with musculoskeletal comorbidities that dominate the clinical picture of the adult disorder (6). Characteristic complications include pervasive and early-onset mineralizing enthesopathies and degenerative osteoarthritis (OA) with marginal osteophytes, osteomalacia, pseudofracture, fractures, a persistence of dental abscesses without caries, chronic pain, fatigue, hearing loss, and tinnitus (6, 10-12). Skeletal manifestations include varus or valgus deformity, tibial torsion and variable deformities as a result of childhood rickets and fractures, and/or surgical intervention and change in bone growth patterns over the lifespan (1, 13).

Unlike pediatric patients, adults are not uniformly treated, with therapy recommended for postfracture healing or orthopedic surgery, treatment of persistent osteomalacia, or to reduce bone-related pain (6, 14). Nonetheless, treatment using standard phosphate supplementation and calcitriol can be limited by toxicities like nephrocalcinosis and secondary hyperparathyroidism (15). A newly approved therapy, burosumab, is a fully human FGF23 monoclonal antibody that has demonstrated significant benefit in the pediatric population and was superior to conventional therapy (16, 17). These benefits included increased serum phosphate and lowered serum alkaline phosphatase levels, a reduction in the severity of the rachitic growth plate and associated gain on stature, and a reduction in pain (16, 17). In the adult population, burosumab showed significant improvement in biochemical and bone-marker values, including fracture-healing. Standardized self-reported questionnaires assessing pain, stiffness, and physical function related to OA, also revealed improvement in stiffness, physical function, and pain (18-20). These are important parameters in a population in which pain and limitations of physical function dominate the patient experience (21). Indeed, the 2 major complications of adult XLH, a mineralizing enthesopathy and degenerative OA, are recognized irreversible pathologies and are thought to be resistant to standard therapies in XLH (6, 22, 23). This is compounded by the involvement of physiologically avascular tissues which includes the fibrocartilaginous entheses and articular cartilages, populated with terminally differentiated cells that have very limited capacity for repair and regeneration (10, 11). The development of enthesophytes, degenerative arthritis, and osteophytes highlight the necessity of evaluating the physical limitations of those with XLH because of the severity and earlier onset in adulthood than in the unaffected population (24).

Despite documentation of these comorbidities, there is a lack of available data correlating the physical manifestations of the disease with functional range of motion (ROM), gait and mobility, fall-risk, pain, and quality of life parameters. Previous studies have suggested the enthesopathies identified in XLH can affect functional range of motion (10). In this study, we report the major functional impact of the musculoskeletal manifestations of the adult disorder and illuminate the effect on function and ambulation that gives rise to gait deviations. Ambulation is an important functional task, and analysis of gait provides insight into physical impairments and compensatory mechanisms that become apparent during the gait cycle. These data are routinely used in lumbar and lower extremity evaluations, including neurological/neuromuscular disorders like cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, stroke, spinal cord injuries, and scoliosis. Data obtained from gait analysis can be used to evaluate evidence-based interventions for patients such as physical therapy, orthotics, bracing, and surgical interventions, as well as monitoring response to therapeutics.

Another arm of this study recently published was simultaneously conducted to build theory about the psychosocial impact of the disease in the affected adult population, particularly to identify why and how individuals engage with health-care services, and to identify common themes that may relate to effective management of this population (21). Together, these data will provide essential information to guide adult patients and their health-care providers, many of whom lack experience in rare metabolic bone disorders, on appropriate evidence-based interventions for individuals with a diagnosis of XLH.

Methods

Study population and demographics

The study was approved by the human experimentation committee/institutional review board (HEC/IRB) at Quinnipiac University. All participants provided written informed consent before the study, including risks of ionizing radiation and rationale for the use of diagnostic imaging for the study. Participants also agreed to an occupational therapy assessment and a semistructured interview by social work; these data and other quality of life measures are reported in a separate study (21). Inclusion criteria included adults younger than 60 years with a confirmed diagnosis of XLH and self-reported musculoskeletal disability. Exclusion criteria included individuals unable to independently walk a distance of 200 feet (61 m) without the use of an assistive device or with an adhesive tape allergy. An upper age limit of 60 years was chosen relative to controls based on data from the World Health Organization global burden of disease that the prevalence of OA is estimated to affect 9.6% of men and 18% of women older than 60 years (25). Eligibility was determined using a self-reported questionnaire sent to respondents regarding age of diagnosis, medical and surgical history, and physical activity at the time of the study. Age-approximated adult volunteer controls were recruited from the Standardized Patient and Assessment Center at the Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine at Quinnipiac with no known history or treatment for OA or bone spurs or use of pain medications. Participants in the study consisted of 9 individuals and included male (n = 5) and female (n = 4) adults (age 53.6 ± 5.3 years); at the time of this study, no participants had received burosumab. Passive ROM, gait analysis, and general performance tests were also performed on age-approximated, male and female controls to account for differences between individual laboratory instrumentation and software variability that exists between gait laboratories.

Diagnostic radiology

Full-body anteroposterior and lateral radiography was performed to evaluate the prevalence of pathological musculoskeletal findings and to correlate these findings with the physical manifestations of the upper and lower body motion. Images were independently evaluated by 2 board-certified radiologists. X-rays were not obtained at all sites because of physical limitations; 1 patient was excluded who had reached the annual radiation limit at the time of the study. Spinal kyphosis or scoliosis were determined using OsiriX open-source imaging software using the Cobb angle technique. Kyphosis greater than 40° and scoliosis greater than or equal to 10° were considered abnormal.

Physical and functional assessment

Passive ROM measurements in participants, and age-approximated, sex-matched controls, were used to evaluate the available ROM of the hip, knee, and ankle joints and the cervical spine. Participants were specifically positioned (prone, supine, standing, sitting) to obtain goniometric measurements for ROM of lower extremity ambulatory propulsion joints. Measurements were completed in the sagittal plane to correlate with anteroposterior radiographic imaging and gait analysis. Bilateral ROM data were reported.

Several validated tools were used to evaluate musculoskeletal function in individuals with XLH relative to sex- and age-matched controls. The Berg Balance Score is a 56-point scale used to assess balance of 14 functional tasks. A score less than 45 corresponds with a greater fall risk (26). Bilateral muscle strength was assessed using manual muscle testing (MMT) and all measurements were conducted by a single experienced orthopedic physical therapist for each subject, to ensure the high intra-rating reliability and validity that has been reported for the MMT test (27, 28). A maximum score of 5 is assigned for each task completed based on effective performance of limb movement to the end of its available range and against an opposed manual resistance by the practitioner (29). In addition, the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) questionnaire was used to assess self-reported lower limb dysfunction of 20 physical activities using a scale ranging from 4 (no difficulty) to 0 (a lot difficulty), for a maximum score of 80 (30).

Gait instrumentation and analysis

Kinematic measurements of the trunk, hips, knees, and ankles were recorded as joint angular displacements in the sagittal, coronal, and transverse planes. The complete gait cycle was analyzed in the sagittal plane reflecting flexion and extension of each of the joints; contributions of the coronal and transverse planes to gait were also considered when significant. Participants wore fitted clothing and orthotic-free sneakers. A total of 26 retroreflective markers were placed over specific bony landmarks located on the trunk, pelvis, and upper and lower extremities using double-sided adhesive tape (31). Briefly, the marker set consisted of 4 rigid marker triads attached to the distal ends of the femurs and lower legs, and single markers placed bilaterally over the midpoint of the posterior superior iliac spine, both anterior superior iliac spines, the midpoint of the acromions, lateral humeral epicondyles, midpoint between the radius and styloid processes, midpoint of the heel counter of the shoes, and over the head of the second metatarsals. A 10-camera motion analysis system (Motion Analysis Corporation) sampling at a frequency of 120 Hz recorded the displacements of the markers while control and XLH individuals walked in a straight line for 20 feet (6 m) at their self-selected walking speed. Five walking trials were recorded for each participant to obtain temporal, spatial, and kinematic measurements for the complete gait cycle. Gait parameters for control participants were recorded to serve as a reference by which to compare any deviations in kinematics encountered. Joint angles for controls were consistent with documented values for age- and sex-matched populations, with intrasubject joint variability similar between controls (32).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics include frequencies for qualitative variables and means with SDs for quantitative variables. Comparisons between XLH patients with controls used an independent samples t test or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test when normality and equal variance assumptions were not met. With 9 patients and matched controls, the study had sufficient power (> 0.8) to detect large and clinically meaningful differences (Cohen’s d ≥ 1.0) between groups. For trunk analysis of lateral flexion in the frontal plane, the difference between right and left sway were calculated for each participant, then a t test comparing control and XLH groups on the different scores was conducted. Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS version 25 and the α level for statistical significance was set at .05. With the exception of age at diagnosis, data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Results

Study population

Baseline demography for age and sex for gait and ROM studies was comparable between XLH and controls (Table 1). A majority of XLH cases were diagnosed in childhood, with the exception of one participant, who was diagnosed at age 39 years. A significant height difference was found between groups (P = 0.005). All XLH individuals reported bone and joint pain, which was further exacerbated by activity. XLH participants reported a mean score of 3.3 ± 1.6 on a 10-point pain scale at rest with a subsequent 6.7 ± 1.7 with activity. All participants reported difficulty with walking long distances. Further, use of pain medications was increased in the XLH population, with half of the XLH individuals reporting regular use of over-the-counter pain medications and 80% reporting use of prescription pain medication at the time of survey administration. XLH individuals reported receiving standard treatment (oral phosphate salts/calcitriol) for phosphate-wasting in childhood (80%), and variably in adulthood (100%), treatment with calcitriol was most consistent.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Demographics | XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Controls (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53.6 (5.4) | 52.6 (5.7) | > .05 |

| M:F | 5:4 | 2:3 | – |

| Height, cm | 151.1 (10.5) | 168.6 (8.3) | .005 |

| Age at diagnosis, median, y | 4 | – | – |

| Inherited/Spontaneous | 5:4 | – | – |

| Self-reported quality of life measures of adults with XLH | XLH | ||

| Do you display short stature? | 9/9 | ||

| Do you display bowing of the legs? | 8/9 | ||

| Do you display in-toeing (pigeon toed)? | 4/9 | ||

| Do you have bone pain? | 9/9 | ||

| Do you have joint pain? | 9/9 | ||

| Have you been diagnosed with arthritis? | 8/9 | ||

| Have you had multiple dental abscesses? | 9/9 | ||

| Do you use a device to assist you with walking? | 6/9 | ||

| Have you ever been under the care of a physical therapist? | 7/9 | ||

| Have you ever been under the care of an occupational therapist? | 1/9 | ||

| Do you find it difficult to walk for short distances? | 7/9 | ||

| Do you find it difficult to walk long distances? | 9/9 | ||

| Have you been diagnosed with bone spurs | 8/9 | ||

| Do you have bony cysts on your hands or feet? | 7/9 | ||

| Do you experience limited motion of your arms? | 8/9 | ||

| Do you find it difficult to reach for items? | 7/9 | ||

| Do you experience muscle weakness? | 7/9 | ||

| Do you have limited movement of your neck? | 6/9 | ||

| Do you have limited movement in your upper body? | 7/9 | ||

| Do you have an unusual gait when you walk? | 8/9 | ||

| Do you experience pain when you walk? | 8/9 | ||

| Do you use any adaptive equipment to complete daily tasks? | 7/9 | ||

| Have you undergone any corrective surgery as a child? | 6/9 | ||

| Have you been diagnosed with spinal stenosis (nerve pinching)? | 5/9 | ||

| Do you take over-the-counter pain medication | 4/9 | ||

| Do you take prescription pain medication? | 8/9 | ||

| Received treatment for XLH in childhood (M, F) | 3/5, 4/4 | ||

| Received treatment for XLH in adulthood (M, F) | 5/5, 4/4 | ||

| Have you ever broken or fractured bone(s)? | 5/9 |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; XLH, X-linked hypophosphatemia

Skeletal manifestations, upper body

Radiographic images were used to document skeletal manifestations of the disease process and to determine the extent of physical correlation with data obtained from functional studies. Key findings are shown in Table 2 and reveal strikingly similar patterns of involvement between participants.

Table 2.

Radiographic findings in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia

| Spine | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Calcification of nuchal ligament | 3/7 |

| Enthesophyte, cervical spinea | 6/7 |

| Enthesophyte, thoracic spine | 6/8 |

| Enthesophyte, lumbar spine | 7/8 |

| Kyphosis | 6/8 |

| Sclerosis of sacroiliac joint, lumbar spine | 5/8 |

| Sclerosis of facet joints, lumbar spine | 6/8 |

| Dextroconvex or levoconvex curvature | 5/8 |

| Shoulder girdle | Frequency |

| Enthesophyte, attachment of triceps to humerus | 6/8 |

| Enthesophyte, acromioclavicular ligament | 5/8 |

| Osteophyte, acromioclavicular joint | 3/8 |

| Elbowa | Frequency |

| Enthesophyte, insertion triceps tendon at olecranon process | 7/7 |

| Osteophyte, radiohumeral joint | 6/7 |

| Degenerative arthritis of the elbow joint | 4/7 |

| Wrist and handa | Frequency |

| Osteophyte, trapeziometacarpal joint 4/7 | 4/7 |

| Enthesophyte, ligaments of carpals, metacarpal, and phalangeal joints 3/7 | 3/7 |

| Degenerative arthritis of hand and wrist joints 6/7 | 6/7 |

| Pelvis | Frequency |

| Sclerosis of sacroiliac joint | 5/8 |

| Enthesophyte, origin of gluteus medius at iliac crest | 6/8 |

| Enthesophyte, iliofemoral ligament | 3/8 |

| Enthesophyte, origin of hamstrings at ischial tuberosity | 6/8 |

| Enthesophyte, sacrospinous ligament | 3/8 |

| Hip joint | Frequency |

| Enthesophyte, gluteal muscles insertion at greater trochanter | 8/8 |

| Enthesophyte, insertion of iliopsoas into lesser trochanter | 7/8 |

| Degenerative arthritis at hip joint | 7/8 |

| Knee and lower leg | Frequency |

| Calcification of tibia-fibula interosseous membrane | 7/8 |

| Enthesophyte, patellar tendon insertion at patella | 6/8 |

| Enthesophyte, quadriceps tendon insertion at patella | 6/8 |

| Degenerative arthritis of knee | 7/7 |

| Ankle and foot | Frequency |

| Degenerative tibiotalar joint 4/8 | 4/8 |

| Enthesophyte, insertion of Achilles tendon at calcaneus 7/8 | 7/8 |

| Enthesophyte, origin and insertion of cuneonavicular ligament 5/8 | 6/8 |

| Enthesophyte, origin and insertions of talonavicular ligament 7/8 | 7/8 |

aX-rays were not obtained at all sites because of physical limitations; 1 patient was excluded who had reached the annual radiation limit at study time.

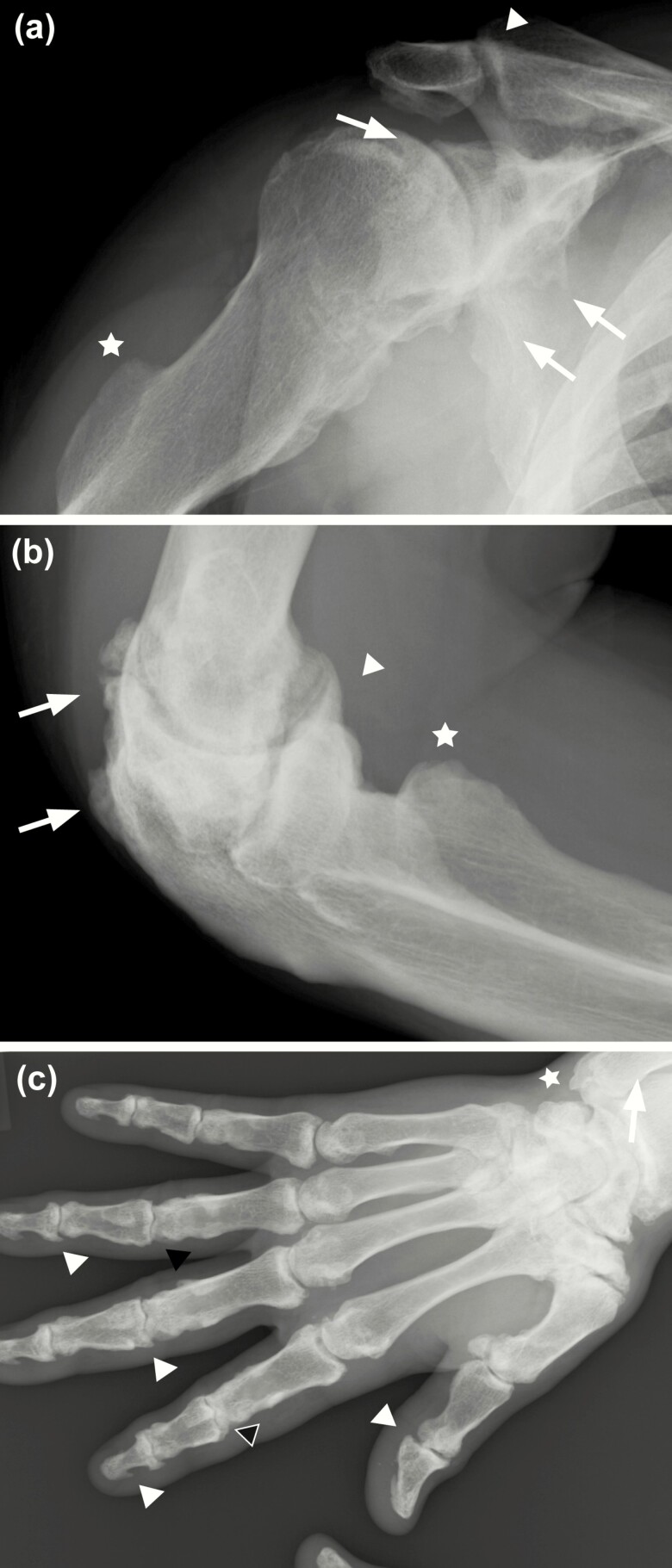

Upper body findings included examination of all spinal levels and full upper extremity. Radiographical presentation of the upper extremity included degenerative OA, marginal osteophyte formation, and juxtarticular sclerotic changes of the shoulder girdle, elbow, wrist, and hand (Fig. 1, Table 2). In the shoulder girdle, XLH individuals presented with degenerative OA at the acromioclavicular joint and pronounced osteophytic changes at the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 1A). Distal to the shoulder, enthesophytes of the triceps attachment to the humerus were common. A majority of XLH participants had osteophytes present at the humeroradial joint, and elbow joint space was significantly compromised (Fig. 1B). Further, enthesophytes at the olecranon process, attachment site of the triceps brachii tendon, were present in a majority of individuals. The wrist and hand of XLH participants presented with degenerative OA at the carpometacarpal, metacarpophalangeal, and interphalangeal joints (Fig. 1C). OA and osteophytes were most severe at the trapeziometacarpal joint across all participants. XLH individuals with advanced presentation of the disease (highest cumulative sites involved) had significant spurring at the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints and tips of the distal phalanges with shortening of the metacarpal and phalangeal bones (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Radiographic imaging of the right upper extremity of a 54-year-old man with X-linked hypophosphatemia, representative of study participants. A, Mild degenerative changes consistent with age-related arthritis are identified at the acromioclavicular joint and inferior aspect of the acromion (arrowhead). Osteophytes are present at the glenohumeral joint (arrows) with advanced arthritic changes. Humeral shaft is shortened with extensive calcification of the linea aspera (star). B, Joint narrowing and juxtarticular sclerotic changes are present at the elbow joint. Enthesophytes identified at the attachment of the triceps tendon to the olecranon and proximal portion of the ulna (arrows). Osteophyte formation is present at the humeroradial joint (arrowhead) and cortical irregularity identified at the radial tuberosity (star). C, Significant joint space narrowing present at the wrist, carpal, and carpal-metacarpal joints. Radial subarticular sclerosis and hypertrophic spurring present at the wrist (star). Scattered sclerosis and hypertrophic spurring evident within the carpal and carpal-metacarpal joints (white arrows). Metacarpal and phalanges are shortened with widespread regions of sclerosis. Joint space narrowing and juxtarticular cystic lucency present at the distal (DIP) and proximal interphalangeal joints (PIP) (black arrowheads). Diffuse hypertrophic spurring present at the DIP and PIP joints (white arrowheads).

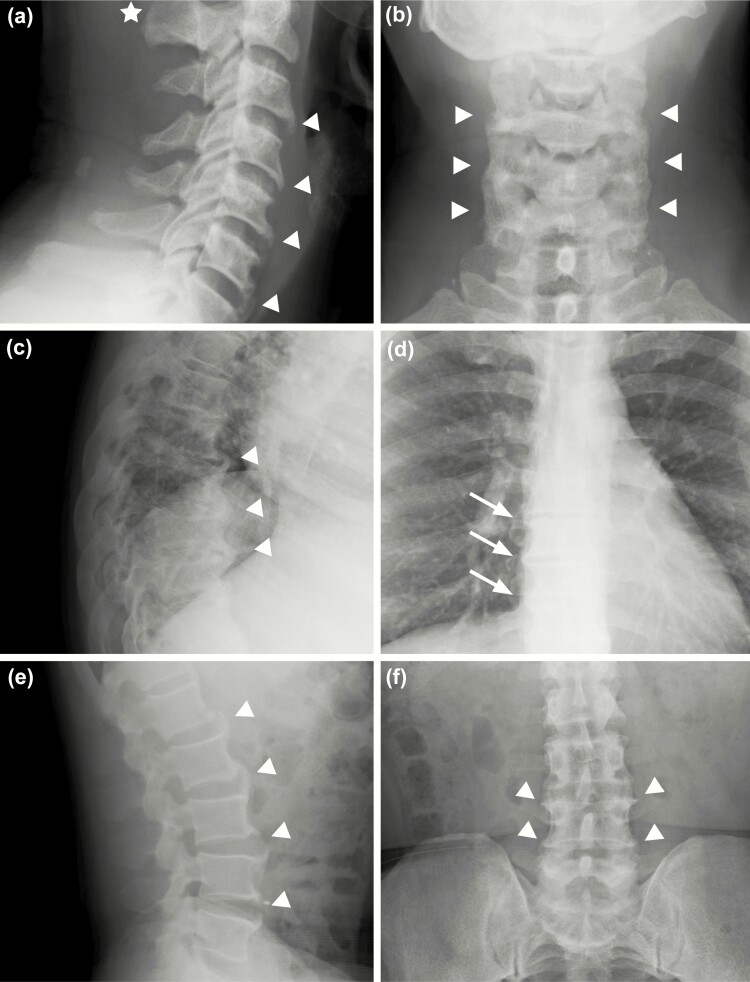

All had radiological evidence of spinal abnormalities. Cervicothoracic kyphosis was present in 6 out of the 8 participants (Cobb angle > 40°) and dextroconvex or levoconvex curvature of the thoracic spine was observed in 5 out of 8 individuals. Of the 5 participants, 3 had a Cobb angle greater than 10°, the minimum angulation to define scoliosis. Straightening of normal lumbar lordosis was also observed in half the participants (Table 2). Characteristic appearance of the spinal column for XLH individuals in this study presented as anterior osteophyte bridging, lateral and posterior enthesophyte formation of the cervical spine, thoracolumbar enthesophytes and bridging, mild-to-moderate levoconvex scoliosis, and/or cervicothoracic kyphosis (Fig. 2A-F). Participants who had evidence of sclerosis, enthesophytes, and scoliosis (Table 2), also displayed near complete fusion of the spine (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Radiographic imaging of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine of a 52-year-old man with X-linked hypophosphatemia, representative of study participants. A, Cervical imaging shows calcification of the nuchal ligament (star), and anterior longitudinal ligament in the mid- and distal anterior cervical segments (arrowheads) and B, prominent anterior bridging of C5 to C7. C, Thoracic imaging shows disc space narrowing and anterior enthesophytes (arrowheads); C, mild kyphosis also noted and D, lateral osteophyte formation in the mid- and distal thoracic spine (arrows). E and F, Osteophyte formation of all lumbar segments (arrowheads).

Skeletal manifestations, lower body

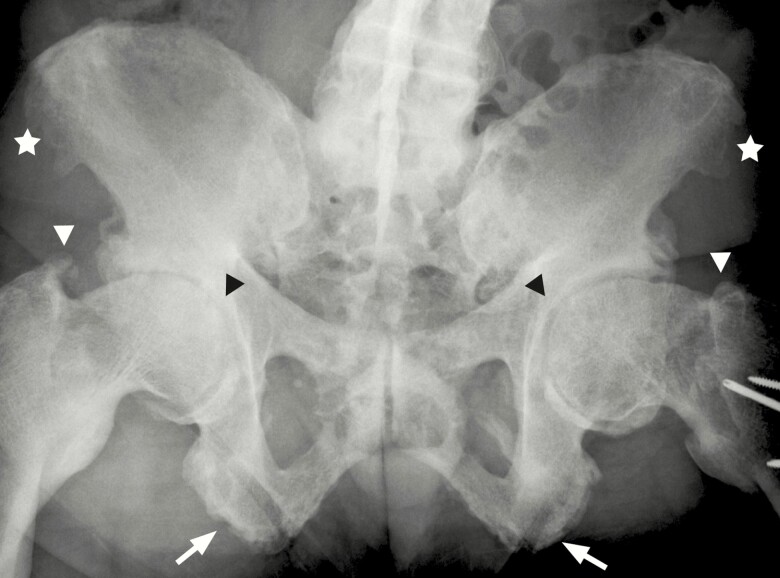

Significant radiographic findings, summarized in Table 2, were identified in all primary weight-bearing joints of the lower body, including the pelvic girdle, hips, knees, and ankles. Findings at the pelvic girdle of OA and mineralizing enthesophytes were most similar between XLH individuals. More than half of the XLH participants had sclerosis of the sacroiliac joint. Further, enthesophytes were observed in a number of ligament and tendon insertion sites of the pelvis, including the inguinal, sacrospinous, and iliofemoral ligaments. The most prevalent findings among XLH individuals were enthesophytes at the origin of the gluteus medius on the iliac crest and at the origin of hamstrings muscle at the ischial tuberosity (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Radiographic imaging of the lumbar spine and pelvis of a 54-year-old man with X-linked hypophosphatemia, representative of study participants. Levoconvex scoliosis with disc space narrowing and near total fusion present at the lumbar spine. Enthesophytes present at the iliac crests bilaterally (star). Moderate to advanced arthritic changes and joint space narrowing are present at both acetabuli (black arrowhead). Grossly deformed femoral head and neck and extensive enthesophyte formation at the attachment of the gluteal muscles to the greater trochanter (white arrowhead). Postoperative changes with plate and screws due to prior facture are present at the left hip. Enthesophytes are present at the origin of the hamstrings at the ischial tuberosities (arrows).

In the lower extremity, all XLH individuals, apart from one participant with joint replacement, had bilateral enthesophytes at each major joint (Table 2). At the hip joint, XLH individuals characteristically presented with subarticular sclerosis, acetabular osteophytic spurring, joint space narrowing, flattening of the femoral heads, and deformities of the femoral neck. Further, the presence of mineralized enthesophytes at the greater and lesser trochanters was a consistent finding (Table 2, Fig. 3).

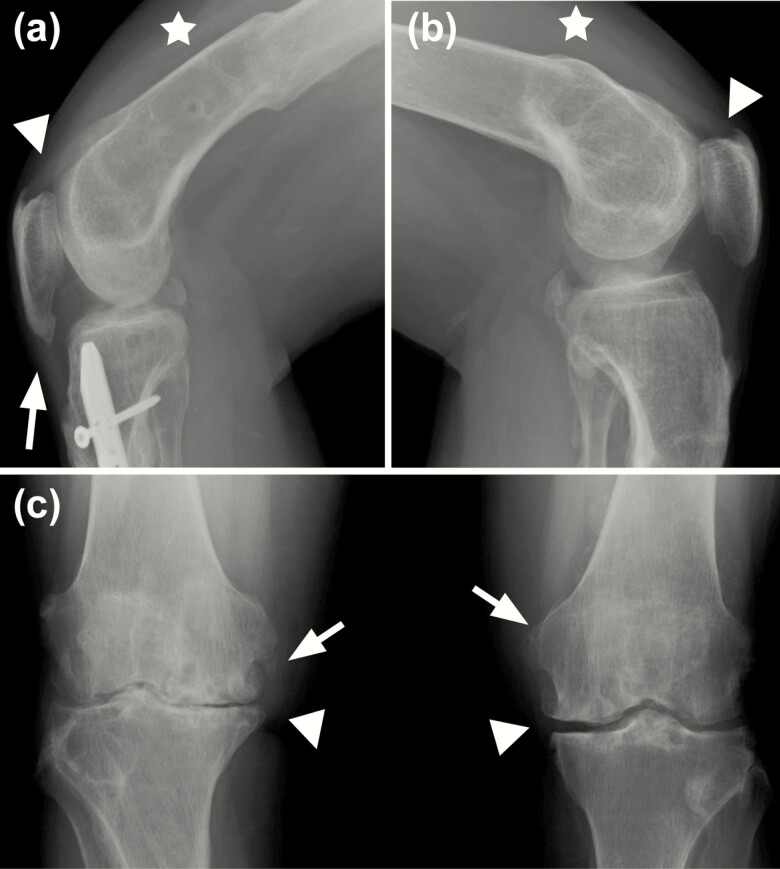

At the knee, radiological findings were characterized by degenerative OA at the knee compounded by the bowing of femoral shafts (Table 2). Further, enthesophytes of the patellar and quadriceps tendon were consistent across the majority of XLH individuals (Table 2, Fig. 4). Decreased retropatellar spacing, patellar spurring, and torsional deformities due to femoral fracture or bowing were also observed in a subset of patients.

Figure 4.

Radiographic imaging of the knee joints. A, right knee, and B, left knee, of a 48-year-old man with X-linked hypophosphatemia, representative of study participants. Pronounced osteomalacia with bilateral deformities of the femoral shafts related to previous fractures (star) and significant reduction of the patellofemoral joint space. Enthesophytes are present bilaterally at the quadriceps (arrowheads) and patellar tendons (arrows). A, Intramedullary rod present in the diaphysis of the tibia due to prior fracture. C, Anteroposterior image of a 50-year-old woman showing bilateral diminished joint space (arrowheads) and marginal osteophytes (arrows).

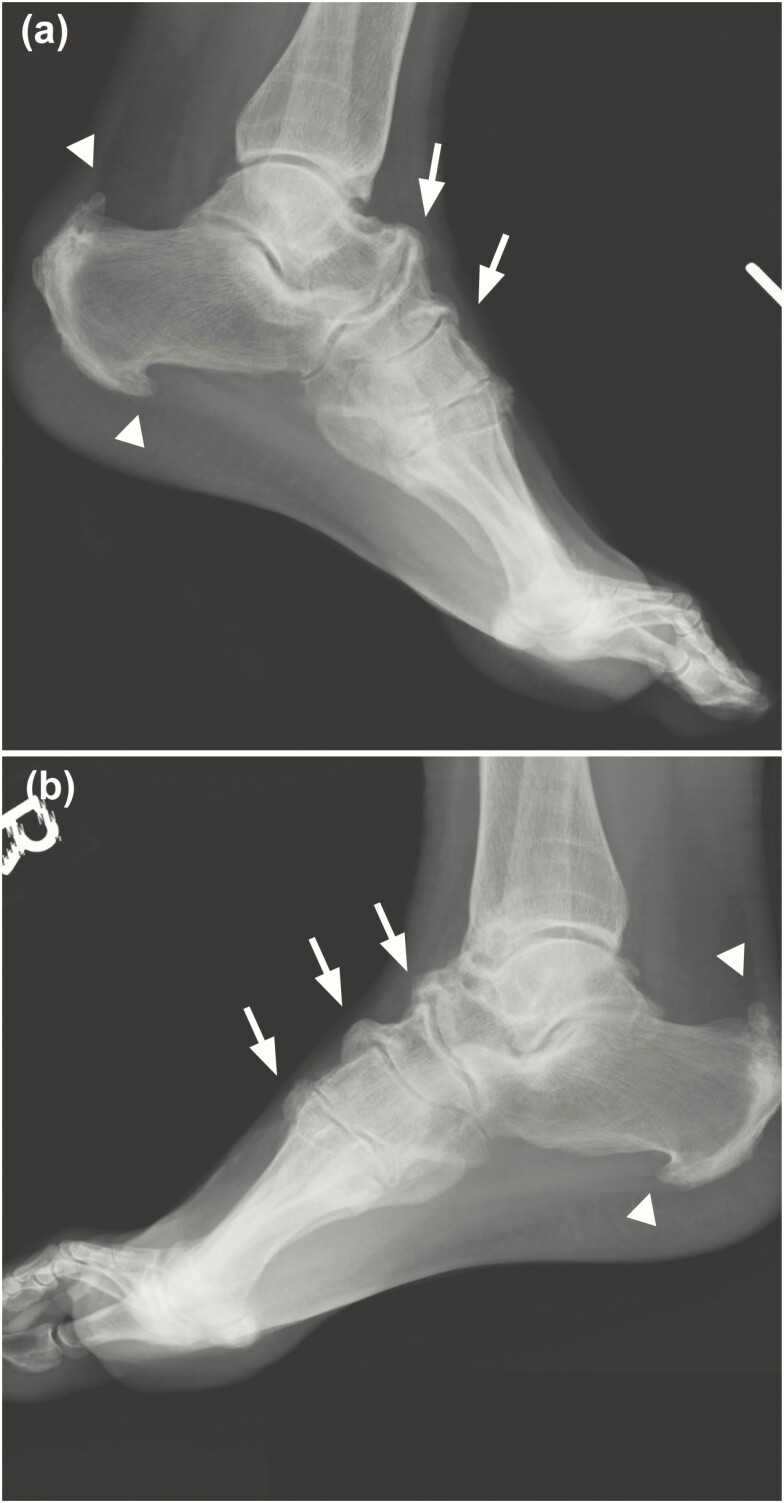

All findings at the ankle and foot were also present bilaterally and consistent between participants (Table 2). Characteristic features included degenerative OA changes at the tibiotalar joint, degeneration of the dome of the talus, and bilateral enthesophyte formation at the posterior and plantar aspects of the calcaneus and the dorsal ligaments of the midfoot (Table 2, Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Radiographic imaging of the feet of a 59-year-old man with X-linked hypophosphatemia, representative of study participants. Growth arrest lines visible on the distal portions of the tibia and lateral A, left and B, right x-rays show prominent symmetrical enthesophyte formation involving the plantar and posterior aspects of calcanei, bilaterally (arrowheads). Enthesophytes present at the talonavicular, cuneonavicular, and metatarsal cuneiform ligaments attachment to the dorsal foot (arrows).

Physical and functional assessment

Passive range of motion.

Passive ROM in the sagittal plane of the cervical spine, hip, knees, and ankles was measured to gain insight into potential functional limitations in light of the radiological findings. Controls had values equivalent to age- and sex-matched reference values for normal joint ROM (33). XLH individuals had decreased passive ROM in the sagittal plane compared to study controls at all sites evaluated. Relative to controls, ROM was found to be significantly lower for cervical spine extension, hip flexion, hip extension, knee flexion, and ankle dorsiflexion (P < .05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Goniometric passive range of motion angles

| Hip, degree | XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Controls (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right; left hip flexion | 101 (19.8); 107 (17.2) | 122 (2.7); 123 (4.5) | .013; .025 |

| Right; left hip extension | 0.89 (10.7); –1.56 (13.8) | 19 (2.2); 19 (5.5) | .001; .002 |

| Right, left hip abduction | 21 (16.5); 16.4 (18.8) | 40 (0.0); 42 (4.9) | .009; .003 |

| Right, left hip adduction | 20 (9.8); 20 (7.2) | 30 (3.5); 32 (4.5) | .020; .003 |

| Right, left hip internal rotation | 14 (12.6); 14 (9.9) | 37 (13.5); 43 (7.6) | .015; .0001 |

| Right, left hip external rotation | 26 (15.4); 22 (14.8) | 40 (7.1); 43 (4.5) | .042; .002 |

| Knee, degree | XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Controls (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P a |

| Right, left knee flexion | 105 (19.9); 97 (22.9) | 138 (2.5); 141 (2.5) | .001; .0004 |

| Right, left knee extension | −13 (12.5); −12.5 (7.5) | 0 (0); 0 (0) | .023; .002 |

| Ankle, degree | XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Controls (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P a |

| Right, left ankle dorsiflexion | −1 (10.9); 0.6 (8.1) | 10 (0); 8 (2.7) | .014; .030 |

| Right, left ankle plantarflexion | 40 (16.7); 48 (13.2) | 49 (8.9); 51 (2.2) | >.05; >.05 |

| Right, left ankle inversion | 4.9 (0.3); 5 (0) | 5 (0); 5 (0) | >.05; >.05 |

| Right, left ankle eversion | 5 (0); 4.8 (0.3) | 5 (0); 5 (0) | >.05; >.05 |

| Spine, degree | XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Controls (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P a |

| Cervical spine flexion | 36 (14.4) | 46 (0) | >.05 |

| Cervical spine extension | 32 (16.4) | 63 (3) | .001 |

| Cervical spine right rotation | 66 (22.8) | 61 (0.1) | >.05 |

| Cervical spine left rotation | 60 (25) | 60 (2.6) | >.05 |

| Cervical spine right flexion | 29 (134) | 36 (0.9) | >.05 |

| Cervical spine left extension | 29 (10.6) | 35 (3) | .010 |

Abbreviation: XLH, X-linked hypophosphatemia.

aDifference between XLH right and left values relative to control right and left values, respectively

Validated, performance-based testing of XLH individuals and controls was used to evaluate any differences in functional ability. Berg Balance scores (BBS) to assess balance in XLH individuals were not significantly different from controls (51.4 ± 3 vs 56 ± 0), respectively. In addition, MMT was performed to evaluate bilateral muscle strength in all 3 anatomical planes of the hip, sagittal plane of the knee, and transverse and sagittal planes of the ankle. There were no significant differences found between XLH participants and controls for muscle strength at any muscle group tested (P = .76). The average MMT for all muscle groups was 4.5 ± 0.36 and 4.97 ± 0.07, respectively. The LEFS questionnaire was also used to assess self-reported lower limb dysfunction for a number of physical activities, with a score of 80 correlating with no loss of function. Relative to controls, individuals with XLH scored significantly lower, with an average of 39.1 ± 17.5 vs 78.5 ± 12.3, respectively, P < .0001.

Gait analysis

Temporal/spatial analysis.

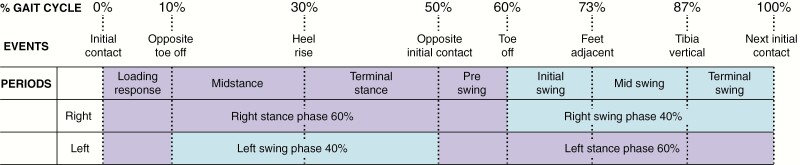

Temporal and spatial data of the gait cycle (Fig. 6) (34) were used to calculate velocity, stride length, step width, and length (Table 4). Kinematic joint angles for controls were consistent with other documented values for age- and sex-matched controls (32), and intrasubject joint variability was also similar between groups. All parameters were significantly lower in individuals with XLH than controls, except for step width, which was significantly larger (P < .05). There were no differences between the XLH and control groups in the percentage of time spent in the stance and swing phases of the gait cycle.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram showing the full gait cycle (reference limb, right side) in the sagittal plane through the stance phase (60%) to swing phase (40%) beginning and ending at right heel contact, constituting 1 complete stride. The stance phase consists of 2 periods of double limb support and 1 period of single support, followed by the swing phase of the same limb. Individual periods: The Stance Phase consists of 4 periods. Initial contact (0% of cycle, right heel) followed by a loading response (0%-10% of cycle) of the right foot, during which the weight of the body is accepted onto the supporting leading limb. Midstance (10%-30% of cycle) begins when the left foot leaves the ground and the body weight moves forward and is aligned over the right foot in contact with the ground (single limb support). Terminal stance (30%-50% of cycle) begins when the left heel leaves the ground until the time the left ipsilateral heel achieves initial contact. During terminal stance, the body weight continues forward and the right heel rises as weight moves over the right forefoot. Preswing (50%-60% of cycle) begins from the time initial contact of the left foot with the ground until the right foot achieves toe off and during which the right limb is rapidly unloaded for advancement. The Swing Phase consists of 3 periods. Initial swing (60%-73% of cycle) is the time from when the right foot leaves and clears the ground and advances forward to align with the contralateral foot. Midswing (73%-87% of cycle) is the time from alignment to the advancement of the right limb. Terminal swing (87%-100% of cycle) occurs from the time the vertically positioned right tibia advances forward and returns to right foot initial contact.

Table 4.

Temporal/spatial gait cycle data

| XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Controls (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity, cm/s | 100 (21) | 140. (14) | .003 |

| Stride length, cm | 109 (8) | 144 (11) | .001 |

| Stride length, right leg, cm | 114 (11) | 144 (11) | .001 |

| Stride length, left leg, cm | 104 (16) | 144 (11) | .001 |

| Step width, cm | 14 (4) | 11 (1) | .001 |

| Step length, cm | 54 (4) | 72 (5) | .042 |

| Velocity, cm/s | 100 (21) | 140 (14) | .001 |

| Stance time, s | 64 (1) | 61 (1) | .080 |

| Swing time, s | 36 (1) | 39 (1) | .076 |

Abbreviation: XLH, X-linked hypophosphatemia.

Angular kinematics and anatomical considerations

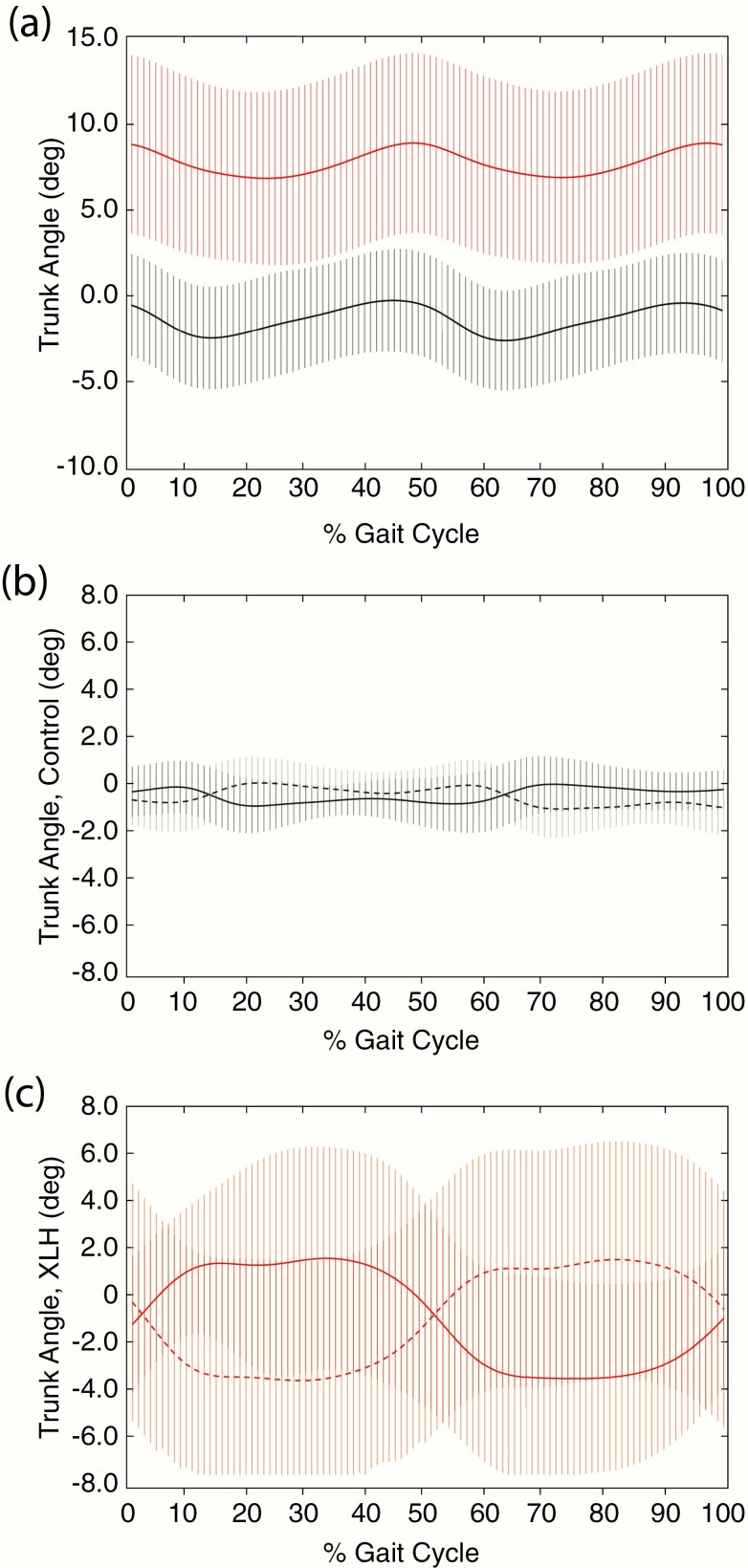

The events and periods of the gait cycle during the stance and swing phases of a full gait cycle are illustrated in Fig. 6 as a reference for angular kinematics (34). Each sagittal joint angle is considered separately unless otherwise specified. Trunk angles normally display 2 small oscillations during gait; this was also confirmed in our study (Fig. 7A) (32, 35, 36). At the trunk, participants with XLH were in a more flexed position over the gait cycle relative to controls, consistent with the significant cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine rigidity secondary to mineralizing enthesophytes and syndesmophytes found in the imaging studies (Table 2). These osseous abnormalities resulted in a fixed, stooped posture at rest that translated into a significant anterior trunk flexion during the entire gait cycle compared to controls (Table 5; Fig. 7A). In addition, compared to controls who had minor fluctuations from neutral (0°), lateral right and left trunk flexion (lateral sway) revealed significantly greater bilateral sway in XLH individuals during the entire gait cycle, except for points of heel contact (Fig. 7B and C), resulting in the descriptive “waddling gait” during ambulation.

Figure 7.

Trunk angles (degrees) during the gait cycle in controls and X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) individuals. Anterior trunk flexion of A, black, controls and A, red, XLH individuals are presented as degrees from erect stance in the sagittal plane. Controls (black), B, mediolateral trunk flexion is presented as degrees from erect stance in the frontal plane to the right (black solid line) and to the left (black dotted line). XLH participants (red), C, mediolateral trunk flexion is presented as degrees from erect stance in the frontal plane, with pronounced right sway (red solid line) and left sway (red dotted line). Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 5.

Summative kinematic trunk angles for XLH individuals and controls, expressed as percentage of gait cycle

| Trunk Flexion/Extension, Degree, Sagittal Plane | Trunk Lateral Right and Left Flexion (Sway), Degree, Frontal Plane | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XLH (n = 9) | Controls (n = 5) | XLH (n = 9) | Controls (n = 5) | |||||

| % Gait Cyclea | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P | Right Mean (SD) | Left Mean (SD) | Right Mean (SD) | Left Mean (SD) | P |

| 0% | 8.7 (5.3) | –0.4 (1.1) | .001 | –1.1 (2.9) | –0.2 (4.4) | –0.3 (1.1) | –0.6 (1.1) | .308 |

| 10% | 7.8 (5.3) | –2.1 (1.1) | .002 | 1.1 (2.7) | –2.8 (4.3) | –0.1 (1.1) | –0.7 (1.3) | .014 |

| 30% | 7.1 (5.1) | –1.4 (2.9) | .005 | 1.6 (4.8) | –3.5 (3.8) | –0.7 (0.8) | –0.1 (1.0) | .001 |

| 50% | 8.7 (5.1) | –0.9 (1.0) | .001 | –0.3 (4.3) | –1.1 (2.6) | –0.7 (1.0) | –0.2 (0.9) | .26 |

| 60% | 7.5 (5.0) | –2.6 (1.3) | .001 | –2.8 (4.1) | 1.1 (2.8) | –0.6 (1.3) | –0.0 (1.1) | .011 |

| 73% | 6.7 (4.8) | –1.9 (1.1) | .002 | –3.4 (4.1) | 1.3 (4.6) | 0.0 (1.1) | –1.0 (1.2) | .001 |

| 87% | 7.9 (5.2) | –0.5 (2.8) | .006 | –3.1 (3.7) | 1.5 (4.7) | –0.2 (0.8) | -0.8 (0.8) | .002 |

| 100% | 8.7 (5.4) | –0.6 (3.0) | .004 | –0.9 (2.9) | –0.5 (4.3) | –0.2 (0.8) | –0.9 (1.2) | .338 |

Abbreviation: XLH, X-linked hypophosphatemia.

aSee Fig. 6 for explanation.

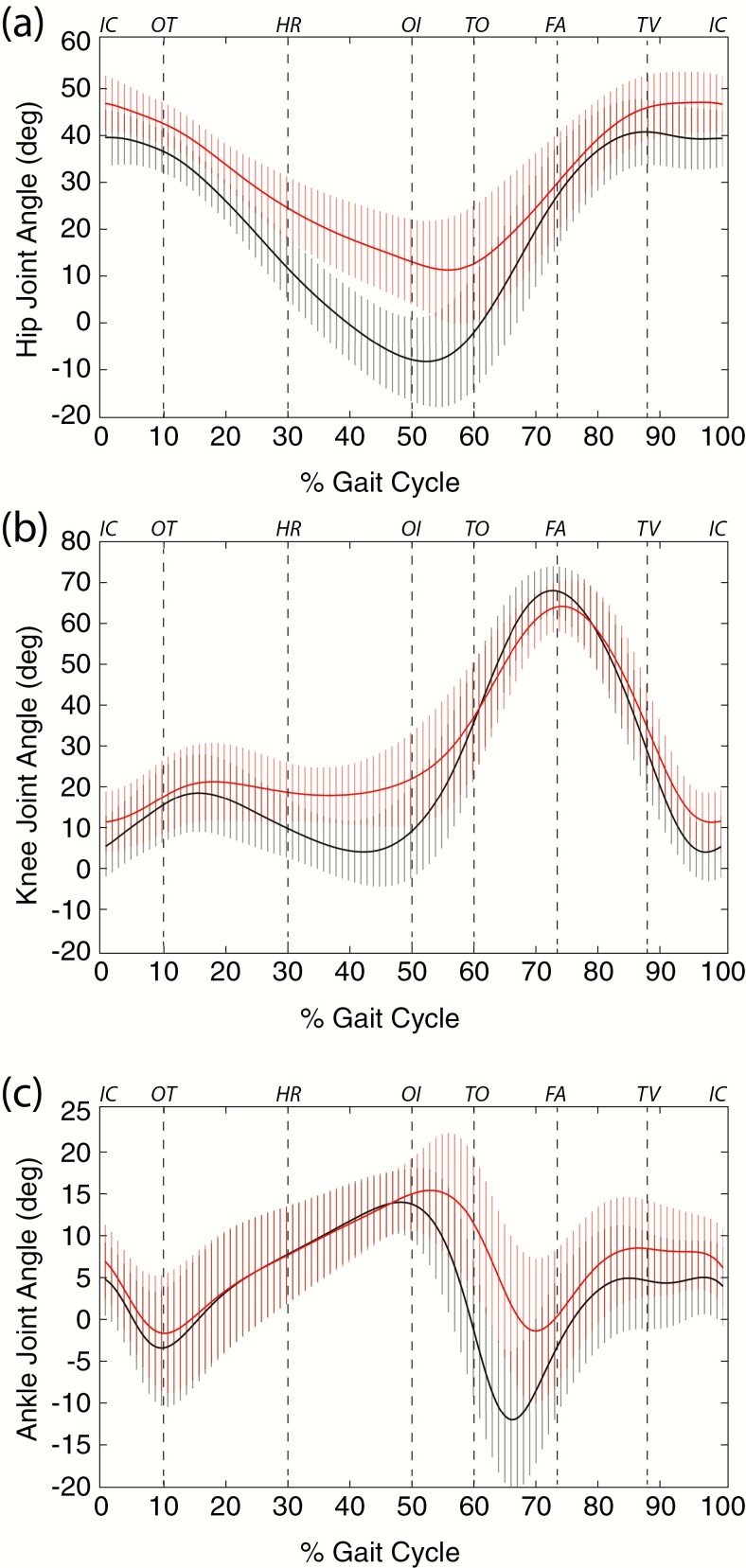

Lower joint angles.

The hip joint supports upper body load and motion is greatest in the sagittal plane during the gait cycle (32). From a position of flexion at initial contact, the hip will normally extend reaching its peak of extension late in stance before flexing again during late stance and swing (32). XLH individuals exhibited less extension during the stance phase of gait, remaining in a more flexed position than controls across the gait cycle (Fig. 8A) (32). Compared to controls, XLH participants never reached a position of hip extension during late stance (Fig. 8A). The hip joint should be in an extended position during this phase of the gait cycle. This inability to extend the hip joint is consistent with the significant physical restriction of hip extension ROM noted in XLH individuals (Table 3). Consequently, XLH participants were limited to a smaller amount of extension to achieve step advancement during late stance–early swing when weight is transferred to the contralateral limb resulting in a shorter stride length (Table 4). The hip was also the only lower extremity joint to show significant differences both in the coronal and transverse plane ROM relative to controls. Bilateral hip abduction, adduction, and internal and external rotation ROM were significantly lower than controls (Table 6).

Figure 8.

Sagittal plane joint angles (degrees) during a single gait cycle in controls (black) and X-linked hypophosphatemia individuals (red). Joint angles of A, hips, B, knee, and C, ankle, are reported as degrees across the gait cycle using the right side as reference, although findings were consistently bilateral (Fig. 6). Events at the top of the plots are added as a visual guide for comparison to Fig. 6: FA, feet adjacent; HR, heel rise; IC, initial contact; OI, opposite initial contact; OT, opposite toe off; TO, toe off; TV, tibia vertical. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 6.

Hip range of motion angles (maximum – minimum], coronal and transverse planes

| Movement, degree | XLH (n = 9) Mean (SD) | Con (n = 5) Mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right hip abduction | 8.11 (2.46) | 12.10 (3.84) | .034 |

| Left hip abduction | 8.28 (2.83) | 12.87 (3.46) | .020 |

| Right hip rotation | 8.66 (3.62) | 12.64 (1.13) | .032 |

| Left hip rotation | 7.82 (1.61) | 11.63 (2.56) | .004 |

Abbreviation: XLH, X-linked hypophosphatemia.

The primary movements of flexion and extension at the knee during gait facilitates toe clearance and prepares for foot placement during the swing phase (32). Participants with XLH were in a more flexed knee position at initial contact than the controls and remained more flexed throughout the stance phase of gait (Fig. 8B). The discrepancy between XLH and control individuals was greatest during midstance, where controls had achieved a fully extended knee as compared to the flexed knee position of the XLH participants (Fig. 8B). In XLH individuals, as with the hip, the inability to achieve an extended position is consistent with the significant physical restriction of knee extension noted during passive ROM testing and imaging studies (Table 3; Fig. 4). During the midswing phase of the gait cycle, both groups achieved a near typical peak knee flexion of 60°, with the XLH participants exhibiting slightly less knee flexion than controls (Fig. 8B).

Ankle ROM occurs primarily in the sagittal plane in humans, predominantly at the tibiotalar joint (32, 37). Between experimental groups, the ankle (Fig. 8C) plantar-flexed to a similar degree from initial heel contact through loading response. Once the foot assumed single-limb support and transitioned into midstance, XLH participants achieved similar maximum ankle dorsiflexion into the end of terminal stance (50% of gait cycle) relative to controls. From terminal stance into preswing, the ankle actively plantar-flexed greater than 10° in controls, whereas XLH individuals achieved less than half this value; restricted plantar flexion continued into the swing phase in the XLH group. The ankle then achieved near-neutral dorsiflexion during midswing and was maintained into terminal-swing in both groups.

Discussion

Detailed evaluation of radiographic images, ROM, and gait assessments allow a more comprehensive understanding of the functional limitations present in adults with XLH and can serve as an evidence-based approach to the management of adults with XLH. We present the first study in the adult XLH population aimed at reconciling reports of the progressive physical manifestations of the disease with the functional impact of these bony changes. Despite the small number of individuals enrolled in this study, there was a remarkable homogeneity in our findings, which were consistent with a recent, detailed self-reported assessment of physical findings and abilities in 232 adults with XLH within the same age range as our study (13).

In the general aging population, degenerative OA with marginal joint osteophytes is a leading cause of pain and physical disability (38). In addition, mineralizing enthesophytes severely limit physical activity and cause pain (39). Both were documented as pervasive and severe comorbidities of the disorder in the upper and lower body and should therefore be considered as major factors in the limitations both of passive and active ROM recorded in individuals with XLH.

In the upper extremity, these findings provided a functional profile unique to individuals with XLH and translated into limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) (21). Advanced arthritic changes at the glenohumeral joint, the primary contributor to shoulder movement and load-bearing, were present in majority of XLH individuals. Enthesophytes were also prevalent at the acromioclavicular joint of the shoulder complex. Together with glenohumeral joint OA, limited ROM and pain will restrict the completion of ADL such as work and household activities (40).

At the elbow, all XLH participants had enthesophytes at the olecranon process, the attachment site of the triceps brachii tendon. This compromises the ability to rotate the shoulder and extend the arm while engaging in daily tasks and restricts the ability to use this motion to break a falling incident. This is especially important when taken in context of our related study, which identified a significant fear of falling in this population; itself, a fall risk (21). Humeroradial joint degeneration and marginal osteophytes was also dominant in this population. The humeroradial articulation will largely affect flexion and extension of the elbow within the range of a variety of essential ADL that include reaching, eating, and drinking activities (41). Radial head rotation of this same joint is involved in supination and pronation of the hand in space. Supination affects activities such as opening doors and perineal care that, together with the many activities requiring shoulder and arm dexterity, would benefit from consultation with an occupational therapist who can assess the work and home environment and advise on the use of adaptive equipment and treatment goals (21).

OA at the thumb base and the proximal interphalangeal joints often coincide and are major causes of hand joint pain in the elderly population (42). Presentation of the wrist and hand included degenerative arthritis with osteophytes in the proximal and distal phalanges and in the trapeziometacarpal joint in XLH individuals. Because these changes are occurring earlier in life in adults with XLH, interventions are needed in advance to adapt to ADL such as cooking, dressing, and driving (21). Osteophytes at the joint margins are thought to stabilize joints that have undergone degenerative changes, consistent with a strong correlation coefficient between OA severity and osteophyte presentation (43). Osteophytes at the trapezium-metacarpophalangeal joint align with the prevalence of both findings at this joint. Enthesophytes of the hand due to overuse have been largely been attributed to aging, with a smaller genetic component in the general population (44). Enthesopathy patterns were less consistent within the hand and wrist of XLH participants and may be related to the extent of physical activity or to the underlying disorder, but still occur earlier than the general aging population (10).

Evaluation of the trunk and lower extremities also revealed severe degenerative OA, osteophytes, and mineralizing enthesophytes that involved the spine, hip, and knee and ankle joints. These data aligned with the finding that individuals with XLH scored more than 50% below the maximum score on the LEFS functional scale, with the 2 lowest scores reported at 11 and 18 and a highest single patient score of 61, underscoring the significant physical disability of this population (13). Imaging data of the spine were consistent with spinal rigidity, kyphosis, and straightening of the normal lumbar lordosis due to marginal syndesmophytes and enthesophytes. Apparent fusion of the vertebral bodies secondary to enthesophyte formation, resulted in a “bamboo spine” phenotype across all XLH individuals, like that observed in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Individuals with spinal deformities experience pain, lower self-image, and compromised mental health, worsening with increased age (45). Profuse enthesophyte formation along the spinal ligaments will also restrict functional ability, as evidenced by decreased cervical spine ROM observed in this study. Importantly, physical restriction of the spine and spinal deformities can alter the center of mass and affect posture, contributing to a cautious gait and to fall risk (46).

Gait, or ambulation, is a critical ADL, and assessment of this activity provides important clues to the underlying cause and impact of a pathological condition on an individual. The gait pattern of XLH has often been described as a “waddling gait,” a gait associated with limited hip and knee movement and an inability to clear the foot during the swing phase (47). However, no studies have been conducted to understand the nature of this descriptor that has been applied to XLH. This is the first report of the joint angular kinematics of the hips, knees, ankles, and trunk during the gait cycle in individuals with XLH. Indeed, despite the small number of XLH participants, the gait pattern was found to be strikingly similar, consistent with the similarly comparable skeletal and extraskeletal findings reported here.

Data obtained from the temporospatial and kinematic analysis of gait in XLH individuals were found to differ from controls. XLH adults demonstrated decreased velocity, shorter stride, step length, and increased step width, and although it did not reach significance, XLH participants exhibited a trend toward prolonged stance time. We considered the alteration of these parameters a potential consequence of the abnormal findings at the trunk, hip, knee, and ankle that became apparent with analysis of the gait cycle (24).

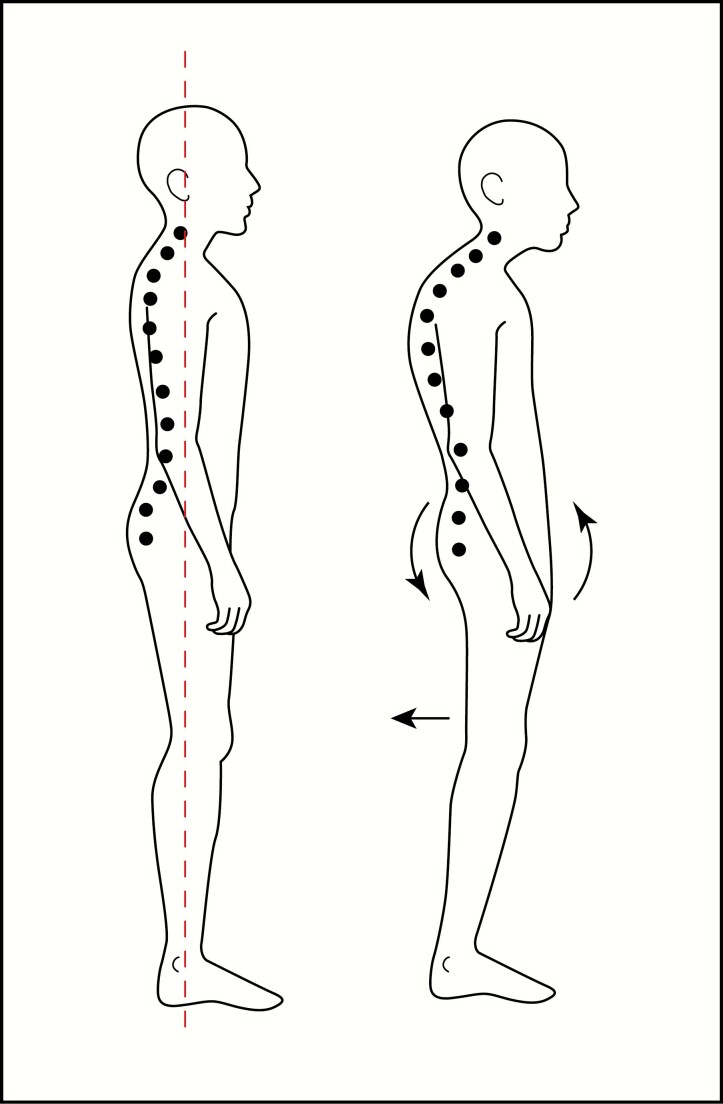

XLH participants exhibited significant deviation from controls in their trunk kinematics that persisted throughout the entire gait cycle. This finding provided insight into the overall gait pattern uniformly displayed by individuals with XLH. Changes in truck kinematics can arise because of osseous abnormalities in the spine, pelvis, and lower limbs. Spinal deformities seen in our participants with XLH included scoliosis and kyphosis and a spinal ligamentous mineralizing enthesopathy that imposed a fixed, stooped posture and may have also correlated with an attempt to relieve painful lumbar compression. The spinal phenotype due to longitudinal ligamentous calcification is similar to AS, a disorder for which a majority of gait abnormalities, comparable to our study, were found to occur in the sagittal plane (48). Interestingly, spinal rigidity in AS was found to result in ambulatory compensations that included posterior pelvic tilt. Likewise, we observed a compensatory posture so that XLH individuals could achieve a more vertical gaze during ambulation, typical of a “swayback” posture and characterized by diminished lumbar spine lordosis and posterior pelvic tilt (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Illustration showing the conventional standing position posture and center of gravity alignment (left), compared to posture assumed by X-linked hypophosphatemia individuals (right) to initiate the gait cycle, to achieve a vertical gaze during ambulation. The posture presents with diminished lumbar spine lordosis and posterior pelvic tilt assumed secondary to significant restriction of the cervical spine and forward flexed posture, structural spinal kyphosis, and spinal mineralizing enthesopathy.

Anatomical restriction of the hip affects upper body movement and trunk sway (49). The trunk sway present in XLH individuals was comparable to the Trendelenburg sign of lateral trunk shift secondary to pelvic drop. This is visualized as a trunk sway (or waddling gait) when the contralateral hip of the weight-bearing side drops or fails to stay level during single-leg weight bearing at midstance. Here, the pathology correlates with radiological evidence of bilateral enthesophytes at the origin and insertion of the hip abductors (gluteus medius and minimus), at the iliac crest and greater trochanter, respectively.

Deformities of the hip joint also manifested as acetabular spurring, femoral head and neck deformities, and significant joint space reduction. The hip in participants with XLH had anatomical restriction of extension and flexion both in the active and passive ROM and throughout the gait cycle due to enthesophytes in all individuals at the lesser trochanter, into which the iliopsoas and psoas major muscles insert. The rigidity of the insertion into the lesser trochanter may decrease force production of flexion and may lead to the restricted hip extension, as measured in passive ROM. In addition, there was a prevalence of mineralizing enthesophytes at the origin of the insertion of the hamstring muscles into the ischial tuberosity, attachment sites of the primary hip extensors, the gluteus maximus, and the hamstrings. Considering the functional consequence of calcification at this site, the evidence clearly showed significant restriction of hip extension.

Further, the primary hip extensors function to stabilize the leg for weight-bearing during single limb support. Although calcification of the hip extensors insertion site is a rarely reported event in the general population, proximal hamstring tendinopathies commonly present with lower gluteal pain, so that pain of calcification likely limits the ability of the hamstrings to eccentrically lengthen in the terminal swing phase (50). These findings are consistent with the significantly lower stride and step lengths measured in XLH individuals. In addition, the severity of OA and acetabular spurring of the hip joint identified in these studies will exacerbate pain and ROM. Even mild-to-moderate OA has been shown to alter spatiotemporal gait parameters and gait in the sagittal plane, primarily affecting hip extension and flexion ROM (51). An additional finding by Eitzen et al was an impact on hip extensor moments, without evidence of muscle weakness (51). This is most consistent with under-utilization of hip extensor muscles during gait, a finding that should be considered in the context of our similar observations.

When evaluating the knee throughout the gait cycle, the degree of extension is constitutively compromised in XLH relative to controls. Calcification of the quadriceps and patellar insertions into the superior and inferior aspects of the patella and loss of retropatellar spacing likely contribute to functional and painful restriction of joint angles. Degenerative joint disease and loss of extracellular matrix would also significantly contribute to the painful limitation in the ROM across the synovial joint and decreased ability to accommodate compressive forces during single- and double-limb support. Full extension of the knee at midstance early in the progression of the disease would additionally cause an increased impact load and stress to the joint in this population, which may be a significant contributor to the early progression of degenerative OA observed at the tibiofemoral joint (52).

Physical findings of the ankle and foot were consistent across XLH participants. The movement of the tibiotalar ankle joint is necessary for limb advancement and toe clearance. Talar dome flattening and osteophytic spurring at the anterior aspect of the tibiotalar joint can contribute to restricted passive ankle dorsiflexion ROM in XLH. In addition, enthesophytes of the posterior calcaneus, attachment site of the Achilles tendon, was found globally in all participants and is one of the most common documented in XLH (10). Calcification of the Achilles insertion causes rigidity and pain on dorsiflexion and likely influences the execution of plantar flexion, illustrated by the inability of XLH individuals to achieve maximal plantar flexion during preswing. This suggests that, although a wider joint range can be obtained by applied force, the Achilles insertion enthesopathy imposes a physical restriction on plantar flexion during this stage of the gait cycle. This is further supported by significantly shortened stride length, a wider stance and prima facie evidence of the waddling gait previously applied as a descriptor for this population. Lacking full plantar flexion along with a sway gate and wider step length may enable toe clearance. Toe clearance can also be achieved by increased hip abduction but was not employed in this population during gait because of the observed very limited hip abduction ROM.

The foot is largely responsible for shock absorption, stability, and gait propulsion. Compromised dorsal ligaments and calcification of the plantar aspects of the calcaneus decrease the adaptivity of the tarsal and metatarsal joints and muscles to weight acceptance (53). In addition, talonavicular ligament mineralization was observed in a majority of the participants. Although the angle of the phalanges was not analyzed, the talonavicular ligament at the apex of the dorsal aspect of the foot is subjected to maximal tensile forces as the toes dorsiflex and the plantar fascia tightens during the push-off phase of walking (54). Mineralization of this ligament limits elasticity and, together with plantar fascial insertion enthesophytes, would be expected to limit gait velocity by decreasing the ability to generate the forces required for the propulsive phase of gait.

Finally, while we have considered the functional impact on ROM, muscles provide the power needed to ambulate and are affected by the inability to attain maximal joint angles needed to generate force. Although static manual muscle testing of the major muscle groups revealed no significant differences between control and XLH individuals, the contributions of muscle fatigue on many of these findings cannot be completely ruled out. However, the distance and time elapsed for kinematic studies were very short and unlikely to elicit muscle fatigue. Future studies aimed at evaluating ground reaction forces during gait will help illuminate the impact of this biomechanical parameter. Nonetheless, because cellular adenosine triphosphate production may be compromised by the metabolic disturbance of familial phosphate wasting (55), sustained activity, as occurs during ADL, can exacerbate the impact that the bony changes have on the musculoskeletal system. This should be considered in the patient assessment and muscle fatigue evaluated with standardized tests such as the 6-minute walk test, shown to be compromised in adults with XLH (20).

Another important consideration in patient assessment is balance. BBS in this study, in isolation, indicate a low fall risk (26). However, individual BBS, when paired with fall history, are more predictive of fall risk and should be considered using revised algorithms (56) and other risks identified in this population, most significantly, fear of falling (21, 57). In addition, relative to the aging population, individuals with XLH are prone to fractures both at prototypical and atypical sites secondary to persistent osteomalacia (47). Radiological evidence presented here reveals unambiguous evidence of such fracture/pseudofracture in all patients. Although 5 of 9 patients self-reported prior fractures (Table 1), most striking in this study were the identification of fractures that were not previously reported or treated. Given the pain associated with the musculoskeletal manifestations described in this study, it is noteworthy that a painful event is not consistently interpreted as a potential fracture (21). Together with fracture history, gait findings consistent with an altered center of mass, and widened base of support, adults with XLH would benefit greatly from an environmental assessment and identification of fall risks in the home, social, and work environments using tool kits such as the STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries) initiative (58). This is crucial to avoiding risk of injury and fracture and will help to minimize the numbers of surgical interventions required, including intramedullary and extramedullary fixations.

The present study is not without limitations. With a small sample size of 9 individuals, only large differences are likely to be detected, but this is not unreasonable considering the documented musculoskeletal comorbidities of the study population relative to age- and sex-matched controls (13). Although some radiological findings were less frequently observed in the upper and lower extremities, a larger study may show greater prevalence of these findings or they may become apparent in currently unaffected individuals as part of the natural progression of the disorder. In addition, individuals with severe disabilities related to ambulation were excluded, so our findings may underestimate the musculoskeletal severity or number of sites affected in individuals with a more progressed phenotype. Owing to variability in gait technology, future studies would benefit from a patient case-series study to monitor the progression of XLH and its impact on gait over the life course. Although many of the comorbidities reported here have been shown to be resistant to therapy, treatment history in this cohort was not consistent and may have variably affected individual findings. Nonetheless, the consistent radiographical and functional findings in this study support the belief that conventional therapies and/or frequency would have had little impact. However, relative to intermittent traditional therapies used in adulthood that are limited by their toxicities, earlier and long-term interventions with newer therapies like burosumab aimed at targeting FGF23, already associated with favorable self-reported outcomes in adults (19), may significantly slow the progression of the musculoskeletal comorbidities of this disorder and offer promise to future generations of adults with XLH.

Conclusion

Our findings illustrate that adults with XLH present with significant bilateral functional limitations attributable to advanced and pervasive musculoskeletal findings affecting tissues that have an inherently poor healing capacity. Importantly, these findings provide incontrovertible evidence that supports the necessity for the creation of an interprofessional health-care team with the goal of establishing a longitudinal plan of care that considers disease manifestations across the lifespan. In addition to the primary care provider, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and social workers are critical to help navigate the health-care system and challenges unique to adults with XLH. This includes pain management to improve physical function and quality of life, assessment of both the extrinsic and intrinsic fall risk factors, adaptive equipment for ADL to address physical limitations, and evaluation of behavioral health and well-being. In addition, these interventions inform the need for orthotic footwear, the use of validated tests to measure the progression of the disorder over time, as well as efficacy of physical therapy and treatment, and orthopedic interventions and prosthesis design (59). Future goals of these studies involve the creation of evidence-based physical therapy interventions aimed at addressing the major clinical findings in this study to improve quality of life and increase functional independence. In conclusion, these recommendations expand on current guidelines established for children and adolescents with XLH to include essential care for the adult population (6).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Edward Rosenblatt and Nora Kinslow for their excellent review of the data. We are indebted to the individuals who volunteered for this study to further the understanding of rare metabolic bone disorders.

Financial Support: This work was supported by a grant from Global Genes.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- LEFS

Lower Extremity Functional Scale

- OA

osteoarthritis

- PHEX

phosphate-regulating gene with homology to endopeptidases on the X chromosome

- ROM

range of motion

- XLH

X-linked hypophosphatemia

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Carpenter TO. New perspectives on the biology and treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44(2):443–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endo I, Fukumoto S, Ozono K, et al. Nationwide survey of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)-related hypophosphatemic diseases in Japan: prevalence, biochemical data and treatment. Endocr J. 2015;62(9):811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck-Nielsen SS, Brock-Jacobsen B, Gram J, Brixen K, Jensen TK. Incidence and prevalence of nutritional and hereditary rickets in southern Denmark. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160(3):491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macica CM. Overview of phosphorus-wasting diseases and need for phosphorus supplements. In: Uribarri J, Calvo MS, eds. Dietary Phosphorus: Health, Nutrition, and Regulatory Aspects. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis F, Hennig S, Korn B, et al. A gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. The HYP Consortium. Nat Genet. 1995;11:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter TO, Imel EA, Holm IA, Jan de Beur SM, Insogna KL. A clinician’s guide to X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1381–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis F, Strom TM, Hennig S, et al. Genomic organization of the human PEX gene mutated in X-linked dominant hypophosphatemic rickets. Genome Res. 1997;7(6):573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe PS, Oudet CL, Francis F, et al. Distribution of mutations in the PEX gene in families with X-linked hypophosphataemic rickets (HYP). Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(4):539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, et al. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(3):429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang G, Katz LD, Insogna KL, Carpenter TO, Macica CM. Survey of the enthesopathy of X-linked hypophosphatemia and its characterization in Hyp mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;85(3):235–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang G, Vanhouten J, Macica CM. An atypical degenerative osteoarthropathy in Hyp mice is characterized by a loss in the mineralized zone of articular cartilage. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89(2):151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cremonesi I, Nucci C, D’Alessandro G, Alkhamis N, Marchionni S, Piana G. X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets: enamel abnormalities and oral clinical findings. Scanning. 2014;36(4):456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skrinar A, Dvorak-Ewell M, Evins A, et al. The lifelong impact of X-linked hypophosphatemia: results from a burden of disease survey. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(7):1321–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linglart A, Biosse-Duplan M, Briot K, et al. Therapeutic management of hypophosphatemic rickets from infancy to adulthood. Endocr Connect. 2014;3(1):R13–R30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verge CF, Lam A, Simpson JM, Cowell CT, Howard NJ, Silink M. Effects of therapy in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(26):1843–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter TO, Whyte MP, Imel EA, et al. Burosumab therapy in children with X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1987–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imel EA, Glorieux FH, Whyte MP, et al. Burosumab versus conventional therapy in children with X-linked hypophosphataemia: a randomised, active-controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2416–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Insogna KL, Briot K, Imel EA, et al. ; AXLES 1 Investigators . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial evaluating the efficacy of burosumab, an anti-FGF23 antibody, in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia: week 24 primary analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(8):1383–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insogna KL, Rauch F, Kamenický P, et al. Burosumab improved histomorphometric measures of osteomalacia in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia: a phase 3, single-arm, international trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34(12):2183–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portale AA, Carpenter TO, Brandi ML, et al. Continued beneficial effects of burosumab in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia: results from a 24-week treatment continuation period after a 24-week double-blind placebo-controlled period. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019;105(3):271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes MM, Macica CM, Meriano C, Doyle M. Giving credence to the experience of X-linked hypophosphatemia in adulthood: an interprofessional mixed-method study. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2019;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glorieux FH, Marie PJ, Pettifor JM, Delvin EE. Bone response to phosphate salts, ergocalciferol, and calcitriol in hypophosphatemic vitamin D–resistant rickets. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(18):1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan W, Carpenter T, Glorieux F, Travers R, Insogna K. A prospective trial of phosphate and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 therapy in symptomatic adults with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75(3):879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karaplis AC, Bai X, Falet JP, Macica CM. Mineralizing enthesopathy is a common feature of renal phosphate-wasting disorders attributed to FGF23 and is exacerbated by standard therapy in hyp mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153(12):5906–5917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(9):646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health. 1992;83(Suppl 2):S7–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadsworth CT, Krishnan R, Sear M, Harrold J, Nielsen DH. Intrarater reliability of manual muscle testing and hand-held dynametric muscle testing. Phys Ther. 1987;67(9):1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuthbert SC, Goodheart GJ Jr. On the reliability and validity of manual muscle testing: a literature review. Chiropr Osteopat. 2007;15:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weaver LJ, Ferg AL.. Therapeutic Measurement and Testing: The Basics of ROM, MMT, Posture, and Gait Analysis. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Cengage Learning;2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther. 1999;79(4):371–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter D, Reidinger K, Szymialowicz R, et al. Sidestep and crossover lower limb kinematics during a prolonged sport-like agility test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(5):617–627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry J, Burnfield JM.. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function. 2nd ed. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soucie JM, Wang C, Forsyth A, et al. ; Hemophilia Treatment Center Network . Range of motion measurements: reference values and a database for comparison studies. Haemophilia. 2011;17(3):500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muybridge E.Muybridge’s Complete Human and Animal Locomotion: All 781 Plates from the 1887 Animal Locomotion. New York: Dover Publications;1979. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krebs DE, Wong D, Jevsevar D, Riley PO, Hodge WA. Trunk kinematics during locomotor activities. Phys Ther. 1992;72(7):505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sartor C, Alderink G, Greenwald H, Elders L. Critical kinematic events occurring in the trunk during walking. Hum Movement Sci. 1999;18(5):669–679. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimston SK, Nigg BM, Hanley DA, Engsberg JR. Differences in ankle joint complex range of motion as a function of age. Foot Ankle. 1993;14(4):215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(9):1145–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegal DS, Wu JS, Newman JS, Del Cura JL, Hochman MG. Calcific tendinitis: a pictorial review. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2009;60(5):263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruttel H, Spranz DM, Bülhoff M, Aljohani N, Wolf SI, Maier MW. Comparison of glenohumeral and humerothoracical range of motion in healthy controls, osteoarthritic patients and patients after total shoulder arthroplasty performing different activities of daily living. Gait Posture. 2019;71:20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gates DH, Walters LS, Cowley J, Wilken JM, Resnik L. Range of motion requirements for upper-limb activities of daily living. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70:7001350010p7001350011–7001350010p7001350010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahaghin S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Ginai AZ, Pols HA, Hazes JM, Koes BW. Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):682–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Kraan PM, van den Berg WB. Osteophytes: relevance and biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(3):237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalichman L, Malkin I, Kobyliansky E. Hand bone midshaft enthesophytes: the influence of age, sex, and heritability. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(10):1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daniels AH, Smith JS, Hiratzka J, et al. ; International Spine Study Group (ISSG) . Functional limitations due to lumbar stiffness in adults with and without spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(20):1599–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crosbie J, Vachalathiti R, Smith R. Patterns of spinal motion during walking. Gait Posture. 1997;5:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Che H, Roux C, Etcheto A, et al. Impaired quality of life in adults with X-linked hypophosphatemia and skeletal symptoms. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(3):325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Del Din S, Carraro E, Sawacha Z, et al. Impaired gait in ankylosing spondylitis. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2011;49(7): 801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer CA, Corten K, Fieuws S, et al. Biomechanical gait features associated with hip osteoarthritis: towards a better definition of clinical hallmarks. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(10):1498–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lempainen L, Johansson K, Banke IJ, et al. Expert opinion: diagnosis and treatment of proximal hamstring tendinopathy. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2015;5(1):23–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eitzen I, Fernandes L, Nordsletten L, Risberg MA. Sagittal plane gait characteristics in hip osteoarthritis patients with mild to moderate symptoms compared to healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moyer RF, Ratneswaran A, Beier F, Birmingham TB. Osteoarthritis year in review 2014: mechanics—basic and clinical studies in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(12):1989–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nordin M, Frankel VH.. Basic Biomechanics of the Musculoskeletal System. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Dea M, Constantinos LL, Allen GM, et al. Talonavicular ligament: prevalence of injury in ankle sprains, histological analysis and hypothesis of its biomechanical function. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1071):20160816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pesta DH, Tsirigotis DN, Befroy DE, et al. Hypophosphatemia promotes lower rates of muscle ATP synthesis. FASEB J. 2016;30(10):3378–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shumway-Cook A, Baldwin M, Polissar NL, Gruber W. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults. Phys Ther. 1997;77(8):812–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lusardi MM, Fritz S, Middleton A, et al. Determining risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis using posttest probability. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2017;40(1):1–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarmiento K, Lee R. STEADI: CDC’s approach to make older adult fall prevention part of every primary care practice. J Safety Res. 2017;63:105–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills ES, Iorio L, Feinn RS, Duignan KM, Macica CM. Joint replacement in X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Orthop. 2019;16(1):55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]