Abstract

Background

Undertaking research and attaining informed consent can be challenging when there is political unrest and community mistrust. Rapid ethical appraisal (REA) is a tool that uses qualitative methods to explore sociocultural issues that may affect the ethical conduct of research.

Methods

We used REA in northeast Ethiopia shortly following a period of unrest, during which violence against researchers occurred, to assess stakeholder perceptions of research, researchers and the informed consent process. We held 32 in-depth interviews and 2 focus group discussions.

Results

Most community members had little awareness about podoconiosis or healthcare research. Convincing the community to donate blood for research is challenging due to association with HIV testing. The attack on researchers was mainly motivated by the community's mistrust of their intentions against the background of a volatile political situation. Social media contributed to the spread of misinformation. Lack of community engagement was also a key contributing factor.

Conclusions

Using REA, we identified potential barriers to the informed consent process, participant recruitment for data and specimen collection and the smooth conduct of research. Researchers should assess existing conditions in the study area and engage with the community to increase awareness prior to commencing their research activities.

Keywords: informed consent, northeast Ethiopia, podoconiosis, rapid ethical appraisal, social instability

Introduction

Informed consent is a fundamental ethics principle when undertaking biomedical research. However, the practice of attaining informed consent can be challenging, especially in lower and middle income countries (LMICs).1 Common reasons for this include poor comprehension of research concepts, whereby participants fail to differentiate research from basic healthcare and diagnosis.2 The situation can be further complicated when researchers try to adapt guidelines written for developed countries without regard for the local diverse sociocultural, religious and economic contexts in which the research is conducted.3,4 This creates barriers to informed consent that need to be understood before the research is undertaken so that adaptations can be made to the process. Such adaptations might include simplification of information sheets and ensuring that trusted community members are part of the process.

Rapid ethical appraisal (REA) is a tool that has been applied successfully to facilitate the identification of potential barriers and enablers within the context of specific research projects and local cultural sensitivities. It uses different methods like interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and observations to collect data.5,6 REA has been reported to be an effective tool to improve the quality of the informed consent process in a low resource setting and as essential for conducting ethical research on human participants.7,8

Our group has a programme of work investigating the molecular aetiology of podoconiosis, a neglected tropical disease that causes lymphoedema, which results from the exposure of bare feet to a particular type of soil in genetically susceptible individuals.9 This requires the collection of biological samples, which can add another layer to the ethical complexities of undertaking research in such settings.9 Studies to map the genes involved in podoconiosis have been undertaken in Ethiopia and Cameroon and we have identified an association between variation in class II HLA genes, indicating that there was an immune basis to podoconiosis which we wished to investigate further. We used REA to explore aspects of informed consent prior to undertaking the gene-mapping studies.10,11 The REA study by Tariku et al. was conducted in the same region in northeast Ethiopia where we proposed to carry out the podoconiosis immunology study. Key findings that influenced recruitment included the study participants’ inability to differentiate research from clinical diagnosis, the need to approach potential study subjects with trusted community members, gender and the type of biological sample sought.11 However, while this information could help shape consent-gathering for the immunology research, the first study had been conducted >5 y ago and there were differences around study design and sample collection that warranted further exploration within the community before research could begin. For example, exploration of the community’s understanding of genetics and genetics research was not so relevant for the immunology studies, and saliva samples were collected when more invasive blood and skin biopsy samples were required for the immunology studies. Also, although Tariku et al.’s study was conducted in the same region of Ethiopia, we would be working with different communities.

Additionally, in the time since the first REA study was conducted,9 there had been community unrest in the study area around Bahir Dar, the capital of the Amhara regional state in northeast Ethiopia, in the months before our study was due to start. Vehicles from a national research institute were vandalised while researchers were collecting blood from young women to study the prevalence of HIV in Bahir Dar.12 A few months later, two researchers from a different research institute working on sanitation and health in elementary school children were stoned to death and a third critically injured at Addis Alem, a few km away from Bahir Dar.12 The incidents took place amidst social and political unrest in the country and was mainly driven by youth protests in the Oromia and Amhara regions that later forced the ruling party to a political transition. The transition led to a sense of freedom that, however, sometimes led to social unrest and mob attacks in different parts of the country.13

Researchers were attacked and their property was damaged because of mistrust in the health system in general that included rumours about the researchers’ activities having a negative impact on society. This suggested there was misunderstanding in the community regarding medical research activities leading to mistrust that could negatively impact other projects. Researchers and healthcare workers have been subjected to different challenges and abuse in politically unstable or disaster-hit areas. More than 4 frontline healthcare workers were killed and 12 injured in two locations in the Democratic Republic of Congo during the 2018–2019 Ebola epidemic, which led to the withdrawal of healthcare workers from the area.14 Similarly, researchers from the University of California15 and Brazil16 have been attacked or had their property vandalised in relation to their research activities.

We, therefore, undertook an REA study prior to the immunology study to better understand these concerns and to allow them to shape how we undertook the research in an open and transparent way, with the trust of the community and with full informed consent.

Methodology

Study area and period

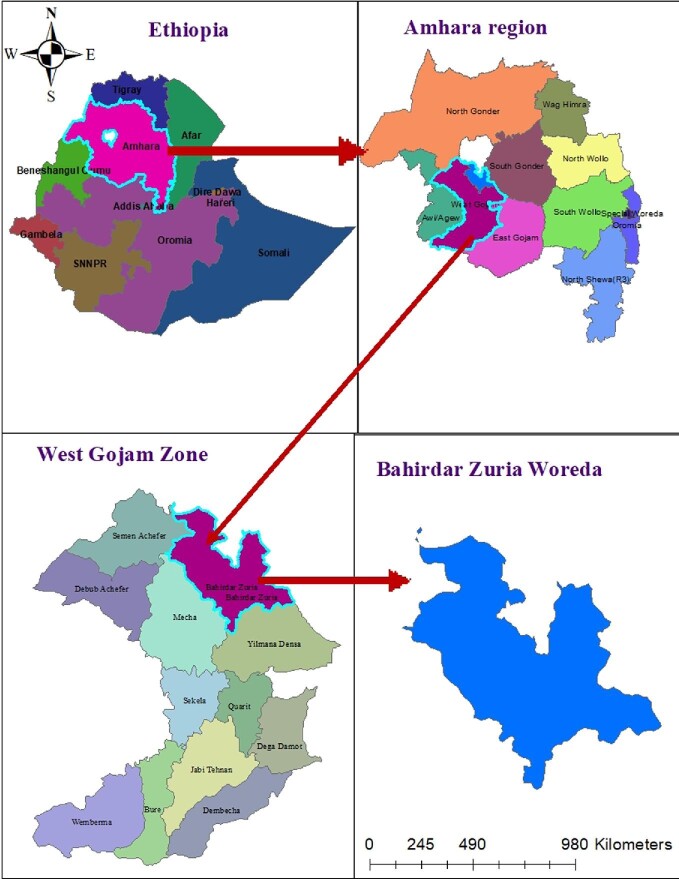

The study was conducted in Bahir Dar city, 520 km from the capital city, Addis Ababa, and two neighbouring rural kebeles (administrative subunits), Yinesa and Kinbaba, in the west Gojam zone of Amhara regional state, northeastern Ethiopia (Figure 1). The study was conducted from 16 November to 27 December 2019. The prevalence of podoconiosis in the region was 3.3% in 2012.17 The kebeles were selected as study sites for the podoconiosis immunology study due to their proximity (10 and 25 km from the capital Bahirdar) to laboratory facilities in Bahir Dar, thus making the logistics and sample transport feasible.

Figure 1.

A map of Ethiopia showing the study site at Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda in the west Gojam Zone of Amhara regional state (map generated using GIS Archmap v. 10.5).

Study design and participants

A qualitative study design was employed including in-depth interviews (IDIs) and FGDs. A modified semistructured interview guide, based on a similar study conducted in 2017 in the same region,11 was used to collect data on the consent process and stakeholder perception of research/researchers. Additional guide questions unique to this study were added, including ones addressing the nature of the specimens to be collected, compensation issues and factors that led to the mob attack. Six IDI guides were prepared for six groups: researchers and ethics review board members; health extension workers and podoconiosis focal persons (health professionals managing podoconiosis patients); podoconiosis patients; healthy community members (who did not have a history of podoconiosis or any other health condition; i.e. healthy individuals living in the same area as the patients); kebele and local religious leaders; and researchers who witnessed youth protests and property damage at the study site in the 2018 incidents. A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit participants for the different categories. We also enrolled participants purposefully for those who had experience of working with the patients and security officials who would provide a unique and rich perspective on events. Two FGD guides were prepared: one for discussion with zonal and regional security officials from Bahir Dar (who were selected because they participated in managing the incident in Bahir Dar) and a second for health professionals who had experience of working with the community. There were six and five participants in each FGD, respectively. The guides are attached as an appendix.

Method of data collection

The interview instruments were prepared in English then translated into the local language, Amharic. The interviews were recorded, coded and back-translated to English. The interviews were carried out for the different categories based on the IDI guide questions. The interview/data collection continued until data saturation or when no more new information was obtained. The interviews and the FGDs were performed by MN and two co-investigators, BS and TA, who have experience in qualitative research. MN and BS were from the national research institute while TA was from the local research institute. All the interviewers speak the local language Amharic, which is their mother tongue. The interviews were carried out in the workplaces of participants or in their resident villages. The interviewers were always accompanied and the participants were recruited by local health extension workers who had been working with the community for several years.

Data analysis

The recorded audio files were transcribed and translated to English by MN, BS and TA. The quality and consistency of each transcript was verified by an experienced independent person. Variability in response between IDIs and FGDs was assessed for inconsistency. The text data were imported to NVivo version 10 (QSR International, UK, London). The text data were coded based on predefined themes and additional themes generated during the coding process. Coded concepts or aggregated ideas were summarised in memos and linked to respective themes. Data were then analysed to identify patterns and unique ideas and to generate descriptive statements.

Results

We conducted 32 IDIs and 2 FGDs with 21 male and 22 female participants. The participants age range was from 18–67. The type and number of interviews for the different catchment area is presented in (Table 1). The majority of patients and apparently healthy community members were farmers who were unable to read or write. The data generated were organised into the following themes: community awareness about podoconiosis and health research; participant recruitment for research; information provision and the consent process; compensation; and mob action against researchers. Subthemes were generated for some of the main themes.

Table 1.

Type and number of interviews for each catchment area

| Study site | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Yinesa (IDIs) | Kinbaba (IDIs) | Bahir Dar (FGD) |

| Patients | 6 | 4 | - |

| Healthy community members | 5 | 4 | - |

| Kebele/religious leaders | 3 | 2 | - |

| Health extension workers | 2 | 1 | - |

| Health professionals | - | - | 1 (n=5) |

| Security officials | - | - | 1 (n=6) |

| Researcher/IRB member* | 5 | - | - |

Abbreviations: FGD, focus group discussion; IDIs, in-depth interviews; IRB, institutional review board.

Researchers/IRB members were from national and regional research institutes.

Community awareness about podoconiosis

Community members (i.e. podoconiosis patients, healthy community members, religious and community leaders) had different levels of awareness about podoconiosis. Responses from patients and healthy community members indicated that their awareness about the cause of podoconiosis and its treatment or prevention was poor. On the other hand, religious and community leaders were more knowledgeable in this regard. Also, different names were given to the disease (such as egir abata and mich ader to mean swelling and irritation of the leg, respectively) and there were beliefs and myths about the cause of the disease. Many community members did not differentiate research from routine healthcare (Supplementary file 1). These findings are in agreement with other similar research studies, including our own REA studies on podoconiosis.11,18,19

Participant recruitment for research

Two subthemes were identified around participant recruitment: approaching the community and the nature of specimens required for the research.

Approaching the community

All the study participants in all categories unanimously agreed that communities should be approached by trusted or known community representatives before recruiting participants to any kind of study. It was articulated that health extension workers or health professionals would do better in approaching the community for health-related research or interventions. These individuals had experience of working with the community for a number of years in different health areas such as vaccination and family planning services, meaning that trust was already established.

[T]hey all are from this community for this community so it could be the kebele leader or the health professionals. But since we would be coming to the health centres, it would be good if we are informed by health professionals who have better information and understanding about our condition (patient from Kinbaba).

Our community is suspicious. However, if we share information using kebele leaders and influential persons at church and other places, they would believe us; otherwise, if they see new faces they may not trust and accept you (kebele leader 1).

All the participants, and especially the health professionals and researchers, unanimously agreed on the issue of legality and securing permission from responsible bodies. They suggested strongly that researchers should have ethical approval and permission from all hierarchal levels before approaching the community or commencing sample collection.

[T]he researchers should follow legal/formal and hierarchal approach in having permission or communication. They should explain they are from federal or regional health institutions, if not, they may be subjected to scrutiny or dissemination of undesirable information (researcher from the regional research institute).

Nature of specimens collected

Researchers and health professionals affirmed that it is not easy to obtain blood samples for research purposes from the community.

I think the nature of the sample has a significant impact on recruitment, I know people in general and people from rural areas in particular have a negative attitude towards giving blood specimens let alone for research even for their own investigation or diagnosis (researcher from the regional research institute).

Patients and healthy community members also raised their concerns and fears about giving blood. It was evident that their fear is deeply rooted in their lack of knowledge or misunderstanding of biology and the researchers’ intentions. They mentioned that they feared running out of blood, getting sick if they give blood, that their blood would be used for unintended purposes and that they would be contaminated with HIV during venesection. Most importantly, they associated blood collection with HIV testing and they feared that they would be discriminated against by society if they tested positive and this was then disclosed.

We used to do PICT (provider-initiated counselling and testing for HIV by health professionals) and communities were usually afraid to get tested because if their test result is positive, they would be discriminated or would be accused of adultery. So whenever they are requested to give blood they assume that it is for HIV testing and they usually refrain. Moreover, they don't have that much experience in research and they may question what you want to do with their blood (health extension worker).

Information provision and the consent process

There were a variety of responses regarding the information sheet content and how the information should be conveyed to study participants. Researchers and institutional review board (IRB) members mentioned that it should cover the main objective of the study, the benefits and risks to participants, the participant's role, contact information and confidentiality. The majority of patients and healthy community members said they were illiterate and could not say what information should be provided.

It would be good if we are given information, like the cause of the disease, how to prevent it. Because, for example I don't know how the disease occurs, but if I have information, I could take precaution to prevent it from happening to me (healthy community member from Kinbaba).

Researchers and IRB members saw consent as a means with which to create understanding of the research process prior to the recruitment of participants on a voluntary basis. The consent could be written or verbal and it could differ depending on the scope of the research and the age of participants. We tried to explore if the community members preferred to give written or oral consent. A majority of them showed no preference between the two. A few said they preferred written consent.

I think it would be good if we sign it because it would show that you are more serious in helping our health problem (healthy community member from Yinesa).

Compensation

Researchers and IRB members unanimously agreed that the type and the amount of compensation is mainly determined by the nature of the study, the type of sample (e.g. factors that cause participants discomfort), the study location and the length of time required.

[W]hen you give money to research participants those individuals who did not participate may think those who are enrolled are selling their blood for money and could create unintentional and bad impression. But for instance, for podo patients if you give shoes or a sanitation product, the value could be much more than the money and…it would be better if it is in kind than in monetary forms (researcher from the regional research institute).

On the other hand, almost all of the patients and healthy community members did not comprehend the concept of compensation. They were expecting some kind of treatment or support, even when we were recruiting them for this study, once again blurring differentiation between research and therapy.

Question: Do you know that you will not get medical care by enrolling in our study?

Answer 1: No, I don't know, but if it is possible, I would like treatment and medication (patient from Kinbaba).

Answer 2: [D]oes that mean the research is just for a study purpose? In that case it is nonsense! (patient from Yinesa).

Mob action on researchers and properties

Given the violent acts that consisted of targeting researchers and their property (e.g. cars and research kits from the Bahridar incident), in our proposed study communities we explored their perspectives on these events. We asked what they thought the researchers’ shortcomings were and what could be done to avoid such incidents in future.

The community members contributing to this study had not been involved with or witnessed the attacks so we focused on information given by those researchers who were attacked, health professionals who followed the event closely and security officials who were trying to manage the situation.

Reasons for the attacks

Almost all the participants from the two FGD interviews (health professionals and security officials and the researchers who were attacked) attributed the violence primarily to community fears following calls to be vigilant regarding strangers who were alleged to have been sent out to disrupt communities in the region during that particular period of time. Additionally, the participants mentioned that there was a belief among the community that certain groups could potentially harm the society, for example, by sterilising their women.

The accident is mainly associated with circulation of rumours of alleged attempts to shrink the Amhara population through birth control. In the Addis Alem incident where the two researchers were killed, the youth spread a rumour that researchers were giving vaccination and injections to school children who were falling ill and dying from it. Many people believe that there are some interested groups who are intentionally trying to hurt the community (health professional 3 from the FGD).

[T]here were rumours circulating in the community especially among the youth that some groups were trying to harm the Amhara region intentionally one of the means being targeting young women and sterilising them. By then the youth were taking matters into their hands, and taking measures as retaliation with emotion, not only on researchers but on properties which they think were affiliated with these groups (researcher from the regional research institute).

The security officials, health professionals and researchers who were involved in the Bahir Dar incident all agreed that the lack of awareness regarding the research among local communities and officials before commencement of the project and sample collection was the major contributor.

The community didn't have any information about the research in Bahir Dar. Even me, as a security officer, I heard after the incident happened. The researchers just started their work in their own cars without informing the local community (security official 1 from FGD).

In Addis Alem, poor community awareness and the sterilisation perception were regarded as factors that aggravated the situation. Furthermore, taking place against a background of political reform and instability in the region, as well as in the country as a whole, exacerbated the situation.

The incidence is influenced by political motives. Because, during that time, there were high political tensions (security officials 3 and 4 from the FGD).

The amount of compensation (300 Ethiopian Birrs; approximately US 10) being paid by the national research institute was also identified as an additional contributing factor by participants from the FGDs, who felt the sum was excessive, leading the community to believe that young women were selling their blood and that the samples were being used for an unintended purpose.

10) being paid by the national research institute was also identified as an additional contributing factor by participants from the FGDs, who felt the sum was excessive, leading the community to believe that young women were selling their blood and that the samples were being used for an unintended purpose.

300 Birr was being paid for research participants, so that made the community to raise question like ‘If the study is legal, why money is given to participants after they gave blood?’ Previously, there was a rumour of HIV-infected blood injection in the community. So, the community's movement emerged from such kinds of information and rumours (health professionals 2 and 3 from the FGD).

What we didn't consider was the value of money varies at different places. 300 Birr did not make that much impression when we did our study at Merkato area (the biggest market place in Addis Ababa where a lot of money is exchanged) but it could be too much to regional city like Bahir Dar and we did not customise our rate to that (researcher from the previous attack).

The role of social media in the incident

Social media platforms such as Facebook are widely used among the youth in Ethiopia for networking and as primary sources of news and information. This can have undesirable consequences if they are used to spread unreliable information. In this study, it was indicated by almost all of the FGD participants that information about the incidents was being spread by Facebook within a short period of time.

[B]y the way all this happened after a Facebook post by activists claiming ‘some people in Bahir Dar were trying to sterilise our women with vaccination’. The post was later declared a mistake and corrected. But the damage was already done, we were lucky that people's lives were not lost (security official 5 from the FGD).

It was an intense environment, even at that moment the situation was being spread on social media and they were posting our photos and remarking the youth to take appropriate measure on us (researcher from the previous attack).

What were the r esearchers’ shortcomings contributing to the incidence of mob action on researchers and property in Bahirdar?

The researchers followed the standard procedures to obtain ethical approval from national to kebele levels. However, there were basic shortcomings mentioned by participants that caused the Bahirdar incident. The first (and the most important one) was that the researchers naively failed to appreciate the political unrest and the heightened tension or to engage the local community in the research process (to sensitise and create awareness with various stakeholders at different levels of the social structure). Moreover, they were not accompanied by trusted local facilitators, community leaders or health professionals.

[W]ith regard to formality and permission the researchers had fulfilled everything and followed the right procedure. But they did not do community sensitisation and engagement on the people they intend to enrol. They were also using mobile set up (cars) to collect samples and interview participants instead of health centres or institutions because they have to move around the city to locate potential participants (researcher and IRB member from the national research institute).

Discussion

The REA tool has been widely used in LMICs to tailor the consent process to the local sociocultural dynamics of the study population.20–22 Using this tool, we have explored issues that could be barriers to the consent process, specimen collection (e.g. blood) and the safe conduct of a study during community unrest.

Many of the patients and healthy community members lacked awareness about the cause, prevention and treatment of podoconiosis. There are different beliefs or myths about the disease. It is not uncommon in many LMICs to believe in such myths or taboos where there is a perception that diseases are caused by curses or lack of harmony or balance between individuals and nature.23,24 The lack of awareness in the rural community is mainly attributed to lack of education as many of them are illiterate. This is also reflected in their inability to differentiate between research and treatment. A number of studies,11,18,25 including that conducted by Abay et al. in northern Ethiopia, reported that rural residents found it difficult to differentiate research from routine diagnostic services.19

A study in northwest Cameroon reported that community sensitisation led by trusted people and with permission from all hierarchal bodies was key to the smooth conduct of a research project.26 However, these individuals can also impose undue influence on communities and persuade them to participate without genuinely understanding the research intent. This was also the case in our study, where community leaders explained that they are trusted by the community and can influence them to participate in any kind of study. This could be rooted in the trust and acceptance these community leaders have in the community, but from a ethical point of view it could be against the principle of autonomy and volunteer participation without coercion.27,28 Therefore, researchers have an important responsibility in supervising participant recruitment and sample collection and full training is required to ensure the process is not coercive.

A number of perceived fears were identified in this study around giving blood samples for the purposes of research. The fear of being contaminated with HIV and the potential of being discriminated against if a positive HIV test result is disclosed was shared by a majority of patients and healthy community members. This group of individuals seldom recognise the concept of confidentiality. Associating blood collection with HIV testing is common in LMICs.19 This is one of the gaps in awareness among the community and more emphasis should be given to this issue during the consent process. This would include further community sensitisation and training healthcare professionals in key concepts of confidentiality.

The misperception about the researchers’ intentions, leading to a physical attack, highlighted the importance of good engagement with the community prior to undertaking research. Similarly, a Buddhist mob set fire to Muslim-owned shops and homes in Digana, Sri Lanka, because of false rumours regarding sterilising pills found at a Muslim-owned pharmacy that spread by social media in April 2018.29 More than 20 people across 10 states in India were lynched because of rumours spread by word of mouth and social media that claimed the victims were child abductors.30 Therefore, it is going to be challenging to undo these beliefs held by the wider public.

Because the communities lack awareness about both the research and the consent process, there could be a trend that data collectors and researchers may enrol participants who do not have a genuine understanding of either the research or the consent process. Therefore, regulators or ethical bodies should oversee the activity of researchers in the field or at health facilities so that vulnerable groups are not exploited for research purposes. Supporting this, it was indicated that personnel who perform the consent process at the field are not adequately supported and supervised, which could lead to a breach in the ethical consent process.31 Although a lack of funding and time is regarded as a constraint to engagement with communities aiming to improve their awareness, it is pertinent to address this issue and secure genuine consent to minimise exploitation of vulnerable groups.

The number of people who preferred to give verbal consent is comparable with those who preferred to give written consent. Hence, researchers should first ask the participants which option they prefer. Some people view written consent with suspicion because they fear that if they sign something they could be traced and be held accountable for something in the future, or obliged to discharge extra duties like soil or water conservation activities and fertiliser utilisation.11,19 On the other hand, those who preferred written consent perceived research as a health intervention and therefore signing would make it more sound and its benefit credible.

The amount and the type of compensation provided for participants sometimes resulted in unintended outcomes. A payment of 300 Ethiopian Birrs (approximately US 10) for young female participants was perceived as if they were selling their blood and being exploited. Such payments, which did not appear much in a capital city setting, could cause concern in regional cities, as was the case indicated in this study. Hence, researchers or ethical bodies need to understand the sociodemographic characteristics of the local context when deciding on compensation options to protect participants from undue influence. Therefore, the amount should not be too much, which would incur biased volunteering and compromise local researchers who are usually underfunded.32 Lack of average local rates for compensation depending on the research nature and place of conduct, as well as variability in research funding, increase the difficulties when standardising the type and amount of compensation. In our study, we decided to cover the costs of transportation and sanitation materials like soap or bandages at the suggestion of health professionals and researchers from the study area. But it is potentially challenging to address issues that arise when those who did not participate learn about the compensation. This may arise because of the difficulty in differentiating research from routine healthcare, with those who did not participate in the research feeling that they have been treated unfairly, by missing out on treatment or support.

10) for young female participants was perceived as if they were selling their blood and being exploited. Such payments, which did not appear much in a capital city setting, could cause concern in regional cities, as was the case indicated in this study. Hence, researchers or ethical bodies need to understand the sociodemographic characteristics of the local context when deciding on compensation options to protect participants from undue influence. Therefore, the amount should not be too much, which would incur biased volunteering and compromise local researchers who are usually underfunded.32 Lack of average local rates for compensation depending on the research nature and place of conduct, as well as variability in research funding, increase the difficulties when standardising the type and amount of compensation. In our study, we decided to cover the costs of transportation and sanitation materials like soap or bandages at the suggestion of health professionals and researchers from the study area. But it is potentially challenging to address issues that arise when those who did not participate learn about the compensation. This may arise because of the difficulty in differentiating research from routine healthcare, with those who did not participate in the research feeling that they have been treated unfairly, by missing out on treatment or support.

The fact that researchers involved in the attack had not engaged beforehand with the community to create awareness and understanding was highlighted as a key oversight. Community engagement and building long-term partnerships are key to generating high quality research with a better impact.33 Creating strong interpersonal relationships between researchers, community members and research institutions is reported as being very important for building long-lasting trust between these entities.34

We have used the findings of this study to influence our informed consent process and the immunology study is underway. Furthermore, we have organised an ongoing community engagement programme (with >70 participants) at the study site with stakeholder representation from religious leaders, kebele leaders, health extension workers, health professionals, women community groups, youth, security officials, patients and healthy community members from the study site and different governmental administrative departments.

Through community engagement we tried to communicate fundamental aspects of podoconiosis disease (where the majority of the participants lack awareness), our research objectives, the intentions of our research institute and prior and ongoing research activities. The participants expressed their gratefulness for such events and described their willingness to support us and themselves through community sensitisation, participant recruitment, quelling undesirable rumours and being ambassadors for our research institute. To ensure the safety of the researchers as well as the participants, we have also decided to bring participants to nearby health facilities for specimen collection instead of going to the community or using cars. Moreover, this has further implications with regard to improving the quality of the research by promoting good relations with the community, smooth specimen collection and communication of the research findings later on. Overall, we tried to create awareness, rebuild trust and facilitate the successful progress of research studies on podoconiosis in this community towards understanding its aetiology and developing tools to prevent and treat this debilitating neglected tropical disease.

Conclusions

This REA identified ethical issues in the informed consent process in lower income settings, such as the knowledge gap about podoconiosis and the research concept, the challenge of collecting blood specimens, the need to approach participants by means of trusted community members, the preferred method of consent and a lack of clear criteria for appropriate compensation. We have also identified factors that led to mob attacks on researchers, the main reason being the perception of the local people that there were intentional attempts to shrink their population size using vaccination or research. It was felt that the researchers did not engage properly with the community prior to undertaking the research, further enhancing the mistrust towards them. Therefore, we advise researchers to assess the social and political dynamics of their proposed study area and engage with relevant stakeholders to create mutual understanding and trust as the situation may vary depending on local context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants who volunteered to participate in this study. We would like to thank APHI staff members Banchamlak Tegegne and Abebe Kelemowork for facilitating the study.

Appendix. Interview guide questions for IDIs and FGDs

IDIs guide to questions for researcher/IRB members

Questions related to personal and work information

-

• Can you please tell me about yourself?

■Prompt: training (educational background, specialisation), experience (research, ethics, fieldwork).

Questions related to consent and consent process

• How do you define consent? What is the main purpose of the consent process?

-

• How do you think the consent forms and information sheets be prepared?

■Prompt: aligned with the local people interest, language, educational status…?

-

• What are some of the most important aspects in designing a consent process?

-

○ Prompt:

■ Information—most important information to be provided?

■ Communication—best way to provide information about research.

-

-

• Why do you think people participate in research?

○ Therapeutic/non-ther apeutic distinction—do you think people in rural area understand they are participating in research, not healthcare?

• Is there anything that we haven't raised about consent processes?

Questions about the community

• Have you conducted any research in North West Ethiopia (Gojjam)?

• Are you aware of any colleague(s) who have worked in these areas?

• Do you think research conducted in these areas raise different issues compared to the same research being carried out elsewhere in Ethiopia?

■Prompt: cultural and diversity issues, language difference, literacy, poverty, cost-benefit analysis, social representations (e.g. age, gender, status).

Questions related to factors affecting recruitment

-

• Do you think the following issues could affect participant recruitment?

○ Nature of the study (e.g. immunopahtogenesis vs epidemiology)

○ Nature of the community (e.g. rural, illiterate).

○ Previous exposure to research.

○ Nature of the samples (saliva vs other sample types such as blood).

○ Are study participants afraid to give blood for research purposes from your experience? If yes, why?

-

○ What kind of compensation do you think is appropriate for study participants?

■Prompt: money, or in kind, how much do you think would be appropriate?

○ What other factors affect participant recruitment?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from the national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet that claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes, how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

○Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

• What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

IDIs guide questions for healthy community members

Personal questions

-

• Can you please tell me about yourself? What do you do for living?

○Prompt: Age, sex, educational status?

Question about podoconiosis

• What do you name the disease which cause the feet to swell?

-

• How do patients describe the disease?

○Prompt: cause, treatment, prevention

• Do you think the disease is hereditary?

• Do people in the community get married with podoconiosis affected family members? Why or why not?

Questions related to community approach, information provision and consent form

• Who do you prefer to contact with you to ask if you would be interested to participate in research? Why?

• How do you want to express your willingness once you have decided to take part in research? Prompt: verbal or written consent

Question to assess awareness and voluntariness

• Do you understand the difference between treatment and research? Can you please explain to me?

• Do you know that you will not get medical care by involving in our study?

• Do you know that you can decline to participate in the study at any time and you will not be denied healthcare access from aid providers or other government health facilities?

• Are you afraid to give blood for research? If yes why?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet which claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

■ Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information

• What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

IDIs guide to questions for podoconiosis patients

• What are some of the major health-related issues in your community?

Questions related to podoconiosis

• What do you call the disease in your area that cause the feet to swell?

-

• What do you know about podoconiosis?

■Prompt: cause, treatment, prevention.

• Do you think the disease is hereditary?

• Do people in the community get married with podoconiosis-affected family members? Why or why not?

Questions related to community approach, information provision and the consent form

• Who do you prefer to make contact with you to ask if you would be interested in participating in research? Why?

• How do you want to express your willingness once you have decided to take part in research? Prompt: verbal or written consent.

• How would you prefer the information to be presented to you? Prompt: individually, in a group with other people, with members of your family?

• Are you afraid to give blood for research? If yes, why?

Questions to assess awareness and voluntariness

• Do you understand the difference between treatment and research? Can you please explain this to me?

• Do you know that you will not get medical care by involvement in our study?

• Do you know that you can decline to participate in the study at any time and you will not be denied healthcare access from aid providers or other government health facilities?

• Are you afraid to give blood for research? If yes, why?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from the national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet that claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes, how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

■Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

• What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

IDIs guide to questions for fieldworkers and podoconiosis focal persons

Personal and work-related questions

-

• Can you please tell me a bit about your background and training?

○Prompt: How long have you been working with NGOs or government health office?

-

• How do you help podoconiosis patients?

○Prompt: providing health education, provide sanitation materials otherwise not accessible by patients, provide shoes and socks.

Question related to community understanding of podoconiosis

• How do the community describe podoconiosis? Prompt: cause, treatment and prevention?

Questions related to community awareness and approach

-

• How would you describe understanding of research by the community?

○ Do they understand the difference between research vs treatment, or research vs aid?

-

• What positive and negative myths exist about research? If there is a myth, what factors contributed to it?

○ How can understanding be promoted? How do we address the misconceptions?

-

• Who should approach the communities when we recruit participants in our future study?

○Prompt: local government officials, health extension workers, community leaders, community members? How can they assist us?

• Are participants afraid to give blood for research purpose? If yes, why?

-

• What kind of compensation do you think is appropriate for study participants?

■Prompt: Money, in kind, how much would be appropriate?

Questions related to consent and information provision

-

• Have you asked participants from this area to consent to research in the past 3 y? If yes:

○ How well do you think this community understands the idea of research and consent process?

○ How did you inform participants about the study?

• How easily participants understand our interest in immunological research?

• How do you think sensitive information (e.g. the status of their HIV screening) should be told to patients and families?

• In your opinion, what are some of the obstacles that hinder patients from disclosing private information to other people?

-

• How did you provide information about the study to participants?

○ Verbal or written.

○ Group or individual information provision.

• What would be some possible factors affecting recruitment of participants to our proposed immunopathogenesis study of podoconiosis?

-

• What kind of compensation do you think is appropriate for study participants?

○Prompt: Money, or in kind, how much do you think would be appropriate?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from the national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet that claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes, how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

○Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

• What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

IDIs guide questions for kebele heads and religious leaders

Personal and work-related question

• Would you please tell me about yourself, including what you do for living?

Question related to the community

-

• Would you please tell me a bit about the community?

○Prompt: culture, diversity, language and literacy, poverty, gender structure.

Questions about podoconiosis

• What do you know about podoconiosis? Cause, treatment and prevention.

• Do you think the disease is hereditary?

• Do people in the community get married with podoconiosis-affected family members? Why or why not?

Questions related to research and participation in research

• What do you understand by research?

• Have been involved in a research activity conducted in your kebele in the past 3 y? If yes: Why were you consulted? What did you do to help researchers?

• How does the community like to be treated by researchers? How should researchers approach the community?

Question related to decision-making norm

-

• How do people make a decision to take part in research?

○Prompt: by themselves or in the presence of the head of the family?

Questions related to the proposed study

• Do you think people would participate in this kind of study? Why or why not?

• What are some reasons why individuals won't participate in a research?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from the national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet that claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes, how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

■Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

• What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

IDIs guide questions for researchers from the previous Bahir Dar attack incident

Personal and work-related questions

• Can you tell me about yourself? Your job title, position, responsibility?

• What was the main objective of your research?

-

• What was your approach in participant recruitment?

○Prompt: your target group, who did you have to accompany you?

• Did you have ethical approval, support letter/permission from different levels of the local government offices?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• How the incident occurred (what happened)?

-

• Do you think place of participant recruitment had an effect for the occurrence of the incident?

○Prompt: rural/urban; facility-based/community-based; tent-based/using cars.

-

• How did you try to handle the situation?

○Prompt: Who did you contact or seek help from?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

○Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

-

• What do you think should be done to avoid such incidents in the future?

○Prompt: from different stakeholders’ perspectives (researchers, local focal persons, local authorities)?

-

• What kind of compensation do you think is appropriate for study participants?

○Prompt: Money, or in kind, how much do you think would be appropriate?

FGDs guide questions for kebele and zone security officials

Questions related to understanding of research

-

• Have you been contacted in the past 3 y by researchers seeking permission to undertake research?

■ Can you tell me about your experience?

■ How were you approached? What information were you provided with?

■ How do you facilitate or help them in the conduct of the study?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from the national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet that claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes, how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

■Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

• What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

• Are there any measures taken by the security officials or bureau after the incident to prevent such acts in the future? If so, what measures?

FGDs guide questions for health professionals working with the community

Questions related to understanding of research

-

• Have you been contacted in the past 3 y by researchers seeking permission to undertake research?

■ Can you tell me about your experience?

■ How were you approached? What information were you provided?

■ How do you facilitate or help them in the conduct of the study?

■ How should communities be told about our research and consent be secured for their willingness to participate in the research? Prompt: in written format or tell them verbally?

■ With what kind of person shall we approach the community to do such kind of research?

■ Shall we enroll participants by going to the community or bringing them to the health facility?

■ Does the community understand the difference between research & routine clinical care?

■ What is the community perception in giving blood sample for research purpose?

-

• What kind of compensation do you think is appropriate for study participants?

■Prompt: Money, in kind, how much do you think would be appropriate?

Questions about community measures taken on researchers

• Are you aware of previous aggressive measures taken on researchers and properties from the national research institute at Bahir Dar and Adet that claimed the lives of two researchers by the local people for the latter?

• What do you think is the reason for this aggressive act?

• What do you think the researchers failed to do?

• Do you think such acts are influenced by political motives? If yes, how?

-

• What was the contribution of social media in the incident?

○Prompt: posting the incident and spreading the information.

What do you think researchers should do to avoid such violent attack and confrontation?

Contributor Information

Mikias Negash, Brighton, and Sussex Centre for Global Health Research, , Department of Global Health and Infection, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, UK; Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Menberework Chanyalew, Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Tewodros T Gebresilase, Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Unit of Health Biotechnology, Institute of Biotechnology, College of Natural and Computational Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

Bizunesh Sintayehu, Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Temesgen Anteye, Amhara Public Health Institute, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

Abraham Aseffa, Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Melanie J Newport, Brighton, and Sussex Centre for Global Health Research, , Department of Global Health and Infection, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, UK.

Authors’ contributions

MN, MC, TG, AA and MJN contributed to conception and design; MN, BS and TA contributed to acquisition and analysis of data; AA and MJN monitored its progress, analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. MN, BS and MC drafted the manuscript; MJN and AA critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. MJN is the guarantor of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on NTDs at Brighton and Sussex Medical School using Official Development Assistance (ODA) funding [Grant number GHR 16/136/29]. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (AHRI)/All Africa Leprosy and Tuberculosis Rehabilitation and Training Centre (ALERT) Ethics Review Committee, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Approval number PO38/18) and the National Research Ethics Review Committee (Approval number 1414/1094/19). Verbal consent was obtained from each study participant. All audio and transcript data were kept confidentially with the data collectors. The transcript and the audio data were kept securely on one drive as a backup with accessibility only to the author and the data manager.

Data availability

None.

References

- 1.Nuffield Council on Bioethics . The Ethics of Research Related to Healthcare in Developing Countries, 2005.Available at http://nuffieldbioethicsorg/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/HRRDC_Follow-up_Discussion_Paperpdf[accessed 16 April 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afolabi MO, Okebe JU, Mcgrath N, Larson HJ, Bojang K, Chandramohan D. Informed consent comprehension in African research settings. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(6):625–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson L, Kass NE. Views of US researchers about informed consent in international collaborative research. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zumla A, Costello A. Ethics of healthcare research in developing countries. J R Soc Med. 2002;95(6):275–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull S, Farsides B, Ayele FT. Tailoring information provision and consent processes to research contexts: the value of rapid assessments. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(1):37–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negussie H, Addissie T, Addissie A, Davey G.. Preparing for and executing a randomised controlled trial of podoconiosis treatment in Northern Ethiopia: The utility of rapid ethical assessment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(3):e0004531–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addissie A, Abay S, Feleke Y, Newport M, Farsides B, Davey G. Cluster randomized trial assessing the effects of rapid ethical assessment on informed consent comprehension in a low-resource setting. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kengne-Ouafo JA, Millard JD, Nji TMet al. Understanding of research, genetics and genetic research in a rapid ethical assessment in north west Cameroon. Int Health. 2016;8(3):197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey G, Tekola F, Newport MJ.. Podoconiosis: non-infectious geochemical elephantiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(12):1175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tekola F, Bull S, Farsides Bet al. Impact of social stigma on the process of obtaining informed consent for genetic research on podoconiosis: a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebresilase TT, Deresse Z, Tsegay Get al. Rapid Ethical Appraisal: A tool to design a contextualized consent process for a genetic study of podoconiosis in Ethiopia. Wellcome Open Research.2017;2(99):99. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Reporter Ethiopia Magazine . Available at https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/article/mob-action-c osts-two-researchers-lives [accessed 4 February 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aljazeera news.Available at https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2018/09/ethiopia-thousands-protest-ethnic-violence-killed-23-1809171411 38078.html [accessed 9 June 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebola health workers killed and injured by rebel attack in Congo. Available at https://www.the guardian.com/global-development/2019/nov/28/ebola-health-workers-killed-and- injured-by-rebel-attack-in-congo [accessed 3 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.After Attacks on Researchers. Caution and Steadfastness. Available at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2008/08/06/after-attacks-researchers-cau tion-and-steadfastness [accessed 9 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covid 19 researchers are attacked, detained in at least 10 Brazilian states. Available at https://brazilian.report/coronavirus-brazil-live-blog/2020/05/17/covid-19-re searchers-attacked-detained-in-10-brazilians-states/ [accessed 9 December 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molla YB, Tomczyk S, Amberbir T, Tamiru A, Davey G.. Podoconiosis in East and West Gojam zones, northern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(7):e1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tekola F, Bull SJ, Farsides Bet al. Tailoring consent to context: designing an appropriate consent process for a biomedical study in a low income setting. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(7):e482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abay S, Addissie A, Davey G, Farsides B, Addissie T. Rapid ethical assessment on informed consent content and procedure in Hintalo-Wajirat, northern Ethiopia: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bull S, Farsides B, Tekola Ayele F. Tailoring information provision and consent processes to research contexts: the value of rapid assessments. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(1):37–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tindana P, Bull S, Amenga-Etego Let al. Seeking consent to genetic and genomic research in a rural Ghanaian setting: a qualitative study of the MalariaGEN experience. BMC Med Ethics. 2012;13(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tekola F, Bull SJ, Farsides Bet al. Tailoring consent to context: designing an appropriate consent process for a biomedical study in a low income setting. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(7):e482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Animut A.The burden of non-filarial elephantiasis in Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(12):1173–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin LA, Braun KL.. Asian and Pacific Islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Soc Work. 1998;23(2):116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill Z, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Odei-Danso S, Kirkwood B.. Informed consent in Ghana: what do participants really understand? J Med Ethics. 2008;34(1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kengne-Ouafo JA, Nji TM, Tantoh WFet al. Perceptions of consent, permission structures and approaches to the community: a rapid ethical assessment performed in North West Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malik AY.Physician-researchers’ experiences of the consent process in the sociocultural context of a developing country. AJOB primary research. 2011;2(3):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall PA. “Cultural competence” and informed consent in international health research. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2008;17(2):206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.False rumors set Buddhist against Muslim in Sri Lanka, the most recent in a global spate of violence fanned by social media. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/world/asia/facebook-sri-lanka-r iots.html[accessed 5 February 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Police arrest 25 people in India after latest WhatsApp lynching. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/15/india-police-arrest- 25-people-after-latest-whatsapp-mob-lynching-child-kidnapping-rumours[accessed 5 February 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molyneux S, Geissler PW.. Ethics and the ethnography of medical research in Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):685–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyangulu W, Mungwira R, Nampota Net al. Compensation of subjects for participation in biomedical research in resource–limited settings: a discussion of practices in Malawi. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assefa A. Time to take community engagement in research seriously. Ethiop Med J. 2019;57(1). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molyneux C, Peshu N, Marsh K.. Trust and informed consent: insights from community members on the Kenyan coast. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1463–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

None.