Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) potently suppresses Mv1Lu mink epithelial cell growth, whereas hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) counteracts TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition and induces Mv1Lu cell proliferation (J. Taipale and J. Keski-Oja, J. Biol. Chem. 271:4342–4348, 1996). By addressing the cell cycle regulatory mechanisms involved in HGF-mediated release of Mv1Lu cells from TGF-β inhibition, we show that increased DNA replication is accompanied by phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein and alternative regulation of cyclin-Cdk-inhibitor complexes. While TGF-β treatment decreased the expression of Cdk6, this effect was counteracted by HGF, followed by partial restoration of cyclin D2-associated kinase activity. Notably, HGF failed to prevent TGF-β induction of p15 and its association with Cdk6. However, HGF reversed the TGF-β-mediated decrease in Cdk6-associated p27 and cyclin D2-associated Cdk6, suggesting that HGF modifies the TGF-β response at the level of G1 cyclin complex formation. Counteraction of TGF-β regulation of Cdk6 by HGF may in turn affect the association of p27 with Cdk2-cyclin E complexes. Though HGF did not differentially regulate the total levels of p27 in TGF-β-treated cells, p27 immunodepletion experiments suggested that upon treatment with both growth factors, less p27 is associated with Cdk2-cyclin E complexes, in parallel with restoration of the active form of Cdk2 and the associated kinase activity. The results demonstrate that HGF intercepts TGF-β cell cycle regulation at multiple points, affecting both G1 and G1-S cyclin kinase activities.

Cell cycle progression of eukaryotic cells is controlled by sequential activation of cyclin–cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) complexes. Formation of complexes and regulation of their activity is highly specific, and distinct complexes drive cell cycle progression in the G1 (cyclins D1 to D3 in complex with Cdk4 or Cdk6), G1-S, and S phases (cyclin E-Cdk2 and cyclin A-Cdk2 or -cdc2) and in mitosis (cyclin B-cdc2) (32, 37, 44). Cdk’s are activated by association of the cyclin subunit and by stimulatory phosphorylation of a conserved threonine residue (Thr160 in Cdk2) by Cdk-activating kinase (CAK) (9, 13, 35, 48). A steric model of the Cdk2-cyclin A complex indicates that association of the cyclin subunit with the kinase leads to reorientation of the catalytic cleft and reveals the Thr160 phosphorylation site (19). In addition, activation of the kinase requires dephosphorylation of an inhibitory tyrosine residue by cdc25 phosphatase (11, 30). Kinase activity is negatively regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs). CDKIs have been grouped into two families related to p21Cip1/Waf1 and p16Ink4a/MTS1 (12, 46). In contrast to p16 family members (p15, p16, p18, and p19), which associate only with the Cdk’s, the members of the p21 family (p21, p27, and p57) associate with both cyclin and Cdk subunits (15). The crystal structure of Cdk2-cyclin A in complex with p27 indicates that p27 binds to the catalytic cleft of Cdk2, thus inactivating the kinase (42). Of the CDKIs, p21, p27, and p15 are regulated by growth factors (7, 16, 25, 39).

One of the targets of the Cdk complexes in G1-S-phase transition is the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein, pRb (21). pRb, and its relatives p107 and p130, bind to and inhibit the E2F family of transcription factors (52). They also directly interact with and regulate the activity of cyclin E-Cdk2 complexes (55). Binding sites for E2F have been found in several genes essential for cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase (44). The activity of pRb is regulated by its phosphorylation status, and the hypophosphorylated form of pRb associates with E2F. In late G1 phase, pRb is phosphorylated by cyclin D- and cyclin E-dependent kinases (45, 52), and these phosphorylations induce the dissociation of pRb from E2F and allow transcription of genes required for progression into S phase.

Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) is a member of large family of growth factors involved in regulation of cellular growth and differentiation (21, 50). TGF-β is the only known growth factor that reversibly arrests the growth of epithelial, endothelial, and hematopoietic cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle without permanently differentiating them. TGF-β treatment of mink lung epithelial cells prevents efficiently the phosphorylation of pRb (24). Inhibition of pRb phosphorylation by TGF-β is a result of complex regulation of the activities of Cdk’s and their inhibitors. TGF-β increases the expression of p15, which binds Cdk4/6-cyclin D complexes (16). Binding of p15 to Cdk4/6-cyclin D complexes leads to dissociation of p27 from these complexes and subsequent binding of p27 to Cdk2-cyclin E complexes and results in G1 growth arrest (40, 41). Concomitantly, TGF-β reduces the amount of the active, faster-migrating form of Cdk2 (22). TGF-β prevents also the association of cyclin D1 with Cdk4, apparently by upregulation of p15 in human mammary epithelial cells (43). In addition, inhibition of Cdk activity by TGF-β is suggested to be mediated by a decrease in the level of Cdk4 in Mv1Lu cells (10) and in cdc25A Cdk-activating phosphatase in p15-deficient mammary epithelial cells (18).

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is derived from mesenchymal cells and acts as a growth stimulator for epithelial cells. In addition, HGF stimulates the motility and invasiveness of epithelial and endothelial cells (2, 4, 31). We have previously shown that HGF releases epithelial and endothelial cells from TGF-β-induced growth arrest (49). To address the underlying mechanisms, we have analyzed the effects of TGF-β and HGF on the cellular levels of Cdk’s, cyclins, their specific inhibitors, and complex formation in Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial cells. We find here that HGF relieves TGF-β-mediated growth arrest by inhibition of TGF-β-mediated downregulation of Cdk6. These events lead to expression of Cdk6-cyclin D2 complexes at levels comparable to those in control cells and partial rescue of cyclin D2-associated kinase activity. Despite induction of p15 and relocalization of p27 inhibitor to Cdk6 and Cdk2 complexes, respectively, Cdk2-cyclin E-associated kinase activity is fully recovered in cells treated with both growth factors. Our data suggest that in cells treated with both growth factors, only a subpopulation of Cdk6 is inactivated by binding to p15, while the rest of Cdk6 remains in complex with cyclin D2 or cyclin D2-p27, thus possibly harvesting a part of p27 from that that forms complexes with Cdk2 and cyclin E. The decrease in the available p27 results in activation of Cdk2-cyclin E complexes sufficient for cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents.

Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial cells (CCL-64; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, Md.). In all assays, except when otherwise stated, the cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β1, 220 pM HGF, or both in DMEM containing 10% FCS for 16 h. TGF-β1 was purified from outdated human platelets (51), and recombinant human HGF was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.). 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (5-BrdUrd) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.).

Antibodies.

Antibodies used in immunoblotting assays for Cdk2 (M2), Cdk4 (C-22), and Cdk6 (C-21); cyclins D1 (H-295), D2 (C-17), and E (M-20); and p15 (C-20) and pRb (C-15) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). p27 antibody was from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.). Antibodies used to immunoprecipitate Cdk2 (M2), Cdk6 (C-21), cyclin D2 (C-17), and p27 (C-19) were also from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; cyclin E (no. 06-459) was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, N.Y.); and polyclonal p27 antibody was generous gift from J. Massagué (Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, N.Y.). Monoclonal antibodies against cyclin D1 (DCS-11) and Cdk6 (DCS-83) were generous gifts of Jiri Bartek (Danish Cancer Society, Copenhagen, Denmark). Mouse monoclonal antibody against 5-BrdUrd was from Amersham Life Sciences (Amersham, United Kingdom). Biotin-conjugated swine anti-rabbit and swine anti-mouse antibodies were from DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark).

Flow cytometry and 5-BrdUrd assays.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and 5-BrdUrd analyses were carried out essential as described earlier (14). Briefly, for FACS analysis, cells were trypsinized, pelleted by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (140 mM NaCl in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), and fixed with ice-cold 100% methanol at −20°C overnight. For DNA staining, the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in PBS containing 50 μg of RNase A (Sigma) per ml, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The DNA was stained with 50 μg of propidium iodide (Sigma) per ml at 4°C overnight, and the DNA content was analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson). The data were analyzed by the ModFIT program. For 5-BrdUrd analysis, cells grown on coverslips were incubated for 1 h with 50 μM 5-BrdUrd and fixed with 3.5% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min. After permeabilization of the cell membranes with 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) in PBS for 5 min, DNA was denatured with 1.5 M HCl for 30 min, washed with PBS, and stained with monoclonal antibody against 5-BrdUrd followed by rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (DAKO). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (2 μg/ml) (Sigma). The proportion of 5-BrdUrd-positive nuclei of all Hoechst 33258-stained nuclei was calculated by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation analysis.

For immunoblotting analysis of total cell lysates, cells were lysed with 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer, pH 6.8, containing 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 10% glycerol and incubated at 95°C for 10 min. DNA was sheared by sonication, and the protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford assay (3). Bromophenol blue was added (0.1% final concentration), and 10 μg of protein per lane was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by transfer to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The proteins were detected by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies by using biotin-avidin amplification and enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham Life Sciences). For immunoprecipitation studies, the cells were lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mg of leupeptin per ml, 0.1 mg of E-64 per ml, and 0.1 mg of soybean trypsin inhibitor per ml) on ice for 20 min and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation. The protein concentrations were measured by the Bio-Rad Dc protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates containing equal amounts of proteins were precleared with protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) or with GammaBind-G Sepharose (Pharmacia) for polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies, respectively, for 4 h, followed by incubation on ice overnight with the indicated antibodies. The immunocomplexes were precipitated with protein A-Sepharose or GammaBind-G Sepharose at 4°C for 40 min, washed six times with NP-40 lysis buffer, and separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to Immobilon-P membranes. The following percentages of polyacrylamide in SDS-PAGE were used for the detection of individual proteins: 7.5% for pRb; 10% for cyclin E; 12.5% for Cdk4, Cdk6, and cyclin D1-2; and 15% for Cdk2, p15, and p27.

For immunodepletion analysis, lysates were incubated for three sequential cycles with polyclonal anti-p27 antibodies on ice for 2 h followed by precipitation with protein A-Sepharose. After each precipitation, the lysates were recovered by centrifugation and subjected to the next precipitation cycle. Finally, the lysates were incubated with anti-cyclin E antibody and precipitated with protein A-Sepharose followed by kinase assay. Quantitation of proteins after immunoblotting analysis was carried out by Scion Image (Scion Corp.), version βeta2.

For metabolic labeling, cells were incubated with 150 μCi of [35S]methionine-cysteine labeling mix (Promix; Amersham Life Sciences) per ml in methionine-cysteine-free medium containing 10% dialyzed FCS for 2 h. To determine the half-life of Cdk6, cells were labeled with [35S]methionine-cysteine labeling mix in methionine-cysteine-free medium containing 10% dialyzed FCS for 2 h, as above, followed by three washes with growth medium and chases for the indicated times in the presence of growth factors. Cells were lysed in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 1% SDS and boiled for 5 min. For Cdk6 immunoprecipitation, equal amounts of denatured cell lysates were diluted 1:10 into RIPA buffer (final concentration of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 containing 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mg of leupeptin per ml 0.1 mg of E-64 per ml, and 0.1 mg of soybean trypsin inhibitor per ml) followed by immunoprecipitation, as described above.

Northern analyses.

mRNA was isolated by using oligo(dT)-cellulose column chromatography (Calbiochem). mRNA (3 μg per lane) was separated on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel and transferred to a Hybond-N membrane in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). RNA was detected by probing with a human Cdk6 XmnI cDNA fragment labeled with [α32P]dCTP by random priming (Ready-To-Go; Pharmacia). Full-length Cdk6 cDNA was a kind gift of J. LaBaer and E. Harlow.

Kinase assays.

Kinase assays were carried out essentially as described by Matsushime et al. (29). Briefly, cells were lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer and immunoprecipitations were carried out as described above, except that beads were washed four times with NP-40 lysis buffer followed by two washes with 50 mM HEPES-Cl, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM DTT. The beads were suspended in 30 μl of kinase buffer (50 mM HEPES-Cl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2.5 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM NaF, 20 μM ATP, and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP [3,000 Ci/mmol] [Amersham Life Sciences]) containing 1 μg of histone H1 (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) or 2 μg of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Rb (17) as a substrate. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min with occasional mixing of the beads. Phosphorylated proteins were visualized by autoradiography after separation by SDS–12.5% PAGE. Quantitations of the autoradiograms were carried out with a Fujifilm BAS-2500 Image Analyser and MacBAS 2.5. Kinase activities resulting from nonimmune rabbit serum or rabbit or mouse immunoglobulin G were subtracted in each assay.

RESULTS

HGF counteracts TGF-β-Induced G1 arrest of Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial cells.

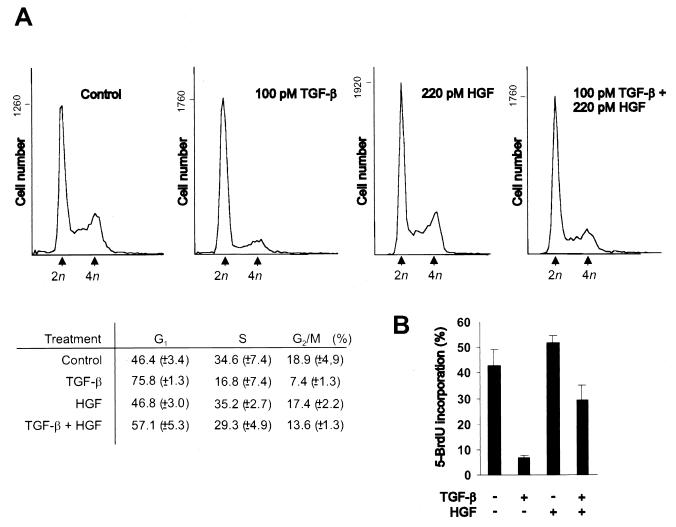

We have previously found that HGF releases Mv1Lu cells from TGF-β-mediated growth arrest and induces anchorage-independent growth of Mv1Lu cells (49). To analyze the effects of TGF-β and HGF on cell cycle distribution of Mv1Lu cells, exponentially growing Mv1Lu cells were incubated with TGF-β (100 pM), HGF (220 pM), or both in growth medium for 16 h. Subsequently, the cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide, and the DNA contents were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS). FACS analysis indicated that in TGF-β-treated cells, the fraction of G1-phase cells had increased to 76%, compared to 46% in control cells (Fig. 1A). The cell cycle distribution of HGF-treated cells was similar to that of control cells. Treatment of the cells with both TGF-β and HGF decreased the fraction of growth-arrested cells, as shown by an increase of S-phase cells to 29%, compared to 17% in TGF-β-treated cells (Fig. 1A), and a decrease in the fraction of G1-phase cells from 76 to 57%. To further analyze the effects of these growth factors on DNA synthesis, we measured the DNA replication activity of the cells by 5-BrdUrd incorporation followed by immunostaining. Upon TGF-β-treatment, only 7% of cells replicated their DNA, compared to 43% in control cells (Fig. 1B). HGF slightly induced DNA synthesis, as 52% of cells were 5-BrdUrd positive. DNA replication was resumed in cultures treated with both TGF-β and HGF, and 29% of the cells incorporated 5-BrdUrd (Fig. 1B). HGF thus prevents the TGF-β-induced G1 block in Mv1Lu cells.

FIG. 1.

Effects of TGF-β and HGF on cell cycle distribution of Mv1Lu cells. Exponentially growing Mv1Lu cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β, 220 pM HGF, or both in DMEM containing 10% FCS for 16 h. (A) Flow cytometry analysis. Inset: percentages of cells in different cell cycle phases. 2n and 4n, diploid and tetraploid DNA contents, respectively. (B) 5-BrdUrd incorporation. Cells were labeled with 5-BrdUrd during the last hour of the 16-h incubation, and 5-BrdUrd incorporation was detected by immunostaining. The results are expressed as percent 5-BrdUrd-positive nuclei of Hoechst 33258-stained nuclei. The results are averages of five independent experiments; standard deviations are shown.

Inhibition of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation by TGF-β is prevented by HGF.

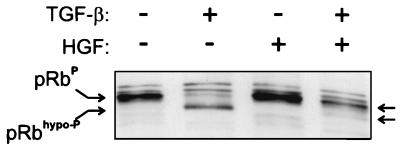

In TGF-β-treated, G1-arrested Mv1Lu cells, pRb is rendered in its underphosphorylated form (24). To study whether HGF modulates the effects of TGF-β on pRb phosphorylation, we analyzed by immunoblotting the phosphorylation status of pRb in Mv1Lu cells treated with TGF-β and/or HGF for 16 h. In the TGF-β-treated cells, the majority of pRb was in its faster-migrating, underphosphorylated form (Fig. 2), whereas in cells grown in the presence of HGF, the migration of pRb was similar to that in control cells (Fig. 2). In the presence of both growth factors, pRb was predominantly in its phosphorylated form, but a single faster-migrating underphosphorylated form was also detectable (Fig. 2). These alterations in pRb phosphorylation patterns reflect the observed effects on cell growth and indicate that the HGF-induced signal that prevents TGF-β mediated growth arrest acts at or before pRb phosphorylation.

FIG. 2.

Effects of TGF-β and HGF on phosphorylation of pRb. Mv1Lu cells were treated with TGF-β (100 pM) and HGF (220 pM), as indicated, and incubated for 16 h, and the cells were lysed with Laemmli sample buffer. Total cellular lysates (10 μg) were separated by SDS–7.5% PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane, followed by immunoblotting against pRb. The hypophosphorylated (pRbhypo-P) and hyperphosphorylated (pRbP) forms of pRb are indicated (arrows).

TGF-β inhibition of Cdk6 synthesis is counteracted by HGF, whereas TGF-β induction of p15 remains intact.

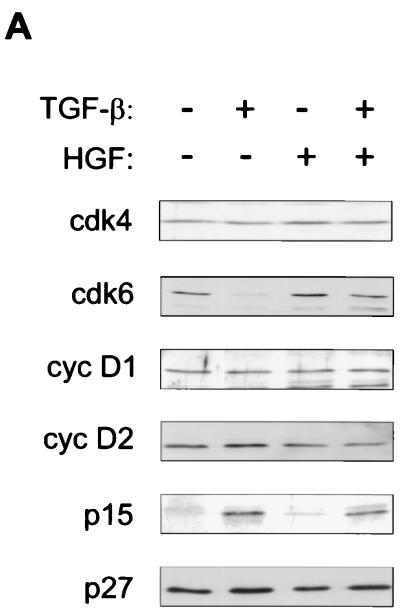

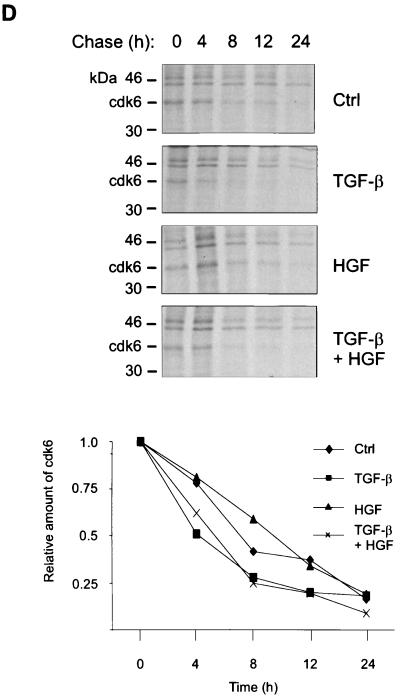

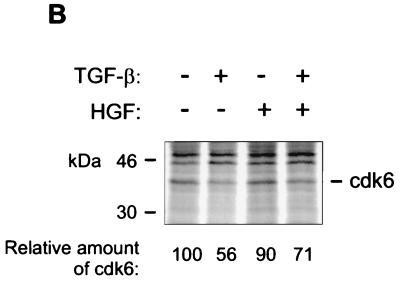

pRb is phosphorylated in G1 by cyclin D complexes (5, 20, 26, 53). To study how HGF signaling interacts with TGF-β signaling to prevent the shift of pRb to its underphosphorylated form, we analyzed the effects of TGF-β and HGF on the levels on G1 Cdk’s (Cdk4 and Cdk6), cyclins D1 and D2, and their respective inhibitors (p15, p27, p21). Exponentially growing Mv1Lu cells were incubated in medium containing TGF-β and HGF for 16 h. Concordant with previously published results (41), analysis of total cellular extracts by immunoblotting with specific antibodies indicated that TGF-β induced expression of p15 and did not affect the level of Cdk4, cyclin D1 or D2, or p27 (Fig. 3A). Additionally, although p21 CDKI has been suggested to mediate TGF-β growth inhibition (7), its levels in Mv1Lu cells were found to be low and were not affected by TGF-β (41) or TGF-β and HGF (data not shown). Although HGF antagonized TGF-β-induced growth arrest, it did not prevent TGF-β-mediated induction of p15 (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, TGF-β decreased the expression of Cdk6 present in total cell lysates by 75% (±14% [n = 3]) compared to controls, whereas concomitant HGF treatment restored expression (Fig. 3A). The results were confirmed in metabolically labeled cells treated with the respective growth factors for 16 h. TGF-β decreased the synthesis of Cdk6 by 44%, whereas HGF alone had no effect (Fig. 3B). In the presence of both growth factors, Cdk6 synthesis was restored (Fig. 3B). Analysis for Cdk6 mRNA expression showed the presence of multiple transcripts all expressed at low levels, as described previously (6), none of which was significantly affected by TGF-β treatment of the cells (Fig. 3C) or by HGF or their combination (not shown). Chase experiments were performed to address whether TGF-β regulates Cdk6 expression by affecting the half-life of the protein. Mv1Lu cells were incubated in the presence of growth factors for 16 h and labeled for the last 2 h with [35S]methionine-cysteine, followed by washing off of the label and chasing for the indicated time in the presence of each growth factor. The results show that whereas the half-life of Cdk6 in control cells was 7 h, it was decreased in TGF-β-treated cells to 4 h (Fig. 3D). HGF, on the other hand, prevented the turnover of Cdk6 by increasing the half-life to 10 h (Fig. 3D). Concomitant treatment of the cells with TGF-β and HGF led to partial restoration of Cdk6 turnover (half-life, 5.5 h [Fig. 3D]). We conclude from the above experiments that TGF-β decreases Cdk6 expression by inhibiting Cdk6 synthesis and by increasing its turnover and that HGF opposes both of these effects.

FIG. 3.

Growth factor effects on G1 Cdk’s, cyclins, and their inhibitors. (A) Mv1Lu cells were treated with growth factors, as indicated, and cell lysates were prepared, followed by immunoblotting analysis as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The proteins were detected by using the indicated antibodies. (B) Mv1Lu cells were treated with growth factors for 16 h and labeled for the last 2 h with [35S]methionine-cysteine, followed by analysis of cell lysates by immunoprecipitation with a Cdk6 antibody. The autoradiograms were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. (C) Northern analysis of cells treated with TGF-β was performed for the indicated times by using human Cdk6 as a probe, followed by quantitation of the signals by PhosphorImager analysis. Fold changes in the three most abundant mRNA transcripts are shown below. Black bars, 2.4 kb; shaded bars, 1.8 kb; white bars, 1.1 kb. (D) Chases of metabolically labeled Mv1Lu cells were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Signals from Cdk6 immunoprecipitates were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. The relative levels of Cdk6, compared to the amount of Cdk6 present at time zero (set at 1) in cells treated with the respective growth factor, are plotted. The results are means of two independent experiments.

HGF opposes TGF-β-mediated downregulation of cyclin D2-associated Cdk6 and Cdk6-associated p27.

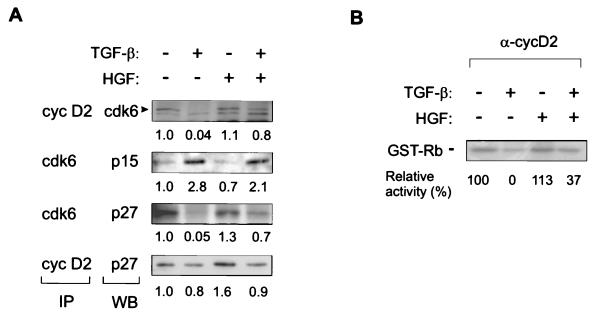

The changes in the G1 cyclin-Cdk complexes and their interaction with inhibitors were studied by immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting. As cyclin D2 is the predominant cyclin in Mv1Lu cells (10, 41), cyclin D2 complexes were analyzed in further experiments. Cell lysates of Mv1Lu cells incubated in medium containing TGF-β and HGF for 16 h were immunoprecipitated with Cdk6 or cyclin D2 antibodies followed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for CDKIs or Cdk6, as indicated. The results showed that TGF-β induced the association of p15 with Cdk6 by 2.8-fold, and a similar level of association was found in cells treated with both growth factors (Fig. 4A). Upon TGF-β treatment, the association of Cdk6 with cyclin D2 was decreased by over 90%, as well as the binding of p27 to Cdk6 (Fig. 4A). The latter effects probably reflect the presence of lesser amounts of Cdk6 in TGF-β-treated cells, as well as displacement of p27 from Cdk6 complexes by p15, as suggested earlier (41). HGF treatment alone had no major effects on cyclin D2 and Cdk6-associated p27, p15 bound to Cdk6, or Cdk6 complexed with cyclin D2 (Fig. 4A). However, HGF restored the association of Cdk6 with cyclin D2 and Cdk6 binding to p27 from TGF-β-exerted negative regulation (Fig. 4A). The presence of higher amounts of Cdk6 and Cdk6-associated proteins in these complexes fits well with the counteraction of HGF on Cdk6 regulation by TGF-β (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 4.

Effects of growth factors on complex formation of G1 Cdk’s, cyclins, and associated kinase activities. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of immunoprecipitated complexes. Immunoprecipitations (IP) were carried out first with antibodies against Cdk6 and cyclin D2, followed by separation by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were then transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane, followed by Western blotting (WB) with the indicated antibodies. The signals were quantitated with Scion Image, as described in Materials and Methods, and fold changes compared to controls are shown below each analysis. (B) Cyclin D2-associated kinase activity was determined by using GST-Rb as a substrate. Kinase activities were quantitated by PhosphorImager, the kinase activity given by nonimmune serum was subtracted, and the activities were compared to the level in control cells, which was set at 100.

To address directly whether HGF is able to bypass the TGF-β-mediated cell cycle block through altered regulation of G1 cyclin complexes, we analyzed the regulation of cyclin D2-associated GST-Rb kinase activity by growth factors. Cyclin D2-associated GST-Rb kinase activity in control and HGF-treated cells was 14% of that of Cdk2-associated GST-Rb kinase activity (not shown). In TGF-β-treated cells, there was virtually no cyclin D2-associated kinase activity (Fig. 4B). In cells treated with both growth factors, HGF was able to partly rescue the kinase activity, although it still remained low (37% of control) (Fig. 4B). This suggests that HGF may override the TGF-β block by mechanisms other than solely regulation of G1 cyclin-Cdk complexes.

The results indicate that HGF fails to prevent TGF-β-induced accumulation of p15 and its association with Cdk6. Though the total levels of Cdk6 decline in TGF-β-treated cells, there appears to be enough Cdk6 to bind available p15, thus suggesting the presence of lesser amounts of p15 than Cdk6 in TGF-β-treated cells. In contrast, HGF prevents TGF-β-mediated decrease of free and cyclin D2-bound Cdk6. The restoration of Cdk6 expression in cells treated with both factors could also lead to its binding of more p27, thus harvesting a part of p27 from that bound to Cdk2 complexes.

HGF counteracts TGF-β regulation of Cdk2.

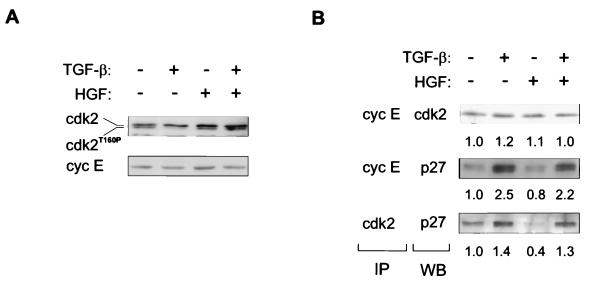

Cdk2-cyclin E complexes phosphorylate pRB in late G1 phase (1, 26). TGF-β treatment decreases the activity of Cdk2-cyclin E complexes by enhancing the association of p27 to these complexes (39–41). Concomitantly, TGF-β decreases the amount of the faster-migrating, active form of Cdk2 (22, 41). Both of these events lead to a decrease in Cdk2-associated kinase activity. To study whether the changes in phosphorylation of pRb effected by TGF-β and HGF in Mv1Lu cells are due to altered regulation of Cdk2 and cyclin E complexes, we analyzed the effects of growth factors on Cdk2 and cyclin E protein expression and their association with the inhibitor p27.

Immunoblotting analysis of total cell lysates of growth factor-treated cells revealed no changes in the expression of Cdk2 or cyclin E (Fig. 5A). However, as shown before (22), TGF-β decreased the amount of the faster-migrating, active form of Cdk2 (Fig. 5A) whereas HGF had no effect on the migration of Cdk2 compared to control cells (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, when cells were treated with both growth factors, the TGF-β-mediated decrease in the faster-migrating form of Cdk2 was efficiently prevented by HGF (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Effects of TGF-β and HGF on expression and complex formation of Cdk2 and cyclin E. Mv1Lu cells were treated with the indicated growth factors, and cell lysates were prepared. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of Cdk2 and cyclin E. The different forms of Cdk2 are indicated (Thr160 phosphorylated form of Cdk2 is designated cdk2T160P). (B) Complex formation of cyclin E and Cdk2 was detected by immunoprecipitation (IP), followed by Western blotting (WB) analysis with the indicated antibodies. Fold changes compared to controls are shown below each analysis.

The effects of TGF-β and HGF on complexes of Cdk2, cyclin E, and p27 were studied by immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting analysis. Growth factor treatments had no effect on the amount of cyclin E-associated Cdk2 (Fig. 5B). The amount of p27 in complexes with Cdk2 or cyclin E was induced 1.4- and 2.5-fold, respectively, by TGF-β treatment (Fig. 5B). HGF alone decreased the amount of p27 associated with Cdk2 by over half but had little effect on the association of p27 with cyclin E (Fig. 5B). In cells treated with both growth factors, the amount of p27 bound to Cdk2 or cyclin E was similar to that found in cells treated with TGF-β alone (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that HGF alleviates the decrease in the faster-migrating form of Cdk2 induced by TGF-β, whereas it has only a slight effect on the formation of complexes between p27 and Cdk2 or cyclin E in response to TGF-β.

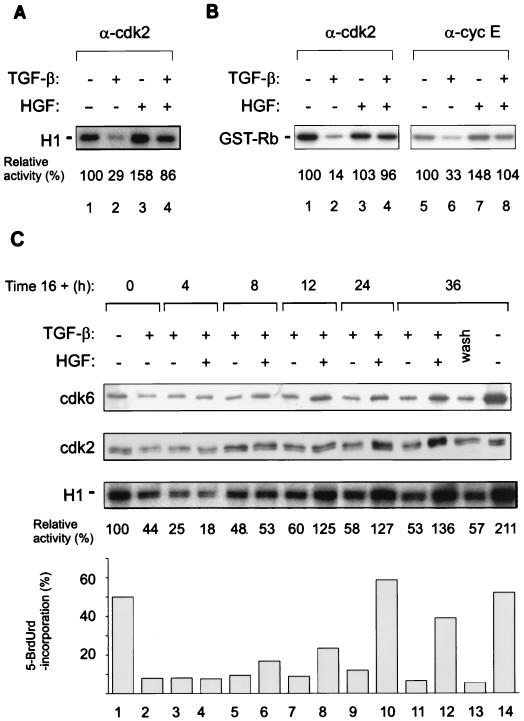

HGF restores TGF-β-suppressed Cdk2 and cyclin E kinase activities towards histone H1 and GST-Rb.

Association of p27 CDKI with Cdk2 complexes, induced by TGF-β, inactivates kinase activity (40, 41). The regulation of Cdk2-cyclin E complexes by growth factors was studied with histone H1 and GST-Rb as substrates. Cells were treated with TGF-β and HGF, as described above, and cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with Cdk2 and cyclin E antibodies, followed by kinase assays (29). The Cdk2-associated kinase activity towards histone H1 in TGF-β-treated cells was 30% of control, whereas HGF induced the kinase activity by 1.6-fold (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 3). In cells treated with both TGF-β and HGF, Cdk2-associated kinase activity was 90% of control (Fig. 6A, lane 4). Similarly, GST-Rb was used as a substrate for Cdk2 and cyclin E-associated kinase activities (Fig. 6B). In TGF-β-treated cells, Cdk2-associated kinase activity was 14% of control (Fig. 6B, lane 2), whereas HGF treatment had no major effect on kinase activity (Fig. 6B, lane 3). In cells treated with both factors, HGF counteracted the TGF-β effect on Cdk2 kinase activity towards GST-Rb and restored it to levels similar to those in control cells (Fig. 6B, lane 4). Accordingly, cyclin E-associated kinase activity towards GST-Rb in TGF-β-treated cells was 30% of control (Fig. 6B, lane 6), whereas HGF alone stimulated the activity only slightly (Fig. 6B, lane 7). However, HGF restored TGF-β-repressed cyclin E-associated kinase activity (Fig. 6B, lane 8).

FIG. 6.

Cdk2- and cyclin E-associated kinase activities of TGF-β- and HGF-treated Mv1Lu cells. Cells were treated with the indicated growth factors, followed by lysis in NP-40 buffer. Immunoprecipitations with the indicated antibodies and kinase assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cdk2-associated kinase activity with histone H1 as a substrate. (B) Cdk2 (lanes 1 to 4)- and cyclin E (lanes 5 to 8)-associated kinase activities with GST-Rb as a substrate. The figures show relative kinase activities compared to control cells (set at 100). (C) Sparsely seeded cells were pretreated with TGF-β (400 pM) for 16 h, followed by addition of HGF (220 pM) without removal of TGF-β, and incubations were continued for the indicated times (4 to 36 h). Untreated control cells are included (lanes 1 and 14). In wash, cells treated with TGF-β for 16 h were washed four times with growth medium, followed by addition of fresh medium. The cells were lysed, followed by Cdk6 and Cdk2 immunoblotting and determination of Cdk2-associated kinase activity towards histone H1. Relative kinase activities after subtraction of the kinase activity given by nonimmune serum are shown compared to cells treated with TGF-β for 16 h (set at 100) (lane 1). 5-BrdUrd incorporation was analyzed for the last hour of each incubation. The results are expressed as percent 5-BrdUrd-positive nuclei of Hoechst 33258-stained nuclei.

We next wanted to address whether HGF can bypass TGF-β-mediated growth arrest under conditions in which cells are first arrested in G1 by a 16-h incubation with TGF-β, followed by addition of HGF without the removal of TGF-β. After addition of HGF to the cells, the cells were further incubated for 4 to 36 h, followed by analysis of Cdk6 and Cdk2 (by immunoblotting), Cdk2-associated kinase activity towards histone H1, and DNA replication in cells. Addition of HGF to TGF-β-arrested cells for 12 h was sufficient to induce an increase in DNA replication of the cells (from 9 to 23%), with a significant portion of the cells replicating their DNA by 24 h after HGF addition (59%) (Fig. 6C). In contrast, attempts to wash TGF-β away followed by addition of fresh growth medium were without effect on DNA replication in cells even after a 36-h incubation. Concomitant analyses of Cdk6, Cdk2, and Cdk2-associated kinase activity showed that, firstly, HGF restored Cdk6 expression within 12 h after addition. Secondly, immunoblotting analyses of Cdk2 indicated that while in TGF-β-treated cells Cdk2 remained in its slower-migrating form, in HGF-treated cells Cdk2 showed a significant shift to its faster-migrating form by 24 h, kinetics that paralleled entry of the cells into S phase (Fig. 6C, lane 10). Furthermore, HGF stimulated kinase activity by twofold at 12 h after addition of HGF to the TGF-β-arrested cells (Fig. 6C, lane 8), which remained at the same level of induction at 24 and 36 h after exposure to HGF (Fig. 6C, lanes 10 and 12). The results show that HGF releases Mv1Lu cells from TGF-β-mediated growth arrest with concomitant upregulation of Cdk6 and increased Cdk2-cyclin E activities.

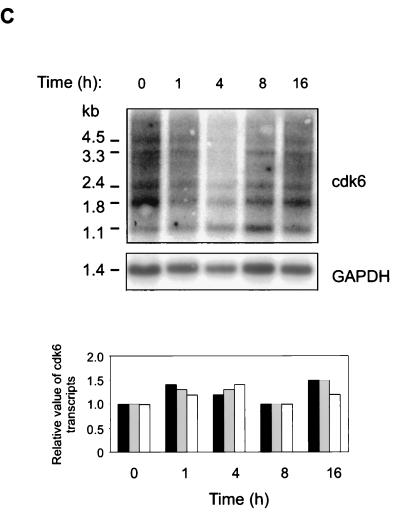

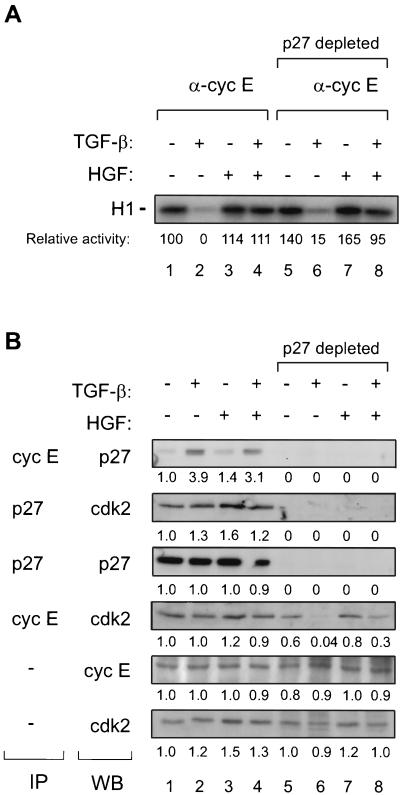

Regulation of cyclin E-associated kinase activity towards histone H1 is not affected by p27 immunodepletion.

The observed growth factor regulation of Cdk2 and cyclin E activities could result from complexes devoid of p27. To study further the action and regulation of p27 present in Cdk2-cyclin E complexes by TGF-β and HGF, we immunodepleted lysates of growth factor-treated cells with polyclonal anti-p27 antibodies. After three immunodepletion cycles with anti-p27 antibody, the lysates were either directly resolved by SDS-PAGE or immunoprecipitated with cyclin E or p27 followed by immunoblotting analysis. The depletion steps removed all detectable p27, cyclin E-associated p27, and p27-associated Cdk2 but did not significantly affect the total levels of cyclin E or Cdk2 (Fig. 7B, lanes 5 to 8). p27 immunodepletion removed 40 and 20% of cyclin E-bound Cdk2 present in control cells and in HGF-treated cells, respectively (Fig. 7B, lanes 5 and 7), whereas in TGF-β-treated cells cyclin E-associated Cdk2 was lost almost totally, reflecting the higher amounts of p27 bound to this complex upon TGF-β treatment (Fig. 7B, lane 6). Instead, in cells treated with both growth factors, 30% of cyclin E-bound Cdk2 was left after immunodepletion, suggesting that less p27 remains attached with cyclin E-Cdk2 complexes.

FIG. 7.

(A) Growth factor regulation of cyclin E-associated kinase activity following p27 immunodepletion. Sparsely seeded cells were treated with TGF-β (100 pM) and HGF (220 pM), as indicated, followed by lysis in NP-40 buffer. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with cyclin E antibody (lanes 1 to 4) or with three subsequent cycles of polyclonal p27 antibody, followed by cyclin E immunoprecipitation (lanes 5 to 8). Kinase assays towards histone H1 were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Relative kinase activities after subtraction of the kinase activity given by nonimmune serum compared to control cells (set at 100) are indicated. (B) Effects of p27 immunodepletion steps on cyclin E, Cdk2, p27, and their complexes. In parallel with experiment represented by panel A, cell lysates before and after three immunodepletion cycles with anti-p27 antibody were analyzed by immunoprecipitation (IP) with the indicated antibody, followed by immunoblotting (WB). Total cyclin E and p27 were analyzed by immunoblotting. Fold changes compared to controls are shown below each analysis.

Histone H1 kinase assays, carried out in parallel with the above experiment, indicated that TGF-β decreased the cyclin E-associated kinase activity to close to basal levels in both p27-depleted and nondepleted lysates (Fig. 7A, lanes 2 and 6). Depletion of p27 from cells treated with both growth factors had no effect on the activity (Fig. 7A, lanes 4 and 8). In control cells, kinase activity was somewhat increased by p27 immunodepletion. However, in repeated immunodepletion experiments, the increase varied between 1.1- and 1.4-fold. The p27 depletion assays suggest that though p27 is associated with Cdk2-cyclin E complexes in cells treated with both TGF-β and HGF and part of these complexes is removed, there appears to be enough active complex present in cells for cellular proliferation.

DISCUSSION

Cancer cells escape cellular growth control by ignoring growth inhibitory signals, such as TGF-β. The TGF-β signal transduction pathway is well studied, and many of the components that are involved in the TGF-β signaling pathway are mutated or have altered functions in malignant cells (28, 50). However, little is known about how cells respond to simultaneous inhibitory and stimulatory growth factors and on what level these signals are integrated. Mv1Lu cells are extremely sensitive to growth inhibition by TGF-β, and this growth regulation has been extensively studied (10, 22, 24, 38, 40, 41). We found earlier that HGF prevents TGF-β-induced growth arrest in Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial cells and in endothelial cells (49). This finding gave us an in vivo model system for study of the TGF-β growth arrest and cell cycle regulatory mechanisms that allow cells to escape TGF-β-induced G1 block. Flow cytometry analyses and 5-BrdUrd incorporation studies indicated that HGF decreased the number of Mv1Lu cells arrested in G1 phase by TGF-β. The observed fourfold increase in DNA synthesis in cells treated with both TGF-β and HGF, compared to TGF-β-treated cells, is in line with the observation that most of pRb is phosphorylated after treatment of cells with both growth factors. As TGF-β is a very potent growth inhibitor of Mv1Lu cells (50% effective dose, ≤5 pM), rescue from TGF-β growth arrest by HGF was significant, albeit not complete. Concomitant with the rescue of TGF-β-induced G1 arrest by HGF, we found that HGF opposed the TGF-β effects by inhibiting the TGF-β-mediated decrease in Cdk6 expression and the decrease of Cdk6 association with p27 and cyclin D2. However, HGF was unable to interfere with TGF-β induction of p15 and its complex formation with Cdk6. The results suggest that as a consequence less p27 associates with and inhibits Cdk2 activity, leading to restoration of Cdk2-cyclin E-associated kinase activity suppressed by TGF-β. Significantly, HGF was able to restore Cdk6 expression and the Cdk2-associated kinase activities and cell proliferation in cells that were already growth arrested by TGF-β.

Growth factor interactions can be integrated by intracellular signaling pathways. Epidermal growth factor and HGF can antagonize the effects of bone morphogenetic protein by inducing phosphorylation of Smad1 via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated pathway. Phosphorylation leads to the inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein signaling (23), suggesting that opposing signals are modulated at the level of Smad proteins. Smad1 is not involved in TGF-β signaling (28), but similar mechanisms utilizing Smad2 and Smad3 could affect the ability of HGF to alter the growth inhibitory effect by TGF-β. Indeed, recent work shows that HGF can phosphorylate and activate Smad2, although to a lesser extent than can TGF-β (8). Our data, however, indicate that HGF does not inhibit, nor act synergistically with, TGF-β, because HGF does not alter the level of induction of p15 or extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin and thrombospondin (49) or PAI-1 (not shown) by TGF-β. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that HGF does not interfere, in general, with the TGF-β signal transduction pathways but that the signals involving growth regulation are integrated at the level of Cdk complexes.

This is the first study in which the regulation of endogenous p15 protein by TGF-β has been detected in Mv1Lu cells. The findings correlate with prior observations of increases in p15 mRNA by TGF-β in Mv1Lu and HaCaT human keratinocyte cells (16, 41) and p15 protein in HMEC human mammary epithelial cells (43). TGF-β enhanced the association of endogenous p15 with Cdk6 complexes, but the induction of p15 and its association with Cdk6 was not prevented by HGF. Accordingly, cyclin D2-associated Rb kinase activity was decreased by TGF-β and by concomitant treatment with TGF-β and HGF. Interestingly, TGF-β was found to decrease the expression of Cdk6 and its association with cyclin D2, both of which were prevented by HGF. A similar decrease in Cdk6 by TGF-β was found in metabolically labeled Mv1Lu cells (Fig. 3B) (41). The restoration of Cdk6 expression in cells treated with both growth factors correlated with the partial rescue of cyclin D2-associated kinase activity towards GST-Rb. This suggests that though p15 induction is unperturbed in cells treated with both growth factors and it avidly forms complexes with Cdk6, its levels are not high enough to fully prevent the activity of Cdk6-cyclin D2 complexes. The observed decrease in cyclin D2-activity may be attributed to partial inhibition of a fraction of Cdk6 by p15. In addition, the levels of p15 may not be sufficient to sequester all Cdk6 present in the cells. This in turn leads to the presence of active Cdk6-cyclin D2 complexes that can harvest p27 from binding to Cdk2. Thus, the decrease in Cdk6 expression may contribute importantly to the induction, maintenance, and adaptation of cells to TGF-β-mediated growth arrest.

Cyclin E and Cdk2 protein levels per se were unaffected by growth factor treatments. Kinase assays of TGF-β-treated cells showed that Cdk2 and cyclin E-associated activities were decreased, while HGF rescued these TGF-β-mediated effects. This finding is in line with the observed phosphorylation status of pRb and with the notion that there were fewer cells in G1 in the TGF-β- and HGF-treated population than in TGF-β-treated cells. TGF-β decreased the amount of the faster-migrating form of Cdk2, and HGF counteracted this effect. The TGF-β-mediated decrease in the faster-migrating form of Cdk2 is in accordance with earlier studies (22, 41, 47). The possibility remains that the decrease in the amount of active Cdk2 could be associated with modulation of CAK activity in growth factor-treated cells. Regulation of endogenous Cdk7-cyclin H activity by TGF-β and HGF was not observed in our study (data not shown), but this does not exclude the presence of other uncharacterized CAKs.

As shown earlier for TGF-β (40, 41), total p27 levels were not affected either by TGF-β or by HGF. Instead, as shown by the immunodepletion assay with p27 antibodies, TGF-β enhanced the association of p27 with Cdk2 and cyclin E complexes and HGF prevented this interaction partially, suggesting that less p27 is associated with the Cdk2-cyclin E complex in cells treated with both growth factors (Fig. 7B). Further, the immunodepletion assay suggests that the kinase activity of Cdk2-cyclin E complexes devoid of p27 may be sufficient for cellular proliferation. Though the binding of p27 to the Cdk2-cyclin E complex is generally thought to inhibit kinase activity, p27 itself and its association with the complex is under modulation. For example, it has been suggested that Myc activates Cdk2-associated kinase activity by phosphorylation of p27, resulting in enhanced p27 degradation (33), and by inhibition of p27 binding to newly formed Cdk2-cyclin E complexes (36). Additionally, the viral oncoproteins E1A and E7 bind and sequester p27 from Cdk2-cyclin E complexes, leading to activation of the complex (27, 54). Though we have no direct evidence that HGF causes alternative regulation of p27 protein levels, we cannot exclude the possibility that upon HGF treatment p27 loses high-affinity binding to Cdk2-cyclin E or that the steric complex between p27, Cdk2, and cyclin E would be in a conformation facilitating activation of Cdk2 kinase activity.

Based on our results, we suggest that HGF modifies the TGF-β response by regulation of Cdk6 complexes, thus also affecting the activity of Cdk2 complexes, and that these modifications serve as means of hindering the growth inhibition exerted by TGF-β. Firstly, HGF prevents a decrease in Cdk6 but not an increase in p15 by TGF-β. Though the level of p15 is increased, it may not be sufficient to sequester all Cdk6 present in the cells, and active Cdk6-cyclin D2 complexes can harvest p27 from binding to Cdk2. The observed decrease in cyclin D2 activity may also be attributed to partial inhibition of a fraction of Cdk6 by p15. Secondly, HGF could relieve the TGF-β growth arrest by directly modulating Cdk2 kinase activity or the association of p27 with the kinase complex. However, we cannot rule out the possibilities that the HGF effect is not solely mediated by the alternative regulation of Cdk6 and that the release of Cdk2-cyclin E activity from suppression by p27 occurs through increased binding of Cdk6 complexes to p27. Here we have addressed the regulation of only a set of kinases and their inhibitors, based on their abundance in Mv1Lu cells. We cannot exclude the possibility that regulation of other kinases, cyclin partners, or inhibitors contributes to some of the observed effects. The hypothesis that TGF-β growth arrest involves additional mechanisms besides action of p15 and p27 CDKIs is strengthened by genetic and biochemical evidence, as cells from mice nullizygous for p27 (34) and mammary epithelial cells that lack p15 are growth inhibited by TGF-β (18). These models imply that for TGF-β growth suppression to take place, TGF-β must affect multiple cell cycle components. Our data indicate that regulation of Cdk6 levels is important for TGF-β growth inhibition. The decrease in Cdk6 can contribute to TGF-β growth arrest by downregulation of cyclin D2-associated kinase activity and by ensuring that sufficient amounts of p27 are liberated to associate with and inhibit Cdk2-cyclin E activity. Furthermore, the present data indicate that positive and negative growth signals are integrated at the level of Cdk regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joan Massagué and Jiri Bartek for generous gifts of antibodies, Tomi Mäkelä for critical review of the manuscript, and Annamari Heiskanen for fine technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, the Ida Montin Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, Sigrid Juselius Foundation, Finnish Cancer Foundation, and Biocentrum Helsinki.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama T, Ohuchi T, Sumida S, Matsumoto K, Toyoshima K. Phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein by Cdk2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7900–7904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W. Molecular aspects of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:511–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussolino F, Di Renzo M F, Ziche M, Bocchietto E, Olivero M, Naldini L, Gaudino G, Tamagnone L, Coffer A, Comoglio P M. Hepatocyte growth factor is a potent angiogenic factor which stimulates endothelial cell motility and growth. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:629–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell-Crowley L, Harper J W, Goodrich D W. Cyclin D1/Cdk4 regulates retinoblastoma protein-mediated cell cycle arrest by site-specific phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:287–301. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover C M, Hsieh S J, Tran S H, Hallden G, Kim G S, Bjeldanes L F, Firestone G L. Indole-3-carbinol inhibits the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase-6 and induces a G1 cell cycle arrest of human breast cancer cells independent of estrogen receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3838–3847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datto M B, Li Y, Panus J F, Howe D J, Xiong Y, Wang X F. Transforming growth factor-β induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5545–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Caestecker M P, Parks W T, Frank C J, Castagnino P, Bottaro D P, Roberts A B, Lechleider R J. Smad2 transduces common signals from receptor serine-threonine and tyrosine kinases. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1587–1592. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dulic V, Lees E, Reed S I. Association of human cyclin E with a periodic G1-S phase protein kinase. Science. 1992;257:1958–1961. doi: 10.1126/science.1329201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewen M E, Sluss H K, Whitehouse L L, Livingston D M. TGF-β inhibition of Cdk4 synthesis is linked to cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1993;74:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabrielli B G, Lee M S, Walker D H, Piwnica-Worms H, Maller J L. Cdc25 regulates the phosphorylation and activity of the Xenopus Cdk2 protein kinase complex. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18040–18046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graña X, Reddy E P. Cell cycle control in mammalian cells: role of cyclins, cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), growth suppressor genes and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) Oncogene. 1995;11:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu Y, Rosenblatt J, Morgan D O. Cell cycle regulation of CDK2 activity by phosphorylation of Thr160 and Tyr15. EMBO J. 1992;11:3995–4005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haapajärvi T, Kivinen L, Pitkänen K, Laiho M. Cell cycle dependent effects of U.V.-radiation on p53 expression and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Oncogene. 1995;11:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall M, Bates S, Peters G. Evidence for different modes of action of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: p15 and p16 bind to kinases, p21 and p27 bind to cyclins. Oncogene. 1995;11:1581–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannon G J, Beach D. p15ink4b is a potential effector of TGF-β-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrera R E, Sah V P, Williams B O, Mäkelä T P, Weinberg R A, Jacks T. Altered cell cycle kinetics, gene expression, and G1 restriction point regulation in Rb-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2402–2407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iavarone A, Massagué J. Repression of the CDK activator Cdc25A and cell-cycle arrest by cytokine TGF-β in cells lacking the CDK inhibitor p15. Nature. 1997;387:417–422. doi: 10.1038/387417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeffrey P D, Russo A A, Polyak K, Gibbs E, Hurwitz J, Massagué J, Pavletich N P. Mechanism of CDK activation revealed by the structure of a cyclinA-CDK2 complex. Nature. 1995;376:313–320. doi: 10.1038/376313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert S W, Ewen M E, Sherr C J. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev. 1993;7:331–342. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingsley D M. The TGF-β superfamily: new members, new receptors, and new genetic tests of function in different organisms. Genes Dev. 1994;8:133–146. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koff A, Ohtsuki M, Polyak K, Roberts J M, Massagué J. Negative regulation of G1 in mammalian cells: inhibition of cyclin E-dependent kinase by TGF-β. Science. 1993;260:536–539. doi: 10.1126/science.8475385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kretzschmar M, Doody J, Massagué J. Opposing BMP and EGF signalling pathways converge on the TGF-β family mediator Smad1. Nature. 1997;389:618–622. doi: 10.1038/39348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laiho M, DeCaprio J A, Ludlow J W, Livingston D M, Massagué J. Growth inhibition by TGF-β linked to suppression of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Cell. 1990;62:175–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C Y, Suardet L, Little J B. Potential role of WAF1/Cip1/p21 as a mediator of TGF-β cytoinhibitory effect. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4971–4974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundberg A S, Weinberg R A. Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distinct cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:753–761. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mal A, Poon R Y C, Howe P H, Toyoshima H, Hunter T, Harter M L. Inactivation of p27Kip1 by the viral E1A oncoprotein in TGFβ-treated cells. Nature. 1996;380:262–265. doi: 10.1038/380262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massagué J. TGF-β signaling: receptors, transducers, and Mad proteins. Cell. 1996;85:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsushime H, Quelle D E, Shurtleff S A, Shibuya M, Sherr C J, Kato J Y. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millar J B, McGowan C H, Lenaers G, Jones R, Russell P. p80cdc25 mitotic inducer is the tyrosine phosphatase that activates p34cdc2 kinase in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1991;10:4301–4309. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montesano R, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Orci L. Identification of a fibroblast-derived epithelial morphogen as hepatocyte growth factor. Cell. 1991;67:901–908. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan D O. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller D, Bouchard C, Rudolph B, Steiner P, Stuckmann I, Saffrich R, Ansorge W, Huttner W, Eilers M. Cdk2-dependent phosphorylation of p27 facilitates its Myc-induced release from cyclin/Cdk2 complexes. Oncogene. 1997;15:2561–2576. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakayama K, Ishida N, Shirane M, Inomata A, Inoue T, Shishido N, Horii I, Loh D Y, Nakayama K. Mice lacking p27Kip1 display increased body size, multiple organ hyperplasia, retinal dysplasia, and pituitary tumors. Cell. 1996;85:707–720. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohtsubo M, Roberts J M. Cyclin-dependent regulation of G1 in mammalian fibroblasts. Science. 1993;259:1908–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.8384376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Roger I, Solomon D L, Sewing A, Land H. Myc activation of cyclin/Cdk2 kinase involves induction of cyclin E gene transcription and inhibition of p27Kip1 binding to newly formed complexes. Oncogene. 1997;14:2373–2381. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pines J. Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases: theme and variations. Adv Cancer Res. 1995;66:181–212. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polyak K, Kato J Y, Solomon M J, Sherr C J, Massagué J, Roberts J M, Koff A. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-β and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 1994;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polyak K, Lee M H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Koff A, Roberts J M, Tempst P, Massagué J. Cloning of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a potential mediator of extracellular antimitogenic signals. Cell. 1994;78:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynisdóttir I, Massagué J. The subcellular locations of p15Ink4b and p27Kip1 coordinate their inhibitory interactions with Cdk4 and Cdk2. Genes Dev. 1997;11:492–503. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynisdóttir I, Polyak K, Iavarone A, Massagué J. Kip/Cip and Ink4 Cdk inhibitors cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-β. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1831–1845. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo A A, Jeffrey P D, Patten A K, Massagué J, Pavletich N P. Crystal structure of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor bound to the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Nature. 1996;382:325–331. doi: 10.1038/382325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandhu C, Garbe J, Bhattacharya N, Daksis J, Pan C-H, Yaswen P, Koh J, Slingerland J M, Stampfer M R. Transforming growth factor β stabilizes p15INK4B protein, increases p15INK4B-cdk4 complexes, and inhibits cyclin D1-cdk4 association in human mammary epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2458–2467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherr C J. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherr C J. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherr C J, Roberts J M. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slingerland J M, Hengst L, Pan C H, Alexander D, Stampfer M R, Reed S I. A novel inhibitor of cyclin-Cdk activity detected in transforming growth factor β-arrested epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3683–3694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solomon M J, Lee T, Kirschner M W. Role of phosphorylation in p34cdc2 activation: identification of an activating kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:13–27. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taipale J, Keski-Oja J. Hepatocyte growth factor releases epithelial and endothelial cells from growth arrest induced by transforming growth factor-β1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4342–4348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taipale J, Saharinen J, Keski-Oja J. Extracellular matrix associated transforming growth factor-β: role in cancer cell growth and invasion. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;75:87–133. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van den Eijnden-van Raaij A J, Koornneef I, van Zoelen E J. A new method for high yield purification of type β transforming growth factor from human platelets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157:16–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinberg R A. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zarkowska T, Mittnacht S. Differential phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein by G1/S cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12738–12746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zerfass-Thome K, Zwerschke W, Mannhardt B, Tindle R, Botz J W, Jansen-Dürr P. Inactivation of the Cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene. 1996;13:2323–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu L, Harlow E, Dynlacht B D. p107 uses a p21Cip1-related domain to bind cyclin/Cdk2 and regulate interactions with E2F. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1740–1752. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]