INTRODUCTION:

Observational data suggest there may be an association between rituximab and severe COVID-19 outcomes.1 2 3 Anti-CD20 therapies impair humoral response, theoretically increasing the risk for prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection and shedding, as well as subsequent reinfection. Herein, we report a patient with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) being treated with rituximab who appears to have developed recurrent SARS-CoV-2 infections in the setting of high-risk employment, and, upon recovery ultimately had no detectable SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies. This case highlights a potential risk of rituximab in rheumatic disease patients, which will become especially relevant as rituximab may impair immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

CASE:

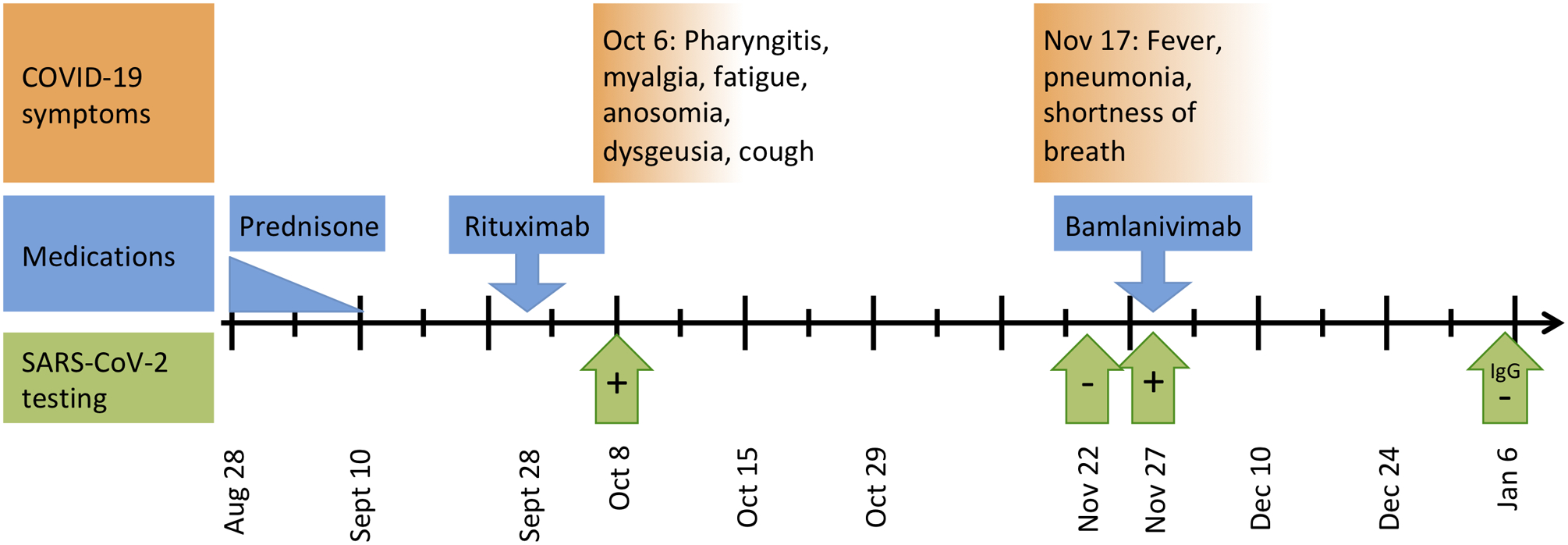

A woman in her 30s with a history of limited GPA on rituximab developed COVID-19 twice. (Figure 1) GPA manifestations have included erosive sinusitis, otitis, saddle nose deformity, and orbital pseudotumor. She started rituximab in February of 2019. The most recent dose of rituximab 1000 mg was given on September 28th 2020. On August 14th, a disease flare was treated with a 3-week prednisone taper, which completed approximately 4 weeks prior to COVID-19 infection. She works in an assisted living facility with ongoing staff and resident COVID-19 cases.

Figure 1:

Timeline of COVID-19 symptoms, testing, and relevant drugs: Timeline shown from August 28, 2020 until January 6, 2021. After the October 6th infection, COVID-19 symptoms completely recovered with the exception of ongoing fatigue. SARS-CoV-2 testing includes: October 8th positive rapid antigen assay, November 22nd negative rapid molecular test (®Abbot ID NOW), November 27th positive rapid molecular test (®BioFire FilmArray), and on January 6th a negative IgG test.

On October 6th she developed pharyngitis, myalgia, fatigue, anosomia, dysgeusia, and a mild cough. She was afebrile and her oxygenation was 99% on room air. A rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen immunoassay on October 8th was positive. Over the next two weeks she fully recovered except for residual fatigue. After a 2-week quarantine she returned to work.

On November 17th she developed a severe cough, deep lung pain, fevers of 40.5°C, and shortness of breath. Respiratory symptoms were significantly more severe than her initial infection. On November 22nd a rapid SARS-CoV-2 test (®Abbot ID NOW) was negative. A chest x-ray showed bilateral groundglass opacities. Symptoms progressively worsened, and on November 27th a rapid SARS-CoV-2 test (®BioFire FilmArray) was positive. Her oxygen saturation was 94% on room air. She was treated with a single infusion of bamlanivimab (monoclonal antibody targeting SARS-CoV-2). Over the next several weeks her symptoms gradually improved. COVID-19 IgG levels checked on January 6th, 2021 (> 1 month after bamlanivimab) were negative.

DISCUSSION:

Her near-complete recovery after her initial infection, the time course, ongoing high-risk employment, negative rapid test at the beginning of her second symptom onset, and the ultimate lack COVID-19 IgG lead us to suspect that these were two separate infections, in which she developed insufficient immune response due to rituximab. However, it is also possible this represented a single prolonged infection with a period of asymptomatic disease. To our knowledge, only one case has previously reported a rituximab-treated patient developing a second SARS-CoV-2 infection; that patient also received cytarabine and dasatinib for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and the authors suspected reactivation.4

Limitations in our report include the lack of sequencing data (samples had been discarded), and the reliance on rapid SARS-CoV-2 testing. However, rapid tests are typically highly specific.5 GPA flare was considered as a cause of her illness, however, the positive SARS-CoV-2 tests and improvement without immunosuppression argue against this. Corticosteroids are a known risk factor for severe COVID-19,6 however, she had not taken prednisone in the approximately 4 weeks preceding initial infection. It is not known whether bamlanivimab impacts SARS-CoV-2 IgG development.

Anti-CD20 therapies prevent the formation of protective antibodies leading to increased risk of reinfection or reactivation with SARS-CoV-2. This has implications for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, which may not be as effective in rituximab-treated patients. Clinicians using rituximab may consider delaying rituximab to allow for vaccination,7 although in life-threatening diseases this is not always possible. Lastly, further studies are necessary to determine the exact effect of anti-CD20 therapies on the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, and whether delayed dosing improves vaccine immunogenicity.

Acknowledgements:

We wish to acknowledge the patient for her generosity in allowing us to present her case.

Funding:

MAF is funded by NIH/NCATS KL2TR002370, and the OHSU WheelsUp program. KLW is funded by research grants from BMS and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

MAF has no disclosures. KLW receives consulting fees from : Pfizer, AbbVie, Union Chimique Belge (UCB), Eli Lilly & Company, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Roche, Gilead, BMS, Regeneron, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Novartis.

Patient and Public Involvement:

This work did not include patient or public involvement.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Schulze-Koops H, Krueger K, Vallbracht I, et al. Increased risk for severe COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases treated with rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis 2020. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218075 [published Online First: 2020/06/28] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loarce-Martos J, Garcia-Fernandez A, Lopez-Gutierrez F, et al. High rates of severe disease and death due to SARS-CoV-2 infection in rheumatic disease patients treated with rituximab: a descriptive study. Rheumatol Int 2020;40(12):2015–21. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04699-x [published Online First: 2020/09/19] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuda H, Tsukune Y, Watanabe N, et al. Persistent COVID-19 Pneumonia and Failure to Develop Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies During Rituximab Maintenance Therapy for Follicular Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2020;20(11):774–76. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.08.017 [published Online First: 2020/09/17] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lancman G, Mascarenhas J, Bar-Natan M. Severe COVID-19 virus reactivation following treatment for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00968-1 [published Online First: 2020/10/04] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson KE, Caliendo AM, Arias CA, et al. The Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19: Molecular Diagnostic Testing. Clin Infect Dis 2021. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab048 [published Online First: 2021/01/23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79(7):859–66. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871 [published Online First: 2020/05/31] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman MA, Winthrop KL. Vaccines and Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: Practical Implications for the Rheumatologist. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2017;43(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]