Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study is to estimate the prevalence of self-reported mental health symptoms and treatment utilization in a national sample of community college students and to draw comparisons to a sample of students at four-year institutions.

Methods:

Data come from the Healthy Minds Study (2016–2019), an annual cross-sectional survey. The sample includes 10,089 students from 23 community colleges and 95,711 students from 133 four-year institutions. Outcomes fall into two broad categories: (1) mental health symptom prevalence based on validated screening tools; and (2) service utilization (therapy, psychotropic medication). Analyses are weighted using survey non-response weights.

Results:

Overall prevalence rates are comparably high in the full sample of community college and four-year students, with just over 50% of each group meeting criteria for one or more mental health problem. Analyses by age group reveal prevalence is significantly higher for community college students aged 18–22 relative to their same-aged peers at four-year campuses. Community college students, particularly those from traditionally-marginalized backgrounds, are significantly less likely to have used services compared to students on four-year campuses. Financial stress is a strong predictor of mental health outcomes, and cost is the most salient treatment barrier in the community college sample.

Conclusions:

This is the largest known study to report on the mental health needs of community college students in the U.S. Findings have important implications for campus policies and programs as well as future research to advance equity in mental health and other key outcomes, such as college persistence and retention.

Introduction

U.S. colleges and universities are facing what many have referred to as a “campus mental health crisis” (1,2). Recent years have been marked by high and rising prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems in college populations (3). A substantial body of research has focused on the mental health needs of students on four-year campuses. In the U.S., 34% of undergraduates (defined as students in “a 4- or 5-year bachelor’s program, associate’s program, or vocational or technical program below the baccalaureate”) are enrolled in community colleges (CC) (4). Furthermore, 49% of students who completed a degree at a four-year college had enrolled in CC within the previous 10 years (5). Yet, even as research on college mental health has proliferated, gaps in knowledge around CC mental health remain.

For numerous reasons, it is important to understand the unique mental health needs of CC students, including as part of a broader dialogue about equity and college persistence. Students enroll in CC for a range of reasons, including academic preparedness, cost, and geographic proximity. Mental health may affect enrollment decisions, academic performance, retention, and other long-term outcomes. Just 20% of first-time CC students complete a credential within 150% of the intended timeframe (6); eight years after beginning CC, 43% are no longer enrolled nor have they earned any credential (7). Mental health is rarely mentioned among factors affecting CC persistence, even though mental health challenges are known to be strong predictors of adverse academic outcomes. For example, research with students from four-year institutions has found depression to be associated with a two-fold increase in the likelihood of dropping out of college (8).

A limited body of extant research on CC mental health has focused primarily on treatment access. A survey of 30,000 California public college and university students found CC students were less likely to receive treatment compared to their four-year counterparts (9). This is problematic, as CCs serve a higher proportion of students of color, students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and students who work full time (10). In other words, CCs are serving a student body known to have mental health treatment barriers (11). Further examination of CC mental health is necessary in order to quantify the magnitude of symptom prevalence and service use in this diverse population.

To help fill this gap, we use national data from the Healthy Minds Study (HMS) to examine mental health and service utilization in a sample of over 10,000 CC students. Two prior peer-reviewed studies have used a modified version of the HMS instrument (as part of a separate study excluding four-year campuses) to examine outcomes for veteran and civilian CC students in Arkansas (12,13); there is also one non-peer-reviewed report with results from a modified version of HMS conducted on CCs (14). This is the first analysis of national HMS data to focus on the full CC student population, to make comparisons to a four-year sample, and one of the largest known studies to focus on mental health in CC populations. Importantly, the present study takes a population-level approach, examining outcomes in a randomly selected sample. This has advantages over studies that rely on clinical samples, and offers new knowledge about population-level prevalence and the degree to which CC students who screen positive on validated screening tools are and are not seeking care. Leveraging the large-scale HMS data, we also examine individual-level predictors of mental health and service use, focusing on variations by age, race/ethnicity, financial stress, and other key characteristics across which outcomes have been shown to vary in adolescent and young adult populations (9,11). Our focus on age, race/ethnicity, and financial stress is further motivated by known demographic differences in enrollment across institutions of higher education, namely that CC students are, on average, older than students at four-year universities and that a higher proportion are students of color and students from low-income backgrounds (10). Findings have implications for campus policies as well as future efforts to advance equity in mental health and other key outcomes, such as persistence and retention.

Methods

Data

Data come from the national Healthy Minds Study, an annual cross-sectional survey examining mental health in college populations (15). The present study analyzes six semesters of data (fall 2016-spring 2019), which include 23 CCs and 133 four-year institutions. Campuses voluntary elect to participate in HMS, which is available for implementation at all types of postsecondary institutions. Though non-random, the sites are diverse across numerous campus characteristics, including enrollment, graduation rates, and geographic region. Previous HMS papers have reported on characteristics of participating four-year institutions (15); the 23 CC sites, all public, are located in 7 of 9 U.S. census regions (unrepresented are West North Central and South Atlantic). In the CC institutional sample, enrollment ranges from <1,000 to >17,000 students. The percentage of students of color ranges from 11–87%, with the majority of schools (N=14) having 30–40% students of color. Graduation rates (degree completion within 150% of normal time) range from 11–55%, with the majority (N=14) between 20–40%. Funding from state governments ranges from 7–50% of institutional finances; institutional characteristics drawn from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (16).

At campuses with >4,000 students, a random sample of 4,000 degree-seeking students was invited to HMS; at smaller institutions, all were invited. The only exclusion criterion was students had to be at least 18 years of age. Within HMS, students are asked to report degree program, with “associate’s” and “bachelor’s” being two responses; other categories were graduate programs (e.g., MD, PhD) not offered at CCs. Certificate programs, a common offering at CCs, were not an option in the survey. To compare four-year and CC campuses, the analytic sample is restricted to students in associate’s or bachelor’s programs.

HMS is a mobile survey and recruitment is conducted by email. Students were presented with an informed consent page and agreed to the terms of participation before entering the Qualtrics survey. Students were informed of their eligibility for one of 12 cash prizes totaling $2,000 annually (two $500, 10 $100 gift cards). All students were eligible for incentives, which were not contingent on participation. Response rates were 23% in 2016–2017 and 2017–2018, and 16% in 2018–2019. HMS was approved by institutional review boards on all campuses, and covered by an NIH Certificate of Confidentiality.

Non-response analysis:

To adjust for potential differences between responders and non-responders, the study team constructed sample probability weights. Administrative data were obtained from institutions, including sex, race/ethnicity, and grade point average. These were used to construct weights, equal to 1 divided by the estimated probability of response. Thus, weights are larger for respondents with underrepresented characteristics, ensuring estimates are representative of the full population in terms of these known characteristics.

Measures

Prevalence:

We examine six prevalence outcomes; binary outcomes are used because most have been validated based on standard cutoffs and reported in prior studies (3,17). Symptoms of depression over the past two weeks are examined using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (18). Across settings and populations, the PHQ-9 has been validated as internally consistent and highly correlated with diagnosis (19). The standard cutoff of ≥10 is used. Symptoms of anxiety over the past two weeks are measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale (20). The standard cutoff of ≥10 is used, which has been shown to have high sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%) (20). Symptoms of eating disorders are assessed using the SCOFF (21), with ≥2 constituting a positive screen. The following item is used to assess non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI): “This question asks about ways you may have hurt yourself on purpose, without intending to kill yourself. In the past year, have you ever done any of the following intentionally?” Students were instructed to “select all that apply;” we created a variable of any NSSI. A single question, originally developed for the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (22), is used to assess suicidal ideation: “In the past year, did you ever seriously think about attempting suicide?” Responses are “yes” and “no.” Finally, we created a variable of one or more mental health problems, defined as a positive PHQ-9, GAD-7, or SCOFF screen or past-year NSSI or suicidal ideation.

Academic performance:

Students were asked: “In the past 4 weeks, how many days have you felt that emotional or mental difficulties have hurt your academic performance?” Students are categorized as 0 vs. 1 or more days.

Service use:

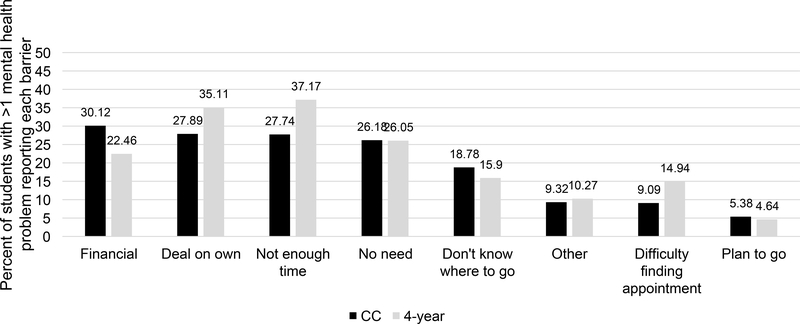

We examine past-year therapy and psychotropic medication use among students with one or more mental health problems (as defined above). Among students who sought services, we report location (on vs. off campus). We also examine treatment barriers; students were asked why they had not received treatment or received fewer services than they otherwise would have, and were instructed to “select all that apply” from the options in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Barriers to Mental Health Service Use among Students with >1 Mental Health Problem: Community College vs. 4-Year Sample.

Notes: Figure values are weighted percentages among students with “>1 mental health problem,” defined as a positive screen for depression (PHQ-9>10), positive screen for anxiety (GAD-7>10), positive screen for an eating disorder (SCOFF>2), any past-year non-suicidal self-injury, and/or any past-year suicidal ideation. “CC” is community college.

Individual characteristics:

Within the CC sample, we explore variations by: age; gender identity (female, male, transgender/gender non-conforming (TGNC)); race/ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Latinx, Arab American, other, multiracial); sexual orientation (heterosexual vs. lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer (LGBQ)); and current and past financial stress.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses are intended to elucidate variations in mental health and service use among CC students relative to students at four-year campuses and by individual characteristics within the CC sample. Variations within the CC sample are presented in an online supplement. Differences in the Results section are significant at p<0.001. In text, we report weighted percentages, unweighted sample sizes, odds ratios (OR), t statistics, degrees of freedom (df), and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2 and weighted using the sample weights described.

Results

Sample (Table 1):

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N=105,800)

| Community College Students (N=10,089) | 4-Year Students (N=95,711) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %/mean | n | %/mean | ||

| Age | |||||

| mean ± SD | 26.1 ± 0.12 | 21.3 ± 0.02 | <.001 | ||

| 18–22 | 5,113 | 52.2 | 83,175 | 85.1 | <.001 |

| 23–29 | 2,382 | 23.1 | 8,540 | 10.2 | <.001 |

| 30+ | 2,594 | 24.8 | 3,996 | 4.7 | <.001 |

| Gender identity | |||||

| Female | 7,180 | 57.2 | 64,764 | 56.2 | .2 |

| Male | 2,704 | 40.8 | 28,305 | 40.5 | .7 |

| TGNC | 205 | 1.9 | 2,642 | 3.3 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 6,387 | 60.7 | 62,124 | 63.6 | <.001 |

| Black | 875 | 8.9 | 5,208 | 7.6 | .001 |

| Asian | 481 | 4.1 | 10,147 | 9.8 | <.001 |

| Latinx | 1,081 | 13.4 | 5,908 | 6.2 | <.001 |

| Multiracial | 898 | 9.2 | 9,663 | 9.7 | .2 |

| Other | 283 | 3.1 | 1,461 | 1.8 | <.001 |

| Arab/Arab American | 84 | 0.7 | 1,200 | 1.3 | <.001 |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 8,221 | 83.5 | 76,585 | 79.3 | <.001 |

| LGBQ | 1,702 | 16.5 | 18,683 | 20.7 | |

| Current financial stress | |||||

| Always | 2,198 | 21.3 | 12,040 | 14.2 | <.001 |

| Often | 2,838 | 27.7 | 22,182 | 24.2 | <.001 |

| Sometimes | 3,507 | 35.6 | 33,479 | 35.1 | .4 |

| Rarely | 1,180 | 12.3 | 20,038 | 19.6 | <.001 |

| Never | 285 | 3.2 | 7,157 | 6.9 | <.001 |

| Past financial stress | |||||

| Always | 1,783 | 18.0 | 7,552 | 8.9 | <.001 |

| Often | 2,089 | 21.5 | 14,213 | 15.9 | <.001 |

| Sometimes | 2,885 | 28.7 | 24,693 | 26.8 | .003 |

| Rarely | 2,211 | 21.8 | 29,960 | 30.6 | <.001 |

| Never | 1,038 | 10.0 | 18,461 | 17.9 | <.001 |

Notes: Values are unweighted sample numbers (n) and weighted percentages except for age (mean, standard deviation (SD)). p-values based on unadjusted linear and logistic regressions. “TGNC” is transgender and gender nonconforming. “LGBQ” is lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer.

The sample is comprised of 10,089 students from 23 CCs and 95,711 students from 133 four-year institutions. Gender was similar in the two samples, with 56–57% identifying as female and 40% as male. Relative to four-year campuses, CC students are significantly older (26 vs. 21 years, t=37.77, df=105,777, 95% CI=4.49–4.98, p<0.001), and a higher proportion are Latinx: 13.4% (N=1,081) vs. 6.2% (N=5,908) (OR=2.35, t=18.94, df=105,777, 95% CI=2.15–2.56, p<0.001). CC students report higher levels of current and past financial stress.

Prevalence (Table 2):

Table 2.

Mental Health Symptom Prevalence: Community College vs. 4-Year Sample

| Community College | 4-Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Overall | |||||

| Depression | 3,568 | 37.9 | 31,877 | 37.3 | .4 |

| Anxiety | 3,112 | 33.0 | 27,125 | 31.3 | .01 |

| Eating disorder | 2,433 | 24.5 | 22,874 | 24.8 | .7 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 1,871 | 19.7 | 22,030 | 26.6 | <.001 |

| Suicidal ideation | 1,368 | 14.7 | 12,229 | 14.7 | .96 |

| ≥1 mental health problem | 5,488 | 53.5 | 52,575 | 55.0 | .04 |

| Hurt academic performance | 7,438 | 72.9 | 74,115 | 78.0 | <.001 |

| Age 18–22 | |||||

| Depression | 2,059 | 42.0 | 27,567 | 37.3 | <.001 |

| Anxiety | 1,766 | 36.3 | 23,548 | 31.4 | <.001 |

| Eating disorder | 1,388 | 27.5 | 20,170 | 25.2 | .007 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 1,280 | 27.1 | 19,973 | 28.0 | .3 |

| Suicidal ideation | 847 | 18.2 | 10,801 | 15.0 | <.001 |

| ≥1 mental health problem | 3,087 | 58.1 | 45,958 | 55.3 | .005 |

| Hurt academic performance | 3,937 | 75.8 | 64,545 | 78.2 | .007 |

| Age 23–29 | |||||

| Depression | 873 | 39.8 | 3,241 | 41.5 | .3 |

| Anxiety | 789 | 35.4 | 2,708 | 34.4 | .6 |

| Eating disorder | 567 | 24.5 | 1,969 | 24.2 | .8 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 406 | 17.0 | 1,678 | 22.7 | <.001 |

| Suicidal ideation | 308 | 14.0 | 1,134 | 15.7 | .2 |

| ≥1 mental health problem | 1,336 | 55.6 | 4,883 | 57.8 | .2 |

| Hurt academic performance | 1,782 | 74.8 | 6,794 | 80.6 | <.001 |

| Age 30+ | |||||

| Depression | 636 | 28.0 | 1,069 | 28.5 | .7 |

| Anxiety | 557 | 24.0 | 869 | 22.0 | .2 |

| Eating disorder | 478 | 18.5 | 735 | 19.2 | .6 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 185 | 7.4 | 379 | 10.4 | .004 |

| Suicidal ideation | 213 | 8.3 | 294 | 8.4 | .9 |

| ≥1 mental health problem | 1,065 | 41.9 | 1,734 | 42.7 | .6 |

| Hurt academic performance | 1,719 | 65.1 | 2,776 | 69.1 | .01 |

Notes: Values are weighted percentages with unweighted sample numbers. “≥1 mental health problem” is a positive screen for depression (PHQ-9≥10), anxiety (GAD-7≥10), eating disorder (SCOFF≥2), past-year non-suicidal self-injury, and/or past-year suicidal ideation. p-values based on unadjusted logistic regressions.

Overall prevalence is similar in the CC and four-year samples, with over half meeting criteria for one or more mental health problems, roughly one-third screening positive for depression and for anxiety, and approximately 15% reporting suicidal ideation. Relative to their same-aged peers on four-year campuses, CC students aged 18–22 are more likely to screen positive for depression (OR=1.21, t=4.77, df=82,090, 95% CI=1.12–1.32, p<0.001) and anxiety (OR=1.25, t=5.28, df=81,139, 95% CI=1.15–1.35, p<0.001) as well as report suicidal ideation (OR=1.27, t=4.60, df=81,847, 95% CI=1.15–1.40, p<0.001).

Service use (Table 3):

Table 3.

Past-Year Service Use among Students with ≥1 Mental Health Problem: Community College (N=5,488) vs. 4-Year Sample (N=52,575)

| Community College | 4-Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Overall | |||||

| Therapy | 1,565 | 30.0 | 19,866 | 39.5 | <.001 |

| Psychotropic medication | 1,762 | 32.2 | 15,766 | 32.5 | .7 |

| On-campus service use | 263 | 5.4 | 11,678 | 23.4 | <.001 |

| Age 18–22 | |||||

| Therapy | 780 | 25.3 | 17,451 | 39.7 | <.001 |

| Psychotropic medication | 815 | 25.8 | 13,308 | 31.5 | <.001 |

| On-campus service use | 145 | 5.4 | 10,696 | 24.7 | <.001 |

| Age 23–29 | |||||

| Therapy | 400 | 33.3 | 1,705 | 36.3 | .2 |

| Psychotropic medication | 478 | 36.6 | 1,704 | 36.7 | .95 |

| On-campus service use | 64 | 6.1 | 800 | 17.4 | <.001 |

| Age 30+ | |||||

| Therapy | 385 | 39.5 | 710 | 43.2 | .2 |

| Psychotropic medication | 469 | 45.5 | 754 | 44.0 | .6 |

| On-campus service use | 54 | 4.6 | 182 | 10.0 | <.001 |

Notes: Values are weighted percentages with unweighted sample numbers among students with “≥1 mental health problem,” defined as a positive screen for depression (PHQ-9≥10), anxiety (GAD-7≥10), eating disorder (SCOFF≥2), past-year non-suicidal self-injury, and/or past-year suicidal ideation. On-campus service use is among students who used services. p-values based on unadjusted logistic regressions.

Among students with one or more reported mental health problems, CC students have lower rates of past-year therapy (30.0%, N=1,565, OR=.66, t=−9.49, df=56,199, 95% CI=.60-.72, p<0.001) relative to four-year students (39.5%, N=19,866). Medication use is similar in both groups, with roughly one-third reporting use. Just 5.4% of CC students (N=263) (OR=.19, t=−18.70, df=56,199, 95% CI=.16-.22, p<0.001) who used services did so on campus, compared to 23.4% at four-year institutions (N=11,678). Importantly, CC students ages 18–22 are less likely to use treatment: just 25.3% of 18–22-year-old CC students used therapy (N=780) (OR=.51, t=−11.88, df=47,521, 95% CI=.46-.57, p<0.001) and 25.8% used medication (N=815) (OR=.76, t=−4.93, df=46,234, 95% CI=.68-.84, p<0.001), compared to 39.7% (N=17,451) and 31.5% (N=13,308) of four-year students.

As shown in Figure 1, financial constraints are the most common treatment barrier among CC students (30.1%, N=1,693) and the fourth most common among four-year students (22.5%, N=10,961).

Within the CC sample (see online supplement), 56.6% of female (N=4,050) (OR=1.40, t=5.72, df=10,084, 95% CI=1.25–1.57, p<0.001) and 73.9% of TGNC students (N=160) (OR=3.04, t=5.29, df=10,084, 95% CI=2.01–4.58, p<0.001) meet criteria for one or more mental health problems relative to 48.2% of males (N=1,278). LGBQ students have higher prevalence for all outcomes, with 69.8% of LGBQ (N=1,227) and 50.6% of heterosexual students (N=4,196) (OR=.44, t=−10.43, df=9,918, 95% CI=.38-.52, p<0.001) meeting criteria for one or more problems. Financial stress is associated with higher prevalence: 70.4% who report their current financial situation as “always stressful” (N=1,592) (OR=4.05, t=7.44, df=10,003, 95% CI=2.80–5.86, p<0.001) and 61.9% as “often stressful” (N=1,744) (OR=2.77, t=5.56, df=10,003, 95% CI=1.93–3.96, p<0.001) meet criteria for one or more problems, relative to 37.0% who report “never stressful” (N=109). Less than half (43.3%) of the “never stressful” group (N=122) report academic impairment compared to 87.3% among “always stressful” (N=1,915) (OR=9.02, t=11.29, df=9,880, 95% CI=6.16–13.21, p<0.001) and 82.4% among “often stressful” (N=2,335) (OR=6.12, t=9.80, df=9,880, 95% CI=4.26–8.79, p<0.001). Similar patterns are revealed for past financial stress. For service use, there are significant variations by race/ethnicity. Notably, one-third of White students (33.3%, N=1,101) used therapy compared to 6.8% of Arab American students (N=5) (OR=.13, t=−4.04, df=5,257, 95% CI=.05-.35, p<0.001). Similarly, just 18.2% of Latinx students (N=120) (OR=.36, t=−7.08, df=5,116, 95% CI=.28-.48, p<0.001) used medication compared to 37.9% of White students (N=1,314).

Discussion

While much attention has been paid to student mental health at four-year institutions, findings from this study underscore that the “campus mental health crisis” extends to CCs. Overall, we found: (1) comparably high self-reported prevalence between the full sample of CC and four-year students, with over 50% of each group meeting criteria for one or more mental health problem; (2) significantly higher prevalence for CC students aged 18–22 relative to their same-aged peers at four-year campuses; (3) significantly lower therapy use among CC students; and (4) significant disparities across CC student characteristics, with those from traditionally-marginalized backgrounds having higher prevalence and lower service utilization.

Consistent with past research (23,24), financial stress is a contributor to CC mental health in this sample. Financial stress was also associated with academic impairment due to mental health, a finding that underscores mental health as a potential mechanism driving low persistence and retention and inequalities therein. Collectively, findings point to a need to assess financial stress as part of the full picture of student wellbeing and academic persistence, and to consider high levels of financial stress as a risk factor not only for retention but also mental health. Within U.S. higher education, CCs continue to be underfunded relative to four-year institutions (25). Yet given the link between student mental health and academic outcomes, including college graduation (8), there is a strong economic case for federal, state, and local investments in CC mental health through programs and services aimed at delivering treatment and prevention, as well as social support services that could reduce financial stress.

Financial constraints were the most common treatment barrier in the CC sample. This adds to the limited research comparing CC students to those at four-year colleges (9, 26). Differences between rates of therapy and medication were notable, and may suggest CC students are relying on more accessible and affordable treatment. While it is well-established that antidepressants can be equally efficacious to evidence-based psychotherapies (27, 28), and while easier for many to access, research indicates that antidepressants are no more cost-effective than cognitive behavioral therapy (29). Given that psychotherapy is often viewed as preferable to medication (30–32), it is imperative that CC students be better supported in accessing these services, including through mobile resources. This is especially important for younger students, who, based on the epidemiological onset of mental illness, may be experiencing their first symptoms and would benefit from the cognitive tools and coping skills built through therapy. The past-year treatment gap—the proportion of students reporting one or more mental health problems who did not use therapy or medication—was wider for 18–22-year-old CC students relative to their peers at four-year institutions. Age appears to be a protective factor, and analyses that do not account for age may hide, to some extent, the greater risk of mental health problems and lower use of care by CC students.

We also found significant disparities across CC characteristics. For example, we found Latinx students used medication at roughly half the rate of White students. It is unclear if this is due to cultural preferences or lack of access. This is an important area for future research, especially given that college enrollment among non-Hispanic Whites has declined steadily since 2010, while minority enrollment has remained fairly steady, largely due to increases in Latinx enrollment (33). While Arab Americans were a small group within our study, it is notable that they reported the lowest use of therapy yet had rates of medication use similar to White students. This is consistent with past work demonstrating that Arab Americans often present with somatic complaints and are more comfortable with medical approaches (34).

Limitations:

While generalizability of findings is strengthened by the multi-site nature of HMS and random sampling at the student level, there are several limitations to consider. First, while symptoms were measured with validated screens, these assessments do not represent diagnoses. Second, while the institutional sample is large and diverse, it is not random. Survey weights do not account for probability of school selection and findings may not be generalizable; a fully nationally representative sample of CCs is another priority for future research. Third, while response rates were typical for online surveys (35), they clearly raise the potential of nonresponse bias. Researchers applied weights along known characteristics of the full population, but there may be differences on unobserved characteristics.

Conclusions

In one of the largest known study of its kind, findings revealed a high prevalence of mental health problems at CCs and even lower rates of treatment use when compared to four-year settings. As U.S. higher education is shaped by the coronavirus pandemic, we may see shifts in enrollment that could exacerbate known disparities in mental health, college persistence, and other key social and economic outcomes. Continued research on the unique mental health needs of CC students is imperative to promoting equity across these domains, and funding for mental health services on CC campuses is a high priority. Publicly-available national datasets, such as the Healthy Minds Study, provide important opportunities for researchers to contribute evidence that can be used by campus leaders, state governments, and others positioned to address system-level disparities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Over 50% of community college students nationwide screen positive for symptoms of one or more mental health conditions, with prevalence rates highest among younger students (aged 18–22) relative to students aged 30+.

Among community college students with symptoms, less than 30% used mental health treatment in the past year, with larger disparities in use of therapy relative to psychotropic medication.

Students from traditionally-marginalized backgrounds experience a greater mental health burden and are less likely to access services when in need.

Financial stress is a significant predictor of screening positive for one or more mental health condition, and cost of care is the most salient treatment barrier for community college students in need.

Disclosures and acknowledgements:

Dr. EGL is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K08 MH112878).

Contributor Information

Sarah Ketchen Lipson, Boston University School of Public Health, Department of Health Law Policy and Management, Boston, Massachusetts.

Megan V. Phillips, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Department of Health Management and Policy, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Nathan Winquist, Northwestern University Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies, Chicago, Illinois.

Daniel Eisenberg, University of California Los Angeles Fielding School of Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management, Los Angeles, California.

Emily G. Lattie, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Department of Medical Social Sciences and Department of Preventive Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Eiser A: The crisis on campus. Monitor on Psychology, 2011; 42(8): 18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz V, & Kay J: The crisis in college and university mental health. Psychiatric Times, 2009; 26: 32–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipson SK, Lattie EG, & Eisenberg D: Increased Rates of Mental Health Service Utilization by US College Students: 10-Year Population-Level Trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Serv, 2018a; 70: 60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Student Enrollment: How many students enroll in postsecondary institutions annually? National Center for Education Statistics, 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/app/answer/2/2. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Role of Two-Year Public Institutions in Bachelor’s Attainment (2017). nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/SnapshotReport26.pdf. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, Herndon, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Integrated Postsecondary Education Data, Fall Enrollment Data 2012–13. National Center for Education Statistics, 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro D, Dundar A, Chen J, et al. : Completing College: A National View of Student Attainment Rates. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2012. Herndon, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, & Hunt JB: Mental health and academic success in college. B E J Econom Anal Policy 2009; 9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sontag-Padilla L, Woodbridge MW, Mendelsohn J, et al. : Factors Affecting Mental Health Service Utilization Among California Public College and University Students. Psychiatr Serv 2016; 67: 890–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma J, & Baum S: Trends in community colleges: Enrollment, prices, student debt, and completion. College Board Research Brief 2016; 4: 1–23. https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-community-colleges-research-brief.pdf. New York: College Board. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuire TG & Miranda J: New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: policy implications. Policy Anal Brief H Ser 2008; 27: 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fortney J, Curran G, Hunt J, Cheney A, Lu L, Valenstein M, & Eisenberg D: Prevalence of probable mental disorders and help-seeking behaviors among veteran and non-veteran community college students. General Hospital Psychiatry 2016; 38, 99–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortney J, Curran G, Hunt J, Lu L, Eisenberg D, & Valenstein M: Mental Health Treatment Seeking Among Veteran and Civilian Community College Students. Psychiatric Services 2017; 68(8): 851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenberg D, Goldrick-Rab S, Lipson S, & Broton K 2016. “Too distressed to learn?: a survey study of mental health at 10 U.S. community colleges”. www.wihopelab.com/publications/Wisconsin_HOPE_Lab-Too_Distressed_To_Learn.pdf. Madison, Wisconsin.

- 15.Healthy Minds Study. 2020. https://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/hms/. Ann Arbor, Michigan, Healthy Minds Network. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2020. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/InstitutionByName.aspx?goToReportId=6.

- 17.Lipson S, Raifman J, Abelson S, et al. : Gender Minority Mental Health in the U.S.: Results of a National Survey on College Campuses. Am J Prev Med 2019; 57: 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, & Spitzer RL: The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002; 32: 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, et al. : Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004; 42: 1194–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166 (10):1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan JF, Reid F, & Lacey JH: The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999; 319: 1467–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler R, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. : Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lincoln KD: Financial strain, negative interactions, and mastery: Pathways to mental health among older African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology 2007; 33: 439–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirowsky J, & Ross CE: (2001). Age and the effect of economic hardship on depression. J Health Soc Behav 2001; 42: 132–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahlenberg R, Shireman R, Quick K, & Habash T (2018). Policy strategies for pursuing adequate funding of community colleges. https://tcf.org/content/report/policy-strategies-pursuing-adequate-funding-community-colleges/?agreed=1. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McBride PE: Addressing the Lack of Mental Health Services for At-Risk Students at a Two-Year Community College: A Contemporary Review. Community Coll J Res Pract 2019; 43: 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huijbers M J, Spinhoven, P, van Schaik, D J, et al. : Patients with a preference for medication do equally well in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for recurrent depression as those preferring mindfulness. J Affect Disord 2016; 195: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David D, Szentagotai A, Lupu V, et al. : Rational emotive behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial, posttreatment outcomes, and six-month follow-up. J Clin Psychol 2008; 64: 728–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross EL, Vijan S, Miller EM, et al. The Cost-Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Versus Second-Generation Antidepressants for Initial Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in the United States: A Decision Analytic Model. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171:785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanson K, Webb TL, Sheeran P, et al. : Attitudes and preferences towards self-help treatments for depression in comparison to psychotherapy and antidepressant medication. Behav Cogn Psychother 2016; 44: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. : Patient preference for psychological vs. pharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74: 595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laynard R, Clark D, Knapp M, et al. : (2007). Cost-benefit analysis of psychological therapy. Natl Inst Econ Rev 2007; 202: 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Association of Community Colleges (2019). Community college enrollment crisis? Historical trends in community college enrollment. https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Crisis-in-Enrollment-2019.pdf. Washington, DC.

- 34.Melhem I, & Chemali Z (2014). Mental health of Arab Americans: Cultural considerations for excellence of care. In Parekh R (Ed.), Current clinical psychiatry. The Massachusetts General Hospital textbook on diversity and cultural sensitivity in mental health (p. 3–30). Humana Press. 10.1007/978-1-4614-8918-4_1. New York, NY. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, & Gollust SE: Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Med Care. 2007; 45: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.