Abstract

Intimal hyperplasia, thrombosis formation, and delayed endothelium regeneration are the main causes that restrict the clinical applications of PTFE small-diameter vascular grafts (inner diameter < 6 mm). An ideal strategy to solve such problems is to facilitate in situ endothelialization. Since the natural vascular endothelium adheres onto the basement membrane, which is a specialized form of extracellular matrix (ECM) secreted by endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs), functionalizing PTFE with an ECM coating was proposed. However, besides ECs, the ECM-modified PTFE improved SMC growth as well, thereby increasing the risk of intimal hyperplasia. In the present study, heparin was immobilized on the ECM coating at different densities (4.89 ± 1.02 μg/cm2, 7.24 ± 1.56 μg/cm2, 15.63 ± 2.45 μg/cm2, and 26.59 ± 3.48 μg/cm2), aiming to develop a bio-favorable environment that possessed excellent hemocompatibility and selectively inhibited SMC growth while promoting endothelialization. The results indicated that a low heparin density (4.89 ± 1.02 μg/cm2) was not enough to restrict platelet adhesion, whereas a high heparin density (26.59 ± 3.48 μg/cm2) resulted in decreased EC growth and enhanced SMC proliferation. Therefore, a heparin density at 7.24 ± 1.56 μg/cm2 was the optimal level in terms of antithrombogenicity, endothelialization, and SMC inhibition. Collectively, this study proposed a heparin-immobilized ECM coating to modify PTFE, offering a promising means to functionalize biomaterials for developing small-diameter vascular grafts.

Keywords: polytetrafluoroethylene, polydopamine/polyethylenimine, extracellular matrix, heparin immobilization, biocompatibility, small-diameter vascular grafts

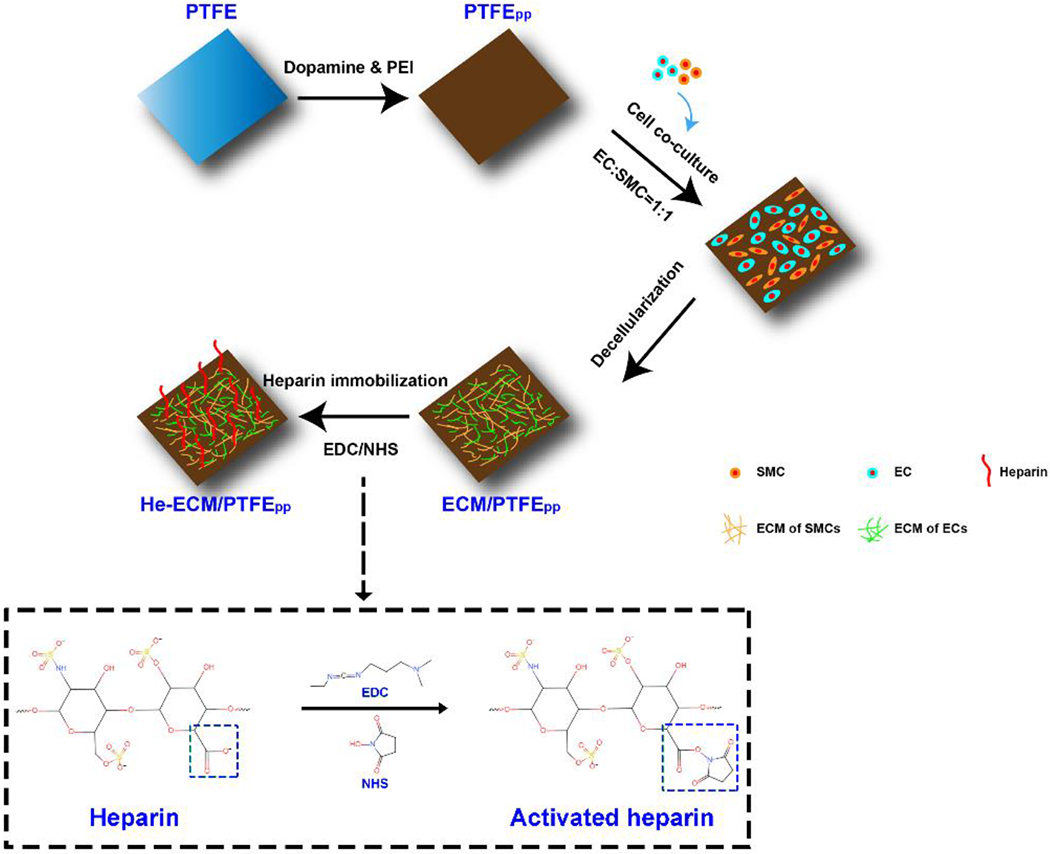

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of human deaths worldwide [1–4]. Vascular transplantation is an effective and common means to treat severe CVD, but the low availability of autologous blood vessels limits its clinical applications, thus stimulating the development of synthetic vascular grafts [1, 5]. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) have been utilized for large-diameter vessel replacements (inner diameter > 6 mm) for several decades due to their excellent biocompatibility and robust mechanical properties, as well as commercial availability [2, 5, 6]. Unfortunately, the outcomes for small-diameter vascular grafts (inner diameter < 6 mm) remain unsatisfactory until now because of the occurrence of occlusion induced by the acute thrombogenicity, intimal hyperplasia, mechanical mismatch with native tissue, and the lack of endothelium regeneration [7–9].

In the vasculature, the interior surface is the endothelium, which is consisted of a monolayer of endothelial cells (ECs), acting as a non-thrombogenic interface and playing a crucial role in the prevention of occlusion [10–13]. More specifically, vascular ECs adhere on the vascular basement membranes (VBMs), which are thin, dense sheets of self-assembled extracellular matrix (ECM) composed of a mixture of constituents, including elastin, laminin, collagen IV, entactin/nidogen, heparan-sulfate proteoglycans, and so on [14–16]. Therefore, developing a biomimetic VBM on the luminal surface of vascular grafts seems an ideal strategy to achieve in situ endothelialization and long-term patency. Researches on biomimetic VBMs have been reported previously, such as the influences of fiber diameters, collagen IV, and laminin on EC behaviors [17–19]. Even so, it is challenging to obtain a fully biomimetic VBM, because of the complicated chemical composition as well as the complex nano- and sub-micron topography features of natural VBMs. Therefore, a complete ECM modification, which could serve a wide variety of biochemical and biophysical functions, seems to be a feasible approach, as it endows the intimal surface of small-diameter vascular grafts with improved biocompatibility. In this regard, various ECM-related materials have been explored. One of the materials was small intestine submucosa, which was an acellular matrix material with good biological properties, specifically related to limited immune reaction and rapid remodeling [20]. Another attractive material was based on the use of decellularized vessels. It had been reported that decellularized xenografts could be employed as potential scaffolds for small-diameter vascular substitutes because of their ability to facilitate the vascular-remodeling process after implantation [21, 22]. Considering the limited sources of human or animal tissues and the complex, time-consuming decellularization process, an ECM coating secreted by vascular cells was proposed as a functionalized means to modify vascular biomaterials. Huang’s group had explored introducing the ECM secreted by ECs onto Ti substrates [23, 24] and polydopamine (PDA) coated 316L stainless steel [25]. The VBM is composed of the ECMs secreted by the ECs and SMCs [10, 26], in consideration of this, Han et al. innovatively introduced a nature-inspired double-deck SMC/EC ECM onto the Ti substrate [27]. The results suggested that these ECM coatings enhanced the material’s hemo-, cyto-, and tissue compatibility significantly.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) has been widely applied as a vascular graft material, but its bioinertness would hamper the EC attachment and endothelialization process, restricting the application for small-diameter vascular graft development [5, 7, 28]. In this study, a nature-inspired ECM coating was introduced onto the PDA/polyethyleneimine (PEI) coated PTFE via co-culture and decellularization of ECs and SMCs, followed by heparin immobilization. Heparin, a negatively charged natural polysaccharide, has been used in fabricating vascular grafts because of its thrombosis impeding property [7, 29, 30]. Moreover, it was reported that heparin could enhance EC proliferation while inhibiting SMC expansion. However, its antiproliferative property might also damage the endothelium [31, 32]. By providing an appropriate dosage of heparin when fabricating vascular grafts, the behaviors of ECs and SMCs could be selectively regulated [31, 32]. Therefore, heparin immobilization with varying concentrations (0.5 mg/mL, 2 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL, and 10 mg/mL) was evaluated in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Medical-grade PTFE sheets with a thickness of 1 mm were purchased from Scientific Commodities Inc. (USA). Branched PEI (average Mn ~ 10000), heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa (CAS Number: 9041081, Grade I-A, ≥ 180 USP units/mg), 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES), 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), Toluidine Blue O (TBO), and dopamine hydrochloride were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Human umbilical artery smooth muscle cell (HUASMC), human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC), and Human Endothelial Cell Medium kit (Catalog#: 1001) were obtained from ScienCell Research Laboratories (USA). Smooth Muscle Cell Growth Medium-2 BulletKit (Catalog#: CC-3182) was purchased from Lonza (USA). Porcine whole blood with Na citrate (Catalog#: 50414268) was bought from Fisher Scientific (USA). The 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Catalog#: 40043), rhodamine phalloidin (Catalog#: 00027), and live/dead viability kit (Catalog#: 30002) were purchased from Biotium (USA). Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Catalog#: HY-K0301) was obtained from MedChemExpress (USA). Nitrite assay kit (Catalog#: K544) was bought from BioVision (USA), and prostacyclin ELISA kit (Catalog#: EKU08421) was obtained from Biomatik (USA). The water used in this study was purified by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, USA). All the chemicals were of analytical grade and were used without further treatment if not specially mentioned.

2.2. Surface modification of PTFE

Detailed procedures are presented in Figure 1. Briefly, dopamine and branched PEI were dissolved in the Tris buffer (pH 8.5) with concentrations of 2 and 0.5 mg/mL, respectively. The PEI concentration was controlled at a low level (0.5 mg/mL) because an appropriate dosage of PEI was beneficial for cell adhesion, while an overdose might cause cell death [7, 33]. Upon dissolution, the dopamine immediately started undergoing self-polymerization into polydopamine (PDA), reacting with PEI to form PDA/PEI conjugates [34, 35]. After ultrasonication cleaning in 20% (v/v) ethanol solution for 30 min, the PTFE sheets were immersed in a freshly prepared PDA/PEI coating solution for 24 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the obtained samples were removed from the solution and washed three times with deionized water and named PTFEpp. Afterward, HUVECs and HUASMCs (mixed in a 1:1 ratio) were seeded on the PTFEPP (sterilized with 75% (v/v) ethanol) with a seeding density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2, and co-cultured in the medium that contained a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of the Human Endothelial Cell Medium and Smooth Muscle Cell Growth Medium-2 for 3 days under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2 under a moist environment), followed by a typical decellularization operation as reported previously [24, 27] to obtain the ECM-coated samples (ECM/PTFEPP). Thereafter, heparin (0.5 mg/mL, 2 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL, and 10 mg/mL in MES buffer, pH 6.5) was activated in the presence of 120 mM EDC and 60 mM NHS for 4 h at 25 °C. The ECM/PTFEPP samples were then incubated in the activated heparin sodium solutions at 25 °C overnight, obtaining the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP samples. All biological procedures were performed in a sterile environment.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration to show the stepwise surface modification procedures of PTFE.

2.3. General characterization

The surface topographies of the samples were characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Jeol, NeoScope JCM-5000) and an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker BioScope Catalyst, Multimode 8) in the tapping mold. A contact angle instrument (Dataphysics, OCA15EC) was utilized to evaluate the wettability of various samples, and a volume of 5 μl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) rather than water was dropped on the sample surfaces for the wettability test. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Bruker, Tensor 27) was used to identify the functional groups on the sample surfaces. The scanning range was set from 400 to 4000 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The surface chemical compositions were measured using the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific, K-Alpha), and an XPS peak-fitting software (XPS PEAK41) was applied to analyze the spectra.

2.4. Heparin density characterization–TBO assay

The immobilized amounts of heparin were characterized by the TBO assay as described in previous studies [31, 36]. In specific, the TBO solution (0.04 wt%) was prepared by dissolving the TBO powder in aqueous 0.01 M HC1/0.2 wt% NaCl, and then reacted with heparin of known concentrations to form the heparin-TBO blue complex. Afterward, the mixture was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min, and the complex was carefully rinsed with PBS and then dissolved in a 5 ml ethanol/0.1 M NaOH mixture (4:1, v/v) solution. Finally, the absorbance of the resultant solution was measured at 530 nm using a microplate reader (MULTISKAN FC, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the standard curve was thus established. To determine the amounts of immobilized heparin, different samples were incubated in 5 ml TBO solution under static conditions at 37 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, the formed heparin–TBO complex was eluted and dissolved in 5 ml ethanol/0.1 M NaOH mixture (4:1, v/v) solution. After completing decolorization of the samples, the absorbance of the supernatants was measured at 530 nm, and the heparin amounts on sample surfaces were evaluated using the obtained calibration standard curve.

2.5. Hemocompatibility evaluation

2.5.1. Platelet adhesion test

Briefly, platelet rich plasma (PRP) was obtained by centrifuging porcine whole blood (with Na citrate) at 1500 rpm for 15 min, then a quantity of 500 μL/cm2 PRP was added to the samples, which had been sterilized and rinsed with the PBS solution before testing, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h. After incubation, the samples were rinsed with PBS to wash away the unattached platelets and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. Next, samples were dehydrated with a series of ethanol solution (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%, v/v) and sufficiently dried in a desiccator, then imaged using SEM.

2.5.2. Whole blood clotting test

All samples were punched into round pieces and placed in 24-well plates. 100 μl anticoagulated whole blood was dispensed onto the surfaces of pre-warmed samples, followed by adding 20 μL of 0.2 M CaCl2 solution into the blood to start the blood coagulation cascade. After incubation for 60 min at 37 °C, 2.5 mL of distilled water was carefully added into each well, and then incubated for another 5 min at 37 °C. 100 μL of anticoagulated whole blood mingling with 2.5 mL distilled water was regarded as the control group. The absorbance of the resultant hemoglobin solution was measured at 540 nm (OD540) with a microplate reader (MULTISKAN FC, Thermo Scientific). Finally, the blood-clotting index (BCI) was calculated using the following formula (1) [18].

| (1) |

where Ds is the OD540 value of the test sample, and D0 is the OD540 value of the control group.

2.5.3. Hemolysis test

The hemolysis test was conducted according to the previous literature [37, 38]. Briefly, samples (10 mg) were incubated in 10 mL PBS for 72 h at 37 °C. Then 0.2 mL diluted blood, which was prepared by diluting porcine whole blood (with Na citrate) with PBS solution at a volume ratio of 4:5, was added to each sample and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance of supernatant was measured at 545 nm with an ultraviolet spectrophotometer, and the hemolysis ratio (HR) was defined as the following formula (2). PBS solution and deionized water were applied as the negative and positive controls, respectively.

| (2) |

where ODSA represents the absorbance of experimental samples, ODPO represents the absorbance of positive control, and ODNE stands for the absorbance of negative control.

2.6. Cell culture and in vitro cytocompatibility evaluation

All samples were punched and placed in 24-well plates, followed by sterilization using 75% (v/v) ethanol. Two types of cells, namely, HUVECs and HUASMCs, were separately seeded onto various samples with the same concentration of 6 × 104 cells per well for cell adhesion analysis, and 1 × 104 cells per well for all other characterizations. The Human Endothelial Cell Medium and Smooth Muscle Cell Growth Medium-2 were used for HUVEC and HUASMC cultures respectively. The culture medium was replaced every two days, and at least three replicates were performed on all tests for statistical analysis.

The cell adhesion test was conducted at 6 h after cell seeding. Fixed cells (in the 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C for 24 h) were stained with rhodamine and DAPI successively after sufficient PBS rinse to wash away the non-adhered cells. After imaging with a fluorescence microscope (DMI3000, Leica), the adhered cells on various samples were counted to obtain the cell adhesion densities. For the cell proliferation test, a CCK-8 assay kit was applied to evaluate cell proliferation at 1 d, 3 d, and 5 d. Cell viability was measured by the live/dead viability kit after 5 d of culture according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the cell shape and cytoskeleton characterization, the cells cultured on different samples were stained and imaged at 3 d, and the relevant structure parameters were measured using the Image J software. A centrifugation cell adhesion assay was utilized for in situ relative cell adhesion force measurement, and the detailed procedures were performed as reported in previous studies [17, 39, 40]. For evaluating the nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGI2) production properties of HUVECs, related ELISA kits were utilized according to the manufactures’ recommended protocols after 3 d of culture, and the cell culture medium was not replaced until testing. By doing so, the cumulative release amounts of NO and PGI2 after 3 days of culture could be estimated.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Tukey’s test was then applied to evaluate the specific differences between the data, and the significant differences were presented as *, **, and ***, which meant p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface characterization

3.1.1. Surface chemistry

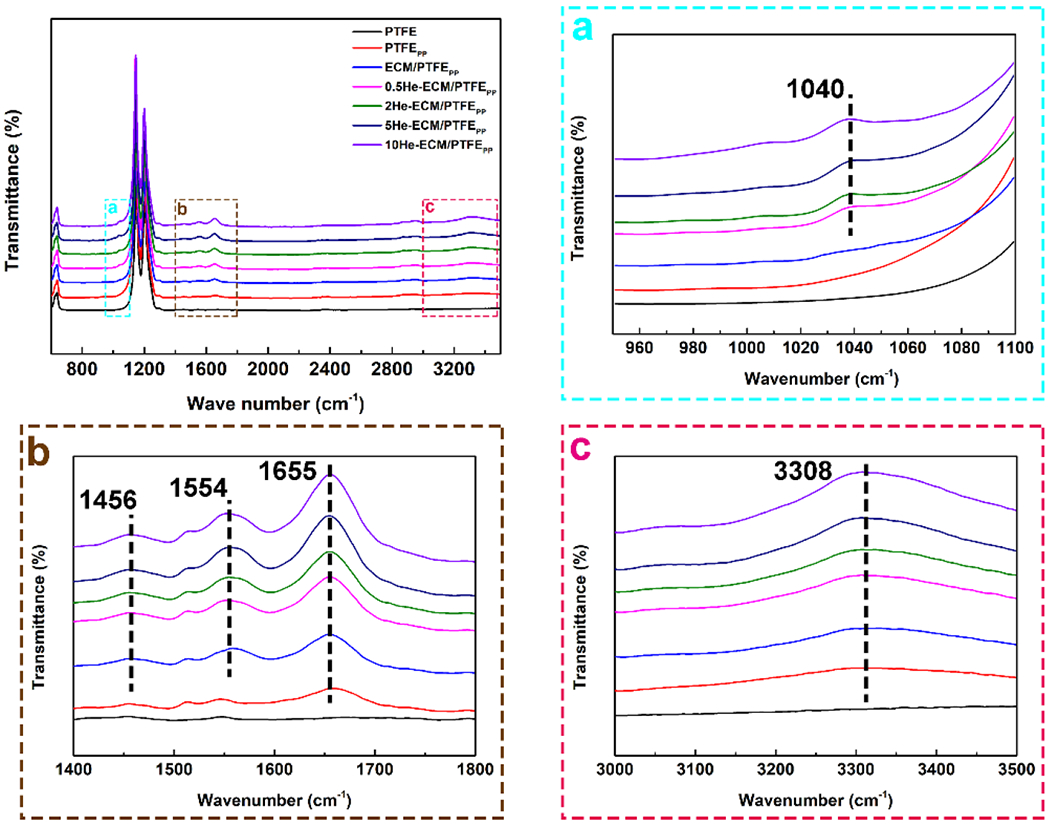

The surface chemistry properties of various samples were first characterized using FTIR. In Figure 2, all samples showed peaks at 1202 cm−1 and 1148 cm−1, and the two characteristic peaks were attributed to the asymmetrical and symmetrical C-F stretching of PTFE. For the PTFEPP, a new peak could be found at 1655 cm−1, which was ascribed to the carbonyl groups derived from PDA [41]. The broad band near 3308 cm−1 resulted from the stretching vibrations of the O-H and N-H groups from PDA and PEI. The new peaks indicated the successful co-deposition of PDA/PEI on the PTFE. After the introduction of ECM coating, the intensities of both of the peaks at 1655 cm−1 and 3308cm−1 increased. The former was attributed to the carbonyl groups in amide I, and the latter was due to the introductions of the O-H and N-H groups from ECM proteins.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of different samples. The square dashed regions were enlarged for clarity.

Moreover, two new peaks appearing at 1456 cm−1 and 1554 cm−1 were observed, which were assigned to the bending vibrations of N-H of amide III, and C-N and N-H of amide II, respectively [42–44]. ECM is a complex system composed of proteins and polysaccharides (laminin, collagen, elastin, dextran, and so on) [10]. Therefore, the vibration peaks of amide I, amide II, and amide III suggested the successful incorporation of ECM coating. When heparin was further grafted onto the ECM/PTFEPP, a new shoulder peak representing S=O vibration at 1040 cm−1 appeared. Additionally, the immobilization of heparin introduced plenty of C=O, O-H, C-N, and N-H groups onto the ECM/PTFEPP, thus leading to the obviously enhanced absorption at 1456 cm−1, 1554 cm−1, 1655 cm−1, and the broad band near 3308 cm−1. Meanwhile, the intensities of these peaks gradually increased with the increase of heparin density.

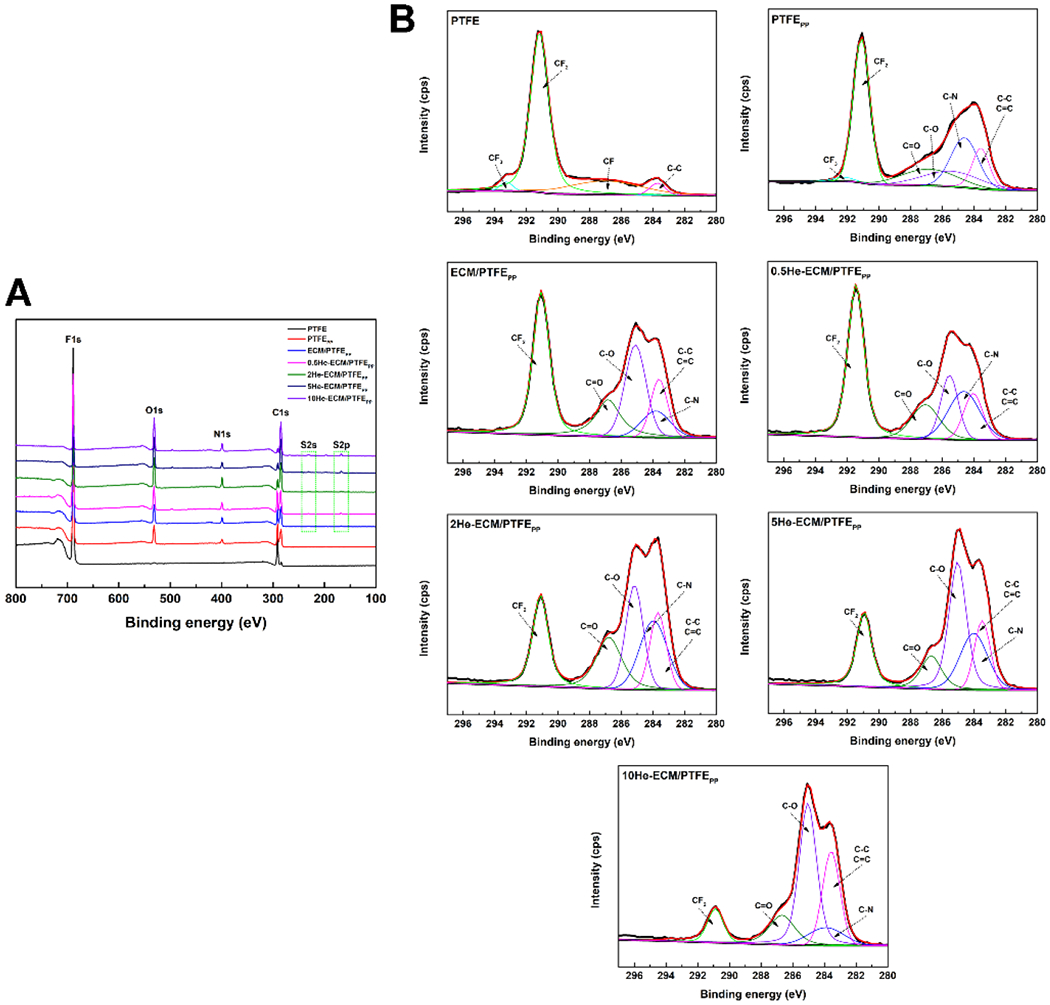

XPS was utilized to further analyze the surface chemical composition of various samples. The XPS spectra and elemental compositions were shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, respectively. In Figure 3A, only C1s and F1s were detected on the PTFE, while all other samples presented additional characteristic peaks of O1s and N1s. Furthermore, for the ECM-PTFEPP and heparin-immobilized samples, new peaks corresponding to S2s and S2p could be found, indicating that the sulfur contents from the ECM coating (such as chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate, heparin, heparin sulfate, and keratin sulfate) and heparin were successfully introduced. The C1s core level scans exhibiting the detailed information of carbon-containing bonds were shown in Figure 3B. As expected, when compared to the PTFE, each surface modification step obviously enhanced the C–C/C=C band, and introduced the new bands of C=O, C–O, and C–N. These new carbon peaks came from the PDA and PEI (the PTFEPP), as well as ECM proteins (the ECM/ PTFEPP) and heparin (heparin-immobilized samples). From the statistical results in Table 1, it could be found that N content increased from 0 for the PTFE to 5.77% for the PTFEPP, and 9.90% for the ECM/PTFEPP, which suggested the successful co-deposition of PDA/PEI and the subsequent ECM coating preparation. In addition, S was detected at a rate of 0.97%, 1.15%, 2.14%, and 3.01% on the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP, respectively, higher than that of the ECM-PTFEPP (0.62%), exhibiting an uptrend. Moreover, in contrast with the ECM/PTFEPP, the O contents of heparin-immobilized samples increased obviously, due to the fact that heparin possessed high O and S contents.

Figure 3.

XPS analysis of different samples. (A) XPS survey spectra; (B) Gauss-fitted high-resolution spectra of the carbon peak (C1s).

Table 1.

Elemental composition of samples obtained via XPS

| Samples | C (%) | F (%) | N (%) | O (%) | S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTFE | 31.96 | 68.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PTFEPP | 31.22 | 48.03 | 5.77 | 14.98 | 0 |

| ECM/PTFEPP | 46.97 | 26.57 | 9.90 | 15.94 | 0.62 |

| 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP | 36.96 | 25.79 | 10.19 | 26.09 | 0.97 |

| 2He-ECM/PTFEPP | 37.76 | 22.86 | 10.99 | 27.24 | 1.15 |

| 5He-ECM/PTFEPP | 41.24 | 16.01 | 11.61 | 29.00 | 2.14 |

| 10He-ECM/PTFEPP | 42.93 | 11.89 | 16.39 | 25.78 | 3.01 |

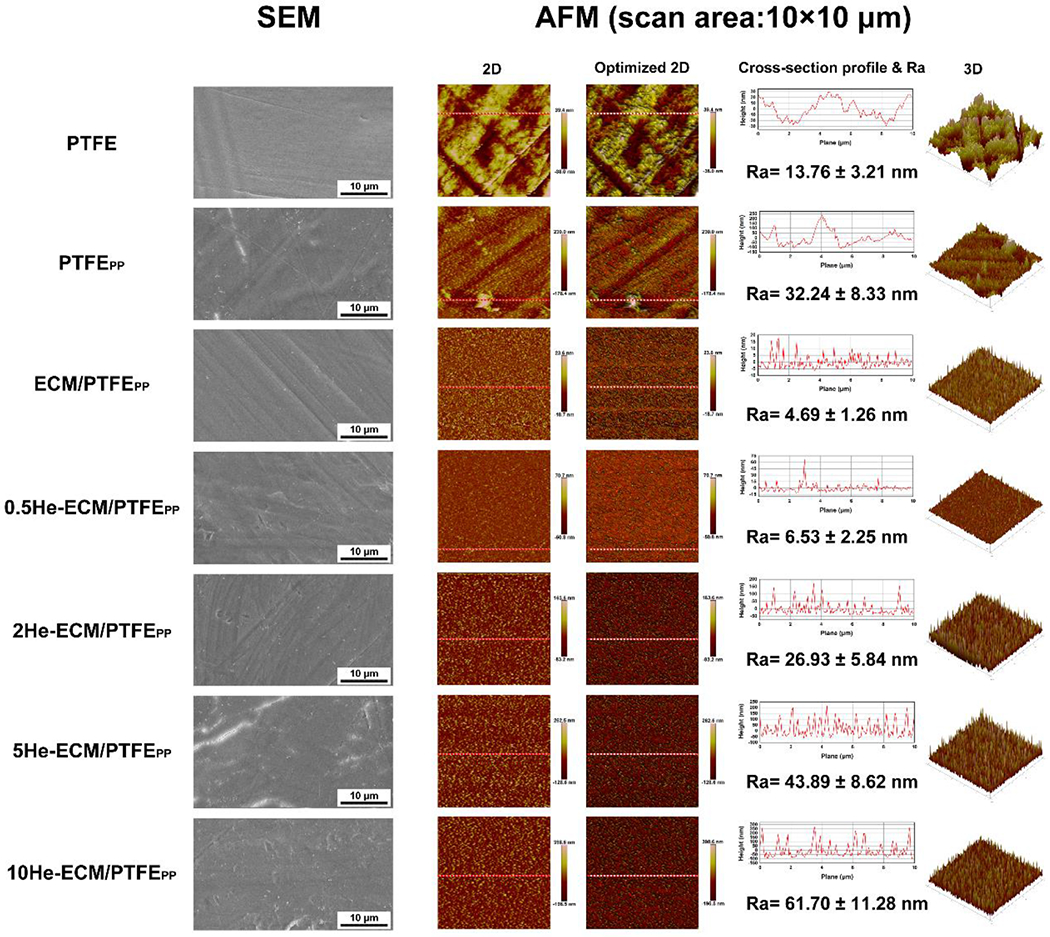

3.1.2. Surface morphology

As can be seen from Figure 4, the PTFE showed a relatively smooth surface (SEM images), while nano- and micropores could be found on its surface from the high-resolution AFM characterization results. After the co-deposition of PDA/PEI, the PTFEPP showed a rougher surface with many apparent aggregates, and the distribution of these aggregates was inhomogeneous (SEM images), in agreement with the observation of Luo et al. [45]. Its Ra value increased to 32.24 ± 8.33 nm, 2.34 times of that of the PTFE (13.76 ± 3.21 nm). It had been reported that self-polymerized PDA formed nanoparticles in an aqueous solution, and the addition of PEI could suppress the precipitation of PDA aggregates [7, 34, 35]. However, some relatively large PDA/PEI aggregates with different sizes (AFM images) were still observable in the present study. From the SEM image of the ECM/PTFEPP, markedly less aggregates were found when compared with the PTFEPP because most of the aggregates were washed away during the ECM preparation process. The Ra value of the ECM/PTFEPP was 4.69 ± 1.26 nm, much smaller than that of the PTFEPP. It could be summarized that the ECM covered the surface of the PTFEPP, thus creating a smoother surface. Similar speculation had been reported before [24, 27]. After further heparin immobilization, more aggregates anchored onto the substrate surfaces (SEM images) when compared to the ECM/PTFEPP. It was because heparin molecules tended to aggregate when dried from the aqueous solution [46]. Furthermore, noticeably less aggregates could be seen on the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP due to its lower heparin density. From the AFM 2D and 3D images of heparin-immobilized samples, a higher heparin density led to a rougher surface, and the height differences from the cross-section profile lines confirmed this trend. Moreover, Ra values of the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP were 6.53 ± 2.25 nm, 26.93 ± 5.84 nm, 43.89 ± 8.62 nm, and 61.70 ± 11.28 nm, respectively, increasing with the increase of heparin density.

Figure 4.

Surface topography characterization by SEM and AFM (including 2D and optimized 2D images, cross-section profile lines corresponding to the red lines shown in 2D and optimized 2D images, Ra values, and 3D images).

3.1.3. Assessment of heparin immobilization and surface wettability

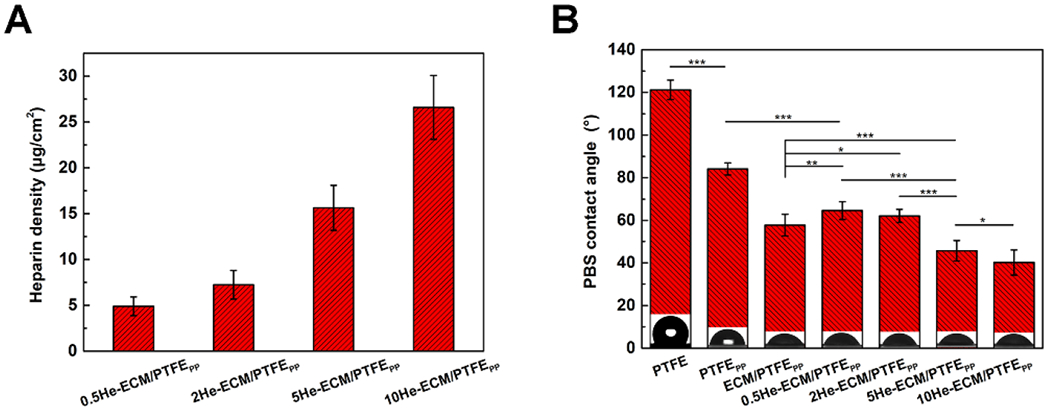

The heparin amounts were calculated via the TBO assay as reported in previous studies [31, 36]. Heparin could be covalently grafted to the bioactive groups provided by PEI, PDA, and ECM proteins on the ECM/PTFEPP, including -NH2 and -COO-. As illustrated in Figure 5A, the heparin densities on the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP were 4.89 ± 1.02 μg/cm2, 7.24 ± 1.56 μg/cm2, 15.63 ± 2.45 μg/cm2, and 26.59 ± 3.48 μg/cm2, respectively. With the increase of heparin concentration, the heparin amounts immobilized onto the samples gradually increased, consistent with the FTIR and XPS results.

Figure 5.

Heparin densities (A) and PBS contact angles (B) of different samples.

The PBS contact angle was measured to characterize the surface hydrophilicity of various samples. In Figure 5B, the virgin PTFE exhibited strong hydrophobicity, having a PBS contact angle of 121.24 ± 4.68°. After the co-deposition of PDA/PEI, the PBS contact angle dramatically decreased to 84.13 ± 2.84° because of the introduction of plenty of hydrophilic groups [7, 25, 41]. For the ECM/PTFEPP, more hydrophilic biomolecules from the ECM proteins were immobilized onto the PTFEPP, so it presented a further decreased PBS contact angle of 57.86 ± 5.18°, similar with the results from previous studies [25, 27]. Obviously, compared to the ECM/PTFEPP, the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP and 2He-ECM/PTFEPP showed significantly higher PBS contact angles of 64.61 ± 4.22° and 62.19 ± 3.27°, respectively. Even though heparin was rich in hydrophilic groups (including hydroxyl, amine, carboxyl, and sulfo groups), the EDC/NHS coupling chemistry might have changed the original molecular conformation and orientation of ECM proteins, thus affecting the hydrophilicity of the ECM coating. However, with the further increase of heparin concentration, many more hydrophilic groups from heparin were introduced, thus PBS contact angles of the 5He-ECM/PTFEPP and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP significantly decreased to 45.72 ± 4.89° and 40.25 ± 5.96°, respectively.

3.2. Hemocompatibility evaluation

Satisfying hemocompatibility is considered to be of the most important factors that determines the long-range patency of implanted vascular grafts [1, 2, 5]. In the present study, the platelet adhesion, whole blood clotting test, and hemolysis test were conducted to evaluate the hemocompatibility.

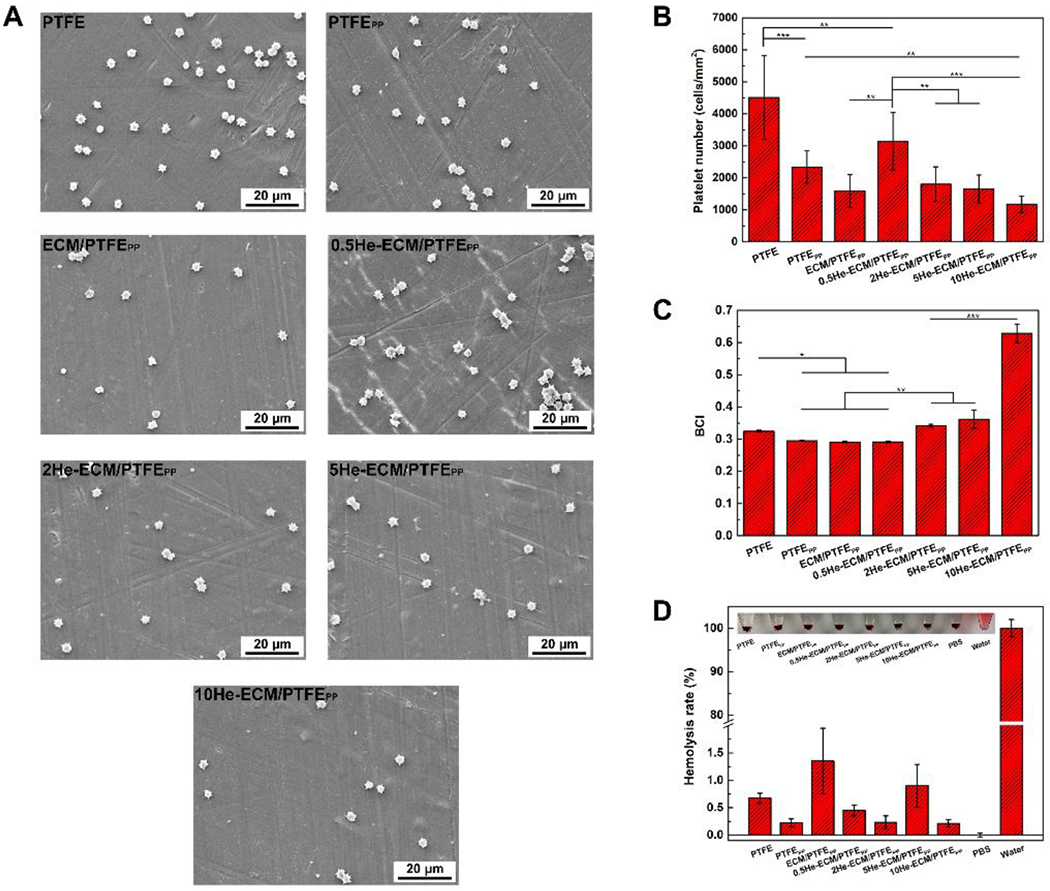

As shown in Figure 6A, massive platelets attached onto the PTFE, obviously more than all other samples, and relatively more platelets distributed on the PTFEPP and 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP as well. The amounts of adhered platelets on the ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP were less, with no stark differences found among them. Quantitative characterization of the adherent platelets on each surface was consistent with the SEM images that the numbers of adhered platelets (platelets/mm2) on the PTFE, PTFEPP, ECM/PTFEPP, 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP were 4511, 2340, 1591, 3150, 1805, 1652, and 1178, respectively (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

SEM images (A) and statistical results (B) of the platelet adhesion test. BCI values (C) and hemolysis rates (D) of different samples.

Compared to the PTFE, the co-deposition of PDA/PEI significantly increased the hydrophilicity of the PTFEPP, leading to less platelets adhered. This was in agreement with the previous finding that the increase of hydrophilicity corresponded to the decrease of platelet adhesion [7, 47]. In the presence of foreign biomaterials, albumin, fibrinogen, and other plasma proteins would be absorbed quickly, followed by attachment of platelets. The denaturation of fibrinogen is generally considered as a significant cause of platelet activation and aggregation [48–50]. Previous studies suggested that the ECMs secreted by ECs or SMCs possessed excellent ability of reducing fibrinogen adhesion and inhibiting its denaturation. Moreover, most of the platelets adhered on the ECM surfaces through accidental physical adsorption and not fibrinogen denaturation pathway [24, 25, 27]. Therefore, for the ECM/PTFEPP, the number of adhered platelets on it would decrease. Heparin, as an anticoagulant with frequent clinical use, could prevent the protein fouling on the surfaces and inactivate proteins involved in thrombus development, thus impeding blood coagulation [32, 47, 48]. Strangely, compared to the ECM/PTFEPP, the amount of adhered platelet on the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP was significantly higher (p < 0.01). The reason was speculated that the heparin immobilization process might have damaged the integrity and biological activities of the ECM. As a result, the negative effects of heparin immobilization offset the benefit of heparin at a low density (0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP), thus resulting in a poor antithrombotic property. With the increase of heparin density, the numbers of adhered platelets on the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP decreased gradually, comparable with that of the ECM/PTFEPP, while no significant differences existed among them.

A higher BCI value indicated better anticoagulation capability. BCI values of various samples were shown in Figure 6C. Compared to the PTFE, the BCI value of the PTFEPP significantly decreased. The reason might be that the PTFEPP attracted much more plasma proteins adsorption (like fibrinogen) because of the presence of PDA, resulting in the blood cells attachment. After the introduction of ECM coating, the improved hydrophilicity of the ECM/PTFEPP restricted the adsorption of plasma proteins [51, 52], such as fibrinogen [27]. However, the denaturation of absorbed proteins would be inhibited due to the favorable biocompatibility of the ECM coating. The positive effects of the ECM coating counteracted its negative effects on blood cell attachment, thus no obvious difference was found between the ECM/PTFEPP and PTFEPP. For heparin-immobilized samples, the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP exhibited a close BCI value to the ECM/PTFEPP because of its relatively low heparin density. With increasing heparin density, the BCI values of the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP presented a general uptrend, indicating their improved anticoagulation properties. The difference between the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP and 5He-ECM/PTFEPP was statistically insignificant, yet the 10He-ECM/PTFEPP possessed the highest BCI value, significantly higher than all other samples. The reason might be that heparin could prevent the intrinsic blood coagulation by inactivating proteins involved in thrombus development [32, 53].

As shown in Figure 6D, all hemolysis rates were less than 2%, and no obvious hemolysis phenomenon could be observed from the inset images, suggesting that these samples could be regarded safe for direct contact with blood [38, 54]. Moreover, no significant differences could be found between the ECM/PTFEPP and the heparin-immobilized samples, though heparin played a significant role in the management of complement mediated hemolysis [32].

3.3. HUVEC performances

3.3.1. HUVEC adhesion, proliferation, and viability

For a vascular graft, behaviors and functions of ECs that adhere on the luminal surface decide its endothelialization process, antithrombosis, and anti-hyperplasia properties to a great extent [55, 56]. Thus, the HUVEC growth and functions were evaluated to investigate the endothelialization effectiveness of various samples.

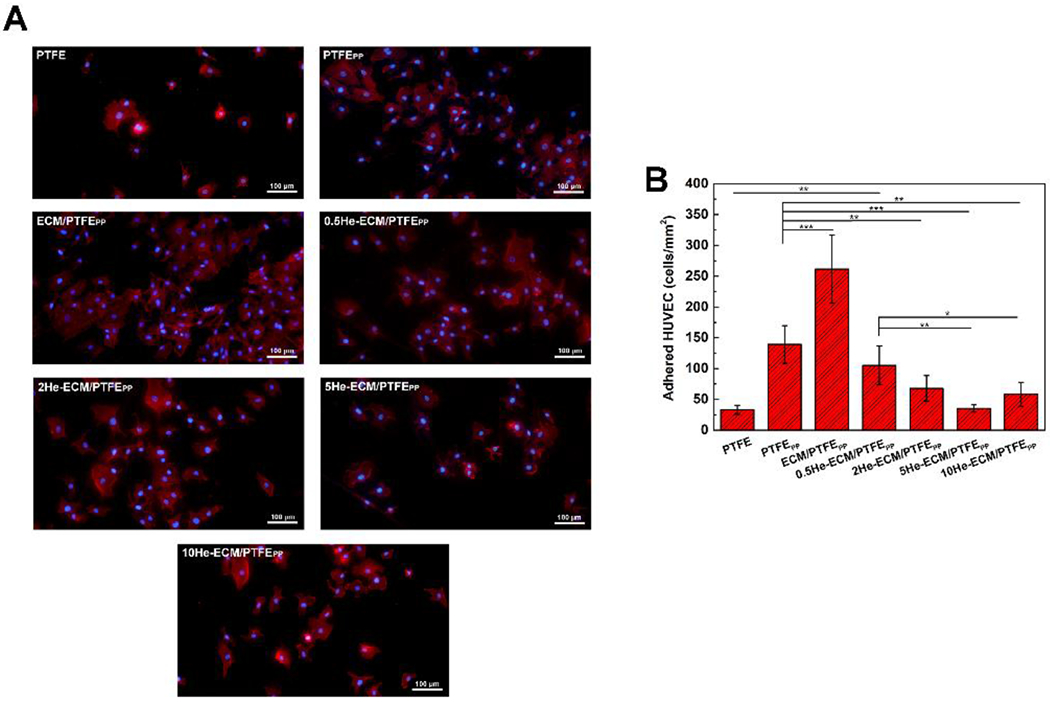

Figure 7A exhibited the fluorescence images of HUVECs adhered on various samples after a 6 h culture. It could be found that HUVECs on the PTFE did not spread actively. Their round and dwindled shapes suggested that the PTFE surface lacked biological conditions and was not suitable for cell adhesion and spreading. After surface modification, the strong expression of F-actin stress fibers suggested the improved HUVEC spreading, demonstrating the relatively high activation level of HUVECs on these samples. In Figure 7B, the HUVEC number on the PTFE was 33 cells/mm2, significantly lower than that on the PTFEPP of 139 cells/mm2. It was reported that PTFE vascular grafts could not be endothelialized normally, resulting in a poor patency and a high risk of thrombosis [2]. For the PTFEPP, native serum proteins that could interact with the adhesion receptors on the cell membrane were more likely to adsorb onto it and maintain their native structures and activities [57], thus leading to its improved cell adhesion. In addition, PEI has been reported to effectively enhance cell attachment and adhesion [33, 58].

Figure 7.

Fluorescence images (A) and numbers (B) of adhered HUVECs on different samples at 6 h.

A significant improvement in cell adhesion was achieved after the introduction of ECM coating. Compared to the PTFEPP, the HUVEC density on the ECM/PTFEPP significantly increased by 1.88 times to 262 cells/mm2. Surface modification of vascular biomaterials with ECM components, such as some ECM proteins (like fibronectin, laminin, and collagen IV) or functional peptides (like GFPGER, YIGSR, and cyclic RGD), could improve the biological functions remarkably [17, 59, 60]. Therefore, the complete ECM would endow the vascular biomaterials with more physiological and biological functions. Relevant studies had showed that the nature-inspired ECM coating could significantly improve the material’s hemocompatibility, cytocompatibility, and tissue compatibility [24, 25, 27]. In the present study, the ECM coating provided plenty of binding sites, which could bind to the integrin proteins on the HUVEC membranes, thus enhancing HUVEC adhesion. However, compared with the ECM/PTFEPP, the numbers of adhered HUVECs significantly decreased after heparin immobilization. HUVEC densities on the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 5He-ECM/PTFEPP samples were 105 cells/mm2, 68 cells/mm2, and 35 cells/mm2, respectively, decreasing gradually with the increase of heparin density. For the 10He-ECM/PTFEPP, the HUVEC number slightly increased to 58 cells/mm2, significantly lower than that of the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, while no significant differences could be found among the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP. It was speculated that the decrease of the HUVEC adhesion was due to the decline of the functional groups of ECM proteins because a number of the bioactive groups had been reacted and occupied by heparin. Furthermore, the EDC/NHS would also cross-link ECM proteins with other ECM proteins, affecting the original biological activities of the ECM coating.

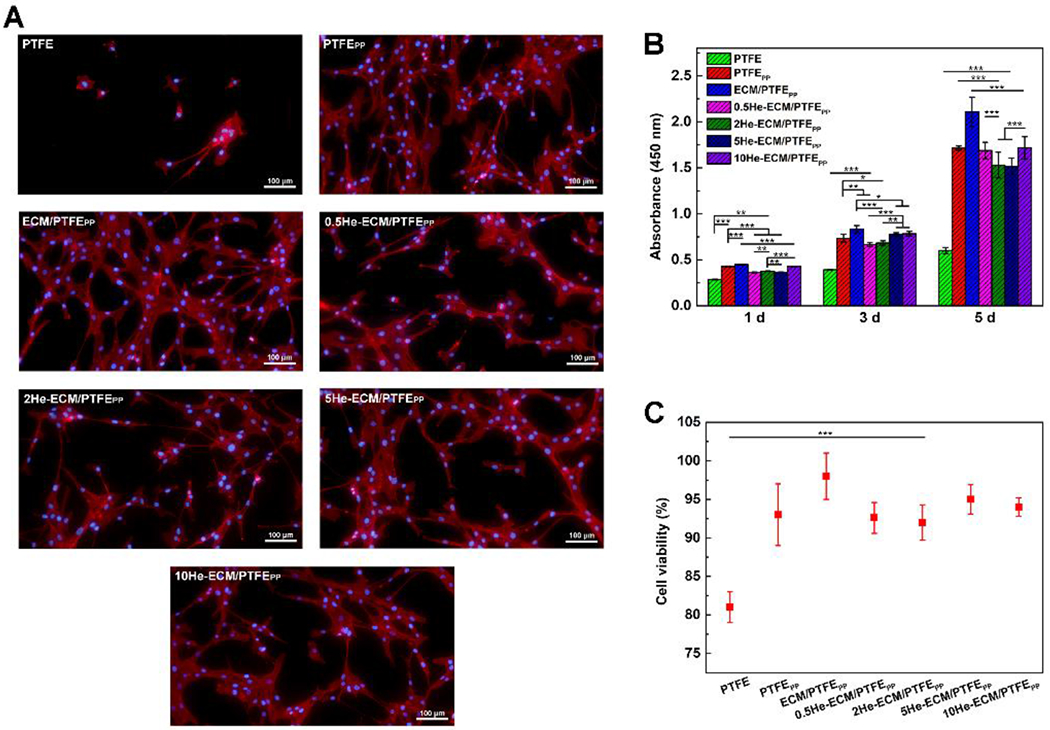

Figure 8A showed the statistical results of HUVEC proliferation from the CCK-8 assay. As it can be seen, the PTFE showed the lowest values through the culture period, significantly lower than all other samples, indicating that HUVECs proliferated slowly or were not able to proliferate on PTFE materials. After the PTFE was coated with PDA/PEI, besides HUVEC proliferation, the HUVEC viability significantly increased as well, from 85.15 ± 5.06% to 92.26 ± 2.01% (Figure 8B). For the ECM-PTFEPP, collagen IV, laminin, and other ECM proteins were introduced. They provided signaling biomacromolecules similar to the in vivo environment for the cells and abundant binding sites for cell proliferation, thus the HUVEC proliferation improved further. Compared to the PTFEPP, the ECM/PTFEPP showed a similar cell population at day 1, while the values increased to 2.02 times and 2.68 times as many on days 3 and 5, respectively. And its viability increased to 97.82 ± 1.85%, which was the highest value among all the samples (Figure 8B). When heparin was immobilized, these samples showed similar absorbance values to the ECM/PTFEPP at day 1, with no significant differences. Extending the culture period, the statistical results indicated that HUVEC proliferation was negatively correlated with the heparin density. At day 3, the ECM-PTFEPP, 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 2He-ECM/PTFEPP exhibited the similar HUVEC proliferation, significantly better than the 5He-ECM/PTFEPP and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP. At day 5, the ECM/PTFEPP and 2He-ECM/PTFEPP maintained excellent HUVEC proliferation. Their absorbance values were significantly higher than those of the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP. The reason was speculated that as more heparin was introduced, more functional groups of the ECM coating would be consumed. However, as a bioactive molecule with good biocompatibility, heparin could help to increase the EC proliferation by binding and stabilizing angiogenic growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) [32, 36, 61]. Therefore, introducing an appropriate dosage of heparin could yield the best overall benefit. This was especially true for the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, which always exhibited similar HUVEC adhesion and proliferation results with the ECM/PTFEPP in this study. In Figure 8B, after heparin immobilization, the HUVEC viability values of the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP were 94.45 ± 1.24%, 95.19 ± 0.88%, 93.64 ± 1.33%, and 92.96 ± 1.14%, respectively, without significant differences among them, indicating the limited effects of heparin on HUVEC viability.

Figure 8.

(A) Statistical results of HUVEC proliferation from the CCK-8 assay. (B) Statistical results of HUVEC viability from the live/dead assay at day 5.

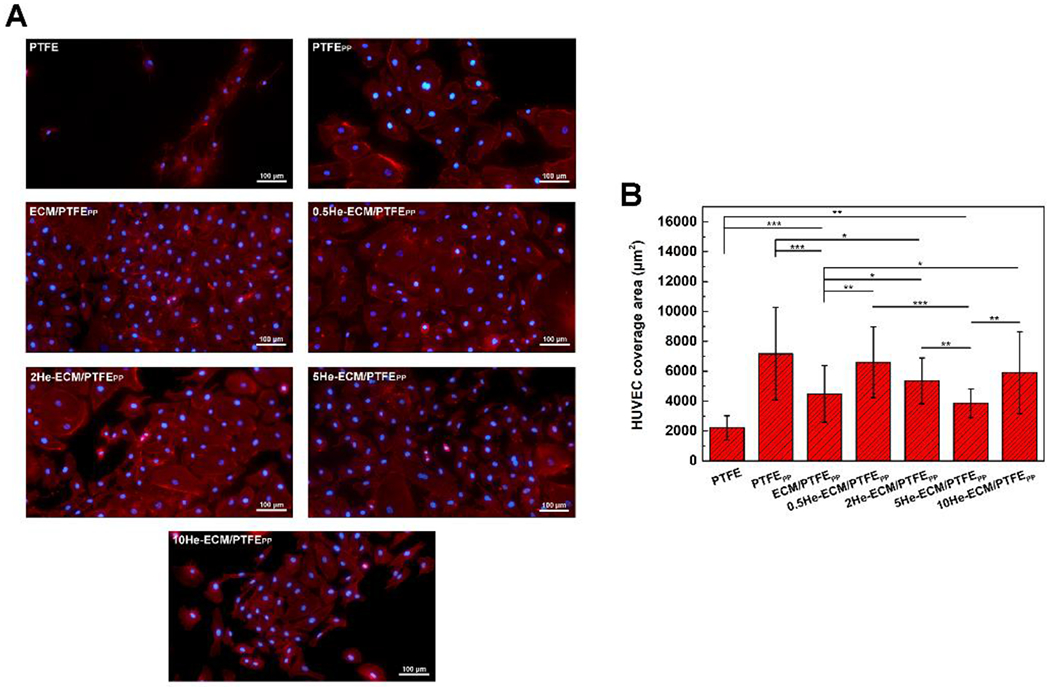

3.3.2. HUVEC morphology

As can be seen in Figure 9A, HUVECs on the PTFE exhibited a typical non-adherent state with restricted-spread shapes. However, following a series of surface modifications, the cellular-substrate interaction was greatly improved, mainly owing to the introduction of biological functional groups from PDA, PEI, ECM components, and heparin. Thus, HUVECs on these modified samples presented ellipse, polygon, or circular morphologies and possessed significantly larger average coverage areas than the PTFE of 2211.27 μm2. HUVECs on the PTFEPP showed the largest size of 7172.46 μm2, while the spread of HUVECs was restricted after the introduction of ECM coating and heparin, especially for the ECM/PTFEPP of 4483.16 μm2 (p < 0.001), 2He-ECM/PTFEPP of 5356.43 μm2 (p < 0.05), and 5He-ECM/PTFEPP of 3852.91 μm2 (p < 0.001) (Figure 9B). This was likely attributed to the significant increase of the cell population over the limited sample area, though both the ECM coating and heparin were beneficial for improving HUVEC spreading [10, 32, 62, 63]. Moreover, the HUVEC spreading area of the 5He-ECM/PTFEPP was significantly smaller than those of other heparin-immobilized samples (0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP of 6599.72 μm2 and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP of 5902.36 μm2). The reason might be that as more heparin was immobilized, the integrity of the ECM coating was negatively affected, subsequently leading to weakened HUVEC affinity and restricted HUVEC spreading. For the 10He-ECM/PTFEPP, relatively low HUVEC proliferation on it contributed to more space for HUVEC spreading, thus the HUVEC coverage area value increased.

Figure 9.

Fluorescence images (A) and the coverage areas (B) of HUVECs cultured on different samples after 3 days incubation.

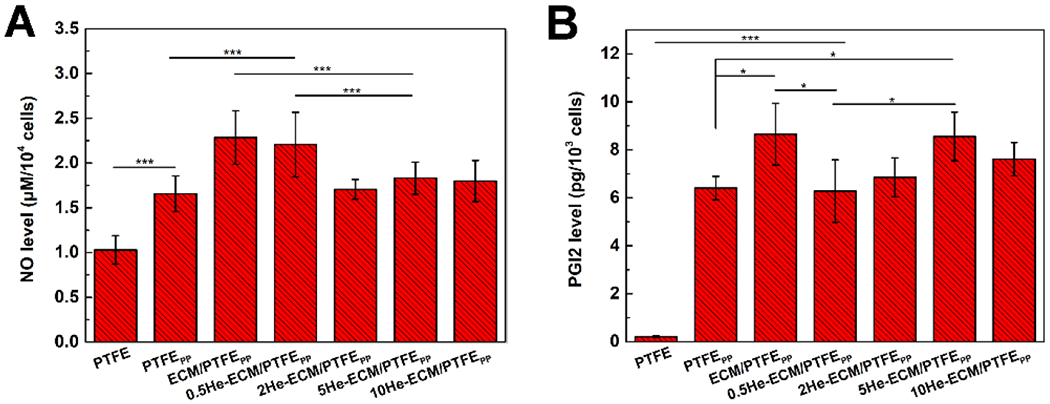

3.3.3. NO and PGI2 release

NO is an important endothelial-derived regulatory molecule. It possesses extensive metabolic, vascular, and cellular effects on maintaining vascular homeostasis, such as preventing the adhesion, aggregation, and activation of platelets, modulating EC functions, inhibiting the SMC proliferation, and accelerating vascular remodeling [64–67]. Like NO, PGI2 could also exert important platelet inhibitory effects and inhibit SMC proliferation, acting synergistically with NO in this regard [65, 68, 69]. Moreover, NO release of ECs could be potentiated by PGI2 [70].

Figure 10 shows the NO and PGI2 release amounts of HUVECs cultured on various samples. Obviously, the PTFE exhibited the lowest values of NO and PGI2 production. Compared to the PTFE, the PTFEPP promoted the release of NO (p < 0.001) and PGI2 (p < 0.001). In addition, the ECM/PTFEPP further significantly enhanced the production of NO (p < 0.001) and PGI2 (p < 0.05) in comparison with the PTFEPP. This was consistent with the results of previous studies where the introduction of functional groups from ECM was beneficial for the NO and PGI2 productions of HUVECs [27, 69]. After the heparin immobilization, the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP showed a similar NO level with the ECM/PTFEPP, while significantly higher than those of the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP (Figure 10A). Similar results had also been corroborated by Liu et al.[31], who investigated the influence of heparin density on the NO release activity of HUVECs. Their study suggested that, in comparison with unmodified samples, NO release amounts significantly decreased on the samples with high heparin densities (30.9 ± 3.4 μg/cm2 and 43.1 ± 5.1 μg/cm2). When the heparin densities decreased to 3–5 μg/cm2, the NO release level tended to rise, and a significant improvement was achieved. Furthermore, as discussed earlier, the introduction of heparin would damage the integrity of the ECM coating and thus offset its positive effects on HUVEC behaviors, including the NO and PGI2 production. However, in Figure 10B, no significant differences could be found among the ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP, thus indicating that heparin played a positive role in facilitating the PGI2 release of HUVECs. For the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, its PGI2 level was significantly lower than those of the ECM/PTFEPP and 5He-ECM/PTFEPP (p < 0.05), due to its low heparin density that was not sufficient to compensate for the negative effects of heparin immobilization process on the integrity and biological activities of ECM coating.

Figure 10.

The production levels of the NO (A) and the PGI2 (B) from HUVECs cultured on different samples.

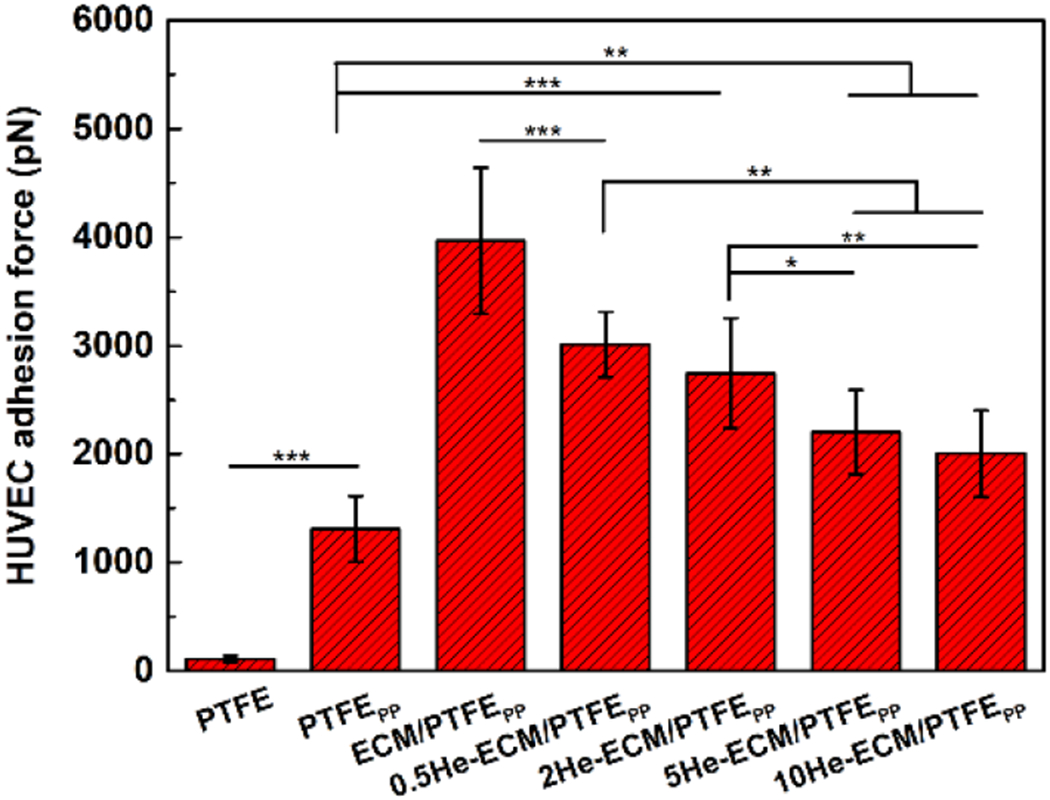

3.3.4. HUVEC adhesion force

In vivo, ECs of blood vessels are always exposed to physiological flow conditions, so they might be sloughed off if the adhesion strength is not strong enough [71, 72]. The EC-matrix adhesion, as a crucial mechanical phenomenon in biology, affects various EC behaviors, including growth, differentiation, and migration [39, 40, 73, 74]. Therefore, the excellent EC-substrate adhesion should be considered when designing vascular grafts. Quantitative results of HUVEC adhesion forces on different samples were shown in Figure 11. The forces values of the PTFE, PTFEPP, and ECM/PTFEPP were 108.15 ± 28.34 pN, 1306.67 ± 303.16 pN, and 3968.12 ± 673.24 pN, respectively. ECs adhere to the substrates primarily via integrins that could bind to external ligands in the ECM, such as collagen, fibronectin, vitronectin, and so forth. Integrin clusters normally provide the primary mechanical junctions between the actin cytoskeleton and the substrates via forming focal adhesions [71, 75]. For the PTFEPP, the existence of the PDA enhanced the adsorption of soluble adhesion proteins in the culture medium (e.g., vitronectin and fibronectin), thus its adhesion force value increased greatly when compared to the PTFE. After further introduction of the ECM coating, much more integrin-protein bonds brought about the highest adhesion force value of the ECM/PTFEPP, significantly higher than all other samples. Since the heparin would react with the functional groups of ECM coating, and EDC/NHS coupling chemistry could impact the original biological activities of ECM proteins, HUVEC adhesion forces of heparin-immobilized samples decreased. Correspondingly, the force values decreased along with the increase of heparin density from 3012.68 ± 300.36 pN for the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP to 2003.26 ± 400.19 pN for the 10He-ECM/PTFEPP. Moreover, it should be noted that the cell adhesion force was also influenced directly by the cell spreading, as well as the topography and stiffness of the substrates [17, 73, 76].

Figure 11.

HUVEC adhesion forces on different samples.

3.4. HUASMC performances

3.4.1. HUASMC adhesion, proliferation, and viability

In natural blood vessels, healthy SMCs contribute to maintaining a normal structure and functions of the ECs, while excessive proliferation of SMCs results in late hyperplasia and increases the lumen loss, thereby narrowing the arteries [77]. Hence, in addition to ECs, the performances of HUASMCs on various samples were examined as well.

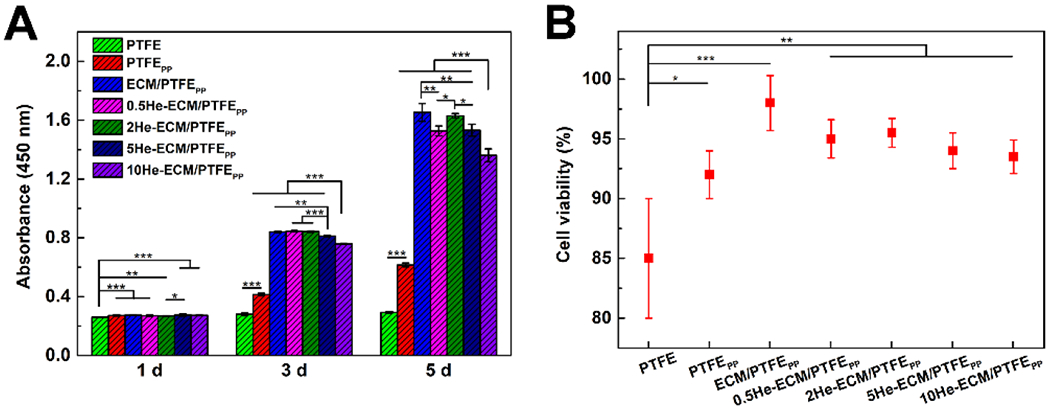

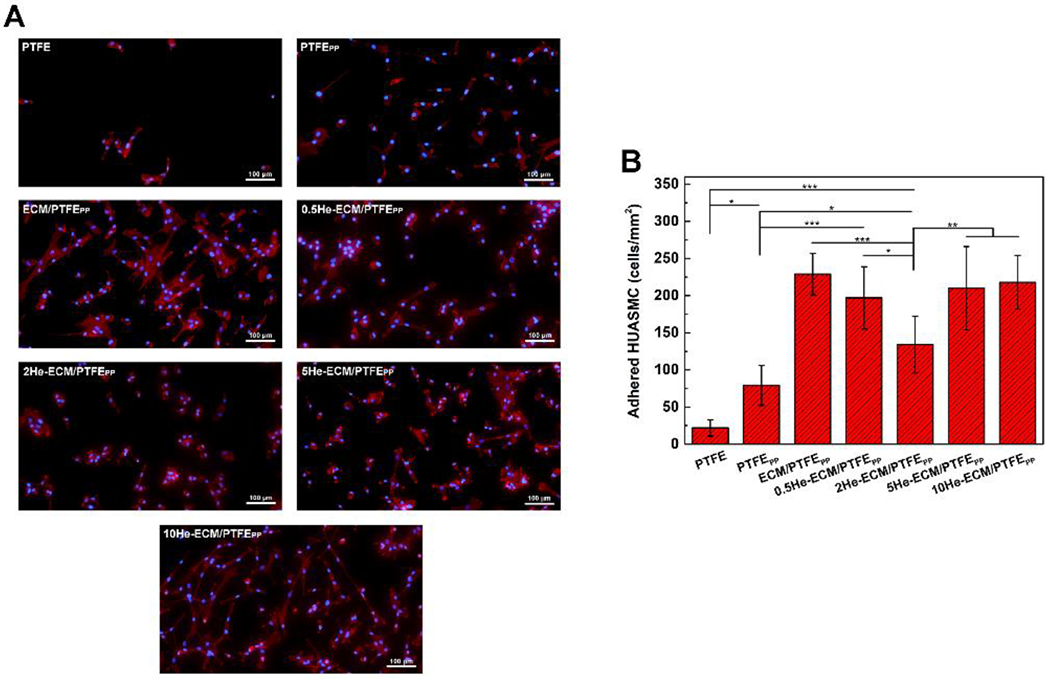

After 6 h incubation, the fluorescence images of adhered HUASMCs on various samples were taken and shown in Figure 12A. It could clearly be seen that most of adhered cells on the PTFE, PTFEPP 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 5He-ECM/PTFEPP exhibited a round shape, indicating their weak and unstable adhesion status [78]. In contrast, plenty of HUASMCs on the ECM/PTFEPP and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP spread noticeably and presented in the shape of an elongated spindle. From Figure 12B, the PTFE presented the lowest value of 22 cells/mm2. After surface modification, the HUASMC density significantly increased to 79 cells/mm2 for the PTFEPP (p < 0.05), further up to 229 cells/mm2 for the ECM/PTFEPP (p < 0.001), primarily because of the abundant binding sites provided by PDA, PEI, absorbed plasma proteins, and ECM proteins.

Figure 12.

Fluorescence images (A) and numbers (B) of adhered HUASMCs on different samples at 6 h.

Besides the anticoagulation and anti-inflammatory functions, heparin has a crucial advantage of inhibiting intimal hyperplasia when applied with an appropriate dosage. It was likely attributed to that heparin could inhibit the production of proteinases, which was related to vascular SMC matrix metabolism, thus leading to poor vascular SMC adhesion [32, 53]. Compared with the ECM/PTFEPP, 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP exhibited weakened HUASMC adhesion densities of 197, 210, and 218 cells/mm2, respectively. The 2He-ECM/PTFEPP showed a significantly lower cell density of 134 cells/mm2. For the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, the fewest functional groups of the ECM coating were occupied due to its lowest heparin density, leading to no statistical difference between it and the ECM/PTFEPP. In the meanwhile, the high heparin densities of the 5He-ECM/PTFEPP and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP enhanced the surface hydrophilicity and provided biological sites for the HUASMC recognition and adhesion. Therefore, the results suggested that the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP (with a relatively low heparin density) possessed better inhibition effects on SMC adhesion, in agreement with the conclusions from previous studies [31, 62, 79].

After culture for 3 days, the morphologies of adhered HUASMCs on different samples were shown in Figure 13A. On the PTFE, HUASMCs presented an apoptotic shrinkage morphology and appeared more isolated at a low density, whereas great changes were observed on other samples where HUVSMCs grew well, and most cells were spindle shaped. It’s noteworthy that relatively higher proportions of cells on the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP and 2He-ECM/PTFEPP were in a round or “contractile” shape, indicating the inhibited biological activity of HUASMCs. From Figure 13B, it could be easily found that absorbance values of the PTFE were always the lowest throughout the entire culture period. After the introduction of PDA/PEI and subsequent ECM coating, the absorbance values of the PTFEPP and ECM/PTFEPP increased significantly, as well as the HUASMC viability (Figure 13C). The ECM/PTFEPP exhibited the highest absorbance values among all the samples, suggesting the best HUASMC proliferation on it. Similar to the HUVEC, heparin inhibited the HUASMC proliferation to some degree, but showed no significant effects on the HUASMC viability (Figure 13C). According to previous studies, the inhibition effects of heparin on SMC proliferation were likely attributed to the neutralization of angiogenic growth factors (like bFGF) and the expression of contractile HUVSMC phenotype markers [47, 79]. Meanwhile, heparin could also enhance the recruitment of SMCs after binding to the stromal cell-derived factor-1a (SDF-1a) [32]. Therefore, besides its molecular weight, sulfation degree and disaccharide composition of the heparin [62], the heparin dosage that determines both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on SMC proliferation should be carefully selected [31, 79]. From the statistical results, compared with the high heparin density (10He-ECM/PTFEPP), the low heparin densities exhibited a more significant inhibitory effect on the proliferation of HUASMCs. The absorbance values of the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 5He-ECM/PTFEPP were 84.81%, 87.85%, and 85.28% at day 1; 84.93%, 87.23%, and 99.11% at day 3; and 98.31%, 89.06%, and 88.24% at day 5 respectively, of those of the 10He-ECM/PTFEPP. Collectively, except for the PTFE, the 2He-ECM/PTFEPP showed relatively low absorbance values during the culture period, demonstrating the weakened biological activities of the HUASMCs.

Figure 13.

(A) Fluorescence images of HUASMCs cultured on different samples after 3 days incubation. (B) Statistical results of HUASMC proliferation from the CCK-8 assay. (C) Statistical results of HUASMC viability from the live/dead assay at day 5.

3.4.2. HUASMC adhesion force

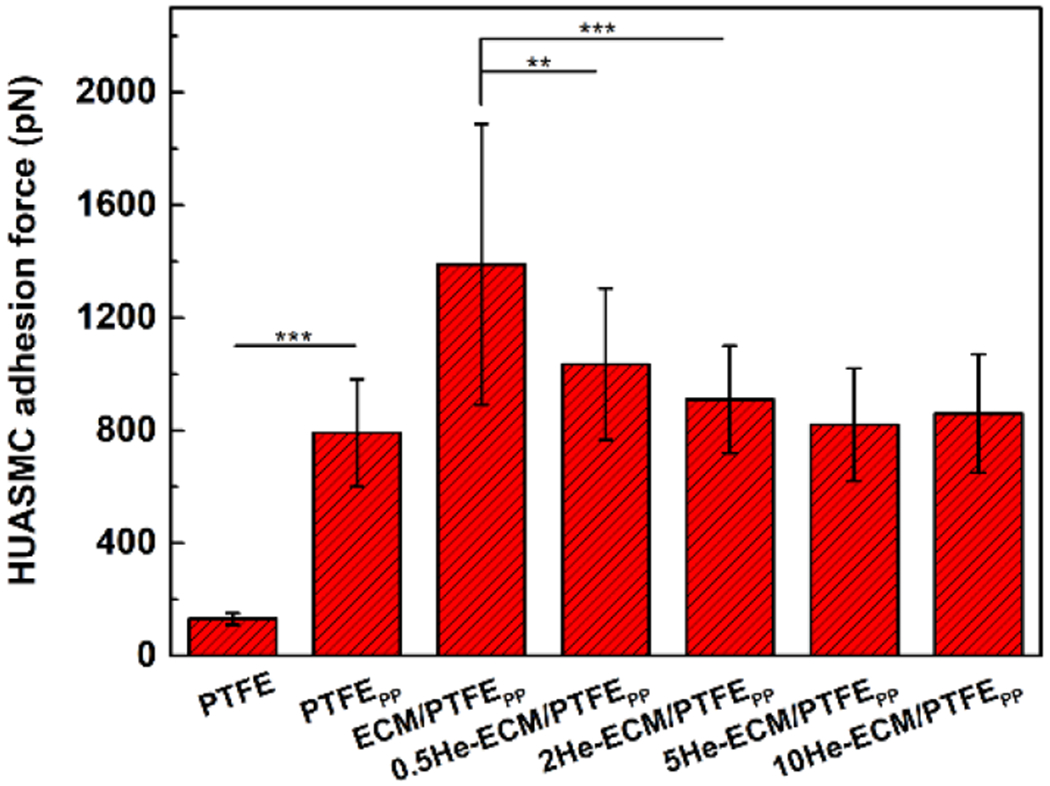

As shown in Figure 14, the HUASMC adhesion force results exhibited a similar trend with those of the HUVEC in Figure 11. The PTFE possessed the lowest value of 130.56 ± 20.34 pN, while the ECM-PTFEPP exhibited the highest value of 1389.23 ± 498.67 pN. For heparin-immobilized samples, the HUASMC adhesion forces were 1034.89 ± 269.09 pN, 910.34 ± 190.45 pN, 820.59 ± 200.42 pN, and 861.26 ± 212.78 pN for the 0.5He-ECM/PTFEPP, 2He-ECM/PTFEPP, 5He-ECM/PTFEPP, and 10He-ECM/PTFEPP, respectively, without significant differences among these samples, indicating that the HUASMC adhesion force was not sensitive to the heparin density. Furthermore, compared to the HUVEC, the HUASMC exhibited statistically lower force values on the same samples in the present study, in agreement with the observation of a previous study [40].

Figure 14.

HUASMC adhesion forces on different samples.

4. Conclusions

PTFE has been employed in the field of cardiovascular grafts for decades, but the poor long-term patency when it is applied for small-diameter vascular grafts limits its clinical applications. In this study, the co-deposition of PDA/PEI was applied to overcome the bio-inertness of PTFE, a nature-inspired ECM coating prepared by co-culture/decellularization of ECs and SMCs was then introduced to provide a bio-favorable environment. Moreover, heparin was immobilized to the ECM coating with an optimized density to selectively promote HUVEC proliferation but inhibit HUASMC growth and obtain the satisfactory hemocompatibility. In summary, a facile surface modification method with properties of inhibiting thrombosis formation, preventing intimal hyperplasia, and promoting endothelialization was proposed in the present study. This method has great potential for functionalizing super-hydrophobic and other kinds of biomaterials for the development of small-diameter vascular grafts.

Highlights.

The co-deposition of PDA/PEI was applied for PTFE functionalization.

A suitable dosage of heparin could optimize the functions of extracellular matrix.

The heparin-immobilized extracellular matrix exhibited favorable hemocompatibility.

Behaviors of endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell were selectively regulated.

The proposed method has great potential to modify various vascular biomaterials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2232019G-06 and 2232019A3-06) and 111 project (No. PB0719035) for the authors at Donghua University. The authors at University of Wisconsin-Madison would like to acknowledge the support by the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery (WID), Morgridge Institute for Research (MIR), the NHLBI of the National Institutes of Health (No. U01HL134655), and the Kuo K. and Cindy F. Wang Professorship. Chenglong Yu acknowledged the fellowship from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) under the Grant CSC No. 201906630070. The authors would also like to acknowledge Amy Freitag for her review comments and editorial assistance for this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Yalcin I, Horakova J, Mikes P, Sadikoglu TG, Domin R, Lukas D, Design of Polycaprolactone Vascular Grafts, Journal of Industrial Textiles, 45 (2016) 813–833. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zilla P, Bezuidenhout D, Human P, Prosthetic vascular grafts: Wrong models, wrong questions and no healing, Biomaterials, 28 (2007) 5009–5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ran XL, Ye ZY, Fu ML, Wang QL, Wu HD, Lin S, Yin TY, Hu TZ, Wang GX, Design, Preparation, and Performance of a Novel Bilayer Tissue-Engineered Small-Diameter Vascular Graft, Macromolecular Bioscience, 19 (2019) 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seifu DG, Purnama A, Mequanint K, Mantovani D, Small-diameter vascular tissue engineering, Nat. Rev. Cardiol, 10 (2013) 410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pashneh-Tala S, MacNeil S, Claeyssens F, The Tissue-Engineered Vascular Graft-Past, Present, and Future, Tissue Engineering Part B-Reviews, 22 (2016) 68–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang Z, Wang ZX, Liu SQ, Kodama M, Pore size, tissue ingrowth, and endothelialization of small-diameter microporous polyurethane vascular prostheses, Biomaterials, 25 (2004) 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mi HY, Jing X, Thomsom JA, Turng LS, Promoting endothelial cell affinity and antithrombogenicity of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) by mussel-inspired modification and RGD/heparin grafting, Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 6 (2018) 3475–3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sanchez PF, Brey EM, Briceno JC, Endothelialization mechanisms in vascular grafts, Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hui X, Geng X, Jia LJ, Xu ZQ, Ye L, Gu YQ, Zhang AY, Feng ZG, Preparation and in vivo evaluation of surface heparinized small diameter tissue engineered vascular scaffolds of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) embedded with collagen suture, Journal of Biomaterials Applications, 34 (2020) 812–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jayadev R, Sherwood DR, Basement membranes, Curr. Biol, 27 (2017) R207–R211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liliensiek SJ, Nealey P, Murphy CJ, Characterization of Endothelial Basement Membrane Nanotopography in Rhesus Macaque as a Guide for Vessel Tissue Engineering, Tissue Eng. Part A, 15 (2009) 2643–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pozzi A, Yurchenco PD, Lozzo RV, The nature and biology of basement membranes, Matrix Biol., 57-58 (2017) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang ZY, Teoh SH, Hong MH, Luo FF, Teo EY, Chan JKY, Thian ES, Dual-Microstructured Porous, Anisotropic Film for Biomimicking of Endothelial Basement Membrane, Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces, 7 (2015) 13445–13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kalluri R, Basement membranes: Structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis, Nat. Rev. Cancer, 3 (2003) 422–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Davis GE, Senger DR, Endothelial extracellular matrix - Biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization, Circulation Research, 97 (2005) 1093–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Poschl E, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, Saito K, Ninomiya Y, Mayer U, Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development, Development, 131 (2004) 1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yu CL, Xing MY, Sun SB, Guan GP, Wang L, In vitro evaluation of vascular endothelial cell behaviors on biomimetic vascular basement membranes, Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces, 182 (2019) 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yu CL, Xing MY, Wang L, Guan GP, Effects of aligned electrospun fibers with different diameters on hemocompatibility, cell behaviors and inflammation in vitro, Biomed. Mater, 15 (2020) 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yu CL, Guan GP, Glas S, Wang L, Li ZT, Turng LS, A biomimetic basement membrane consisted of hybrid aligned nanofibers and microfibers with immobilized collagen IV and laminin for rapid endothelialization, Bio-Des. Manuf, 19. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Syed O, Kim JH, Keskin-Erdogan Z, Day RM, El-Fiqi A, Kim HW, Knowles JC, SIS/aligned fibre scaffold designed to meet layered oesophageal tissue complexity and properties, Acta Biomaterialia, 99 (2019) 181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dall’Olmo L, Zanusso I, Di Liddo R, Chioato T, Bertalot T, Guidi E, Conconi MT, Blood Vessel-Derived Acellular Matrix for Vascular Graft Application, Biomed Research International, (2014) 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mancuso L, Gualerzi A, Boschetti F, Loy F, Cao G, Decellularized ovine arteries as small-diameter vascular grafts, Biomed. Mater, 9 (2014) 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tu QF, Zhao YC, Xue XQ, Wang J, Huang N, Improved Endothelialization of Titanium Vascular Implants by Extracellular Matrix Secreted from Endothelial Cells, Tissue Eng. Part A, 16 (2010) 3635–3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li JG, Zhang K, Wu JJ, Zhang LJ, Yang P, Tu QF, Huang N, Tailoring of the titanium surface by preparing cardiovascular endothelial extracellular matrix layer on the hyaluronic acid micro-pattern for improving biocompatibility, Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces, 128 (2015) 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zou D, Luo X, Han CZ, Li JA, Yang P, Li Q, Huang N, Preparation of a biomimetic ECM surface on cardiovascular biomaterials via a novel layer-by-layer decellularization for better biocompatibility, Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications, 96 (2019) 509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Langlois B, Belozertseva E, Parlakian A, Bourhim M, Gao-Li J, Blanc J, Tian L, Coletti D, Labat C, Ramdame-Cherif Z, Challande P, Regnault V, Lacolley P, Li ZL, Vimentin knockout results in increased expression of subendothelial basement membrane components and carotid stiffness in mice, Scientific Reports, 7 (2017) 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Han CZ, Luo X, Zou D, Li JA, Zhang K, Yang P, Huang N, Nature-inspired extracellular matrix coating produced by micro-patterned smooth muscle and endothelial cells endows cardiovascular materials with better biocompatibility, Biomater. Sci, 7 (2019) 2686–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vijayan VM, Tucker BS, Hwang PTJ, Bobba PS, Jun HW, Catledge SA, Vohra YK, Thomas V, Non-equilibrium organosilane plasma polymerization for modulating the surface of PTFE towards potential blood contact applications, Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 8 (2020) 2814–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Adipurnama I, Yang MC, Ciach T, Butruk-Raszeja B, Surface modification and endothelialization of polyurethane for vascular tissue engineering applications: a review, Biomater. Sci, 5 (2017) 22–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li X, Tang JY, Bao LH, Chen L, Hong FF, Performance improvements of the BNC tubes from unique double-silicone-tube bioreactors by introducing chitosan and heparin for application as small-diameter artificial blood vessels, Carbohydrate Polymers, 178 (2017) 394–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liu T, Liu Y, Chen Y, Liu SH, Maitz MF, Wang X, Zhang K, Wang J, Wang Y, Chen JY, Huang N, Immobilization of heparin/poly-L-lysine nanoparticles on dopamine-coated surface to create a heparin density gradient for selective direction of platelet and vascular cells behavior, Acta Biomaterialia, 10 (2014) 1940–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Aslani S, Kabiri M, HosseinZadeh S, Hanaee-Ahvaz H, Taherzadeh ES, Soleimani M, The applications of heparin in vascular tissue engineering, Microvasc. Res, 131 (2020) 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jing X, Mi HY, Salick MR, Cordie T, McNulty J, Peng XF, Turng LS, In vitro evaluations of electrospun nanofiber scaffolds composed of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and polyethylenimine, J. Mater. Res, 30 (2015) 1808–1819. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fowler P, Dizon GV, Tayo LL, Caparanga AR, Huang J, Zheng J, Aimar P, Chang Y, Surface Zwitterionization of Expanded Poly(tetrafluoroethylene) via Dopamine-Assisted Consecutive Immersion Coating, Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces, 12 (2020) 41000–41010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lv Y, Yang SJ, Du Y, Yang HC, Xu ZK, Co-deposition Kinetics of Polydopamine/Polyethyleneimine Coatings: Effects of Solution Composition and Substrate Surface, Langmuir, 34 (2018) 13123–13131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yao Y, Wang JN, Cui Y, Xu R, Wang ZH, Zhang J, Wang K, Li YJ, Zhao Q, Kong DL, Effect of sustained heparin release from PCL/chitosan hybrid small-diameter vascular grafts on anti-thrombogenic property and endothelialization, Acta Biomaterialia, 10 (2014) 2739–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhu JJ, Chen D, Du J, Chen XX, Wang JH, Zhang HB, Chen SH, Wu JL, Zhu TH, Mo XM, Mechanical matching nanofibrous vascular scaffold with effective anticoagulation for vascular tissue engineering, Compos. Pt. B-Eng, 186 (2020)13. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yuan HH, Qin JB, Xie J, Li BY, Yu ZP, Peng ZY, Yi BC, Lou XX, Lu XW, Zhang YZ, Highly aligned core-shell structured nanofibers for promoting phenotypic expression of vSMCs for vascular regeneration, Nanoscale, 8 (2016) 16307–16322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wu JD, Mao ZW, Gao CY, Controlling the migration behaviors of vascular smooth muscle cells by methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) brushes of different molecular weight and density, Biomaterials, 33 (2012) 810–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yu S, Gao Y, Mei X, Ren TC, Liang S, Mao ZW, Gao CY, Preparation of an Arg-Glu-Asp-Val Peptide Density Gradient on Hyaluronic Acid-Coated Poly(epsilon-caprolactone) Film and Its Influence on the Selective Adhesion and Directional Migration of Endothelial Cells, Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces, 8 (2016) 29280–29288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang LW, Fang F, Liu Y, Li J, Huang XJ, Facile preparation of heparinized polysulfone membrane assisted by polydopamine/polyethyleneimine co-deposition for simultaneous LDL selectivity and biocompatibility, Applied Surface Science, 385 (2016) 308–317. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Riaz T, Zeeshan R, Zarif F, Ilyas K, Muhammad N, Safi SZ, Rahim A, Rizvi SAA, Rehman IU, FTIR analysis of natural and synthetic collagen, Appl. Spectrosc. Rev, 53 (2018) 703–746. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yan SJ, Xu YY, Lin YJ, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Yilmaz G, Li Q, Turng LS, Ethanol-lubricated expanded-polytetrafluoroethylene vascular grafts loaded with eggshell membrane extract and heparin for rapid endothelialization and anticoagulation, Applied Surface Science, 511 (2020) 11. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sanden KW, Kohler A, Afseth NK, Bocker U, Ronning SB, Liland KH, Pedersen ME, The use of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy to characterize connective tissue components in skeletal muscle of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.), J. Biophotonics, 12 (2019) 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Luo RF, Wang X, Deng JC, Zhang H, Maitz MF, Yang L, Wang J, Huang N, Wang YB, Dopamine-assisted deposition of poly (ethylene imine) for efficient heparinization, Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces, 144 (2016) 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cheng C, Sun SD, Zhao CS, Progress in heparin and heparin-like/mimicking polymer-functionalized biomedical membranes, Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2 (2014) 7649–7672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bae S, DiBalsi MJ, Meilinger N, Zhang CQ, Beal E, Korneva G, Brown RO, Kornev KG, Lee JS, Heparin-Eluting Electrospun Nanofiber Yarns for Antithrombotic Vascular Sutures, Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces, 10 (2018) 8426–8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lavery KS, Rhodes C, McGraw A, Eppihimer MJ, Anti-thrombotic technologies for medical devices, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 112 (2017) 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rodrigues SN, Goncalves IC, Martins MCL, Barbosa MA, Ratner BD, Fibrinogen adsorption, platelet adhesion and activation on mixed hydroxyl-/methyl-terminated self-assembled monolayers, Biomaterials, 27 (2006) 5357–5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jeyachandran YL, Mielezarski E, Rai B, Mielczarski JA, Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation of Adsorption/Desorption of Bovine Serum Albumin on Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Surfaces, Langmuir, 25 (2009) 11614–11620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Arima Y, Iwata H, Effect of wettability and surface functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion using well-defined mixed self-assembled monolayers, Biomaterials, 28 (2007) 3074–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Xu LC, Bauer JW, Siedlecki CA, Proteins, platelets, and blood coagulation at biomaterial interfaces, Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces, 124 (2014) 49–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Xu XC, Li M, Liu Q, Jia ZJ, Shi YY, Cheng Y, Zheng YF, Ruan LQ, Facile immobilization of heparin on bioabsorbable iron via mussel adhesive protein (MAPs), Prog. Nat. Sci, 24 (2014) 458–465. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dang Q, Li CG, Jin XX, Zhao YJ, Wang X, Heparin as a molecular spacer immobilized on microspheres to improve blood compatibility in hemoperfusion, Carbohydrate Polymers, 205 (2019) 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kang LZ, Jia WB, Li M, Wang Q, Wang CD, Liu Y, Wang XP, Jin L, Jiang JJ, Gu GF, Chsen ZG, Hyaluronic acid oligosaccharide-modified collagen nanofibers as vascular tissue-engineered scaffold for promoting endothelial cell proliferation, Carbohydrate Polymers, 223 (2019) 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Aslani S, Kabiri M, Kehtari M, Hanaee-Ahvaz H, Vascular tissue engineering: Fabrication and characterization of acetylsalicylic acid-loaded electrospun scaffolds coated with amniotic membrane lysate, J. Cell. Physiol, 234 (2019) 16080–16096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Li X, Liu J, Yang T, Qiu H, Lu L, Tu Q, Xiong K, Huang N, Yang Z, Mussel-inspired “built-up” surface chemistry for combining nitric oxide catalytic and vascular cell selective properties, Biomaterials, 241 (2020) 119904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hosseinzadeh S, Nazari H, Sadegzadeh N, Babaie A, Kabiri M, Tasharrofi N, Zomorrod MS, Soleimani M, Polyethylenimine: A new differentiation factor to endothelial/cardiac tissue, J. Cell. Biochem, 120 (2019) 1511–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Anderson DEJ, Truong KP, Hagen MW, Yim EKF, Hinds MT, Biomimetic modification of poly(vinyl alcohol): Encouraging endothelialization and preventing thrombosis with antiplatelet monotherapy, Acta Biomaterialia, 86 (2019) 291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Coelho-Sampaio T, Tenchov B, Nascimento MA, Hochman-Mendez C, Morandi V, Caarls MB, Altankov G, Type IV collagen conforms to the organization of polylaminin adsorbed on planar substrata, Acta Biomaterialia, 111 (2020) 242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Nie CX, Ma L, Cheng C, Deng J, Zhao CS, Nanofibrous Heparin and Heparin-Mimicking Multilayers as Highly Effective Endothelialization and Antithrombogenic Coatings, Biomacromolecules, 16 (2015) 992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yang ZL, Tu QF, Wang J, Huang N, The role of heparin binding surfaces in the direction of endothelial and smooth muscle cell fate and re-endothelialization, Biomaterials, 33 (2012) 6615–6625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kruger-Genge A, Fuhrmann R, Jung F, Franke RP, Effects of different components of the extracellular matrix on endothelialization, Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc, 64 (2016) 867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ozcelik O, Algul S, Nitric oxide levels in response to the patients with different stage of diabetes, Cell. Mol. Biol, 63 (2017) 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Post A, Wang E, Cosgriff-Hernandez E, A Review of Integrin-Mediated Endothelial Cell Phenotype in the Design of Cardiovascular Devices, Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 47 (2019) 366–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wang DF, Xu YY, Wang LX, Wang XF, Yan SJ, Yilmaz G, Li Q, Turng LS, Long-term nitric oxide release for rapid endothelialization in expanded polytetrafluoroethylene small-diameter artificial blood vessel grafts, Applied Surface Science, 507 (2020) 10. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Elnaggar MA, Han DK, Joung YK, Nitric oxide releasing lipid bilayer tethered on titanium and its effects on vascular cells, J. Ind. Eng. Chem, 80 (2019) 811–819. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Cahill PA, Redmond EM, Vascular endothelium - Gatekeeper of vessel health, Atherosclerosis, 248 (2016) 97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Li JA, Zhang K, Wu JJ, Liao YZ, Yang P, Huang N, Co-culture of endothelial cells and patterned smooth muscle cells on titanium: Construction with high density of endothelial cells and low density of smooth muscle cells, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 456 (2015) 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Silva BR, Paula TD, Paulo M, Bendhack LM, Nitric Oxide Signaling and the Cross Talk with Prostanoids Pathways in Vascular System, Med. Chem, 13 (2017) 319–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Christ KV, Turner KT, Methods to Measure the Strength of Cell Adhesion to Substrates, J. Adhes. Sci. Technol, 24 (2010) 2027–2058. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Farhadifar R, Roper JC, Algouy B, Eaton S, Julicher F, The influence of cell mechanics, cell-cell interactions, and proliferation on epithelial packing, Curr. Biol, 17 (2007) 2095–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Yu S, Mao ZW, Gao CY, Preparation of gelatin density gradient on poly(epsilon-caprolactone) membrane and its influence on adhesion and migration of endothelial cells, J. Colloid Interface Sci, 451 (2015) 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Stroka KM, Aranda-Espinoza H, Effects of Morphology vs. Cell-Cell Interactions on Endothelial Cell Stiffness, Cell. Mol. Bioeng, 4 (2011) 9–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wood JA, Liliensiek SJ, Russell P, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ, Biophysical Cueing and Vascular Endothelial Cell Behavior, Materials, 3 (2010) 1620–1639. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Yim EKF, Darling EM, Kulangara K, Guilak F, Leong KW, Nanotopography-induced changes in focal adhesions, cytoskeletal organization, and mechanical properties of human mesenchymal stem cells, Biomaterials, 31 (2010) 1299–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Shen FY, Zhu Y, Li X, Luo RF, Tu QF, Wang J, Huang N, Vascular cell responses to ECM produced by smooth muscle cells on TiO2 nanotubes, Applied Surface Science, 349 (2015) 589–598. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Zheng WW, Liu M, Qi HS, Wen CY, Zhang C, Mi JL, Zhou X, Zhang L, Fan DD, Mussel-inspired triblock functional protein coating with endothelial cell selectivity for endothelialization, J. Colloid Interface Sci, 576 (2020) 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Tan JY, Cui YY, Zeng Z, Wei L, Li L, Wang HR, Hu HY, Liu T, Huang N, Chen JY, Weng YJ, Heparin/poly-l-lysine nanoplatform with growth factor delivery for surface modification of cardiovascular stents: The influence of vascular endothelial growth factor loading, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 108 (2020) 1295–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]