Abstract

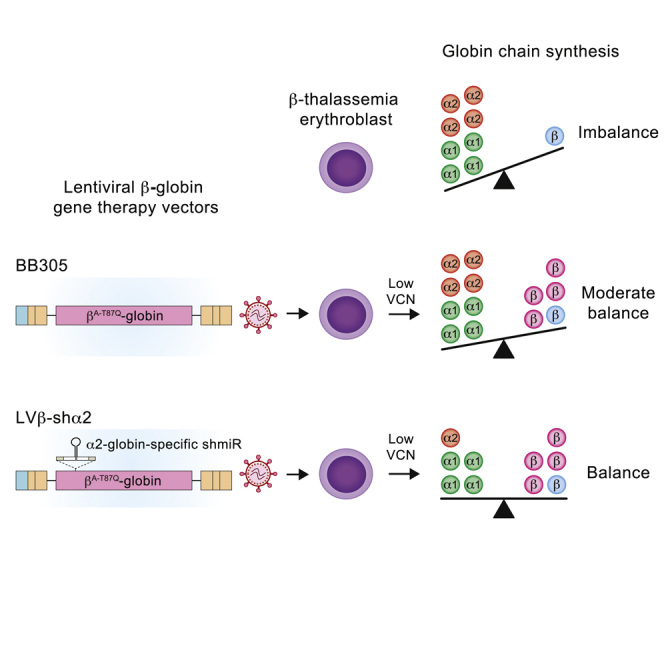

A primary challenge in lentiviral gene therapy of β-hemoglobinopathies is to maintain low vector copy numbers to avoid genotoxicity while being reliably therapeutic for all genotypes. We designed a high-titer lentiviral vector, LVβ-shα2, that allows coordinated expression of the therapeutic βA-T87Q-globin gene and of an intron-embedded miR-30-based short hairpin RNA (shRNA) selectively targeting the α2-globin mRNA. Our approach was guided by the knowledge that moderate reduction of α-globin chain synthesis ameliorates disease severity in β-thalassemia. We demonstrate that LVβ-shα2 reduces α2-globin mRNA expression in erythroid cells while keeping α1-globin mRNA levels unchanged and βA-T87Q-globin gene expression identical to the parent vector. Compared with the first βA-T87Q-globin lentiviral vector that has received conditional marketing authorization, BB305, LVβ-shα2 shows 1.7-fold greater potency to improve α/β ratios. It may thus result in greater therapeutic efficacy and reliability for the most severe types of β-thalassemia and provide an improved benefit/risk ratio regardless of the β-thalassemia genotype.

Keywords: gene therapy, thalassemias, lentiviral vector, shRNAmir, globin, BB305, LVβ-shα2, RNA inteference, insertional mutagenesis, hemoglobin disorder

Graphical abstract

Nualkaew et al. show that LVβ-shα2 reduces α2-globin mRNA expression in erythroid cells while keeping α1-globin mRNA levels unchanged and βA-T87Q-globin gene expression identical to the parent vector. Compared with the first βA-T87Q-globin lentiviral vector that has received conditional marketing authorization, BB305, LVβ-shα2 shows 1.7-fold greater potency to improve α/β ratios. It may thus result in greater therapeutic efficacy and reliability for the most severe types of β-thalassemia and provide an improved benefit/risk ratio regardless of the β-thalassemia genotype.

Introduction

β-Thalassemia is the result of reduced or absent β-globin chain synthesis.1,2 During normal erythropoiesis, β-globin is synthesized in equimolar quantities with α-globin. Two chains of each protein associate to form the tetrameric adult hemoglobin (HbA; α2β2). In β-thalassemia, a quantitative reduction or absence of β-globin chain synthesis disrupts the α:β-globin chain balance, leading to accumulation of unpaired α-globin in developing erythrocytes. Excess α-globin forms toxic aggregates, causing apoptosis of immature red blood cells (RBCs).3 The most severe forms of β-thalassemia manifest as dyserythropoiesis and hemolytic anemia, requiring monthly blood transfusions and lifelong iron chelation therapy.

Several lentiviral β-globin gene therapy vectors (LVβs) encompassing elements of the locus control region (LCR)4 are in clinical trials for β-hemoglobinopathies.5,6 Notably, the LentiGlobin BB305 gene therapy vector, encoding βA-T87Q-globin, originally designed by Leboulch et al.7 and Pawliuk et al.8 to inhibit hemoglobin S (HbS) polymerization, has achieved clinical efficacy and safety in a large number of transfusion-dependent individuals with β-thalassemia9, 10, 11, 12 and sickle cell disease in phase II and III trials.13,14 With regard to gene therapy for β-thalassemia, virtually all individuals with β-thalassemia with residual β-globin synthesis (non-β0/β0 genotype) (e.g., HbE/β0-thalassemia), have discontinued transfusions following BB305 gene therapy, with near-normal blood Hb levels.9,11,12 Importantly, molecular and cellular hallmarks of dyserythropoiesis were corrected in individuals who achieved near-normal blood Hb values. As a result, autologous hematopoietic CD34+ cells transduced with BB305 are the first gene therapy product (Zynteglo) to be granted conditional approval in Europe for transfusion-dependent non-β0/β0 genotype individuals.15

However, β0/β0-genotype individuals have been proven to be more challenging to treat with BB305 gene therapy.9, 10, 11, 12 Only a subset of β0/β0-genotype individuals achieved transfusion independence, although most displayed a decrease in transfusion requirements.9,10,12,16 The clinical efficacy of lentiviral β-globin gene therapy vectors is directly correlated with the number of proviral integration events in hematopoietic cells and overall output of therapeutic β-globin chain synthesis.11,17 Achieving an optimal therapeutic effect in all β0/β0-genotype individuals, who have the greatest requirement for therapeutic β-globin output, would benefit from a lentiviral vector capable of minimizing the detrimental effects of free α-globin chains while continuing to express high levels of βA-T87Q-globin in an erythroid-specific manner. Such a combination vector would theoretically result in greater therapeutic efficacy and reliability at lower vector copy numbers (VCNs) than BB305. Reaching the therapeutic threshold at lower VCNs would reduce the risk of untoward insertional mutagenesis for all individuals with β-thalassemia regardless of genotype.

To enhance the therapeutic efficacy of the BB305 gene therapy vector for the most severe β0/β0-genotype individuals, we developed a novel multiplexed lentiviral β-globin gene vector that allows coordinated expression of the therapeutic βA-T87Q-globin gene with concomitant reduction in α-globin chain synthesis. Our approach was guided by the knowledge that co-inheritance of an α-thalassemia trait along with a variety of β-thalassemia mutations reduces the clinical severity of β-thalassemia. A single α-globin gene deletion (−α/αα) has a minimal effect, but double (−α/−α or –/αα) or triple (–/−α) α-globin gene deletions have a major beneficial effect on disease severity by normalizing α:β-globin chain balance and minimizing the harmful effects of free α-globin chains.18, 19, 20, 21

Here we modified LentiGlobin BB305 by inserting a miR-30 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression cassette into intron 2 of the βA-T87Q-globin gene to derive the LVβ-shRNA vector, allowing stable erythroid-specific expression of functional shRNA from a common primary transcript. We further configured the LVβ-shRNA vector to specifically target the human α2-globin (HBA2) mRNA to generate the LVβ-shα2 gene therapy vector. We demonstrate that the LVβ-shα2 vector yields a high viral titer, transduction efficiency, and erythroid βA-T87Q-globin gene expression equivalent to the parent BB305 vector. Notably, LVβ-shα2 shows the additional property of decreasing human α2-globin mRNA levels without affecting α1-globin (HBA1) mRNA expression levels in transduced human erythroid cell lines and primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells derived from normal individuals and those with β-thalassemia. Importantly, the LVβ-shα2 vector is able to achieve a greater degree of correction of α/β-globin mRNA ratios in cells from individuals with β-thalassemia at identical VCNs compared with the parent BB305. We define a novel therapeutic strategy that could improve gene therapy outcomes in individuals with β-thalassemia irrespective of genotype.

Results

Generation of the LVβ gene therapy vector carrying a functional intron-encoded miR30-shRNA expression cassette

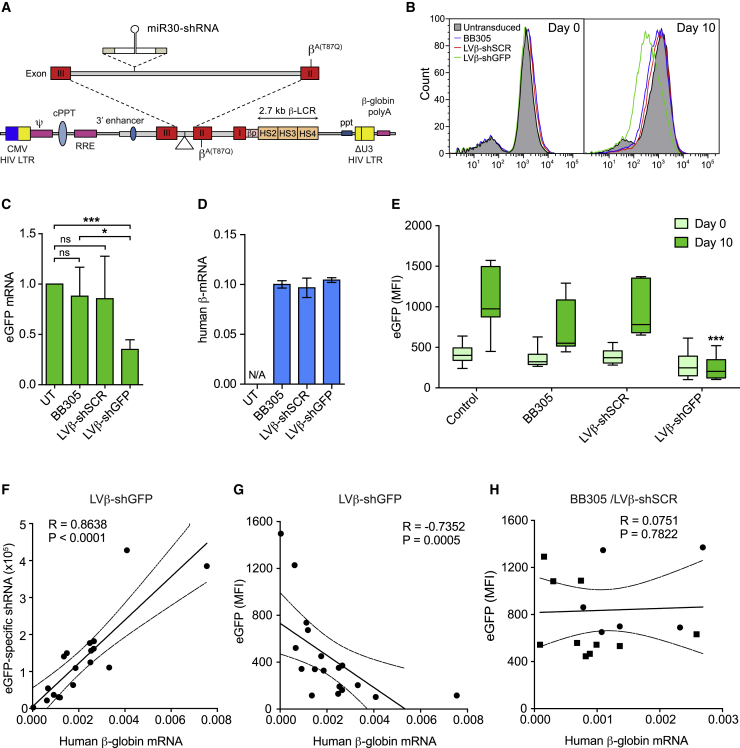

To examine whether the LentiGlobin BB305 vector could be used to deliver miR30-shRNA expression cassettes embedded in an intron of the vector-bearing βA-T87Q-globin gene (Figure 1A; Figure S1), LVβ-shRNA vectors carrying the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-specific shRNA (LVβ-shGFP) and scrambled negative control (LVβ-shSCR) vectors were generated and validated in the murine erythro-leukemia (MEL)-βEGFP reporter cell line, in which EGFP expression is driven by the human β-globin promoter in the context of a chromosomally integrated, large segment of the human β-globin locus.22,23 Following viral transduction with BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shGFP vectors, bulk-transduced MEL-βEGFP cells were induced to undergo erythroid differentiation after exposure to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). We observed that LVβ-shGFP significantly reduced EGFP fluorescence and mRNA expression, whereas BB305 and LVβ-SCR vectors had no significant effect (Figures 1B and 1C).

Figure 1.

The LVβ gene therapy vector containing intronic miR30-shGFP reduces target gene expression in erythroid cells

(A) Schematic of the LVβ gene therapy vector, LentiGlobin BB305, modified to express the miR30-shRNA cassette. (B) Representative histograms of EGFP expression by MEL-βEGFP cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shGFP vectors at equivalent MOIs. (C and D) Relative EGFP mRNA expression (C, n = 3) and βA-T87Q-globin mRNA expression (D) in transduced MEL-βEGFP cells normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three separate experiments relative to untransduced (UT) cells following 10 days of DMSO induction. Significance was calculated by unpaired Student’s t test; ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of individual MEL-βEGFP clones (n = 10) transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shGFP vectors. Data represent median (lines), the 25th and 75th percentiles (boxes), and the 90th and 10th percentiles (error bars) (∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001). (F–H) Correlation analysis of (F) shGFP expression to β-globin mRNA, (G) EGFP fluorescence to β-globin mRNA in LVβ-shGFP-transduced clones, and (H) EGFP MFI to β-globin mRNA in BB305-transduced (squares) and LVβ-shSCR-transduced (circles) clones following 10 days of DMSO induction. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman rank method. Scatterplot linear regression lines with 95% confidence intervals (dotted lines) are displayed for (F)–(H). A positive correlation between shGFP expression and β-globin mRNA expression in LVβ-shGFP clones was detected (n = 18, R = 0.864, p < 0.0001). A negative correlation between EGFP MFI and LV β-shGFP β-globin mRNA expression was detected (n = 18, R = −0.735, p < 0.0005). EGFP MFI and β-globin mRNA expression in BB305-transduced (squares) and LVβ-shSCR-transduced (circles) clones did not correlate (n = 16, R = 0.0751, p = 0.7811).

Next, βA-T87Q-globin mRNA expression was measured following erythroid differentiation of the transduced MEL-βEGFP cells. We observed that βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression by the LVβ-shGFP and LVβ-shSCR vectors was equivalent to the parent BB305 vector (Figure 1D). To assess whether the miR30-shRNA expression cassette may yield alternative or aberrant mRNA splicing events, βA-T87Q-globin expression was analyzed by RT-PCR using primers located on either side of the human βA-T87Q-globin exon 2-3 boundary (Figure S2A). A single PCR product of the expected size (168 bp), representing the correctly spliced βA-T87Q-globin mRNA, was identified in cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shGFP vectors (Figure S2B). These results indicate that inserting the miR30-shRNA expression cassette at the intervning sequence 2 (IVS2) breakpoint site allows normal mRNA splicing and does not result in aberrant splice products detected by the assay.

To investigate the relationship between βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression and functional EGFP shRNA, transduced MEL-βEGFP clones (n = 10) were analyzed following erythroid differentiation. Consistent with the bulk-transduced cells, the LVβ-shGFP vector significantly diminished EGFP fluorescence in individual clones (Figure 1E). In LVβ-shGFP-transduced clones, EGFP shRNA and βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression levels showed a significant positive correlation between them (p < 0.0001) (Figure 1F), whereas βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression levels and EGFP fluorescence displayed a significant negative correlation (p = 0.0005) (Figure 1G). As expected, there was no correlation between βA-T87Q-globin expression and EGFP fluorescence in BB305- or LVβ-shSCR-transduced clones (p = 0.7811) (Figure 1H). These results demonstrate that the LVβ-shGFP vector produces a functional intron-encoded shRNA whose amount depends on the expression level of the βA-T87Q-globin transgene.

Validation in K562 cells of LVβ-shRNA lentiviral vectors tailored to reduce human α-globin expression

We then explored the possibility of using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to reduce human α-globin gene expression. Comparative analysis of 5 siRNAs targeting different α-globin locations was performed following electroporation into K562 cells. Four siRNAs were identified to significantly reduce human α-globin mRNA (Figure S3). Because si-α3 and si-α4 showed a suitable reduction in human α-globin expression, they were configured into the LVβ-shRNA vector system to generate the LVβ-shα1/2 and LVβ-shα2 vectors, respectively. Because of a number of nucleotide differences between human α1 and α2 globin mRNAs in their 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), the LVβ-shα2 was designed to specifically target human α2-globin mRNA without affecting human α1-globin mRNA, whereas LVβ-shα1/2 targets the third exon of the α1-globin and α2-globin genes (Figure 2A). LVβ-shRNA vectors yielded titers equivalent to that of the parental BB305 vector (Figure S4).

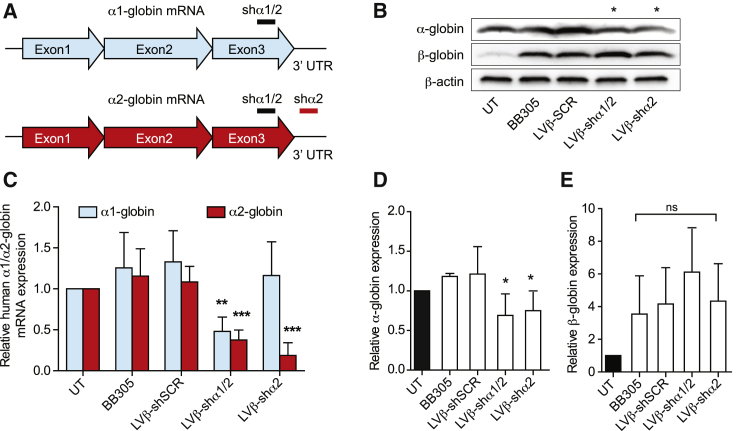

Figure 2.

The LVβ gene therapy vector containing the miR30-shRNA expression cassette can be used to reduce α-globin expression in K562 cells

(A) Schematic of α-globin mRNA showing the location of the shα1/2 and shα2 target sites. (B) Relative α1 and α2-globin mRNA expression levels in K562 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, LVβ-shα1/2, and LVβ-shα2 vectors at equivalent MOIs following 5 days of hemin induction. α1/α2-globin mRNA expression levels were calculated by normalizing to β-actin in UT controls. (C) Representative western blot analysis of K562 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, LVβ-shα1/2, and LVβ-shα2 vectors following hemin induction. (D and E) Relative quantification of (D) α-globin and (E) β-globin chains. The level of β-actin expression in UT cells was used to normalize signal intensity values between samples. Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments and vector preparations. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001).

The human α-globin-specific mRNA knockdown activity of the LVβ-shα1/2 and LVβ-shα2 vectors was evaluated in K562 cells by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 2B). The LVβ-shα1/2 vector reduced α1- and α2-globin mRNA by approximately 50%. Notably, the LVβ-shα2 vector reduced α2-globin mRNA expression by 78% ± 13% (p < 0.001), whereas α1-globin mRNA remained unaffected (Figure 2B). Using primers designed to amplify across the exon 2-to-exon 3 junction, the correctly spliced human βA-T87Q-globin mRNA was detected as a single RT-PCR product (168 bp) (Figure S2C). Importantly, western blot analysis of proteins extracted from transduced K562 cells confirmed a substantial reduction of α-globin chain expression by the LVβ-shα1/2 and LVβ-shα2 vectors (35% ± 15% and 30% ± 18%, respectively; p < 0.05) compared with negative control groups (Figures 2C and 2D), whereas β-globin expression remained unchanged at the mRNA and protein levels (Figures 2C and 2E). To ensure that the α-globin knockdown would not be complete, we decided to focus on the LVβ-shα2 vector, which specifically targets the α2-globin mRNA, leaving α1-globin expression untouched.

The LVβ-shα2 lentiviral vector reduces α2-globin expression in β0-HUDEP-2 cells

The HUDEP-2 cell line recapitulates the human adult erythroid differentiation program.24 To evaluate LVβ-shRNA vectors in a sustainable β-thalassemia environment, a HUDEP-2 cell line containing biallelic β0-globin mutations, β0-HUDEP-2, was created using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing (Supplemental materials and methods). The absence of β-globin chain synthesis was confirmed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis (Figure 3C). β0-HUDEP-2 cells failed to progress beyond the Poly-E stage of differentiation and morphologically exhibited an increased level of cell death by day 8, recapitulating the β-thalassemia environment (Figures 3A and 3B).

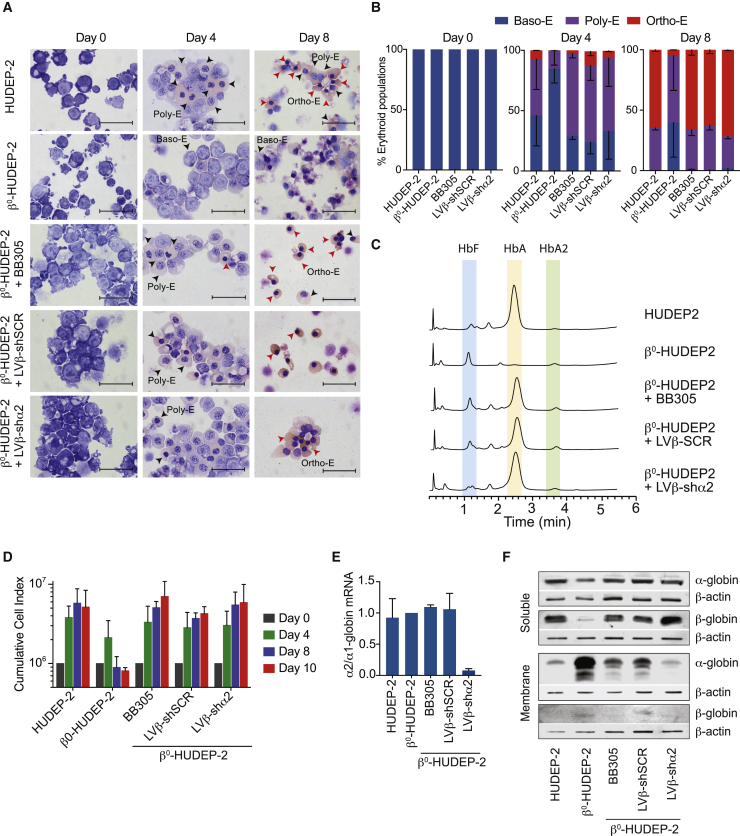

Figure 3.

Analysis of β0-HUDEP-2 differentiation following transduction with the LVβ-shα2 lentiviral vector

(A) Morphological changes of HUDEP-2 and β0-HUDEP-2 cells following differentiation. Day 0, day 4, and day 8 samples were stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa. Arrows indicate advanced stages of erythroid differentiation (Ortho-E, Poly-E, and Baso-E are indicated on day 4 and day 8). Magnification: 1,000×; scale bars, 25 μm. (B) Erythroid progenitor populations on day 0, day 4, and day 8 of differentiation. Cells at different stages of differentiation were counted from images taken at 400× magnification from cytospin slides. Percentages of different erythroid populations (Ortho-E, Poly-E, and Baso-E) for day 4 and day 8 of differentiation are shown (n = 2, >200 cells counted per cytospin). (C) Hemoglobin variant analysis by HPLC of the soluble cellular fraction obtained from HUDEP-2 and β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shα2 on day 10 of erythroid differentiation. (D) Cumulative cell index of HUDEP-2, β0-HUDEP-2, and β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shα2 vectors over a 10 day time-course of erythroid differentiation. Data are presented as mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (E) Relative α2/α1-globin mRNA expression levels in HUDEP-2, β0-HUDEP-2, and β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shα2 vectors. (F) Western blot analysis of soluble and membrane fractions of HUDEP-2, β0-HUDEP-2, and transduced β0-HUDEP-2 cells after 10 days of erythroid differentiation. The antibody used for β-globin detection cross-reacts with δ-globin and therefore contributes to the faint band observed with β0-HUDEP-2 cells.

We next evaluated erythroid maturation of β0-HUDEP-2 cells following transduction with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shα2 vectors at equivalent multiplicities of infection (MOIs). Initial transduction efficiency, as measured by intracellular β-globin staining 48 h after transduction, ranged from 27.0%–40.7%, and after one cryopreservation cycle, the majority of transduced β0-HUDEP-2 cells (88.3% ± 6.0%) expressed the βA-T87Q-globin transgene (data not shown). Therefore, βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression appears to provide a survival advantage in bulk-transduced β0-HUDEP-2 cells. This is in agreement with the observations made by Miccio et al.,25 who have reported a selective survival advantage of genetically corrected β-thalassemic erythroid progenitor cells in mice. A similar survival advantage because of βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression was also observed during a 10-day time course of erythroid differentiation with β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, or LVβ-shα2 vector (Figure 3D). Morphological analysis of β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, or LVβ-shα2 vector revealed a significant reduction in the proportion of Baso-E and a concomitant increase in Ortho-E, which was equivalent to normal HUDEP-2 cells (Figures 3A and 3B). Importantly, these results demonstrate that βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression by either of the three vectors is sufficient to restore β0-HUDEP-2 erythroid maturation to the normal range.

Next, β0-HUDEP-2 cells were transduced at two different MOIs to result in low and high VCNs (1–2 and 12–15), and α- and β-globin mRNA expression levels were assessed by qRT-PCR analysis during the expansion phase. Remarkably, the LVβ-shα2 vector reduced α2-globin transcription levels by more than 3- and more than 20-fold, respectively, compared with that observed in untreated and BB305- and LVβ-shSCR-transduced β0-HUDEP-2 cells (Figure S5). Accordingly, the reduction in α2-globin mRNA was reflected in the reduction of the α2/α1-globin mRNA ratio (by up to ~95%) by the LVβ-shα2 vector, whereas α1-globin mRNA levels were equivalent in BB305- and LVβ-shSCR-transduced β0-HUDEP-2 cells (Figure 3E; Figure S5). Similarly, α- to β-globin mRNA ratios in LVβ-shα2-transduced cells decreased by approximately 25% (1–2 VCNs) and 50% (12–15 VCNs) (Figure S5). Because unpaired α-globin chains precipitate and are thus excluded from the water-soluble protein fraction, we also prepared the water-insoluble fraction for globin chain examination. Western blot analysis demonstrated reduced levels of α-globin chains in the water-insoluble cell fraction of β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with BB305, LVβ-shSCR, or LVβ-shα2. This was the result of a greater degree of α-globin chain assembly into hemoglobin complexes resulting from βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression from BB305 and LVβ-shSCR. In the case of β0-HUDEP-2 cells transduced with LVβ-shα2, the amount of α-globin chain in the water-insoluble fraction was further reduced to normal levels through the combined effects of βA-T87Q-globin transgene expression and decreased α2-globin chain synthesis (Figure 3F).

LVβ-shα2 normalizes α/β-globin mRNA ratios in primary human erythroid cells from individuals with β-thalassemia by decreasing α2-globin mRNA levels

CD34+ cells from human cord blood (CB) and individuals with β-thalassemia (n = 2) were transduced at clinically relevant VCNs with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, or LVβ-shα2 vector (Figure S6). We chose to perform experiments in cells from individuals with HbE/β-thalassemia because use of non-transduced β0/β0 cells would not have provided a negative control for α/β mRNA ratios following vector transduction because this cell population does not properly differentiate and survive during in vitro erythroid differentiation.26 Furthermore, transduction of cells from individuals with β0/β0-thalassemia with β-globin gene expressing vectors is sufficient to rescue erythroid cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro, indistinguishably from normal cells.26 Thus, a reduction in the α/β mRNA ratio by co-expression of α-globin-specific shRNAs would not produce further observable phenotypic correction in vitro.

Erythroid differentiation profiles of transduced CD34+ cells were determined by measuring the percentages of erythroid precursor cells (Figure 4A). Following erythroid differentiation, no gross differences were found between transduced erythroblasts based on the cell surface expression profiles of erythroid markers (Figure 4B). The cell surface expression profile of glycophorin A (GPA)+ cells followed the generally accepted differentiation dynamics with CD36 and CD71 cell surface expression already present on erythroblasts, increasing during differentiation but decreasing at the end of differentiation. The final stages of differentiation were associated with a reduction in cell volume, as seen by a decrease in forward scatter (FSC) (Figure 4A). These data indicates that the LVβ-shSCR or LVβ-shα2 vectors were not associated with any deleterious effects on erythroid differentiation, as assessed over 21 days of culture.

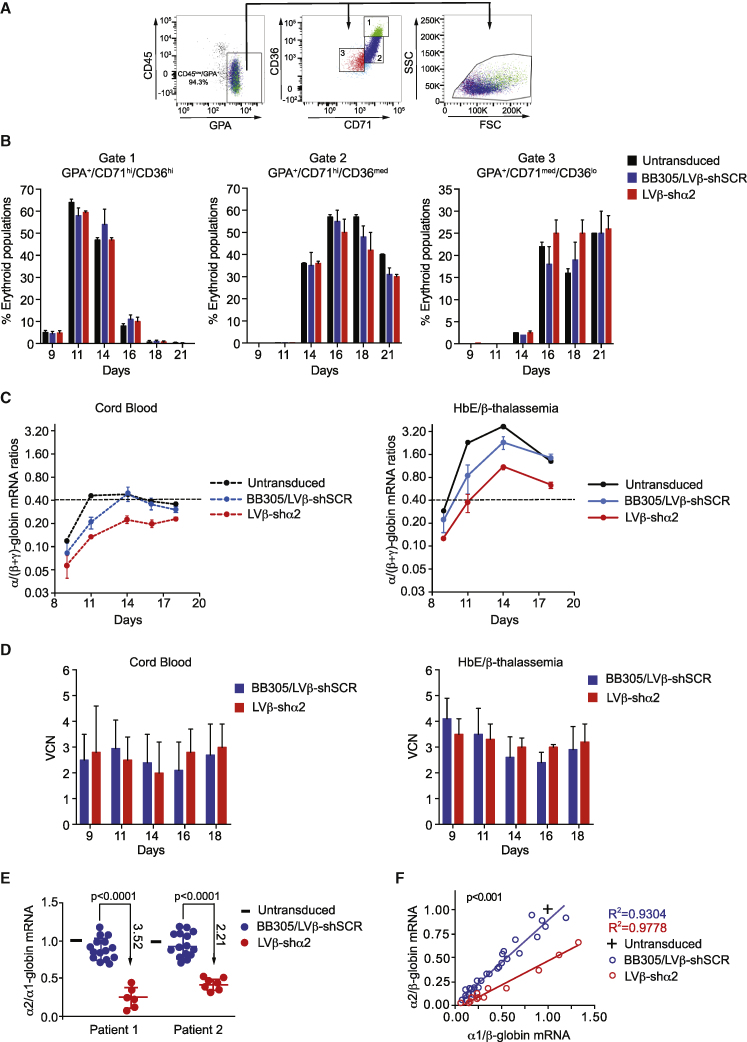

Figure 4.

Analysis of LVβ-shα2-mediated knockdown of α2-globin in primary erythroid cells

(A) Erythroid differentiation profile of cells from P1 grown in medium 1 after transduction with BB305, LVβ-shSCR, or LVβ-shα2 at equivalent MOIs. (B) Mean percentages of populations 1 (CD71hi/CD36hi), 2 (CD71hi/CD36med), and 3 (CD71med/CD36lo) in GPA+ cells. (C) Analysis of α/(β+γ)-globin mRNA ratios in CB and P1 cells transduced with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shα2 vectors. Results from BB305 and LVβ-shSCR were pooled. (D) VCNs in the samples analyzed in (C). Data are presented as mean +/- SD of three replicates (E) Analysis of α2/α1-globin mRNA ratios in cells from 2 individuals with HbE/β-thalassemia (P1 and P2). For each analyzed sample, ratios were normalized to those measured at the same time point in non-transduced cells. (F) Correlation between α2/β-globin and α1/β-globin mRNA ratios in erythroid cells of P1 (days 11, 14, and 16) and P2 (days 11, 15, 18, and 21).

We next measured the mRNA ratios of α/(β-like)-globins (i.e., α/(βE+βA-T87Q+γA+γG) in erythroid cells obtained by culture of CD34+ cells from CB of a normal individual and from bone marrow of an individual with HbE/β-thalassemia following transduction with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, or LVβ-shα2 vector (Figure 4C). The γ-globin mRNAs were quantified only when CB cells were included in the comparison. As expected, the α/(β like)-globin mRNA ratios in the absence of vector transduction were higher in HbE/β-thalassemia cells than in normal CB cells (Figure S7A) because of the β-thalassemia phenotype. Either of the control vectors (BB305 or LVβ-shSCR) led to partial normalization of the α/(β-like)-globin mRNA ratios because of expression of βA-T87Q-globin gene (Figures S7B and S7C). Furthermore, when α/(β-like)-globin mRNA ratios were gathered at different time points during erythroid differentiation culture, normalized to ratios in non-transduced cells, and plotted for comparison between BB305 and LVβ-shSCR, no difference was observed (Figures S7B and S7C), indicating that the miR30-shRNA expression cassette does not interfere with vector-derived or endogenous β-like-globin expression levels. This allowed us to pool data collected for BB305 and LVβ-shSCR-transduced cells to form a single control group for statistical comparison with data obtained with LVβ-shα2-transduced cells (Figure 4C). Most significantly, LVβ-shα2 reduced α/(β-like)-globin mRNA ratios in adult HbE/β-thalassemia erythroid cells to levels seen with normal CB cells (Figure 4C), whereas BB305- and LVβ-shSCR-transduced cells had less of an effect on α/(β like)-globin mRNA ratios, particularly during the final stages of erythroid differentiation (day 18). Importantly, these results were obtained at similar VCNs (Figure 4D). We then set out to quantify differences between vector groups in the erythroid cell population of transduced and cultured CD34+ marrow cells from 2 adults with HbE/β-thalassemia (P1 and P2). The (α/β like)-globin mRNA ratios decreased by 2.34- and 1.25- fold with LVβ-shα2 versus the control BB305/LVβ-shSCR group at mean VCN levels of approximatively 3 and 0.75 for P1 and P2, respectively (Figure S8). Importantly the vector encoded βA-T87Q-globin chain was detected at similar levels with all three vectors (Figure S9), supporting the conclusion that variation of the α/ββ ratio is solely due to α-globin mRNA reduction in cells transduced with the LVβ-shα2 vector.

With regard to differences between the 2 α-globin species, the mean α2/α1-globin mRNA ratio after BB305/LVβ-shSCR transduction was equivalent to that measured in non-transduced cells. In contrast, α2/α1-globin mRNA ratios were 3.52- and 2.21-fold lower with LVβ-shα2 than with the control vectors in P1 and P2, respectively (Figure 4E). We then plotted α2/β-globin mRNA ratios relative to α1/β-globin mRNA ratios in the various groups (Figure 4F; Figure S8). As expected, the regression line obtained after transduction with the control vectors BB305/LVβ-shSCR fit the data points for untransduced cells. The slope of the regression line for LVβ-shα2-transduced cells was significantly lower than the slope for the control vectors (p < 0.001), indicating that the decreased α2/α1-globin mRNA ratio is caused by a decrease in α2-globin mRNA levels and not by an increase in α1-globin mRNA levels.

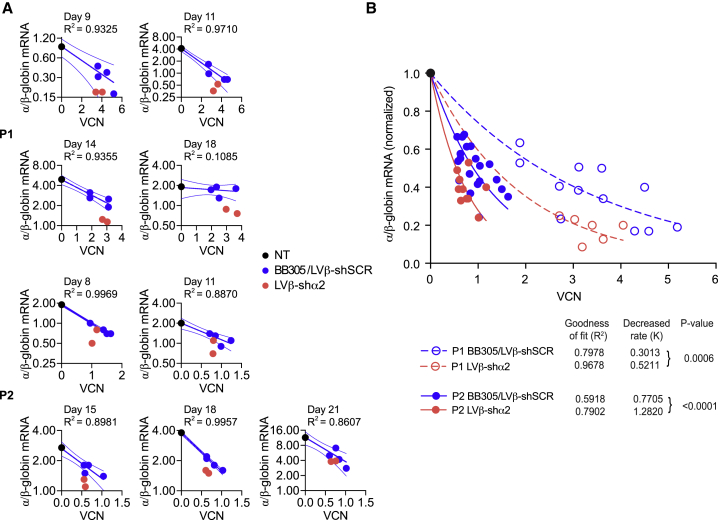

LVβ-shα2 improves (α/β)-globin mRNA ratios at lower VCNs compared with BB305

We next measured (α/β-like)-globin mRNA ratios relative to VCN in P1 and P2 after transduction with the different vectors (Figure 5A). CD34+ cells were transduced at different MOIs (Figure S6). The α/(β-like)-globin mRNA ratios in BB305- and LVβ-shSCR-transduced cells were inversely correlated to the VCNs (Figures S7B and S7C), and these mRNA ratios (y axis) as a function of VCN values (x axis) best fit an “exponential decay model” (Figure S10). No significant difference was observed between the decay rate constants K for BB305 and LVβ-shSCR, indicating that β-globin transgene expression levels were equivalent within this control vector group. In contrast, transduction of HbE/β-thalassemia cells with the LVβ-shα2 vector decreased α/β-globin mRNA ratios to a greater degree than with the vector control group for a given VCN value (Figure 5B), yielding differential values for K. The mean VCNs were 2.8 and 3.1 for BB305/LVβ-shSCR- and LVβ-shα2-transduced P1 cells, respectively, and 0.81 and 0.66 for BB305/LVβ-shSCR- and LVβ-shα2-transduced P2 cells, respectively (Figure S8). According to the model, the relative fold decreases in α/(β-like) ratios with the LVβ-shα2 vector compared with the control vector group, calculated from the best fit curves, were 2.16 (e(3.1 × 0.5211)–(2.8 × 0.3013)) and 1.25 (e(0.66 × 1.282)–(0.81 × 0.7705)) in samples from P1 and P2, respectively (Figure 5B). These calculated values were comparable with the actual measures of 2.34 and 1.25 for P1 and P2, respectively (Figure S8), suggesting that the model fits the data well. The model takes into account all relevant parameters, which include α-globin mRNA fold reduction by the shRNAs, increased β-like-globin mRNA production because of vector-derived βA-T87Q-globin expression, and VCN levels.

Figure 5.

Analysis of α/β-globin ratio to VCN in transduced primary HbE/β-thalassemia erythroid cells

(A) α/β-globin mRNA ratio in transduced primary cells from two individuals (P1 and P2) with HbE/β-thalassemia. Cells were transduced at MOI 5 and 10 (P1) or 1 and 3 (P2) and grown for 3 weeks in medium 1 (P1) or medium 2 (P2). (B) Curve fitting to normalized data, 95% confidence intervals, and significance of differences between decay rates (K) calculated from data obtained in BB305/LVβ-shSCR- and LVβ-shα2-transduced cells. Results from day 18 in (A) were not included to construct the best fit curve because the data did not follow the shared model. Determination of p values for comparison of decreased rates in samples transduced with the BB305/LVβ-shSCR and LVβ-shα2 vectors was performed, assuming ratios of 1 in unmodified cells and 0 at infinite VCN.

An important corollary to the model is that one can derive the “gain” in VCN values between the LVβ-shα2 vector and the control vector group to achieve the same degree of normalization (decrease) of the (α/β-like)-globin mRNA ratios, establishing the differential potency of the various vectors. This is obtained by simply calculating the ratio of the K decay rate constants for each of the two groups, and the factor so derived is 1.7. Importantly, this determination is independent of VCN levels. In other words, 1.7-fold fewer integrated vector copies of the LVβ-shα2 vector than the parent vector BB305 are sufficient to achieve the same degree of (α/β-like)-globin mRNA ratio improvement.

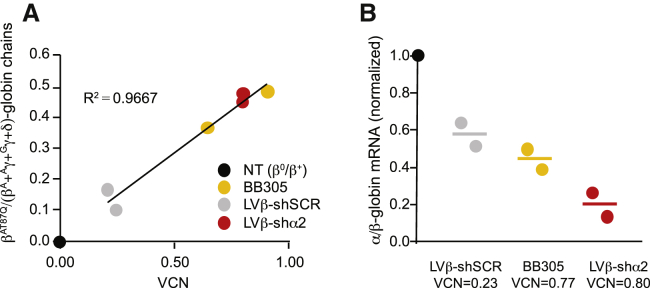

To further validate the LVβ-shα2 vector, we investigated a third individual with β°/β+-thalassemia (P3) with a particularly severe compound heterozygous genotype (IVS2-654C > T and −28A > G). We also made use of pooled erythroid colonies grown in methylcellulose instead of liquid cultures, used previously for P1 and P2, to diversify the experimental approach. CD34+ cells were transduced at a low MOI to maximize the number of cells with a single integration event. After transduction (n = 2), cells were grown in methylcellulose for 2 weeks and analyzed by qPCR for VCN determination and concurrent globin mRNA assays by qRT-PCR. The mean population VCNs were 0.23, 0.77, and 0.80 for LVβ-shSCR-, BB305-, and LVβ-shα2-transduced cells, respectively (Figure 6A). Again, the LVβ-shα2 vector showed a greater potency to decrease α/β-globin mRNA ratios than BB305 at low VCNs (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Analysis of α/β-globin ratios in transduced primary β°/β+-thalassemia erythroid cells

CD34+ cells from a transfusion-dependent individual with β°/β+-thalassemia were transduced (n = 2) with the BB305, LVβ-shSCR, and LVβ-shα2 vectors at low MOI, grown in methylcellulose for 2 weeks, and analyzed by qPCR, qRT-PCR, and HPLC for VCN determination and globin gene expression. (A) Correlation of the βT87Q-globin chain fraction relative to VCN. (B) α/β-mRNA ratios relative to UT cells.

Discussion

In this study, we report an innovative gene therapy strategy and vector to improve the clinical efficacy and safety of current lentiviral gene therapy for individuals with β-thalassemia. The gene therapy vector derived from BB305 comprises the therapeutic anti-sickling βA-T87Q-globin gene configured with an intronic miR30-shRNA tailored to quantitatively reduce α-globin chain synthesis and correct the α:β-globin chain imbalance. LVβ-shα2 was designed to specifically target human α2-globin mRNA without affecting human α1-globin mRNA. This ensures that there will be no risk of inducing clinically meaningful α-thalassemia.

Our results demonstrate that LVβ-shα2 vector titers and transduction efficiency in primary human hematopoietic CD34+ cells are equivalent to the parent BB305 gene therapy vector. LVβ-shα2 retains vector-encoded βA-T87Q-globin expression profiles similar to BB305 in erythroid cell lines and erythroid progeny of transduced normal and β-thalassemia CD34+ cells. The reduction in α2-globin mRNA levels, in concert with vector-encoded βA-T87Q-globin expression, improved α:β-globin ratios in β-thalassemia erythroid cells to the same degree at VCN levels 1.7-fold lower than those of the parent vector BB305. Importantly, α1-globin mRNA levels are unaffected.

Although BB305 has proven highly effective and reliable for successful treatment of β+-thalassemia (e.g., HbE/β0-thalassemia), it has faced more challenges for individuals with a β0/β0 genotype because of the very large amount of therapeutic protein that needs to be produced in vivo in this population.10,11 Preliminary data from a recent clinical trial of BB305 that focuses on individuals with β0/β0-thalassemia (HGB-212) indicate that higher levels of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transduction were able to increase Hb levels to 13.2 g/dL in one individual and to 10.4 g/dL, respectively, in two individuals with the β0/β0 genotype after 12 months of follow-up.10,27 Although these clinical data are encouraging, there is room for further improvement in this challenging population. Although continuous optimization in transduction conditions may play a major role in increasing clinical efficacy, further augmenting VCN values in hematopoietic cells raises the concern of an increased risk of oncogenicity by insertional mutagenesis.27,28

Previous efforts to increase β-globin gene synthesis explored the use of larger DNase hypersensitive site (HS) fragments or adding the LCR HS 1 (HS1) element in LVβ gene therapy vectors, and this provided only modest improvements.29,30 The use of chromatin insulators, such as the chicken β-globin locus 5′ HS4 element, has also been explored to prevent the repressive influences of surrounding chromatin on the integrated vector and reduce possible cis-acting effects of the LCR enhancers on neighboring genes.31,32 However, these elements were associated with reduced transduction efficiency and genetic instability.33,34

Clinical evidence indicates that moderate reduction of α-globin chains via co-inheritance of the α-thalassemia trait decreases the severity of β-thalassemia.19,35 Decreasing the levels of unpaired α-globin has been proposed on a theoretical basis as a complementary approach for treatment of β-thalassemia.18,36, 37, 38 Our previous investigations demonstrated phenotypic improvement of primary erythroid cells derived from β-thalassemic mice (Hbbth3/+) when treated with α-globin-specific siRNA.21 However, lifelong delivery of siRNAs are a major limitation for the utility of therapeutic siRNAs for β-hemoglobinopathies. Approaches based on transduction of HSCs with LV vectors harboring shRNAs are an effective delivery strategy for clinical translation of RNAi-based therapies. Such a strategy was used to deliver a sickle (βS)-globin-specific shRNA embedded in intron 2 of the γ-globin gene because a moderate decrease in βS-globin expression may substantially improve sickle cell disease and abrogate the need for high-level expression of the vector-encoded globin gene.39

More recently, by extending the design principles of microRNAs (miRNAs), an optimized BCL11A-shRNA embedded in a miRNA was used to achieve ubiquitous knockdown of BCL11A and promote production of HbF in erythroid cells.40,41 Utilizing the erythroid-specific β-globin LCR to drive expression of a miRNA-containing BCL11A-specific shRNA and minimize potential off-target side effects averted negative effects on HSC engraftment.42, 43, 44 Similarly, LV vectors encoding erythroid-specific shRNA were designed to target the aberrant mRNA in βIVS1-110-thalassemia because it may potentially interfere with HBB expression.45 These findings signify the importance of lineage-specific gene silencing because it can be used as a flexible tool for analysis of gene function and development of gene-specific therapeutic agents.

The strategy to combine β-globin gene addition with reduction of α-globin chains has been evidenced previously using foamy virus vector-expressing β-globin regulated by the HS40 element derived from the α-globin locus and polymerase III (Pol III)-directed, α-globin-specific shRNA.46 This vector has been reported to restore globin chain balance in β0-thalassemic erythroid cells. However, lack of proper control and the deleterious effect of Pol III-directed shRNA limits its use.46 An alternative approach to reduce α-globin expression, focused on disrupting the core α-globin gene enhancer MCS-R2 (HS-40) in primary human HSCs using genome editing technology.47 This strategy was used to emulate a natural α-thalassemia mutation and reduce α-globin expression to levels beneficial for individuals with β-thalassemia. In cells with HbE/β-thalassemia mutations, targeted deletion of MCS-R2 ameliorated the α/β-globin chain ratio to beneficial levels without perturbing erythroid differentiation or having detectable off-target events. If genome editing of MCS-R2 is to become a realistic therapeutic approach for β-thalassemia, then such an approach will be generally applicable to non-β0/β0-genotype individuals in whom the endogenous output of β-globin is relatively high.

Even in individuals with β-thalassemia with non-β0/β0 genotypes, where BB305 has proven so effective, further increase in safety could be obtained by using a vector that can achieve a similar degree of therapeutic efficacy while minimizing the number of chromosomal integration events. This would be especially valuable for individuals with a possible increased predisposition to hematologic malignancies, as in those with sickle cell disease.48,49 Because optimal therapeutic benefits are likely to require a vector capable of completely restoring equimolar expression of α- and β-globin, the LVβ-shα2 gene therapy vector may afford an improved benefit/risk ratio for all individuals with β-thalassemia regardless of genotype. Clinical trials of LVβ-shα2, anticipated to be initiated shortly, should provide answers regarding the safety and efficacy of this approach for gene therapy of β-thalassemia.

Materials and methods

Lentiviral vector design, production, titration, and characterization in human cell lines

The LentiGlobin BB305 gene therapy vector has been described previously.50 It is a self-inactivating (SIN), Tat-independent vector that contains a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and enhancer instead of the HIV U3 region at the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) and a deleted 3′ U3 region and encodes the altered adult βA-T87Q-globin gene (Figure 1).51 The βA-T87Q-globin gene in the BB305 gene therapy vector features a 374-bp purine-rich deletion in IVS2, located between +580 and +953 of HBB (“GenBank: MG657341”), identified previously to increase viral titers.52 The IVS2 breakpoint site was used to insert the miR30-shRNA expression cassette flanked by approximately 125 bases 5′ and 3′ of the miR30 sequence to ensure β-globin-coupled shRNA expression in erythroid cells. This design mimics natural intronic miRNAs in protein-coding genes, which provide expression of the miRNAs and the protein-coding gene from a single transcript.53 The miR30-shRNA expression cassette was selected for its well-characterized loop/bulge structure and accurate processing of shRNA/pre-miRNA ends.54,55

A description of the cloning procedures is provided in Figure S1. Briefly, the miR30-shRNA cassette was amplified from the MSCV/LTRmiR30-PIGΔRI (LMP) vector.56 Two partially complementary oligonucleotides (5′BP-miR30 and 3′BP-miR30; Table S1) with a 40-bp homologous sequence immediately flanking the deletion breakpoint of the β-globin intron 2 region was used to amplify the miR30-shRNA expression cassette. The resultant fragment was then used as the downstream megaprimer for the overlap extension PCR cloning strategy to insert the miR30-shRNA expression cassette into the β-globin IVS2 breakpoint site, which contained part of β-globin exon 2, intron 2, exon 3, and 3′ enhancer region cloned into the BamHI site of pBluescript II KS (+).57 β-Globin intron 2 containing the miR30-shRNA cassette was then cloned into pBB305, replacing the existing BamHI fragment, and verified by sequencing. Using this approach, LVβ-shRNA viral vector derivatives were created by incorporating shRNA sequences targeting EGFP (LVβ-shGFP) and the negative control vector containing a scrambled shRNA sequence (LVβ-shSCR) (Table S2). Oligonucleotides and primers used for cloning are listed in Table S1.

Lentiviral particles were produced by co-transfecting the lentiviral transfer vector with a packaging plasmid system as described previously.58 The lentiviral titer was determined by transducing NIH/3T3 cells.59 Lentiviral particles were evaluated in the MEL-βEGFP, K562, and HUDEP-2 cell lines as described previously.22 The downregulation efficiency of EGFP expression was determined by measuring the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) by flow cytometry. Transduced K562 cells were incubated with hemin to induce erythroid differentiation. Human βA-T87Q-globin expression was determined by intracellular antibody staining. β0-HUDEP-2 cells, containing biallelic β0-globin mutations, were created using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Details can be found in the Supplemental materials and methods.

Human CD34+ transduction and culture

Human CD34+ cells were cultured in StemPro34 SFM (serum free medium, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with the human cytokines fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (hFlt3L), Stem Cell Factor (hSCF), and interleukin-3 (hIL-3) (at 50, 50, and 10 ng/mL, respectively; all from Miltenyi Biotech) in the presence of 20% serum substitute (BIT 9500, STEMCELL Technologies). After 7 days, erythropoietin (EPO) at 3 IU/mL was used to replace FLt3L, SCF, and IL-3 (medium 1). Alternatively, CD34+ cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dubelcco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with SCF (100 ng/mL), IL-3 (5 ng/mL), and EPO (3 U/mL) from day 0, supplemented with SCF and EPO from day 8, and with EPO only from day 11 (medium 2). When indicated, CD34+ cells were transduced 24 h after the beginning of culture in medium containing protamine sulfate (8 μg/mL) at MOIs between 2 and 10.

VCN determination

Genomic DNA from CD34+-derived cells was prepared from liquid culture or pooled colonies using the NucleoSpin Blood Kit (Macherey Nagel). VCNs per cell were determined by the delta-delta-Ct method (ΔΔCt) method as described previously.60 Primers and probes used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) are listed in Table S3.

RNA preparation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent solution or PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) or EuroScript Reverse Transcriptase Core Kit (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Gene expression was quantified by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR), performed with gene-specific primers and probes (Table S4) and 2X qPCR Master Mix (Eurogentec) using the 7300 ABI Prism detection system. Relative expression of target genes was quantified based on the efficiency-corrected calculation method.61 For analysis of shRNA expression, first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using specific stem-loop RT primers and subsequently analyzed by qPCR.62,63 For relative quantification of α-globin versus β-globin and γ-globin gene expression, the recombinant DNA plasmid pT7-αβγ containing HBA, HBB, and HBG cDNAs in tandem was used to generate standard curves.64

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad). A p value of less than 0.05, generated by a Student’s t test, was considered statistically significant. The decreased rates of α/β-globin mRNA ratios and differences between groups using the exponential decay equation model (Supplemental materials and methods) were determined using GraphPad Prism 6.0.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ryo Kurita and Yukio Nakamura for providing the HUDEP-2 cell line. We also acknowledge Monash Pathology for assistance with HPLC and hemoglobin variant analysis of HUDEP-2 cells and the Fondation Générale de Santé (FGDS) and the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP) for collecting and testing cord blood cells. This work was supported by the European Research Projects on Rare Diseases (GETHERTHAL); the European Commission; the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia (Project Grant APP1147867); the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program; the Thalassaemia and Sickle Cell Society of Australia, the Thalassaemia Society of New South Wales; The Greek Conference; the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT); the Thai Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation (B05F630062); and Mahidol University (MRC-MGR 01/2563).

Author contributions

T.N., K.S.-F., M.G., B.M., E.P., P.L., and J.V. designed the experiments. T.N., K.S.-F., M.G., B.M., J.G., A.G., H.P.J.V., and H.Y.T. performed experiments. T.N., K.S.-F., M.G., B.M., J.G., A.G., H.P.J.V., H.Y.T., and E.P. analyzed data. G.G., S.S., S.F., and S.H. provided samples and resources. T.N., P.L., E.P., and J.V. wrote the manuscript. P.L., E.P., and J.V. conceptualized the idea and supervised the project.

Declaration of interests

P.L. is a scientific founder and shareholder of bluebird bio, Inc. He is an inventor of awarded patents that cover the βA-T87Q-globin gene and the BB305 LentiGlobin vector.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.037.

Contributor Information

Philippe Leboulch, Email: pleboulch@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

Emmanuel Payen, Email: emmanuel.payen@cea.fr.

Jim Vadolas, Email: jim.vadolas@hudson.org.au.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Higgs D.R., Engel J.D., Stamatoyannopoulos G. Thalassaemia. Lancet. 2012;379:373–383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weatherall D.J., Clegg J.B. Inherited haemoglobin disorders: an increasing global health problem. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001;79:704–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voon H.P., Vadolas J. Controlling alpha-globin: a review of alpha-globin expression and its impact on beta-thalassemia. Haematologica. 2008;93:1868–1876. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosveld F., van Assendelft G.B., Greaves D.R., Kollias G. Position-independent, high-level expression of the human beta-globin gene in transgenic mice. Cell. 1987;51:975–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90584-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magrin E., Miccio A., Cavazzana M. Lentiviral and genome-editing strategies for the treatment of β-hemoglobinopathies. Blood. 2019;134:1203–1213. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sii-Felice K., Negre O., Brendel C., Tubsuwan A., Morel-À-l’Huissier E., Filardo C., Payen E. Innovative Therapies for Hemoglobin Disorders. BioDrugs. 2020;34:625–647. doi: 10.1007/s40259-020-00439-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imren S., Payen E., Westerman K.A., Pawliuk R., Fabry M.E., Eaves C.J., Cavilla B., Wadsworth L.D., Beuzard Y., Bouhassira E.E. Permanent and panerythroid correction of murine beta thalassemia by multiple lentiviral integration in hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14380–14385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212507099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawliuk R., Westerman K.A., Fabry M.E., Payen E., Tighe R., Bouhassira E.E., Acharya S.A., Ellis J., London I.M., Eaves C.J. Correction of sickle cell disease in transgenic mouse models by gene therapy. Science. 2001;294:2368–2371. doi: 10.1126/science.1065806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwiatkowski J.L., Thompson A.A., Rasko J.E.J., Hongeng S., Schiller G.J., Anurathapan U. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Lentiglobin Gene Therapy for Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia in the Northstar (HGB-204) Study. Blood. 2019;134:4628. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lal A., Locatelli F., Kwiatkowski J.L., Kulozik A.E., Yannaki E., Porter J.B. Northstar-3: Interim Results from a Phase 3 Study Evaluating Lentiglobin Gene Therapy in Patients with Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia and Either a β0 or IVS-I-110 Mutation at Both Alleles of the HBB Gene. Blood. 2019;134:815. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson A.A., Walters M.C., Kwiatkowski J., Rasko J.E.J., Ribeil J.A., Hongeng S., Magrin E., Schiller G.J., Payen E., Semeraro M. Gene Therapy in Patients with Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1479–1493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson A.A., Walters M.C., Kwiatkowski J.L., Hongeng S., Porter J.B., Sauer M.G. Northstar-2: Updated Safety and Efficacy Analysis of Lentiglobin Gene Therapy in Patients with Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia and Non-β0/β0 Genotypes. Blood. 2019;134:3543. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magrin E., Semeraro M., Magnani A., Puy H., Miccio A., Hebert N. Results from the Completed Hgb-205 Trial of Lentiglobin for β-Thalassemia and Lentiglobin for Sickle Cell Disease Gene Therapy. Blood. 2019;134:3358. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeil J.A., Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Payen E., Magnani A., Semeraro M., Magrin E., Caccavelli L., Neven B., Bourget P., El Nemer W. Gene Therapy in a Patient with Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:848–855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison C. First gene therapy for β-thalassemia approved. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:1102–1103. doi: 10.1038/d41587-019-00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thalassaemia International Federation . 2020. Clinical trial updates: ZYNTEGLO (ex-Lentiglobin) for patients with TDT.https://thalassaemia.org.cy/publications/clinical-trial-updates/gene-therapy/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marktel S., Scaramuzza S., Cicalese M.P., Giglio F., Galimberti S., Lidonnici M.R., Calbi V., Assanelli A., Bernardo M.E., Rossi C. Intrabone hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for adult and pediatric patients affected by transfusion-dependent ß-thalassemia. Nat. Med. 2019;25:234–241. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mettananda S., Gibbons R.J., Higgs D.R. α-Globin as a molecular target in the treatment of β-thalassemia. Blood. 2015;125:3694–3701. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-633594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sripichai O., Munkongdee T., Kumkhaek C., Svasti S., Winichagoon P., Fucharoen S. Coinheritance of the different copy numbers of alpha-globin gene modifies severity of beta-thalassemia/Hb E disease. Ann. Hematol. 2008;87:375–379. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thein S.L. Genetic modifiers of the beta-haemoglobinopathies. Br. J. Haematol. 2008;141:357–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voon H.P., Wardan H., Vadolas J. siRNA-mediated reduction of alpha-globin results in phenotypic improvements in beta-thalassemic cells. Haematologica. 2008;93:1238–1242. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan K.S., Xu J., Wardan H., McColl B., Orkin S., Vadolas J. Generation of a genomic reporter assay system for analysis of γ- and β-globin gene regulation. FASEB J. 2012;26:1736–1744. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-199356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McColl B., Kao B.R., Lourthai P., Chan K., Wardan H., Roosjen M., Delagneau O., Gearing L.J., Blewitt M.E., Svasti S. An in vivo model for analysis of developmental erythropoiesis and globin gene regulation. FASEB J. 2014;28:2306–2317. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-246637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurita R., Suda N., Sudo K., Miharada K., Hiroyama T., Miyoshi H., Tani K., Nakamura Y. Establishment of immortalized human erythroid progenitor cell lines able to produce enucleated red blood cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miccio A., Cesari R., Lotti F., Rossi C., Sanvito F., Ponzoni M., Routledge S.J., Chow C.M., Antoniou M.N., Ferrari G. In vivo selection of genetically modified erythroblastic progenitors leads to long-term correction of beta-thalassemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10547–10552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puthenveetil G., Scholes J., Carbonell D., Qureshi N., Xia P., Zeng L., Li S., Yu Y., Hiti A.L., Yee J.K., Malik P. Successful correction of the human beta-thalassemia major phenotype using a lentiviral vector. Blood. 2004;104:3445–3453. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikawa Y., Miccio A., Magrin E., Kwiatkowski J.L., Rivella S., Cavazzana M. Gene therapy of hemoglobinopathies: progress and future challenges. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019;28(R1):R24–R30. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fehse B., Kustikova O.S., Bubenheim M., Baum C. Pois(s)on--it’s a question of dose. Gene Ther. 2004;11:879–881. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arumugam P.I., Scholes J., Perelman N., Xia P., Yee J.K., Malik P. Improved human beta-globin expression from self-inactivating lentiviral vectors carrying the chicken hypersensitive site-4 (cHS4) insulator element. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:1863–1871. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lisowski L., Sadelain M. Locus control region elements HS1 and HS4 enhance the therapeutic efficacy of globin gene transfer in beta-thalassemic mice. Blood. 2007;110:4175–4178. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramezani A., Hawley T.S., Hawley R.G. Combinatorial incorporation of enhancer-blocking components of the chicken beta-globin 5'HS4 and human T-cell receptor alpha/delta BEAD-1 insulators in self-inactivating retroviral vectors reduces their genotoxic potential. Stem Cells. 2008;26:3257–3266. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romero Z., Urbinati F., Geiger S., Cooper A.R., Wherley J., Kaufman M.L., Hollis R.P., de Assin R.R., Senadheera S., Sahagian A. β-globin gene transfer to human bone marrow for sickle cell disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3317–3330. doi: 10.1172/JCI67930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronen K., Negre O., Roth S., Colomb C., Malani N., Denaro M., Brady T., Fusil F., Gillet-Legrand B., Hehir K. Distribution of lentiviral vector integration sites in mice following therapeutic gene transfer to treat β-thalassemia. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:1273–1286. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urbinati F., Arumugam P., Higashimoto T., Perumbeti A., Mitts K., Xia P., Malik P. Mechanism of reduction in titers from lentivirus vectors carrying large inserts in the 3'LTR. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1527–1536. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wainscoat J.S., Thein S.L., Weatherall D.J. Thalassaemia intermedia. Blood Rev. 1987;1:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(87)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappellini M.D., Motta I. New therapeutic targets in transfusion-dependent and -independent thalassemia. Hematology (Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program) 2017;2017:278–283. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thein S.L. Molecular basis of β thalassemia and potential therapeutic targets. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2018;70:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voon H.P., Wardan H., Vadolas J. Co-inheritance of alpha- and beta-thalassaemia in mice ameliorates thalassaemic phenotype. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2007;39:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samakoglu S., Lisowski L., Budak-Alpdogan T., Usachenko Y., Acuto S., Di Marzo R., Maggio A., Zhu P., Tisdale J.F., Rivière I., Sadelain M. A genetic strategy to treat sickle cell anemia by coregulating globin transgene expression and RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:89–94. doi: 10.1038/nbt1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guda S., Brendel C., Renella R., Du P., Bauer D.E., Canver M.C., Grenier J.K., Grimson A.W., Kamran S.C., Thornton J. miRNA-embedded shRNAs for Lineage-specific BCL11A Knockdown and Hemoglobin F Induction. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:1465–1474. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilber A., Hargrove P.W., Kim Y.S., Riberdy J.M., Sankaran V.G., Papanikolaou E., Georgomanoli M., Anagnou N.P., Orkin S.H., Nienhuis A.W., Persons D.A. Therapeutic levels of fetal hemoglobin in erythroid progeny of β-thalassemic CD34+ cells after lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer. Blood. 2011;117:2817–2826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brendel C., Guda S., Renella R., Bauer D.E., Canver M.C., Kim Y.J., Heeney M.M., Klatt D., Fogel J., Milsom M.D. Lineage-specific BCL11A knockdown circumvents toxicities and reverses sickle phenotype. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:3868–3878. doi: 10.1172/JCI87885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brendel C., Negre O., Rothe M., Guda S., Parsons G., Harris C., McGuinness M., Abriss D., Tsytsykova A., Klatt D. Preclinical Evaluation of a Novel Lentiviral Vector Driving Lineage-Specific BCL11A Knockdown for Sickle Cell Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020;17:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esrick E.B., Achebe M., Armant M., Bartolucci P., Ciuculescu M.F., Daley H. Validation of BCL11A As Therapeutic Target in Sickle Cell Disease: Results from the Adult Cohort of a Pilot/Feasibility Gene Therapy Trial Inducing Sustained Expression of Fetal Hemoglobin Using Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing. Blood. 2019;134:LBA-5. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patsali P., Papasavva P., Stephanou C., Christou S., Sitarou M., Antoniou M.N., Lederer C.W., Kleanthous M. Short-hairpin RNA against aberrant HBBIVSI-110(G>A) mRNA restores β-globin levels in a novel cell model and acts as mono- and combination therapy for β-thalassemia in primary hematopoietic stem cells. Haematologica. 2018;103:e419–e423. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.189357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papadaki M., Vassilopoulos G. Decrease of alpha-chains in beta-thalassemia. Thalassemia Reports. 2013;3:e40. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mettananda S., Fisher C.A., Hay D., Badat M., Quek L., Clark K., Hublitz P., Downes D., Kerry J., Gosden M. Editing an α-globin enhancer in primary human hematopoietic stem cells as a treatment for β-thalassemia. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:424. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00479-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunson A., Keegan T.H.M., Bang H., Mahajan A., Paulukonis S., Wun T. Increased risk of leukemia among sickle cell disease patients in California. Blood. 2017;130:1597–1599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-783233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaiser J. Gene therapy trials for sickle cell disease halted after two patients develop cancer. ScienceMag. 2021 https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/02/gene-therapy-trials-sickle-cell-disease-halted-after-two-patients-develop-cancer February 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Negre O., Bartholomae C., Beuzard Y., Cavazzana M., Christiansen L., Courne C., Deichmann A., Denaro M., de Dreuzy E., Finer M. Preclinical evaluation of efficacy and safety of an improved lentiviral vector for the treatment of β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Curr. Gene Ther. 2015;15:64–81. doi: 10.2174/1566523214666141127095336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Negre O., Eggimann A.V., Beuzard Y., Ribeil J.A., Bourget P., Borwornpinyo S., Hongeng S., Hacein-Bey S., Cavazzana M., Leboulch P., Payen E. Gene Therapy of the β-Hemoglobinopathies by Lentiviral Transfer of the β(A(T87Q))-Globin Gene. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:148–165. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leboulch P., Huang G.M., Humphries R.K., Oh Y.H., Eaves C.J., Tuan D.Y., London I.M. Mutagenesis of retroviral vectors transducing human beta-globin gene and beta-globin locus control region derivatives results in stable transmission of an active transcriptional structure. EMBO J. 1994;13:3065–3076. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Du G., Yonekubo J., Zeng Y., Osisami M., Frohman M.A. Design of expression vectors for RNA interference based on miRNAs and RNA splicing. FEBS J. 2006;273:5421–5427. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gu S., Jin L., Zhang Y., Huang Y., Zhang F., Valdmanis P.N., Kay M.A. The loop position of shRNAs and pre-miRNAs is critical for the accuracy of dicer processing in vivo. Cell. 2012;151:900–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stegmeier F., Hu G., Rickles R.J., Hannon G.J., Elledge S.J. A lentiviral microRNA-based system for single-copy polymerase II-regulated RNA interference in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13212–13217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickins R.A., Hemann M.T., Zilfou J.T., Simpson D.R., Ibarra I., Hannon G.J., Lowe S.W. Probing tumor phenotypes using stable and regulated synthetic microRNA precursors. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1289–1295. doi: 10.1038/ng1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bryksin A.V., Matsumura I. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotechniques. 2010;48:463–465. doi: 10.2144/000113418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sii-Felice K., Castillo Padilla J., Relouzat F., Cheuzeville J., Tantawet S., Maouche L., Le Grand R., Leboulch P., Payen E. Enhanced Transduction of Macaca fascicularis Hematopoietic Cells with Chimeric Lentiviral Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2019;30:1306–1323. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Payen E., Colomb C., Negre O., Beuzard Y., Hehir K., Leboulch P. Lentivirus vectors in β-thalassemia. Methods Enzymol. 2012;507:109–124. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386509-0.00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Negre O., Fusil F., Colomb C., Roth S., Gillet-Legrand B., Henri A., Beuzard Y., Bushman F., Leboulch P., Payen E. Correction of murine β-thalassemia after minimal lentiviral gene transfer and homeostatic in vivo erythroid expansion. Blood. 2011;117:5321–5331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmittgen T.D., Lee E.J., Jiang J., Sarkar A., Yang L., Elton T.S., Chen C. Real-time PCR quantification of precursor and mature microRNA. Methods. 2008;44:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C., Ridzon D.A., Broomer A.J., Zhou Z., Lee D.H., Nguyen J.T., Barbisin M., Xu N.L., Mahuvakar V.R., Andersen M.R. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tubsuwan A., Munkongdee T., Jearawiriyapaisarn N., Boonchoy C., Winichagoon P., Fucharoen S., Svasti S. Molecular analysis of globin gene expression in different thalassaemia disorders: individual variation of β(E) pre-mRNA splicing determine disease severity. Br. J. Haematol. 2011;154:635–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.