Abstract

Over the ages, fungi have associated with different parts of the human body and established symbiotic associations with their host. They are mostly commensal unless there are certain not so well-defined factors that trigger the conversion to a pathogenic state. Some of the factors that induce such transition can be dependent on the fungal species, environment, immunological status of the individual, and most importantly host genetics. In this review, we discuss the different aspects of how host genetics play a role in fungal infection since mutations in several genes make hosts susceptible to such infections. We evaluate how mutations modulate the key recognition between the pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMP) and the host pattern recognition receptor (PRR) molecules. We discuss the polymorphisms in the genes of the immune system, the way it contributes toward some common fungal infections, and highlight how the immunological status of the host determines fungal recognition and cross-reactivity of some fungal antigens against human proteins that mimic them. We highlight the importance of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are associated with several of the receptor coding genes and discuss how it affects the signaling cascade post-infection, immune evasion, and autoimmune disorders. As part of personalized medicine, we need the application of next-generation techniques as a feasible option to incorporate an individual’s susceptibility toward invasive fungal infections based on predisposing factors. Finally, we discuss the importance of studying genomic ancestry and reveal how genetic differences between the human race are linked to variation in fungal disease susceptibility.

Keywords: genetic predisposition, disease susceptibility, invasive, fungal infection, host genetics, genetic polymorphism, SNP, human ancestry

Introduction

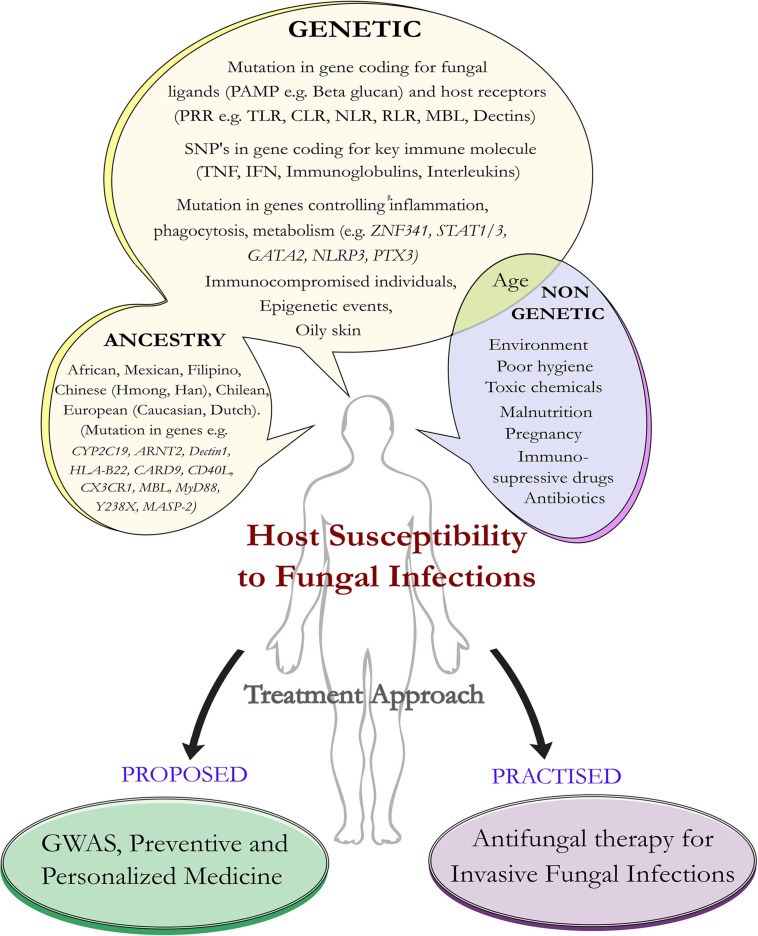

Fungi are eukaryotic organisms that have a tremendous impact on human health. About 5.1 million fungal species are present on the earth (Hawksworth and Rossman, 1997; Blackwell, 2011). They reproduce asexually by sporulation, budding, and fragmentation. Sexual reproduction involves three phases like plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis. In fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth and are collectively called the mycelium. They are usually heterotrophic in nature (Carris et al., 2012) and few are commensal, with the human body acting as a host (Ibrahim and Voelz, 2017). Most of the fungi are adapted to the land environments, and during early episodes of terrestrialization, they had interacted with other organisms having typical parasitic lifestyles (Naranjo-Ortiz and Gabaldón, 2019). Under certain not so well-defined conditions, fungi transform from the non-pathogenic budding yeast to its pathogenic hyphal form, which invades the host tissue (de Pauw, 2011; Underhill and Pearlman, 2015; Kruger et al., 2019; Rai et al., 2021). The fungal species can grow anywhere including plants, animals, and humans. Some enters into our body by inhalation (e.g., Aspergillus) and some are commensal (e.g., Candida, Malassezia) (Underhill and Pearlman, 2015). Commensal like Malassezia is more abundant in sebaceous sites of the host. Since they are lipid dependent, they obtain food sources from the host without harming them and colonization starts immediately after birth, when neonatal sebaceous glands are active (Vijaya Chandra et al., 2021). Studies of the microbiome have emerged to be an important area of research, and more importantly, the spotlight is now to understand less studied fungi that have a tremendous influence on the human microbiome especially among immunocompromised individuals. A dysbiotic microbial population is a general characteristic of any fungal infection affecting the mammalian system (Iliev and Leonardi, 2017). Recent reports point toward the role of fungus in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), a form of human pancreatic cancer caused directly by the presence of budding yeast Malassezia, which colonizes the human gut (Aykut et al., 2019). The severity of fungal infection depends on factors such as inoculum load, magnitude of tissue destruction, ability of the fungus to multiply in the tissue, ability to migrate to nearby organs, microenvironment, and immunogenetic status of the host. Resistance to fungi externally is based on cutaneous and mucosal physical barriers and internally by the body’s immune molecules and the defensins (Aristizabal and González, 2013; Coates et al., 2018; Salazar and Brown, 2018). Immunosuppression and breakdown of anatomical barriers such as the skin are the major factors behind fungal infections (Kobayashi, 1996). In addition to this, malnutrition, poor hygiene, use of antibiotics, genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and host physiological factors (e.g., oily skin) contribute toward disease progression (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Host susceptibility to invasive fungal infection: predisposing factors and treatment approach. Schematic diagram represents predisposition of the host to certain factors that make them susceptible to fungal infections. Such factors can be genetic as well as non-genetic. Apart from genetic mutations in the host ligand, fungal receptors, and immune genes, human ancestry plays an important role in susceptibility toward invasive fungal infections. The future approaches would be geared toward the investigation (as part of preventive medicine) of the genetic mutations that predispose individuals to fungal infections and offer personalized medicine compared to the more traditional approach that is practiced in the form of antifungal medication.

Genetic variations play an important role in fungal infection (Pana et al., 2014; Maskarinec et al., 2016; Duxbury et al., 2019; Table 1). Recent studies have shown the importance of host genetic variation in influencing the severity and susceptibility to invasive fungal infections (IFIs) (Maskarinec et al., 2016). Increased incidence of opportunistic fungal diseases has been implicated due to gene polymorphism, and genetic errors are frequently observed in immunodeficient phenotypes (Pana et al., 2014). Along with genetic and environmental factors, lifestyle also contributes toward the variation in the genome, as the presence of toxic chemicals and immunosuppressive drugs in an organism’s environment leads to altered immune status and inherited deficiencies, which result in susceptibility toward fungal infection (Kumar et al., 2018; Figure 1). At the molecular level, epigenetic events like alteration of DNA methylation (a key feature that controls gene expression) (Martin and Fry, 2018), modification in the histones (involved in altered gene expression) (Dolinoy and Jirtle, 2008), and interaction between microbes, genotypes, and environment play a key role in disease progression (Goodrich et al., 2017). Now, challenge for biologists is to identify genetic components that predispose individuals to fungal infection. The study of genes will help to understand the relationship between genetic polymorphism and the cellular phenotype of host and pathogen (Sardinha et al., 2011). Recent research outcomes aided by genomic sequencing point toward an interesting link between genetic predisposition to fungal infections and human ancestry. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in key immune genes plays an important role in fungal infection affecting particular ancestral populations (Hughes et al., 2008; Dominguez-Andres and Netea, 2019). Thus, with the availability of genetic information, we can study the mechanism behind host defense against the pathogen, susceptibility toward infection (Sardinha et al., 2011), and also have an idea of how the pathogens are evolving and trying to adapt to their host environment through host-pathogen interactions.

TABLE 1.

Genetic mutations, human ancestry, and fungal infections.

| Immune response | Genes | Ancestry link** | Fungal pathogen | Diseases | |

| Innate immunity | Cell mediated | DOCK8, MyD88**, CARD9**, NCF1, TLR1, MPO, CYBB, CYBA, NADPH oxidase | Chinese (Han) African | Candida | Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), candidemia |

| PTX3, NCF1, NCF2, NCF4, DOCK8, TLR4, NADPH oxidase, MPO | Aspergillus | Invasive aspergillosis (IA) | |||

| CARD9, DOCK8 | Malassezia | Pityriasis versicolor | |||

| MBL, MASP-2** | Chinese | Sporothrix | Sporotrichosis | ||

| MBL** | Chinese | Pneumocystis jirovecii | Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) | ||

| Candida | Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) | ||||

| Ferroxidase | Mucorales | Mucormycosis | |||

| HLA-B22** | Mexican | Histoplasma capsulatum | Histoplasmosis | ||

| Humoral | IL-17F, Act1, IL-12RB1, IL-17R, IL-17A, IL-17RA, IL-4, IL-12, TyK2, IL-17RC ZNF341, IL-17, IL-22, Y238X, CLEC7A, IL-10 | Candida, Histoplasma capsulatum | Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC), histoplasmosis, hyper–immunoglobulin E syndrome (HIES) | ||

| Dectin 1**, IL-10 | Chinese (Han) Dutch | Coccidioides immitis | Coccidioidomycosis | ||

| Y238X**, IL-10**, TNFα**, IFN-γ**, CLEC7A, CX3CR1**, ARNT2** Asp299Gly, Thr39lle | European (Dutch, Caucasian) | Aspergillus | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) | ||

| rs2243250(IL-4) | Pneumocystis jirovecii | Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) | |||

| IL-6 | Blastomyces | Blastomycosis | |||

| IL-2 | Histoplasma | Histoplasmosis | |||

| Adaptive immunity | Cell mediated | STAT1 | Histoplasma | Histoplasmosis | |

| Coccidiodes | Coccidioidomycosis | ||||

| STAT1, STAT3, AIRE, GATA2, RORC, CYP2C19**, RAG1, RAG2 | Chinese (Han) Chilean | Candida | Candidiasis | ||

| NOD2, STAT3, CYP2C19** | Chinese (Han) | Aspergillus | Aspergillosis | ||

| CD40L ** CD50, CD80 | Chinese mainland | Pneumocystis jirovecii, Trichophyton | Invasive fungal infection (IFI) | ||

| Humoral | IgG, IgA, IgE, IgM, defect in MHC class II molecule | Pneumocystis jirovecii Candida, Aspergillus, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Paracoccidioides | Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), candidiasis, aspergillosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis. | ||

The symbol ** is used for the genes having the ancestry link.

Genetic Predisposition and Host-Pathogen Interaction

An opportunistic fungus causes diseases mostly in immunocompromised individuals, though normal individuals are also affected (Low and Rotstein, 2011; Eades and Armstrong-James, 2019). Host-pathogen communication initiates through the interactions of the fungal ligands and receptors present on the skin and internal organs (Richmond and Harris, 2014). The better fit of the ligand present on the microbes (against the receptors present on the host), the stronger the interaction (Goyal et al., 2018; Patin et al., 2019). Fungal ligands are a class of evolutionarily conserved structures called the pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and are recognized by receptors present on the host surface called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Post internalization, fungi are primarily recognized by the innate cells (e.g., macrophages and dendritic cells) of the immune system (Mogensen, 2009). The main receptors that recognize the fungal-derived PAMPs are Toll-like receptor (TLR like TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9), C-type lectin receptor (CLR like Dectin1 and Dectin2), Nod-like receptor (NLR), Rig-like receptor (RLR), complement receptor, and mannose binding lectin (MBL) (Akira et al., 2006; van de Veerdonk et al., 2008; Hatinguais et al., 2020). These receptors are a crucial component of fungal recognition and trigger an innate immune response.

The host immune response mainly consists of two types, innate and adaptive immunity (Chaplin, 2010; Aristizabal and González, 2013; Netea et al., 2019). Cell-mediated innate immunity is through antigen-presenting cells (APC), which recognize the fungal antigen and process and present it to the T cells. The T cells that participate in antifungal immunity involve Th (helper T cells) cells, Tc cells (cytotoxic T cells), and Treg (regulatory T cells) cells (Hamad et al., 2018). As soon as the body’s immune cells see the foreign fungus, a chain reaction is initiated. Phagocytosis of the fungal pathogen is mediated by neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells, and the oxidative burst kills fungal pathogen by the activity of NADPH oxidase (Rosales and Uribe-Querol, 2017; Warris and Ballou, 2019). The deficiency of this enzyme disrupts the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and makes an individual more susceptible to fungal infection (Hamad et al., 2018). The non-oxidative killing of the fungal pathogen is enhanced by antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that disrupt the fungal cell wall and also produce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) consisting of calprotectin, which induces antifungal activity (Pathakumari et al., 2020; Ulfig and Leichert, 2021). Calprotectin released from NET is an antimicrobial heterodimer that helps in clearing fungus like Candida, and its deficiency leads to increased fungal burden (Urban et al., 2009). Innate immune response activates adaptive immunity, which is enhanced by both humoral and cell-mediated immune response, aiding in recognizing fungal antigen, generating inflammation, activating the complement cascade, and further leading to opsonization and neutralization of fungal pathogen (Drummond et al., 2014).

Characterization of single gene defects that predispose individuals to fungal infections needs urgent attention. Monogenic causes for susceptibility of invasive fungal infections have unmasked novel molecules and key signaling pathways in defense against mucosal and systemic antifungal threats (Lionakis et al., 2014; Constantine and Lionakis, 2020). Genetic changes in some key genes play a crucial role in host-pathogen recognition (Kumar et al., 2018; Cunha and Carvalho, 2019; Merkhofer and Klein, 2020). Fungal β-glucan (PAMP) activity can be masked through a change in cell wall components and thus prevent target recognition (Plato et al., 2015). A genetic defect in the different types of PRR families makes the host susceptible to fungal infection (Netea et al., 2012). Defect in the CLR Dectin1, encoded by CLEC7A (C-type lectin domain containing 7A) predisposes humans to invasive aspergillosis (IA), chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), and recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) (Reid et al., 2009; Plantinga et al., 2012; Cunha et al., 2018). The CLEC7A intronic SNPs rs3901533 and rs7309123 are associated with susceptibility to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) in patients with hematologic diseases (Taylor et al., 2007; Sainz et al., 2012). Dectin-1 Y238X polymorphism leading to diminished Dectin-1 receptor activity plays a role in RVVC and IA (Plantinga et al., 2009; Cunha et al., 2010; Zahedi et al., 2016). Dectin-1 gene variant also contributes susceptibility to coccidioidomycosis (del Pilar Jiménez-A et al., 2008). Another receptor MBL interacts with pathogens, helps in triggering an immune response, and plays an important role in innate immunity. Deficiency in MBL expression is associated with susceptibility to RVVC (Carvalho et al., 2010) and pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) (Yanagisawa et al., 2020). Polymorphism in MBL is also associated with chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis and Candida infection (Vaid et al., 2007).

SNPs in TLR lead to genetic variation that results in susceptibility to Candida and Aspergillus infections (Cunha et al., 2010; Table 1). Mutation in TLR1 is associated with candidemia (Ferwerda et al., 2009; Plantinga et al., 2009, 2012). Genetic variation in the PRR TLR4 can also make an individual susceptible to diseases like IPA (Cunha and Carvalho, 2019). Polymorphism in Asp299Gly and Thr399lle present in the TLR4 impacts hyporesponsiveness to lipopolysaccharide signaling in epithelial cells or alveolar macrophages and results in chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (Arbour et al., 2000; Carvalho et al., 2008). In addition, polymorphism in immune response NOD2 (nucleotide binding oligomerization domain containing 2) gene results in IPA. Variation in another receptor type RLR is also associated with Candida infection (Gresnigt et al., 2018; Jaeger et al., 2019). Thus, a mutation in the gene coding for a receptor is an important susceptibility factor for CMC and plays a central role in host immune response (Glocker et al., 2009).

Genetic Polymorphism of the Immune System Linked to Fungal Infections

Genetic variants leading to immunological susceptibility have long been recognized with a few immunodeficiencies characterized by their vulnerability to IFIs (Pana et al., 2014; Maskarinec et al., 2016; Merkhofer and Klein, 2020). Deficiency in PTX3 (Pentraxin 3), which is involved in innate immunity, leads to susceptibility toward IA (Garlanda et al., 2002). Recently, downregulation of cluster of differentiation molecules CD50 and CD80 has been shown to make an individual susceptible to Trichophyton infection (Hamad et al., 2018). Polymorphism in the CX3CR1 gene (C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1, encoding chemokine receptor) is associated with fungal infection in the gut, and it plays an important role in antifungal activity through activation of Th17 cells and IgG antibody response (Kumar et al., 2018). Candida infections (ranging from mucosal to bloodstream, including deep-seated infections) are influenced by genetic variants in the human genomes like polymorphism in signal transducer and activator of transcription protein-coding genes STAT1 and STAT3 (Plantinga et al., 2012; Smeekens et al., 2013). The important adaptor protein CARD9 (caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9) is involved in signal transduction from a variety of receptors, and mutation in this gene not only leads to mucosal infection but also is associated with IFIs, development of autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and cancer (Glocker et al., 2009; Drummond et al., 2018). CARD9 plays an important role in Th17 cell differentiation and helps in the release of cytokines (Vautier et al., 2010; Speakman et al., 2020; Vornholz and Ruland, 2020). Recently, defects in CARD9 and STAT3 have been found to cause IFI with gastrointestinal manifestations (Vinh, 2019) and mutation in STAT3 results in reduced Th17 cells causing candidiasis (Engelhardt and Grimbacher, 2012). A heterozygous missense mutation in STAT1 is associated with coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis (Sampaio et al., 2013). Mutation in another transcription factor GATA2 (GATA-binding factor 2) makes patients vulnerable to myeloid malignancy who have a high risk for treatment-associated IFIs involving aspergillosis and candidiasis (Spinner et al., 2014; Donadieu et al., 2018; Vedula et al., 2021). ZNF341 (zinc finger protein 341) is a transcription factor that resides in the nucleus and regulates the activity of STAT1 and STAT3 genes. ZNF341-deficient patients lack Th17 cells and have an excess of Th2 cells and low memory B cells. Upon Candida infection, individuals with STAT3 mutation result in hyper–immunoglobulin E syndrome (HIES) associated with defective Th17 cell differentiation and characterized by elevated serum IgE (Béziat et al., 2018; Frey-Jakobs et al., 2018; Egri et al., 2021). Patients with AIRE (autoimmune regulator) gene mutations are also susceptible to Candida albicans infection and present themselves with autoimmune disorders (Pedroza et al., 2012; de Albuquerque et al., 2018). Genes encoding immune molecules of the adaptive immune system play an important role in controlling fungal invasion (Kawai and Akira, 2007). Immunoglobulins (Igs) IgG, IgA, IgE, and IgM as part of the humoral adaptive immunity mediate protection through direct actions on fungal cells, and classical mechanisms such as phagocytosis and complement activation are affected in case of mutations in genes coding for those Igs (Kaufman, 1985; Lionakis et al., 2014; Table 1). MHC class II defects lead to primary immunodeficiency disease (PIDD) and make individuals susceptible to a high rate of fungal infection like Candidiasis and PCP (Lanternier et al., 2013; Abd Elaziz et al., 2020). Mutation in CARD9 and DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) among PIDD individuals makes them susceptible to Malassezia infection, and deficiency in STAT3 leads to IPA (Abd Elaziz et al., 2020). Summary of the immune-related genes responsible for susceptibility to fungal infection is highlighted in Table 1.

Interleukins (ILs) play a crucial role during fungal infection and help in the maturation of B cells and antibody secretion, which helps fight fungal infections (Antachopoulos and Roilides, 2005; Verma et al., 2015; Sparber and LeibundGut-Landmann, 2019; Griffiths et al., 2021). Mutations in genes encoding for members of the IL-1 family are associated with acute and chronic inflammation and are essential for the innate response to infection (Caffrey et al., 2015; Griffiths et al., 2021). Genetic variation in IL-6 results in blastomycosis (Merkhofer et al., 2019), and defect in IL-10 and IL-6 signaling affects STAT3, a key immune response molecule. Genetic variation in IL-10 has also been found to be the underlying cause of susceptibility toward fungal infections like IA (Zaas, 2006). IL-10 mutation makes an individual susceptible to Candida and Coccidiodes immitis infection (Fierer, 2006), and IL-4 polymorphism resulted in susceptibility toward Candida infection (Babula et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2005). SNP in rs2243250, known to influence IL-4 production, is associated with susceptibility to PCP in HIV-positive patients (Wójtowicz et al., 2019). In addition, deficiency of interleukin IL-17 and IL-22 production as a result of genetic mutation has been reported to be the cause of RVVC (Sobel, 2016). IL-2 mutation too predisposes individuals to invasive fungal infection like histoplasmosis by affecting T cell functions (Smeekens et al., 2013; Lionakis et al., 2014; Kumaresan et al., 2017; Pathakumari et al., 2020). The emerging role of the IL-12 family of cytokines in the fight against candidiasis has been reported (Ashman et al., 2011; Thompson and Orr, 2018). IL-12RB1 (interleukin 12 receptor subunit beta 1) impairs the development of human IL-17 producing T cells (Huppler et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2012; Thompson and Orr, 2018), and mutations inherited might be responsible for histoplasmosis (León-Lara et al., 2020). RAR-related orphan receptor C (RORC) encoding transcription factors play an integral role in both IL-17 and IFNγ pathways in CMC (De Luca et al., 2007; Constantine and Lionakis, 2020). Deficiency of tyrosine kinase 2 (Tyk2) that participates in signal transduction for various cytokine receptors leads to impaired helper T cell type 1 (Th1) differentiation and accelerated helper T cell type 2 (Th2) differentiation in candidiasis (Minegishi et al., 2006). Mutation in the main inflammasome NLRP3 (NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3), associated with fungal infection, leads to susceptibility toward RVVC or IPA (Kasper et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Briard et al., 2021). Also, mutations in key recombination activating genes (RAG1 and RAG2) lead to loss of T and B cells, making individuals susceptible to CMC and a broad spectrum of pathogens (Schuetz et al., 2008; Delmonte et al., 2018). Genetic polymorphism in the IL-17 family genes, which encode for the Th17 cellular differentiation, results in an individual’s susceptibility toward fungal infection (Hamad et al., 2018). One of the key signaling molecule pathways, the IL-17R signaling is dependent on Act1 (Actin1—a conserved protein that helps in key cellular processes), and mutation in the gene coding for Actin1 leads to defect in IL-17R signaling pathway, which ultimately fails to provide immunity against CMC (Boisson et al., 2013). IL-17RA binds to homo- and heterodimers of IL-17A and IL-17F, and its deficiency or genetic mutation in any of the gene coding for receptors IL-17RA or IL-17RC leads to CMC (Puel et al., 2011; Sawada et al., 2021).

Mutation in DOCK8 characterized by elevated IgE level is also known to be responsible for recurrent fungal infections like IA and mucocutaneous candidiasis (Biggs et al., 2017; Nahum, 2017). During Aspergillus infection, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) enhances the phagocytic activity and the polymorphic site in TNF promotor predisposes individuals to IA (Roilides et al., 1998; Sainz et al., 2007). Neutrophil cytosolic factors (NCFs) are part of the group of proteins that form the enzyme complex called NADPH oxidase, and mutation in any of the key genes NCF1, NCF2, and NCF4 leads to impaired fungal eradication (as in aspergillosis) due to non-functional NADPH oxidase (Panday et al., 2015; Giardino et al., 2017; Dinauer, 2019; Wu et al., 2019). Decreased myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (inability to produce hypochlorous acid) in neutrophils leads to delayed killing of pathogen and makes an individual susceptible to invasive Candida infection (Aratani et al., 1999; Merkhofer and Klein, 2020). Myeloperoxidase mutants lead to impaired ROS production, making the host susceptible to infection, and thus, both MPO and NADPH oxidase mutants are unable to eradicate fungal threats like chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) and IA (Lehrer and Cline, 1969; Aratani et al., 2004; Segal and Romani, 2009; Ren et al., 2012). Cytochrome b -245 is a primary component of the microbicidal oxidase system of phagocytes encoded by the alpha and beta chains CYBA and CYBB/Nox2 (NADPH oxidase 2), respectively (Stasia, 2016), and cytochrome b deficiency is also linked to CGD (Clark, 1999; Stasia et al., 2003; Kutukculer et al., 2019). Recently, it has been reported that mutants in the ferroxidase gene make individuals susceptible to mucormycosis (Navarro-Mendoza et al., 2018), an infection that has been affecting COVID-19 patients (Raut and Huy, 2021). Thus, mutations of key genes of the immune system play an important role in fungal resistance, and interestingly, genetic polymorphisms in these genes have revealed some links with human ancestry.

Human Ancestry and Genetic Predisposition to Fungal Infections

There is limited research investigating the link between genetic polymorphism in key immune genes, human ancestry, and susceptibility toward fungal infection (Figure 1). But recent research outcomes aided by genomic sequencing point toward an interesting fact. Infection with the fungus Coccidioides immitis among Filipino ancestry was found to be common among men and non-white persons causing coccidioidomycosis (van Burik and Magee, 2001). Studies on DNA, which provides genetic information transferred from ancestors to their family members and relatives, indicate that the Hmong ancestry are more susceptible to fungal infection (Xiong et al., 2013). In another report, genetic differentiation among the Hmong ancestry originating from Wisconsin makes them more susceptible to blastomycosis. The Chinese Han population was found to suffer due to poor metabolism as a result of the CYP2C19 gene (cytochrome P450 2C19) polymorphism involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics. This is one of the direct evidence to prove the role played by genetic polymorphisms in IFIs among a particular human race. Interestingly, polymorphism in the CYP2C19 allele (because of the presence of variant rs12248560) has been reported to cause aspergillosis among the Chileans (Espinoza et al., 2019). Similarly, deficiency as a result of a mutation in the gene coding for CD40L (binds to CD40 cells and plays role in B cell proliferation) influences susceptibility to PCP among people belonging to the Chinese mainland (Du et al., 2019). It was also reported that genetic variation in CARD9 led to increased susceptibility toward Candida infections in the African population (Rosentul et al., 2012).

SNP plays an important role in fungal infection affecting particular ancestral populations (Hughes et al., 2008; Dominguez-Andres and Netea, 2019). SNPs in genes like ARNT2 (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator 2) and CX3CR1 are responsible for cytokine activation, and polymorphism in these genes has been found to play an important role in the invasiveness of aspergillosis infection among European ancestry (Lupiañez et al., 2020). Variations in the PRR MBL and mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2) proteins were shown to be responsible for sporotrichosis in the Chinese population. It was observed that individuals with elevated levels of the protein are more susceptible to Sporothrix infection (Bao et al., 2019). Another importance of SNP is associated with the varying protein expression levels associated with autoimmune diseases (Lionakis, 2012; Jonkers and Wijmenga, 2017). SNPs in cytokine coding genes influence the low production of TNFα, IFNγ, and IL-10, and it was observed that these variations make the Caucasian population susceptible to fungal infections (Larcombe et al., 2005). In a recent study, genetic variant of the key immune adapter MyD88 (myeloid differentiation factor 88) in the Chinese Han population was found to be associated with higher fungal infection and it was shown that the defect in Dectin1 was the primary cause (Chen et al., 2019). Susceptibility to candidiasis and IPA as a result of a defect in Dectin1 was observed in the Dutch family (Ferwerda et al., 2009; Chai et al., 2011). In addition, susceptibility to histoplasmosis as a result of the human leukocyte antigen B22 (HLA-B22) variant was reported in the Mexican population (Taylor et al., 1997). The human race thus plays a crucial role in fungal invasion as seen among white transplant recipients who are more susceptible compared to black recipients due to differences in their pharmacogenetics (Boehme et al., 2014). All the above studies show direct links of human ancestry to fungal diseases and indicate how genetic mutations among the human race make them predisposed to certain fungal infections (Table 1).

Discussion

Fungi play an important role in the human microbiome (Huseyin et al., 2017; Perez et al., 2021; Tiew et al., 2021). In this review, we have focused on genetic predisposition to human fungal infections and discussed the link that exists between ancestry and susceptibility to IFIs. Among those fungi that are commensal with the warm-blooded host, few turn pathogenic under not so well-defined conditions (Hall and Noverr, 2017; Jacobsen, 2019; Limon et al., 2017). Such conversion to pathogenic forms is aided by external factors like environment, immunological status, and most importantly host genetics (Kobayashi, 1996; Kumar et al., 2018; Figure 1). As we learn more about fungal biology, we also understand genetic signatures in the host that make them prone to fungal infections. This is explained by the term genetic predisposition, and external players like the environment also play a role in triggering an autoimmune, inflammatory, or allergic reaction to fungal infections (Figure 1). Identification of fungal allergens has become challenging because most of the allergens mimic immune molecules (Pfavayi et al., 2020). We have seen how mutations in key recognition molecules (Table 1) play a trigger for several fungal infections. We looked into variations introduced by SNPs that are present in the immune response genes (Table 1) critical for fungal infections. The polymorphism in the immune genes (PTX3, CX3CR1, CARD9, STAT3, and others, Figure 1) make the host susceptible (Garlanda et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2018; Vinh, 2019), and defect in interleukins (e.g., IL-4, IL-10) leads to genetic predisposition toward fungal infection (Babula et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2005; Zaas, 2006; Table 1). The study of these genes helps us to understand the relationship between genetic polymorphism and the cellular phenotype of host, pathogen, and associated defense mechanisms (Sardinha et al., 2011). Thus, the composition of both host and pathogen plays important role in disease progression, and the challenge is to identify the genetic components involved in pathogenesis.

A few studies point toward a link between human ancestry and genetic predisposition to fungal infections (van Burik and Magee, 2001; Ferwerda et al., 2009; Xiong et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2019; Du et al., 2019; Espinoza et al., 2019; Table 1). Mutations in several components of the immune system make certain human ancestral descendants more prone to fungal infections. Few studies have looked into genetic associations and human ancestry. This aspect is an important and emerging research area in terms of population genetics (Hirschhorn et al., 2002; Gnat et al., 2021). Mutation in key genes relating to the immune system of the host makes certain ancestral descendants susceptible to fungal infections as we observe in the case of certain European, African, and Caucasian individuals (Larcombe et al., 2005; Kwizera et al., 2019; Pfavayi et al., 2020), making them more susceptible to emerging fungal pathogens (Figure 1). Such fungi are a threat to global public health and can colonize the skin, spread from person to person, and cause many high-risk diseases (Lamoth and Kontoyiannis, 2018). To deal with such organisms, we require better surveillance methods, rapid and accurate diagnostics, and decolonization protocols that include administration of antimicrobial or antiseptic agents and new antifungal drugs (Jeffery-Smith et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2019; Chowdhary et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2020; Steenwyk et al., 2020). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) would help us to evaluate the difference in the DNA sequences and understand heritability, disease risk, and susceptibility to antifungals (Bloom et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2020; Figure 1). From genome sequencing, genomic variations like SNPs, variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), and insertion/deletions (Indels) can be identified. Structural genome variations like aneuploidy and copy number variations (CNVs) also provide important clues to fungal virulence (Tsai and Nelliat, 2019). During fungal microevolution, many of these events like insertion/deletion of genes, loss of heterozygosity (LOH), and genome plasticity help fungus to adapt against antifungal drugs and harsh host environment (Beekman and Ene, 2020). Thus, as part of preventive medicine, a better understanding of host genetics behind fungal infection will help us to study infectious diseases through modern genomic approaches and offer personalized therapy against invasive fungal diseases.

Author Contributions

SD conceptualized, reviewed, and approved the manuscript. BN drafted the manuscript, revised the article critically, and provided critical suggestions. SA contributed toward artwork and reviewed the manuscript. SL provided critical review and revised intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge funding from the Department of Health Research (DHR), the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) New Delhi for funding our research program. We also thank Yenepoya Research Centre for providing laboratory facilities.

Abbreviations

- PRR

Pattern Recognition Receptor

- PAMP

Pathogen Associated Molecular Patterns

- TLR

Toll-like Receptor

- CLR

C-type Lectin Receptor

- NLR

Nod-like Receptor

- RLR

Rig-like Receptor

- Th cells

Helper T cells

- Tc cells

Cytotoxic T cells

- Treg cells

Regulatory T cells

- ILs

Interleukins

- Igs

Immunoglobulins

- MBL

Mannose Binding Lectin

- CARD9

Caspase Recruitment Domain-containing protein 9

- CD

Cluster of Differentiation

- NET

Neutrophil Extracellular Trap

- IFI

Invasive Fungal Infection

- PTX3

Pentraxin3

- CX3CR1

C-X 3-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 1

- Act1

Actin 1

- SNPs

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

- CYP2C19

Cytochrome P450 2C19

- ARNT2

Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator 2

- TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha

- IFNγ

Interferon-gamma

- MyD88

Myeloid differentiation primary response 88

- STAT1

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1

- STAT3

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3

- AMP

Anti-Microbial Peptide

- APC

Antigen Processing Cell

- GWAS

Genome-Wide Association Studies

- VNTR

Variable Number Tandem Repeat

- Indel

Insertions Deletions

- CNV

Copy Number Variation

- LOH

Loss of Heterozygosity

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- CGD

Chronic Granulomatous Disease

- CYBB

Cytochrome B beta chain

- CYBA

Cytochrome B alpha chain

- MASP-2

Mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2

- NADPH

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate

- NCF

Neutrophil Cytosolic Factor

- CLEC7A

C-Type Lectin Domain Containing 7A

- NOD2

Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain containing 2

- RAG

Recombination Activating Genes

- GATA2

GATA-binding factor 2

- ZNF341

Zinc Finger Protein 341

- IL-12RB1

Interleukin 12 Receptor subunit Beta 1

- AIRE

Autoimmune Regulator

- RORC

RAR-related Orphan Receptor C

- DOCK8

Dedicator of Cytokinesis 8

- Tyk2

Tyrosine Kinase 2

- CMC

Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

- NLRP3

NOD-, LRR- and Pyrin domain-containing protein 3

- PCP

Pneumocystis pneumonia

- IPA

Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis

- HLA-B22

Human Leukocyte Antigen–B22

- Nox2

NADPH oxidase 2

- PDA

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

- IA

Invasive Aspergillosis

- HIES

Hyper–Immunoglobulin E Syndrome

- RVVC

Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- PIDD

Primary Immunodeficiency disease.

Footnotes

Funding. SD was supported by the Grant in Aid program of DHR GIA/2019/000620/PRCGIA. BN is a JRF supported by Yenepoya (Deemed to be University). SA was supported by an ICMR grant to SD.

References

- Abd Elaziz D., Abd El-Ghany M., Meshaal S., El Hawary R., Lotfy S., Galal N., et al. (2020). Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiency diseases. Clin. Immunol. Orlando Fla 219:108553. 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. (2006). Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124 783–801. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antachopoulos C., Roilides E. (2005). Cytokines and fungal infections. Br. J. Haematol. 129 583–596. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05498.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aratani Y., Koyama H., Nyui S., Suzuki K., Kura F., Maeda N. (1999). Severe impairment in early host defense against Candida albicans in mice deficient in myeloperoxidase. Infect. Immun. 67 1828–1836. 10.1128/IAI.67.4.1828-1836.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aratani Y., Kura F., Watanabe H., Akagawa H., Takano Y., Suzuki K., et al. (2004). In vivo role of myeloperoxidase for the host defense. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 57:S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour N. C., Lorenz E., Schutte B. C., Zabner J., Kline J. N., Jones M., et al. (2000). TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat. Genet. 25 187–191. 10.1038/76048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aristizabal B., González Á. (2013). “Innate immune system,” in Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside, eds Anaya J. M., Shoenfeld Y., Rojas-Villarraga A., Levy R. A., Cervera R. (Bogota: El Rosario University Press; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman R. B., Vijayan D., Wells C. A. (2011). IL-12 and related cytokines: function and regulatory implications in Candida albicans infection. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011:686597. 10.1155/2011/686597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aykut B., Pushalkar S., Chen R., Li Q., Abengozar R., Kim J. I., et al. (2019). The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 574 264–267. 10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babula O., Lazdâne G., Kroica J., Linhares I. M., Ledger W. J., Witkin S. S. (2005). Frequency of interleukin-4 (IL-4) -589 gene polymorphism and vaginal concentrations of IL-4, nitric oxide, and mannose-binding lectin in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 40 1258–1262. 10.1086/429246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao F., Fu X., Yu G., Wang Z., Liu H., Zhang F. (2019). Mannose-Binding lectin and mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 genotypes and serum levels in patients with sporotrichosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101 1322–1324. 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman C. N., Ene I. V. (2020). Short-term evolution strategies for host adaptation and drug escape in human fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 16:e1008519. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béziat V., Li J., Lin J.-X., Ma C. S., Li P., Bousfiha A., et al. (2018). A recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome by disruption of ZNF341-dependent STAT3 transcription and activity. Sci. Immunol. 3:eaat4956. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat4956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs C. M., Keles S., Chatila T. A. (2017). DOCK8 deficiency: insights into pathophysiology, clinical features and management. Clin. Immunol. Orlando Fla 181 75–82. 10.1016/j.clim.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M. (2011). The fungi: 1, 2, 3. 5.1 million species? Am. J. Bot. 98 426–438. 10.3732/ajb.1000298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J. S., Boocock J., Treusch S., Sadhu M. J., Day L., Oates-Barker H., et al. (2019). Rare variants contribute disproportionately to quantitative trait variation in yeast. ELife 8:e49212. 10.7554/eLife.49212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehme A. K., McGwin G., Andes D. R., Lyon G. M., Chiller T., Pappas P. G., et al. (2014). Race and invasive fungal infection in solid organ transplant recipients. Ethn. Dis. 24 382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson B., Wang C., Pedergnana V., Wu L., Cypowyj S., Rybojad M., et al. (2013). An ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity 39 676–686. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briard B., Malireddi R. K. S., Kanneganti T.-D. (2021). Role of inflammasomes/pyroptosis and PANoptosis during fungal infection. PLoS Pathog. 17:e1009358. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey A. K., Lehmann M. M., Zickovich J. M., Espinosa V., Shepardson K. M., Watschke C. P., et al. (2015). IL-1α signaling is critical for leukocyte recruitment after pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus challenge. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1004625. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carris L. M., Little C. R., Stiles C. M. (2012). Introduction to Fungi. The Plant Health Instructor. 10.1094/PHI-I-2012-0426-01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A., Cunha C., Pasqualotto A. C., Pitzurra L., Denning D. W., Romani L. (2010). Genetic variability of innate immunity impacts human susceptibility to fungal diseases. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 14 e460–e468. 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A., Pasqualotto A. C., Pitzurra L., Romani L., Denning D. W., Rodrigues F. (2008). Polymorphisms in toll-like receptor genes and susceptibility to pulmonary aspergillosis. J. Infect. Dis. 197 618–621. 10.1086/526500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai L. Y. A., de Boer M. G. J., van der Velden W. J. F. M., Plantinga T. S., van Spriel A. B., Jacobs C., et al. (2011). The Y238X stop codon polymorphism in the human β-glucan receptor dectin-1 and susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis. J. Infect. Dis. 203 736–743. 10.1093/infdis/jiq102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin D. D. (2010). Overview of the immune response. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125 S3–S23. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.-J., Hu R., Jiang X.-Y., Wu Y., He Z.-P., Chen J.-Y., et al. (2019). Dectin-1 rs3901533 and rs7309123 polymorphisms increase susceptibility to pulmonary invasive fungal disease in patients with acute myeloid leukemia from a Chinese Han population. Curr. Med. Sci. 39 906–912. 10.1007/s11596-019-2122-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P., Xanthaki D., Rose S. J., Haywood M., Reiser H., Morley B. J. (2005). Linkage analysis of the genetic determinants of T-cell IL-4 secretion, and identification of Flj20274 as a putative candidate gene. Genes Immun. 6 290–297. 10.1038/sj.gene.6364192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary A., Tarai B., Singh A., Sharma A. (2020). Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris infections in critically Ill coronavirus disease patients, India, April-July 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26 2694–2696. 10.3201/eid2611.203504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. A. (1999). Activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase. J. Infect. Dis. 179 S309–S317. 10.1086/513849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates M., Blanchard S., MacLeod A. S. (2018). Innate antimicrobial immunity in the skin: a protective barrier against bacteria, viruses, and fungi. PLoS Pathog. 14:e1007353. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine G. M., Lionakis M. S. (2020). Recent advances in understanding inherited deficiencies in immunity to infections. F1000Res. 9:F1000 Faculty Rev-243. 10.12688/f1000research.22036.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha C., Carvalho A. (2019). Genetic defects in fungal recognition and susceptibility to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Med. Mycol. 57 S211–S218. 10.1093/mmy/myy057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha C., Di Ianni M., Bozza S., Giovannini G., Zagarella S., Zelante T., et al. (2010). Dectin-1 Y238X polymorphism associates with susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis in hematopoietic transplantation through impairment of both recipient- and donor-dependent mechanisms of antifungal immunity. Blood 116 5394–5402. 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha D., de O., Leão-Cordeiro J. A. B., Paula H. D. S. C., Ataides F. S., Saddi V. A., et al. (2018). Association between polymorphisms in the genes encoding toll-like receptors and dectin-1 and susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis: a systematic review. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 51 725–730. 10.1590/0037-8682-0314-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque J. A. T., Banerjee P. P., Castoldi A., Ma R., Zurro N. B., Ynoue L. H., et al. (2018). The role of AIRE in the immunity against Candida albicans in a model of human macrophages. Front. Immunol. 9:567. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca A., Montagnoli C., Zelante T., Bonifazi P., Bozza S., Moretti S., et al. (2007). Functional yet balanced reactivity to Candida albicans requires TRIF, MyD88, and IDO-dependent inhibition of Rorc. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 179 5999–6008. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pauw B. E. (2011). What are fungal infections? Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 3:e2011001. 10.4084/MJHID.2011.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pilar Jiménez-A M., Viriyakosol S., Walls L., Datta S. K., Kirkland T., Heinsbroek S. E. M., et al. (2008). Susceptibility to Coccidioides species in C57BL/6 mice is associated with expression of a truncated splice variant of Dectin-1 (Clec7a). Genes Immun. 9 338–348. 10.1038/gene.2008.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmonte O. M., Schuetz C., Notarangelo L. D. (2018). RAG deficiency: two genes, many diseases. J. Clin. Immunol. 38 646–655. 10.1007/s10875-018-0537-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer M. C. (2019). Insights into the NOX NADPH oxidases using heterologous whole cell assays. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 1982 139–151. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9424-3_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy D. C., Jirtle R. L. (2008). Environmental epigenomics in human health and disease. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 49 4–8. 10.1002/em.20366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Andres J., Netea M. G. (2019). Impact of historic migrations and evolutionary processes on human immunity. Trends Immunol. 40 1105–1119. 10.1016/j.it.2019.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadieu J., Lamant M., Fieschi C., de Fontbrune F. S., Caye A., Ouachee M., et al. (2018). Natural history of GATA2 deficiency in a survey of 79 French and Belgian patients. Haematologica 103 1278–1287. 10.3324/haematol.2017.181909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond R. A., Franco L. M., Lionakis M. S. (2018). Human CARD9: a critical molecule of fungal immune surveillance. Front. Immunol. 9:1836. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond R. A., Gaffen S. L., Hise A. G., Brown G. D. (2014). Innate defense against fungal pathogens. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5:a019620. 10.1101/cshperspect.a019620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Tang W., Chen X., Zeng T., Wang Y., Chen Z., et al. (2019). Clinical, genetic and immunological characteristics of 40 Chinese patients with CD40 ligand deficiency. Scand. J. Immunol. 90:e12798. 10.1111/sji.12798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury E. M., Day J. P., Maria Vespasiani D., Thüringer Y., Tolosana I., Smith S. C., et al. (2019). Host-pathogen coevolution increases genetic variation in susceptibility to infection. ELife 8:e46440. 10.7554/eLife.46440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eades C. P., Armstrong-James D. P. H. (2019). Invasive fungal infections in the immunocompromised host: mechanistic insights in an era of changing immunotherapeutics. Med. Mycol. 57 S307–S317. 10.1093/mmy/myy136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egri N., Esteve-Solé A., Deyà-Martínez À, Ortiz de Landazuri I., Vlagea A., García A. P., et al. (2021). Primary immunodeficiency and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis: pathophysiological, diagnostic, and therapeutic approaches. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 49 118–127. 10.15586/aei.v49i1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt K. R., Grimbacher B. (2012). Mendelian traits causing susceptibility to mucocutaneous fungal infections in human subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129 294–305; quiz 306–307. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza N., Galdames J., Navea D., Farfán M. J., Salas C. (2019). Frequency of the CYP2C19∗17 polymorphism in a Chilean population and its effect on voriconazole plasma concentration in immunocompromised children. Sci. Rep. 9:8863. 10.1038/s41598-019-45345-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda B., Ferwerda G., Plantinga T. S., Willment J. A., van Spriel A. B., Venselaar H., et al. (2009). Human dectin-1 deficiency and mucocutaneous fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 361 1760–1767. 10.1056/NEJMoa0901053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer J. (2006). IL-10 and susceptibility to Coccidioides immitis infection. Trends Microbiol. 14 426–427. 10.1016/j.tim.2006.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. C., Gurr S. J., Cuomo C. A., Blehert D. S., Jin H., Stukenbrock E. H., et al. (2020). Threats posed by the fungal kingdom to humans, wildlife, and agriculture. mBio 11:e00449-20. 10.1128/mBio.00449-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey-Jakobs S., Hartberger J. M., Fliegauf M., Bossen C., Wehmeyer M. L., Neubauer J. C., et al. (2018). ZNF341 controls STAT3 expression and thereby immunocompetence. Sci. Immunol. 3:eaat4941. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlanda C., Hirsch E., Bozza S., Salustri A., De Acetis M., Nota R., et al. (2002). Non-redundant role of the long pentraxin PTX3 in anti-fungal innate immune response. Nature 420 182–186. 10.1038/nature01195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardino G., Cicalese M. P., Delmonte O., Migliavacca M., Palterer B., Loffredo L., et al. (2017). NADPH oxidase deficiency: a multisystem approach. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017:4590127. 10.1155/2017/4590127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glocker E.-O., Hennigs A., Nabavi M., Schäffer A. A., Woellner C., Salzer U., et al. (2009). A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 361 1727–1735. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnat S., Łagowski D., Nowakiewicz A. (2021). Genetic predisposition and its heredity in the context of increased prevalence of dermatophytoses. Mycopathologia 186 163–176. 10.1007/s11046-021-00529-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J. K., Davenport E. R., Clark A. G., Ley R. E. (2017). The relationship between the human genome and microbiome comes into view. Annu. Rev. Genet. 51 413–433. 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal S., Castrillón-Betancur J. C., Klaile E., Slevogt H. (2018). The interaction of human pathogenic fungi with C-Type lectin receptors. Front. Immunol 9:1261. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresnigt M. S., Cunha C., Jaeger M., Gonçalves S. M., Malireddi R. K. S., Ammerdorffer A., et al. (2018). Genetic deficiency of NOD2 confers resistance to invasive aspergillosis. Nat. Commun. 9:2636. 10.1038/s41467-018-04912-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J. S., Camilli G., Kotowicz N. K., Ho J., Richardson J. P., Naglik J. R. (2021). Role for IL-1 family cytokines in fungal infections. Front. Microbiol. 12:633047. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.633047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Zhang R., Li Y., Wang Z., Ishchuk O. P., Ahmad K. M., et al. (2020). Understand the genomic diversity and evolution of fungal pathogen Candida glabrata by genome-wide analysis of genetic variations. Methods San Diego Calif. 176 82–90. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. A., Noverr M. C. (2017). Fungal interactions with the human host: exploring the spectrum of symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 40 58–64. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad M., Mohammad M. G., Abu-Elteen K. H. (2018). Immunity to human fungal infections,” in Fungi Biology and Applications, 3rd Edn, 275–298. 10.1002/9781119374312.ch11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatinguais R., Willment J. A., Brown G. D. (2020). PAMPs of the fungal cell wall and mammalian PRRs. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 425 187–223. 10.1007/82_2020_201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth D. L., Rossman A. Y. (1997). Where are all the undescribed fungi? Phytopathology 87 888–891. 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.9.888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn J. N., Lohmueller K., Byrne E., Hirschhorn K. (2002). A comprehensive review of genetic association studies. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 4 45–61. 10.1097/00125817-200203000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A. L., Welch R., Puri V., Matthews C., Haque K., Chanock S. J., et al. (2008). Genome-wide SNP typing reveals signatures of population history. Genomics 92 1–8. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppler A. R., Bishu S., Gaffen S. L. (2012). Mucocutaneous candidiasis: the IL-17 pathway and implications for targeted immunotherapy. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14:217. 10.1186/ar3893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseyin C. E., Rubio R. C., O’Sullivan O., Cotter P. D., Scanlan P. D. (2017). The fungal frontier: a comparative analysis of methods used in the study of the human gut mycobiome. Front. Microbiol. 8:1432. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim A. S., Voelz K. (2017). The mucormycete-host interface. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 40 40–45. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliev I. D., Leonardi I. (2017). Fungal dysbiosis: immunity and interactions at mucosal barriers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17 635–646. 10.1038/nri.2017.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson B. R., Chow N., Forsberg K., Litvintseva A. P., Lockhart S. R., Welsh R., et al. (2019). On the origins of a species: what might explain the rise of Candida auris? J. Fungi Basel Switz. 5:E58. 10.3390/jof5030058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen I. D. (2019). Fungal infection strategies. Virulence 10 835–838. 10.1080/21505594.2019.1682248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger M., Matzaraki V., Aguirre-Gamboa R., Gresnigt M. S., Chu X., Johnson M. D., et al. (2019). A genome-wide functional genomics approach identifies susceptibility pathways to fungal bloodstream infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 220 862–872. 10.1093/infdis/jiz206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery-Smith A., Taori S. K., Schelenz S., Jeffery K., Johnson E. M., Borman A., et al. (2018). Candida auris: a review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31:e00029-17. 10.1128/CMR.00029-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. D., Plantinga T. S., van de Vosse E., Velez Edwards D. R., Smith P. B., Alexander B. D., et al. (2012). Cytokine gene polymorphisms and the outcome of invasive candidiasis: a prospective cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 54 502–510. 10.1093/cid/cir827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers I. H., Wijmenga C. (2017). Context-specific effects of genetic variants associated with autoimmune disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26 R185–R192. 10.1093/hmg/ddx254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper L., König A., Koenig P.-A., Gresnigt M. S., Westman J., Drummond R. A., et al. (2018). The fungal peptide toxin Candidalysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and causes cytolysis in mononuclear phagocytes. Nat. Commun. 9:4260. 10.1038/s41467-018-06607-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman L. (1985). “The role of specific antibodies of different immunoglobulin classes in the rapid diagnosis of systemic mycotic infections,” in Rapid Methods and Automation in Microbiology and Immunology, ed. Habermehl K. O. (Berlin: Springer; ). 10.1007/978-3-642-69943-6_21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Akira S. (2007). TLR signaling. Semin. Immunol. 19 24–32. 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi G. S. (1996). “Disease mechanisms of fungi,” in Medical Microbiology, ed. Baron S. 4th Edn, (Galveston, TX: University of Texas; ). Medical Branch at Galveston. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger W., Vielreicher S., Kapitan M., Jacobsen I. D., Niemiec M. J. (2019). Fungal-Bacterial interactions in health and disease. Pathog. Basel Switz. 8:E70. 10.3390/pathogens8020070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., van de Veerdonk F. L., Netea M. G. (2018). Antifungal immune responses: emerging host-pathogen interactions and translational implications. Genome Med. 10:39. 10.1186/s13073-018-0553-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan P. R., da Silva T. A., Kontoyiannis D. P. (2017). Methods of controlling invasive fungal infections using CD8+ T cells. Front. Immunol. 8:1939. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutukculer N., Aykut A., Karaca N. E., Durmaz A., Aksu G., Genel F., et al. (2019). Chronic granulamatous disease: two decades of experience from a paediatric immunology unit in a country with high rate of consangineous marriages. Scand. J. Immunol. 89:e12737. 10.1111/sji.12737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwizera R., Musaazi J., Meya D. B., Worodria W., Bwanga F., Kajumbula H., et al. (2019). Burden of fungal asthma in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 14:e0216568. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamoth F., Kontoyiannis D. P. (2018). The Candida auris alert: facts and perspectives. J. Infect. Dis. 217 516–520. 10.1093/infdis/jix597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanternier F., Cypowyj S., Picard C., Bustamante J., Lortholary O., Casanova J.-L., et al. (2013). Primary immunodeficiencies underlying fungal infections. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 25 736–747. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcombe L., Rempel J. D., Dembinski I., Tinckam K., Rigatto C., Nickerson P. (2005). Differential cytokine genotype frequencies among Canadian aboriginal and Caucasian populations. Genes Immun. 6 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer R. I., Cline M. J. (1969). Leukocyte myeloperoxidase deficiency and disseminated candidiasis: the role of myeloperoxidase in resistance to Candida infection. J. Clin. Invest. 48 1478–1488. 10.1172/JCI106114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León-Lara X., Hernández-Nieto L., Zamora C. V., Rodríguez-D’Cid R., Gutiérrez M. E. C., Espinosa-Padilla S., et al. (2020). Disseminated infectious disease caused by histoplasma capsulatum in an adult patient as first manifestation of inherited IL-12Rβ1 deficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 40 1051–1054. 10.1007/s10875-020-00828-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limon J. J., Skalski J. H., Underhill D. M. (2017). Commensal fungi in health and disease. Cell Host & Microbe 22 156–165. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionakis M. S. (2012). Genetic susceptibility to fungal infections in humans. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 6 11–22. 10.1007/s12281-011-0076-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionakis M. S., Netea M. G., Holland S. M. (2014). Mendelian genetics of human susceptibility to fungal infection. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4:a019638. 10.1101/cshperspect.a019638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low C.-Y., Rotstein C. (2011). Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Med. Rep. 3:14. 10.3410/M3-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupiañez C. B., Martínez-Bueno M., Sánchez-Maldonado J. M., Badiola J., Cunha C., Springer J., et al. (2020). Polymorphisms within the ARNT2 and CX3CR1 genes are associated with the risk of developing invasive aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 88 e882–e819. 10.1128/IAI.00882-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E. M., Fry R. C. (2018). Environmental influences on the epigenome: exposure- associated DNA methylation in human populations. Annu. Rev. Public Health 39 309–333. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskarinec S. A., Johnson M. D., Perfect J. R. (2016). Genetic susceptibility to fungal infections: what is in the genes? Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 3 81–91. 10.1007/s40588-016-0037-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkhofer R. M., Klein B. S. (2020). Advances in understanding human genetic variations that influence innate immunity to fungi. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:69. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkhofer R. M., O’Neill M. B., Xiong D., Hernandez-Santos N., Dobson H., Fites J. S., et al. (2019). Investigation of genetic susceptibility to blastomycosis reveals interleukin-6 as a potential susceptibility locus. mBio 10:e01224-19. 10.1128/mBio.01224-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minegishi Y., Saito M., Morio T., Watanabe K., Agematsu K., Tsuchiya S., et al. (2006). Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity 25 745–755. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen T. H. (2009). Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22 240–273. 10.1128/CMR.00046-08 Table of Contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum A. (2017). Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis: a spectrum of genetic disorders. LymphoSign J. 4 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo-Ortiz M. A., Gabaldón T. (2019). Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 94 1443–1476. 10.1111/brv.12510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Mendoza M. I., Pérez-Arques C., Murcia L., Martínez-García P., Lax C., Sanchis M., et al. (2018). Components of a new gene family of ferroxidases involved in virulence are functionally specialized in fungal dimorphism. Sci. Rep. 8:7660. 10.1038/s41598-018-26051-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea M. G., Schlitzer A., Placek K., Joosten L. A. B., Schultze J. L. (2019). Innate and adaptive immune memory: an evolutionary continuum in the host’s response to pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 25 13–26. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea M. G., Wijmenga C., O’Neill L. A. J. (2012). Genetic variation in Toll-like receptors and disease susceptibility. Nat. Immunol. 13 535–542. 10.1038/ni.2284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pana Z.-D., Farmaki E., Roilides E. (2014). Host genetics and opportunistic fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20 1254–1264. 10.1111/1469-0691.12800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panday A., Sahoo M. K., Osorio D., Batra S. (2015). NADPH oxidases: an overview from structure to innate immunity-associated pathologies. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 12 5–23. 10.1038/cmi.2014.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathakumari B., Liang G., Liu W. (2020). Immune defence to invasive fungal infections: a comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 130:110550. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patin E. C., Thompson A., Orr S. J. (2019). Pattern recognition receptors in fungal immunity. In Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 89 4–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroza L. A., Kumar V., Sanborn K. B., Mace E. M., Niinikoski H., Nadeau K., et al. (2012). Autoimmune regulator (AIRE) contributes to Dectin-1-induced TNF-α production and complexes with caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (CARD9), spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), and Dectin-1. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129 464–472, 472.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez N. B., Wright F., Vorderstrasse A. (2021). A microbial relationship between irritable bowel syndrome and depressive symptoms. Biol. Res. Nurs. 23 50–64. 10.1177/1099800420940787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfavayi L. T., Sibanda E. N., Mutapi F. (2020). The pathogenesis of fungal-related diseases and allergies in the African population: the state of the evidence and knowledge gaps. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 181 257–269. 10.1159/000506009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantinga T. S., Johnson M. D., Scott W. K., Joosten L. A. B., van der Meer J. W. M., Perfect J. R., et al. (2012). Human genetic susceptibility to Candida infections. Med. Mycol. 50 785–794. 10.3109/13693786.2012.690902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantinga T. S., van der Velden W. J. F. M., Ferwerda B., van Spriel A. B., Adema G., Feuth T., et al. (2009). Early stop polymorphism in human DECTIN-1 is associated with increased candida colonization in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49 724–732. 10.1086/604714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plato A., Hardison S. E., Brown G. D. (2015). Pattern recognition receptors in antifungal immunity. Semin. Immunopathol. 37 97–106. 10.1007/s00281-014-0462-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puel A., Cypowyj S., Bustamante J., Wright J. F., Liu L., Lim H. K., et al. (2011). Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 332 65–68. 10.1126/science.1200439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai L. S., Wijlick L. V., Bougnoux M. E., Bachellier-Bassi S., d’Enfert C. (2021). Regulators of commensal and pathogenic life-styles of an opportunistic fungus–Candida albicans. Yeast 38 243–250. 10.1002/yea.3550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raut A., Huy N. T. (2021). Rising incidence of mucormycosis in patients with COVID-19: another challenge for India amidst the second wave? Lancet Respir. Med. 3 265–264. 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00265-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. M., Gow N. A. R., Brown G. D. (2009). Pattern recognition: recent insights from Dectin-1. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21 30–37. 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R., Fedoriw Y., Willis M. (2012). The molecular pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and treatment of MPO deficiency. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2 2161–2681. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J. M., Harris J. E. (2014). Immunology and skin in health and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 4:a015339. 10.1101/cshperspect.a015339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roilides E., Dimitriadou-Georgiadou A., Sein T., Kadiltsoglou I., Walsh T. J. (1998). Tumor necrosis factor alpha enhances antifungal activities of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear phagocytes against Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect. Immun. 66 5999–6003. 10.1128/IAI.66.12.5999-6003.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales C., Uribe-Querol E. (2017). Phagocytosis: a fundamental process in immunity. BioMed Res. Int. 2017:9042851. 10.1155/2017/9042851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosentul D. C., Plantinga T. S., Scott W. K., Alexander B. D., van de Geer N. M. D., Perfect J. R., et al. (2012). The impact of caspase-12 on susceptibility to candidemia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31 277–280. 10.1007/s10096-011-1307-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz J., Lupiáñez C. B., Segura-Catena J., Vazquez L., Ríos R., Oyonarte S., et al. (2012). Dectin-1 and DC-SIGN polymorphisms associated with invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis infection. PLoS One 7:e32273. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainz J., Pérez E., Hassan L., Moratalla A., Romero A., Collado M. D., et al. (2007). Variable number of tandem repeats of TNF receptor type 2 promoter as genetic biomarker of susceptibility to develop invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis. Hum. Immunol. 68 41–50. 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar F., Brown G. D. (2018). Antifungal innate immunity: a perspective from the last 10 years. J. Innate Immun. 10 373–397. 10.1159/000488539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio E. P., Hsu A. P., Pechacek J., Bax H. I., Dias D. L., Paulson M. L., et al. (2013). Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain-of-function mutations and disseminated coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131 1624–1634. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardinha J. F. J., Tarlé R. G., Fava V. M., Francio A. S., Ramos G. B., Ferreira L. C., et al. (2011). Genetic risk factors for human susceptibility to infections of relevance in dermatology. An. Bras. Dermatol. 86 708–715. 10.1590/s0365-05962011000400013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y., Setoyama A., Sakuragi Y., Saito-Sasaki N., Yoshioka H., Nakamura M. (2021). The role of IL-17-Producing cells in cutaneous fungal infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:5794. 10.3390/ijms22115794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz C., Huck K., Gudowius S., Megahed M., Feyen O., Hubner B., et al. (2008). An immunodeficiency disease with RAG mutations and granulomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 358 2030–2038. 10.1056/NEJMoa073966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal B. H., Romani L. R. (2009). Invasive aspergillosis in chronic granulomatous disease. Med. Mycol. 47(Suppl. 1) S282–S290. 10.1080/13693780902736620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens S. P., van de Veerdonk F. L., Kullberg B. J., Netea M. G. (2013). Genetic susceptibility to Candida infections. EMBO Mol. Med. 5 805–813. 10.1002/emmm.201201678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J. D. (2016). Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 214 15–21. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparber F., LeibundGut-Landmann S. (2019). Interleukin-17 in antifungal immunity. Pathog. Basel Switz. 8:E54. 10.3390/pathogens8020054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speakman E. A., Dambuza I. M., Salazar F., Brown G. D. (2020). T cell antifungal immunity and the role of C-Type lectin receptors. Trends Immunol. 41 61–76. 10.1016/j.it.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinner M. A., Sanchez L. A., Hsu A. P., Shaw P. A., Zerbe C. S., Calvo K. R., et al. (2014). GATA2 deficiency: a protean disorder of hematopoiesis, lymphatics, and immunity. Blood 123 809–821. 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasia M. J. (2016). CYBA encoding p22(phox), the cytochrome b558 alpha polypeptide: gene structure, expression, role and physiopathology. Gene 586 27–35. 10.1016/j.gene.2016.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasia M. J., Brion J.-P., Boutonnat J., Morel F. (2003). Severe clinical forms of cytochrome b-negative chronic granulomatous disease (X91-) in 3 brothers with a point mutation in the promoter region of CYBB. J. Infect. Dis. 188 1593–1604. 10.1086/379035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenwyk J. L., Lind A. L., Ries L. N. A., Dos Reis T. F., Silva L. P., Almeida F., et al. (2020). Pathogenic allodiploid hybrids of Aspergillus fungi. Curr. Biol. CB 30 2495–2507.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. L., Pérez-Mejía A., Yamamoto-Furusho J. K., Granados J. (1997). Immunologic, genetic and social human risk factors associated to histoplasmosis: studies in the State of Guerrero, Mexico. Mycopathologia 138 137–142. 10.1023/a:1006847630347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. R., Tsoni S. V., Willment J. A., Dennehy K. M., Rosas M., Findon H., et al. (2007). Dectin-1 is required for beta-glucan recognition and control of fungal infection. Nat. Immunol. 8 31–38. 10.1038/ni1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A., Orr S. J. (2018). Emerging IL-12 family cytokines in the fight against fungal infections. Cytokine 111 398–407. 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiew P. Y., Jaggi T. K., Chan L. L. Y., Chotirmall S. H. (2021). The airway microbiome in COPD, bronchiectasis and bronchiectasis-COPD overlap. Clin. Respir. J. 15 123–133. 10.1111/crj.13294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H.-J., Nelliat A. (2019). A Double-Edged sword: aneuploidy is a prevalent strategy in fungal adaptation. Genes 10:E787. 10.3390/genes10100787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulfig A., Leichert L. I. (2021). The effects of neutrophil-generated hypochlorous acid and other hypohalous acids on host and pathogens. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78 385–414. 10.1007/s00018-020-03591-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill D. M., Pearlman E. (2015). Immune interactions with pathogenic and commensal fungi: a two-way street. Immunity 43 845–858. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban C. F., Ermert D., Schmid M., Abu-Abed U., Goosmann C., Nacken W., et al. (2009). Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000639. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid M., Kaur S., Sambatakou H., Madan T., Denning D. W., Sarma P. U. (2007). Distinct alleles of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and surfactant proteins A (SP-A) in patients with chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 45 183–186. 10.1515/CCLM.2007.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Burik J. A., Magee P. T. (2001). Aspects of fungal pathogenesis in humans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55 743–772. 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Veerdonk F. L., Kullberg B. J., van der Meer J. W., Gow N. A., Netea M. G. (2008). Host-microbe interactions: innate pattern recognition of fungal pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11 305–312. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vautier S., Sousa M., da G., Brown G. D. (2010). C-type lectins, fungi and Th17 responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21 405–412. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedula R. S., Cheng M. P., Ronayne C. E., Farmakiotis D., Ho V. T., Koo S., et al. (2021). Somatic GATA2 mutations define a subgroup of myeloid malignancy patients at high risk for invasive fungal disease. Blood Adv. 5 54–60. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]