Abstract

Background:

Both marijuana and other illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine/crack, methamphetamines, ecstasy, gamma-hydroxybuterate, and ketamine) have been linked to the occurrence of condomless anal sex (CAS) with casual partners among sexual minority men (SMM) and these associations largely generalize to partnered SMM. Software advances now permit testing the day-level correspondence between participants’ sexual behavior and their own drug use (actor effects) as well as their partners’ (partner-effects).

Methods:

Participants comprised 50 couples (100 individuals) recruited in the New York City metro area. All were 18 or older and identified as cis male. In each couple, at least one partner was 18–29 years old, HIV-negative, reported recent (past 30 day) drug use and recent (past 30 day) CAS with a casual partner or CAS with a non-monogamous or sero-discordant main partner at screening.

Results:

Marijuana was associated with CAS between main partners on days both partners reported its use. A similar pattern was observed for other illicit drugs. Respondents were more likely to report CAS with casual partners on days CAS between main partners occurred. Both marijuana and other illicit drugs were associated with increased likelihood of CAS with casual partners on days a main partner did not use drugs. These associations were attenuated on days where partners reported the use of different drugs.

Conclusions:

The co-occurrence of CAS with main and casual partners maximizes shared sexual risk. Results support the continued emphasis on dyadic HIV prevention interventions and the development of theoretically-based interventions that may address drug use by both partners in the relationship.

Keywords: HIV prevention, interdependence, men who have sex with men, drug use, marijuana, club drugs

1. INTRODUCTION

Sexual contact remains the most common means of HIV transmission among sexual minority men (SMM) in the U.S (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Risk is particularly high among SMM emerging adults (aged 18–29) (CDC, 2020). Main partner HIV transmission is responsible for one to two-thirds of all new HIV infections among SMM, (Goodreau et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2009) and may account for as many as 79% of new infections among emerging adults aged 18 to 24 (Sullivan et al., 2009).

Drug use is among the most consistently identified correlates of sexual HIV transmission risk (e.g., McCarty-Caplan et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2016; Rendina et al., 2015). Evidence consistently links the use of a number of illicit drugs (e.g., crack, cocaine, ecstasy/MDMA, GHB, ketamine, and methamphetamine) with increased likelihood or frequency of condomless anal sex (CAS) with casual partners (e.g., Margolis et al., 2014; Mimiaga et al., 2011; Pines et al., 2014). There is also substantial evidence of this association among partnered SMM (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2016; Starks et al., 2020a; Vosburgh et al., 2012).

Findings related to marijuana are mixed (Morgan et al., 2016; Rendina et al., 2015). At least some evidence indicates it predicts CAS with both main and casual partners (Mitchell et al., 2016). Starks et al. (2020a) suggested equivocal findings regarding marijuana and CAS with casual partners may arise from measurement as well as sample size and sexual agreement composition. Their work indicated that (1) marijuana was associated only with the occurrence – and not the frequency – of CAS; (2) the association between marijuana use and the occurrence of CAS was significantly weaker among men in non-monogamous relationships (compared to single and monogamous men); and (3) the effect size associated with marijuana was modest compared to other illicit drugs (Starks et al., 2020a).

Findings from aggregated data have been reinforced in studies utilizing day-level data. These have shown that CAS and drug use may co-occur within a discrete period of time (Boone et al., 2013; Halkitis et al., 2016; McCarty-Caplan et al., 2014; Pantalone et al., 2010; Parsons at al., 2013; Rendina et al., 2015). Unfortunately, this work has given limited attention to partnered SMM.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling (APIM) has provided an analytic framework for evaluating the relative contribution of personal as well as partner factors in the prediction of an outcome (Kenny et al., 2006). APIM models have been used to evaluate predictors of aggregate drug use (Starks et al., 2019d) and sexual behavior (Mitchell et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2016; Starks et al., 2013; Starks & Parsons, 2014) among partnered SMM. Recent advances in analytic software now permit extension of APIM to a 3-level context (Muthén & Muthén, 2018). With this functionality, it is possible to apply the APIM to day-level data generated by couples.

A substantial portion of APIM research has been informed by Interdependence Theory (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003; Rusbult et al., 1996). Interdependence Theory would suggest that associations between drug use and sex may be a function of both partners’ use on a given day. The use of similar drugs may arise from shared or agreed upon limits for drug use or because use occurs in the context of joint activities. When drug use is a shared or coordinated activity, couples may be more likely to have sex together and less likely to engage in sexual risk with outside partners. This implies that a day-level analysis of couples’ data should incorporate interaction terms to evaluate whether associations between drug use and sexual behavior vary as a function of partners’ use individually and collectively on a given day.

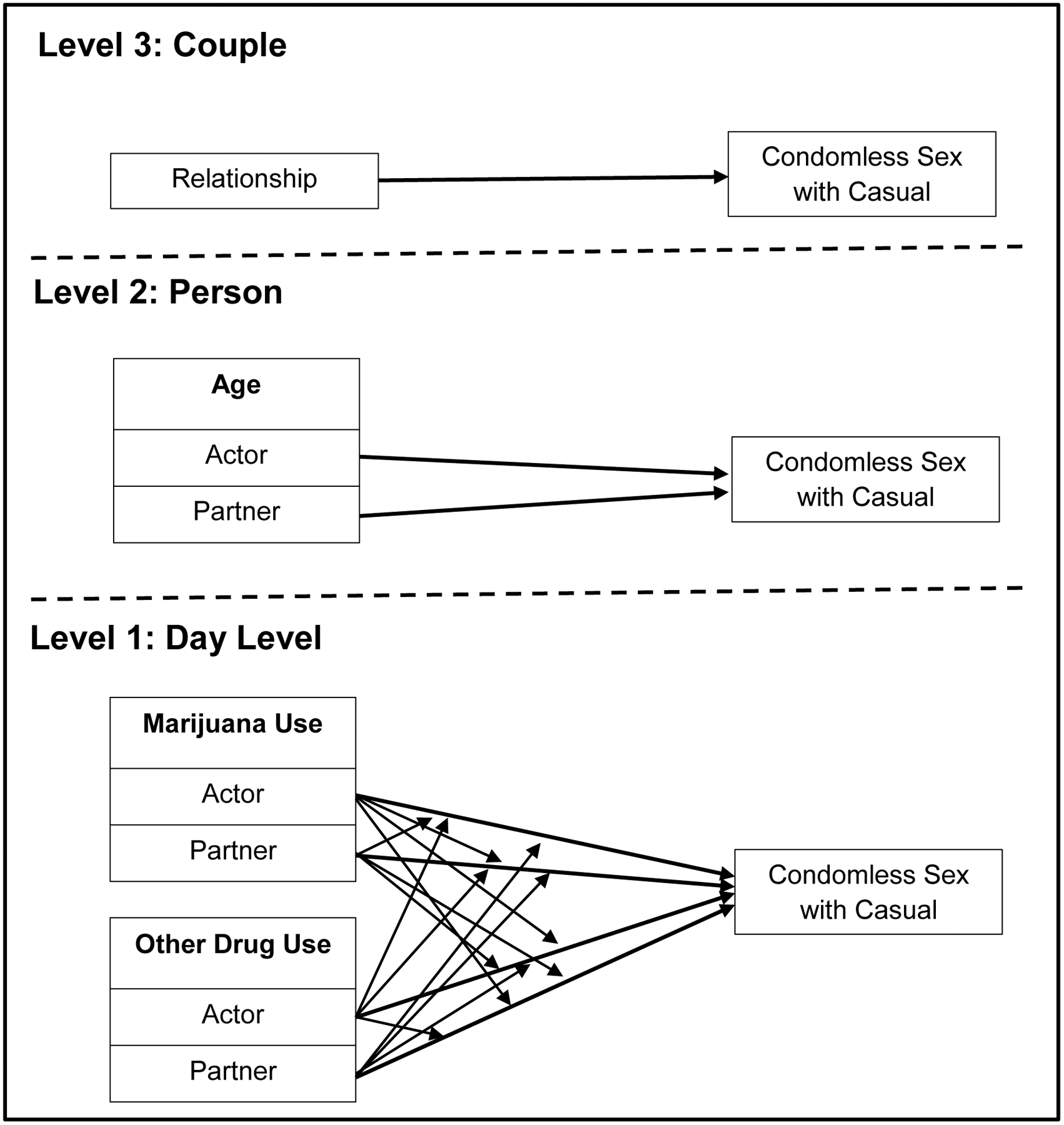

This study tested a hypothesized 3-level APIM predicting day-level sexual behavior (CAS between main partners and CAS with casual partners) from the actor and partner effects of marijuana and other illicit drugs. Figure 1 provides a diagram of associations tested. Drawing on Interdependence Theory, it was hypothesized that actor and partner effects of drug use might interact in the prediction of these sexual behaviors. Furthermore, we hypothesized that CAS with casual partners would be less likely on days that CAS with main partners occurs.

Figure 1.

Exemplar hypothesized multi-level Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)

NOTE: Depicted predictor variables are exemplars and not exhaustive. The hypothesized model included actor and partner effects of age, race and ethnicity, HIV status, and PrEP uptake at Level 2 and the occurrence of condomless sex between main partners at Level 1.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

We utilized baseline data from the Couples Health Project study (NCT03386110). Participants were recruited between 3/2018 and 3/2020 in the New York City metropolitan area. Dyadic participation was required. Relationship status for eligibility was assessed using a single item, “Do you have a main partner, like a boyfriend, lover or spouse?” with a dichotomous (yes/no) response.

Participants identified as cis-male, were 18 years of age or older; and able to speak and read English. In each couple, at least one partner was aged 18–29, at least one was HIV-negative, and at least one reported drug use (including marijuana, cocaine and crack, amphetamines, ecstasy, GHB, ketamine, or nitrates or prescription drug misuse) in the past 30 days. Eligible couples reported a relationship duration of at least three months at screening and at least one partner reported CAS with a casual partner or CAS with a non-monogamous or sero-discordant main partner in the past 30 days.

2.2. Procedures

The study utilized an index participant approach to couples’ recruitment (Robles et al., 2019) and recruitment encompassed online and in-person strategies. Online efforts included advertisements on Facebook, other websites, and popular geosocial networking apps. Clicking an ad directed participants to an initial screening survey that assessed preliminary eligibility and gathered contact information. In addition, study staff screened participants in-person at area bars, nightclubs, and other social events. Through June 2019, preliminarily eligible index participants were contacted by phone to complete a study-specific screener. Beginning July 2019, this study-specific screener was converted to an online survey.

Eligible index participants scheduled a baseline appointment at a time their partner could also attend. After scheduling, the index participant received an email containing a link to an at-home survey to complete prior to the in-office visit and a comparable email to forward to their partner. At the baseline appointment, a research assistant reviewed consent information with partners individually and obtained written consent. Partners completed assessments separately. These included a timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview of sexual behavior and substance use in the past 30 days and another survey containing measures not included in the at-home survey. Each participant received $20 for baseline TLFB and computer assisted self-interview assessments. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hunter College of the City University of New York.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics.

Participants reported their age, HIV status, PrEP uptake, sexual identity (gay or bisexual), race/ethnicity (Black, Latino, White, Other/Mixed; we collapsed several groups, e.g., Native American, Asian, into an Other/Mixed category given the small number of participants), income (below $40,000 and $40,000 or above annually), education (less than a four-year degree or above), and relationship length.

Similar to others (e.g., Parsons et al., 2013; Starks et al., 2019a), sexual arrangement was assessed using a single item “Regardless of your sexual agreement, how do you and your partner handle sex outside your relationship.” Response options included “neither of us have sex with others,” “only I have sex with others,” “only he has sex with others,” “we only have sex with others together,” “we both have sex with others separately and together,” and “we both have sex with others separately.” Responses were used to create a couple-level variable derived from both partners’ responses.

2.3.2. Timeline follow-back interview (TLFB).

Following procedures similar to others (e.g., Parsons et al., 2018; Parsons et al., 2013) and initially outlined by Sobell and Sobell (1992), participants were shown a calendar depicting the past 30 days. They reviewed the calendar and personalized it with “anchor dates” or significant events. Subsequently, behavioral data was added.

2.3.3. Condomless anal sex with casual partners.

Each participant’s TLFB responses were used to create a day-level variable where a value of 1 indicated the occurrence of any insertive or receptive CAS with a casual partner. Values of 0 indicated days where no anal sex with casual partners occurred or where anal sex with casual partners occurred but condoms were used. Casual sex partners were defined as any partner excluding the identified main partner who was enrolling into the study with the participant.

2.3.4. Condomless anal sex with main partner.

Each participant’s TLFB responses were used to create a day-level variable where 1 indicated the occurrence of either insertive or receptive anal sex without a condom with their main partner. Values of 0 indicated days where no anal sex was reported between main partners or where anal sex between main partners occurred but condoms were used.

2.3.5. Drug use.

During their TLFB, participants reported days they were under the influence of marijuana, cocaine/crack, ecstasy/MDMA, GHB, ketamine, and crystal methamphetamine. Responses were organized into two dichotomous variables. One indicated whether or not the participant used marijuana on a given day. The other indicated any other illicit drug use (cocaine/crack, ecstasy/MDMA, GHB, ketamine, and crystal methamphetamine).

2.3.6. PrEP adherence.

Research indicates that when taken on a minimum of 4 days out of 7, PrEP may achieve prevention benefits comparable to daily adherence (Anderson et al., 2012). Therefore, participants were categorized as on PrEP and adherent if they indicated having a current PrEP prescription and reported fewer than 13 missed PrEP doses in the prior 30 days.

2.4. Analytic plan

While APIM examined day-level associations, aggregated drug use and sexual behavior data were provided for descriptive purposes. (See Table 1.) The similarity of partners’ behavior was evaluated with intra-class correlations (ICC, two-way mixed effects with absolute agreement) for continuous and count variables and κ for dichotomous variables. Where necessary, skewed variables were submitted to a natural-log transformation before calculating ICC’s.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Partner Similarity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | κ | ||

| Race and Ethnicity | .229** | ||

| White/European | 58 (58) | ||

| Black/African American | 11 (11) | ||

| Latino | 22 (22) | ||

| Other | 9 (9) | ||

| Education | .064 | ||

| Less than a college degree | 70 (70) | ||

| Any college degree | 30 (30) | ||

| Annual Income | .224 | ||

| Less than $40,000 | 50 (50) | ||

| $40,000 or more | 49 (49) | ||

| HIV status and PrEP adherence | .600**† | ||

| HIV positive | 10 (10) | ||

| HIV negative 57% adherent or more | 43 (43) | ||

| HIV negative < 57% adherent or not on PrEP | 57 (57) | ||

| Sexual arrangement | NA | ||

| Monogamous | 8 (8) | ||

| Monogamish | 24 (24) | ||

| Open | 58 (58) | ||

| Discrepant | 10 (10) | ||

| M (SD) | Median (IQR) | ICC | |

| Age†† | 28.62 (6.11) | 27 (25, 29) | −.262 |

| Relationship duration (Months) †† | 32.72 (29.30) | 29 (6, 47.75) | .838** |

| Drug use (total days used in the past 30) | |||

| Marijuana use days†† | 8.47 (11.24) | 2 (0, 18) | .367** |

| Other Illicit Drug use days†† | 2.25 (6.62) | 0 (0, 1) | .719** |

| Condomless anal sex (total days sex occurred in the past 30) | |||

| With Casual Partners†† | 1.68 (2.58) | 0 (0, 3) | .303** |

| With Main Partners†† | 4.65 (5.20) | 3 (1, 6) | .762** |

p< .015;

p ≤.01;

NA = Not Applicable

Serodiscordant couples were excluded from calculation.

ICC’s for skewed continuous and count variables were calculated on natural-log transformed values to correct for deviations from normality

Subsequently, two APIMs were calculated in Mplus (w. 8.2.; Muthén and Muthén, 2018) predicting the day-level odds of CAS with main partners and with casual male partners. In APIM, actor effects express the association between a respondent’s outcome score and their own score on a predictor variable. Partner effects quantify the association between a respondent’s outcome score and their partner’s score on a predictor variable. In a 3-level APIM, Level 1 (day-level) variables vary across days within person. Level 2 (person-level) variables may differ between partners in a couple, but do not vary across days. Finally, Level 3 (couple-level) variables are common to both relationship partners. In this paradigm, it is possible to consider actor and partner effects at both Level 1 (the day-level) and Level 2 (the person-level).

Each model calculated included the actor and partner effects of marijuana and other illicit drug use at Level 1. In addition, the model predicting sex with casual partners controlled for participants’ personal report of CAS between main partners at Level 1. At Level 2, models included actor and partner effects of age, race and ethnicity, as well as HIV status and PrEP. Relationship length was included at Level 3. Models were calculated using Bayesian estimation with two Markov chain Monte Carlo chains having 10,000 iterations. Model fit was evaluated by examination of posterior predictive p-values (PPP), with PPP < .05 indicating misfit.

Effect size was calculated using procedures outlined by Larsen and Merlo (2005). When multi-level models utilize log-link functions and allow a random variance at Level 2, direct exponentiation of Level 2 regression coefficients does not accurately capture relative effect size. The Interval Odds Ratio (IOR) represents the 80% confidence interval for the odds ratio comparing any one randomly selected participant to another from a different Level 2 unit (i.e., a different couple) given a one-point difference on that specific predictor and holding other factors constant. A narrow interval implies the association between the predictor and outcome is relatively consistent across variation in couples.

3. RESULTS

A total of 5931 index participants screened. Of these, 420 (7.1%) were preliminarily eligible. Baseline appointments were completed with 126 participants (63 couples). Of these, 100 participants (50 couples) were eligible after baseline. Table 1 contains demographic data. Participants’ average age was 28.6 (SD=6.1) years. Most identified as White (58%) and had not obtained a 4-year college degree (70%). Approximately half earned at least $40,000 annually. Most (90%) were HIV negative or status unknown (48% of these were on PrEP and indicated they were at least 57% adherent). Average relationship duration was 32.7 (SD=29.3) months. Most couples had a non-monogamous (open or monogamish) sexual arrangement (82%).

Overall, 14 participants reported the use of both marijuana and other illicit drugs on the same day at least once. Across all 3000 reported days (30 days reported by each of the 100 participants), participants reported the combined use of marijuana and other illicit drugs on 108 (3.6%) days; they reported marijuana – but not other illicit drug use – on 739 days (24.6%); and other illicit drug use – but not marijuana use – on 117 days (3.9%).

ICC’s indicated that partners reported similar aggregated or overall amounts of drug use during the TLFB assessment period. In 22 couples (44%), there was at least one day where both partners reported the use of marijuana. Analyzing day-level similarity, or concurrence between partners, utilizes data from both partners in a couple. Therefore, the total number of days reported on is 1500. (Fifty couples provided 30 days of data.) Partners in a couple both reported the use of marijuana on 196 (13.1%) days. One partner in the couple reported marijuana use while the other did not on 455 days (30.4%). In 7 couples (14%), there was at least one day where both partners reported the use of other illicit drugs. Both partners in a couple reported the use of other illicit drugs on 52 days (3.5%). One partner reported other illicit drug use while the other did not on 121 days (8.0%).

Overall, 85 participants reported at least one instance of CAS with their main partner. On average, 92% of anal sex acts with main partners were condomless (SD = 0.24). Across all 3000 reported days, participants reported 469 days on which CAS between main partners occurred. Participants reported the use of marijuana as well as CAS between main partners on 171 of these days (35.5%). The use of other illicit drugs was reported on 89 days that CAS between main partners was also reported (19.0%).

Overall, 58 participants indicated they had CAS with a casual partner at least one time. On average, 73% of anal sex acts with casual partners were condomless (SD = 0.38). Across all 3000 reported days, participants reported a total of 142 days on which CAS with a casual partner occurred. Participants reported the use of marijuana as well as CAS with casual partners on 50 of these days (35.2%). The use of other illicit drugs was reported on 23 days (16.2%) that CAS with casual partners was also reported. Finally, participants reported CAS occurred between main partners on 62 (43.7%) of the days where they also reported CAS with casual partners.

3.1. Condomless anal sex between main partners

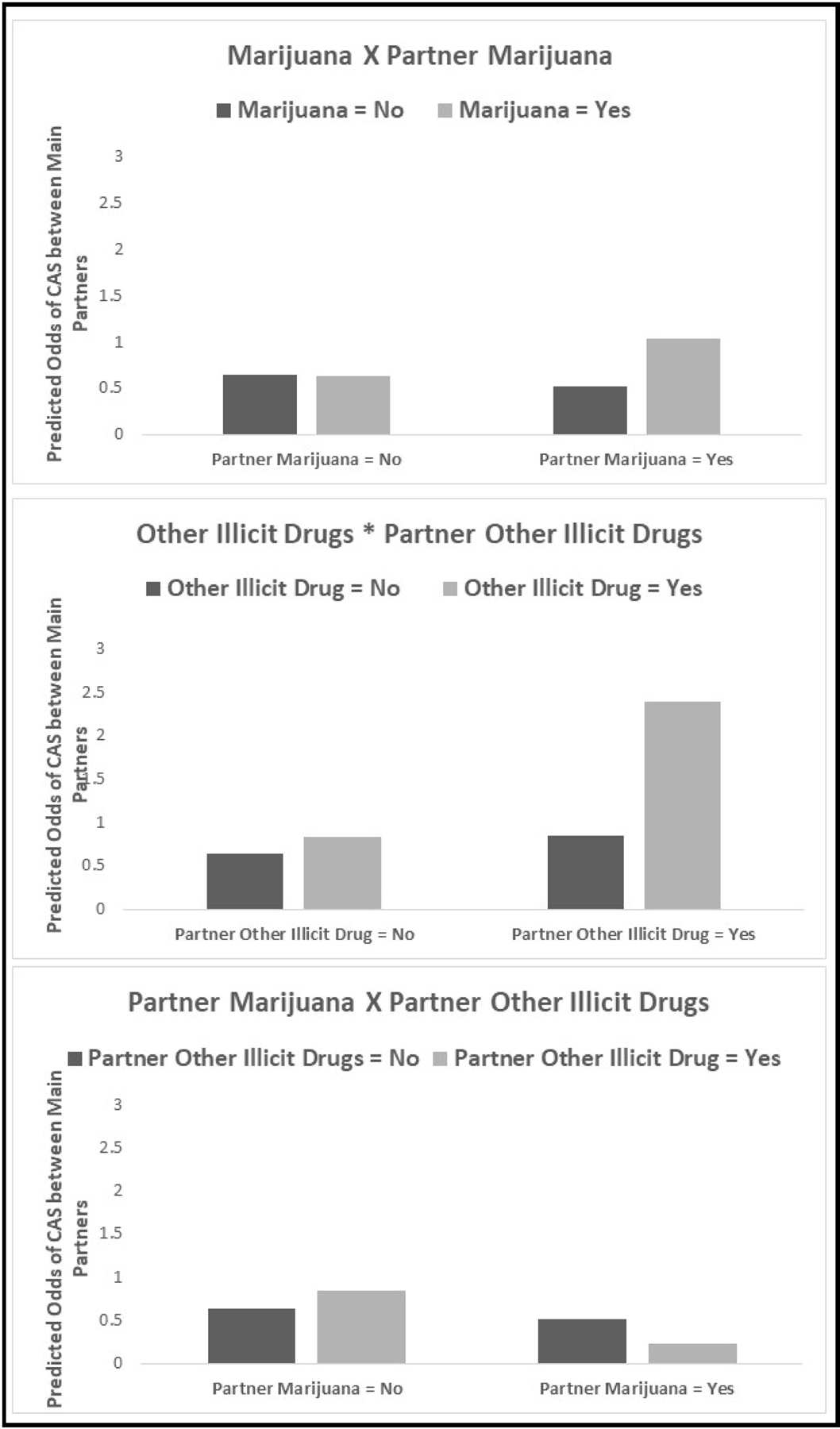

Model fit for the APIM predicting CAS between main partners was adequate (PPP=0.487). There was evidence of significant interactions among drug use variables at Level 1. Three of the six interactions tested were significant. (See Figure 2 and Table 2.)

Figure 2.

Significant intra-individual and inter-individual interactions predicting condomless anal sex with main partners

Table 2.

Results of APIM model predicting condomless sex between main partners

| Condomless Anal Sex between Main Partners | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | |

| DAY LEVEL | |||

| Marijuana | |||

| Actor | −0.01 | (−0.27, 0.25) | 0.99 |

| Partner | −0.22 | (−0.49, 0.05) | 0.80 |

| Other Illicit Drugs | |||

| Actor | 0.27 | (−0.30, 0.83) | 1.31 |

| Partner | 0.28 | (−0.27, 0.81) | 1.32 |

| Interactions | |||

| Marijuana* Other Illicit Drugs | 0.03 | (−0.66, 0.71) | 1.03 |

| Marijuana*Partner Marijuana | 0.71* | (0.31, 1.11) | 2.02 |

| Marijuana*Partner Other Illicit Drugs | 0.33 | (−0.31, 0.94) | 1.39 |

| Other Illicit Drugs*Partner Marijuana | 0.35 | (−0.30, 1.01) | 1.41 |

| Other Illicit Drugs*Partner Other Illicit Drugs | 0.77* | (0.04, 1.52) | 2.17 |

| Partner Marijuana*Partner Other Illicit Drugs | −1.07* | (−1.87, −0.31) | 0.34 |

| PERSON LEVEL | Interval Odds Ratio | ||

| Ln(Age) | |||

| Actor | 0.04 | (−0.47, 0.62) | [0.67, 1.61] |

| Partner | −0.36 | (−0.85, 0.18) | [0.45, 1.08] |

| Race and ethnicity (referent = non-White) | |||

| Actor | 0.31 | (−0.05, 0.69) | [0.88, 2.12] |

| Partner | 0.21 | (−0.16, 0.58) | [0.79, 1.90] |

| HIV status and PrEP uptake (referent = HIV negative & not on or adherent to PrEP) | |||

| HIV positive | |||

| Actor | −0.08 | (−0.76, 0.58) | [0.60, 1.43] |

| Partner | 0.03 | (−0.64, 0.67) | [0.66, 1.59] |

| PrEP Adherent 57% | |||

| Actor | 0.13 | (−0.27, 0.47) | [0.73, 1.75] |

| Partner | 0.02 | (−0.38, 0.38) | [0.64, 1.58] |

| COUPLE LEVEL | |||

| Ln(Relationship Length) | −0.05 | (−0.28, 0.18) | † |

NOTE:

p < .05

Interval Odds Ratios for Level 3 predictors are not available at this time.

Two interactions quantified the extent to which use of a drug by one’s partner contextualized the association between respondents’ use of that drug and CAS with their main partner. Specifically, there was a significant interaction between the actor and partner effects of marijuana use (B=0.71; 95%CI: 0.31 to 1.11; OR=2.02). On days when partners did not use marijuana, participants own use (the actor effect) was not significantly associated with the odds of CAS between main partners; however, the actor effect of marijuana was associated with increased odds of CAS between main partners on days when partners also used it (B=0.69; 95%CI: 0.37 to 1.00; OR=1.99). There was also a significant interaction between the actor and partner effects of other illicit drug use (B=0.77; 95%CI: 0.04 to 1.52; OR=2.17). The use of other illicit drugs was not significantly associated with CAS between main partners on days when partners did not use them. On days where partners also reported other illicit drug use, the actor effect was significant (B=1.04; 95%CI: 0.37 to 1.74; OR=2.83).

The remaining interaction term addressed combined marijuana and other illicit drug use by a partner. The interaction between partner marijuana and partner other illicit drug use was statistically significant (B= −1.07; 95%CI: −1.87 to −0.31; OR=0.34). On days where partners did not use marijuana, the association between partners’ other illicit drug use and CAS between main partners was non-significant but positive in direction. On days where partners used marijuana, the association between a partners’ use of other illicit drugs and the odds of CAS between main partners was significant and negative in direction (B= −0.81; 95%CI: −1.58 to −0.04; OR=0.44) indicating that the combined use of marijuana and other illicit drugs by a partner was associated with significant decreases in the likelihood of CAS between main partners. At Levels 2 and 3, demographic covariates and relationship length were non-significant.

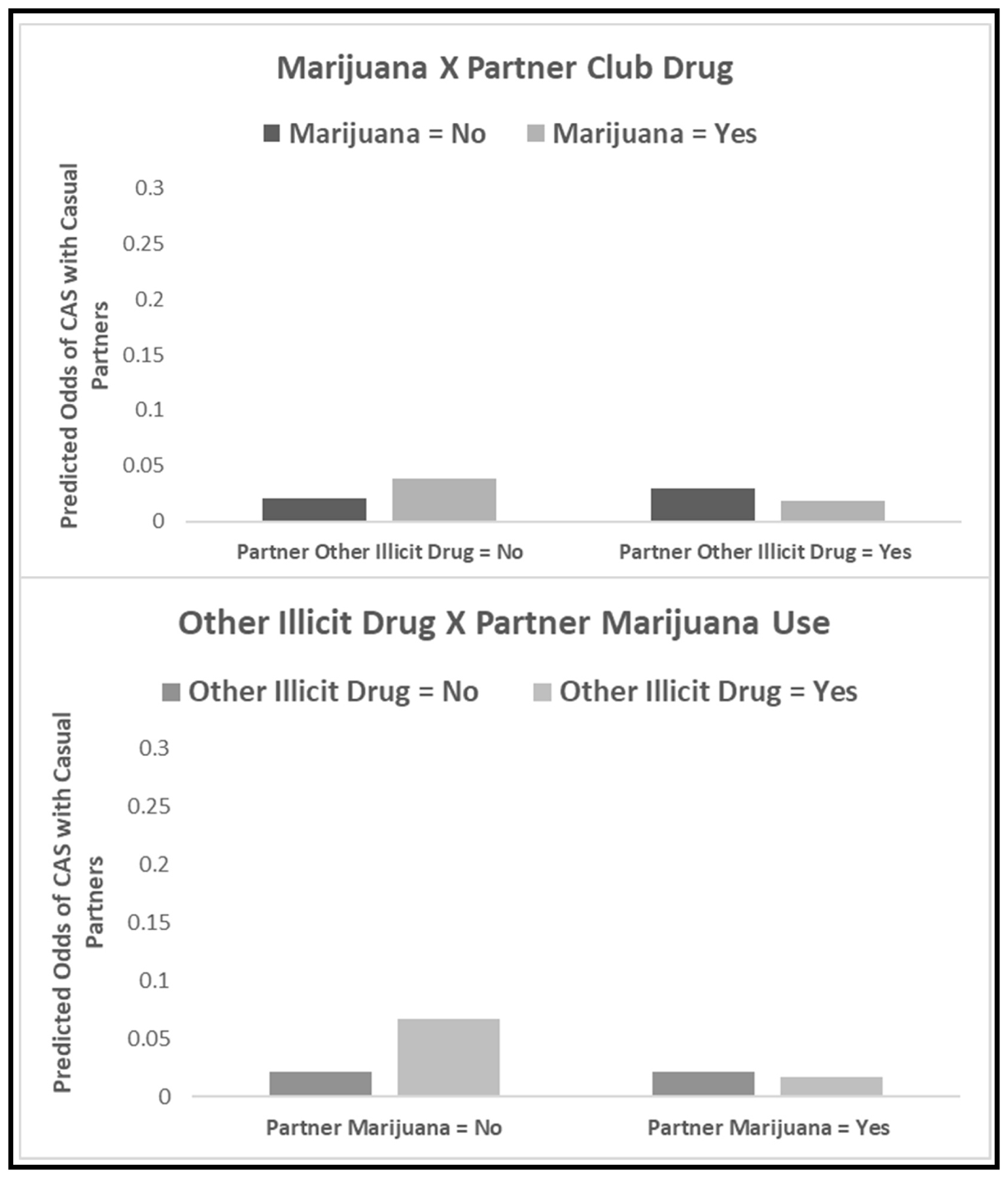

3.2. Condomless sex with casual partners

Model fit was adequate (PPP=0.472) for the APIM predicting CAS with casual partners. There was evidence of significant interactions among drug use variables at Level 1. Two of the six terms tested were significant. (See Figure 3 and Table 3.)

Figure 3.

Significant interactions between actor and partner drug use in the prediction of condomless anal sex with main partners

Table 3.

APIM models predicting condomless sex with casual partners

| Condomless Anal Sex with a Casual Partner | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | |

| DAY LEVEL | |||

| Marijuana | |||

| Actor | 0.59* | (0.24, 0.95) | 1.80 |

| Partner | 0.02 | (−0.42, 0.42) | 1.02 |

| Other Illicit Drugs | |||

| Actor | 1.15* | (0.47, 1.88) | 3.15 |

| Partner | 0.35 | (−0.46, 1.11) | 1.42 |

| Main Partner Sex | 0.91* | (0.69, 1.14) | 2.49 |

| Interactions | |||

| Marijuana* Other Illicit Drugs | −0.41 | (−1.43, 0.58) | 0.67 |

| Marijuana*Partner Marijuana | −0.13 | (−0.67, 0.46) | 0.88 |

| Marijuana*Partner Other Illicit Drugs | −1.06* | (−2.17, −0.07) | 0.35 |

| Other Illicit Drugs*Partner Marijuana | −1.37* | (−2.79, −0.27) | 0.26 |

| Other Illicit Drugs*Partner Other Illicit Drugs | 0.61 | (−0.38, 1.72) | 1.83 |

| Partner Marijuana*Partner Other Illicit Drugs | −0.07 | (−1.32, 0.93) | 0.93 |

| PERSON LEVEL | Interval Odds Ratio | ||

| Ln(Age) | |||

| Actor | −0.70* | (−1.30, −0.09) | [0.26, 0.95] |

| Partner | 0.14 | (−0.50, 0.79) | [0.60, 2.21] |

| Race and ethnicity (referent = non-White) | |||

| Actor | 0.08 | (−0.28, 0.49) | [0.57, 2.08] |

| Partner | 0.63* | (0.23, 1.05) | [0.98, 3.59] |

| HIV status and PrEP uptake (referent = HIV negative & not on or adherent to PrEP) | |||

| HIV positive | |||

| Actor | 0.55 | (−0.17, 1.25) | [0.91, 3.34] |

| Partner | 0.50 | (−0.27, 1.26) | [0.86, 3.15] |

| PrEP Adherent 57% | |||

| Actor | 0.13 | (−0.28, 0.51) | [0.60, 2.19] |

| Partner | 0.62* | (0.21, 1.04) | [0.97, 3.56] |

| COUPLE LEVEL | |||

| Relationship Length (months) | 0.13 | (−0.07, 0.36) | † |

NOTE:

p < .05

Interval Odds Ratios for Level 3 predictors are not available at this time.

Both interactions quantified the extent to which the association between respondents’ use of a drug and their report of CAS with casual partners on a given day was diminished by a partner’s use of a different drug. Specifically, there was a significant interaction between the actor effect of marijuana use and the partner effect of other illicit drug use (B= −1.06; 95%CI: −2.17 to −0.07; OR=0.35). On days where partners did not report other illicit drug use, the actor effect of marijuana was statistically significant and positive (B= 0.59; 95%CI: 0.24 to 0.95; OR=1.80); however, the association was non-significant on days where partners reported other illicit drug use (B= −0.47; 95%CI: −1.57 to 0.53; OR=0.63). There was a complementary significant interaction between the actor effect of other illicit drug use and the partner effect of marijuana use (B= −1.37; 95%CI: −2.79 to −0.27; OR=0.26). On days where partners did not report marijuana use, the actor effect of other illicit drugs was statistically significant and positive (B= 1.15; 95%CI: 0.47 to 1.88; OR=3.15); however, the association was non-significant on days where partners reported marijuana use (B= −0.22; 95%CI: −1.70 to 0.96; OR=0.80). In addition, main partner CAS was positively associated with CAS with casual partners (B= 0.91; 95%CI: 0.69 to 1.14; OR=2.49).

A number of Level 2 demographic characteristics were significantly associated with CAS with casual partners. Older participants were less likely to report CAS with casual partners. Respondents whose partners identified as majority White were significantly more likely to report CAS with casual partners than those whose partners identified as a racial or ethnic minority. Men whose partners were on PrEP and adherent were significantly more likely to report CAS with casual partners compared to HIV negative men not on (or not adherent to) PrEP.

4. DISCUSSION

This study represents the first extension of the APIM to examine day-level associations between drug use and sexual behavior in data from SMM couples. A number of salient findings emerged. First, the use of similar drugs by main partners amplified associations between drug use and CAS between them (e.g., the association between marijuana and CAS between main partners was strongest on days where both partners used marijuana.) Second, CAS with casual partners was more likely on days where CAS with main partners was also reported. Finally, controlling for CAS between main partners, participants’ report of both marijuana and other illicit drugs significantly increased the likelihood of CAS with casual partners; however, these associations were non-significant on days when main partners used different drugs (e.g., on days where their main partners used marijuana, respondents’ use of other illicit drugs was not significantly associated with CAS with casual partners.)

Findings were consistent with research on associations between other illicit drug use and CAS between main partners and add to limited research on marijuana use (Gamarel et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2016). While Mitchell et al. (2016) observed that SMM who used marijuana in conjunction with sex with both casual and main partners reported higher odds of CAS with both partner types, our findings indicated that such associations are present for both marijuana and illicit drugs at the day-level. Previous research has indicated that SMM are less likely to engage in CAS with their main partners when they use illicit drugs and their partners do not (Gamarel et al., 2015). Our findings go further to suggest that similarity in main partners’ drug use amplifies associations with CAS between them. These findings conformed to hypotheses informed by Interdependence Theory (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). These associations between drug use and CAS between main partners may arise because partners engaged in joint activities involving the use of drugs and the opportunity to have sex together on a specific day.

Contrary to initial hypotheses, participants were more likely to report CAS with casual partners on days they reported CAS with their main partner. This unanticipated finding points to the need for more research eamining associations among sexual agreements, sexual behavior, and dyadic functioning in this population. Such investigations might reveal that our novel finding can be explained if Interdependence Theory is expanded to incorporate factors unique to the regulation of sexual behavior in SMM partnerships. For example, it is plausible that the co-occurrence of CAS with main and casual partners emerges from shared values regarding sexual activity or joint engagement in sex. “Monogamish” sexual arrangements, in which sex with casual partners is permitted exclusively when both main partners are present, have been routinely observed in samples of SMM (e.g., Starks et al., 2020a; Starks et al., 2019c). In the present sample, at least some sex acts with casual partners may have happened in the context of group sex that included both main partners and one or more casual partners. Twelve couples had monogamish arrangements and while couples in open arrangements were permitted to have sex with casual partners individually, they were not restricted from doing so together.

While the current study cannot elucidate mechanisms leading to the correspondence between main and casual partner CAS, the day-level co-occurrence of these behaviors highlights the potential for main partner HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) transmission and the role of drug use in catalyzing it. If CAS with casual partners is occurring in the context of events that also include CAS between main partners, both main partners may be exposed. Even if CAS with casual partners occurs independently, the same-day occurrence of CAS between main partners may present opportunities for intra-partner transmission before either main partner is aware of exposure.

In at least some respects, observed associations between drug use and CAS with casual partners replicated findings in aggregated data (Starks et al., 2020a). The magnitude of these associations between drug use variables and CAS with casual partners was comparable to those observed in aggregated data for both marijuana and other illicit drugs (Starks et al., 2020a) and larger than day-level associations previously observed between marijuana use and CAS (Rendina et al., 2015). These associations between drug use and CAS with casual partners were diminished on days where partners used different drugs. It is plausible that discrepant drug use indicates that main partners are using in social settings where drug use is expected but where chances of sexual behavior with casual partners are relatively low. There is evidence that the association between substance use and sexual risk with casual partners is driven in part by the social and environmental context in which SMM use drugs (Carpiano et al., 2011; Carrico et al., 2016). Whatever the cause, the fact that partners’ use contextualizes the association between respondents’ drug use and CAS with casual partners may explain at least some of the variability present across existing studies.

These findings provide substantial rationale for dyadic intervention. The day-level co-occurrence of CAS with main and casual partners implies that partner communication is essential to mitigate HIV and other STI transmission risk between main partners. Interventions such as couples HIV testing and counseling (Stephenson et al., 2017a; Sullivan et al., 2014), Stronger Together (Stephenson et al., 2017b); 2gether (Newcomb et al., 2017), We Test (Starks et al., 2019a; Starks et al., 2019b), We Prevent (Gamarel et al., 2019), and the Couples Health Project (Starks et al., 2020b), which foster communication about HIV prevention and related sexual health goals may prepare couples to discuss the immediate occurrence of risk. These results also indicate that sexual health for partnered SMM is maximized by shared reductions in drug use, supporting the potential utility of interventions that have an integrated focus on drug use and sexual health (e.g., Newcomb et al., 2017; Starks et al., 2019a; Starks et al., 2018).

Several limitations are noteworthy. Day-level analyses do not provide evidence of causal associations. Data collection did not preserve the temporal order of acts within a given day. It is not possible to determine from these data whether sex with a casual partner preceded or followed sex with a main partner, for example. The generalizability of these findings is also restricted by eligibility criteria. Couples lived in an urban setting. Each included at least one SMM with recent drug use and at least one who was 18–29. Moreover, all couples had to be in a relationship of three months or more and be non-monogamous or have a sero-discordant HIV status in order to participate. Eligibility criteria reflected a focus on partnered SMM at high risk for HIV infection. Additional research is needed to evaluate whether findings apply to SMM couples at lower risk for HIV.

Despite these limitations, this is the first paper to extend the APIM to examine day-level associations between drug use and sexual behavior among SMM. SMM were more likely to have CAS with casual partners on days they also had CAS with main partners – maximizing shared exposure. Day-level similarities in main partner drug use amplified associations between drug use and CAS between main partners. Meanwhile, on days where partners used different drugs, the association between drug use and CAS with casual partners was attenuated. Overall, findings highlighted the interdependent nature of sexual health outcomes, and provide a glimpse into the complexity of partner influences on drug use and sexual behavior that occurs on a daily basis.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Similarity amplified associations between drug use and CAS between main partners.

CAS with casual partners was more likely on days CAS with main partners occurred

Drug use predicted CAS with casual partners when partners did not use.

Differences diminished associations between drug use and CAS with casual partners

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the Couples Health Project Team, particularly Jeffrey T. Parsons, Christine Cowles, Mark Pawson, Nahuel Smith, Ruben Jimenez, and Scott Jones. We also thank the staff, recruiters, interns at the PRIDE Health Research Consortium and our participants who volunteered their time.

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34 DA043422; PI Starks).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST: Dr. Starks was the Primary Investigator of the award funding this research (R34 DA043422). The authors have no other conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, McMahan V, Bushman LR, Casapía M, Montoya-Herrera O, Veloso VG, Mayer KH, Chariyalertsak S, Schechter M, Bekker L, Kallás EG, & Grant RM 2012. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 4(151), 151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone MR, Cook SH, & Wilson P, 2013. Substance use and sexual risk behavior in HIV-positive men who have sex with men: an episode-level analysis. AIDS Behav 17(5), 883–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM, Kelly BC, Easterbrook A, & Parsons JT, 2011. Community and drug use among gay men: The role of neighborhoods and networks. J Health Soc Behav 52(1), 74–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Zepf R, Meanley S, Batchelder A, & Stall R, 2016. Critical review: When the party is over: A systematic review of behavioral interventions for substance-using men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999) 73(3), 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. HIV surveillance report, 2018 (Updated). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- Gamarel KE, Darbes LA, Hightow-Weidman L, Sullivan P, & Stephenson R, 2019. The development and testing of a relationship skills intervention to improve HIV prevention uptake among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and their primary partners (We Prevent): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 8(1), e10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Woolf-King SE, Carrico AW, Neilands TB, & Johnson MO, 2015. Stimulant use patterns and HIV transmission risk among HIV-serodiscordant male couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 68(2), 147–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, Lama JR, Sanchez J, Grinsztejn B, Koblin BA, Mayer KH, & Buchbinder SP, 2012. What drives the US and Peruvian HIV epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PLoS ONE 7(11), e50522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Levy MD, & Solomon TM, 2016. Temporal relations between methamphetamine use and HIV seroconversion in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. J Health Psychol 21(1), 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL, 2006. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K, & Merlo J 2005. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: Integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Epidemiol Rev 161(1), 81–88. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis AD, Joseph H, Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Belcher L, & Purcell DW, 2014. Anal intercourse without condoms among HIV-positive men who have sex with men recruited from a sexual networking web site, United States. Sex Transm Dis 41(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty-Caplan D, Jantz I, & Swartz J, 2014. MSM and drug use: A latent class analysis of drug use and related sexual risk behaviors. AIDS Behav 18(7), 1339–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland SE, Driscoll MA, Cranston K, Isenberg D, VanDerwarker R, & Mayer KH, 2011. Sex parties among urban MSM: an emerging culture and HIV risk environment. AIDS Behav 15(2), 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JW, Champeau D, & Harvey SM, 2013. Actor-partner effects of demographic and relationship factors associated with HIV risk within gay male couples. Arch Sex Behav 42(7), 1337–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JW, Pan Y, & Feaster D, 2016. Actor-Partner effects of male couples substance use with sex and engagement in condomless anal sex. AIDS Behav 20(12), 2904–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan E, Skaathun B, Michaels S, Young L, Khanna A, Friedman SR, Davis B, Pitrak D, & Schneider J, 2016. Marijuana use as a sex-drug is associated with HIV risk among Black MSM and their network. AIDS Behav 20(3), 600–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2018. Mplus users guide and Mplus version 8.2. http://www.statmodel.com/index.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Macapagal KR, Feinstein BA, Bettin E, Swann G, & Whitton SW, 2017. Integrating HIV prevention and relationship education for young same-sex male couples: A pilot trial for the 2GETHER intervention. AIDS Behav 21(8), 2464–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalone DW, Bimbi DS, Holder CA, Golub SA, & Parsons JT, 2010. Consistency and change in club drug use by sexual minority men in New York City, 2002 to 2007. Am J Public Health 100(10), 1892–1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, John SA, Millar BM, & Starks TJ, 2018. Testing the efficacy of combined Motivational Interviewing and Cognitive Behavioral Skills Training to reduce methamphetamine use and improve HIV medication adherence among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 22(8), 2674–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, & Golub SA, 2013. Predictors of day-level sexual risk for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 17(4), 1465–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines HA, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Shoptaw S, Landovitz RJ, Javanbakht M, Ostrow DG, Stall RD, & Plankey M, 2014. Sexual risk trajectories among MSM in the United States: implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 65(5), 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Moody RL, Ventuneac A, Grov C, & Parsons JT, 2015. Aggregate and event-level associations between substance use and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: Comparing retrospective and prospective data. Drug Alcohol Depend 154, 199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles G, Dellucci TV, Stratton MJ Jr, Jimenez RH, & Starks TJ, 2019. The utility of index case recruitment for establishing couples’ eligibility: An examination of consistency in reporting the drug use of a primary partner among sexual minority male couples. Couple Family Psychol 8(4), 221–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, & Van Lange PA, 2003. Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annu Rev Psychol 54(1), 351–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Yovetich NA, & Verette J, 1996. An interdependence analysis of accommodation processes, in: Fletcher GJO, Fitness J (Eds.), Knowledge structures in close relationships: A social psychological approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahway, N.J., pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB, 1992. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption, in: Litten RZ, Allen JP (Eds.), Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Dellucci TV, Gupta S, Robles G, Stephenson R, Sullivan P, & Parsons JT, 2019a. A pilot randomized trial of intervention components addressing drug use in Couples HIV Testing and Counseling (CHTC) with male couples. AIDS Behav, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Feldstein Ewing SW, Lovejoy T, Gurung S, Cain D, Fan CA, Naar-King S, & Parsons JT, 2019b. Multi-phase effectiveness trial of an adolescent male couples-based HIV testing intervention. JMIR Res Protoc pre-print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Grov C, & Parsons JT, 2013. Sexual compulsivity and interpersonal functioning: Sexual relationship quality and sexual health in gay relationships. Health Psychol 32(10), 1047–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Jones SS, Kyre K, Robles G, Cain D, Jimenez R, Stephenson R, & Sullivan PS, 2020a. Testing the drug use and condomless anal sex link among sexual minority men: The predictive utility of marijuana and interactions with relationship status. Drug Alcohol Depend 216, 108318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Millar BM, Doyle KM, Bertone P, Ohadi J, & Parsons JT, 2018. Motivational interviewing with couples: A theoretical framework for clinical practice illustrated in substance use and HIV prevention intervention with gay male couples. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 5(4), 490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, & Parsons JT, 2014. Adult attachment among partnered gay men: Patterns and associations with sexual relationship quality. Arch Sex Behav 43(1), 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Robles G, Bosco SC, Dellucci TV, Grov C, & Parsons JT 2019c. The prevalence and correlates of sexual arrangements in a national cohort of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in the United States. Arch Sex Behav, 48(1), 369–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Robles G, Bosco SC, Doyle KM, & Dellucci TV, 2019d. Relationship functioning and substance use in same-sex male couples. Drug Alcohol Depend 1;201:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Robles G, Doyle KM, Pawson M, Bertone PB, Millar BM, & Ingersoll KS, 2020b. Motivational Interviewing with male couples to reduce substance use and HIV risk: Manifestations of partner discord and strategies for facilitating dyadic functioning. Psychotherapy 57(1), 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Freeland R, Sullivan SP, Riley E, Johnson BA, Mitchell J, McFarland D, & Sullivan PS, 2017a. Home-based HIV testing and counseling for male couples (Project Nexus): A protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 6(5), e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Suarez NA, Garofalo R, Hidalgo MA, Hoehnle S, Thai J, Mimiaga MJ, Brown EC, Bratcher A, Wimbly T, Sullivan P 2017b. Project stronger together: Protocol to test a dyadic intervention to improve engagement in HIV care among sero-discordant male couples in three US cities. JMIR Res Protoc 6(8), e170–e170. doi: 10.2196/resprot.7884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, & Sanchez TH, 2009. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS 23(9), 1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, White D, Rosenberg ES, Barnes J, Jones J, Dasgupta S, O’Hara B, Scales L, Salazar LF, Wingood G, DiClemente R, Wall KM, Hoff CC, Gratzer B, Allen S, & Stephenson R, 2014. Safety and acceptability of couples HIV testing and counseling for US men who have sex with men: A randomized prevention study. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 13(2), 135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosburgh HW, Mansergh G, Sullivan PS, & Purcell DW, 2012. A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 16(6), 1394–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]