Abstract

Writing recommendation letters on behalf of students and other early-career researchers is an important mentoring task within academia. An effective recommendation letter describes key candidate qualities such as academic achievements, extracurricular activities, outstanding personality traits, participation in and dedication to a particular discipline, and the mentor’s confidence in the candidate’s abilities. In this Words of Advice, we provide guidance to researchers on composing constructive and supportive recommendation letters, including tips for structuring and providing specific and effective examples, while maintaining a balance in language and avoiding potential biases.

Keywords: Mentoring, Recommendation Letter, Graduate Education, Faculty Development, Research Culture

Introduction

A letter of recommendation or a reference letter is a statement of support for a student or an early-career researcher (ECR; a non-tenured scientist who may be a research trainee, postdoctoral fellow, laboratory technician, or junior faculty colleague) who is a candidate for future employment, promotion, education, or funding opportunities. Letters of recommendation are commonly requested at different stages of an academic research career and sometimes for transitioning to a non-academic career. Candidates need to request letters early on and prepare relevant information for the individual who is approached for recommendation [1,2]. Writing recommendation letters in support of ECRs for career development opportunities is an important task undertaken frequently by academics. ECRs can also serve as mentors during their training period and may be asked to write letters for their mentees. This offers the ECRs an excellent opportunity to gain experience in drafting these important documents, but may present a particular challenge for individuals with little experience. In general, a letter of recommendation should present a well-documented evaluation and provide sufficient evidence and information about an individual to assist a person or a selection committee in making their decision on an application [1]. Specifically, the letter should address the purpose for which it is written (which is generally to provide support of the candidate’s application and recommendation for the opportunity) and describe key candidate qualities, the significance of the work performed, the candidate’s other accomplishments and the mentor’s confidence in the candidate’s abilities. It should be written in clear and unbiased language. While a poorly written letter may not result in loss of the opportunity for the candidate, a well-written one can help an application stand out from the others, thus well-enhancing the candidate’s chances for the opportunity.

Letter readers at review, funding, admissions, hiring and promotion committees need to examine the letter objectively with a keenness for information on the quality of the candidate’s work and perspective on their scientific character [6]. However well-intentioned, letters can fall short of providing a positive, effective, and supportive document [1,3–5]. To prevent this, it is important to make every letter personal; thus, writing letters requires time and careful consideration. This article draws from our collective experiences as ECRs and the literature to highlight best practices and key elements for those asked to provide recommendation letters for their colleagues, students, or researchers who have studied or trained in their classroom or research laboratory. We hope that these guidelines will be helpful for letter writers to provide an overall picture of the candidate’s capabilities, potential and professional promise.

Decide on whether to write the letter

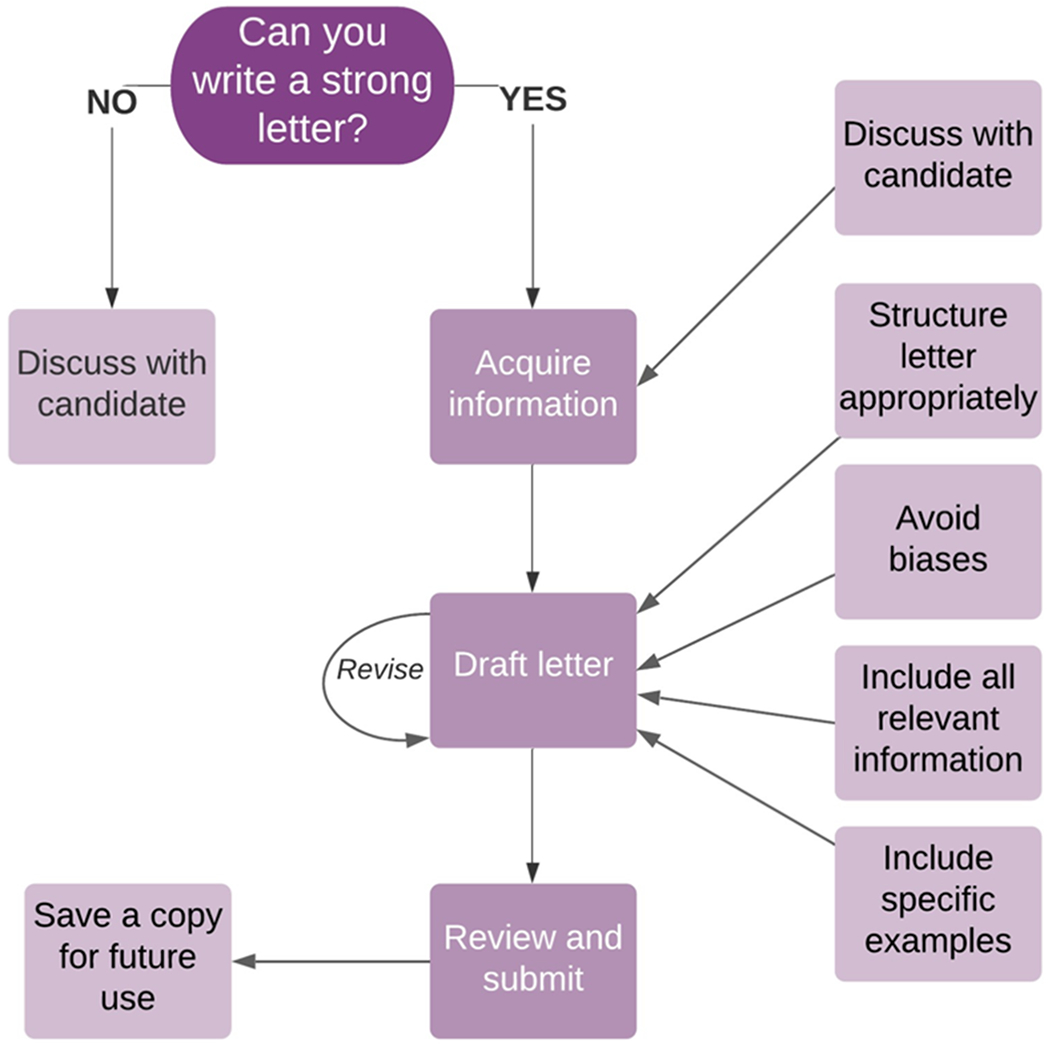

Before you start, it is important to evaluate your relationship with the candidate and ability to assess their skills and abilities honestly. Consider how well and in what context you know the person, as well as whether you can be supportive of their application [7]. Examine the description of the opportunity for which the letter is being requested (Figure 1). Often you will receive a request by a student or a researcher whom you know very well and have interacted with in different settings – in and out of the classroom, your laboratory or that of a colleague, or within your department – and whose performance you find to be consistently satisfactory or excellent. Sometimes a mentee may request a recommendation letter when still employed or working with you, their research advisor. This can come as an unpleasant surprise if you are unaware that the trainee was seeking other opportunities (for instance, if they haven’t been employed with you for long, or have just embarked on a new project). While the mentee should be transparent about their goals and searching for opportunities, you should as a mentor offer to provide the letter for your mentee (see Table 1).

Figure 1. The process of writing recommendation letters.

First, it is important to establish whether you are equipped to write a strong letter of support. If not, it is best to have a candid conversation with the applicant and discuss alternative options or opportunities. If you are in a position to write a strong letter of support, first acquire information regarding the application and the candidate, draft a letter in advance (see Box 1) and submit the letter on time. When drafting the letter, incorporate specific examples, avoid biases, and discuss the letter with the candidate (see Tables 1–2 for specific examples). After submission, store a digital copy for potential future use for the same candidate.

Table 1.

Key do’s and don’ts when being asked to write a letter of recommendation

| Theme | Do | Do Not |

|---|---|---|

| Writing a letter in place of the candidate’s research advisor | A personal situation that might require discussion would be when the candidate is unable to ask their advisor for a letter of recommendation due to a bad relationship. If you, as the letter writer, know about this situation, you might want to mention in the letter that “there was a personality conflict but it does not reflect on the ability of the candidate to do the job.” | Do not write anything that is not true, do not stretch the facts. |

| Co-signing recommendation letter | Sometimes, a lab member or non-faculty ECR will have had more direct and notable mentoring experience with the candidate. Thus, the non-faculty mentor may be involved in writing the letter and included as a co-signed referee. Do suggest a direct mentor as a co-signing referee, if relevant. | Do not take credit for a letter you did not write on your own. Do not leave out the direct mentor if their insight can help to support the candidate. |

| Candidate waiver to read the letter | Be sure to clarify that it is up to the reference provider to decide on a waiver. Candidates should check if this requirement holds before they ask a mentor for a letter. |

Do not avoid discussions about the recommendation letter or a waiver with the candidate. |

| Candidate requesting a letter while still employed | Do provide the letter to a candidate requesting a reference while they still work in your lab and assure them of your good intentions. Do have an open and honest conversation with your mentee about why they are applying for another job. |

Do not let your personal feelings come across, impact the writing of the letter or your relationship with the candidate when making a recommendation under these circumstances. Do not refuse a candidate a letter if requested before leaving a lab/position. |

| Candidate drafting the letter | Candidates: if drafting a letter for the first time, study examples when possible and remember to use specific examples that pertain to your relationship with the mentor. Make sure to give the official letter writer a draft far in advance to permit for their editing and timely submission. |

As a candidate, do not undersell yourself. |

Other requests may be made by a candidate who has made no impression on you, or only a negative one. In this case, consider the candidate’s potential and future goals, and be fair in your evaluation. Sending a negative letter or a generic positive letter for individuals you barely know is not helpful to the selection committee and can backfire for the candidate. It can also, in some instances, backfire for you if a colleague accepts a candidate based on your generic positive letter when you did not necessarily fully support that individual. For instance, letter writers sometimes stretch the truth to make a candidate sound better than they really are, thinking it is helpful. If you do not know the applicant well enough or feel that you cannot be supportive, you are not in a strong position to write the recommendation letter and should decline the request, being open about why you are declining to write the letter. Also, be selective about writing on behalf of colleagues who may be in one’s field but whose work is not well known to you. If you have to read the candidate’s curriculum vitae to find out who they are and what they have done, then you may not be qualified to write the letter [8].

When declining a request to provide a letter of support, it is important to explain your reasoning to the candidate and suggest how they might improve their prospects for the future [8]. If the candidate is having a similar problem with other mentors, try to help them identify a more appropriate referee or to explore whether they are making an appropriate application in the first place. Suggest constructive steps to improve relationships with mentors to identify individuals to provide letters in the future. Most importantly, do not let the candidate assume that all opportunities for obtaining supportive letters of recommendation have been permanently lost. Emphasize the candidate’s strengths by asking them to share a favourite paper, assignment, project, or other positive experience that may have taken place outside of your class or lab, to help you identify their strengths. Finally, discuss with the candidate their career goals to help them realize what they need to focus on to become more competitive or steer them in a different career direction. This conversation can mark an important step and become a great interaction and mentoring opportunity for ECRs.

Examine the application requirements

Once you decide to write a recommendation letter, it is important to know what type and level of opportunity the candidate is applying for, as this will determine what should be discussed in the letter (Figure 1). You should carefully read the opportunity posting description and/or ask the candidate to summarize the main requirements and let you know the specific points that they find important to highlight. Pay close attention to the language of the position announcement to fully address the requested information and tailor the letter to the specific needs of the institution, employer, or funding organisation. In some instances, a waiver form or an option indicating whether or not the candidate waives their right to see the recommendation document is provided. If the candidate queries a waiver decision, note that often referees are not allowed to send a letter that is not confidential and that there may be important benefits to maintaining the confidentiality of letters (see Table 1). Specifically, selection committees may view confidential letters as having greater credibility and, value and some letter writers may feel less reserved in their praise of candidates in confidential letters.

Acquire candidate information and discuss letter content

To acquire appropriate information about the candidate, one or more of the following documents may be valuable: a resume or curriculum vitae (CV), a publication or a manuscript, an assignment or exam written for your course, a copy of the application essay or personal statement, a transcript of academic records, a summary of current work, and specific recommendation forms or questionnaires (if provided) [9]. Alternatively, you may ask the candidate to complete a questionnaire asking for necessary information and supporting documents [10]. Examine the candidate’s CV and provide important context to the achievements listed therein. Tailor the letter for the opportunity using these documents as a guide, but do not repeat their contents as the candidate likely submits them separately. Even the most articulate of candidates may find it difficult to describe their qualities in writing [11]. Furthermore, a request may be made by a person who has made a good impression, but for whom you lack significant information to be able to write a strong letter. Thus, even if you know a candidate well, schedule a brief in-person, phone, or virtual meeting with them to 1) fill in gaps in your knowledge about them, 2) understand why they are applying for this particular opportunity, 3) help bring their past accomplishments into sharper focus, and 4) discuss their short- and long-term goals and how their current studies or research activities relate to the opportunity they are applying for and to these goals. Other key information to gather from the applicant includes the date on which the recommendation letter is due, as well as details on how to submit it.

For most applications (for both academic and non-academic opportunities), a letter of recommendation will need to cover both scholarly capabilities and achievements as well as a broader range of personal qualities and experiences beyond the classroom or the laboratory. This includes extracurricular experiences and traits such as creativity, tenacity, and collegiality. If necessary, discuss with the candidate what they would like to see additionally highlighted. As another example of matching a letter with its purpose, a letter for a fellowship application for a specific project should discuss the validity and feasibility of the project, as well as the candidate’s qualifications for fulfilling the project.

Draft the letter early and maintain a copy

Another factor that greatly facilitates letter writing is drafting one as soon as possible after you have taught or trained the candidate, while your impressions are still clear. You might consider encouraging the candidate to make their requests early [11]. These letters can be placed in the candidate’s portfolio and maintained in your own files for future reference. If you are writing a letter in response to a request, start drafting it well in advance and anticipate multiple rounds of revision before submission. Once you have been asked by a candidate to write a letter, that candidate may return frequently, over a number of years, for additional letters. Therefore, maintain a digital copy of the letter for your records and for potential future applications for the same candidate.

Structure your letter

In the opening, you should introduce yourself and the candidate, state your qualifications and explain how you became acquainted with the candidate, as well as the purpose of the letter, and a summary of your recommendation (Table 2). To explain your relationship with the candidate you should fully describe the capacity in which you know them: the type of experience, the period during which you worked with the candidate, and any special assignments or responsibilities that the candidate performed under your guidance. For instance, the letter may start with: “This candidate completed their postdoctoral training under my supervision. I am pleased to be able to provide my strongest support in recommending them for this opportunity.” You may also consider ranking the candidate among similar level candidates within the opening section to give an immediate impression of your thoughts. Depending on the position, ranking the candidate may also be desired by selection committees, and may be requested within the letter. For instance, the recommendation form or instructions may ask you to rank the candidate in the top 1%, 5%, 10%, etc., of applicants. You could write "the student is in the top 5% of undergraduate students I have trained" Or “There are currently x graduate students in our department and I rank this candidate at the top 1%. Their experimental/computational skills are the best I have ever had in my own laboratory.”. Do not forget to include with whom or what group you are comparing the individual. If you have not yet trained many individuals in your own laboratory, include those that you trained previously as a researcher as reference. Having concentrated on the candidate’s individual or unique strengths, you might find it difficult to provide a ranking. This is less of an issue if a candidate is unambiguously among the top 10% that you have mentored but not all who come to you for a letter will fall within that small group. If you wish to offer a comparative perspective, you might more readily be able to do so in more specific areas such as whether the candidate is one of the most articulate, original, clear-thinking, motivated, or intellectually curious.

Table 2.

Key do’s and don’ts when writing a letter of recommendation

| Theme | Do | Do Not |

|---|---|---|

| Promote candidate’s scholarly & non-scholarly outputs | Describe all scholarly outputs in equal weight e.g., preprints, protocols, engineered animal models, computer models, software among others. Describe all scholarly and non-scholarly outputs in equal weight e.g., teaching, service, advocacy efforts. Promote the whole human candidate. |

Do not ignore the candidate’s non-peer reviewed (e.g. preprints, data or code or protocols submitted to repositories) or in-press outputs. |

| Consider the “CNS Syndrome” | Describe the candidate’s preprints and journal publications in terms of their quality and impact on your work and the field. | Do not judge papers by where they are published. It is the quality of the science & the reputation of the researcher, not the journal’s brand, that matters. Avoid paying excessive attention to how many papers the candidate has published in the Cell, Nature, Science family of journals. Refrain from boasting the journals impact factor (JIF) or journal name in the letter as publication in glamour journals does not validate the candidate’s research or guarantee a promising & successful career path. |

| Describe candidate accomplishments | Use agentic (e.g., confident, ambitious, independent) and standout (e.g., best, ideal) adjectives for all candidates, focusing on relevant accomplishments for the opportunity. | Avoid communal words (e.g., kind, affectionate, agreeable) that are more often used for women. Avoid using doubt raising phrases such as “He might be good”, or “she may have potential”, “she has a difficult personality”. |

| Put a positive spin on the perceived negative(s) | Make a criticism sound less damaging. e.g., “When candidate x started at my laboratory, their y skills were poorly developed, but they have worked diligently to improve them and have taken major steps in that direction.” | Do not leave out important, relevant information even if it may be perceived as negative, put a positive spin on it. |

| Describe impact to your lab | Do explain how the candidate’s current and prior work contributes to your laboratories research efforts. | Do not compare the candidate as being as good as person X and Y, but not as good as person Z. This type of information creates subjectivity. |

| Describe impact to your field | Include context for your scientific field and how the candidate’s research fits into and advances the field. | Do not merely describe mastery of techniques. Pay attention to the candidate’s wider comprehension of the field and their impact on their discipline. Avoid too much jargon and field-specific language, as often a broad audience will be reading the letter. |

The body of the recommendation letter should provide specific information about the candidate and address any questions or requirements posed in the selection criteria (see sections above). Some applications may ask for comments on a candidate’s scholarly performance. Refer the reader to the candidate’s CV and/or transcript if necessary but don’t report grades, unless to make an exceptional point (such as they were the only student to earn a top grade in your class). The body of the recommendation letter will contain the majority of the information including specific examples, relevant candidate qualities, and your experiences with the candidate, and therefore the majority of this manuscript focuses on what to include in this section.

The closing paragraph of the letter should briefly 1) summarize your opinions about the candidate, 2) clearly state your recommendation and strong support of the candidate for the opportunity that they are seeking, and 3) offer the recipient of the letter the option to contact you if they need any further information. Make sure to provide your email address and phone number in case the recipient has additional questions. The overall tone of the letter can represent your confidence in the applicant. If opportunity criteria are detailed and the candidate meets these criteria completely, include this information. Do not focus on what you may perceive as a candidate’s negative qualities as such tone may do more harm than intended (Table 2). Finally, be aware of the Forer’s effect, a cognitive error, in which a very general description, that fits almost everyone, is used to describe a person [20]. Such generalizations can be harmful, as they provide the candidate the impression that they received a valuable, positive letter, but for the committee, who receive hundreds of similar letters, this is non-informative and unhelpful to the application.

Describe relevant candidate qualities with specific examples and without overhyping

In discussing a candidate’s qualities and character, proceed in ways similar to those used for intellectual evaluation (Box 1). Information to specifically highlight may include personal characteristics, such as integrity, resilience, poise, confidence, dependability, patience, creativity, enthusiasm, teaching capabilities, problem-solving abilities, ability to manage trainees and to work with colleagues, curriculum development skills, collaboration skills, experience in grant writing, ability to organize events and demonstrate abilities in project management, and ability to troubleshoot (see section “Use ethical principles, positive and inclusive language within the letter” below for tips on using inclusive terminology). The candidate may also have a specific area of knowledge, strengths and experiences worth highlighting such as strong communication skills, expertise in a particular scientific subfield, an undergraduate degree with a double major, relevant work or research experience, coaching, and/or other extracurricular activities. Consider whether the candidate has taught others in the lab, or shown particular motivation and commitment in their work. When writing letters for mentees who are applying for (non-)academic jobs or admission to academic institutions, do not merely emphasize their strengths, achievements and potential, but also try to 1) convey a sense of what makes them a potential fit for that position or funding opportunity, and 2) fill in the gaps. Gaps may include an insufficient description of the candidate’s strengths or research given restrictions on document length. Importantly, to identify these gaps, one must have carefully reviewed both the opportunity posting as well as the application materials (see Box 1, Table 2).

Box 1. Recommendations for Letter Writers.

Consider characteristics that excite & motivate this candidate.

Include qualities that you remember most about the candidate.

Detail their unusual competence, talent, mentorship, teaching or leadership abilities.

Explain the candidate’s disappointments or failures & the way they reacted & overcame.

Discuss if they demonstrated a willingness to take intellectual risks beyond the normal research & classroom experience.

Ensure that you have knowledge of the institution that the candidate is applying for.

Consider what makes you believe this particular opportunity is a good match for this candidate.

Consider how they might fit into the institution’s community & grow from their experience.

Describe their personality & social skills.

Discuss how the candidate interacts with teachers & peers.

Use ethical principles, positive & inclusive language within the letter.

Do not list facts & details, every paper, or discovery of the candidate’s career.

Only mention unusual family or community circumstances after consulting the candidate.

A thoughtful letter from a respective colleague with a sense of perspective can be quite valuable.

Each letter takes time & effort, take it seriously.

When writing letters to nominate colleagues for promotion or awards, place stronger emphasis on their achievements and contributions to a field, or on their track record of teaching, mentorship and service, to aid the judging panel. In addition to describing the candidate as they are right now, you can discuss the development the person has undergone (for specific examples see Table 2).

A letter of recommendation can also explain weaknesses or ambiguities in the candidate’s record. If appropriate – and only after consulting the candidate - you may wish to mention a family illness, financial hardship, or other factors that may have resulted in a setback or specific portion of the candidate’s application perceived weakness (such as in the candidate’s transcript). For example, sometimes there are acceptable circumstances for a gap in a candidate’s publication record—perhaps a medical condition or a family situation kept them out of the lab for a period of time. Importantly, being upfront about why there is a perceived gap or blemish in the application package can strengthen the application. Put a positive spin on the perceived negatives using terms such as “has taken steps to address gaps in knowledge”, “has worked hard to,” and “made great progress in” (see Table 2).

Describe a candidate’s intellectual capabilities in terms that reflect their distinctive or individual strengths and be prepared to support your judgment with field-specific content [12] and concrete examples. These can significantly strengthen a letter and will demonstrate a strong relationship between you and the candidate. Describe what the candidate’s strengths are, moments they have overcome adversity, what is important to them. For example: “candidate x is exceptionally intelligent. They proved to be a very quick study, learning the elements of research design and technique y in record time. Furthermore, their questions are always thoughtful and penetrating.”. Mention the candidate’s diligence, work ethic, and curiosity and do not merely state that “the applicant is strong” without specific examples. Describing improvements to candidate skills over time can help highlight their work ethic, resolve, and achievements over time. However, do not belabor a potential lower starting point.

Provide specific examples for when leadership was demonstrated, but do not include leadership qualities if they have not been demonstrated. For example, describe the candidate’s qualities such as independence, critical thinking, creativity, resilience, ability to design and interpret experiments; ability to identify the next steps and generate interesting questions or ideas, and what you were especially impressed by. Do not generically list the applicant as independent with no support or if this statement would be untrue.

Do not qualify candidate qualities based on a stereotype for specific identities. Quantify the candidate’s abilities, especially with respect to other scientists who have achieved success in the field and who the letter reader might know. Many letter writers rank applicants according to their own measure of what makes a good researcher, graduate trainee, or technician according to a combination of research strengths, leadership skills, writing ability, oral communication, teaching ability, and collegiality. Describe what the role of the candidate was in their project and eventual publication and do not assume letter readers will identify this information on their own (see Table 2). Including a description about roles and responsibilities can help to quantify a candidate’s contribution to the listed work. For example, “The candidate is the first author of the paper, designed, and led the project.”. Even the best mentor can overlook important points, especially since mentors typically have multiple mentees under their supervision. Thus, it can help to ask the candidate what they consider their strengths or traits, and accomplishments of which they are proud.

If you lack sufficient information to answer certain questions about the candidate, it is best to maintain the integrity and credibility of your letter - as the recommending person, you are potentially writing to a colleague and/or someone who will be impacted by your letter; therefore, honesty is key above all. Avoid the misconception that the more superlatives you use, the stronger the letter. Heavy use of generic phrases or clichés is unhelpful. Your letter can only be effective if it contains substantive information about the specific candidate and their qualifications for the opportunity. A recommendation that paints an unrealistic picture of a candidate may be discounted. All information in a letter of recommendation should be, to the best of your knowledge, accurate. Therefore, present the person truthfully but positively. Write strongly and specifically about someone who is truly excellent (explicitly describe how and why they are special). Write a balanced letter without overhyping the candidate as it will not help them.

Be careful about what you leave out of the letter

Beware of what you leave out of the recommendation letter. For most opportunities, there are expectations of what should be included in a letter, and therefore what is not said can be just as important as what is said. Importantly, do not assume all the same information is necessary for every opportunity. In general, you should include the information stated above, covering how you know the candidate, their strengths, specific examples to support your statements, and how the candidate fits well for the opportunity. For example, if you don’t mention a candidate’s leadership skills or their ability to work well with others, the letter reader may wonder why, if the opportunity requires these skills. Always remember that opportunities are sought by many individuals, so evaluators may look for any reason to disregard an application, such as a letter not following instructions or discussing the appropriate material. Also promote the candidate by discussing all of their scholarly and non-scholarly efforts, including non-peer reviewed research outputs such as preprints, academic and non-academic service, and advocacy work which are among their broader impact and all indicative of valuable leadership qualities for both academic and non-academic environments (Table 2).

Provide an even-handed judgment of scholarly impact, be fair and describe accomplishments fairly by writing a balanced letter about the candidate’s attributes that is thoughtful and personal (see Table 2). Submitting a generic, hastily written recommendation letter is not helpful and can backfire for both the candidate and the letter writer as you will often leave out important information for the specific opportunity; thus, allow for sufficient time and effort on each candidate/application.

Making the letter memorable by adding content that the reader will remember, such as an unusual anecdote, or use of a unique term to describe the candidate. This will help the application stand out from all the others. Tailor the letter to the candidate, including as much unique, relevant information as possible and avoid including personal information unless the candidate gives consent. Provide meaningful examples of achievements and provide stories or anecdotes that illustrate the candidate’s strengths. Say what the candidate specifically did to give you that impression (Box 1). Don’t merely praise the candidate using generalities such as “candidate x is a quick learner”.

Use ethical principles, positive and inclusive language within the letter

Gender affects scientific careers. Avoid providing information that is irrelevant to the opportunity, such as ethnicity, age, hobbies, or marital status. Write about professional attributes that pertain to the application. However, there are qualities that might be important to the job or funding opportunity. For instance, personal information may illustrate the ability to persevere and overcome adversity - qualities that are helpful in academia and other career paths. It is critical to pay attention to biases and choices of words while writing the letter [13,14]. Advocacy bias (a letter writer is more likely to write a strong letter for someone similar to themselves) has been identified as an issue in academic environments [3]. Studies have also shown that there are often differences in the choice of words used in letters for male and female scientists [3,5]. For instance, letters for women have been found not to contain much specific and descriptive language. Descriptions often pay greater attention to the personal lives or personal characteristics of women than men, focusing on items that have little relevance in a letter of recommendation. When writing recommendation letters, employers have a tendency to focus on scholarly capabilities in male candidates and personality features in female candidates; for instance, female candidates tend to be depicted in letters as teachers and trainees, whereas male candidates are described as researchers and professionals [15]. Also, letters towards males often contain more standout words such as “superb”, “outstanding”, and “excellent”. Furthermore, letters for women had been found to contain more doubt-raising statements, including negative or unexplained comments [3,15,16]. This is discriminative towards women and gives a less clear picture of women as professionals. Keep the letter gender neutral. Do not write statements such as “candidate x is a kind woman” or “candidate y is a fantastic female scientist” as these have no bearing on whether someone will do well in graduate school or in a job. One way to reduce gender bias is by checking your reference letter with a gender bias calculator [17,18]. Test for gender biases by writing a letter of recommendation for any candidate, male or female, and then switch all the pronouns to the opposite gender. Read the letter over and ask yourself if it sounds odd. If it does, you should probably change the terms used [17]. Other biases also exist, and so while gender bias has been the most heavily investigated, bias based on other identities (race, nationality, ethnicity, among others) should also be examined and assessed in advance and during letter writing to ensure accurate and appropriate recommendations for all.

Revise and submit on time

The recommendation letter should be written using language that is straightforward and concise [19]. Avoid using jargon or language that is too general or effusive (Table 1). Formats and styles of single and co-signed letters are also important considerations. In some applications, the format is determined by the application portal itself in which the recommender is asked to answer a series of questions. If these questions do not cover everything you would like to address you could inquire if there is the option to provide a letter as well. Conversely, if the recommendation questionnaire asks for information that you cannot provide, it is best to explicitly mention this in writing. The care with which you write the letter will also influence the effectiveness of the letter - writing eloquently is another way of registering your support for the candidate. Letters longer than two pages can be counterproductive, and off-putting as reviewers normally have a large quantity of letters to read. In special cases, longer letters may be more favourable depending on the opportunity. On the other hand, anything shorter than a page may imply a lack of interest or knowledge, or a negative impression on the candidate. In letter format, write at least 3-4 paragraphs. It is important to note that letters from different sectors, such as academia versus industry tend to be of different lengths. Ensure that your letter is received by the requested method (mail or e-mail) and deadline, as a late submission could be detrimental for the candidate. Write and sign the letter on your department letterhead which is a further form of identification.

Conclusions

Recommendation letters can serve as important tools for assessing ECRs as potential candidates for a job, course, or funding opportunity. Candidates need to request letters in advance and provide relevant information for the recommender. Readers at selection committees need to examine the letter objectively with an eye for information on the quality of the candidate’s scholarly and non-scholarly endeavours and scientific traits. As a referee, it is important that you are positive, candid, yet helpful, as you work with the candidate in drafting a letter in their support. In writing a recommendation letter, summarize your thoughts on the candidate and emphasize your strong support for their candidacy. A successful letter communicates the writer’s enthusiasm for an individual, but does so realistically, sympathetically, and with concrete examples to support the writer’s associations. Writing recommendation letters can help mentors examine their interactions with their mentee and know them in different light. Express your willingness to help further by concluding the letter with an offer to be contacted should the reader need more information. Remember that a letter writer’s judgment and credibility are at stake thus do spend the time and effort to present yourself as a recommender in the best light and help ECRs in their career path.

Acknowledgements

S.J.H. was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R35GM133732. A.P.S. was partially supported by the NARSAD Young Investigator Grant 27705.

Abbreviations:

- ECR

Early-Career Researcher

- CV

Curriculum Vitae

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mellman I (2005) How to Write an Effective Letter of Recommendation. ASCB Newsletter.

- 2.Ernst M (2002) Requesting a letter of recommendation. https://homes.cs.washington.edu/~mernst/advice/request-recommendation.html

- 3.Trix F, Psenka C (2003) Exploring the Color of Glass: Letters of Recommendation for Female and Male Medical Faculty. Discourse & Society 14, 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eger H (2014) Writer perception, writer projection: The influence of personality, ideology, and gender on letters of recommendation. University of Illinois at Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J (2012) Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 16474–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellman I (2005) How to Read a Letter of Recommendation. ASCB Newsletter.

- 7.Chapnick A (2006) Reference letters revisited. University Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapnick A (2010) How to properly turn down a reference letter request. University Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tay A (2020) Writing the perfect recommendation letter. Nature 584, 158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadavji N Recommendation Letter Request Form. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSf0M11hHVGOTRwSF6IYqDitrKZmO68RtG9RstImx2wKzkejtw/viewform

- 11.Chapnick A (2009) How to ask for a reference letter. University Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Providing Content Based on Field of Study (2020) e-Education Institute, Penn State College of Earth and Mineral Sciences. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/writingrecommendationlettersonline/node/144

- 13.Canada Research Chairs (2019) Unconscious bias training module. https://www.chairs-chaires.gc.ca/program-programme/equity-equite/bias/module-eng.aspx?pedisable=false

- 14.Courchaine E, Smaga S (2016) Opinion: Fixing Science’s Human Bias. The Scientist. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madera JM, Hebl MR, Martin RC (2009) Gender and Letters of Recommendation for Academia: Agentic and Communal Differences. J Appl Psychol 94, 1591–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmader T, Whitehead J, Wysocki V (2007) A Linguistic Comparison of Letters of Recommendation for Male and Female Chemistry and Biochemistry Job Applicants. Sex Roles 57, 509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leigh N, Hainer S, de Winde C, Momeni B, Albright A (2020) Guidelines Toward Inclusive Practices in Academics by eLife Community Ambassadors. Open Science Framework. [Google Scholar]

- 18.A gender Bias Calculator. https://slowe.github.io/genderbias/

- 19.Perelman LC, Paradis J, Barrett E (1997) The Mayfield Handbook of Technical Scientific Writing. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houran J, Lange R, Ference GA (2006) Beware of “Barnum and Forer Effects” in Organizational Assessments. New York: HVS International. [Google Scholar]