The mechanochemical synthesis, crystal structure analysis, and Hirshfeld surface analysis of quininium aspirinate are reported. This salt was synthesized by liquid-assisted grinding and characterized by X-ray diffraction (single crystal and powder), FT–IR spectroscopy, thermogravimetry, differential scanning calorimetry, and aqueous solubility measurements. The amorphous powders obtained by neat grinding or neat ball milling crystallize upon storage into the salt reported.

Keywords: drug–drug salt, mechanochemistry, liquid-assisted grinding, crystal structure, antimalarial, aspirin, quinine, NSAID

Abstract

Quinine (an antimalarial) and aspirin (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) were combined into a new drug–drug salt, quininium aspirinate, C20H25N2O2 +·C9H7O4 −, by liquid-assisted grinding using stoichiometric amounts of the reactants in a 1:1 molar ratio, and water, EtOH, toluene, or heptane as additives. A tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution of the mechanochemical product prepared using EtOH as additive led to a single crystal of the same material obtained by mechanochemistry, which was used for crystal structure determination at 100 K. Powder X-ray diffraction ruled out crystallographic phase transitions in the 100–295 K interval. Neat mechanical treatment (in a mortar and pestle, or in a ball mill at 20 or 30 Hz milling frequencies) gave rise to an amorphous phase, as shown by powder X-ray diffraction; however, FT–IR spectroscopy unambiguously indicates that a mechanochemical reaction has occurred. Neat milling the reactants at 10 and 15 Hz led to incomplete reactions. Thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry indicate that the amorphous and crystalline mechanochemical products form glasses/supercooled liquids before melting, and do not recrystallize upon cooling. However, the amorphous material obtained by neat grinding crystallizes upon storage into the salt reported. The mechanochemical synthesis, crystal structure analysis, Hirshfeld surfaces, powder X-ray diffraction, thermogravimetry, differential scanning calorimetry, FT–IR spectroscopy, and aqueous solubility of quininium aspirinate are herein reported.

Introduction

Although the bark of the willow tree (containing the active ingredient salicyline, a glycoside) and its leaves have been used since around 3500 years ago for their anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic properties (Montinari et al., 2019 ▸), aspirin (or acetylsalicylic acid; IUPAC name: 2-acetyloxybenzoic acid; molecular formula C9H8O4) was easily and inexpensively prepared (DeKornfeld, 1964 ▸) by F. Hoffman around 1897 at the Bayer laboratories (Hademenos, 2005 ▸; Montinari et al., 2019 ▸) as a salicylic acid derivative with reduced adverse effects. The molecular structure of aspirin is shown in Fig. 1 ▸. Aspirin belongs to a family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with a fast absorption rate, and it is currently the most utilized drug in the world (Desborough & Keeling, 2017 ▸; Hademenos, 2005 ▸; Vane & Botting, 2003 ▸). Besides its use as a pain reliever, fever reducer and anti-inflammatory agent, aspirin has been shown to prevent heart attacks due to its platelet anti-aggregant properties (Hademenos, 2005 ▸); hence, low-dose aspirin is used to treat and prevent cardiovascular disease (Brotons et al., 2015 ▸). Aspirin’s mechanism of action is known to inhibit the activity of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, involved in the biosynthesis of prostaglandins, compounds that cause inflammation, swelling, pain, and fever (Vane & Botting, 2003 ▸; Montinari et al., 2019 ▸). This involves the irreversible acetylation of serine residues in COX-1 and COX-2, limiting the access of arachidonic acid to the enzyme’s catalytic sites. By the same mechanism, aspirin also inhibits the biosynthesis of thromboxane A2, increasing bleeding time and inhibiting platelet aggregation (Montinari et al., 2019 ▸). These discoveries led to the 1982 Medicine and Physiology Nobel prize for Samuelsson, Bergström, and Vane (Montinari et al., 2019 ▸). The possible anticarcinogenic effects of low-dose aspirin treatments are also currently under study (Montinari et al., 2019 ▸).

Figure 1.

The molecular structures of (a) aspirin and (b) quinine (note this refers only to the enantiomorph shown). The numbers shown are the pK a of the acid (red) and that of the conjugate acid of the basic functional groups (blue) for the quinuclidine- and quinoline-type heterocycles, as calculated by MarvinSketch software (Version 20.14.0; ChemAxon, 2020 ▸). Experimental pK a values are 3.49 for aspirin at 25 °C (O’Neil, 2006 ▸) and 8.52 for the quinuclidine-type heterocycle of quinine in water at 25 °C (Nagy et al., 2019 ▸).

Moreover, willow tree extracts have been previously used to relieve fever symptoms of malaria, similar to cinchona extracts (Montinari et al., 2019 ▸) containing the more expensive quinine (DeKornfeld, 1964 ▸). Quinine is an alkaloid found (together with quinidine, cinchonine, and cinchonidine) in the bark of the quina-quina (or cinchona) tree, whose extracts have been used to treat malaria since the 1600s by Europeans and, according to legend, even before then by South American native populations (Achan et al., 2011 ▸; Gisselmann et al., 2018 ▸).

Unlike aspirin, quinine {IUPAC name: (R)-[(2S,4S,5R)-5-ethenyl-1-azabicyclo[2.2.2]octan-2-yl]-(6-methoxyquinolin-4-yl)methanol; molecular formula C20H24N2O2}, has substantial adverse effects (Achan et al., 2011 ▸; Punihaole et al., 2018 ▸). Its molecular structure is shown also in Fig. 1 ▸. While quinine remains an effective antimalarial to all four Plasmodium parasites, its principal mechanism of action still remains unclear, although it is hypothesized (Punihaole et al., 2018 ▸) to involve the disruption of hemozoin biocrystallization (Pagola et al., 2000 ▸). Low dosages of quinine have been used to treat leg cramps (Gisselmann et al., 2018 ▸), although its mechanism of action as a muscle relaxant is not well understood either. However, due to its negative effects on the central nervous system at high doses (e.g. to treat malaria), its poor tolerability, and the existence of other efficacious antimalarials (Achan et al., 2011 ▸), quinine is only currently approved in the USA by the FDA as Qualaquin (quinine sulfate dihydrate capsules) for uncomplicated malaria treatment caused by Plasmodium falciparum. Quinine is also known to block acetylcholine responses and activate the T2R’s bitterness taste receptors, for which it is used in low doses in tonic water and bitter lemonades (Gisselmann et al., 2018 ▸).

Multidrug combinations are a relatively unexplored and patentable type of materials of increasing interest (Darwish et al., 2018 ▸), not only related to crystal engineering studies and the improvement of the physicochemical properties of drugs, but due to monotherapies (one drug to treat one disease) are currently not always considered effective to manage various complex illnesses such as cancer, diabetes, infectious, and cardiovascular diseases (Thipparaboina et al., 2016 ▸). Besides, doctors commonly prescribe together various drugs (Sekhon, 2012 ▸) and multidrug combinations offer opportunities for exploring synergistic beneficial effects (Darwish et al., 2018 ▸).

As part of this work, undergraduate students designed combinations of pharmaceutical drugs toward forming drug–drug salts or cocrystals (Sekhon, 2012 ▸; Thipparaboina et al., 2016 ▸), while they simultaneously explored the solid-state reactivity of organic compounds by mechanochemistry, using laboratory powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) for crystal phase identification. The ΔpK a rule (Ramon et al., 2014 ▸; Kumar & Nanda, 2018 ▸) undoubtedly indicates a salt will be formed when quinine and aspirin are combined (see Fig. 1 ▸), involving proton transfer from aspirin’s carboxylic acid group to the most basic N atom of the quinuclidine-type heterocycle of quinine.

Another objective of this study was to gather information about the effects of different solvents as additives used for liquid-assisted grinding (LAG), a mechanochemical synthesis method, which is known to accelerate mechanochemical reactions (Friščić, 2010 ▸), generally enhance the crystallinity of the products, occasionally promote the selective formation of different product polymorphs or stoichiometries (Trask & Jones, 2005 ▸; Hernández & Bolm, 2017 ▸), or just to enable mechanochemical reactivity (Friščić, 2010 ▸). Thus, LAG syntheses were carried out with a series of solvents of different dielectric constants (water, EtOH, toluene, and heptane) and by neat grinding (NG) in an agate mortar with pestle. Since the latter products were amorphous (as determined by PXRD), this prompted us to further study by FT–IR spectroscopy the effects of the overall mechanical energy furnished to the reactants, in the physicochemical properties of the mechanochemical products obtained by neat mechanical treatment. Toward the investigation of the overall mechanical energy input effects, a series of neat syntheses were carried out in a ball mill using increasing milling frequencies (10, 15, 20, and 30 Hz). These studies were complemented by the characterization of a crystalline and an amorphous product by thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry.

This work reports the mechanochemical reactivity of quinine and aspirin by NG and LAG, crystal growth, and crystal structure analysis, including Hirshfeld surfaces, FT–IR spectroscopy, PXRD, thermogravimetry, differential scanning calorimetry, and aqueous solubility of the salt formed between quinine and aspirin in a 1:1 molar ratio, and its related amorphous phases.

Experimental

Materials

Aspirin (+99.0% purity) and quinine (+98.0% purity) were purchased from Sigma and were used as received. They were both crystalline powders (as confirmed by PXRD) and the aspirin crystallites were visible to the naked eye. The organic solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received. Absolute EtOH was used for crystal growth and in the mechanochemical syntheses. MilliQ water was freshly obtained before use. The neat mechanochemical syntheses using a ball mill were performed with aspirin powders slightly ground in a mortar with pestle to reduce detrimental microstructure effects in the PXRD and FT–IR data of the reaction products.

Mechanochemical synthesis

Quininium aspirinate (I) was prepared by LAG using a series of liquids as additives: milliQ water, EtOH, toluene, or heptane. The samples were prepared by manually grinding the reactants in an agate mortar with pestle, under air, for 20 min in all cases. For LAG with water, 1.98 × 10−4 moles (0.0356 g) of aspirin and 1.98 × 10−4 moles (0.0642 g) of quinine were ground together with 200 µl of milliQ water (2 µl mg−1 of reactants). NG in a mortar and pestle was carried out from the same reactant masses. For LAG with toluene and heptane, the above masses were ground with 200 µl of liquid added immediately before the start of grinding and halfway during the reaction, to compensate for evaporation losses (for a total of 4 µl mg−1 of reactants ground). For LAG with EtOH, 6.0 × 10−5 moles (0.0107 g) of aspirin were ground together with 6.0 × 10−5 moles (0.0193 g) of quinine and 60 µl of EtOH (2 µl mg−1 of reactants ground).

Neat mechanochemical reactions were also carried out in an IST500 InSolido Tech ball mill using 6.0 × 10−5 moles (0.0107 g) of aspirin and 6.0 × 10−5 moles (0.0193 g) of quinine, for a 35 min milling time in all cases. Two 5 mm-diameter SAE 304 stainless steel balls and a 14 ml PMMA jar were used at variable milling frequencies of 10, 15, 20, and 30 Hz.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details for I are summarized in Table 1 ▸. Single crystals of I were grown in the dark at 295 K, by slow solvent evaporation from a THF solution (0.5 ml) of the LAG product (0.0083 g) obtained using EtOH as additive. Further I (also LAG EtOH) (0.0084 g) was dissolved in MeOH (0.5 ml) and resulted in single crystals of a salt of quinine and salicylic acid (quininium salicylate) in a 1:1 molar ratio; however, the crystal quality did not afford diffraction data suitable for reliable discussion of its bonding and stereochemistry, and therefore it is not included in this article. However, the calculated PXRD data were used for the identification of quininium salicylate in reaction products initially amorphous, which crystallized upon long-term storage (see §3.4).

Table 1. Experimental details.

| Crystal data | |

| Chemical formula | C20H25N2O2 +·C9H7O4 − |

| M r | 504.56 |

| Crystal system, space group | Orthorhombic, P212121 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 8.6256 (12), 9.6680 (13), 30.557 (4) |

| V (Å3) | 2548.2 (6) |

| Z | 4 |

| Radiation type | Mo Kα |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.09 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.23 × 0.22 × 0.18 |

| Data collection | |

| Diffractometer | Bruker Kappa APEXII CCD |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (SADABS; Bruker, 2017 ▸) |

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.91, 0.98 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 45099, 5223, 4290 |

| R int | 0.067 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.625 |

| Refinement | |

| R[F2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.040, 0.080, 1.05 |

| No. of reflections | 5223 |

| No. of parameters | 344 |

| No. of restraints | 1 |

| H-atom treatment | H atoms treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.18, −0.19 |

| Absolute structure | Flack x determined using 1588 quotients [(I +) − (I −)]/[(I +) + (I −)] (Parsons et al., 2013 ▸) |

| Absolute structure parameter | 0.2 (5) |

The H atoms of the O—H and N—H groups were located on an electron-density map and were refined isotropically. All other H atoms were placed in geometrically calculated positions, with U iso(H) = 1.2U eq of the parent atom, or with U iso(H) = 1.5U eq for methyl H atoms. Full crystallographic data collection parameters and results, including geometrical parameters describing hydrogen bonding, are given in Table 1 ▸ and the CIF file. The reported absolute configuration of the quininium ions is that corresponding to the reactant label provided by the commercial supplier, due to the anomalous dispersion effects using Mo radiation are not significant enough to establish the absolute structure.

Powder X-ray diffraction

Laboratory powder X-ray diffraction data were collected in a Bruker D2 Phaser diffractometer using Cu radiation (Kα, λ = 1.5418 Å), Bragg–Brentano optics and a θ–θ configuration, equipped with a LynxEye position sensitive detector. The powders were spun at 15 rpm during data collection and the continuous scan mode was used in all cases. For crystal phase identification purposes, the reaction products were loaded on 0.5 mm depth Si flat plate holders. A 0.2 mm divergence slit, a 3 mm detector slit, and a 1 mm air antiscatter screen were used. The diffracted radiation was measured in 0.02° steps using a 1° detector opening and a 1 s per step counting time, from 2θ = 3° to 2θ = 60°. For the samples milled in the ball mill, a 0.6 mm divergence slit, an 8 mm detector slit, a 1 mm antiscatter screen, and a 0.5° detector opening were used. Diffraction data were collected in the same 2θ interval and with a 0.02° step size, using a 0.6 s per step counting time. The high-quality data set collected at 295 K used for the determination of the unit-cell parameters of I was collected using a 3 mm air antiscatter screen, a 0.6 mm divergence slit, and a 3 mm detector slit, from a zero-background flat plate holder of 2.5 cm diameter × 0.2 mm depth (to reduce transparency effects), as a continuous scan in linear detector mode, with a 0.1° detector opening, 0.02° steps and 30 s per step counting time, from 2θ = 5.0° to 2θ = 90°.

Thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves were measured in a TA instruments Q5000 balance using the high-resolution dynamic mode from room temperature to 250 °C, using a 10 °C min−1 heating rate, a resolution of 4 and a sensitivity of 1, an N2 gas flow of 50 ml min−1, and 50 ml Pt pans. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) data were collected in a TA 2500 differential scanning calorimeter using Al pans and lids, from 25 to 155 °C at a 2 °C min−1 heating rate and an N2 gas flow of 50 ml min−1. Indium was used as a calibration standard.

FT–IR spectroscopy

FT–IR spectroscopy data were measured using a Bruker Alpha FT–IR spectrophotometer with OPUS data collection software, a platinum ATR attachment, and a diamond crystal, in the 400–4000 cm−1 wavenumber interval, using 24 scans and a 4 cm−1 resolution. Data analysis was performed using the SpectraGryph software (Version 1.2.15; Menges, 2016 ▸).

Aqueous solubility

The aqueous solubility of I was measured by gravimetry. For this purpose, quininium aspirinate (68.2 mg) was mixed with milliQ water (8.00 ml). The saturated solution was stirred for 2 h and 45 min under ambient conditions. The undissolved solid was filtered off and weighed the following day once dry; its mass was 37.9 mg. The solubility was calculated using the fraction of powder dissolved (30.3 mg). The calculated aqueous solubility is 3.8 mg ml−1. The pH of a saturated solution of I was measured with a Fisher Scientific Accumet XL150 pH and conductivity meter.

Results and discussion

Single-crystal structure analysis and Hirshfeld surfaces

A search in the Cambridge Structural Database (Version 5.42, February 2021 update; Groom et al., 2016 ▸) resulted in 146 hits for quinine compounds and 81 hits for aspirin compounds, from which 29 correspond to aspirin itself. The crystal and molecular structures of aspirin have been considerably studied (Toader et al., 2020 ▸). While form I has been known since the 1960s, another crystal structure (form II) has been predicted, and it was reported from experimental data in 2005 (Vishweshwar et al., 2005 ▸). However, the actual existence of form II as a new polymorph was later disputed by a more recent study (Bond et al., 2007 ▸), concluding that aspirin crystals are in general intergrowths of domains with the crystal structures of forms I and II, and the maximum proportion of form II domains observed in a single crystal has been 85%. Furthermore, aspirin salts of Li+, Na+, K+, and Rb+ are known, and various cocrystals, a few clathrates, and combinations with other drugs have been reported. Among those are aspirin carbamazepine (Vishweshwar et al., 2005 ▸), aspirin 5-methoxysulfadiazin (Caira, 1994 ▸), aspirin meloxicam (Cheney et al., 2012 ▸), aspirin pentoxifylline (Stepanovs et al., 2015 ▸), and aspirin theophylline (Darwish et al., 2018 ▸). The aspirin meloxicam cocrystallization by NG and LAG using CHCl3 has been used to model the reactant’s approach and molecular mixing during mechanochemical treatment in a ball mill by molecular dynamics calculations (Ferguson et al., 2019 ▸).

The quinuclidine-type N atom of quinine (see Fig. 1 ▸) is generally protonated in salts since it is more basic than the quinoline N atom, although the latter often forms coordination bonds with transition metals, and occasionally is also protonated. MarvinSketch software (Version 20.14.0; ChemAxon, 2020 ▸) was used to calculate the pK a of aspirin as 3.41, and those of the conjugate acid forms of the basic N atoms of quinine as 9.05 (quinuclidine heterocycle) and 4.02 (quinoline heterocycle). Experimental values are provided in the Fig. 1 ▸ caption. Considering the rule ΔpK a ≥ 2 (or 3) for salt formation (Ramon et al., 2014 ▸; Kumar & Nanda, 2018 ▸), quinine and aspirin in a 1:1 molar ratio are unambiguously expected to form a salt, since 8.52 − 3.49 = 5.03 (from experimental pK a values) or 9.05 − 3.41 = 5.64 (from calculated values). Proton transfer and salt formation were confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

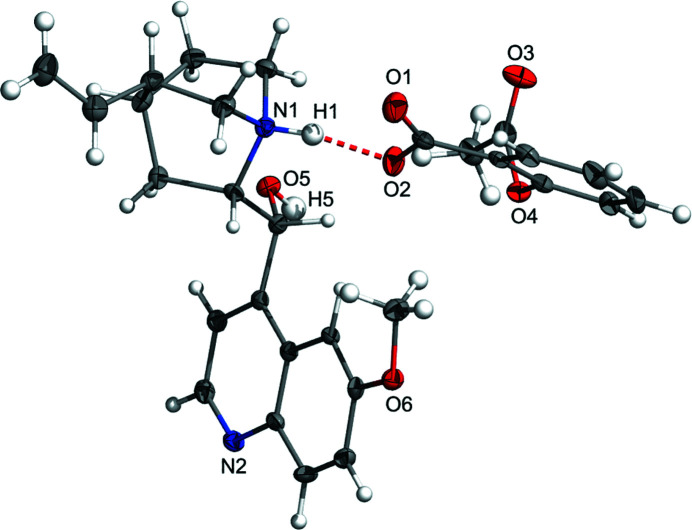

The asymmetric unit of I is shown in Fig. 2 ▸. It is composed of one aspirinate anion and one quininium cation. The distance between the carboxylate O2 atom in the aspirinate anion and the protonated N1 atom in the quininium cation is 2.603 (3) Å, while the N1—H1 and H1—O2 bond lengths are 0.96 (3) and 1.66 (3) Å, respectively, and the N1—H1⋯O2 angle is 167 (3)°. The two C—O distances in the carboxylate residue of aspirin, 1.230 (3) and 1.277 (3) Å, are close, as expected for an ionized residue (Childs et al., 2007 ▸).

Figure 2.

The asymmetric unit of I. Salt formation is evidenced by the proton transfer from aspirin to the quinuclidine-type heterocyclic N atom of the quininium cation. Hydrogen bonding is shown with a dashed red line. Color code: C grey, N blue, O red, and H white.

The less basic quinoline N atom of the quininium ion functions as a hydrogen-bond acceptor to the –OH group of a neighboring quininium cation at 2.828 (3) Å. This is shown in Fig. 3 ▸(a). Moreover, since each quininium cation is hydrogen bonded to two other neighboring quininium cations, through its quinoline N2 atom (hydrogen-bond acceptor) and the O5 atom of the hydroxy group (hydrogen-bond donor), the extension of this packing motif along the a axis gives rise to zigzag chains, as shown in Fig. 3 ▸(a). The interplanar angle between adjacent quinoline planes (defined by the mean of 10 atoms) is 64.4 (1)°. A similar zigzag chain packing motif involving the same functional groups of quinine has been reported for the quininium saccharinate salt in a 1:1 molar ratio (Bhatt et al., 2005 ▸; Clements et al., 2015 ▸), which also similarly crystallizes in the space group P212121 (Z = 4), with a = 9.607 (3), b = 8.634 (3), and c = 30.371 (9) Å. This is not surprising, since the hydrogen-bonding motif constructed from these presumably energetically strong interactions also affords accommodating small counter-ions, such as aspirinate or saccharinate, in the space close to the positively charged quinuclidine N atom. The angle between quinoline planes calculated by Mercury (Version 2020.1; Macrae et al., 2020 ▸) using the mean of 10 atoms, is similarly 57.7 (1)° for quininium saccharinate.

Figure 3.

(a) The zigzag chains extending along the a axis in the crystal structure of I, viewed along the b-axis direction. These are generated by the hydrogen-bonding motif among neighboring quininium ions, involving both the –OH group (hydrogen-bond donor) and the quinoline N atom (hydrogen-bond acceptor) of each quininium cation. Hydrogen bonds are shown with dashed lines. Color code: C grey, N blue, O red, and H light grey. The crystallographic axes are represented in red (a axis), green (b axis), and blue (c axis). (b) View along the a-axis direction of the same zigzag chains, with molecules colored by symmetry equivalence. Note the regions lacking hydrogen-bonding interactions (shown with dashed lines) between adjacent chains.

The above analysis of the crystal structure of I was complemented by the calculation of Hirshfeld surfaces (Spackman & Jayatilaka, 2009 ▸) shown in Fig. 4 ▸, to study the interatomic close contacts in I. As expected, this method indicates prominent close contact features (represented as red areas) due to hydrogen bonding around the hydroxy O5 atom (hydrogen-bond donor) of the quininium ions and the quinoline N2 atom (hydrogen-bond acceptor) of the same moieties [see Fig. 4 ▸(a)]. This figure shows also a few other less significant short contacts, suggesting the formation of weak (nonclassical) –CH hydrogen bonds to the O atoms of the –OH and –OCH3 groups in quininium cations, and to the C=O oxygen (of the ester functional group) in the aspirinate anions. The close contact due to the ionic interaction between the proton transferred to N1 and the carboxylate O2 atom of the aspirinate ion is mapped in Fig. 4 ▸(b). Two other short contacts involving the remaining carboxylate O1 atom of aspirinate are also displayed.

Figure 4.

(a) Hirshfeld surface of the asymmetric unit of I. Normalized contact distances (d norm) are represented in the scale −0.3 to 0.8. Red, white, and blue colored areas represent regions where the intermolecular contacts are shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radii, at around those values, and longer than them, respectively. The largest red areas correspond to close hydrogen-bonding distances around the –OH functional group (hydrogen-bond donor) and the quinoline-type N atom of the quininium ion (hydrogen-bond acceptor). (b) Hirshfeld surface of the aspirinate anion represented at the same scale. The largest red area corresponds to the ionic interaction between the carboxylate group of the aspirinate anion and the protonated N atom of the quininium cation. (c) View of the Hirshfeld surface around the asymmetric unit (using the same scale), including the surrounding molecules with fragments at 2.6 Å radial distance. The crystallographic axes are represented in red (a axis), green (b axis), and blue (c axis).

Fig. 5 ▸ shows the calculated 2D fingerprint plots (Spackman & Jayatilaka, 2009 ▸). Most of the close contacts (53.6%) correspond to H⋯H interactions, as in many organic solids, followed by O⋯H contacts (19.8%), in agreement with the presence of classical and weak hydrogen bonding, and salt formation as previously described. Nearly as close in significance are the C⋯H contacts (19.6%). The remaining interactions are less significant, N⋯H (4.5%), C⋯C (1.2%), C⋯O (1.0%), and N⋯C (0.3%). π–π intermolecular interactions are not a significant feature of this structure, as inferred from the low value for the C⋯C contacts, corresponding to the packing motif described above, presumably directed by hydrogen-bonding interactions and molecular shape.

Figure 5.

2D Fingerprint plots of the distances from the Hirshfeld surface to the nearest nucleus inside the surface (d i) and outside the surface (d e), calculated for the asymmetric unit of I. (a) All atoms (without element distinction), (b) H⋯H contacts, (c) O⋯H contacts, (d) C⋯H contacts, (e) N⋯H contacts, (f) C⋯C contacts, (g) C⋯O contacts, and (h) C⋯N contacts. The corresponding percentages of the total shown in part (a) are shown in parentheses in each of the remaining graphs.

Esters such as aspirin can hydrolyze into acids and alcohols. In aspirin, the alcohol functional group (actually, a phenol) forming the ester is furnished by salicylic acid (which is a carboxylic acid as well), while the acid produced by hydrolysis is acetic acid. Since a salicylate of quinine was found as a crystal in the crystallization experiment from an MeOH solution of I, aspirin hydrolysis into salicylic and acetic acids is implied. The crystal structure of quininium salicylate dihydrate has been reported (Oleksyn & Serda, 1993 ▸); however, the crystal obtained in our work was not a hydrate. It has been released as a communication with the CCDC deposition number 2003355.

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)

As indicated in §2.2, the mechanochemical synthesis of I occurred by LAG using milliQ water, EtOH, toluene, or heptane in a mortar and pestle. This was confirmed by the overlay of the powder diffraction patterns of the mechanochemical reaction products with the calculated PXRD data, as shown in Fig. 6 ▸. However, the neat mechanochemical reactions, in a mortar and pestle or in a ball mill at 20 and 30 Hz milling frequency, yielded amorphous phases instead. The reaction products of neat milling at 10 and 15 Hz remained partially crystalline, as they show aspirin diffraction peaks, and also quinine peaks in the sample milled at 10 Hz. This is shown in Fig. S1 in the supporting information.

Figure 6.

Overlay of the powder X-ray diffraction data of quininium aspirinate (I), zoomed for clarity in the 3 to 40° 2θ interval. (a) Products neat ground for 20 min in a mortar and pestle, (b) LAG heptane, (c) LAG toluene, (d) LAG EtOH, (e) LAG milliQ water, and (f) the calculated PXRD pattern using the atomic coordinates of I reported (at 100 K) using Mercury (Version 2020.1; Macrae et al., 2020 ▸).

A Le Bail fit (Le Bail, 2005 ▸) of the PXRD data of I at 295 K was carried out with the software GSAS (Larson & Von Dreele, 2004 ▸) to determine the unit-cell parameters at room temperature. This is shown in Fig. S2 (see supporting information). The agreement factors were R wp = 4.71% and χ2 = 2.26. The refined lattice parameters (also in P212121) are a = 8.748 (3), b = 9.711 (3) Å, c = 30.463 (11) Å, α = β = γ = 90°, and V = 2587.9 (16) Å3, without observable impurity peaks at a maximum scale of around 50 000 counts, ruling out a crystallographic phase transition in the 100–295 K interval. In comparison with the low-temperature structure, with a = 8.6256 (12), b = 9.6680 (13) and c = 30.557 (4) Å, it is experimentally observed that a temperature increase leads to the expansion of the a and b axes (by 1.4 and 0.4%, respectively), while the c axis is shortened by 0.3%. Considering the Hirshfeld surface shown in Fig. 4 ▸(c), showing the presumably energetically strong and markedly directional hydrogen-bonding interactions forming zigzag chains running along the a axis, a tentative explanation for the lattice changes with temperature is that an average reduction in interatomic (and hydrogen-bond) distances along the c axis (leading to cohesion energy gains at 295 K) serves to compensate for the increased molecular movement (due to internal energy gains at 295 K) and lattice expansion along the other two crystallographic axes, which might also slightly distort the position/orientation of the molecules in the zigzag chains (e.g. the angle between quinoline-ring planes).

Thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry

The samples prepared by LAG with water and by ball milling at 20 Hz (amorphous by PXRD, see Fig. S1 in the supporting information) were used for thermogravimetry (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements. The TGA results are shown in Figs. S5 and S6, indicating that neither of them loses mass noticeably while heating until decomposition occurs, since the recovered samples were black in color. The maxima in the derivatives of the heating curves occur at around 200 °C for the crystalline sample (I) and at around 185 °C for the amorphous sample. Note that the derivative curves are quite flat for the room temperature to 120 °C interval, indicating the absence of mass loss.

DSC measurements revealed various thermal events shown in Fig. 7 ▸. The heating curve of I shows a broad endothermic peak centred at around 102.3 °C, then a large exothermic peak, and almost immediately after this an endothermic peak, likely due to melting at 146.6 °C. The first endothermic peak is tentatively assigned to a glass transition (Newman & Zografi, 2020 ▸). Although this could be due to a polymorphic transition as well, the transition of the crystalline solid to a glass is supported by PXRD of another fraction of the same sample heated at 125 °C in an oven for 1.5 h, showing an amorphous phase (Fig. S3). The exothermic peak at 145.0 °C is tentatively assigned to a recrystallization event (or some type of partial long-range ordering increase) before melting. The cooling curve only shows a subtle baseline change at around 65–70 °C. Moreover, considering the results shown in Figs. 3 ▸ and 4 ▸, it is plausible that this transition to an amorphous phase involves movements of the hydrogen-bonded chains with respect to their neighbour chains [see Fig. 3 ▸(b)], held together in the crystal by presumably weaker interactions than intra-chain hydrogen bonding.

Figure 7.

DSC curves for (a) I prepared by LAG water (initially crystalline), including two zoomed regions, and (b) the amorphous phase prepared by milling at 20 Hz for 35 min. Heating curves are shown as a red line, while the cooling curves are in green. The temperatures of the thermal events are indicated, and in part (b), the estimated onset temperature of the glass transition is shown (Newman & Zografi, 2020 ▸).

The DSC curves of the amorphous sample milled at 20 Hz for 35 min are different than the above data, but they are similarly interpreted. First, a broad exothermic peak centered at around 50 °C is observed, which is tentatively assigned to a partial long-range order increase process in the amorphous phase (deemed to be a glass). After this, a large endothermic peak at around 99.8 °C occurs, deemed to be due to a glass transition to a supercooled liquid with its associated relaxation enthalpy (Newman & Zografi, 2020 ▸). Note the baseline change for an estimated glass transition onset at 92.0 °C that is evident from these data. After this thermal event, a broad exothermic feature in the baseline is seen, tentatively followed by recrystallization or a partial long-range order increase (exothermic) at 139.0 °C, and melting (endothermic), which happens also at a lower temperature than that of I, at 142.0 °C. While for this initially amorphous material the relaxation enthalpy peak is pronounced, the partial long-range order increase or recrystallization exotherm is less significant. The cooling curve does not show important thermal events other than a small endothermic peak at around 68.3 °C. Assuming that a significant fraction of the material has not been decomposed after heating to 155 °C (as indicated by TGA), these materials do not seem to recrystallize during cooling using these conditions, since no exothermic events are seen in the respective cooling curves.

The literature melting point of aspirin is 136 °C, while that of quinine is around 174 °C. As reported for around half of salts/cocrystals, the melting point of I (146.6 °C) is between those of the individual components, and it is also within the 140–170 °C interval, where most melting points of binary systems (around 25–28%) are found (Perlovich, 2017 ▸).

FT–IR spectroscopy and aqueous solubility measurements

FT–IR spectroscopy has also been used to characterize the crystalline and amorphous products. The whole spectra (400–4,000 cm−1) of all crystalline products obtained by LAG in a mortar and pestle are overlayed in Fig. S7 (see supporting information), while Fig. 8 ▸ below shows a zoom of the data in the 400–1800 cm−1 interval, for clarity, of a sample obtained by LAG with water. The similitude among the spectra of all the LAG products points to the formation of a unique material, I, as determined by PXRD (Fig. 6 ▸). The absorption bands in the 400–1800 cm−1 spectral region labeled in Fig. 8 ▸ correspond to I prepared by LAG with water.

Figure 8.

Overlay of the FT–IR spectra of the mechanochemical products obtained by LAG in an agate mortar and pestle (I, as determined by PXRD), using water as the LAG additive (blue line), and the mixture of unreacted reactants in a 1:1 molar ratio (green, dotted line). The wavenumbers (in cm−1) of the absorption bands of I are shown.

The spectra of the crystalline products in Fig. 8 ▸ are also significantly different from that of the unreacted mixture of quinine and aspirin in a 1:1 molar ratio, which also confirms that mechanochemical reactions have occurred independently from PXRD. In particular, the intense band at 1691 cm−1 (see Fig. 8 ▸), assigned to the stretching vibration of the phenyl ring of aspirin (Ye et al., 2005 ▸), is noticeably absent in the FT–IR spectrum of I.

Moreover, although TGA and DSC measurements suggest some similarity between I and the amorphous phase obtained by NG or neat ball milling, it was of interest to investigate using FT–IR spectroscopy whether the amorphous phases obtained were made of the unreacted reactants or not. While the initial mechanochemical syntheses by LAG and NG in a mortar and pestle were carried out in 2019, the mechanochemical syntheses in the ball mill (with milling frequency control) were done in 2021. This allowed us to collect FT–IR and PXRD data sets of the sample prepared by NG in 2019, which was around two years old at the time the second data sets were collected. These experiments led to an unexpected observation. The FT–IR spectra of the two-year-old NG sample and that of the products (LAG water) are almost superimposable (see Fig. S8). Note that in both cases aspirin has been consumed, since the band at 1691 cm−1 is absent. In addition, recent PXRD data showed that the same initially amorphous sample stored for around two years is now crystalline. The PXRD data is shown in Fig. S4(a) and indicates that I is present, in addition to another crystalline phase which could not be identified, but it is not one of the reactants or quininium salicylate [see Fig. S4(b)]. These observations indicate that the amorphous phase obtained immediately after NG (and most likely neat ball milling) is metastable with respect to I, and lead to the crystalline product (I) upon storage. This apparently proceeds through a crystalline intermediate which could not be fully characterized.

Additional syntheses were carried out to characterize the powders treated without a liquid phase in the ball mill, since, in this case, the reactivity depends on the milling frequency and the amount of mechanical energy provided to the reactants (as the average kinetic energy of the balls and the average number of collisions with the reactants). Toward understanding whether quinine and aspirin in the amorphous phase obtained by milling at 30 Hz have reacted or not, the overlay of the FT–IR data of I (crystalline, LAG water) with the spectra of the products milled at 30 Hz, and the unreacted mixture in a 1:1 molar ratio is shown in Fig. S9 (see supporting information). This figure shows also that the FT–IR spectrum of the sample milled at 30 Hz bears a resemblance to the data of I and it is markedly different from the data of the unreacted mixture. In particular, the absence of the aspirin band at 1691 cm−1 indicates the occurrence of a mechanochemical reaction. However, there are sufficient differences between the former two FT–IR data sets to conclude that the amorphous powders obtained by neat milling at 30 Hz also differ from I. Since FT–IR spectroscopy of solids is sensitive to the symmetry of the vibrational modes and also to the environment in a crystal lattice (e.g. different organic polymorphs can have different FT–IR spectra), it is not trivial to infer whether the amorphous phase is made of the quininium and aspirinate ions without a long-range periodic order, or not.

Furthermore, the effect of the milling frequency on product formation was also studied by FT–IR spectroscopy. Although the data are not suitable for quantitative phase analysis by PXRD or FT–IR, Fig. 9 ▸ shows that the FT–IR data of the samples milled at 10 and 15 Hz resemble those of the unreacted mixture in a 1:1 molar ratio and, in both cases, shows the aspirin band at 1691 cm−1, indicating that aspirin has not been totally consumed and a partial reaction has occurred, in agreement with PXRD (see Fig. S1). The FT–IR spectra of the samples milled at 20 and 30 Hz are also very similar and indicate the occurrence of a mechanochemical reaction.

Figure 9.

(a) Overlay of the FT–IR spectra of quinine and aspirin in a 1:1 molar ratio for the unreacted mixture (green, dotted line). The aspirin band at 1691 cm−1 is indicated. (b) Products milled at 10 Hz (light blue, solid line), (c) products milled at 15 Hz (blue, solid line), (d) products milled at 20 Hz (orange, solid line), and (e) products milled at 30 Hz (red, solid line). In all cases, absorbance has been normalized to unit at the maximum of each spectrum and the baseline has been subtracted.

Considering the TGA and DSC results shown, due to the fact that a noticeable mass loss is not observed by TGA (and the reactions occurred in closed PMMA jars), in addition to the similitudes that are tentatively inferred from the DSC data of I and the amorphous milled at 20 Hz, it is tentatively expected that the amorphous obtained as product is made of the reacted reactants lacking long-range crystalline order (a glass), although amorphous phases also contain different amounts of residual long-range ordering (Bates et al., 2006 ▸), which also depend on the processes which rendered them amorphous.

The solid-state characterization of the mechanochemical products also suggests that one of the roles of the LAG liquids is to facilitate (or enable, in this case) the crystallization of the mechanochemical product, for example, accelerating the nucleation of the new crystalline phase (I) from an amorphous phase formed by mechanical treatment. In this context, the molecular dynamics calculations for the aspirin–meloxicam system (Ferguson et al., 2019 ▸) suggested a LAG liquid role (CHCl3 in that case), leading to an enhancement of the ductility of a ‘connective neck’ (an elongated connecting region) formed between two reacting molecular clusters under conditions simulating the mechanical treatment in the ball mill. Tentatively further using these ideas in this discussion, a crystalline phase (the product) could be formed from those hypothetical ‘connectivity necks’ and be separated from the reactants into new product crystallites (also aided by mechanical treatment), due to quick solvent loss from them (which naturally occurs due to evaporation if an agate mortar is used, or due to the larger mobility of the liquid additive molecules at around room temperature, even inside the reaction jar of a ball mill). This would occur exploiting also possible effects of the liquid additive molecules (in the ‘connectivity necks’) to orient molecular dipoles or charged species, enhancing the system’s capability to achieve the necessary concerted molecular movements and space filling leading to the new crystalline phase. It is interesting to mention that the amounts of isopropanol necessary for the crystallization of I are negligible, since once the ball mill reaction (intended to be by neat milling) produced I (confirmed by PXRD) only by contamination of the reaction jar with isopropanol left over from incomplete drying after washing the PMMA jar.

Furthermore, salts of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are generally chosen to increase the aqueous solubility of the API, if the APIs are ionizable. In this work, the aqueous solubility of I at 295 K was determined to be 3.8 mg ml−1, a value comparable with that of quininium saccharinate, with an aqueous solubility of 5.40 mg ml−1. It has also been reported that the latter is 4.5 times more soluble than the marketed sulfate, with an aqueous solubility of 1.20 mg ml−1 (Banerjee et al., 2005 ▸). The pH of a saturated solution of I was 4.96, which would make it suitable for injectable formulations. Since I forms also glassy and amorphous phases, this offers additional possible approaches for formulation; however, the crystallization of I from metastable phases upon storage must be taken into account.

Qualaquin capsules contain 324 mg of USP quinine sulfate dihydrate, equivalent to 269 mg of quinine (as free base). This quinine dose is delivered by 417.6 mg of I, containing 149 mg of aspirin. The known safety of aspirin could make it unnecessary to conduct additional clinical trials or toxicity studies, and the side effects and toxicity of I would be solely determined by the quinine dose used. Moreover, the drug–drug combination in I might present synergistic beneficial effects for the treatment of malaria fevers and so lead to opportunities for the development of synergistic therapies, or to allow the use of lower quinine effective dosages, which would increase the tolerability of the therapy.

Summary and conclusions

This work reports the liquid-assisted grinding synthesis from four liquid additives (heptane, toluene, EtOH, and water), the milling frequency effect for neat mechanochemical reactions in a ball mill, the crystal structure from single-crystal X-ray diffraction (at 100 K), Hirshfeld surface analysis, FT–IR spectroscopy, powder X-ray diffraction, thermogravimetry, differential scanning calorimetry, and aqueous solubility of a new drug–drug salt, quininium aspirinate, and its related amorphous phases.

While the mechanical treatment (neat or with liquid additives) always leads to reaction, as confirmed by FT–IR spectroscopy, crystalline products (quininium aspirinate) were only obtained by LAG, without distinction among the additives used. Amorphous phases were obtained by NG in an agate mortar with pestle, or in a ball mill (at 20 and 30 Hz milling frequencies). Partial reactivity was observed by PXRD and FT–IR spectroscopy in the materials neat milled at 10 and 15 Hz. Salt formation was confirmed by single-crystal diffraction. PXRD was used to demonstrate that the materials obtained by LAG have the same crystal structure as the single crystal grown from THF solution, and FT–IR further supported these results. The lattice parameters at 295 K are reported from PXRD data analysis, and a crystallographic phase transition was not observed in the 100–295 K interval.

TGA and DSC were used to characterize the crystalline (prepared by LAG water) and amorphous reaction products (milled at 20 Hz), both of which show amorphous phases upon heating at temperatures in the order of 100 °C. Crystalline quininium aspirinate is around three times more soluble in water than the marketed sulfate. Since aspirin is proven to be a safe drug, the combination would not need extensive toxicity studies before approval, and it could potentially be used as a preventive medicine against malaria in low doses, or as a drug-delivery form with synergistic therapeutic properties.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229621008275/ep3016sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229621008275/ep3016Isup2.hkl

Additional information and spectra. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229621008275/ep3016sup3.pdf

CCDC reference: 2003354

Acknowledgments

SP gratefully acknowledges the International Centre for Diffraction Data for partial funding. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T34GM118259. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Matching funds from Old Dominion University is also acknowledged.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant T34GM118259; International Centre for Diffraction Data grant GIA 08-04.

References

- Achan, J., Talisuna, A. O., Erhart, A., Yeka, A., Tibenderana, J. K., Baliraine, F. N., Rosenthal, P. J. & D’Alessandro, U. (2011). Malar. J. 10, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R., Bhatt, P. M., Ravindra, N. V. & Desiraju, G. R. (2005). Cryst. Growth Des. 5, 2299–2309.

- Bates, S., Zografi, G., Engers, D., Morris, K., Crowley, K. & Newman, A. (2006). Pharm. Res. 23, 2333–2349. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, P. M., Ravindra, M. V., Banerjee, R. & Desiraju, G. R. (2005). Chem. Commun. pp. 1073–1075. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bond, A. D., Boese, R. & Desiraju, G. R. (2007). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 618–622. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brotons, C., Benamouzig, R., Filipiak, K. J., Limmroth, V. & Borghi, C. (2015). Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs, 15, 113–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bruker (2017). APEX3, SAINT, and SADABS. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Caira, M. R. (1994). J. Chem. Crystallogr. 24, 695–701.

- ChemAxon (2020). MarvinSketch, http: https://chemaxon.com/ (accessed March 2020).

- Cheney, M. L., Weyna, D. R., Shang, N., Mazen, H., Wojtas, L. & Zawarotko, M. J. (2012). J. Pharm. Sci. 100, 2172–2181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Childs, S. L., Stahly, G. P. & Park, A. (2007). Mol. Pharm. 4, 323–338. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clements, M., le Roex, T. & Blackie, M. (2015). ChemMedChem, 10, 1786–1792. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Darwish, S., Zeglinski, J., Krishna, G. R., Shaikh, R., Khraisheh, M., Walker, G. M. & Croker, D. M. (2018). Cryst. Growth Des. 18, 7526–7532.

- DeKornfeld, T. J. (1964). Am. J. Nurs. 64, 60–64. [PubMed]

- Desborough, M. J. R. & Keeling, D. M. (2017). Br. J. Haematol. 177, 674–683. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. (2009). J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 339–341.

- Ferguson, M., Moyano, M. S., Tribello, G. A., Crawford, D. E., Bringa, E. M., James, S. L., Kohanoff, J. & Del Pópolo, M. G. (2019). Chem. Sci. 10, 2924–2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Friščić, T. (2010). J. Mater. Chem. 20, 7599–7605.

- Gisselmann, G., Alisch, D., Welbers-Joop, B. & Hatt, H. (2018). Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Groom, C. R., Bruno, I. J., Lightfoot, M. P. & Ward, S. C. (2016). Acta Cryst. B72, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hademenos, G. (2005). Sci. Teach. 72, 30–34.

- Hernández, J. G. & Bolm, C. (2017). J. Org. Chem. 82, 4007–4019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. & Nanda, A. (2018). Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 667, 54–77.

- Larson, A. C. & Von Dreele, R. B. (2004). GSAS. Report LAUR 86-748. Los Alamos National Laboratory, New Mexico, USA.

- Le Bail, A. (2005). Powder Diffr. 20, 316–326.

- Macrae, C. F., Sovago, I., Cottrell, S. J., Galek, P. T. A., McCabe, P., Pidcock, E., Platings, M., Shields, G. P., Stevens, J. S., Towler, M. & Wood, P. A. (2020). J. Appl. Cryst. 53, 226–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Menges, F. (2016). SpectraGryph Optical Spectroscopy Software, https://www.effemm2.de/spectragryph/down.html (accessed March 2021).

- Montinari, M. R., Minelli, S. & De Caterina, R. (2019). Vascul. Pharmacol. 113, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nagy, S., Fehér, Z., Dargó, G., Barabás, J., Garádi, Z., Mátravölgyi, B., Kisszékelyi, P., Dargó, G., Huszthy, P., Höltzl, T., Balog, G. T. & Kupai, J. (2019). Materials, 12, 3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Newman, A. & Zografi, G. (2020). AAPS PharmSciTech, 21, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oleksyn, B. J. & Serda, P. (1993). Acta Cryst. B49, 530–534.

- O’Neil, M. J. (2006). Editor. The Merck Index – An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, p. 140. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and Co. Inc.

- Pagola, S., Stephens, P. W., Bohle, S. D., Kosar, A. D. & Madsen, S. K. (2000). Nature, 404, 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S., Flack, H. D. & Wagner, T. (2013). Acta Cryst. B69, 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Perlovich, G. L. (2017). CrystEngComm, 19, 2870–2883.

- Punihaole, D., Workman, R. J., Upadhyay, S., Van Bruggen, C., Schmitz, A. J., Reineke, T. M. & Frontiera, R. R. (2018). J. Phys. Chem. B, 122, 9840–9851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Putz, H. & Brandenburg, K. (1999). DIAMOND. Crystal Impact GbR, Bonn, Germany.

- Ramon, G., Davies, K. & Nassimbeni, L. R. (2014). CrystEngComm, 16, 5802–5810.

- Sekhon, B. S. (2012). DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 20, 45.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015a). Acta Cryst. A71, 3–8.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015b). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Spackman, M. A. & Jayatilaka, D. (2009). CrystEngComm, 11, 19–32.

- Stepanovs, D., Jure, M., Kuleshova, L. N., Hofmann, D. W. M. & Mishnev, A. (2015). Cryst. Growth Des. 15, 3652–3660.

- Thipparaboina, R., Kumar, D., Chavan, R. B. & Shastri, N. R. (2016). Drug Discov. Today, 21, 481–490. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Toader, A. M., Zarić, S. D., Zalaru, C. M. & Ferbinteanu, M. (2020). Curr. Med. Chem. 27, 99–120. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Trask, A. V. & Jones, W. (2005). Top. Curr. Chem. 254, 41–70.

- Vane, J. R. & Botting, R. M. (2003). Thromb. Res. 110, 255–258. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vishweshwar, P., McMahon, J. A., Oliveira, M., Peterson, M. L. & Zaworotko, M. J. (2005). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16802–16803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y., Tang, G., Han, Y., Culnane, L. F., Zhao, J. & Zhang, Y. (2016). Opt. Spectrosc. 120, 680–689.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229621008275/ep3016sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229621008275/ep3016Isup2.hkl

Additional information and spectra. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229621008275/ep3016sup3.pdf

CCDC reference: 2003354