Abstract

Background and aims:

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), a deadly malignancy of the bile ducts, can be classified on the basis of its anatomical location into either intrahepatic (iCCA) or extrahepatic (eCCA), each with different pathogenesis and clinical management. There is marginal understanding of the molecular landscape of eCCA and no targeted therapy with clinical efficacy has been approved. We aimed to provide a molecular classification of eCCA and identify potential targets for molecular therapies.

Methods:

An integrative genomic analysis of an international multi-center cohort of 189 eCCA cases was conducted. Genomic analysis included whole-genome expression, targeted DNA-sequencing and immunohistochemistry. Molecular findings were validated in an external set of 181 biliary tract tumors from ICGC.

Results:

KRAS (36.7%), TP53 (34.7%), ARID1A (14%) and SMAD4 (10.7%) were the most prevalent mutations, with ~25% of tumors having a putative actionable genomic alteration according to OncoKB. Transcriptome-based unsupervised clustering helped us define four molecular classes of eCCA. Tumors classified within the Metabolic class (19%) showed a hepatocyte-like phenotype with activation of the transcription factor HNF4A and enrichment in gene signatures related to bile acid metabolism. The Proliferation class (23%), more common in patients with distal CCA, was characterized by enrichment of MYC targets, ERBB2 mutations / amplifications and mTOR signaling activation. The Mesenchymal class (47%) was defined by signatures of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, aberrant TGF-β signaling and poor overall survival. Finally, tumors in the Immune class (11%) had a higher lymphocyte infiltration, overexpression of PD-1/PD-L1 and molecular features associated with a better response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Conclusion:

An integrative molecular characterization identified distinct subclasses of eCCA. Genomic traits of each class provide the rationale for exploring patient stratification and novel therapeutic approaches.

Lay summary:

Targeted therapies have not been approved for the treatment of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. We performed a multi-platform molecular characterization of this tumor in a cohort of 189 patients. These analyses revealed four novel transcriptome-based molecular classes of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and identified ~25% of tumors with actionable genomic alterations, which has potential prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Molecular classification, Targeted therapies, Biomarkers

Introduction:

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is the second most common primary liver malignancy after hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and represents 1% of all neoplasms[1,2]. Although the epidemiology of CCA varies substantially worldwide, its overall incidence is increasing[3]. On the basis of its anatomical origin, CCA has been classified as either intrahepatic (iCCA) or extrahepatic (eCCA), with the second-order bile ducts acting as the separation point[4]. In addition, eCCA can be divided into perihilar (pCCA) and distal (dCCA) depending on whether they originate above or below the cystic duct origin[4]. These subtypes differ not only in their location but also in their etiopathogenesis, with distinct risk factors[3,4], different proposed cells of origin[5] and particular genome aberrations[6,7]. Indeed, previously proposed molecular classifications of CCA (with underrepresentation of eCCA) conducted in the setting of the ICGC[7] and TCGA[8] initiatives have highlighted the crucial role of anatomical location in the biological underpinnings of CCA.

The therapeutic approaches for eCCA are limited. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for early stages, although the risk of recurrence is high (>65%)[9] leading to five-year survival rates around 30%. On the other hand, when the disease is unresectable (>65% of the cases)[10], the standard of practice is gemcitabine and cisplatin, which achieves a median overall survival (OS) of 11.7 months in an unselected population of patients with biliary tract cancer (BTC)[11]. Unfortunately, no molecular targeted therapies have demonstrated survival benefits in eCCA[10], which may be due in part to the limited understanding of the biological mechanisms driving eCCA.

As opposed to eCCA, molecular profiling of iCCA has allowed the discovery of two distinct transcriptome-based classes[12,13]: an “Inflammation class” with predominant induction of immune response pathways and less-aggressive clinical behavior, and a “Proliferation class” with chromosome instability and activation of classic oncogenic pathways that correlate with worse outcome. Moreover, next-generation sequencing uncovered recurrent FGFR2 translocations and IDH1/2 mutations in up to 20% and 15% of iCCA, respectively[6,8,14]. Early clinical trials testing FGFR inhibitors are showing promising results in iCCA patients with FGFR aberrations[15].

No integrative molecular analysis of eCCA, as a single entity, has been provided so far in Western countries. To address this, we performed a comprehensive molecular characterization of a large cohort of clinically annotated eCCA patients (n=189) at both genomic and transcriptomic levels. These analyses exposed major structural genomic alterations in eCCA and revealed four novel molecular classes with potential therapeutic implications.

Materials and methods:

Patients and samples

A total of 189 eCCA patients surgically resected between 1996 and 2016 and with available formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples were retrospectively identified at 7 international institutions: Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, USA (n=50); Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain (n=39); Lausanne University Hospital CHUV, Lausanne, Switzerland (n=36); Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA (n=28); The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, USA (n=15); Vall Hebron, Barcelona, Spain (n=12) and Lenox Hill, New York, USA (n=9). Pathologic diagnosis of eCCA was confirmed by 2 independent liver pathologists (L.R. and S.T.). Forty samples had a paired non-neoplastic bile duct specimen available, which were used for normalization purposes. The study protocol was approved at each center’s Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Whole-genome expression

Total RNA (50ng) from 222 samples (184 tumors and 38 paired non-neoplastic bile ducts) was successfully amplified and prepared with the GeneChip 3’ IVT Pico Kit. Human Genome U219 Array Plate (Affymetrix) was used for whole-genome expression profiling, which is able to interrogate more than 20,000 mapped genes. ArrayQualityMetrics package[16] was utilized to assess reproducibility, identify apparent outlier arrays and compute measures of signal-to-noise ratio. Arrays that were called outliers by more than three criteria (n=2) were excluded from the analysis. The final number of tumors and paired non-neoplastic bile ducts with evaluable whole-genome expression were 182 and 38, respectively.

Affymetrix CEL files were normalized using the ExpressionFileCreator module from GenePattern using the Robust Multi-array Average (RMA) algorithm with background correction as previously reported[17]. Thereafter, in order to prevent potential batch effect associated with the sample’s center of origin, we applied ComBat module from GenePattern[18]. Whole-genome expression of these samples are available in GEO under accession number GSE132305.

Targeted DNA-sequencing

Structural genomic aberrations (mutations and copy number alterations) from a set of 73 genes described to be significantly or recurrently altered in CCA[7,8,14,19,20] were explored by targeted DNA-sequencing using SureSelect XT-HS hybridization capture–based assay (Agilent)[21]. SureDesign application (Agilent) was used for the selection of 22541 probes (463.139kbp) capturing the protein-coding exons of 72 genes and the promoter of TERT.

DNA samples (tumor, n=180; matched non-neoplastic bile ducts, n=17) were normalized to yield 50–250ng of input before shearing on the Covaris instrument. SureSelect XT-HS Library Preparation Kit (Agilent) was used for the preparation of molecular barcoded DNA libraries that were subsequently PCR-amplified using index primers. Successfully prepared DNA libraries (n=192) were hybridized with the custom capture library using SureSelect XT-HS (Agilent) reagents. Captured hybrids on magnetic beads were finally PCR-amplified and combined in pools of 8 libraries for sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq with Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle).

FASTQ files were analyzed with SureCall 4.0. (Agilent) to map short reads against hg19 reference genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm. Prior to alignment and generation of BAM files, read sequences were processed to trim low-quality bases from the ends and duplicate reads were removed. After alignment, samples with low average coverage (<50X) were excluded from the analysis (n=27) since previous studies have shown that the depth of sequencing is critical to the detection of mutations in low purity and high stromal tumors[22]. The resulting samples (tumor, n=150; matched non-neoplastic bile ducts, n=15) were characterized by a mean unique read depth of 312X, which is associated with a 99% sensitivity for the identification of mutant allele frequencies >5%[21].

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was carried out on 3μm-thick FFPE tissue sections after heat-induced antigen retrieval. The primary antibodies used were polyclonal rabbit anti-c-erbB-2 (Dako, #A0485), monoclonal mouse anti-PD1 [NAT105] (Abcam, #ab52587), monoclonal rabbit anti-PD-L1 [28–8] (Abcam, #ab205921), polyclonal rabbit anti-alpha smooth muscle actin (Abcam, #ab5694), monoclonal mouse anti-MLH1 [ES05] (Dako, #IR079), monoclonal mouse anti-MSH2 [G219–1129] (Ventana, #76–5093), monoclonal rabbit anti-MSH6 [SP93] (Ventana, #760–5092), monoclonal mouse anti-CK19 (Roche, #A53-B/A2.26), monoclonal mouse anti-Hep Par 1 [OCH1E5] (Dako, #GA624) and monoclonal rabbit anti-Ki-67 [30–9] (Ventana, #790–4286). Signal was captured using diaminobenzidine (DAB) colorimetric reaction. Immunostaining localization, distribution and intensity were assessed by 3 independent expert pathologists (W.Q.L., C.M. and L.R.) blinded to clinical and molecular features.

External validation

Fastq files of RNAseq from 182 samples of biliary tract cancer (ICGC)[7] (iCCA=122, pCCA=14, dCCA=26, GBC=20) were downloaded from the European Genome-phenome Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/datasets/EGAD00001001076). We correlated the proposed molecular classes of eCCA with clinical variables[7] and non-silent somatic mutations analyzed by whole-exome sequencing and available at the ICGC Data portal (https://dcc.icgc.org/releases/current/Projects/BTCA-JP). Metabolomic data was obtained from an external cohort of hepatobiliary tumors (TIGER-LC)[23] and from eCCA cell lines (CCLE)[24] in order to further characterize the integrative molecular classification. RNAseq data from patients included in the HCC-TCGA (n=362)[25] and Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)-TCGA (n=177)[22] projects were downloaded at https://www.cbioportal.org. Whole-genome expression from our HCC-HEPTROMIC cohort[26] was also used.

Targeted therapies

In order to identify clinical trials reporting objective responses with targeted therapies in BTC we performed a MEDLINE search via PubMed using the keywords “cholangiocarcinoma” and “biliary tract cancer”. Results were limited to “clinical triaI”. Studies recently presented at international meetings were also included despite the full manuscript not being available yet. Targeted therapies evaluated in combination with other systemic treatments or assessed without a biomarker-enrichment design were excluded. Identified drug / biomarker pairs were subsequently categorized according to the OncoKB[27] precision oncology knowledge database in order to rank them in accordance to the level of clinical evidence (Level 1, 2 and 3).

To further uncover therapeutic vulnerabilities associated to eCCA molecular classes, we took advantage of Connectivity Map (https://www.broadinstitute.org/connectivity-map-cmap), a large-scale compendium of functional perturbations in cultured human cells coupled to a gene-expression readout[28]. The top up-regulated genes in each eCCA molecular class were used to identify compounds that elicit opposed expression signatures (tau < −90, indicating that only 10% of reference perturbations were more dissimilar to the query). This concept of reversal of cancer gene expression has been shown to correlate with drug efficacy in preclinical models of breast, liver and colon cancers[29].

Statistical analysis

Associations between categorical variables were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test and Pearson Chi-Square. T-test was used for the comparison of categorical and continuous variables. Correlations between two continuous data were analyzed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R). Kaplan-Meier estimates, log-rank test and univariate and multivariate Cox regressions were used to analyze survival data. OS was defined as the time between surgical resection and death of any cause or lost follow-up. Patients with less than one month of follow-up (n=24) were excluded from the analysis of prognostic factors in order to minimize the effect of surgical complications as a determinant of clinical outcome. All reported p values are two sided and p<0.05 was considered significant. The R software environment (http://www.r-project.org/) with RStudio (www.rstudio.com) and IBM SPSS version 23 (http://www.ibm.com/) were used for all analyses.

Additional detailed methods are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Results:

Clinical-pathological characteristics of the cohort

The study included an international multi-center dataset of 189 eCCA patients from 7 institutions in the US and Europe (Fig. S1). Table 1 includes a detailed description of clinical-pathological characteristics of the cohort. The median age of the patients was 65 years and the male-female ratio was 2:1. Most of the cases lack a known risk factor for eCCA (90%). According to anatomical location, 76% were pCCA and 24% dCCA. All patients were treated with surgical resection. The median tumor diameter was 25 mm (pCCA = 26 mm, dCCA = 19.5 mm; p=0.001), with different pathological TNM stages: from tumors confined to bile ducts to metastatic disease. Significant differences were identified in age, race, cell differentiation and vascular invasion between US and Europe (Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of eCCA patients. Clinical annotation data for all patients and samples included in this study. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; BilIN: Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia; IPNB: intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. Non available in 1(15), 2(30), 3(52), 4(46), 5(27), 6(17), 7(31), 8(21), 9(22), 10(33), 11(34), 12(62), 13(78) and 14(95) patients. *More than one possible.

| eCCA cohort | |

|---|---|

| n=189 | |

| Gender, n (%) 1 | |

| Male | 117 (67) |

| Female | 57 (33) |

| Age, median (range) 1 | 65 (32–86) |

| Race, n (%) 2 | |

| Caucasian | 141 (89) |

| Hispanic | 8 (5) |

| Asian | 8 (5) |

| African | 2 (1) |

| Risk factor, n (%) 3 | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 6 (4) |

| Chronic liver disease (HCV, HBV, alcohol, NASH) | 8 (6) |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) 4 * | |

| Local signs (jaundice/cholangitis) | 115 (80) |

| Systemic signs (weight loss/anorexia) | 43 (30) |

| Asymptomatic | 9 (6) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) 5 * | |

| Hepatic and bile duct resection | 126 (78) |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 51 (31) |

| Liver transplantation | 5 (3) |

| Regional lymphadenectomy | 113 (70) |

| Anatomical subtype, n (%) 6 | |

| Perihilar | 130 (76) |

| Distal | 42 (24) |

| Tumor diameter (mm), median (range) 7 | 25 (5–120) |

| TNM stage AJCC 7th ed. (perihilar), n (%) 8 | |

| I | 5 (4) |

| II | 50 (40) |

| IIIA | 19 (15) |

| IIIB | 36 (29) |

| IVA | 5 (4) |

| IVB | 9 (7) |

| TNM stage AJCC 7th ed. (distal), n (%) 8 | |

| IA | 1 (2) |

| IB | 7 (17) |

| IIA | 14 (33) |

| IIB | 17 (40) |

| III | 2 (5) |

| IV | 1 (2) |

| Resection margins, n (%) 9 | |

| R0 | 107 (64) |

| R1 | 60 (36) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl), median (range) 10 | 3.3 (0.3–73.4) |

| ALT (UI/l), median (range) 11 | 99 (17–715) |

| Albumin (mg/dl), median (range) 12 | 37 (22–49) |

| CA19.9 (UI/ml), median (range) 13 | 142 (0–159600) |

| CEA (ng/ml), median (range) 14 | 2.4 (0–135) |

| Precursor lesions, n (%) | |

| BilIN | 52 (28) |

| IPNB | 18 (9) |

| No | 119 (63) |

| Histological type, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 149 (79) |

| Mucinous | 22 (12) |

| Papillary | 12 (6) |

| Clear cell | 2 (1) |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (1) |

| Signet ring cell | 2 (1) |

| Small cell carcinoma | 1 (1) |

| Cell differentiation, n (%) | |

| G1 | 27 (14) |

| G2 | 136 (72) |

| G3 | 23 (12) |

| G4 | 3 (2) |

| Growth pattern, n (%) | |

| Periductal | 168 (89) |

| Exophytic | 11 (6) |

| Intraductal | 10 (5) |

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 114 (60) |

| No | 75 (40) |

| Vascular invasion, n (%) | |

| Yes | 29 (15) |

| No | 160 (85) |

More than 1 possible.

Landscape of structural genetic alterations in eCCA

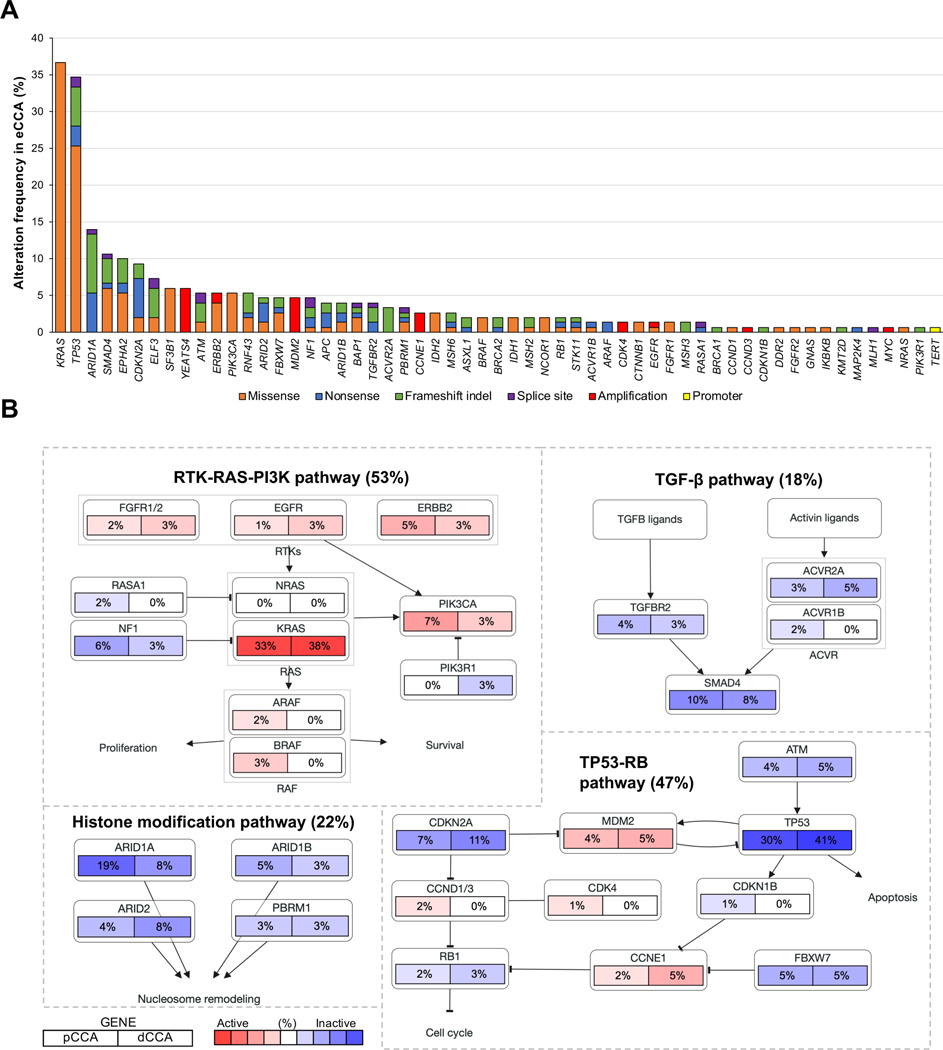

To identify novel driver and potentially druggable alterations unique for eCCA, we assessed the 73 most prevalent structural genetic alterations described in CCA[7,8,14,19,20] (Table S2) by targeted DNA-sequencing in 150 cases. The median number of known or predicted driver mutations in each sample was 2.37 (Fig. S2, Table S3). We identified KRAS (36.7%), TP53 (34.7%), ARID1A (14.0%) and SMAD4 (10.7%) as the most prevalent mutations (Fig. 1A, Fig. S3). Recurrent chromosomal amplifications were observed in YEATS4 (6.0%), MDM2 (4.7%), CCNE1 (2.7%), CDK4 (1.3%) and ERBB2 (1.3%) (Table S4, Fig. S4). These genes converged into four main oncogenic signaling pathways: RTK-RAS-PI3K (altered in 53% of tumors), TP53-RB (47%), histone modification (22%) and TGFβ (18%) (Fig. 1B). Six tumors (4%) had mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MSH2, MLH1 and MSH6), presenting hypermutated profiles compared to the rest of the cohort (median number of mutations = 7 vs 2; p<0.001).

Fig. 1. Landscape of structural genomic alterations in eCCA.

(A) Frequency of recurrent mutations and copy number alterations in eCCA ranked by their prevalence. Color of bars represents the type of genomic alteration: orange: missense; blue: nonsense; green: frameshift indel; purple: splice site; red: amplification; and yellow: TERT promoter mutations. (B) Pathway diagrams showing the percentage of samples from each eCCA anatomical location with structural genomic alterations in genes from RTK-RAS-PI3K, TP53-RB, histone modification and TGFβ pathways. Red and blue mean alterations leading to activation or inactivation of the gene, respectively.

Structural genetic alterations involving oncogenic signaling pathways were not significantly different between pCCA and dCCA (Fig. 1B). However, ERBB2 mutations and amplifications were more prevalent in tumors with papillary histology (33.3% ERBB2 structural genetic alterations in papillary histology vs 3.5% in rest; p=0.007), which is consistent with reports in uterine papillary serous carcinoma[30]. On the other hand, IDH1/2 mutations, frequently observed in iCCA[8,14], were identified only in 4.7% of eCCA. TP53 mutations were associated with a poor OS (HR=1.72, 95% CI 1.01–2.94; p=0.046) (Table S5) and a higher frequency of microvascular invasion (66.7% vs 28.6%; p=0.001), a feature that has also been described in HCC[31].

Actionable genomic alterations and targeted therapies in eCCA

We next sought to determine if recurrent genomic alterations in eCCA could translate into actionable targets. In order to provide an evidence-based list of eCCA molecular aberrations to prioritize the selection of patients for targeted therapies, we used the OncoKB[27] criteria (Table S6).

The only currently approved (Level 1) targeted therapy for use in eCCA is pembrolizumab (PD-1 monoclonal antibody) as a result of the improved outcome shown in tissue-agnostic DNA MMR deficient tumors including CCA[32]. We detected this alteration by IHC in 2% of eCCA (Fig. S5). Robust clinical benefits have been demonstrated in other tumor types (Level 2B) with targeted therapies against molecular aberrations observed in eCCA, such as BRCA1/2 (3%), EGFR (1%), IDH2 (3%) mutations, ERBB2 overexpression (4%) and CDK4 amplifications (1%).

Compelling clinical evidence for a biomarker as being predictive of response to a drug in CCA (Level 3A) has been observed with the inhibition of oncogenic HER2[33,34]. Overall, HER2 structural genomic alterations are present in 5.3% of our eCCA cohort. In addition, despite their low prevalence in eCCA, radiological responses have been described in BTC patients with BRAF mutations (2%) and EGFR amplifications (1.3%) when treated with vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor)[35] and EGFR inhibitors[34], respectively. Finally, IDH1 inhibitors have shown signs of efficacy in early clinical trials of CCA[36] and are currently being investigated in a phase III clinical trial (NCT02989857). However, the low prevalence of IDH1 mutations in eCCA (2%) makes this approach more suitable for iCCA.

In summary, the landscape of eCCA structural genomic alterations reported for the first time in this study provides an initial roadmap for targetable eCCA classification in ~25% of tumors. However, the fact that the more prevalent mutations remain undruggable at this time raises additional challenges for the clinical implementation of this approach.

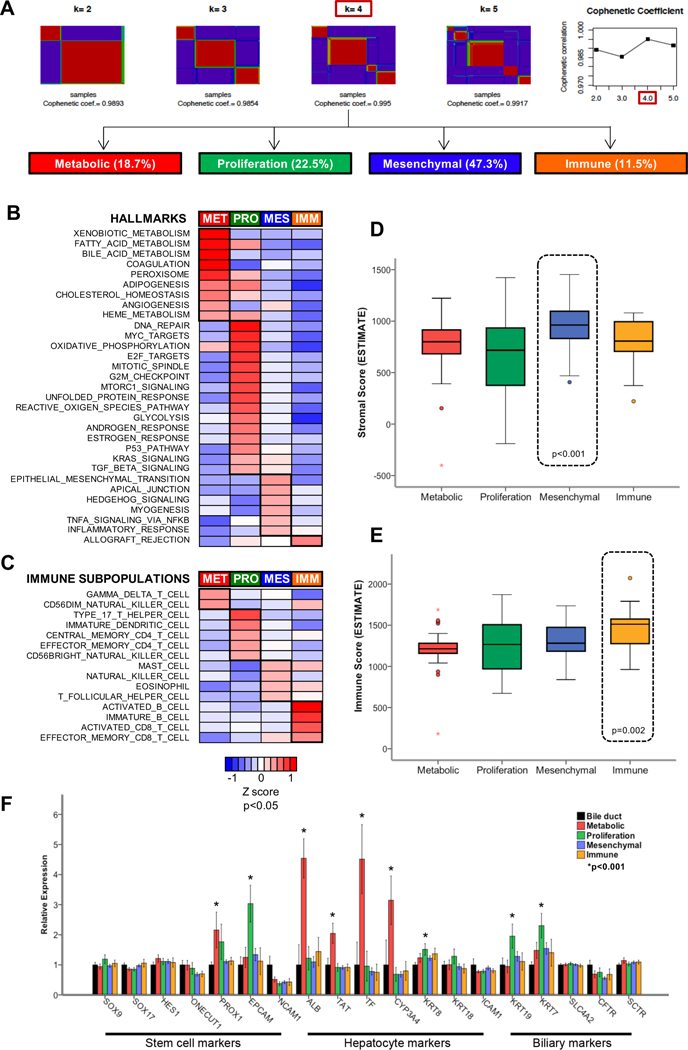

Transcriptome-based molecular classification in four distinct eCCA classes

Unsupervised clustering of whole-genome expression data from 182 eCCA revealed four distinct molecular classes of eCCA (Fig. 2A). We named them on the basis of biological features of tumoral cells and its microenvironment (Fig. 2B–E) into Metabolic (18.7%), Proliferation (22.5%), Mesenchymal (47.3%) and Immune (11.5%). These classes were not associated with any known risk factor of eCCA (primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic liver disease) (Table S7). Herein, we describe the main molecular and clinical-pathological characteristics of each molecular class.

Fig. 2. Molecular classes of eCCA and their biological features defining the tumor and its microenvironment.

(A) Solutions for transcriptome-based unsupervised classification of eCCA using non-negative matrix factorization consensus are shown for k = 2 to k = 5 classes; being four the number of classes with the highest cophenetic coefficient. Heatmaps of: (B) hallmark gene sets from MSigDB collections and (C) immune subpopulations inferred by gene expression of immune metagenes described in The Cancer Immunome Atlas significantly enriched in any of the four molecular classes of eCCA. Single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) was used to obtain the enrichment score, representing the degree of which the genes in a particular gene set are coordinately up- or down-regulated. Samples from the same molecular class were represented with a normalized enrichment score. P values between a specific molecular class and the rest were calculated using T-Test. Box plots representing the estimation of: (D) stromal; and (E) immune compartment in each eCCA molecular class according to virtual microdissection of tumor-microenvironment using gene expression data (ESTIMATE package). P values were calculated using a two-sided T-test. (F) Relative RNA expression of cell of origin markers (stem cell, hepatocyte and biliary) in the four molecular eCCA classes in comparison to normal bile duct. P values were calculated using a two-sided T-test. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Metabolic class

The Metabolic class, including 18.7% of the cases, was dominated by gene expression data suggestive of deregulated metabolism of bile acids, fatty acids and xenobiotics (Fig. 2B). We observed overexpression of genes encoding components of the peroxisome (Fig. 2B), a central regulator of glucose and lipid homeostasis[37]. Unlike the other molecular classes, we identified by virtual microdissection[38] high infiltration of gamma-delta T cells, known intraepithelial lymphocytes involved in the recognition of lipid antigens[39] (Fig. 2C). When we classified eCCA tumors according to previously described molecular subtypes of hepato-biliary malignancies, we found an overlap between the Metabolic class and the CCA good prognosis cluster 1[13] as well as the HCC CTNNB1[40] and S3[41] classes, known to have a retained hepatocyte-like phenotype (Fig. 3A). Indeed, classic hepatocyte markers such as albumin, transferrin and CYP3A4 were overexpressed in the Metabolic class when compared to non-tumoral bile ducts (Fig. 2F). Potential hepatic contamination[8] was not a critical determinant of this phenotype since this class was also observed when excluding liver-specific genes from the transcriptome, as well as when reanalyzing a subset of samples that were surgically collected without any non-tumoral liver counterpart (Fig. S6). The presence of Hep Par 1 (hepatocyte marker) and CK19 (cholangiocyte marker) positive staining in Metabolic tumors (Fig. S7) confirmed the biphenotypic traits of the Metabolic class. HNF4A, a transcription factor involved in the regulation of a broad cluster of hepatocyte genes[42], was the top upstream transcriptome regulator of the Metabolic class’ transcriptome (Table S8). Also, the tubulin deacetylase HDAC6, which has been associated with a pro-tumorigenic function of bile acid receptors in CCA[43], was overexpressed in the Metabolic class (Fig. S8A). Indeed, tubulin inhibitors were predicted to restore in cell lines the aberrant transcriptome identified in Metabolic tumors (Table S9). Overall, the Metabolic class is characterized by disruption of bile acid and fatty acid metabolism, which may favor tumor progression and the acquisition of a HNF4A-driven hepatocyte-like phenotype.

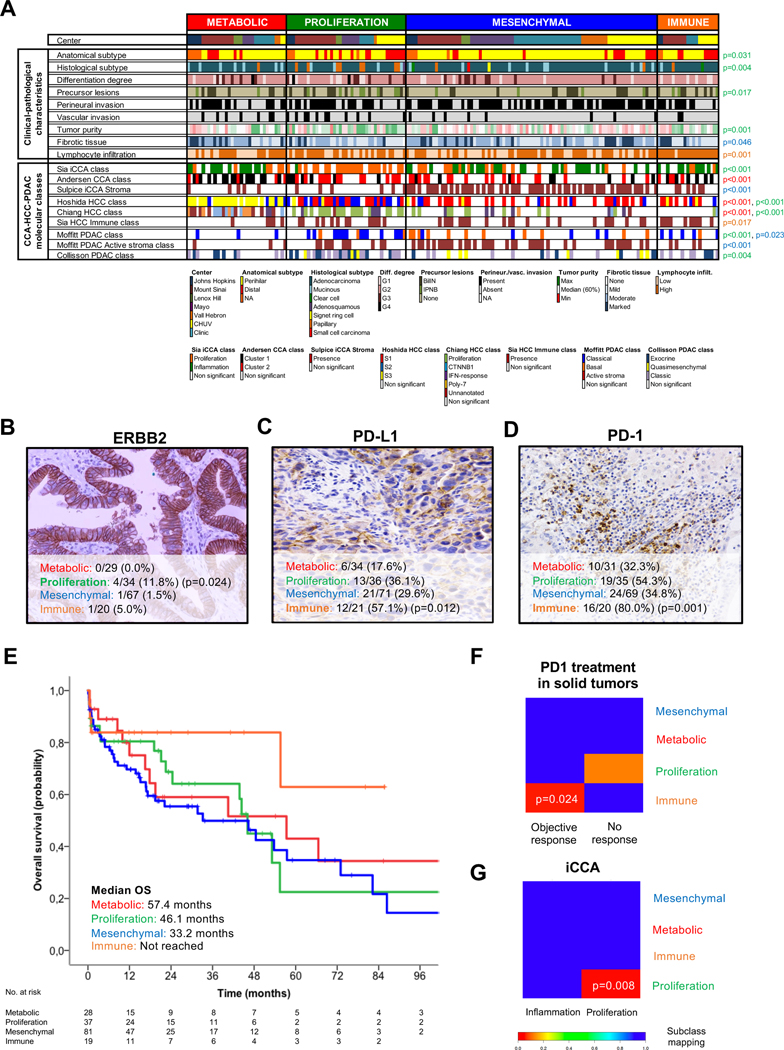

Fig. 3. Associations between eCCA molecular classes and clinical, pathological and molecular traits.

(A) Heatmap representing the clinical-pathological characteristics and previously described CCA-HCC-PDAC molecular classes for each single sample and grouped according to the proposed eCCA molecular classes. Tumor, stromal and immune cellularity was analyzed by pathological evaluation. Molecular classes described in other tumors were inferred using Nearest Template Prediction (NTP). P values were calculated using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and T-test for categorical and continuous data. The color of p value identifies the molecular class (red: Metabolic; green: proliferation; blue: mesenchymal; and orange: immune) that presents significant differences when compared with the rest. Total number of eCCA samples per molecular class with a positive expression of (B) ERBB2 (circumferential membrane staining that is complete, intense, and within > 10% of tumor cells), (C) PD-L1 (membranous staining of tumor cells or stromal cells in >1% over the total number of cells) and (D) PD-1 (cytoplasmic staining of >5% lymphocytes over the total number of intra-tumoral lymphocytes) assessed by IHC. P values were calculated using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test between a specific molecular class and the rest. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves comparing OS in the four molecular eCCA classes. Subclass mapping comparing the transcriptome of the four molecular eCCA classes with external cohorts of: (F) solid tumors including melanoma, non-small cell lung carcinoma and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with anti PD-1 monoclonal antibodies[54]; and (G) iCCA defining proliferation and inflammation classes[12]. P values were obtained after 100 random permutations and Bonferroni correction. CCA: Cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; BilIN: Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia; IPNB: intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct.

Proliferation class

The Proliferation class accounts for 22.5% of the cohort and was defined by the overexpression of MYC targets and the activation of cell cycle signaling (E2F, mitotic spindle and G2M checkpoint) and DNA repair pathways (Fig. 2B). Ki67 staining was significantly higher in the proliferation class (20%) vs other classes (7%) (p<0.001) confirming a higher cell proliferation in the former class (Fig. S9). In addition, CD4+ T cells and specifically T helper 17 cells[44] were the predominant immune cell populations infiltrating the tumor microenvironment of this class (Fig. 2C). The eCCA Proliferation class significantly overlapped with previously described iCCA[12] and HCC[40] proliferation classes (Fig. 3A), and displayed an enrichment of classical oncogenic pathways (Ras/MAPK and AKT/mTOR) (Fig. 2B, Table S8). Cell cycle, CDK and mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus were identified as potential drugs able to revert this phenotype in vitro (Table S9). ERBB2 protein overexpression was a specific trait of these tumors (11.8% in this class vs 1.7% in the rest; p=0.024) (Fig. 3B). Consistently, ERBB2 mutations and amplifications were also more prevalent in the Proliferation eCCA class (17% vs 2%; p=0.003) when compared to the other classes (Fig. S10). Additionally, the eCCA Proliferation class resembled the PDAC classical class[45,46] (Fig. 3A), reproducing the overexpression of adhesion-associated and epithelial genes such as EpCAM and cytokeratins (Fig. 2F). This epithelial-like gene expression profile is translated at the pathological level into a higher prevalence of papillary histology (19.5% vs 2.8%; p=0.004) and its precursor lesion - intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (IPNB) (19.5% vs 6.4%; p=0.017) - which may explain the higher tumor purity observed in the Proliferation class when compared to other classes (67% vs 57%, p=0.001) (Fig. 3A). The Proliferation class included a significantly higher proportion of dCCA tumors (35% of dCCA were Proliferation class vs 18% of dCCA in the remaining three molecular classes; p=0.031) (Fig. 3A). In summary, we report activation of cell cycle, mTOR and ERBB2 as a key feature of the Proliferation class, which underscores a potential novel therapeutic target in a subset of eCCA patients.

Mesenchymal class

The Mesenchymal class, the most prevalent of the four classes (47.3%), was dominated by genomic signals of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Fig. 2B). This has been linked to paracrine tumor-stromal cells interactions associated with aberrant hedgehog signaling activation[47] (Fig. 2B). In line with this hypothesis, TNFα signaling[48], induced mainly by the innate immune system (mast cells, natural killer cells and eosinophils), was enriched in this class (Fig. 2B–C). Macrophages were not significantly associated with any eCCA class. Molecular clusters defining activated stroma in iCCA[49] and PDAC[45] were significantly correlated with the Mesenchymal eCCA class (Fig. 3A). In addition, the cytokine TGF-β1 was the top upstream regulator of the transcriptome deregulation defining this class (Table S8). These results were consistent with the intense fibrotic reaction detected in these tumors upon pathology analysis (Fig. 3A) and in silico gene expression deconvolution (Fig. 2D). The extracellular matrix protein periostin, produced by activated cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and linked to the promotion of CCA cell invasion[47], was the top overexpressed gene defining the Mesenchymal class (Fig. S9B). The overexpression of periostin was independent from the degree of CAFs infiltration, assessed by staining of its surrogate marker α-SMA (Fig. S11), implying that CAF activation more than simply the presence of CAFs dictates the mesenchymal phenotype. Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) inhibitors were identified in cell lines as potential compounds able to counteract Mesenchymal tumors (Table S9). From a clinical perspective, a multivariate analysis with other known clinical-pathological prognostic variables showed that the Mesenchymal class was an independent poor prognostic factor for OS (HR=1.95, 95% CI 1.12–3.40; p=0.018) (Fig. 3E, Fig. S12A, Table S10). This is in agreement with what has been described in PDAC[50] and colorectal cancer[51], where the homologous mesenchymal and basal-like tumors are associated with worse clinical outcomes. In summary, the eCCA Mesenchymal class is defined by EMT, TGF-β signaling activation and a desmoplastic reaction observed in pathological analysis, altogether translating into poor clinical outcomes.

Immune class

The eCCA Immune class (11.5%) was defined by upregulation of adaptive immune response genes (cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and B cells) (Fig. 2C), a feature that may explain the enrichment in allograft rejection hallmark (Fig. 2B). Tumors in this class had similar genomic features as the recently proposed HCC immune class[52] (Fig. 3A). These so-called ‘hot’ tumors displayed marked lymphocytic infiltration in both pathological (Fig. 2A) and transcriptomic analyses (Fig. 2E), when compared to other eCCA molecular classes. However, this T cell tumor infiltration was dysfunctional (Fig. S13), which may explain a mechanism of tumor immune evasion. Indeed, IFN-γ was identified as a key regulator of this class upon upstream transcriptional analysis (Table S8), which has been proposed to predict clinical responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors[53]. Based on that, we assessed PD-1 and PD-L1 status by IHC in the eCCA cohort. Up to 80% and 57% of Immune class tumors had over-expression of PD-1 (>5% of lymphocytes) and PD-L1 (>1% of tumoral or stromal cells), respectively (Fig. 3C–D). These numbers were significantly higher than the rest of the molecular classes (PD-1=80% vs 39%, p=0.001; PD-L1=57% vs 28%, p=0.012). Finally, the transcriptome of the Immune class resembled the expression profile of other solid tumors who responded to PD-1 inhibition (melanoma, non-small cell lung carcinoma and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma)[54] (Fig. 3F). To summarize, the higher lymphocytic infiltration and increased immune checkpoint expression observed in the eCCA Immune class may define a population that could benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors.

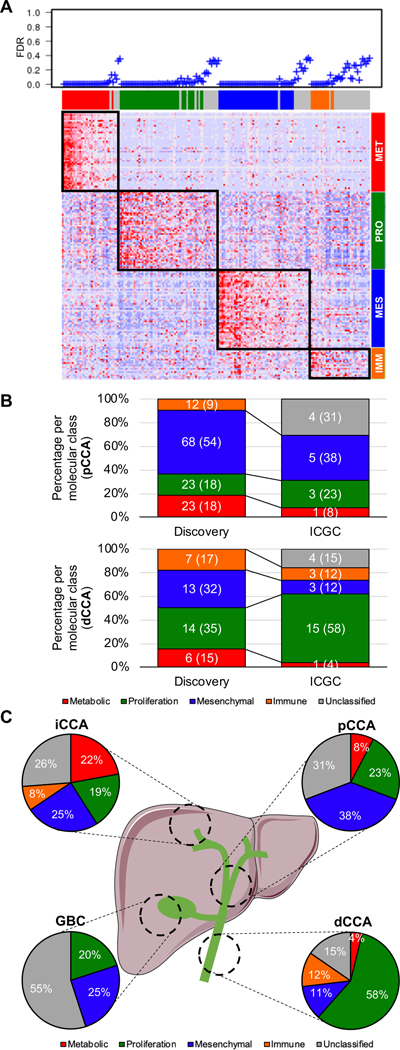

Design of eCCA molecular classifier and external validation

In order to externally validate the above-described eCCA molecular classification, we designed a 174-gene classifier composed of a maximum of 50 genes defining each class that was able to allocate eCCA samples to each of the four molecular classes with a global precision of 86% in our discovery eCCA cohort (Fig. S14, Table S11). The classifier achieved a specificity of 99%, 96%, 97% and 94% for the Metabolic, Proliferation, Mesenchymal and Immune classes, respectively.

Although the eCCA classifier was initially intended for pCCA and dCCA, the low number of publicly available eCCA samples with transcriptome data required the analysis of 181 BTC from different anatomical locations from the ICGC[7] cohort (iCCA=122, pCCA=13, dCCA=26, gallbladder cancer [GBC]=20) (Fig. 4A). We predicted with high confidence (false discovery rate < 0.05) 72% of the external ICGC samples and successfully recapitulated the main molecular traits defining each class (Fig. S15). When we focused on eCCA samples from the ICGC cohort (n=39), we confirmed that dCCA tumors were enriched in the Proliferation class (58% vs 23% in pCCA; p<0.001) (Fig. 4B). Moreover, taking advantage of the paired whole-exome sequencing performed in the ICGC[7] cohort, we validated the higher prevalence of ERBB2 mutations in eCCA samples of the Proliferation class (17% vs 0% among the rest) (Table S12). Finally, ICGC tumors from the eCCA Mesenchymal class also exhibited a trend towards poor outcome in terms of OS (HR=2.94, 95% CI 0.65–13.20; p=0.160) (Fig. S12B).

Fig. 4. External validation of eCCA molecular classifier.

(A) Heatmap showing molecular eCCA class prediction in the ICGC validation cohort using a predefined list of 174 marker genes (eCCA classifier) analyzed by Nearest Template Prediction (NTP). As measure of significance of the prediction for each sample, false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 was selected. (B) Prevalence of eCCA molecular classes for pCCA and dCCA in both discovery and validation (ICGC) cohorts. (C) Distribution of eCCA molecular classes according to anatomical location in the ICGC validation cohort containing 181 BTC. iCCA: Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; pCCA: Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; dCCA: Distal cholangiocarcinoma; GBC: Gallbladder cancer.

A direct comparison of eCCA and our previously described iCCA molecular classes[12] allowed us to identify significant molecular similarities only in the so-called Proliferation classes (Fig. 3G). Despite the observed singularity of eCCA, we inferred the percentage of the four eCCA molecular classes in iCCA, GBC, HCC[25,26] and PDAC[22] to further increase knowledge about molecular disparities among different anatomical locations (Fig. 4C, Fig. S16). Of note, the Metabolic and Immune phenotypes were absent in GBC. On the other hand, Metabolic tumors were more prevalent as we moved more proximal in the intrahepatic biliary tree.

Finally, after applying the eCCA classifier in an external cohort of hepatobiliary tumors (TIGER-LC)[23] and eCCA cell lines[24] with available metabolomic data, we confirmed the aberrant bile acid metabolism discovered in the eCCA Metabolic class (Fig. S17, Fig. S18).

The external validation of the four molecular eCCA classes confirms the cross-validity of the model, independently of either tumors’ anatomical origin or the technology used for transcriptome profiling. Nonetheless, it highlights important molecular differences among different BTCs. The availability of this tool may facilitate the clinical implementation of molecular subtyping in eCCA.

Discussion:

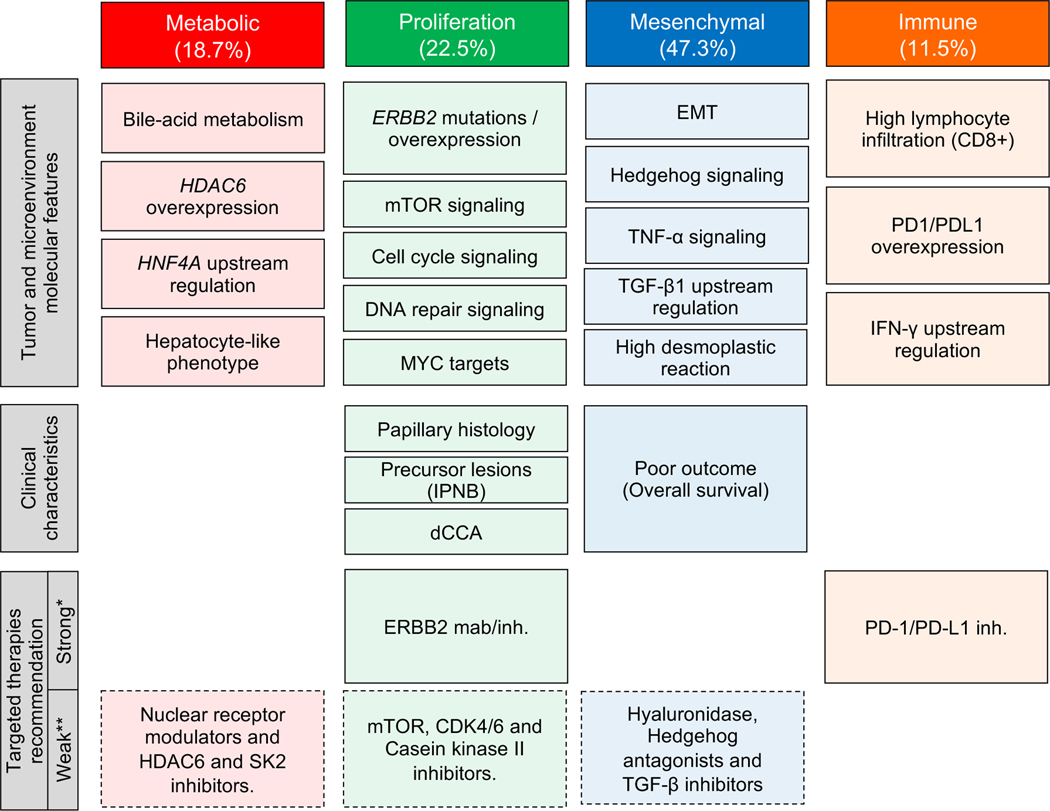

Previous barriers to conducting a molecular characterization of eCCA included the low number of samples analyzed in international cancer genome projects and the inclusion of heterogeneous samples from different BTC subtypes[7,8,19] (e.g. iCCA, GBC). To bridge this knowledge gap, we have herein provided a comprehensive genomic characterization of a large Western cohort of eCCAs and unraveled key biological traits with potential clinical implications. Integrative molecular analysis of 189 clinically-annotated eCCA tumors has identified four molecular classes (Metabolic, Proliferation, Mesenchymal and Immune) with distinct oncogenic fingerprints and histological subtypes (Fig. 5). Furthermore, using targeted DNA-sequencing we have identified KRAS, TP53, ARID1A and SMAD4 as the most frequent genetic alterations in eCCA, with ~25% of tumors displaying at least one putative actionable driver (BRCA1/2, EGFR, ERBB2, CDK4, IDH1/2, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA and MDM2). These data provide a comprehensive portrait of eCCA as a distinct molecular entity and pave the way for a more precise treatment approach.

Fig. 5. Summary of characteristics of eCCA molecular classes.

Schematic representation of the main tumor/microenvironment molecular features and clinical characteristics describing Metabolic, Proliferation, Mesenchymal and Immune classes. In the bottom of the figure, candidate targeted therapies with a potential benefit in each molecular class. *Recommendation of treatment based on molecular data at transcriptomic and protein level. Phase 2/3 clinical trials to investigate these findings should be conducted to confirm the efficacy of the proposed targeted therapies. **Suggested targeted therapies supported by molecular associations at transcriptomic level. Further functional preclinical studies should be conducted prior testing them in the setting of clinical trials. EMT: epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; IPNB: intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct.

Our proposed molecular classification of eCCA characterizes unique traits and classes for this cancer, although it shares molecular features with other gastrointestinal tumors, such as gastric, pancreatic and hepatocellular cancer[55]. Previous large-scale mutational studies have suggested that the main molecular differences among the distinct BTC subtypes consist of alterations in the frequency of driver mutations, rather than different sets of mutated genes[12,14,56]. Here we detected high prevalence of KRAS (36.7%) and TP53 (34.7%) mutations in eCCA when compared to studies conducted in iCCA (Table S2). The identification of FGFR2 translocations and IDH1/2 mutations predominantly in iCCA[14], along with the emerging evidence pointing towards a different cell of origin for iCCAs (mostly derived from trans-differentiation of adult hepatocytes or their progenitor cells)[57] and eCCAs (derived from ductal cells)[58], suggest that eCCA and iCCA are distinct molecular entities. We and others[12,13] have reported two main classes of iCCA, including an “Inflammation class” and a “Proliferation class”, with up to 60% of patients harboring at least one actionable molecular alteration[14]. Interestingly, direct comparison of the molecular fingerprints of the four novel eCCA classes with previously reported classes of iCCA showed overlap only regarding the Proliferation classes. We did not detect any similarities between the Immune class of eCCA and the “Inflammation class” of iCCA. On the other hand, the IDH mutant-enriched subtype of iCCA identified by the TCGA[8], displaying high mitochondrial and low chromatin modifier gene expression, was not detected in the present study. These observations add evidence to further define iCCA and eCCA as two different molecular entities for clinical decision-making purposes. Indeed, the inclusion of only iCCA in clinical trials assessing FGFR and IDH inhibitors[10] in order to increase the success rate of molecular screening epitomizes the biological knowledge achieved during the last decade and confirms the feasibility of testing targeted therapies in less prevalent diseases. Finally, taking advantage of the ICGC cohort including tumors originating from different parts of the biliary tree[7], we could recognize specific distributions of the molecular classes proposed here depending on anatomical location of eCCA: the Proliferation and Immune classes were particularly prevalent in dCCA, whereas Mesenchymal tumors were enriched in pCCA. The deregulated bile-acid metabolism captured in the eCCA Metabolic class -and also noted previously in a subset of primary liver cancers[23]- was frequently inferred in the ICGC iCCA. The hepatocyte-like phenotype observed in Metabolic tumors supports recent advances in cell biology showing that bile duct cells can be converted to functional hepatocytes, suggesting that mutual phenotypic plasticity exists between hepatocytes and bile duct cells[57,59]. GBC presented less homology with the described eCCA classes, highlighting its molecular uniqueness[60]. Overall, these data strengthen the notion that tumor origin within the biliary tree provides a unique portrait of the tumor and its microenvironment that should be considered when designing future clinical trials.

The prognosis of patients with eCCA has remained invariably poor during the last few decades[1], with neither molecular targeted therapies nor immunotherapies recommended for this neoplasm. Phase II trials conducted in BTC assessing everolimus, selumetinib and erlotinib for all comers showed objective responses in only 5–10% of patients[10], highlighting the need to implement biomarker-enrichment clinical trials. On the other hand, the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab obtained a 7% objective response rate in PD-L1 positive BTC[61], indicating suboptimal performance of this biomarker. In this regard, our eCCA molecular profiling highlights potential therapeutic opportunities and establishes the rationale for drug-biomarker co-development that might transform the landscape of clinical trials testing systemic therapies in this disease (Table S13). Moreover, the proposed 174-gene eCCA molecular classifier, once further validated in external cohorts, would represent a framework for clinical implementation of the molecular phenotypes described herein.

Additionally, the four molecular transcriptome-based subclasses were linked with specific treatment strategies. As shown in Fig. 5 we consider that two recommendations of treatment can be derived from our genomic data with high confidence: Firstly, HER2 inhibitors for the Proliferation class based on the aberrant activation of ERBB2 and downstream activation of well-defined oncogenic signaling pathways such as Ras/MAPK and AKT/mTOR. And secondly, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for the Immune class according to the high CD8+ lymphocytic infiltration of these tumors and the presence of IFN-γ signaling that may capture neoantigen immunogenicity. Of course, specific phase 2/3 clinical trials with enrichment designs following these findings should be conducted prior to entering those treatment proposals into the clinical arena. HER2 monoclonal antibodies (trastuzumab and pertuzumab)[34] and pan-HER inhibitors (neratinib, lapatinib and varlitinib)[33] are currently under clinical development in BTC (Table S13). Also, twenty-one clinical trials are testing immune checkpoint inhibitors alone or in combination with other targeted therapies in patients with BTC (Table S13).

Conversely, other molecular treatment strategies suggested in Fig. 5 require confirmation with further preclinical and functional data prior to being tested in the setting of clinical trials. This would be the case of targeting bile acid metabolism with nuclear receptor modulators[62] and inhibitors of the enzyme sphingosine kinase-2 (SK2)[63] in the Metabolic class; exploring anti-proliferative agents such as casein kinase II inhibitors[64] (Fig. S8C) and CDK4/6 inhibitors in the Proliferation class; and blocking the reciprocal communication between stromal cells and cancer cells in the desmoplastic Mesenchymal class with TGFβ inhibitors[65], Hedgehog antagonists[47] or directly degrading stroma with hyaluronidase[66].

On the other hand, tumors within the Proliferation class might derive higher benefit from traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy as observed in the analogous classical PDAC molecular class, whereas the EMT properties observed in the eCCA Mesenchymal class have been associated with a diminished response rate to these agents[67].

In conclusion, our integrative molecular analysis of eCCA provides a better understanding of the molecular landscape of this clinically-challenging neoplasm and identifies novel therapeutic targets. Our study supports the concept that molecular classes, oncogenic drivers and microenvironment of eCCA are intrinsically different to iCCA, which might result in unique precision therapeutic approaches based upon their actionable drivers (~25% for eCCA vs ~50–60% for iCCA). Altogether, these results could have fundamental implications in how clinical trials are designed for patients with BTC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank all patients who have donated their samples for this study. We also thank Cristina Teixido, Anna Enjuanes and the Genomic Core Facility of IDIBAPS for all the support throughout the project. This study has been in part developed at the building Centre Esther Koplowitz from IDIBAPS/CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflict of interest:

J.M.L. is receiving research support from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Eisai Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Ipsen, and consulting fees from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Eisai Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celsion Corporation, Eli Lilly, Roche, Genentech, Glycotest, Nucleix, Can-Fite Biopharma, AstraZeneca, and Exelixis. A.V. reports personal fees from NGM Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Nucleix, Fuji Wako, Guidepoint and Exact Sciences. L.R.R. is receiving research support from Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, BTG International, Exact Sciences, Gilead Sciences, GRAIL Inc., RedHill Biopharma Ltd., TARGET PharmaSolutions and Wako Diagnostics, and is advisory board member of Bayer, Exact Sciences, Gilead Sciences, GRAIL, Inc., QED Therapeutics, Inc. and TAVEC. B.M. reports personal fees from Bayer and Gilead.

Financial support:

R.M. is supported by a FSEOM-Boehringer Ingelheim Grant. D.S. is supported by the Gilead Sciences Research Scholar Program in Liver Disease. C.M. is a recipient of Josep Font grant from Hospital Clinic de Barcelona. R.E.F. is supported by MICINN/MINECO (BES-2017–081286). R.P. is funded by European Commission/Horizon 2020 Program (HEPCAR, Ref. 667273–2). L.B. was supported by Beatriu de Pinós grant from Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR, Generalitat de Catalunya). J.P. is supported by Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red (CIBER)-ISCIII. L.R.R. is supported by The Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation, the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (P30 CA015083), and the Mayo Clinic Hepatobiliary SPORE (P50 CA210964). A.V. is supported by U.S. Department of Defense (CA150272P3) and Tisch Cancer Institute (Cancer Center Grant P30 CA196521). J.M.L. is supported by European Commission (EC)/Horizon 2020 Program (HEPCAR, Ref. 667273–2), EIT Health (CRISH2, Ref. 18053), Accelerator Award (CRUK, AECC, AIRC) (HUNTER, Ref. C9380/A26813), National Cancer Institute (P30-CA196521), U.S. Department of Defense (CA150272P3), Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, Spanish National Health Institute (SAF2016–76390) and the Generalitat de Catalunya/AGAUR (SGR-1358).

References:

- [1].Rizvi S, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma — evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:95–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2016. A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1553–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Banales JM, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Marzioni M, Andersen JB, Invernizzi P, et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;13:261–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Blechacz B, Komuta M, Roskams T, Gores GJ. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8:512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rizvi S, Gores GJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2013;145:1215–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moeini A, Sia D, Bardeesy N, Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM. Molecular Pathogenesis and Targeted Therapies of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2015:291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nakamura H, Arai Y, Totoki Y, Shirota T, Elzawahry A, Kato M, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet 2015;47:1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Farshidfar F, Zheng S, Gingras M-C, Newton Y, Shih J, Robertson AG, et al. Integrative Genomic Analysis of Cholangiocarcinoma Identifies Distinct IDH -Mutant Molecular Profiles. Cell Rep 2017;18:2780–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D, et al. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:663–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Valle JW, Lamarca A, Goyal L, Barriuso J, Zhu AX. New Horizons for Precision Medicine in Biliary Tract Cancers. Cancer Discov 2017;7:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sia D, Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Roayaie S, Ferrer J, Tabak B, et al. Integrative molecular analysis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reveals 2 classes that have different outcomes. Gastroenterology 2013;144:829–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Andersen JB, Spee B, Blechacz BR, Avital I, Komuta M, Barbour A, et al. Genomic and genetic characterization of cholangiocarcinoma identifies therapeutic targets for tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1021–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sia D, Losic B, Moeini A, Cabellos L, Hao K, Revill K, et al. Massive parallel sequencing uncovers actionable FGFR2–PPHLN1 fusion and ARAF mutations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Commun 2015;6:6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Javle M, Lowery M, Shroff RT, Weiss KH, Springfeld C, Borad MJ, et al. Phase II Study of BGJ398 in Patients With FGFR-Altered Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:276–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W. arrayQualityMetrics - A bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics 2009;25:415–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, Battiston C, Tovar V, Sia D, Alsinet C, et al. Combining clinical, pathology, and gene expression data to predict recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1501–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 2007;8:118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jusakul A, Cutcutache I, Yong CH, Lim JQ, Huang MN, Padmanabhan N, et al. Whole-Genome and Epigenomic Landscapes of Etiologically Distinct Subtypes of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 2017;7:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee H, Wang K, Johnson A, Jones DM, Ali SM, Elvin J a, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reveals a long tail of therapeutic targets. J Clin Pathol 2016;69:403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, Wang K, Downing SR, He J, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:1023–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Raphael B, Hruban R, Aguirre A, Moffitt R, Yeh J, Stewart C, et al. Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2017;32:185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chaisaingmongkol J, Budhu A, Dang H, Rabibhadana S, Pupacdi B, Kwon SM, et al. Common Molecular Subtypes Among Asian Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2017;32:57–70.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li H, Ning S, Ghandi M, Kryukov G V., Gopal S, Deik A, et al. The landscape of cancer cell line metabolism. Nat Med 2019;25:850–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ally A, Balasundaram M, Carlsen R, Chuah E, Clarke A, Dhalla N, et al. Comprehensive and Integrative Genomic Characterization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell 2017;169:1327–1341.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Villanueva A, Portela A, Sayols S, Battiston C, Hoshida Y, Méndez-González J, et al. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015;61:1945–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips S, Kundra R, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. OncoKB : A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;1:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Subramanian A, Narayan R, Corsello SM, Peck DD, Natoli TE, Lu X, et al. A Next Generation Connectivity Map: L1000 Platform and the First 1,000,000 Profiles. Cell 2017;171:1437–1452.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen B, Ma L, Paik H, Sirota M, Wei W, Chua MS, et al. Reversal of cancer gene expression correlates with drug efficacy and reveals therapeutic targets. Nat Commun 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Slomovitz BM, Broaddus RR, Burke TW, Sneige N, Soliman PT, Wu W, et al. Her-2/neu overexpression and amplification in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Calderaro J, Couchy G, Imbeaud S, Amaddeo G, Letouzé E, Blanc JF, et al. Histological subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma are related to gene mutations and molecular tumour classification. J Hepatol 2017;67:727–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hyman DM, Piha-Paul SA, Won H, Rodon J, Saura C, Shapiro GI, et al. HER kinase inhibition in patients with HER2-and HER3-mutant cancers. Nature 2018;554:189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Verlingue L, Malka D, Allorant A, Massard C, Ferté C, Lacroix L, et al. Precision medicine for patients with advanced biliary tract cancers: An effective strategy within the prospective MOSCATO-01 trial. Eur J Cancer 2017;87:122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, Faris JE, Chau I, Blay J-Y, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med 2015;373:726–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lowery MA, Abou-Alfa GK, Burris HA, Janku F, Shroff RT, Cleary JM, et al. Phase I study of AG-120, an IDH1 mutant enzyme inhibitor: Results from the cholangiocarcinoma dose escalation and expansion cohorts. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:15_suppl, 4015–4015. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Peters JM, Shah YM, Gonzalez FJ. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:181–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun 2013;4:2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Silva-Santos B, Serre K, Norell H. γδ T cells in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, Peix J, Newell P, Minguez B, et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2008;68:6779–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hoshida Y, Nijman SMB, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet J-P, Chiang DY, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2009;69:7385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Watt AJ, Garrison WD, Duncan SA. HNF4: A central regulator of hepatocyte differentiation and function. Hepatology 2003;37:1249–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gradilone SA, Radtke BN, Bogert PS, Huang BQ, Gajdos GB, LaRusso NF. HDAC6 inhibition restores ciliary expression and decreases tumor growth. Cancer Res 2013;73:2259–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zou W, Restifo NP. TH17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2010;10:248–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Moffitt R a, Marayati R, Flate EL, Volmar KE, Loeza SGH, Hoadley K a, et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet 2015;47:1168–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med 2011;17:500–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sirica AE. The role of cancer-associated myofibroblasts in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Balkwill F. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sulpice L, Rayar M, Desille M, Turlin B, Fautrel A, Boucher E, et al. Molecular profiling of stroma identifies osteopontin as an independent predictor of poor prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2013;58:1992–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Collisson EA, Bailey P, Chang DK, Biankin A V. Molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019: In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reyniès A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015;21:1350–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez-Quetglas I, Kuchuk O, Villacorta-Martin C, Castro De Moura M, et al. Identification of an Immune-specific Class of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Based on Molecular Features. Gastroenterology 2017;153:812–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DR, et al. IFN- γ – related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest 2017;127:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Prat A, Navarro A, Pare L, Reguart N, Galvan P, Pascual T, et al. Immune-Related Gene Expression Profiling After PD-1 Blockade in Non–Small Cell Lung Carcinoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, and Melanoma. Cancer Res 2017;77:3540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bijlsma MF, Sadanandam A, Tan P, Vermeulen L. Molecular subtypes in cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hezel AF, Deshpande V, Zhu AX. Genetics of biliary tract cancers and emerging targeted therapies. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3531–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sia D, Villanueva A, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Liver Cancer Cell of Origin, Molecular Class, and Effects on Patient Prognosis. Gastroenterology 2016;152:745–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wardell CP, Fujita M, Yamada T, Simbolo M, Fassan M, Karlic R, et al. Genomic characterization of biliary tract cancers identifies driver genes and predisposing mutations. J Hepatol 2018;68:959–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Huch M, Gehart H, Van Boxtel R, Hamer K, Blokzijl F, Verstegen MMA, et al. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell 2015;160:299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Li M, Zhang Z, Li X, Ye J, Wu X, Tan Z, et al. Whole-exome and targeted gene sequencing of gallbladder carcinoma identifies recurrent mutations in the ErbB pathway. Nat Genet 2014;46:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ueno M, Chung HC, Nagrial A, Marabelle A, Kelley RK, Xu L, et al. Pembrolizumab for advanced biliary adenocarcinoma: Results from the multicohort, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Ann Oncol 2018;29:(suppl_8): viii205-viii270. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Schaap FG, Trauner M, Jansen PLM. Bile acid receptors as targets for drug development. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Britten CD, Garrett-Mayer E, Chin SH, Shirai K, Ogretmen B, Bentz TA, et al. A phase I study of ABC294640, a first-in-class sphingosine kinase-2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4642–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Siddiqui-Jain A, Drygin D, Streiner N, Chua P, Pierre F, O’Brien SE, et al. CX-4945, an orally bioavailable selective inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, inhibits prosurvival and angiogenic signaling and exhibits antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res 2010;70:10288–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Marté JL, Helwig C, Kang Z, Cao L, Lamping E, Mahnke L, et al. Phase I Trial of M7824 (MSB0011359C), a Bifunctional Fusion Protein Targeting PD-L1 and TGFβ, in Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:1287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Infante JR, Korn RL, Rosen LS, Lorusso P, Dychter SS, Zhu J, et al. Phase 1 trials of PEGylated recombinant human hyaluronidase PH20 in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer 2018;118:153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, Jang GH, Dodd A, Creighton S, et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: Early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:1344–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.