Abstract

This review comprehensively summarizes epidemiologic evidence of COVID-19 in patients with Type 2 diabetes, explores pathophysiological mechanisms, and integrates recommendations and guidelines for patient management. We found that diabetes was a risk factor for diagnosed infection and poor prognosis of COVID-19. Patients with diabetes may be more susceptible to adverse outcomes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection due to impaired immune function and possible upregulation of enzymes that mediate viral invasion. The chronic inflammation caused by diabetes, coupled with the acute inflammatory reaction caused by SARS-CoV-2, results in a propensity for inflammatory storm. Patients with diabetes should be aware of their increased risk for COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Diabetes, Epidemiology, Pathophysiological mechanism, Management, SARS-CoV-2

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, defined as a group of diseases characterized by signs and symptoms of chronic hyperglycemia, is one of the most significant public health challenges worldwide [1]. According to the International Diabetes Federation, there were approximately 463 million adults suffering from diabetes in 2019 [119], and this number is expected to rise to 592 million by 2035 [3]. The disease burden of diabetes has now been raised by the prevalence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which has been continuously increasing to over 169 million confirmed patients and over 3.5 million deaths globally as of 31 May 2021 [119,118]. Early studies have shown that diabetes is a risk factor for the infection and poor prognosis of COVID-19 [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]. With the high prevalence of diabetes worldwide, it is important to comprehensively understand the characteristics, susceptibility, and impact of COVID-19 on patients with diabetes. These studies have become even more important at this moment because many countries are restricting their citizens’ mobility to contain the pandemic, which could affect a large number of patients with chronic diseases, including diabetes, who may need routine disease management. Some researchers have joined the discussion on the consequences of COVID-19 combined with diabetes, but clinical data from many countries around the world have not yet been available. Based on the countries in which such clinical data are available, patients with diabetes who are infected by COVID-19 see a slower/lower recovery rate, longer time of infection, and increased risk of hospitalization. As the epidemic has gradually become a “new normal” around the world, it is worth discussing how to best manage diabetes during these restrictive times.

This review provides a comprehensive understanding of the interaction between COVID-19 and diabetes, including the epidemiological characteristics of patients with COVID-19 and diabetes, determinants of the prognosis, pathophysiological and biological mechanisms underlying the association between COVID-19 and diabetes, and comprehensive patient management. This review would appeal to a broad readership as it would not only provide critical clinical guidance and scientific evidence for virologists, endocrinologists, infectious disease physicians, and respiratory physicians by summarizing relevant mechanisms and professional and authoritative guidance, but also be of great value for family doctors and the general population by synthesizing the suggestions for patients’ self-management and health management in the community or nursing homes.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and literature filtering

We conducted a literature search in the PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Medline, Wanfang, and CQVIP databases on 31 August, 2020. We searched titles or abstracts including “diabetes” and any synonym or related form of “COVID-19”, including “COVID19”, “coronavirus disease 2019”, “coronavirus disease-19”, “2019-nCoV disease”, “2019-nCoV”, “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”, “SARS-CoV-2”, and “SARS2”.

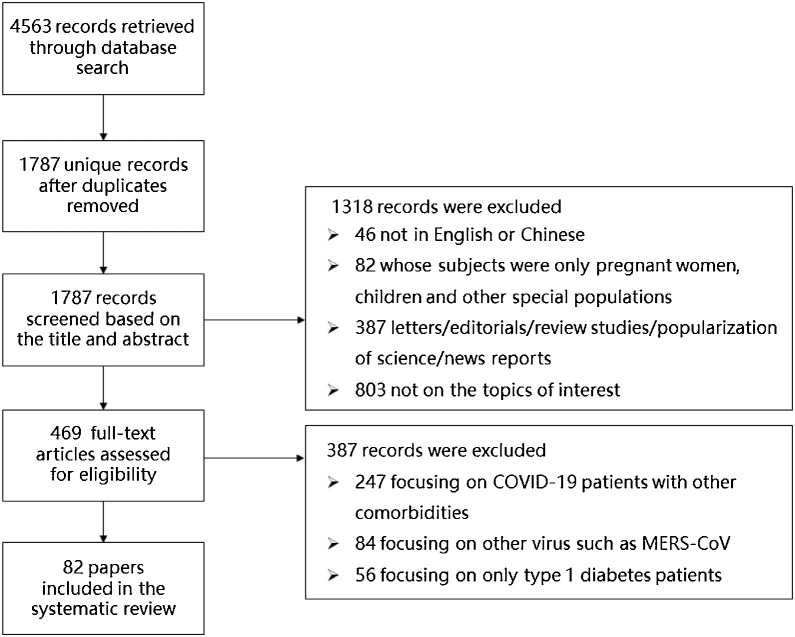

Titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search were independently screened by four reviewers (Y.Y., P.S., H.L., Y.L.) against the study inclusion criteria. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for an evaluation of the full text, also by the same four reviewers independently, with discrepancies resolved by consensus or by a fifth reviewer (S.Y.). The five reviewers jointly determined the final pool of studies included in the review, and four (Y.Y., P.S., H.L., Y.L.) extracted the relevant data.

2.2. Study selection criteria

Our inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study subject: COVID-19 patients with diabetes; (2) study type: clinical research including retrospective studies and prospective cohort studies, fundamental research, and guidelines; (3) article type: peer‐reviewed publications; (4) language: English or Chinese; (5) study topics: epidemiology, pathophysiology or patient management. We excluded studies that met any of the following criteria: (1) studies whose subjects were only pregnant women, children, or other special populations; (2) studies presented as letters, comments, editorials, study/review protocols, review articles, animal studies, mechanistic studies, or case reports; (3) studies focusing on COVID-19 patients with comorbidities other than diabetes; (4) studies focusing on other viruses than SARS-CoV-2, such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. A total of 31 articles were included in this review after the completed filtering process (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study inclusion and exclusion.

3. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 patients with diabetes

Twenty-three out of 82 included studies provided basic epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 patients with diabetes, which were extracted and tabulated (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Prevalence and prognosis of COVID-19 with diabetes.

| First author (year) | Study design | Subjects | Number of participants | Country | Age (Mean ± SD/median) | Males (%) | Prevalence of COVID-19 with diabetes (%) | Prognosis of COVID-19 with diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bello-Chavolla (2020) [23] | Retrospective study | Diagnosed | 61,633 | Mexico | 46.7 ± 15.8 | 57.7 | 18.3 | • Death cases in diabetics/non-diabetics: 21.8%/7.7% |

| • Comorbidities: obesity, hypertension, COPD, CKD, CVD, and immunosuppression | ||||||||

| • Risk factor: with concomitant immunosuppression, COPD, CKD, hypertension and those aged > 65.0 years | ||||||||

| • Death: HR = 3.4, 95% CI: 3.1–3.7 | ||||||||

| Buckner (2020) [106] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 105 | US | 69.0 | 50.5 | 33.3 | • NA |

| Cariou (2020) [90] | Retrospective study | Diagnosed | 1317 | France | 69.8 ± 13.0 | 64.9 | 88.5 | • Comorbidities: heart failure, NAFLD or liver cirrhosis, active cancer, COPD, treated OSA, organ graft and end stage renal failure |

| China CDC (2020) [104] | Retrospective study | Diagnosed | 44,672 | China | NA | 51.4 | 5.3 | • Prevalence of diabetes in death cases: 19.7% |

| Cummings (2020) [117] | Prospective cohort study |

Diagnosed | 257 | US | 62.0 | 67.0 | 36.0 | • Death: HR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1–2.4 |

| Docherty (2020) [116] | Prospective cohort study | Hospitalized | 20,133 | UK | 73.0 | 60.0 | 20.7 | • Death: HR = 1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.1, p = 0.087 |

| Guan (2020) [17] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 1590 | China | 48.9 ± NA | 57.3 | 8.2 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe/non-severe cases: 34.6%/14.3% |

| • Composite endpoints (ICU, or invasive ventilation, or death): HR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.0−2.5 | ||||||||

| Hong (2020) [107] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 98 | South Korea | 55.4 ± 17.1 | 38.8 | 9.2 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe cases: 23.1% |

| Itelman (2020) [108] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 162 | Israel | 52.0 ± 20.0 | 65.0 | 18.5 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe cases: 30.8% |

| Li (2020) [110] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 80 | China | 47.8 ± 19.5 47.5 |

50.0 | 12.5 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe or critical cases: 35.3% |

| • Prevalence of diabetes in mild or moderate cases: 6.3% | ||||||||

| Lian (2020) [109] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 788 | China | NA | 48.4 | 7.2 | • NA |

| Nikpouraghdam (2020) [111] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 2968 | Iran | 55.5 ± 15.2 | 66.0 | 3.8 | • Death cases in diabetics: 9.7% |

| Richardson (2020) [5] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 5700 | US | 63.0 | 60.3 | 33.8 | • ICU cases in died diabetics/non-diabetics: 57.6%/47.2% |

| Singh (2020) [12] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 2209 | China | NA | NA | 10.5 | • NA |

| Singh (2020) [12] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 355 | Italy | NA | NA | 35.5 | • NA |

| Shi (2020) [31] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 1561 | China | 64.0 | 51.0 | 9.8 | • Severe cases in diabetics: 17.6% |

| Sun (2020) [112] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 150 | China | 45.0 ± 16.0 | 44.7 | 6.0 | • NA |

| US CDC (2020) [15] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 1494 | US | NA | NA | 26.7 | • ICU cases in diabetics: 37.1% |

| US CDC (2020) [15] | Retrospective study | Diagnosed | 7162 | US | NA | NA | 10.9 | • Not hospitalized/hospitalized but non-ICU/ICU cases in diabetics: 45.3%/34.4%/20.3% |

| • Prevalence of diabetes in not hospitalized/hospitalized but non-ICU/ICU cases: 6.4%/24.2%/32.4% | ||||||||

| Wan (2020) [113] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 135 | China | 47.0 | 53.3 | 8.9 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe cases: 22.5% |

| Wang (2020) [114] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 138 | China | 56.0 | 54.3 | 10.1 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe cases: 22.2% |

| Zhang (2020) [115] | Retrospective study | Hospitalized | 140 | China | 57.0 | 50.7 | 12.1 | • Prevalence of diabetes in severe cases: 13.8% |

| Zhu (2020) [105] | Retrospective study | Diagnosed | 7337 | China | Diabetics: 62 Non-diabetics: 53 |

47.4 | 13.0 | • Death cases in diabetics/non-diabetics: 7.8%/2.7% |

| • Death: HR = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.1–2.0 (p = 0.005) |

CDC: Center of Disease Control and Prevention; CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HR: hazard ratio; ICU: intensive care unit; NA: not available; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea; UK: United Kingdom; US: United States.

3.1. Prevalence of diabetes among patients with COVID-19

Studies have suggested that COVID-19 is very common in patients with diabetes (Table 1). A survey of 44,672 confirmed cases of COVID-19 by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention showed that diabetes occurred in 5.3% of the cases [10]. Several other studies in China, with sample size ranging from 1561 to 2209, showed that the prevalence of diabetes as a comorbidity with COVID-19 ranged from 9% to 11% [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. More seriously, a study of 5700 COVID-19 patients from the US found that 33.8% of confirmed cases were patients with diabetes [5], which is higher than the national diabetes prevalence of 10.1% among all adults [15]. Additionally, an Italian study concluded that nearly 36% of the 355 COVID-19 patients suffered from diabetes [7]. An increasing number of studies are revealing that patients with diabetes may be more likely to be infected with COVID-19, indicating that diabetes may be a risk factor for COVID-19.

3.2. Poor prognosis of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes

In related studies (Table 1), the poor prognosis of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes is associated with severe illness, ICU treatment, death, and other adverse outcomes [11,13,14,[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Alongside diabetes, there are additional comorbidities that are related to adverse COVID-19 outcomes including, but not limited to chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, immunosuppression, and obesity [[23], [24], [25], [26]]. Among hospitalized patients, cases with diabetes were at higher risk of poor prognosis than cases without diabetes, with odds ratios (OR) varying from 2.0 to 3.7 [13,16,[19], [20], [21], [22]] and relative ratios (RR) from 2.1 to 4.6 [11,18]. According to a Chinese retrospective study of hospitalized patients (n = 1590) and a Mexican study of diagnosed patients (n = 4659), the hazard ratio (HR) reached 1.6 (95% CI: 1.0−2.5) [17] and 3.4 (95% CI: 3.1−3.7) [23], respectively.

Other risk factors in patients with diabetes were shown to be determinants for the poor prognosis of COVID-19, including aging, additional comorbidities (e.g., CKD, COPD, CVD, hypertension, immunosuppression, obesity, dyslipidemia), unhealthy lifestyle, etc. [17,22,23,[27], [28], [29]]. One study showed that the association between diabetes and poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19 was affected by age (p = 0.003) and hypertension (p < 0.001) [30]. As for the risk factors of poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients with diabetes, another retrospective study found that non-survivors were more likely to be older (76.0 vs 63.0 years old), male (71.0% vs 29.0%), and suffering from hypertension (83.9% vs. 50.0%) or cardiovascular disease (45.2% vs 14.8%) (all p < 0.05) [31].

4. Underlying biologic mechanisms for pathophysiological research for COVID-19 and diabetes association

4.1. Impaired immune function

Patients with diabetes suffer increased susceptibility to many common infections, which is attributed to a combination of dysregulated innate immunity and maladaptive inflammatory responses [32]. Besides, the immune glycation damage seen in patients with diabetes also accounts for this increased susceptibility as blood glucose and methylglyoxal (MG) concentration increase in patients with diabetes, and MG is a potent suppressor of myeloid and T-cell immune functions [33]. Myeloid cell expression of surface major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC) decreases in the process of glycation, and some studies have shown that HbA1c > 8.0% decreases the proliferative activity of T helper cells and their response to antigens, which impairs cell-mediated immunity [120]. With the increase of blood glucose, patients with diabetes will experience immunoglobulin glycosylation, disorder of humoral immunity (including impaired complement activation), and decreased cytokine response after stimulation [35]. The increased glycosylation may inhibit lymphocyte and macrophage production of interleukin (IL)-10 which is important for anti-inflammatory response. Additionally, in diabetes, the amount of interferon (IFN)-γ released by T cells and natural killer (NK) cells is reduced, as well as the tumor necrosis factor released by T cells and macrophages[120]. Diabetes inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and intracellular killing of microbes [36]. All of these factors can increase the severity of bacterial infections and viral infections like COVID-19. In addition, studies have shown that diabetes may change glucose concentrations in airway secretion, which has an impact on the infection and replication capabilities of a virus, although this has not been demonstrated for COVID-19 [37].

4.2. Increased inflammatory storm

Studies have shown that when SARS-CoV-2 enters the body, there is a stimulation of the patient's innate immune system, resulting in the release of a large number of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), C–C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)-2, CCL-3, and CCL-5) in the body [38]. As viral infection of SARS-CoV-2 progresses to later stages, the potential for a cytokine storm and acute inflammation increases, therefore worsening the condition [[39], [40], [41]]. Inflammation is closely related to the occurrence and development of diabetes. Inflammatory factors can cause abnormalities in endothelial cell structure and function, which may lead to insulin resistance. At the same time, inflammatory factors may result in structural and functional impairment of islet cells through multiple pathways, which promote β-cell apoptosis, leading to insufficient insulin secretion, and resulting in increased blood glucose [42,43]. This also suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may worsen diabetes or progress prediabetic states to overt diabetes. The shift of CD4+ T cell subsets toward a proinflammatory phenotype (T-helper 1 (Th1), Th17, and CD8+ T cell populations) and the decrease of peripheral unconventional T cells occurs in patients with diabetes, which leads to decreased insulin sensitivity and systemic insulin resistance, so the amplification of cytokine response by SARS-CoV-2 ultimately may enhance this effect [44].

The inflammatory response to COVID-19 also has implications for worsened outcomes in persons with previously diagnosed diabetes. Induction of local and/or systemic low-grade inflammation resulting from the multifactorial activation of innate immunity is also a feature of Type 2 diabetes [45]. Chronic inflammation is an underlying pathological condition in which inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, infiltrate into fat and other tissues and accumulate in individuals with chronic metabolic conditions [46]. In addition, an increased formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in patients with poorly regulated diabetes may be responsible for the increased basal cytokine secretion [35]. It has been posited that infection with SARS-CoV-2 may serve to amplify an already primed cytokine response in patients under these conditions, which exacerbates the cytokine storm that appears to be driving the multi-organ failure and the severe cases of COVID-19 pneumonias and the subsequent death of many patients [43]. Studies have shown that IL-6, a marker of inflammation, was found to be elevated in patients with COVID-19 comorbid with diabetes compared to those without diabetes [47]. Mainly involved in the acute phase inflammatory responses, IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine which is the primary trigger for cytokine storms. It has been suggested that peripheral blood IL-6 levels could be used as an independent factor to predict the progression of COVID-19 [48].

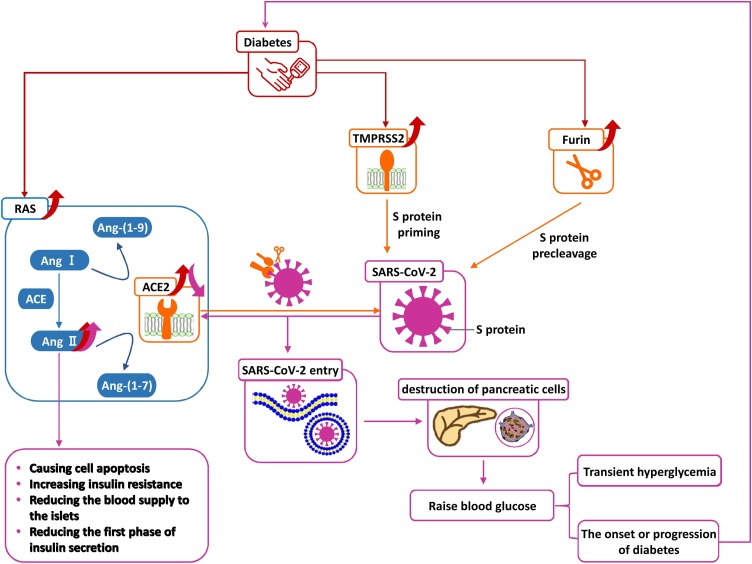

4.3. Functional receptor: ACE2

ACE2 has been identified as the SARS-CoV-2 receptor (Fig. 2 ). Proteases, such as transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), cleave the C-terminal segment of ACE2, particularly residues 697–716, which enhance the S protein-driven viral entry [49]. Proteases such as furin, which cleave the S1 and S2 domain of the spike protein, subsequently release the spike fusion peptide, allowing the virus to enter through an endosomal pathway [36]. Expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 increases in patients with diabetes, and studies have found strong correlations between the expression of the two, which indicates that the genes of the two are expressed in similar cells [50]. Recently, a phenome-wide Mendelian randomization study found that diabetes is causally related to the expression of ACE2. Though the significance of these observations is unclear at present, increased ACE2 expression might predispose patients with diabetes to infection with SARS-CoV-2 [51]. The relationship between furin and diabetes was unveiled when furin levels were found to be elevated several years before the onset of diabetes compared with the control group, and that plasma furin concentration had significantly increased in patients with overt diabetes and cardiovascular disease [52]. The current research results show that the affinity of SARS-CoV-2 to cellular ACE2 was 10–20 times that of SARS-CoV-1 [53], probably due to a furin-like cleavage site (682RRAR/S686) inserted in the S1/S2 protease cleavage site of SARS-CoV-2. In addition, plasmin, which is higher in patients with chronic illnesses such as diabetes, can cleave SARS-CoV-1-S in vitro, but further research on SARS-CoV-2 is needed [[54], [55], [56]]. The cytosolic pH is lower in the presence of diabetes and accompanying comorbid conditions, which may cause the virus to enter the cell by attaching to ACE2 more easily [57]. In the long term, the infection of pancreatic β-cells could also trigger β-cell autoimmunity, further exacerbating an already elevated immune response [47,58].

Fig. 2.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19 with diabetes. Red boxes/lines/arrows represent diabetes and its impacts; purple boxes/lines/arrows represent SARS-CoV-2 and its impacts; orange boxes represent enzymes related to the virus invasion; blue boxes represent the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; TMPRSS2: transmembrane protease serine 2 (for interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

SARS-CoV-2 enters human cells causing a series of respiratory reactions by binding ACE2 through surface proteins in human respiratory and lung tissues, which can infect endocrine pancreas cells via their expression of ACE2. Evidence in diabetic mice demonstrated that ACE2 activity levels were enhanced in the pancreas [59]. In humans, the binding of SARS-CoV-1 to its receptor, ACE2, damages islets and reduces insulin release, which has caused hyperglycemia in people without pre-existing diabetes, although the hyperglycemia could be temporary [51]. Though no similar effect has been reported yet in COVID-19, it suggests the importance of monitoring blood glucose levels in the acute stage of the disease and during the follow up [51,60]. In addition, uncontrolled hyperglycemia may cause potential changes in the glycosylation of ACE2 as well as the glycosylation of the viral spike protein, which may alter both the binding of the viral spike protein to ACE2 and the degree of the immune response to the virus [61].

4.4. Increased RAS expression

Increased blood glucose and the production of glycosylation products in patients with diabetes can increase the expression of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), particularly angiotensin II (Ang II). Studies have shown that many tissues can stimulate dihydronicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity and increase oxidative stress when they are exposed to excessive amounts of Ang II, which results in increased insulin resistance, diabetes complications, and a worse prognosis for COVID-19 infection [[62], [63], [64]]. In addition, Ang II stimulates fibrosis, promotes cell apoptosis, and reduces the islet blood supply, as well as the first phase of insulin secretion, which leads to more serious diabetes [64].

ACE2 converts Ang I to Ang-(1–9), and Ang II to Ang-(1–7). Both of these biologically active downstream peptides contribute to vasodilatory properties, which are further accompanied by antifibrotic, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory effects [65]. ACE2 antagonizes the activation of the classical RAS, and to a certain extent, it can protect islet cells and prevent diabetes [66]. The combination of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2, with the subsequent membrane fusion and the entry of the virus into the cell, leads to downregulation of these receptors, which aggravates cellular damage, hyperinflammation, and respiratory failure [9,67]. The additional ACE2 deficiency after viral invasion might amplify the dysregulation between the ‘adverse’ ACE → Ang II → angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptor axis and the ‘protective’ ACE2 → Ang-(1–7) → Mas receptor axis [67]. Downregulation of ACE2 after viral entry can lead to unopposed Ang II, thus hindering insulin secretion. These factors might contribute to the acute worsening of pancreatic β-cell function and give rise to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) [68], which suggests that patients with diabetes may have a worse prognosis after being infected with SARS-CoV-2. However, whether ACE2 is mechanistically linked to the development of dysglycemia or increased complications in people with diabetes is uncertain [32]. There is evidence that ACE2 expression increases with the use of RAS inhibitors (angiotensin II receptor blockers [ARBs] and ACE inhibitors [ACEi]), which may increase the protective effect to hypertension and diabetes but facilitate the entry of the virus into the host cell and theoretically increase the chances of infection or its severity [12]. However, current studies have not found that the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs increases the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection or the risk of serious consequences in patients with COVID-19 [65,[69], [70], [71]].

4.5. Potential receptor: DPP4

Membrane-associated human dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) is also a functional coronavirus receptor, interacting with the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) through the spike glycoprotein S1b domain [32]. A recent study has shown that although the homology between SARS-CoV-2-S and MERS-CoV-S receptor-binding domains (RBDs) is low, almost all the contacting residues of DPP4 with SARS-CoV-2-S RBD were consistent with those for binding with MERS-CoV-S RBD. This indicates that DPP4 can act as a potential candidate binding target of the SARS-CoV-2-S RBD [72]. One study has shown that the posttreatment HbA1c level is correlated with the baseline levels of CD26/DPP4 expression on T cells and serum sCD26/DPP4 [73], and DPP4 can lead to reduced insulin secretion and abnormal visceral adipose tissue metabolism [74]. Highly selective DPP4 inhibitors have been developed for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes [32], and antibodies directed against DPP4 can inhibit MERS-CoV infection of primary cells [9]. However, the combined mechanism of DPP4 with SARS-CoV-2 and the application of DPP4 inhibitors in patients with COVID-19 needs further study. Moreover, a possible interaction of DPP4 and RAS pathways seems to be plausible, although this has not been fully studied [51].

5. Management

The mechanistic association between diabetes and COVID-19 confirms and explains the epidemiological characteristics to some extent. Given that patients with diabetes are likely to be more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 and may be more prone to poor outcomes, their out-of-hospital health management is now pressed for reinforcement, as well as their in-hospital management, in which telemedicine can play a part (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Practical recommendations for management strategies for patients with diabetes, with diabetes and COVID-19, and seeking assistance via telemedicine.

| Management strategies for… | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Patients with diabetes | • Regularly monitor blood glucose; |

| • Maintain healthy diet and regular exercise as advised by a physician; | |

| • Limit the number of daily contacts to adhere to social distancing guidelines. | |

| Patients with diabetes and COVID-19 | • A full patient evaluation should be performed upon hospital admission to evaluate health status; |

| • Monitor blood glucose levels more frequently during treatment. | |

| Patients with diabetes seeking assistance via telemedicine | • Use the Internet of Things to update doctors on health habits related to diabetes; |

| • Consider scheduling appointments via remote consultation; | |

| • Become familiar with available referral mechanisms and third-party online platforms in case of emergency; | |

| • Consider providing feedback to central data banks for future support in disease management. |

5.1. General measures to promote health in patients with diabetes

5.1.1. Blood glucose control and monitoring

People with diabetes are supposed to control their blood glucose strictly in accordance with daily targets, which requires personalized programs. For example, in elderly patients with other chronic diseases, limited daily activities, mild to moderate cognitive impairment, or those in need of long-term care, the blood glucose control target should be appropriately relaxed in order to prevent hypoglycemia [75]. The frequency of blood glucose monitoring should be determined according to the control of blood glucose and the therapeutic schedule. During the pandemic, when daily life is affected and blood sugar is prone to fluctuation [77]. The International Diabetes Federation suggested that more attention should be given to blood glucose monitoring [122]. If necessary, patients with diabetes can increase the monitoring frequency.

5.1.2. Reasonable diet and moderate exercise

Exercise is recommended as one of the primary management strategies for newly diagnosed patients with Type 2 diabetes. In addition to diet and behavior modification, exercise is an essential component of the prevention and management of diabetes [79]. Epidemiological and biological facts have shown that the acquired disorder of glucose metabolism is often preventable and reversible with healthy living strategies [80]. However, people have been living with another pandemic for many years — physical inactivity (PI) and sedentary behavior (SB). Nowadays, COVID-19 has profoundly changed the world. People have been required to maintain a certain social distance and have been temporarily restricted from travel or going to places for sports activities, such as rehabilitation centers, fitness centers, and parks, which may further affect and accelerate the pandemic of PI/SB [[81], [82], [83]]. At the same time, access to fresh fruits and vegetables could be limited under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic [84,85]. Additionally, alterations in the daily routine influence the dietary intake as well. For instance, people tend to prefer foods that are high in calories, especially those rich in saturated fat and trans-fat [51]. The HbA1c of individuals with diabetes is estimated to increase by 3.68% within 45 days during this pandemic [77]. Therefore, diet and lifestyle adjustments are particularly important during this unusual period, which is also a good opportunity for individuals with diabetes to develop self-management habits. Some suggestions published during the COVID-19 pandemic [75,86,87], although not fully consistent with the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines, include (1) eating a fixed amount of carbohydrates at a fixed time for each meal; (2) eating appropriate carbohydrates, choose high-quality proteins, and properly limit the intake of protein when complicated with renal dysfunction; (3) reducing fat (especially saturated fat) intake and ensure adequate vitamin intake; and (4) ensuring that there is no less than 150 min of medium or low intensity exercise every week.

5.1.3. Social distancing

The American Diabetes Association recommends social distancing as one of the significant precautions which includes avoiding crowds especially in poorly ventilated spaces, all non-essential travel and close contact with people who are ill[123] []. Recent studies showed that the drastically decreased daily contacts caused by the interventions put in place in Wuhan and Shanghai essentially protected people from household interactions, which resulted in a dramatic reduction of COVID-19 transmission [89].

5.2. Measures in patients who have diabetes and COVID 19

5.2.1. Admission evaluation

At the time of admission, the blood glucose and/or HbA1c and urinary ketone will help ascertain the treatment plan of diabetes. Additional factors such as age, nutritional status, food intake, and the presence of other organ dysfunctions and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases should be assessed upon entry. The risk of blood sugar fluctuations and the severity of the patient's condition should be noted [90].

5.2.2. Prevention of severe disease

Based on the guidelines from the UK National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Group [91,92], all of the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should be monitored for blood glucose so that glucose fluctuations can be detected in a timely manner. Patients with a history of diabetes or with blood glucose over 12 mmol/L can be routinely treated for diabetes and monitored regularly and frequently (2–4 times/h). If the blood glucose continues to rise and remains above 12 mmol/L, or oral treatment is impossible, insulin should be considered and the blood glucose control target can be adjusted to 7−12 mmol/L. If treatment for COVID-19-related symptoms is not effective and blood glucose levels are not as expected, blood glucose monitoring should be strengthened (4–6 times/h). When blood glucose exceeds 15 mmol/L, short-acting insulin can be injected subcutaneously as required.

The use of dexamethasone has become a common treatment for severe COVID-19, as it was found to reduce deaths in patients requiring ventilation and oxygen therapy. However, because dexamethasone is a glucocorticoid, patients with COVID-19 comorbid with diabetes should take extra precaution under this medication to prevent ketoacidosis. Patients and clinicians should monitor blood glucose readings more frequently to maintain glycemic control if treated with dexamethasone, or other treatments should be considered for patients with uncontrolled hyperglycemia [93].

The clinical outcome for patients with diabetes and COVID-19 may be more severe or even fatal in the elderly and people with additional comorbidities such as cardiovascular, pulmonary, and kidney diseases [31]. These high-risk patients require special attention and care.

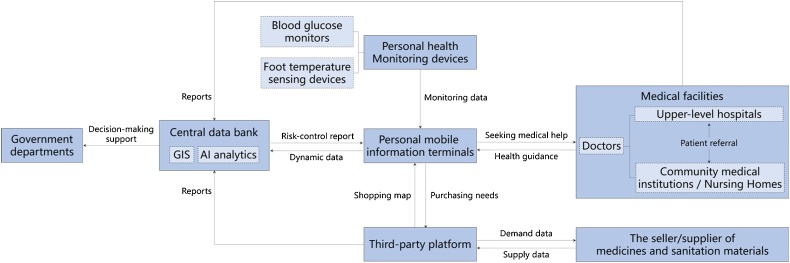

5.3. Increasing use of telemedicine

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a surge in demand for medical services, which has put great pressure on medical institutions; meanwhile many cases are caused by hospital-related transmission [94]. Accordingly, the telemedical information system is now worth further development, so that mild patients can get access to needed medical care while avoiding exposure to acute patients [95]. Such patient-centered systems can protect the patients, the clinicians, and the community through the following five ways (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Telemedical information systems for diabetes management during COVID-19. GIS: Geographic Information Systems; AI: artificial intelligence.

5.3.1. Internet of things (IoT)

The IoT refers to a network comprised of physical objects capable of gathering and sharing electronic information without the need of face-to-face interaction. Using this network, patients with diabetes can upgrade their management plans by connecting their monitoring equipment to the network. For example, the remote blood glucose monitor can not only collect measurements, but also deliver data to parents and caregivers, as well as doctors to provide accurate and frequent up-to-date monitoring of disease progression [96]. Additionally, the foot temperature sensing devices have an early warning system for diabetic foot ulcers in high-risk patients and inform the right player when a problem is imminent [51]. Databases such as the IoT allows doctors to have access to patient information, uploaded by the patient’s device, to provide guidance and monitoring without the need for frequent traditional appointments. Moreover, based on the data collected by the sensors, each patient is competent to be their own expert for health, as web-based programs can provide prescriptions of eating habits, activity patterns, and even drug utilization [97], which has been proved to be a good adjunct to the management of diabetes in many studies and is likely to be effective at the population level [98].

5.3.2. Remote consultation systems

The remote consultation system provides a channel for communication between patients and doctors through text, telephone, or video with the help of electronic medical records and remote monitoring data. For example, the online management data of Internet-Diabetes Co-Care Clinic of Peking University Hospital revealed that the patients managed online showed increased attention to blood glucose monitoring during the pandemic, more frequent interactions with the database, and the average fasting blood glucose and average postprandial blood glucose levels did not change significantly compared with before, indicating little to no progression of the disease. This reflects the effect of telemedicine [99].

5.3.3. Referral mechanisms

The referral mechanism connects community medical institutions, nursing homes, and upper-level hospitals to assist diabetic patients during the pandemic. As an example, grass-roots medical service institutions and community volunteers can be organized to get in touch with patients in need, especially the elderly, and send them to the hospital in a timely manner if necessary [92]. As a gathering environment for high-risk groups, nursing homes should maintain close contact with hospitals, centers for disease control and prevention (CDC), and government departments to ensure adequate supplies and to provide correct care services [100]. Based on the unified digital platform, the grassroots can play an important role in the management of routine patients and the screening and triage of suspected COVID-19 patients [101].

5.3.4. Third-party online platforms

Due to the inconvenience in travel and transportation during the pandemic, a third-party platform of medicines and sanitation materials published a shopping map in order to help the consumer find the nearest online or offline purchase point with diabetes drugs and blood glucose test strips in stock [102]. In addition, the platform provides data support for the seller or the supplier so that the material scheduling can be more reasonable.

5.3.5. Central data banks

The data reported by individuals, medical facilities, and the third-party platforms should be aggregated to the central data bank [103], which is capable of providing decision-making support for the government departments and providing risk-control reports for individuals using geographic information system (GIS) and artificial intelligence (AI) analytics. The above-mentioned telemedicine information system, which can be extended to more chronic disease management, will play a role in this pandemic, as well as in the future.

6. Conclusion

This review reveals that a high proportion of patients with COVID-19 have comorbid diabetes, which could result in a higher risk of poor prognosis. The underlying biologic mechanisms of the association of diabetes and adverse COVID-19 outcomes are the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 to the ACE2 receptor, resulting in acute inflammation and release of cytokines. In patients with diabetes, this further exacerbates an already impaired immune function and increases the risk of inflammatory cytokine storm as viral infection. It is significant for people with diabetes, and even people with other chronic diseases, to enhance the awareness and ability of self-management, particularly during this pandemic when there is a decrease in face-to-face time with doctors. Specifically, with the help of telemedicine systems, which can provide a buffer zone between the prevention of infection and the needs of treatment, there are many ways for a patient to provide up-to-date information to doctors and caregivers so their condition can be monitored remotely. In addition, a global database is necessary, which can strengthen the validity and value of evidence and perform its functions of patient monitoring. Also, given that the prevalence of COVID-19 (also severe COVID-19) among diabetic patients have varied across the studies, a meta-analysis would be useful to examine the differences in the prevalence of COVID-19 among continents or countries/regions, as well as the reasons for these differences.

Declarations of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Donna Ryan (President of the World Obesity Federation and professor Emerita at Pennington Biomedical in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, US) for the critical comments and revisions to improve the quality of this study. We also thank the International Institute of Spatial Lifecourse Epidemiology (ISLE) for the research support.

References

- 1.Zimmet P., Alberti K.G., Magliano D.J., Bennett P.H. Diabetes mellitus statistics on prevalence and mortality: facts and fallacies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016;12:616–622. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guariguata L., et al. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014;103:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson S., et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.264810.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan W.J., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bornstein S.R., et al. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):546–550. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(20)30152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallapaty S. Mounting clues suggest the coronavirus might trigger diabetes. Nature. 2020;583(7814):16–17. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01891-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B., et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020;109:531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh A.K., Gupta R., Misra A. Comorbidities in COVID-19: outcomes in hypertensive cohort and controversies with renin angiotensin system blockers. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J., et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X., Wang S., Sun L., Qin G. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in 2019 novel coronavirus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;164 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cdc Covid- Response Team Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69(13):382–386. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X., et al. Comorbid chronic diseases and acute organ injuries are strongly correlated with disease severity and mortality among COVID-19 patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Research (Wash D C) 2020;2020:2402961. doi: 10.34133/2020/2402961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan W.-J., et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang I., Lim M.A., Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia — a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roncon L., Zuin M., Rigatelli G., Zuliani G. Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127:104354. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian W., et al. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(10):1875–1883. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu L., et al. Risk factors associated with clinical outcomes in 323 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(16):2089–2098. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Z., et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020;81(2):e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bello-Chavolla O.Y., et al. Predicting mortality due to SARS-CoV-2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID-19 outcomes in Mexico. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105(8) doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dou Q., Wei X., Zhou K., Yang S., Jia P. Cardiovascular manifestations and mechanisms in patients with COVID-19. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;31:893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu W., Rohli K.E., Yang S., Jia P. Impact of obesity on COVID-19 patients. J. Diabetes Complications. 2021;35(3):107817. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou K., Yang S., Jia P. Towards precision management of cardiovascular patients with COVID-19 to reduce mortality. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020;63(4):529–530. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyrou I., et al. Sociodemographic and lifestyle-related risk factors for identifying vulnerable groups for type 2 diabetes: a narrative review with emphasis on data from Europe. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2020;20(Suppl 1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12902-019-0463-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gemes K., et al. Burden and prevalence of prognostic factors for severe COVID-19 in Sweden. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020;35(5):401–409. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00646-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luzi L., Radaelli M.G. Influenza and obesity: its odd relationship and the lessons for COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57(6):759–764. doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01522-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y.T., et al. Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 cases and influencing factors in Guangdong province. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2020;41(12):1999–2004. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200318-00378. [Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Q., et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality of COVID-19 patients with diabetes in Wuhan, China: a two-center, retrospective study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1382–1391. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drucker D.J. Coronavirus infections and type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications. Endocr. Rev. 2020;41(3) doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price C.L., et al. Methylglyoxal modulates immune responses: relevance to diabetes. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010;14(6b):1806–1815. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geerlings S.E., Hoepelman A.I.M. Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1999;26(3–4):259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muniyappa R., Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;318:E736–E741. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill M.A., Mantzoros C., Sowers J.R. Commentary: COVID-19 in patients with diabetes. Metabolism. 2020;107:154217. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye Q., Wang B., Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the’ cytokine storm’ in COVID-19. J. Infect. 2020;80(6):607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddiqi H.K., Mehra M.R. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(5):405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanco-Melo D., et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181(5):1036–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Catanzaro M., et al. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5(1):84. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng L., Liu X., Xie F., Ji B. Analysis of influencing factors of hyperglycemia in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and diabetes. Chin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020;36(7):926–929. [Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berchtold L.A., Prause M., Størling J., Mandrup-Poulsen T. Cytokines and pancreatic β-Cell apoptosis. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2016;75:99–158. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasad M., Chen E.W., Toh S.-A., Gascoigne N.R.J. Autoimmune responses and inflammation in type 2 diabetes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020;107(5):739–748. doi: 10.1002/jlb.3mr0220-243r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donath M.Y., Dinarello C.A., Mandrup-Poulsen T. Targeting innate immune mediators in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19(12):734–746. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zbinden-Foncea H., Francaux M., Deldicque L., Hawley J.A. Does high cardiorespiratory fitness confer some protection against pro-inflammatory responses after infection by SARS-CoV-2? Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2020;28(8):1378–1381. doi: 10.1002/oby.22849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maddaloni E., Buzzetti R. Covid-19 and diabetes mellitus: unveiling the interaction of two pandemics. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu F., et al. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127:104370. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan R., et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters M.C., et al. COVID-19 related genes in sputum cells in asthma: relationship to demographic features and corticosteroids. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;202(1):83–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh A.K., Gupta R., Ghosh A., Misra A. Diabetes in COVID-19: prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandez C., et al. Plasma levels of the proprotein convertase furin and incidence of diabetes and mortality. J. Intern. Med. 2018;284(4):377–387. doi: 10.1111/joim.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu F., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7789):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji H.-L., Zhao R., Matalon S., Matthay M.A. Elevated plasmin(ogen) as a common risk factor for COVID-19 susceptibility. Physiol. Rev. 2020;100(3):1065–1075. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barker A.B., Wagener B.M. An ounce of prevention may prevent hospitalization. Physiol. Rev. 2020;100(3):1347–1348. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Millet J.K., Whittaker G.R. Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015;202:120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cure E., Cumhur Cure M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may be harmful in patients with diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):349–350. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katulanda P., et al. Prevention and management of COVID-19 among patients with diabetes: an appraisal of the literature. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1440–1452. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roca-Ho H., Riera M., Palau V., Pascual J., Soler M.J. Characterization of ACE and ACE2 expression within different organs of the NOD mouse. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms18030563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bornstein S.R., Dalan R., Hopkins D., Mingrone G., Boehm B.O. Endocrine and metabolic link to coronavirus infection. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020;16(6):297–298. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brufsky A. Hyperglycemia, hydroxychloroquine, and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(7):770–775. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hotamisligil G.S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Onozato M.L., Tojo A., Goto A., Fujita T., Wilcox C.S. Oxidative stress and nitric oxide synthase in rat diabetic nephropathy: effects of ACEI and ARB. Kidney Int. 2002;61(1):186–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ji X., Xu J., Zhang X., Guo L., Yang J. Expression of ACE-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) in human and rodent pancreata. J. Cap. Univ. Med. Sci. 2007;28(3):278–282. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7795.2007.03.002. [Chinese] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sankrityayan H., Kale A., Sharma N., Anders H.J., Gaikwad A.B. Evidence for use or disuse of renin-angiotensin system modulators in patients having COVID-19 with an underlying cardiorenal disorder. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;25(4):299–306. doi: 10.1177/1074248420921720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng H., Wang Y., Wang G.-Q. Organ-protective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its effect on the prognosis of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(7):726–730. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chee Y.J., Ng S.J.H., Yeoh E. Diabetic ketoacidosis precipitated by Covid-19 in a patient with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;164 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.South A.M., Tomlinson L., Edmonston D., Hiremath S., Sparks M.A. Controversies of renin-angiotensin system inhibition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020;16(6):305–307. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reynolds H.R., et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(25):2441–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bean D.M., et al. ACE-inhibitors and Angiotensin-2 Receptor Blockers are not associated with severe SARS-COVID19 infection in a multi-site UK acute Hospital Trust. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020;22(6):967–974. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bohm M., Frey N., Giannitsis E., Sliwa K., Zeiher A.M. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its implications for cardiovascular care: expert document from the German Cardiac Society and the World Heart Federation. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020;109(12):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01656-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee S.A., et al. CD26/DPP4 levels in peripheral blood and T cells in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(6):2553–2561. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iacobellis G. COVID-19 and diabetes: can DPP4 inhibition play a role? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;162 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ji L., Li G., Gong Q., Zhu Y. Disease management and emergency response guidelines for elderly diabetic patients during COVID-19 outbreaks. Chin. J. Diabetes. 2020;28(1) [Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghosal S., Sinha B., Majumder M., Misra A. Estimation of effects of nationwide lockdown for containing coronavirus infection on worsening of glycosylated haemoglobin and increase in diabetes-related complications: a simulation model using multivariate regression analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kirwan J.P., Sacks J., Nieuwoudt S. The essential role of exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2017;84(7 Suppl 1):S15–s21. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84.s1.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Means C. Mechanisms of increased morbidity and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals with diabetes: what this means for an effective management strategy. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jia P. A changed research landscape of youth’s obesogenic behaviours and environments in the post-COVID-19 era. Obes. Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1111/obr.13162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jia P., et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on activity patterns and weight status among youths in China: the COVID-19 Impact on Lifestyle Change Survey (COINLICS) Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2021;45(3):695–699. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-00710-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang S., et al. Obesity and activity patterns before and during COVID-19 lockdown among youths in China. Clin. Obes. 2020;10(6) doi: 10.1111/cob.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jia P., et al. Changes in dietary patterns among youths in China during COVID-19 epidemic: the COVID-19 impact on lifestyle change survey (COINLICS) Appetite. 2021;158 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu B., et al. Impacts of lockdown on dietary patterns among youths in China: the COVID-19 Impact on Lifestyle Change Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(11):3221–3232. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020005170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hussain A., do Vale Moreira N.C. Clinical considerations for patients with diabetes in times of COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):451–453. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bo F. Management of patients with diabetes in epidemic of COVID-19. J. Tongji Univ. (Med. Sci.) 2020;41(1):1–4. [Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang J., et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;368(6498):1481–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cariou B., et al. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1500–1515. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sinclair A., et al. Guidelines for the management of diabetes in care homes during the Covid-19 pandemic. Diabet. Med. 2020;37(7):1090–1093. doi: 10.1111/dme.14317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rayman G., et al. Guidelines for the management of diabetes services and patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabet. Med. 2020;37(7):1087–1089. doi: 10.1111/dme.14316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rayman G., et al. Dexamethasone therapy in COVID-19 patients: implications and guidance for the management of blood glucose in people with and without diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2021;38(1) doi: 10.1111/dme.14378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang N., et al. Clinical characteristics and chest CT imaging features of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Eur. Radiol. 2020;30(11):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06955-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang S., Yu W., Jia P. Telemedicine: a promising approach for diabetes management — where is the evidence. J. Diabetes Complications. 2021;35(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lanzola G., et al. Remote blood glucose monitoring in mHealth scenarios: a review. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2016;16(12) doi: 10.3390/s16121983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Buch V., Varughese G., Maruthappu M. Artificial intelligence in diabetes care. Diabet. Med. 2018;35(4):495–497. doi: 10.1111/dme.13587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hou C., Carter B., Hewitt J., Francisa T., Mayor S. Do mobile phone applications improve glycemic control (HbA1c) in the self-management of diabetes? A systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE of 14 randomized trials. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):2089–2095. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ang L.I., Xiao B., Junqing Z. Reflection on diabetes management from the new coronavirus pandemic situation. Chin. J. Diabetes. 2020;28(3):180–184. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-6187.2020.03.005. [Chinese] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gordon A.L., et al. Commentary: COVID in care homes-challenges and dilemmas in healthcare delivery. Age Ageing. 2020;49(5):701–705. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li X., et al. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10239):1802–1812. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stoian A.P., Banerjee Y., Rizvi A.A., Rizzo M. Diabetes and the COVID-19 pandemic: how insights from recent experience might guide future management. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2020;18(4):173–175. doi: 10.1089/met.2020.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu Y., Wu S., Qin M., Jiang W., Liu X. The prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities in COVID-19, SARS and MERS: pooled analysis of published data. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020;9(17) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2020;41:145–151. [Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhu L., et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31(6):1068–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Buckner F.S., et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 105 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Seattle, Washington. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(16):2167–2173. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hong K.S., et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 98 patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Daegu, South Korea: a brief descriptive study. Yonsei Med. J. 2020;61(5):431–437. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2020.61.5.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Itelman E., et al. Clinical characterization of 162 COVID-19 patients in Israel: preliminary report from a large tertiary center. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2020;22(5):271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lian J., et al. Analysis of epidemiological and clinical features in older patients with corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) out of Wuhan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(15):740–747. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li D., et al. Clinical characteristics of 80 patients with COVID-19 in Zhuzhou City. Chin J Infec Contl. 2020;19(3):227–233. doi: 10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20206514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nikpouraghdam M., et al. Epidemiological characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients in IRAN: a single center study. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sun C., Zhang X.B., Dai Y., Xu X.Z., Zhao J. Clinical analysis of 150 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in Nanyang City, Henan Province. Chin. J. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2020;43(6):503–508. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200224-00168. [Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wan S., et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(7):797–806. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang D., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang J.J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1730–1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Docherty A.B., et al. Features of 20133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cummings M.J., et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10239):1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/. (Accessed 31 May 2021).

- 119.The International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes facts & figures, 2020. https://www.idf.org/aboutdiabetes/what-is-diabetes/facts-figures.html. (Accessed 12 Jan 2020).

- 120.Klekotka Barbara Klekotka, et al. The etiology of lower respiratory tract infections in people with diabetes. Pneumonol. Alergol. Pol. 2015;83(5):401–408. doi: 10.5603/PiAP.2015.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.The International Diabetes Federation. What should people with diabetes know and do?, 2020. https://www.idf.org/aboutdiabetes/what-is-diabetes/covid-19-and-diabetes/1-covid-19-and-diabetes.html. (Accessed 27 Aug 2020).

- 123.the American Diabetes Association. Take Everyday Precautions. https://www.diabetes.org/coronavirus-covid-19/take-everyday-precautions-for-coronavirus. (Accessed 8 Sep 2020).