ABSTRACT

Objectives:

The Health Sciences Evidence-Based Practice (HS-EBP) questionnaire was recently developed for measuring five constructs of evidence-based clinical practice among Spanish health professionals by applying content and construct validity investigation. The current study aims to undertake a cross-cultural adaptation of the HS-EBP into Japanese and to investigate the internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the Japanese HS-EBP among undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies.

Methods:

Cross-cultural adaptation was undertaken by following Beaton’s five-step process. Subsequently, the Japanese HS-EBP test–retest reliability was assessed with a 2-week interval. Participants were recruited from among third and fourth grade undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies with clinical training experience.

Results:

Pilot testing included 30 participants (11 nursing students, 11 physical therapy students, 8 occupational therapy students). Consequently, we developed the Japanese HS-EBP to be understandable for undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies. Data from 52 participants who completed test–retest reliability questionnaires demonstrated adequate test–retest reliability in the total scores of Domains 1, 3, 4, and 5 [intraclass correlation coefficients were (ICC)=0.74, 0.70, 0.75, and 0.74, respectively]; the exception was Domain 2, which had an ICC of 0.66. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was adequate for Domains 1–5, for which α was 0.87, 0.94, 0.86, 0.93, and 0.95, respectively.

Conclusions:

This study developed the Japanese version of HS-EBP and provided preliminary evidence of adequate internal consistency and test–retest reliability in most domains for undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies.

Keywords: attitude, behavior, guideline, questionnaire, rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

The importance of evidence-based practice (EBP) is recognized by healthcare professionals worldwide, and many tools exist to evaluate its adherence and compliance. A recent systematic review found that no measure provided adequate construct validity.1) Based on the five steps of EBP processes,2) the five-domain Health Sciences EBP (HS-EBP) questionnaire was established to evaluate adherence to, and compliance with, EBP among Spanish health professionals. The HS-EBP was developed by applying content validity investigation using the Delphi technique3) and statistical examination for the construct validity.4) Criterion-related and convergent validity of the HS-EBP has also been confirmed with other measures such as dispositional resistance to change and intrinsic motivation.4)

Cross-cultural adaptation of the HS-EBP has been initiated worldwide. For example, in the Chinese version, preliminary evidence of the content validity has been established. The five-factor structure and adequate internal consistency have been confirmed among nurses in Taiwan.5) However, the Japanese version has not yet been developed, and its test–retest reliability has not been examined in languages other than Spanish.

Regarding EBP in Japanese rehabilitation medicine, Fujimoto et al.6) reported that most physical therapists recognized its importance (83.3% of the 384 participants) and usefulness for clinical decision-making (77.1%). However, only 11% of the participants reported a history of EBP education. In nursing, only 29% of 472 nurses in two university-affiliated hospitals in Tokyo reported a history of EBP.7) Therefore, facilitating EBP education is necessary in undergraduate and postgraduate rehabilitation medicine training in Japan. The HS-EBP questionnaire can be used as a useful training guide.

The current study aims to undertake a cross-cultural adaptation of the HS-EBP questionnaire into Japanese and to investigate the internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the Japanese HS-EBP among undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

The Institutional Research Committee of Saitama Prefectural University approved this study (#20011), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant before data was collected. First, approval for translation of the HS-EBP into Japanese was obtained from the original developer, current coauthor (JCF). Cross-cultural adaptation was undertaken based on the five steps of the Beaton guidelines8): (1) forward translation (two independent versions), (2) synthesis of the two translations, (3) backward translation (two independent versions), (4) expert committee review, and (5) pilot testing. Subsequently, the test–retest reliability of the HS-EBP was assessed.

Cross-cultural Adaptation

For the forward translations, two Spanish–Japanese bilingual translators (YK and KY) independently translated the HS-EBP into Japanese. One translator was a physical therapist who was aware of the aims of the HS-EBP. The other was a professional Spanish translator, not a healthcare provider, who was unaware of the aims of the HS-EBP. In the synthesis meeting to conflate the two forward translations, a combined Japanese draft was developed through discussions among the two forward translators and a current author (HT). Modifications to ensure semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalences were recorded.8) In the backward translation, the combined Japanese draft was then translated into Spanish independently by two professional translators (HU and SN) who were not healthcare providers and were unaware of the aims of the HS-EBP. An expert committee review was held with eight members, namely, the translators of the forward and backward translations and four current coauthors (HT, KK, HC, and YH). Finally, a provisional draft questionnaire to be assessed by pilot testing was reviewed by the developer to confirm its conceptual equivalences to the original. For pilot testing, third and fourth grade undergraduate students (n=30) of nursing and physical and occupational therapies with clinical training experience were recruited in March 2021 by advertisements placed in Saitama Prefectural University, Saitama, Japan. Data collection was executed through online survey (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, CA, USA). After the participants’ demographic data (age, sex, grade, and discipline) were gathered, they were asked, “Did you understand the sentence?” The participants rated their understanding of each item, including the instructions, on a five-point numerical rating scale: 1=”I could not understand the sentence at all” and 5=”I understood it completely.”9) For items with a score of <4, reasons for modification and suggestions were requested. Considering these suggestions, the items were modified without changing their meaning by four coauthors (HT, KK, HC, and YH). Appendix1 shows the resulting Japanese HS-EBP questionnaire, with the URL of an English version of the HS-EBP for reference. The details of the point-by-point modifications of the draft Japanese HS-EBP are shown in Appendix 2.

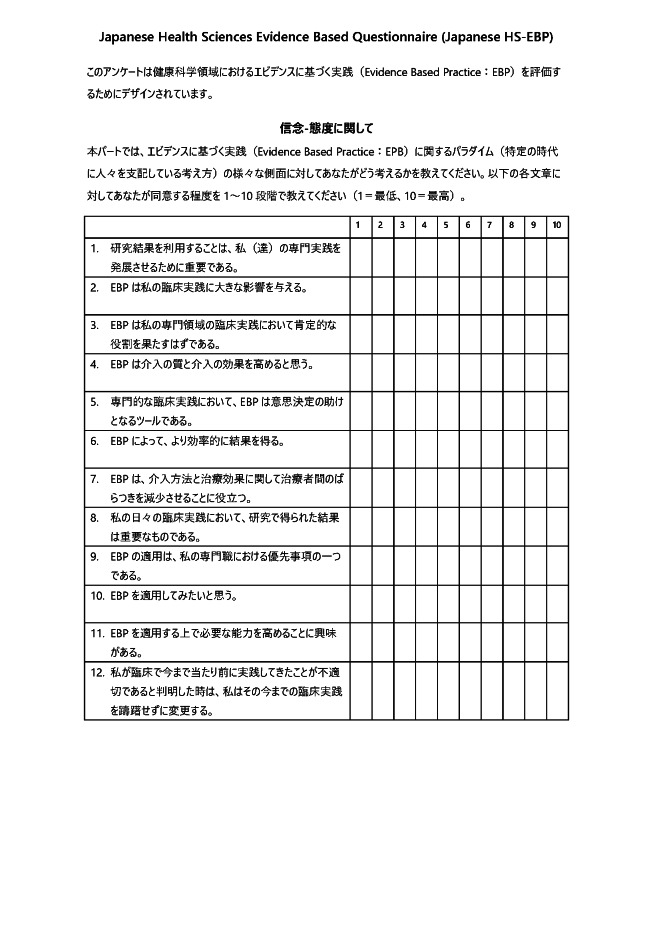

Appendix 2. Modifications made as part of the translation processes and pilot testing of the Japanese Health Sciences Evidence-Based Practice (HS-EBP) questionnaire.

| English HS-EBP* | Modifications in the translation processes | Modifications in the consensus meeting with four coauthors after pilot testing | Japanese HS-EBP |

| The questionnaire you are about to answer is designed to collect information on the use of Evidence Based Practice in Health Sciences in Spain. | Expressions were shortened to enhance readability. For the purpose of generalizability, “Spain” was omitted. To enhance readability, the abbreviation “EBP” was used because “Evidence Based Practice” was repeatedly used. | このアンケートは健康科学領域におけるエビデンスに基づく実践(Evidence Based Practice: EBP)を評価するためにデザインされています。 | |

| Domain 1 (Beliefs–Attitude) This part of the questionnaire aims to find out your OPINION concerning different aspects related to the paradigm of Evidence Based Practice. Rate on a scale of 1 to 10 the level of agreement you have with the following statements (where 1 corresponds to the lowest and 10 the highest). |

The word “paradigm” was considered difficult for students to understand; consequently, an explanation was given in parentheses. | MINOR (n=6) | 信念-態度に関して 本パートでは、エビデンスに基づく実践(Evidence Based Practice: EPB)に関するパラダイム(特定の時代に人々を支配している考え方)の様々な側面に対してあなたがどう考えるかを教えてください。以下の各文章に対してあなたが同意する程度を1∼10段階で教えてください(1=最低、10=最高)。 |

| Item 1–1. Using results from research is important for the development of my/our professional practice. | 研究結果を利用することは、私(達)の専門実践を発展させるために重要である。 | ||

| Item 1–2. EBP has a great impact on my individual practice. | “Practice” was translated as “clinical practice” throughout the questionnaire as it was considered more natural to say “CLINICAL practice” than “practice” as far as EBP is concerned in Japanese. | NO CHANGE (n=2) | EBPは私の臨床実践に大きな影響を与える。 |

| Item 1–3. EBP must play a positive role in my professional practice. | MINOR (n=1) | EBPは私の専門領域の臨床実践において肯定的な役割を果たすはずである。 | |

| Item 1–4. I consider EBP improves the quality and results of interventions. | MINOR (n=2) | EBPは介入の質と介入の効果を高めると思う。 | |

| Item 1–5. In professional practice, EBP is a helpful tool for decision-making. | 専門的な臨床実践において、EBPは意思決定の助けとなるツールである。 | ||

| Item 1–6. EBP involves getting more efficient results. | EBPによって、より効率的に結果を得る。 | ||

| Item 1–7. EBP helps us care for people in the same way and with the same efficiency. | To enhance readability in Japanese, expressions were rephrased to “EBP results in the reduction of variability between clinicians in terms of management method and effectiveness”. | NO CHANGE (n=1) | EBPは、介入方法と治療効果に関して治療者間のばらつきを減少させることに役立つ。 |

| Item 1–8. I consider results from research important for my daily practice. | MINOR (n=2) | 私の日々の臨床実践において、研究で得られた結果は重要なものである。 | |

| Item 1–9. Applying EBP is among my professional priorities. | NO CHANGE (n=1) | EBPの適用は、私の専門職における優先事項の一つである。 | |

| Item 1–10. I consider it motivating to apply EBP. | EBPを適用してみたいと思う。 | ||

| Item 1–11. I am interested in improving the necessary competencies to apply EBP. | EBPを適用する上で必要な能力を高めることに興味がある。 | ||

| Item 1–12. I am willing to change the routines of my practice when these prove inadequate. | MINOR (n=5) | 私が臨床で今まで当たり前に実践してきたことが不適切であると判明した時は、私はその今までの臨床実践を躊躇せずに変更する。 | |

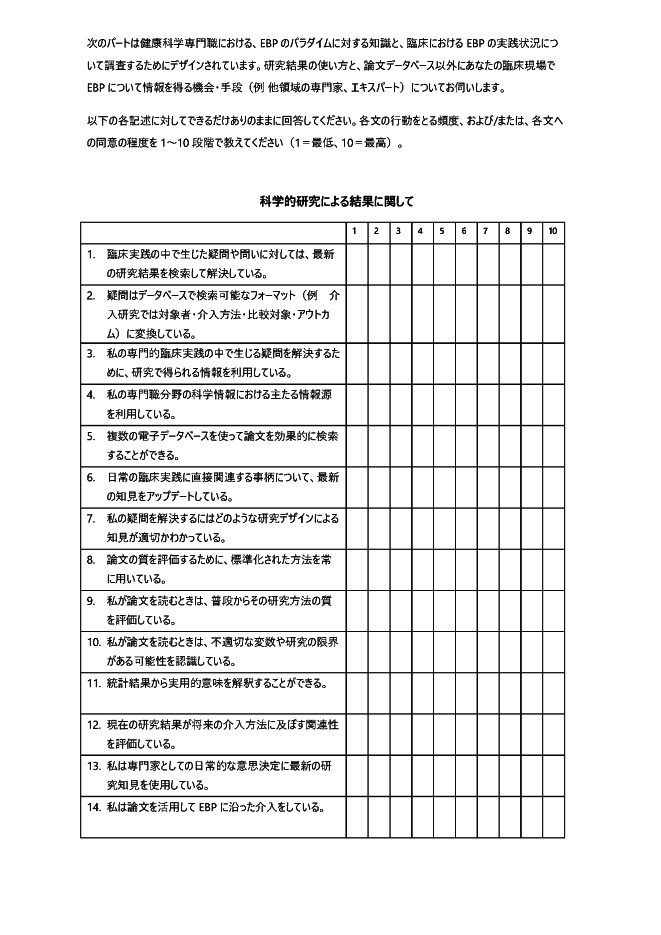

| Domain 2 (Results of scientific research) The following parts of the questionnaire are designed to gather information regarding knowledge–skills and especially concerning the use of evidence based practice among Health Science professionals. In this we are therefore especially interested in the USE you make of scientific evidence and the different sources of information available in your practice. So, we ask you to try to answer the different statements below as sincerely as possible. Rate on a scale of 1 to 10 (where 1 corresponds to the lowest and 10 to the highest) the degree of frequency with which you carry out the following behavior and/or the level of agreement you have with the following statements (as appropriate). |

Permission from the original developer was obtained to

translate as “This part of the questionnaire is designed to gather information on

the ability to obtain knowledge and especially on the use of Evidence-Based Practice

among Health Science professionals.” Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “The following part is designed to understand Health Sciences professionals’ knowledge of the EBP paradigm and their application of EBP in clinical practice.” Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “We will ask you about the use of results from research and possible sources of information available in your clinical practice (e.g., professionals in other disciplines and experts).” |

MINOR (n=2) | 科学的研究による結果に関して

次のパートは健康科学専門職における、EBPのパラダイムに対する知識と、臨床におけるEBPの実践状況について調査するためにデザインされています。研究結果の使い方と、論文データベース以外にあなたの臨床現場でEBPについて情報を得る機会・手段(例 他領域の専門家、エキスパート)についてお伺いします。 以下の各記述に対してできるだけありのままに回答してください。各文の行動をとる頻度、および/または、各文への同意の程度を1∼10段階で教えてください(1=最低、10=最高)。 |

| Item 2–1. I resolve any doubts or questions arising from my practice by searching for up-to-date scientific results. | NO CHANGE (n=1) | 臨床実践の中で生じた疑問や問いに対しては、最新の研究結果を検索して解決している。 | |

| Item 2–2. I ask myself questions in such a way that they can be answered through results from research. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I transform questions into a format that can be searched in databases (e.g., patient・intervention・comparison・outcome).” | NO CHANGE (n=1) | 疑問はデータベースで検索可能なフォーマット(例 介入研究では対象者・介入方法・比較対象・アウトカム)に変換している。 |

| Item 2–3. I use information from scientific research to answer questions arising from my professional practice. | MINOR (n=3) | 私の専門的臨床実践の中で生じる疑問を解決するために、研究で得られる情報を利用している。 | |

| Item 2–4. I use the main sources of scientific information in my discipline. | MINOR (n=1) | 私の専門職分野の科学情報における主たる情報源を利用している。 | |

| Item 2–5. I am able to carry out an effective search of scientific literature in electronic databases. | We emphasized with the plural form due to a request from the developer. | 複数の電子データベースを使って論文を効果的に検索することができる。 | |

| Item 2–6. I am up-to-date with the results from research related to my usual practice. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I am up-to-date with the latest knowledge that directly relates to the usual clinical practice.” | 日常の臨床実践に直接関連する事柄について、最新の知見をアップデートしている。 | |

| Item 2–7. I know the different designs of scientific studies that will enable me to answer my doubts or my questions. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I know what study design is appropriate to sort out my question.” | 私の疑問を解決するにはどのような研究デザインによる知見が適切かわかっている。 | |

| Item 2–8. I normally use standardised aid procedures to assess the quality of scientific literature. | NO CHANGE (n=1) | 論文の質を評価するために、標準化された方法を常に用いている。 | |

| Item 2–9. I usually assess the quality of the methodology used in the research studies I find. | We added “when I read research papers” to enhance readability in Japanese. | MINOR (n=1) | 私が論文を読むときは、普段からその研究方法の質を評価している。 |

| Item 2–10. I recognize the possible bias or confusion factors and limitations of the studies selected. | We added “when I read research papers” to enhance readability in Japanese. | MINOR (n=2) | 私が論文を読むときは、不適切な変数や研究の限界がある可能性を認識している。 |

| Item 2–11. I am capable of interpreting the practical implications of statistical results. | 統計結果から実用的意味を解釈することができる。 | ||

| Item 2–12. I assess the relevance of research results on future interventions. | MINOR (n=1) | 現在の研究結果が将来の介入方法に及ぼす関連性を評価している。 | |

| Item 2–13. I use up-to-date research to make habitual decisions in my professional practice. | MINOR (n=1) | 私は専門家としての日常的な意思決定に最新の研究知見を使用している。 | |

| Item 2–14. I use scientific documentation to guide my interventions towards EBP. | 私は論文を活用してEBPに沿った介入をしている。 | ||

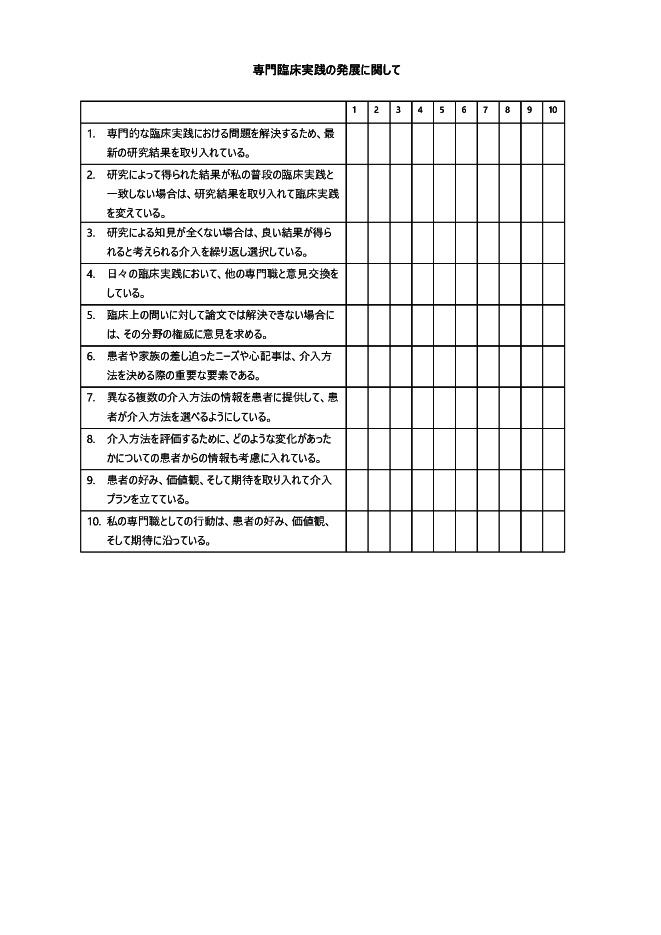

| Domain 3 (Development of professional practice) | 専門臨床実践の発展に関して | ||

| Item 3–1. I incorporate the most up-to-date results from scientific research to solve problems related to my professional practice. | 専門的な臨床実践における問題を解決するため、最新の研究結果を取り入れている。 | ||

| Item 3–2. When results from research do not agree with my usual practice, I change this to incorporate them. | 研究によって得られた結果が私の普段の臨床実践と一致しない場合は、研究結果を取り入れて臨床実践を変えている。 | ||

| Item 3–3. I repeat interventions that have given me good results in situations not supported by results from research. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I select and repeat interventions that are considered to have good results when there are no relevant research findings.” | 研究による知見が全くない場合は、良い結果が得られると考えられる介入を繰り返し選択している。 | |

| Item 3–4. I use exchanges of opinions with other professionals in my daily practice. | 日々の臨床実践において、他の専門職と意見交換をしている。 | ||

| Item 3–5. When approaching situations not resolved by research, I ask for the opinion of renowned professionals. | We added “regarding clinical questions” to enhance readability in Japanese. | NO CHANGE (n=2) | 臨床上の問いに対して論文では解決できない場合には、その分野の権威に意見を求める。 |

| Item 3–6. The immediate needs and concerns of patients and/or their relatives entail an important element of my intervention. | 患者や家族の差し迫ったニーズや心配事は、介入方法を決める際の重要な要素である。 | ||

| Item 3–7. I inform my patients so they can consider the different intervention alternatives we can apply. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I provide my patients with information on possible interventions so that the patient can choose an intervention.” | MINOR (n=1) | 異なる複数の介入方法の情報を患者に提供して、患者が介入方法を選べるようにしている。 |

| Item 3–8. I take into account information provided by my patients regarding their evolution in order to assess my interventions. | MINOR (n=1) | 介入方法を評価するために、どのような変化があったかについての患者からの情報も考慮に入れている。 | |

| Item 3–9. I integrate the preferences, values and expectations of the patient in my interventions. | 患者の好み、価値観、そして期待を取り入れて介入プランを立てている。 | ||

| Item 3–10. My professional actions are agreed on according to the preferences, values and expectations of patients. | 私の専門職としての行動は、患者の好み、価値観、そして期待に沿っている。 | ||

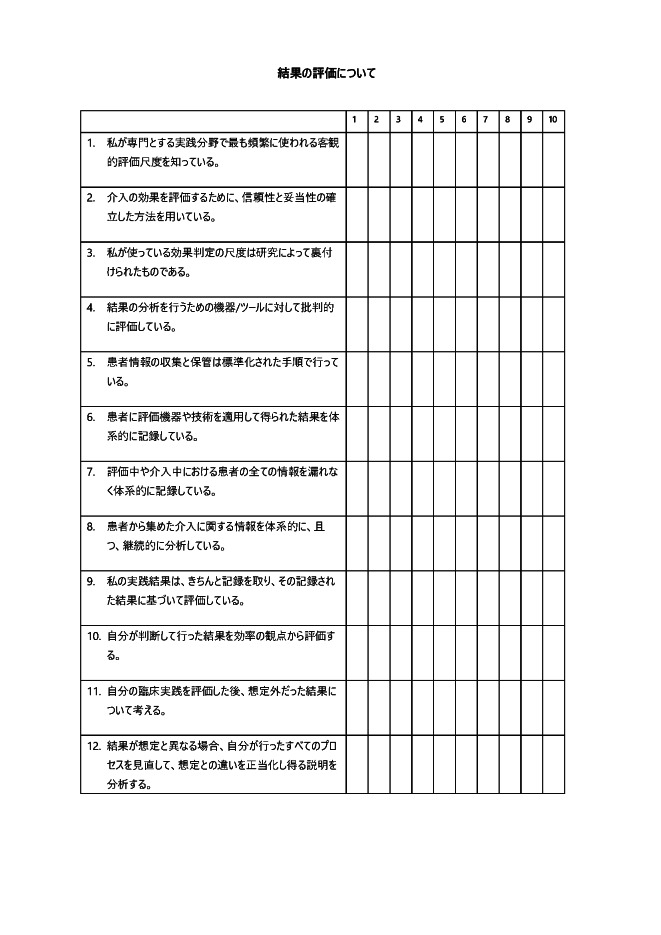

| Domain 4 (Assessment of results) | 結果の評価について | ||

| Item 4–1. I know the objective results assessment measures most frequently used in my specific area of practice. | 私が専門とする実践分野で最も頻繁に使われる客観的評価尺度を知っている。 | ||

| Item 4–2. I use standardised measures, based on scientific evidence, to assess the results of my interventions. | 介入の効果を評価するために、信頼性と妥当性の確立した方法を用いている。 | ||

| Item 4–3. The assessment measures I use have been endorsed by scientific evidence. | 私が使っている効果判定の尺度は研究によって裏付けられたものである。 | ||

| Item 4–4. I critically appraise the instruments/tools available to carry out the results analysis. | MINOR (n=1) | 結果の分析を行うための機器/ツールに対して批判的に評価している。 | |

| Item 4–5. I use a standardised procedure for collecting and storing information on my patients. | 患者情報の収集と保管は標準化された手順で行っている。 | ||

| Item 4–6. I systematically record the results obtained from the application of the assessment instruments or techniques on my patients. | MINOR (n=2) | 患者に評価機器や技術を適用して得られた結果を体系的に記録している。 | |

| Item 4–7. I record information concerning possible changes in the evolution of a case or during the intervention. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I have collected and recorded all information related to the patient systematically.” | The word ‘システマティック’ was difficult to understand and so the expression ‘体系的に’ was used instead (n=3). | 評価中や介入中における患者の全ての情報を漏れなく体系的に記録している。 |

| Item 4–8. I systematically and continuously analyse the information collected on the interventions with my patients. | The word ‘システマティック’ was difficult to understand and so the expression ‘体系的に’ was used instead (n=3). | 患者から集めた介入に関する情報を体系的に、且つ、継続的に分析している。 | |

| Item 4–9. I assess the effects of my practice by recording results. | Permission from the original developer was obtained to translate as “I evaluate the result of my clinical practice using recorded data.” | MINOR (n=2) | 私の実践結果は、きちんと記録を取り、その記録された結果に基づいて評価している。 |

| Item 4–10. I assess the results of applying my decisions in terms of their efficiency. | 自分が判断して行った結果を効率の観点から評価する。 | ||

| Item 4–11. I consider unexpected results after assessing my practice. | 自分の臨床実践を評価した後、想定外だった結果について考える。 | ||

| Item 4–12. When the results do not fit with what is expected, I review the whole process applied in order to analyse possible explanations that may account for them. | MINOR (n=1) | 結果が想定と異なる場合、自分が行ったすべてのプロセスを見直して、想定との違いを正当化し得る説明を分析する。 | |

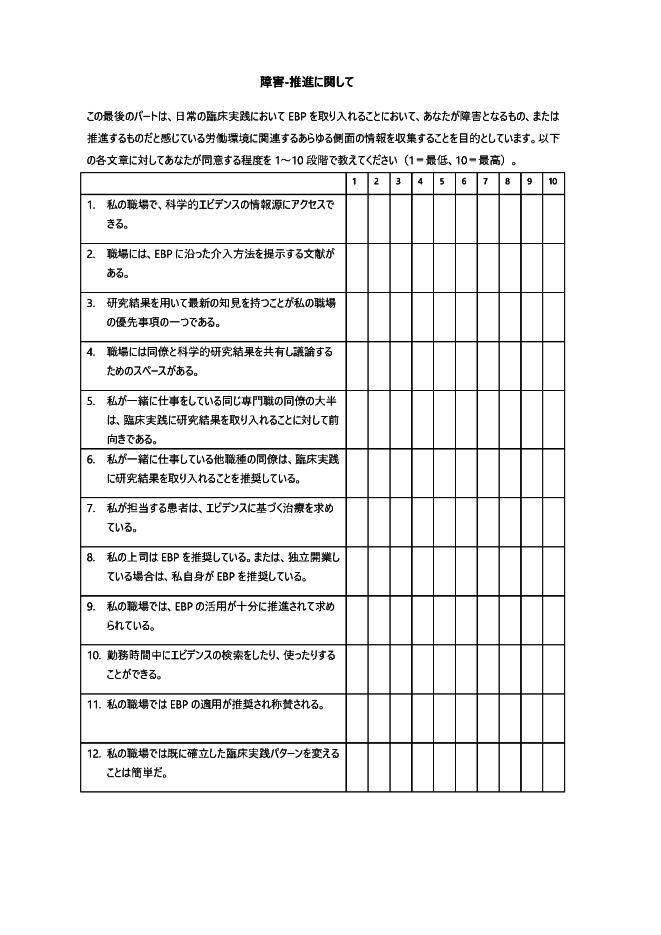

| Domain 5 (Barriers–Facilitators) This last part of the questionnaire aims to collect information on all the aspects related to your work environment that you perceive as BARRIERS or FACILITATORS to adopting Evidence Based Practice in your daily practice. Rate on a scale of 1 to 10 the level of agreement you have with the following statements (where 1 corresponds to the lowest and 10 to the highest). |

The same scoring information was used as the instruction in Domain 1 to enhance readability. | 障害-推進に関して

この最後のパートは、日常の臨床実践においてEBPを取り入れることにおいて、あなたが障害となるもの、または推進するものだと感じている労働環境に関連するあらゆる側面の情報を収集することを目的としています。以下の各文章に対してあなたが同意する程度を1∼10段階で教えてください(1=最低、10=最高)。 |

|

| Item 5–1. I can access resources related to scientific evidence in my workplace. | MINOR (n=1) | 私の職場で、科学的エビデンスの情報源にアクセスできる。 | |

| Item 5–2. In my workplace there are documents that guide interventions towards EBP. | 職場には、EBPに沿った介入方法を提示する文献がある。 | ||

| Item 5–3. Keeping up-to-date with results from research is a priority in my workplace. | 研究結果を用いて最新の知見を持つことが私の職場の優先事項の一つである。 | ||

| Item 5–4. At work there are spaces to share and discuss scientific research results with other colleagues. | NO CHANGE (n=1) | 職場には同僚と科学的研究結果を共有し議論するためのスペースがある。 | |

| Item 5–5. Most of the colleagues from my profession with whom I relate have a favourable attitude towards using results from research in their practice. | MINOR (n=1) | 私が一緒に仕事をしている同じ専門職の同僚の大半は、臨床実践に研究結果を取り入れることに対して前向きである。 | |

| Item 5–6. The colleagues from different professions with whom I relate encourage the use of research in practice. | 私が一緒に仕事している他職種の同僚は、臨床実践に研究結果を取り入れることを推奨している。 | ||

| Item 5–7. My patients demand their treatments be based on scientific evidence. | 私が担当する患者は、エビデンスに基づく治療を求めている。 | ||

| Item 5–8. My supervisors encourage EBP or, in the event of working independently, I myself encourage EBP. | NO CHANGE (n=1) | 私の上司はEBPを推奨している。または、独立開業している場合は、私自身がEBPを推奨している。 | |

| Item 5–9. There are enough recommendations or demands present in my work environment for the use of EBP. | 私の職場では、EBPの活用が十分に推進されて求められている。 | ||

| Item 5–10. Time distribution in my workday facilitates the search for and application of scientific evidence. | MINOR (n =1) | 勤務時間中にエビデンスの検索をしたり、使ったりすることができる。 | |

| Item 5–11. In my workplace the application of EBP is encouraged/rewarded. | In Japan, it seems unusual to obtain a reward, and thus “rewarded” was translated as “be praised”. | MINOR (n=1) | 私の職場ではEBPの適用が推奨され称賛される。 |

| Item 5–12. In my workplace changing established patterns of practice is straightforward. | 私の職場では既に確立した臨床実践パターンを変えることは簡単だ。 |

NO CHANGE, no modification was necessary because comment(s)/suggestion(s) were not relevant [n= the number of comment(s)/suggestion(s)]; MINOR, minor changes of the Japanese expressions or their order were conducted as per suggestion(s).

*This English translation has not yet been validated and was presented for peer review in a previous study.3)

Reliability

Participants were recruited in March 2021 via advertising in Saitama Prefectural University, Saitama, Japan. Included were third and fourth grade undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies with clinical training experience. Exclusion criteria were those participants who had their last clinical training experience more than 6 months previously and those who did not take the second test within 2 days of the target time.

Data were collected twice with a 2-week interval (the second testing survey link was e-mailed to each participant) following the suggestion of the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN).10) At initial testing, after collection of demographic data, participants completed the Japanese HS-EBP questionnaire with reference to experience of their last clinical training period; the time taken to complete the HS-EBP questionnaire was measured. At the second testing, the participants completed the HS-EBP without seeing or trying to recall the responses of the initial testing; participants were asked to take roughly same amount of time as for the initial testing. The Japanese HS-EBP has 60 items, which the participants rated according to their degree of agreement using a ten-point numerical rating scale (1=the lowest agreement; 10=the highest agreement). The Japanese HS-EBP has five domains: (1) Beliefs–Attitudes (12 items with total scores ranging from 12 to 120), (2) Results of scientific research (14 items with scores ranging from 14 to 140), (3) Development of professional practice (10 items with scores ranging from 10 to 100), (4) Assessment of results (12 items with scores ranging from 12 to 120), and (5) Barriers–Facilitators (12 items with scores ranging from 12 to 120). Higher scores indicate greater supporting attitudes or behavior toward the application of EBP in clinical practice.

Participant recruitment continued until a sample size of 50 was achieved for the second testing, a number that was rated as adequate by COSMIN.11) Test–retest reliability was assessed using ICC for each item and domain; ICC values ≥0.7 were considered adequate.12) Further, the minimum detectable change (MDC) for each domain was calculated using the following formulas:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where SD is the standard deviations of combined data samples in the initial and second testing, and the MDC is the smallest integer. Internal consistency was assessed using data from the initial testing in each domain, considering Cronbach α ≥0.7 to be adequate.10) Data distributions were assessed using data from the initial testing for each item and domain, considering floor or ceiling effects when >15% of the responses were the minimum or maximum score.13,14,15) Furthermore, Spearman’s ρ was calculated using data from the initial testing across each domain to examine each domain’s similarity because of uncertainty about the normal distribution of all datasets; inter-domain correlation ρ ≥0.310) was considered adequate, as reported in the original HS-EBP.4) Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 21.0, IBM Corporation, New York, USA) with statistical significance set at 5%.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents a summary of the 30 participants involved in the cross-cultural adaptation of the HS-EBP. During pilot testing with the 30 participants, we obtained 1–6 comments/suggestions per item that had a score <4 for understanding on a 5-point numerical rating scale; 28 of the 60 items and 3 instructions (Domains 1, 2, and 5) had at least one understanding score <4. Appendix 2 summarizes the modifications to the translation made as a result of the pilot testing and shows the resulting changes to the Japanese HS-EBP.

Table 1. Summary of the 30 participants in the cross-cultural adaptation process and the 52 participants in the reliability assessment.

| Variable | n=30 | n=52 |

| Number of men, (%) | 8 (26.7) | 17 (32.7) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 21.9 (2.0) | 21.7 (1.6) |

| Nursing students (number of students), % | 11 (36.7) | 19 (36.5) |

| Physical therapy students (number of students), % | 11 (36.7) | 22 (42.3) |

| Occupational therapy students (number of students), % | 8 (26.6) | 11 (21.2) |

In the reliability assessment, 53 participants completed the initial test questionnaire, and 52 completed the second questionnaire. Consequently, data for 52 participants were analyzed; the demographic data for the 52 participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean (standard deviation) time to complete the Japanese HS-EBP was 11.0 (5.7) min. The ICC values and the ceiling and floor effects are summarized in Table 2. The MDCs were 17 for the Beliefs–Attitudes domain, 43 for the Results of scientific research domain, 25 for the Development of professional practice domain, 27 for the Assessment of results domain, and 35 for the Barriers–Facilitators domain. Internal consistency was adequate in each domain with α values of 0.87, 0.94, 0.86, 0.93, and 0.95 in the Beliefs–Attitudes domain, the Results of scientific research domain, the Development of professional practice domain, the Assessment of results domain, and the Barriers–Facilitators domains, respectively. Spearman’s ρ across each pair of domains is presented in Table 3 and satisfy the hypothesized inter-domain correlations as reported in the original HS-EBP.4)

Table 2. Results of test–retest reliability and ceiling and floor effects with 52 participants.

| Domain/item | Floor effect, % with the minimum score | Ceiling effect, % with the maximum score | Mean (standard deviation) | Test–retest reliability, ICC (95% CI) |

| Domain 1 (Beliefs–Attitudes) total score |

0 | 3.8 | 100.9 (12.1) | 0.74 (0.59 to 0.84) |

| Item 1–1. | 0 | 50.0 | 9.0 (1.3) | 0.24 (−0.03 to 0.48) |

| Item 1–2. | 0 | 38.5 | 8.5 (1.7) | 0.24 (−0.03 to 0.48) |

| Item 1–3. | 0 | 26.9 | 8.3 (1.6) | 0.29 (0.03 to 0.52) |

| Item 1–4. | 0 | 30.8 | 8.4 (1.6) | 0.40 (0.14 to 0.60) |

| Item 1–5. | 0 | 32.7 | 8.4 (1.5) | 0.17 (−0.20 to 0.42) |

| Item 1–6. | 0 | 28.8 | 8.3 (1.6) | 0.37 (0.11 to 0.58) |

| Item 1–7. | 0 | 32.7 | 8.2 (1.7) | 0.23 (−0.04 to 0.47) |

| Item 1–8. | 0 | 36.5 | 8.8 (1.4) | 0.17 (−0.10 to 0.42) |

| Item 1–9. | 0 | 25.0 | 8.1 (1.4) | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.68) |

| Item 1–10. | 0 | 42.3 | 8.7 (1.5) | 0.51 (0.28 to 0.69) |

| Item 1–11. | 0 | 30.8 | 8.4 (1.5) | 0.11 (−0.16 to 0.37) |

| Item 1–12. | 0 | 25.0 | 7.8 (1.8) | 0.06 (−0.21 to 0.33) |

| Domain 2 (Results of scientific research) total score | 0 | 3.8 | 81.2 (24.7) | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.79) |

| Item 2–1. | 0 | 9.6 | 6.5 (2.1) | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.61) |

| Item 2–2. | 5.8 | 7.7 | 5.6 (2.5) | 0.14 (−0.14 to 0.39) |

| Item 2–3. | 0.0 | 19.2 | 7.2 (2.1) | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.75) |

| Item 2–4. | 1.9 | 17.3 | 7.0 (2.3) | 0.57 (0.36 to 0.73) |

| Item 2–5. | 0 | 15.4 | 6.4 (2.4) | 0.55 (0.33 to 0.71) |

| Item 2–6. | 1.9 | 3.8 | 5.3 (2.4) | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.74) |

| Item 2–7. | 9.6 | 7.7 | 4.5 (2.6) | 0.39 (0.13 to 0.60) |

| Item 2–8. | 5.8 | 3.8 | 4.8 (2.3) | 0.51 (0.28 to 0.68) |

| Item 2–9. | 7.7 | 9.6 | 5.1 (2.5) | 0.41 (0.16 to 0.62) |

| Item 2–10. | 3.8 | 17.3 | 6.6 (2.6) | 0.36 (0.10 to 0.58) |

| Item 2–11. | 0 | 3.8 | 5.8 (2.1) | 0.61 (0.40 to 0.75) |

| Item 2–12. | 0 | 5.8 | 6.1 (2.1) | 0.45 (0.21 to 0.64) |

| Item 2–13. | 3.8 | 7.7 | 5.4 (2.4) | 0.33 (0.07 to 0.55) |

| Item 2–14. | 9.6 | 3.8 | 5.0 (2.5) | 0.21 (−0.06 to 0.46) |

| Domain 3 (Development of professional practice) total score |

0 | 1.9 | 68.1 (15.6) | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.82) |

| Item 3–1. | 3.8 | 7.7 | 5.9 (2.4) | 0.53 (0.30 to 0.70) |

| Item 3–2. | 1.9 | 5.8 | 5.8 (2.4) | 0.20 (−0.07 to 0.45) |

| Item 3–3. | 0 | 21.2 | 7.3 (2.1) | 0.21 (−0.07 to 0.45) |

| Item 3–4. | 17.3 | 15.4 | 5.3 (3.2) | 0.33 (0.06 to 0.55) |

| Item 3–5. | 1.9 | 11.5 | 5.9 (2.6) | −0.15 (−0.40 to 0.13) |

| Item 3–6. | 0 | 48.1 | 8.8 (1.5) | 0.01 (−0.26 to 0.28) |

| Item 3–7. | 5.8 | 9.6 | 6.1 (2.7) | −0.10 (−0.36 to 0.17) |

| Item 3–8. | 3.8 | 25.0 | 7.6 (2.3) | 0.40 (0.14 to 0.60) |

| Item 3–9. | 0 | 34.6 | 8.3 (1.9) | 0.52 (0.29 to 0.69) |

| Item 3–10. | 1.9 | 15.4 | 7.2 (2.1) | 0.44 (0.19 to 0.63) |

| Domain 4 (Assessment of results) total score | 0 | 0 | 83.6 (19.6) | 0.75 (0.61 to 0.85) |

| Item 4–1. | 5.8 | 11.5 | 6.4 (2.5) | 0.51 (0.28 to 0.68) |

| Item 4–2. | 0 | 15.4 | 6.7 (2.4) | 0.65 (0.46 to 0.78) |

| Item 4–3. | 5.8 | 15.4 | 6.4 (2.5) | 0.44 (0.20 to 0.64) |

| Item 4–4. | 5.8 | 7.7 | 5.8 (2.5) | 0.07 (−0.20 to 0.33) |

| Item 4–5. | 0 | 28.8 | 7.9 (2.0) | 0.57 (0.35 to 0.72) |

| Item 4–6. | 1.9 | 23.1 | 7.4 (2.2) | 0.69 (0.52 to 0.81) |

| Item 4–7. | 1.9 | 13.5 | 6.9 (2.3) | 0.68 (0.50 to 0.80) |

| Item 4–8. | 1.9 | 15.4 | 7.1 (2.2) | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.68) |

| Item 4–9. | 1.9 | 25.0 | 7.7 (2.1) | 0.34 (0.07 to 0.56) |

| Item 4–10. | 1.9 | 7.7 | 6.1 (2.2) | –0.00 (−0.27 to 0.27) |

| Item 4–11. | 0 | 15.4 | 8.0 (1.5) | 0.54 (0.32 to 0.71) |

| Item 4–12. | 0 | 9.6 | 7.2 (1.8) | 0.15 (−0.12 to 0.41) |

| Domain 5 (Barriers–Facilitators) total score | 0 | 0 | 80.1 (25.1) | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.84) |

| Item 5–1. | 1.9 | 21.2 | 7.1 (2.5) | 0.54 (0.32 to 0.71) |

| Item 5–2. | 1.9 | 21.2 | 6.9 (2.6) | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.68) |

| Item 5–3. | 3.8 | 9.6 | 6.7 (2.4) | 0.50 (0.27 to 0.68) |

| Item 5–4. | 5.8 | 9.6 | 6.4 (2.7) | 0.56 (0.34 to 0.72) |

| Item 5–5. | 3.8 | 21.2 | 7.2 (2.6) | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.73) |

| Item 5–6. | 3.8 | 23.1 | 7.1 (2.7) | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.67) |

| Item 5–7. | 3.8 | 15.4 | 6.8 (2.4) | 0.49 (0.25 to 0.67) |

| Item 5–8. | 5.8 | 23.1 | 7.1 (2.7) | 0.56 (0.35 to 0.72) |

| Item 5–9. | 3.8 | 19.2 | 6.9 (2.6) | 0.60 (0.39 to 0.75) |

| Item 5–10. | 7.7 | 17.3 | 5.9 (3.0) | 0.46 (0.22 to 0.65) |

| Item 5–11. | 3.8 | 17.3 | 6.7 (2.5) | 0.49 (0.25 to 0.67) |

| Item 5–12. | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.3 (2.6) | –0.31 (−0.54 to –0.04) |

Table 3. Inter-domain correlations in the Japanese Health Sciences Evidence-Based Practice questionnaire with 52 participants.

| Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Domain 5 | |

| Domain 1 (Beliefs–Attitudes) | 0.40 (0.003) | 0.51 (<0.001) | 0.46 (0.001) | 0.33 (0.017) |

| Domain 2 (Results of scientific research) | 0.63 (<0.001) | 0.34 (<0.001) | 0.46 (0.001) | |

| Domain 3 (Development of professional practice) | 0.72 (<0.001) | 0.64 (<0.001) | ||

| Domain 4 (Assessment of results) | 0.63 (<0.001) |

Values are presented as Spearman's ρ (P-value).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, a Japanese version of the HS-EBP questionnaire was developed, based on Beaton’s guidelines.8) that was applicable to both professionals and undergraduate students. The HS-EBP is superior to other EBP participant-reported outcome measures (PROMs) because of its more rigorous development process, including content validity considerations.3) Therefore, the Japanese HS-EBP is expected to be a foundation for investigating solutions aimed at enhancing EBP in clinical practice in Japan. Further, items of the Japanese HS-EBP can act as reference points for training to enhance EBP adherence and compliance among undergraduate students and rehabilitation professionals in Japan.

Reliability assessments confirmed adequate internal consistency and inter-domain correlations, consistent with the findings of a previous study using the original Spanish HS-EBP and including 869 professionals in medicine (55%), nursing (14%), physical therapy (20%), and psychology (9%) in Spain. Further, adequate test–retest reliability was observed in the total scores in four domains; the exception was the 14-item Domain 2 (Results of scientific research) (ICC=0.66). However, the ICC values in the current study are comparable to, or better than, those of the previous study,4) whose ICC values (95% confidence intervals) were 0.53 (0.5–0.55), 0.63 (0.61–0.65), 0.35 (0.32–0.37), 0.57 (0.54–0.60), and 0.47 (0.44–0.49) for Domains 1–5. These findings support the reliability of the Japanese HS-EBP among undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies.

Cronbach’s α for the internal consistency was greater than 0.90 in Domains 2, 4, and 5. However, scales with α >0.9 are known to include redundant items.16) Further, the average time to complete the Japanese HS-EBP was 11.0 min, with a median of 10 min being feasible for a web survey.17) Nonetheless, there were items with inadequate test–retest reliability. Potential reasons for such low ICCs may include problems in the item’s comprehensibility and the psychometric property of the content validity,18) which indicate that the participants might have had difficulty in correctly understanding items with low ICCs. Another potential reason could be a problem with the ten-point scale: Simms et al.19) suggested that an optimal scale for a PROM is a 6-point Likert scale rather than the 0–10 scale for PROMs. The Japanese HS-EBP is expected to be used with other PROMs to explore strategies to enhance EBP in clinical practice. Therefore, it would be useful to make a shorter version of the Japanese HS-EBP in the future by excluding items with the smallest ICC values along with assessments of participant’s comprehension and confirmation of the structural validity of each domain.

Generally speaking, more ceiling effects were observed than floor effects in each item across each domain. The MDC in proportion to the total score in each domain was 14.2% (17/120), 30.7% (43/140), 25.0% (25/100), 22.5% (27/120), and 29.2% (35/120) for the Beliefs–Attitudes, Results of scientific research, Development of professional practice, Assessment of results, and Barriers–Facilitators domains, respectively. These findings indicate that the Japanese version of the HS-EBP may have responsiveness concerns among undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies. However, such a biased response may also be a feature of a small cohort of undergraduate students. In the future, with a far larger cohort that includes professionals, Rasch analysis will be required for targeting evaluation to investigate each item’s appropriateness and the appropriateness of the 0–10 scale.

The current study’s possible limitations include the sampling process, since participation was voluntary. Therefore, those with low and high confidence levels toward EBP might have chosen not to participate in the study (self-selection bias); however, some of those with particularly high confidence toward EBP might have participated (self-serving bias). These factors might help to explain why more ceiling effects were observed than floor effects in each item across each domain. However, the effect of these potential limitations on the current findings of adequate reliability in most domains is uncertain. Further investigations using more robust sampling methods are required to comprehensively establish the reliability of the Japanese HS-EBP.

In conclusion, this study developed the Japanese version of the HS-EBP. We found preliminary evidence of adequate internal consistency and test–retest reliability in most domains for undergraduate students of nursing and physical and occupational therapies. The need for further investigations to develop a shorter version with higher test–retest reliability was also considered.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1. The Japanese Health Sciences Evidence-based Questionnaire (Japanese HS-EBP)

An English version of the Health Sciences Evidence Based Questionnaire is available for reference: (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177172.s002).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernández-Domínguez JC,Sesé-Abad A,Morales-Asencio JM,Oliva-Pascual-Vaca A,Salinas-Bueno I,de Pedro-Gómez JE: Validity and reliability of instruments aimed at measuring evidence-based practice in physical therapy: a systematic review of the literature. J Eval Clin Pract 2014;20:767–778. 10.1111/jep.12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sackett D,Strauss S,Richardson W,Rosenberg W,Hayes RB: Evidence-Based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2000, 261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernández-Domínguez JC,Sesé-Abad A,Morales-Asencio JM,Sastre-Fullana P,Pol-Castañeda S,de Pedro-Gómez JE: Content validity of a health science evidence-based practice questionnaire (HS-EBP) with a web-based modified Delphi approach. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:764–773. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernández-Domínguez JC,de Pedro-Gómez JE,Morales-Asencio JM,Bennasar-Veny M,Sastre-Fullana P,Sesé-Abad A: Health Sciences-Evidence Based Practice questionnaire (HS-EBP) for measuring transprofessional evidence-based practice: creation, development and psychometric validation. PLoS One 2017;12:e0177172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang BY,Mei-Ling Y,Hung-Da D: Translation and Validation of the Health Sciences Evidence-Based Practice (HS-EBP) Questionnaire for Nurses in Taiwan. Nursing Education Research Conference 2020: Transforming Nursing Education Through Evidence Generation and Translation. 2020. https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/bitstream/handle/10755/20063/Chang_AbstractInfoF14.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y: Accessed 6 May 2021.

- 6.Fujimoto S,Kon N,Takasugi J,Nakayama T: Attitudes, knowledge and behavior of Japanese physical therapists with regard to evidence-based practice and clinical practice guidelines: a cross-sectional mail survey. J Phys Ther Sci 2017;29:198–208. 10.1589/jpts.29.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomotaki A,Fukahori H,Sakai I: Exploring sociodemographic factors related to practice, attitude, knowledge, and skills concerning evidence‐based practice in clinical nursing. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2020;17:e12260. 10.1111/jjns.12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaton DE,Bombardier C,Guillemin F,Ferraz MB: Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000;25:3186–3191. 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos MR,Nogueira LC,Armando Meziat-Filho N,Oostendorp R,Reis FJ: Transcultural adaptation into Portuguese of an instrument for pain evaluation based on the biopsychosocial model. Fisioter Mov 2017;30(suppl 1):183–195. 10.1590/1980-5918.030.s01.ao18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokkink LB,Prinsen C,Patrick DL,Alonso J,Bouter LM,de Vet HC,Terwee CB: COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). 2018. https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-syst-review-for-PROMs-manual_version-1_feb-2018.pdf:Accessed 6 May 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Mokkink LB,Prinsen CA,Patrick DL,Alonso J,Bouter LM,de Vet HC,Terwee CB: COSMIN study design checklist for patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. 2019. https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf: Accessed 6 May 2021.

- 12.Mokkink LB,Boers M,van der Vleuten CP,Patrick DL,Alonso J,Bouter LM,de Vet HC,Terwee CB: COSMIN Risk of Bias tool to assess the quality of studies on reliability and measurement error of outcome measurement instrument: user manual. 2021. https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/user-manual-COSMIN-Risk-of-Bias-tool_v4_JAN_final.pdf: Accessed 6 May 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Takasaki H,Treleaven J: Construct validity and test–retest reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale in people with chronic neck pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1328–1334. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takasaki H,Chien CW,Johnston V,Treleaven J,Jull G: Validity and reliability of the perceived deficit questionnaire to assess cognitive symptoms in people with chronic whiplash-associated disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:1774–1781. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobart JC,Thompson AJ: The five item Barthel index. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:225–230. 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Streiner DL: Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess 2003;80:99–103. 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prinsen CA,Vohra S,Rose MR,Boers M,Tugwell P,Clarke M,Williamson PR,Terwee CB: How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials 2016;17:449. 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simms LJ,Zelazny K,Williams TF,Bernstein L: Does the number of response options matter? Psychometric perspectives using personality questionnaire data. Psychol Assess 2019;31:557–566. 10.1037/pas0000648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Revilla M,Ochoa C: Ideal and maximum length for a web survey. Int J Mark Res 2017;59:557–565. [Google Scholar]