Abstract

Background:

Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (SAM) may be linked to both short- and longer-term problems for young adults. Across two years of longitudinal data, we examined between- and monthly within-person associations of alcohol and marijuana use patterns, including SAM, with negative alcohol-related consequences, depressive symptoms, and general health.

Methods:

773 young adults (aged 18-23 at screening; 56% women) who used alcohol in the year prior to study enrollment were surveyed monthly for 24 months. Multilevel models assessed associations of alcohol and marijuana use patterns with outcomes.

Results.

Individuals who reported a higher proportion of SAM months had more negative alcohol-related consequences (Rate Ratio [RR] = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.17,1.89). At the within-person level, participants experienced more alcohol-related consequences on months when SAM was reported compared to months of alcohol-only (RR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.10,1.25) and months of concurrent alcohol and marijuana use without simultaneous use (CAM; RR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.11,1.29). Compared to alcohol-only, SAM was associated with more depressive symptoms and poorer general health at the between-person level and with more depressive symptoms at the monthly within-person level; however, SAM did not differ substantially from using neither alcohol nor marijuana or CAM for these outcomes at either the between- or within-person level.

Conclusions.

SAM use may indicate risk for negative alcohol-related consequences, both within months of SAM use and across more extended time periods. Individuals who engage in SAM may experience worse mental and physical health than individuals who use alcohol exclusively.

Keywords: simultaneous alcohol and marijuana, consequences, depressive symptoms, physical health, young adult

1. Introduction

Recent nationwide data from the Monitoring the Future study suggest that within the prior year a quarter of young adult drinkers engaged in using alcohol and marijuana at the same time with overlapping effects (Terry-McElrath & Patrick, 2018). Both alcohol and marijuana use have negative consequences (Caulkins, 2016; Hingson, Zha, & Smyth, 2017), and simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (SAM) may exacerbate both substance-use-specific and more general health consequences. It may also be that individuals who engage in SAM are prone to risky behaviors (Linden-Carmichael, Stamates, & Lau-Barraco, 2019) or use substances to self-medicate (Bolton, Robinson, & Sareen, 2009; Turner, Mota, Bolton, & Sareen, 2018).

1.1. Potential consequences of SAM

Young adults commonly engage in SAM to increase feelings of intoxication (Patrick, Fairlie, & Lee, 2018; Patrick & Lee, 2018). Relative to alcohol-only or concurrent alcohol and marijuana use within a given time period without simultaneous use (CAM), cross-sectional studies have found past-year and past-month SAM to be positively associated with increased intoxication effects and negative consequences (Cummings et al., 2019; Duckworth & Lee, 2019; Lee, Cadigan, & Patrick, 2017; Linden-Carmichael et al., 2019; Midanik, Tam, & Weisner, 2007; Subbaraman & Kerr, 2015; Terry-McElrath, O’Malley, & Johnston, 2014). Studies of particular substance use occasions (Egan et al., 2019) and daily data (Lee et al., 2020; Linden-Carmichael, Van Doren, Masters, & Lanza, 2020; Lipperman-Kreda, Gruenewald, Grube, & Bersamin, 2017) have also found SAM, compared to alcohol-only, increased negative alcohol-related consequences during or following SAM occasions.

SAM may have broader effects, worsening the impact of substance use on mental health, such as depressive symptoms, and physical health. Heavy drinking and marijuana use have been linked to depression and multiple physical health problems among adolescents and adults (Grønbæk, 2009; Oesterle et al., 2004; Pedrelli, Shapero, Archibald, & Dale, 2016; Volkow et al., 2014). SAM may worsen these problems by increasing risk taking, poor decision making, and interpersonal conflicts, all of which could lead to psychological distress or accidents that affect general health. Associations between SAM and broader mental and physical health may also be accounted for by common causes, such as high levels of sensation seeking (Linden-Carmichael et al., 2019) or problems related to mental or physical health that lead to substance use, including SAM, as self-medication (Turner et al., 2018).

1.2. Between- and within-person associations

Across young adulthood, individuals display both continuity and within-person shifting in substance use patterns (Marin, Thompson, & Leadbeater, 2018). The current study extends prior research by examining how between-person variability in SAM across 24 months (i.e., the proportion of months that were SAM months) and within-person variability in SAM use from month-to-month relate to potential consequences. Associations at the between-person level allow for identifying individuals at risk for poor behavioral or health outcomes based on the number of months in which they engage in SAM. Within-person associations of month-to-month variability in SAM being concurrently related to month-to-month variability in outcomes may help identify particular periods of heightened risk and guide the timing of selective or indicated intervention.

1.4. The Present Study

We used data collected monthly for 24 consecutive months in a young adult sample to examine associations between patterns of alcohol and marijuana use and negative alcohol-related consequences, depressive symptoms, and poor general health. The analyses addressed whether (1) engagement in SAM in more months over two years was associated with these outcomes and (2) month-to-month variability in SAM was associated with month-to-month variability in outcomes. In order to assess specific effects of SAM, we contrasted SAM with multiple other substance use patterns in addition to adjusting for amount and frequency of alcohol and marijuana use when applicable for a given contrast. For negative alcohol-related consequences, we examined contrasts between SAM and both alcohol-only (controlling for amount and frequency of alcohol use) and CAM (controlling for amount/frequency of both alcohol and marijuana use). For depressive symptoms and poor general health, we also examined contrasts between SAM and using neither alcohol nor marijuana. Based on findings from prior research, we expected SAM would be uniquely and positively associated with more alcohol-related consequences. We were also guided by the hypothesis that SAM would be uniquely associated with worse mental and general health.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

The sample included participants in a study on substance use and young adult social role transitions (Lee et al., 2017; Patrick, Rhew, et al., 2018). Eligibility criteria included being 18 to 23 years of age at screening, having drunk alcohol in the prior year, and living within 60 miles of the study office in Seattle, WA. Between January 2015 and January 2016, participants were recruited through media advertisements, outreach at community colleges, and friend referrals. Participants received $40 for completing a baseline assessment. Subsequently, participants did surveys online in 24 consecutive months, compensated with gift cards (up to $680 total). The University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Of the 779 participants enrolled in the project, 6 were excluded from the current study because they did not provide information on substance use in at least one monthly survey. A majority of the sample was female (56%) and the racial composition was 59% White, 18% Asian, 5% Black, and 18% other (including Native American, Pacific Islander, and multiracial), with 9% identifying as Hispanic/Latino. At the beginning of the study, 75% were in school and 61% were employed at least part-time. The 773 participants in the analytic sample completed an average of 19.98 (SD = 6.06) monthly surveys, with 76% completing at least 18 surveys.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Substance use pattern, including SAM

Each month, respondents reported on frequency of alcohol and marijuana use in the prior calendar month. Based on this information, patterns of (1) neither alcohol nor marijuana, (2) alcohol-only, and (3) marijuana-only were defined. Among those reporting both alcohol and marijuana use in the reference month, we distinguished between (4) CAM and (5) SAM based on answers to the item: “How many of the times when you used marijuana or hashish during the last month did you use it at the same time as alcohol - that is, so that their effects overlapped?” Response options for this item ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (every time). Respondents who answered 0 were coded as engaging in CAM; respondents who responded 1 or higher were coded as engaging in SAM.

2.2.2. Monthly alcohol and marijuana use

We computed a composite measure of alcohol use based on three components. Frequency of (1) any alcohol use and (2) heavy episodic drinking (threshold of 4+/5+ in a two-hour period depending on sex at birth; National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2003) were based on items with response options ranging from 0 (never) to 7 (every day). We also included (3) number of drinks consumed in a typical week (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). A composite measure was computed as the mean of z-scores of the three component scores. Frequency of marijuana use was based on the number of occasions of use, with response options ranging from 0 (0 occasions) to 6 (40 or more occasions).

2.2.3. Alcohol use consequences

Participants who consumed alcohol indicated if they had experienced any of 24 negative consequences in the past month using the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006). Affirmative responses to the consequences were summed (α= .87-.91 across months). In secondary analyses we examined the six individual consequences most commonly endorsed in our study. This included physical symptoms of (1) having a hangover, (2) getting sick to the stomach or throwing up, and (3) being tired or having less energy due to drinking. It also included social and decision-making consequences of (4) saying or doing something embarrassing, (5) taking foolish risks, and (6) doing impulsive things that were later regretted.

2.2.4. Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the PHQ-2 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003), which asked how often, in the past month, respondents felt bothered by (1) “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” and (2) “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day), and depressive symptom score was the sum of the item scores. This measure has shown evidence of criterion validity with reference to depression diagnosis based on structured clinical interviews (Lowe et al., 2005).

2.2.5. Poor general health

A measure of poor general health was based on one item: “In general, how would you say your health was in (reference month)?” Response options ranged from 0 (poor) to 4 (excellent). This widely used measure encompasses physical and mental health, although it has found to be more strongly associated with physical health (Hays et al., 2009). For a measure of poor general health, we reversed coded the items scores so that a higher score represented worse general health.

2.2.6. Covariates

Biological sex (0=male, 1=female), age (in years) at baseline, and race/ethnicity were used as a person-level covariates. Race/ethnicity was represented with four categories: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Other (including Black, Native American, and multiracial), and Hispanic. In regression models, race/ethnicity was dummy coded with non-Hispanic White treated as the reference category. At the within-person monthly level, time in the study in years (study month divided by 12) was included as a time-varying covariate.

2.3. Data Analysis

We used multilevel models with random intercepts to estimate between- and within-person associations between SAM and the three outcomes. These models capture between-person associations with effects of person-level variables for proportion of months that fell within a given substance use pattern (relative to an individual’s total number of months included in the given analysis) and within-person associations with effects of time-varying dummy variables for pattern of use. We ran a series of models for each outcome to contrast SAM with other substance use patterns, controlling for quantity/frequency of alcohol and marijuana use when applicable.

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed in alcohol-use months, limiting the substance use patterns to alcohol-only, CAM, and SAM. A first model focused on whether SAM was associated with more alcohol-related consequences compared to alcohol-only. Person-level covariates included: sex, race/ethnicity, age at baseline (centered at age 21), proportion of total months in which alcohol was used, average quantity/frequency of alcohol use across alcohol-use months, and proportions of alcohol-use months that were CAM and SAM (with proportion alcohol-only as the reference). Time-varying covariates were: month of the study, quantity/frequency of alcohol use, and dummy codes for CAM and SAM (again with alcohol-only as the reference). A second model excluded alcohol-only months and contrasted SAM with CAM in order to assess whether SAM was associated with consequences over and above using both alcohol and marijuana in the same month and frequency of marijuana use. This model treated CAM as the reference category for pattern of use, controlled for frequency of marijuana use at both the person-average and monthly level, and adjusted for a person-level covariate for the number of months that involved both alcohol and marijuana use.

For depressive symptoms and poor general health, the first models used data from all months and included all five substance use patterns. These models included person-level covariates for proportions of all months that fell into each of the four patterns that involved alcohol or marijuana use (with proportion neither alcohol nor marijuana as the reference) as well as within-person dummy codes for those patterns. Subsequent models were based on (1) months of alcohol use and included quantity/frequency of alcohol use as a between- and within-person covariate and (2) months in which both marijuana and alcohol were used and included both quantity/frequency of alcohol and frequency of marijuana use as between- and within-person covariates. These models also included person-level covariates for the proportion of total months used in the analyses.

Negative alcohol-related consequences was treated as a count variable with a negative binomial distribution model, and the associations between covariates and the outcome are expressed as rate ratios (RRs). RRs can be interpreted in terms of the proportional change in number of consequences associated with a one unit increase in the given covariate (Atkins, Baldwin, Zheng, Gallop, & Neighbors, 2013). Follow-up analyses examining individual consequences used a logistic model, with associations expressed as odds ratios. Depressive symptoms and poor general health were analyzed with linear models that treat these outcomes as having a continuous and normal distribution.

Models were run with Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017) and maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Unit-specific estimates (i.e., conditional on random effects) are provided for negative binomial and logistic models. Despite missing data due to survey non-completion at some time points, the modeling approach should yield unbiased estimates under the assumption that data were missing at random after accounting for model covariates (Graham, 2012). A statistical significance criterion of p<.05 was used to organize the presentation of the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive information on substance use

As shown in Table 1, alcohol use was reported in 78% of person months and marijuana use in 33%. A total of 756 participants (98% of the sample) reported at least one month of alcohol use, and 563 (73%) reported at least one month of marijuana use. The least common monthly substance use pattern was marijuana-only (4%); the most common was alcohol-only (48%). At the person level, 60% of the sample reported at least one SAM month, 55% reported a CAM month, 83% reported an alcohol-only month, and 21% reported a marijuana-only month. At least one negative alcohol-related consequence was reported in 60% of alcohol-use months.

Table 1.

Descriptive information for study variables.

| N | % | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-level variables (n=773) | ||||

| Female | 434 | 56 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 425 | 55 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 137 | 18 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 142 | 18 | ||

| Hispanic | 69 | 9 | ||

| Age at enrollment | 21.11 | 1.70 | ||

| Proportion of months of alcohol use | .78 | .29 | ||

| Proportion of months of marijuana use | .36 | .37 | ||

| Person average quantity/frequency of alcohol use across alcohol-use months (person mean of monthly measures)a | 0.02 | 0.82 | ||

| Person average marijuana use occasions across marijuana-use months (person mean of monthly measures) | 1.18 | 1.76 | ||

| Proportions of months for patterns of use | ||||

| Alcohol-only | 0.46 | 0.34 | ||

| Marijuana-only | 0.04 | 0.12 | ||

| CAM | 0.10 | 0.16 | ||

| SAM | 0.21 | 0.30 | ||

| Time-varying (months) (n=15,448) | ||||

| Negative alcohol consequence (n=11,882) | 2.63 | 3.76 | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.41 | 1.49 | ||

| Poor health | 1.56 | 1.02 | ||

| Quantity/frequency of alcohol usea | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Marijuana use occasions | 1.07 | 1.89 | ||

| Substance use pattern in a given month | ||||

| Neither alcohol nor marijuana | 2,873 | 19 | ||

| Alcohol-only | 7,409 | 48 | ||

| Marijuana-only | 569 | 4 | ||

| CAM | 1,597 | 10 | ||

| SAM | 3,000 | 19 |

Note. SAM=simultaneous alcohol and marijuana; CAM=concurrent alcohol and marijuana but not simultaneous use.

Sum of z-scores for frequency of any alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking and number of drinks consumed in a typical week.

3.2. Alcohol-related consequences

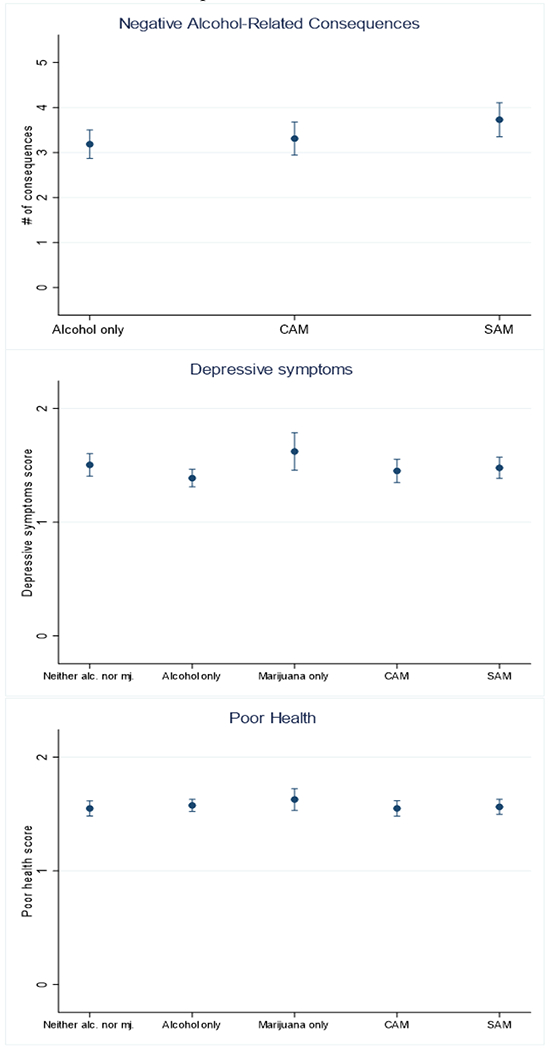

The first model examining alcohol-related consequences indicated that SAM, compared to alcohol-only, was positively associated with consequences at both the between- and within-person level (Table 2). Based on the model estimates and holding other variables at their sample means, an individual reporting SAM in 10% of alcohol-use months would be expected to have an average of 3.04 (95% CI = 2.68, 3.40) consequences per month compared to an average of 3.86 (95% CI = 3.41, 4.32) for an individual reporting SAM in 70% of alcohol-use months. SAM in a particular month was associated with 17% (RR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.10,1.25) more consequences compared to alcohol-only (Table 2 and the first panel of Figure 1). The second model, based on months in which both alcohol and marijuana were used, indicated that, in addition to proportion of marijuana use months that were SAM months being positively associated with consequences (RR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.05,1.93), SAM months had 20% (RR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.11,1.29) more consequences compared to CAM months.

Table 2:

Multilevel negative binomial models predicting negative alcohol-related consequences.

| Fixed effect | Alcohol-use months (n = 11,909 person months among 754 individuals) | Months in which both alcohol and marijuana used (n = 4,469 person months among 530 individuals) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |

| Between person | ||||

| Intercept | 0.53 | (0.37,0.75) | 0.75 | (0.59,0.96) |

| Female | 1.54 | (1.34,1.78) | 1.28 | (1.09,1.51) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.17 | (0.95,1.42) | 1.39 | (1.09,1.77) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.21 | (1.01,1.45) | 1.15 | (0.94,1.41) |

| Hispanic | 1.03 | (0.81,1.31) | 1.07 | (0.82,1.40) |

| Age in years | 1.00 | (0.95,1.04) | 1.01 | (0.97,1.06) |

| Proportion of all months | ||||

| Alcohol use | 1.23 | (0.82,1.84) | ||

| Alcohol and marijuana use | 1.04 | (0.74,1.44) | ||

| Person average substance use quantity/frequency | ||||

| Alcohol use quantity/frequency | 1.60 | (1.39,1.84) | 1.42 | (1.25,1.62) |

| Marijuana use occasions | 1.01 | (0.94,1.09) | ||

| Proportion of alcohol-use months | ||||

| Alcohol-only | ref. | ref. | ||

| CAM | 1.03 | (0.66,1.62) | ||

| SAM | 1.49 | (1.17,1.89) | ||

| Proportion of alcohol and marijuana months | ||||

| CAM | ref. | ref. | ||

| SAM | 1.42 | (1.05,1.93) | ||

| Within-person (time-varying) | ||||

| Month of study (in years) | 0.89 | (0.85,0.93) | 0.96 | (0.91,1.02) |

| Quantity/frequency of alcohol use | 2.07 | (1.97,2.19) | 1.83 | (1.72,1.95) |

| Marijuana use occasions | 0.98 | (0.95,1.01) | ||

| Substance use category | ||||

| Alcohol-only | ref. | ref. | ||

| CAM | 1.04 | (0.97,1.12) | ref. | ref. |

| SAM | 1.17 | (1.10,1.25) | 1.20 | (1.11,1.29) |

| Random effects | ||||

|

| ||||

| Intercept variance | 0.73 | 0.60 | ||

Note. SAM=simultaneous alcohol and marijuana; CAM=concurrent alcohol and marijuana but not simultaneous use. Bold typeface indicates fixed effects p<.05

Figure 1.

Model predicted outcomes by substance use pattern in a given month with other model covariates at their sample mean values.

In secondary analyses, most estimates for SAM effects on individual consequences were positive (see table in the online supplement). In models based on alcohol-use months, odds ratios for between-person effects of SAM ranged from 0.91 to 2.17 (p<.05 for sick to stomach [OR = 1.75] and fatigue [OR = 2.17]), and odds ratios for within-person effects of SAM in a particular month ranged from 1.17 to 2.19 (p<.05 for hangover [OR = 1.48], fatigue [OR = 1.35], took foolish risk [OR = 2.19], and did something regretted [OR = 1.50]). In models contrasting SAM with CAM, odds ratios for between-person effects of SAM ranged from 0.76 to 2.51 (p<.05 for fatigue [OR = 2.51]) and odds ratios for within-person effects ranged from 1.05 to 1.76 (p<.05 for hangover [OR = 1.53], did something embarrassing [OR = 1.41], and took foolish risk [OR = 1.76]).

3.4. Depressive symptoms

Alcohol-only was associated with the lowest levels of depressive symptoms out of the five patterns of substance use. In contrast, abstaining from both alcohol and marijuana and marijuana-only were characterized by relatively high levels of depressive symptoms (Table 3; second panel of Figure 1). In the model using all months, both the proportion of months that were alcohol-only (B = −0.56, 95% CI = −0.91,−0.22) and alcohol-only in a particular month (B = −0.12, 95% CI = −0.19,−0.04) were associated with fewer depressive symptoms compared to using neither alcohol nor marijuana. The second model, based on alcohol-use months, indicated that the proportion of months that were SAM months was positively associated with depressive symptoms (B = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.10,0.69) and, at the within-person level, SAM in a particular month was associated with greater depressive symptoms compared to alcohol-only (B = 0.09, 95% CI = 0.01,0.17). The model contrasting SAM with CAM indicated that SAM was not strongly associated with depressive symptoms compared to CAM (between-person association: B = −0.29, 95% CI = −0.65,0.08; within-person association: B = 0.05, 95% CI = −0.04,0.15).

Table 3.

Multilevel linear models predicting depressive symptoms

| Fixed effects | All months (n = 15,336 person months among 773 individuals) | Alcohol-use months (n = 11,921 person months among 755 individuals) | Months in which both alcohol and marijuana used (n = 4,553 person months among 545 individuals) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | |

| Between person | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.74 | (1.44,2.03) | 1.82 | (1.47,2.18) | 1.12 | (0.82,1.42) |

| Female | 0.29 | (0.14,0.44) | 0.28 | (0.13,0.44) | 0.20 | (−0.01,0.41) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White (reference) | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | −0.02 | (−0.22,0.17) | −0.02 | (−0.23,0.18) | −0.01 | (−0.29,0.26) |

| Non-Hispanic White Other | −0.02 | (−0.22,0.19) | −0.03 | (−0.24,0.18) | 0.04 | (−0.23,0.32) |

| Hispanic | −0.02 | (−0.28,0.25) | 0.00 | (−0.28,0.27) | 0.04 | (−0.33,0.40) |

| Age in years | 0.01 | (−0.03,0.06) | 0.02 | (−0.02,0.07) | 0.01 | (−0.04,0.07) |

| Proportion of all months | ||||||

| Alcohol use | −0.85 | (−1.26,−0.44) | ||||

| Both alcohol and marijuana use | −0.13 | (−0.54,0.29) | ||||

| Person average substance use | ||||||

| Alcohol use quantity/frequency | 0.11 | (−0.04,0.26) | −0.03 | (−0.20,0.14) | ||

| Marijuana use occasions | 0.13 | (0.03,0.23) | ||||

| Proportion of all months | ||||||

| Neither alcohol nor marijuana | ref. | ref. | ||||

| Alcohol-only | −0.56 | (−0.91,−0.22) | ||||

| Marijuana-only | 0.26 | (−0.76,1.28) | ||||

| CAM | −0.48 | (−0.99,0.03) | ||||

| SAM | −0.03 | (−0.41,0.36) | ||||

| Proportion of alcohol-use months | ||||||

| Alcohol-only | ref. | ref. | ||||

| CAM | 0.27 | (−0.13,0.67) | ||||

| SAM | 0.39 | (0.10,0.69) | ||||

| Proportion of alcohol and marijuana months | ||||||

| CAM | ref. | ref. | ||||

| SAM | −0.29 | (−0.65,0.08) | ||||

| Within-person (time-varying) | ||||||

| Month of study (in years) | −0.08 | (−0.14,−0.03) | −0.06 | (−0.12,0.00) | 0.01 | (−0.07,0.10) |

| Quantity/frequency of alcohol use | 0.02 | (−0.03,0.06) | 0.09 | (0.02,0.15) | ||

| Marijuana use occasions | 0.03 | (−0.02,0.07) | ||||

| Pattern of substance use | ||||||

| Neither alcohol nor marijuana | ref. | ref. | ||||

| Alcohol-only | −0.12 | (−0.19,−0.04) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Marijuana-only | 0.12 | (−0.05,0.29) | ||||

| CAM | −0.05 | (−0.16,0.06) | 0.05 | (−0.03,0.13) | ref. | ref. |

| SAM | −0.03 | (−0.13,0.08) | 0.09 | (0.01,0.17) | 0.05 | (−0.04,0.15) |

| Random effects | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Intercept variance | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.04 | |||

| Within-person variance | 1.14 | 1.06 | 1.09 | |||

Note. SAM=simultaneous alcohol and marijuana; CAM=concurrent alcohol and marijuana but not simultaneous use. Bold typeface indicates fixed effect p<.05

3.5. Poor general health

In the first two models for poor general health (Table 4), the proportion of months that were SAM months had positive estimated effects (B = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.56 and B = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.18, 0.55); that is, a higher proportion of SAM months was associated with worse health. Differences between substance use patterns in a particular month and poor health were all statistically non-significant (Table 4; third panel of Figure 1). In the model based on alcohol-use months, proportion of months that were CAM months was also positively associated with poor health (B = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.04, 0.56). The model contrasting SAM with CAM suggested that the difference between the two patterns was not large at either the between-person (B = 0.02, 95% CI = −0.22,0.26) or within-person level (B = 0.02, 95% CI = −0.04,0.09).

Table 4.

Multilevel linear predicting poor general health.

| Fixed effects | All months (n = 14,528 person months among 767 individuals) | Alcohol-use months (n = 11,229 person months among 748 individuals) | Months in which both alcohol and marijuana used (n = 4,268 person months among 534 individuals) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | |

| Between person | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.22 | (1.02,1.42) | 1.41 | (1.18,1.64) | 1.06 | (0.87,1.25) |

| Female | 0.32 | (0.22,0.42) | 0.28 | (0.17,0.39) | 0.29 | (0.15,0.43) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White (reference) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.03 | (−0.11,0.17) | 0.02 | (−0.13,0.16) | 0.02 | (−0.20,0.24) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.06 | (−0.08,0.20) | 0.05 | (−0.09,0.20) | 0.19 | (0.01,0.38) |

| Hispanic | 0.08 | (−0.10,0.25) | 0.07 | (−0.10,0.24) | 0.17 | (−0.04,0.37) |

| Age in years | 0.01 | (−0.02,0.04) | 0.01 | (−0.03,0.04) | −0.01 | (−0.05,0.03) |

| Proportion of all months | ||||||

| Alcohol use | −0.28 | (−0.53,−0.02) | ||||

| Both alcohol and marijuana use | 0.01 | (−0.28,0.29) | ||||

| Person average substance use | ||||||

| Alcohol use quantity/frequency | 0.00 | (−0.09,0.10) | 0.00 | (−0.11,0.10) | ||

| Marijuana use occasions | 0.08 | (0.01,0.14) | ||||

| Proportion of all months | ||||||

| Neither alcohol nor marijuana | ref. | ref. | ||||

| Alcohol-only | −0.09 | (−0.32,0.15) | ||||

| Marijuana-only | 0.42 | (−0.18,1.02) | ||||

| CAM | 0.08 | (−0.26,0.42) | ||||

| SAM | 0.31 | (0.06,0.56) | ||||

| Proportion of alcohol-use months | ||||||

| Alcohol-only | ref. | ref. | ||||

| CAM | 0.30 | (0.04,0.56) | ||||

| SAM | 0.37 | (0.18,0.55) | ||||

| Proportion of alcohol and marijuana months | ||||||

| CAM | ref. | ref. | ||||

| SAM | 0.02 | (−0.22,0.26) | ||||

| Within-person (time-varying) | ||||||

| Month of study (in years) | 0.08 | (0.04,0.11) | 0.09 | (0.05,0.13) | 0.11 | (0.05,0.17) |

| Quantity/frequency of alcohol use | 0.03 | (0.00,0.06) | 0.03 | (−0.02,0.08) | ||

| Marijuana use occasions | 0.00 | (−0.03,0.03) | ||||

| Pattern of substance use | ||||||

| Neither alcohol nor marijuana | ref. | ref. | ||||

| Alcohol-only | 0.03 | (−0.03,0.08) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Marijuana-only | 0.08 | (−0.02,0.17) | ||||

| CAM | 0.00 | (−0.07,0.08) | −0.04 | (−0.10,0.02) | ref. | ref. |

| SAM | 0.01 | (−0.06,0.09) | −0.03 | (−0.09,0.03) | 0.02 | (−0.04,0.09) |

| Random effects | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Intercept variance | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.43 | |||

| Within-person variance | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.54 | |||

Note. SAM=simultaneous alcohol and marijuana; CAM=concurrent alcohol and marijuana but not simultaneous use. Bold typeface indicates p<.05

4. Discussion

Our study adds to research suggesting that simultaneous use of alcohol and marijuana is associated with negative effects of alcohol compared to using alcohol-only or using both alcohol and marijuana but not on the same occasion. Individuals who engaged in SAM in more months reported more alcohol-related negative consequences on average, and SAM in a particular month was associated with more negative consequences during that month. Follow-up analyses pointed to risk associated with SAM across physical, social, and decision-making consequences. This study extends prior research that has shown SAM on a particular day or occasion to be associated with more alcohol-related consequences (e.g., Egan et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020; Linden-Carmichael et al., 2020).

We found less support for the hypothesis that SAM would be uniquely associated with worse mental and physical health. SAM accompanied more depressive symptoms and worse general health than using alcohol exclusively, but neither of these outcomes differed for SAM compared to CAM. Thus, there was little evidence that SAM use, in particular, over and above marijuana use, led to worse mental and general health. Models contrasting CAM and SAM for depressive symptoms and general health indicated that average frequency of marijuana use was positively associated with worse outcomes. Further, among the patterns of substance use, the relatively rare pattern of marijuana-only use was associated with the highest levels of depressive symptoms, and alcohol-only was associated with the lowest levels of depressive symptoms. Marijuana use among young adults may be more strongly associated with negative emotions than alcohol use (Rhew, Cadigan, & Lee, 2021), rooted in bidirectional effects of marijuana use worsening mental health and marijuana being used to cope with negative emotions. In contrast, drinking alcohol during this developmental period often occurs while socializing with friends (McCabe et al., 2014; Skrzynski & Creswell, 2020) and may be a marker for positive peer relationships.

4.1. Limitations

Data came from a community sample of alcohol users in a state where nonmedical marijuana was legal for adults over the age of 21. The sample offered variability in behaviors of interest, but the unique characteristics may limit generalizability. Additional limitations include reliance on self-report data, a two-item measure of depressive symptoms, a one-item measure of general health that is broad and subjective, and a measure of marijuana use that did not include information on amount of use on particular occasions.

4.2. Conclusions

This study found that simultaneous use of alcohol and marijuana was associated with worse consequences of alcohol use both on average across a two-year time period and with respect to monthly co-variation in consequences and substance use patterns. Associations between patterns of substance use and mental and general health problems were observed, but these associations did not point to riskiness of SAM in particular. One implication is that SAM use should be taken into account when assessing shorter- and longer-term risk for negative alcohol-related consequences. A sustained pattern of SAM indicates risk for alcohol-related problems, and individuals who display this sustained pattern could be targeted for interventions. At the within-person level, month-to-month variability in SAM use may be tied to increases in alcohol-related problems in particular months. Strategies such as just-in-time adaptive interventions aimed at providing individualized support based on a person’s changing internal and contextual state (Nahum-Shani et al., 2018) might be useful. Although implications are less straightforward with respect to mental and general health, patterns and amount of substance use should also be considered when addressing these outcomes. Overall, for instance, our findings may point to marijuana use as an indicator of risk factor for depressive symptoms and poor general health.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Individuals who engaged in simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (SAM) in more months had more negative alcohol-related consequences on average

Negative alcohol-related consequences were worse in the particular months in which SAM occurred

Compared to using alcohol exclusively, SAM was positively associated with depressive symptoms and poorer general health on average across two years and with depressive symptoms at the monthly level

SAM did not substantially differ from using both alcohol and marijuana in the same month but not simultaneously with respect to depressive symptoms or general health

Author Agreement.

Data collection for the project described was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grants R01AA022087 (PI Lee). Manuscript preparation was supported by NIAAA grant R01AA027496 (PI: Lee). Partial support for this research also came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, P2C HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA, the National Institutes of Health, or the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, & Neighbors C (2013). A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JM, Robinson J, & Sareen J (2009). Self-medication of mood disorders with alcohol and drugs in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of affective disorders, 115(3), 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP (2016). The real dangers of marijuana. National Affairs,(Winter 2016), 2134. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings C, Beard C, Habarth JM, Weaver C, & Haas A (2019). Is the sum greater than its parts? Variations in substance-related consequences by conjoint alcohol-marijuana use patterns. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 51(4), 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth JC, & Lee CM (2019). Associations among simultaneous and co-occurring use of alcohol and marijuana, risky driving, and perceived risk. Addictive Behaviors, 96, 39–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan KL, Cox MJ, Suerken CK, Reboussin BA, Song EY, Wagoner KG, & Wolfson M (2019). More drugs, more problems? Simultaneous use of alcohol and marijuana at parties among youth and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 202, 69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2012). Missing data: Analysis and design: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Grønbæk M (2009). The positive and negative health effects of alcohol-and the public health implications. Journal of Internal Medicine, 265(4), 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, & Cella D (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 18(7), 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, & Smyth D (2017). Magnitude and trends in heavy episodic drinking, alcohol-impaired driving, and alcohol-related mortality and overdose hospitalizations among emerging adults of college ages 18–24 in the United States, 1998–2014. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(4), 540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan DH, & World Health Organization Management of Substance Dependence Team. (2001). Global status report: alcohol and young people. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66795

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Cadigan JM, & Patrick ME (2017). Differences in reporting of perceived acute effects of alcohol use, marijuana use, and simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Patrick ME, Fleming CB, Cadigan JM, Abdallah DA, Fairlie AM, & Larimer ME (2020). A Daily Study Comparing Alcohol-Related Positive and Negative Consequences for Days With Only Alcohol Use Versus Days With Simultaneous Alcohol and Marijuana Use in a Community Sample of Young Adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(3), 689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden-Carmichael AN, Stamates AL, & Lau-Barraco C (2019). Simultaneous use of alcohol and marijuana: Patterns and individual differences. Substance Use and Misuse, 54(13), 2156–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden-Carmichael AN, Van Doren N, Masters LD, & Lanza ST (2020). Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use in daily life: Implications for level of use, subjective intoxication, and positive and negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipperman-Kreda S, Gruenewald PJ, Grube JW, & Bersamin M (2017). Adolescents, alcohol, and marijuana: Context characteristics and problems associated with simultaneous use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Kroenke K, & Gräfe K (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, Frank KA, & Boyd CJ (2014). Social Contexts of Substance Use Among U.S. High School Seniors: A Multicohort National Study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(6), 842–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrin GJ, Thompson K, & Leadbeater BJ (2018). Transitions in the use of multiple substances from adolescence to young adulthood. Drug and alcohol dependence, 189, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Tam TW, & Weisner C (2007). Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(1), 72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2003). Recommended alcohol questions. Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions.

- Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, & Murphy SA (2018). Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 446–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, & Abbott RD (2004).Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(2), 204–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Fairlie AM, & Lee CM (2018). Motives for simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among young adults. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, & Lee CM (2018). Cross-faded: Young adults’ language of being simultaneously drunk and high. Cannabis (Research Society on Marijuana), 1(2), 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Rhew IC, Lewis MA, Abdallah DA, Larimer ME, Schulenberg JE, & Lee CM (2018). Alcohol motivations and behaviors during months young adults experience social role transitions: Microtransitions in early adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Lee CM, & Schulenberg JE (2019). Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among underage young adults in the United States. Addictive Behaviors, 88, 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, & Dale C (2016). Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Current Addiction Reports, 3(1), 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, & Colder CR (2006). Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(1), 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhew IC, Cadigan JM, & Lee CM (2021). Marijuana, but not alcohol, use frequency associated with greater loneliness, psychological distress, and less flourishing among young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, L. (2017). Stata 15.1 for Windows. 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845. USA: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzynski CJ, & Creswell KG (2020). Associations between solitary drinking and increased alcohol consumption, alcohol problems, and drinking to cope motives in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 115(11), 1989–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, & Kerr WC (2015). Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(5), 872–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (2014). Alcohol and marijuana use patterns associated with unsafe driving among US high school seniors: High use frequency, concurrent use, and simultaneous use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(3), 378–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, & Patrick ME (2018). Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among young adult drinkers: age-specific changes in prevalence from 1977 to 2016. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(11), 2224–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S, Mota N, Bolton J, & Sareen J (2018). Self-medication with alcohol or drugs for mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review of the epidemiological literature. Depression and anxiety, 35(9), 851–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, & Weiss SR (2014). Adverse health effects of marijuana use. The New England journal of medicine, 370(23), 2219–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.