Abstract

A PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism strategy directed against the pbp2b gene was evaluated for identification of penicillin susceptibility. A total of 106 United Kingdom (U.K.), 30 Danish, and 11 Papua New Guinean strains were tested. Of the U.K. strains, all the susceptible and all but one of the resistant isolates were correctly assigned. By using conventional definitions of “not resistant” and “not susceptible,” the sensitivities were 97.5 and 94.4%, the specificities were 100 and 98.9%, the positive predictive values were 100 and 94.4%, and the negative predictive values were 93.1 and 98.9%, respectively. This technique may allow susceptible (MIC, <0.1 mg/liter) and resistant (MIC, >1 mg/liter) isolates to be distinguished in a single PCR.

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains an important human pathogen associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The case fatality rates are 5 to 7% for hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia, 20% for bacteremia, and up to 40% for meningitis (1). S. pneumoniae was once universally susceptible to penicillin, but since being first identified as an important clinical problem in the late 1970s resistance has risen inexorably throughout the world (2). Treatment in response to a diagnosis of relative penicillin resistance requires either an increase in dosage, as in the case of pneumonia, or a change to a third-generation cephalosporin, as in the case of meningitis. It is important that the laboratory rapidly identifies penicillin resistance.

Conventional culture-based susceptibility testing can be difficult to perform, although national and international standards have now been published (9, 10). Several DNA amplification-based techniques have been described that use a combination of pbp2B and lytA PCRs as targets (11). Alternatively, a combination of a pbp1a PCR directed towards a resistant genotype and PCRs directed towards susceptible genotypes of pbp2b and -2x has been used (7). A restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) strategy has also been investigated and has been shown to be valuable in molecular epidemiological studies at the national and hospital levels (5). In this paper we present data which show that this technique can be modified to reliably differentiate susceptible and resistant organisms and can be used to complement PCR diagnosis (4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 106 S. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from a community-wide study from the United Kingdom (U.K.). In addition, 11 isolates from Papua New Guinea and 30 isolates from Denmark were also studied. The U.K. isolates were obtained from blood cultures (70), sputum (23), bronchoalveolar lavage (1), lung abscess (1), pleural fluid (1), ear swabs (4), wound swabs (2), throat swab (1), nasal swab (1), cerebrospinal fluid (1), and joint fluid (1). The age range of the patients from whom the isolates were obtained was 18 months to 92 years. The serotyping was performed by the Streptococcal Reference Laboratory of the Central Public Health Laboratory, Colindale, London, United Kingdom. The resistant U.K. strains had serotypes of 6B, 9, 9V, 19F, 23, and 23F. The resistant Denmark strain serotypes were 9V, 14, and 23F. The serotypes of the U.K. intermediately resistant strains were 6B, 8, 15, 15B, 19, 22, 23, and 24. The serotypes of the Denmark intermediately resistant strains were 12F, 14, 15A, 15C, 19A, 19F, 23F, and 63. The U.K. susceptible strains showed a total of 27 different serotypes. The serotypes of the two Denmark susceptible strains were 19A and 6B.

DNA isolation.

S. pneumoniae was cultivated on blood agar in 5 to 10% carbon dioxide at 37°C overnight. Colonies were emulsified in 50 μl of sterile distilled water in a microcentrifuge tube and then incubated at 95°C for 5 min in a PCR machine; supernatant containing DNA was used for PCRs.

PCRs.

The PCRs were modified from a previously published protocol (5). The pbp2b gene was amplified with primers 5′ GAT CCT CTA AAT GAT TCT CAG GTG G 3′ and 5′ CAA TTA GCT TAG CAA TAG GTG TTG G 3′. The primers were supplied high-pressure liquid chromatography purified by R & D Systems (Europe) Limited.

The optimal reaction mix included 1 U of Taq polymerase (Bioline, London, United Kingdom), 10 μl (100 mM) of ammonium sulfate buffer, 3 μl (5 mM) of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom), 3 μl (5 mM) magnesium chloride (Bioline), 4 μl of primers (0.1 mM), 5 μl of DNA template, and sterile distilled water to a final volume of 100 μl. This was overlaid with mineral oil and processed on an Omnigene thermocycler (Hybaid, London, United Kingdom). The optimal PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min. The final cycle was run at 72°C for 7 min. A total of 10 μl of the products of the PCR was analyzed by electrophoresis through a 1.8% agarose–ethidium bromide-containing gel with pGEM molecular weight standards (Promega) as markers.

The PCR products were digested with HinfI (Promega). The digestion mixture consisted of 1 μl of HinfI enzyme (10 U per μl) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–60 mM sodium chloride–7 mM magnesium chloride–0.1-mg bovine serum albumin per liter in a 50-μl volume. A total of 20 μl of PCR product was added to 2 μl of buffer and 1 μl of HinfI enzyme. Digestion proceeded for 16 h at 37°C with the Omnigene thermocycler, and the products were run on a 1.8% agarose gel as described above.

Determination of MICs.

MICs were determined by an agar dilution method according to the British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy guidelines (10). A 6-h culture of test organisms in brain heart infusion broth was diluted and inoculated with a multipoint inoculator to give 104 organisms per spot onto Isosensitest agar containing 5% lysed horse blood and differing concentrations of penicillin. The concentrations of organisms were confirmed by using the Miles and Misra technique (7). The Oxford strain of Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 6571) was used as a control. The concentrations of penicillin used ranged from 0.09 to 1.2 mg/liter by increments of 0.1 and then from 1.2 to 2.0 mg/liter by increments of 0.2. Above and below these levels doubling dilutions were performed. The MIC was determined as the concentration in last plate showing growth of less than 10 colonies. Isolates were defined as susceptible with an MIC of <0.1 mg/liter, intermediately resistant with an MIC of 0.1 to <1 mg/liter, and resistant with an MIC of >1 mg/liter.

Analysis of RFLP patterns.

RFLP patterns were digitized by using a Hewlett- Packard Scanjet 4C/T, and the band positions were analyzed using the Gel Compar program version 4.0 (Applied Maths, Krotrijk, Belgium). pGEM markers were used as the reference standards. The band positions were normalized, and dendrograms were calculated by using the dice coefficient with band settings of minimal profiling of 5%, minimal area of 0.5%, band comparison settings of position tolerance of 2%, increase 0, and minimal area 0. These conditions were chosen to give similarities between the markers of >90%.

RESULTS

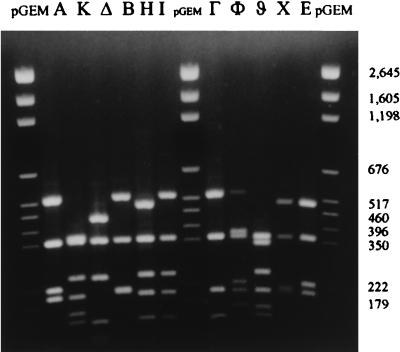

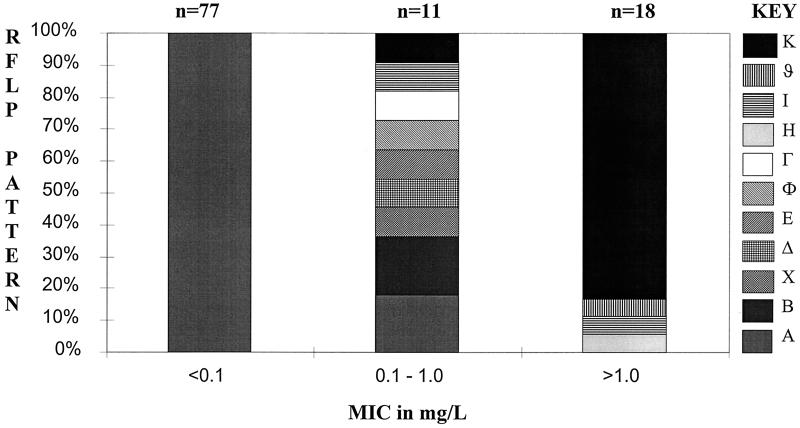

For the U.K. isolates a total of 11 different RFLP patterns could be defined for the pbp2b gene with Gel Compar. These are illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 77 susceptible organisms produced an identical pattern: pattern A. The 11 intermediately resistant strains (as defined by MIC) exhibited nine different RFLP patterns: 6 had patterns that were only found in intermediately resistant strains; 2 had pattern A, found in all of the susceptible strains; and 2 had patterns I and K, which were associated with resistant strains. Among the 18 resistant strains, all but 3 exhibited a similar genotype: pattern K. The three remaining resistant strains showed patterns H, I, and ϑ. The MICs and RFLP patterns of the U.K. isolates are illustrated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 1.

Examples of all RFLP patterns obtained by HinfI digestion of S. pneumoniae pbp2b.

FIG. 2.

Penicillin susceptibilities (MICs) and HinfI RFLP patterns for U.K. isolates of S. pneumoniae.

We used pattern A to define PCR susceptibility and an MIC of <0.1 mg/liter to define conventional susceptibility. This is illustrated in Table 1. With these figures the PCR-RFLP methodology has a sensitivity of 97.5%, a specificity of 100%, a positive predictive value of 94.4%, and a negative predictive value of 98.9%. This is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Performance characteristics of the PBP2b PCR-PCR-RFLP test to determine susceptibility and resistance

| Susceptibility (MIC) | No. of isolates with indicated susceptibility pattern by PCR-RFLP test

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Nonsusceptible | Resistant | Nonresistant | |

| Susceptible (<0.1 mg/liter) | 77 | 2a | ||

| Intermediately resistant-resistant (>0.1 mg/liter) | 0 | 27 | ||

| Resistant (>1.0 mg/liter) | 17 | 1b | ||

| Intermediately susceptible-susceptible (<1.0 mg/liter) | 1c | 87 | ||

Both isolates were intermediately resistant.

A single isolate with this pattern was also intermediately resistant (see Discussion).

This strain showed pattern K, the most common resistance pattern.

To determine the ability of this technique to detect resistance, we defined PCR resistance as pattern K, H, or ϑ and conventional resistance as an MIC of >1.0 mg/liter. Defined thus, the PCR-RFLP methodology has a sensitivity of 94.4%, a specificity of 98.9%, a positive predictive value of 94.4%, and a negative predictive value of 98.9%. This is summarized in Table 1.

Among the 30 isolates from Denmark five different RFLP patterns were observed. Only two of the organisms were susceptible, having MICs of 0.09 mg/liter, and both of these expressed pattern A. There were 14 resistant strains, 11 of which exhibited pattern K and 3 of which exhibited pattern H; both patterns had previously been associated with resistant strains among U.K. isolates. Among the 14 intermediately resistant strains, 8 showed pattern A (the susceptible pattern), a single strain demonstrated the resistant pattern K, and 2 had patterns that were previously associated with intermediate resistance in the U.K. isolates. The 11 isolates from Papua New Guinea were either susceptible or intermediately resistant. All six susceptible strains exhibited pattern A. A total of four of five intermediately resistant strains had pattern A, and one had a pattern previously associated with intermediate resistance.

DISCUSSION

Several different approaches have been adopted for the molecular diagnosis of penicillin resistance. Ubukata et al. used a combination of PCRs that were targeted on lytA, a 240-bp fragment from the pbp of susceptible strains, and two different penicillin mutant pbp2b gene sequences (11). Another group used primers based on susceptible pbp2x genes and a resistant pbp1a gene (6). By using the data provided in these publications it is possible to calculate the performance parameters for these tests. These data are found in Table 2 and show that all of these approaches are excellent at verifying fully susceptible strains. This is as expected because of the genetic conservation of penicillin-susceptible genes (2). On the other hand, both fully PCR-based systems had difficulty detecting resistant isolates. All of the resistant isolates identified were truly resistant, but those strains with a sequence not encompassed by the primers were not amplified and thus gave false-negative results. This problem is overcome by our method as the primer design is based on a sequence which is conserved in susceptible and resistant strains. Thus, genes from susceptible and resistant isolates are amplified. It is then possible to determine resistance because the pattern of endonuclease digestion differs enough between different resistant alleles. This was aided by a limited number of resistant RFLPs, all but three of which were pattern K although the isolates belonged to four different serogroups.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of performance characteristics among PCR-based diagnostic methodsa

| Study (reference) | Detection of sensitive isolates (MIC <0.1 or 0.125 mg/liter)

|

Detection of resistant isolates (MIC >1.0 mg/liter)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

| Ubukata et al. (11) | 98.8 | 100 | 100 | 98.4 | 77.9 | 97.5 | 89.8 | 91.1 |

| Jalal et al. (6) | 100 | 91.2 | 92.0 | 89.6 | 63.1 | 100 | 100 | 73.4 |

| This studyb | 97.5 | 100 | 100 | 93.1 | 94.4 | 98.9 | 94.4 | 98.8 |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Data for U.K. isolates only.

The PCR-RFLP method has the best sensitivity and specificity of the molecular methods, but these data may be an underestimate of the sensitivity. Pattern I, found in a single intermediately resistant and a single resistant strain, was defined as intermediate resistance, and therefore the resistant strain was considered a false negative. It may be that this is a resistant pattern, and thus, study of more strains from a wide geographical area should show whether this is a resistant or an intermediately resistant pattern, thereby possibly improving the specificity of the method. This study shows that there is sufficient diversity between susceptible and resistant isolates for these to be clearly distinguished.

One of the major difficulties with all of the previously reported molecularly based susceptibility tests concerns the identification of resistance in strains from overseas (6). Our RFLP methodology appeared not to have this difficulty as we were able to correctly identify both susceptible strains and 14 resistant strains from Denmark. This needs to be tested further by examining strains from many more countries. We did have difficulty in correctly identifying intermediately resistant strains as 8 of the 14 intermediately resistant strains were identified as susceptible and 1 was identified as resistant. Similarly, all susceptible strains from Papua New Guinea were correctly identified but four of five intermediately resistant strains were identified as susceptible. The recently reported technique of du Plessis et al., for application to cultures and cerebrospinal fluid, uses a seminested technique with species-specific conserved primers and four resistance primers for pbp2b. This technique was evaluated on 35 isolates, identifying all of the resistant isolates correctly (3).

All previously reported techniques require multiple PCR amplifications. Our method uses a single reaction, which has previously been shown to be species specific (5). Thus, incorrectly identified streptococcal species will not amplify, alerting the scientist to the need to check the identification. All of the molecular methods have difficulty in identifying strains that are intermediately resistant.

Although this technique used a 16-h incubation it could be accelerated by performing the digestion with a higher concentration of HinfI. This change would provide a method which would be more rapid than the conventional agar-based approach. As more isolates are examined their RFLP patterns can be added to our database. It is hoped that this will allow more accurate detection of intermediately resistant isolates in the future, thus providing a molecularly based method of susceptibility testing in a single PCR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Royal Free Hospital Special Trustees and the Wellcome Trust.

We are grateful to Deborah Lehman and Jørgen Henrichsen for the supply of strains and to Therese Donnelly for secretarial support. We gratefully acknowledge the help of the Streptococcal Reference Laboratory of the Central Public Health Laboratory, Colindale, London, United Kingdom, for serotyping.

REFERENCES

- 1.Austrian A. The enduring pneumococcus: unfinished business and opportunities for the future. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:111–115. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowson C G, Coffey T J, Spratt B G. Origin and molecular epidemiology of penicillin binding protein mediated resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:361–366. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.du Plessis M, Smith A M, Klugman K P. Rapid detection of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in cerebrospinal fluid by a seminested-PCR strategy. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:453–457. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.453-457.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillespie S H, Ullman C, Smith M D, Emery V. Detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae in sputum samples by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1308–1311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1308-1311.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillespie S H, McHugh T D, Hughes J E, Dickens A, Kyi M S, Kelsey M. An outbreak of penicillin resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae investigated by a polymerase chain reaction based genotyping method. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:847–851. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jalal H, Organji S, Reynolds J, Bennett D, O’Mason E, Millar M R. Determination of penicillin susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Pathol Mol Pathol. 1997;50:45–50. doi: 10.1136/mp.50.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miles A A, Misra S S. The estimation of the bactericidal power of blood. J Hyg Camb. 1938;38:732–749. doi: 10.1017/s002217240001158x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munoz R, Musser J M, Crain M, Briles D E, Marton A, Parkinson A J, Sorenson U, Tomasz A. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:112–118. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standards M7-A3. 3rd ed. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Report of a Working Party. 1991. A guide to sensitivity testing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 27 (Suppl. D):1–50. [PubMed]

- 11.Ubukata K, Asahi Y, Yamane A, Konno M. Combinational detection of autolysin and penicillin-binding protein 2B genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:592–596. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.592-596.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]