Abstract

Background

Environmental fluctuation during embryonic and fetal development can permanently alter an organism’s morphology, physiology, and behaviour. This phenomenon, known as developmental plasticity, is particularly relevant to reptiles that develop in subterranean nests with variable oxygen tensions. Previous work has shown hypoxia permanently alters the cardiovascular system of snapping turtles and may improve cardiac anoxia tolerance later in life. The mechanisms driving this process are unknown but may involve epigenetic regulation of gene expression via DNA methylation. To test this hypothesis, we assessed in situ cardiac performance during 2 h of acute anoxia in juvenile turtles previously exposed to normoxia (21% oxygen) or hypoxia (10% oxygen) during embryogenesis. Next, we analysed DNA methylation and gene expression patterns in turtles from the same cohorts using whole genome bisulfite sequencing, which represents the first high-resolution investigation of DNA methylation patterns in any reptilian species.

Results

Genome-wide correlations between CpG and CpG island methylation and gene expression patterns in the snapping turtle were consistent with patterns observed in mammals. As hypothesized, developmental hypoxia increased juvenile turtle cardiac anoxia tolerance and programmed DNA methylation and gene expression patterns. Programmed differences in expression of genes such as SCN5A may account for differences in heart rate, while genes such as TNNT2 and TPM3 may underlie differences in calcium sensitivity and contractility of cardiomyocytes and cardiac inotropy. Finally, we identified putative transcription factor-binding sites in promoters and in differentially methylated CpG islands that suggest a model linking programming of DNA methylation during embryogenesis to differential gene expression and cardiovascular physiology later in life. Binding sites for hypoxia inducible factors (HIF1A, ARNT, and EPAS1) and key transcription factors activated by MAPK and BMP signaling (RREB1 and SMAD4) are implicated.

Conclusions

Our data strongly suggests that DNA methylation plays a conserved role in the regulation of gene expression in reptiles. We also show that embryonic hypoxia programs DNA methylation and gene expression patterns and that these changes are associated with enhanced cardiac anoxia tolerance later in life. Programming of cardiac anoxia tolerance has major ecological implications for snapping turtles, because these animals regularly exploit anoxic environments throughout their lifespan.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13072-021-00414-7.

Introduction

The environment that an organism experiences in early life can have profound and long-lasting effects on their phenotype. This phenomenon, termed developmental plasticity, allows animals to permanently alter their morphology, physiology and behaviour in response to environmental signals [1]. In many cases, developmental plasticity provides organisms with a powerful mechanism to cope with environmental heterogeneity later in life [2]. However, unexpected or severe environmental stress during development can produce maladaptive phenotypes that increase disease susceptibility [3]. Despite the profound ecological implications of developmental plasticity, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms remain poorly defined.

Due to the profound health implications, most studies investigating developmental plasticity have focused on mammalian models of disease [4]. However, environmental variation during development is much more common in ectothermic animals, particularly oviparous species [5, 6]. These animals typically develop with little or no parental care and are routinely subjected to wide variations in abiotic factors such as temperature, water availability and atmospheric gases [7]. In particular, oviparous reptile nests can become severely hypoxic due to a progressive decline in nest oxygen tension from embryonic metabolism and microbial activity [8, 9]. The extent of hypoxia is nest-specific, but field estimates suggest reptilian eggs located farthest from the surface can be subjected to oxygen tensions as low as 11%, while those at the top of the nest remain at atmospheric oxygen (21%) [10]. Similar to other vertebrates, developmental hypoxia significantly alters turtle morphology and physiology, particularly at the level of the cardiovascular system [11–15]. Embryonic turtles exposed to hypoxia have different intrinsic heart rates and variable expression of receptors involved in cardiac regulation [11, 13, 16–19]. Furthermore, the effects of developmental hypoxia extend into juvenile and adult life, affecting cardiac performance and physiological traits [14, 15]. Of particular note, our recent study suggests juvenile turtles from hypoxic incubations possess cardiomyocyte specialisations that improve anoxia tolerance [20]. The programming of cardiac anoxia tolerance has major ecological implications for turtles, because many freshwater species, including Chrysemys picta, Trachemys scripta, and Chelydra serpentina, regularly engage in breath-hold dives that last several hours at warm temperatures, and they overwinter in anoxia for up to 5 months in ice-covered lakes [21, 22]. Even when metabolic rate and body temperature are taken into account, these freshwater turtles can survive anoxia 1000 times longer than a similarly sized mammal [23]. The maintenance of cardiac function is crucial for anoxia survival to ensure the delivery of nutrients and the removal of waste [24]. Therefore, early exposure to hypoxia may prime turtle heart physiology for a future life in anoxic environments.

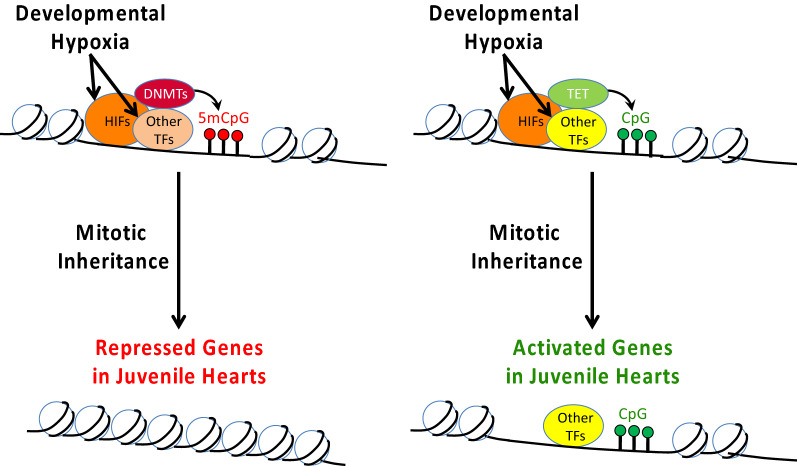

The molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac programming in turtles are completely unknown but may involve epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Post-translational histone modifications and DNA methylation are the primary epigenetic marks shown to play a role in development and differentiation [25–27]. These marks regulate gene expression patterns, cell-fate decisions, and cellular physiology by altering DNA accessibility and chromatin structure. For example, trimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 4 (H3K4me3) at promoters is associated with gene activation, while trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) is a repressive mark [28]. At least 70 different histone marks have been identified, each having unique effects on gene expression. The complexity of the histone code contrasts with the relative simplicity of DNA methylation, which is associated with transcriptional repression. DNA methylation is thought to inhibit transcription by interfering with transcription factor (TF) binding, though TF binding might reciprocally inhibit DNA methylation [29, 30]. Moreover, histone modifications and DNA methylation are interdependent, so de novo DNA methylation patterns laid down during embryogenesis help set the stage for maintenance of DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications through repeated cell divisions and into postnatal life [31, 32].

DNA methylation is a particularly stable, long-term mark that might be subject to environmental modification during development [33]. The most common mark is methylation of cytosines adjacent to guanines (i.e., CpG dinucleotides). Individual CpGs are typically methylated, while CpGs in clusters, called CpG islands (CGIs), are usually, though not always, found in an unmethylated state. The impact of CpG and CGI methylation on gene expression also depends upon their location within the genome. Recent work, for instance, has shown that enhancers and silencers display different patterns of CpG methylation and that orphan CGIs can act as potent enhancers [34–36]. This is on top of the classical observation that 60–70% of promoters contain CGIs [37].

Developmental hypoxia is known to alter DNA methylation and gene expression patterns in mammals, and the molecular signature is associated with cardiac abnormalities in adulthood [38, 39]. Therefore, programming of cardiac anoxia tolerance in snapping turtles may be achieved by similar mechanisms. Very little is currently known about DNA methylation landscapes in reptiles, because prior studies have almost exclusively measured global DNA methylation levels. We found one study that examined spatial patterns using MeDIP-Seq in the painted turtle, Chrysemys picta [40]. Key observations were that CpG distribution is bimodal in turtle promoters, as in other vertebrates [41], and that there is differential CpG methylation between hatchling ovaries and testes, including methylation differences in putative sex-determining genes. While MeDIP-Seq provides an overview of the methylation landscape at an affordable cost, it is an enrichment-based technique with shortcomings in terms of quantitatively measuring methylation levels and presenting a biased representation of the genome [42]. More importantly, we could not find a single study describing the most fundamental relationships between DNA methylation and gene expression patterns in reptiles.

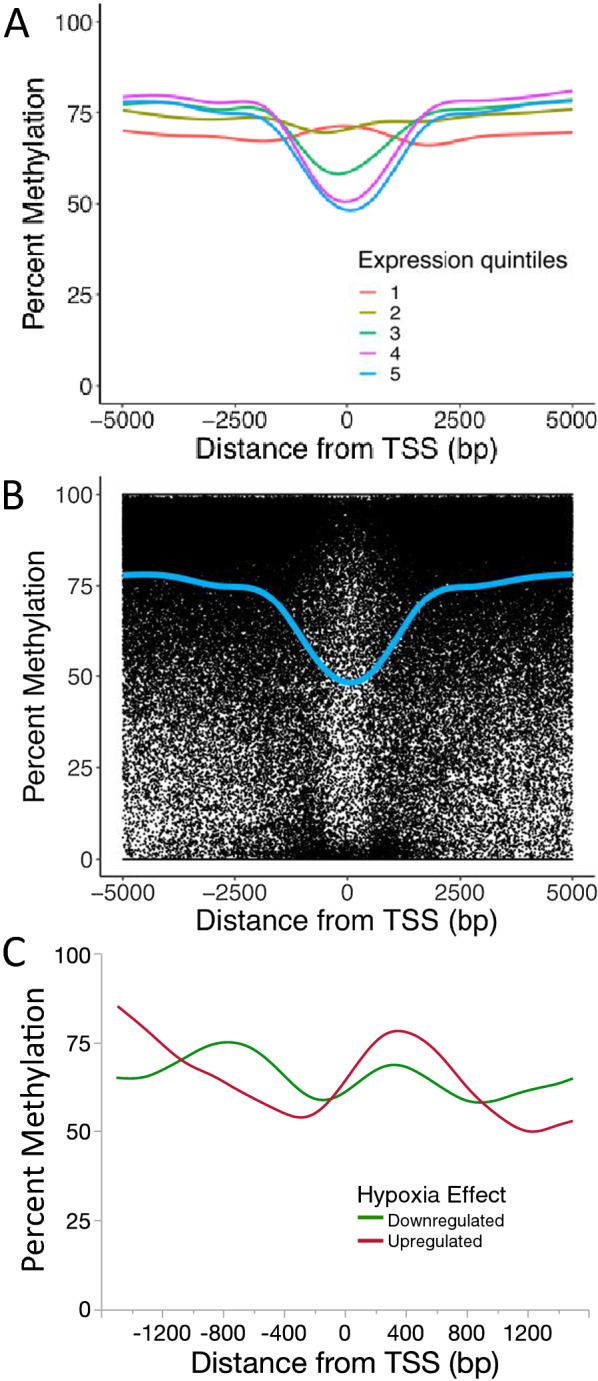

In this study, we hypothesised that developmental hypoxia alters DNA methylation and gene expression patterns in turtles and that these patterns are associated with greater cardiac anoxia tolerance later in life. Snapping turtles take 9 to 18 years to reach sexual maturity, which makes it impractical to study developmental programming in adults. Instead, we tested for effects that persist in juvenile turtles months after their embryonic exposure to hypoxic conditions. To directly test these hypotheses, we first assessed cardiac performance during 2 h of acute anoxia in juvenile turtles previously exposed to normoxia (21% oxygen: N21) or hypoxia (10% oxygen: H10) during embryonic development. Next, we measured DNA methylation patterns in heart ventricles from the same cohorts using whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), the “gold standard” for DNA methylation analyses, as well as gene expression patterns using RNA-Seq. These experiments represent the first high-resolution investigation of DNA methylation patterns in any reptilian species. As hypothesized, developmental hypoxia increased juvenile turtle cardiac anoxia tolerance and programmed CpG and CGI methylation and gene expression patterns. DNA methylation and gene expression were broadly correlated at a genome-wide scale (e.g., genes with higher methylation at their promoters displayed lower expression, while those with lower promoter methylation displayed higher expression). In addition, genes that were differentially methylated between turtles from normoxic and hypoxic incubations were significantly more likely to be differentially expressed. The results suggest developmental hypoxia can programme turtle cardiovascular phenotype, spanning from molecular to physiological levels, which has important ecological implications for species that exploit anoxic environments.

Results

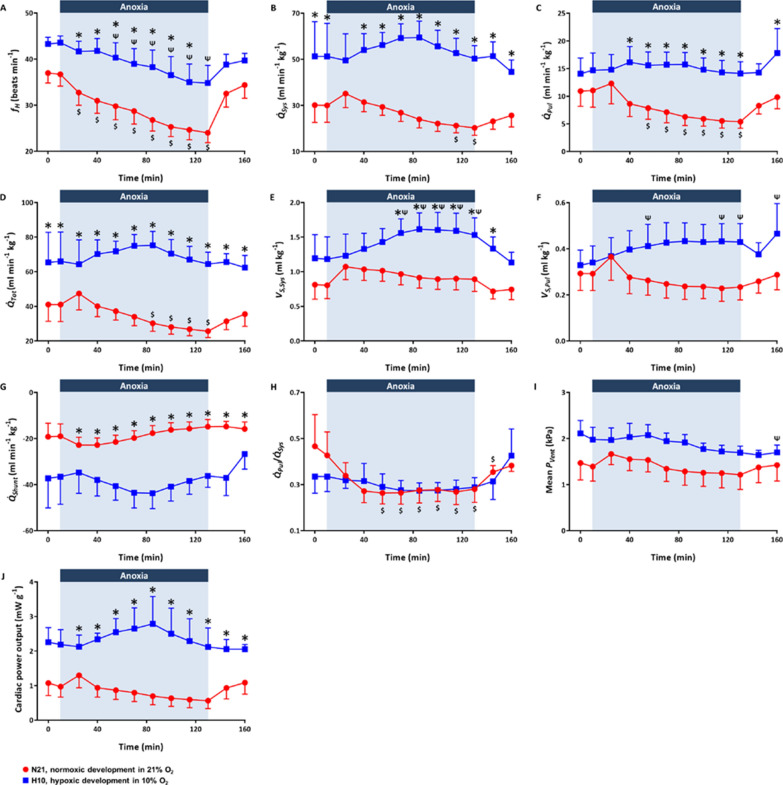

Developmental hypoxia improves cardiac anoxia tolerance

Body and heart masses of juvenile turtles used for in situ studies of cardiovascular physiology are provided in Table 1. Acute exposure to anoxia caused a progressive bradycardia (i.e., decreased heart rate) in both experimental groups (Fig. 1A), but the magnitude of this response was significantly greater in N21 (34 ± 6%) vs. H10 (20 ± 10%) turtles. A decrease in heart rate in low oxygen environments is a key feature of the “diving reflex”, which aids in the conservation of oxygen stores in air breathing vertebrates. In the N21 group, bradycardia was associated with a progressive reduction in systemic blood flow () and pulmonary blood flow () (Fig. 1B, C), while systemic stroke volume () and pulmonary stroke volume () remained relatively constant (Fig. 1E, F). The reduction in pulmonary blood flow () in N21 turtles during anoxia was proportionately greater than the reduction in systemic blood flow (), leading to an increase in the right-to-left (R–L) shunt of blood from the pulmonary to the systemic circulation (Fig. 1H). Turtles are able to physiologically control the outflow of blood through the pulmonary artery vs. systemic arteries (i.e., left and right aortas), because they have a three chambered heart with a single ventricle that is only partially divided by vertical and horizontal septa. An increase in R–L shunting recirculates systemic venous blood and bypasses the pulmonary circuit, while greater left-to-right (L–R) shunting recirculates blood through the pulmonary circuit. Changes in shunting may allow more efficient regulation of blood gases during periods of activity vs. rest [43]. Despite a significant reduction in total blood flow () in N21 turtles (Fig. 1D), there was only a small non-significant reduction in cardiac power output (Fig. 1J), while mean ventricular pressure remained relatively constant (Fig. 1I).

Table 1.

Body and heart masses of juvenile snapping turtles exposed to normoxia (N21) or hypoxia (H10) during embryonic development

| Cohort | Body mass (g) | Heart mass (mg) | Heart-to-body-mass ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| N21 | 308.8 ± 24.5 | 648.7 ± 67.1 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| H10 | 314.9 ± 52.2 | 713.4 ± 115.9 | 0.23 ± 0.01* |

Significant differences were revealed by generalized linear models, followed by Sidak post-hoc tests, for multiple comparisons, and are denoted by asterisks (*), when P ≤ 0.05

Fig. 1.

Effects of acute anoxia and reoxygenation on haemodynamic variables from N21 and H10 turtles. Turtles from the N21 (red circles, n = 6) and H10 (blue squares, n = 5) cohorts were subjected to 120 min of anoxia followed by 30 min reoxygenation. A Heart rate (), B systemic blood flow (), C pulmonary blood flow (), D total blood flow (), E systemic stroke volume (), F pulmonary stroke volume (), G shunt distribution (), H shunt ratio (), I mean ventricular pressure (), and J cardiac power output. Values are mean ± SEM, asterisks (*) indicate statistically significance difference between N21 and H10 groups, dollar ($) and psi (Ψ) symbols denote a significant difference between that data point and pre-anoxic levels (time zero) in the N21 and H10 groups, respectively (p ≤ 0.05)

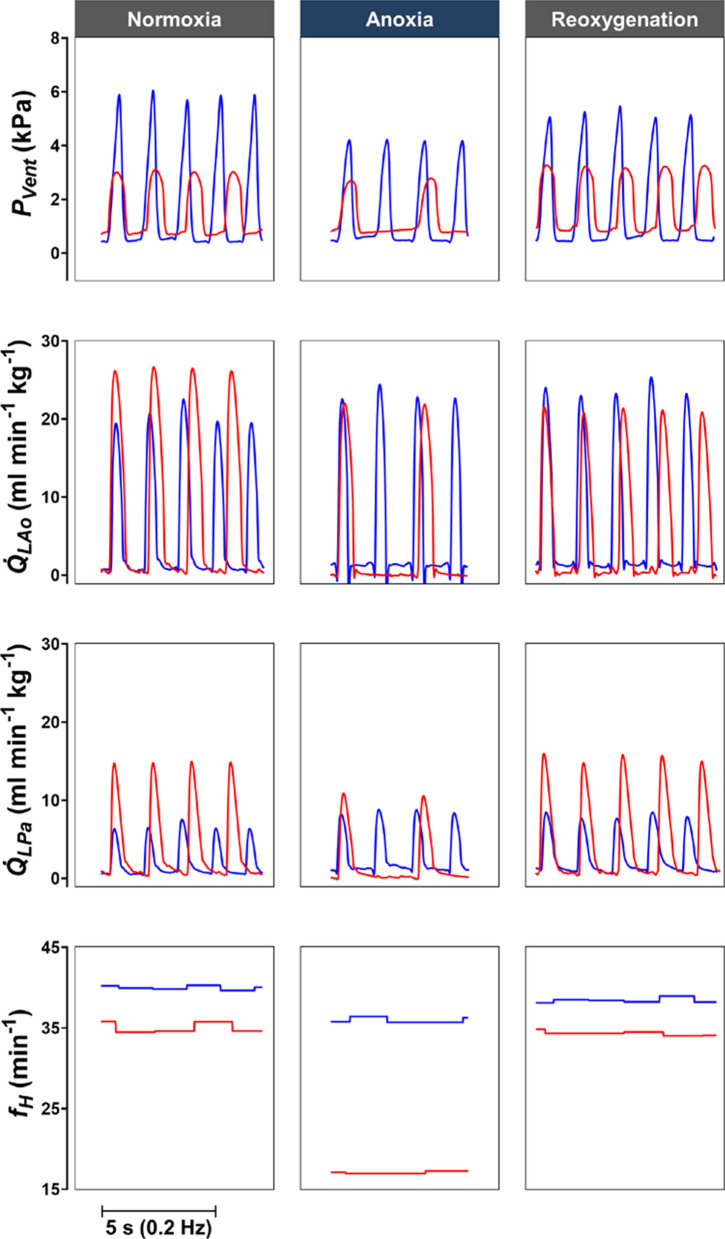

Apart from the “diving reflex” (i.e., bradycardia), other cardiovascular responses in H10 turtles were quite distinct from N21 turtles. Surprisingly, the anoxic bradycardia in H10 turtles was not associated with any changes in systemic () or pulmonary () blood flow or the R–L shunt, which all changed in N21 turtles. This meant that systemic () and pulmonary () stroke volumes were significantly elevated in H10 turtles during acute anoxia (Fig. 2). As a result of the elevated stroke volume, mean ventricular pressure and cardiac power output was maintained during 2 h of anoxia in H10 turtles (Fig. 1I, J). Therefore, the H10 group maintained higher blood flows, systemic stroke volume, and heart rate (, , , )and cardiac power output than the N21 cohort throughout the anoxic period (Figs. 1 and 2). In the N21 group, all haemodynamic variables reverted to normoxic levels after 30 min of reoxygenation (Fig. 1). For the H10 group, mean ventricular pressure was slightly depressed at the end of reoxygenation (Fig. 1I), and remained elevated (Fig. 1F), while all other haemodynamic variables returned to normoxic levels (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Original traces of the effects of anoxia and reoxygenation on cardiac haemodynamic variables. Ventricular pressure (), left aortic arch blood flow (), left pulmonary artery blood flow () and heart rate () were measured in N21 (red lines) and H10 (blue lines) turtles during 10-min normoxia, 120-min anoxia, and 20-min reoxygenation

In addition to influencing responses to anoxia and reoxygenation, developmental hypoxia altered resting cardiovascular variables in snapping turtles, similar to previous reports [14]. While all haemodynamic variables fell within previously published in situ and in vivo values from Chelydra, Chrysemys, and Trachemys [14, 44], anaesthetised H10 turtles had significantly greater resting systemic blood flow (QSys)than N21 turtles, leading to a larger R–L shunt, elevated total blood flow (QTot) and elevated cardiac power output (Fig. 1, pre-anoxic levels). All the other haemodynamic variables were similar between experimental groups.

Embryonic hypoxia programs transcriptome-wide patterns of gene expression

Transcriptome-wide patterns of gene expression were investigated in 7- and 9-month-old snapping turtles previously exposed to hypoxia (H10, n = 8) or normoxia (N21, n = 8) during embryonic development. Within the hypoxic cohort, turtles had two distinct cardiac phenotypes; normal-sized (n = 4) and enlarged (n = 4) hearts, relative to their body size. Gene expression within both cohorts was found to be significantly affected by age, relative heart size, and embryonic oxygen concentration. Firstly, oxygen concentration during embryogenesis altered expression of 151 genes in juvenile turtles: 75 genes were up-regulated and 76 genes were down-regulated in ventricles from the H10 group, relative to the N21 group (Table 2). Ninety-seven genes displayed significant oxygen concentration by age interactions (Table 3) and 13 of these genes were also influenced by the main effect of oxygen concentration. Finally, 256 genes were differentially expressed between ventricles from normal-sized vs. enlarged hearts (47 of these genes were among the genes listed above). A total of 131 genes were up-regulated in ventricles of enlarged hearts, while 125 genes were down-regulated (Table 4). Altogether, there were 443 differentially expressed genes.

Table 2.

Genes that were differentially expressed between ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles exposed to normoxia (N21) or hypoxia (H10) during embryonic development

| Locus # | Gene name | Gene symbol | Log2 (H10/N21) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS000018264 | Zinc finger family member 783 | − 2.834627001 | |

| CS000001503 | − 2.701680389 | ||

| CS000000288 | Myosin heavy chain 7 | − 2.041584511 | |

| CS000024278 | RALY RNA-binding protein-like | RALYL | − 1.527633917 |

| CS000008734 | Mast cell proteinase-3 | − 1.496662823 | |

| CS000015120 | − 1.356777695 | ||

| CS000017586 | Zinc finger protein 3 | − 1.273941158 | |

| CS000023536 | C-type lectin-domain family 2, member e | − 1.208247243 | |

| CS000009112 | Calcium-binding protein 5 | CABP5 | − 1.181213024 |

| CS000003610 | Serine/threonine kinase 32A | STK32A | − 1.121027915 |

| CS000017023 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor B2 | − 1.110900385 | |

| CS000011584 | Tripartite motif containing 58 | − 1.045883825 | |

| CS000002712 | Pseudouridylate synthase 1 | PUS1 | − 1.035714387 |

| CS000021405 | − 1.006176746 | ||

| CS000020555 | Granzyme H | GZMH | − 0.853897751 |

| CS000010063 | General transcription factor IIA subunit 1-like | GTF2A1L | − 0.792335632 |

| CS000018042 | Tribbles pseudokinase 1 | TRIB1 | − 0.765772922 |

| CS000008605 | Contactin associated protein 1 | CNTNAP1 | − 0.743987654 |

| CS000022576 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 2 (G2m marker) | − 0.740245463 | |

| CS000002010 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 2-like | − 0.731931571 | |

| CS000016349 | Zinc finger protein 3 | − 0.722476444 | |

| CS000011191 | Deoxyribonuclease 1-like 3 | DNASE1L3 | − 0.710756946 |

| CS000002882 | Short chain dehydrogenase (predicted) | − 0.697002063 | |

| CS000004234 | Lysozyme C-like | − 0.694683419 | |

| CS000019361 | Sperm flagellar 2 | − 0.637371303 | |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 | − 0.625646157 |

| CS000022673 | Centrosomal protein 295 | − 0.621246238 | |

| CS000010768 | MAM domain containing 4 | MAMDC4 | − 0.616068017 |

| CS000002550 | Family with sequence similarity 217 member B | FAM217B | − 0.606523849 |

| CS000021864 | PZP, alpha-2-macroglobulin-like | − 0.600912295 | |

| CS000022474 | Dedicator of cytokinesis 2 | − 0.593278276 | |

| CS000007572 | − 0.564178825 | ||

| CS000002388 | Suppression of tumorigenicity 14 | ST14 | − 0.563702692 |

| CS000010941 | Coiled-coil domain containing 40 | CCDC40 | − 0.526253468 |

| CS000018526 | Modulator of smoothened protein | MOSMO | − 0.507345817 |

| CS000008639 | Kell blood group, metallo-endopeptidase | KEL | − 0.501729677 |

| CS000008272 | − 0.500144159 | ||

| CS000013388 | Coiled-coil domain containing 69 | − 0.488161437 | |

| CS000023033 | Calcitonin receptor | CALCR | − 0.478006366 |

| CS000013081 | PR/SET domain 8 | PRDM8 | − 0.470914245 |

| CS000010506 | NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 2 | NQO2 | − 0.470257899 |

| CS000010015 | Proteolipid protein 1 | PLP1 | − 0.451285412 |

| CS000009837 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 1 | PFKFB1 | − 0.445995285 |

| CS000013172 | Sperm flagellar 2 | SPEF2 | − 0.405206127 |

| CS000007175 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 | ADGRL3 | − 0.390432656 |

| CS000018864 | Zinc finger protein 3 | − 0.387733152 | |

| CS000003471 | DNA damage inducible transcript 4-like | DDIT4L | − 0.381244306 |

| CS000013715 | THAP domain containing 9 | THAP9 | − 0.367754654 |

| CS000016980 | Leucine rich repeat containing 8 family member D | LRRC8D | − 0.360578313 |

| CS000024331 | Ceramide synthase 4 | CERS4 | − 0.329175611 |

| CS000004429 | Diphthamide biosynthesis 7 | DPH7 | − 0.31321296 |

| CS000024488 | Endogenous retrovirus group MER34 member 1 | − 0.283738212 | |

| CS000002360 | Activating transcription factor 1 | ATF1 | − 0.279120084 |

| CS000015148 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 10 | TNFSF10 | − 0.25585253 |

| CS000001723 | ATM serine/threonine kinase | ATM | − 0.249457117 |

| CS000014235 | Anthrax toxin receptor 2 | ANTXR2 | − 0.244822743 |

| CS000023516 | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit | HIF1A | − 0.237980337 |

| CS000010455 | SURF1, cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor | SURF1 | − 0.222451553 |

| CS000021833 | Rho GTPase activating protein 45 | ARHGAP45 | − 0.221222304 |

| CS000013956 | Tribbles pseudokinase 2 | TRIB2 | − 0.217959675 |

| CS000002385 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 32 | ARHGAP32 | − 0.215929188 |

| CS000004163 | Solute carrier family 4 member 2 | SLC4A2 | − 0.212349304 |

| CS000010124 | Solute carrier family 35 member A1 | slc35a1 | − 0.20854517 |

| CS000007017 | Cingulin-like 1 | CGNL1 | − 0.198504808 |

| CS000009705 | F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 20 | FBXL20 | − 0.168085068 |

| CS000025011 | Retinoic acid receptor, alpha | 0.154424605 | |

| CS000009251 | Taxilin beta | TXLNB | 0.158953455 |

| CS000005867 | Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 | EPS8 | 0.163637442 |

| CS000023373 | Mannosidase beta | MANBA | 0.166087668 |

| CS000021122 | Sprouty related EVH1 domain containing 2 | SPRED2 | 0.170050721 |

| CS000008545 | Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 | ERBB2 | 0.187176414 |

| CS000000599 | Tubulin folding cofactor B | TBCB | 0.195969098 |

| CS000013318 | G protein subunit gamma 10 | GNG10 | 0.208058965 |

| CS000003073 | Cadherin 11, type 2, OB-cadherin (osteoblast) | 0.208906093 | |

| CS000008574 | 2′,3′-Cyclic nucleotide 3′ phosphodiesterase | CNP | 0.212460195 |

| CS000007985 | STARD3 N-terminal-like | STARD3NL | 0.219747393 |

| CS000009739 | Tropomyosin 3 | TPM3 | 0.236963141 |

| CS000024894 | Serine/threonine kinase 38-like | STK38L | 0.238422059 |

| CS000015359 | Spectrin beta, erythrocytic | 0.241602606 | |

| CS000013674 | Eva-1 homolog C | EVA1C | 0.245944042 |

| CS000010784 | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein | CETP | 0.246380083 |

| CS000010497 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 6 | 0.248181093 | |

| CS000009948 | 0.252507277 | ||

| CS000008411 | Integrin subunit alpha 11 | ITGA11 | 0.254329861 |

| CS000003646 | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 B | UBE2B | 0.254817922 |

| CS000014028 | C-type lectin-domain family 2 member D | 0.264505749 | |

| CS000011229 | Ribonuclease H2 subunit C | rnaseh2c | 0.27146634 |

| CS000023524 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 23 | 0.277562695 | |

| CS000009501 | Heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 | HS6ST2 | 0.28065352 |

| CS000005400 | Inositol-trisphosphate 3-kinase A | ITPKA | 0.29921558 |

| CS000008774 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5 | MAP3K5 | 0.309585444 |

| CS000019402 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 3 | HSPB3 | 0.328843966 |

| CS000014776 | Bardet-Biedl syndrome 1 protein | 0.33633198 | |

| CS000004507 | Cathepsin L | ctsl | 0.344555132 |

| CS000013316 | KIAA0368 | KIAA0368 | 0.353983994 |

| CS000020738 | Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent 1H | PPM1H | 0.35982697 |

| CS000010357 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 6 | KCNH6 | 0.370923213 |

| CS000000947 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 3 | PHLDA3 | 0.371384191 |

| CS000000189 | Protein kinase AMP-activated non-catalytic subunit beta 2 | PRKAB2 | 0.376457859 |

| CS000021606 | Ependymin related 1 | EPDR1 | 0.384457752 |

| CS000013259 | Centromere protein H | CENPH | 0.384685483 |

| CS000004917 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 | BMPR2 | 0.400771813 |

| CS000008544 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 7 | GRB7 | 0.443902422 |

| CS000001051 | Monooxygenase DBH-like 1 | MOXD1 | 0.459634006 |

| CS000003463 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (class II), pi polypeptide | ADH4 | 0.494122016 |

| CS000017173 | Solute carrier family 2 member 11 | SLC2A11 | 0.501060861 |

| CS000011090 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 | 0.517276571 |

| CS000021119 | Endogenous retrovirus group MER34 member 1 | 0.524982887 | |

| CS000014447 | PDZ-binding kinase | PBK | 0.542088418 |

| CS000011287 | Dual specificity protein phosphatase 10-like | 0.543863344 | |

| CS000009633 | Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | ALCAM | 0.548683718 |

| CS000010233 | EFR3 homolog B | 0.554021781 | |

| CS000001795 | Transmembrane protein 71 | TMEM71 | 0.60589964 |

| CS000001243 | Myelin basic protein | MBP | 0.606334331 |

| CS000012858 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 | SOCS2 | 0.635342108 |

| CS000001161 | Transmembrane protein 200C | tmem200c | 0.646446549 |

| CS000020994 | Transmembrane protein 151B-like | 0.64955796 | |

| CS000004537 | Charged multivesicular body protein 4C | CHMP4C | 0.649900032 |

| CS000008619 | ETS variant 4 | ETV4 | 0.668839089 |

| CS000014855 | Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G, member 2 | 0.669227747 | |

| CS000018990 | Collagen type XXII alpha 1 chain | COL22A1 | 0.675489915 |

| CS000019220 | Keratin 8 | KRT8 | 0.683602204 |

| CS000019009 | Thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 7A | THSD7A | 0.718432909 |

| CS000005131 | Glutaredoxin | GLRX | 0.740909237 |

| CS000019856 | TNF receptor associated factor 2 | 0.756354667 | |

| CS000004598 | 0.765230508 | ||

| CS000006964 | Adaptor related protein complex 1 sigma 3 subunit | AP1S3 | 0.765814686 |

| CS000021260 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 4 | KCNA4 | 0.854709853 |

| CS000003440 | Apolipoprotein C1 | apoc1 | 0.878140809 |

| CS000019191 | Interaction protein for cytohesin exchange factors 1 | IPCEF1 | 0.879401672 |

| CS000009567 | Keratin 18 | KRT18 | 0.925644492 |

| CS000022727 | Fer-1-like family member 4 | FER1L4 | 0.964212443 |

| CS000020607 | DNA polymerase nu | POLN | 1.00608115 |

| CS000018642 | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 | HABP2 | 1.034969644 |

| CS000014808 | Synaptonemal complex protein 1 | SYCP1 | 1.124476724 |

| CS000004949 | Myosin light chain 1 | MYL1 | 1.168968857 |

| CS000011884 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex assembly factor 2 | 1.298675033 | |

| CS000004501 | 1.320990056 | ||

| CS000004709 | Heparan sulfate–glucosamine 3-sulfotransferase 2 | HS3ST2 | 1.353228055 |

| CS000009646 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor G7 | ADGRG7 | 1.423863767 |

| CS000001877 | Glycoprotein nmb | GPNMB | 1.608451449 |

| CS000012011 | Coagulation factor III, tissue factor | F3 | 1.645631227 |

| CS000004554 | Complement C1r | C1R | 1.873883015 |

| CS000000330 | Matrix metallopeptidase 25 | MMP25 | 1.977548442 |

| CS000012602 | Neuritin 1 | NRN1 | 2.508897571 |

| CS000019631 | Perforin 1 | 2.667492969 | |

| CS000021046 | Complement C1r subcomponent | 2.710546811 | |

| CS000013720 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 8-like | 3.126479237 | |

| CS000010724 | LIM homeobox 5 | LHX5 | 3.176148053 |

| CS000018878 | 4.264821788 | ||

| CS000012122 | Astacin-like metalloendopeptidase | 4.556056058 | |

The difference in expression in the last column is calculated as the log2 of the ratio of gene expression in turtles exposed to hypoxia divided by gene expression in turtles exposed to normoxia during embryonic development. Negative values indicate the gene was downregulated in the hypoxic group, while positive values indicate the gene was upregulated in the hypoxic group. The transcriptome was analyzed via RNA-Seq. Differences in gene expression were considered significant when results from DESeq2 and ANOVA were concordant

Table 3.

Genes that displayed significant oxygen concentration by age interactions in ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles exposed to normoxia (N21) or hypoxia (H10) during embryonic development and sampled at 7 months or 9 months of age

| locus_number | gene_name | gene_symbol |

|---|---|---|

| CS000013624 | von Willebrand factor A domain containing 5B1 | VWA5B1 |

| CS000017075 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor D2 | ADGRD2 |

| CS000002650 | Doublecortin domain containing 1 | |

| CS000020386 | ||

| CS000005701 | Extracellular leucine rich repeat and fibronectin type III domain containing 1 | ELFN1 |

| CS000007756 | Raf-1 proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase | RAF1 |

| CS000012404 | ||

| CS000011576 | Immunity related GTPase cinema | |

| CS000017702 | ||

| CS000017791 | Gag-pol precursor polyprotein | |

| CS000005252 | Myomesin 3 | MYOM3 |

| CS000013643 | Heat shock protein 30C L homeolog | |

| CS000007769 | ||

| CS000000238 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | TPH1 |

| CS000022856 | ||

| CS000011558 | Transmembrane channel-like 5 | TMC5 |

| CS000020596 | Sortilin related VPS10 domain containing receptor 2 | SORCS2 |

| CS000004923 | CD28 molecule | CD28 |

| CS000008982 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 5 | RGS5 |

| CS000001877 | Glycoprotein nmb | GPNMB |

| CS000011960 | Crystallin alpha B | CRYAB |

| CS000000625 | HEN1 methyltransferase homolog 1 | HENMT1 |

| CS000011913 | Heat shock protein 30C L homeolog | |

| CS000021013 | Fibrous sheath interacting protein 1 | FSIP1 |

| CS000005377 | Galectin 1 | LGALS1 |

| CS000017153 | Guanylate-binding protein 2-like | |

| CS000000187 | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | PHGDH |

| CS000011024 | Target of myb1-like 1 membrane trafficking protein | TOM1L1 |

| CS000016415 | Endogenous retrovirus group V member 2 | |

| CS000011191 | Deoxyribonuclease 1 like 3 | DNASE1L3 |

| CS000003395 | Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing 18 | ASB18 |

| CS000004493 | Spindle assembly abnormal protein 6 homolog | |

| CS000024997 | Toll like receptor 6 | TLR6 |

| CS000023735 | ||

| CS000001051 | Monooxygenase DBH like 1 | MOXD1 |

| CS000000229 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily J member 11 | KCNJ11 |

| CS000001730 | Ferredoxin 1 | FDX1 |

| CS000005131 | Glutaredoxin | GLRX |

| CS000006114 | Chordin like 1 | CHRDL1 |

| CS000012086 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle-like | |

| CS000003405 | Fibronectin 1 | FN1 |

| CS000003059 | Carboxylesterase 2 | CES2 |

| CS000003128 | Cytochrome b-245 alpha chain | CYBA |

| CS000000901 | Transmembrane protein 159 L homeolog | tmem159.L |

| CS000023152 | Mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | MIB1 |

| CS000017081 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | PTGS1 |

| CS000017005 | Muskelin 1 | MKLN1 |

| CS000004866 | Myosin IB | MYO1B |

| CS000013316 | KIAA0368 | KIAA0368 |

| CS000001871 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 5 | RAPGEF5 |

| CS000015369 | Acyl-CoA-binding domain containing 6 | ACBD6 |

| CS000019402 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 3 | HSPB3 |

| CS000004507 | Cathepsin L | ctsl |

| CS000009267 | RAB32, member RAS oncogene family | RAB32 |

| CS000003646 | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 B | UBE2B |

| CS000023259 | Crystallin zeta | CRYZ |

| CS000013749 | Pitrilysin metallopeptidase 1 | PITRM1 |

| CS000024623 | Myosin VC | MYO5C |

| CS000009274 | Glycoprotein integral membrane 1 | GINM1 |

| CS000008916 | Transmembrane protein 214 | TMEM214 |

| CS000002191 | Endothelin-converting enzyme 2 | ECE2 |

| CS000002902 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor subunit 1 | GABBR1 |

| CS000011567 | Glycogen synthase 1 | GYS1 |

| CS000024960 | DExH-box helicase 9 | DHX9 |

| CS000023516 | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit | HIF1A |

| CS000009882 | Acyl-CoA oxidase 1 | ACOX1 |

| CS000017504 | Unc-5 netrin receptor A | UNC5A |

| CS000005022 | DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C11 | DNAJC11 |

| CS000003466 | tRNA methyltransferase 10A | TRMT10A |

| CS000001723 | ATM serine/threonine kinase | ATM |

| CS000007175 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 | ADGRL3 |

| CS000018314 | General transcription factor IIIC subunit 2 | |

| CS000003458 | SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, containing DEAD/H box 1 | SMARCAD1 |

| CS000015974 | Coiled-coil domain containing 130 | CCDC130 |

| CS000009858 | Arginine demethylase and lysine hydroxylase | JMJD6 |

| CS000025151 | Jumonji and AT-rich interaction domain containing 2 | JARID2 |

| CS000014359 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 26 | PEX26 |

| CS000004897 | Transmembrane protein 237 | TMEM237 |

| CS000014907 | Zinc finger protein 219 | ZNF219 |

| CS000014046 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5-like | |

| CS000011309 | Zinc finger and SCAN domains 20 | |

| CS000003047 | WD repeat domain 88 | WDR88 |

| CS000003006 | Mucolipin 3 | MCOLN3 |

| CS000008630 | ||

| CS000007667 | FXYD domain containing ion transport regulator 3 | |

| CS000003008 | Mucolipin 2 | MCOLN2 |

| CS000019541 | Chromosome 21 orf 58 | |

| CS000009617 | Transmembrane protease, serine 7 | TMPRSS7 |

| CS000019987 | Plexin A3 | |

| CS000020555 | Granzyme H | GZMH |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000011540 | von Willebrand factor A domain containing 3A | VWA3A |

| CS000021466 | ||

| CS000015152 | ||

| CS000008845 | Apolipoprotein F | APOF |

| CS000023912 | ||

| CS000020445 | UPF0061 protein xcc-b100,1894-like |

The transcriptome was analyzed via RNA-Seq. Differences in gene expression were considered significant when results from DESeq2 and ANOVA were concordant

Table 4.

Genes that were differentially expressed between ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles that had normal-sized or enlarged hearts relative to their body size

| Locus # | Gene name | Gene symbol | Log2 (enlarged/normal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS000003025 | DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member A2 | DNAJA2 | − 4.00011659 |

| CS000005942 | Mucin 2, oligomeric mucus/gel-forming | MUC2 | − 4 |

| CS000020789 | − 4 | ||

| CS000020715 | − 3.970542981 | ||

| CS000000246 | − 3.412275459 | ||

| CS000000714 | Interleukin 22 | IL22 | − 2.460702344 |

| CS000008734 | Mast cell proteinase-3 | − 2.313632939 | |

| CS000006768 | Capping protein, Arp2/3 and myosin-I linker protein 3-like | − 2.266058389 | |

| CS000018994 | Capping protein regulator and myosin 1 linker 3 | CARMIL3 | − 2.256232917 |

| CS000008168 | Glucagon | GCG | − 1.725877497 |

| CS000002882 | Short chain dehydrogenase (predicted) | − 1.68846675 | |

| CS000020555 | Granzyme H | GZMH | − 1.641521247 |

| CS000011467 | T brachyury transcription factor | TBXT | − 1.62277543 |

| CS000009580 | Advillin | AVIL | − 1.59555768 |

| CS000017383 | G protein-coupled receptor 62 | GPR62 | − 1.591541521 |

| CS000018663 | Deleted in malignant brain tumors 1 protein-like | − 1.525993727 | |

| CS000008605 | Contactin associated protein 1 | CNTNAP1 | − 1.459617958 |

| CS000010544 | C-type lectin-domain family 2 member D | CLEC2D | − 1.349128576 |

| CS000014353 | Aldo–keto reductase family 1, member C3 (3-alpha hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, type II) | − 1.341939485 | |

| CS000008622 | Sclerostin | sost | − 1.338528092 |

| CS000013408 | Solute carrier family 8 member A2 | SLC8A2 | − 1.333783678 |

| CS000012528 | Persephin | PSPN | − 1.322706586 |

| CS000009180 | CD69 molecule | CD69 | − 1.320171193 |

| CS000019803 | − 1.292382379 | ||

| CS000000790 | NFKB inhibitor like 1 | NFKBIL1 | − 1.268443921 |

| CS000020022 | Carcinoembryonic antigen related cell adhesion molecule 1 | CEACAM1 | − 1.249402634 |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 | − 1.185425524 |

| CS000012770 | Nudix hydrolase 15 | NUDT15 | − 1.174821415 |

| CS000002010 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 2-like | NR1D2 | − 1.135755617 |

| CS000012951 | Zinc finger CW-type and PWWP domain containing 1 | ZCWPW1 | − 1.131146467 |

| CS000015104 | Rho GTPase activating protein 27 | ARHGAP27 | − 1.12138132 |

| CS000009000 | Cytochrome P450 family 8 subfamily B member 1 | CYP8B1 | − 1.119197734 |

| CS000023981 | Zinc finger protein 501-like | − 1.109988843 | |

| CS000019117 | − 1.093528795 | ||

| CS000004600 | − 1.076659475 | ||

| CS000020803 | − 1.076581749 | ||

| CS000024876 | MHC class II DLA DRB1 beta chain | − 0.99585363 | |

| CS000003266 | Synaptotagmin-15 | SYT15 | − 0.992965859 |

| CS000013911 | − 0.970276375 | ||

| CS000022474 | Dedicator of cytokinesis 2 | DOCK2 | − 0.970046644 |

| CS000011784 | C-type lectin-domain family 2, member e | − 0.947959012 | |

| CS000009177 | Zinc finger protein 2 | ZNF2 | − 0.9470744 |

| CS000017654 | Junctophilin 4 | JPH4 | − 0.9449115 |

| CS000017263 | USH1 protein network component harmonin | USH1C | − 0.941279454 |

| CS000012524 | Synovial sarcoma, X breakpoint 2 interacting protein S homeolog | ssx2ip.S | − 0.939268547 |

| CS000000565 | Ras and Rab interactor-like protein | RINL | − 0.892810687 |

| CS000023033 | Calcitonin receptor | CALCR | − 0.88702029 |

| CS000016033 | Ring finger protein 25 | rnf25 | − 0.882108694 |

| CS000021269 | Neural EGFL like 1 | NELL1 | − 0.868462024 |

| CS000012971 | Neuron derived neurotrophic factor | NDNF | − 0.866800964 |

| CS000020495 | Kinase non-catalytic C-lobe domain containing 1 | KNDC1 | − 0.852740249 |

| CS000002530 | Collagen type XX alpha 1 chain | COL20A1 | − 0.843443212 |

| CS000012304 | − 0.799063985 | ||

| CS000001767 | Septin 5 | SEPTIN5 | − 0.795109503 |

| CS000013081 | PR/SET domain 8 | PRDM8 | − 0.778512974 |

| CS000024963 | Zinc finger protein 862 | ZNF862 | − 0.776513766 |

| CS000002362 | Acid sensing ion channel subunit 1 | asic1 | − 0.77548223 |

| CS000006802 | Sortilin related VPS10 domain containing receptor 1 | SORCS1 | − 0.774579369 |

| CS000003991 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 2-like | NR0B2 | − 0.752752113 |

| CS000008630 | − 0.742661864 | ||

| CS000011782 | C-type lectin-domain family 2 member D | CLEC2D | − 0.738112094 |

| CS000020166 | Tweety family member 1 | TTYH1 | − 0.727823227 |

| CS000017666 | Spectrin beta, non-erythrocytic 4 | SPTBN4 | − 0.727759339 |

| CS000019541 | Chromosome 21 orf 58 | C21orf58 | − 0.693870417 |

| CS000014966 | Ficolin 3 | FCN3 | − 0.683027443 |

| CS000007237 | Collectin subfamily member 10 | COLEC10 | − 0.67828483 |

| CS000023359 | Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator like 3 | RGL3 | − 0.676871711 |

| CS000001261 | − 0.673565294 | ||

| CS000015636 | Ecto-NOX disulfide-thiol exchanger 1 | enox1 | − 0.667186029 |

| CS000018597 | Neurexin 2 | NRXN2 | − 0.658378249 |

| CS000004183 | Kelch-like 42 | − 0.645354432 | |

| CS000005642 | Topoisomerase (DNA) III alpha | TOP3A | − 0.637881286 |

| CS000012953 | Immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat | ISLR | − 0.636348281 |

| CS000001835 | Actin-binding Rho activating protein | ABRA | − 0.622678244 |

| CS000006362 | Nicotinamide riboside kinase 2 | NMRK2 | − 0.57894428 |

| CS000000038 | KH and NYN domain containing | KHNYN | − 0.560880734 |

| CS000004606 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator like | ARNTL | − 0.550619038 |

| CS000008808 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, iron containing 1 | ADHFE1 | − 0.546993977 |

| CS000012473 | Progestin and adipoQ receptor family member 6 | PAQR6 | − 0.540783679 |

| CS000020112 | Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator-like 2 | RGL2 | − 0.528180794 |

| CS000024555 | Stimulator of chondrogenesis 1 | SCRG1 | − 0.525168151 |

| CS000003254 | Tubulin tyrosine ligase like 3 | TTLL3 | − 0.517188122 |

| CS000010967 | − 0.516398171 | ||

| CS000002912 | Tripartite motif containing 21 | TRIM21 | − 0.514703 |

| CS000016053 | Sosondowah ankyrin repeat-domain family member C | SOWAHC | − 0.50414698 |

| CS000007586 | Proline and arginine rich end leucine rich repeat protein | PRELP | − 0.495350825 |

| CS000019628 | Predicted gene 4070 | − 0.478962063 | |

| CS000000139 | Galactosidase beta 1 like | glb1l | − 0.476795916 |

| CS000009979 | Cysteine rich transmembrane BMP regulator 1 | CRIM1 | − 0.465661576 |

| CS000025399 | Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain | COL4A6 | − 0.464490703 |

| CS000014745 | Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 3 | celsr3 | − 0.458822636 |

| CS000002394 | Neurotrimin | NTM | − 0.456792451 |

| CS000024488 | Endogenous retrovirus group MER34 member 1 | ERVMER34-1 | − 0.456570624 |

| CS000002168 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 | FGFR3 | − 0.45517114 |

| CS000009429 | Endogenous retrovirus group PABLB member 1 Env polyprotein | ERVPABLB-1 | − 0.454624962 |

| CS000000163 | DNA polymerase kappa | POLK | − 0.449829124 |

| CS000000791 | TNF receptor-associated factor 2-like | − 0.446715719 | |

| CS000013923 | − 0.438881138 | ||

| CS000010076 | Tripartite motif containing 27 | TRIM27 | − 0.437359644 |

| CS000012780 | Potassium channel regulator | KCNRG | − 0.435061589 |

| CS000020545 | Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase-like | − 0.425412793 | |

| CS000018595 | Signal-induced proliferation-associated 1 | SIPA1 | − 0.420335966 |

| CS000017396 | RNA-binding motif protein 5 | RBM5 | − 0.420294548 |

| CS000015645 | Regulator of cell cycle | RGCC | − 0.410119835 |

| CS000008765 | TBC1 domain containing kinase | TBCK | − 0.409881882 |

| CS000010919 | Solute carrier family 25 member 10 | SLC25A10 | − 0.402643235 |

| CS000002886 | Collagen type XV alpha 1 chain | COL15A1 | − 0.399950238 |

| CS000013998 | Patatin like phospholipase domain containing 7 | PNPLA7 | − 0.393493799 |

| CS000009498 | Glypican 3 | GPC3 | − 0.383165019 |

| CS000025210 | Wnt family member 11 | WNT11 | − 0.382187878 |

| CS000013883 | BCL tumor suppressor 7B | BCL7B | − 0.378585114 |

| CS000023516 | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit | HIF1A | − 0.377701984 |

| CS000014058 | Collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | COL18A1 | − 0.360702793 |

| CS000017272 | RNA-binding motif protein 10 | RBM10 | − 0.359302205 |

| CS000001770 | Neuroepithelial cell transforming 1 | NET1 | − 0.352443733 |

| CS000004853 | Collagen type III alpha 1 chain | COL3A1 | − 0.328008574 |

| CS000024953 | − 0.321005944 | ||

| CS000005987 | Tyrosine kinase 2 | TYK2 | − 0.298269494 |

| CS000012361 | FUS RNA-binding protein | FUS | − 0.29508553 |

| CS000007770 | Nucleolar protein 8 | NOL8 | − 0.294633032 |

| CS000024095 | Syntrophin beta 1 | SNTB1 | − 0.294318957 |

| CS000003363 | Programmed cell death 11 | PDCD11 | − 0.264560467 |

| CS000018465 | Family with sequence similarity 234 member A | FAM234A | − 0.255178537 |

| CS000007341 | Catenin delta 1 | CTNND1 | − 0.251866178 |

| CS000012875 | LOC400927-CSNK1E readthrough | TPTEP2-CSNK1E | − 0.230967711 |

| CS000003886 | PDZ domain containing ring finger 3 | PDZRN3 | 0.22442223 |

| CS000020331 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 17 | CDK17 | 0.241724877 |

| CS000008574 | 2′,3′-Cyclic nucleotide 3′ phosphodiesterase | CNP | 0.266261699 |

| CS000015509 | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 | SCN5A | 0.310625656 |

| CS000009739 | Tropomyosin 3 | TPM3 | 0.312184844 |

| CS000025418 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A | PPIA | 0.314495662 |

| CS000023518 | MNAT1, CDK activating kinase assembly factor | MNAT1 | 0.323120508 |

| CS000013900 | N-Acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate transferase alpha and beta subunits | GNPTAB | 0.324699426 |

| CS000008711 | Synaptosome associated protein 29 | SNAP29 | 0.325626966 |

| CS000004194 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S18C | MRPS18C | 0.327277429 |

| CS000008823 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 2 | NCOA2 | 0.327760834 |

| CS000002566 | VAMP associated protein B and C | VAPB | 0.327878453 |

| CS000023702 | Prefoldin subunit 1 | PFDN1 | 0.332371862 |

| CS000008476 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 10 | GRB10 | 0.338931617 |

| CS000004780 | Amyloid beta precursor protein-binding family A member 1 | APBA1 | 0.340118016 |

| CS000006903 | Family with sequence similarity 183, member A | FAM183A | 0.340987831 |

| CS000001976 | HAUS augmin like complex subunit 8 | HAUS8 | 0.3445911 |

| CS000012782 | SPRY domain containing 7 | SPRYD7 | 0.353656911 |

| CS000011256 | Sushi domain containing 3 | SUSD3 | 0.362482561 |

| CS000013749 | Pitrilysin metallopeptidase 1 | PITRM1 | 0.38762199 |

| CS000007925 | Family with sequence similarity 118 member B | FAM118B | 0.392163014 |

| CS000020039 | Mitochondrial intermediate peptidase | MIPEP | 0.394441129 |

| CS000014649 | Hematological and neurological expressed 1 | HN1 | 0.40118652 |

| CS000003093 | Cadherin 13 | CDH13 | 0.40428373 |

| CS000008885 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 9 | NEDD9 | 0.406086208 |

| CS000009999 | HAUS augmin like complex subunit 1 | HAUS1 | 0.407190489 |

| CS000012325 | Receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 | RIPK2 | 0.407834454 |

| CS000003646 | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 B | UBE2B | 0.409403598 |

| CS000015494 | Limb development membrane protein 1 | LMBR1 | 0.413015468 |

| CS000014842 | LARGE xylosyl- and glucuronyltransferase 1 | LARGE1 | 0.418322361 |

| CS000009751 | Myosin light chain 7 | MYL7 | 0.419170988 |

| CS000003679 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 | MAPK9 | 0.422947717 |

| CS000000944 | Troponin T2, cardiac type | TNNT2 | 0.431038749 |

| CS000002295 | Family with sequence similarity 83 member H | fam83h | 0.431750631 |

| CS000007019 | Aquaporin 9 | AQP9 | 0.436004498 |

| CS000016136 | Early endosome antigen 1 | EEA1 | 0.443580231 |

| CS000023302 | Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 9 | ARHGEF9 | 0.459948169 |

| CS000021606 | Ependymin related 1 | EPDR1 | 0.477676177 |

| CS000011866 | Ras homolog family member C | RHOC | 0.481673372 |

| CS000019402 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 3 | HSPB3 | 0.490224239 |

| CS000013608 | Transmembrane protein 51 | TMEM51 | 0.490548583 |

| CS000023885 | Formin homology 2 domain containing 3 | FHOD3 | 0.495382703 |

| CS000018274 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 1 | CSRP1 | 0.498739165 |

| CS000003393 | ArfGAP with GTPase domain, ankyrin repeat and PH domain 1 | AGAP1 | 0.499342757 |

| CS000002632 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 3 | CSRP3 | 0.506402578 |

| CS000023152 | Mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | MIB1 | 0.506464289 |

| CS000005359 | Synaptotagmin 11 | SYT11 | 0.507330807 |

| CS000000947 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 3 | PHLDA3 | 0.523937739 |

| CS000000229 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily J member 11 | KCNJ11 | 0.524801955 |

| CS000020271 | Myosin, light chain 12A, regulatory, non-sarcomeric | MYL12A | 0.529612298 |

| CS000011198 | Adaptor protein, phosphotyrosine interacting with PH domain and leucine zipper 1 | APPL1 | 0.535485261 |

| CS000000757 | Testis development related protein | TDRP | 0.552047882 |

| CS000005687 | G protein subunit alpha 12 | GNA12 | 0.556060953 |

| CS000000925 | Nicotinamide riboside kinase 2-like | 0.559479152 | |

| CS000020993 | TYRO3 protein tyrosine kinase | TYRO3 | 0.560184602 |

| CS000009817 | Rho related BTB domain containing 2 | RHOBTB2 | 0.561224935 |

| CS000011090 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 | 0.562276569 |

| CS000006432 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 | GPX4 | 0.570135795 |

| CS000000499 | Myopalladin | MYPN | 0.570884545 |

| CS000007378 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 | HSPB1 | 0.57397187 |

| CS000012962 | Protease, serine 12 | PRSS12 | 0.583446299 |

| CS000005505 | SIVA1 apoptosis inducing factor | SIVA1 | 0.584199204 |

| CS000023280 | Sorbin and SH3 domain containing 2 | SORBS2 | 0.592192854 |

| CS000008152 | LY75-CD302 readthrough | LY75-CD302 | 0.601643015 |

| CS000006114 | Chordin like 1 | CHRDL1 | 0.606688517 |

| CS000005009 | Ring finger protein 207 | RNF207 | 0.606887706 |

| CS000004917 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 | BMPR2 | 0.608134843 |

| CS000008531 | Digestive cysteine proteinase 2-like | 0.608312906 | |

| CS000000963 | Cardiac-enriched FHL2-interacting protein | CUNH10orf71 | 0.619320903 |

| CS000020738 | Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent 1H | PPM1H | 0.625433587 |

| CS000001051 | Monooxygenase DBH like 1 | MOXD1 | 0.627515741 |

| CS000019311 | Protein kinase C alpha | PRKCA | 0.628980813 |

| CS000010890 | Family with sequence similarity 169 member A | FAM169A | 0.647101757 |

| CS000023075 | CD109 molecule | CD109 | 0.649459241 |

| CS000005076 | 0.653243213 | ||

| CS000014425 | B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase | BRAF | 0.65486808 |

| CS000004507 | Cathepsin L | ctsl | 0.655047104 |

| CS000012086 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle-like | ACTA2 | 0.670113468 |

| CS000013316 | KIAA0368 | KIAA0368 | 0.692998191 |

| CS000018070 | Male germ cell associated kinase | MAK | 0.700509414 |

| CS000012890 | Sestrin 3 | SESN3 | 0.706989256 |

| CS000003989 | Pleckstrin homology domain interacting protein | PHIP | 0.710494062 |

| CS000017173 | Solute carrier family 2 member 11 | SLC2A11 | 0.732703259 |

| CS000020613 | Ribosomal protein S18-like | 0.73789984 | |

| CS000009633 | Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | ALCAM | 0.742827537 |

| CS000011644 | DNA polymerase zeta catalytic subunit | REV3L | 0.770984303 |

| CS000004444 | RAB33A, member RAS oncogene family | RAB33A | 0.780890859 |

| CS000014388 | BICD cargo adaptor 1 | BICD1 | 0.789743481 |

| CS000019543 | 0.821651965 | ||

| CS000009594 | UDP glycosyltransferase 8-like | UGT8L | 0.823852981 |

| CS000008337 | Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent 1L | PPM1L | 0.848557469 |

| CS000009656 | Collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain | COL8A1 | 0.897700653 |

| CS000006655 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 | GRK3 | 0.898389538 |

| CS000012858 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 | SOCS2 | 0.945191217 |

| CS000010981 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 5 | ABCA5 | 0.957982052 |

| CS000001795 | Transmembrane protein 71 | TMEM71 | 0.991430672 |

| CS000023496 | AHNAK nucleoprotein 2 | AHNAK2 | 0.996386481 |

| CS000003395 | Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing 18 | ASB18 | 1.000007423 |

| CS000019856 | TNF receptor associated factor 2 | TRAF2 | 1.000486113 |

| CS000004132 | Low density lipoprotein receptor class A domain containing 4 | LDLRAD4 | 1.016079793 |

| CS000018434 | 1.023357895 | ||

| CS000021605 | Secreted frizzled related protein 4 | SFRP4 | 1.024078897 |

| CS000004537 | Charged multivesicular body protein 4C | CHMP4C | 1.033646338 |

| CS000009567 | Keratin 18 | KRT18 | 1.107725712 |

| CS000018802 | LanC like 3 | LANCL3 | 1.116482677 |

| CS000005377 | Galectin 1 | LGALS1 | 1.139460825 |

| CS000014226 | MOB kinase activator 1B | MOB1B | 1.171832671 |

| CS000018642 | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 | HABP2 | 1.185512417 |

| CS000006855 | Transforming acidic coiled-coil-containing protein 2 | TACC2 | 1.237644425 |

| CS000005131 | Glutaredoxin | GLRX | 1.274526454 |

| CS000022717 | Fibrinogen C domain containing 1 | FIBCD1 | 1.354378958 |

| CS000024186 | Leucine rich repeat containing 3B | LRRC3B | 1.366458011 |

| CS000011960 | Crystallin alpha B | CRYAB | 1.397658976 |

| CS000013643 | Heat shock protein 30C L homeolog | 1.419468073 | |

| CS000018346 | Abnormal spindle microtubule assembly | ASPM | 1.420184199 |

| CS000014980 | Complement factor B | CFB | 1.459428513 |

| CS000011910 | Heat shock protein 30C L homeolog | 1.508403744 | |

| CS000008585 | Heat shock protein, alpha-crystallin-related, b11 | 1.521530969 | |

| CS000005252 | Myomesin 3 | MYOM3 | 1.56777953 |

| CS000012224 | TNF receptor associated factor 3 | TRAF3 | 1.605321051 |

| CS000021043 | Complement C1s | C1S | 1.630815717 |

| CS000013370 | Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 3 | entpd3 | 1.743604465 |

| CS000004501 | 1.793715013 | ||

| CS000007782 | Musculoskeletal, embryonic nuclear protein 1 | mustn1 | 1.852375511 |

| CS000022000 | Mast cell proteinase-1 | CPT1B | 1.895535655 |

| CS000016407 | Fc fragment of IgG-binding protein | FCGBP | 1.955167136 |

| CS000012089 | CD59 Molecule (CD59 Blood Group)-like | CD59 | 2.005971296 |

| CS000001877 | Glycoprotein nmb | GPNMB | 2.090003205 |

| CS000025123 | Mast cell proteinase-3 | 2.432617325 | |

| CS000000238 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | TPH1 | 2.525652753 |

| CS000006963 | Secretogranin II | SCG2 | 3.207453439 |

The difference in expression in the last column is calculated as the log2 of the ratio of gene expression in enlarged hearts divided by gene expression in normal-sized hearts. Negative values indicate the gene was downregulated in enlarged hearts, while positive values indicate the gene was upregulated in enlarged hearts. The transcriptome was analyzed via RNA-Seq. Differences in gene expression were considered significant when results from DESeq2 and ANOVA were concordant

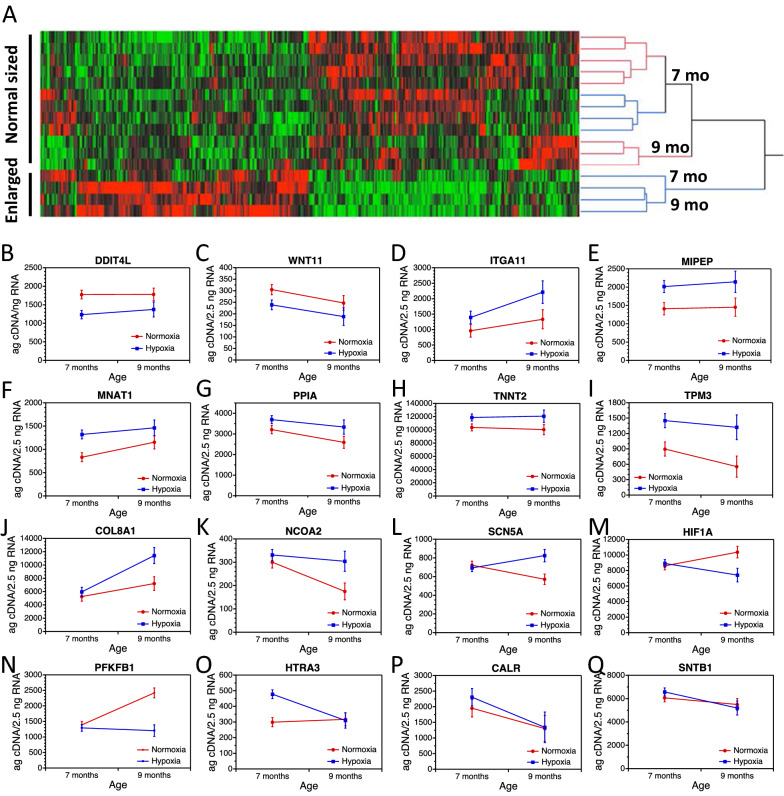

Hierarchical clustering of these genes by expression pattern showed separation of normal-sized from enlarged hearts (i.e., the two deepest branches in the dendrogram in Fig. 3A). There was also separation between younger and older turtles (the next deepest branches in the dendrogram). Finally, two distinct clusters contained the N21 and H10 groups from 7-month-old turtles (separation of red and blue branches in top half of the dendrogram). Overall, this pattern of clustering reflected clear expression differences between N21 and H10 groups.

Fig. 3.

Gene expression patterns in ventricles of 7-month-old and 9-month-old snapping turtles that had been incubated in normoxic or hypoxic conditions as embryos. Samples from the N21 cohort are shown with red circles and red lines, while the H10 cohort is shown with blue circles and blue lines. A Heatmap of RNA-Seq expression values for the 443 genes that were significantly affected by oxygen concentration during embryogenesis (Table 2), the oxygen concentration by age interaction (Table 3), and/or differed between ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles that had normal-sized or enlarged hearts relative to their body size (Table 4). Reverse transcription of total RNA and qPCR with rigorous standard curves were used to measure expression of 16 genes (B–Q) identified as differentially expressed in the RNA-Seq study. Significant differences between oxygen groups or oxygen by age interactions were confirmed for 14 genes (panels B through O), but not for 2 genes (panels P and Q). Expression levels are least squares means (± 1 SE) for each oxygen group at 7 and 9 months of age

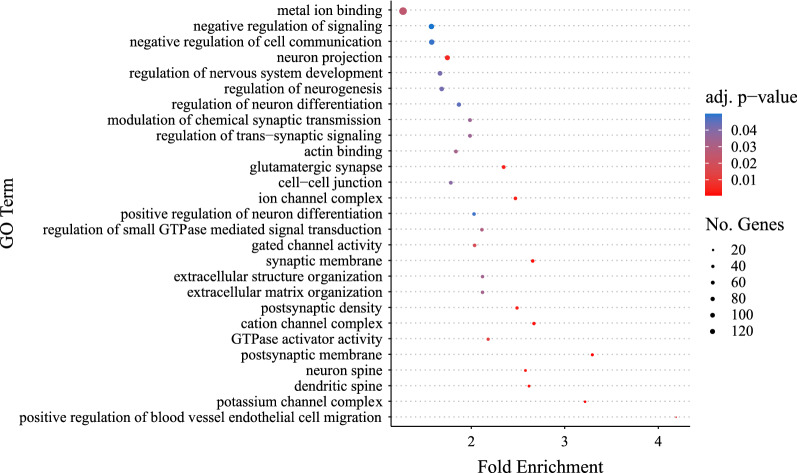

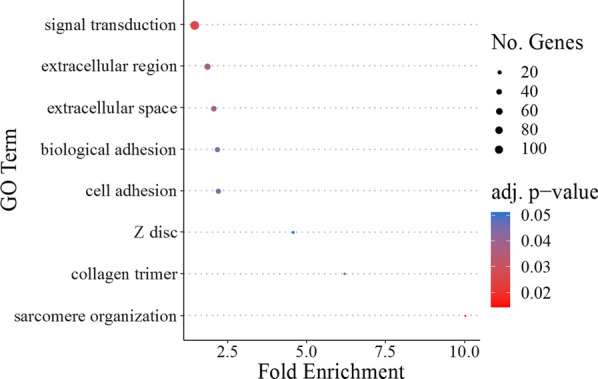

Differentially expressed genes were enriched for several GO terms important for cardiac function and/or remodeling (Fig. 4). For GO Biological Processes, this included 8 differentially expressed genes that play a role in sarcomere organization, 33 genes that play a role in biological adhesion/cell adhesion, and 118 genes involved in signal transduction (Fig. 4; Table 5). For GO Cellular Components, 9 differentially expressed genes form collagen trimers, 11 genes are part of the Z-disc, 41 genes are found in the extracellular space, and 50 genes are part of the extracellular region (Fig. 4; Table 6). Several genes across different GO categories are candidates that might play a role in promoting cardiac anoxia tolerance in the H10 group.

Fig. 4.

Gene Ontology terms significantly enriched among genes that were differentially expressed in ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles that had been incubated in normoxic or hypoxic conditions as embryos. Enrichment analysis was carried out on all 443 genes that were affected by oxygen concentration during embryogenesis (Table 2), the oxygen concentration by age interaction (Table 3), and/or those genes that differed between ventricles from turtles that had normal-sized vs. enlarged hearts relative to their body size (Table 4). The number of genes for each GO term is represented by the size of the circle, while the FDR adjusted p value is shown by the color of the circle

Table 5.

GO biological process terms and genes that were enriched among differentially expressed genes in ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles

| locus_number (in snapping turtle) | gene_name | gene_symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Sarcomere organization | ||

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000018274 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 1 | CSRP1 |

| CS000002632 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 3 | CSRP3 |

| CS000023885 | Formin homology 2 domain containing 3 | FHOD3 |

| CS000019220 | Keratin 8 | KRT8 |

| CS000005252 | Myomesin 3 | MYOM3 |

| CS000000499 | Myopalladin | MYPN |

| CS000000944 | Troponin T2, cardiac type | TNNT2 |

| Cell adhesion = biological adhesion | ||

| CS000007175 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 | ADGRL3 |

| CS000009633 | Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | ALCAM |

| CS000004780 | Amyloid beta precursor protein-binding family A member 1 | APBA1 |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000003073 | Cadherin 11, type 2, OB-cadherin (osteoblast) | CDH11 |

| CS000003093 | Cadherin 13 | CDH13 |

| CS000014745 | Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 3 | celsr3 |

| CS000008605 | Contactin associated protein 1 | CNTNAP1 |

| CS000002886 | Collagen type XV alpha 1 chain | COL15A1 |

| CS000014058 | Collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | COL18A1 |

| CS000004853 | Collagen type III alpha 1 chain | COL3A1 |

| CS000025399 | Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain | COL4A6 |

| CS000009656 | Collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain | COL8A1 |

| CS000018274 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 1 | CSRP1 |

| CS000007341 | Catenin delta 1 | CTNND1 |

| CS000021606 | Ependymin related 1 | EPDR1 |

| CS000003405 | Fibronectin 1 | FN1 |

| CS000001877 | Glycoprotein nmb | GPNMB |

| CS000018642 | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 | HABP2 |

| CS000007378 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 | HSPB1 |

| CS000012953 | Immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat | ISLR |

| CS000008411 | Integrin subunit alpha 11 | ITGA11 |

| CS000009567 | Keratin 18 | KRT18 |

| CS000017005 | Muskelin 1 | MKLN1 |

| CS000020271 | Myosin, light chain 12A, regulatory, non-sarcomeric | MYL12A |

| CS000000499 | myopalladin | MYPN |

| CS000008885 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 9 | NEDD9 |

| CS000018597 | Neurexin 2 | NRXN2 |

| CS000002394 | Neurotrimin | NTM |

| CS000019311 | Protein kinase C alpha | PRKCA |

| CS000011090 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 |

| CS000020166 | Tweety family member 1 | TTYH1 |

| CS000020993 | TYRO3 protein tyrosine kinase | TYRO3 |

| Signal transduction | ||

| CS000017075 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor D2 | ADGRD2 |

| CS000009646 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor G7 | ADGRG7 |

| CS000007175 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 | ADGRL3 |

| CS000003393 | ArfGAP with GTPase domain, ankyrin repeat and PH domain 1 | AGAP1 |

| CS000009633 | Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | ALCAM |

| CS000011198 | Adaptor protein, phosphotyrosine interacting with PH domain and leucine zipper 1 | APPL1 |

| CS000002385 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 32 | ARHGAP32 |

| CS000021833 | Rho GTPase activating protein 45 | ARHGAP45 |

| CS000023302 | Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 9 | ARHGEF9 |

| CS000003395 | Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing 18 | ASB18 |

| CS000001723 | ATM serine/threonine kinase | ATM |

| CS000013883 | BCL tumor suppressor 7B | BCL7B |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000004917 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 | BMPR2 |

| CS000014425 | B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase | BRAF |

| CS000009112 | Calcium-binding protein 5 | CABP5 |

| CS000023033 | Calcitonin receptor | CALCR |

| CS000004923 | CD28 molecule | CD28 |

| CS000003093 | Cadherin 13 | CDH13 |

| CS000014745 | Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 3 | celsr3 |

| CS000006114 | chordin like 1 | CHRDL1 |

| CS000008605 | Contactin associated protein 1 | CNTNAP1 |

| CS000002886 | Collagen type XV alpha 1 chain | COL15A1 |

| CS000004853 | Collagen type III alpha 1 chain | COL3A1 |

| CS000025399 | Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain | COL4A6 |

| CS000009979 | Cysteine rich transmembrane BMP regulator 1 | CRIM1 |

| CS000011960 | Crystallin alpha B | CRYAB |

| CS000002632 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 3 | CSRP3 |

| CS000007341 | Catenin delta 1 | CTNND1 |

| CS000003128 | Cytochrome b-245 alpha chain | CYBA |

| CS000005867 | Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 | EPS8 |

| CS000008545 | Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 | ERBB2 |

| CS000012011 | Coagulation factor III, tissue factor | F3 |

| CS000002168 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 | FGFR3 |

| CS000003405 | Fibronectin 1 | FN1 |

| CS000002902 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor subunit 1 | GABBR1 |

| CS000008168 | Glucagon | GCG |

| CS000005687 | G protein subunit alpha 12 | GNA12 |

| CS000013318 | G protein subunit gamma 10 | GNG10 |

| CS000001877 | Glycoprotein nmb | GPNMB |

| CS000017383 | G protein-coupled receptor 62 | GPR62 |

| CS000008476 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 10 | GRB10 |

| CS000008544 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 7 | GRB7 |

| CS000006655 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 | GRK3 |

| CS000020555 | Granzyme H | GZMH |

| CS000023516 | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit | HIF1A |

| CS000007378 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 | HSPB1 |

| CS000000714 | Interleukin 22 | IL22 |

| CS000008411 | Integrin subunit alpha 11 | ITGA11 |

| CS000005400 | Inositol-trisphosphate 3-kinase A | ITPKA |

| CS000009858 | Arginine demethylase and lysine hydroxylase | JMJD6 |

| CS000020495 | Kinase non-catalytic C-lobe domain containing 1 | KNDC1 |

| CS000009567 | Keratin 18 | KRT18 |

| CS000019220 | Keratin 8 | KRT8 |

| CS000015494 | Limb development membrane protein 1 | LMBR1 |

| CS000008774 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5 | MAP3K5 |

| CS000003679 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 | MAPK9 |

| CS000001243 | Myelin basic protein | MBP |

| CS000023152 | Mindbomb E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | MIB1 |

| CS000017005 | Muskelin 1 | MKLN1 |

| CS000014226 | MOB kinase activator 1B | MOB1B |

| CS000012971 | Neuron derived neurotrophic factor | NDNF |

| CS000008885 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally down-regulated 9 | NEDD9 |

| CS000001770 | Neuroepithelial cell transforming 1 | NET1 |

| CS000000790 | NFKB inhibitor like 1 | NFKBIL1 |

| CS000018597 | Neurexin 2 | NRXN2 |

| CS000014447 | PDZ-binding kinase | PBK |

| CS000003989 | Pleckstrin homology domain interacting protein | PHIP |

| CS000000947 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 3 | PHLDA3 |

| CS000010015 | Proteolipid protein 1 | PLP1 |

| CS000000163 | DNA polymerase kappa | POLK |

| CS000025418 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A | PPIA |

| CS000008337 | Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent 1L | PPM1L |

| CS000000189 | Protein kinase AMP-activated non-catalytic subunit beta 2 | PRKAB2 |

| CS000019311 | Protein kinase C alpha | PRKCA |

| CS000012528 | Persephin | PSPN |

| CS000009267 | RAB32, member RAS oncogene family | RAB32 |

| CS000004444 | RAB33A, member RAS oncogene family | RAB33A |

| CS000007756 | Raf-1 proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase | RAF1 |

| CS000001871 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 5 | RAPGEF5 |

| CS000015645 | Regulator of cell cycle | RGCC |

| CS000020112 | Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator-like 2 | RGL2 |

| CS000023359 | Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator like 3 | RGL3 |

| CS000008982 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 5 | RGS5 |

| CS000009817 | Rho related BTB domain containing 2 | RHOBTB2 |

| CS000011866 | Ras homolog family member C | RHOC |

| CS000000565 | Ras and Rab interactor-like protein | RINL |

| CS000012325 | Receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 | RIPK2 |

| CS000012890 | Sestrin 3 | SESN3 |

| CS000021605 | Secreted frizzled related protein 4 | SFRP4 |

| CS000018595 | Signal-induced proliferation-associated 1 | SIPA1 |

| CS000005505 | SIVA1 apoptosis inducing factor | SIVA1 |

| CS000012858 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 | SOCS2 |

| CS000023280 | Sorbin and SH3 domain containing 2 | SORBS2 |

| CS000006802 | Sortilin related VPS10 domain containing receptor 1 | SORCS1 |

| CS000020596 | Sortilin related VPS10 domain containing receptor 2 | SORCS2 |

| CS000011090 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 |

| CS000021122 | Sprouty related EVH1 domain containing 2 | SPRED2 |

| CS000003610 | Serine/threonine kinase 32A | STK32A |

| CS000024894 | Serine/threonine kinase 38 like | STK38L |

| CS000024997 | Toll like receptor 6 | TLR6 |

| CS000015148 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 10 | TNFSF10 |

| CS000011024 | Target of myb1 like 1 membrane trafficking protein | TOM1L1 |

| CS000019856 | TNF receptor associated factor 2 | TRAF2 |

| CS000012224 | TNF receptor associated factor 3 | TRAF3 |

| CS000018042 | Tribbles pseudokinase 1 | TRIB1 |

| CS000002912 | Tripartite motif containing 21 | TRIM21 |

| CS000005987 | Tyrosine kinase 2 | TYK2 |

| CS000020993 | TYRO3 protein tyrosine kinase | TYRO3 |

| CS000017504 | unc-5 netrin receptor A | UNC5A |

| CS000002566 | VAMP associated protein B and C | VAPB |

| CS000025210 | Wnt family member 11 | WNT11 |

| CS000014907 | Zinc finger protein 219 | ZNF219 |

| CS000002650 | Doublecortin domain containing 1 | |

| CS000013923 | Uncharacterized | |

| CS000014046 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5-like | |

| CS000019987 | Plexin A3 | |

| CS000025011 | Retinoic acid receptor, alpha | |

Gene names and gene symbols are listed for each enriched GO term. Genes in the biological adhesion and cell adhesion lists were identical, because these are parent and child terms. GO terms were considered significant when FDR corrected p ≤ 0.05

Table 6.

GO Cellular Component terms and genes that were enriched among differentially expressed genes in ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles

| locus_number (in snapping turtle) | gene_name | gene_symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen trimer | ||

| CS000004853 | Collagen type III alpha 1 chain | COL3A1 |

| CS000025399 | Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain | COL4A6 |

| CS000009656 | Collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain | COL8A1 |

| CS000002886 | Collagen type XV alpha 1 chain | COL15A1 |

| CS000014058 | Collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | COL18A1 |

| CS000002530 | Collagen type XX alpha 1 chain | COL20A1 |

| CS000018990 | Collagen type XXII alpha 1 chain | COL22A1 |

| CS000007237 | Collectin subfamily member 10 | COLEC10 |

| CS000014966 | Ficolin 3 | FCN3 |

| z-disc | ||

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000011960 | Crystallin alpha B | CRYAB |

| CS000018274 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 1 | CSRP1 |

| CS000002632 | Cysteine and glycine rich protein 3 | CSRP3 |

| CS000023885 | Formin homology 2 domain containing 3 | FHOD3 |

| CS000007378 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 | HSPB1 |

| CS000019220 | Keratin 8 | KRT8 |

| CS000005252 | Myomesin 3 | MYOM3 |

| CS000000499 | Myopalladin | MYPN |

| CS000015509 | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 | SCN5A |

| CS000023280 | Sorbin and SH3 domain containing 2 | SORBS2 |

| Extracellular space | ||

| CS000008845 | Apolipoprotein F | APOF |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000004917 | Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 | BMPR2 |

| CS000004554 | Complement C1r | C1R |

| CS000021043 | Complement C1s | C1S |

| CS000023075 | CD109 molecule | CD109 |

| CS000003093 | Cadherin 13 | CDH13 |

| CS000003059 | Carboxylesterase 2 | CES2 |

| CS000010784 | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein | CETP |

| CS000014980 | Complement factor B | CFB |

| CS000008574 | 2′,3′-Cyclic nucleotide 3′ phosphodiesterase | CNP |

| CS000002886 | Collagen type XV alpha 1 chain | COL15A1 |

| CS000014058 | Collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | COL18A1 |

| CS000002530 | Collagen type XX alpha 1 chain | COL20A1 |

| CS000018990 | Collagen type XXII alpha 1 chain | COL22A1 |

| CS000004853 | Collagen type III alpha 1 chain | COL3A1 |

| CS000025399 | Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain | COL4A6 |

| CS000009656 | Collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain | COL8A1 |

| CS000007237 | Collectin subfamily member 10 | COLEC10 |

| CS000005701 | Extracellular leucine rich repeat and fibronectin type III domain containing 1 | ELFN1 |

| CS000012011 | Coagulation factor III, tissue factor | F3 |

| CS000003405 | Fibronectin 1 | FN1 |

| CS000008168 | Glucagon | GCG |

| CS000018642 | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 | HABP2 |

| CS000007378 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 1 | HSPB1 |

| CS000000714 | Interleukin 22 | IL22 |

| CS000005377 | Galectin 1 | LGALS1 |

| CS000024186 | Leucine rich repeat containing 3B | LRRC3B |

| CS000000330 | Matrix metallopeptidase 25 | MMP25 |

| CS000001051 | Monooxygenase DBH like 1 | MOXD1 |

| CS000025418 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A | PPIA |

| CS000007586 | Proline and arginine rich end leucine rich repeat protein | PRELP |

| CS000012528 | Persephin | PSPN |

| CS000006963 | Secretogranin II | SCG2 |

| CS000024555 | Stimulator of chondrogenesis 1 | SCRG1 |

| CS000021605 | Secreted frizzled related protein 4 | SFRP4 |

| CS000008622 | Sclerostin | sost |

| CS000011090 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 |

| CS000002388 | Suppression of tumorigenicity 14 | ST14 |

| CS000025210 | Wnt family member 11 | WNT11 |

| CS000012404 | Uncharacterized | |

| CS000021864 | PZP, alpha-2-macroglobulin like | |

| Extracellular region | ||

| CS000014235 | Anthrax toxin receptor 2 | ANTXR2 |

| CS000003440 | Apolipoprotein C1 | apoc1 |

| CS000021833 | Rho GTPase activating protein 45 | ARHGAP45 |

| CS000009788 | Bone morphogenetic protein 10 | BMP10 |

| CS000004554 | Complement C1r | C1R |

| CS000021043 | Complement C1s | C1S |

| CS000010941 | Coiled-coil domain containing 40 | CCDC40 |

| CS000023075 | CD109 molecule | CD109 |

| CS000003093 | Cadherin 13 | CDH13 |

| CS000010784 | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein | CETP |

| CS000014980 | Complement factor B | CFB |

| CS000006114 | Chordin like 1 | CHRDL1 |

| CS000002886 | Collagen type XV alpha 1 chain | COL15A1 |

| CS000014058 | Collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | COL18A1 |

| CS000002530 | Collagen type XX alpha 1 chain | COL20A1 |

| CS000018990 | Collagen type XXII alpha 1 chain | COL22A1 |

| CS000004853 | Collagen type III alpha 1 chain | COL3A1 |

| CS000025399 | Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain | COL4A6 |

| CS000009656 | Collagen type VIII alpha 1 chain | COL8A1 |

| CS000007237 | Collectin subfamily member 10 | COLEC10 |

| CS000009979 | Cysteine rich transmembrane BMP regulator 1 | CRIM1 |

| CS000011191 | Deoxyribonuclease 1 like 3 | DNASE1L3 |

| CS000021606 | Ependymin related 1 | EPDR1 |

| CS000013674 | Eva-1 homolog C | EVA1C |

| CS000014966 | Ficolin 3 | FCN3 |

| CS000002168 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 | FGFR3 |

| CS000003405 | Fibronectin 1 | FN1 |

| CS000002902 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor subunit 1 | GABBR1 |

| CS000008168 | Glucagon | GCG |

| CS000009498 | Glypican 3 | GPC3 |

| CS000018642 | Hyaluronan-binding protein 2 | HABP2 |

| CS000000714 | Interleukin 22 | IL22 |

| CS000012953 | Immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine-rich repeat | ISLR |

| CS000005377 | Galectin 1 | LGALS1 |

| CS000012971 | Neuron derived neurotrophic factor | NDNF |

| CS000021269 | Neural EGFL like 1 | NELL1 |

| CS000012602 | Neuritin 1 | NRN1 |

| CS000002394 | Neurotrimin | NTM |

| CS000025418 | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A | PPIA |

| CS000007586 | Proline and arginine rich end leucine rich repeat protein | PRELP |

| CS000012962 | Protease, serine 12 | PRSS12 |

| CS000012528 | Persephin | PSPN |

| CS000013172 | Sperm flagellar 2 | SPEF2 |

| CS000011090 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 |

| CS000019009 | Thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 7A | THSD7A |

| CS000015148 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 10 | TNFSF10 |

| CS000011540 | von Willebrand factor A domain containing 3A | VWA3A |

| CS000013624 | von Willebrand factor A domain containing 5B1 | VWA5B1 |

| CS000025210 | Wnt family member 11 | WNT11 |

| CS000012404 | Uncharacterized | |

Gene names and gene symbols are listed for each enriched GO term. GO terms were considered significant when FDR corrected p ≤ 0.05

We selected genes for qPCR validation from the GO categories described above based on their established role in influencing cardiac function and anoxia tolerance, including genes associated with heart defects in humans or other species, genes involved in calcium signaling or mitochondrial function, and/or genes that regulate expression of other genes. Overall, differential expression was confirmed for 14 of 16 genes examined (Table 7; Fig. 3B–Q). Some genes, such as DDIT4L and WNT11, were expressed at consistently lower levels in the H10 group compared to the N21 group at both ages (Fig. 3B, C). Other genes, such as ITGA11, MIPEP, MNAT1, PPIA, TNNT2, and TPM3, were reliably higher in the H10 group compared to the N21 group (Figs. 3D–I). Several genes displayed treatment by age interactions. For COL8A1, NCOA2, and SCN5A there was no difference at 7 months of age, but expression was higher in the H10 group than the N21 group at 9 months of age (Fig. 3J–L). For HIF1A and PFKFB1, there was no difference at 7 months of age, but expression was lower in the H10 group than the N21 group at 9 months of age (Fig. 3M, N). Another pattern was observed for HTRA3, which differed between treatment groups at 7 months of age, but not at 9 months of age (Fig. 3O). In contrast, CALR and SNTB1 did not differ between N21 and H10 groups at either age (Fig. 3P, Q).

Table 7.

Results from a two-way ANCOVA for mRNA expression in ventricles from juvenile snapping turtles

| Gene | Oxygen treatment | Age | Oxygen treatment × age | Covariate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALR | F1,20 = 0.27, p = 0.61 | F1,20 = 4.5, p = 0.05 | F1,20 = 0.18, p = 0.68 | F1,20 = 0.71, p = 0.41 |

| COL8A1 | F1,20 = 6.9, p = 0.02 | F1,20 = 15.5, p = 0.0008 | F1,20 = 3.6, p = 0.07 | F1,20 = 8.3, p = 0.009 |

| DDIT4L | F1,20 = 9.3, p = 0.006 | F1,20 = 0.21, p = 0.65 | F1,20 = 0.20, p = 0.66 | F1,20 = 14.4, p = 0.001 |

| HIF1A | F1,20 = 3.85, p = 0.06 | F1,20 = 0.04, p = 0.85 | F1,20 = 6.0, p = 0.02 | F1,20 = 0.96, p = 0.34 |

| HTRA3 | F1,19 = 5.2, p = 0.03 | F1,19 = 3.9, p = 0.06 | F1,19 = 6.2, p = 0.02 | F1,19 = 6.0, p = 0.02 |

| ITGA11 | F1,20 = 5.4, p = 0.03 | F1,20 = 4.4, p = 0.05 | F1,20 = 0.66, p = 0.43 | F1,20 = 0.95, p = 0.34 |

| MIPEP | F1,20 = 8.2, p = 0.01 | F1,20 = 0.14, p = 0.71 | F1,20 = 0.04, p = 0.85 | F1,20 = 8.9, p = 0.007 |

| MNAT1 | F1,20 = 9.2, p = 0.006 | F1,20 = 3.1, p = 0.09 | F1,20 = 0.48, p = 0.5 | F1,20 = 0.08, p = 0.78 |

| NCOA2 | F1,20 = 5.9, p = 0.02 | F1,20 = 5.1, p = 0.03 | F1,20 = 2.26, p = 0.15 | F1,20 = 7.9, p = 0.01 |