Abstract

Italy was the first European country to be affected by the Covid‐19. To limit the contagion, an emergency protocol was triggered on March 10, 2020, which imposed a lockdown for 69 days. Many Italians considered the restrictions imposed by the government excessive and unnecessary. We hypothesized that agreement with government restrictions and compliance with imposed rules was positively correlated with trust in institutions, civic engagement, and the sense of community. To this end, during the lockdown period, we administered an online questionnaire to 189 Sicilians. The results showed that trust in institutional organizations and the attitude component of civic engagement facilitate the approval of limitations imposed during the lockdown period and the acceptance of future restrictions. Unexpectedly, the behavioral component of civic engagement leads to the rejection of restrictions and behaviors that could contain a further spread of the virus. Indeed, participants who declared that they were engaged in beneficial actions for their community disapproved of the measures already adopted and were unwilling to adopt future behaviors to limit the spread of the virus.

Keywords: civic engagement, sense of community, social capital, trust in institutions

1. INTRODUCTION

On 12 February 2020, the first case of Covid‐19 was officially diagnosed in Italy, and only one day later, an older man died of the virus. In a few days, the number of infections increased, and Italy became the first Western country to manage the Covid‐19 pandemic. The government decided on an emergency protocol that, from 10 March to 18 May, imposed restrictions on free movement and the closure of almost all production activities. During the Covid‐19 emergency Italians' confidence in the government and the health system grew (Scavo, 2020). Altruistic behaviors have also increased; indeed, donations to the health system increased by about 30% compared to previous years: more than 10 million Italians declared they had given money at the beginning of the pandemic emergency and many others declared their intention to do it soon (Castiglioni & Lozza, 2020).

During the lockdown period, most citizens observed the rules and expressed solidarity behaviors; however, some behavior aimed to challenge the rules decided by the authorities to protect public health emerged. On social networks, more and more skeptics expressed distrust of government decisions and contested the warnings of experts and the information disseminated by the mass media about the severity of the virus and the number of deaths. One study found that people who are less careful about protecting their health tend to have less trust in health institutions and scientists' prescriptions and are consequently less willing to work together to achieve a common public health goal (Graffigna et al., 2020).

The lack of civic sense of citizens who contested and violated the lockdown rules disappointed the majority of Italians (Ipsos, 2020), who, however, over the months have become more pessimistic about the financial consequences of the blocking measures, so much so that concerns about current and future economic conditions have become stronger than health concerns (Graffigna et al., 2021).

The conflicting behaviors and opinions of Italians led us to wonder if attitudes towards the lockdown rules could be correlated with the sense of community, institutional trust, and civic commitment.

The current scenario considers trust, civic commitment, and community care as tools for dealing with the emergency. Therefore, this study aimed to verify whether thesense of community, trust in institutions, and civic engagement could influence the acceptance and compliance with the restrictions already approved by the government and with other limitations that may be necessary for the future to counter the Covid‐19 pandemic.

1.1. Civic engagement and sense of community

The social dimensions involved in the emergency caused by Covid‐19 constitute the central elements of the concept of social capital. Indeed, it has been defined as a cultural phenomenon that expresses the civic duty, cohesion, and mutual trust that help a community overcome problems through collective action (Putnam, 1993). Banfield (1958) and Putnam (1993) highlighted a low social capital in the southern regions, underlining the existence of a relationship between institutional performance, cultural, economic, and political variables. After many decades, the society and economy of the South of Italy and Sicily have changed a lot, but the gap with the northern regions is still very strong. Many authors agree that the southern ruling classes are the main responsibility of this condition (Cartocci & Vanelli, 2015) which limits the development of social capital and socio‐economic well‐being of Sicilians.

Social capital, therefore, is based on trust (Fukuyama, 1995; Raiser, 1999) and individual investment in social networks (Bourdieu, 1993; Durlauf & Fafchamps, 2005). It is regulated by reciprocity norms (Coleman, 1988) and is complementary to formal institutions; indeed, it contributes to strengthening democracy and increasing the social and economic well‐being of the community (Wallace et al., 2002). Social capital, therefore, is born and developed by investing in social relations and civic engagement (Hyman, 2002; Lin, 2001).

Civic engagement consists of individual and collective actions aimed at improving the conditions of one's community (Ehrlich, 1997). It is expressed in many ways: by giving charity, engaging in volunteering, participating and supporting democratic and political movements, and so on (Adler & Goggin, 2005; DelliCarpini et al., 2004). Therefore, it manifests itself in behaviors that refer to the sense of community (Jacoby et al., 2009), social participation (Lasker & Weiss, 2003), and active citizenship (Hoskins & Mascherini, 2009). More specifically, civic engagement is a multidimensional concept (Campagna et al., 2020) which includes: political commitment (activities in support of representative democracy; Ekman & Amnå, 2012); civil engagement (protests, strikes, participation in human rights organizations, environmentalists, and so on; Brady, 1999); community commitment (volunteering; Okun & Michel, 2006) and civic commitment (respect for the environment and animals, critical consumption choices; Gundelach, 2020).

The construct of civic engagement can be divided into two components: civic attitudes, that is, values, ideas, and feelings that people have about their involvement in their community, and civic behaviors, that is, the concrete actions and responsibilities that individuals take to improve their community (Doolittle & Faul, 2013).

The bond and interest in one's community are expressed through the sense of community, which defines the feelings of belonging and trust and the perception of similarity and interdependence between people belonging to the same community (McMillan & Chavis, 1986; Sarason, 1974;). Studies conducted in Italy reveal that the sense of community contrasts feelings of loneliness (Prezza et al., 1999), promotes social well‐being (Cicognani et al., 2008), and the perception of a better quality of life (Di Marco et al., 2020). Furthermore, belonging to a community positively correlates with civic participation (Talò et al., 2014) and with socio‐political empowerment (Francescato et al., 2007). Adolescents who are involved in their community perceive less urban insecurity (Prezza & Pacilli, 2007), show greater civic involvement (Albanesi et al., 2007), and more feelings of empowerment (Cicognani et al., 2015). The sense of community has been considered a cognitive component of civic engagement (Underwood, 2017).

In this work, we considered the sense of community concerning geographical belonging, the local community, and the interactions that members develop with it (Heller, 1989). The community can also be understood as a relational phenomenon. Belonging to a community means sharing a history, language, religion, and so on (Gusfield, 1975). In any case, the sense of community defines a system of voluntarily maintained relationships and interdependence, making it possible to express the needs for intimacy and belonging in a climate of shared trust (Sarason, 1974).

1.2. Institutional trust

Regarding trust, a distinction must be made between social trust and institutional trust. Social trust, also called generalized trust, pertains to an optimistic view of the world and promotes social interactions between strangers based on the expectation that they are sincere and do not want to harm others (Nannestad, 2008). Institutional trust, on the other hand, is characterized by impersonality and expectation that rulers, police, and public apparatuses in general, act at their best and for the good of the community (Levi & Stoker, 2000). In social capital studies, the more established theoretical perspective states that civic engagement promotes both social (Paxton, 2007) and institutional trust (Sivesind et al., 2013). However, several studies show that social trust often leads to civic participation and engagement (Bekkers, 2012; Dinesen, 2012); therefore, people who nourish a certain level of social trust would be the most willing to help the community with their voluntary work.

With regard to trust in institutions, it should be noted that it is declining throughout the Western world (Ortiz‐Ospina & Roser, 2016; Rasmussen Global, 2018). As has been pointed out, trust is a fragile and precious goods (Dasgupta, 1988) that requires a response mechanism to trust that generates and sustains trust itself (Pettit, 1995), so that if the citizen's expectations are disregarded, it tends to weaken (Möllering, 2006).

The importance of reliable institutions for development, cooperation, and social cohesion is widely recognized (Kumagai & Iorio, 2020; Sztompka, 1999) because if the institutional apparatus is reliable, citizens more easily comply with its demands (Fukuyama, 1995). However, so that institutional trust can exist, it is important that institutional representatives are credible, that they know how to design effective interventions and act in a non‐arbitrary way (Levi & Stoker, 2000). In general, it seems that reliability has five components: competence, integrity, performance, accuracy, and relevance of the information provided (Kavanagh et al., 2020). These five characteristics are more or less a priority depending on the institutions considered; so, for example, perceived competence and integrity are more important to rulers, while the accuracy and relevance of the information provided are critical for trusting the media. Furthermore, it has been found that scandals involving a politician can negatively affect the trust that voters have in the entire government and the political system (Bowler & Karp, 2004). Even too strict laws and rules, that have not been properly negotiated with public opinion, can damage trust in the political class because citizens perceive government actions as intrusive and oppressive (Pettit, 1995).

The current scenario, therefore, is characterized by the decline of institutional trust by citizens, even if, at the same time, the objective indicators show that services have improved in recent decades. What has been called the “delivery paradox” (Coats & Passmore, 2008), makes it clear that to maintain citizens' trust in institutions it is not enough to improve public services (Van de Walle & Bouckaert, 2007), but institutions must strive to build a model of trust inspired by social coordination that works to ensure responsible citizen collaboration and not mere compliance (Brown, 2020). This new model of interdependent trust assumes that the citizen is recognized as an active partner in the relationship and that he or she feels respected and recognized as a competent subject (Brown, 2020). After all, it should be noted that the average citizen is less and less similar to the “traditional” citizen who passively relied on experts and authorities (Hanlon et al., 2006). For example, as regards the management of his own health, he is increasingly informed and competent, and therefore, he is also more suspicious and less willing to accept the opinion of an expert without having compared it with other opinions and also having verified it through the means that technology makes available (Hanlon et al., 2006).

The relationship between institutional trust and emergency appears complex. Crises and their impact on quality of life reduce citizens' institutional trust (Miller & Listhaug, 1999; Polavieja, 2013). Consequently, people ignore government‐imposed rules and social norms if they consider politicians' decisions inadequate (Roth et al., 2011; Torcal, 2014). Furthermore, concerning the relationship between institutional trust and civic engagement, it emerged that as trust in parliament increases, participation in volunteering decreases (Hackl et al., 2009), and that the choice to engage in volunteering can be favored by mistrust in institutions that have not been able to solve specific community problems (Eliasoph, 1998).

The delicate balance between institutional trust, politicians' credibility, and crises enhances the probability that many citizens are critical regarding institutions' behavior. In Italy, as in other countries, there is a constant decline in trust in institutions (OECD, 2017). A survey conducted in 2019 (before the pandemic) showed that trust in institutions has dwarfed public and political organizations, except the Pope (Demos, 2019); moreover, a specific study on political institutions shows that Italians have little faith in parties, parliament, and the government (Bergman et al., 2021). After all, since the 1990s the country has been the scene of great political scandals (Pardo, 2004) and numerous cases of corruption which, by violating the democratic contract, have partly compromised citizens' trust in the political system (Memoli, 2011; Pardo, 2018). In addition to these serious episodes, citizens have been disappointed by many unfulfilled promises of reforms (Bertsou, 2019) and by the credibility of an important part of national journalism which, in recent years, appears not very independent from political power (Calabresi, 2015). To prevent corruption, facilitate citizens' participation in public decisions, and consolidate the legitimacy of the authorities, legislative measures have been enacted to achieve administrative transparency (Holzner & Holzner, 2006). Overall, the results are positive (Galli et al., 2017), even if the process is partly held back by bureaucracy (Di Mascio et al., 2019), regulatory incompleteness (Nugnes, 2019), and some resistance. A recent study, for example, conducted within the national health system, finds that only a minority of the involved bodies have disclosed social reporting reports useful for understanding their contribution to SDG3 (Sustainable Development Goals 3, United Nation, 2015) in a transparent way and that public managers are less likely to adopt non‐financial reporting tools than private ones (Pizzi et al., 2020). Non‐financial reporting is a strategic document that goes beyond the communication of economic results and allows citizens to understand if the activities of companies and institutions are oriented towards social and environmental responsibility (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019). It is therefore an excellent tool for dialoguing and building trust between institutions and citizens (La Torre et al., 2020).

The decline of trust in institutions, the severe restrictions imposed by the government and those announced for the future, the damage suffered by the national economy, and the high number of deaths registered in Italy despite the lockdown could lead to a severe worsening of institutional distrust. This distrust could push citizens not to follow the rules imposed by the institutions to counter the spread of the virus (for example, using a Smartphone application to monitor infections, massive vaccinations).

2. HYPOTHESES

Considering the theoretical framework outlined from the literature presented in the introduction, our study aimed to investigate how the sense of community, civic engagement, and trust in institutions correlated with the attitudes towards anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government and those the people would adopt.

In particular, we assumed that:

H1: the sense of community, civic engagement, and trust in institutions should positively correlate with the attitudes towards anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government.

H2: the sense of community, civic engagement, and trust in institutions should positively correlate with the attitudes towards anti‐Covid measures that people would adopt.

3. METHOD

3.1. Participants and procedure

Participants were 189 Sicilians (146 female and 43 male), aged between 18 and 75 years (Mean = 42.52, S.D. = 13.56), recruited through an online questionnaire administered during the Coronavirus lockdown. Participants had the following educational level: 9.5% middle school, 31.7% high school diploma, 48.1%degree, and 10.6% doctorate/specialization.

All participants were asked to indicate the level (none, indirect – i.e., support with small donations or by disseminating initiatives on social networks – and active – i.e., regular participation in activities) of involvement in 13 types of associations proposed (e.g., social, religious, and political): 67.2% of the sample shows no involvement; 25.9% indirect involvement, and 6.9% active involvement.

All participants were informed that their responses would remain private.

4. MEASURES

4.1. Sense of community

To measure sense of community 12 items derived from the Sense of Community Scale (Prezza et al., 1999) were used (see also, Di Marco et al., 2020). The items reflect three factors: attachment (3 items, e.g., “I feel I belong to this community”), social relations (6 items, e.g., “People in this community are kind and courteous”), and satisfaction of needs and influence (3 items, e.g., “This community offers me the opportunity to do many things”). Participants were asked to express their opinion on a 4‐point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The reliability was satisfactory for all factors (alphas for attachment, satisfaction of needs and influence, and social relations were respectively 0.821, 0.725, and 0.650.

4.2. Civic engagement

To assess civic engagement, the Civic Engagement Scale (Doolittle & Faul, 2013) was used. The items reflect two factors: civic attitudes (8 items, e.g., “I feel responsible for my community”) and civic behaviors (6 items, e.g., “I am permanently involved in volunteering for the community”). Participants were asked to express their opinion on a 7‐point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).The reliability of civic attitudes and civic behaviors was respectively 0.867 and 0.890.

4.3. Trust in institutions

Participants were asked to what extent they trust 10 public institutions or organizations (e.g., “Health system,” “National political system”; see World Value Survey, 2006). Participants were asked to express their opinion about public institutions on a 5‐point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (entirely). Alpha was 0.785.

4.4. Anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government

Participants were asked their opinion about eight anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government (e.g., “Wearing a mask in public places,” “Ban on going out for personal reasons”). Participants were asked to express their opinion on a 4‐point scale ranging from 1 (unnecessary and harmful to the economy) to 4 (useful and necessary).Reliability was 0.813.

4.5. Anti‐Covid measures people would adopt

Participants were asked about their availability to adopt nine personal behaviors to limit the spread of the virus after the lockdown (e.g., “Using Smartphone applications to monitor the spread of the virus,” “Limiting personal travel unless strictly necessary”). For each behavior, participants expressed their opinion on a 4‐point scale ranging from 1 (never, I am against in principle) to 4 (Yes, because I think it is useful). Reliability was 0.773.

5. RESULTS

Table 1 showed means, standard deviations, and correlations between measures. Results indicate that trust in institutions was modest (M = 2.44; S.D. = 0.51) and participants consider the anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government to be adequate and appropriate (M = 3.58; S.D. = 0.42); moreover, they show a favorable disposition towards further limitations aimed at countering the spread of the virus (anti‐Covid measures people would adopt, M = 3.61; S.D. = 0.39). The sense of community shows medium‐low scores, highlighting a certain consistency of social relationships (M = 2.80; S.D. = 0.55), a moderate level of attachment (M = 2.63: S.D. = 0.68), and a modest satisfaction of needs and influence (M = 2.41; S.D. = 0.64). The civic sense of the participants appears well structured regarding attitudes (M = 5.36: S.D. = 0.99) and slightly lacking regarding behavior (M = 4.26; S.D. = 1.43).

TABLE 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between measures

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government | 3.58 | 0.42 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 | Anti‐Covidmeasures people would adopt | 3.61 | 0.39 | 0.64*** | 1 | ||||||

| 3 | Sense of community: Attachment | 2.63 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1 | |||||

| 4 | Sense of community: Satisfaction of needs and influence | 2.41 | 0.64 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.64*** | 1 | ||||

| 5 | Sense of community: Social relations | 2.80 | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.72*** | 0.60*** | 1 | |||

| 6 | Civic engagement: Civic Attitudes | 5.36 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.18* | 0.29*** | 0.24** | 0.27*** | 1 | ||

| 7 | Civic engagement: Civic Behaviors | 4.26 | 1.43 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.25*** | 0.09 | 0.22** | 0.62*** | 1 | |

| 8 | Trust in institutions | 2.44 | 0.51 | 0.22** | 0.23** | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15* | 0.22** | 0.11 | 1 |

Note: *p < 0.05; ** < p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Regarding correlation, anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government positively correlate with anti‐Covid measures people would adopt. Anti‐Covid measures people would adopt positively correlate with trust in institutions and with civic attitudes, while anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government only positively correlate with trust in institutions. No correlation was found between both anti‐Covid measures and civic behavior and sense of community. The three dimensions of sense of community (attachment, social relations, and satisfaction of needs and influence) are positively correlated with civic attitudes, while civic behaviors are only positively correlated with attachment and social relations. Finally, trust in institutions is positively correlated with all the variables investigated, except for civic behavior, attachment, and satisfaction of needs and influence.

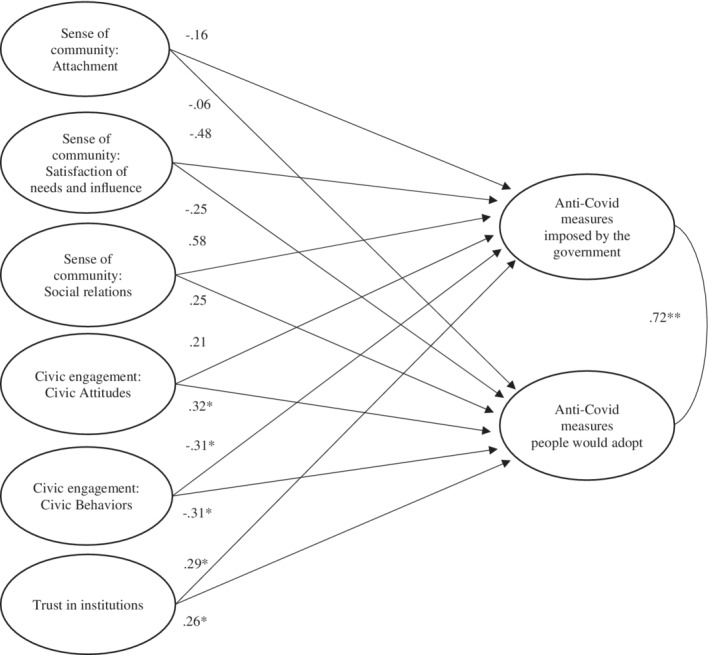

To test the effects of sense of community, civic engagement, and trust in institutions on attitude towards anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government and anti‐Covid measures people would adopt, we ran a multiple regression with latent variables (LISREL 8; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996‐2001). To test the model, two aggregated indicators were obtained for each variable by randomly splitting the respective items (partial disaggregation model, Bagozzi & Heatherton, 1994). The testing of the model is reported in Figure 1. The model has a good general fit: χ 2 (76) = 109.72, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.041; although χ 2 was significant, CFI and SRMR satisfied the respective criterion (see Hu & Bentler, 1999). Figure 1 shows that trust in institutions is associated with a positive assessment of government‐imposed restrictions and those that may be adopted in the future, while civic behaviors are negatively associated with them. Whereas, civic attitudes are positively associated with both anti‐Covid measures. The sense of community (attachment, satisfaction of needs and influence, and social relations) does not affect both kind anti‐Covid measures.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of investigated construct on anti‐covid measure. Note: *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001

6. DISCUSSION

In this study, we tested the effects of sense of community, civic engagement, and trust in institutions on attitudes towards anti‐Covid measures imposed by the government and those people would adopt. Data collected show low levels of social capital; indeed, only a few participants are actively involved in associations, trust in institutions is low, sense of community is modest, and civic behaviors are not widespread. The poverty of social capital in Sicily, as well as in other regions of southern Italy, is not surprising (Putnam, 1993). Among the causes of this developed scarcity are inequalities and conflicts that have historically plagued Southern Italy (Albanese & de Blasio, 2018; Boix & Posner, 1996; Mouritsen, 2003). The lack of share capital is, consequently, also related to the economic backwardness which, at present, does not tend to improve (Azevedo, 2015). There is a condition of recession in the Southern Italy that keeps the gap between the southern and northern regions of Italy high (Svimez, 2019). In Sicily, per capita income is among the lowest in the country and the incidence of poor family is almost double the national average (Istat, 2019). The causes of the irregular development of the South and of the regional disparities that persist after 150 years of common national history are complex and involve historical, cultural, geographical, and structural factors (Alfani & Sardone, 2015; Consoli & Spagano, 2008; Fazio, 2003). According to many observers, however, the role of institutions has been decisive, having behaved over time as extractive institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012) and having acted to keep the economy and society of the South in a condition of “passive modernization” (Felice & Vasta, 2015). Formal institutions shape economic growth and development (Aoki, 2001; Rodrik et al., 2004), but also the quality of informal institutions, quality of life, and social trust (European Commission, 2017). The bad management of the southern regions by the institutions has contributed to lowering the well‐being of these regions (Ferrara & Nisticò, 2019).The South, even today, has an insecure socio‐economic climate, lacks infrastructure, and is less rich than the North (Nifo & Vecchione, 2015).

In this context, it is easier to find a culture that produces little social capital, little collaboration, and a lot of social distrust (Bigoni et al., 2016).

According to the model we tested, trust in institutions predicts acceptance of government‐imposed anti‐covid measures and the intention to adopt others in the future if necessary. Civic attitudes, on the other hand, positively influence the intention to adopt cautions in the future, but not those already imposed by the government. Probably, this result is connected with the different severity of the measures: the current ones, imposed during the health crisis, are rejected because they have excessively limited personal freedom; future ones, on the other hand, are accepted because they have lighter restrictions that would allow people to go out, go to work, and so on.

The hypotheses that guided this work are confirmed with regards to trust in institutions: it, indeed, is associated with compliance with the provisions set by the government and with the adoption of those that may be necessary for the future. On the other hand, the sense of community does not affect attitudes in favor of restrictions, while civic behaviors are associated with the rejection of current and future measures.

7. CONCLUSION

The results showed that trust in institutions predicts acceptance of government‐imposed anti‐covid measures and the intention of adopting others in the future if necessary. Results concerning civic behaviors are in disagreement with the literature because people who act for the well‐being of their community should not reject the provisions designed to protect the health of the community. This result could express impatience with the solutions proposed by the government because they are generalized and do not consider the territorial needs of specific cities. Indeed, in the first wave of the pandemic, most of the infections and deaths due to the Coronavirus were recorded in Northern Italy, while in the South of Italy and Sicily the virus affected much less (ISTAT, 2020). For this reason, the measures imposed are judged inadequate.

More generally, it can be deduced that civic engagement (voluntary and free response to the needs of the community) fosters feelings of distrust towards institutions. They were unable to meet the needs of the community. This hypothesis contrasts with the more consolidated theoretical perspective affirming that participation in voluntary organizations promotes social trust (Jennings & Stoker, 2004) and, thanks to collaborative contacts with institutional representatives (Bjørnskov, 2009), institutional trust (Brehm & Rahn, 1997). However, it does not contradict studies showing that social trust often drives people to engage in volunteering and charitable organizations (van Ingen & Bekkers, 2013). Consequently, civic behaviors persist even when there is a lack of trust in institutions and their quality is considered poor (Serritzlew et al., 2014). This is the circumstance that prefigures the presence of “liberal distrust,” considered beneficial for democracy because it allows citizens to express disapproval of public officials and politicians (Bertsou, 2019). This attitude distinguishes the so‐called critical citizens, who actively commit themselves to the community because they have generalized trust but are disheartened by institutions and politics (Norris, 1999). Furthermore, in a crisis, altruistic, and supportive behaviors increase (Ipsos, 2020) and, when institutions are exceptionally ineffective, social trust among citizens increases too because this represents a coping strategy to face difficulties and uncertainty (Ervasti et al., 2018). Furthermore, considering that, due to the conditions outlined above, the relationship of trust between Sicilians and institutions is historically fragile, the particular association between civic commitment and negative attitudes to health provisions appears more plausible. Overall, our results lead us to reflect on the decline in trust of institutions, that deals with past and present circumstances: in the past, we find the events of recent history (scandals, corruption, inefficiency, etc.) that have weakened trust in institutions (Memoli, 2011; Pardo, 2018); while, in the, we find modern citizens who want to be recognized as active and competent partners (Brown, 2020) to collaborate with decision‐makers and not to passively submit to their dispositions (Coats & Passmore, 2008). Reluctance to collaborate with authorities to protect their own health and that of the community indicates that people do not see themselves as active partners in the health system (Graffigna et al., 2020) because they are warier (Hanlon et al., 2006) towards institutions. Institutions, indeed, ask citizens for trust but do not commit themselves to negotiate rules of reciprocity with citizens (Mouritsen, 2003). It is therefore necessary that policy makers promote deliberative governance processes to strengthen the trust of the most active and committed citizens and obtain their collaboration (Van de Walle & Bouckaert, 2007).

Overall, we believe that what has emerged from this work can constitute an interesting stimulus to deepen the relationships that exist between the components of social capital (sense of community, trust, and civic commitment) and responsible behaviors useful for protecting the community in crises. Furthermore, we need to understand better the reasons that induce the most active members to reject measures that can protect public health and understand the social influence of their attitudes on the belonging community.

7.1. Limitations and further investigations

The main limitation of this study is its correlational nature that is not able to clarify the causal relationships between investigated variables. Another limitation is the small size of the sample and its composition: the participants are all Sicilian and their regional affiliation gives them very specific characteristics, so the generalization of the results to other contexts must be verified; moreover, only available respondents were recruited, so the sample cannot be considered representative of the Sicilian population and the data obtained may be affected by the selection bias. Finally, in this study, we did not investigate effects of social trust, which could have better explained the relationships between the sense of community, civic engagement, and trust in institutions. Further studies should use an experimental or longitudinal design to establish a causal relationship between variables and use a more heterogeneous and more representative sample of the population. Moreover, the effects of social trust should be investigated.

ETHICAL DECLARATIONS

All participants in the study gave granted informed consent. This study was approved by the ethic committee of the Department of Educational Science, University of Catania. The material was collected anonymously after obtaining the consent of the participants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Catania within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement. [Correction added on 18 May 2022, after first online publication: CRUI funding statement has been added.]

Biographies

Graziella Di Marco, obtained her Ph.D. from University of Catania (Italy) in Basis and Methods of Educational Processes; currently, she is social psychology research fellow at Department of Educational Sciences, University of Catania, Italy. Her specializations include social identity and inter‐group relations, acculturation strategies of host and guest community. Her current research interests are in community psychology and psychology of religion.

Zira Hichy obtained her Ph.D. from University of Padova (Italy) in Personality and Social Psychology; currently, she is Associate professor in Social Psychology at the Department of Educational Sciences, University of Catania, Italy. Her specializations include intergroup relations, prejudice and its reduction, and acculturation processes. Her current research interests are in psychology of religion and political psychology.

Federica Sciacca obtained her master's degree from University of Catania in Psychology; Currently, Phd student at the Department of Educational Sciences, University of Catania, Italy. Her specializations include drug and new addiction theory and practice, health psychology and psychotherapy, and social psychology theory. Her current research interests are in gullibility theory, conspiracy's theory, personality and religious orientations.

Di Marco, G. , Hichy, Z. , & Sciacca, F. (2022). Attitudes towards lockdown, trust in institutions, and civic engagement: A study on Sicilians during the coronavirus lockdown. Journal of Public Affairs, e2739. 10.1002/pa.2739

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Acemoglu, D. , & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, R. P. , & Goggin, J. (2005). What do we mean by “civic engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3, 236–253. 10.1177/1541344605276792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese, G. , & de Blasio, G. (2018). Tratti culturali e comportamenti socio‐economici. Le differenzenord‐sud. [Cultural traits and socio‐economic behaviors. The north‐south differences]. Eyes Reg, 8, 6. https://www.eyesreg.it/2018/tratti-culturali-e-comportamenti-socio-economici-le-differenze-nord-sud/ [Google Scholar]

- Albanesi, C. , Cicognani, E. , & Zani, B. (2007). Sense of community, civic engagement and social well‐being in Italian adolescents. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 17(5), 387–406. 10.1002/casp.903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alfani, G. , & Sardone, S. (2015). Long‐term trends in economic inequality in Southern Italy. The Kingdom of Naples and Sicily, 16th‐18th centuries: First results. [Paper presentation]. Economic History Association Annual Meeting, Nashville. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/228007421.pdf

- Aoki, M. (2001). Toward a comparative institutional analysis. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, F. (2015). Economic, social and territorial situation of Sicily. In‐depth analysis. European Parliament's Committee on Regional Development. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/540372/IPOL_IDA(2015)540372_EN.pdf

- Bagozzi, R. P. , & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self‐esteem. Structural Equation Modeling, 1, 35–67. 10.1080/10705519409539961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E. C. (1958). The moral basis of a backward society. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers, R. (2012). Trust and volunteering: Selection or causation? Evidence from a 4 year panel study. Political Behavior, 34, 225–247. 10.1007/s11109-011-9165-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, M. E. , Passarelli, G. , & Serricchio, F. (2021). Decades of party distrust. Persistence through reform in Italy. Italian Journal of Electoral Studies IJES ‐ QOE, 83(2), 15–25. 10.36253/qoe-9590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsou, E. (2019). Rethinking political distrust. European Political Science Review, 11(2), 213–230. 10.1017/S1755773919000080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigoni, M. , Bortolotti, S. , Casari, M. , Gambetta, D. , & Pancotto, F. (2016). Amoral familism, social capital, or trust? The behavioural foundations of the Italian north‐south divide. The Economic Journal, 126, 594, 1318–1341. 10.1111/ecoj.12292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnskov, C. (2009). Economic growth. In Svendsen G. T. & Svendsen G. L. H. (Eds.), Handbook of social capital: The troika of sociology, political science and economics (pp. 337–353). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Boix, C. , & Posner, D. N. (1996). Making social capital work: A review of Robert Putnam's making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Harvard University. http://web.mit.edu/posner/www/papers/9604.pdf

- Bourdieu, P. (1993). Forms of capital. In Richardson J. (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research in the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, S. , & Karp, J. A. (2004). Politicians, scandals, and trust in government. Political Behavior, 26, 271–287. 10.1023/B:POBE.0000043456.87303.3a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, H. (1999). Political participation. In Robinson J. P., Shaver P. R., & Wrightsman L. S. (Eds.), Measures of politicalattitudes (pp. 737–801). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm, J. , & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual‐level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41, 999–1023. 10.2307/2111684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. (2020). The citizen and trust in the (trustworthy) state. Public Policy and Administration, 35(4), 384–402. 10.1177/0952076718811420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi, M. (2015). The trust issue in Italy. Millennials wary of corrupt media reporting. Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/journalism-and-media-ethics/resources/the-trust-issue-in-italy/

- Campagna, D. , Caperna, G. , & Montalto, V. (2020). Does culture make a better citizen? Exploring the relationship between cultural and civic participation in Italy. Social Indicators Research, 149, 657–686. 10.1007/s11205-020-02265-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cartocci, R. , & Vanelli, V. (2015). Geografia Dei processi di secolarizzazione [geography of the processes of secularization]. In Sciolla L. & Salvati M. (Eds.), L'Italia e le sue regioni. L'etàrepubblicana, vol. III [Italy and its regions. The republican age] (pp. 33–56). Istituto Enciclopedia Italiana Treccani. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni, C. , & Lozza, E. (2020). Determinants of the financial contribution to the NHS: The case of the COVID‐19 emergency in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 584473. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicognani, E. , Mazzoni, D. , Albanesi, C. , & Zani, B. (2015). Sense of community and empowerment among young people: Understanding pathways from civic participation to social well‐being. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 24–44. 10.1007/s11266-014-9481-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicognani, E. , Pirini, C. , Keyes, C. , Joshanloo, M. , Rostami, R. , & Nosratabadi, M. (2008). Social participation, sense of community and social well being: A study on American, Italian and Iranian university students. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 97–112. 10.1007/s11205-007-9222-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coats, D. , & Passmore, E. (2008). Public value: The next steps in public service reform. The Work Foundation. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.549.8241&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital and the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 94–120. 10.1086/228943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Consoli, A. , & Spagano, S. (2008). Law and institutions: Two reasons for Sicilian backwardness? Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper no. 8364. University Library of Munich, Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/8364/1/MPRA_paper_8364.pdf

- Dasgupta, P. (1988). Trust as a commodity. In Gambetta D. (Ed.), Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 49, 72). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- DelliCarpini, M. X. , Cook, F. L. , & Jacobs, L. R. (2004). Public deliberation, discursive participation, and citizen engagement: A review of the empirical literature. Annual Review of Political Science, 7, 315–344. 10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.121003.091630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demos . (2019). XXII RapportogliItaliani e lo stato [XXII Report Italians and the state]. http://www.demos.it/a01676.php

- Di Marco, G. , Hichy, Z. , & Sciacca, F. (2020). Dataset on the relationship between psychosocial resources of volunteers and their quality of life. Data in Brief, 30, 105522. 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mascio, F. , Natalini, A. , & Cacciatore, F. (2019). The political origins of transparency reform: Insights from the Italian case. Italian Political Science Review, 49(3), 211–227. 10.1017/ipo.2018.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, J. , & Vinnari, E. (2019). Critical dialogical accountability: From accounting‐based accountability to accountability‐based accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 62(C), 16–38. 10.1017/ipo.2018.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesen, P. T. (2012). Parental transmission of trust or perceptions of institutional fairness? Generalized trust of non‐Western immigrants in a high trust society. Comparative Politics, 44, 273–289. 10.5129/001041512800078986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, A. , & Faul, A. C. (2013). Civic engagement scale: A validation study. SAGE Open, 3, 1–7. 10.1177/2158244013495542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durlauf, S. N. , & Fafchamps, M. (2005). Social capital. In Aghion P. & Durlauf S. (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (pp. 1639–1699). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, T. (1997). Civic learning: Democracy and education revisited. Educational Record, 78, 57–65. https://pullias.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/ehrlich.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, J. , & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22(3), 283–300. 10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti, H. , Kouvo, A. , & Venetoklis, T. (2018). Social and institutional trust in times of crisis: Greece, 2002–2011. Social Indicators Research, 141, 1207–1231. 10.1007/s11205-018-1862-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . (2017). My region, my Europe, our future. Seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cohesion7/7cr.pdf

- Fazio, A. (2003). Culture and the development of southern Italy. Economic Bulletin, 36, 93–104. https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/bollettino-economico/2003-0001/en_bull_36tot.pdf?language_id [Google Scholar]

- Felice, E. , & Vasta, M. (2015). Passive modernization? The new human development index and its components in Italy's regions (1871–2007). European Review of Economic History, 19(1), 44–66. 10.1093/ereh/heu018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A. R. , & Nisticò, R. (2019). Does institutional quality matter for multidimensional well‐being inequalities? Insights from Italy. Social Indicators Research, 145, 1063–1105. 10.1007/s11205-019-02123-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francescato, D. , Arcidiacono, C. , Albanesi, C. , & Mannarini, A. T. (2007). Community psychology in Italy: Past developments and future perspectives. In Reich S. M., Riemer M., Prilleltensky I., & Montero M. (Eds.), International communitypsychology: History and theories (pp. 263–281). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust the social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Hamish Hamilton. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, E. , Rizzo, I. , & Scaglioni, C. (2017). Transparency, quality of institutions and performance in the Italian municipalities. [Working Papers]. Lisbon School of Economics and Management, Department of Economics, Universidade de Lisboa. https://depeco.iseg.ulisboa.pt/wp/wp112017.pdf

- Graffigna, G. , Barello, S. , Savarese, M. , Palamenghi, L. , Castellini, G. , Bonanomi, A. , & Lozza, E. (2020). Measuring Italian citizens' engagement in the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic containment measures: A cross‐sectional study. PloSone, 15(9), e0238613. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffigna, G. , Palamenghi, L. , Savarese, M. , Castellini, G. , & Barello, S. (2021). Effects of the COVID‐19 emergency and National Lockdown on Italian Citizens' economic concerns, government trust, and health engagement: Evidence from a two‐wave panel study. The Milbank Quarterly, 99, 1–24. 10.1111/1468-0009.12506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundelach, B. (2020). Political consumerism as a form of political participation: Challenges and potentials of empirical measurement. Social Indicators Research, 151, 309–327. 10.1007/s11205-020-02371-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield, J. R. (1975). Community: A critical response. Barnes & Noble. [Google Scholar]

- Hackl, F. , Halla, M. , & Pruckner, G. J. (2009). Volunteering and the state. Public Choice, 151, 465–495. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41406939 [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon, G. W. , Strangleman, T. , O'Cathain, A. , Luff, D. , Goode, J. , & Greatbatch, D. (2006). Risk society and the NHS. From the traditional to the new citizen? Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 17, 270–282. 10.1016/j.cpa.2003.08.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heller, K. (1989). The return to community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17, 1–15. 10.1007/BF00931199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzner, B. , & Holzner, L. (2006). Transparency in global change: The vanguard of the open society. University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, B. , & Mascherini, M. (2009). Measuring active citizenship through the development of a composite indicator. Social Indicators Research, 90(3), 459–488. 10.1007/s11205-008-9271-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, J. B. (2002). Exploring social capital and civic engagement to create a framework for community building. Applied Developmental Science, 6, 196–202. 10.1207/S1532480XADS0604_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPSOS . (2020). La rabbia prossima ventura [Anger iscomingsoon] . https://www.ipsos.com/it-it/la-rabbia-prossima-ventura

- Istat, Istituto Nazionale di statistica [National Statistical Institute] . (2019). Dati statistici per il territorio, Regione Sicilia [Statistical data for the territory, Region of Sicily]. https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/05/19_Sicilia_Scheda.pdf

- Istat, Istituto Nazionale di statistica [National Statistical Institute] . (2020). Impatto dell'epidemia COVID‐19 sulla mortalità totale della popolazione residente. Primo trimestre 2020. [Impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on the total mortality of the resident population. First quarter 2020]. https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/05/Rapporto_Istat_ISS.pdf

- Jacoby, B. , & Associates. (2009). Civic engagement in higher education: Concepts and practices. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, M. K. , & Stoker, L. (2004). Social trust and civic engagement across time and generations. Acta Politica, 39, 342–379. 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K. G. , & Sörbom, D. (1996. ‐2001). LISREL 8user's reference guide. Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, J. , Carman, K. G. , DeYoreo, M. , Chandler, N. , & Davis, L. E. (2020). The drivers of institutional trust and distrust: Exploring components of trustworthiness. RAND Corporation. 10.7249/RRA112-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, S. , & Iorio, F. (2020). Building trust in government through citizen engagement. World Bank Group. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/33346 [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, M. , Sabelfeld, S. , Blomkvist, M. , & Dumay, J. (2020). Rebuilding trust: Sustainability and non‐financial reporting and the European Union regulation. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(5), 701–725. 10.1108/MEDAR-06-2020-0914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, R. D. , & Weiss, E. S. (2003). Broadening participation in community problem solving: A multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. Journal of Urban Health, 80(1), 14–47. 10.1093/jurban/jtg014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi, M. , & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 475–507. 10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. (2001). Building a network theory of social capital. In Lin N., Cook K., & Burt R. S. (Eds.), Social capital: Theory and research (pp. 3–29). Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D. W. , & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I [Google Scholar]

- Memoli, V. (2011). Government, scandals and political support in Italy. Interdisciplinary Political Studies, 1, 2. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/84824591.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. , & Listhaug, O. (1999). Political performance and institutional trust. In Norris P. (Ed.), Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government (pp. 204–216). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Möllering, G. (2006). Trust: Reason, routine, reflexivity. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen, P. (2003). What's the civil in civil society? Robert Putnam's Italian republicanism. Political Studies, 51, 650–668. 10.1111/j.0032-3217.2003.00451.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nannestad, P. (2008). What have we learned about generalized trust, if anything? Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 413–436. 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nifo, A. , & Vecchione, G. (2015). Measuring institutional quality in Italy. Rivista Economica del Mezzogiorno [Economic Journal of the South], 1‐2, 157–182. https://www.rivisteweb.it/download/article/10.1432/80447 [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic governance. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nugnes, F. (2019). Transparency as a tool against corruption? The case of Italy. RivistaTrimestrale di Scienzadell'Amministrazione, 2[Quarterly Journal of Administration Science]. http://rtsa.eu/RTSA_2_2019_Nugnes.pdfOECD

- Okun, M. A. , & Michel, J. (2006). Sense of community and being a volunteer among the young‐old. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 25(2), 173–188. 10.1177/0733464806286710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co‐operation and Development . (2017). Trust and public policy: how better governance can help rebuild public trust. OECD Public Governance Reviews. 10.1787/9789264268920-en [DOI]

- Ortiz‐Ospina, E. , & Roser, M. (2016). Trust. Our World in Data . https://ourworldindata.org/trust

- Pardo, I. (2004). Where it hurts: An Italian case of graded and stratified corruption. In Pardo I. (Ed.), Between morality and the law: Corruption, anthropology and comparative societies (pp. 33–52). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, I. (2018). Corrupt, abusive, and legal: Italian breaches of the democratic contract. Current Anthropology, 59(18), 560–571. 10.1086/695804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, P. (2007). Association memberships and generalized trust: A multilevel model across 31 countries. Social Forces, 86, 47–76. 10.1353/sof.2007.0107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, P. (1995). The cunning of trust. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 24, 202–225. 10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00029.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, S. , Caputo, F. , & Venturelli, A. (2020). Accounting to ensure healthy lives: Critical perspective from the Italian National Healthcare System. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20, 445–460. 10.1108/CG-03-2019-0109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polavieja, J. (2013). Economic crisis, political legitimacy, and social cohesion. In Gallie D. (Ed.), Economic crisis, quality of work and social integration: The European experience (pp. 256–278). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prezza, M. , Costantini, S. , Chiarolanza, V. , & Di Marco, S. (1999). La scala italiana del senso di comunità [The Italian scale of sense of community]. Psicologia della Salute [Health Psychology], 3(4), 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Prezza, M. , & Pacilli, M. G. (2007). Current fear of crime, sense of community and loneliness in Italian adolescents: The role of autonomous mobility and play during childhood. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(2), 151–170. 10.1002/jcop.20140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raiser, M. (1999). Trust in transition. [working paper, no. 39]. EBRD. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.138.3727&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Rasmussen Global . (2018). Democracy Perception Index 2018. https://www.allianceofdemocracies.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Democracy-Perception-Index-2018-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. , Subramanian, F. , & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 131–165. 10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031425.72248.85 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, F. , Nowak‐Lehmann, F. , & Otter, T. (2011). Has the financial crisis shattered citizens' trust in national and European governmental institutions? [working document, no. 343]. Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS). https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/WD%20343%20Roth%20et%20al%20on%20trust.pdf

- Sarason, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Scavo, A. (2020). Citizens and institutions in the time of covid‐19.Scenario, new cleavages, implications. IPSOS. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-05/andrea-scavo-2-3_versione_breve.pdf.

- Serritzlew, S. , Sønderskov, K. M. , & Svendsen, G. T. (2014). Do corruption and social trust affect economic growth? A review. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 16, 121–139. 10.1080/13876988.2012.741442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sivesind, K. H. , Pospíšilová, T. , & Frič, P. (2013). Does volunteering cause trust? European Societies, 15, 106–130. 10.1080/14616696.2012.750732 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SVIMEZ . (2019). Rapportosull'economia del Mezzogiorno [Report on the economy of the South]. http://lnx.svimez.info/svimez/rapporto-2019-tutti-i-materiali/

- Sztompka, P. (1999). Trust: A sociological theory. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Talò, C. , Mannarini, T. , & Rochira, A. (2014). Sense of community and community participation: A meta‐analytic review. Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality‐of‐Life Measurement, 117(1), 1–28. 10.1007/s11205-013-0347-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torcal, M. (2014). The decline of political trust in Spain and Portugal: Economic performance or political responsiveness? American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 1542–1567. 10.1177/0002764214534662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, T. (2017). Developing a “sense of community”: Exploring a cognitive component of civic engagement. eJournal of Public Affairs, 6(3), 7–34. http://www.ejournalofpublicaffairs.org/wp‐content/uploads/2018/02/107_Developing‐a‐Sense‐of‐Community‐Exploring‐a‐Cognitive‐Component‐of‐Civic‐Engagement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (2015). Sustainable Development Goals . https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Van de Walle, S. , & Bouckaert, G. (2007). Public service performance and trust in government: The problem of causality. International Journal of Public Administration, 29(8), 891–913. 10.1081/PAD-120019352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ingen, E. , & Bekkers, R. (2013). Generalized trust through civic engagement? Evidence from five national panel studies. Political Psychology, 36, 277–294. 10.1111/pops.12105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, C. , Raiser, M. , Haerpfer, C. & Nowotny, T. (2002). Social capital in transition: A first look at the evidence. Czech Sociological Review, 38(6), 693‐720. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-56305 [Google Scholar]

- World Values Survey . (2006). Questionario per l'indaginesulmutamentodeimodelli di “civismo”: Cittadinanza, identità e valori in Europa [questionnaire for the survey on the change of models of "civism": Citizenship, identity and values in Europe]. Italy, 2005–2006. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:h216nCLaYBkJ:hostingwin.unitn.it/micciolo/PhD/Italy_WVS_2005%2520-%2520questionario.pdf+&cd=1&hl=it&ct=clnk&gl=it

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.