Summary

The COVID‐19 pandemic has challenged the delivery of health services. Telehealth allows delivery of care without in‐person contacts and minimizes the risk of vial transmission. We aimed to describe the perspectives of kidney transplant recipients on the benefits, challenges, and risks of telehealth. We conducted five online focus groups with 34 kidney transplant recipients who had experienced a telehealth appointment. Transcripts were thematically analyzed. We identified five themes: minimizing burden (convenient and easy, efficiency of appointments, reducing exposure to risk, limiting work disruptions, and alleviating financial burden); attuning to individual context (depending on stability of health, respect patient choice of care, and ensuring a conducive environment); protecting personal connection and trust (requires established rapport with clinicians, hampering honest conversations, diminished attentiveness without incidental interactions, reassurance of follow‐up, and missed opportunity to share lived experience); empowerment and readiness (increased responsibility for self‐management, confidence in physical assessment, mental preparedness, and forced independence); navigating technical challenges (interrupted communication, new and daunting technologies, and cognizant of patient digital literacy). Telehealth is convenient and minimizes time, financial, and overall treatment burden. Telehealth should ideally be available after the pandemic, be provided by a trusted nephrologist and supported with resources to help patients prepare for appointments.

Keywords: COVID‐19, patient‐centered care, telehealth

Kidney transplant recipients participated in focus groups to determine their experience with telehealth which replaced their face‐to‐face nephrology clinics during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Recipients believe that telehealth should be available after the pandemic.

Introduction

Since coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) was declared a pandemic in March 2020, many specialist clinics worldwide rapidly adopted telehealth to minimize the risk of infections [1]. This is particularly relevant for kidney transplant recipients who are at increased risk of severe COVID‐19 infection due to immunosuppressive therapy and co‐morbidities including diabetes and hypertension [2].

Telehealth is the use of telecommunication, usually by telephone or video call, to provide a clinical consultation [3]. Prior to COVID‐19, telehealth had been available mostly for patients who did not require interventions at the time of consultation or those who live in rural and remote communities who, in addition to limited access to specialist care, face other significant challenges that affect the mental and physical well‐being of patients [4, 5, 6]. Telehealth has been shown to be a cost‐effective, viable, and a convenient option for kidney transplant recipients and may be associated with increased health literacy [7, 8, 9]. In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), studies have shown that patient outcomes, including hospitalization, are similar for telehealth compared with face‐to‐face appointments [10]. Barriers to telehealth consultations include limited access to technology and digital literacy as well as existing funding models (in a public healthcare system) [11, 12]. Experiences of delivering telehealth consults to kidney transplant recipients during the COVID‐19 pandemic demonstrated that telehealth is a feasible and effective way to manage patients remotely [13].

However, little remains known about the experience of telehealth among kidney transplant recipients. The aim of this study was to describe the perspectives of kidney transplant recipients on telehealth during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The results from this study may inform strategies to optimize access and implementation of telehealth for kidney transplant follow‐up.

Methods

Context

The Australian Government announced a health package to support the delivery of telehealth consultations to those who were most vulnerable to COVID‐19 infection, including those who were immunosuppressed until March 2021 [14]. Across Australia, most consultations for outpatient follow‐up of kidney transplant recipients were delivered through telehealth from March 2020. A framework on how to conduct a telehealth visit is available to clinicians, including obtaining consent to conduct a telehealth appointment, and ensuring that privacy and data security are protected.

Participation selection and recruitment

Kidney transplant recipients over the age of 18 years were eligible to participate. All participants had to be English‐speaking and able to give informed and voluntary consent. We took an inclusive approach and invited participants through the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) Patient Network, the Kidney Health Australia Patient Network, the Transplant Australia Patient Network as well as social media. Ethics approval was provided by The University of Sydney (2020‐217).

Data collection

Each participant attended one of five one‐hour focus groups, convened in August 2020 using ZOOM videoconferencing. Each group consisted of between 5 and 10 participants. The question guide was developed from the literature and discussion among the investigator team, which included two members with lived experience of kidney transplantation (Data S1). The question guide covered the following topics: use of telehealth, benefits and challenges, the impact on communication, changes in care, self‐management, follow‐up after telehealth appointments, and suggestions for use of telehealth. An investigator (BMH, AT, AB, and NSR) facilitated each group, and a co‐facilitator took field notes. We convened groups until we reached data saturation, when little or no new concepts were arising from subsequent groups. All groups were recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis

All transcripts were imported into HyperRESEARCH software (version 3.7.5 ResearchWare Inc) to facilitate data analysis. Using thematic analysis, author BMH inductively identified initial concepts related to the participant perspectives on the use of telehealth in post‐kidney transplantation care. Similar concepts were grouped into preliminary themes and subthemes, which were discussed with the facilitator team (BMH, NSR, CG, AB, NA, and AT), and sent to participants for comment. This ensured that the final analysis reflected the full range and depth of the data obtained. A thematic schema was developed to summarize and depict conceptual links among the themes.

Results

Of the 53 participants confirmed to attend, 34 (64%) kidney transplant recipients participated in five focus groups. 18 (53%) were women, 16 (47%) received their transplant from deceased donors, and 18 (53%) lived in metropolitan areas. All participants had experience with a telehealth consult with a nephrologist, either by a telephone call, or video call. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 34).

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 18 | 53 |

| Male | 16 | 47 |

| Age Group (years) | ||

| 18‐30 | 2 | 6 |

| 31‐50 | 16 | 47 |

| 51‐70 | 12 | 35 |

| 71+ | 4 | 12 |

| Employment status | ||

| Working | 19 | 53 |

| Not working | 15 | 47 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 4 | 11 |

| Married or partnered | 25 | 74 |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 5 | 15 |

| Highest level of Education | ||

| Primary School | 3 | 9 |

| Professional certificate | 9 | 26 |

| University | 22 | 65 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 27 | 79 |

| Other (please specify)* | 7 | 20 |

| Children number | ||

| 0 | 13 | 38 |

| 1 or 2 | 14 | 41 |

| 3 or more | 7 | 21 |

| Cause of Kidney disease | ||

| Glomerular disease (e.g., GN/FSGS/IgA Nephropathy) | 8 | 23 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3 | 9 |

| Reflux nephropathy | 2 | 6 |

| Diabetes | 2 | 6 |

| Infection | 1 | 3 |

| Other (please specify)† | 18 | 53 |

| Donor Type | ||

| Deceased donor | 16 | 47 |

| Living donor | 18 | 53 |

| Years post‐Tx | ||

| Less than 1 year | 4 | 12 |

| 1‐2years | 10 | 29 |

| 3 or more years | 20 | 59 |

| Number of transplants | ||

| 1 | 28 | 82 |

| 2 or 3 | 6 | 18 |

| More than 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Telehealth used | ||

| Telephone call (mobile, house phone) | 26 | 74 |

| Video call (mobile phone, tablet, computer) | 13 | 37 |

| Additional telehealth attendees | ||

| No one | 32 | 94 |

| Caregiver/family member | 2 | 6 |

| Previously used telehealth? | ||

| Yes | 4 | 12 |

| No | 30 | 88 |

| Location | ||

| Metropolitan | 18 | 53 |

| Regional | 16 | 47 |

Other includes South Central Asian, African and Middle Eastern.

Other includes unknown cause (n = 4), autoimmune disease (n = 1), Henoch Schonlein purpura (n = 1), multiple organ failure (n = 1), systemic lupus erythematosus (n = 1), surgical negligence (n = 1), Alports syndrome (n = 3), cystic fibrosis (n = 1), medullary sponge kidney (n = 1), multiple myeloma (n = 1), autosomal recessive nephronophthisis (n = 1), atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (n = 1), medullary cystic (n = 1).

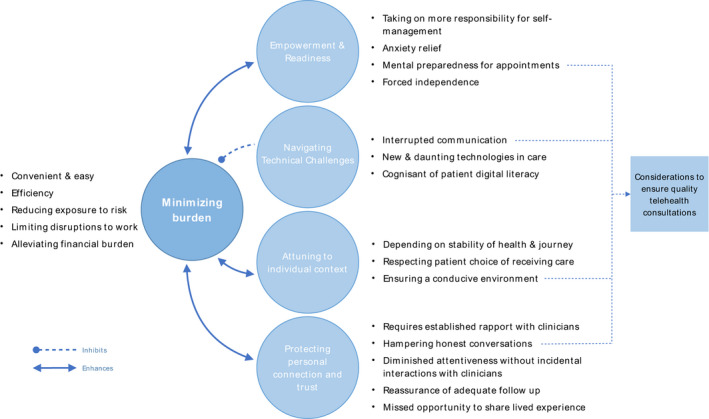

We identified five themes, which are described in the following section, and selected quotations to support each theme are provided in Table 2. The thematic schema is provided in Fig. 1. Themes that were specific to a particular group (i.e., based on age and location of residence) are described accordingly.

Table 2.

Selected illustrative quotations for each theme.

| Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Minimizing burden | |

| Convenient and easy |

If it's a 9:00 [face‐to‐face] appointment, I have to leave at 5:30, 6:00 in the morning to beat the traffic so telehealth was a welcome. (M, 40’s, Reg) It's inconvenient to drive. I always felt like I was there for like 10 minutes and then I had to drive all the way back. (F, 40’s, Met) Now [with telehealth] it's very convenient for me because I can even take calls while I'm working in the office or whether I'm home. (F, 40’s, Met) |

| Efficiency of appointments |

A telehealth appointment tends to be quicker than personal [face‐to‐face] appointments, with the same information. (M, 50’s, Met) Telehealth has made medical visits more efficient, more effective, and going forward out of COVID with economic recovery, it probably needs to happen. (M, 40’s, Reg) They just get more to the point, tell you what you need to know. It's quicker. It’s a better communication system really. (F, 40’s, Reg) |

| Reducing exposure to risk |

It was a safe thing, I've only had my transplant a year, so I didn't want to take a risk going out, going to hospitals. (M, 50’s, Met) Driving through traffic for a country person it's quite stressful. (F, 40’s, Reg) I like not having to go in and sit in a waiting room with a group of other immunosuppressed people, that I think it's just asking for trouble. (F, 30’s, Reg) |

| Limiting work disruptions |

If I was traveling up every time [for face‐to‐face appointments], that would be a full‐time job, and I wouldn't be in a situation where I could consider turning to the workforce. (F, 30’s, Reg) I started a new workplace this year so being able to just have that convenience and not let it disrupt my work is been really important. (F, 20’s, Met) There's the time off work aspect, and you can't just pop in before work of a day, it's a whole day. And with a blood test in the mornings and maybe it's an overnight stay. (F, 30’s, Reg) |

| Alleviating financial burden |

I'm saving a lot of petrol at the moment. (F, 40’s, Met) Even though I was in a two‐hour parking space, I ended up with a parking ticket. (M, 50’s, Met) |

| Attuning to individual context | |

| Depending on stability of health |

This is my third transplant, and my doctor said to me, "Look, I'm happy for it to be telehealth, come and see, physically, on and off time, and then the next time seeing telehealth." (F, 40’s, Met) The sicker I was, the more I'd want to see someone in person, and the healthier I am, I probably feel a little bit less inclined to go in in person. (M, 50’s, Met) It should be a bespoke approach patient by patient, because everyone is different and every individual need is different, depending on where you are along the transplant timeline. (F, 40’s, Met) |

| Respect patient choice of care |

I prefer to go in because I can get my scrips that I need and speak to him personally if I've got any issues. (M, 50’s, Met) I think it should, but as long as you have the option. And some people won't want to use it, and some people will, so I definitely think it should continue. (F, 60’s, Reg) Just having that option to do it like this, as we've said it's much more efficient and convenient, particularly for those people living in rural areas that have to travel great distances. It's sort of unbelievable that they didn't have this already set up I think. And yeah, shouldn't they fund that when it's so clearly benefited all of us here? (M, 20’s, Met) |

| Ensuring a conducive environment |

Because I think face‐to‐face, you're in the room, you're kind of in the moment, with telehealth, you can get distracted. You can get a bit confused (F, 50’s, Met) When I go into the hospital the whole thing is distracting, and sometimes I forget something. But if I'm sitting in front of a computer I've got lots of time and I usually have a list of things right by me. (F, 60’s, Met) If you're doing telehealth, then you might miss something like the dog barking in the background, or the kids screaming. (M, 50’s, Met) The issue is that the information that I'm discussing is of a highly confidential nature. Whereas the old face‐to‐face stuff, I could talk without having another person there. (M, 40’s, Met) |

| Protecting personal connection and trust | |

| Requires established rapport with clinicians |

I am a little bit more recent with my transplant, and I've had seven teams involved since March. So I haven't necessarily developed a particular working relationship with any practitioners. And that's a bit of a challenge (F, 30’s, Reg) Telehealth only works if you've already built your relationship with someone. I think there's going to be an initial period of face‐to‐face for you to get to understand them, and they understand you (F, 30’s, Reg) I think you can build a relationship with people through telehealth. We do it in business all the time and even maybe more so this year. It just takes some investment and patience from both sides. (F, 40’s, Met) |

| Hampering honest conversations |

I like face‐to‐face because my doctor tells me if he's thinks that I'm putting on weight, or I'm not doing the right thing. (M, 50’s, Met) There's been a few times where I've been feeling pretty low… and that's at the point where I do want to be there in person and have a proper talk about it (M, 20’s, Met) Nonverbal communication is most of our communication, so I think that's important. (M, 40’s, Met) |

| Diminished attentiveness without incidental interactions |

Nurses are a part of my training team as a nephrologist, and I feel that connect with the nurses completely cut off [with telehealth] (M, 30’s, Met) When I do telehealth, you become sort of like missing out on all the other aspects of allied health (M, 30’s, Met) That the doctor is really important, but I think more important are the nurses. I actually miss that talking to them. The doctor it's very medical, biological kind of stuff, whereas with the nurses, you can talk more holistic. (M, 50’s, Met) |

| Reassurance of follow‐up |

I'm struggling a fair bit with follow‐up. I'm still having blood tests weekly to check my drug mixture. I've had to go in to get an injection, but they sent the request forms via the mail which takes two or three weeks. So invariably they're not here [when I need them]. (M, 70’s, FG2, Met) So with telehealth they send my scripts straight to the pharmacy (M, 20’s, Met) Not everyone is using email or has access to email and maybe even SMS. There is a diverse group of people that have kidney disease, so it's important that nephrologists have an option of ways of contacting people. (F, 50’s, Met) |

| Missed opportunity to share lived experience |

What I find I don't like about [telehealth] is that I miss the group of people who had transplants at the same time as me, I like catching up with them. (F, 60’s, Met) It is good to get to know the other people in the hospital as well (F, 40’s, Met) |

| Empowerment and readiness | |

| Increased responsibility for self‐management |

Telehealth was a bit of a let down in terms of preparation. I feel confident when my blood pressure been checked by my doctor (M, 30’s, Met) When I knew I had a telehealth appointment coming up, I write down all the particulars, and make sure that I had the information available. It makes it a lot quicker for the doctor as well. (M, 50’s, Met) It's good if you take a bit of responsibility for your own health as well, keeps you on track. (F, 40’s, Met) |

| Confidence in physical assessment |

I looked at it [my wound], it was just getting worse and worse and worse, so I had to go and see her, just to make sure. that the medication that were taking was actually killing the infection that I had. (M, 50’s, Met) [The clinicians are] missing something by not putting their hands on a patient. They're not doing the job in the same way. (F, 30’s, Reg) |

| Mental preparedness |

I have to wait by my phone, so I have to be very alert. When I go to my nephrologist [face‐to‐face], that's a different mindset I am on when I'm not with my nephrologist (M, 60’s, Met) You can receive a [telehealth] call at any time. If you miss the call, sometimes there will be a voice message. It's a psychological issue for me, because if I am at work I have to find a different room to go and talk about personal issues (M, 30’s, Met) |

| Forced independence |

No, [my wife does not come with me to telehealth appointments] because she works during the day. But if I've got a [face‐to‐face] appointment, she'll come with me (M, 50’s, Met) I prefer face‐to‐face, and I prefer to be able to take my husband with me, because he prompts me to ask the right sorts of questions (F, 70’s, Reg) |

| Navigating technical challenges | |

| Interrupted communication |

With a lot of the technology that's used by the hospitals is really old. (M, 50’s, Met) Like when the internet's down, when it's slow, which it is often at my place. Even my phones aren't that good. The landline, even… Just depends on if everything's working. (F, 70’s, Reg) |

| New and daunting technologies |

I've got my doctors mobile phone number so if I have any issues, I know I can text him with that, and he'd get back to me that day. (M, 50’s Met) I've had appointments where I've got on the telehealth and then the doctor's got on and said, "My camera doesn't work, can you hang up and I'll call your mobile." There's definitely been some hiccups along the way (F, 30’s, Reg) The focus has been on the patient side and getting telehealth up and running, but less on the clinician training side of things and making sure that they understand what makes a good telehealth consult. (F, 40’s, Met) |

| Cognizant of patient digital literacy |

I think for older people that it's sometimes a bit difficult with the technology. (F, 70’s, Reg) When you have people from multicultural diverse backgrounds they need an interpreter in the appointment (M, 30’s, Met) People with impaired decision‐making capacity, people with disabilities… Even if they did have the capacity to understand what's being said. (M, 40’s, Met) I think there does need to be a bit more thought around the cultural safety telehealth. (F, 50’s, Met) |

F, female; M, male; Met, metropolitan; Reg, regional.

Figure 1.

Thematic Schema. Participants felt that telehealth significantly minimized the burden of treatments and enhanced their sense of empowerment for self‐management. This was supported by having an established rapport with their treating nephrologist, and being able to have telehealth consults that were attuned to their individual context in terms of their health status, preferences, circumstances, and environment. However, some faced technical challenges and missed the opportunities to interact with other kidney transplant recipients and multidisciplinary clinicians.

Minimizing burden

Convenient and easy

Participants believed they could integrate telehealth appointments into their lifestyle more readily than attending face‐to‐face appointments. They gained more time because they were not required to travel and wait at the clinic for long periods of time to have a “15‐minute consultation” with the doctor.

Efficiency of appointments

Participants felt telehealth made appointment times shorter, with the same information exchanged as a face‐to‐face appointment. One patient commented that prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic, they had questioned “Why do I need to go in? Why can’t they just ring me and tell me I’m ok?”.

Reducing exposure to risk

For participants, telehealth enabled them to stay home and avoid the risk of being exposed to infections pathogens in the “clinic waiting room with other immunocompromised people.” Eliminating the need to drive to appointments meant that participants felt safe as this limited the risk of car accidents, particularly for regional/rural participants who had long commutes to the hospital.

Limiting work disruptions

Some participants emphasized that telehealth interfered less with their work as they no longer had to travel to or wait for clinic appointments. Less guilt was experienced by participants as they could better commit to their work and no longer disappoint their employer. One participant said they could start contemplating returning to work as traveling to clinic was a “full‐time job” which meant they previously “wouldn’t be in a situation where I could consider returning to the workforce.”

Alleviating financial burden

Participants noted they were “saving a lot on petrol” and not losing income from “having to take time off work.” Savings on expensive hospital parking costs were also mentioned as a benefit for telehealth appointments.

Attuning to individual context

Depending on stability of health

Participants recognized that a flexible approach to telehealth would be required taking into account their health status and prior experience with the health system—“the sicker I was, the more I'd want to see someone in person, and the healthier I am, I probably feel a little bit less inclined to go in in‐person.” Under certain circumstances, such as “being early in your transplant journey” or having something “seriously wrong,” participants felt that a face‐to‐face appointment (verses a telehealth appointment) would better alleviate any stress felt as they could be physically examined by their doctor and be close to the hospital if they needed to be admitted.

Respecting patient choice of care

Participants believe that the choice of telehealth or face‐to‐face appointments should be “for the patient to decide” and “customized to each patient.” Considerations should include the number of clinic appointments required in a year, patient employment/work, and life commitments of patients, necessity of face‐to‐face or physical examination, and whether the patient thinks their issues can be resolved by a telehealth appointment.

Ensuring a conducive environment

Distractions at home, such as “dogs barking,” “loud vehicles”, or “kids screaming,” limited the ability of some participants to fully engage with their telehealth appointment. The confidentiality of information shared during appointments meant that some participants preferred the privacy of the doctor’s office when face‐to‐face, because some were not comfortable sharing sensitive information in their own home or workplace. Some participants found it beneficial to be “sitting in front of the computer” and “having a list of things” to ask the doctor.

Protecting personal connection and trust

Requires established rapport with clinicians

Participants reported that already having a trusted clinician was essential to using telehealth because “you can’t establish trust or a connection with someone straight away over a video conference call.” Others recognized that in the context of the pandemic, people were rapidly adapting to technology and had to build relationships over video‐conferencing platforms which “takes some investment and patience from both sides.” For participants who had a long‐standing relationship with their nephrologist, telehealth meant that these relationships were not as sociable and they missed “the relationship with [their] nephrologist.”

Hampering honest conversations

Nonverbal communication comprises “most of our communication,” which participants felt they lost in telehealth appointments—both in telephone and video calls. While video calls “work much better because you do feel like you’re sitting there and not just talking to a black screen,” some participants felt “maybe you cannot be quite as honest” or speak as openly about concerns including side effects of medications and sensitive topics like their psychological status. They also compared telehealth with face‐to‐face appointments where clinicians could observe their health more comprehensively to provide candid advice—“if he [my doctor] thinks I am putting on weight, he tells me straight away.”

Diminished attentiveness without incidental interactions

Some missed interactions with other clinicians besides their nephrologist, including nurses, psychologists, social workers, and dieticians. They felt they were not receiving the “nonurgent” care, like seeing “the social worker and touching base” with them about their transplant journey and mental health requirements. While participants felt that missing these interactions did not affect their immediate health, some believed that being reminded to make follow‐up appointments with other health services was important to their long‐term care.

Reassurance of follow‐up

For participants, telehealth did not substantially limit their ability to access prescriptions for medications, blood pathology request forms, medications, and ability to make future appointments. Participants found the process easier as “[prescriptions] scripts [are now] faxed straight through to the pharmacy” and the next “blood tests [arrive] in the mail three or four days later.”

Missed opportunity to share lived experiences

Some participants were saddened when they could not see, interact, or share experiences with other patients who were “in the same predicament” which could normally help to alleviate their worries and normalize the ups and down of their individual transplant experience.

Empowerment and readiness

Increased responsibility for self‐management

Telehealth appointments required more preparation for participants including taking their own measurements such as blood pressure, weight, temperature, and sugar levels. Participants accepted these additional responsibilities and did not perceive an added burden in terms of self‐management—“I do my own weight, blood pressure and pulse all before jumping online.” Some participants “had the equipment already” needed for these measurements and “don’t think it’s a bad thing” being prepared and knowing these measurements as “it makes you more aware of what is happening to you.”

Confidence in physical assessment

With telehealth, participants felt that the nephrologists could be “missing something by not … putting their hand on a patient.” Some participants sent photographs of “wounds” or “scars” to their clinician, but some had difficulty conveying the scale of the wound or getting good photographs. However, they were confident that if they felt something was seriously “wrong” or they had “problems,” they still had the option of seeing their doctors for a physical examination.

Mental preparedness

For participants, telehealth appointments usually happened between a specific timeframe, while others were not given a timeframe meaning that telehealth phone calls occurred at any time during the day. Participants felt that switching from a social/work mentality to a “medical” frame of thinking was sometimes difficult at home, “so it’s hard to turn that mindset on when you are talking to with the doctor … with zoom.” Participants felt that “writing down all my questions” prior to a telehealth appointment helped them have a constructive appointment that was “the same as when you go face‐to‐face.”

Forced independence

Participants usually attended telehealth appointments alone, meaning “the burden on [the] caregivers has been greatly reduced.” Some felt that not having a family member or caregiver, who would usually attend face‐to‐face appointments, meant they could not “prompt me to ask the right sort of questions” or “have different questions” that the participant might not have thought of.

Navigating technical challenges

Interrupted communication

Some participants found that at times “technology hasn’t stood up” which delayed appointments resulting in telephone calls instead of video calls. Participants often preferred video telehealth appointments; however, they were sometimes requested by their clinician to have a telephone call otherwise “voices” and “videos would drop out” during a video telehealth call. Participants found technology issues stressful whether they were experienced by themselves or their clinician.

New and daunting technologies

Participants generally appreciated that their doctor was now more likely to contact them using other forms of digital technologies, including email or text message in between telehealth appointments——“she rang me immediately, got the script to me within one minute to my email, I simply printed it.” However, some participants felt they were ill prepared for their first telehealth appointment, including how to use the video call system and what measurements they were required to have completed, and wanted more detailed instructions on how to be prepared for a telehealth appointment. Some participants felt that their doctors experienced a “learning curve” and were not familiar with technology which resulted in a less effective telehealth consultation.

Cognizant of patient digital literacy

Participants considered telehealth appointments, particularly video calls, to be difficult for “older people,” the “technologically challenged” and even people who were resistant to “learning anything new” about technology. Other groups who may face challenges when it comes to telehealth appointments include those from multicultural backgrounds who “may need an interpreter” or have concerns about “cultural safety,” those with “impaired decision‐making capacity” and communities where access to technology (like computers) is limited or internet connections are sluggish.

Discussion

For kidney transplant recipients, telehealth offered protection against the risk of viral infection, provides more time while being cost‐efficient, and was considered convenient with limited disruption to their life activities, such as work and other daily chores. They found that trust and familiarity with the nephrologist supported open communication during appointments. Some learned that they had to be adequately prepared for telehealth appointments as they had to take on more responsibility for health monitoring, including measuring their weight, temperature, and blood pressure prior to a telehealth appointment. Patients had to ensure they were mentally ready for the consult and had an appropriately private environment for telehealth appointments, especially those in work situations. Patients also felt that the loss of nonverbal cues, missed opportunities to interact with other patients and multidisciplinary clinicians, and not having a caregiver or family member present were challenges with telehealth. The lack of digital and technology literacy, particularly among patients from culturally and linguistically diverse populations, may pose potential barriers for implementation of telehealth into the wider transplant community.

Kidney transplant recipients in both regional areas and metropolitan areas found that telehealth minimized their health burden because it was more convenient and efficient. Patients residing in both regional and metropolitan areas gained additional time as they were no longer required to wait for extensive periods in waiting rooms for a face‐to‐face appointment and also felt safer with minimizing risks related to travel (i.e., car accidents and stress from traffic). We noted some differences among participants based on time since transplant. Patients who were transplanted within the past 12 months at the time of the focus groups found it more difficult to navigate the medical system using telehealth because it was less familiar to them and they had less opportunity to establish rapport with their transplant nephrologists. Patients are generally referred to a specialist or specialist team in an outpatient clinic for regular follow‐up after transplantation. These follow‐ups occur more regularly early on after transplantation and lessen the more stable a patient is and the more time that has passed since transplantation [6].

One of the challenges with the transition to telehealth identified by the participants was the loss of in‐person interaction, which was more difficult for patients who were less familiar with their clinicians. While this was minimized when telehealth appointments were conducted by video, participants still felt that the loss of nonverbal cues and the ability to have conversations about sensitive topics were difficult. A recent study conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic found that physicians preferred video consultations over phone consultations to better establish and maintain rapport with patients and acknowledged that training was required. Similar to our study, some patients with diabetes preferred face‐to‐face consultations as they found it difficult to build rapport with new and unfamiliar clinicians [15]. The technical challenges with telehealth have also been identified in previous studies and further evaluation of mobile video applications to conduct telehealth may inform decisions regarding the use and regulation of these platforms. Remote biometric monitoring has been trial in a number of chronic diseases including dialysis patients. Measurements such as blood pressure, weight, and blood glucose can all be recorded in the patient’s homes which may overcome some of the challenges related to ensuring accuracy when it comes to monitoring vitals and provide clinical data directly to the treating physician [16, 17]. While remote monitoring could ensure accuracy of measurements, it was also mentioned that participants wanted contact with multidisciplinary clinicians. Talks with a nurse or social worker prior to a telehealth visit could ensure that telehealth replicates an in‐person visit as closely as possible.

Our participants had a particularly high level of education, (65% having a university degree). This may have meant that navigating technology was not as challenging for our participants as it would be for some in the wider transplant community. Previous barriers to eMedicine have been identified and include socioeconomic factors, education level, and age [18, 19]. The perceived benefits of telehealth have been investigated in a number of other chronic disease with similar results found to our study. Telehealth not only increases patient awareness of their own condition and health management, but patients also reported feeling safe and empowered [20, 21]. It should be noted that in some disease, settings such as heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease withdrawal of telehealth have been reported due to technical problems and nonadherence [22, 23]. However, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, telehealth appointments seemed to be welcomed by high‐risk patients [24]. While we found that patients felt empowered recording and knowing their self‐monitored measurements, there were some challenges felt by our participants, not only pertaining to the use of technology, a common barrier found by a number of investigations into the use of telehealth [25]. Our participants also felt that task switching, being mentally prepared for appointments, and having a safe space to conduct the telehealth appointment were burdens of telehealth and that their choice to use telehealth in the future depended on the stability of their mental and physical health. However, within the diverse patient group that have had kidney transplants remote monitoring where measurements such as blood pressure and weight that can be sent directly to clinicians may be of benefit to ensure accuracy and alleviate uncertainty, we also noted that patients found task switching, from life/work activities to being in a “health” frame of mind, sometimes difficult and that this was alleviated if the patients felt that had a specific space where they felt relaxed to talk openly during the telehealth consult.

We describe a wide diversity and depth of the perspectives of kidney transplant recipients, who were from metropolitan and nonmetropolitan regions across Australia, on the perceived benefits and risks of telehealth. We achieved data saturation and the findings were sent back to participants to ensure that the analysis reflected the full range of the data. However, there were some potential limitations to this study as non‐English‐speaking participants were not included so the challenges of telehealth may not have been fully explored, and we acknowledge that the online mode may have precluded patients without internet access or as appropriate device from participating.

Our findings have implications to improve access to telehealth and also provide strategies to help support patients in preparing for telehealth consultations with suggestions outlined in Table 3. We suggest that ongoing access to telehealth should be offered as an option to kidney transplant recipients in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas, even after the COVID‐19 pandemic. The multiple benefits on the lives of patients, particularly with regards to reducing the treatment burden and lifestyle disruption with substantially, reduced time spent on transport and waiting in clinic rooms certainly make continuing telehealth a viable option. Where feasible, we suggest that telehealth consultations are provided by a clinician who already has an established rapport with the patient. Clinicians and patients should be trained on how to have a telehealth appointment. Patients in our study highlighted the need for resources (e.g., written information) to enable them to prepare for the appointment, including what measurements they had to take, such as weight, blood pressure and temperature, prior to the telehealth consult. This could address mental preparation while ensuring they are in an environment that is conducive to telehealth appointments. A written summary of what had been said during the telehealth consultation may be helpful, particularly for newly transplanted or patients with complex health issues. We also recommend that a multidisciplinary approach can be adopted in telehealth consultations whereby different specialties are able to consult at the same time with a single patient. Implementing telehealth may require regulatory approval and addressing barriers related to licensing and credentialing, particular in countries including the USA.

Table 3.

Suggestions for practice and policy.

|

Provide ongoing access to telehealth as an option for kidney transplant recipients in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas (including after the COVID‐19 pandemic) |

|

Establish familiarity and rapport between the patient and transplant nephrologist prior to the commencement of telehealth |

|

Provide training and resources to ensure patients have the technical capabilities for telehealth |

|

Optimized telehealth technology in hospitals |

|

Provide training for clinicians on how to conduct a telehealth consult and communicate health information digitally |

|

Ensure technical support/training is available to both hospitals and patients |

|

If telehealth appointment cannot occur due to technical issues, suggest an immediate phone consult and follow‐up sooner with a telehealth appointment |

|

Prepare and provide an information sheet to patients about what to have ready for a telehealth appointment including what measurements to have ready |

|

Provide a written summary of what was said during the telehealth appointment |

|

Multidisciplinary approach to include multiple specialist clinicians on a telehealth call with a single patient for complex cases |

There is growing evidence to suggest that the use of mobile phone applications can help assist with the follow‐up of patients with kidney disease. Future research could evaluate various telehealth interventions such as a mobile application for kidney transplant recipients to enter self‐monitoring measurements, such as blood pressure, and patient‐reported outcome measures to assess side effects and mental well‐being that could be viewed by healthcare teams to support discussion during the telehealth appointments. There is some evidence to suggest that such mobile applications strengthen patient–clinician collaboration during consultations and patients’ health literacy [26, 27]. A trial of telehealth, combined with self‐monitoring and educational interventions, in patients with diabetes found that this improved long‐term glucose control [28]. We suggest that telehealth‐related interventions for follow‐up management of kidney transplantation should be co‐designed with kidney transplant recipients and clinicians [29, 30].

Most of the evidence regarding the use of telehealth has been focused on regional/rural areas across the world [5]. The findings from our study found that patients in metropolitan areas have also identified a range of benefits gained from telehealth appointments. We suggested that further investigation is needed to assess effectiveness, feasibility, and safety of long‐term telehealth use after the COVID‐19 pandemic.

For kidney transplant recipients, telehealth is convenient and minimizes time, financial, and overall treatment burden. Telehealth should ideally be available as an option after the pandemic and be provided by a trusted and familiar nephrologist and supported with resources and strategies to help patients prepare for their appointments.

Authorship

BMH, AB, NSR, CG, AT, and NA participated in the research design, data collection, and data analysis and drafted the manuscript. GW, JK, SC, KB, AV, TC, CH, and PK participated in the research design and data analysis and edited the manuscript.

Funding

A.T. is supported by The University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship. N.S.R. is supported by the NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (ID1190850).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Data S1. Focus group question guide.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who gave up their time to participate in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith AC, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Telemed Telecare 2020; 26: 309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azzi Y, et al. COVID‐19 infection in kidney transplant recipients at the epicenter of pandemics. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1559–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sikka N, et al. Defining emergency telehealth. J Telemed Telecare 2019: 1–4. p. 1357633X19891653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisk M, Livingstone A, Pit SW. Telehealth in the context of COVID‐19: changing perspectives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e19264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohatgi R, Ross MJ, Majoni SW. Telenephrology: current perspectives and future directions. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 1328–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholes‐Robertson NJ, et al. Patients' and caregivers' perspectives on access to kidney replacement therapy in rural communities: systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e037529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrew N, et al. Telehealth model of care for routine follow up of renal transplant recipients in a tertiary centre: A case study. J Telemed Telecare 2020; 26: 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Concepcion BP, Forbes RC. The role of telemedicine in kidney transplantation: opportunities and challenges. Kidney360 2020; 1: 420–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trnka P, White MM, Renton WD, McTaggart SJ, Burke JR, Smith AC. A retrospective review of telehealth services for children referred to a paediatric nephrologist. BMC Nephrol 2015; 16: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lunney M, et al. Impact of telehealth interventions on processes and quality of care for patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 2018; 72: 592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonner A, et al. Evaluating the prevalence and opportunity for technology use in chronic kidney disease patients: a cross‐sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2018; 19: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson JK, et al. eHealth interventions for people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 8: CD012379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang JH, et al. Telehealth in outpatient management of kidney transplant recipients during COVID‐19 pandemic in New York. Clin Transplant 2020; 34(12): e14097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.P. M. o. Australia . "$2 Billion to extend critical health services across Australia," ed, 2020, September 18.

- 15.Quinn LM, Davies MJ, Hadjiconstantinou M. Virtual consultations and the role of technology during the COVID‐19 pandemic for people with type 2 diabetes: The UK perspective. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e21609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnus M, Sikka N, Cherian T, Lew SQ. Satisfaction and improvements in peritoneal dialysis outcomes associated with telehealth. Appl Clin Inform 2017; 8: 214–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker RC, Tong A, Howard K, Palmer SC. Patient expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for chronic diseases: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Med Inform 2019; 124: 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou WY, Prestin A. Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16: e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosner MHLSQCPE, Jarrin J, Patel UD, et al. Perspectives from the kidney health initative on advancing remote monitoring of patient self‐care in RRT. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12: 1900–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonardsen AL, Hardeland C, Helgesen AK, Grondahl VA. Patient experiences with technology enabled care across healthcare settings‐ a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20: 779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahimpour M, Lovell NH, Celler BG, McCormick J. Patients' perceptions of a home telecare system. Int J Med Inform 2008; 77: 486–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz J, Brooks D, Marques A. Home telemonitoring in COPD: a systematic review of methodologies and patients' adherence. Int J Med Inform 2014; 83: 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorst SL, Armitage CJ, Brownsell S, Hawley MS. Home telehealth uptake and continued use among heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med 2014; 48: 323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boehm K, et al. Telemedicine online visits in urology during the COVID‐19 pandemic‐potential, risk factors, and patients' perspective. Eur Urol 2020; 78: 16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 24: 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muscat DM, et al., Supporting patients to be involved in decisions about their health and care: Development of a best practice health literacy App for Australian adults living with Chronic Kidney Disease. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 2021; 32(S1): 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen C, Agerskov H, Bistrup C, Clemensen J. Evaluation of a telehealth solution developed to improve follow‐up after kidney Transplantation. J Clin Nurs 2019; 29: 1053–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwood DA, Blozis SA, Young HM, Nesbitt TS, Quinn CC. Overcoming clinical inertia: A randomized clinical trial of a telehealth remote monitoring intervention using paired glucose testing in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGillicuddy JW, et al. Sustainability of improvements in medication adherence through a mobile health intervention. Prog Transplant 2015; 25: 217–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen C, Agerskov H, Bistrup C, Clemensen J. User involvement in the development of a telehealth solution to improve the kidney transplantation process: A participatory design study. Health Informatics Journal 2020; 26: 1237–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Focus group question guide.