Abstract

Introduction

Little is known about the lifetime prevalence of different indicators of suicidality in the Irish general population; whether suicidality has increased during the COVID‐19 pandemic; and what factors associated with belonging to different points on a continuum of suicidality risk.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of Irish adults (N = 1,032) completed self‐report measures in May 2020 and a follow‐up in August 2020 (n = 715).

Results

Lifetime prevalence rates were 29.5% for suicidal ideation, 12.9% for non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI), and 11.2% for attempted suicide. There were no changes in past two‐week rates of NSSI and attempted suicide during the pandemic. Correlations between the indicators of suicidality supported a progression from ideation to NSSI to attempted suicide. Suicidal ideation alone was associated with being male, unemployed, higher loneliness, and lower religiosity. NSSI (with no co‐occurring attempted suicide) was associated with a history of mental health treatment. Attempted suicide was associated with ethnic minority status, lower education, lower income, PTSD, depression, and history of mental health treatment.

Conclusion

Suicidal ideation, NSSI, and attempted suicide are relatively common phenomena in the general adult Irish population, and each has unique psychosocial correlates. These findings highlight important targets for prevention and intervention efforts.

Keywords: attempted suicide, non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI), risk factors, self‐harm, suicidal ideation, suicide

Self‐injurious thoughts and behaviors describe multiple suicide‐related phenomena including suicidal ideation (thinking about or planning to end one's life), non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI) (deliberately harming oneself without the intent to end one's life), and attempted suicide (deliberately harming oneself with the intent to end one's life) (Nock et al., 2008). These phenomena are proposed to reflect a suicidality continuum with “milder” experiences at the lower end (e.g., thoughts of death) and “extreme” experiences at the upper end (e.g., suicide attempts) (Sveticic & De Leo, 2012). Such a distribution has been identified in a diverse range of samples (Bebbington et al., 2010; Bertolote et al., 2005; Ghazinour et al., 2010; Nock et al., 2008), and various theories of suicide including the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS: Joiner, 2005) and the Integrated Motivational–Volitional Model (IMVM: O’Connor, 2011) recognize this continuum of risk. Specifically, the IPTS states that suicidal ideation transitions to suicidal attempts via an acquired capability to engage in self‐harming behavior, something that often results from engagement in NSSI. Likewise, the IMVM proposes that suicidal ideation and intent can lead to suicidal behavior due to multiple “volitional moderators” including engagement in NSSI.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study found that nearly 800,000 people died from suicide in 2017, making it the 14th leading cause of death (GBD, 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators, 2018). Approximately 30% of the general population report experiencing suicidal thoughts by early adulthood (Evans et al., 2005), and a global review found a 12‐month prevalence of 14% (Biswas et al., 2020). NSSI affects 6%–17% of people in their lifetime (Swannell et al., 2014), and estimates of lifetime attempted suicide range from 3% to 10% (Beautrais et al., 2006; Evan et al., 2005; Nock et al., 2008; Whitlock & Knox, 2007). Variability in these estimates depends on the methods of data collection (i.e., interview or in‐person questionnaire methods produce lower estimates than online survey methods), variable definitions (e.g., some studies measure suicidal ideation as thinking about suicide while others require thinking and planning), and the age of the sample (i.e., higher estimates are typically found in adolescent compared with adult samples).

Numerous studies have explored the potential risk factors for suicidality, and theoretical frameworks such as the Social‐Ecological Suicide Prevention Model (SESPM; Cramer & Kaputsa, 2017) have been developed to provide an integration of general and population‐specific risk and protective factors. This model is divided into a number of levels and those with the strongest support tend to be individual (e.g., male sex (completion) and female sex (attempts), family history of suicidal behavior), and interpersonal/relational levels (e.g., exposure to suicide/contagion, family history of mental illness, social isolation). Other levels in the model include societal (e.g., economic downturn), community (e.g., local suicide epidemic), psychiatric (e.g., mental health diagnoses, substance use/abuse), and psychological (e.g., prior suicide attempt, prior or current non‐suicidal self‐injury). Meta‐analytic studies have also identified different risk factors associated with belonging to different points on the suicidality continuum (Fox et al., 2015; Franklin et al., 2017).

Suicide is a serious public health issue, and concerns have been raised that the COVID‐19 pandemic may have exacerbated the problem (Reger et al., 2020). However, studies comparing the number of suicides in the pre‐pandemic period to the early period of the pandemic have shown a decreased number of suicides in Japan (Ueda et al., 2020), Norway (Qin & Mehlum, 2020), and Peru (Calderon‐Anyosa, & Kaufman, 2020); no change in England (Appleby et al., 2020), Massachusetts in the United States (Faust et al., 2020), and Victoria in Australia (Coroners Court of Victoria, 2020); and an increase in Nepal (Pokhrel et al., 2020). In addition to assessing official death records, it is also important to determine whether changes in suicidality have occurred in the general population during the pandemic. O’Connor et al., (2020) tracked changes in past‐week suicidal ideation, NSSI, and attempted suicide from late March to early May 2020 in a nationally representative sample of British adults. They found no significant change in past‐week NSSI (0.7%–1.4%) or attempted suicide (0.1%–0.7%) but did find a small, significant increase in suicidal ideation (8.2%–9.8%).

This study, based on data collected from a representative, longitudinal survey of the general adult population of the Republic of Ireland during the COVID‐19 pandemic, was conducted to address three objectives. The first was to determine the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation, NSSI, and attempted suicide in the general adult population of Ireland. Additionally, we assessed whether there were significant changes in the 2‐week prevalence of NSSI and attempted suicide during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Based on the findings from O’Connor et al. (2020), we hypothesized that there would be no significant changes in NSSI or attempted suicide.

The second objective was to assess the degree of co‐occurrence between lifetime suicidal ideation, NSSI, and attempted suicide. Based on the predictions of the suicidality continuum (Sveticic & De Leo, 2012), we hypothesized that these indicators of suicidality would be positively associated with one another, and the pattern of associations would be consistent with a progression from suicidal ideation to NSSI to attempted suicide. Thus, we expected to find distinct groups characterized by (i) a history of suicidal ideation but no corresponding history of NSSI or attempted suicide, (ii) a history of NSSI but no corresponding history of attempted suicide, and (iii) a history of attempted suicide.

The third objective was to identify sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and psychiatric correlates of belonging to different points on the suicidality continuum. This objective was approached in a more exploratory manner; however, based on existing theory (Cramer & Kaputsa, 2017) and data (Fox et al., 2015; Franklin et al., 2017), we hypothesized that individual and psychological factors would be most strongly associated with belonging to the less severe end of the suicidality continuum (i.e., those with a history of suicidal ideation but no suicidal behavior), whereas, psychiatric factors would be most strongly associated with belonging to the more extreme end of the suicidal continuum (i.e., those who have attempted suicide).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedures

This study analyzed data collected from the Republic of Ireland arm of the COVID‐19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) study (McBride et al., 2021). At the time of this study, three waves of data had been collected. All data were collected by the survey company Qualtrics, and participants were recruited from traditional, actively managed, double‐opt‐in research panels via email, SMS, or in‐app notifications. Quota sampling methods were used to construct a sample that was nationally representative in terms of sex, age, and geographical distribution, as per data from the 2016 Irish census (Central Statistics Office, 2020). Inclusion criteria required that respondents were aged 18 years or older, resident of the Republic of Ireland, and capable of completing the survey in English. Participants were remunerated for their time, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Ethical approval was granted by the research ethics committees at the University of Sheffield and Ulster University.

Wave 1 (N = 1,041) was collected from March 31st to April 5th, 2020, during the first week of Ireland's initial lockdown, and details of this sample are available elsewhere (Hyland et al., 2020). Wave 2 (N = 1,032) was collected from April 30th to May 19th, 2020, at the end of the lockdown. The Wave 2 sample included 506 participants from Wave 1 (recontact rate = 48.6%) and 526 newly recruited participants. New participants were recruited using the previously described quota sampling method to ensure that the final sample was representative of the general population. Wave 3 (N = 831) was collected from July 16th to August 8th, 2020. Approximately half of these respondents (50.3%, n = 418) had participated at Waves 1 and 2; 14.0% (n = 116) participated at Wave 1 but not Wave 2; and 35.7% (n = 297) participated at Wave 2 but not Wave 1. This study was based on data collected from the entire Wave 2 (N = 1,032) sample and those Wave 2 participants who participated at Wave 3 (n = 715) (recontact rate = 69.3%). Wave 1 data could not be used as data on experiences of suicidality were not collected. The median times for survey completion at Waves 2 and 3 were 24 and 18 min, respectively.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the Wave 2 sample are reported in Table 1. Compared with non‐responders at Wave 3, responders were significantly older (t (1030) = 9.71, p < .001), more likely to be retired (χ2 (3, n = 1032) = 23.48, p < .001), born outside of the Republic of Ireland (χ2 (1, n = 1032) = 5.73, p = .017), and in a committed relationship (χ2 (1, n = 1032) = 5.80, p = .016). Wave 3 responders were also significantly less likely than non‐responders to have a lifetime history of suicidal ideation (χ2 (1, n = 1032) = 12.23, p < .001), self‐harm (χ2 (1, n = 1029) = 10.59, p = .001), and to have attempted suicide (χ2 (1, n = 1030) = 6.19, p = .013). Management of missing data is explained in the data analysis section.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the wave 2 sample (N = 1,032)

| % (or Mean and SD) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 52.1 |

| Male | 47.9 |

| Age | M = 44.86, SD = 15.74 |

| 18–24 | 11.2 |

| 25–34 | 19.4 |

| 35–44 | 20.7 |

| 45–54 | 16.0 |

| 55–64 | 19.7 |

| 65+ | 13.0 |

| Country of birth | |

| Republic of Ireland | 71.6 |

| Grew up in Ireland | |

| Yes | 79.1 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Irish | 74.7 |

| Irish Traveler | 0.4 |

| Other white background | 16.8 |

| African | 1.7 |

| Any other black background | 0.1 |

| Chinese | 0.3 |

| Any other Asian background | 3.6 |

| Mixed background | 2.3 |

| Urbanicity | |

| City dwelling | 20.3 |

| Education level | |

| Post‐secondary level qualification | 71.0 |

| Relationship status | |

| In a committed relationship | 70.7 |

| Living alone | |

| Yes | 12.8 |

| Employment status | |

| Full‐time employed | 42.9 |

| Part‐time employed | 18.1 |

| Unemployed | 22.4 |

| Retired | 16.6 |

| 2019 income | |

| 0–€19,999 | 22.0 |

| €20,000–€29,999 | 20.2 |

| €30,000–€39,999 | 19.9 |

| €40,000–€49,999 | 13.0 |

| €50,000+ | 25.0 |

| Change in income due to COVID‐19 | M = −9.74, SD = 28.61 |

| Financial worries due to COVID‐19 | M = 5.37, SD = 2.92 |

Materials

Suicidality variables (measured at Waves 2 and 3)

Three items were adapted from the 2014 English Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (McManus et al., 2016) to measure suicidal and self‐harm ideation (“There may be times in everyone's life when they become very miserable and depressed and may feel like taking drastic action because of these feelings. Have you ever thought of harming yourself or taking your life, even if you would not really do it?”), NSSI (“Have you ever deliberately harmed yourself in any way but not with the intention of taking your own life?”), and attempted suicide (“Have you ever made an attempt to take your own life?”). Each question was answered on a “Yes” (1) or “No” (0) basis. Participants who indicated a lifetime history of NSSI or attempted suicide were asked they had engaged in these behaviors in the last two weeks, and this was also answered on a “Yes” (1) or “No” (0) basis.

Sociodemographic variables (measured at Wave 2)

Nine sociodemographic variables were assessed including sex (0 = Male, 1 = Female), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65+), country of birth (0 = Republic of Ireland, 1 = Outside of the Republic of Ireland), having grown up in Ireland for the first 16 years of life (0 = Yes, 1 = No), ethnicity (recoded as 0 = Irish, 1 = All other ethnicities), urbanicity (recoded as 0 = Non‐city dwelling, 1 = City dwelling), highest educational achievement (recoded as 0 = Post‐secondary level education, 1 = Secondary level education or less), relationship status (0 = In a committed relationship, 1 = Not in a committed relationship), and living alone (0 = No, 1 = Yes).

Economic variables (measured at Wave 2)

Participants were asked to indicate their current employment status (0 = Full‐time employed, 1 = Part‐time employed, 2 = Unemployed, 3 = Retired), their annual income in 2019 (0 = Less than €20,000, 1 = €20,000–€29,999, 2 = €30,000–€39,999, 3 = €40,000–€49,999, 4 = €50,000 or more), monthly income change due to the pandemic (indicated using a slider scale with −100% and +100% at the two extremes and 0% in the center), and worry about finances due to the pandemic (measured on a ten‐point scale where 1 = “Not worried at all” and 10 = “Extremely worried”).

Psychological variables (measured at Wave 2)

Personality traits: The Big‐Five Inventory (BFI: Rammstedt & John, 2007) measures the traits of Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Each trait was measured by two items using a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), and higher scores reflect higher levels of each personality trait. The BFI has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Rammstedt & John, 2007). Since the BFI uses two items per trait, it was not possible to produce meaningful internal reliability estimates for the scale scores (Eisinga et al., 2013).

Internal locus of control: The three‐item “Internal” subscale of the Locus of Control Scale (LoCS: Sapp & Harrod, 1993) was used (e.g., “My life is determined by my own actions”). The three questions are answered on a seven‐point Likert scale that ranges from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7), and higher scores reflect higher levels of internal locus of control. The internal reliability of the scale scores was satisfactory (α = 0.77).

Identification with others: The Identification with all Humanity Scale (IWAHS: McFarland et al., 2012) is a nine‐item measure where people to respond to three statements with reference to three groups: people in my community, people from Ireland, and all humans everywhere. The three statements were presented to respondents separately for each of the groups, as follows: (1) How much do you identify with (feel a part of, feel love toward, have concern for) …? (2) How much would you say you care (feel upset, want to help) when bad things happen to …? and, (3) When they are in need, how much do you want to help…? The response scale ranged from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (5) and higher scores reflect greater identification with others. The internal reliability of the IWAHS scores in this sample was excellent (α = 0.93).

Intolerance of uncertainty: The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS: Buhr & Dugas, 2002) includes 12 items (e.g., “unexpected events are negative and should be avoided” and “I always want to know what the future has in store for me”) answered on a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “not at all characteristics of me” (1) to “entirely characteristic of me” (5), and higher scores reflect higher levels of intolerance of uncertainty. The IUS scores have been shown to have excellent internal consistency, good test–retest reliability over a 5‐week period, and convergent and divergent validity when assessed with symptom measures of worry, depression, and anxiety (Buhr & Dugas, 2002). The internal reliability of the IUS scores in the current sample was good (α = 0.88).

Death anxiety: The Death Anxiety Inventory (DAI: Tomás‐Sábado et al., 2005) includes 17 items (e.g., “I get upset when I am in a cemetery,” “I find it difficult to accept the idea that it all finishes with death”) based on a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “totally disagree” (1) to “totally agree” (5), and higher scores reflect higher levels of death anxiety. The DAI scores have been shown to have good psychometric properties (Tomás‐Sábado et al., 2005), and the internal reliability of the DAI scores in this sample was excellent (α = 0.92).

Loneliness: The three‐item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004) was designed for use in large‐scale population surveys and asks respondents to indicate how often they feel that they lack companionship, feel left out, and feel isolated from others. Responses are scored on a three‐point scale including “hardly ever” (1), “sometimes” (2), and “often” (3), and higher scores reflect higher levels of loneliness. The internal reliability of the scale score in this sample was good (α = 0.87).

Religious beliefs: Respondents indicated their agreement to eight statements from the Monotheist and Atheist Beliefs Scale (Alsuhibani et al., 2020). Statements included, “God has revealed his plans for us in holy books” and “Moral judgments should be based on respect for humanity rather than religious doctrine.” Response options range from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Atheism oriented statements were reverse scored and summed with monotheist items to produce a summed score with higher scores reflecting a stronger religious belief orientation. The psychometric properties of the scale scores have been previously supported (Alsuhibani et al., 2020), and the internal reliability in the current sample was good (α = 0.81).

Resilience: The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS: Smith et al., 2008) is a six‐item measure of psychological resilience with all items answered on a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), and higher scores reflect higher levels of resilience. The internal reliability of the scale scores in this sample was acceptable (α = 0.69).

Psychiatric variables (measured at Wave 2)

Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ: Cloitre et al., 2018) measures PTSD in accordance with the ICD‐11 guidelines. Six items measure symptoms across the three clusters of re‐experiencing in the here and now, avoidance, and sense of current threat. Participants were instructed to indicate how bothered they have been over the last month in relation to their experiences of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Three items measure functional impairment associated with these symptoms, and all items are answered using a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “Extremely” (4). A symptom was deemed present based on a score of ≥2 (“Moderately”) on the Likert scale (Cloitre et al., 2018), and diagnosis requires one symptom to be present from each cluster plus endorsement of at least one indicator of impairment. The ITQ produces reliable and valid scale scores (Vallières et al., 2018). The internal reliability of the scale scores in this sample was excellent (α = 0.91).

Major depression: The Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9: Kroenke et al., 2001) measures the nine symptoms of major depression, as per the DSM‐5 (APA, 2013). Participants indicate how often they have been bothered by each symptom over the last 2 weeks using a four‐point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “Nearly every day” (3). Scores ≥10 have adequate sensitivity (0.85) and specificity (0.89) in identifying persons who meet diagnostic criteria. The psychometric properties of the PHQ‐9 scores have been widely supported (Manea et al., 2012), and the internal reliability in the current sample was excellent (α = 0.91).

Generalized anxiety disorder: The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐item Scale (GAD‐7: Spitzer et al., 2006) asks participants to indicate how often they have been bothered by each symptom over the last two weeks on a four‐point Likert scale (0 = Not at all, to 3 = Nearly every day). Scores ≥10 have adequate sensitivity (0.89) and specificity (0.82) in identifying persons who meet diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. The GAD‐7 has been shown to produce reliable and valid scores in community studies (Hinz et al., 2017), and the internal reliability in the current sample was excellent (α = 0.94).

Insomnia disorder: The Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI: Espie et al., 2014) is an eight‐item measure of different types of sleep problems including sleep continuity, sleep satisfaction, severity of sleep problems, and daytime functioning. The SCI was designed to reflect the DSM‐5 criteria for Insomnia Disorder. Each item is scored on a four‐point Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 to 32. Higher scores reflect better sleep quality, and scores ≤16 reflect probable diagnosis of insomnia disorder (Espie et al., 2014). The SCI scale has been shown to produce reliable and valid scores (Espie et al., 2018), and the internal reliability in the current sample was good (α = 0.88).

History of mental health treatment: Participants were asked, “Mental health difficulties are very common. It will help us to know if you are currently, or have in the past, received treatment (for example, medication or talking therapies) for any mental health problems from a mental health service provider such as a psychiatrist, general practitioner, psychologist, or counselor/psychotherapist.” Respondents answered “Yes” (1) or “No” (0).

Data analysis

Changes in the two‐week prevalence of NSSI and attempted suicide from Wave 2 to Wave 3 were assessed using structural equation modeling (SEM). A SEM approach was used so that missing data were managed using full information robust maximum likelihood estimation which is recognized as the optimal method for handling missing data (Li & Stuart, 2019; Schafer & Graham, 2002). This approach involves two steps and was performed separately for NSSI and attempted suicide. First, a “null model” was specified where the two proportions (e.g., attempted suicide at Waves 2 and 3) were constrained to be equal. Next, an “alternative model” was specified where the two proportions were freely estimated. These models differ by one degree of freedom so improvement in model fit can be tested using a log‐likelihood ratio test (LRT), which is distributed as a χ2 . Thus, the models can be statistically compared using an LRT‐χ2 difference test. These analyses were performed in Mplus 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018).

Associations between lifetime suicidal ideation, NSSI, and attempted suicide were assessed using Pearson chi‐square (χ2 ) tests with a McNemar correction for dependent proportions. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are reported to quantify the magnitude of the associations.

Hierarchical binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify which sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and psychiatric variables were associated with the different indicators of suicidality. Separate models were estimated for the three criterion variables of (a) lifetime history of suicidal ideation with no corresponding history of NSSI or attempted suicide, (b) lifetime history of NSSI with no corresponding history of attempted suicide, and (c) lifetime history of attempted suicide. The predictor variables were the same in all models and were entered in four blocks. The nine sociodemographic variables were entered in block 1, the four economic variables were entered in block 2, the twelve psychological variables were entered in block 3, and the five psychiatric variables were entered in block 4. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated to quantify the strength of the associations between the predictor and criterion variables. These analyses were performed in SPSS version 26.

There were minimal missing data present at Wave 2, with three participants choosing not to answer the question relating to NSSI, and two participants choosing not to answer the question relating to attempted suicide. These data were managed using listwise deletion.

RESULTS

Prevalence and change over time

The lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation was 29.5% (95% CI = 26.7%, 32.2%), NSSI was 12.9% (95% CI = 10.9%, 15.0%), and attempted suicide was 11.2% (95% CI = 9.3%, 13.1%). There was no statistically significant change in the 2‐week prevalence of NSSI from Wave 2 (1.1%, 95% CI = 0.4%, 1.7%) to Wave 3 (1.0%, 95% CI = 0.2%, 1.7%) (χ2 (1) = 0.05, p = .823). Additionally, there was no statistically significant change in the two‐week prevalence of attempted suicide from Wave 2 (1.0%, 95% CI = 0.4%, 1.6%) to Wave 3 (1.4%, 95% CI = 0.5%, 2.2%) (χ2 (1) = 0.85, p = .356).

Co‐occurrence between the indicators of suicidality

Suicidal ideation was significantly associated with NSSI (χ2 (1, n = 1029) = 168.37, McNemar test p < .001, OR = 11.87, 95% CI = 7.68, 18.36). Specifically, 33.9% of those who reported ideation also reported NSSI, while only 4.1% of those with a history of NSSI did not have a history of ideation. Suicidal ideation was also significantly associated with attempted suicide (χ2 (1, n = 1030) = 164.11, McNemar test p < .001, OR = 14.10, 95% CI = 8.65, 23.01). Here, 30.6% of those who reported ideation also reported a history of attempted suicide, while only 3.0% of those who attempted suicide did not have a corresponding history of ideation. Finally, NSSI and attempted suicide were significantly associated (χ2 (1, n = 1027) = 127.70, McNemar test p < .001; OR = 9.01, 95% CI = 5.85, 13.90). In this case, 40.2% of those with a history of NSSI also had a history of attempted suicide, while only 6.9% of those who attempted suicide did not have a history of NSSI.

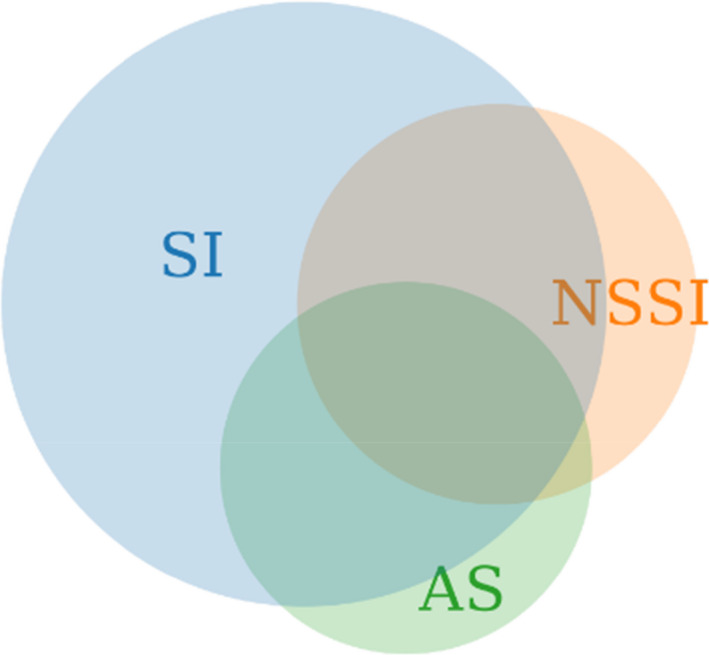

The association between the indicators of suicidality is depicted in Figure 1. There were 153 people (14.8% of the full sample) with a history of suicidal ideation but no corresponding history of NSSI or attempted suicide, and 79 people (7.7% of the full sample) with a history of NSSI but no corresponding history of attempted suicide.

FIGURE 1.

Venn diagram depicting the overlap between history of suicidal ideation (SI), non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI), and attempted suicide (AS). Note: 29.5% (n = 304) reported SI and of those, 33.9% (n = 103) also reported NSSI and 30.6% (n = 93) reported AS. 12.9% (n = 133) reported NSSI and of those, 40.2% (n = 53) reported AS; 11.2% (n = 115) reported AS and of those; 4.4% (n = 45) reported a history of SI, NSSI, and AS

Correlates of suicidal ideation

Table 2 displays the results of the regression model of suicidal ideation (with no corresponding history of NSSI or attempted suicide). In the first block (χ2 (13) = 25.77, p = .018), suicidal ideation was associated with being male and being in multiple age categories under the age 65. The entry of the economic variables in the second block did not significantly contribute to the model (χ2 (9) = 16.83, p = .051), and being male and being unemployed were associated with suicidal ideation. The psychological variables were entered in the third block (χ2 (12) = 32.50, p = .001), and male sex, unemployment status, higher levels of loneliness, and lower levels of religious belief were associated with suicidal ideation. The psychiatric variables were entered in the fourth block and did not significantly contribute to the model (χ2 (5) = 5.26, p = .385).

TABLE 2.

Associations between sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and psychiatric variables and suicide/self‐harm ideation only

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |||||

| Sex (Male) | 1.92 | 1.33 | 2.77 | 2.012 | 1.367 | 2.961 | 2.074 | 1.382 | 3.113 | 2.055 | 1.364 | 3.098 |

| Age 18–24 | 2.29 | 0.94 | 5.57 | 1.327 | 0.452 | 3.897 | 0.754 | 0.241 | 2.364 | 0.700 | 0.221 | 2.216 |

| 25–34 | 3.48 | 1.60 | 7.59 | 2.414 | 0.901 | 6.472 | 1.475 | 0.522 | 4.167 | 1.417 | 0.500 | 4.016 |

| 35–44 | 1.97 | 0.901 | 4.28 | 1.367 | 0.513 | 3.643 | 0.834 | 0.299 | 2.324 | 0.778 | 0.278 | 2.173 |

| 45–54 | 2.70 | 1.26 | 5.80 | 1.834 | 0.704 | 4.779 | 1.372 | 0.512 | 3.675 | 1.307 | 0.488 | 3.502 |

| 55–64 | 2.48 | 1.17 | 5.28 | 1.892 | 0.790 | 4.530 | 1.517 | 0.619 | 3.721 | 1.507 | 0.615 | 3.694 |

| Nationality (Non‐Irish) | 0.83 | 0.39 | 1.73 | 0.811 | 0.384 | 1.714 | 0.828 | 0.384 | 1.786 | 0.822 | 0.381 | 1.776 |

| Grow up in Ireland (No) | 1.55 | 0.76 | 3.16 | 1.543 | 0.753 | 3.164 | 1.345 | 0.635 | 2.846 | 1.328 | 0.626 | 2.816 |

| Ethnicity (Minority) | 0.94 | 0.44 | 1.99 | 1.017 | 0.472 | 2.191 | 1.175 | 0.536 | 2.579 | 1.223 | 0.554 | 2.701 |

| Residence in a city (Yes) | 0.89 | 0.56 | 1.41 | 0.924 | 0.578 | 1.478 | 0.997 | 0.613 | 1.620 | 1.011 | 0.620 | 1.648 |

| Education (No university) | 1.07 | 0.71 | 1.61 | 0.977 | 0.635 | 1.503 | 1.045 | 0.670 | 1.631 | 1.040 | 0.665 | 1.628 |

| Relationship (Not in a relationship) | 1.41 | 0.91 | 2.18 | 1.377 | 0.872 | 2.175 | 1.118 | .690 | 1.809 | 1.113 | 0.685 | 1.806 |

| Living alone (Yes) | .83 | 0.45 | 1.54 | 0.839 | 0.448 | 1.571 | 0.811 | .424 | 1.551 | 0.779 | 0.405 | 1.498 |

| Part‐time employed | 1.105 | 0.631 | 1.938 | 1.080 | .608 | 1.917 | 1.074 | 0.603 | 1.914 | |||

| Unemployed | 1.844 | 1.126 | 3.019 | 1.832 | 1.105 | 3.038 | 1.804 | 1.083 | 3.006 | |||

| Retired | 0.700 | 0.309 | 1.588 | 0.641 | 0.276 | 1.485 | 0.635 | 0.275 | 1.467 | |||

| Income < €20,000 | 0.822 | 0.457 | 1.481 | 0.793 | 0.433 | 1.452 | 0.782 | 0.426 | 1.434 | |||

| €20,000–€29,999 | 0.938 | 0.548 | 1.605 | 0.952 | 0.549 | 1.651 | 0.936 | 0.539 | 1.626 | |||

| €30,000–€39,999 | 0.779 | 0.446 | 1.362 | 0.828 | 0.467 | 1.468 | 0.816 | 0.459 | 1.450 | |||

| €40,000–€49,999 | 0.527 | 0.268 | 1.033 | 0.554 | 0.278 | 1.102 | 0.545 | 0.273 | 1.089 | |||

| Income change due to COVID‐19 | 0.994 | 0.987 | 1.000 | 0.995 | 0.988 | 1.002 | 0.995 | 0.988 | 1.002 | |||

| Financial worries due to COVID‐19 | 0.958 | 0.895 | 1.025 | 0.932 | 0.866 | 1.002 | 0.935 | 0.868 | 1.008 | |||

| Openness | 1.008 | 0.902 | 1.125 | 1.014 | 0.907 | 1.133 | ||||||

| Conscientiousness | 1.005 | 0.895 | 1.127 | 1.011 | 0.900 | 1.136 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.945 | 0.852 | 1.049 | .942 | 0.848 | 1.046 | ||||||

| Agreeableness | 0.953 | 0.845 | 1.075 | .957 | 0.848 | 1.081 | ||||||

| Neuroticism | 1.087 | 0.976 | 1.210 | 1.090 | 0.975 | 1.218 | ||||||

| Internal locus of control | 0.999 | 0.954 | 1.046 | 1.000 | 0.955 | 1.048 | ||||||

| Identification with others | 1.008 | 0.982 | 1.035 | 1.009 | 0.982 | 1.036 | ||||||

| Intolerance of uncertainty | 1.002 | 0.985 | 1.020 | 1.003 | 0.985 | 1.021 | ||||||

| Death Anxiety | 0.995 | 0.980 | 1.011 | 0.996 | 0.981 | 1.012 | ||||||

| Loneliness | 1.146 | 1.022 | 1.284 | 1.128 | 1.00 | 1.27 | ||||||

| Religious beliefs | 0.960 | 0.932 | 0.990 | 0.958 | 0.930 | 0.988 | ||||||

| Resilience | 0.972 | 0.923 | 1.024 | 0.973 | 0.924 | 1.025 | ||||||

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder (Yes) | 1.286 | 0.781 | 2.117 | |||||||||

| Major depressive disorder (Yes) | 1.107 | 0.617 | 1.989 | |||||||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder (Yes) | 0.617 | 0.327 | 1.165 | |||||||||

| Insomnia disorder (Yes) | 1.067 | 0.688 | 1.656 | |||||||||

| History of mental health treatment (Yes) | 1.401 | 0.920 | 2.131 | |||||||||

N = 1,028; AOR = adjusted odds ratios; 95% CIs = 95% confidence intervals; statistically significant associations (p < .05) in bold.

The full model was statistically significant (χ2 (39) = 80.36, p = .001) and correctly classified 85.0% of respondents. Four variables were significantly associated with suicidal ideation: being male (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.36, 3.10), being unemployed (AOR = 1.80, 95% CI = 1.08, 3.10), higher levels of loneliness (AOR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.27), and lower levels of religious beliefs (AOR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.93, 0.99).

Correlates of NSSI

Table 3 presents the results of the regression model of NSSI (with no corresponding history of attempted suicide). In the first block (χ2 (13) = 68.38, p < .001), NSSI was associated with being female, being aged 18–24, 25–34, and 35–44, and not being in a committed relationship. The economic variables did not significantly contribute to the model (χ2 (9) = 9.21, p = .418), and only female sex was significantly associated with NSSI. The psychological variables significantly contributed to the model (χ2 (12) = 24.84, p = .016), and female sex and higher levels of loneliness were associated with NSSI. The psychiatric variables did not significantly contribute to the model (χ2 (5) = 5.26, p = .385).

TABLE 3.

Associations between sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and psychiatric variables and non‐suicidal self‐injurious behavior.

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |||||

| Sex (Male) | .51 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 0.516 | 0.296 | 0.901 | 0.549 | 0.306 | 0.984 | 0.618 | 0.335 | 1.138 |

| Age 18–24 | 18.09 | 2.29 | 143.24 | 6.299 | 0.487 | 81.446 | 3.907 | 0.281 | 54.350 | 3.309 | 0.250 | 43.709 |

| 25–34 | 16.08 | 2.10 | 123.38 | 5.967 | 0.475 | 74.938 | 4.025 | 0.300 | 54.017 | 3.513 | 0.278 | 44.432 |

| 35–44 | 15.30 | 2.00 | 117.32 | 5.888 | 0.469 | 73.897 | 4.247 | 0.320 | 56.304 | 3.345 | 0.269 | 41.540 |

| 45–54 | 6.89 | 0.84 | 56.26 | 2.803 | 0.217 | 36.155 | 2.290 | 0.170 | 30.902 | 1.819 | 0.144 | 23.038 |

| 55–64 | 1.77 | 0.18 | 17.39 | 0.829 | 0.060 | 11.438 | 0.844 | 0.059 | 12.027 | 0.663 | 0.049 | 9.008 |

| Nationality (Non‐Irish) | 2.11 | 0.89 | 4.96 | 2.052 | 0.852 | 4.943 | 2.277 | 0.928 | 5.584 | 2.263 | 0.880 | 5.817 |

| Grow up in Ireland (No) | 0.53 | 0.21 | 1.31 | 0.483 | 0.192 | 1.214 | 0.394 | 0.152 | 1.018 | 0.402 | 0.151 | 1.074 |

| Ethnicity (Minority) | 0.60 | 0.23 | 1.56 | 0.620 | 0.235 | 1.636 | 0.744 | 0.281 | 1.971 | 0.937 | 0.334 | 2.631 |

| Residence in a city (Yes) | 1.41 | 0.80 | 2.49 | 1.494 | 0.833 | 2.678 | 1.539 | 0.838 | 2.825 | 1.492 | 0.797 | 2.793 |

| Education (No university) | 0.93 | 0.52 | 1.68 | 0.806 | 0.434 | 1.499 | 0.720 | 0.375 | 1.382 | 0.766 | 0.392 | 1.496 |

| Relationship (Not in a relationship) | 1.87 | 1.11 | 3.16 | 1.653 | 0.966 | 2.826 | 1.287 | 0.725 | 2.285 | 1.335 | 0.733 | 2.432 |

| Living alone (Yes) | 0.96 | 0.41 | 2.25 | 0.939 | 0.394 | 2.239 | 1.005 | 0.404 | 2.499 | 0.899 | 0.348 | 2.325 |

| Part‐time employed | 0.716 | 0.336 | 1.527 | 0.769 | 0.352 | 1.680 | 0.862 | 0.387 | 1.919 | |||

| Unemployed | 1.333 | 0.709 | 2.506 | 1.577 | 0.820 | 3.034 | 1.542 | 0.789 | 3.011 | |||

| Retired | 0.239 | 0.019 | 2.987 | 0.259 | 0.020 | 3.335 | 0.218 | 0.018 | 2.635 | |||

| Income < €20,000 | 1.888 | 0.799 | 4.458 | 1.775 | 0.736 | 4.281 | 1.614 | 0.663 | 3.927 | |||

| €20,000–€29,999 | 1.989 | 0.880 | 4.497 | 2.049 | 0.883 | 4.757 | 1.915 | 0.812 | 4.518 | |||

| €30,000–€39,999 | 1.382 | 0.600 | 3.182 | 1.357 | 0.574 | 3.210 | 1.342 | 0.553 | 3.254 | |||

| €40,000–€49,999 | 1.262 | 0.474 | 3.366 | 1.467 | 0.535 | 4.019 | 1.493 | 0.525 | 4.247 | |||

| Income change due to COVID‐19 | 0.998 | 0.990 | 1.007 | 1.000 | 0.991 | 1.009 | 1.001 | 0.991 | 1.010 | |||

| Financial worries due to COVID‐19 | 0.958 | 0.876 | 1.048 | 0.925 | 0.839 | 1.019 | 0.905 | 0.816 | 1.004 | |||

| Openness | 0.917 | 0.778 | 1.081 | 0.907 | 0.767 | 1.073 | ||||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.838 | 0.715 | .982 | 0.854 | 0.727 | 1.003 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 1.006 | 0.871 | 1.161 | 0.985 | 0.851 | 1.141 | ||||||

| Agreeableness | 0.938 | 0.794 | 1.107 | 0.958 | 0.808 | 1.136 | ||||||

| Neuroticism | 1.018 | 0.878 | 1.180 | 0.937 | 0.801 | 1.097 | ||||||

| Internal locus of control | 0.974 | 0.909 | 1.042 | 0.976 | 0.909 | 1.047 | ||||||

| Identification with others | 1.029 | 0.991 | 1.069 | 1.031 | 0.992 | 1.072 | ||||||

| Intolerance of uncertainty | 0.997 | 0.973 | 1.021 | 0.991 | 0.966 | 1.017 | ||||||

| Death Anxiety | 0.998 | 0.977 | 1.019 | 1.001 | 0.980 | 1.023 | ||||||

| Loneliness | 1.272 | 1.084 | 1.493 | 1.141 | 0.961 | 1.354 | ||||||

| Religious beliefs | 0.984 | 0.941 | 1.029 | 0.991 | 0.947 | 1.037 | ||||||

| Resilience | 0.963 | 0.895 | 1.036 | 0.973 | 0.904 | 1.048 | ||||||

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder (Yes) | 0.696 | 0.368 | 1.317 | |||||||||

| Major depressive disorder (Yes) | 1.868 | 0.880 | 3.967 | |||||||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder (Yes) | 1.256 | 0.591 | 2.669 | |||||||||

| Insomnia disorder (Yes) | 1.569 | 0.864 | 2.850 | |||||||||

| History of mental health treatment (Yes) | 2.240 | 1.268 | 3.958 | |||||||||

N = 1024; AOR = adjusted odds ratios; 95% CIs = 95% confidence intervals; statistically significant associations (p < .05) in bold.

The model as a whole was statistically significant (χ2 (39) = 125.22, p < .001) and correctly classified 92.6% of respondents. In the final model, having received treatment for a mental health problem was the only variable significantly associated with NSSI (AOR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.27, 3.96).

Correlates of attempted suicide

The results of the regression model of attempted suicide are presented in Table 4. The demographic variables significantly contributed to the model (χ2 (13) = 38.70, p <.001), and attempted suicide was associated with being aged 18–24, 25–34, and 35–44, not having a post‐secondary level education, and living alone. The economic variables significantly contributed to the model (χ2 (9) = 21.34, p = .011), and attempted suicide was associated with being in each age group under the age of 65, not having a post‐secondary level education, living alone, earning less than €20,000 per year, and greater financial worries due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The psychological variables significantly contributed to the model (χ2 (12) = 38.82, p < .001), and attempted suicide was associated with being aged 35–44, not having a post‐secondary level education, living alone, being in multiple lower income categories, greater financial worries due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, higher levels of trait Neuroticism, and higher levels of loneliness. The psychiatric variables also significantly contributed to the model (χ2 (5) = 71.88, p < .001).

TABLE 4.

Associations between sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and psychiatric variables and attempted suicide.

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |||||

| Sex (Male) | 1.21 | .80 | 1.83 | 1.36 | .89 | 2.09 | 1.36 | 0.86 | 2.15 | 1.49 | 0.90 | 2.45 |

| Age 18–24 | 3.54 | 1.26 | 9.94 | 5.76 | 1.63 | 20.39 | 3.30 | 0.86 | 12.60 | 1.93 | 0.47 | 7.92 |

| 25–34 | 4.37 | 1.66 | 11.48 | 5.88 | 1.76 | 19.62 | 3.15 | 0.88 | 11.22 | 1.94 | 0.52 | 7.32 |

| 35–44 | 4.25 | 1.67 | 10.78 | 6.32 | 1.95 | 20.50 | 3.93 | 1.15 | 13.39 | 2.43 | 0.68 | 8.64 |

| 45–54 | 2.44 | 0.92 | 6.52 | 3.72 | 1.15 | 12.06 | 2.66 | 0.78 | 9.03 | 2.06 | 0.58 | 7.27 |

| 55–64 | 2.29 | 0.89 | 5.94 | 3.13 | 1.09 | 8.94 | 2.32 | 0.78 | 6.92 | 2.01 | 0.65 | 6.20 |

| Nationality (Non‐Irish) | 0.56 | 0.23 | 1.34 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 1.37 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 1.43 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 1.19 |

| Grow up in Ireland (No) | 1.17 | 0.52 | 2.66 | 1.22 | 0.53 | 2.82 | 1.12 | 0.46 | 2.73 | 1.31 | 0.49 | 3.47 |

| Ethnicity (Minority) | 1.76 | 0.77 | 4.03 | 1.56 | 0.67 | 3.67 | 1.81 | 0.74 | 4.38 | 2.72 | 1.06 | 6.99 |

| Residence in a city (Yes) | 0.84 | 0.50 | 1.41 | 0.79 | 0.46 | 1.34 | .84 | 0.48 | 1.46 | 0.81 | 0.45 | 1.46 |

| Education (No university) | 1.84 | 1.19 | 2.86 | 1.83 | 1.15 | 2.92 | 1.90 | 1.16 | 3.09 | 1.99 | 1.18 | 3.35 |

| Relationship (Not in a relationship) | 1.48 | 0.92 | 2.39 | 1.35 | 0.83 | 2.20 | 1.11 | 0.65 | 1.87 | 1.28 | 0.72 | 2.25 |

| Living alone (Yes) | 2.21 | 1.21 | 4.03 | 2.09 | 1.14 | 3.86 | 1.92 | 1.00 | 3.68 | 1.54 | 0.76 | 3.12 |

| Part‐time employed | 1.04 | 0.56 | 1.91 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 1.89 | 1.15 | 0.59 | 2.26 | |||

| Unemployed | 0.79 | 0.44 | 1.41 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 1.36 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 1.26 | |||

| Retired | 1.98 | 0.82 | 4.81 | 1.76 | 0.70 | 4.42 | 1.84 | 0.70 | 4.86 | |||

| Income < €20,000 | 2.24 | 1.09 | 4.60 | 2.21 | 1.05 | 4.67 | 2.18 | 1.00 | 4.74 | |||

| €20,000–€29,999 | 1.92 | 0.95 | 3.86 | 1.87 | 0.91 | 3.83 | 1.80 | 0.85 | 3.83 | |||

| €30,000–€39,999 | 1.93 | 0.97 | 3.84 | 2.12 | 1.04 | 4.30 | 2.40 | 1.13 | 5.10 | |||

| €40,000–€49,999 | 1.38 | 0.61 | 3.14 | 1.59 | 0.68 | 3.71 | 1.68 | 0.68 | 4.13 | |||

| Income change due to COVID‐19 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | |||

| Financial worries due to COVID‐19 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.18 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.18 | |||

| Openness | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.20 | ||||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Extraversion | 0.95 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 1.03 | ||||||

| Agreeableness | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.15 | ||||||

| Neuroticism | 1.19 | 1.05 | 1.35 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 1.25 | ||||||

| Internal locus of control | 0.99 | 0.93 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 1.05 | ||||||

| Identification with others | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 | ||||||

| Intolerance of uncertainty | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 | ||||||

| Death Anxiety | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Loneliness | 1.18 | 1.03 | 1.34 | 0.99 | 0.85 | 1.14 | ||||||

| Religious beliefs | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | ||||||

| Resilience | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.07 | ||||||

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder (Yes) | 1.77 | 1.01 | 3.10 | |||||||||

| Major depressive disorder (Yes) | 3.53 | 1.84 | 6.75 | |||||||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder (Yes) | 1.05 | 0.55 | 1.99 | |||||||||

| Insomnia disorder (Yes) | 0.90 | 0.53 | 1.54 | |||||||||

| History of mental health treatment (Yes) | 3.52 | 2.16 | 5.75 | |||||||||

N = 1,026; AOR = adjusted odds ratios; 95% CIs = 95% confidence intervals; statistically significant associations (p < .05) in bold.

The full model was statistically significant (χ2 (39) = 170.73, p < .001) and correctly classified 89.5% of respondents. Six variables were significantly associated with attempted suicide: ethnic minority status (AOR = 2.72, 95% CI = 1.06, 6.99), not having a post‐secondary education (AOR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.18, 3.35), earning less than €20,000 a year (AOR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.00, 4.74), earning between €30,000 and €39,999 a year (AOR = 2.40, 95% CI = 1.13, 5.10), meeting the diagnostic requirements for PTSD (AOR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.01, 3.10), screening positive for major depression (AOR = 3.53, 95% CI = 1.84, 6.75), and having received treatment for a mental health problem (AOR = 3.52, 95% CI = 2.16, 5.75).

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to understand the occurrence, co‐occurrence, and correlates of suicidality in the general adult population of Ireland. Furthermore, this study was conducted to determine whether different indicators of suicidal behavior had increased in frequency during the initial months of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our findings regarding the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation (29.5%) and NSSI (12.9%) are consistent with international data (Evans et al., 2005; Swannell et al., 2014). The figure for attempted suicide (11.2%) is higher than studies which used in‐person questionnaire or interview methods (e.g., Nock et al., 2008), but it is in‐line with studies that employed online survey methods (e.g., Whitlock & Knox, 2007). Considering that people are more comfortable disclosing personally sensitive information using online methods (Pickard et al., 2018), we feel confident that these findings are a reasonable estimation of the true rates of suicidality in the Irish population.

In Ireland, suicide rates have declined from 11.6 per 100,000 people in 2005 to 8.6 per 100,000 people in 2019 (Health Service Executive, 2020), although the 2019 figures do not include late registered deaths and so must be interpreted with caution. As of 2017, the rate of suicide in Ireland was below the average of 11.2 per 100,000 from 36 OECD countries (OECD, 2019). Despite these encouraging trends, our findings show that suicidality remains a major public health issue and the need for accessible and adequate mental health services to continue to respond to the problem of suicide can hardly be overstated.

While concerns had been raised that suicides might increase in frequency because of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Reger et al., 2020), cause of death reports show a general trend of decreasing (Calderon‐Anyosa, & Kaufman, 2020; Qin & Mehlum, 2020; Ueda et al., 2020) or stable (Appleby et al., 2020; Coroners Court of Victoria, 2020; Faust et al., 2020) numbers of suicides in the initial months of the pandemic compared with the months prior to the outbreak of COVID‐19. Notably, however, a higher number of suicides have been reported in Nepal in the initial months of the pandemic (Pokhrel et al., 2020). Consistent with our first study hypothesis, we found a low rate of NSSI and attempted suicide in the past two weeks at both assessments, and no significant change in NSSI or attempted suicide between May and August 2020. These results mirror those reported by O’Connor et al., (2020) in a nationally representative sample of British adults followed from late March to early May 2020. Unlike O’Connor who found a small but significant increase in suicidal ideation, we did not measure the two‐week prevalence of suicidal ideation so we cannot say anything about changes in this indicator of suicidality. Nevertheless, the majority of the available data to date suggest that the COVID‐19 pandemic has not led to an increase in suicidal behaviors. Further longitudinal research will be required to know whether this remains the case over the coming months and years.

Consistent with our second hypothesis, we found strong associations between lifetime history of suicidal ideation, NSSI, and attempted suicide, and in a manner that was in line with the predictions of the suicidality continuum (Sveticic & De Leo, 2012). We found that the majority (65%–70%) of people with a history of suicidal ideation had not engaged in NSSI or attempted suicide, but these suicidal behaviors rarely occurred without corresponding suicidal ideation. Specifically, 96% of people who engaged in NSSI, and 97% of people who attempted suicide had a history of suicidal ideation. Furthermore, while the majority (60%) of people with a history of NSSI had not attempted suicide, 93% of people who attempted suicide had a history of NSSI. Our findings, therefore, are consistent with and complement those from studies that have investigated the association between these phenomena over time (Mars et al., 2019; Neeleman et al., 2004; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Based on these data and recognizing that (a) suicidal ideation is one of the strongest predictors of psychiatric hospitalization and death by suicide (Klonsky et al., 2013), and (b) that individuals who present to hospital with suicidal ideation are at risk of repeat presentation and future self‐harm (Griffin, Kavalidou, Bonner, O’Hagan, & Corcoran 2020), early interventions that target and treat suicidal ideation are likely to be beneficial in preventing suicide‐related behaviors. Existing psychotherapies such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Geddes et al., 2013) and Cognitive‐Behavior Therapy (Tarrier et al., 2008) have been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal thoughts.

We identified multiple variables associated with belonging to different points on the suicidality continuum. In the case of suicidal ideation alone, men were twice as likely as women, and those who were unemployed with nearly 80% more likely than those in full‐time employment to have suicidal thoughts. Higher levels of loneliness and lower levels of religious beliefs were also associated with suicidal ideation. Together these findings suggest that disconnection—from other human beings or from a purpose in life—is associated with having thoughts about suicide. Psychosocial interventions aimed at reducing suicidal ideation should, therefore, help people to find a sense of meaning in life through greater connection with other people and with their wider society. The mental health benefits of interpersonal connection and commitment to long‐term pursuits are well‐established (Bryant et al., 2017; Vaillant, 2015; Windsor et al., 2015).

With respect to those who had a history of NSSI with no corresponding history of attempted suicide, we initially found a strong association with being female, being younger, and not being in a committed relationship. However, when all demographic, economic, and psychological variables were considered, only female sex and higher levels of loneliness were associated with NSSI. With the inclusion of the psychiatric variables, the effects for sex and loneliness disappeared and NSSI was only associated with having a history of being treated for a mental health disorder. Those who had been treated for a mental health problem were over twice as likely as those with no such history to have engaged in NSSI. These findings suggest that while demographic and psychological factors are important in understanding NSSI, their effects are subsumed by a history of mental illness.

Attempted suicide was associated with several demographic, economic, and psychiatric variables. Individuals of a non‐Irish ethnicity were approximately three times more likely than those of Irish ethnicity to have attempted suicide; those who did not attend university were nearly twice as likely as those who did to have attempted suicide; and those with an annual income level less than €50,000 a year were upwards of two‐and‐a‐half times as likely than those earning over €50,000 a year to have attempted suicide. While there are likely to be a myriad of reasons for why each of these variables were associated with a history of attempted suicide, when considered together it suggests that attempted suicide is more likely in the context of social defeat. This is consistent with O’Connor’s (2011) Integrated Motivational‐Volitional Model of suicide which suggests that experiences of defeat and humiliation can lead to feelings of entrapment, which can subsequently lead to suicidal intent and behavior. Social defeat paradigms have been advanced to understand schizophrenia (Selten et al., 2016) and depression (Becker et al., 2008), and our findings suggest that social defeat may be relevant for understanding suicide.

Attempted suicide was also associated with several mental health problems. Those who met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD were nearly twice as likely to have attempted suicide compared with those who did not, while those who screened positive for major depression were three‐and‐a‐half times more likely than those that did not to have attempted suicide. Additionally, those with a history of receiving treatment for a mental health disorder were also three‐and‐a‐half times more likely than those with no such history to have attempted suicide. These findings are consistent with Franklin et al., and’s (2017) meta‐analysis of risk factors for suicide and demonstrate that if the problem of suicide is to be addressed, effective mental health interventions must be made available to all persons in society who are suffering from mental illness.

These findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, the non‐probability sampling strategy means that these findings cannot be generalized to the entire Irish population. Our sampling frame did not include people in extremely vulnerable situations such as those who were homeless, living in direct provision, hospitalized, or imprisoned at the time of the survey. As these populations are at greater risk of suicidality, our estimates may be considered to represent the lower bound estimate of the true population rates. Second, we used a single‐item measures for each indicator of suicidality. While these items were adapted from an existing epidemiological survey and have been used in studies similar to our own (O’Connor et al., 2020), multi‐item measures might have been preferable to increase confidence in the reliability of the measurements (Loo, 2002). Third, while we were able to include a large number of risk factors, some well‐established risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors were not measured including trauma history and lack of social support (Franklin et al., 2017). Relatedly, we did not focus on distinguishing between motivational and volitional risk factors, which is a key component of prominent theories of suicide (e.g., the IPTS and IMVM). Finally, the longitudinal aspect of the study only covered the first three‐to‐four months of the pandemic.

CONCLUSION

Nearly one‐in‐three Irish adults have experienced suicidal ideation at some point in their life, approximately one‐in‐eight have engaged in NSSI, and about one‐in‐ten have made an attempt to take their own life. Although the number of suicides in Ireland has decreased in recent years, suicide remains a serious public health issue. Our findings suggest, however, that the COVID‐19 pandemic may not be an exacerbating factor in suicidal behavior; however, continued monitoring of the population over an extended period of time will be necessary. Our findings are aligned with the proposed suicidality continuum from ideation to behavior, and we have identified multiple risk factors associated with belonging to different points on this continuum. Our results suggest that disconnection from other people and from the world is associated with increased risk of belonging to the lower end of the suicidality continuum whereas social defeat and serious mental illness is associated with belonging to the higher end of the suicidality continuum. Addressing the problem of suicide in society will require continued improvements in interpersonal connections, social cohesion, meaning in life, social mobility, economic success, and increased access to effective mental health services. These findings can help with ongoing prevention and intervention efforts related to suicide (Stone et al., 2017; Wasserman & Drurkee, 2009; WHO, 2018; Zalsman et al., 2016).

Hyland, P. , Rochford, S. , Munnelly, A. , Dodd, P. , Fox, R. , Vallières, F. , McBride, O. , Shevlin, M. , Bentall, R. P. , Butter, S. , Karatzias, T. , & Murphy, J. (2022). Predicting risk along the suicidality continuum: A longitudinal, nationally representative study of the Irish population during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 52, 83–98. 10.1111/sltb.12783

REFERENCES

- Alsuhibani, A. , Shevlin, M. , & Bentall, R. P. (2020). Atheism is not the absence of religion: Development of the Monotheist and Atheist Belief Scales and associations with death anxiety and analytic thinking. Unpublished paper. 2020; School of Psychology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, England, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, L. , Kapur, N. , Turnbull, R. , & Richards, N. & the National Confidential Inquiry team (2020). Suicide in England since the COVID‐19 pandemic ‐ early figures from real‐time surveillance. http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=51861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais, A. L. , Elisabeth Wells, J. , Mcgee, M. A. , & Oakley Browne, M. A. , & New Zealand Mental Health Survey Research Team (2006). Suicidal behaviour in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(10), 896–904. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, P. E. , Minot, S. , Cooper, C. , Dennis, M. , Meltzer, H. , Jenkins, R. , & Brugha, T. (2010). Suicidal ideation, self‐harm and attempted suicide: results from the British psychiatric morbidity survey 2000. European Psychiatry, 25, 427–431. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C. , Zeau, B. , Rivat, C. , Blugeot, A. , Hamon, M. , & Benoliel, J. J. (2008). Repeated social defeat‐induced depression‐like behavioral and biological alterations in rats: involvement of cholecystokinin. Molecular Psychiatry, 13(12), 1079–1092. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolote, J. M. , Fleischmann, A. , De LEO, D. , Bolhari, J. , Botega, N. , De silva, D. , Thi thanh, H. T. , Phillips, M. , Schlebusch, L. , Värnik, A. , Vijayakumar, L. , & Wasserman, D. (2005). Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE‐MISS community survey. Psychological Medicine, 35(10), 1457–1465. 10.1017/S0033291705005404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, T. , Scott, J. G. , Munir, K. , Renzaho, A. M. N. , Rawal, L. B. , Baxter, J. , & Mamun, A. A. (2020). Global variation in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety and their correlates among adolescents: A population based study of 82 countries. EClinicalMedicine, 24, 100395. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R. A. , Gallagher, H. C. , Gibbs, L. , Pattison, P. , MacDougall, C. , Harms, L. , Block, K. , Baker, E. , Sinnott, V. , Ireton, G. , Richardson, J. , Forbes, D. , & Lusher, D. (2017). Mental health and social networks after disaster. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(3), 277–285. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr, K. , & Dugas, M. J. (2002). The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 931–945. 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon‐Anyosa, R. , & Kaufman, J. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. medRxiv [Preprint.] 10.1101/2020.07.11.20150193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistics Office of Ireland . (2020). Census 2016 Reports. https://www.cso.ie/en/census/ [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M. , Shevlin, M. , Brewin, C. R. , Bisson, J. I. , Roberts, N. P. , Maercker, A. , Karatzias, T. , & Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ): Development of a self‐report measure of ICD‐11 PTSD and Complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138, 536–546. 10.1111/acps.12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coroners Court of Victoria (2020, October 2‐5). Coroners Court Monthly Suicide Data Report. https://www.coronerscourt.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020‐10/Coroners%20Court%20Suicide%20Data%20Report%20‐%20Report%202%20‐%2005102020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, R. J. , & Kapusta, N. D. (2017). A social‐ecological framework of theory, assessment, and prevention of suicide. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1756. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga, R. , Grotenhuis, M. , & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two‐item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman‐Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. 10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie, C. A. , Farias Machado, P. , Carl, J. R. , Kyle, S. D. , Cape, J. , Siriwardena, A. N. , & Luik, A. I. (2018). The Sleep Condition Indicator: reference values derived from a sample of 200 000 adults. Journal of Sleep Research, 27(3), e12643. 10.1111/jsr.12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie, C. A. , Kyle, S. D. , Hames, P. , Gardani, M. , Fleming, L. , & Cape, J. (2014). The Sleep Condition Indicator: a clinical screening tool to evaluate insomnia disorder. British Medical Journal Open, 4, e004183. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, E. , Hawton, K. , Rodham, K. , & Deeks, J. (2005). The prevalence of suicidal phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of population‐based studies. Suicide & Life‐Threatening Behavior, 35(3), 239–250. 10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust, J. , Shah, S. , Du, C. , Li, S. Lin, Z. , & Krumholz, H. (2020). Suicide deaths during the stay‐at‐home advisory in Massachusetts. medRxiv 2020. [Preprint.] 10.1101/2020.10.20.20215343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K. R. , Franklin, J. C. , Ribeiro, J. D. , Kleiman, E. M. , Bentley, K. H. , & Nock, M. K. (2015). Meta‐analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self‐injury. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 156–167. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J. C. , Ribeiro, J. D. , Fox, K. R. , Bentley, K. H. , Kleiman, E. M. , Huang, X. , Musacchio, K. M. , Jaroszewski, A. C. , Chang, B. P. , & Nock, M. K. (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta‐analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 187–232. 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators , (2018). Global, regional, and national age‐sex‐specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet, 392(10159), 1736–1788. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, K. , Dziurawiec, S. , & Lee, C. W. (2013). Dialectical behaviour therapy for the treatment of emotion dysregulation and trauma symptoms in self‐injurious and suicidal adolescent females: a pilot programme within a community‐based child and adolescent mental health service. Psychiatry Journal, 2013, 145219. 10.1155/2013/145219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazinour, M. , Mofidi, N. , & Richter, J. (2010). Continuity from suicidal ideations to suicide attempts? An investigation in 18–55 years old adult Iranian Kurds. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(973), 981. 10.1007/s00127-009-0136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, E. , Kavalidou, K. , Bonner, B. , O'Hagan, D. , & Corcoran, P. (2020). Risk of repetition and subsequent self‐harm following presentation to hospital with suicidal ideation: A longitudinal registry study. EClinicalMedicine, 23, 100378. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Service Executive (2020). NOSP Briefing on Suicide Figures. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental‐health‐services/connecting‐for‐life/publications/nosp‐briefing‐on‐suicide‐figures.html [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, A. , Klein, A. M. , Brähler, E. , Glaesmer, H. , Luck, T. , Riedel‐Heller, S. G. , Wirkner, K. , & Hilbert, A. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener GAD‐7 based on a large German general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 338–344. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. E. , Waite, L. J. , Hawkley, L. C. , & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population‐based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, P. , Shevlin, M. , McBride, O. , Murphy, J. , Karatzias, T. , Bentall, R. P. , Martinez, A. , & Vallières, F. (2020). Anxiety and depression in the Republic of Ireland during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142, 249–256. 10.1111/acps.13219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, T. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E. D. , May, A. M. , & Saffer, B. Y. (2016). Suicide, Suicide Attempts, and Suicidal Ideation. Annual review of clinical psychology, 12, 307–330. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K. , Spitzer, R. L. , & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. , & Stuart, E. A. (2019). Best (but oft‐forgotten) practices: missing data methods in randomized controlled nutrition trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109, 504–508. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo, R. (2002). A caveat on using single‐item versus multiple‐item scales. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(1), 68–75. 10.1108/02683940210415933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manea, L. , Gilbody, S. , & McMillan, D. (2012). Optimal cut‐off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9): a meta‐analysis. CMAJ, 184(3), E191–E196. 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars, B. , Heron, J. , Klonsky, E. D. , Moran, P. , O'Connor, R. C. , Tilling, K. , Wilkinson, P. , & Gunnell, D. (2019). Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non‐suicidal self‐harm: a population‐based birth cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(4), 327–337. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, O. , Murphy, J. , Shevlin, M. , Miller, J. G. , Hartman, T. K. , Hyland, P. , Levita, L. , Mason, L. , Martinez, A. P. , McKay, R. , Stocks, T. V. A. , Bennett, K. M. , & Bentall, R. P. (2021). Monitoring the psychological, social, and economic impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the population: Context, design and conduct of the longitudinal COVID‐19 psychological research consortium (C19PRC) study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 30(1), e1861. 10.1002/mpr.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, S. , Webb, M. , & Brown, D. (2012). All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 830–853. 10.1037/a0028724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, S. , Bebbington, P. , Jenkins, R. , & Brugha, T. (Eds.) (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (2018). Mplus version 8.2. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman, J. , de Graaf, R. , & Vollebergh, W. (2004). The suicidal process; prospective comparison between early and later stages. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(1), 43–52. 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock, M. K. , Borges, G. , Bromet, E. J. , Alonso, J. , Angermeyer, M. , Beautrais, A. , Bruffaerts, R. , Chiu, W. T. , de Girolamo, G. , Gluzman, S. , de Graaf, R. , Gureje, O. , Haro, J. M. , Huang, Y. , Karam, E. , Kessler, R. C. , Lepine, J. P. , Levinson, D. , Medina‐Mora, M. E. , Ono, Y. , … Williams, D. (2008). Cross‐national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(2), 98–105. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, R. C. (2011). Towards an integrated motivational‐volitional model of suicidal behaviour. In O'Connor R. C., Platt S., & Gordon J. (Eds.), International handbook of suicide prevention: Research, policy and practice (pp. 181–198). Wiley Blackwell. 10.1002/9781119998556.ch11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, R. , Wetherall, K. , Cleare, S. , McClelland, H. , Melson, A. , Niedzwiedz, C. , O'Carroll, R. E. , O'Connor, D. B. , Platt, S. , Scowcroft, E. , Watson, B. , Zortea, T. , Ferguson, E. , & Robb, K. (2020). Mental health and wellbeing during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID‐19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–8. Advance online publication. 10.1192/bjp.2020.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2019). Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. 10.1787/4dd50c09-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, M. D. , Wilson, D. , & Roster, C. A. (2018). Development and application of a self‐report measure for assessing sensitive information disclosures across multiple modes. Behavior Research Methods, 50(4), 1734–1748. 10.3758/s13428-017-0953-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel, S. , Sedhai, Y. R. , & Atreya, A. (2020). An increase in suicides amidst the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Nepal. Medicine, Science and the Law, 61(2), 161–162. 10.1177/0025802420966501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P. , & Mehlum, L. (2020). National observation of death by suicide in the first 3 months under COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(1), 92–93. 10.1111/acps.13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt, B. , & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10‐item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reger, M. A. , Stanley, I. H. , & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019: a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1093. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060 pmid:32275300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, J. D. , Franklin, J. C. , Fox, K. R. , Bentley, K. H. , Kleiman, E. M. , Chang, B. P. , & Nock, M. K. (2016). Self‐injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 225–236. 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapp, S. G. , & Harrod, W. J. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief version of Levenson's locus of control scale. Psychological Reports, 72(2), 539–550. 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.2.539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J. L. , & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 144–147. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten, J. P. , van Os, J. , & Cantor‐Graae, E. (2016). The social defeat hypothesis of schizophrenia: issues of measurement and reverse causality. World Psychiatry, 15(3), 294–295. 10.1002/wps.20369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. W. , Dalen, J. , Wiggins, K. , Tooley, E. , Christopher, P. , & Bernard, J. (2008). The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. L. , Kroenke, K. , Williams, J. B. , & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD‐7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone, D. M. , Holland, K. M. , Bartholow, B. N. , Crosby, A. E. , Davis, S. P. , & Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policies, programs, and practice. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Sveticic, J. , & De Leo, D. (2012). The hypothesis of a continuum in suicidality: A discussionon its validity and practical implications. Mental Illness, 4, e15. 10.4081/mi.2012.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell, S. V. , Martin, G. E. , Page, A. , Hasking, P. , & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self‐injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Suicide & Life‐Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303. 10.1111/sltb.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier, N. , Taylor, K. , & Gooding, P. (2008). Cognitive‐behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Behavior Modification, 32(1), 77–108. 10.1177/0145445507304728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás‐Sábado, J. , Gómez‐Benito, J. , & Limonero, J. T. (2005). The Death Anxiety Inventory: a revision. Psychological Reports, 97(3), 793–796. 10.2466/pr0.97.3.793-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, M. , Nordström, R. , & Matsubayashi, T. (2020). Suicide and mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Japan. medRxiv 2020 [Preprint.] 10.1101/2020.10.06.20207530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant, G. E. (2015). Triumphs of Experience: The Men of the Harvard Grant Study. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vallières, F. , Ceannt, R. , Daccache, F. , Daher, R. A. , Sleiman, J. B. , Gilmore, B. , Byrne, S. , Shevlin, M. , Murphy, J. , & Hyland, P. (2018). The validity and clinical utility of the ICD‐11 proposals for PTSD and Complex PTSD among Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138, 547–557. 10.1111/acps.12973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, D. , & Drurkee, T. (2009). Strategies in suicide prevention. In Wasserman D., & Wasserman C. (Eds.), Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention (pp. 381–388). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock, J. , & Knox, K. L. (2007). The relationship between self‐injurious behavior and suicide in a young adult population. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(7), 634–640. 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor, T. D. , Curtis, R. G. , & Luszcz, M. A. (2015). Sense of purpose as a psychologicalresource for aging well. Developmental Psychology, 51(7), 975–986. https://doi‐org.ucd.idm.oclc.org/10.1037/dev0000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: progress, examples and indicators. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman, G. , Hawton, K. , Wasserman, D. , van Heeringen, K. , Arensman, E. , Sarchiapone, M. , Carli, V. , Höschl, C. , Barzilay, R. , Balazs, J. , Purebl, G. , Kahn, J. P. , Sáiz, P. A. , Lipsicas, C. B. , Bobes, J. , Cozman, D. , Hegerl, U. , & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10‐year systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]