Summary

The coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid‐19) pandemic has had devastating effects on public health worldwide, but the deployment of vaccines for Covid‐19 protection has helped control the spread of SARS Coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection where they are available. The common side effects reported following Covid‐19 vaccination were mostly self‐restricted local reactions that resolved quickly. Nevertheless, rare vaccine‐induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) cases have been reported in some people being vaccinated against Covid‐19. This review summarizes the thromboembolic events after Covid‐19 vaccination and discusses its molecular mechanism, incidence rate, clinical manifestations and differential diagnosis. Then, a step‐by‐step algorithm for diagnosing such events, along with a management plan, are presented. In conclusion, considering the likeliness of acquiring severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and its subsequent morbidity and mortality, the benefits of vaccination outweigh its risks. Hence, if not already initiated, all governments should begin an effective and fast public vaccination plan to overcome this pandemic.

Keywords: Covid‐19, CSVT, PVT, SARS‐CoV‐2, Thrombosis, Vaccination, VITT, VIPIT

Abbreviations

- AAT

acute aortic thrombosis

- ACE

arterial cerebral embolism

- AHA

acquired haemophilia A

- AVT

azygos vein thrombosis

- BAH

bilateral adrenal haemorrhage

- CVST

cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

- CVT

cerebral venous thrombosis

- DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

- HIT

heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia

- HITT

heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia with thrombosis

- HS

haemorrhagic stroke

- IB

ischemic bowel

- ICH

intracranial haemorrhage

- IS

ischemic stroke

- ITP

immune thrombocytopenia

- IVST

intracranial venous sinus thrombosis

- JVT

jugular vein thrombosis

- LIOVT

left inferior ophthalmic vein thrombosis

- LPH

limb petechial hematoma

- MCAI

middle coronary artery infarction

- MCAT

middle cerebral artery thrombosis

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PAT

popliteal artery thrombosis

- PTE

pulmonary thromboembolism

- PVT

portal vein thrombosis

- SAH

subarachnoid haemorrhage

- SOVT

superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis

- SRH

subcapsular renal hematoma

- SVT

splanchnic vein thrombosis

- TMA

thrombotic microangiopathy

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- VITT

vaccine‐induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia

1. INTRODUCTION

Virchow's triad states that hypercoagulability, stasis and vessel wall abnormalities are the main components of thrombosis. 1 Stasis due to polycythemia and hypoxemia, hypercoagulability state due to various underlying factors, such as factor V Leiden, 2 protein C/S deficiency and vascular endothelium abnormalities/damage due to ageing, medications or other factors can lead to thrombosis. 3 Thrombosis can also be triggered by the interaction between various genes and the environment. 3

Sedentary lifestyle, air travel, 4 obesity, active smoking, 5 hormonal changes during pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, neoplasms 6 and nephrotic syndrome can be the underlying cause of thromboembolic events (TE). 7 Moreover, trauma and major surgeries, including hip arthroplasty, autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Behçet's syndrome, 8 and systemic vasculitis, 9 inflammatory disease, including inflammatory bowel disease, can also lead to TE. 10 Furthermore, medications, such as oral contraceptives, 11 chemotherapeutic agents, including thalidomide, cisplatin, bleomycin and gemcitabine, 12 immunomodulatory agents, such as infliximab, 13 and antipsychotic drugs are also proposed to be a cause of clot formation. 14 Additionally, sepsis and infections may also induce TE. 15

Thrombosis is a typical sequel of severe infections. 15 Infectious agents, such as Epstein‐Bar virus, Herpesvirus, Cytomegalovirus, H1N1 Influenza virus, 16 , 17 Measles morbillivirus, 18 Rubella virus, 19 Varicella‐zoster virus, 20 Herpes zoster virus, 21 Human immunodeficiency virus, 22 , 23 and recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has been implicated in the TE incidence. 24 , 25

On the other hand, the role of vaccines in preventing or triggering thrombosis has also been reported previously. For example, it was demonstrated that the Quadrivalent HPV vaccine, 26 , 27 Influenza vaccine 28 , 29 and measles vaccine 30 could cause TE. Moreover, recently, there has been some report of TE incidence after administrations of some of the Covid‐19 vaccines, especially, Oxford‐AstraZeneca vaccine (ChAdOx1) 31 and Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) vaccine. 32

Hence, in this study, an overview of the vaccine‐induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), along with its molecular mechanism, incidence rate, clinical manifestations, and differential diagnosis, are discussed. Then, a step‐by‐step algorithm for diagnosing and management of patients with such event are presented.

2. COVID‐19 VACCINES AND THROMBOSIS

Many cases of inadvertent thrombotic events and thrombocytopenia have been reported since February 2021, after injecting coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid‐19) vaccines. 33 The Oxford‐AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19) vaccine is a recombinant chimpanzee adenoviral vector containing the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike glycoprotein gene. Despite being very effective at diminishing Covid‐19‐related morbidity and mortality, it has been linked to an increased risk of thrombosis in vaccinated individuals. 34 Consequently, this vaccine has been temporarily suspended in some European countries, though after careful investigation and risk‐benefit evaluations, vaccination was resumed. 35 Moreover, severe thrombotic thrombocytopenia events were also reported following the administration of Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) Ad26.COV2.S vaccine, a recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector containing the spike glycoprotein gene of SARS‐CoV‐2. 32 , 36

3. MECHANISM OF VACCINE‐INDUCED THROMBOSIS

VITT has somehow similar mechanism to that of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). HIT is a significant complication that could happen in patients receiving this medication, and physicians should be vigilant to the development of this adverse event. It is caused by the formation of antibodies against platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin complexes. 37 While these antibodies are produced in many patients receiving heparin, a few them develop deteriorating clinical manifestations, such as HIT with thrombosis, referred more commonly as HITT. 37 Regardless of whether a patient has an identified thrombus in the setting of HIT, HIT alone is a hypercoagulable state requiring alternative anticoagulation promptly. 37 Nevertheless, prothrombotic disorders can be induced with triggers other than heparin, including polyanionic drugs (such as hypersulfated chondroitin sulfate 38 and pentosan polysulfated). 39 Moreover, it has also been observed that after some orthopedic surgeries, such as knee replacement surgery, 40 , 41 and viral and bacterial infections, such calamitous events can be induced even in the absence of any prior exposure to mentioned medications. 38 , 42 These non‐pharmacologic‐induced clinical scenarios were categorized as autoimmune heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (aHIT). 43 Unlike HIT, patients with aHIT have remarkably severe thrombocytopenia, increased chances of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and atypical TE. Although heparin can significantly activate the platelets of these patients, their platelets are also unusually active in the absence of heparin.

Consequently, when these abnormal antibodies were detected in thrombocytopenic patients without prior history of heparin administration, the term spontaneous HIT was proposed. 43 , 44 Recently, a similar phenomenon was diagnosed in some patients after being vaccinated for Covid‐19, which was then named VITT, formerly known as vaccine‐induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT). 45 Unfortunately, the predisposing factors behind this calamitous event are not yet fully understood. 46

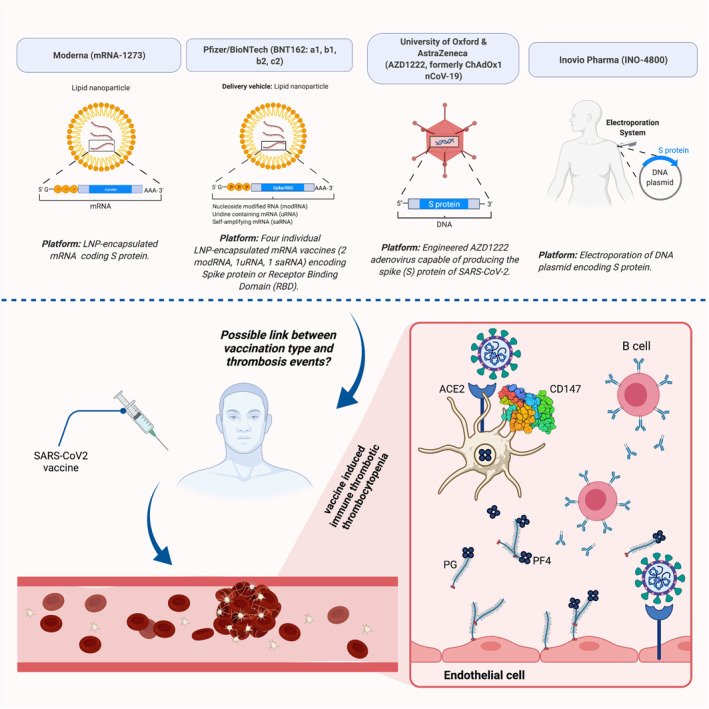

The currently proposed mechanisms of VITT are HIT‐similar increased antiplatelet factor 4 (PF4), or PF4‐dependent platelet activation, an inflammatory process of antibody formation against platelet antigens to massive platelet activation via the Fc receptor, leading to platelet consumption with thrombus formation and thrombocytopenia. 33 These antibodies tend to form between 4 and 16 days after vaccination. 35 Whether the vaccine itself or the vaccine‐induced high immune response is the factor promoting the formation of platelets‐activating antibodies is not yet understood. Possibly, adenovirus attachment to platelets leads to platelet pre‐activation contributing in part to this inflammatory process. 33 Another theory is the potential role of free DNA in the vaccine in forming reactive antibodies to PF4. 47 Previously in a murine model, it has been illustrated that DNA and RNA can bind to PF4, forming multimolecular complexes which, alternatively, can attach to host anti‐PF4‐heparin antibodies (Figure 1). 48

FIGURE 1.

Possible link of different Covid‐19 vaccines with thrombotic and thrombocytopenia events. Structure type and platform for four SARS‐CoV2 vaccines have been provided. Although more studies are required to reach a common point, thrombotic events have been reported for several specific vaccines but not for others. Prothrombotic thrombocytopathy mimicking heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia has been found in severe cases of Covid‐19 and after vaccination with some vaccines. This process may involve ACE2 and CD147, SARS‐CoV2 receptors. PGs and PF4 from platelets interact with B cells. Next, produced antibodies bind the endothelial surface (RCSB.org; PDB ID: 3QQN). ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; CD, cluster of differentiation; nCoV, novel coronavirus; PF4, platelet factor 4; PG, proteoglycan; SARS‐CoV2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Created with BioRender.com

4. INCIDENCE OF THROMBOTIC EVENTS

It is estimated that the incidence rate of VITT is between one in 125,000 to one in a million vaccinated people. This adverse event can affect any age and sex group. However, the risk has been higher in younger individuals, particularly those aged 20–29 years, for whom the risk‐benefit should be weighed very carefully. 49

In a preprint study conducted on 537,913 cases with Covid‐19, the incidence of CSVT and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) after Covid‐19 diagnosis was 42.8 (95% CI: 28.5–64.2) and 392.3 (95% CI: 342.8–448.9) per million, respectively. Regarding the CSVT incidence rate, it was significantly higher compared to a matched cohort of patients with an Influenza diagnosis (RR = 3.83, 95% CI: 1.56–9.41, p < 0.001) and patients receiving an mRNA vaccine (either Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccines) (RR = 6.67, 95% CI: 1.98–22.43, p < 0.001). 50

Moreover, regarding the PVT incidence rate, it was also significantly higher compared to a matched cohort of patients with an influenza diagnosis (RR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.06–1.83, p = 0.02) and patients receiving an mRNA vaccine (RR = 7.40, 95% CI: 4.87–11.24, p < 0.001). 50 Furthermore, when excluding patients with prior CSVT or PVT diagnoses, post‐Covid‐19 CSVT or PVT incidence rates were 35.3 (95% CI: 22.6–55.2) and 175.0 (95% CI: 143.0–214.1) per million, respectively. The mortality rate among Covid‐19 patients after such complications was 17.4% (95% CI: 6.98–37.1%) for CSVT and 19.9% (95% CI: 15.1–25.8%) for PVT, which was significantly higher than patients without such adverse events (CSVT: p = 0.005, PVT: p < 0.001). 50 Also, it was determined that CSVT incidence was significantly correlated with higher D‐dimer levels, while PVT incidence was significantly correlated with low fibrinogen levels and thrombocytopenia. 50

Interestingly, when dividing the study timeline into three two‐week periods and comparing them (weeks 1 and 2 vs. weeks 3 and 4, and weeks 1 and 2 vs. weeks 5 and 6), valuable data were obtained regarding CSVT/PVT incidence risk in the course of Covid‐19. The risk of CSVT incidence were significantly decreased in the following weeks than the first 2 weeks after Covid‐19 diagnosis (weeks 3 and 4: RR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.098–0.59, p < 0.001; weeks 5 and 6: RR = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.036–0.40, p < 0.001). 50 Similarly, the incidence risk of PVT was also significantly decreased in the following weeks compared to the first 2 weeks post‐Covid‐19 diagnosis (weeks 3 and 4: RR = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.14–0.27, p < 0.001; weeks 5 and 6: RR = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.080–0.18, p < 0.001). 50

5. REPORTED THROMBOTIC EVENTS

Various thrombotic events have been reported after vaccination, including intracranial venous sinus thrombosis or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), 51 hepatic and splenic vein thrombosis, 52 PVT, 50 , 53 deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 54 pulmonary thromboembolism, 47 DIC, 55 left inferior ophthalmic vein thrombosis, 56 and bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis. 57 Surprisingly, as recently approved in a presentation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for unknown reasons, it has been a trend that VITT complications mainly involve cerebral vessels. 58

As it can be inferred from Table 1, the incidence of thrombotic and thrombocytopenia events is higher in adenoviral‐vector vaccines, that is, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca vaccines, than the mRNA vaccines, that is, Pfizer/BioNTech, and Moderna vaccines. Moreover, no thrombotic event was reported so far following administration of mRNA vaccines, and these vaccines mainly were related to the exacerbation of the pre‐existing bleeding disorders, for example, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) 59 , 60 and acquired haemophilia A. 61 On the other hand, the adenoviral‐vector vaccines are chiefly related to thrombotic events, such as CVST, PVT and pulmonary thromboembolism.

TABLE 1.

Summary of reported thrombotic and thrombocytopenia events after administration of COVID‐19 vaccine

| Reference | Vaccine type | Number of cases | Gender (n) | Age (years) | Time from vaccination to admission (days) | Platelet count (cells × 109/L) | INR | aPTT (s) | Fibrinogen (g/L) | D‐dimer (ng/mL) | Anti‐PF4‐heparin antibody | Clinical features (incidence, n) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tarawneh et al. 62 | Pfizer/BioNTech | 1 | Male | 22 | 3 | 2 | Normal | Normal | Normal | ‐ | ‐ | ITP | Discharged |

| Carli et al. 54 | Pfizer/BioNTech | 1 | Female | 66 | 3 a | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Not done | DVT | Discharged |

| Radwi et al. 61 | Pfizer/BioNTech | 1 | Male | 69 | 9 | 237 | Normal | 115.2 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | AHA | Discharged |

| Toom et al. 63 | Moderna | 1 | Female | 36 | 14 | 3 b | Normal | Normal | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ITP | Discharged |

| Malayala et al. 64 | Moderna | 1 | Male | 60 | 2 | 84 | 1.13 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ITP | Discharged |

| See et al. 65 | Johnson & Johnson | 12 | Female | 18–60 | 10–25 | 45.75 | 1.2 | 27.6 | 1.59 | 22,785 | Positive (11); Not done (1) |

|

|

| Muir et al. 36 | Johnson & Johnson | 1 | Female | 48 | 19 | 13 | Normal | 41 | 0.89 | 117,500 | Positive |

|

Unknown |

| McDonnell et al. 56 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Female | 58 | 9 | 31 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.83 | 119,000 | ‐ | LIOVT | Discharged (1) |

| Haakonsen et al. 66 | AstraZeneca | 2 | Female (1); Male (1) | 30–49 | 27–29 | 318.5 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Negative | ‐ | DVT | Discharged (2) |

| Wolf et al. 53 | AstraZeneca | 3 | Female | 35 | 13 | 75.7 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 9,170 | Positive (3) | IVST (3) | Discharged (3) |

| D’Agostino et al. 55 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Female | 54 | 12 | Decreased | 1.5 | 41 | Normal | Elevated | ‐ | DIC | Death |

| Tiede et al. 67 | AstraZeneca | 5 | Female | 58.6 | 8.4 | 49.2 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | >35,200 | Positive (5) |

|

Recovering (5) |

| Franchini et al. 51 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Male | 50 | 11 | 15 | 1.19 | Normal | 0.98 | >10,000 | Positive | CVST | Discharged |

| Thaler et al. 68 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Female | 62 | 9 | 26 | Normal | 38.7 | 0.84 | 52,660 | Positive | LPH | Discharged |

| Bayas et al. 57 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Female | 55 | 10 | 30 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Negative |

|

Discharged |

| Scully et al. 69 | AstraZeneca | 23 | Female (14); Male (9) | 46 | 12 | 45.23 | 1.23 | 30.8 | 1.88 | 33,546 | Positive (14); Not done (8); Negative (1) |

|

|

| Mehta et al. 70 | AstraZeneca | 2 | Male (2) | 28.5 | 7.5 | 24.5 | ‐ | ‐ | 1.35 | ‐ | Positive (1); Negative (1) | CSVT (2) | Death (2) |

| Castelli et al. 71 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Male | 50 | 11 | 20 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.98 | >10,000 | Negative | CVST | Death |

| Greinacher et al. 31 | AstraZeneca | 11 | Female (9); Male (2) | 36 | 9.27 | 20 c | 1.36 c | 42.3 c | 1.92 c | 36,080 c | Positive (9); Not done (2) |

|

|

| Schultz et al. 45 | AstraZeneca | 5 | Female (4); Male (1) | 40.8 | 8.4 | 27 d | 1.14 d | 27 d | 1.52 d | >35,000 d | Positive (5) |

|

|

| Blauenfeldt et al. 72 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Female | 60 | 7 | 50 | 1.1 | 28 | 3.74 | 41,800 | Not done |

|

Death |

| Bjørnstad‐Tuveng et al. 73 | AstraZeneca | 1 | Female | 30–39 | 10 | 37 | Normal | 27 | 2.2 | >7,000 | Positive | ICH | Death |

Note: For studies with more than one patient, the laboratory values are reported as mean.

Abbreviations: AAT, acute aortic thrombosis; ACE, arterial cerebral embolism; AHA, acquired haemophilia A; AVT, azygos vein thrombosis; BAH, Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage; CVST, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis; CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; HS, haemorrhagic stroke; IB, ischemic bowel; ICH, intracranial haemorrhage; IS, ischemic stroke; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; IVST, intracranial venous sinus thrombosis; JVT, jugular vein thrombosis; LIOVT, left inferior ophthalmic vein thrombosis; LPH, limb petechial hematoma; MCAI, middle coronary artery infarction; MCAT, middle cerebral artery thrombosis; MI, myocardial infarction; PAT, popliteal artery thrombosis; PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism; PVT, portal vein thrombosis; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage; SRH, subcapsular renal hematoma; SOVT, superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis; SVT, splanchnic vein thrombosis; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy.

This patient developed thrombosis after the second dose of her mRNA vaccine. Also, it is noteworthy that this patient had a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation.

This patient had a past medical history of familial thrombocytopenia classified as ITP.

For this study, the median nadir of platelet count (n = 11), INR peak (n = 7), aPTT peak (n = 7), fibrinogen nadir (n = 6) and D‐dimer peak (n = 5) were reported.

For this study, the median nadir of platelet count, INR peak, aPTT peak, fibrinogen nadir and D‐dimer peak were reported.

Furthermore, for the adenoviral‐vector vaccine, there was no report of vaccine‐related thrombotic and thrombocytopenia events before 5 days post‐vaccination, whereas, for the mRNA vaccines, such events were reported as soon as two days after vaccination. It is also noteworthy that the platelet count was reported to be as low as 2 × 109/L after administration of mRNA vaccines, while the platelet count mainly was not below 20 × 109/L regarding adenoviral‐vector vaccines administration.

6. MANIFESTATIONS OF THROMBOTIC EVENTS

Several complications have been reported following the Covid‐19 vaccination, some of which are localized and some systemic. Urticarial reactions, nausea and vomiting, myalgia or arthralgia, feverishness and flashing, and injection site reactions have been observed quite commonly, not life threatening, and can be treated symptomatically. 74 , 75 However, there have been some manifestations that are indicative of a potential TE incidence. Persistent or severe headache, seizure, focal neurological symptoms or blurred vision can suggest CSVT or arterial stroke, while dyspnoea, chest pain or chest tightness can manifest pulmonary embolism or cardiac infarction. Moreover, persistent abdominal pain can signify PVT, whereas lower extremities enema, erythema, or tenderness may indicate DVT or acute limb ischemia. 46

Therefore, any symptom or sign indicating thrombosis, including back pain, headache, gait imbalance, paraesthesia, hemiparesis or hemiplegia, drowsiness, or visual disturbance, should be taken seriously and evaluated with extra caution. 76 It is noteworthy that some symptoms, such as headaches for one or 2 days and other flu‐like symptoms like myalgia and arthralgia, are expected consequences of vaccination and should not be overestimated or concerning. Nonetheless, if any of the symptoms mentioned above last for more than three days, further assessments are mandated. 35

7. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES FOR THROMBOTIC EVENTS

In all TE settings, other thrombocytopenic thrombosis causes, including antiphospholipid syndrome, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, and thrombotic microangiopathies, such as immune thrombocytopenic purpura, or atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome, and underlying haematological malignancies should be excluded. 77 Therefore, in all patients with a suspicion of such events, the following assessments should always be performed before confirming VITT: The thrombophilia screening should be negative; antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin IgG antibodies should not be detected; complement levels (C1q, C3 and C4), their activation products (sC5b‐9), and ADAMTS13 activity are expected to be within the normal range; and a history of recent heparin therapy before symptoms onset should also be absent. Besides, it is vital to exclude active and acute SARS‐CoV‐2 infection for any individual who complains of Covid‐19 vaccine‐related side effects. Thus, a negative SARS‐CoV‐2 (Reverse Transcription‐Polymerase Chain Reaction) RT‐PCR test is required.

High levels of anti‐PF4‐polyanion complex IgG antibodies are diagnostic and confirm VITT. In general, it is recommended that clinicians consider a low threshold for requesting an assessment for PF4‐heparin antibodies via enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in any patient who presents with vaccine‐related compatible symptoms. 47

8. CONFIRMING THE DIAGNOSIS OF THROMBOTIC EVENTS

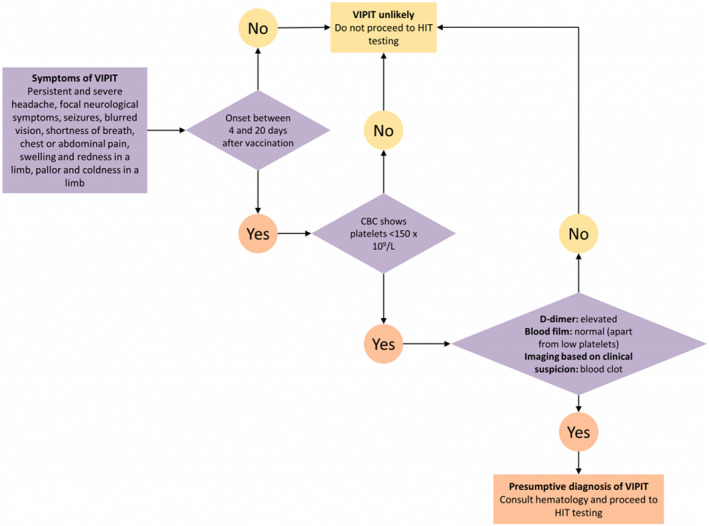

In any Covid‐19 vaccinated patient who presents with symptoms of thrombosis, such as shortness of breath, lower limb swelling, unusual abdominal pain, unexplained subcutaneous bleeding, confusion and double vision, during the first 4–20 days post‐vaccination, VITT should be highly suspected. 76 Complete blood count and peripheral blood smear, a prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and D‐dimer, fibrinogen and anti‐PF4 IgG (ELISA method) antibody levels should be checked. 78 Moreover, based on the clinical suspicion, an appropriate imaging modality, such as computed tomography (CT) venography, brain CT scan, MRI venography or colour Doppler ultrasound, should be performed. 46 In these patients, a reduction in platelet count to <150 × 109/L, 46 an elevation of D‐dimer > 4000 ng/ml FEU, 69 and confirmation of thrombosis by appropriate imaging suggest VITT. 46 This condition should trigger an urgent haematology consultation in order to request testing and initiate empirical treatment. The diagnosis is confirmed by identifying antibodies against the complex of PF4 and heparin. 46 Figure 2 illustrates a step‐by‐step algorithm for diagnosing VITT.

FIGURE 2.

A step‐by‐step algorithm for diagnosing VIPIT, which is now changed to VITT (Courtesy of 2021 Ontario Covid‐19 Science Advisory Table 46 ). VIPIT, vaccine‐induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia; VITT, vaccine‐induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia

9. MANAGEMENT OF THROMBOTIC EVENTS

Any patient with a suspected or confirmed VITT must be followed up and managed similar to HIT. It is vital to prohibit any heparin‐based anticoagulants and platelet transfusions until VITT is excluded. Furthermore, warfarin is not recommended in this condition due to a paradoxical increase in thrombotic tendency. However, other non‐heparin‐based anticoagulants, such as direct thrombin inhibitors (including bivalirudin, argatroban and dabigatran), direct factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban), and indirect (antithrombin‐dependent) Xa inhibitors (such as fondaparinux) are not contraindicated in these settings. These medications should be initiated empirically while awaiting laboratory confirmation. 68 After VITT confirmation and incidence of a severe, life‐threatening thrombosis event or refractory VITT, such as CSVT, administration of a high dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (1 g/kg of body weight daily for 2 days), 46 , 79 corticosteroids 31 , 69 and plasma exchange are reasonable. 69

10. PROPHYLAXIS OF THROMBOTIC EVENTS

Routine prophylaxis with anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents to avoid TE following Covid‐19 vaccination is not currently indicated. Nonetheless, exercise and fluid replacement therapy are beneficial, and if the individual develops severe flu‐like symptoms along with risk factors of thromboembolism, pharmacological thromboprophylaxis can be started on an individual‐specific basis. 35

11. CONCLUSION

There are still many ambiguities regarding TEs following the Covid‐19 vaccination. So far, it has been demonstrated that the risk of VITT is much lower for the mRNA vaccines than the adenoviral‐vector vaccines, with no reported case of VITT after administration of mRNA vaccines. However, these vaccines may exacerbate pre‐existing bleeding disorders, such as ITP. Therefore, it is vital to monitor vaccinated people for at least a month for any adverse events, and if necessary, appropriate diagnostic modalities and therapeutic options should be utilized to minimize such catastrophic events. Also, as the incidence of thrombotic events, such as CVT, is significantly lower after administering Covid‐19 vaccines than the disease itself, the benefits of vaccination outweigh its risks for all genders and age groups. Hence, all stakeholders, medical professionals and governments should encourage people to receive the Covid‐19 vaccine.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Zeinab Mohseni Afshar: Data collection and writing the manuscript. Arefeh Babazadeh: Data collection and helped with manuscript writing. Alireza Janbakhsh: Data collection and helped with manuscript writing. Mandana Afsharian: Data collection and helped with manuscript writing. Kiarash Saleki: Visualization, software and helped with manuscript writing. Mohammad Barary: Data collection, helped with manuscript writing and provided substantial revisions to the manuscript's content. Soheil Ebrahimpour: Design of the research study, supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the clinical research development centre of Imam Reza Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, for their kind support. Figure 2 is created with BioRender.com.

Mohseni Afshar Z, Babazadeh A, Janbakhsh A, et al. Vaccine‐induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia after vaccination against Covid‐19: a clinical dilemma for clinicians and patients. Rev Med Virol. 2022;32(2):e2273. 10.1002/rmv.2273

Contributor Information

Mohammad Barary, Email: m.barary@mubabol.ac.ir.

Soheil Ebrahimpour, Email: drsoheil1503@yahoo.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Esmon CT. Basic mechanisms and pathogenesis of venous thrombosis. Blood Rev. 2009;23(5):225‐229. 10.1016/j.blre.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Cott EM, Khor B, Zehnder JL. Factor VLeiden. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(1):46‐49. 10.1002/ajh.24222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seligsohn U, Lubetsky A. Genetic susceptibility to venous thrombosis. N. Engl J Med. 2001;344(16):1222‐1231. 10.1056/NEJM200104193441607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lapostolle F, Surget V, Borron SW, et al. Severe pulmonary embolism associated with air travel. N. Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):779‐783. 10.1056/NEJMoa010378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Billy E, Clarot F, Depagne C, Korsia‐Meffre S, Rochoy M, Zores F. Thrombotic events after AstraZeneca vaccine: what if it was related to dysfunctional immune response? [published online ahead of print April 2021]. Therapie. 10.1016/j.therap.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bick RL. Cancer‐Associated thrombosis. N. Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):109‐111. 10.1056/NEJMp030086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gigante A, Barbano B, Sardo L, et al. Hypercoagulability and nephrotic syndrome. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2014;12(3):512‐517. 10.2174/157016111203140518172048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yazici H, Fresko I, Yurdakul S. Behçet's syndrome: disease manifestations, management, and advances in treatment. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(3):148‐155. 10.1038/ncprheum0436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niccolai E, Emmi G, Squatrito D, et al. Microparticles: bridging the gap between autoimmunity and thrombosis. Seminars Thromb Hemost. 2015;41(04):413‐422. 10.1055/s-0035-1549850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jess T, Gamborg M, Munkholm P, Sørensen TIA. Overall and cause‐specific mortality in ulcerative colitis: meta‐analysis of population‐based inception cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(3):609‐617. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramot Y, Nyska A, Spectre G. Drug‐induced thrombosis: an update. Drug Saf. 2013;36(8):585‐603. 10.1007/s40264-013-0054-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nadir Y, Hoffman R, Brenner B. Drug‐related thrombosis in hematologic malignancies. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2004;8(1):E4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nosbaum A, Goujon C, Fleury B, Guillot I, Nicolas JFBF. Arterial thrombosis with anti‐phospholipid antibodies induced by infliximab. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17(6):546‐547. 10.1684/ejd.2007.0280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Varia I, Krishnan RR, Davidson J. Deep‐vein thrombosis with antipsychotic drugs. Psychosomatics. 1983;24(12):1097‐1098. 10.1016/S0033-3182(83)73114-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beristain‐Covarrubias N, Perez‐Toledo M, Thomas MR, Henderson IR, Watson SP, Cunningham AF. Understanding infection‐induced thrombosis: lessons learned from animal models. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2569. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bunce PE, High SM, Nadjafi M, Stanley K, Liles WC, Christian MD. Pandemic H1N1 influenza infection and vascular thrombosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(2):e14‐e17. 10.1093/cid/ciq125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Wissen M, Keller TT, Ronkes B, et al. Influenza infection and risk of acute pulmonary embolism. Thromb J. 2007;5(1):16. 10.1186/1477-9560-5-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cambrea SC, Balasa AL, Arghir OC, Mihai CM. Fatal rare case of measles complicated by bilateral pulmonary embolism: a case report and short literature review. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(4):030006051989412. 10.1177/0300060519894120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Connolly JH, Hutchinson WM, Allen IV, et al. Carotid artery thrombosis, encephalitis, myelitis and optic neuritis associated with rubella virus infections. Brain J Neurol. 1975;98(4):583‐594. 10.1093/brain/98.4.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rabah F, El‐Banna N, Abdel‐Baki M, et al. Postvaricella thrombosis—report of two cases and literature review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(9):985‐987. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825c7993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi W‐Y, Cho Y‐K, Ma J‐S. Herpes zoster complicated by deep vein thrombosis : a case report. Kor J Pediatr. 2009;52(5):607. 10.3345/kjp.2009.52.5.607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saif MW, Greenberg B. HIV and thrombosis: a review. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2001;15(1):15‐24. 10.1089/108729101460065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saif MW, Bona R, Greenberg B. AIDS and thrombosis: retrospective study of 131 HIV‐infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2001;15(6):311‐320. 10.1089/108729101750279687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID‐19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033‐2040. 10.1182/blood.2020006000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kashi M, Jacquin A, Dakhil B, et al. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with Covid‐19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;192:75‐77. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Block SL, Brown DR, Chatterjee A, et al. Clinical trial and post‐licensure safety profile of a prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus‐like particle vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(2):95‐101. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b77906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dhar JP, Essenmacher L, Dhar R, Magee A, Ager J, Sokol RJ. The safety and immunogenicity of Quadrivalent HPV (qHPV) vaccine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Vaccine. 2017;35(20):2642‐2646. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Medeiros DM, Silva CA, Bueno C, et al. Pandemic influenza immunization in primary antiphospholipid syndrome (PAPS): a trigger to thrombosis and autoantibody production? Lupus. 2014;23(13):1412‐1416. 10.1177/0961203314540351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Balen T, Schreuder MF, de Jong H, van de Kar NCAJ. Refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in a 16‐year‐old girl: successful treatment with bortezomib. Eur J Haematol. 2014;92(1):80‐82. 10.1111/ejh.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller D, Wadsworth J, Diamond J, Ross E. Measles vaccination and neurological events. Lancet. 1997;349(9053):730‐731. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60171-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov‐19 vaccination. N. Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2092‐2101. 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schuchat A, Marks P. Joint CDC and FDA Statement on Johnson & Johnson COVID‐19 Vaccine: The Following Statement Is Attributed to Dr. Anne Schuchat, Principal Deputy Director of the CDC and Dr. Peter Marks, Director of the FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Me. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov‐19 vaccination [published online ahead of print April 9, 2021]. N. Engl J Med. 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hunter PR. Thrombosis after Covid‐19 vaccination. BMJ. 2021;373:n958. 10.1136/bmj.n958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oldenburg J, Klamroth R, Langer F, et al. Diagnosis and management of vaccine‐related thrombosis following AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccination: guidance statement from the GTH [published online ahead of print April 1, 2021]. Hämostaseologie. 10.1055/a-1469-7481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muir K‐L, Kallam A, Koepsell SA, Gundabolu K. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. N. Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1964‐1965. 10.1056/NEJMc2105869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hogan M, Berger JS. Heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT): review of incidence, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Med. 2020;25(2):160‐173. 10.1177/1358863X19898253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moores G, Warkentin TE, Farooqi MAM, Jevtic SD, Zeller MP, Perera KS. Spontaneous heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia presenting as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [published online ahead of print January 14, 2021]. Neurol Clin Pract. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosenthal MA, Rischin D, McArthur G, et al. Treatment with the novel anti‐angiogenic agent PI‐88 is associated with immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(5):770‐776. 10.1093/annonc/mdf117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. JAY RM, WARKENTIN TE. Fatal heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) during warfarin thromboprophylaxis following orthopedic surgery: another example of ‘spontaneous’ HIT? J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1598‐1600. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hwang SR, Wang Y, Weil EL, Padmanabhan A, Warkentin TE, Pruthi RK. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with spontaneous heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia syndrome after total knee arthroplasty [published online ahead of print October 1, 2020]. Platelets. 10.1080/09537104.2020.1828574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Warkentin TE, Makris M, Jay RM, Kelton JG. A spontaneous prothrombotic disorder resembling heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Am J Med. 2008;121(7):632‐636. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Greinacher A, Selleng K, Warkentin TE. Autoimmune heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(11):2099‐2114. 10.1111/jth.13813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Warkentin TE, Basciano PA, Knopman J, Bernstein RA. Spontaneous heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia syndrome: 2 new cases and a proposal for defining this disorder. Blood. 2014;123(23):3651‐3654. 10.1182/blood-2014-01-549741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schultz NH, Sørvoll IH, Michelsen AE, et al. Thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 vaccination. N. Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2124‐2130. 10.1056/NEJMoa2104882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pai M, Grill A, Ivers N, et al. Vaccine induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT) following AstraZeneca COVID‐19 vaccination. Science Briefs of the Ontario Covid‐19 Science Advisory Table; 2021;1(17). 10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.17.1.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wise J. Covid‐19: rare immune response may cause clots after AstraZeneca vaccine, say researchers. BMJ. 2021;373:n954. 10.1136/bmj.n954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jaax ME, Krauel K, Marschall T, et al. Complex formation with nucleic acids and aptamers alters the antigenic properties of platelet factor 4. Blood. 2013;122(2):272‐281. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. European Medicine Agency . COVID‐19 Vaccine AstraZeneca: Benefits Still Outweigh the Risks despite Possible Link to Rare Blood Clots with Low Blood Platelets; 2021.

- 50. Taquet M, Husain M, Geddes JR, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. Cerebral venous thrombosis and portal vein thrombosis: a retrospective cohort study of 537,913 COVID‐19 cases [published online ahead of print January 1, 2021]. medRxiv. 10.1101/2021.04.27.21256153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Franchini M, Testa S, Pezzo M, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis and thrombocytopenia post‐COVID‐19 vaccination. Thromb Res. 2021;202:182‐183. 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Muir K‐L, Kallam A, Koepsell SA, Gundabolu K. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S Vaccination [published online ahead of print April 14, 2021]. New Eng J Med. 10.1056/NEJMc2105869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wolf ME, Luz B, Niehaus L, Bhogal P, Bäzner H, Henkes H. Thrombocytopenia and intracranial venous sinus thrombosis after “COVID‐19 vaccine AstraZeneca” exposure. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1599. 10.3390/jcm10081599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Carli G, Nichele I, Ruggeri M, Barra S, Tosetto A. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurring shortly after the second dose of mRNA SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. Internal Emer Med. 2021;16(3):803‐804. 10.1007/s11739-021-02685-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. D’Agostino V, Caranci F, Negro A, et al. A rare case of cerebral venous thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation temporally associated to the COVID‐19 vaccine administration. J Personal Med. 2021;11(4):285. 10.3390/jpm11040285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McDonnell T, Cooksley T, Jain S, McGlynn S. Left inferior ophthalmic vein thrombosis due to VITT (Vaccine Induced Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia): a case report [published online ahead of print April 30, 2021]. QJM Int J Med. 10.1093/qjmed/hcab124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bayas A, Menacher M, Christ M, Behrens L, Rank A, Naumann M. Bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis, ischaemic stroke, and immune thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 vaccination. Lancet. 2021;397(10285):e11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00872-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Erman M, Steenhuysen JUS. CDC Finds More Clotting Cases after J&J Vaccine, Sees Causal Link. Reuters; 2021. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare‐pharmaceuticals/us‐cdc‐finds‐more‐clotting‐cases‐after‐jj‐vaccine‐sees‐causal‐link‐2021‐05‐12/ [Google Scholar]

- 59. Malayala Sv, Mohan G, Vasireddy D, Atluri P. Purpuric rash and thrombocytopenia after the mRNA‐1273 (Moderna) COVID‐19 vaccine [published online ahead of print March 25, 2021]. Cureus. 10.7759/cureus.14099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tarawneh O, Tarawneh H. Immune thrombocytopenia in a 22‐year‐old post Covid‐19 vaccine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5):E133‐E134. 10.1002/ajh.26106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Radwi M, Farsi S. A case report of acquired haemophilia following COVID‐19 vaccine [published online ahead of print March 30, 2021]. J Thromb Haemost. 10.1111/jth.15291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tarawneh O, Tarawneh H. Immune thrombocytopenia in a 22‐year‐old post Covid‐19 vaccine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5):E133‐E134. 10.1002/ajh.26106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Toom S, Wolf B, Avula A, Peeke S, Becker K. Familial thrombocytopenia flare‐up following the first dose of mRNA‐1273 Covid‐19 vaccine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5). 10.1002/ajh.26128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Malayala SV, Mohan G, Vasireddy D, Atluri P. Purpuric rash and thrombocytopenia after the mRNA‐1273 (Moderna) COVID‐19 vaccine. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e14099. 10.7759/cureus.14099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. See I, Su JR, Lale A, et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, march 2 to April 21, 2021 [published online ahead of print April 30, 2021]. J Am Med Assoc. 10.1001/jama.2021.7517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Haakonsen HB, Nystedt A. Deep vein thrombosis more than two weeks after vaccination against COVID‐19. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2021;141. 10.4045/tidsskr.21.0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tiede A, Sachs UJ, Czwalinna A, et al. Prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia after COVID‐19 vaccine [published online ahead of print April 28, 2021]. Blood. 10.1182/blood.2021011958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Thaler J, Ay C, Gleixner Kv, et al. Successful treatment of vaccine‐induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT) [published online ahead of print April 20, 2021]. J Thromb Haemost. 10.1111/jth.15346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Scully M, Singh D, Lown R, et al. Pathologic antibodies to platelet factor 4 after ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 vaccination [published online ahead of print April 20, 2021]. N. Engl J Med. 10.1056/NEJMoa2105385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mehta PR, Apap Mangion S, Benger M, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after COVID‐19 vaccination – a report of two UK cases [published online ahead of print April 20, 2021]. Brain Behav Immun. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Castelli GP, Pognani C, Sozzi C, Franchini M, Vivona L. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with thrombocytopenia post‐vaccination for COVID‐19. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):137. 10.1186/s13054-021-03572-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Blauenfeldt RA, Kristensen SR, Ernstsen SL, Kristensen CCH, Simonsen CZ, Hvas A‐M. Thrombocytopenia with acute ischemic stroke and bleeding in a patient newly vaccinated with an adenoviral vector‐based COVID‐19 vaccine [published online ahead of print April 20, 2021]. J Thromb Haemost. 10.1111/jth.15347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bjørnstad‐Tuveng TH, Rudjord A, Anker P. Fatal hjerneblødning etter Covid‐19‐vaksine [published online ahead of print 2021]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 10.4045/tidsskr.21.0312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Stratton K, Ford A, Rusch E, Clayton EW. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. National Academies Press; 2012. 10.17226/13164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bogdano G, Bogdano I, Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Cutaneous adverse effects of the available COVID‐19 vaccines [published online ahead of print April 2021]. Clin Dermatol. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Manolis TA, Manolis AA, Apostolopoulos EJ, Melita H, Manolis AS. Cardiovascular complications of sleep disorders: a better night's sleep for a healthier heart/from bench to bedside. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2020;19(2):210‐232. 10.2174/1570161118666200325102411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Jacobson BF, Schapkaitz E, Mer M, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vaccine‐induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia [published online ahead of print 2021]. S Afr Med J. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. On behalf of the American Heart association/American stroke association/stroke Council leadership. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with vaccine‐induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia [published online ahead of print April 29, 2021]. Stroke. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Karnam A, Lacroix‐Desmazes S, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. Vaccine‐induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT): consider IVIG batch in the treatment [published online ahead of print May 1, 2021]. J Thromb Haemost. 10.1111/jth.15361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.