Abstract

Background

Patients on kidney replacement therapy (KRT) are at very high risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The triage pathway for KRT patients presenting to hospitals with varying severity of COVID-19 illness remains ill-defined. We studied the clinical characteristics of patients at initial and subsequent hospital presentations and the impact on patient outcomes.

Methods

The European Renal Association COVID-19 Database (ERACODA) was analysed for clinical and laboratory features of 1423 KRT patients with COVID-19 either hospitalized or non-hospitalized at initial triage and those re-presenting a second time. Predictors of outcomes (hospitalization, 28-day mortality) were then determined for all those not hospitalized at initial triage.

Results

Among 1423 KRT patients with COVID-19 [haemodialysis (HD), n = 1017; transplant, n = 406), 25% (n = 355) were not hospitalized at first presentation due to mild illness (30% HD, 13% transplant). Of the non-hospitalized patients, only 10% (n = 36) re-presented a second time, with a 5-day median interval between the two presentations (interquartile range 2–7 days). Patients who re-presented had worsening respiratory symptoms, a decrease in oxygen saturation (97% versus 90%) and an increase in C-reactive protein (26 versus 73 mg/L) and were older (72 vs 63 years) compared with those who did not return a second time. The 28-day mortality between early admission (at first presentation) and deferred admission (at second presentation) was not significantly different (29% versus 25%; P = 0.6). Older age, prior smoking history, higher clinical frailty score and self-reported shortness of breath at first presentation were identified as risk predictors of mortality when re-presenting after discharge at initial triage.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that KRT patients with COVID-19 and mild illness can be managed effectively with supported outpatient care and with vigilance of respiratory symptoms, especially in those with risk factors for poor outcomes. Our findings support a risk-stratified clinical approach to admissions and discharges of KRT patients presenting with COVID-19 to aid clinical triage and optimize resource utilization during the ongoing pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, dialysis, kidney, mortality, second presentation, transplantation

KEY LEARNING POINTS

What is already known about this subject?

The clinical triage pathway for kidney replacement therapy (KRT) patients presenting with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) illness of varying severity has not been well defined. In the current phase of the pandemic, kidney patients are at high risk and present with varying degrees of severity. The ongoing pandemic has placed a major strain on hospital resources and clinical pathways, affecting overall care. The European Renal Association COVID-19 Database is a comprehensive pan-European multicentre registry with prospective data collection on COVID-19.

What this study adds?

This study focuses specifically on patients who were not admitted on initial presentation but re-presented to hospitals a second time and compares clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalization and 28-day mortality with other cohorts. Such a large, multicentre dataset on this topic has not been presented to our knowledge.

The study informs the outcome predictors for those admitted on second presentation and their clinical characteristics, indicating how to clinically risk stratify kidney patients safely on initial triage. This provides evidence, reassurance for clinicians and clinical practice parameters on the basis of which such patients with varying COVID-19 severity can be managed when presenting to hospitals.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

This study will help in attaining optimal hospital resource utilization for COVID-19 and also create capacity for treating non-COVID-related illness in kidney patients. This is impoortant information from COVID-19 Wave 1 and such knowledge transfer will support the restoration plan for renal services.

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused devastation to human lives and major disruptions of healthcare systems around the world. Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) on kidney replacement therapy (KRT) with dialysis or transplantation have been identified as specifically vulnerable groups [1]. If infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), these patients often require admission, high-intensity in-patient care and major utilization of hospital resources. However, the optimal care pathway for KRT patients presenting with varying severity of COVID-19 was not well defined.

While 80% of patients with COVID-19 have mild symptoms, ~10–20% of patients can develop severe disease [2]. Understanding the factors associated with progression of symptoms from the asymptomatic stage through to severe illness is essential for developing efficient and appropriate clinical triage systems. Avoidance of unnecessary hospitalizations, when clinically appropriate and safe, will offer protection for COVID-19 patients from potential exposure to hospital-acquired infections, minimize the risk of transmitting COVID-19 infections to others, allow continuation of standard and routine care, cause less disruption to patient lives and avoid overwhelming the healthcare system. There is limited information on risk factors that precipitate the need for hospital admission, worsening of symptoms following discharge and readmission outcomes in KRT patients with COVID-19. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with mild–moderate disease who are not hospitalized have been scarcely reported in the literature [3]. As the pandemic is sustained through a second and possible future waves, with a simultaneous increase in identification rates from enhanced testing and continued disruption of routine care, we urgently need to establish optimum triage tools to support decision making on hospitalization of KRT patients affected by COVID-19.

We analysed the data of patients receiving KRT who presented with COVID-19. Clinical features, laboratory results and outcomes of hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients at first presentation were studied and compared with characteristics of patients who returned for a second assessment. In addition, we identified predictors of subsequent admission and poor outcomes in those not admitted at their initial presentation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This observational study used data from the European Renal Association COVID-19 Database (ERACODA), which was established in March 2020 [4]. This initiative is endorsed by the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplantation Association (ERA-EDTA) and currently involves the cooperation of >200 physicians representing 130 centres in 31 countries, mostly in Europe and bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Data were collected on adult (≥18 years of age) patients with kidney failure treated with either long-term dialysis or a functioning kidney allograft. Patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 illness based on a positive result on a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens and/or compatible findings on computed tomography (CT) scan of the lungs. Data were gathered from outpatients as well as hospitalized patients. Physicians responsible for the care of these patients registered detailed demographic and clinical data, including information pertaining to disease severity, treatment and outcomes.

The ERACODA is hosted at the University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. Data are recorded using REDCap software (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA) [4]. Patient-identifiable information was stripped from each record and data were stored pseudonymized. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Groningen, who deemed the collection and analysis of data exempt from ethics review as per the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

Data collection

For the current study, all patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis between 1 February and 30 June 2020 with complete clinical datasets on hospitalizations and Day 28 outcomes were included in the analysis. Detailed information was collected on patient characteristics (including age, sex, race, frailty score, comorbidities, hospitalization and medication use) and COVID-19-related characteristics (reason for COVID-19 screening, presenting symptoms, vital signs and laboratory test results) at presentation. Frailty was assessed on a scale of 1–9 based on the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) [5]. The CFS uses clinical descriptors and pictographs to generate a frailty score for a patient, with a score of 1 representing very fit and a score of 9 representing a terminally ill patient. Comorbidities were recorded from patient records and obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2. Information was also collected on practical and logistic considerations, which mainly referred to organizational and local infrastructure constraints. We kept the definition broad to tease out the proportion of patients where decision making for clinical triage was based on patient and disease characteristics alone.

Statistical analysis

First, we examined characteristics of hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients at their first and second presentations. Second, we assessed characteristics of patients who were not admitted to the hospital initially but presented a few days later. To assess the disease course, we compared characteristics of the first and second presentations of those patients who presented twice. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as median with interquartile range (IQR) in case of a non-normal distribution. Categorical data are presented as percentages. Characteristics were compared between groups using Student’s t test for continuous variables (Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data) and Pearson chi-square for categorical variables.

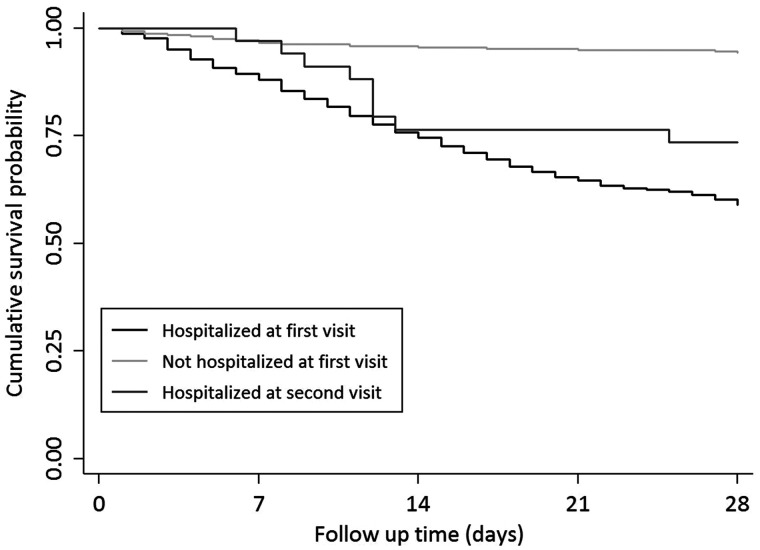

To examine 28-day mortality, cumulative survival probabilities were plotted on Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using logrank tests for three groups of patients: those hospitalized at the first visit, those not hospitalized at the first visit who did not return for a second visit and those not hospitalized at the first visit who returned for a second visit.

For those patients who were discharged after the first presentation, we identified predictors of 28-day mortality, hospitalization and second presentation using a backward elimination procedure. For 28-day mortality, this was done using Cox proportional hazards regression, whereas predictors for hospitalization and second presentation were identified using a Fine and Gray competing risk model to account for the competing risk of mortality [6]. Candidate predictors were selected in a two-stage process. First, candidate factors were selected based on clinical knowledge. These factors include age, sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, frailty score, X-ray finding, CT scan finding, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, lung disease, active malignancy, autoimmune disease, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) use, type of KRT (dialysis/transplant), COVID-19-related symptoms and vital signs, including cough, fever, shortness of breath, headache, diarrhoea, nausea/vomiting, temperature, oxygen saturation, respiration rate, pulse rate, lymphocyte count and C-reactive protein (CRP). Subsequently, each of these variables was examined in a univariable analysis and those with a P-value <0.1 were considered candidate predictors for the multivariable model. Those variables with a P-value <0.2 in the multivariable model were identified as predictors and were included in the final model [7, 8].

All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A two-sided P-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

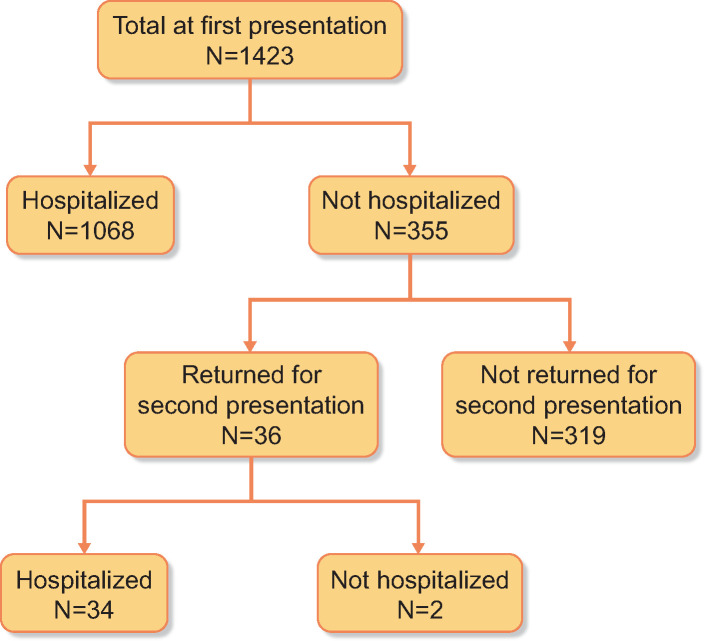

A total of 1596 patients on KRT presented for evaluation of COVID-19 symptoms between 1 February and 30 June 2020. After excluding patients with missing information on hospitalization (n = 27), 28-day clinical status (n = 121) or both (n = 25), 1423 patients were included for analysis. Of these patients, at first presentation, 1068 were hospitalized and 355 were not hospitalized. Among the 355 patients not hospitalized at first presentation, 36 patients returned for a second presentation and 34 of them were hospitalized (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart for patient presentation and hospitalization.

Patient characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the study are shown in Table 1. On average, patients were 64 years old and the majority were male (61%). A total of 406 (29%) patients were kidney transplant recipients and 1017 (71%) were dialysis patients [99% haemodialysis (HD) and 1% peritoneal dialysis (PD)]. From this cohort of 1423 patients, 355 patients (25%) were not admitted at first presentation [13% (n = 53) of kidney transplant patients and 30% (n = 302) of dialysis patients]. The gender distribution, age and frailty score of these 355 non-hospitalized patients were similar to those of patients who were hospitalized after their initial assessment. However, the non-hospitalized patients had lower CRP values (13 versus 38 mg/L) and less frequent pulmonary symptoms including cough (38% versus 58%) and shortness of breath (11% versus 44%) and fewer abnormalities on chest X-ray (9% versus 44%) or CT scan (6% versus 41%). X-ray was not performed in 74% of non-hospitalized and 39% of hospitalized patients and CT scan was not performed in 81% of non-hospitalized and 68% of hospitalized patients on their first presentation. The median duration of in-patient stays among those hospitalized was 15 days (IQR 9–23). Only five patients were discharged alive within 24 h of hospital admission.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all patients at first presentation stratified according to their hospital admission status

| Hospitalization at first presentation |

Not hospitalized at first presentation (n = 355) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (N = 1423) | Yes (n = 1068) | No (n = 355) | P-value | Returned for second presentation (n = 36) | Did not return for second presentation (n = 319) | P-value |

| Sex (male), % | 61 | 62 | 56 | 0.06 | 64 | 55 | 0.33 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 64 ± 15 | 64 ± 14 | 64 ± 16 | 0.53 | 72 ± 14 | 63 ± 16 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 6 | 0.67 | 27 ± 4 | 27 ± 6 | 0.86 |

| Race, % | 0.05 | 0.93 | |||||

| Asian | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | ||

| Black or African descent | 6 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 7 | ||

| White or Caucasian | 86 | 86 | 86 | 83 | 86 | ||

| Other or unknown | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Tobacco use, % | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| Current | 6 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Prior | 22 | 22 | 19 | 42 | 17 | ||

| Never | 45 | 47 | 39 | 42 | 39 | ||

| Unknown | 28 | 24 | 37 | 17 | 40 | ||

| CFS (AU), mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 0.74 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 0.44 |

| Patient identification, % | <0.001 | 0.03 | |||||

| Symptoms only | 73 | 75 | 66 | 85 | 64 | ||

| Symptoms and contact | 14 | 15 | 11 | 15 | 10 | ||

| No symptoms but contact | 5 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Routine screening | 8 | 5 | 17 | 0 | 20 | ||

| COVID-19 test result, % | |||||||

| Positive | 94 | 92 | 97 | 92 | 98 | ||

| Negative | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Intermediate/unknown | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | – | ||

| Abnormality on X-ray (yes), % | 35 | 44 | 9 | <0.001 | 14 | 8 | 0.03 |

| Abnormality on CT scan (yes), % | 32 | 41 | 6 | <0.001 | 8 | 5 | 0.35 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||||||

| Obesity | 23 | 23 | 21 | 0.45 | 15 | 22 | 0.34 |

| Hypertension | 83 | 83 | 84 | 0.79 | 83 | 84 | 0.95 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 | 40 | 39 | 0.62 | 44 | 38 | 0.45 |

| Coronary artery disease | 29 | 30 | 28 | 0.50 | 33 | 27 | 0.44 |

| Heart failure | 19 | 21 | 14 | 0.007 | 17 | 14 | 0.68 |

| Chronic lung disease | 12 | 12 | 11 | 0.55 | 17 | 11 | 0.28 |

| Active malignancy | 6 | 7 | 3 | 0.01 | 8 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Autoimmune disease | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0.31 | 8 | 3 | 0.11 |

| Primary kidney disease, % | |||||||

| Primary glomerulonephritis | 16 | 16 | 13 | 0.12 | 14 | 13 | 0.81 |

| Pyelonephritis | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0.20 | 0 | 2 | 0.45 |

| Interstitial nephritis | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0.10 | 3 | 3 | 0.92 |

| Hereditary kidney disease | 10 | 10 | 12 | 0.24 | 9 | 12 | 0.53 |

| Congenital diseases | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.26 | 0 | 3 | 0.28 |

| Vascular diseases | 13 | 12 | 14 | 0.47 | 17 | 14 | 0.55 |

| Secondary glomerular disease | 7 | 7 | 10 | 0.06 | 11 | 10 | 0.74 |

| Diabetic kidney disease | 21 | 22 | 19 | 0.27 | 34 | 17 | 0.02 |

| Other | 14 | 13 | 18 | 0.02 | 6 | 19 | 0.05 |

| Unknown | 10 | 11 | 8 | 0.09 | 6 | 8 | 0.63 |

| Dialysis (yes), % | 71 | 67 | 85 | <0.001 | 78 | 86 | 0.19 |

| HDa | 99 | 99 | 99 | 0.29 | 100 | 99 | 0.57 |

| PDa | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Residual diuresis ≥200 mL/daya | 32 | 33 | 31 | 0.002 | 46 | 29 | 0.006 |

| Transplant waiting list statusa, % | 0.001 | 0.12 | |||||

| Active on waiting list | 11 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 11 | ||

| In preparation | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | ||

| Temporarily not on list | 9 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 6 | ||

| Not transplantable | 63 | 64 | 61 | 82 | 58 | ||

| Unknown | 7 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Transplantation (yes), % | 29 | 34 | 15 | 22 | 14 | ||

| Time since transplantationb, % | 0.12 | 0.04 | |||||

| <1 year | 7 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 13 | ||

| 1–5 years | 32 | 31 | 42 | 50 | 40 | ||

| >5 years | 61 | 61 | 57 | 38 | 60 | ||

| Medication, % | |||||||

| ACE inhibitor use (yes) | 16 | 17 | 14 | 0.32 | 19 | 11 | 0.007 |

| ARB inhibitor use (yes) | 16 | 15 | 19 | 0.12 | 22 | 15 | 0.014 |

| Use of immunosuppressive medication, % | |||||||

| Prednisone | 85 | 86 | 84 | 0.61 | 92 | 82 | 0.41 |

| Tacrolimus | 67 | 67 | 66 | 0.83 | 67 | 66 | 0.97 |

| Cyclosporine | 10 | 11 | 7 | 0.45 | 0 | 8 | 0.31 |

| Mycophenolate | 58 | 58 | 55 | 0.63 | 50 | 56 | 0.68 |

| Azathioprine | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.82 | 0 | 5 | 0.44 |

| mTOR inhibitor | 12 | 12 | 11 | 0.81 | 17 | 10 | 0.49 |

| Disease characteristics | |||||||

| Days from symptoms onset, median (IQR) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–5) | 1 (0–3) | <0.001 | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | 0.28 |

| Presenting symptoms, % | |||||||

| Sore throat | 12 | 13 | 9 | <0.001 | 17 | 8 | 0.04 |

| Cough | 53 | 58 | 38 | <0.001 | 56 | 36 | 0.009 |

| Shortness of breath | 36 | 44 | 11 | <0.001 | 22 | 10 | 0.005 |

| Fever | 62 | 68 | 44 | <0.001 | 50 | 43 | 0.007 |

| Headache | 11 | 13 | 8 | <0.001 | 14 | 8 | 0.006 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 12 | 13 | 7 | <0.001 | 6 | 7 | 0.004 |

| Diarrhoea | 16 | 18 | 11 | <0.001 | 14 | 10 | 0.008 |

| Myalgia or arthralgia | 21 | 23 | 16 | <0.001 | 26 | 15 | 0.003 |

| Vital signs, mean ± SD | |||||||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.5 ± 1.1 | 37.6 ± 1.1 | 37.2 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 37.3 ± 1.2 | 37.2 ± 1.0 | 0.55 |

| Respiration rate (per min) | 20 ± 6 | 20 ± 6 | 17 ± 4 | <0.001 | 17 ± 4 | 17 ± 3 | 0.85 |

| O2 saturation room air (%) | 94 ± 6 | 93 ± 6 | 97 ± 3 | <0.001 | 97 ± 3 | 97 ± 3 | 0.60 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 135 ± 25 | 135 ± 25 | 137 ± 24 | 0.14 | 129 ± 22 | 139 ± 25 | 0.04 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 75 ± 15 | 76 ± 15 | 73 ± 15 | 0.05 | 69 ± 15 | 74 ± 15 | 0.07 |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 84 ± 16 | 85 ± 16 | 77 ± 13 | <0.001 | 73 ± 11 | 77 ± 14 | 0.13 |

| Laboratory test results | |||||||

| Creatinine increase (>25%)b | 30 | 33 | 8 | <0.001 | 25 | 12 | 0.007 |

| Lymphocytes (×1000/µL), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.87 | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.41 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 31 (8–84) | 38 (10–95) | 13 (3–43) | <0.001 | 26 (6–58) | 12 (2–36) | 0.02 |

Groups were compared using Student’s t, Wilcoxon or chi-square test as appropriate. Obesity is defined as BMI >30 kg/m2. O2, oxygen; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin.

In dialysis patients only.

In transplant recipients only.

Second presentation

Thirty-six of the 355 patients (10%) who were not hospitalized at their first assessment presented for a second time with clinical illness (Table 1). Of these 36 patients, the numbers of transplant and dialysis recipients were 8 (22%) and 28 (78%), respectively. Among the 355 patients who were not hospitalized initially, practical and logistical considerations precluded first hospital admission for 9% of patients who returned for a second assessment, compared with 1% of those who did not return (Supplementary data, Table S1). Supplementary data, Figure S1 shows the distribution of patients with a second presentation according to their country of residence. Second attendance cases were ≤5% of the reported cases in each country, except for France, where 24% of the reported cases returned for a second assessment (Supplementary data, Table S2). The median time interval between the first and second presentation was 5 days (IQR 2–7) (Supplementary data, Figure S2). Patients who presented a second time were older, more often had a history of prior tobacco use and more frequently had diabetic kidney disease compared with those who did not re-present at the hospital (Table 1). Furthermore, these patients more often had pulmonary symptoms including cough (56% versus 36%) and shortness of breath (22% versus 10%), abnormalities on chest X-ray (14% versus 8%), lower mean systolic blood pressure (129 ± 26 versus 139 ± 25 mmHg) and a higher median CRP value [26 mg/L (IQR 6–58) versus 12 (2–36)] on initial attendance compared with those patients who did not return for a second presentation.

Evolution of symptoms, vital signs and laboratory results from first hospital attendance to the second presentation

Patients who sought healthcare input for a second time had clinical symptoms characterized by worsening of respiratory illness, with cough, shortness of breath and a decline in their vital parameters, namely an increase in respiration rate, a decrease in blood oxygen saturation (from 97% to 90%) and an increase in pulse rate (from 73 to 78 bpm). Temperature and blood pressure did not change significantly between the first and second presentations (Table 2). An increase in CRP (from 26 to 73 mg/L) was also noted at the second presentation.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics at first and second presentation in those who presented on two separate occasions (N = 36)

| Characteristics | Patient characteristics by presentation |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| First presentation (n = 36) | Second presentation (n = 36) | P-value | |

| Patient identification, n | 0.03 | ||

| Symptoms only | 85 | 93 | |

| Symptoms and contact | 15 | 4 | |

| No symptoms but contact | 0 | 0 | |

| Routine screening | 0 | 4 | |

| Presenting symptoms, % | |||

| Sore throat | 17 | 1 | 0.41 |

| Cough | 56 | 64 | 0.18 |

| Shortness of breath | 22 | 53 | 0.002 |

| Fever | 50 | 64 | 0.13 |

| Headache | 14 | 19 | 0.16 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 6 | 19 | 0.03 |

| Diarrhoea | 14 | 25 | 0.16 |

| Myalgia or arthralgia | 26 | 25 | 0.71 |

| Vital signs, mean ± SD | |||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.3 ± 1.2 | 37.6 ± 0.9 | 0.19 |

| Respiration rate (per min) | 17 ± 4 | 23 ± 9 | 0.003 |

| O2 saturation room air (%) | 97 ± 3 | 90 ± 10 | 0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 129 ± 22 | 133 ± 26 | 0.44 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 69 ± 15 | 70 ± 14 | 0.67 |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 73 ± 11 | 78 ± 13 | 0.04 |

| Laboratory test results | |||

| Creatinine increase (>25%)a | 25 | 62 | 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes (×1000/µL), median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–0.9) | 0.02 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 26 (6–58) | 73 (21–151) | <0.001 |

Groups were compared using Student’s t, Wilcoxon or chi-square test as appropriate. O2, oxygen; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute. aIn transplant recipients only.

Comparison of characteristics of patients hospitalized at their first presentation and at baseline for those patients who returned for a second hospital episode

Compared with patients admitted after their initial consultation, those who were admitted later were older, more often had prior tobacco use and at the time of their initial assessment, less often had shortness of breath and fever, a lower respiratory rate, higher oxygen saturation, lower diastolic blood pressure and heart rate and less often had an abnormality on chest X-ray or CT scan (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients admitted to hospital after the first and second presentation

| Characteristics | Admitted after first presentation (n = 1068) |

Admitted after second presentation (n = 34) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), % | 62 | 62 | 0.97 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 64 ± 14 | 71 ± 14 | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 0.83 |

| Race, % | 0.49 | ||

| Asian | 3 | 6 | |

| Black or African descent | 5 | 9 | |

| White or Caucasian | 86 | 82 | |

| Other or unknown | 6 | 3 | |

| Tobacco use, % | 0.03 | ||

| Current | 7 | 0 | |

| Prior | 22 | 41 | |

| Never | 47 | 44 | |

| Unknown | 24 | 15 | |

| CFS (AU), mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 0.34 |

| Patient identification, n | 0.37 | ||

| Symptoms only | 75 | 88 | |

| Symptoms and contact | 15 | 12 | |

| No symptoms but contact | 5 | 0 | |

| Routine screening | 5 | 0 | |

| COVID-19 test result, n | 0.77 | ||

| Positive | 92 | 91 | |

| Negative | 5 | 6 | |

| Intermediate/unknown | 2 | 3 | |

| Abnormality on X-ray (yes), n | 44 | 15 | 0.002 |

| Abnormality on CT scan (yes), n | 41 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||

| Obesity | 23 | 16 | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 83 | 82 | 0.92 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 | 47 | 0.41 |

| Coronary artery disease | 30 | 35 | 0.49 |

| Heart failure | 21 | 18 | 0.65 |

| Chronic lung disease | 12 | 18 | 0.37 |

| Active malignancy | 7 | 9 | 0.69 |

| Autoimmune disease | 5 | 9 | 0.31 |

| Primary kidney disease, % | |||

| Primary glomerulonephritis | 16 | 15 | 0.84 |

| Pyelonephritis | 3 | 0 | 0.34 |

| Interstitial nephritis | 5 | 3 | 0.66 |

| Hereditary kidney disease | 10 | 9 | 0.92 |

| Congenital diseases | 2 | 0 | 0.43 |

| Vascular diseases | 12 | 18 | 0.32 |

| Secondary glomerular disease | 7 | 9 | 0.59 |

| Diabetic kidney disease | 22 | 33 | 0.12 |

| Other | 13 | 6 | 0.25 |

| Unknown | 11 | 6 | 0.37 |

| Dialysis (yes), % | 67 | 79 | 0.13 |

| HDa | 99 | 100 | 0.73 |

| PDa | 1 | 0 | |

| Residual diuresis ≥200 mL/daya | 33 | 48 | 0.08 |

| Transplant waiting list statusa, % | 0.39 | ||

| Active on waiting list | 11 | 7 | |

| In preparation | 10 | 7 | |

| Temporarily not on list | 10 | 4 | |

| Not transplantable | 64 | 81 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 0 | |

| Kidney transplant (yes), % | 34 | 21 | |

| Time since transplantationb, % | 0.57 | ||

| <1 year | 8 | 14 | |

| 1–5 years | 31 | 43 | |

| >5 years | 61 | 43 | |

| Medication, % | |||

| ACE inhibitor use (yes) | 17 | 21 | 0.37 |

| ARB inhibitor use (yes) | 15 | 24 | 0.18 |

| Immunosuppressant use, % | |||

| Prednisone | 86 | 91 | 0.63 |

| Tacrolimus | 67 | 64 | 0.79 |

| Cyclosporine | 11 | 0 | 0.49 |

| Mycophenolate | 58 | 45 | 0.39 |

| Azathioprine | 4 | 0 | 0.75 |

| mTOR inhibitor | 12 | 18 | 0.81 |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Days from symptom onset, median (IQR) | 2 (0–5) | 1 (0–4) | 0.32 |

| Presenting symptoms, % | |||

| Sore throat | 13 | 18 | 0.63 |

| Cough | 58 | 56 | 0.93 |

| Shortness of breath | 44 | 24 | 0.05 |

| Fever | 68 | 50 | 0.02 |

| Headache | 13 | 15 | 0.67 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 13 | 6 | 0.21 |

| Diarrhoea | 18 | 15 | 0.37 |

| Myalgia or arthralgia | 23 | 27 | 0.28 |

| Vital signs, mean ± SD | |||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.6 ± 1.1 | 37.4 ± 1.2 | 0.21 |

| Respiration rate (per min) | 20 ± 6 | 17 ± 4 | 0.006 |

| O2 saturation room air (%) | 93 ± 6 | 96 ± 3 | 0.003 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 135 ± 25 | 129 ± 22 | 0.19 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 76 ± 15 | 69 ± 15 | 0.009 |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 85 ± 16 | 74 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory test results | |||

| Creatinine increase (>25%)b | 33 | 25 | 0.52 |

| Lymphocytes (×1000/µL), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.42 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 38 (10–95) | 29 (5–63) | 0.14 |

Groups were compared using Student’s t, Wilcoxon or chi-square test as appropriate. Obesity is defined as BMI >30 kg/m2. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; O2, oxygen; SBP, systolic blood pressure; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin.

In dialysis patients only.

In transplant recipients only.

28-day mortality

A total of 314 of 1068 patients (29%) died among those who were admitted to the hospital at first presentation. Nine of 36 patients (25%) who were not hospitalized at first presentation died after they returned for admission, whereas 19 of 319 patients (6%) died who were not hospitalized initially but also did not return for a second assessment. The mortality rate in those who were hospitalized at the second presentation did not differ from that of patients who were admitted at the first presentation (P = 0.61). However, the mortality rate was signficantly lower among patients who were not hospitalized at the first visit and did not return for reassessment (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Mortality also did not differ between those who were hospitalized at the first presentation and those who returned for a second presentation (29% versus 25%; P = 0.60). Among those who had delayed hospital admission, all nine deaths occurred in HD patients. KRT modality did not appear as a strong predictor in the multivariate model.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 28-day mortality (from date of first presentation)*. (1) Hospitalized at first visit = hospitalized at first visit excluding those who were admitted also on second visit (n = 1089, events = 314). (2) Not hospitalized at first visit = not admitted on first visit and did not return for second visit (n = 319, events = 19). (3) Hospitalized at second visit = not admitted on first visit but returned for a second visit and hospitalized (n = 34, events = 9). *P value = 0.61 for cumulative survival difference between 1 and 3 and P < 0.001 for survival difference between 1 and 2 and 2 and 3.

Predictors of prognosis in those not admitted at first presentation

Older age, prior tobacco use, higher clinical frailty score, autoimmune disease and shortness of breath were identified as predictors of 28-day mortality in patients who were not hospitalized after their initial presentation with COVID-19 (Table 4). Older age, prior tobacco use and increased shortness of breath were identified as predictors of deferred hospital attendance (Supplementary data, Table S3) and hospital admission at the second assessment (Supplementary data, Table S4).

Table 4.

Predictors of 28-day mortality in those not admitted to hospital at first presentation (n = 355, events = 28) (presented as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals)

| Characteristics | Univariable | P-value | Multivariable | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | <0.001 | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 0.08 |

| Sex (male) | 1.43 (0.66–3.09) | 0.37 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White/Caucasian | Ref. | |||

| Asian | 3.04 (0.91–10.17) | 0.07 | ||

| Black/African descent | 1.10 (0.26–4.69) | 0.90 | ||

| Other/unknown | 1.32 (0.18–9.83) | 0.78 | ||

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Never | Ref. | |||

| Current | 0.98 (0.13–7.64) | 0.98 | ||

| Prior | 2.58 (1.12–5.98) | 0.027 | 2.51 (1.01–6.25) | 0.05 |

| Unknown | 0.52 (0.18–1.53) | 0.24 | ||

| CFS (AU) | 1.64 (1.31–2.07) | <0.001 | 1.41 (1.05–1.89) | 0.02 |

| X-ray abnormality (yes) | 4.08 (0.37–45.04) | 0.25 | ||

| CT scan abnormality (yes) | – | – | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) | 0.17 | ||

| Diabetes (yes) | 1.62 (0.77–3.41) | 0.20 | ||

| Hypertension (yes) | 0.70 (0.28–1.73) | 0.44 | ||

| Lung disease (yes) | 1.74 (0.66–4.59) | 0.26 | ||

| Active malignancy | 2.50 (0.59–10.53) | 0.21 | ||

| Autoimmune disease | 4.73 (1.64–13.65) | 0.004 | 3.85 (0.74–19.97) | 0.11 |

| ARB use (yes) | 1.75 (0.77–3.98) | 0.18 | ||

| ACEi use (yes) | 1.02 (0.35–2.94) | 0.97 | ||

| Dialysis (versus transplant) | 4.91 (0.67–36.15) | 0.118 | ||

| Days between two presentations | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.32 | ||

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| COVID-19-related symptoms | ||||

| Cough (yes) | 1.58 (0.70–3.55) | 0.27 | ||

| Fever (yes) | 1.24 (0.58–2.68) | 0.58 | ||

| Shortness of breath (yes) | 3.26 (1.39–7.62) | 0.006 | 3.23 (1.31–7.96) | 0.01 |

| Headache (yes) | 1.83 (0.62–5.40) | 0.26 | ||

| Diarrhoea (yes) | 1.25 (0.43–3.65) | 0.68 | ||

| Nausea/vomiting (yes) | – | |||

| Vital signs | ||||

| Temperature (°C) | 1.16 (0.77–1.74) | 0.48 | ||

| Respiration rate (per min) | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | 0.24 | ||

| O2 saturation (%) | 0.87 (0.78–0.98) | 0.017 | ||

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) | 0.84 | ||

| Laboratory test results | ||||

| Lymphocyte (×1000/µL) | 1.00 (0.76–1.31) | 0.99 | ||

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.36 | ||

bpm, beats per minute; O2, oxygen.

DISCUSSION

In this study from the ERACODA, we found that 25% of patients on KRT who presented with a COVID-19 diagnosis did not require hospitalization, due to milder clinical symptoms. Only 10% of these patients returned to the hospital with progressive illness and required hospitalization after a second clinical assessment. For most of these patients, the return to the hospital was necessary within 1 week from their initial attendance. Reassuringly, the 28-day survival of those who had a deferred hospital admission did not differ from those who were admitted at their initial clinical presentation. Our data indicate that stratification for admitting KRT patients presenting with COVID-19 can be done safely based on clinical parameters.

These findings will affect our approach to management of these patients. Hospital bed occupancy due to patients with COVID-19 may increase during the second and third waves of the pandemic while awaiting the full effects of vaccination programmes. It may be necessary to clinically triage patients presenting with a COVID-19 diagnosis. This study suggests that, despite being an extremely vulnerable group, a clinical risk stratification strategy to determine the optimal location of care for patients receiving KRT presenting with COVID-19 can be justified. Those with mild symptoms or minor derangements of diagnostic tests may be managed as outpatients at home or in dedicated dialysis facilities or clinics. However, it is essential to ensure this is supported by follow-up with teams dedicated to deliver this remotely or face-to-face, during their dialysis visits or close follow-up at the outpatient wards for kidney transplant recipients. Our study identified that older age, frailty, a prior history of smoking and self-reported shortness of breath are associated with hospital re-attendance in patients not hospitalized after the initial presentation. Older age and frailty were previously recognized as predictors of hospitalization of HD patients with COVID-19 infection [9]. The possibility of predisposition to COVID-19 pneumonia in the context of underlying smoking-induced lung damage is high. Bacterial co-infection in the general population is believed to be less frequent (3.5%), but in hospitalized patients, the risk of secondary bacterial infection is significant at 14.3% and many patients receive antibiotics, with worsening respiratory illness [10]. These reports justify closer outpatient monitoring of risk factors invulnerable KRT patients.

Outpatient management of the general population with COVID-19, after presenting in Emergency Departments (EDs), has been primarily examined in patients who are typically young and not multimorbid, unlike the dialysis cohort [11]. In these low-risk patients, a minority require hospitalization after being discharged home from the ED. ED revisits occurred for 13.7% of patients, which is similar to our study. The inpatient admission rate at 30 days was 4.6%, with 0.7% requiring intensive care [11]. The importance of early and optimum outpatient care of COVID-19 patients is now recognized, based on the current understanding of the biophysical distribution of COVID-19 viral particles. It is well-recognized that COVID-19 exists in the exhaled air of an infected person, raising the risk of re-inoculation. In hospitalized patients, negative-pressure rooms are used to reduce the spread of communicable diseases outside of the room. In patients treated outside the hospital, this could be achieved by spending time outdoors or indoors with windows open. Oxygen, anti-thrombotic therapy and new or repurposed immunomodulatory and antiviral drugs are also in development or in trials to help facilitate outpatient management to the extent possible.

At first presentation with COVID-19, the proportion of transplant patients admitted was higher than that at the second presentation (33% versus 21%), possibly deemed at higer risk or suggesting a potential lag in the evolution of symptoms in the HD cohort. This may also be due to potentially earlier identification of HD patients compared with transplant patients, as a larger proportion of cases on HD were identified through routine screening. Alternatively, this could also imply a lower threshold for admission of home-based transplant patients in contrast to HD patients who routinely attend for in-centre dialysis. In a publication from Spain that reported on the course of a small cohort of HD patients, a mild clinical presentation at diagnosis did not necessarily guarantee a benign course, as all patients ultimately developed radiological abnormalities—hence the need for a robust pathway of monitoring if discharged at the outset [12]. The safety of outpatient management of HD recipients was reported in another study by Medjeral-Thomas et al. [9]. The authors found progressively decreasing blood oxygen saturations over the first three dialysis sessions in the cohorts that progressed to future hospital admission or death [9]. This finding is replicated in our study, where hypoxia was evident at the second presentation of patients who had satisfactory vital parameters a few days earlier.

In the transplantation cohort, there have been reports of successful management of patients as outpatients through a systematic strategy to triage outpatient and inpatient care. In one study, symptom resolution was achieved without the need for hospitalization through early management of bacterial infections and minor adjustment of immunosuppression [13, 14].

The 28-day mortality of KRT recipients has been reported in the published literature to vary from 15% to 29% [13–15]. This corresponds with the 28-day mortality for patients hospitalized at the first (29%) and the second presentation (25%) in our study. Patients who did not return for a second presentation had a 28-day mortality of 6%. The causes of death in the latter instances are not known. In a large study from a major healthcare system in the USA, the mortality of patients with COVID-19 was predicted by a three-variable prediction model. These were older age, low oxygen saturation during the encounter and the type of encounter (inpatient versus outpatient versus telehealth). In this dataset, patients who were alive were more likely to have had their initial encounter at a hospital rather than at an outpatient or telehealth setting compared with patients who died (odds ratio 15.59; P < 0.0001) [16]. This reinforces the need for close follow-up of patients if they are deemed to be safe for discharge at their first consultation, especially if they have risk factors and comorbidities.

The key strength of our study is that it was performed in real-life conditions during the first wave of the pandemic, with access to complete sociodemographic and clinical datasets from multiple centres, including admissions data such as laboratory reports, diagnostic imaging and COVID-19 treatment data. Consequently this has allowed us to analyse the risk of hospital admission related to COVID-19 adjusted for confounders, thus minimizing possible bias. Our data highlight that supported outpatient care of patients on KRT is a viable management proposition for healthcare institutions. Although the reported prognosis predictors are not modifiable, knowing them can help us prioritize initial and follow-up care for these ‘at-risk’ patient groups.

Our study has its limitations. The lack of availability of widespread antigen or antibody testing during the first wave of the pandemic and the extent of disease transmission being unclear could have led to reporting bias, as some patients may have had mild symptoms and did not present to the hospital for evaluation. This is especially true for transplant recipients. More detailed virology data with strain types and viral load may have added strength to the prognostication criteria but were unavailable at the time. The study did not collect any centre-specific protocols for referrals, admissions or discharges. However, the median time between the first and second visit was 5 days (IQR 2–7), with worsening of disease symptoms in those who returned for a second visit (Table 2). Therefore it seems unlikely that centres would have adopted protocols to discharge or arrange revisits to hospitals on an elective basis during the pandemic. Second presentations were determined mainly by disease symptoms and severity.

Balancing safe patient care with available resources remains a priority as we encounter current and subsequent waves of the pandemic. This study provides some insights for clinicians to develop and adopt strategies for patient pathways when caring for outpatient kidney transplant and dialysis recipients. As with other illnesses, individual patient circumstances and clinical judgement must be factored into the decision to admit or not to admit to the hospital at any given point in time.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Collaborators that entered data in ERACODA remain the owners of these data. The database information can therefore not be disclosed to any third party without the prior written consent of all data providers, but the database will be made available to the editorial offices of medical journals when requested. Research proposals can be submitted to the Working Group via COVID.19.KRT@umcg.nl. If deemed of interest and methodologically sound by the Working Group and Advisory Board, the analyses needed for the proposal will be carried out by the Management Team.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The ERACODA collaboration is an initiative to study the prognosis and risk factors for mortality due to COVID-19 in patients with a kidney transplant or on dialysis that is endorsed by the ERA-EDTA. The organizational structure contains a working group assisted by a management team and advisory Bbard. ERACODA Working Group members: C.F.M. Franssen, R.T. Gansevoort (coordinator), M.H. Hemmelder, L.B. Hilbrands and K.J. Jager. ERACODA Management Team members: R. Duivenvoorden, M. Noordzij and P. Vart. ERACODA Advisory Board members: D. Abramowicz, C. Basile, A. Covic, M. Crespo, Z.A. Massy, S. Mitra, E. Petridou, J.E. Sanchez and C. White. We thank all the people who entered information in ERACODA for their participation and especially all the healthcare workers who have taken care of the included COVID-19 patients. S.M. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research at Manchester, UK, and the Devices for Dignity MedTech & In vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, Sheffield, UK.

FUNDING

ERACODA received unrestricted research grants from the ERA-EDTA, the Dutch Kidney Foundation, Baxter and Sandoz.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to data collection, study design, data analysis, interpretation and drafting of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

APPENDIX 1

ERACODA Collaborators

Jeroen B. van der Net (Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht, The Netherlands); Marie Essig (Ambroise Pare Hospital, APHP Paris-Saclay University, Boulogne Billancourt, France); Peggy W. G. du Buf-Vereijken, Betty van Ginneken and Nanda Maas (Amphia Hospital, Breda, The Netherlands); Liffert Vogt, Brigit C. van Jaarsveld, Kitty J. Jager, Frederike J. Bemelman, Farah Klingenberg-Salahova, Frederiek Heenan-Vos, Marc G. Vervloet and Azam Nurmohamed (Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); Daniel Abramowicz and Sabine Verhofstede (Antwerp University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium); Omar Maoujoud (Faculty of Medicine, Avicennes Military Hospital, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech, Morocco); Thomas Malfait (AZ Delta, Roeselare, Belgium); Jana Fialova (B. Braun Avitum, Litomerice, Czech Republic); Edoardo Melilli, Alexandre Favà, Josep M. Cruzado and Nuria Montero Perez (Hospitalet de Llobregat, Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain); Joy Lips (Bernhoven Hospital, Uden, The Netherlands); Harmen Krepel (Bravis Hospital, Roosendaal/Bergen op Zoom, The Netherlands); Harun Adilovic (Cantonal Hospital Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina); Maaike Hengst (Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands); Andrzej Rydzewski (Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Interior, Warsaw, Poland); Ryszard Gellert (Centre Hospitalier du Nord, Luxembourg and Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland); João Oliveira (Centrodial, São João da Madeira, Portugal); Daniela G. Alferes (Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal); Elena V. Zakharova (City Hospital n.a. S.P. Botkin, Moscow, Russia); Patrice Max Ambuehl, Andrea Walker and Rebecca Winzeler (City Hospital Waid, Zürich, Switzerland); Fanny Lepeytre, Clémentine Rabaté and Guy Rostoker (Claude Galien Hospital Ramsay santé, Quincy-sous-Sénart, France); Sofia Marques (Clínica de Hemodiálise de Felgueiras, Felgueiras, Portugal); Tijana Azasevac (Clinical Centre of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, Serbia); Dajana Katicic (Croatian Society of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, Zagreb, Croatia); Marc ten Dam (CWZ Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands); Thilo Krüger (DaVita Geilenkirchen, Geilenkirchen, Germany); Szymon Brzosko (DaVita, Wrocław, Poland); Adriaan L. Zanen (Deventer Ziekenhuis, Deventer, The Netherlands); Susan J.J. Logtenberg (Dianet Dialysis Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands); Lutz Fricke (Dialysis Center Bochum, Bochum, Germany); Jeroen J.P. Slebe (Elyse Klinieken voor Nierzorg, Kerkrade, The Netherlands); Delphine Kemlin (Erasme Hospital, Brussels, Belgium); Jacqueline van de Wetering and Marlies E.J. Reinders (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands); Jaromir Eiselt and Lukas Kielberger (Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, Pilsen, Czech Republic); Hala S. El-Wakil (Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt); Martine A.M. Verhoeven (Franciscus Gasthuis and Vlietland, Rotterdam, The Netherlands); Cristina Canal and Carme Facundo (Fundació Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain); Ana M. Ramos (Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid, Spain); Alicja Debska-Slizien (Gdansk Medical University, Gdansk, Poland); Nicoline M.H. Veldhuizen (Gelre Hospital, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands); Eirini Tigka (General Hospital of Athens ‘G. Gennimatas’, Athens); Maria Anna Polyzou Konsta (General Hospital of Serres, Serres, Greece); Stylianos Panagoutsos (General University Hospital of Alexandroupolis, Alexandroupolis, Greece); Francesca Mallamaci, Adele Postorino and Francesco Cambareri (Grande Ospedale Metropolitano and CNR, Reggio Calabria, Italy); Adrian Covic, Irina Matceac, Ionut Nistor and Monica Cordos (Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi, Romania/Dr Ci Parhon Hospital, Iasi, Romania); J.H.M. Groeneveld and Jolanda Jousma (Haaglanden Medisch Centrum, Hague, The Netherlands); Marjolijn van Buren (Haga Hospital, Hague, The Netherlands); Fritz Diekmann (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain); Tiago Assis Pereira (Hospital Curry Cabral–Central Lisbon University Hospital Center, Lisbon, Portugal); Augusto Cesar S. Santos Jr. (HC-UFMG, CMN Contagem-MG, Unimed-BH, Contagem, Brazil); Carlos Arias-Cabrales, Marta Crespo, Laura Llinàs-Mallol, Anna Buxeda, Carla Burballa Tàrrega, Dolores Redondo-Pachon and Maria Dolores Arenas Jimenez (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain); Julia M. Hofstra (Hospital Gelderse Vallei, Ede, The Netherlands); Antonio Franco (Hospital General of Alicante, Alicante, Spain); David Arroyo and Maria Luisa Rodríguez-Ferrero (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain); Sagrario Balda Manzanos (Hospital Obispo Polanco, Salud Aragón, Spain); R. Haridian Sosa Barrios (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain); Gonçalo Ávila, Ivo Laranjinha and Catarina Mateus (Hospital de Santa Cruz, Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Ocidental, Lisboa, Portugal); Wim Lemahieu (Imelda Hospital, Bonheiden, Belgium); Karlijn Bartelet (Isala, Zwolle, The Netherlands); Ahmet Burak Dirim, Mehmet Sukru Sever, Erol Demir, Seda Şafak and Aydin Turkmen (Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey); Daan A.M.J. Hollander (Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Den Bosch, The Netherlands); Stefan Büttner (Klinikum Aschaffenburg-Alzenau, Aschaffenburg, Germany); Aiko P.J. de Vries, Soufian Meziyerh, Danny van der Helm, Marko Mallat and Hanneke Bouwsma (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands); Sivakumar Sridharan (Lister Hospital, Stevenage, UK); Kristina Petruliene (Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania); Sharon-Rose Maloney (Luzerner Kantonsspital, Luzern, Switzerland); Iris Verberk (Maasstad Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam, The Netherlands); Frank M. van der Sande and Maarten H.L. Christiaans (Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands); N. MohanKumar (Manipal Hospital, Bangalore, India); Marina Di Luca (Marche Nord Hospital, Pesaro, Italy); Serhan Z. Tuğlular (Marmara University School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey); Andrea Kramer (Martini Ziekenhuis, Groningen, The Netherlands); Charles Beerenhout (Maxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven, The Netherlands); Peter T. Luik (Meander Medisch Centrum, Amersfoort, The Netherlands); Julia Kerschbaum (Austrian Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Rohr, Austria); Martin Tiefenthaler (Medical University Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria); Bruno Watschinger (Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria); Aaltje Y. Adema (Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands); Vadim A. Stepanov and Alexey B. Zulkarnaev (Moscow Regional Research and Clinical Institute, Moscow, Russia); Kultigin Turkmen (Meram School of Medicine, Necmettin Erbakan University, Konya, Turkey); Anselm Fliedner (Nierenzentrum Reutlingen-Tübingen, Reutlingen, Germany); Anders Åsberg and Geir Mjoen (Norwegian Renal Registry, Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, Olso, Norway); Hitoshi Miyasato (Okinawa Chubu Hospital, Nakagami, Japan); Carola W.H. de Fijter (OLVG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); Nicola Mongera (Ospedale S. Maurizio, Bolzano, Italy); Stefano Pini (Padua University Hospital, Padua, Italy); Consuelo de Biase, Raphaël Duivenvoorden, Luuk Hilbrands, Angele Kerckhoffs, Anne-Els van de Logt and Rutger Maas (Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands); Olga Lebedeva (Regional Clinical Hospital, Yaroslavl, Russia); Veronica Lopez (Regional Hospital of Malaga, Malaga, Spain); Jacobien Verhave and Louis J.M. Reichert (Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem, The Netherlands); Denis Titov (RUDN University, Moscow, Russia); Ekaterina V. Parshina (Saint Petersburg State University Hospital, Saint Petersburg, Russia); Luca Zanoli and Carmelita Marcantoni (San Marco Hospital, University of Catania, Catania, Italy); Liesbeth E.A. van Gils-Verrij (Sint Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands); John C. Harty (Southern Health & Social Care Trust, Newry, Northern Ireland); Marleen Meurs (Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem, The Netherlands); Marek Myslak (SPWSZ Hospital, Szczecinie, Poland); Yuri Battaglia (St. Anna University Hospital, Ferrara, Italy); Paolo Lentini (St. Bassiano Hospital, Bassano del Grappo, Italy); Edwin den Deurwaarder (Streekziekenhuis Koningin Beatrix, Winterswijk, The Netherlands); Maria Stendahl (Swedish Renal Registry, Jönköping, Sweden); Hormat Rahimzadeh (Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran); Marcel Schouten (Tergooi, Hilversum, The Netherlands); Ivan Rychlik (Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and Faculty Hospital Kralovske Vinohrady, Prague, Czech Republic); Carlos J. Cabezas-Reina and Ana Maria Roca (Toledo University Hospital, Toledo, Spain); Ferdau Nauta (Treant/Scheper Ziekenhuis, Emmen, The Netherlands); Eric Goffin, Nada Kanaan, Laura Labriola and Arnaud Devresse (Université catholique de Louvain, Cliniques universitaires St Luc, Brussels, Belgium); Anabel Diaz-Mareque (University Clinical Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain); Björn K.I. Meijers, Maarten Naesens, Dirk Kuypers and Bruno Desschans (University Hospital Leuven, Leuven, Belgium); Annelies Tonnelier and Karl M. Wissing (University Hospital Brussels, Brussels, Belgium); Gabriel de Arriba (Universitary Hospital of Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Spain); Ivana Dedinska (University Hospital Martin and Jessenius Faculty of Medicine Comenius University, Martin, Slovakia); Giuseppina Pessolano (University Hospital Medical Center Verona, Verona, Italy); Umberto Maggiore (University Hospital Parma, Parma, Italy); Shafi Malik (University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, Coventry, UK); Evangelos Papachristou (University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece); Ron T. Gansevoort, Marlies Noordzij, Stefan P. Berger, Esther Meijer, and Akin Özyilmaz (Dialysis Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands); Jan Stephan F. Sanders (University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands); Jadranka Buturović Ponikvar, Miha Arnol, Andreja Marn Pernat and Damjan Kovac (University Medical Center Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia); Robert Ekart (University Medical Centre Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia); Alferso C. Abrahams, Femke M. Molenaar, Arjan D. van Zuilen, Sabine C.A. Meijvis and Helma Dolmans (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands); Ekamol Tantisattamo (University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Orange, CA, USA); Pasquale Esposito (University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy); Jean-Marie Krzesinski and Jean Damacène Barahira (University of Liège, Liège, Belgium); Gianmarco Sabiu (University of Milano, Milan, Italy); Paloma Leticia Martin-Moreno (University of Navarra Clinic, Pamplona, Spain); Gabriele Guglielmetti (University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy); Gabriella Guzzo (Valais Hospital, Sion, Switzerland); Nestor Toapanta and Maria Jose Soler (Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain); Antinus J. Luik, Willi H.M. van Kuijk, Lonneke W.H. Stikkelbroeck and Marc M.H. Hermans (VieCuri Medical Centre, Venlo, The Netherlands); Laurynas Rimsevicius (Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania); Marco Righetti (Vimercate Hospital, Vimercate, Italy); Mahmud Islam (Zonguldak Ataturk State Hospital, Zonguldak, Turkey); Nicole Heitink-ter Braak (Zuyderland Medical Center, Geleen and Heerlen, The Netherlands).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hilbrands LB, Duivenvoorden R, Vart P. et al. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 1973–1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang MC, Park YK, Kim BO. et al. Risk factors for disease progression in COVID-19 patients. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu C, Zhou M, Liu Y. et al. Characteristics of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection and progression: a multicenter, retrospective study. Virulence 2020; 11: 1006–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noordzij M, Duivenvoorden R, Pena MJ. et al. ERACODA: the European database collecting clinical information of patients on kidney replacement therapy with COVID-19. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 2023–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockwood K, Theou O.. Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can Geriatr J 2020; 23: 254–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fine J, Gray R.. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 496–509 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL. et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinze G, Dunkler D.. Five myths about variable selection. Transplant Int 2017; 30: 6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medjeral-Thomas NR, Thomson T, Ashby D. et al. Cohort study of outpatient hemodialysis management strategies for COVID-19 in North-West London. Kidney Int Rep 2020; 5: 2055–2065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S. et al. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 1622–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berdahl CT, Glennon NC, Henreid AJ. et al. The safety of home discharge for low-risk emergency department patients presenting with coronavirus-like symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2020; 1: 1380–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goicoechea M, Sánchez Cámara LA, Macías N. et al. COVID-19: clinical course and outcomes of 36 hemodialysis patients in Spain. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 27–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husain SA, Dube G, Morris H. et al. Early outcomes of outpatient management of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1174–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubetzky M, Aull MJ, Craig-Schapiro R. et al. Kidney allograft recipients, immunosuppression, and coronavirus disease-2019: a report of consecutive cases from a New York City transplant center. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 1250–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberici F, Delbarba E, Manenti C. et al. Management of patients on dialysis and with kidney transplantation during the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in Brescia, Italy. Kidney Int Rep 2020; 5: 580–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadaw AS, Li YC, Bose S. et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 mortality: development and validation of a clinical prediction model. Lancet Digit Health 2020; 2: e516–e525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Collaborators that entered data in ERACODA remain the owners of these data. The database information can therefore not be disclosed to any third party without the prior written consent of all data providers, but the database will be made available to the editorial offices of medical journals when requested. Research proposals can be submitted to the Working Group via COVID.19.KRT@umcg.nl. If deemed of interest and methodologically sound by the Working Group and Advisory Board, the analyses needed for the proposal will be carried out by the Management Team.