Abstract

We report a case of a woman from Thailand, living in Malta, who was diagnosed with concomitant tuberculosis (TB) and HIV with depleted CD4 count. Her case was further complicated by the formation of a fistula between the mediastinal lymph nodes and the oesophagus, an unusual finding but for which she had many risk factors. The diagnosis was suspected on CT scan of the thorax and confirmed via upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Following the commencement of both anti-TB and antiretroviral therapy, she suffered a lapse of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome but with aggressive medical management eventually made a full recovery without the need for surgical intervention.

Keywords: HIV / AIDS, TB and other respiratory infections, oesophagus

Background

HIV-positive patients are at a 50-time increased risk of contracting tuberculosis (TB) when compared with HIV-negative individuals. In addition, being immunocompromised poses a greater risk for developing extrapulmonary TB, mostly commonly as a lymphadenitis, although any organ system may be involved. Only 0.15%–0.2% of patients with TB affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) system have involvement of the oesophagus, making it the least likely bodily organ to be affected.1 In the described case, TB and HIV were diagnosed during the initial admission and treatment for both promptly started. Besides being uncommon, TB affecting the oesophagus frequently presents non-specifically thereby confounding the clinical suspicion of TB. Dysphagia, odynophagia, dyspepsia, meal-induced cough, haematemesis and retrosternal chest pain are most commonly reported along with systemic symptoms including fever, lethargy and weight loss.2 Thus, in patients diagnosed with TB, it is important to review symptomatology carefully to exclude the possibility or define the extent of extrapulmonary involvement.

Case presentation

The patient described is a 48-year-old woman from Thailand, non-smoker, who has lived in Malta since 2012. She was referred to Mater Dei Hospital following a community consultation for bleeding per rectum, during which it was noted she was excessively lethargic. At the emergency department she reported a 2-week history of fever and drenching night sweats which did not respond to antibiotics, together with a productive cough and reduced appetite with a reported weight loss of 12 kg over 2 months. Her medical and surgical history was unremarkable other than a contraceptive intrauterine device insertion. She was in a monogamous marriage and had children.

On initial examination, she was noted to be febrile (38.8°C) and mildly tender in the epigastrium. Initial blood investigations demonstrated anaemia, lymphopenia and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. HIV antigen testing was positive and CD4 count was markedly reduced (25 cells/µL). A CT scan was performed which showed extensive mediastinal lymphadenopathy (figure 1). This was investigated further with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Samples obtained demonstrated acid-fast bacilli on microscopy and Mycobacterium tuberculosis on PCR (table 1). She was started on anti-TB (rifabutin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol together with prophylactic pyridoxine) and antiretroviral medication (lopinavir/ritonavir, tenofovir, lamivudine) soon after as well as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia prophylaxis (co-trimoxazole). She improved clinically and was discharged from hospital, only to return 8 days later complaining of epigastric pain, nausea and fever (up to 39°C). A septic screen was taken, with no positive findings, so she was treated with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and an antiemetic before being discharged home. As no repeat CT imaging of the thorax was taken, it is impossible to decipher whether this presentation could have been related to the formation of the oesophagomediastinal fistula with which she was diagnosed during her next admission 1 month later.

Figure 1.

CT thorax showing subcarinal lymphadenopathy (white arrow).

Table 1.

Radiological and histological findings

| CT thorax | March 2018: Extensive mediastinal lymphadenopathy May 2018: Suspected fistula between necrotic subcarinal lymph nodes and oesophagus November 2019: Tracheobronchial tree appears normal and no intrathoracic lymphadenopathy |

| EBUS TBNA | Large subcarinal lymph node at station 7 and large paratracheal lymph node at station 4R |

| OGD | Pan-oesophageal candida. Sinus opening, lying beneath a crescent shaped fold of mucosa, seen at 27 cm from incisors, actively draining white opaque material |

| PCR/culture | Samples obtained from EBUS: Mycobacterium tuberculosis detected by PCR M.tuberculosis cultivated from solid media. No resistance Candida albicans also cultivated |

| Histology | EBUS station 7 lymph node: Extensive caseous necrosis with ill-defined granulomatous inflammation and abundant polymorphs |

EBUS TBNA, endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration; OGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy.

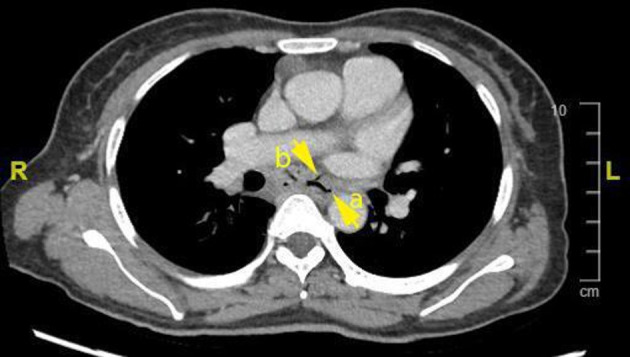

On her third visit to hospital, she was again complaining of fever up to 39.9°C, a mild cough and left upper quadrant pain. Appetite had improved and she reported weight gain. Repeat CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis reported a likely fistula between the oesophagus and necrotic subcarinal lymph nodes (figure 2). An urgent oesophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed and a fistula sinus draining caseous material into the oesophagus was noted, together with oesophageal candidiasis (table 1 and figure 3). In addition to the anti-TB regimen, she was prescribed an antifungal (fluconazole) and PPI (omeprazole). She continued to spike temperatures and it was noted that her CD4 count had fallen from 90 cells/µl to 50 cells/µL but HIV viral load had decreased. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and leishmania PCR were negative and so paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) was proposed as a diagnosis of exclusion. She was treated with a tapering steroid regimen, improved clinically and was once again discharged.

Figure 2.

CT thorax showing the oesophagus (a) and the oesophagomediastinal fistula (b).

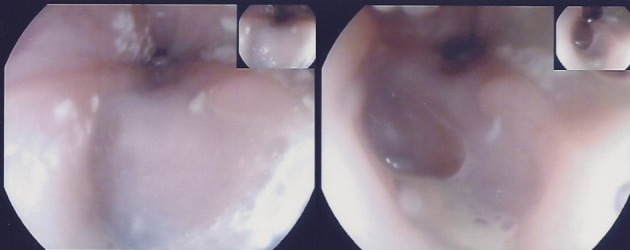

Figure 3.

There is a horseshoe-shaped defect and caseous material seen at the fistulous opening.

Differential diagnosis

During the initial presentation of our patient, she reported a plethora of constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss and productive cough. Since she was originally from a country with increased prevalence of TB, this was the primary differential diagnosis. In those suspected of having TB, it is mandatory to exclude HIV coinfection as part of the initial workup as these patients are at increased risk of complications and drug resistance.

A CT of the thorax during her initial presentation reported mediastinal lymphadenopathy of which the differential pool is diverse: primary or metastatic malignancy, infection, sarcoid, occupational lung disease, congestive cardiac failure and medication related. In this case, the lymph node was sampled endoscopically, giving a rapid diagnosis of TB lymphadenitis via positive microscopy for acid fast bacilli, which was corroborated by PCR and positive culture growth. Histology reported no features suspicious for malignancy (table 1).

The patient’s vague symptomatology, which did not include dysphagia or odynophagia, made the discovery of a fistula on repeat thoracic imaging particularly interesting.

Outcome and follow-up

Our patient continued to comply with antiretroviral treatment and was followed up closely on an outpatient basis. Anti-TB treatment was stopped after 6 months. Symptomatically, she no longer reported cough or fever and episodes of night sweats became less frequent, although lethargy persisted for some time.

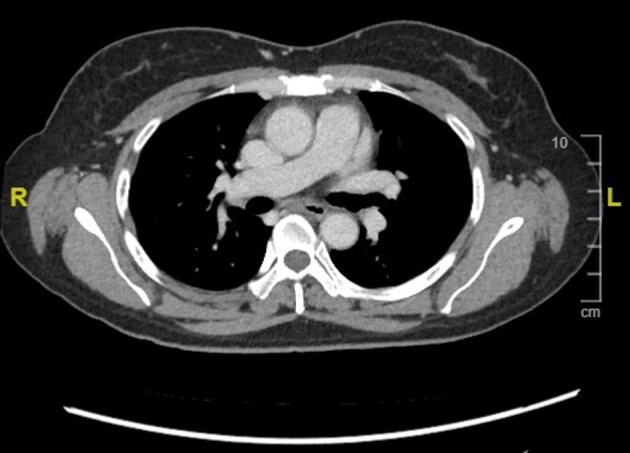

One year later, she reported that all her symptoms had resolved. Her CD4 count improved to 132 cells/µL and HIV viral load was undetectable at less than 20 copies/mL. Repeat CT thorax showed no intrathoracic lymphadenopathy and a normal tracheobronchial tree with resolution of previous oesophageal mediastinal fistula (figure 4). A further year down the line her weight has increased by 20 kg, CD4 count is greater than 200 cells/µL and HIV viral load remains undetectable.

Figure 4.

CT thorax showing resolution of mediastinal lymphadenopathy and oesophagomediastinal fistula.

Discussion

The most common mechanism of secondary oesophageal involvement in TB is secondary to mediastinal adenitis leading to adenomegaly which in turn may exert pressure on the oesophageal wall, causing local extension of disease.1 Tracheobronchial, subcarinal and right paratracheal lymph nodes are the most common mediastinal nodes to be affected. The subcarinal nodes, as in this case, are most often implicated in forming oesophageomediastinal fistulae due to direct contact with the oesophagus.3 Other rarer mechanisms include haematogenous spread and lymphatic retrograde spread.1 Secondary involvement was highly suspected in our patient’s case due to the CT findings of mediastinal lymphadenopathy on initial presentation (figure 1). Her only GI symptoms were constant epigastric pain and tenderness, together with an intermittent cough, fever and reduced appetite associated with weight loss. Fistula formation is suspected when imaging on CT demonstrates lymphadenopathy showing air content which is continuous with the oesophagus as was the case here (figure 2), 2 months after her initial presentation. Upper GI endoscopy was carried out and confirmed the presence of a sinus which was discharging caseous material into the oesophagus (figure 3). In relation to oesophageal infection in patients with HIV, rarely does it extend beyond the mucosal surface (eg, in candidiasis, CMV or herpes simplex). When transmural inflammation is observed (such as with ulcers or fistulae), this suggests concomitant TB.4

de Silva et al described six cases of HIV positive men with TB-associated oesophageal fistulae of which none improved when started on an anti-TB regimen.5 In fact, two cases ultimately died. It is to be noted that while these patients were treated with anti-TB drugs, antibiotics and antifungals, antiretroviral medication was not commenced. In contrast to our described case, where medical treatment for both TB and HIV was started promptly, complete resolution of the fistula was reported 1 year after diagnosis, without the need for surgical intervention. This suggests that aggressive medical management can be curative of TB-related oesophageal disease as long as the patient remains strictly compliant. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend that antiretroviral medication be started within 2 weeks of commencing TB treatment if the CD4 count is less than 50 cells/mm3, as in our case, even though this may increase the risk of TB-IRIS. Had the CD4 count been higher, antiretroviral medication should be started by 8 –12 weeks. The major exception is TB meningitis when antiretroviral medication should not be started within the first 8 weeks of TB treatment.6

Oesophagomediastinal fistulae very rarely require any further intervention. The development of new lesions in the GI tract after commencing treatment can be explained not by a failure of treatment, but by delayed hypersensitivity to mycobacterial proteins within lymph nodes.3 This may have very well been the case with our patient, who was already on treatment when the fistula was discovered. This is known as paradoxical IRIS, in which the commencement and continuation or completion of treatment leads to a paradoxical worsening of symptomatology or radiological findings. This is in contrast to unmasking IRIS, in which patients with HIV who have started antiretroviral therapy subsequently begin to present with another subclinical infection. Corticosteroids play a role in reducing morbidity in these cases.7 Our patient was especially prone to developing paradoxical IRIS, as antiretroviral and anti-TB therapy were commenced together, which is a prominent risk factor.8 Imaging taken before the commencement of treatment was not suspicious for fistula formation. Anti-TB therapy was continued for 6 months and repeat CT scanning 1 year after initial diagnosis confirmed the resolution of her fistula and of the intrathoracic lymphadenopathy (figure 4) Surgical management of oesophageal fistulae should be reserved for cases which fail to resolve with medical therapy or for those presenting as emergencies, for example, with massive haematemesis.9

Learning points.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease with the ability to affect any organ system and although oesophageal involvement is rare, it is important to consider this when reviewing patient symptomatology.

Immunocompromised individuals are at a higher risk for extrapulmonary involvement of TB.

New TB lesions may develop in the GI tract due to delayed hypersensitivity to mycobacterial proteins, hence disease progression should not be excluded even after commencing treatment.

The commencement of anti-TB and antiretroviral therapy in conjunction puts one at higher risk for developing IRIS.

Aggressive medical management together with strict patient compliance may be curative for TB-related fistulae.

Footnotes

Contributors: MNG was responsible for the literature review and manuscript preparation. SMV, CV and JS contributed towards review and editing of the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Santamaría AZ, Vallejo VG, Gómez PC. Oesophageal fistula due to tuberculosis in HIV patients: report of two cases. Rev Colomb Radiol 2016;28:4630–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rämö OJ, Salo JA, Isolauri J, et al. Tuberculous fistula of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:1030–2. 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00471-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devarbhavi HC, Alvares JF, Radhikadevi M. Esophageal tuberculosis associated with esophagotracheal or esophagomediastinal fistula: report of 10 cases. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:588–92. 10.1067/mge.2003.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasikumar C, Utpat K, Desai U, et al. “Esophagomediastinal fistula presenting as drug resistant tuberculosis”. Indian J Tuberc 2020;67:363–5. 10.1016/j.ijtb.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Silva R, Stoopack PM, Raufman JP. Esophageal fistulas associated with mycobacterial infection in patients at risk for AIDS. Radiology 1990;175:449–53. 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2326472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Treatment of persons living with HIV | Treatment | TB | CDC n.d. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/tbhiv.htm [Accessed 21 Jul 2021].

- 7.Lanzafame M, Vento S. Tuberculosis-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 2016;3:6–9. 10.1016/j.jctube.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breton G, Duval X, Estellat C, et al. Determinants of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV type 1-infected patients with tuberculosis after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1709–12. 10.1086/425742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasikumar C, Utpat K, Desai U, et al. "Esophagomediastinal fistula presenting as drug resistant tuberculosis". Indian J Tuberc 2020;67:363–5. 10.1016/j.ijtb.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]