Abstract

Background: Understanding the role of nonphysicians in Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) completion is limited.

Objectives: To examine the role that nurse practitioners (NPs) play in POLST completion and differences between NPs and physicians in POLST orders.

Design: Retrospective observational study.

Setting/Subjects: A total of 3829 POLST forms submitted to the West Virginia (WV) e-Directive Registry between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, which was completed by 98 NPs and 511 physicians.

Measurements: POLST forms completed and orders in POLST Section A and Section B by all physicians and NPs according to practice (primary care, palliative care, hospital, and nursing home) and by palliative care physicians and NPs only.

Results: NPs completed almost twice as many forms on average as physicians (9.54 ± 20.82 vs. 5.66 ± 17.18, p = 0.0064). NPs constituted 16.10% (98/609) of the clinicians writing POLST forms but completed 24.40% (935/3829) of the forms (p < 0.001). Compared with physicians' orders, a greater percentage of NP's orders was for do-not-resuscitate in Section A (87.20% vs. 72.60%, p < 0.001) and comfort measures in Section B (42.90% vs. 33.10%, p < 0.001). There was a greater percentage of NPs in palliative care practice than physicians (23.50% vs. 6.07%, p < 0.001), and palliative care NPs completed 64.20% (600/935) of the forms submitted by NPs compared with palliative care physicians who completed 17.90% (517/2894) of the forms submitted by physicians (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: In WV, physician and NP POLST completion differs based on practice. NPs completed significantly more POLST forms on average and more often ordered comfort measures. NPs can play a significant role in POLST completion.

Keywords: advance care planning, APRN, medical orders, nurse practitioner, POLST, POST

Introduction

Advance care planning has been widely recommended as a means to support informed values-based decision making and promote high-quality patient-centered care for persons with serious illness who may be approaching death.1–3 Experts have recognized that skilled advance care planning requires not only goals of care conversations to elicit patients' values, preferences, and goals but also documentation to ensure that the medical care provided aligns with patients' preferences.2–3 Among innovations that help to achieve the intent of advance care planning and document patients' preferences in the form of medical orders is the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) program.1,4 The National Quality Forum endorsed POLST as a preferred practice and noted that, compared with other advance care planning approaches such as advance directive completion, POLST yields higher adherence by medical professionals because it provides a system for transfer of immediately actionable medical orders based on patients' preferences across health care settings.4

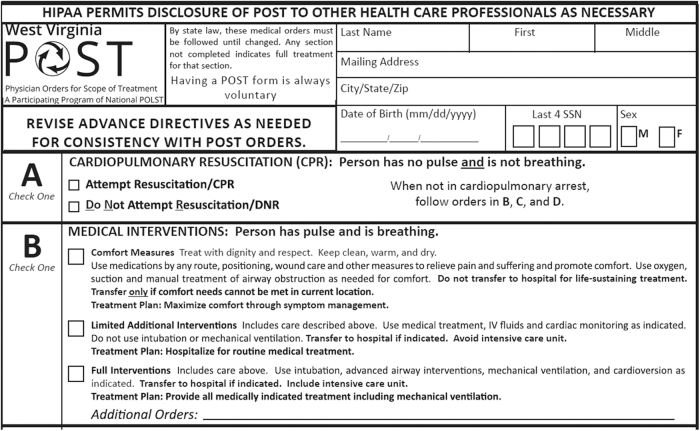

Nurse practitioners (NPs) make up the most rapidly growing component of the primary care workforce.5 There are more than 290,000 NPs licensed in the United States.6 In most states, 75% of these NPs practice in primary care.5 There are proportionally more NPs in West Virginia (WV) than in the United States (1 per 681 West Virginians vs. 1 per 1141 Americans), and NPs play a major role in health care in the WV, the third most rural state in the country. Recognizing that NPs and physician assistants in addition to physicians may conduct advance care planning discussions, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began paying these clinicians for advance care planning counseling in 2016.7 Others have also observed that NPs can play a key role in advance care planning with patients in diverse health care settings as part of interdisciplinary care teams8–10 and specifically identified counseling about and completion of POLST forms as one of the valuable services they can provide.10,11 WV is a member of the National POLST Program and refers to its POLST form as POST (Physician Orders for Scope of Treatment) (Fig. 1). Hereinafter, POLST is used for forms completed in WV. During 2016, the first year of signatory authority of NPs for POLST forms in WV, they completed 14.40% of the POLST forms submitted to the WV e-Directive Registry.12 Compared with those completed by physicians, NP-completed forms were more likely to order do-not-resuscitate (DNR) in Section A and comfort measures in Section B. At the time, we speculated that specialist palliative care NPs could increase the extent to which Americans have their end-of-life wishes known and respected and that specialist palliative care NPs might find a niche in advance care planning with POLST completion.

FIG. 1.

Section A and Section B of the West Virginia POLST form. POLST, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

The purpose of this study was to use data from the WV e-Directive Registry to expand our understanding of the role that NPs play in POLST completion by comparing the number and POLST orders by practice (palliative care including hospice, hospitalist, nursing home, or primary care) of NPs with physicians to determine if they differ.

Materials and Methods

Design and setting

This is a retrospective observational analysis of POLST forms submitted to the WV e-Directive Registry between July 1, 2018, and June 30, 2019. The function of the registry and submission of forms to it have been previously described.13 In short, the WV e-Directive Registry14 (www.wvendoflife.org/wv-e-directive-registry) is operated by the WV Center for End-of-Life Care (www.wvendoflife.org) and funded by WV University. Patients (or their medical power of attorney representative or health care surrogate if the patient lacks decision-making capacity) can initial an opt-in box on an advance directive or POLST form to authorize their form(s) to be submitted to the Registry and released to treating health care providers. The WV e-Directive Registry is accessible online to providers 24 hours a day, seven days a week through the WV Health Information Network15 portal unified landing page (www.wvhin.org) and is one of four active statewide registries in the United States that stores POLST forms and makes them available to treating health care providers.16

Variables

The following variables were recorded from each POLST form (Fig. 1) submitted to the Registry: date of completion, Section A orders (Attempt Resuscitation/CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation or Do Not Attempt Resuscitation/DNR), and Section B orders (full interventions, limited additional interventions, or comfort measures). The following variables were recorded for the clinician completing the POLST form: licensed osteopathic physician (DO), licensed allopathic physician (MD), or licensed NP; and clinician practice (community palliative care, hospice, hospitalist, inpatient hospital specialty palliative care consultation, nursing home, or primary care).

Registry personnel also checked each form for completion errors and notified the submitting clinician or patient, as appropriate, if there was an error. The most common errors were as follows: (1) the opt-in box was not checked so that the form could not be entered in the Registry; (2) signature-related errors in which either the clinician's name was illegible so that their license to practice in WV was not verifiable or that the clinician signature was missing; and (3) contradictory orders in Section A and Section B such as CPR in Section A and comfort measures in Section B.

Since palliative care includes hospice care, for the purpose of this analysis, physicians and NPs who practiced in hospital-based palliative care consultation, community palliative care, and hospice were included in the practice category of palliative care. During the study period, the WV Board of Medicine reported that there were 4307 licensed MDs,17 the WV Board of Osteopathic Medicine reported that there were 985 licensed DOs,18 and the WV RN Board reported that there were 2629 licensed NPs.19

Statistical analyses

The six continuous outcome variables based on the numbers of orders recorded from POLST forms are reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and are then log-transformed to better analyze the smaller NP group (n = 98) and the larger physician group (n = 511). These six outcomes included the number of POLST forms completed, and five variables linked to the choices available in Section A and Section B of the POLST form: CPR, DNR, full interventions, limited interventions, and comfort measures (Fig. 1). Independent samples t tests were used to compare each of the six continuous outcomes between NPs and physicians.

Chi-square tests were used to examine the associations between clinician (NP and physician) and practice and to compare Section A and Section B orders between all physicians and NPs as well as between palliative care physicians and NPs who submitted POLST forms to the Registry during the study period. The SAS19 PROC FREQ was used to estimate population proportions of POLST form completion for binary outcome variables. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated. All analyses and data management were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (Cary, NC).20

Study ethics

This study was approved by the WV University Institutional Review Board.

Results

During the study period, there were 3829 POLST forms completed by 609 health care providers: 98 NPs completed 935 forms and 511 physicians completed 2894 forms. As a percentage of licensed clinicians in their discipline in WV during the study period, fewer NPs completed POLST forms compared with physicians (98/2629 [3.70%] vs. 511/5292 [9.70%], p < 0.001). NPs constituted 16.10% (98/609) of the clinicians writing POLST forms but completed 24.40% (935/3829) of the forms (p < 0.001). There was a greater percentage of NPs in palliative care practice than physicians (23.50% vs. 6.07%, p < 0.001) (Table 1), and palliative care NPs completed 64.20% (600/935) of the forms submitted by NPs compared with palliative care physicians who completed 17.90% (517/2894) of the forms submitted by physicians (p < 0.001) (Table 2). NPs completed almost twice as many forms on average as physicians (9.54 ± 20.82 vs. 5.66 ± 17.18, p = 0.0064) (Table 3). Remarkably, palliative care clinicians completed 29.20% of the POLST forms while constituting only 8.90% of the clinicians submitting forms.

Table 1.

Number of Physicians and Nurse Practitioners Completing Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Forms by Practice

| Clinician | Practice |

Total | χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Palliative care | Hospital | Nursing home | ||||

| Physician, n (%) | 350 (68.50) | 31 (6.07) | 102 (20.00) | 28 (5.48) | 511 | 38.19 | <0.0001 |

| NP, n (%) | 44 (44.90) | 23 (23.50) | 21 (21.40) | 10 (10.20) | 98 | ||

NP, nurse practitioner; χ2, chi-square value.

Table 2.

Number and Percentage of Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Forms Completed by Clinician and Practice

| Clinician | Practice |

Total forms | χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Palliative care | Hospital | Nursing home | ||||

| Physician, n (%) | 819 (28.30) | 517 (17.90) | 783 (27.10) | 775 (26.80) | 2894 (100) | 742.54 | <0.0001 |

| NP, n (%) | 84 (9.00) | 600 (64.20) | 110 (11.80) | 141 (15.10) | 935 (100) | ||

Table 3.

Mean Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Forms Completed by Clinician and Practice

| Forms per clinician | POLST completion by clinician practice |

All settings | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Palliative care | Hospital | Nursing home | ||||

| Physician (mean ± SD) | 2.34 ± 6.00 | 16.70 ± 25.10 | 7.68 ± 14.30 | 27.70 ± 53.40 | 5.66 ± 17.18 | 2.74 | 0.0064 |

| NP (mean ± SD) | 1.91 ± 1.60 | 26.10 ± 35.40 | 5.24 ± 8.70 | 14.10 ± 19.20 | 9.54 ± 20.82 | ||

SD, standard deviation; t, t test value; POLST, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

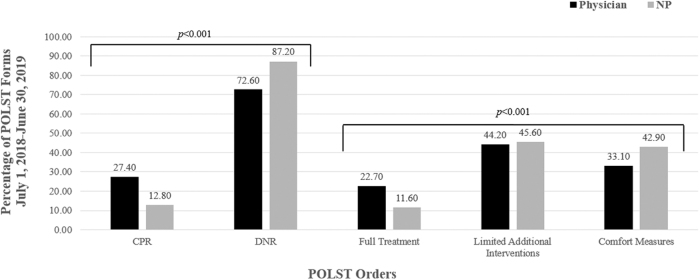

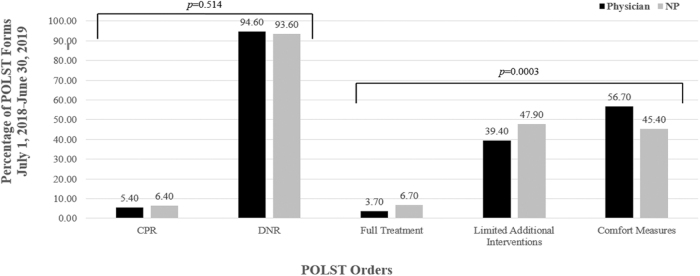

More primary care clinicians (physicians and NPs) submitted POLST forms than any other practice type, but the physicians in nursing homes (27.70 forms per physician) and the NPs in palliative care (26.10 forms per NP) completed a disproportionately higher number of POLST forms per clinician (Table 3). In Section A of the POLST form, a greater percentage of NP's orders was for DNR compared with physicians' orders (87.2% vs. 72.6%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In Section B of the POLST form, NPs more often ordered comfort measures (42.90% vs. 33.10% p < 0.001) and less often full treatment (11.60% vs. 22.70%, p < 0.001) compared with physicians (Fig. 2). To recast this information, NPs had increased odds of completing POLST forms (OR = 1.93, 95% CI: 1.24–2.99) and ordering DNR (OR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.31–3.20), limited additional interventions (OR = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.63–4.23), and comfort measures (OR = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.50–4.48) compared with physicians (Table 3 and Fig. 2). For physicians and NPs in palliative care practice, however, there was no difference between them in the percentage of CPR and DNR orders in Section A (Fig. 3), but in Section B, NPs in palliative care wrote a higher percentage of limited treatment and a lower percentage of comfort measures orders than palliative care physicians (Fig. 3). Of the 517 POLST forms palliative care physicians completed, a higher percentage (283/517, 54.7%) was for hospice patients compared with those completed by NPs (197/600, 32.8%, p < 0.001).

FIG. 2.

Physician and nurse practitioner POLST orders.

FIG. 3.

Palliative care physician and nurse practitioner POLST orders.

The completion error rate varied between physicians and NPs. Physicians had more completion errors on the POLST forms they submitted compared with NPs (819/2894, 28.3% vs. 126/935, 13.5%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

These findings support the hypothesis that NPs can play a significant role in POLST completion and expand the knowledge of the role they can play based on their practice in advance care planning, especially including goals of care conversations and POLST completion. Two previous studies in Oregon and WV have found that NPs complete 11% and 14.40% of the POLST forms submitted to their state registries, respectively.10,12 This current study presents more recent results showing that in 2018–2019 in WV, NPs completed 24% of POLST forms submitted to the state registry while constituting only 16.10% of the clinicians writing them. Two years after WV codified NP signatory authority for POLST forms,21 NPs completed almost double the number of POLST forms per provider compared with physicians and nearly one-quarter of all POLST forms submitted to the e-Directive Registry. These findings support policy recommendations22 for removing barriers that prevent NPs from practicing at the full level of their expertise, including elicitation of patient preferences for life-sustaining treatments and completion of POLST forms. These findings also should encourage states that currently limit POLST form completion to physicians23 and that wish to maximize their citizens' opportunities for advance care planning to amend legislation or policies to authorize NPs to complete POLST forms.

In this study, physician and NP practices differed regarding POLST completion. Physicians completed more POLST forms than NPs in primary care, hospital, and nursing home practice settings, but NPs completed more POLST forms in palliative care practice settings, particularly as hospital-based specialist palliative care consultants. Overall, physicians were more likely to order CPR in Section A and full treatment in Section B and less likely to order comfort measures in Section B than NPs. In contrast, there was no difference in the ratio of DNR orders submitted between palliative care physicians and NPs, but palliative care physicians ordered comfort measures in Section B more often than palliative care NPs. This difference is most likely due to the predominantly hospice patient population of the palliative care physicians versus the predominantly hospitalized seriously ill patients seen by the palliative care NPs. Palliative care NPs in hospital-based palliative care saw a high percentage of patients who were seriously ill with a high risk of one-year mortality24 identified by a “No” response to the surprise question (“Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”)25 In a cancer patient population, patients for whom the clinician would not have been surprised if the patient died in the next year had a one-year mortality of 41%.13 In fact, previous studies of the WV Palliative Care Network have shown that, for 96% of the patients seen by palliative care consultants, they would not have been surprised if the patients died in the next year.26 Hence, the NPs were seeing patients earlier in their chronic disease trajectory than the palliative care physicians, which could explain why fewer palliative care NPs compared with palliative care physicians would have ordered comfort measures on the POLST forms they completed.

These findings also point to the substantial role that palliative care clinicians, especially palliative care NPs, can play in completion of POLST forms. Although they represented less than 10% of all clinicians who submitted POLST forms to the Registry and only 0.68% of licensed clinicians in WV at the time, NPs completed 29% of the forms submitted to the Registry during the study period. Furthermore, palliative care NPs completed a disproportionately higher number of POLST (26.10 forms per NP) than clinicians in other areas of practice except for physicians in nursing homes (27.70 forms per physician). Palliative care NPs also completed more POLST forms than palliative care physicians despite being fewer in number (23 vs. 31).

To date, 40 states and Washington D.C. have codified their POLST programs into law or an official form.26 NPs are authorized to sign a POLST form in 34 states and Washington D.C.26 The American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) encourages NPs to be familiar with POLST forms and state or jurisdiction requirements and to be ready to discuss advance care planning with patients who may be candidates for POLST.27 The data presented in this study suggest that NPs complete POLST forms with fewer errors than physicians. Despite readiness, NPs in several states do not have signatory authority for POLST form completion, even though the evidence demonstrates that NPs are effective members of the interdisciplinary team.28–35

The strengths of this study include its large sample size of 609 providers and the details available through the WV e-Directive Registry regarding clinicians, practices, Section A and Section B POLST orders, completion rates, and errors. The study has several limitations that potentially restrict its generalizability. The research was conducted in only one state with a more developed advance directive and medical order registry than most states. WV is one of only a few states that have a “mature” (better developed) POLST program.23 WV state has several hospitals with greater than 300 beds with well-developed inpatient palliative care consultation services that perform more than 1000 consultations per year and employ three or more palliative care NPs. The patient population is limited to patients who opted-in for submission of POLST forms to the WV e-Directive Registry.14 This process was likely facilitated by providers who were more knowledgeable about end-of-life care and the WV e-Directive Registry. It is also possible that POLST forms not submitted to the registry differ in orders documented by clinician or practice. Additionally, while NPs are recognized in WV state policy as primary care providers, collaboration with a physician is required for prescribing medications, and there is a three-year transition period before NPs are authorized to practice independently and prescribe Schedule 3–5 medications. WV does not allow NPs to prescribe Schedule II controlled substances.36 This study demonstrates what is possible in a rural, low per capita income state.

Conclusions

Palliative care NPs can play a key role in the care of seriously ill patients. This study documents that NPs conducted advance care planning and completed POLST forms in a disproportionately large percentage of patients considering the number and practice distribution of NPs to other clinicians. It is likely that NPs' participation on inpatient hospital palliative care consultation teams afforded them this opportunity. This study identifies the valuable role that NPs can play in POLST completion and in enhancing the communication that POLST affords to patient treatment preferences across health care settings, especially for the seriously ill and those at end of life.

Funding Information

No funding was received.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. : Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821-832.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickman SE, Hammes BJ, Moss AH, Tolle SW: Hope for the future: Achieving the original intent of advance directives. Hastings Cent Rep 2005. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1353/hcr.2005.0093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Quality Forum: A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association of Nurse Practitioners: Nurse practitioners in primary care. www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/position-statements/nurse-practitioners-in-primary-care. (Last accessed July17, 2020)

- 6.American Association of Nurse Practitioners: More than 290,000 nurse practitioners licensed in the United States. Updated March 3, 2020. https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/290-000-nps-licensed-in-us# (Last accessed July17, 2020)

- 7.Medicare Learning Network: Advance care planning Updated August 2019. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/advancecareplanning.pdf (Last accessed June2020.)

- 8.Copley M, Ingram CJ: Nurse practitioner-led education: Improving advance care planning in the skilled nursing facility. Gerontol Geriatr Res 2020;9:1 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark MA, Ott M, Rogers ML, et al. : Advance care planning as a shared endeavor: Completion of ACP documents in a multidisciplinary cancer program. Psycho-oncology 2017;26:67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes SA, Zive D, Ferrell B, Tolle SW: The role of advanced practice registered nurses in the completion of Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment. J Palliat Med 2017;20:415–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickman SE, Unroe KT, Ersek M, et al. : Systematic advance care planning and potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing facility residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:1649–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Constantine LA, DiChiacchio T, Falkenstine EC, Moss AH: Nurse practitioners' completion of Physician Orders for Scope of Treatment forms in West Virginia: A secondary analysis of 12 months of data from the state registry. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2018;30:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedraza SL, Culp S, Knestrick M, et al. : Association of POLST form use with end-of-life care quality metrics in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:367–368 [Google Scholar]

- 14.WV Center for End-of-Life Care: Introducing the WV E-directive registry. http://wvendoflife.org/for-providers/e-directive-registry/ (Last accessed May11, 2020)

- 15.West Virginia Health Information Network: Unified landing page. www.wvhin.org. (Last accessed July2020)

- 16.National POLST: National POLST state registries. Updated June 2020. https://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020.06.30-National-POLST-State-Registries.pdf (Last accessed September29, 2020)

- 17.West Virginia Board of Medicine 2018: 2018 annual report executive summary. https://wvbom.wv.gov/about/AnnualReports.asp (Last accessed July14, 2020)

- 18.WV Board of Osteopathic Medicine: 2017 fall newsletter. www.wvbdosteo.org/ (Last accessed October12, 2019)

- 19.WV RN Board. Statistics. https://wvrnboard.wv.gov/Pages/default.aspx (Last accessed October12, 2019)

- 20.SAS statistical software, Version 9.4 Copyright © 2014 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA [Google Scholar]

- 21.H.B. 4334, West Virginia 82nd Legislature. Clarifying the requirements for a license to practice as an advanced practice registered nurse and expanding prescriptive authority. www.legis.state.wv.us/Bill_Status/bills_text.cfm?billdoc=hb4334%20ENR.htm&yr=2016&sesstype=RS&i=4334 (Last accessed March14, 2020)

- 22.Head BA, Song MK, Wiencek C, et al. : Palliative nursing summit: Nurses leading change and transforming care: The nurse's role in communication and advance care planning. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2018;20:23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National POLST: National POLST program designations. https://polst.org/programs-in-your-state/ (Last accessed July7, 2020)

- 24.Kelley AS: Defining “serious illness.” J Palliat Med 2014:17:985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. : Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2010;13:837–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West Virginia Palliative Care Network Team Report: West Virginia Center for End-of-Life Care. http://wvendoflife.org/media/1209/palliative-care-team-report-2016-2018_10_16-13_29_15-utc.pdf (Last accessed July20, 2020)

- 27.American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Issues at a glance: Provider Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST). https://storage.aanp.org/www/documents/advocacy/POLST.pdf (Last accessed: March 12, 2020)

- 28.Kuo Y, Chen N, Baillargeon J, et al. : Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations in Medicare Patients with Diabetes: A comparison of primary care provided by nurse practitioners versus physicians. Med Care 2015;53:776–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez-González NA, Djalali S, Tandjung R, et al. : Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;12:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martsolf G, Auerbach D, Arifkhanova A: The impact of full practice authority for nurse practitioners and other advanced practitioners in Ohio. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, RR-848-OAAPN, 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR848.html (Last accessed August4, 2020)

- 31.Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al. : Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: A randomized trial. JAMA 2000;283:59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naylor MD, Kurtzman ET: The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Aff 2010;893–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White KM, et al. : Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990–2008: a systematic review. 2011. In: Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews [Internet]. York (UK): Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK); 1995-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99366/ (Last accessed August4, 2020)

- 34.Virani SS, Maddox TM, Chan PS, et al. : Provider type and quality of outpatient cardiovascular disease care. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1803–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scope of Practice Policy: West Virginia scope of practice policy: State profile. Last updated 2020. https://dev.scopeofpracticepolicy.org/states/wv/ (Last accessed September29, 2020)